Abstract

Village self-governance is becoming a crucial measure in advancing social governance innovation in China. It plays an irreplaceable role in promoting sustainable rural governance, yet some villagers’ willingness and capacity to participate in grassroots governance need cultivation and enhancement. To explore the factors influencing villagers’ willingness to participate in grassroots governance and the conditions under which these factors operate, this study tests its hypotheses using data from the 2019 Chinese Social Survey, which includes 7031 responses. The findings reveal that the positive relationship between political efficacy and villagers’ willingness to participate in grassroots governance is moderated by satisfaction with government performance. Additionally, the interaction effect between political efficacy and satisfaction with government performance on villagers’ willingness to participate in grassroots governance is further moderated by the higher-order effect of perceived social justice. This indicates that among villagers with a high sense of social justice, the interaction effect between political efficacy and satisfaction with government performance more strongly predicts their willingness to participate in grassroots governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chinese society and its governance model are topics of interest to many researchers worldwide. Since the 1980s, the village election system has been implemented in rural China, increasing farmers’ awareness of democracy and their ability to participate in politics. Consequently, farmers have begun to demand more avenues for political participation. This development is crucial for modern democratic societies, the protection of citizens’ rights, and the improvement of governmental performance. However, recent research indicates that participation in village elections is declining (Martinez-Bravo et al. 2022). This trend is closely linked to the accelerated urbanization process in China, where large-scale migration of rural youth to cities has led to the “hollowing out” of rural areas. Additionally, some villagers have a limited understanding of the current mechanisms for expressing their interests and the procedures involved, due to information barriers and restricted access to educational resources (Liu and Wang 2022). This not only undermines their ability to participate in governance but also affects the overall efficacy of rural governance. Simultaneously, the rise of oligarchic politics in certain rural areas has become an issue that cannot be ignored (Ding 2020). This trend of power concentration not only deprives ordinary villagers of opportunities to participate in decision-making processes but also poses significant challenges to the principles of democracy and inclusivity in rural governance (Ma et al. 2018).

In this context, identifying factors that affect villagers’ willingness to participate in grassroots governance and finding ways to effectively enhance this willingness are urgent questions for the Chinese government in its pursuit of rural democratization. Studies have noted that subjective and objective variables such as election procedures (Su et al. 2011), religion (Liang and Xiao 2022), and election corruption (Zhang et al. 2015) are significantly associated with villagers’ willingness to participate in grassroots governance. While the relationship between these variables and villagers’ political participation has been extensively tested and confirmed, there is relatively less research on the influencing mechanisms and boundary conditions of villagers’ willingness to participate in grassroots governance. This paper focuses on the significant influence of political efficacy on villagers’ participation behavior in grassroots governance. Political efficacy (PE) reflects individuals’ cognitive understanding of the structure and functioning of the political system and the political participation process itself. Additionally, this study incorporates villagers’ satisfaction with government performance (SGP) and social justice (SJ) into the model, factors that have not been adequately addressed in previous research.

Political efficacy, as a motivational factor behind political action, has become an increasingly important variable in studying citizens’ political participation. Numerous studies indicate that villagers with high PE tend to be more active in political participation (Li 2003; Grabe and Dutt 2019). However, it has also been observed that the relationship between PE and political participation varies across different countries and regions (Johann et al. 2015). Additionally, some studies have found that political participation can enhance both individual and collective PE (Shi et al. 2023). These discrepancies suggest that existing studies have not clearly established consistent conclusions about the relationship between PE and political participation, nor the conditions under which this relationship arises. Therefore, this paper specifically analyzes the relationship between PE and villagers’ political participation and its boundary conditions. In addition to PE, this paper incorporates psychological variables reflecting individual differences into the validation model, which will significantly enhance our understanding of the conditions under which these relationships operate. This study explores these relationships by examining the moderating effects of villagers’ SGP and perceptions of SJ.

First, the degree of political participation is influenced by a variety of factors. Individual characteristics such as age, personal income, and political affiliation (Landry et al. 2010) affect individuals’ awareness and ability to participate. Moreover, the social environment and political ecology impact individual participation motivation and performance. For example, higher SGP leads villagers to believe that agriculture-related policies protect their rights and interests (Ye et al. 2022), thereby fostering a stronger willingness to participate politically and more active behavior in rural governance activities. Thus, this paper tests the joint effect of villagers’ sense of PE and SGP on their willingness to participate in grassroots governance.

Second, in exploring the relationship between PE and villagers’ willingness to participate in grassroots governance, this study examines the sense of SJ as a higher-order moderating variable. There is a close relationship between SJ and political participation. It has been noted that government policies aimed at ensuring SJ enhance villagers’ motivation to engage in politics (Hou et al. 2023). Furthermore, the level of perceived SJ correlates with PE; an individual’s perceived SJ can increase or decrease their sense of PE (Beaumont 2011; Greenberg 2020). Finally, the perception of SJ impacts SGP. For example, when governments treat people with respect and employ fair procedures, it helps maintain high levels of SGP, fostering a positive attitude towards social governance (Van de Graaf 2020).

