Abstract

The investigation of the relationship between pro-environmental behaviour and the determinants of natural environment sustainability is increasing; however, the heterogeneous effects of these determinants remain unclear. Based on large-scale original cross-sectional data (100,804 observations) from 37 countries, this study investigated the average and heterogeneous effects of socioeconomic, demographic, subjective, and psychological well-being characteristics on individuals’ pro-environmental behaviour using quantile regression. The results confirmed that, on average, a positive association existed between subjective well-being, knowledge of environmental issues, educational attainment, life satisfaction, mental health, positive emotions, and pro-environmental behaviour engagement. Importantly, heterogeneous effects were confirmed in the majority of determinants, including knowledge of environmental issues, education, number of children, life satisfaction, income, negative and positive emotions, and mental health. Given the heterogeneous effect of the determinants, the results suggest that overall better characteristics, including knowledge level, educational attainment, well-being, and family structure, are associated with better pro-environmental behaviour engagement among individuals, contributing to creating an eco-surplus society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among global natural environmental issues, such as global warming, climate change, and biodiversity loss, human activities are believed to be major contributing factors (Clayton et al., 2015; Lynas et al., 2021; Vlek and Steg, 2007; Swim et al., 2011; Wynes and Nicholas, 2017). For example, biodiversity loss is significant. According to a Living Planet report (WWF, 2022), the average wildlife population has declined by 69% since 1970. Therefore, pro-environmental behaviour that reshapes people’s activities to enhance environmental sustainability is recommended (Polasky et al., 2019). Pro-environmental behaviour reduces the natural environmental burden and mitigates climate change and biodiversity loss (Clayton et al., 2015; Dietz et al., 2009). This study contributes to sustainable development goals developed by the United Nations, referring to the 7th goal of affordable and clean energy, the 13th goal of climate action, the 14th goal of conservation of life below water, and the 15th goal of the protection of life on land (United Nations, 2015).

To better understand individuals’ decision-making regarding pro-environmental behaviours, scholars have developed theories for predicting them. The planned behaviour theory developed by Ajzen has already been utilized in empirical investigations on motivating pro-environmental behaviours, suggesting that behaviour is determined by attitudes, intentions, and subjective norms (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen and Albarracín, 2007; Arya and Kumar, 2023; Hansmann et al., 2020; Hasan et al., 2024; Wallance and Buil, 2023); Sociocognitive theory describes human behaviour through the triadic reciprocity of cognitive factors, personal factors, external environmental characteristics, and overt behaviours (Sawitri et al., 2015). Recently, the mindsponge theory has been found to be effective in investigating individuals’ comprehensive psychological, social, and behavioural phenomena (Jin and Wang, 2022; Vuong, 2023; Jin et al., 2023; Mantello et al., 2023; Vuong and Napier, 2015).

Indeed, the factors that influence people’s pro-environmental behaviours have been widely examined (Ghosh and Satya Prasad, 2024; Torgler and García-Valiñas, 2005; Akram et al., 2023; Aprile and Fiorillo, 2023; Barszcz et al., 2023; Chan et al., 2023; Chavan and Sharma, 2024; Cologna et al., 2022 etc.; do Canto et al., 2023; Du et al., 2024; Hogg et al., 2024; Kautish and Sharma, 2020; Razali et al., 2023; Torgler and García-Valiñas, 2005; Wang et al., 2023). Accordingly, research has determined that socioeconomic factors, demographic backgrounds, and psychological variables influence pro-environmental behaviour.

However, previous studies have mainly focused on the average effects of determinant factors on pro-environmental behaviour. The average effect is defined as the effect of the determinant factors derived from ordinary least squares, reflecting the relationship between the determinants and the conditional mean of pro-environmental behaviour. Quantile regression focuses on the heterogeneous effects of determinants on the different percentiles of pro-environmental behaviour, providing a comprehensive picture. The difference between the ordinary least squares (OLS) model and quantile regression is that the OLS model focuses on the effect of the determinants on the conditional mean of the dependent variables, whereas the quantile regression focuses on the effect on the conditional quantile of the dependent variables. The omission of illustrating the heterogeneous impact of the elements of pro-environmental behaviour might overestimate or underestimate the effects on specific groups when governments introduce policies to prompt people’s pro-environmental behaviour.

This study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, we aimed to present the heterogeneous effects of comprehensive socioeconomic, psychological, and demographic factors on pro-environmental behaviour using quantile regression, which can explore the effects of determinants on individuals’ pro-environmental behaviours. Second, compared with the average effect, the heterogeneous effect of each motivational element is discussed to identify the over- or under-evaluation of the impact of determinant factors on people’s pro-environmental behaviour. The objective of this discussion is to provide insightful evidence for policymakers to encourage citizens to engage in environmentally sustainable behaviour. Third, this study explored the heterogeneous effects and comprehensive factors of individuals’ pro-environmental behaviours in 37 nations, illustrating a deep international perspective.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a literature review. Section 3 describes the data, set of variables, and empirical strategy for estimating the heterogeneity effect of the factors determining pro-environmental behaviours. Sections 4 and 5 present the method and results, respectively. Section 6 presents the discussion.

Literature review

With the worsening of the natural environment, suggestions for improving environmental sustainability by reshaping people’s activities are necessary (Polasky et al., 2019). Pro-environmental behaviour and altruistic contributions to the natural environment reduce the burden on the natural environment burden and mitigate climate change and biodiversity loss (Clayton et al., 2015; Dietz et al., 2009).

Measurement of pro-environmental behaviour

Pro-environmental behaviour includes altruistic contributions to environmental conservation. In this scenario, changes to the natural environment are likely to lead towards sustainability (Lange and Dewitte, 2019; Li et al., 2019; Steg et al., 2014; Stern, 2000). Consistent terms are part of a sustainable lifestyle that defines a set of human behaviours associated with society, social norms, and institutional facilitation, which influence people’s decisions to minimize waste and use resources fairly (Akenji and Chen, 2016; Piao et al., 2020). Pro-environmental behaviours include recycling (Aizawa et al., 2008; Klöckner and Oppedal, 2011), environmentally friendly transportation usage (Li et al., 2019), waste management (Põldnurk, 2015), energy-saving behaviours (Li et al., 2019), green-goods purchasing (Eriksson et al., 2008; Kahn, 2007; Young et al., 2010), the purchasing of recycled water or goods (Byrne and O’Regan, 2014; Hansmann et al., 2006), and water or energy conservation (Lange and Dewitte, 2019; Li et al., 2019).

Comprehensive socioeconomic, demographic, and well-being determinants of pro-environmental behaviour

