Abstract

This study investigates the mechanism behind the generation of behavioral risk among decision-makers in financial institutions. We start by examining the general mechanism of organizational decision-making behavior, then analyse organizational errors and human errors in the decision-making process, and subsequently define the connotations and types of organizational decision-makers’ behavioral risk. The study also identifies the necessary conditions for the emergence of decision-making behavioral risk. We construct a model to analyse the behavioral risk of decision-makers in financial institutions. We also develop motivation and utility functions for organizational decision-makers’ behavior, examine the relationship between factors in the utility function, and explore how organizational decision-makers adjust their behavior in various situations to maximize utility. The paper also analyses a case study involving the China Everbright Group (CEG). The study revealed the following: ① The conditions for the occurrence of organizational decision-makers’ behavioral risk in financial institutions mainly stem from the conflict between organizational interests and decision-makers’ interests, the failure of organizational contextual constraints, and the lack of organizational decision-making auditing and feedback mechanisms. ② Organizational decision-makers tend to exhibit inappropriate decision-making behaviors when they overestimate their own abilities in comparison to the benefits they expect. ③ Financial institutions should avoid organizational errors to reduce the likelihood of behavioral risk by increasing the cost of organizational decision-makers’ behavior. Our study proposes measures to mitigate the risk of inappropriate behavior by financial institutions through scientific decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the global financial crisis in 2008, the misconduct risks faced by financial institutions have increasingly become a focus of behavioral supervision by financial regulatory agencies in various countries. In recent years, misconduct risk has increasingly emerged as a new type of financial risk, one that is receiving high levels of attention from both domestic and international financial industries and regulatory agencies. This risk encompasses various core business activities of financial institutions, and the underlying causes are characterized by complexity, intersection, and concealment (Awrey, 2012). In 2023, domestic financial institutions were fined a total of 8139 times (accounting for 60.82% of all fines issued to financial institutions), a year-over-year increase of 32%, with a total penalty amount of 2.751 billion yuan and a year-to-year increase of 29.7%. The number and amount of fines have increased significantly. Chinese financial regulatory authorities have consistently emphasized the importance of regulating the behavior of different financial institutions, effectively addressing illegal and irregular activities, and preventing misconduct risk. However, although the rectification of chaos in the financial industry has achieved certain results, the need for supervision of misconduct risk in the financial industry remains pressing. To regulate and govern misconduct risk in financial institutions, financial regulatory agencies urgently need to clarify the connotations and characteristics, causes and generation mechanisms, and transmission paths of such risks.

The Financial Services Authority and the European Systemic Risk Board have collaborated to define the meaning of misconduct risk. They understand such risk as the potential for detrimental outcomes resulting from the inappropriate behavior of financial institutions and their staff, which can have significant adverse effects on external parties (Ramanujam and Goodman, 2003). Currently, regulatory bodies and both domestic and foreign scholars are increasingly acknowledging the importance of comprehending the root causes of misconduct in financial institutions. They have recognized that this understanding is essential for improving the efficiency and accuracy of risk governance in these institutions (Cumming and Dannhauser et al., 2015).

At present, traditional research on the causes of misconduct risk in the academic community has focused on the following three areas. (1) Scholars have analysed the influencing factors of misconduct, including objective factors (e.g., internal control misconduct, the institutional design of financial institutions, and imperfect financial institution governance (Aebissa and Dhillon et al., 2023) as well as subjective neglect of business behavior (Ramanujam and Goodman, 2003)), and subjective factors, (e.g., artificially manipulating transactions, the one-sided pursuit of profits, and ethical misconduct (Nesvijevskaia and Ouillade et al., 2021). (2) Scholars have applied complexity theory to explore the elements of the financial system (Cooper, 2011), the design of financial products, and the transactions of financial institutions (Carretta and Farina et al., 2017). Such research has suggested that complexity exacerbates information asymmetry among various entities in the financial market, thereby inducing proactive concealment and internal fraud behavior in financial institutions (McConnell, 2017). This complexity is closely related to the internal governance deficiencies of financial institutions (Gottschalk and Castro et al., 2022). (3) A number of scholars have attempted to explore the causes of misconduct from the perspective of psychological contracts between financial institution decision-makers and consumer decision-makers (Aydemir, 2014; Mata and Mata et al., 2023), whereas others have studied the logic and interaction mechanism between cultural capital and misconduct in financial institutions from the perspectives of sociology and organizational transactions (Nguyen and Hagendorff et al., 2016).

The cited research, which is focused on organizational errors, can partially explain the causes of misconduct risk. However, the strategic orientation and operational behavior of financial institutions are often determined by their organizational decision-makers. Why do organizational decision-makers make inappropriate decisions? When do they make such decisions? What roles do human error and organizational error play in this process? The research on these issues has not yet reached clear conclusions. This research combines the study of organizational errors and human errors and draws on other research on decision-maker behavior risk and employee fraud as decision-making mechanisms. Taking the general mechanism of organizational decision-making behavior as research entry point, this study constructs an organizational decision-maker behavior risk analysis model for financial institutions that models the generation mechanism, occurrence conditions, decision-maker motivation, and behavior adjustment of misconduct risk, thus providing a reference basis for the supervision and governance of misconduct risk in financial institutions. The study incorporates the research of Lin et al. (2023) on organizational and human errors as well as the research of Cusin and Flacandji (2022) and Fata and Martens (2017) on decision-maker behavior risk and employee fraud as decision-making mechanisms. This study constructs an organizational decision-maker behavior risk analysis model for financial institutions using the general mechanism of organizational decision-making behavior as the starting point for the research. This model reveals the decision-maker motivation, occurrence conditions, and behavior adjustment of such conduct risk, providing a reference basis for the supervision and governance of misconduct risk in financial institutions.