In light of this, there exists both an academic imperative and a practical urgency to delve into why villagers are willing to engage in grassroots governance and how to elucidate this willingness through internal and external factors. This study aims to examine the impact of PE, SGP, and SJ on villagers’ willingness to participate in grassroots governance within the framework of Chinese society. Additionally, it seeks to unravel the interactive mechanisms linking these factors. In contrast to prior research, this article offers innovation on three fronts. First, it incorporates situational and structural factors that foster villagers’ involvement in the governance process, confirming the role of external factors, such as SGP, in transforming individual perceptions into a willingness to act. Second, it delves into the influence mechanism of PE on villagers’ inclination to participate in grassroots governance, emphasizing internal factors. Third, it adopts a more micro perspective, exploring the intricate relationship between SJ as an emotional factor and the willingness to engage in political participation.

Literature review and research hypothesis

The impact of political efficacy on villagers’ willingness to participate in grass-roots governance

During the “third wave” of democratization at the end of the 20th century, discussions on political development increasingly focused on the issue of democratization (Yan 2007). Compared to the democratization processes in Western countries, China’s path is fundamentally different. China does not use elections and competition as the sole criteria for measuring a democratic nation but regards the essence of socialist democracy as the people being the masters of the country. In this context, the construction of grassroots democracy in China is particularly prominent, becoming an essential part of democracy with Chinese characteristics. Tong points out that grassroots autonomy not only demonstrates the vitality of China’s democratic politics but also, as an important manifestation of people’s democratic practice, has successfully created diverse ways of democratic practice, fully embodying the fundamental concept of the people being the masters of the country (Tong 2010). Villagers’ participation is a form of participation in the context of villagers’ autonomy, including participation in political life, economic life, social life and cultural life (Xu 2016). It is evident that political participation is the core of democratic politics and a universal principle shared by both China and Western countries. This paper believes that villagers’ participation in grass-roots governance refers to the villagers who live in rural areas and engage in agricultural activities voluntarily participate in grass-roots governance activities in legal ways, and try to influence village-level organizations’ decision making on major issues.

The environment in rural areas is relatively complex, and the process of villagers’ participation in grass-roots governance are affected by many factors, such as social capital (Lay 2016), and internet use (Meesuwan 2016), which are all related to villagers’ willingness to participate in grass-roots governance. Among them, the sense of PE can well reflect the villagers’ confidence in their participation in grass-roots governance, and also reflect their attitude towards whether the current government effectively responds to their demands (Kaufman 2019). Although the concept of PE originated in the West, it holds significant potential for growth and development in the practice of grassroots democratic politics in China. First, the socialist democratic system in China began to advance after 1949, but it only started to take effect after 1978. This indicates that the development of PE among Chinese villagers has not been an overnight process but has undergone a gradual and slow emergence. Second, in the Chinese context, PE reflects the psychological aspect of the people being the masters of the country. Essentially, this means the realization of citizens’ democratic rights, including the right to know, the right to speak, the right to participate, and the right to supervise. PE embodies villagers’ intentions to influence or potentially change government decisions. In the process of village autonomy, grassroots organizations enhance villagers’ awareness and participation in grassroots activities through democratic consultations and one-issue-at-a-time discussions, thereby boosting their sense of PE. As social psychology theory suggests, attitudes strongly predict behavior, with specific attitudes leading to corresponding behaviors (Brügger and Höchli 2019). If PE is the latent attitude within the populace, then political participation is its manifest behavioral expression. Based on the discussion of relevant views and literature analysis, we believe that PE is closely related to villagers’ willingness to participate in grass-roots governance.

First, the relationship between the sense of PE and the willingness to participate in grassroots governance is pivotal. PE represents the belief that individual political action can impact the political process, serving as a fundamental premise for various forms of political participation (Kahne and Westheimer 2006). Research indicates that high levels of political efficacy prompt villagers to mentally construct and engage with the decision-making process, thereby enhancing their trust in institutional fairness. This sense of trust further stimulates their motivation to participate in decision-making, laying a foundation for active involvement in grassroots governance and effective policy implementation (Osborne et al. 2015). This heightened PE spurs enthusiasm for decision-making activities, propelling contributions to grassroots governance and bolstering policy implementation. Empirical studies consistently support this notion, demonstrating that elevated PE positively correlates with villagers’ willingness to engage in grassroots governance (Jacobs et al. 2009).