Scholars have developed theories to understand people’s involvement in pro-environmental behaviours. Planned behaviour theory, which predicts people’s behaviour using crucial determinants associated with pro-environmental behaviour, describes proxied determinant variables as behavioural intentions affected by people’s environmental conservation attitudes, consequences of behaviour, perceptions of environmental norms or conservation behaviours, and individuals’ perceived behaviours under their control (perceived behavioural control), which prompt environmentally friendly behaviours (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen and Albarracín, 2007; Arya and Kumar, 2023; Hasan et al., 2024; Wallance and Buil, 2023). Sociocognitive theory describes human behaviour through triadic reciprocity, cognitive factors, other personal factors, external environmental characteristics, and overt behaviours (Sawitri et al., 2015). Indeed, the factors that influence people’s pro-environmental behaviours have been widely examined (Torgler and García-Valiñas, 2005; Akram et al., 2023; Aprile and Fiorillo, 2023; Barszcz et al., 2023; do Canto et al., 2023; Du et al., 2024; Barr et al., 2011; Binder et al., 2020; Bülbül et al., 2023; Chawla and Cushing, 2007; Chwialkowska et al., 2020; Clark et al., 2003; De Groot and Steg, 2009; Essl et al., 2021; Hamann and Reese, 2020; Hynes and Wilson, 2016; Islam and Managi, 2019; Kahneman et al., 2004; Karp 1996; Kasser 2017; Kaur et al., 2021; Meyer 2015; Nordlund and Garvill, 2002; Oreg and Katz-Gerro, 2006; Osbaldiston and Schott, 2012; Pisano and Lubell, 2017; Raza et al., 2021; Saracevic and Schlegelmilch, 2021; Suárez-Varela et al., 2016; Zhang and Tu, 2021; Welsch et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021; Truelove and Gillis, 2018; Thøgersen 2009; Tam and Chan, 2017). The mindsponge theory assumes that individuals’ attitudes or behaviours are influenced by their mindset. The information affecting behaviour needs to enter the individual’s mindset or the core values need to pass the multi-filtering system, which is judged by the cost-benefit judgement or trust evaluation, while the system judges whether it accepts or rejects the information (Nguyen and Jones, 2022; Nguyen et al., 2023). In empirical practice, the Bayesian Mindsponge theory, which combines the mindsponge theory and statistical Bayesian methodology, has been applied (Ho et al., 2023; Nguyen et al., 2022; Vuong et al., 2022). To explore an individual’s natural environment-friendly attitudes or behaviour, studies have applied the mindsponge theory (Nguyen and Jones, 2022; Nguyen et al., 2023; Vuong, 2021; Vuong et al., 2023).

Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics and the well-being associated with pro-environmental behaviour have been widely examined. These socioeconomic and demographic factors include a knowledge of natural environment issues, educational attainment, gender, age, marriage status, family structure, economic condition (income, housing status), urban or rural area of residence, and health condition (Akram et al., 2023; Aprile and Fiorillo, 2023; Barszcz et al., 2023; Chan et al., 2023; Chavan and Sharma, 2024; Cologna et al., 2022; do Canto et al., 2023; Du et al., 2024; Hogg et al., 2024; Kautish and Sharma, 2020; Razali et al., 2023; Torgler and García-Valiñas, 2005; Wang et al., 2023)

Environmental knowledge favourably predicts high-impact pro-environmental behaviour (Carducci et al., 2021; Cologna et al., 2022; Ghosh and Satya Prasad, 2024; Kautish and Sharma, 2020; Razali et al., 2023). That is, well-educated people are likely to exhibit high levels of pro-environmental behaviour (Aprile and Fiorillo, 2023; López-Mosquera et al., 2015), or environmental education programmes have a favourable effect (Jaime et al., 2023). In addition, women are more likely than men to become involved in various types of pro-environmental behaviours (Torgler and García-Valiñas, 2005). As married couples are more concerned about future generations, they are more likely to become involved in activities that conserve the natural environment (Dupont, 2004; López-Mosquera et al., 2015). A positive relationship has been confirmed between environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behaviour (Carducci et al., 2021). Furthermore, household type has a positive impact on families’ pro-environmental behaviours, as more affluent households are more likely to be able to afford environmentally friendly products. From the perspective of an individual’s well-being, positive psychology or negative emotions are significantly associated with pro-environmental behaviour (Mavisakalyan et al., 2024). Hansmann et al. (2020) found that the effects of subjective well-being (i.e., feeling good) were positively correlated with pro-environmental behavioural activities. For a detailed description, refer to Li et al. (2019). Other factors include childhood experiences, a sense of self-control, personality, political or worldviews, goals, and a sense of responsibility (Gifford and Nilsson, 2014). Households in better-income classes reinforce pro-environmental behaviour (Aprile and Fiorillo, 2023; Du et al., 2024). Improvements in mental health and well-being are associated with better engagement in pro-environmental behaviour (Hogg et al., 2024).

However, investigations of the comprehensive heterogeneous relationships between the determinant factors are scarce. The differences between the average effects reflect the effect on the average outcomes, whereas the heterogeneous effect represents the effect on different levels of the outcomes. The average effect is described as the effect of the determinant factors on the conditional mean of the dependent variables, such as OLS regression. Therefore, the average effect focuses on the conditional mean of the outcomes, whereas the distribution of outcomes is missing. Quantile regression investigated the heterogeneous effect of the determinants on different percentiles of pro-environmental behaviour, providing a comprehensive picture. Suppose that the heterogeneous effects of various factors on people’s pro-environmental behaviour cannot be explained. In this case, the result may overestimate or underestimate the role of the determinants when the government issues policies to encourage people who are less likely to be involved in pro-environmental behaviour. Using original data from 37 countries, this study revealed the heterogeneous influence of various factors on individuals’ pro-environmental behaviour based on quantile regression analysis.

Aims of this study

This study aims to explore whether individuals’ determinants of pro-environmental behaviour have a heterogeneous effect that motivates pro-environmental behaviour based on an original survey of 37 nations, and how the heterogeneous effect of the determinants influences policymakers. This study followed the socioeconomic and demographic backgrounds adopted by previous studies that explored the determinants of pro-environmental behaviour, planned behaviour theory, and sociocognitive theory (Gifford and Nilsson, 2014; Hansmann et al., 2020; Lange and Dewitte, 2019; Li et al., 2019).

Figure 1 provides an overview of the determinant factors explaining pro-environmental behaviour in this study. Based on previous studies (Gifford and Nilsson, 2014; Hansmann et al., 2020; Lange and Dewitte, 2019; Li et al., 2019), the socioeconomic and demographic backgrounds adopted have been used to explore the determinants of pro-environmental behaviour, planned behaviour theory, and socio-cognitive theory. Factors influencing socioeconomic, demographic, and psychological variables were selected. The comprehensive characteristics that influence pro-environmental behaviour include socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, such as knowledge, educational attainment, household income, gender, marital status, family structure, occupational status, and housing status. Moreover, individuals’ comprehensive well-being includes life evaluation (life satisfaction), positive emotional well-being (pleasure, enjoyment, and happiness), negative emotional well-being (anger and sadness), and psychological well-being, including the ability to concentrate, sleeplessness, the usefulness of one’s role, decision-making, stress, overcoming difficulties, problem-solving, depression, confidence, and self-worth. Pro-environmental behaviour consists of an index of 14 multidimensional activities involving environmental conservation through energy-consumption-friendly behaviours, the waste cycle, and environmental protection.

Comparisons of the average and heterogeneous effects are discussed to present the potential for the underestimation or overestimation of the impact of these factors. This study provides insightful evidence in this field. This study aims to explore whether individuals’ determinants of pro-environmental behaviour have a heterogeneous effect that motivates pro-environmental behaviour based on an original survey of 37 nations, and how the heterogeneous effect of the determinants influences policymakers.

Data

The heterogeneous impacts of the characteristics influencing people’s behaviour toward environmental conservation purposes were illustrated using an original survey of 37 nations. This cross-sectional survey was conducted through a third-party company (Nikkei Research) from 2015 to 2017 using Internet and face-to-face surveys. Regionally and culturally representative nations were selected to illustrate international perspectives on this environmental issue. To ensure that the collected sample represented the population’s characteristics, a random sampling method was adopted to select the targeted respondents in each country to match each nation’s population distribution with respect to age and gender. The original survey was conducted through the Internet reregister panels of a third-party company. However, it is well known that there are few older female Internet users, indicating that the collected sample may have potential selection bias. To address this potential issue, we selected the closest age groups among female Internet users. More precisely, in the first step, we divided the population into subgroups in terms of age and gender, referring to the overall characteristics of the population, and the targeted sub-sample size was determined to match the population’s age and gender characteristics and random sampling was used for each group. Furthermore, Internet users tend to be better educated and have higher incomes, which may lead to sample selection issues. Face-to-face surveys were conducted in Egypt, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, India, and Malaysia. The list of countries that conducted Internet and face-to-face surveys is displayed in Table 1. Internet surveys were conducted in 32 countries, as they allow a random sampling process to match the population characteristics, whereas face-to-face surveys were conducted in nations where there are few Internet users. Both Internet and face-to-face surveys were conducted in some developing nations, including Indonesia, India, and Malaysia, as face-to-face surveys allow the involvement of non-Internet users considering their pro-environmental behaviour and socio-economic background. This study used both internet survey and face-to-face surveys to collect the data from targeted countries. The internet surveys provide a dataset using a random sampling method that has broad and diverse characteristics, and the face-to-face surveys target non-internet users. Therefore, the dataset applied two sample collection methods to offer a comprehensive understanding of the pro-environmental behaviour across different socioeconomic, demographic, and well-being backgrounds.

