Abstract

The objective of the study was to identify the possibility of developing a risk of addiction to social networks and to know the satisfaction of basic psychological needs depending on network usage time, the number of networks used, and the practice hours and type of sport developed. A sample of 265 university students (Mage = 28.23; SD = 8.44; 110 men and 155 women) completed distinct self-report measures. Results revealed significant differences in the addiction-symptoms, social-use and geek-traits, being higher when the time of network consumption increases and when the number of networks used is bigger. Regarding the sports variables, collective sports are significantly associated with the risk of addiction symptoms. However, the practice of collective sports seems to satisfy basic psychological needs. In conclusion, the higher use and number of social networks seem to predict the risk of addiction to them. Single sports practice decreases the probability of network addiction and, collective and single sports help satisfy basic psychological needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

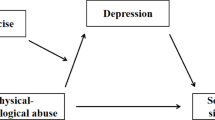

The consumption of social networks has increased exponentially during the last decades (Alharthi et al., 2017). Currently, it is common for thousands of users to consume social networks, also known as websites or applications that allow the user to build a profile and connect with others (Boyd and Ellison, 2007). In the 21st century, 2010 million people use social networks such as Facebook and 330 million on Twitter (Chan and Leung, 2018). These networks allow users to share content through the web and react to comments from other users (Chan and Leung, 2018). The high consumption of networks has caused researchers to investigate the negative consequences they can have on people (Malo-Cerrato and Viñas-Poch, 2018). Among some of its harmful effects is the possibility of developing a risk of addictions (Tonioni et al., 2012), dissatisfaction with basic psychological needs (BPNs) (Przybylski et al., 2009; Shen et al., 2013), and sedentary behaviors (Roberts et al., 2017; Ying et al., 2020). In this work, it was decided to select a university-age population, given that, as Becoña (2006) indicates, social networks tend to trap young people and distort their world. Furthermore, in previous work, it was found that the Spanish university population tended to develop an addiction to networks such as Twitter (Durán and Guerra, 2015), which hurt their physical activity (Martínez-Martínez et al., 2022). Likewise, addiction to networks can occur as a means of escape from isolation and the need to meet social needs (Siguencia and Verónica, 2017). On the other hand, some works indicate that exercise promotes healthy consumption of networks (Golpe et al., 2017) and satisfies basic psychological needs such as relatedness (Lamoneda and Huertas-Delgado, 2019). For this reason, it is necessary to combine these variables in a study and investigate a novel aspect within these areas. This novel aspect is whether the number of networks and their time of use increases the risk of addiction, if the practice and type of sport played determine the risk of addiction, if the number of networks and their time of use influences the BPN, and if the practice and type of sport practised is related to BPN.

Regarding the possibility of developing a risk of addiction to the networks, some behaviors allow alerting about the probability of becoming addicted. Among these behaviors, the addiction-symptoms, social-use, geek-traits and nomophobia stand out (Peris et al., 2018). Peris et al. (2018) state that addiction-symptoms involves perceiving relief when using social networks. Social-use implies using networks for purposes of socio-virtual interrelation. Geek-traits refer to the behaviors adopted by those obsessed with joining groups with specific interests (p.eg., virtual games). King et al. (2010) add nomophobia, an abnormal fear of being without a mobile. Addicted people have difficulty reducing their time online (Martínez-Martínez et al., 2022). Moreover, when interrupting the connection, they manifest impulsiveness and irritability (Xanidis and Brignell, 2016). Tonioni et al. (2012) claim that when network consumption is higher, the risk of addiction increases and that users with several networks spend more time than those with fewer networks, increasing the risk of addiction.

Several works examined the connection between the risk of addiction to networks and sports practice (Golpe et al., 2017; Ying et al., 2020). Roberts et al. (2017) indicate that the decrease in sports practice is one problem associated with the consumption of networks. This happens because people spend many hours a day staying connected to the networks, and the time available for sports practice decreases (Lapousis and Petsiou, 2017). However, other research shows that using networks has a promotional effect on sport participation (Wang and Zhou, 2018). This happens because the networks act as media tools that improve social awareness about sports and transmit information about their benefits (Hua-Mei et al., 2022). Regarding the effect of sports practice on the risk of addiction, it has been shown that sport prevents the overconsumption of networks through the development of self-control (Jonker et al., 2011; Oaten and Cheng, 2006). Self-control is one of the most important psychological factors regulating impulses and the risk of addiction (Baumeister, 2003). Considering the type of sport practised (individual or collective), the risk of network addiction is also of interest. For example, Park et al. (2016) found that individual sports are highly effective for developing self-control, and that individual sports practitioners have higher self-control than non-athletes. This happens because athletes must maintain high performance by facing challenging situations without the help of peers (Park et al., 2016). However, in collective sports, other factors, such as team cooperation and strategy, come into play (Šagát et al., 2021), and the levels of self-control among the participants are lower.