Literature review

Theoretical research on organizational and human error

Reason (1995) first proposed the concept “Organizational Errors” in his book “Human Errors”. He argued that organizational errors are the most hidden and threatening “latent errors” in the system. Goodman and Ramanujam et al. (2011) emphasized that organizational error is misconduct occurring when key or multiple members stray from the organization’s set procedures or rules. Van Dyck and Frese et al. (2005) suggested that organizational errors are systematic biases that objectively exist within an organization. Reason (1995) believed that any technical failure, human error, or violation in a complex system is only a necessary condition for risk or accident rather than a sufficient condition, whereas implicit errors within the system, such as management errors or decision-making errors, are the most threatening. Ruchlin and Dubbs et al. (2004) specifically noted that the root cause of accidents is often management and organizational errors, and an important manifestation of such organizational errors is the level of decision-making ability of organizational leaders. Glavas (2016) proposed that organizational error is a type of knowledge-based human error that is reflected in organizational system defects, insufficient training, poor organizational or corporate culture, and incorrect decision-making by managers. Grabowski and Roberts (1996) suggested that organizational errors are the root cause of individual errors and originate in the fragility of the organization and the scarcity of organizational resources. From the perspective of organizational ethics, Candi and Melia et al. (2019) explored how to prevent organizations from making inappropriate choices on the basis solely of their interests, which reflects the moral quality of the organization.

In cognitive psychology, human behavior is an external manifestation of internal cognition (Qi and Chiaro et al., 2023), and the essence of human error is human error in information processing (Passant and Laublet et al., 2009). Grabowski and Roberts (1996) specifically noted that accidents or risks occur due to defects, loopholes, or deficiencies in the system, which can lead to human errors. Read and Shorrock et al., (2021) studied the causes of human error from the perspective of the work environment and personal skills and suggested that there are factors that lead to human error in any task and, further, that these factors emerge as the task is determined rather than when an event occurs. Sobanova and Kudinska (2023) analysed human error from the perspective of the psychology and mindset of bank employees and reported a significant relationship between the knowledge accumulation, work attitude, and attention of bank employees and the causes of human error.

The cited research reveals that the decision-making errors or errors of organizational managers—the occurrence of human errors—are closely related to the defects or loopholes within the organizational system; that is, organizational errors are an important cause of human errors, and human errors are a manifestation of organizational errors. For financial institutions with operational risk, the appearance of misconduct risk is reflected in various violations of financial services, product sales, and financial transactions by financial institutions and their employees. The risks caused by deficiencies or loopholes in corporate governance, processes, systems, and internal controls of financial institutions are primarily organizational errors. The organizational errors of financial institutions are the main factors that lead financial decision-makers to make incorrect decisions or human errors.

Behavioral decision theory and its applications

Decision theory is a discipline that explores decision-making processes, criteria, objectives, and methods, covering systems theory, operations research, and computer science. After the 1950s, decision-making theory evolved into rational decision-making theory and behavioral decision-making theory. Behavioral decision-making theory has experienced profound development over time. This development led to the establishment of the theories of expected utility and unexpected utility (Yaari, 1987). Additionally, researchers in the field have contributed to the development of modern decision-making theory in scenarios characterized by ambiguous subjective uncertainty (Yoshimura and Ito et al., 2013).

Dhami and Al-Nowaihi et al., (2019) argued that decision-makers are often in a state of bounded rationality, where the uncertainty of information, complexity, unknown risks, and changes in initial goals can constrain and affect their rational decision-making. The final behavioral decision choices of decision-makers may deviate from those based on maximizing the utility function of rational individuals. Tversky and Kahneman (1991) proposed in their discourse on heuristic bias theory that decision-makers may experience heuristic cognitive biases when facing complexity or ambiguity, with only varying probabilities of such biases occurring. Raven and McCullough et al., (1994) proposed that, owing to the incompleteness of information obtained by decision-makers, differences in information costs, individual characteristics, and environmental differences, the satisfaction of different decision-makers with decision-making solutions varies greatly. Ashraf and Zheng et al. (2016) suggested that the excessive risk-taking behavior of financial institutions stems from the irrational behavior of financial managers, who generally have optimistic psychological biases. In the modern financial risk chain, for financial decision-makers, moral risks, and ethical crises are inevitable (Walumbwa and Maidique et al., 2014), and owing to the diversity, uncertainty, and cognitive limitations of practical problems, the decision-making process often depends on decision-makers’ psychological behavior and risk attitudes (Congjun and Xinping et al., 2007). DOO and Ha (2011) conducted an analysis of decision-makers’ preference choices; their analysis was grounded in the cognitive psychological processes of decision-making. They posited that the configuration of prospects can influence decision-makers. Specifically, it can affect how decision-makers allocate their attention. Furthermore, it can shape the direction of their preferences. In recent years, behavioral decision-making theory has gradually been widely applied in the financial field, but it has focused on the motivation of financial consumption and investment behavior (Shneor and Munim, 2019); organizational decision-making in financial institutions has not been extensively explored in applied research. In the literature, there is a lack of research on the mechanism of misconduct risk generation in financial institutions that uses the theories of organizational error and human error.

In summary, the process of organizational decision-making is a systematic one involving complex situations and the comprehensive judgment of multisource information. The process of organizational decision-making is strongly influenced by the uncertainty of decision-makers themselves, which can lead to decision-making behavior risks. In the context of financial institutions, the recurrent emergence of misconduct risk events underscores the intricate nature of the prevailing financial environment and financial system in China.