Second, enhancing villagers’ sense of PE facilitates their involvement in grassroots governance. Extant research confirms a positive correlation between the two, with the strength of PE significantly influencing individual political participation. Specifically, higher political efficacy is associated with a stronger willingness to participate, whereas individuals with lower political efficacy exhibit lower participation motivation (Ardèvol-Abreu et al. 2020; Van Zomeren et al. 2012; Karp and Banducci 2008). At the villager level, as political efficacy increases, their sense of involvement and influence in local governance areas such as the environment, livelihoods, and social services also enhances. This leads to a greater recognition of the importance and value of participating in political activities within the framework of rural self-governance. Thus, augmenting villagers’ sense of PE not only safeguards their interests but also amplifies their sway over grassroots governance decision-making processes.

Accordingly, the following assumptions are proposed in this paper:

H1: Political efficacy has a significant positive impact on villagers’ willingness to participate in grass-roots governance.

The moderating role of villagers’ satisfaction with government performance

Satisfaction with government performance, an important metric in the field of public administration, has its theoretical foundation rooted in the concept of customer satisfaction from business management. In a commercial context, customer satisfaction describes the psychological fulfillment of consumers after a transaction, serving as a key measure of consumer experience (Oliver 1980). When this concept is transferred to public administration, SGP becomes the subjective evaluation standard of the public regarding the services provided and policies implemented by the government (Lewis 2007). It encompasses not only direct feedback on government actions but also the overall perception of government efficiency, transparency, and accountability. Additionally, it acts as a significant external factor through which villagers gauge the level of governmental governance. Thus, this study primarily explores the correlation between villagers’ SGP and their willingness to engage in grassroots governance.

Initially, high SGP positively influences grassroots governance participation, indicating its pivotal role as a precursor to such involvement (Wang 2008). At the inception of policy formulation, the government must thoroughly consider its capacity to execute these policies. Successful policy implementation is a key factor in enhancing public satisfaction. If the government lacks the necessary execution capabilities, not only will it struggle to achieve policy objectives, but it may also provoke widespread dissatisfaction among villagers (Rosenstone et al. 2003). This shows that individuals tend to engage more in decision-making processes when satisfied with governmental actions.

Furthermore, existing research underscores the link between SGP and PE, revealing that heightened SGP fosters greater PE and subsequent political engagement (He et al. 2022). When content with governmental services and decisions, villagers exhibit greater trust in governance and feel empowered to influence decision-making, thus bolstering grassroots governance and fostering community development. Conversely, inadequate services and corrupt leadership dampen villagers’ confidence and enthusiasm, hindering grassroots participation (Miao 2023). Therefore, enhancing SGP can catalyze active grassroots involvement, while low SGP not only diminishes participation but also fosters distrust in governance, undercutting PE’s positive influence on grassroots engagement.

Accordingly, the following assumptions are proposed in this paper:

H2: Villagers’ satisfaction with government performance has a positive moderating role in the relationship between political efficacy and villagers’ willingness to participate in grass-roots governance.

High-order moderating of social justice

The concept of social justice (SJ) is deeply rooted in the fundamental principles of human equality and inalienable rights. Its theoretical foundation originates from social contract theory in philosophy, is reflected in constitutional structures, and ultimately translates into specific practices in public administration (Guy and McCandless 2012). Currently, the theory of SJ is being widely discussed by researchers in the fields of management, law, and education (Tyler 2023). This study focuses on the emotional dimension, defining SJ as the evaluation formed by rural residents based on the fairness of opportunities, processes, and distributions in their daily lives. This evaluation influences their willingness to participate in grassroots governance through the extent to which their emotional needs are met. Thus, this paper examines SJ as a high-order moderating variable.

First, regarding the correlation between SJ perception and villagers’ grassroots governance participation, research indicates that SJ perception not only relates to villagers’ SGP (Ng et al. 2020) but also significantly correlates with their willingness to engage in grassroots governance. Fostering villagers’ eagerness to participate in governance at the grassroots level intertwines with their perception of SJ (Wang and Zhang 2024). In fair environments, citizens feel valued, enhancing their sense of PE and encouraging active involvement in grassroots affairs. For instance, in the assessment of rural low-income households, villagers express their opinions through transparent, legal, and equitable procedures. When their voting and expression rights are respected and fairly treated, villagers not only acknowledge the fairness and rationality of the allocation process but also experience self-affirmation and increased self-worth. This not only enhances SGP but also cultivates increased attention and support for grassroots governance initiatives in the future.

Second, in examining the relationship between PE and grassroots governance participation, some studies have observed the influence of SJ. A heightened sense of SJ amplifies the constructive role of PE in grassroots governance involvement. As SJ perception improves, villagers’ propensity to collaborate with the government increases, fostering more cooperative behaviors (Wilking 2010). Conversely, feelings of injustice dampen voter turnout (Birch 2010). This underscores that within rural governance, if village cadres prioritize personal or select villager interests, rendering unfair decisions and neglecting the public good, village-level organizations falter. Such inequitable practices diminish villagers’ PE and erode their sense of belonging, fostering disillusionment with the decision-making process and even self-distrust (Kanitsar 2022). Therefore, enhancing decision-making transparency, minimizing opaque practices, and fostering SJ are pivotal for bolstering the quality and efficacy of villagers’ grassroots governance participation, thereby advancing democratic development (Strandberg et al. 2021).