Concerning the influence of social networks on BPNs, there are previous works that have examined this topic (Shen et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015). BPNs are an inherent requirement of human beings that can guide their behavior in order to achieve psychological well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2000). There are three BPNs: competence, autonomy and relatedness (Ryan and Deci, 2002). Competence is the perception of being able to perform a task. Autonomy determines the degree of initiative a person feels to control their behaviors. The relatedness is the perceived feeling of belonging to a social group. Can (2018) and Partala (2011) found that networks helped satisfy the competence. This happened when the participants leveled up in online games or improved their network management. On the other hand, the use of networks satisfies autonomy when the user accesses the content of the virtual environment without restrictions (Can, 2018; Partala, 2011). Cajas-Tibanta (2019) revealed that relatedness satisfaction was higher in people who used networks excessively. This happens because people perceive that they establish social connections via virtual and reduce the feeling of isolation (Roberts et al., 2000). On the other hand, the consumption of networks increases as more networks are available (Tonioni et al., 2012). In other words, users with multiple networks have a higher risk of developing addiction to them. To our knowledge, no studies were found that relate the risk of addiction to the number of networks used. However, considering that the greater number of networks increases the risk of addiction (Tonioni et al., 2012), BPNs are usually satisfied with the consumption of networks (Cajas-Tibanta, 2019; Can, 2018; Partala, 2011; Roberts et al., 2000), in principle the more social networks the user has, the more likely they are to satisfy their BPN.

Finally, this paper examines the action of sports practice on BPN satisfaction, a topic previously discussed in the literature (Fraguela-Vale et al., 2020; Kang et al., 2020). Within the sports field, when a participant compares themself with their peers, his/her perception of competence declines as his/her confidence in his/her chances of success decreases (Nicholls, 1989). However, offering to allow the choice of activities in which athletes perceive themselves as effective facilitates the satisfaction of this BPN (Carrasco et al., 2019). Lim and Wang (2009) and Zhang et al. (2012) consider that athletes who practice sports freely satisfy their BPN of autonomy. Moreover, sport generates opportunities to establish social connections, thus the relatedness BPN is often satisfied (Lamoneda and Huertas-Delgado, 2019; Ntoumanis, 2001). On the other hand, in previous works, the association between the type of sport and the satisfaction of BPN (Pellicer et al., 2021) was studied. Moreno and Hellín (2001) found that competence is more satisfied in collective sports. This happens when each athlete is allowed to complete the activities to be carried out based on their motor level (Moreno and Hellín, 2007). Moreover, competence is satisfied when athletes are perceived as more effective than opponents. On the other hand, Pellicer et al. (2021) verified that the collective sport modality satisfied the autonomy BPN to a greater extent. This can occur when teammates or other agents do not sufficiently control the athlete’s behavior. Regarding relatedness satisfaction, Wikman et al. (2018) found that individual sports satisfy this to a lesser extent this BPN. This happens because collective sport provides a learning environment that facilitates interpersonal interactions and the integration of athletes (Wikman et al., 2018) and improves prosociality (Martínez and González, 2017). However, Jodra et al. (2017) consider that the individual sport modality presents fewer dissocial behaviors than collective sports due to the fact that the collective sports share in the group the responsibility of the actions.

As a novelty of this study, this research could be one of the first times that the risk of addiction is related to the number of networks used. Moreover, this work simultaneously examines the risk of addiction to networks and the satisfaction of BPN depending on the daily consumption of networks, the number of networks used by participants, the practice of sports and the sports modality developed. Therefore, the objective of the study was to identify the possibility of developing a risk of addiction to social networks and to know the satisfaction of basic psychological needs depending on network usage time, the number of networks used, and the practice and type of sport developed. Previous studies indicated that the consumption of networks decreases sports practice (Lapousis and Petsiou, 2017) and the opposite (Wang and Zhou, 2018), and that individual sports develop greater self-control (prevents the risk of addiction to networks) than collective sports (Park et al., 2016). On the other hand, social networks satisfied the three BPNs (Cajas-Tibanta, 2019; Can, 2018; Partala, 2011), but no studies were found that relate the risk of addiction to the number of networks used and BPN. Therefore, the starting hypothesis is: a) Individual sports practice prevents the risk of addiction to networks, and greater network consumption favors BPN satisfaction. No hypotheses are established regarding whether greater consumption of networks favors or decreases sports practice, as opposite results are found. Hypotheses are also not formulated about the risk of addiction to networks depending on the number of networks used and how it influences BPN, as no previous studies that address these variables are found.

