Abstract

This research explores the intricate nexus of gender, technology, nationalism, and misogyny within the context of China’s digital realm. Positioned against the backdrop of an internet celebrity’s accusation towards Apple, the study critically examines a uniquely crafted narrative that adds socio-cultural dimensions to Apple’s perceived network misrepresentations. Female iPhone users are strategically criticized as intellectually inferior influencers of societal contributions, reflecting prevalent discussions regarding 5G technology. The narrative further stigmatizes female iPhone users with implications of involvement in sex work, leading to significant brand implications. Rooted in the framework of Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis (FCDA) and assisted with the approach of corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis (CADA), this study deciphers the complex narrative, focusing on themes of cyber misogyny, economic stratification, and nationalism. The research further reveals how this criticism toward female iPhone users extends beyond mere resentment, unveiling deeper foundations of nationalism and threat perceptions toward traditional phallocentric dominance. The term “traitors” allocated to female iPhone users rationalizes the ongoing assaults as patriotic endeavors, bellwethering toxic nationalism that marginalizes minoritized individuals. This scholarly examination underscores social media platforms, with a focus on Douyin, as potent venues for reinforcing gender bias, particularly through their algorithmic recommendations, content moderation practices, and governance models. This delineation emphasizes the critical need for ongoing sociocultural and digital discourse to challenge and mitigate these dominant, biased narratives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advancing within the dynamic digital realm of China, this study is drawn towards a unique narrative that gained momentum on the back of an internet celebrity—Xiang Ligang’s accusation of Apple and its alleged misleading network indicators. Xiang, a figure of considerable controversy within the domain of Chinese social media, proclaims himself to be a seasoned observer of China’s Information and Communication Technology (ICT) industry. His online discourse, however, is frequently imbued with populist and nationalist undertones, exhibiting a penchant for intertwining technological debates with broader social issues, including politics and gender. This convergence of themes is not simply by chance, but seems to be a strategic maneuver intended to enhance his presence and impact across the digital landscape.

In September 2023, Xiang ignited a multifaceted debate on various Chinese social media platforms following an incident involving the ostensible display of a 5G network signal on an iPhone within Beijing’s Line 10 subway, a technological feat his Huawei 5G device failed to mirror. After seeking clarification from China Unicom and Beijing Unicom personnel, Xiang was informed that the 5G network was not yet operational on that particular subway line. This prompted him to vociferously accuse Apple of deceptive practices regarding its product’s network capabilities. While the initial premise of Xiang’s critique might seem confined to the technical domain of ICT, his allegations swiftly transcended the boundaries of mere technological misrepresentation. In this peculiar shift of attention, the celebrity extrapolated Apple’s purported network misrepresentations into a broader discourse. Here, the critique of its user base highlighted not only symbolic divisions of class and gender, but also implied a judgment on their intellectual capacity, essentially branding them as having inferior “wisdom” or intellectual capabilities. Among the base, female iPhone users were positioned as intellectually deficient and misguided influencers of societal contributions, a sentiment that resonates within the larger conversation around 5G technology.

Analyzing this intriguing discourse spectacle, a few noteworthy elements come to the fore. A significant aspect of Xiang’s argument emerges from a comparative evaluation he performed between iPhone and his personal Huawei device. Curiously, Xiang’s statements were disseminated during a critical period: the launch of iPhone 15 and the fierce competition with Huawei Mate 60 in the Chinese market. Particularly noteworthy was the phrase “Far Ahead” associated with Huawei, which, while not an official branding slogan, gained significant traction in Chinese cyberspace during this period. This elicited fervent nationalist sentiment. Though this phrase’s reference point remained implicit, it seemed to be fairly self-evident.

Simultaneously, this was not an isolated event. Multiple opinion leaders offered various interpretations orbiting around the rivalry between Huawei and Apple, elevating consumer choices to the level of national competition and patriotic sentiment. Prominently, Zhang Weiwei, the Dean of China Studies Institute at Fudan University, provides a compelling example. In a popular TV show titled “China Now”, Zhang used a distinct Sino-American nationalist narrative to thrust Huawei’s phone launch into a broader national discourse:

“Reflecting back on the onset of the Sino-US trade and tech war five years ago, we noticed the pessimistic noises in the Chinese society… Recently, the new Huawei phone emerged triumphantly. Using Huawei’s self-developed Kirin 9000S chip and HarmonyOS, with over 10,000 indigenously manufactured components, its performance has reached world-class standards… This signifies that the tech war initiated by the U.S. against China has failed…”

He explicitly called for popular support for Huawei over the U.S. from a nationalist standpoint: “Our program has witnessed the entire journey from Ms. Meng Wanzhou’s unlawful arrest in Canada, to Huawei’s repeated sanctions by the U.S., to the current ‘Far Ahead’. We have always stood firmly with Huawei, holding a pessimistic view towards the U.S…” (Observer.net, 2023)

In the discourse, Zhang’s remarks position Huawei’s “Other” distinctly as Western national entities, notably the United States, rather than corporate competitors. This narrative, intertextually resonant with Xiang’s commentary, triggered widespread resonance among the Chinese populace. In this discursive realm, Huawei is conflated with China, while iPhone emerges as a symbol of the United States—a connotation further validated by recent official Chinese media rhetoric. A poignant illustration of this phenomenon occurred on February 29, 2024, when President Biden announced an investigation into Chinese-made cars, amid which U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo equated Chinese-connected vehicles on American roads to iPhones on wheels, during a March 1 MSNBC interview, implying a national security threat. To this, Chinese diplomat Hua Chunying retorted, reminding that iPhones in China are also American products (Xinhua, March 4, 2024). This exchange accentuated the trend of nationalizing smartphone brands on Chinese social media, thereby underscoring the significance of this study’s exploration.

The discourse analysis elucidates a profound nexus between techno-nationalism and techno-strategic narratives within Sino-American dynamics, where technology brands assume national identities, transcending market rivalry to embody geopolitical competition, power assertion, and identity crafting. Intriguingly, this elevation of technology brands as national emblems not only fosters techno-nationalistic fervor but entangles with gender issues, particularly misogyny, in complex ways. This intersectionality suggests that the techno-nationalistic sentiments pervasive in Chinese internet discourses concurrently engage with and perpetuate gender-based biases, indicating a layered construct where technology consumption and nationalism intersect with gender discourse, revealing nuanced socio-cultural implications within the techno-political landscape.

Within the distinctive socio-political landscape of China, the quest for legitimacy by feminism encounters formidable obstacles, largely attributable to its exclusion from the dialogue and narratives sanctioned by the state (Zeng 2020). The Chinese government’s approach to online feminist activism is marked by a nuanced and sometimes contradictory posture, characterized by actions that range from the overt censorship of feminist content to the outright suspension of activists’ social media accounts (Fincher 2016). Such a strategy reveals a complex relationship with the movement, oscillating between active suppression and a seemingly indifferent allowance of its existence, thereby cultivating a terrain rife with “state-sanctioned misogyny” (Han 2018). Consequently, this ambivalence from the state not only legitimizes but also inadvertently fuels the spread of misogynistic ideologies across digital platforms, complicating the struggle for gender equality.

Over the course of the following month, Xiang’s comments were extensively recirculated, dissected, and amplified across various platforms, with a significant volume of discourse emerging on Douyin(TikTok China). Given its format, Douyin facilitated concentrated discussions beneath each video, allowing for an aggregated collection of public opinions on this matter. The platform, boasting a diverse and extensive user demographic alongside high user engagement levels, surpasses other social media entities such as Toutiao, Zhihu, and Xiaohongshu in terms of the sheer volume and intensity of discourse around this event.