These events also serve as stark reminders of the inherent complexity of the financial sector. Furthermore, they highlight the uncertainty of the financial risk that both financial institutions and their organizational decision-makers are confronted with. Exploring how to effectively avoid misconduct risk in financial institutions from the perspective of the decision-making behavior of organizational decision-makers is a necessary research direction.

Methods

Research framework

On the basis of the above analysis, this study’s research framework is as follows. First, with the focus on organizational error and human error, behavioral decision-making theory is used to explore the general mechanism of organizational decision-maker behavior, organizational error, and human error. Subsequently, a specialized conduct risk analysis model is constructed for decision-makers in financial institutions. This model is designed to investigate the root causes of inappropriate behavior risk within financial institutions, with a focus on the perspective of organizational decision-makers. Finally, we propose several suggestions to help financial institution organizational decision-makers avoid risks in their decision-making behavior (Fig. 1).

Analysis of the risk mechanisms of decision-makers in financial institutions

With the innovative development of information technology, the complexity of business systems and processes of financial institutions has increased with the continuous proliferation of financial systems, products, and data. However, the digitization of the financial system has not reduced the role of people in the system. Behind its operational level, the financial system precisely reflects the influence and role of human factors (Curti and Migueis, 2023). The behavior of managers and employees within financial institutions is influenced by a variety of factors; individual cognitive perspectives, knowledge acquisition, skill application, psychology, and personality traits all play pivotal roles in shaping the actions of such individuals. Additionally, organizational situation factors, including the level of corporate governance, corporate culture, financial thinking, technology application, and broader financial environment, significantly impact their conduct (Curti and Migueis, 2023). This study takes the general mechanism of organizational decision-making as its research entry point, analyses the decision-making behavior risks (and their generation conditions) of decision-makers in financial institutions, and provides a mechanism analysis and theoretical basis for subsequent modeling.

Analysis of the mechanism of organizational decision-making behavior in financial institutions

“Organizational decision-making” refers to the choices or adjustments made by an organization as a whole or as a part of an organization regarding future activities for a certain period of time (González-Torres and Gelashvili et al., 2023), which is the opposite of individual decision-making. Organizational decision-making involves a systematic process in which decision-makers consider the organization’s resources, opportunities, threats, strengths, and weaknesses within their specific environment. Drawing on their knowledge, experience, and skills, decision-makers evaluate these factors to inform their decisions. This evaluation serves as the basis for developing or adjusting the organization’s decision-making plan, which is designed to align with the organization’s goals and risk preferences. Because organizational decision-making behavior relies on decision-makers and internal members within the organization, it is inevitably influenced by the individual characteristics of decision-making participants, such as their psychological characteristics, stress tolerance, individual emotions, information mastery, and values.

For financial institutions, changes in the organizational situation and financial environment require decision-makers to make decisions in the shortest possible time, which requires financial institutions to grant decision-makers corresponding decision-making and choice rights. When organizational decision-makers make choices and decisions, their individual characteristics, interest biases, and value orientations play crucial roles. These factors, along with others, can greatly impact the effectiveness of decision-making processes. Therefore, the focus of this research is on how to effectively avoid and prevent conduct risks that are detrimental to the overall organizational interests of financial institution decision-makers during the decision-making process. To explore the conduct risk of organizational decision-makers, it is necessary to first analyse the general behavioral mechanisms of organizational decision-making (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 shows that the influencing factors of organizational decision-making behavior mainly include psychological factors, knowledge experience and skill factors, and organizational situational factors. During their development, organizational decision-making plans must fully consider the divergence that may exist between individual risk preferences and those of the organization. The adjustment of these differences is crucial. The objective is to ensure that the decision-making plans formulated are congruent with the interests of the organization.

An effective organizational decision-making process should establish an “organizational decision-making audit” mechanism to conduct compliance and feasibility audits on the basis of organizational decision-making and the achievement of decision-making goals so as to create an important “third line of defense” and avoid and reduce the conduct risks of organizational decision-makers. In general, the decision-making process of an organization should involve the following elements.

Element 1: Organizational decision-makers of financial institutions should have the basis, ability, and decision-making power to propose decision-making plans and alternative plans.

Element 2: Organizational decision-makers of financial institutions should consider the conduct risks, costs, and related responsibilities that may arise from decision-making actions when proposing decision-making plans.

Element 3: After implementation, the organizational decision-making plan of a financial institutions should allow the financial institution and organizational decision-makers to dynamically adjust the plan.

Analysis of organizational and human factor errors in the decision-making process of financial institutions

The process of organizational decision-making involves systematic judgment of multisource information in complex situations and is characterized by complexity, high risk, and multisource informatization. The process is strongly influenced by the uncertainty of decision-makers themselves and the organizational situation, which can trigger decision-making behavior risks for decision-makers. The conduct risk of organizational decision-making includes both human error and organizational error.

From an individual perspective, the organizational decision-making process of financial institutions is influenced by the psychological factors of decision-makers themselves, individual interests and motivations, knowledge mastery, personality, and other factors. The human error causes mainly include the following types: decision-making errors caused by decision-makers lacking professional knowledge or vision, risk perception ability and financial market prediction; improper decisions made by decision-makers due to personal biases, emotions, personal interests; and other types.

From the perspective of the organizational situation, the decision-making process of financial institutions is influenced by factors such as corporate governance and culture, regulations and process design, internal control, and the risk management level. The main manifestations of organizational errors include a lack of effective communication and coordination mechanisms for decision-making. Decision-making audit mechanisms may also be inadequate. These deficiencies can lead to information blockages. They can also lead to disharmony in the decision-making process. Furthermore, a failure of decision-making audits to fulfill the role of the “third line of defense” can occur. Financial institutions often have not clearly defined the rights and responsibilities of group decision-makers, resulting in unclear responsibilities and inadequate decision-making.