After preparing the questionnaire, it was translated by professionals through multiple checks in each country, after which the author proceeded carefully to enhance its accuracy. The survey was defined according to previous studies, such as a mental health survey based on the 12 items of the generalized health questionnaire (Lundin et al., 2016; Zulkefly and Baharudin, 2010). The adoption of the questionnaire in different cultural backgrounds was facilitated by the fact that the professionals had different cultural research backgrounds. For professional translation to different languages, the designed questionnaire was sent to a third-party company that provides professional translation services with multiple checks. The original survey collected respondents’ well-being, attitudes toward pro-environmental behaviour, and demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. A total of 100,956 valid observations were collected from 6 continents and 37 nations. The number of observations for each country ranged from 500 to 20,744. After deleting observations with missing values from the information of interest, 100,804 observations were used in the analysis to examine the relationship between pro-environmental behaviour and well-being.

The study design was approved by the appropriate legal and ethics review board of Kyushu University for the original cross-sectional internet survey conducted by a third-party company between 2015 and 2017. Data were collected with informed consent from the participants according to legal and ethical guidelines. All methods were performed in accordance with ethical guidelines and were approved by the ethics committee of Kyushu University.

Variable setting

Multi-dimensional pro-environmental behaviour

This study aims to estimate the average and heterogeneous effects of determinants on an individual’s involvement in pro-environmental behaviour. The dependent variable, multidimensional pro-environmental behaviour, is a scaled variable used to measure people’s activities regarding environmental conservation. To measure people’s pro-environmental behaviour, referring to Lange and Dewitte (2019), the self-report measurement method was adopted. Respondents were asked, “Please select all actions that you have taken these days.” To avoid people’s measurement bias, a binary choice was adopted if individuals were involved in a pro-environmental behaviour, with the specific type equal to 1 and, otherwise, equal to 0. Regarding the choice of people’s involvement in pro-environmental behaviour, following the literature (Lange and Dewitte, 2019; Li et al., 2019), the pro-environmental behaviour included (1) recycling or sorting rubbish/reducing rubbish; (2) cleaning or gathering rubbish in your neighbourhood; (3) energy-saving actions (saving electricity, fuel, etc.); (4) the use of public transportation or (8) bicycles; (5) purchasing recycled goods; (6) purchasing energy-saving household products; (7) environmental actions organized by the government; (8) environmental actions organized by corporations; (9) environmental actions organized by international groups; (10) environmental education; (11) animal protection; (12) protection of forests (afforestation, regulation of illegal deforestation, etc.); (13) activities related to environmental policy; and (14) meetings or demonstration on environmental issues. The unweighted summation of people’s involvement in the above activities constructed the people’s index of multi-dimensional behaviour. A greater number indicates more frequent involvement in different types of pro-environmental behaviour. We acknowledge that there may still be measurement bias due to individuals’ different standards in understanding pro-environmental behaviour items.

Cronbach’s alpha has been widely adopted by previous studies to test reliability, and it can be used to measure the similarity among numerous types of measurement to the same pro-environmental behaviour category. The scale reliability of Cronbach’s α was 0.750 for the number of items above 14 on the scale. The result of Cronbach’s α for pro-environmental behaviour is within the scale’s reliability (Piao and Managi, 2022; Zakaria and Yusoff, 2009). Cronbach’s alpha was used to measure the similarity within the variables belonging to the same category, for example, psychological distress. When the reliability of Cronbach’s α is within the scale, the summation of the variables to a new representative variable is reliable (e.g., Piao and Managi, 2022; Zakaria and Yusoff, 2009).

Subjective well-being as well as psychological and socioeconomic factors

The determinants of pro-environmental behaviour, the independent variables, are people’s socioeconomic background, demographic background, and subjective and psychological well-being characteristics (Gifford and Nilsson, 2014; Hansmann et al., 2020). See Gifford and Nilsson (2014) for a review of the preceding literature. Socioeconomic and demographic factors have been confirmed to influence people’s involvement in pro-environmental behaviour. The determinant factors include age, gender (a dummy variable for which women equal one and others are valued as zero), household income, marriage status (dummy = 1 if married, otherwise = 0), number of children, number of cohabitating families, individual’s educational attainment, employment (unemployment; other; housewife/househusband; student; self-employed employee; professional; government employee; company owner; full-time employee; part-time employee), and home status (renter). Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics. An individual’s knowledge of environmental issues reflects 10 aspects, including global warming, air pollution, loss of biodiversity, sustainability of the energy supply, water pollution, forest protection, and environmental pollution/protection of nearby nature (sea, mountain, river, lake, etc.). The values for each aspect are set the same, with very knowledgeable = 5, moderately knowledgeable = 4, average knowledge = 3, less knowledgeable = 2, and not at all knowledgeable = 1. Individuals’ knowledge level of environmental issues is the unweighted average of the 10 aspects above, ranging between 1 and 5. The greater number presents subjects as knowledgeable about environmental issues.

For the characteristics of subjective and psychological well-being, people’s life-evaluated satisfaction, emotional well-being, and psychological well-being were adopted based on previous studies (Hansmann et al., 2020; Helliwell and Aknin, 2018; Durand and Smith, 2013; Clark et al., 2019; Kahneman and Deaton, 2010). People’s subjective well-being is generally divided into life evaluation and emotional well-being (Kahneman and Deaton, 2010). According to OCED guidelines, the Contril ladder is encouraged to measure people’s life satisfaction. In the questionnaire, the respondents are required to answer, “Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from 0–10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you, and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?”

For emotional well-being, individuals were asked how often they experienced pleasure, anger, sadness, enjoyment, and smiles within a week. The choice was often = 4, sometimes = 3, rarely = 2, and not at all = 1.

Regarding people’s psychological well-being, a 12-item general health questionnaire was adopted. The 12 items included the ability to concentrate, sleeplessness, useful role, decision making, stress, overcoming difficulties, problem solving, depression, confidence, and worth. The detailed questions in the questionnaire are as follows:

Please select the one that is the most applicable. Have you recently … ?

①been able to concentrate on whatever you are doing?

②lost much sleep over worry?

③felt that you were playing a useful role in things?

④felt capable of making decisions about things?

⑤felt constantly under strain?

⑥felt that you could not overcome your difficulties?

⑦been able to enjoy your normal day-to-day activities?

⑧been able to face up to your problems?

⑨been feeling unhappy and depressed?

⑩been losing confidence in yourself?

⑪been thinking of yourself as a worthless person?

⑫been feeling reasonably happy, all things considered?

The choices for each question were valued as follows: more so than usual = 4, same as usual = 3, less so than usual = 2, and much less than usual = 1.

Country dummies were controlled to capture country-specific heterogeneity.

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the empirical analysis with a sample mean or percentage, standard deviation, min value, and max value. The accumulated distribution of people’s involvement in pro-environmental behaviour among 37 nations. On average, people involved in about four types of pro-environmental behaviour show a large area for potential improvement. The multidimensional pro-environmental behaviour of the people ranged between 0 and 14, presenting a greater value, indicating the more varied individuals involved in the pro-environmental behaviour. In the sample, the median (0.5 quantile or 50% percentile) is the individual involved in three kinds of pro-environmental behaviour. Overall, the accumulated distribution of people’s pro-environmental behaviour reveals that most people participated in several types of pro-environmental behaviour, suggesting potential improvement.