Furthermore, there exists a strong correlation between SJ perception and villagers’ SGP. SJ significantly enhances villagers’ SGP, strengthening their willingness to engage in grassroots governance (Wilking and Zhang 2017). Amidst evolving government functions and changing relationships between grassroots organizations and villagers, optimizing organizational governance structures and enhancing governance capabilities are paramount. Grassroots organizations must adapt to these changes, refining governance models, promoting openness and democratic practices, and advancing grassroots governance modernization. For instance, in village affairs publicity, villagers possess the right to information and oversight. Timely disclosure of pertinent information enhances villagers’ SJ perception, fostering greater satisfaction with and trust in village-level organizations, thereby empowering villagers as true stewards of rural life and fostering participatory democracy.

Consequently, we posit that the interplay between PE, villagers’ SGP, and their willingness to engage in grassroots governance is heavily influenced by SJ. Changes in SJ perception significantly impact PE and villagers’ SGP, thereby altering their propensity for grassroots governance participation. Villagers with a heightened sense of SJ tend to view effective policy implementation and service provision as indicators of responsive governance, feeling respected and supported by the government, thus fostering greater enthusiasm for grassroots governance participation.

Therefore, this paper proposes the following research assumptions:

H3: The interactive effect of political efficacy and villagers’ satisfaction with government performance on the willingness of grass-roots governance is regulated by the sense of social justice. That is, villagers’ willingness to participate in grass-roots governance will be more active when the level of villagers’ satisfaction with government performance and social justice are both high.

Data source and research design

Data source

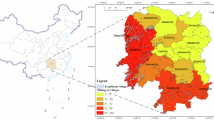

This study utilizes data from the 2019 Chinese Social Survey (CSS), conducted by the Institute of Sociology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Initiated in 2005, the CSS is a nationwide sampling survey project. The CSS 2019 employed a multi-stage stratified sampling method to ensure the representativeness and scientific rigor of the survey. Through household visits, the CSS 2019 covered 31 provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities (excluding the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the Macao Special Administrative Region, and Taiwan Province), reaching 151 districts/counties and 604 villages/neighborhood committees, and conducted comprehensive surveys of over 11,000 households. A total of 10,283 samples were taken for CSS2019. China’s household registration system differentiates between rural and urban household registrations, leading to varied distributions of social resources and living conditions. This study focuses on holders of rural household registrations, specifically those registered as agricultural households, to explore the living conditions of rural residents and the state of grassroots governance in rural areas. By surveying 7031 individuals with agricultural household registrations, this research aims to comprehensively understand grassroots governance mechanisms in rural areas. However, due to the limitations of secondary data availability, this study does not cover urban disadvantaged groups, which restricts the breadth and depth of the research to some extent. The importance of grassroots governance in rural areas cannot be overlooked, as it is crucial for achieving social stability, promoting rural development, and protecting farmers’ rights. Effective rural governance can facilitate the rational allocation of resources, improve the quality of life for rural residents, and lay the foundation for sustainable development in rural areas. Therefore, the final valid sample of this study is 7031.

Variable measurement

Independent variable

Political efficacy

This was measured using three questions from the CSS2019 questionnaire: “People’s participation in political activities is useless and cannot fundamentally influence the government,” “People should obey the government, and subordinates should obey their superiors,” and “The government manages national affairs, and the public does not need to think too much about them.” Responses were rated on a scale from “1 = Strongly agree” to “4 = Strongly disagree.” Higher scores indicate greater political efficacy among villagers.

Dependent variable

Willingness to participate in grassroots governance

This was measured using two questions from the CSS2019 questionnaire: (1) “Are you willing to participate in village (neighborhood) committee elections?” and (2) “Are you willing to participate in major decision-making discussions in your village or workplace?” To ensure consistency and comparability of the data, we reverse-coded the original responses to these two questions, defining “0” as unwilling to participate and “1” as willing to participate. Higher scores indicate a greater willingness to participate in grassroots governance among villagers.

Moderating variables

Satisfaction with government performance

The CSS2019 asked respondents about their satisfaction with government performance in 13 areas, including job security, environmental protection, maintaining public order, combating corruption, and economic development. In this study, we recoded the original responses using a reverse logic scoring system. Specifically, we reordered the evaluation options based on the degree of satisfaction, defining “1” as “very poor,” “2” as “not good,” “3” as “fairly good,” and “4” as “very good.” Higher scores indicate higher satisfaction with government performance among villagers.

Social justice

The CSS2019 asked respondents about their perception of fairness in 11 specific social domains, such as the college entrance examination system, compulsory education, public healthcare, and elderly care. The response options for the social justice variables were “very unfair,” “unfair,” “fairly fair,” and “very fair,” assigned values from 1 to 4, respectively. Higher scores indicate a stronger sense of social justice among villagers. Descriptive statistics for the core variables in the model are presented in Table 1.

