Abstract

Effective leaders increase organizational success. The Leadership Efficacy Model suggests that leaders’ efficacy increases when leaders are perceived as congruent; that is, when employees perceive the leader to do (practical cycle of leadership) what s/he says will (conceptual cycle of leadership) and there is a close match between what employees expect from leaders and what leaders display. This recent theoretical framework also acknowledges that a number of factors can interfere with the relationship between leadership cycle congruence and leadership efficacy. Such antecedent factors include group members’ characteristics (e.g., organizational seniority). This study aimed to test the assumption that leadership cycles congruence positively predicts leadership efficacy (measured by organizational commitment and job satisfaction, and that this relationship is moderated by employees’ seniority. 318 employees (55% male, with an average seniority of 8 years) completed a questionnaire assessing leadership cycles, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction. Path analysis results showed that the higher leadership cycles congruence, the higher employees’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Furthermore, the relationship between leadership cycle congruence and organizational commitment was stronger for more senior members of the organization (but not for job satisfaction). The results highlight the importance of leaders act in a congruent manner with their ideas and of meeting employees’ needs. Moreover, it shows that senior members of the organization are particularly sensitive to leadership congruency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Leadership is key for organizational efficacy and success (Hogan and Kaiser, 2005; Kaiser et al., 2008) and has been consensually defined as the process that aims to influence employees to achieve organizational goals (Voon et al., 2010). From a strategic and effective point of view, leadership enables organizations to increase their productivity, profit and, subsequently, achieve a competitive advantage (Yahaya and Ebrahim, 2016). Leaders are primarily responsible for the organizations they represent, and their role involves conveying to employees the need to work towards a common goal (Hogan and Kaiser, 2005). Thus, leadership efficacy can be conceptualized as the collective efficacy that results from the process of leading; in other words, that results from the dyad of leaders and followers’ behaviors, and can be operationalized by a wide range of individual, group and organizational level outcomes (cf. Hannah et al., 2008 for a review). For example, previous studies point out that leaders facilitate increased employee organizational commitment (e.g., Sedrine et al., 2020; Yahaya and Ebrahim, 2016) and job satisfaction (e.g., Kelloway and Gilbert, 2017; Yukl, 2008), and influence employees toward achieving organizational goals (Chaturvedi et al., 2019).

These data from the literature suggests that leadership efficacy can be translated through the impact of the leader’s actions on employees’ behaviors (e.g., Kaiser et al., 2008). However, employees’ expectations about their leader, which may arise for different reasons (e.g., previous work experience), may have an impact on leadership efficacy (Fu and Cheng, 2014; McDermott et al., 2013). For example, Baccili (2001) in a qualitative study found that employees expect congruency between what the leader says and what the leader does, and when employees perceive lack of congruence they manifest lower work engagement (Jabeen et al., 2015). Therefore, to comprehensively understand the leadership process and its impact on employees, it is important to consider the congruence between the leader’s words and actions, and between the leader’s actions and what the employee wants. This assumption is precisely the rationale of the Leadership Efficacy Model (Gomes, 2014, 2020), which suggests that the closer the relationship between what the leader think to do (conceptual cycle of leadership) and what the leader does (practical cycle of leadership), from both the subjective perspectives of leaders and employees, the greater the leadership efficacy (Gomes, 2014). Moreover, the model assumes that a number of factors related to behaviors assumed by leaders (leadership styles) and characteristics of leaders, members and context influence (antecedent factors of leadership) moderate the relationship between leadership cycles congruence and leadership efficacy. In other words, leaders can increase efficacy if they assume congruent cycles of leadership and if they use positive behaviors to implement the leadership cycles and if they consider the antecedent factors of leadership.

So far, and to the extent of our knowledge, only two studies have empirically tested the Leadership Efficacy Model (cf. Alves et al., 2021; Gomes et al., 2022). Both studies were conducted in a sports setting and showed that leadership cycle congruence positively predicts leadership efficacy. Moreover, Gomes and colleagues (2022) was the first study to also test the role of specific leadership styles (leadership behaviors) and antecedent factors of leadership as facilitators of leadership efficacy. However, this study did not separate the role of leaders, members and context characteristics of antecedent factors of leadership, but computed an overall favorability index, which does not allow to understand the specific role of each variable. Thus, in the present study we aim to expand previous literature by (1) considering the application of the Leadership Efficacy Model in an organizational context and whether leadership cycles congruence is a predictor of important outcomes for organizations, as is the case of commitment and job satisfaction; and (2) by testing the moderating role of group members’ characteristics which, to the extent of our knowledge, is yet to be done. This is important because the moderating role of such factors is a key assumption of the model. In this study, the group members’ (employees) characteristics included was their seniority within the organization. Employees’ seniority was chosen as the member characteristic to be analyzed (i.e., antecedent factor) because previous literature (e.g., English et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2018; Zeng et al., 2020) has shown that employees’ perceptions, evaluations and beliefs about the organization (e.g., organizational commitment and job satisfaction) are shaped by how long they have been in the organization.

Leadership efficacy model

The Leadership Efficacy Model (Gomes, 2014, 2020) was developed as a comprehensive framework that defines different sets of factors that influence leadership efficacy. In a nutshell, this theoretical approach states that leadership efficacy increases if leaders establish linear relations between how they intend to exert leadership (conceptual cycle of leadership) and how they really implement the leadership (practical cycle of leadership), i.e., if there is leadership congruence. Moreover, the model combines Trait, Behavioral and Contingency Leadership Theories to argue that this relationship between leadership congruence and efficacy will be either facilitated or debilitated (i.e., moderated) by the leadership styles adopted and by the antecedent factors (namely leader characteristics, member characteristics, and context characteristics). In this study, the main aim was to test the relationship between leadership congruence and leadership efficacy (measured by organizational commitment and job satisfaction), and the moderating effect of members’ characteristics (measured by employees’ seniority).