Method

Participants

A cross-sectional design was carried out, and 265 Spanish university students participated (Mage = 28.23; SD = 8.44; 110 men and 155 women). The type of studies were 122 Undergraduate Students and 143 Master’s Students. The participants came from 10 universities, and the most prevalent studies were Master’s in Teacher Training (43.1%), Social Education (12%), Psychology (8.3%), Economics (4.7%), Sports Sciences (3.6%), Criminology (2.9%), Biology (2.1%), Primary Education Teacher (1.4%), Computer Engineering (1.4%) and others (20.5%). Regarding the state of occupation, 29 were only studying, 39 were working and studying, and 149 were studying and unemployed. Regarding the number of networks used, 84 used three social networks, 82 used two social networks, 48 used more than three social networks, 48 used one social network, and 3 did not use social networks. In relation to the time they spend consuming networks, only 3.4% of students do not spend an hour a day, 27.17% of students spend an hour a day, 38.03% of students spend 2 hours a day, 15.9% of students spend three hours a day, 18.5% students spend more than three hours a day. On the other hand, 79.25% of the participants practised sports at least once a week (individual, collective or mixed). The number of days per week of sport was 9.8% 1 day, 20.8% 2 days, 20.8% 3 days, 13.2% 4 days, 8.3% 5 days, 3.4% 6 days, and 1.9% 7 days per week.

Measures

An ad hoc sociodemographic questionnaire of 14 items developed specifically for this research was administered. The sociodemographic variables evaluated in Spanish university students were age, gender, marital status, employment, network consumption, and sports practice. Of the total 14 items, 6 examine the biological characteristics, three the employment situation, two the consumption of social networks, and three the sports practice. In the consumption of networks, questions such as hours dedicated to the consumption of networks and the number of social networks used were included. Regarding the practice of sports, it was inquired about the practice of sport (yes or no), the number of days per week of sport (none, one, two, three, four, five, six or seven), the type of sport practised (individual/collective/both) and if they were associated to federations (yes/no). In the questionnaire, there were open, dichotomous and polytomous questions.

To examine the risk of social networks it was used the The Risk of Addiction-Adolescent to Social Networks and the Internet scale (ERA-RSI; Peris et al., 2018). The ERA-RSI is made up of 29 items grouped into four factors: addiction-symptoms (9 items; e.g., I access the social network anywhere and anytime), social-use (8 items; e.g., I use the chat), geek-traits (6 items; e.g., I need to know if the recipient has read my message) and nomophobia (6 items; e.g., I feel uncomfortable if no one chats with me when I am online). The answers range from 1: Never or hardly ever; 2: Sometimes; 3: Quite a few times; and 4: Many times or always. The scale reported an adequate reliability index in all the subscales of the study: addiction-symptoms (α = 0.78), social-use (α = 0.76), geek use (α = 0.64), and nomophobia (α = 0.71).

To examine the satisfaction of the BPN, it was used the Spanish version (González-Cutre et al., 2015) of the Basic Needs Satisfaction in General Scale (BNSG-S; Gagné, 2003). The scale is made up of 21 items that measure the satisfaction of the need for competence (e.g., the people I know tell me that I am good at what I do), autonomy (e.g., I feel free to decide how to live my life) and relatedness (e.g., I really like the people I socialize with). There were three inverse items for each of the factors. The participants had to answer all the items on a Likert-type scale from 1 (false) to 7 (totally true). The reliability showed in this study was adequate: competence (α = 0.68), autonomy (α = 0.76) and relatedness (α = 0.76). The participants had to answer all the items on a Likert-type scale from 1 (false) to 7 (totally true). The reliability showed in this study was adequate: competence (α = 0.68), autonomy (α = 0.76) and relatedness (α = 0.76).

Procedure

The research was carried out following international ethical standards, anonymity was preserved, and it was approved by the board of Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR; No. 074/2022). In this sense, the IP address of the participants was not recorded to guarantee anonymity. The researchers contacted students from 10 different universities through professors from various studies. Once the researchers contacted the teachers, they informed the students about the conditions for participating in the research. Subsequently, students interested in participating in the research completed the online questionnaire. Once they accessed the questionnaire link, they signed an informed consent form. The questionnaires were completed while the students were in class through computers and mobile phones.

Data analyses

The data analyses were performed using SPSS 19 version software. The descriptive analysis of average, minimum, maximum, frequencies, percentages, and standard deviation was used to assess the sample characteristics. The MANOVA test was used to assess the mean differences in the factors of hours of network consumption and the number of networks used depending on the risk of addiction to social networks (addiction-symptoms, social-use, geek-traits and nomophobia). MANOVA test was also used to assess the mean differences in the practice of sport and the type of sport practised depending on the risk of addiction to social networks (addiction-symptoms, social-use, geek-traits and nomophobia). MANOVA test was used to assess the mean differences in the hours of network consumption and the number of networks used depending on the satisfaction of BPN (competence, autonomy, and relatedness). Finally, MANOVA test was used to assess the mean differences in the sports practice and the type of sport practised depending on the satisfaction of BPN. The Eta2 was used to analyze the effect size. Following Cohen’s (1988) criteria, the effect size results were considered as: η2 = 0.01 (small), η2 = 0.06 (medium), η2 = 0.14 (large). Finally, the comparison post hoc Tukey HSD was performed to determine the statistically significant differences between the means of the variables with more than three options that reported significant differences in the ANOVA test.