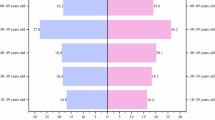

Control variables

This paper compares age (M = 50.724, SD = 14.197, Minimum 22, Maximum 73), gender (0 = female, 1 = male, 42.3% male), education level (M = 3.10, SD = 1.775), The political outlook (0 = non-CPC members, 1 = CPC members, accounting for 6.8%) and socio-economic status (M = 2.37, SD = 1.045) are included in the model as control variables.

Data analysis method

This study uses SPSS 26.0 to process and analyze the data of this study. First, the reliability and validity of the data are tested, and the possibility that the common method deviation might interfere with the research results was excluded; Second, it carries out correlation regression analysis for core variables; Finally, model 1 and model 3 in the PROCESS v4.0 plug-in program of SPSS 26.0 are used to test the moderating effect of villagers’ satisfaction with government performance and the higher-order moderating effect of social justice.

Hypothesis test results and analysis

Common method deviation test

In order to eliminate the interference of common method bias effect on the reliability of the study, this study uses Harman single factor method. The exploratory factor analysis is carried out when all variables are not rotated. The results shows that there are more than 1 principal component (5 in total) with the characteristic value greater than 1, and the variance interpretation rate of the first common factor is 30.987%, less than 40%. It can be seen that there is no serious common method deviation in this study, and subsequent hypothesis test analysis can be carried out.

Research hypothesis test

This study examines the moderating effect of villagers’ SGP on the relationship between PE and willingness to participate in grass-roots governance through model 1 in the PROCESS plug-in program. When we take the average value of information credibility plus or minus one unit of standard deviation score for self-sampling (Bootstrap) test, the test results show (see Table 2) that after controlling gender, age, education level, political outlook and current socio-economic status, PE has a significant positive impact on the willingness to participate in grass-roots governance (β = 0.078, t = 6.427, p < 0.001), indicating that the higher the respondents’ sense of PE, the higher their willingness to participate in grass-roots governance. This is in line with Hypothesis 1. In addition, the interaction between PE and villagers’ SGP is significant (β = 0.070, t = 5.301, p < 0.001), indicating that villagers’ SGP plays a positive moderating role in the direct impact of PE on villagers’ willingness to participate in grass-roots governance. Therefore, the research hypothesis 2 is verified.

Using model 3 in the PROCESS plug-in program, this study continues to test the higher-order moderating effect of SJ. We control variables including gender, age, education level, political status and socio-economic status, and the results show that (see Table 3) the interaction term between PE and SGP significantly impacts the willingness to participate in grassroots governance (β = 0.040, t = 2.422, p < 0.05); the three-level interaction of SJ, PE and villagers’ SGP have a significant impact on the willingness to participate in grass-roots governance (β = 0.066, t = 4.423, p < 0.001). We divide the sense of SJ into high group and low group (M ± SD) to examine the impact of the interaction of PE and villagers’ SGP on the willingness to participate in grass-roots governance. In the group with high sense of SJ, the interaction between PE and villagers’ SGP has a significant positive impact on individual willingness to participate in grass-roots governance (β = 0.083, F = 20.796, p < 0.001); However, in the groups with low sense of SJ the interaction between PE and villagers’ SGP has no significant impact (β = −0.004, F = 0.041, p = 0.840). Then we divide the scores of the two variables into high and low groups to further investigate the impact of individual PE on their willingness to participate in grass-roots governance, and use simple slope test to decompose the high-order moderating effect. The results show that in the low group of SJ, when it comes to villagers with low SGP, their sense of PE has a significant positive impact on the willingness to participate in grass-roots governance (β = 0.052, SE = 0.020, t = 2.593, p < 0.01); While in terms of villagers with high SGP, their sense of PE has no effect on the willingness to participate in grass-roots governance (β = 0.047, SE = 0.024, t = 1.930, p = 0.54). Among the groups with a high sense of SJ, the group with a low degree of SGP has no significant effect on its PE on the willingness to participate in grass-roots governance (β = −0.017, SE = 0.028, t = −0.593, p = 0.553); The group with high SGP has a significant positive impact on the willingness to participate in grass-roots governance (β = 0.098, SE = 0.013, t = 7.350, p < 0.001).

Conclusion and discussion

Main conclusions of the study

Drawing on data from China, this paper delves into the intricate relationship between political efficacy and grassroots governance participation, examining the moderating influences of villagers’ satisfaction with government performance and social justice. The study’s findings are summarized and discussed below.