The main innovation of the Leadership Efficacy Model is its focus on the congruence of the leadership cycles and leadership efficacy, advocating that the leader’s activity has a dynamic nature, i.e., an influence process that is built over time and not a static phenomenon (Gomes, 2014, 2020). In this sense, it is suggested that leading without a congruence of leadership cycles should be the basis for the leader’s activity; thus, acting by trial and error is less effective and productive for all the involved in the leadership phenomenon (Gomes, 2014). Therefore, the Leadership Efficacy Model emphasizes the importance of leaders establishing linear relationship between what is important to them (leadership philosophy), the behaviors they assume to achieve the objectives (leadership practice) and the definition of strategies to evaluate the achievement of their ideas and objectives with the group members (leadership criteria) (Gomes, 2014, 2020). These linear relationships occur in two interdependent leadership cycles, the conceptual and the practical. The conceptual cycle includes the beliefs of leaders and employees about how leadership should be organized in terms of philosophy, practice, and criteria. The practical cycle incudes the beliefs of leaders and employees about how leadership occurs in real contexts, in terms of philosophy, practice, and criteria. Thus, this model advocates that the closer the cycles are to each other, the greater the leadership efficacy will be (Gomes, 2020).

The conceptual cycle of leadership occurs through three distinct domains: leadership philosophy, leadership practice, and leadership criteria (Gomes, 2020). Leadership philosophy refers to the values, beliefs, assumptions, attitudes, principles, and priorities about what leadership is and how leadership should be assumed (Gomes, 2014). In other words, the leadership philosophy can be seen as the beliefs that the leader has about the influence on group members, reflected in a set of mental representations of how to exert the role of the leader. The leadership practice is characterized by the behaviors and actions that the leader considers most appropriate to implement the philosophy of leadership, such as, for example, assuming maximum effort in performing the tasks or represents a role model for the group members. Finally, leadership criteria correspond to the leader’s mental representations of the indicators which can be used to evaluate if the leadership philosophy and the practice are producing the desired effects. For example, leaders can use criteria as the number of goals achieved or number of tasks performed with maximum quality as indicators of success produced by the philosophy and practice of leadership.

On the other hand, the practical cycle consists of the application of the conceptual cycle in daily life, both by the leader and the group members (Gomes, 2020). This cycle is characterized by the mental representations of the leader and the group members about what the leader is really doing in each specific situation, and also includes the same three domains: leadership philosophy, leadership in practice and leadership criteria. The processes start when the leaders transmit their ideas and principles (leadership philosophy), how to achieve the leadership philosophy (leadership in practice), and how to evaluate it (leadership criteria). This sharing may take place in a more formal way (e.g., work meetings) or in an informal way (e.g., daily contact between the leader and the group members) (Gomes, 2020). Since this cycle is the operationalization of the conceptual cycle, it means that it begins when both the leader and the group members assume the behaviors to achieve the principles defined by the leader and accepted by the members (Gomes, 2020). To this extent, leadership cycles congruence also implies that leaders’ activity matches employees’ expectations and needs (i.e., how they think leaders should exert leadership).

According to the model, the characteristics of the leader, of the group members, and of the situation assume a status of moderating variable between the congruency of the two cycles and leadership efficacy, being named antecedent factors of leadership (Gomes, 2020). This means that the leader should take these antecedent factors of leadership into account when establishing the leadership cycles, since they can maximize or inhibit their actions. For example, regarding the characteristics of the group members, leaders should consider a wide number of factors, as is the case of professional (e.g., objectives, hierarchical level), demographic (e.g., seniority), and psychological (e.g., self-confidence) variables, because the closer they act according to these characteristics, the more likely their action will be effective (Gomes and Resende, 2015).

In sum, the Leadership Efficacy Model proposes that higher levels of congruency between the practical and conceptual cycles of leadership augments the leadership efficacy. Moreover, the model proposes that characteristics of the group members influence the relationship between leadership cycles and leadership efficacy. In our study, we selected organizational commitment and job satisfaction as indicators of leadership efficacy and seniority as moderator of the influence produced by leadership congruency in organizational commitment and job satisfaction.

H1 and H2. Leadership efficacy: organizational commitment and job satisfaction

Leadership efficacy can be understood as the multiple impacts produced by the leader on others, as is the case of employee satisfaction, motivation, and organizational outcomes (Kaiser et al., 2008; Malik, 2013; Voon et al., 2010). Therefore, it can be measured in a variety of ways (e.g., Andrews et al., 2006; Kaiser et al., 2008; Kanji, 2008). A diversity of evaluation measures is important to overcome possible biases, as a single organizational outcome (e.g., productivity measure, financial performance, turnover) does not provide a complete overview (Kaiser et al., 2008; Scullen et al., 2000). As an influence process, leaders’ behaviors affect employees’ attitudes towards work, such as the organizational commitment, work engagement, and job satisfaction (Rehman et al., 2020; Saleem, 2015; Voon et al., 2010). Specifically, organizational commitment and job satisfaction are relevant variables to the organizational context, as they have been associated with lower absenteeism and turnover, higher motivation, leadership satisfaction, and increases in organizational citizenship behaviors (e.g., Gatling et al., 2016; Hanaysha, 2016; Joo and Park, 2010; Malik, 2013). For these reasons, we selected organizational commitment and job satisfaction as indicators of leadership efficacy, as they represent key variables in organizational contexts and because they can represent different constructs of human experience at work, one more related to how the individual feel about the work activity (job satisfaction) and another more related to how the individual feel about the organization (organizational commitment).