Conditions for generating conduct risks among decision-makers in financial institutions

When financial institutions make organizational decisions, organizational decision-makers may engage in inappropriate decision-making behaviors. These behaviors can deviate from or fail to align with the interests of the organization. Decision-makers may prioritize seeking individual benefits over collective interests.

Such actions introduce uncertainty regarding potential financial losses for the institution. This phenomenon is referred to as “organizational decision-maker behavior risk.” This risk can be divided into intrinsic risk and extrinsic risk. Extrinsic risk can also be understood as systemic risk consists mainly of external organizational situational factors, such as the financial market environment, financial regulatory environment, and legal regulatory environment. This risk has the characteristics of objectivity, complexity, and difficulty of control. Intrinsic risk is due mainly to the subjective risk of organizational decision-makers in the selection of decision-making basis, target selection, and scheme determination. Improving the organizational situation and implementing decision auditing mechanisms can help reduce and avoid this risk to a certain extent.

This study focuses on decision-maker behavior risk: What are the initial factors and basis for the occurrence of inappropriate decision-making behavior? How can the motivation intensity of organizational decision-makers who engage in these inappropriate decision-making behaviors be measured? How do financial institutions guide decision-makers to adjust their behavior in the face of potential risks in decision-making? The research is based on the analysis of the behavioral mechanisms of organizational decision-makers, which can determine the necessary conditions for their conduct risks, more specifically as follows:

Condition 1: Conflicts or significant deviations between the interests of decision-makers and the interests of the organization (human error).

Condition 2: Internal and external factors in the organizational situation cannot effectively constrain decision-makers and their decision-making processes (organizational errors).

Condition 3: After a decision proposal is made, there is a lack of effective decision auditing and feedback mechanisms to constrain and intervene in decision proposals with significant flaws or deviations (organizational errors).

Construction of a risk analysis model for decision-makers in financial institutions

Two important sources of misconduct risk in financial institutions are adverse selection and ethical misconduct in information economics (Kamran and Chaudhry et al., 2016), and these two types of risk source are closely related to the interests of organizational decision-makers.

Hypotheses for constructing risk models for decision-makers in financial institutions

Financial institutions may face conflicts when their organizational value orientation diverges from that of their decision-makers. Corporate governance, culture, process norms, and internal control compliance may fail to effectively constrain organizational decision-makers. This inability to constrain can lead to what are termed “organizational errors”. Organizational decision-makers may then engage in inappropriate behaviors, which can be advantageous to the decision-makers themselves or to a small group but not to the organization as a whole. These actions are classified as “human errors”. Such behaviors can ultimately result in risk for organizational decision-makers. Any decision plan that considers only one type of interest cannot achieve a dynamic balance between the two types of interests and may lead decision-makers and organizations into repeated vicious games, thereby invisibly increasing the decision-making and incentive supervision costs of the organization.

Assumption 1: The expectation of financial institution owners is that the decision-making motivation of organizational decision-makers should be based on maximizing organizational interests, whereas the decision-making motivation of organizational decision-makers is to maximize the utility of decision-makers.

Assumption 2: The organizational situation and decision-making audit mechanism constructed by financial institutions are not entirely effective for organizational decision-makers. This assumption presupposes the following. The development and implementation of process standards and internal control compliance systems of financial institutions cannot cover all situations, and there may be varying degrees of defects. Organizational decision-makers will not fully implement process specifications and will selectively execute them.

Assumption 3: For organizational decision-makers, the marginal utility of benefits such as performance incentives and reward acquisition (p), increased decision-making power (r), and decision-maker rank promotion (j) decreases, and the cost of obtaining various benefits for decision-makers is equal; that is, the marginal cost of obtaining various utilities is equal.

When an organizational decision-maker makes a decision, the solution set \({P}_{e}\{{D}_{i}\}\) is D{Di}, which refers to the profit function of the {Di} financial institution when the organizational decision-maker chooses the solution, and \({U}_{m}\{{D}_{i}\}\), which refers to the utility function of the decision-{Di}maker when the organizational decision-maker adopts the strategy. T(C) refers to the cost incurred by organizational decision-makers when taking measures that are beneficial to their own interests but detrimental to the interests of financial institutions. \(R(a)\) is an evaluation of the decision-making ability of organizational decision-makers, and \(U(p,r,j)\) is the utility function of organizational decision-makers, where p refers to performance incentives and reward acquisition, r represents increasing decision-making power, and j represents promotion in job rank.

Steps for conducting risk analysis of financial institution decision-makers

Step 1: Analysis of the driving forces in inappropriate decision-making behavior. When there are different solutions between \(Max{P}_{e}\{{D}_{i}\}\) and \(Max{U}_{m}\{{D}_{i}\}\), conflicts and biases arise between the interests of financial institutions and organizational decision-makers. These conflicts and biases are inevitable and cannot be completely avoided.

Step 2: Construction of the improper decision behavior selection function. \(T(C)=\Delta {U}_{m}\), where \(\Delta {U}_{m}\) represents the change in utility generated by organizational decision-makers taking measures that benefit themselves but not financial institutions, and where \(T(C)\) represents the behavioral cost of organizational decision-makers. Organizational decision-makers measure the behavioral cost and utility increment of their decisions. Only when the utility increment exceeds their behavioral cost, i.e., when \(\Delta {U}_{m} \,>\, T(C)\), do organizational decision-makers choose behaviors that are beneficial to their own interests but not to the interests of their financial institutions—that is, improper decision-making behavior (human error).