In the multifaceted landscape of China’s digital ecosystem, the variegated user demographics and engagement mechanics of platforms such as Zhihu, Xiaohongshu, Douyin, and Toutiao reveal intricate dynamics of digital culture and user interaction. Notably, Zhihu’s appeal to a predominantly academic and professional user base, with over 80% holding university degrees (Peng et al. 2021), contrasts sharply with the lifestyle-oriented and predominantly female audience of Xiaohongshu, which boasts a substantial monthly active user count of approximately 100 million, 83.4% of whom are women aged 25–35 (iResearch 2023). Furthermore, Toutiao and Douyin, surpassing Zhihu and Xiaohongshu in user volume, exhibit a broader and more diverse user engagement. Toutiao, a news and information platform, diverges significantly from Douyin, which captivates with short video content, embracing a comprehensive technological array including livestreaming, e-commerce, and digital entrepreneurship (Yu et al. 2023).

Douyin commands a mammoth user engagement with 600 million daily active users, encapsulating over half of the Chinese internet populace (Hu et al. 2022; Zhao 2021). Its technological ecosystem, encompassing features from livestreaming to e-commerce, fosters a comprehensive digital entrepreneurship landscape (Yu et al. 2023). However, the platform’s sophisticated use of algorithmic recommendations accentuates a propensity towards creating echo chambers, leading to homogenized user interactions (Gao et al. 2023). The enthrallment of users is further amplified by Douyin’s application of the hook model within its recommendation systems, fostering an addictive user engagement pattern (Wang and Spronk 2023; Zhu 2023). This dichotomy of technological facilitation and algorithmic entrapment presents a fertile ground for examining the intricate balance platforms maintain between enhancing user experience and the potential for digital echo chambers and addiction. Consequently, the selection of the ten most discussed Douyin videos regarding this incident, for the purpose of sourcing discourse data, enables a comprehensive analysis of the broader trends in social media sentiment among Chinese netizens.

Employing the strategic landscape of Douyin, a leading social media platform for creating and sharing short videos in China, the study seeks to unearth this nuanced narrative, reaching into its socio-cultural and political depths that span themes of cyber misogyny and nationalism rooted in technological consumption. By using corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis, it peels away the rhetorical layers encapsulating these themes, underscoring the timely relevance amidst China’s buzzing socio-political ecosystem.

The inquiry meticulously unwinds around three focal research questions:

RQ1: How are the images of the female iPhone user shaped in the discourse present in comments within pertinent Douyin videos?

RQ2: What strategies are employed in the discursive construction of these female images?

RQ3: In what ways does this construction resonate with the socio-political dynamics and cultural shifts currently sweeping across China?

Techno-nationalism and the feminine fault line: navigating the intersections of gender, allegiance, and technological discourse in China

The implicit linkage between product allegiance and intellectual deficiency—especially among female consumers—serves as a vivid illustration of how technological debates can be appropriated and recontextualized within wider societal critiques. Intriguingly, Xiang’s narrative takes a dip into controversial waters, implicating young and fashionable female iPhone users with unsavory connotations of being involved in sex work, consequently directing moral scrutiny towards this audience and creating unique implications for the brand.

Xiang’s comments sparked widespread discussion and resonance on social media, a phenomenon underpinned by the critical role that the informational technology industry, particularly ICT manufacturing, has played in China’s economic landscape since the adoption of the reform and opening-up policy. This sector has been strategically positioned within China’s economic transformation and structural adjustment agendas, marking a significant phase in the country’s post-Mao era. In this context, techno-science has been framed through Marxist discourse as “the primary productive force”, a perspective that has been consistently highlighted by the government through its emphasis on the contribution of science and technology to economic development (Hughes 2006, 23–30; Greenhalgh and Zhang 2019, 2–3).

Given this backdrop, there has been a growing public attention towards the development of indigenous ICT technologies in China, represented notably by Huawei. It is widely perceived that the advancements in 5G technology made by Chinese corporations like Huawei provide an opportunity to break the monopoly held by Western technology companies.

The fervor surrounding China’s ICT industry has culminated in the formation of a widely shared “socio-technical imaginaries” as articulated by Jasanoff and Kim (2015, 4). The controversy ignited by Xiang’s remarks exemplifies the nationalist hues that permeate the socio-technical imaginaries associated with China’s ICT sector. Embedded within a trinity of technology-development-nationhood, this nationalist narrative champions the growth of China’s ICT capabilities as pivotal to propelling the country towards becoming a leader in shaping the trajectory of technological evolutions, thereby transitioning China into a more advanced society independent of Western influence. This narrative resonates to a significant extent with the concept of “techno-nationalism” as observed within the United States (Johnstone 1988).

In the contemporary discourse surrounding technology consumption, the narrative surrounding the iPhone serves as a quintessential illustration of the reduction of technological complexity and dynamism to simplified nationalistic sentiments. Despite the iPhone’s genesis as a global amalgam—wherein its creation leverages the contributions of hundreds of companies worldwide, assembling technologies and components birthed from human ingenuity across diverse locales (Cheng 2015)—it is predominantly perceived within China as an unequivocally American product. This perception encapsulates a broader trend wherein the multifaceted intricacies inherent to technological development are obscured by and subsumed under nationalist emotions within the context of technology consumption.

This phenomenon evidences a pronounced shift in focus from acknowledging the global interconnectedness and collaborative efforts that define modern technological innovation, towards framing such technological artifacts within simplistic binaries of ownership and identity. Consequently, the consumer choices between Chinese smartphones (e.g., manufactured by Huawei) and the iPhone are conceptualized not merely as preferences based on features or quality but are imbued with profound implications for identity politics within the nationalist narrative. Herein, the decision to purchase a particular brand becomes a statement of allegiance, transforming these consumer products into symbols of ‘self’ and ‘other’ within the domain of nationalism.

Within the landscape of Chinese internet discourse, particularly regarding ICT, there emerges a critical intertwining of nationalistic fervor with concerns regarding gender, specifically misogyny. This confluence is partly attributed to the inherently masculine undertones of nationalist discourse. As Deckman and Cassese (2021) argue, national identity is often constructed through narratives of “masculinized memory, masculinized humiliation, and masculinized hope” (Enloe 1989: 44), embedding a gendered dimension into the fabric of nationalism. This synergy between nationalism and misogyny is not exclusively confined to the Chinese context but is broadly demonstrated within right-wing discourses and mobilization strategies in the West (Bjork-James 2020; Bratich and Banet-Weiser 2019; Guy 2021; Vowles and Hultman 2021; Wilson 2020).

Despite the extensive exploration of digital nationalism’s implications for state politics in China (Guo 2004; Hyun et al. 2014), there is a marked scarcity in scholarly engagement with the intersection of digital nationalism and misogyny within the Chinese milieu. While a few scholars, including Fang and Repnikova (2018), Liu and Deng (2020), Peng (2022), and Huang (2023), have paid attention to the coalescence of nationalism and misogyny in the context of Chinese nationalism, there remains a major omission. This neglect pertains to the nexus between digital nationalism rooted in technological consumption and misogyny, a gap that warrants critical examination given the significant role that technological consumption, exemplified by companies like Huawei, plays in amplifying misogynistic narratives within the current global political climate and the Chinese internet sphere.

Digital misogyny and gendered nationalism in post-reform gender politics in China

In the post-reform era of China, the terrain of gender politics has undergone significant transformation, marking a departure from the strides towards gender equality that characterized the early and mid-20th century. The resurgence of patriarchal norms within this contemporary context does not exclusively privilege men; rather, it unveils a nuanced landscape of gender inequality, where the sociocultural and economic disenfranchisement of certain male demographics, especially those of lower socioeconomic standing, becomes palpable (Wallis 2015).

The reassertion of patriarchal values in post-socialist China can be traced to the marketization policies initiated in the late 1970s, which precipitated profound shifts in the labor market. These shifts not only repositioned China within the global economic landscape but also inadvertently bolstered traditional gender roles, distinguishing between socially constructed gender roles and biologically determined sex differences. Some scholars believe that market forces inherently exacerbated gender gaps by undervaluing women’s technical skills (Liu 2014). But recent developments suggest that the challenges to achieving gender equality in China’s labor market are more complexly interwoven with demographic shifts due to an aging population and the nuances of international geopolitical tensions, rather than solely the consequences of economic restructuring. Concurrently, the revival of Confucian patriarchal ideologies, emphasizing women’s subservient roles, further compounded the marginalization of critical gender discourses, aligning with the Chinese strategic negation of challenges to established gender norms (Peng 2020).