Initially, the study reveals that PE significantly enhances villagers’ willingness to engage in grassroots governance, aligning with prior research outcomes (Chen 2005). In the context of a post-modernized nation like China, PE emerges as a pivotal driver of grassroots democratic practice. Villagers’ subjective perception of their capacity to influence village committees and cadres proves instrumental in fostering innovation and efficiency in grassroots governance. Nurturing PE empowers villagers to acknowledge their rights and duties as citizens, thereby igniting their enthusiasm and motivation for political involvement. Importantly, augmenting PE contributes to the democratization and institutionalization of grassroots governance, mitigating political apathy and alienation while fostering greater grassroots governance participation.

Furthermore, the study uncovers the constructive role of SGP in moderating the relationship between political efficacy and villagers’ grassroots governance participation. International evidence suggests that citizens exhibit greater propensity for orderly political engagement in environments marked by satisfactory government performance and a conducive political climate, rather than radical participation (Stockemer 2014; Goldfinch et al. 2022). Analysis of China-based data in this study echoes this perspective, underscoring the supportive function of SGP as a resource held by individual villagers in bolstering the impact of PE on grassroots governance participation. Essentially, effective village administration enhances villagers’ confidence in grassroots organizations, fostering greater political engagement driven by perceived benefits. Consequently, government and village-level organizations should continually enhance their organizational capabilities to ensure villagers’ satisfaction with village committee operations, thereby fostering greater grassroots governance participation.

Moreover, the study elucidates the moderating role of SJ by exploring its higher-order impact on the moderating effect of SGP. While previous research noted the absence of a significant effect of SGP on the relationship between support resources and villagers’ participation (Hansen and Ford 2023), this study diverges in its findings. By leveraging SJ perception as a higher-order moderating variable, the study confirms the conditional effect of SGP, revealing that heightened SJ perceptions bolster the positive moderating influence of SGP. Specifically, conditions characterized by elevated SJ perceptions are more conducive to enhancing villagers’ SGP, thereby bolstering their confidence in the political environment and their own PE, thereby fostering greater grassroots governance participation.

Research contributions

Theoretical contributions

First, this discovery broadens the model of PE and grassroots governance participation, addressing inconsistencies in previous studies regarding the relationship and role of PE in political participation. The limited introduction of conditional variables in prior research hindered a refined understanding of the PE-political participation dynamic. Building upon previous work (Moeller et al. 2013; Reichert 2016), this study endeavors to illuminate further avenues for investigation. Moreover, it elucidates the positive influence of PE on grassroots governance participation, offering fresh insights into the micro-foundations of democratic politics in post-modernized nations. This not only enriches the application of PE theory in non-Western societies but also serves as a compelling case study for comparative politics.

Second, the study unveils the constructive moderating role of SGP between PE and grassroots governance participation. This novel theoretical framework offers a nuanced understanding of the interplay between government performance and villagers’ participation, enriching comprehension of how political trust and satisfaction shape political behavior.

Third, the study validates the higher-order moderating role of SJ perception, proposing a more intricate model of political participation motivation. Existing research primarily focused on the direct relationship between SJ perceptions and SGP (Jiang et al. 2022), neglecting to analyze it as a moderating variable. This paper innovatively suggests employing SJ perceptions as a higher-order moderating variable to elucidate the conditions influencing SGP’s role. Recognizing that the impact on political participation willingness arises from the combined influence of SGP and SJ, rather than solely from one factor, is instructive for fostering villagers’ engagement in grassroots governance.

Practical implications

First, there is a necessity to bolster PE, a pivotal psychological determinant fostering citizen engagement in the political sphere. Governments and village committees can facilitate this by organizing seminars, workshops, and online courses to enhance villagers’ understanding of the political process and cultivate their participation skills. Furthermore, establishing and refining mechanisms for villagers’ involvement, such as public hearings and feedback channels, can augment their influence and sense of agency in political affairs. Additionally, ensuring transparency in government decision-making processes, rationale, and outcomes fosters public trust and comprehension of governmental operations.

Second, optimizing government performance is imperative. Governments and village committees should continually refine service processes and enhance service quality, ensuring the accessibility and efficacy of public services. Strengthening communication and engagement with villagers through regular meetings, household visits, and social media interactions fosters a responsive governance environment. Moreover, instituting robust supervision and evaluation mechanisms, including independent oversight bodies and performance assessments, coupled with citizen feedback mechanisms, ensures the efficacy and accountability of government operations.

Third, fostering SJ is essential. Governments must implement measures to mitigate social injustices, including formulating and enacting equitable tax, education, and social security policies to address socio-economic disparities and enhance social welfare. Upholding fair enforcement of laws and policies, ensuring equal treatment before the law regardless of social status, wealth, or background, bolsters trust in the political system. Moreover, governments should promote social participation by supporting civil society organizations, village groups, and volunteer initiatives, empowering villagers to engage in social affairs and influence rural community policy formulation.

Research limitations

First, this study primarily relied on secondary data, which limited the breadth and depth of variable selection. To improve the accuracy and reliability of research, future studies should consider using a combination of primary and secondary data to achieve triangulation of data. Additionally, through this approach, a more detailed analysis of variables such as participation pathways and willingness can be conducted, thereby enriching and refining the theoretical framework proposed in this study.