Moreover, the organizational situation and decision-making audit mechanism in financial institutions increase the additional cost of decision-makers choosing inappropriate behavior, and this cost of behavior is positively correlated with the completeness of the organizational situation and the effectiveness of the decision-making audit mechanism. The more effective the internal corporate governance, external oversight, and auditing of decision-making are, the lower the probability of organizational failure. Moreover, the cost of inappropriate behavior by organizational decision-makers is greater. In this case, organizational decision-makers are more likely to abandon inappropriate decision-making behaviors. Owing to the objective existence of conflicts of interest between the organizational interests of financial institutions and decision-makers, effectively reducing \(\Delta {U}_{m}\) incremental changes in utility is a high priority for financial institutions. By fostering a positive organizational culture and implementing performance-based incentive strategies, financial institutions can effectively mitigate and eliminate conflicts of interest between themselves and organizational decision-makers. This will ultimately enhance the alignment of their interests.

Step 3: Construct the intensity of motivation for inappropriate decision-making behavior selection. \(S=\Delta T(U)-T(C)\), where the essence of \(S\) is the critical judgment threshold for organizational decision-makers to engage in inappropriate behavior. On the basis of the driving factors of improper decision-making behavior mentioned in step 1, it can be concluded that \(S \,>\, 0\) improper decision-making behavior occurs when the increase in the utility of organizational decision-makers exceeds their misconduct costs.

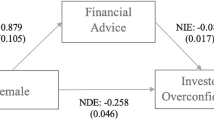

The research defines the utility function of organizational decision-maker interests as a function of variable elements, such as performance incentives and reward acquisition p, increased decision-making power r, and rank promotion j. Whether the utility of each variable element can satisfy organizational decision-makers depends on the evaluation of their own abilities by organizational decision-makers R(a).

Results

There are three main states between the organizational decision-makers’ own assessment of competence and benefit-utility expectations, as follows:

State 1: R(a) = U(p, r, j)- Organizational decision-makers assess their own abilities and anticipate their own benefits and utility (balanced)

In this state, \(\frac{{du}}{{dr}}=\frac{{du}}{{dp}}=\frac{{du}}{{dj}}\); that is, the marginal utility of each benefit element is the same. According to Hypothesis 3, it could be inferred that the \((p,r,j)\) behavioral costs for organizational decision-makers to obtain various benefits are equal; that is, the marginal costs are equal. The utility function of the elements of interest for organizational decision-makers can be expressed as \(U(p,r,j)=U(p)+U(r)+U(\,j)\). Moreover, under the constraint of a certain total cost of decision-making behavior, the condition for the maximum utility of the decision-makers’ benefit factors to be established is also \(\frac{{du}}{{dr}}=\frac{{du}}{{dp}}=\frac{{du}}{{dj}}\).

Under current conditions, organizational decision-makers believe that the benefits and utility they receive match their ability estimates. If organizational decision-makers make any adjustments to the structure of various interest factors, their overall benefit utility will decrease. Thus, the current state is the optimal balance state for organizational decision-makers. Moreover, due to this condition, financial institutions have provided organizational decision-makers with the most matching benefits and utility, resulting in a win‒win situation. In this state, organizational decision-makers will rarely generate inappropriate behavior motives. From the perspective of game theory, this state forms a Nash equilibrium.

State 2: \(R(a)\,{\boldsymbol{ > }}\,U(p,r,j)\)- Organizational decision-makers’ self-evaluations of their own abilities are greater than their expected self-interest utility (imbalanced)

In this state, when \(\frac{{du}}{{dp}}=\frac{{du}}{{dr}}=\frac{{du}}{{dj}}\) (i.e., the utility of the benefit elements is given), organizational decision-makers believe that the utility of the benefits they receive does not match their own abilities, nor that can they improve utility by adjusting the structure of the benefit elements. Moreover, the cost of acquiring various benefit elements is equal (Hypothesis 3). Therefore, if organizational decision-makers are in this imbalanced state for a long period of time, efforts may occur to achieve a “negative” balance.

In this state, when \(\frac{{du}}{{dp}},\frac{{du}}{{dr}}\,{\rm{and}}\,\frac{{du}}{{dj}}\) are not equal, organizational decision-makers can improve the effectiveness of benefits by adjusting the structure of interest factors. The relevant adjustment scenarios are shown in Table 1 (for convenience, the adjustment plan for the benefit elements of organizational decision-makers is limited to the boundary between the highest and lowest marginal utility).

Adjustment scenario 1: \(\frac{{du}}{{dr}} > \frac{{du}}{{dp}}\)- The marginal utility pursuit of decision-making rights is greater than the marginal utility of performance incentives and reward acquisition

In this scenario, the performance incentives and reward acquisition of organizational decision-makers have reached a satisfactory level, and there is a need to continue increasing decision-making power; that is, organizational decision-makers believe that the importance of decision-making power exceeds the importance of performance incentives and reward acquisition. To improve overall utility, decision-makers may partially abandon or reduce their pursuit of performance incentives and rewards to shift to the pursuit of decision-making rights, thereby achieving a new equilibrium state, i.e., \(\frac{{du}}{{dr}} = \frac{{du}}{{dp}} = \frac{{du}}{{dj}}\). In reality, this new equilibrium state may manifest mainly as misconduct, such as the transfer of performance incentives and rewards (such as bribery), to gain more decision-making power.

Adjustment scenario 2: The marginal utility pursuit of job rank promotion is greater than the marginal utility of performance incentives and reward acquisition

In reality, organizational decision-makers may deviate from the operational interests of their financial institutions, focus their operational resources and energy on further improving their positions, and may even engage in misconduct, such as falsifying business performance records.