A pivotal aspect of the evolving discourse on gender inequality is the masculine crisis, a phenomenon emerging from the socioeconomic displacements of the early reform period, notably among men laid off from state-owned enterprises. This crisis deepened with the heightened expectations encapsulated in wedding norms during the 1990s, demanding that men secure property and emerge as the primary financial providers to be deemed suitable for marriage (Yang 2017; Song and Hird 2014). The exorbitant surge in real estate prices exacerbated this crisis, engendering heightened anxiety among men concerning their desirability and financial worth as partners. This development reveals evolving gender perceptions that challenge traditional power relations, though from divergent experiential frameworks (Meng and Huang 2017).

In the landscape of China’s rapid socio-economic evolution under neo-liberal governance, an intricate paradox in gender dynamics unfolds. On one hand, this policy shift diverted focus from structural social issues, fostering divided opinions on gender issues and subsequently complicating the discourse on gender inequality and inadvertently nurturing the proliferation of misogynistic ideologies (Peng and Talmacs 2023; Feldshuh 2018; Han 2018). On the other, the same period heralded an era of unprecedented empowerment for women, witnessing a surge in activism. This activism, characterized by its extensive participation and increased visibility, underscores a complex interplay of policy shifts, societal perceptions, and the active agency of women in shaping their narratives (Wu and Dong 2019). However, the narrative deepens a perceptual dichotomy within society as Wu and Dong (2019) highlighted: while many proudly embrace feminist identity, they are concurrently stigmatized with the label “feminist”—a term burdened with negative connotations in popular understanding in China.

The dual nature of this era—with its policy-driven focus shifts and the rise of women’s movements—outlines a dynamic yet contradictory panorama of gender dynamics in modern China. Both aspects, although seemingly at odds, collectively underscore the nuanced landscape of gender relations, further complicating the fight against misogynistic ideologies.

Chinese women confront a myriad of challenges in the digital realm, not least of which being the pronounced anti-feminist sentiment prevalent online (Han 2018). An adverse digital sphere towards women is perpetuated through active male denial of and defense for their improper conduct, coupled with a conservative opposition rooted in public intellectual discourse (Xu and Tan 2020; Ling and Liao 2020). These adversities enable digital feminism stigmatization, painting it as a malevolent western schema designed to undermine societal stability (Huang 2022). Such officially endorsed narratives propagate a cyber environment hostile to both Chinese feminists and the broader female population. The critique on China’s digital photography exhibition, The Vagina Monologues, reveals ubiquitous cyber gender discrimination and misogyny (Huang 2016). It attests to how feminism, egregiously misrepresented as a morally corrupt, foreign-imported aristocratic plot, draws ire, and backlash. Further exacerbating the situation, Liu and Dahling (2016) assert the widespread and distorted perception of feminism as akin to “western feminist Orientalism”, thus dismissing it as an alien construct and emboldening calls to purge such influences.

In contemporary society, the manifestation of reactionary masculinities bifurcates into two primary forms: antifeminist counter-discourse and individualistic responses rooted in masculinist principles that foreground hegemonic traits while sidelining inclusive norms (Messner 1998; Connell 2005; Banet-Weiser 2018). In the context of digital feminism in China, this global trend finds its parallel, with observed phenomena aligning more closely with the latter category, particularly in the sphere of social media. Notably, there exists a marked trend of social media users exhibiting extreme reactions and verbal denigration towards ordinary female iPhone users. This trend underscores that digital misogyny in China transcends simple antifeminist rhetoric, encapsulating a wider array of behaviors that align with a hegemonically masculinist agenda.

The digital landscape, significantly transformed by the rapid advancement of technology and the proliferation of social media, serves as a fertile ground for the propagation of misogynistic ideologies. Ging et al. (2020) identifies the rapid dissemination of Red Pill ideology across online platforms, such as Angry Harry and Reddit, as emblematic of this shift towards an increasingly networked misogyny (Banet-Weiser and Miltner 2016). This phenomenon is further exacerbated by content regulation and moderation practices that often fail to adequately address the nuance of misogynistic content, along with recommendation algorithms that inadvertently promote the circulation of anti-feminist narratives. These digital mechanisms not only facilitate the widespread distribution of misogynistic expressions but also unite disparate groups through a shared commitment to hegemonic masculinity, effectively bolstering a unified opposition to feminist progress.

The Chinese state’s nuanced approach to feminism, juxtaposing overt suppression of activist movements with a purportedly ambivalent stance towards feminist ideology, inadvertently amplifies misogynistic undercurrents on social media platforms. As delineated by Zeng (2020) and Peng (2019), this dichotomous governance strategy not only curtails the feminist collective momentum but, paradoxically, facilitates the diffusion of misogynistic sentiment. Moreover, the ‘platformization of misogyny’, as expounded by Liao (2023) through the incident involving Yang Li and Mercedes-Benz on Weibo, unravels the mechanisms by which misogyny is engineered and magnified, highlighting the complicit role of digital infrastructures and algorithmic methodologies. Complementary analysis by Huang (2023) on the portrayal of female intellectuals within Chinese social media further elucidates the disparaging discourses that entrench societal antipathy toward women’s empowerment.

With the rise of online misogyny, an escalating concern in the face of gender inequality, international scholarship across a spectrum of disciplines has turned its attention to this issue due to its universal presence and pronounced aftermaths (Banet-Weiser and Miltner 2016; Cole 2015; Dickel and Evolvi 2022; Aiston 2023). Authorities such as Banet-Weiser (2018) and Siapera (2019) underscore the usage of established conservative ideologies by Western Anti-feminism and misogyny in fueling online hatred against women. Megarry (2014) posits women are victimized due to their femininity and affronted with belittling stereotypes. Adding complexity, Banet-Weiser (2018: 35) epitomizes anti-feminist and misogynist reasoning to society’s ruin by feminists, reflected by the trope of men being “harmed” by women, thus stimulating reactionary patriarchal resurgence to counter this constructed crisis (Anderson 2014).

In contemporary discourse, digital misogyny within China encapsulates both global tendencies and distinct local features. While nationalism serves as a conduit for misogyny in Western contexts (Deckman and Cassese 2021), it adopts a uniquely gendered dimension within the Chinese internet sphere. Nagel (1998) posits that western nationalist politics constitute a significant arena for enacting masculinity. Similarly, the ascendancy of nationalist sentiments on the Chinese internet has gendered implications, prominently manifesting as a form of digital misogyny intertwined with nationalist rhetoric. This marriage of misogyny and nationalism, especially predominant among male netizens, exacerbates gender power imbalances online (Fang and Repnikova 2018). Despite apparent growth in women’s engagement in Chinese digital nationalism, Fang and Repnikova (2018) elucidate that this participation is often misrepresented by male nationalists to undermine and critique their perspectives, perpetuating a masculinized vision of nationalism. This is emblematic of the broader patriarchal structuring of digital spaces, where nationalist discourse weaponizes gender biases.

A particularly stark illustration provided by Cheng (2011) is the vitriolic discourse surrounding transnational marriages. Here, marriages between Chinese women and non-Chinese men are derogatorily framed as a threat to the “Chinese racial stock”, highlighting how nationalist rhetoric is employed to perpetuate both xenophobic and misogynistic narratives. Extending this analysis, the present study observes a similar logic, albeit transposed from the domain of matrimonial alliances to the consumerist milieu of ICT product consumption. In this arena, domestic brands such as Huawei are emblematically aligned with the notion of “Chinese racial stock”, placing them within a nationalist discourse. Conversely, female consumers of Apple products are denigrated as internal “Others”, analogously vilified to Chinese women who marry non-Chinese men. This deconstruction elucidates a broader trend where consumer choices, particularly in the realm of ICT, become battlegrounds for enacting and contesting nationalist identities. The disparagement faced by female Apple users illuminates how consumerism, intertwined with gender and nationalism, constructs new forms of digital misogyny.