Results

Firstly, the objective was to find out if there are differences in the risk of addiction to networks (addiction-symptoms, social-use, geek-traits and nomophobia) depending on the time of networks consumption (none hour, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, more than 3 h) in university students. For this purpose, a MANOVA was performed. In this analysis, the sample was divided into five groups based on network consumption (none hour, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, more than 3 h) and the different risk variables for network addiction was analyzed. The MANOVA analysis revealed a significant effect on the risk of addiction to networks according to the time of networks consumption (Lambda of Wilks; F = 9.77; p < 0.05) and large effect size (Eta2 = 0.13). In Table 1, the results showed that university students who consumed more than 3 h of networks usage per day showed higher addiction-symptoms (p < 0.05; Eta2 = 0.37), carried out higher social-use (p < 0.05; Eta2 = 0.22), more geek- traits (p < 0.05; Eta2 = 0.07) and nomophobia (p < 0.05; Eta2 = 0.05).

Secondly, the objective was to find out if there were differences in the risk of network addiction depending on the number of social networks used by university students. In the MANOVA analysis, the number of social networks (none network use, one network, two networks, three networks, and more than three networks) was selected as the dependent variable. MANOVA analysis was performed. In this analysis, the sample was divided into five groups based on network consumption (none hour, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, and more than 3 h) and the different risk variables for network addiction were analyzed. The MANOVA analysis revealed a significant effect on the risk of network addiction based on the number of social networks used (Lambda of Wilks; F = 4.06; p < 0.05) and a medium effect size (Eta2 = 0.05). In Table 1, results showed statistically significant differences in university students who use three social networks are the ones who show the higher addiction-symptoms (p < 0.05; Eta2 = 0.13), make more social-use (p < 0.05; Eta2 = 0.16), and show geek-traits (p < 0.05; Eta2 = 0.07).

Thirdly, the objective was to find out if there were differences in the risk of addiction to network consumption depending on the sports practice in university students. In the MANOVA analysis, sports practice was selected as the dependent variable and the sample was divided into two groups based on the practice of sport (sports practice and non-sports practice) and the risk of addiction to networks. The MANOVA analysis did not reveal a significant effect on the risk of addiction to networks according to sports practice (Wilks’ Lambda; F = 0.52; p > 0.05) and a small effect size (Eta2 = 0.00).

Fourthly, the objective was to find out if there were differences in the risk of addiction to network consumption depending on the practice of none, individual, collective and both sports. In the MANOVA analysis, the type of sports performed was selected as the dependent variable. In this analysis, the sample was divided into four groups based on the type of sports performed (none sport, individual, collective, and both) and the risk of addiction to networks was analyzed. The MANOVA analysis reveals a significant effect on the risk of addiction to networks according to the type of sports performed (Wilks’ Lambda; F = 0.90; p < 0.05) and a small effect size (Eta2 = 0.01). In Table 2, the results showed that university students who practiced collective sports had higher and statistically significant chances of showing addiction-symptoms to networks (p < 0.05; Eta2 = 0.03).

Fifthly, the objective was to find out if there were differences in the satisfaction of BPN depending on the time of network consumption in university students. In the MANOVA analysis, network consumption time (none hour, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, and more than 3 h) was selected as the dependent variable. In this analysis, the sample was divided into five groups based on network consumption (none hour, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, and more than 3 h), and the different BPN satisfaction levels were analyzed. The MANOVA analysis did not reveal a significant effect on the satisfaction of BPN according to the time of networks consumption (Lambda of Wilks; F = 0.88; p >0.05) and a small effect size (Eta2 = 0.01).

Sixthly, the objective was to find out if there were differences in the satisfaction of BPN depending on the number of social networks used by university students. In the MANOVA analysis, the number of social networks was selected as the dependent variable. In this analysis, the sample was divided into five groups based on the number of social networks used (none network use, one network, two networks, three networks, and more than three networks) and the satisfaction of BPN was evaluated. In Table 3, the MANOVA analysis did not reveal a significant effect on the satisfaction of BPN based on the number of social networks used (Lambda of Wilks; F = 0.50; p > 0.05) and small effect size (Eta2 = 0.00).