Adjustment scenario 3: \(\frac{{du}}{{dp}} > \frac{{du}}{{dr}}\)- The marginal utility pursuit of performance incentives and reward acquisition is greater than the marginal utility increase of decision-making power

In this context, organizational decision-makers have reached a level of satisfaction with their decision-making power while having a higher demand for performance incentives and reward acquisition. In this context, the adjustment behavior of organizational decision-makers may be reflected in misconduct, such as using their authority to misappropriate and occupy funds and engaging in fraudulent practices. This behavior occurs very frequently in financial institutions.

Scenario 4: \(\frac{{du}}{{dr}} > \frac{{du}}{{dp}}\)- The marginal utility pursuit of job rank promotion is greater than the marginal utility of increasing decision-making power

In this context, organizational decision-makers have reached a level of satisfaction with their decision-making power and have a greater demand for career advancement. In reality, this satisfaction may be reflected in the use of decision-making power to handle special affairs or engage in inappropriate behavior, such as allocating resources to leaders, employees, or other influential departments, to expand one’s influence and achieve the goal of rank promotion.

Adjustment scenario 5: \(\frac{{du}}{{dr}} > \frac{{du}}{{dp}}\)- The marginal utility pursuit of performance incentives and reward acquisition is greater than the marginal utility of rank promotion

In this context, organizational decision-makers have reached a level of satisfaction with their own job advancement while having a higher demand for performance incentives and reward acquisition. In reality, this type of behavioral adjustment may be reflected mainly in organizational decision-makers utilizing their rank advantages to obtain greater performance incentives and rewards.

Adjustment scenario 6: \(\frac{{du}}{{dr}} > \frac{{du}}{{dp}}\)- The marginal utility pursuit of decision-making power is greater than the marginal utility of rank promotion

In this context, the promotion of organizational decision-makers has reached a level of satisfaction, and there is a greater demand for decision-making power. In reality, this type of behavioral adjustment manifests mainly as organizational decision-makers using their job positions to further expand their influence and gain more decision-making power (i.e., using power for personal gain).

When organizational decision-makers adjust their behavior and improve their overall utility through the above adjustments, they will repeat the \(U(p,r,j)\) situation of state 1 \(R(a)\) = \(U(p,r,j)\) and state 2 \(R(a)\) >; if state 3 \(R(a)\) > \(U(p,r,j)\) occurs, the specific analysis is as follows.

State 3: \(R(a)\) < \(U(p,r,j)\)- Organizational decision-makers’ self-evaluation of their own abilities is less than their expected self-interest utility (imbalanced)

Under the condition that the benefits and utility provided by financial institutions to organizational decision-makers are greater than their own contributions, organizational decision-makers may experience two new “balances”; in the first, they seek to enhance their own abilities and increase their contributions through learning to achieve a positive “balance” between their own abilities and the benefits and utility they benefit from. The second approach is to continue to settle for the status quo according to the belief that financial institutions should give their decision-makers more compensation and to seek another distorted “balance” psychologically. For the second type of abnormal “balance”, financial institutions need to fully leverage the functions of performance allocation and assessment guidance, internal supervision, and other functions. In organizational situations, one should seek to encourage organizational decision-makers to shift towards a positive balance by enhancing their value for investment.

Discussion and reflection on a specific case

On the basis of the preceding research, the occurrence of conduct risk among organizational decision-makers in financial institutions mainly stems from three conditions: conflicts between organizational interests and decision-maker interests, ineffective organizational situational constraints, and a lack of decision-making auditing and feedback mechanisms. There are many examples of far-reaching relevance to the study of misconduct risk by financial decision-makers, with the case of the China Everbright Group (CEG) being a more typical one.

CEG is a state-owned large-scale integrated financial holding group distinguished by integrated finance, industry-integrated cooperation, and other distinctive characteristics and active in both mainland China and Hong Kong. Since 2021, CEG has been accused of a series of legal and disciplinary violations involving its top management. In March 2021 and July 2023, two consecutive chairpersons of CEG were dismissed for serious violations of law and discipline. In July 2022, the Party Secretary and Chief Executive Officer of CEG were placed under supervisory investigation for suspected serious offenses. In the following analysis, the decision-maker behavioral risk of CEG will be examined in relation to the three conditions that contribute to the emergence of organizational decision-maker behavioral risk.

First, the executives of the CEG, leveraging their leadership position, made decisions on the basis of personal self-interest to fulfill their own needs and preferences. Their financial decision-making misconduct was characterized by a high level of secrecy, sophistication, and potentially negative consequences. This behavior aligns with Misconduct Risk Generation Condition 1: “Conflict or significant deviations between the interests of the decision-maker and the interests of the organization (human error)”. From the perspective of financial institutions’ decision-makers, the relevant decision-making behaviors fall under the category of “improper decision-making due to personal bias or emotions, individual self-interest, etc.” These improper decision-making behaviors are essentially human-caused errors resulting from organizational issues, such as disorder in CEG’s internal governance, internal control failures, and deficiencies in decision-making auditing. Furthermore, these improper decision-making behaviors remain hidden. This type of improper decision-making behavior is characterized by secrecy, expertise, broad impact, and substantial harm. These characteristics make the identification, prevention, and control of the risks associated with the improper behavior of financial decision-makers more complex and challenging.

Moreover, in the behavioral analysis of Adjustment Scenario 3 and Adjustment Scenario 5, this paper highlights the imbalance between organizational decision-makers’ self-assessment of competence and their expectations of benefits and utility. When organizational decision-makers hold the highest degree of decision-making authority, they exhibit a greater need for performance incentives and reward acquisition. When decision-makers hold the highest degree of decision-making authority, they are likely to have a greater desire for performance incentives and reward acquisition. This may lead them to misuse their authority by engaging in fraudulent practices, misappropriating funds, or leveraging their position to secure additional performance incentives and rewards.