Digital technologies and information infrastructure in China have significantly bolstered the state’s advanced censorship mechanisms and surveillance capabilities (Schneider 2018). This infrastructure enhances the state’s control over public discourse by monitoring the internet, deleting undesirable content, and scrutinizing citizens’ private lives. Given this level of control, certain narratives, especially those embedded in techno-nationalism, are considered safe and are, therefore, often extensively propagated. Claims about the alleged falsification of foreign digital communication technologies, for instance, possess high viral potential on Chinese social media due to their alignment with state-endorsed nationalism.

In today’s digital economy, social media metrics such as page views and likes are monetized to generate profit (Marwick 2013). To maximize these profits, Chinese social media platforms align closely with state ideologies, including consumer nationalism endorsed by the state. They operate under techno-nationalist regulations that compel them to use nationalism explicitly to drive sales. Plantin and de Seta (2019) effectively argue that WeChat epitomizes this phenomenon; its extensive scale and ubiquity make it indispensable for advancing the state’s techno-nationalist and cyber-sovereignty agendas (Qiu 2010; Liao and Xia 2023). Consequently, these platforms seamlessly integrate nationalistic narratives into their business strategies. Douyin’s algorithmic infrastructure similarly influences content dissemination by prioritizing engagement and virality, often amplifying content that evokes strong emotional reactions, including nationalist sentiments. As of July 2024, the incident discussed in this study remains a trending topic on Douyin, evidenced by hashtags such as #假5g (#Fake5G), #苹果假5g (#AppleFake5G), and #苹果14假5g (#Apple14Fake5G), collectively garnering over 20 million views. The iPhone itself, as a high-engagement tag, underscores this further, with #iPhone14 amassing over 1.9 billion views. Influencers on Douyin strategically use these hashtags to enhance the reach and engagement of their videos, thus maximizing interaction and visibility.

However, while overt expressions of digital misogyny may be less prevalent due to potential sensitivity, they manifest in more covert forms within the comments sections of these videos. Douyin inadvertently supports the wide distribution of such misogynistic discourse under the broader umbrella of techno-nationalism. This study explores the distinct misogynistic digital narratives targeting female iPhone users in China, conceptualizing them as the by-product of an amalgamation of various socio-cultural and political threads. Factors such as the resistant legacies of Confucian patriarchy, the shifting dynamics in the post-socialist era, and rising nationalism present a unique matrix contributing to this relatively unexamined form of cyber-misogyny. We argue that this Chinese cyber-misogynistic phenomenon, given its heterogeneity, must be examined within its contextualized specificity, much like global cyber-feminism’s varied activism forms and experiences. The findings identify an alarming merger trend of digital misogyny, socio-economic disparities in technology usage, and heightened nationalism, accentuated by recent western sanctions on Huawei. This underlines the need for an in-depth discourse analysis to demystify these interlocking digital narratives.

Methodological approach and Douyin corpus data

Corpus compiling

In the context of international and national power structures, mass media, particularly social media, play a crucial role (Barthel and Bürkner 2020). This research endeavors to implement a critical discourse analysis to examine the discourse orbiting around the subject of #项立刚质疑苹果5G造假# (#Xiang Ligang Questions Apple5G Fraud#), particularly on Douyin, a prominent social media platform in China known for creating and sharing short video content. Given its format, Douyin facilitated concentrated discussions beneath each video, allowing for an aggregated collection of public opinions on this matter. The platform, boasting a diverse and extensive user demographic alongside high user engagement levels, surpasses other social media entities such as Toutiao, Zhihu, and Xiaohongshu in terms of the sheer volume and intensity of discourse around this event. Consequently, the selection of discussion on Douyin regarding this incident enables a comprehensive analysis of the broader trends in social media sentiment among Chinese netizens.

The study was orchestrated by conducting a search for the hashtag #Xiang Ligang Questions Apple5G Fraud#, resulting in a collection of the ten most applauded short videos from Douyin. Comments from these videos were extracted for our research data by using the web crawling software “BaZhuaYu”(Octopus). To ensure compliance with ethical standards, all displayed data was anonymized to protect user privacy. We thoroughly reviewed ByteDance/Douyin’s policies on data access and scraping. According to their terms and conditions, restrictions primarily apply to unauthorized commercial use, modification of content, and actions that disrupt the service (e.g., Article 5.3 of Douyin’s policy). Since our data collection was conducted purely for academic purposes and with stringent measures to anonymize user information, we determined that our methodology adheres to these guidelines.

Rigor in data collection was sustained by excluding any content that did not align with our subject of study, such as promotional content, comments that were exclusively emoji-based, or those comments that merely referenced another user but lacked substantive content. Following a comprehensive sweep for data review and cleansing, our efforts culminated in the assembly of a corpus comprising 11,466 comments, an accumulation of 123,587 tokens.

To preprocess the data, we utilized the Gensim Jieba word segmentation toolkit (Yu et al. 2019). Additionally, we curated a stop word list by referencing several established sources such as the Library of Chinese Stop Words, the Stop Words of Harbin Institute of Technology, the Stop Words List of Baidu, and the Library of Stop Words in the Robot Intelligence Laboratory of Sichuan University (Zhang, 2022). These stop word lists are commonly employed in Chinese text processing to filter out frequently occurring words that lack significant semantic value. Moreover, for improved word segmentation accuracy, we integrated domain-specific custom dictionaries tailored to internet texts, developed based on pertinent domain knowledge to capture topic-specific terminology. Through these preprocessing measures, we ensured the cleanliness and optimization of the dataset for subsequent corpus analysis.

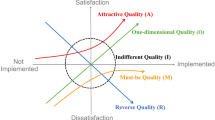

Methodology

Our primary theoretical perspective is rooted in Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis (FCDA), a concept introduced by Lazar (2007, 2017), premising upon Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) theory (Khosravinik and Unger 2016; Wodak and Mayer 2009). This approach, nested within the broader CDA framework, employs a feminist perspective to examine the construction, negotiation, and impact of gender ideologies and power dynamics within textual and discursive contexts (Tian and Ge 2024). While CDA on gender or feminist issues may address the language surrounding gender and feminism, FCDA specifically emphasizes power dynamics and how discourse is used to construct, perpetuate, or challenge gender inequalities and power imbalances. Specifically, FCDA places particular emphasis on advocating for gender equality, women’s rights, and challenging patriarchal norms. As such, the analysis is often geared toward revealing and addressing gender-based oppression and discriminatory discursive practices. Regarding the analyzing steps, we utilized Fairclough’s three-dimensional CDA model to scrutinize the complex representation embedded within the collected data. As delineated by Fairclough (2003), the CDA process encompasses three stages: (1) text description; (2) text interpretation—discourse practice; and (3) explanation of the connection between interaction and social context— social practice.

Our application of Fairclough’s three-dimensional model for CDA (Fairclough 2003) is meticulously tailored to foreground feminist inquiries into discourse. This adaptation intricately melds FCDA’s imperative with Fairclough’s methodological structure, ensuring a robust feminist critique is woven throughout the analysis. Initially, the text analysis phase employs a discerning approach to unravel linguistic and semiotic elements that reflect or challenge patriarchal constructs and gendered imbalances. The analysis is guided by feminist theoretical principles, aiming to unearth the subtle nuances of gender bias and norms deeply embedded within textual fabrics. Subsequently, the study progresses to the discourse practice phase, adopting a distinctly feminist lens to scrutinize procedural manifestations of discourse. This phase contemplates the dual role of discourse in either reinforcing existing gender disparities or serving as a conduit for feminist advocacy and emancipation. The final phase, exploring the linkage between discursive activities and the broader matrix of societal practices, incorporates a thorough feminist evaluation of social and cultural conventions. This comprehensive examination facilitates a deeper understanding of how discursive phenomena are enmeshed with, and perpetuate, patriarchal dominance and gender inequality.