Organizational commitment is defined as a force that stimulates the individual’s involvement and identification with an organization, the willingness to put effort and dedication in achieving organizational goals, as well as the desire to remain in the organization (Porter et al., 1974). Therefore, it is seen as a significant factor in determining employee behavior (Meyer et al., 2002; Yahaya and Ebrahim, 2016). Specifically, organizational commitment is perceived as an emotional attachment of the employee to the organization (Ćulibrk et al., 2018; Meyer et al., 2004), where individuals identify with the values and mission and enjoy being part of the organization (Hanaysha, 2016; Meyer and Allen, 1991; Pradhan and Pradhan, 2015). Employees who report high levels of commitment exhibit aspirations to contribute meaningfully to the organization and a greater willingness to make sacrifices for it and, at the same time, report fewer intentions to leave or resign and tend to feel more satisfied with their work and have higher intrinsic motivation (cf. Ćulibrk et al., 2018; Hanaysha, 2016).

Mathieu and colleagues (2016) state that the popular adage “Employees don’t quit their companies, they quit their boss” has been empirically proven, enhancing the importance and influence of the leader’s role in the willingness of employees to remain in the organization. In this sense, there are several studies exploring the relationship between employees’ perceptions of the leaders’ actions on their organizational commitment (Gatling et al., 2016; Sedrine et al., 2020; Yahaya and Ebrahim, 2016). For example, Pradhan and Pradhan (2015) reported that leaders who demonstrate attentiveness to employees’ personal and professional development, positively influence employee commitment because this demonstration leads to an emotional attachment to the leader and the organization. Additionally, Sedrine and colleagues (2020), concluded that leaders who seek to involve employees in decision making inspire greater trust and job satisfaction and have a positive impact on organizational commitment. On the other hand, these authors reported that supervision by the leader has an adverse effect on employees’ attitude, reducing their commitment to the organization. This effect is justified by the control of autonomy, feeling of lack of trust and disrespect felt by employees, translated by a low level of commitment (Sedrine et al., 2020). Overall, these different findings support the idea that the behaviors adopted by the leader are significantly related to employees’ organizational commitment (cf. Yiing and Ahmad, 2009). Similarly, we argue that leadership cycles congruence (i.e., leaders’ words and actions are aligned) feeds a positive relationship between leader and employees. By being congruent in their words and actions, leaders display trustworthiness and assure employees they can trust them and, therefore, increase their commitment with the organization.

H1: Perceived leadership cycles congruence positively predicts employees’ organizational commitment. The higher the perceived congruence, the higher the organizational commitment.

One of the major challenges for leaders is to ensure the job satisfaction of their employees (Asghar and Oino, 2018), making it pertinent to understand this construct. Job satisfaction is defined as “the attitudes and feelings people have about their work”, and the more satisfied employees are, the more positive their attitudes will be (Armstrong, 2006, p. 474). Satisfaction levels can be affected intrinsically, depending for example, on the self-esteem of the group members, or extrinsically, considering, for example, the context or the quantity and quality of the leader’s supervision (Armstrong, 2006; Malik, 2013).

The existence of a relationship between employees’ job satisfaction and satisfaction with their leaders is described in the literature (Elshout et al., 2013; Tsai, 2011). In fact, job satisfaction has been associated with leaders who manifest behaviors of inspiration, motivation, concern, and respect for employees (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012; Saleem, 2015). Furthermore, it is suggested that the leader’s behaviors of encouraging and supporting employees, as well as their confidence and clear vision can relate to employee job satisfaction (Tsai, 2011). These behaviors, mostly associated with transformational and transactional styles of leadership, are a reflection of how leaders (practical cycle of leadership) act or, in other words, how leaders can exert their influence and increase the congruence between cycles of leadership. Moreover, Alves and colleagues (2021), who conducted a study based on the Leadership Efficacy Model in a sport context, also found that leadership cycles congruence is associated with satisfaction with leaders. Overall, how employees perceive their leaders is a decisive factor in their overall satisfaction (Hogan and Kaiser, 2005). We argue that by perceiving the leader as being congruent with their words (conceptual cycle of leadership) and daily actions (practical cycle of leadership), employees develop a positive image and relationship with the leader which, in turn, leaders to higher job satisfaction. Therefore, we expect that:

H2: Perceived leadership cycles congruence positively predicts employees’ job satisfaction. The higher the perceived congruence of the leader’s cycles, the higher the job satisfaction.

H3. Antecedent factors of leadership: the moderating role of seniority

The actions of leaders do not occur in isolation, depending on some factors that can help to understand the multiple impacts produced by leadership. According to the Leadership Efficacy Model there are three antecedent factors of leadership that can influence the impacts of leadership cycles congruence in leadership efficacy: the personal and professional characteristics of the leader, the personal and professional characteristics of team members, and the specific conditions provided by the organization under which the leader is working (Gomes, 2020). These factors influence the relationship between leadership cycles (e.g., how leaders intend to assume leadership and how leaders assume leadership) and leadership efficacy. Seniority is an example of these factors since employees’ perceptions and evaluations change depending on how long they have been with the organization (English et al., 2010; Wright and Bonett, 2002). The literature highlights the relationship between seniority and commitment (Akinyemi, 2014; Hong et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2018) and seniority and job satisfaction (Lian and Ling, 2018; Zeng et al., 2020), but there is less knowledge about the moderating effect of seniority on the relationship between how leadership is exerted (e.g., leadership cycles congruence) and leadership efficacy.