Second, in the CEG saga, several executives exploited their positions and internal control loopholes to consistently make decisions that deviated from the organization’s goals and interests. This behavior objectively indicates significant issues in the group’s corporate governance, internal control management, decision-making, and auditing processes, behavior that aligns with Misconduct Risk Generation Condition 2: The organizational context is unable to impose effective constraints on decision-makers and their decision-making process (organizational error). The internal organizational cause of decision-making behavioral risk generation lies mainly in the fact that the executives’ identity in CEG was perceived as that of ‘a hand’. The authority of their positions provided significant freedom in adopting decision-making behaviors. This situation also led to the formation of a pattern of information asymmetry in the decision-making process and the assessment of asset principals. Consequently, other executives and stakeholders struggled to comprehend the logic and rationale behind their colleagues’ decision-making. They were hesitant to engage in the decision-making process and understand the underlying principles. These other executives and stakeholders found it difficult to understand the logic and rationale behind the decisions. However, they did not dare challenge or question them, leading to an imbalance of power and the formation of a ‘one-man dominance’ situation.

Finally, the absence of an effective internal oversight mechanism to balance the decision-making process, coupled with the lack of a robust decision-auditing mechanism to implement preauditing and continuous auditing of the decision-making process, results in blind spots in decision-making. These blind spots objectively enable departmental executives to make improper decisions and operate without transparency. This set of circumstances aligns with the assessment of Misconduct Risk Generation Condition 3: Lack of effective decision auditing and feedback mechanisms to control and intervene in decision-making programs that are significantly flawed or biased (organizational error) after they have been suggested. The organizational externalities of the CEG’s decision-making behaviors that create risks are primarily a result of inadequate processes, policies, and regulatory constraints, as well as insufficient penalties for the misconduct of financial decision-makers.

In summary, CEG is a representative case for researchers studying misconduct risk among financial decision-makers. In response to such misconduct risk among financial decision-makers, the following adjustments could be made and preventive measures taken.

First, financial institutions should optimize and adjust their performance incentive allocation and assessment orientation, improve corporate governance and cultivate a “people-oriented” organizational culture. Additionally, they should seek to decrease the conflict between \(R(a)\) organizational interests and personal interests, \(U(p,r,j)\) and effectively guide organizational decision-makers to actively improve their own abilities, reasonably adjust their own expected benefits on the basis of organizational interests, and enable the two types of interests to reach overall consensus at a controllable time.

Second, financial institutions should attach importance to and strengthen the construction \(\Delta {U}_{m}\) of organizational situations to fully leverage the “dual pressure” mechanism of internal control compliance and decision auditing, increase the cost of decision-makers choosing inappropriate behavior \(T(C)\), and reduce the incremental benefits of such behavior, thus ultimately controlling the motivation intensity of organizational decision-makers to choose inappropriate behavior.

Third, financial institutions should actively adjust their performance incentive and reward mechanisms (p), regulate decision-making rights (r), encourage fair job rank promotions (j), and dynamically balance the internal structure, equity ratios, and internal relationships of the three elements so that the organizational costs incurred can simultaneously increase the organizational interests of financial institutions and the interests of organizational decision-makers.

Conclusions and outlook

On the basis of this research, it can be concluded that the conduct risk of organizational decision-makers in financial institutions is a dual risk caused both by the organizational errors of the financial institutions and the human errors of decision-making behavior. The risk of organizational decision-makers in financial institutions has a dual nature: subjective and objective. The conflict between organizational interests and individual interests is the triggering condition for the occurrence of conduct risks among organizational decision-makers. Financial institutions should increase the behavioral costs of organizational decision-makers by reducing the level of organizational errors, thereby reducing the likelihood of conduct risks. When the evaluation of organizational decision-makers’ own abilities is out of balance with the benefits and utility provided by financial institutions, organizational decision-makers will often engage in inappropriate decision-making behaviors.

The value of this research consists in the following. First, we explored the connotations and generation mechanism of the misconduct risk of organizational decision-makers in financial institutions. We could deduce that such risk originates in the uncertainty of individual psychology, the knowledge experience, and skill factors of decision-makers, and organizational situational factors. When there is a conflict between the value orientations of financial institutions and organizational decision-makers, misconduct risk may occur. Second, the research constructed a risk analysis model for organizational decision-makers in financial institutions. The model included inappropriate decision-making behavior selection functions, choice motivation intensity functions, expected functions, and utility functions for decision-maker interests. The model was used to analyse the adjustment behavior of organizational decision-makers in different situations based on the balance and imbalance between their own ability evaluation and utility expectations.

The organizational decision-maker behavior risk analysis model constructed here mainly assesses the behavioral motivation, self-ability evaluation, and utility acquisition of organizational decision-makers, and the research object has singularity. In terms of function construction, future research could consider internal and external influencing factors that incorporate the organizational situation. In addition, the utility game relationship between financial institutions and organizational decision-makers could be considered to further explore the generation mechanism of misconduct risk in financial institutions, thus providing more accurate “targets” and “navigation” for the supervision and governance of misconduct risk.

Data availability

All data are availability.