In the analysis, we adhere to the conceptualization of discourse as proposed by Van Leeuwen, where discourse is envisaged as a social construction of reality about a certain aspect, epitomized as the “recontextualization of social practice” (van Leeuwen 2008). The utilization of this approach is deemed highly efficacious for its comprehensive evaluation of social phenomena, as it intricately examines both the social actors and their respective actions within the framework of social practices. According to Van Leeuwen, the constituents of social practice encompass elements such as “social actors,” “social actions,” “time,” and “space”, among others (van Leeuwen and Wodak 1999; van Leeuwen 1995, 1996, 2005). As the assumption aroused by van Leeuwen (2008) assuming that “meanings belong to culture rather than to language and cannot be tied to any specific semiotic”, we then discussed about how social actors be represented in the process of discourse practice.

To further effectively identify representations in the text description, the approach of corpus-assisted discourse analysis (CADA) is used. In corpus-assisted Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), it is crucial to consider the potential impact of analyst subjectivity and the differences in epistemologies between CDA and quantitative analysis. Analyst subjectivity can influence the interpretation of data and the identification of patterns within the corpus. This subjectivity underscores the importance of transparency and systematicity in the analysis process (Franklin 2017). Moreover, the integration of extra-corpus data can enhance the precision and persuasiveness of arguments made during the analysis (Franklin 2017). The use of corpus-assisted discourse analysis in examining various discourses, such as those found in newspapers or political contexts, can shed light on the evolution of terminology, stereotypes, and discursive practices (Rovelli 2021; Mohammad Rashid and Alshahrani 2019). By employing corpus-based methods, researchers can identify recurring patterns in language use, enabling a more in-depth critical analysis of discourses (Hart 2016). This approach also aids in addressing criticisms related to the texts analyzed in CDA methodology (Gabrielatos and Baker 2008). Corpus methods require a substantial collection of texts, enhancing the representativeness of research samples while minimizing researcher subjectivity. CADA, a quantitative-qualitative approach, has been successfully applied to analyze various phenomena like misogyny or xenophobia, including media representation of refugees (Baker and McEnery 2005) and gender identity, particularly within the LGBT community (Love and Baker 2015). Employing CADA principles, we examine insulting or abusive comments directed at female users on Douyin. Through corpus-linguistic methods such as lexical concordance, keyword analysis, and context-based inference, we adopt a bottom-up approach to uncover nuanced language patterns (Baker et al. 2008; Hunston 2002; Love and Baker 2015).

Through this rigorous process, we analyzed how these Douyin comments are articulated and how their textual features reflect of cyber misogyny, economic stratification, and nationalism. Firstly, we conducted a lexical network drawing within the compiled Corpus to identify key information related to the image construction. Secondly, we used the online corpus program Sketch Engine to extract keywords from the Corpus, with Chinese Web Corpus (zhTenTen) 2017 serving as the reference corpus (Baker 2006, p. 125). Statistical tests were applied to determine keywords, considering their frequency and total word count in the Corpus. We examined the top 10 keywords (p < 0.01) in the Corpus and analyzed their contexts, aiming for a methodological synergy in understanding the portrayal of female iPhone users.

Data analysis

Categorization of female images

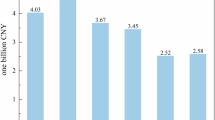

On the basis of the collected data, we utilized Rostcm6 software (a text mining software) to calculate the co-occurrence matrix and inputted the resulting matrix into Netdraw (network drawing software) to visualize the lexical network (referred to as Fig. 1). These analytical steps were undertaken to gain insights into the interconnectedness of keywords and to visually represent their relationships within the discourse surrounding the topic.

The lexical network depicted in Fig. 1 centralizes around “Apple” and “mobile phone”, and signifies the sociocultural dynamics related to the usage of these technological entities amongst certain female cohorts. It contains an array of designators for women varying from neutral (e.g., “lady”, “sisters”, “girls”) to derogatory (e.g., “bargirl”, “prostitute”, “unsophisticated young woman”), the latter explicitly pejorative terms used on Chinese digital platforms to belittle women in the service entertainment industry. A deeper analysis of this network reveals disturbing contours of prevalent attitudes and stereotypes. Negative adjectives like “garbage”, “ignorance”, and “vanity” illustrate a deeply rooted bias and derogative tone. Notably, the incorporation of professional references like “massage”, “nightclubs”, and “entertainment venues” indicate systemic stereotyping and objectification.

Another intriguing glimpse into this lexical network shows how iPhone has come to symbolize a form of status currency for these marginalized women, fostering an illusion of vanity despite economic constraints. Interestingly, nestled within this narrative is a counter-narrative of nationalism, seen in the preference for domestic brands like Huawei and Xiaomi, with the latter often cited as an embodiment of patriotic choice due to its affordability and technological prowess, over foreign counterparts. In essence, this semantic network unveils a disconcerting nexus of gender bias, derogation, objectification, and nationalism.

To gain deeper insight into the portrayal of female iPhone users within the collected comments, we utilized the online corpus analysis tool Sketch Engine. As is a common practice in corpus analysis, Baidu stop words list was used to exclude items that carry little semantic meaning in the compiled corpus. By inputting “女 (female)” “ 妹/姐 (sister) ”, of any part of speech, as the query word, we then extracted a sub-corpus that focuses on female delineation with 3624 words in total. Therefore, we identified the keywords within the sub-corpus, thereby focusing on the portrayal of females. Significantly, our analysis prioritized multi-word terms, particularly bi-lexical phrases, over single word terms. This choice is substantiated by literature indicating that such compound expressions are prevalent in the articulation of feminist concepts on the Chinese internet. Notable examples include pejorative terms like “feminist bitch” and “feminist cancer”(Mao 2020; Wu and Dong 2019), alongside potentially empowering terms such as “female fist” (Yang et al. 2022) and “female boxers”. The latter, originating from the Mandarin term “女权” (nǚ quán, feminism), which has been pejoratively reinterpreted as “女拳” (nǚ quán, female fist), represents a disparaging reframe of feminism. This colloquial twist implies feminists as belligerents, metaphorically “throwing wild punches” in pursuit of excessive privileges. “Female boxers” further amplifies this metaphor, depicting feminists as aggressors within a combative arena, thereby accentuating the hostile portrayal of feminist advocacies as overly confrontational within the digital discourse.

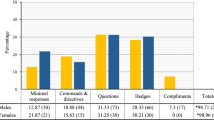

After disregarding irrelevant characters, the ten foremost multi-word terms(with the value of relative frequency per million of the keyword in the reference corpus <0.05, which signifies the significant difference) were extracted, as shown in Table 1. Each keyword carries potential implications in the analysis and can serve as a pathway into understanding the perceptions and societal narratives constructed around these females.

Table 1 delineates three key subcategories within this inherited narrative, illustrative of the multifaceted gender biases inherent in this virtual sociocultural milieu.

Primarily, the term “小姐(Xiao jie)” appeared in terms of “KTV 小姐”, “小姐 机”, and “夜店 小姐 专业”, despite its historic origins as a respectful nomenclature for women, has, in certain contemporary contexts, metamorphosed into a derogatory term as the meaning of “a prostitute”, frequently tied to the entertainment or service sectors, indicating a stereotypical perception and stigmatization of this profession by society. This stereotype emanates further resonance within related terms such as “nightclubs” and “KTV bar”, inferring these women’s affinities to nightlife entertainment environments. The term “Simp”, a societal tag usually denoting men who excessively pander to unreciprocating women, occurs steadily. The inference here emphasizes these women as manipulative exploiters, entrenching the stereotype deeper within this sub-cultural narrative.

Next, the term of “factory girl” bestows an additional dimension to the stereotype, hinting towards an assumed economic bracket and professional identity about these women. The tacit suggestion lies in a presumed class hierarchy where these female iPhone users are often on a lower economic rung and perhaps engaged as low-skill operatives.

Quintessential to the analysis is “traitor”, a term that houses a multifarious narrative encompassing consumer behaviors, gendered narratives, and nationalist sentiment. Its application labels women choosing iPhones—effectively choosing a foreign brand—traitors, thereby creating a potent stereotype that pivots consumer choices towards a reflection of nationalist loyalties. This incorporation of patriotic duty into material consumer selection is an understated facet in gender studies, and it allows an intriguing dimension for examination. Remaining keywords such as “nightclub prostitutes standard” and “males from abroad” contribute to a gendered discourse, underscoring the stereotype within issues of gender politics, power dynamics, and societal expectation.