In the sample, the mean age was 42.7 years. About 65.7% of the individuals were married, and 49.7% of the respondents were women. The families, on average, have 1.2 children, and the number of cohabitating family members is 3.3. For an individual’s years of education, the average individual recorded 14.25 years of education. Around 70% of people own a house, and 23.8% rent a house as their residence. Occupational status varied, with 43.5% of the people employed full time. Regarding subjective and psychological well-being characteristics, the mean value of life satisfaction was 6.65, presenting a positive evaluation of their lives, as the evaluation ranged between 0 and 10. Consistently, on average, people demonstrated positive emotions and psychological well-being.

Methodology

This study examined the comprehensive effects of socioeconomic and demographic factors and subjective and psychological well-being determinants of pro-environmental behaviour using linear and quantile regression based on a large-scale original cross-sectional survey derived from 37 countries (see Fig. 2). Comprehensive effects include the average effect of the determinants on an individual’s pro-environmental behaviour, as measured using linear regression (Eq. 1). The heterogeneous effects of the determinants were estimated using quantile regression (Eq. 2). According to Gifford and Nilsson (2014) and Hansmann et al. (2020), the determinants of pro-environmental behaviour include socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, such as knowledge, educational attainment, household income, female dummy, marriage, number of children, occupation, and housing status. The subjective and psychological well-being factors include individuals’ psychological characteristics of life satisfaction, pleasure, anger, sadness, enjoyment, happiness, ability to concentrate, sleeplessness, useful role, decision-making, stress, overcoming difficulties, problem-solving, depression, confidence, and self-worth.

where \({Y}_{{iC}}\) is the pro-environmental behaviour of individual \({i}\) in country \(C\), \({X}_{{iC}}\) is the determinant of pro-environmental behaviour resulting from an individual’s socioeconomic and demographic background, and \({Y}_{{iC}}\) is a set of covariates of the individual’s subjective and psychological well-being characteristics that influence people’s involvement in environmental conservation. \({D}_{C}\) denotes country dummies used to control for country-specific heterogeneity. \({\beta }_{0}\), \({\beta }_{1},\) \({\beta }_{2}\), and \({\beta }_{3}\) are estimated parameters presenting the average effect of the determinants of pro-environmental behaviour, and \({\varepsilon }_{{iC}}\) is the error term.

When human activities are believed to be major contributors to environmental issues, such as climate change, the examination of prompt pro-environmental behaviour is crucial and provides a way to reshape people’s activities towards sustainability. The determinants of pro-environmental behaviour by different groups of people identify whether the effects of the determinants are heterogeneous. Quantile regression is appropriate to identify the heterogeneous effects of independent variables (Akram et al., 2021; Wooldridge 2010; Greene 2012).

where \({Y}_{{iC}}\) is individual \(i\)’s pro-environmental behaviour in country \(C\); \({X}_{{iC}}\) is a set of covariates reflecting an individual’s socioeconomic and demographic background, which influence their involvement in environmental conservation. Moreover, \({e}_{{iC}}\) is the error term and \({D}_{C}\) denotes the country dummies used to control for country-specific heterogeneity. Moreover, \({\alpha }_{0q}\), \({\alpha }_{1q}\), \({\alpha }_{2q}\), and \({\alpha }_{3q}\) are the estimated parameters or qth quantile, indicating the heterogeneous effect of the determinants of pro-environmental behaviour.

Quantile regression investigates the association between the determinants and conditional quantiles of individuals’ involvement in pro-environmental behaviour. The quantile represents the distribution of the key dependent variable, pro-environmental behaviour, and the quantile is the percentile of pro-environmental behaviour such that the 0.75 quantile represents the 75th percentile. As a robustness check, a logit quantile regression was applied and consistent results were obtained.

Results

Table 3 presents the results derived from quantile regression using original surveys collected from 37 nations, based on Eq. (2). The dependent variable is people’s multi-dimensional pro-environmental behaviour, ranging between 0 and 14, with a greater value indicating people involved in multi-dimensional pro-environmental activities. Columns 1 to 4 display the results of the regression at the 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 quantiles of the pro-environmental behaviour.

The results are summarized as follows. People’s knowledge level of environmental issues had a favourable effect on people involved in environmental conservation activities. Moreover, the results suggest that the effects of people’s knowledge of environmental issues have a heterogeneous effect on people’s behaviour, which contributes to environmental conservation. The coefficients of an individual’s knowledge are 0.421 at 0.1 quantiles, whereas the corresponding coefficients are 0.617, 0.793, and 1.009 of a regression of the 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 quantiles and are statistically significant at 1%. The magnitude of the coefficient is smaller in the lower quantile, indicating a weak effect on the individuals at the lower quantile than on the knowledge level at the higher quantile. Individuals at the lower quantile are unlikely to be involved in multiple activities that contribute to environmental conservation and sustainability. Based on the average effect of knowledge on pro-environmental behaviour to prompt human behaviour, it might overestimate the effect on people who lack pro-environmental involvement.

Similarly, the favourable effect was confirmed regarding educational attainment’s effect on people’s contribution to protecting the natural environment. The in-depth analysis presents a heterogeneous effect on people’s involvement in multidimensional pro-environmental behaviour. Consistent with people’s knowledge, the improvement effect of education attainment on pro-environmental behaviour is weaker at the 0.1 quantile, whereas it is greater in the 0.5 or 0.75 quantiles. The results suggest that the favourable effect of education might be weaker for people in the lower quantile, which indicates that people are less likely to be involved in pro-environmental behaviour.

Against a knowledge of environmental issues and educational attainment, household income decreases individuals’ involvement in pro-environment behaviour. The coefficients of ln (household income) are negative and statistically significant at the 0.1, 0.25, and 0.5 quantiles and insignificant at the 0.75 quantile. This suggests that household income is negatively associated with households’ involvement in people’s multi-dimensional pro-environmental behaviour. Moreover, a greater negative effect was found in the lower quantile than in the higher quantile. Conversely, having one’s own house improves individuals’ behaviour.

The family structure appears to have a heterogeneous effect on households’ behaviour for the purposes of environmental conservation. The respondents’ marriage status, with the number of children, was positive and statistically significant at 1%. The greatest effect of marriage status was observed at the 0.25 quantile, whereas the greatest effect of children appeared at the 0.75 quantile.

Employment status has a statistically significant heterogeneous effect on people’s involvement in pro-environment behaviour. We found that professional employees are likelier to participate in multi-dimensional pro-environmental behaviour compared to the unemployed. The participating attitudes regarding the professional employee are strengthened at a higher quantile. Conversely, the coefficients of full-time employees, company owners, and government employees are negative values and statistically significant. The results indicate that being employed is negatively associated with individuals’ involvement in pro-environmental behaviour.

In summary, socioeconomic and demographic factors have a heterogeneous effect on the people involved in multi-dimensional pro-environmental behaviour. For people’s knowledge of environmental issues and educational attainment, the effects are weak in the lower quantile, which indicates that the effect is weak for people who are unlikely to attend multi-dimensional environmental conservation activities. Similarly, household income negatively correlates with multidimensional pro-environment behaviour and a stronger negative relationship at the lower quantile. Moreover, the heterogeneous effect of family structure and employment status was confirmed. The consistent relationship between the socio and demographic characters and the people’s involvement in pro-environmental behaviour is confirmed using quantile regression in 21 country analyses and 37 country analyses. We conducted the results in representative countries and found the consistent results that the individuals’ knowledge, and education are crucial for individuals involved in pro-environmental behaviour across countries, including China, the USA, and Japan. The opposite effect of household income on pro-environmental behaviour in high-income countries (United States) and non-high-income countries (China) is found.