References

Aebissa B, Dhillon G et al. (2023) The direct and indirect effect of organizational justice on employee intention to comply with information security policy: The case of Ethiopian banks. Comput Secur 130:103248

Arnott D, Gao SJ (2019) Behavioral economics for decision support systems researchers. Decis Support Syst 122:113063

Ashraf BN, Zheng CJ et al. (2016) Effects of national culture on bank risk-taking behavior. Res Int Bus Financ 37:309–326

Awrey D (2012) Complexity, innovation, and the regulation of modern financial markets. Harv. Bus. L. Rev 2:235

Aydemir R (2014) Empirical analysis of collusive behaviour in the Turkish deposits market. Econ Res Ekon Istraz 27(1):527–538

Candi M, Melia M et al. (2019) Two birds with one stone: the quest for addressing both business goals and social needs with innovation. J Bus Ethics 160:1019–1033

Carretta A, Farina V et al. (2017) Risk culture and banking supervision. J Financ Regul Compliance 25(2):209–226

Congjun R, Xinping X et al. (2007) Novel combinatorial algorithm for the problems of fuzzy grey multi-attribute group decision making. J Syst Eng Electron 18(4):774–780

Cooper M (2011) Complexity theory after the financial crisis: The death of neoliberalism or the triumph of Hayek? J Cult Econ 4(4):371–385

Cumming D, Dannhauser R et al. (2015) Financial market misconduct and agency conflicts: a synthesis and future directions. J Corp Financ 34:150–168

Curti F, Migueis M (2023) The information value of past losses in operational risk. J Operat Risk 18(2):1–36

Cusin J, Flacandji M (2022) How can organizational tolerance toward frontline employees errors help service recovery? J Personal Sell Sales Manag 42(2):91–106–106

Dhami, S., Al-Nowaihi, A., & Sunstein, C. R. (2019). Heuristics and public policy: Decision-making under bounded rationality. Studies in Microeconomics, 7(1), 7–58

DOO KY, Ha Y (2011) The influence of regulatory focus and the configuration of return-risk information on consumer choice of financial investment products. J Consum Stud 22(4):103–134

Fata AF, Martens CM (2017) The problem of the inside job: mitigating, detecting, and dealing with employee fraud. CBA Rec 31(1):26–31

Glavas A (2016) Corporate social responsibility and organizational psychology: an integrative review. Front Psychol 7:144

González-Torres T, Gelashvili V et al. (2023) Organizational culture and climate: new perspectives and challenges. Front Psychol 14:1267945

Goodman PS, Ramanujam R et al. (2011) Organizational errors: directions for future research. Res Organ Behav 31:151–176

Gottschalk R, Castro LB et al. (2022) Should National Development Banks be Subject to Basel III? Rev Political Econ 34(2):249–267

Grabowski M, Roberts KH (1996) Human and organizational error in large scale systems. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Part A Syst Hum 26(1):2–16

Kamran HW, Chaudhry N et al. (2016) Financial market development, bank risk with key indicators and their impact on financial performance: a study from Pakistan. Am J Ind Bus Manag 6(03):373

Lin M, Xie M, Li Z (2023) Organizational error tolerance and change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of public service motivation. Psychol Res Behav Manag 16:4133–4153

Mata PN, Mata MN et al. (2023) Does participative leadership promote employee innovative work behavior in IT Organizations. Int J Innov Technol Manag 20(05):2350027

McConnell P (2017) Behavioral risks at the systemic level. J Operat Risk 12(3):31–63

Nesvijevskai A, Ouillade G, Guilmin P, Zucker JD (2021) The accuracy versus interpretability trade-off in fraud detection model. Data Policy 3:e12

Nguyen DD, Hagendorff J et al. (2016) Can Bank Boards prevent misconduct? Rev Financ 20(1):1–36

Passant A, Laublet P et al. (2009) A uri is worth a thousand tags: from tagging to linked data with moat. Int J Semant Web Inf Syst 5(3):71–94

Qi P, Chiaro D et al. (2023) Model aggregation techniques in federated learning: a comprehensive survey. Future Generation Computer Systems 150:10–20

Ramanujam R, Goodman PS (2003) Latent errors and adverse organizational consequences: A conceptualization. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 24(7):815–836

Raven PV, McCullough JM, Tansuhaj PS (1994) Environmental influences and decision-making uncertainty in export channels: effects on satisfaction and performance. J Int Mark 2(3):37–59

Read GJ, Shorrock S, Walker GH, Salmon PM (2021) State of science: Evolving perspectives on ‘human error’. Ergon 64(9):1091–1114

Reason J (1995) A systems approach to organizational error. Ergon 38(8):1708–1721

Ruchlin HS, Dubbs NL, Callahan MA, Fosina MJ (2004) The role of leadership in instilling a culture of safety:lessons from the literature. J Healthc Manag 49(1):47

Shneor R, Munim ZH (2019) Reward crowdfunding contribution as planned behavior: an extended framework. J Bus Res 103:56–70

Sobanova J, Kudinska M (2023) The reasons for human errors in Banks and employees Mindsets. EMC Rev Econ Mark Commun Rev 26(2):362–378

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1991) Loss aversion in riskless choice: a reference-dependent model. Q J Econ 106(4):1039–1061

van Dyck C, Frese M et al.(2005) Organizational error management culture and its impact on performance: a two-study replication. J Appl Psychol 90(6):1228–1240

Walumbwa FO, Maidique MA, Atamanik C (2014) Decision-making in a crisis: What every leader needs to know. Organ Dyn 43(4):284–293

Yaari ME (1987) The dual theory of choice under risk. Econometrica: J Econom Soc 55(1):95–115

Yoshimura J, Ito H et al. (2013) Dynamic decision-making in uncertain environments II. Allais paradox in human behavior. J Ethol 31(2):107–113

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Social Science Foundation of China, ‘Research on Monitoring and Preventive Mechanisms of Digital Financial Risks under Multi-source Data Integration’ (Project No. 23BGL091). The authors thank the editors and reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft; TD: Data Curation, Resources, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing; MZ: Visualization, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, L., Dai, T. & Zhang, M. Generation mechanism of behavioral risk for organizational decision-makers in financial institutions: organizational and human errors. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1196 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03664-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03664-4