This study reveals a convergence between our preliminary corpus analysis of stereotyping female iPhone users on Chinese social media and wider scholarly discourse examining the media representations of sexual harassment and violence victims. Numerous studies validate that sympathetic media coverage of such issues largely relies on perceived sexuality, socioeconomic status, education levels, race, and ethnicity of the victims (Boyle 2005; Meyers 2013). Analogously, we discern a multi-layered stereotype of female iPhone users in China, illustrating them as economically constrained individuals, predominantly entrenched in the entertainment sphere, thus objectified. This infers a suspicion surrounding their morality, socioeconomic standing, and educational pedigree. Simultaneously, the ascription of treachery, purely based on their consumer preferences, resonates with the academic focus on racial affiliations.

In the following section, we will conduct a detailed analysis of this intriguing sociocultural phenomenon through an examination of the concordance of the previously mentioned key words, especially “小姐(prostitute)” “舔狗(Simp)” “厂妹(factory girl)” “汉奸(traitor)”, which remains as the main representative of the identities in the comments. By locating these words within specific texts, we aim to explore the prevalent stereotypes associated with female iPhone users as observed in digital discourse.

Defamatory tactics: labeling female iPhone users as sex workers

The intersection of gender and technology consumption forms a discursive terrain where sexist ideologies operate, subtly reinforcing patriarchal dominance. Discourse, in this context, serves as both a reflection and creator of societal norms. Stereotyping female iPhone users, as revealed by concordances, illuminates a gendered discourse that perpetuates patriarchal hierarchy.

In the digital realm of China, the intersection of sexism and nationalism crystallizes around the consumer behavior of iPhone usage among women, which is disparagingly codified through the term “小姐”. For instance, users denigrate female iPhone consumers with remarks like, “The prostitutes in KTV bars and nightclubs prefer using Apple products” and “Apple has now become a subject of ridicule! It is humorously referred to as the professional phone for nightclub prostitutes”. This kind of discourse does not merely indulge in an overt disdain for women but strategically employs sexism as a tool to uphold patriarchal dominion, echoing Kate Manne’s (2017) exposition on sexism functioning as a structural mechanism to police and preserve patriarchal systems by rigorously monitoring and modulating female comportment. The pejorative designation of female iPhone users as “prostitutes”—heavily laden with sexual connotations and emblematic of skewed gender power relations—exemplifies a misogynistic discourse embedded deep within the fabric of societal narratives.

This gendered narrative engages in a dynamic interplay with the principles of digital nationalism. The assertive discourse evidenced through social actor networks—the “prostitutes” as iPhone users and a “commenting community” characterized by apparent misogyny—mires in a digital manifestation of “observational control” where certain netizens assumes the authority to surveil, adjudicate, and deride the technological and consumer choices of women, essentially perpetuating a public-private dichotomy entrenched in patriarchal discourse. This not only delineates a gendered hierarchy favoring misogyny judgments but also subtly intertwines with nationalist fervor by positing domestic consumer choices as emblematic of national loyalty, thereby rendering the preference for foreign brands like Apple a deviation from the norm, subject to public castigation.

Furthermore, the discursive linkage of female iPhone users with “prostitutes” orchestrates their alienation from heteronormatively defined female identities, echoing Christina (2012) insights into the ostracization faced by feminists diverging from the patriarchal normativity in postfeminist contexts. This process of “othering” not only margins these women within digital spaces but aligns with the broader mechanism of gendered nationalism that seeks to delineate and enforce boundaries of national identity through the policing of gender roles and consumer behaviors. The esthetic denigration of this group, as conceptualized by Hill and Allen (2021), mirrors the utilization of anti-feminist humor to amplify perceptions of irrationality, further exacerbating their perceived deviation from normative femininity and, by extension, national loyalty.

The disconcerting phenomenon of digital misogyny within China’s virtual landscape profoundly illustrates the confluence of gendered nationalism and patriarchal ideologies, propelling female iPhone users into a contentious arena of technological modernity versus traditional Confucian values. This narrative transmogrification renders women not as beneficiaries of technological advancement but as hyper-sexualized entities, divergent from prescribed societal norms, thereby perpetuating an online reinforcement of misogynistic paradigms. Such derogatory characterization extends and exacerbates the antiquated dichotomy of the mother/whore, which positions the “good” women - those seen as maternal, self-sacrificial, and conforming (Tian and Ge 2024; Ge and Tian 2024), against the “bad” women, relegated to promiscuity and consequent disregard (Nagle 2017). This polarized gender narrative not only leads to a moralizing reading of sex, but also necessitates the vilification of sex workers who are assumed to infringe upon the boundaries of traditional female etiquette.

The strategic diversion from the iPhone’s technological merits to its gendered implications epitomizes populism, wherein a facade of concern for moral and national integrity masks a deeper current of toxic masculinity and potent misogyny (Kantola and Lombardo 2019). This discourse is typified by quotes such as “in the past, Apple was a symbol of wealth, but now it is exclusively used by prostitutes” and “the users of Apple devices can generally be categorized into two groups: prostitutes and traitors”. This pattern is indicative of populist strategies that leverage gender discourse as a means to galvanize and manipulate public sentiment (Kantola and Lombardo 2019; Bracewell 2021), intertwining with class struggles and fears around national security to rally against perceived external and elite threats (D’Attorre 2019). Within this framework, the polarization between “common people” and “corrupt elites”—often depicted through the lens of technology adoption—emphasizes an anti-elite narrative fiercely embedded in populist strategies (Hameleers et al. 2017; Hawkins et al. 2018). This redirection from appreciation of innovation to gendered critique mirrors broader societal tensions, where women’s engagement with technology becomes a locus for asserting patriarchal control and upholding nationalistic purities against perceived Western decadence. This discourse remarkably politicizes technological preferences, where gadgets such as the iPhone transcend their utilitarian roles, becoming symbols in the larger ideological conflicts surrounding cultural authenticity, governance, and globalization resistance.

Factory girls vs. simps: encrypted class conflict and threatened masculinity

Within the arena of discursive analysis, the contours of gender portrayal often find their origins in pre-established patriarchal principles. Transgression from these norms is often construed as disconcerting within societal perspectives and structures. A notable manifestation this discourse presents itself through the distorted representation of women iPhone users as “厂妹(factory girls)”, a descriptor linked to working-class milieu. This metonymous depiction is discordant with the actualities of the Chinese smartphone market, wherein iPhones noted for their higher price points, substantially surpass the pricing metrics of brands like Huawei.

The “factory girls” discourse further imbue the purported correlation between subsets of socio-economic classes and their predilection towards specific technology brands. Interestingly, these extracts disclose an incremental expansion in the classes represented, which is evident in statements like: “After observing for these days, it is indeed a fact that businesspeople, teachers, and civil servants typically use Huawei. On the other hand, KTV prostitutes, bartenders, and factory girls tend to use Apple. It’s really true.” Here, we discern the introduction of additional social actors: businesspeople, teachers, civil servants, who are synonymous with Huawei, while “KTV prostitutes”, bartenders, and “factory girls” are associated with the use of iPhones. Manifestly, such discourse appears to construct two widely disparate social strata based on technology brand consumption habits. Albeit the class construction starkly deviates from conventional wisdom, it intriguingly emphasizes the prevalent perceptions of social classes linked to their tech-usage behaviors. Notably, the extracts are replete with a plethora of words amplifying emotive undertones and modal affirmation, such as “indeed”, “true”, “certain”, and “undeniable”. This language usage suggests a heightened certainty of the actors’ social positioning based on their implied cell-phone brand preference, clearly demarcating them through social stratifications.