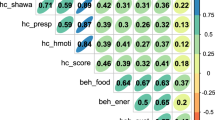

Table 4 illustrates the relationship between individuals’ subjective well-being and psychological well-being on individuals’ pro-environmental behaviour using quantile regression based on Eq. (2) to estimate the heterogeneous effect of the factors influencing pro-environmental behaviour. Columns 1, 2, and 3 display the quantile regression results at the 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 quantiles of pro-environmental behaviour, respectively. Multi-dimensional pro-environmental behaviour is a scaled variable ranging from 0 to 14, which measures people’s activities to conserve the environment.

The heterogeneous effects of individuals’ subjective well-being and psychological well-being on people’s pro-environmental behaviour were found based on the quantile regression. The coefficients of life satisfaction are positive values in the 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 quantiles, suggesting a positive association between life satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour. A higher evaluation of their overall lives might correlate with higher involvement in activities to conserve the environment. However, the coefficients differ for different quantiles; the coefficients are 0.009, 0.017, and 0.039 for the 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 quantiles, respectively. The coefficients are greater at higher quantile levels. The results indicate that the effects of satisfaction with one’s life are greater in people involved in multi-dimensional activities for the environment, and an increase in individuals’ life satisfaction displays a greater effect on people involved in more types of pro-environmental behaviour to conserve the environment.

A positive relationship between emotional well-being and people’s pro-environmental behaviour is concluded; moreover, the heterogeneous effect of positive emotion (pleasure, enjoyment, and smile) on individuals’ pro-environmental behaviour involvement. The coefficients of pleasure are 0.06, 0.079, and 0.109 at 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 quantiles, respectively. Similarly, the coefficients of enjoyment are greater at higher quantiles than at lower quantiles. This suggests that the greater positive effects of experiences of pleasure or enjoyment are recorded in people’s involvement in pro-environmental behaviour.

A mixed relationship was confirmed between negative emotional experiences and individuals’ environmental conservation behaviours. For example, the coefficients of anger were negative and statistically significant. This indicates a negative association between altruistic environmental conservation and anger. On the contrary, the coefficient of sadness is negative at the 0.25 quantile, whereas its coefficient is positive at the 0.75 quantile. The heterogeneous effect of sadness was confirmed according to different quantile levels.

The association between people’s psychological well-being and people’s involvement in pro-environmental activities is also illustrated. Individuals’ psychological well-being measurement adopted a general health questionnaire, including concentration ability, sleep quality, etc. There was a positive relationship between better psychological well-being and people’s involvement in pro-environmental behaviour. The coefficients of ability to concentrate, a useful role, decision-making ability, problem solving, confidence, and the experience of worth are positive values, from the 0.25 to the 0.75 quantiles. The results suggest that better mental health prompts people’s behaviour toward sustainability, which is consistent with prior results. Similarly, the negative relationship between poor mental health and people’s environmental conservation behaviour is confirmed. The coefficients of sleeplessness, higher stress, difficulties in overcoming problems, and depressing experiences are negative values and statistically significant. This confirms that poor mental health decreases people’s environmentally friendly behaviour.

Moreover, we found a heterogeneous effect of people’s mental health on their activities for environmental purposes. The magnitudes of coefficients for the ability to concentrate, sleeplessness, usefulness of one’s role, decision making, overcoming difficulties, problem solving, confidence, and worth are greater at the 0.75 quantile compared to the coefficients at the 0.25 quantile. The results suggest that there are heterogeneous effects of individuals’ pro-environmental behaviour, and the effect is smaller at the lower quantile and greater at the higher quantile. Meanwhile, ignoring the heterogeneous effects of these factors might overestimate the impact of the determinant factors on people’s involvement in pro-environment behaviour.

In contrast, the magnitude of the coefficients for stress and depression was greater at the lower quantile than at the higher quantile. This indicates the heterogeneous effects of stress and depression on individuals’ activities to protect the environment. The effects appear greater in a people group at a lower quantile than at a higher quantile.

Figures 3–8 illustrate the heterogeneous and average effects of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics on individuals’ involvement in pro-environment behaviour. The heterogeneous effect of the interesting independent variables (e.g., knowledge) was estimated by quantile regression, whereas the average effect of the independent variables was derived from the ordinary least squares (OLS) model. The long dashed line denotes the magnitudes of the estimator derived from the OLS regression. The line denotes the effects of independents at each quantile, and the grey area denotes the 95% confidence interval derived from the quantile regression.

The long dashed line denotes the magnitudes of the estimator derived from the OLS regression (Eq. 1). The line denotes the effects of independents at each quantile, and the grey area denotes the 95% confidence interval derived from quantile regression. Data sources: Original survey of 37 nations.

The long dashed line denotes the magnitudes of the estimator derived from the OLS regression (Eq. 1). The line denotes the effects of independents at each quantile, and the grey area denotes the 95% confidence interval derived from the quantile regression. Data source: Original survey of 37 nations.

The long dashed line denotes the magnitudes of the estimator derived from the OLS regression (Eq. 1). The line denotes the effects of independents at each quantile, and the grey area denotes the 95% confidence interval derived from quantile regression. Data source: Original survey of 37 nations.

The long dashed line denotes the magnitudes of the estimator derived from the OLS regression (Eq. 1). The line denotes the effects of independents at each quantile, and the grey area denotes the 95% confidence interval derived from quantile regression. Data source: Original survey of 37 nations.

The long dashed line denotes the magnitudes of the estimator derived from the OLS regression (Eq. 1). The line denotes the effects of independents at each quantile; the grey area denotes the 95% confidence interval derived from quantile regression. Data source: Original survey of 37 nations.

Heterogeneous effects were found regarding individuals’ well-being characteristics and their involvement in pro-environmental behaviour. Overall, regarding the effects of individuals’ knowledge of natural environmental issues, they are likely to appear to have a statistically significant difference between the heterogeneous effect and the average effect. For example, the coefficients of life satisfaction are statistically significantly different at the lower quantile compared to the results derived from the OLS measuring the average of life satisfaction on pro-environment behaviour; on the contrary, the heterogeneity effect is greater in the higher quantile. The results suggest that the effect of an individual’s subjective well-being is weaker when people participate in less pro-environmental behaviour. In contrast, the effect heightens for people participating in various pro-environmental behaviours. To prompt people’s pro-environmental behaviour, the heterogeneous effect should be considered for estimation and application to the policy.

The different types of heterogeneous effects of the factors influencing people’s pro-environmental behaviours can be summarized into three categories, as follows:

(1) Overall quantile. A statistically significant difference was observed between the heterogeneous and average effects. The heterogeneous effect is derived from quantile regression, and the average effect is derived from OLS regression. For an individual’s knowledge level regarding environmental issues, household income, and the female dummy, compared to the average effect, there was a significant heterogeneous effect of the corresponding individual’s pro-environment influential factor on people’s pro-environmental behaviour on the overall quantiles.

(2) At the lower quantile, there is a statistically significant difference between the heterogeneous effect and the average effect. At a lower quantile, the coefficients of educational attainment, marriage status, and number of children derived from quantile regression were found to be significantly less (educational attainment, number of children) or more (marriage) than the average effect. This indicates that the average effect might overestimate the effect of educational attainment and the number of children for the group who are less likely to be involved in multi-dimensional pro-environmental behaviour. (3) At a higher quantile, the statistically significant difference between the heterogeneous effects of factors is derived from quantile regression and average effect estimates from OLS regression. For the effect of people’s occupational status (full-time employees), the evaluation based on the average effect might underestimate occupational status on environmental conservation behaviour.