Second, this study employed cross-sectional data analysis, which provided a snapshot of the current phenomenon but lacked in-depth exploration of causal relationships between variables. To overcome this limitation, future research should incorporate time-series data to reveal the dynamic relationships between variables over time, thereby enhancing the scientific rigor and objectivity of the research findings.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the Chinese Social Survey repository, http://css.cssn.cn/css_sy/zlysj/lnsj/202204/t20220401_5401858.html.

References

Ardèvol-Abreu A, Gil de Zúñiga H, Gámez E (2020) The influence of conspiracy beliefs on conventional and unconventional forms of political participation: the mediating role of political efficacy. Br J Soc Psychol 59(2):549–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12366

Beaumont E (2011) Promoting political agency, addressing political inequality: a multilevel model of internal political efficacy. J Polit 73(1):216–231. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381610000976

Birch S (2010) Perceptions of electoral fairness and voter turnout. Comp Polit Stud 43(12):1601–1622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414010374021

Brügger A, Höchli B (2019) The role of attitude strength in behavioral spillover: attitude matters—but not necessarily as a moderator. Front Psychol 10:1018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01018

Chen J (2005) Popular support for village self-government in China: intensity and sources. Asian Surv 45(6):865–885. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2005.45.6.865

Ding QB (2020) The logic and explanation of “oligarchic politics” in the process of rural governance. Leadersh Sci 14:42–45

Goldfinch S, Yamamoto K, Aoyagi S (2022) Does process matter more for predicting trust in government? Participation, performance, and process, in local government in Japan. Int Rev Adm Sci 89(3):842–863. https://doi.org/10.1177/00208523221099395

Grabe S, Dutt A (2019) Community intervention in the societal inequity of women’s political participation: the development of efficacy and citizen participation in rural Nicaragua. J Prev Inter Community 48(4):329–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2019.1627080

Greenberg J (2020) Law, politics, and efficacy at the European Court of Human Rights. Am Ethnol 47(4):417–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12971

Guy ME, McCandless SA (2012) Social equity: its legacy, its promise. Public Adm Rev 72(s1):S5–S13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02635.x

Hansen MA, Ford NM (2023) Placing the 2020 Belarusian protests in historical context: political attitudes and participation during Lukashenko’s presidency. Nationalities 51(4):838–854. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2022.64

He L, Wang K, Liu T, Li T, Zhu B (2022) Does political participation help improve the life satisfaction of urban residents: empirical evidence from China. PLoS ONE 17(10). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273525

Hou B, Liu Q, Wang Z, Hou J, Chen S (2023) The intermediary mechanism of social fairness perceptions between social capital and farmers’ political participation: empirical research based on masking and mediating effects. Front Psychol 13:1021313. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1021313

Jacobs LR, Cook FL, Carpini MXD (2009) Talking together: public deliberation and political participation in America. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Jiang L, Sun L, Fu Z, Qi R, Tang T, Lin Q (2022) The dilemma of public hearings in land expropriation in China based on farmers’ satisfaction. Front Environ Sci 10:940529. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.940529

Johann D, Steinbrecher M, Thomas K (2015) Personality, political involvement, and political participation in Germany and Austria. Polit Vierteljahresschr. https://webofscience.clarivate.cn/wos/alldb/full-record/WOS:000362145500004

Kahne J, Westheimer J (2006) The limits of political efficacy: educating citizens for a democratic society. Polit Sci Polit 39(2):289–296. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049096506060471

Kanitsar G (2022) The inequality-trust nexus revisited: at what level of aggregation does income inequality matter for social trust? Soc Indic Res 163(1):171–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02894-w

Karp JA, Banducci SA (2008) Political efficacy and participation in twenty-seven democracies: how electoral systems shape political behaviour. Br J Polit Sci 38(2):311–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007123408000161

Kaufman CN (2019) Rural political participation in the United States: alienation or action? Rural Soc 28(2):127–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371656.2019.1645429

Landry PF, Davis D, Wang S (2010) Elections in rural China: competition without parties. Comp Polit Stud 43(6):763–790. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414009359392

Lay JC (2016) She was born in a small town: the advantages and disadvantages in political knowledge and efficacy for rural girls. J Women Polit Policy 38(3):318–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2016.1219590

Lewis C (2007) The Howard government: the extent to which public attitudes influenced Australia’s federal policy mix. Aust J Public Adm 66(1):83–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.2007.00516.x

Li L (2003) The empowering effect of village elections in China. Asian Surv 43(4):648–662. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2003.43.4.648

Liang P, Xiao S (2022) Pray, vote, and money: the double-edged sword effect of religions on rural political participation in China. China Econ Rev 71:101726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101726

Liu YD, Wang Y (2022) Research on the innovative mechanisms of rural ideological and political work in the new era. China Rice 28(01):127