Previous research has established that employees’ beliefs regarding the organization vary according to the length of service in the organization (e.g., Low et al., 2016), which is also reflected on the psychological contract they hold regarding the organization (cf. Bal et al., 2013). Specifically, Bal and colleagues (2013) found a relationship between the fulfillment of the psychological contract and greater involvement at work by the employee but only for employees with less seniority. According to these authors, this is because employees with less seniority value the norms of reciprocity more highly. On the other hand, employees’ seniority also has implications on the impact of the violation of the psychological contract, as employees respond differently to employers’ non-fulfillment of obligations (cf. Sharif et al., 2017; Priesemuth and Taylor, 2016). Specifically, more recent employees have higher expectations about the employers when they first join the organization and, the longer they stay, the more they adjust these expectation—therefore, the higher their seniority, the lower employees’ perceptions of employer’s obligations (Payne et al., 2015).

In sum, the beliefs and expectations that employees hold about the organizations and their leaders influence the aspects they pay attention to, that they value, their interpretations, and reactions (Rousseau, 2001, Rousseau et al., 2018). According to the aforementioned literature review, employees with lower seniority are more tend to value more the reciprocity between themselves and the organization and to hold higher expectations of the organization. Additionally, the non-fulfilment of expectations has a greater influence on their behaviors and attitudes, compared to employees with greater seniority. For that reason, we argue that employees with lower seniority are more aware and sensitive of their leader’s behaviors. Therefore, and based on the Leadership Efficacy Model (Gomes, 2014, 2020), we expect that if leaders display low congruency, this would affect more negatively employees with lower seniority. Thus, we established the third hypothesis for this study:

H3: Seniority has a moderating effect on the relationship between leadership cycles congruence and leadership efficacy (measured by organizational commitment and job satisfaction). Specifically, it is expected that less seniority amplifies the positive relationship of leadership cycles congruence with (H3a) organizational commitment and (H3b) job satisfaction.

Methods

Data collection procedure

As aforementioned, the main aim of this study was to test the relationship between leadership congruence and leadership efficacy (i.e., organizational commitment and job satisfaction), as well as the moderating role of members’ characteristics (i.e., seniority). In order to test this conceptual model, a correlational study was conducted with employees from different organizations who evaluated their leaders. The first step consisted of obtaining approval from the Ethics Committee from the fourth authors’ University. Once approval was obtained [cf. Ethical Statement], the research team created the questionnaire on Qualtrics® platform and a link for dissemination was generated using the same software. A multiple-source approach was used to recruit participants: specifically, the questionnaire was disseminated on online platforms (LinkedIn, Facebook; 38%) and through six organizations from different sectors which were part of the research teams’ network (public administration: 25%, technology: 18%, automotive: 9%, catering: 5%, healthcare: 5%) and who agreed to distribute the study among their employees.

When participants accessed to the questionnaire, a first page with the informed consent, and explaining the study goals and procedure was displayed. Once they agreed to participate in the study, an initial screening question was used to exclude any participants who did not directly report to a leader. If they met this inclusion criteria (having a leader in their organization to whom they report directly), several demographic questions were asked and then they completed the measures regarding leadership congruency, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction. The order of the items and measures was randomized. Completing the whole research protocol took them, on average, about 25 min. The data was collected between February and April 2021.

Participants

A sample of 318 employees (55% male) was considered in the study. Their aged ranged from 21 to 72 years-old (M = 35.78, SD = 10.54). Most participants held a bachelor’s degree (38%) or a master’s degree or higher (30%), and 27% completed high school.

Participants worked in a wide range of sectors: service industry (22%), health and social care (17%), public administration and defense (17%), manufacturing (8%), administrative activities (7%), education (5%), retail (5%), IT and communication (3%), finance (2%), hospitality (2%), among others (12%). The majority of participants were full-time employees (97%) with permanent employment contract (60%). Regarding participants’ seniority within the organization, it ranged from 1month to 42 years (M = 8 years, SD = 9.5 years).

Measures

Leadership congruency

The Leadership Efficacy Questionnaire (LEQ; Gomes et al., 2022) was used to assess the congruency of leadership cycles (conceptual and practical cycles). This measure evaluates three different dimensions: (1) leadership philosophy (5 items, e.g., “My leader tells us the ideas s/he values the most”, αconceptual = 0.87, αpractical = 0.91), (2) leadership practice (5 items, e.g., “My leader acts in accordance with the ideas valued”, αconceptual = 0.89, αpractical = 0.92), and leadership criteria (5 items, e.g., “My leader evaluates if what is done is in accordance with what we wanted to achieve”, αconceptual = 0.89, αpractical = 0.93). A score for each dimension was calculated by averaging participants’ responses (1 = never; 5 = always). For each of the 15 statements, employees answered twice: once regarding their leader’s preferred behaviors (leadership philosophy, practice, and criteria at the conceptual cycle), and another referring to their leader’s current behaviors (leadership philosophy, practice, and criteria at the practical cycle). A final score of leadership congruency was calculated by subtracting participants’ responses in the conceptual cycle from the practical cycle, and negative numbers were mirrored, so the final variable would only include positive numbers. Therefore, values closer to 0 indicate higher congruency between current and preferred leadership behaviors, creating a new variable named the Leadership Cycles Congruence Index (LCCI).