Combining Figs. 3 to 8, according to the heterogenous effect of the determinants, four types of determinants that improve pro-environmental behaviour can be summarized. First, the heterogeneous effects of the following factors are statistically significantly different from the average effects for people’s life satisfaction, sadness, enjoyment, ability to concentrate, useful role, decision making, problem solving, knowledge of natural environment issues, and number of children. The effects of these determinants are weaker than the average effect in the lower quantile, while the magnitude of the effects is greater in the higher quantile. This suggests that the determinants are weaker than the expectations estimated using the average effect. Because the effect of the determinants of pro-environment behaviour differs according to the people group, the interpretation based on the average effect must be improved. The heterogeneous effect should be accounted for if the policy targets the people group less likely to conserve the natural environment.

Second, at the lower quantile, the coefficients of pleasure, anger, smile, and educational attainment were statistically significantly different from the average effect of the corresponding variables on people’s pro-environmental behaviour. Overall, the effects of the determinants between the middle and higher quantiles were statistically insignificant compared to the average effect derived from the OLS. The results show that the difference between the heterogeneous effect of the determinants and the average effect is limited, conveying that the average effect of pleasure, anger, and smile might be moderate, according to evidence based on the average effect. Third, we found that the effects of depression, confidence, and home status on individuals’ pro-environmental behaviour were not significantly different from those of the OLS estimator. The results indicated that the effects of depression, confidence, and home status on pro-environmental behaviour were stable across different types of environmental conservation groups. In this case, the evidence derived from the OLS estimator was representative of the policy introduced to improve the population’s attitudes toward environment conservation. This may be because people’s psychological or home status consistently influences their activities. Finally, the heterogeneous effect of the difficulties of overcoming issues, sleeplessness, and worth on people’s involvement in pro-environmental behaviour was confirmed with the higher effect on the lower quantile and the weaker effect on the higher quantile. If policymakers aim to improve the natural environmental behaviour of citizens who are less likely to participate, the evaluation of the determinants from the average effect may underestimate their effects.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the heterogeneous effects of individuals’ socioeconomic, demographic, subjective, and psychological well-being characteristics on pro-environmental behaviour using a quantile regression model with an original survey of 37 countries. This study refers to planned behaviour, psychological, and mindsponge theories in the empirical analysis of pro-environmental behaviour and the determinant characteristics of socioeconomic, demographic, and well-being adopted in previous studies. To understand the comprehensive relationship between the determinants and involvement in pro-environmental behaviour, aside from the average effect of the determinants on which previous studies have focused (Gifford and Nilsson, 2014; Hansmann et al., 2020), exploring the heterogeneous effects of pro-environmental behaviour may provide insightful evidence for understanding pro-environmental behaviour engagement.

Socioeconomic, demographic, and well-being determinants of pro-environmental behaviour—average effect

Previous studies have examined the relationship between people’s socioeconomic, demographic, and well-being characteristics and their involvement in pro-environmental behaviour (Carducci et al., 2021; Ghosh and Satya Prasad, 2024; Kautish and Sharma, 2020; Mavisakalyan et al., 2024; Razali et al., 2023; Torgler and García-Valiñas, 2005).

A positive association has been confirmed between individuals’ subjective well-being and their involvement in pro-environmental behaviours. The favourable effects were knowledge of environmental issues, educational attainment, female dummy, marital status, number of children, housing status, life satisfaction, pleasure, sadness, enjoyment, smiles, the ability to concentrate, having a useful role, decision-making, problem-solving, confidence, and self-worth. These results corroborate those of previous studies (Carducci et al., 2021; Ghosh and Satya Prasad, 2024; Kautish and Sharma, 2020; Mavisakalyan et al., 2024; Razali et al., 2023; Torgler and García-Valiñas, 2005; Akram et al., 2023; Aprile and Fiorillo, 2023; Barszcz et al., 2023; Chan et al., 2023; Chavan and Sharma, 2024; Cologna et al., 2022 etc.; do Canto et al., 2023; Du et al., 2024; Hogg et al., 2024; Kautish and Sharma, 2020; Razali et al., 2023; Torgler and García-Valiñas, 2005; Wang et al., 2023). However, a negative association was found between environmental conservation behaviours and household income, which is inconsistent with the results of previous studies (Aprile and Fiorillo, 2023; Du et al., 2024). The negative association between anger, sleeplessness, stress, overcoming difficulties, depression, and pro-environmental behaviour engagement is consistent with the findings of Hogg et al. (2024).

We found that individuals with a better socioeconomic status, complicated family structures, subjective well-being, and psychological well-being positively associated with their participation in natural environmental conservation. These results were consistent with those of previous studies (Dupont, 2004; Hansmann et al., 2020; López-Mosquera et al., 2015; Torgler and García-Valiñas, 2005). People with better education appear to display more involvement in pro-environmental behaviours (López-Mosquera et al., 2015). Female individuals exhibit more cooperative behaviour regarding environmental protection (Torgler and García-Valiñas, 2005). In addition, married individuals exhibit more attention to pro-environmental behaviour, as they are concerned about future generations’ well-being (Dupont, 2004; López-Mosquera et al., 2015). Hansmann et al. (2020) found that subjective well-being is positively correlated with an individual’s pro-environmental behaviour. However, a negative relationship was confirmed between household income, full-time employment, and involvement in pro-environmental behaviour. This result is inconsistent with those of previous studies, perhaps because of citizens’ time constraints regarding their participation in pro-environmental activities when displaying higher economic productivity. López-Mosquera et al. (2015) and Fan et al. (2013) found a positive influence of household income on pro-environmental behaviour owing to the demand for environmentally friendly consumption products. Similarly, wealthy individuals tend to donate their wealth for the conservation of the natural environment.

The population involved in qualified pro-environmental behaviours is crucial because they are associated with the outcomes of an eco-surplus culture. Ecosurplus culture creation refers to the implementation of ecosurplus initiatives to relieve environmental degradation, alleviate climate change, and prevent biodiversity loss. These favourable outcomes lead society toward sustainability of the natural environment. When the natural environment changes rapidly, reshaping people’s activities toward environmental sustainability has attracted increasing attention (Wynes and Nicholas, 2017).

Socioeconomic, demographic, and well-being determinants of pro-environmental behaviour—heterogenous effect

Four types of effect were confirmed regarding the heterogeneous effects of socioeconomic, demographic, and well-being factors on individuals’ pro-environmental behaviour compared with the average effect. This indicates that the effects of the determinants differed according to people’s pro-environmental behaviours. The results suggest that, based on the average effect of the comprehensive characteristics of individuals’ involvement, they may have over- or under-evaluated the effect of the characteristics of environmental conservation behaviour.

First, there is an overall heterogeneous effect across quantiles, with heterogeneous effects at the lower and higher quantiles, and an insignificant heterogeneous effect across quantiles. Concerning the overall heterogeneous effect compared with the average effect, the individual’s knowledge level regarding environmental issues, household income, female dummy, life satisfaction, sadness, enjoyment, ability to concentrate, sleeplessness, having a useful role, decision-making, difficulties in overcoming issues, problem-solving, and self-worth, the heterogeneous effects of these factors were statistically significantly different from the average effects (Ghosh and Satya Prasad, 2024; Mavisakalyan et al., 2024; Razali et al., 2023). The results indicate that the determinant effects were weak when people participated in less pro-environmental behaviour.

Second, at a higher quantile, there was a statistically significant difference between the heterogeneous effect of the factors derived from the quantile regression and the average effect estimates from the OLS regression (full-time employment). Third, at a lower quantile, statistically significant differences between the heterogeneous and average effects were observed for the effects of pleasure, anger, happiness, educational attainment, marital status, and number of children on people’s pro-environmental behaviour. The results are different with previous studies when the quantile regression methods are applied (Aprile and Fiorillo, 2023; Du et al., 2024; Hogg et al., 2024). Finally, we found that the effect of depression on individuals’ pro-environmental behaviour was not significantly different from that of the OLS estimator (Du et al., 2024). This suggests that an individual’s depression can be evaluated based on the average effect.