Seventhly, the objective was to find out if there were differences in the satisfaction of BPNs depending on the practice of sports among university students. In the MANOVA analysis, sports practice was selected as the dependent variable. MANOVA analysis was performed. In this analysis, the sample was divided into two groups based on the practice of sport (sports practice and no sports practice) and satisfaction of BPN was examined. The MANOVA analysis revealed a significant effect on BPN satisfaction depending on the practice of sport (Wilks’ Lambda; F = 2.46; p < 0.05) and a small effect size (Eta2 = 0.02). In Table 4, the results showed significant differences in which university students who did not practice sport perceive a lower satisfaction of the BPN for competence (p < 0.05; Eta2 = 0.02).

Eighthly, the objective was to find out if there were differences in the satisfaction of BPN depending on the type of sport practiced. In the MANOVA analysis, the type of sport performed was selected as the dependent variable. MANOVA analysis was performed. In this analysis, the sample was divided into four groups based on the type of sport performed (individual, collective, both sports and none sport) on the satisfaction of BPN analyzed. The MANOVA analysis reveals a significant effect on the satisfaction of BPN according to the type of sport performed (Wilks’ Lambda; F = 1.01; p < 0.05) and a small effect size (Eta2 = 0.01). In Table 4, the results showed that university students who practised both types of sport perceived a greater satisfaction of the BPN for competence (p < 0.05; Eta2 = 0.02).

Post hoc differences in the risk of addiction to social networks depending on the hours of network consumption and the number of network used

According to the comparison post hoc (Tukey HSD), significant differences were found between the means of the risk of addiction to social networks depending on the hours of network consumption. In Table 1, the participants who consumed more than 3 h of daily networks (p < 0.05) had the greatest addiction-symptoms, social-use, geek-traits and nomophobia. On the other hand, in Table 1, the participant who used more than three networks (p < 0.05) were the ones with the greatest addiction-symptoms, social-use and geek-traits.

Post hoc differences in the risk of addiction to social networks depending on the type of sport practiced

According to the comparison post hoc (Tukey HSD), significant differences were found between the means of the risk of addiction to social networks depending on the type of sport practised. In Table 2, the participants who practiced collective sports reported higher addiction-symptoms (p < 0.05) than individual sports practitioners.

Post hoc differences in the satisfaction of basic psychological needs depending on the type of sport practiced

According to the comparison post hoc (Tukey HSD), significant differences were found between the means of the BPN satisfaction depending on the type of sport practised. In Table 4, the participants who practised both sports reported higher satisfaction of BPN competence (p < 0.05).

It is pointed out that, in Table 4, despite finding differences between the satisfaction of BPN depending on the sport practice, it was not necessary to use the Tukey test. In Table 4, it can be seen that sports practice really helped to satisfy the BPN of competence (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The objective of the study was to identify the possibility of developing an addiction to social networks and to know the satisfaction of basic psychological needs depending on network usage time, the number of networks used, and the practice and type of sport developed.

In the first objective, the results showed that the participants with the higher risk of addiction (addiction-symptoms, social-use, geek-trait, and nomophobia) use social networks more than three hours a day. These results are consistent with Tonioni et al. (2012), who reported that high consumption of networks increased the risk of addiction to them. Regarding the number of social networks that a user has and the probability of risk of addiction to them, the results reveal that the participants who have three social networks presented higher addiction-symptoms, social-use, and geek traits. The risk of addition to social networks was also quite high in the participants who had more than three social networks (regarding those who were users of only two networks, one network, or none network). This happens because a person with multiple networks will probably spend more time using them. As Tonioni et al. (2012) state, the high consumption of networks increases the risk of addiction.

Regarding the role of sports on the risk of addiction to social networks, this research has not found that practising sports significantly reduces the probability of risk of addiction. Despite this, the results show that non-sport participants present more symptoms related to the risk of addictive behaviors (addiction-symptoms, social-use, geek-traits, and nomophobia). The results found to align with those described by Macdonald-Walli et al. (2012) and Vandelanotte et al. (2009), who found that high dependence on networks favored little sports practice. This happens because people spend many hours a day staying connected to the networks, and the time available for sports practice decreases (Lapousis and Petsiou, 2017). The role of sports on the risk of addictive behaviors to social networks varies depending on whether the sport practised is individual or collective. In the case of this research, collective sport is the one that is mostly associated with the risk of addiction-symptoms. This result is consistent with Jonker et al. (2011) and Park et al. (2016), who defended that individual sports were more effective than collective sports in developing strong self-control (that managed to inhibit addictive network behaviors). This happens because, in individual sports, athletes must regulate the adverse situations they face in the sport without the help of partners (Park et al., 2016).