Organizational commitment

Participants’ organizational commitment was assessed using the Organizational Commitment Scale (Conley and Woosley, 2000; Mowday et al., 1982; Portuguese translation by Gomes, 2007). Using a likert scale (1 = completely disagree; 5 = completely agree), participants rated their agreement with nine statements (e.g., “I am proud to tell other people that I am part of this organization”, α = 0.91). A score of organizational commitment was computed by averaging participants’ responses.

Job satisfaction

Employees’ perceptions regarding their job satisfaction were evaluated using the Portuguese version of the Job Satisfaction Questionnaire (Meliá and Peiró, 1989; Pocinho and Garcia, 2008). Participants were asked to rate their satisfaction (1 = not satisfied at all, 7 = extremely satisfied) to 23 different aspects of their work (e.g., “I am happy about my career progression opportunities”, α = 0.96). Their responses were averaged to create a job satisfaction score.

Data analyses procedure

An a-priori sample size calculator was used to determine the minimum sample required. For a medium effect size of 0.20 and a desired power level of 0.80 (at a probability level of 0.05), a minimum of 223 participants were recommended (cf. Soper, 2022). The study sample met this requirement.

Then, the first step consisted of verifying the statistical assumptions of normality and multicollinearity for the four variables of the study: perceptions of leadership congruency, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction, as well as participants’ seniority within their organizations. The normality assumption was tested using Kline’s (2015) criteria of skewness ≤|3| and kurtosis ≤ |10|. The multicollinearity assumption was checked based on the correlations among variables (which should be <0.80) and VIF (which should be <5) (cf. Marôco, 2014).

Path analysis using AMOS Software ® was conducted so the full model could be tested simultaneously. Therefore, perceptions of leadership congruency were included as a predictor, and organizational commitment and job satisfaction as outcomes (H1 and H2). To test the moderating role of seniority (H3a and H3b), the interaction between perceptions of leadership congruency and seniority was calculated and inserted in the model as a predictor. All predictor variables (leadership congruency, seniority, interaction leadership congruency x seniority) were first standardized using z-scores, as they used different unity measures.

The quality of the theoretical model was evaluated using the following criteria: (a) chi-square statistics (χ2); (b) Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1990), so that adequate fit concluded for values between 0.05 and 0.08, and good fit when below 0.05 (cf. Arbuckle, 2008); (c) Standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), considering a good fit was achieved when below 0.10 (cf. Kline, 2015); (d) Goodness of Fit (GFI) and Comparative fit index (CFI), for which values above 0.95 indicated a good fit (cf. Bentler, 1990; 2007; Marôco, 2014).

Results

Descriptive statistics and preliminary analysis

Regarding normality assumptions, Using Kline’s (2015) criteria of skewness ≤|3| and kurtosis ≤|10 | , there were no severe deviations from normality found in the data (−0.65 > sk < 1.39; 0.26 > ku < 1.30). Thus, parametric tests were conducted to test the study hypotheses (cf. Kline, 2015).

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the study variables (participants’ seniority and perceptions of leadership congruency, organizational commitment and job satisfaction), as well as the two-tailed correlations among them. The higher the participants’ seniority, the less leadership congruency (numbers closer to 0) and the lower the job satisfaction (and vice-versa) they tend to perceive. On the other hand, the more congruency they perceive, the higher the organizational commitment and job satisfaction. The latter variables are also highly correlated. No correlations were above 0.80 and all VIF coefficients ranged from 1.02 to 1.99—therefore, the non-multicollinearity assumption was met.

Path analysis (H1, H2, H3)

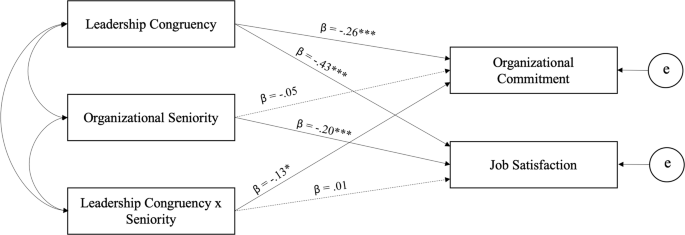

The proposed model (cf. Fig. 1) was tested using path analysis. The results show that it is a good fit to the data: χ2(1) = 5.96, χ2/df = 5.96, RMSEA = 0.125, 95% CI [0.044, 0.230], pRMSEA = 0.061, SRMR = 0.039, GFI = 0.993, CFI = 0.980. A summary of the parameter estimates can be found in Table 2. It can be concluded that higher perceptions of leadership congruency predict higher organizational commitment and job satisfaction, thus confirming H1 and H2. On the other hand, the longer participants are enrolled in a particular organization (seniority), the lower their job satisfaction, but not their organizational commitment. The leadership congruency x seniority interaction is a predictor of organizational commitment but not job satisfaction (therefore, H3b was not supported). The overall model explained 22% of the variance of participants’ job satisfaction and 10% of the variance of their organizational commitment.

A closer look at this latter interaction was conducted by splitting the sample into high vs. low seniority and conducting separate regression analyses. The criteria used to compute the two groups was based on previous literature that used 60 months (5 years) as a cut-off point to decide whether an employee would be considered to have a stable tenure with the organization or not (cf. Bal et al., 2013; Boswell et al., 2005). Thus, following the same criteria, participants were split into high seniority (≥60 months; n = 150) and low seniority (<60 months; n = 168). The results indicated that leadership congruency predicts organizational commitment for more senior members of the organization [F (1,147) = 30.85, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.174, b = −0.42, β = −0.42, t = −5.55, p < 0.001] but not for younger members of the staff [F (1,167) = 2.56, p = 0.111]. Even though the interaction for organizational commitment was significant, its direction does not support H3a.