The policy implications were summarized based on the estimation results. First, this study found that the effects varied between the contextual and individual levels; more precisely, the effects of knowledge level regarding environmental issues, life satisfaction, sadness, enjoyment, ability to concentrate, having a helpful role, decision-making, problem-solving, pleasure, happiness, educational attainment, and number of children were weak in individuals involved in a lower level of pro-environmental behaviour. These results suggest that policymakers should consider the heterogeneous effects of the determinants and estimate the effects more accurately through quantitative evaluation. A comprehensive, higher level of well-being and knowledge may be associated with a population’s contribution to natural environmental conservation. In contrast, the improvement in household income is more likely to affect the lower-level pro-environmental behaviour of individuals, changing their behaviour towards sustainability. In this case, economic development is crucial for policymakers to enhance the economic well-being of the population.

Second, better subjective well-being is associated with favourable citizens’ cooperative behaviour to protect the natural environment (Aprile and Fiorillo, 2023; Du et al., 2024; Hogg et al., 2024). However, this effect varies according to the level of pro-environmental behaviour. The effects appear weak when individuals are involved in fewer pro-environmental behaviours. This indicates that improving people’s overall well-being is crucial, with favourable consequences for natural protection. Moreover, the effect of household income on improving citizens’ pro-environmental behaviour differed according to pro-environmental activity levels. This finding reveals that the negative effect of reducing people’s involvement in environmental conservation is weak when they are less likely to participate in activities that sustain their natural environment. This finding suggests that individuals may experience time constraints when they contribute more to economic production.

Third, this study highlights the heterogeneous effects of socioeconomic, demographic, and psychological characteristics on individuals’ pro-environmental behaviour involvement. Policymakers expect the population to contribute to natural environmental conservation in order to create an eco-surplus society. The eco-surplus culture is represented as the set of societies’ pro-environmental behaviours; beliefs, values, and attitudes represent the culture shared by citizens as a result of contributing to natural environment’s conservation (Nguyen and Jones, 2022). Better comprehensive characteristics of knowledge level, educational attainment, well-being, and family structure may be associated with pro-environmental behaviour involvement. Improving pro-environmental behaviour is crucial for contributing to human society’s eco-surplus culture. Building a favourable eco-surplus culture or an eco-surplus business culture is believed to be important for solving issues affecting the natural environment (Nguyen and Jones, 2022; Vuong, 2021).

Limitations

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, for the sample collection process, this study relied mainly on an Internet survey that focused on Internet users. This process tends to include well-educated higher-income households. We conducted a face-to-face survey in five nations (including India) to address this issue. However, the sample selection problem that causes bias in the estimated parameters still exists. In future studies, comprehensive data should be collected to address the sample selection issue. Second, the association between comprehensive characteristics and pro-environmental behaviour was based on quantile and OLS regressions. Future work will investigate the causal relationship between people’s comprehensive characteristics and their pro-environmental behaviour. Furthermore, the variables are derived from the internet survey using the self-report method to collect information regarding the citizens’ pro-environmental behaviour and its determinant characteristics. However, when the dependent variables and the independent variables are from the same survey using the same response method, the regression results may occur the common method bias, and the results might affect the reliability or the validity of the regression results. For future work to address the common method bias, the comprehensive data collection method is recommended, such as the collection of the independent and dependent variables from different sources. Third, the large-scale original cross-sectional survey was conducted over three years for data collection; there may have been a change between 2015 and 2017 that may have affected people’s involvement in pro-environmental behaviour. In future studies, samples derived from each country should be encouraged.

Finally, this study applied self-reported measurement constraints with a binary choice of various types of environmentally friendly engagement to avoid measurement bias regarding the different standards in understanding the frequency of pro-environmental behaviour involvement. Accumulated involvement in pro-environmental behaviour was applied as the dependent variable in the quantile regression. The binary choice may still have a measurement bias to the individual’s pro-environmental behaviour involvement because the respondents had different knowledge and standards regarding natural environment conservation. In future studies, a comprehensive measurement of pro-environmental behaviour will be encouraged by applying quantile regression.

Data availability

The data is available upon request to the Xiangdan Piao or Shunsuke Managi. The requests for materials should be addressed to the authors, Xiangdan Piao or Shunsuke Managi.

References

Aizawa H, Yoshida H, Sakai S-I (2008) Current results and future perspectives for Japanese recycling of home electrical appliances. Resour Conserv Recycl 52(12):1399–1410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2008.07.013

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen I, Albarracín D (2007) Predicting and changing behavior: a reasoned action approach. In: Ajzen I, Albarracín D, Hornik R (eds) Prediction and change of health behavior: applying the reasoned action approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah

Akenji L, Chen H (2016) A framework for shaping sustainable lifestyles: determinants and strategies. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi

Akram F, Gill AR, Abrar ul Haq M et al. (2023) Barriers to enduring pro-environmental habits among urban residents. Appl Sci 13(4):2497. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042497

Akram R, Chen F, Khalid F, Huang G, Irfan M (2021) Heterogeneous effects of energy efficiency andrenewable energy on economic growth of BRICS countries: a fixed effect panel quantile regression analysis. Energy 215:119019

Aprile MC, Fiorillo D (2023) Other-regarding preferences in pro-environmental behaviours: empirical analysis and policy implications of organic and local food products purchasing in Italy. J Environ Manag 343:118174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118174

Arya B, Kumar H (2023) Value behaviour norm theory approach to predict private sphere pro-environmental behaviour among university students. Environ Clim Technol 27(1):164–176. https://doi.org/10.2478/rtuect-2023-0013

Barr S, Shaw G, Gilg AW (2011) The policy and practice of ‘sustainable lifestyles. J Environ Plan Manag 54(10):1331–1350. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2011.574996

Barszcz SJ, Oleszkowicz AM, Bąk O et al. (2023) The role of types of motivation, life goals, and beliefs in pro-environmental behavior: the self-determination theory perspective. Curr Psychol 42:17789–17804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02995-2

Binder M, Blankenberg A-K, Guardiola J (2020) Does it have to be a sacrifice? Different notions of the good life, pro-environmental behavior, and their heterogeneous impact on well-being. Ecol Econ 167:106448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106448

Binder M, Blankenberg A-K, Welsch H (2020) Pro-environmental norms, green lifestyles, and subjective well-being: panel evidence from the UK. Soc Indic Res 152(3):1029–1060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02426-4

Bülbül H, Topal A, Özoğlu B et al. (2023) Assessment of determinants for households’ pro-environmental behaviours and direct emissions. J Clean Prod 415:137892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137892

Byrne S, O’Regan B (2014) Attitudes and actions towards recycling behaviours in the Limerick, Ireland, region. Resour Conserv Recycl 87:89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2014.03.001

Carducci A, Fiore M, Azara A et al. (2021) Pro-environmental behaviors: determinants and obstacles among Italian university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:3306. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063306

Chan HW, Tam KP, Hong YY (2023) Does belief in climate change conspiracy theories predict everyday life pro-environmental behaviors? Testing the longitudinal relationship in China and the US. J Environ Psychol 87:101980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.101980

Chavan P, Sharma A (2024) Religiosity, spirituality or environmental consciousness? Analysing determinants of pro-environmental religious practices. J Hum Values 30(2):160–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/09716858231220689

Chawla L, Cushing DF (2007) Education for strategic environmental behavior. Environ Educ Res 13(4):437–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701581539

Chwialkowska A, Bhatti WA, Glowik M (2020) The influence of cultural values on pro-environmental behavior. J Clean Prod 268:122305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122305

Clark CF, Kotchen MJ, Moore MR (2003) Internal and external influences on pro-environmental behavior: participation in a green electricity program. J Environ Psychol 23(3):237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(02)00105-6