Concerning the second objective, in this work, it was possible to check that the use of social networks does not significantly influence the satisfaction of the BPN. Despite this, there seems to be a trend in which the people who consume the least social networks are those who perceive greater satisfaction in BPNs (competence, autonomy, and relatedness). These results are consistent with those found by Shen et al. (2013) where the participants who used the Internet and did not make healthy use had a higher risk of addiction. Likewise, Przybylski et al. (2009) demonstrate that a large amount of gaming is negatively related to well-being because participants became obsessed with them. However, our results are opposite to those of Can (2018), who found that social networks helped satisfy the competence when the participants leveled up in online games or improved their network management. In the same way, the results differ from those of Partala (2011), who indicate that the use of social networks satisfies autonomy when the user accesses the content of the virtual environment without restrictions. Namely, the results are opposite to those of Cajas-Tibanta (2019), who revealed that people who use social networks perceive relationship satisfaction by not feeling alone.

Finally, regarding the action of the sport on the satisfaction of the BPN, it has been seen that in a statistically significant way, the practice of sports (both sports) helps to satisfy the BPN of competence. In this study, in collective sports, athletes do not compare themselves with their peers because, otherwise, the perception of competence declines (Nicholls, 1989). In the same way, the participants who practised sports individually seemed effective when doing it, so it helped them to satisfy their competence. Regarding the action of the type of sport practised (individual or collective or both) in the satisfaction of the BPN, in a statistically significant way, it was found that participation in both types of sport increased the satisfaction of the BPN of competence. In this case, it seems that the athletes choose activities that perceive themselves as effective, facilitating the satisfaction of the aforementioned BPN (Carrasco et al., 2019) or that feel equal or more effective than their teammates or rivals in collective sports. In addition, in this study, although in a non-statistically significant way, the BPN of autonomy was satisfied to a lesser extent in individual sports practitioners than in collective. This occurs when the athlete’s behavior is not highly controlled or conditioned by teammates or other contextual agents (Lamoneda and Huertas-Delgado, 2019). The same thing happened in the BPN of relatedness, which presented a higher degree of satisfaction when the sport practised by the sample was collective, just as Lamoneda and Huertas-Delgado (2019) had indicated. This happens because collective sports provide a learning environment that facilitates interpersonal interactions and the integration of athletes (Wikman et al., 2018).

Among the limitations of the research, it is highlighted that in this study, the variables examined were evaluated with a Spanish sample and in the university stage. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to people of other nationalities and different age ranges. In addition, it is mentioned that the methodology used is based on analyzing data obtained from a self-report questionnaire. Self-report measures may introduce small objectivity biases, such as social desirability in sustainable social media consumption and BPN satisfaction. On the other hand, in this work, other contextual variables that may be affecting the results were not considered (e.g., parenting styles can influence network consumption, friendship routines can contribute to young people joining a greater number of social networks, the hours of study could make it difficult to practice sports, etc.). Therefore, it would be recommended that future researchers consider the possibility of including these variables.

As practical implications, this work reveals a series of behaviors that are manifested externally in people (addition-symptoms, geek-traits, and nomophobia) and that allow warning of a possible risk of addiction to social networks (Peris et al., 2018). It also makes it possible to convey the idea that excessive consumption of social networks is associated with less satisfaction of the three BPNs inherent to any human being (Shen et al., 2013; Przybylski et al., 2009). On the other hand, this research highlights the importance of participating in sports activities to satisfy BPN (p.eg., competence).

In future research, sociodemographic variables such as the type of family (nuclear, single parent, etc.) and the occupation of the parents of the participating sample should be included. Children learn the habits of their mother and father figures, and perhaps those who have lived with a single-parent family or with parents with problems reconciling family and work life may report a greater probability of showing the risk of addiction to networks. The aforementioned problem of reconciling work and family life could lead to less use of limits and control by parents in relation to their children’s use of networks. It is also interesting to inquire about the lifestyles of the friends of the students in the university stage. A priori, it does not seem atypical to consider that university students who practice sports have friends who adopt lifestyles opposed to sedentary. Finally, it would be interesting to know if there are significant differences in the risk of addiction to social networks and the satisfaction of BPN according to gender and in other stages of life other than university age.

In conclusion, the behaviors that reveal a high possibility of developing a risk of addiction to social networks, such as addiction symptoms, social use, geek traits, and nomophobia, increase as the time of consumption of networks and the number of social networks rises. Sports practice seems to reflect a lower tendency to the probability of developing risks of addiction to social networks. The practice of sports and the collective sports modality help athletes feel effective by satisfying the BPN of competence. Therefore, replacing sedentary behaviors, such as the consumption of social networks, with active alternatives, such as sports practice, will decrease the risk of addiction to social networks among young university students and will help them feel effective within the field of sports.

Data availability

The data will be available on reasonable request to the correspondence author. Data are available in the Supplementary File.