Discussion

This study aimed to test the relationship between leadership cycle congruence and leadership efficacy in an organizational setting, considering the analysis of the moderating influence of seniority. This analysis was done by assuming the predictions of the Leadership Efficacy Model (Gomes, 2014, 2020). The results supported the main proposition of the model that congruence between leadership cycles explains higher levels of organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Equally important, our study tested if antecedent factors of leadership can either exacerbate or minimize the influence of leadership cycle congruence on leadership efficacy. The results showed that leadership cycle congruency is a positive predictor of organizational commitment for more senior members of the organization. However, seniority did not moderate the relationship between leadership cycle congruency and job satisfaction.

As aforementioned, the Leadership Efficacy Model (Gomes 2014, 2020) states that higher leadership cycle congruency predicts leadership efficacy. This assumption was corroborated by the study. As expected, when employees perceived higher congruency between conceptual and practical cycles of leadership, they displayed stronger organizational commitment (H1) and job satisfaction (H2). These results support the main theoretical assumption of the Leadership Efficacy Model and are consistent with previous literature that tested this theoretical framework in a sports context, showing that higher congruency in leadership cycles predicted higher satisfaction with leader and perceptions of team performance (Alves et al., 2021; Gomes et al., 2022). Thus, the results support the idea that when leaders’ daily actions (practical cycle of leadership) are congruent with employees’ desires/needs (conceptual cycle of leadership), it increases leadership efficacy—in our case, it increases employees’ commitment towards the organization and their job satisfaction.

The third hypothesis of the study predicted that seniority would moderate the relationship between the congruence of leadership cycles congruence and leadership efficacy. Specifically, it was expected that less seniority would amplify the positive relationship leadership between efficacy and organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Previous literature (e.g., English et al., 2010; Low et al., 2016; Phungsoonthorn and Charoensukmongkol, 2018) has already established that employees’ perceptions and evaluations regarding the organization change over time. Specifically, research suggests that employees with lower seniority attribute more value to the norms of reciprocity between themselves and the organization and, therefore, the fulfillment or not of the established expectations and their involvement in the work is particularly important to these employees (cf. Bal et al., 2013). This idea was supported by Payne and colleagues (2015), who argued that when someone first joins the organization, they have higher expectations, which are adjusted and, therefore, decrease, over time. Moreover, based on previous research that showed that staff with lower seniority is more aware of leaders’ behaviors (e.g., Rousseau et al., 2018), seniority was expected to moderate the relationship between leadership cycles congruence and efficacy in such a way that it would be amplified for less senior members of staff.

However, even though the results show a significant interaction of Leadership Cycles Congruence x Seniority on employees’ organizational commitment, the relationship between the predictor and the outcome is only significant for senior members of the staff. In other words, the results showed that leadership congruency only predicts organizational commitment for senior members of the organization, but not for younger members of the staff, contradicting H3a. No interaction was found for job satisfaction, and, therefore, H3b was also not supported. According to Payne and colleagues (2015), employees’ expectations adjust over time, with employees’ perceptions of employer obligations significantly decreasing over the years in the organization. Taking this into consideration, one possible justification is that if the non-fulfillment of expectations has a lower influence on more senior members of the organization (cf. Rousseau et al., 2018), when a leader fulfills their needs, and shows stronger congruence between their statements (conceptual cycle) and actions (practical cycle) it exceeds their expectations and, therefore, has a more positive impact. An alternative explanation is related to the fact that data was collected during the COVID19 pandemic, which was a time in which leaders were particularly important (cf. Eichenauer et al., 2022) in keeping stability and facilitating employees’ work-life balance, which are important features for more senior employees and what they value in the relationship they established with the organization (cf. Low et al., 2016).

Limitations and future research

Considering the particular circumstances in which data for this study was collected, future research should aim to test whether these results are stable once the pandemic is over, assuring its replicability. It is also important to note that, even though appropriate to the aims of this particular study, cross-sectional designs encompass a number of limitations. One of those limitations, especially when testing relationships between variables, refers to the common method variance, which is drawn from the fact that the same participants answered both predictor and outcome variables at the same moment. However, this issue was addressed during data collection: an online platform was used to collect data, and the order of items and measures was randomized (cf. Chang et al., 2010). An alternative methodological approach would be to partner with an organization to conduct a longitudinal study. This approach would allow (1) to infer the duration of the impact of leadership cycles congruence on efficacy; and (2) the use of objective efficacy measures (e.g., turnover rate, absenteeism), which are important to provide a more comprehensive understanding of leadership efficacy (cf. Gomes, 2014; Gomes and Resende, 2015). Moreover, even though the present study tested the main assumption of Leadership Efficacy Model (regarding leadership congruence) and tested the moderating role of an antecedent factors of leadership, other variables included in the theoretical model should be included in future research (namely, the leadership styles, and antecedent factors of leadership regarding the leader’s and the situation’s characteristics).