Clark WAV, Yi D, Huang Y (2019) Subjective well-being in China’s changing society. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116(34):16799–16804. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1902926116

Clayton S, Devine-Wright P, Stern PC et al. (2015) Psychological research and global climate change. Nat Clim Change 5:640–646. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2622

Cologna V, Berthold A, Siegrist M (2022) Knowledge, perceived potential and trust as determinants of low- and high-impact pro-environmental behaviours. J Environ Psychol 79:101741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101741

De Groot JIM, Steg L (2009) Mean or green: which values can promote stable pro-environmental behavior? Conserv Lett 2(2):61–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2009.00048.x

Dietz T, Gardner GT, Gilligan J et al. (2009) Household actions can provide a behavioral wedge to rapidly reduce US carbon emissions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(44):18452–18456. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0908738106

do Canto NR, Grunert KG, Dutra de Barcellos M (2023) Goal-framing theory in environmental behaviours: review, future research agenda and possible applications in behavioural change: review. J Soc Mark 13(1):20–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-03-2021-0058

Du S, Cao G, Huang Y (2024) The effect of income satisfaction on the relationship between income class and pro-environment behavior. Appl Econ Lett 31(1):61–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2022.2125491

Dupont DP (2004) Do children matter? An examination of gender differences in environmental valuation. Ecol Econ 49(3):273–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.01.013

Durand M, Smith C (2013) The OECD approach to measuring subjective well-being. In: Helliwell J, Layard R, Sachs J (eds) World happiness report 2013. UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network, New York, p 112–137

Eriksson L, Garvill J, Nordlund AM (2008) Acceptability of single and combined transport policy measures: the importance of environmental and policy specific beliefs. Transp Res A Policy Pract 42(8):1117–1128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2008.03.006

Essl A, Steffen A, Staehle M (2021) Choose to reuse! The effect of action-close reminders on pro-environmental behavior. J Environ Econ Manag 110:102539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102539

Fan L, Liu G, Wang F et al. (2013) Water use patterns and conservation in households of Wei River Basin, China. Resour Conserv Recycl 74:45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.02.017

Ghosh A, Satya Prasad VK (2024) Evaluating the influence of environmental factors on household solar PV pro-environmental behavioral intentions: a meta-analysis review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 190:114047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.114047

Greene W (2012) Econometric analysis, 7th edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Gifford R, Nilsson A (2014) Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int J Psychol 49(3):141–157

Hamann KRS, Reese G (2020) My influence on the world (of others): goal efficacy beliefs and efficacy affect predict private, public, and activist pro‐environmental behavior. J Soc Issues 76(1):35–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12369

Hansmann R, Bernasconi P, Smieszek T et al. (2006) Justifications and self-organization as determinants of recycling behavior: the case of used batteries. Resour Conserv Recycl 47(2):133–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2005.10.006

Hansmann R, Laurenti R, Mehdi T et al. (2020) Determinants of pro-environmental behavior: a comparison of university students and staff from diverse faculties at a Swiss University. J Clean Prod 268:121864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121864

Hasan A, Zhang X, Mao D et al. (2024) Unraveling the impact of eco-centric leadership and pro-environment behaviors in healthcare organizations: role of green consciousness. J Clean Prod 434:139704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139704

Helliwell JF, Aknin LB (2018) Expanding the social science of happiness. Nat Hum Behav 2:248–252. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0308-5

Ho M-T, Mantello P, Ho M-T (2023) An analytical framework for studying attitude towards emotional AI: the three-pronged approach. MethodsX 10:102149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2023.102149

Hogg TL, Stanley SK, O’Brien LV et al. (2024) Clarifying the nature of the association between eco-anxiety, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviour. J Environ Psychol 95:102249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2024.102249

Hynes N, Wilson J (2016) I do it, but don’t tell anyone! Personal values, personal and social norms: can social media play a role in changing pro-environmental behaviours? Technol Forecast Soc Change 111:349–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.06.034

Islam M, Managi S (2019) Green growth and pro-environmental behavior: sustainable resource management using natural capital accounting in India. Resour Conserv Recycl 145:126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.02.027

Jaime M, Salazar C, Alpizar F et al. (2023) Can school environmental education programs make children and parents more pro-environmental? J Dev Econ 161:103032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2022.103032

Jin R, Wang X (2022) Somewhere I belong?” A study on transnational identity shifts caused by “double stigmatization” among Chinese international student returnees during COVID-19 through the lens of mindsponge mechanism. Front Psychol 13:1018843. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1018843

Jin R, Wang X, Nguyen M-H et al. (2023) A dataset of Chinese drivers’ driving behaviors and socio-cultural factors related to driving. Data Brief 49:109337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2023.109337

Kahn ME (2007) Do greens drive hummers or hybrids? Environmental ideology as a determinant of consumer choice. J Environ Econ Manag 54(2):129–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2007.05.001

Kahneman D, Deaton A (2010) High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107(38):16489–16493. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1011492107

Kahneman D, Krueger AB, Schkade DA et al. (2004) A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: the day reconstruction method. Science 306(5702):1776–1780. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1103572

Karp DG (1996) Values and their effect on pro-environmental behavior. Environ Behav 28:111–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916596281006

Kasser T (2017) Living both well and sustainably: a review of the literature, with some reflections on future research, interventions and policy. Philos Trans R Soc A 375:20160369. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2016.0369

Kaur K, Kumar V, Syan AS et al. (2021) Role of green advertisement authenticity in determining customers’ pro‐environmental behavior. Bus Soc Rev 126(2):135–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/basr.12232

Kautish P, Sharma R (2020) Determinants of pro‐environmental behavior and environmentally conscious consumer behavior: an empirical investigation from emerging market. Bus Strat Dev 3(1):112–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.82

Klöckner CA, Oppedal IO (2011) General vs. domain specific recycling behavior—applying a multilevel comprehensive action determination model to recycling in Norwegian student homes. Resour Conserv Recycl 55(4):463–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2010.12.009

Lange F, Dewitte S (2019) Measuring pro-environmental behavior: review and recommendations. J Environ Psychol 63:92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.04.009

Li D, Zhao L, Ma S et al. (2019) What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour Conserv Recycl 146:28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.024

López-Mosquera N, Lera-López F, Sánchez M (2015) Key factors to explain recycling, car use, and environmentally responsible purchase behaviors: a comparative perspective. Resour Conserv Recycl 99:29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.03.007

Lundin A, Hallgren M, Theobald H et al. (2016) Validity of the 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire in detecting depression in the general population. Public Health 136:66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.005

Lynas M, Houlton BZ, Perry S (2021) Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Environ Res Lett 16(11):114005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966

Mantello P, Ho M-T, Nguyen M-H et al. (2023) Machines that feel: behavioral determinants of attitude towards affect recognition technology—upgrading technology acceptance theory with the mindsponge model. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:430. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01837-1

Mavisakalyan A, Sharma S, Weber C (2024) Pro-environmental behavior and subjective well-being: culture has a role to play. Ecol Econ 217:108081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.108081

Meyer A (2015) Does education increase pro-environmental behavior? Evidence from Europe. Ecol Econ 116:108–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.04.018

Naz S, Jamshed S, Nisar QA et al. (2022) Green HRM, psychological green climate and pro-environmental behaviors: an efficacious drive towards environmental performance in China. In: Springer Behavioral & Health Sciences (ed) Key topics in health, nature, and behavior. Springer Nature Switzerland, Champagne, p 95–110

Nguyen M-H, Jones TE (2022) Building eco-surplus culture among urban residents as a novel strategy to improve finance for conservation in protected areas. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9:426. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01441-9

Nguyen M-H, La V-P, Le T-T et al. (2022) Introduction to Bayesian Mindsponge Framework analytics: an innovative method for social and psychological research. MethodsX 9:101808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2022.101808