References

Alharthi R, Guthier B, Guertin C et al. (2017) A dataset for psychological human needs detection from social networks. IEEE Access 5:9109–9117. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2706084

Baumeister RF (2003) Ego depletion and self-regulation failure: a resource model of self-control. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27(2):281–284. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ALC.0000060879.61384.A4

Becoña E (2006) Adicción a nuevas tecnologías. Nova Galicia Edicións

Boyd DM, Ellison NB (2007) Social networking sites: definition, history, and scholarship. J Comput Commun 13(1):210–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

Cajas-Tibanta MT (2019) The satisfaction of psychological needs and its relationship with the use of social networks in high school students of the Rumiñahui educational unit. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Ecuador

Can S (2018) Academic procrastination behaviors, internet addiction and basic psychological needs of adolescents: A model proposal (Unpublished doctoral thesis). Yildiz Technical University, Istanbul

Carrasco H, Fernández S, Reigal R et al. (2019) Influence of basic psychological needs on the habits of physical-sports practice of schoolchildren in the commune of Valparaiso. Rev Iberoam Psicol Ejerc Dep 14(2):121–125

Chan WSY, Leung AYM (2018) Use of social networking sites for communication among health professionals: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 20(3):117–123

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2 ed) Lawrence Earlbaum Associates

Durán M, Guerra JM (2015) Usos y tendencias adictivas de una muestra de estudiantes universitarios españoles a la red social Tuenti: La actitud positiva hacia la presencia de la madre en la red como factor protector. Psicol 31(1):260-267

Fraguela-Vale R, Varela-Garrote L, Carretero-García M et al. (2020) Basic psychological needs, physical self-concept, and physical activity among adolescents: autonomy in focus. Front Psychol 20(11):1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00491

Gagné M (2003) The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior engagement. Motiv Emot 27(3):199–223. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025007614869

Golpe FS, Isorna FM, Gómez SP, Rial BA (2017) Uso problemático de Internet y adolescentes: el deporte sí importa. Retos Educ F ís Dep Recreac 31:52–57

González-Cutre D, Sierra AC, Montero-Carretero C et al. (2015) Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the scale of satisfaction of basic psychological needs in general with spanish adults. Ter Psicol 33(2):81–92. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082015000200003

Hua-Mei Z, Han-Bing X, En-Kai G et al. (2022) Can internet use change sport participation behavior among residents? Evidence from the 2017 Chinese General Society Survey. Front Public Health 10:1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.837911

Jodra P, Domínguez R, Maté-Muñoz JL (2017) Incidence of sports practice in the disruptive behavior of children and adolescents. Ágora. Educ F ís Deporte 19(3):193–206. https://doi.org/10.24197/aefd.2-3.2017.193-206

Jonker L, Elferink-Gemser M, Visscher C (2011) The role of selfregulatory skills in sport and academic performances of elite youth athletes. Talent Dev Excell 3(2):263–275

Kang S, Lee K, Kwon S (2020) Basic psychological needs, exercise intention and sport commitment as predictors of recreational sport participants’ exercise adherence. Psychol Health 5(8):916–932. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2019.1699089

King A, Valença A, Nardi A (2010) Nomophobia: the mobile phonein panic disorder with agoraphobia: reducing phobias or worsening of dependence? Cogn Behav Neurol 23(1):52–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNN.0b013e3181b7eabc

Lamoneda J, Huertas-Delgado FJ (2019) Basic psychological needs, sports organization and levels of physical activity in schoolchildren. Rev Psicol Deporte 28(1):115–124

Lapousis G, Petsiou E (2017) The impact of the Internet use in physical activity, exercise and academic performance of school students aged 14-16 years old. Int J N. Technol Res 3(2):12–16

Lim BC, Wang CJ (2009) Support for perceived autonomy, norms of behavior in physical education and intention of physical activity. Psicol Deporte Ejerc 10(1):52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.06.003

Macdonald-Walli K, Jago R, Sterne JA (2012) Social network analysis of childhood and youth physical activity: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 43(6):636–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.08.021

Malo-Cerrato S, Viñas-Poch F (2018) Excessive use of social networks: psychosocial profile of Spanish adolescents. Comun Med Educ Res J 26(2):101–109. https://doi.org/10.3916/C56-2018-10

Martínez FD, González J (2017) Self-concept, physical activity practice and social response in adolescents relationships with academic performance. Rev Iberoam Educ 73(1):87–108. https://doi.org/10.35362/rie731127

Martínez-Martínez FD, González-García H, González-Cabrera J (2022) Student´s social networks profiles, psychological needs, self-concept and intention to be physically active. Behav Psychol 30(3):757–772

Moreno JA, Hellín P (2001) Valoración de la Educación Física por el alumno según el género del profesor. Actas del XIX Congreso Nacional de Educación Física y Escuelas Universitarias de Magisterio. Universidad de Murcia, Murcia