Wu and Dong’s (2019) scholarship provides a significant interpretive lens to unravel the latent motives driving the evident class divisions within the discourse unparsed from the comments section. They present an insightful conceptualization of misogyny as arising from unease surrounding economic disparities. This conflict, they argue, extends beyond the superficial realm of gender strife, unfolding instead as a veiled struggle of class dynamics meriting comprehensive scrutiny. Drawing from the analytical scaffolding outlined by Wu and Dong (2019), it transpires that such discussion subtly aims to undermine the socio-economic stature of female iPhone users. The discourse, interwoven with intricate associations of smartphone brand affinity with facets of social stratification and economic acumen, endeavors to mask organic apprehensions incited by these women’s consumer prowess.

The discourse surrounding women’s consumption of iPhones in China, and the consequent backlash from internet users, finds its roots deeply embedded in the dynamics of digital misogyny and gendered nationalism, revealing a complex interplay of societal transformation, anxiety, and power reconstitution. Manne (2017) captured this discriminatory treatment faced by women within the philosophical construct of misogyny. This concept targets and marginalizes “unbecoming women”, particularly those posing threats to hierarchical power structure by challenging the autarky traditionally held by men.

As iPhone-owning women, through their consumption behaviors, subtly challenge the societal and economic supremacy of Chinese males, these women engender an economic structural evolution. Despite the scarcity of comprehensive surveys addressing gender and income among Chinese smartphone consumers, available economic data shed light on a consumption-based misogyny, possibly rooted in a long-standing gender preference differentiation within China’s mobile phone industry. A 2018 survey indicated that women accounted for a slightly higher market share (50.1%) in the smartphone sector compared to men, with the iPhone’s market share standing at 26.5%. Notably, female users of iPhones (15%) significantly outnumbered their male counterparts (11.5%). Conversely, for domestic brands like Huawei and Xiaomi, which together held a market share of 27.6%, male users approximately doubled the female user base (MobTech 2024). Fast forward to 2024, brands such as Huawei have surpassed Apple in market share within China (IDC 2024). Further investigation reveals that among Chinese youth born between 1995–1999, Huawei emerged as the most preferred brand among males (33.7%), with a considerable proportion of these male “Huawei Youth” earning less than 5,000 RMB per month (MobTech 2021). By current exchange rates as of 2024, where 1 RMB equals 0.14 USD, this income level translates to approximately 700 USD monthly. This financial demarcation, particularly among male consumers favoring domestic brands such as Huawei and Xiaomi, points to a broader socio-economic narrative. It suggests a divergent consumer base where the allure of premium brands like iPhone among female users not only reflects their purchasing power but subtly contests traditional gender roles and socio-economic hierarchies by favoring globally recognized, higher-priced smartphones. In this transformation process from socioeconomic reliance on males to independent, sophisticated consumerism, women’s actions provoke anxieties amongst men, threatening patriarchal narratives of male predominance (Banet-Weiser 2018).

Probing further into the economic frameworks, iPhone emerges as a symbol of affluence, unveiling gender-disparities inherent in economic resource distribution. This revelation destabilizes the conventional male role as primary providers. The increased economic independence of women and their active participation in luxury tech consumerism can potentially intimidate and emasculate male power. This discourse propounds a narrative of resource expropriation by women, notably iPhone users, from men. The strategized stigmatization and delegitimization of women iPhone users’ tech-consumption behaviors attempts to alleviate male anxieties borne from class discrepancies that have become increasingly pronounced two decades into the twenty-first century. This period, characterized by China’s remarkable economic ascent yet accompanied by the gradual ossification of social strata, also marks a pivotal era for the empowerment of women. It witnessed an unparalleled flourishing of women’s agitation, notable both for its widespread participation and heightened visibility (Wu and Dong 2019). This consequently reestablishes male hegemony within a shifting cultural paradigm.

In the discourse analyzed within this study, a notable deviation from the conventional critique of Western consumerism, epitomized by the iPhone, is observed. Rather than indicting the iPhone as a symbol of Western extravagance, the narrative intriguingly elevates domestic brands such as Huawei, while concurrently relegating the iPhone to a token of “inferior femininity”. This discursive maneuver effectively accomplishes a cognitive displacement and transcendence of the iPhone, positioning it as a product catered towards a denigrated female demographic. This recontextualization not only subverts the expected valorization of Western technology but also evokes a nuanced form of digital misogyny intertwined with gendered nationalism. It not only underscores the bolstering of domestic brands as emblematic of nationalistic superiority but also delineates a gendered hierarchy of technology usage that mirrors broader patriarchal controls and anxieties. The relegation of the iPhone to a symbol of marginalized femininity, thereby, not only challenges the cultural hegemony of Western consumerism but also leverages misogyny as a mechanism to perpetuate nationalistic narratives, positing domestic technological consumption as emblematic of both national and masculine superiority.

The prevalence of the term “舔狗(simp)”—a social epithet assigned to men who excessively indulge and accommodate women with little or no reciprocation from the latter—in the corpus offers further evidence of an undercurrent of male anxieties feeling threatened, as shown in comments like, “Simp, where is the brothel? Men should go there and show their support” and “Creating how many unemployed simps in China”. The female iPhone user, through the confluence of the “temptress” stereotype and her individual consumption behavior, is accused of ensnaring a certain male demographic. Implicitly, these “Simps” then materialize as a tangible embodiment of male trepidation—an image of masculinity stripped of its traditional characteristics and framed as deviant. This mirrors the demonization of women iPhone users, thereby creating a parallel between these manipulated male archetypes and the denigrated female consumers.

The discourse analyzed herein vividly illustrates a profound societal unrest, catalyzed by the erosion of entrenched gender norms and the growing influence of Western consumerism. This discourse is not merely a reflection of male disquietude amidst shifting gender dynamics; it embodies a pronounced expression of gendered nationalism. The financial acquiescence of men to the consumerist desires of women, notably for foreign brands such as the iPhone, is critiqued not solely as a deviation from traditional gender roles but as an affront to national fidelity. Consequently, this rhetorical strategy, which vilifies both the “舔狗(simp)” and female consumers of foreign technology, serves as a multifaceted attempt to navigate and counter the anxieties sparked by these socio-cultural transitions.

Nationalistic guise: legitimization of misogyny

Consistent with established research conclusions that hint at a conspiracy implicating all feminists being in illicit collusion with foreign enemies of the state (Peng 2020), Chinese female iPhone users are maligned with similar prejudiced assumptions. The narration expounded within some statements like, “Go to the United States to find a foreign man as a husband and live there, rather than staying in China” and “The situation with Chinese women is really concerning. Whether it’s smartphones or foreign men, they seem to lose all sense in the face of temptation and vanity”, introduces an additional layer to our analysis—the polar opposition seen in the East versus West dichotomy. These excerpts demonstrate the commenters subtly reinforcing a stereotypic caricature, specifically the archetype of the “Western man”. Implicit within these claims is the insinuation that Chinese women display an increased propensity towards “Western husbands”, thereby initiating a subtle cultural critique. When this cultural binary is examined in conjunction with the narrative paradigms established earlier around women iPhone users as “prostitutes”, it creates a portrayal of these women as unethical “traitors” to their native cultural identity, who are expected to capitulate to the lure of the West.

The complex weaving together of anti-feminist sentiment and online misogyny with strands of Chinese nationalist rhetoric present an intriguing tapestry of socio-political maneuvering. This is not merely a chronicle of gender discrimination on digital platforms; instead, it unfolds as an elaborate interplay entwining the personal prejudices against women, specifically iPhone users, with broader trajectories of nationalism and political posturing (Nagel 1998). Herein, nationalist discourses provide a stage upon which hegemonic masculinities are performed and reinforced. According to Nagel, nationalism is a sphere where gender power hierarchies are established and contested, and masculinity, especially in its most assertive and domineering forms, is celebrated. The vilification of iPhone-using Chinese women, in this narrative, becomes an acceptable, even commendable act of patriotic defense.