Ma CC, Ma H (2018) Changes and experiences in China’s rural governance over forty years. Theory Reform 6:21–29

Martinez-Bravo M, Padró I Miquel G, Qian N, Yao Y (2022) The rise and fall of local elections in China. Am Econ Rev 112(9):2921–2958. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20181249

Meesuwan S (2016) The effect of Internet use on political participation: could the Internet increase political participation in Thailand? Int J Asia Pac Stud 12(2):57–82. https://doi.org/10.21315/ijaps2016.12.2.3

Miao H (2023) Types of public participation and their effect on satisfaction with local public services in China. Asian Surv 63(6):851–877. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2023.2007496

Moeller J, de Vreese C, Esser F, Kunz R (2013) Pathway to political participation. Am Behav Sci 58(5):689–700. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213515220

Ng CS, Chiu MM, Zhou Q, Heyman G (2020) The impact of differential parenting: Study protocol on a longitudinal study investigating child and parent factors on children’s psychosocial health in Hong Kong. Front Psychol 11:1656. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01656

Oliver RL (1980) A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J Mark Res 17(4):460–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378001700405

Osborne D, Yogeeswaran K, Sibley CG (2015) Hidden consequences of political efficacy: testing an efficacy–apathy model of political mobilization. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol 21(4):533–540. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000029

Reichert F (2016) How internal political efficacy translates political knowledge into political participation: evidence from Germany. Eur J Psychol 12(2):221–241. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v12i2.1095

Rosenstone SJ, Hansen JM, Reeves K (2003) Mobilization, participation, and democracy in America. Longman, New York

Shi C, Dutt A, Jacquez F, Wright B (2023) Transformative impacts of a civic leadership program created by and for refugees and immigrants. J Community Psychol 51(5):2300–2318. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.23028

Stockemer D (2014) What drives unconventional political participation? A two-level study. Soc Sci J 51(2):201–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2013.10.012

Strandberg K, Backström K, Berg J, Karv T (2021) Democratically sustainable local development? The outcomes of mixed deliberation on a municipal merger on participants’ social trust, political trust, and political efficacy. Sustainability 13(13):7231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137231

Su F, Ran T, Sun X, Liu M (2011) Clans, electoral procedures and voter turnout: evidence from villagers’ committee elections in transitional China. Polit Stud 59(2):432–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00881.x

Tong D (2010) Chinese-style democracy. Tianjin People’s Publishing House, Tianjin

Tyler TR (2023) The organizational underpinnings of social justice theory development. Soc Justice Res 36:371–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-023-00414-w

Van de Graaf C (2020) Procedural justice perceptions in the mediation of discrimination reports by a national equality body. Int J Discrim Law 20(1):45–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1358229120927921

Van Zomeren M, Saguy T, Schellhaas FM (2012) Believing in “Making a difference” to collective efforts: participative efficacy beliefs as a unique predictor of collective action. Group Process Intergroup Relat 16(5):618–634. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430212467476

Wang C, Zhang X (2024) Governance capacity, social justice, social security, and institutionalized political participation in China: a moderated mediation model. Chin Public Adm Rev. https://doi.org/10.1177/15396754241252978

Wang X (2008) Making sense of village politics in China: institutions, participation, and governance (Order No. 3342535). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. 304597041. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/making-sense-village-politics-china-institutions/docview/304597041/se-2

Wilking JR (2010) The portability of electoral procedural fairness: evidence from experimental studies in China and the United States. Polit Behav 33(1):139–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9119-8

Wilking JR, Zhang G (2017) Who cares about procedural fairness? An experimental approach to support for village elections. J Chin Polit Sci 23(2):177–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-016-9451-x

Xu Y (2016) Reinstating autonomy: an exploration into the effective forms for realizing villager autonomy. J Chin Gov 1(1):157–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/23812346.2016.1138703

Yan J (2007) The dilemma and solution of democracy: reflections on the experience of political reform in China. Learn Explor 2007(02):80–84

Ye L, Wu Z, Wang T, Ding K, Chen Y (2022) Villagers’ satisfaction evaluation system of rural human settlement construction: empirical study of Suzhou in China’s rapid urbanization area. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(18):11472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811472

Zhang T, Zhang L, Hou L (2015) Democracy learning, election quality and voter turnout. China Agric Econ Rev 7(1):143–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/caer-09-2013-0128

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Weizhen Zhan and Zhenwu You contribute equally to this research. All authors are in agreement with the content with the content of the manuscript. Weizhen Zhan and Zhenwu You conceived of the idea, implemented the formula and carried out the case studies. Weizhen Zhan and Zhenwu You contributed to the idea, implementation and case study design. Weizhen Zhan and Zhenwu You interpreted the results based on the fault tree diagram. Weizhen Zhan led the writing of the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhan, W., You, Z. Factors influencing villagers’ willingness to participate in grassroots governance: evidence from the Chinese social survey. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1051 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03574-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03574-5