Moreno JA, Hellín MG (2007) The interest of compulsory secondary education students towards physical education. Rev Electr Investig Educ 9(2):1–20

Nicholls JG (1989) The competitive ethos and democratic education. Prensa de la Universidad de Harvard

Ntoumanis N (2001) A self-determination approach to understanding motivation in physical educationa. Br J Educ Psychol 71(2):225–242. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709901158497

Oaten M, Cheng K (2006) Longitudinal gains in self-regulation from regular physical exercise. Br J Health Psychol 11(4):717–733. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910706X96481

Park JA, Park MH, Shin JH et al. (2016) Effect of sports participation on self-control mediated internet addiction: a case of Korean adolescents. Rev Kasetsart Soc Sci 37(3):164–169

Partala T (2011) Psychological needs and virtual worlds: case second life. Int J Hum Comput Stud 69(12):787–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2011.07.004

Pellicer JE, García MS, Ferriz VA (2021) Basic psychological needs associated with the practice of individual and collective sport. Retos Educ F ís Dep Recreac 42:500–506. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v42i0.87480

Peris M, Maganto C, Garaigordobil M (2018) Scale of risk of addiction to social networks and Internet for adolescents: reliability and validity (ERA-RSI). Rev Psicol Cl ín con Niños Adolesc 5(2):30–36. https://doi.org/10.21134/rpcna.2018.05.2.4

Przybylski AK, Weinstein N, Ryan RM et al. (2009) Having to versus wanting to play: Background and con-sequences of harmonious versus obsessive engagement in videogames. CyberPsychol Behav 12(5):485–492. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2009.008

Roberts JD, Rodkey L, Ray R, Knight B, Saelens BE (2017) Electronic media time and sedentary behaviors in children: findings from the built environment and active play study in the Washington DC area. Prev Med Rep 6:149–156

Roberts LD, Smith LM, Clare MP (2000) You’re so much bolder on the net. Routledge

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Target article: The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq 11(4):227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2002) Overview of self-determination theory: an organismic dialectical perspective. The University of Rochester Press, Rochester

Šagát P, Bartik P, Curitianu M et al. (2021) Self-esteem, individual versus team sport. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:1–7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412915

Shen CX, Liu RD, Wang D (2013) Why are children attracted to the Internet? The role of need satisfaction perceivedonline and perceived in daily real life. Comput Hum Behav 29(1):185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.08.004

Siguencia RF, Verónica FG (2017) Nivel de adicción al internet y comportamiento adictivo de los niños de sexto y séptimo grado de la escuela. [Tesis Doctoral no Publicada]. Universidad de Cuenca

Tonioni F, Alessandris LD, Lai C et al. (2012) Internet addiction: hours spent online, behaviors and psychological symptoms. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 34:80–87

Vandelanotte C, Sugiyama T, Gardiner P et al. (2009) Associations of Internet and computer use in leisure time with overweight and obesity, physical activity and sedentary behaviors: a cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res 11(3):28–37. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1084

Wang L, Tao T, Fan C et al. (2015) Does psychological need satisfaction perceived online enhance well-being? Internet use and well-being. Psych J 4(3):146–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.98

Wang LX, Zhou H (2018) Influential factors of sport participation of migrant workers in China: base on comparison of household registration type. J Wuhan Inst Phys Educ 52:12–17. https://doi.org/10.15930/j.cnki.wtxb.2018.04.002

Wikman J, Elsborg P, Nielsen G et al. (2018) Are team sport games more motivating than individual exercise for middle-aged women? A comparison of levels of motivation associated with participating in floorball and spinning. Kinesiology 50(1):34–42. https://doi.org/10.26582/k.50.1.5

Xanidis N, Brignell CM (2016) The association between the use of social network sites, sleep quality and cognitive function during the day. Comput Hum Behav 55:121–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.004

Ying CY, Awaluddin M, Kuang KL, Cheong SH, Baharudin A, Miaw YL, Sahril N, Azahadi O, Ahmad N, Ibrahim N (2020) Association of Internet addiction with adolescents´ lifestyle: a national school-based survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010168

Zhang T, Solmon MA, Gu X (2012) The role of teacher support in predicting student motivation and performance outcomes in physical education. Rev Ens Educ Fis 31(4):329–343. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.31.4.329

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were equally involved in the conceptualization work, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, and review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The research was carried out following international ethical standards, anonymity was preserved and it was approved by the board of Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR; No. 074/2022). This study was approved by the ethics board of Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR; No. 074/2022).

Informed consent

The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vega-Díaz, M., González-García, H. Network consumption and sports practice: influence on the risk of network addiction and basic psychological needs. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 822 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03339-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03339-0