This intricate correlation serves to legitimize the barrage of verbal attacks aimed at female iPhone users. The anti-iPhone female user campaign, under this lens, is reconfigured as an act of nationalist defense and an emblem of loyalty to the state. The assault on the women, thus, is strategically disguised as a nationalist initiative. The fervor of such patriotism then permits, even encourages, the identification and marginalization of a “disloyal” or “deviant” minority—the female iPhone users, whose alleged immorality is thus deemed a threat to the established social order.

The observance of such discourses provocatively highlights the alleged affiliations of female iPhone users, branding them as adversaries of Chinese men and devotees of Western and, more specifically, American males. This elucidates the persisting objectification of Chinese women as proprietary entities of Chinese men; any perceived deviations from this norm render the women as “easy girls”. In an alarming parallel, female iPhone users, in an analogous manner to demonized feminists, are constructed as usurpers of that which “rightly belongs” to men (Peng 2020).

As Peng (2020) contends, anti-feminists re-engineer feminism into a “symbolic accomplice of Western, masculine invasions” (95), a position which fuels the ire of Chinese male nationals. Misogynist behaviors and attacks on women are tacitly legitimized under this discourse, portrayed as defiance towards imported commodities and new colonialism, thereby diverting the blame for social inequalities and systemic flaws onto women. Reality, however, reveals an underlying antipathy rooted in deep-seated prejudices that uphold a strict patriarchal obedience as sacrosanct. Women, under this patriarchal narrative, are perceived as societal resources. They are expected to adhere rigidly to established normative behaviors, with deviations met with stiff intolerance. The ensuing binary narrative of East versus West serves as a crucial smokescreen, legitimizing gender disparities and perpetuating misogynistic dialogues, thereby consolidating patriarchal hegemony under the charade of “nationalistic resistance”.

The echoes of gendered ideological tension noted between supporters of domestic mobile phones and female iPhone users on social media effectively mimic that teeming between anti-feminists and feminists. The female iPhone users, much like feminists, break normative constraints of property and power linked to male ownership and nationalism. This perceived defiance or rupture of the established orders leaves them, like feminists, antagonized. It’s a delicate weave of personal prejudice, gender discrimination, and national pride, underscoring the intricate interaction of gender, technology, nationalism, and misogyny in the digital era.

Conclusion

This study illuminates the intricate nexus of gender, technology, and nationalism within China’s contemporary digital framework, revealing how these dimensions coalesce to shape societal perceptions and interactions in the cyberspace. Predominantly, our exploration into the digital landscape, exemplified by platforms like Douyin, has demonstrated the profound impact of cyber-misogyny, amplified by the anonymity and expansiveness of online realms. Such cyber realms not only perpetuate traditional gender biases but interweave them with fervent nationalist sentiments, fomenting a unique socio-digital ecosystem that magnifies the potency of these ideologies.

Moreover, our analysis situates the convergence of ultra-nationalism, conservatism, and anti-feminism as a peculiarly Chinese phenomenon, where state narratives and techno-nationalist ideologies scaffold a distinctly Chinese brand of gendered nationalism. Unlike global counterparts, this ideological amalgamation in China is tightly interlinked with state-endorsed discourses, crafting digital environments that act simultaneously as battlegrounds for and incubators of these intersecting ideologies.

Methodologically, this research advances the scholarly discourse through the integration of Corpus-assisted Critical Discourse Analysis and Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis. This innovative methodological amalgamation has enabled a nuanced dissection of digital narratives, offering deep insights into how gender dynamics are negotiated within nationalist discourses on technology. This approach elucidates the digital manifestations of societal discourses, enriching our understanding of the complex interrelations between technology, gender, and nationalism.

The critical examination of Xiang’s comments and the resultant socio-digital backlash serves as a microcosm of the broader techno-nationalistic discourse in China. This instance exemplifies the negotiation of domestic and foreign technological identities against a backdrop of gender stereotypes and national pride, highlighting the role of technological discourse in both mirroring and molding societal values, anxieties, and ideologies.

Our investigation confirms the significant role of digital platforms, particularly Douyin, in both perpetuating and challenging established gender biases and nationalist ideologies. Existing research, as highlighted by Gao et al. (2023), Wang and Spronk (2023), and Zhu (2023), reveals that Douyin’s user behavior tendencies, recommendation algorithms, and the platform’s inherently addictive features foster homogeneous user interactions, leading to the predominance of echo chambers. Our study, underpinned by a critical discourse approach, further validates these observations by demonstrating how Douyin acts simultaneously as a reflector of societal sentiments and a forum for contestation. Such a mechanism underscores the intricate relationship between digital platforms and societal dynamics, highlighting the necessity for an in-depth examination of digital platforms’ impacts on social discourse and norms, especially regarding how governance structures and algorithmic determinants shape public discourse and cultural norms.

In synthesis, our study navigates the multifaceted digital terrain of contemporary China, unraveling the intricate interplay between cyber-misogyny, ultra-nationalism, anti-feminism, and techno-nationalism. By analyzing these complex dimensions through a refined methodological lens, the research not only uncovers prevalent societal discourses within digital spaces but also significantly contributes to the ongoing dialogue on gender, technology, and nationalism. Consequently, this body of work underscores the critical need for continued academic engagement with these intersections, aiming to deepen our comprehension of their implications for both societal norms and policy formulation.

Data availability

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the Supplementary files associated with the manuscript. This dataset includes comments from the ten most applauded short videos on Douyin regarding the topic “#Xiang Ligang Questions Apple 5G Fraud#”, comprising a total of 123,587 tokens. The data were collected and curated based on the methodology and criteria detailed in the manuscript.

References

Aiston J (2023) ‘Digitally Mediated Misogyny and Critical Discourse Studies: Methodological and Ethical Implications’. Mod. Lang. Open 0(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.454

Anderson KJ (2014) Modern misogyny: anti-feminism in a post-feminist era. Oxford University Press

Baker P, McEnery T (2005) A corpus-based approach to discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in UN and newspaper texts. J. Lang. Politics 4(2):192–226. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.4.2.04bak

Baker P, Gabrielatos C, Khosravinik M, Krzyżanowski M, McEnery T, Wodak R (2008) A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse Soc. 19(3):273–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926508088962

Baker P (2006) Using corpora in discourse analysis. Continuum

Banet-Weiser S, Miltner KM (2016) MasculinitySoFragile: culture, structure, and networked misogyny. Fem. Media Stud. 16(1):171–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2016.1120490

Banet-Weiser S (2018) Empowered: popular feminism and popular misogyny. Duke University Press

Barthel M, Bürkner HJ (2020) Ukraine and the big moral divide: what biased media coverage means to East European borders. Geopolitics 25(3):633–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2018.1561437

Bjork-James S (2020) Racializing misogyny: Sexuality and gender in the new online white nationalism. Feminist Anthropol. 1(2):176–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/fea2.12011

Boyle K (2005) Media and violence. Sage

Bracewell L (2021) Gender, populism, and the qanon conspiracy movement. Front Sociol 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.615727

Bratich J, Banet-Weiser S (2019) From pick-up artists to incels: Con(fidence) games, networked misogyny, and the failure of neoliberalism. Int. J. Commun. 13(25):5003–5027

Cheng Y (2011) From campus racism to cyber racism: Discourse of race and Chinese nationalism. China Q. 207:561–579

Cheng L, (2015) “Making of the iPhone,” https://u.osu.edu/iphone/fsdfsdff/. Accessed Feb. 22, 2024

Christina S (2012) Repudiating feminism: young women in a neoliberal world

Connell R (2005) Masculinities, 2nd edn. University of California Press

D’Attorre A (2019) Class struggle and populism: ties, transfigurations, tensions. Soft Power 6(1):120–136. https://doi.org/10.14718/softpower.2019.6.1.6

Deckman M, Cassese E (2021) Gendered nationalism and the 2016 US presidential election: How party, class, and beliefs about masculinity shaped voting behavior. Politics Gend. 17(2):277–300

Dickel V, Evolvi G (2022) “Victims of feminism”: exploring networked misogyny and #MeToo in the manosphere. Feminist Media Stud. 23(4):1392–1408. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2022.2029925

Enloe C (1989) Bananas, Beaches, and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

Fairclough N (2003) Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. London: Routledge