Conclusion and practical implications

Overall, the study results provide support for the Leadership Efficacy Model, showing that leadership cycles congruence increases leadership efficacy (in this case, job satisfaction and organizational commitment), and that antecedent factors of leadership such as group members’ characteristics (namely seniority) can act as moderators of this relationship. Thus, this study results provide empirical support to two key assumptions of this theoretical framework and is, to the extent of our knowledge, the first study to test the Leadership Efficacy Model in an organizational setting. Taken together, the results have important implications for practice, specifically in organizational contexts. First, they show that in order to maximize the efficacy of their leadership, leaders must make clear to employees their conceptual cycle. In other words, leaders need to state what they want and value in their teams (leadership philosophy), how they want those values to be implemented (leadership practice), and which indicators should be used to assess its implementation (leadership criteria). At the same time, leaders need to ensure that this is in line with what they do on a daily basis (practical cycle of leadership); that is, that the leadership they exert is close to what they conceptualize and that it considers the preferences and needs of their teams.

A second important implication refers to the role of the employee’s seniority in perceiving the leader’s actions. How employees perceive and assess the leader depends on how long they are at the organization, which is consistent with the idea that employees look for different things in the organization and, consequently, in their leaders over time. Therefore, the influence of leadership cycle congruence on the relationship employees establish in the organization varies according to seniority. In this study, it showed that the influence of leadership cycles congruence on employees’ organizational commitment was stronger for employees with a longer tenure, when compared to newer members of staff. Thus, the study highlights the importance of leaders being sensitive to the characteristics of their members and to their needs in order to adjust their actions to remain effective.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Akinyemi BO (2014) Organizational commitment in Nigerian banks: the influence of age, tenure and education. J Mgmt Sustain 4:104–115. https://doi.org/10.5539/jms.v4n4p104

Alves J, Morais C, Gomes AR, Simães C (2021) Liderança no voleibol: Relação entre filosofia, prática e indicadores de liderança. Coleção. Pesqui em Educção FíSci 20:153–161. http://hdl.handle.net/1822/70516

Andrews R, Boyne GA, Walker RM (2006) Subjective and objective measures of organizational performance. In: Boyne GA, Meier KJ O’Toole LJ Jr, Walker RM (eds). Public service performance: perspectives on measurement and management. Cambridge University Press

Arbuckle JL (2008) Amos 17.0 user’s guide. SPSS Inc

Armstrong M (2006) A handbook of human resource management practice. Kogan Page Publishers

Asghar S, Oino I (2018) Leadership styles and job satisfaction. Mark Forces 13:1–13

Baccili PA (2001) Organization and manager obligations in a framework of psychological contract development and violation. Dissertation, The Claremont Graduate University

Bal PM, De Cooman R, Mol ST (2013) Dynamics of psychological contracts with work engagement and turnover intention: the influence of organizational tenure. Eur J Work Org Psychol 22:107–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2011.626198

Bentler PM (1990) Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull 107:238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Bentler PM (2007) On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Pers Individ Dif 42:825–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.024

Boswell WR, Boudreau JW, Tichy J (2005) The relationship between employee job change and job satisfaction: the honeymoon-hangover effect. J Appl Psychol 90:882–892. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.882

Chang S, van Witteloostuijn A, Eden L (2010) From the editors: common method variance in international business research. J Int Bus Stud 41:178–184. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.88

Chaturvedi S, Rizvi IA, Pasipanodya ET (2019) How can leaders make their followers to commit to the organization? The importance of influence tactics. Glob Bus Rev 20:1462–1474. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150919846963

Conley S, Woosley SA (2000) Teacher role stress, higher order needs and outcomes. J Educ Adm 38:179–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230010320163

Ćulibrk J, Delić M, Mitrović S, Ćulibrk D (2018) Job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job involvement: the mediating role of job involvement. Front Psychol 9:132. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00132

Eichenauer CJ, Ryan AM, Alanis JM (2022) Leadership during crisis: an examination of supervisory leadership behavior and gender during COVID-19. J Leadersh Org Stud 29:190–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/15480518211010761

Elshout R, Scherp E, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM (2013) Understanding the link between leadership style, employee satisfaction, and absenteeism: a mixed methods design study in a mental health care institution. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 9:823. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S43755

English B, Morrison D, Chalon C (2010) Moderator effects of organizational tenure on the relationship between psychological climate and affective commitment. J Manag Dev 29:394–408. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711011039187

Fu CJ, Cheng CI (2014) Unfulfilled expectations and promises, and behavioral outcomes. Int J Organ Anal 22:61–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-08-2011-0505

Gatling A, Kang HJA, Kim JS (2016) The effects of authentic leadership and organizational commitment on turnover intention. Leadersh Org Dev J 37:181–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-05-2014-0090

Gomes AR (2007) Escala de comprometimento organizacional (ECO)—Versão para investigação [Published Report]. University of Minho

Gomes AR (2014) Leadership and positive human functioning: a triphasic proposal. In: Gomes AR, Resende R, Albuquerque A (eds). Positive human functioning from a multidimensional perspective: promoting high performance, pp. 157–169. http://hdl.handle.net/1822/28118

Gomes AR (2020) Coaching efficacy: the leadership efficacy model. In: Resende R, Gomes AR (eds). Coaching for human development and performance in sports. Springer, pp. 43–72

Gomes AR, Gonçalves A, Morais C et al. (2022) Leadership efficacy in youth football: Athletes and coaches’ perspective. Int Sport Coach J 9:170–178. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2020-0128

Gomes AR, Resende, R (2015) O que penso, o que faço e o que avalio: Implicações para treinadores de formação desportiva [What I think, what I do, and what I evaluate: implications for the training of coaches]. In: Molina SF, Alonso MC (eds). Innovaciones y aportaciones a la formación de entrenadores para el deporte en la edade escolar. Universidade de Extremadura, pp. 195–213. http://hdl.handle.net/1822/42224

Hanaysha J (2016) Examining the effects of employee empowerment, teamwork, and employee training on organizational commitment. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 229:298–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.140

Hannah ST, Avolio BJ, Luthans F, Harms PD (2008) Leadership efficacy: review and future directions. Leadersh Q 19:669–692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.09.007

Hogan R, Kaiser RB (2005) What we know about leadership. Rev Gen Psychol 9:169–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.169

Hong G, Cho Y, Froese FJ, Shin M (2016) The effect of leadership styles, rank, and seniority on affective organizational commitment. Cross Cult Strateg M 23:340–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783360802002834

Jabeen F, Behery M, Elanain H (2015) Examining the relationship between the psychological contract and organisational commitment. Int J Organ Anal 23:102–122. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-10-2014-0812

Joo BKB, Park S (2010) Career satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention. Leadersh Org Dev J 31:482–500. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437731011069999

Judge TA, Kammeyer-Mueller JD (2012) Job attitudes. Ann Rev Psychol 63:341–367. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100511

Kaiser RB, Hogan R, Craig SB (2008) Leadership and the fate of organizations. Am Psychol 63:96–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.2.96

Kanji GK (2008) Leadership is prime: how do you measure leadership excellence? Total Qual Manag 19:417–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783360802002834

Kelloway EK, Gilbert S (2017) Does it matter who leads us? The study of organizational leadership. In: Chmiel N, Fraccaroli F, Sverke M (eds). An introduction to work and organizational psychology, Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 192–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119168058.ch11

Kline R (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (4th edn). The Guilford Press

Lee J, Chiang FF, van Esch E, Cai Z (2018) Why and when organizational culture fosters affective commitment among knowledge workers: the mediating role of perceived psychological contract fulfilment and moderating role of organizational tenure. Int J Hum Resour Manag 29:1178–1207. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1194870

Lian JK, Ling FY (2018) The influence of personal characteristics on quantity surveyors’ job satisfaction. Built Environ Proj Asset Manag 8:183–193. https://doi.org/10.1108/bepam-12-2017-0117

Low CH, Bordia P, Bordia S (2016) What do employees want and why? An exploration of employees preferred psychological contract elements across career stages. Hum Relat 69:1457–1481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715616468

Malik SH (2013) Relationship between leader behaviors and employees’ job satisfaction: a path-goal approach. Pak J Commer Soc Sci 7:209–222. https://doaj.org/article/de6199f4bb404b5d80bcc2ca38077db4

Marôco J (2014) Análise de equações estruturais: fundamentos teóricos, software & aplicações [Structural equation modelling analysis: theoretical assumptions, software & applications] (2nd edn), Report number

Mathieu C, Fabi B, Lacoursiere R, Raymond L (2016) The role of supervisory behavior, job satisfaction and organizational commitment on employee turnover. J Manag Org 22:113–129. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2015.25

McDermott AM, Heffernan M, Beynon MJ (2013) When the nature of employment matters in the employment relationship: a cluster analysis of psychological contracts and organizational commitment in the non-profit sector. Int J Hum Resour Manag 24:1490–1518. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.723635

Meliá JL, Peiró JM (1989) El custionario de satisfacción S10/12: estructura factorial, fiabilidade y validez. Rev Psicol Trab Org 4:179–187

Meyer JP, Allen NJ (1991) A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum Resour Manag Rev 1:61–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

Meyer JP, Becker TE, Vandenberghe C (2004) Employee commitment and motivation: a conceptual analysis and integrative model. J Appl Psychol 89:991–1007. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.6.991

Meyer JP, Stanley DJ, Herscovitch L, Topolnytsky L (2002) Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J Vocat Behav 61:20–52. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

Mowday RT, Porter LW, Steers RM (1982) Employee-organization linkages: the psychology of commitment, absenteeism, and turnover. Academic Press

Payne SC, Culbertson SS, Lopez YP et al. (2015) Contract breach as a trigger for adjustment to the psychological contract during the first year of employment. J Occup Organ Psychol 88:41–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12077

Phungsoonthorn T, Charoensukmongkol P (2018) The preventive role of transformational leadership and trust in the leader on employee turnover risk of Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand: The moderating role of salary and job tenure. J Risk Manag Insur 22:63–79

Pocinho M, Garcia J (2008) Impacto psicossocial de la Tecnología de Información e Comunicación (TIC): tecnoestrés, daños físicos y satisfacción laboral. Acta Colomb Psicol 11:127–139

Porter LW, Steers RM, Mowday RT (1974) Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J Appl Psychol 59:603–609

Pradhan S, Pradhan RK (2015) An empirical investigation of relationship among transformational leadership, affective organizational commitment and contextual performance. Vis 19:227–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972262915597089

Priesemuth M, Taylor RM (2016) The more I want, the less I have left to give: the moderating role of psychological entitlement on the relationship between psychological contract violation, depressive mood states, and citizenship behavior. J Org Behav 37:967–982. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2080

Rehman SUR, Shahzad M, Farooq MS, Javaid MU (2020) Impact of leadership behavior of a project manager on his/her subordinate’s job-attitudes and job-outcomes. Asia Pac Manag Rev 25:38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2019.06.004

Rousseau DM (2001) Schema, promise and mutuality: the building blocks of the psychological contract. J Occup Organ Psychol 74:511–541. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317901167505

Rousseau DM, Hansen SD, Tomprou M (2018) A dynamic phase model of psychological contract processes. J Occup Organ Psychol 39:1081–1098. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2284

Saleem H (2015) The impact of leadership styles on job satisfaction and mediating role of perceived organizational politics. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 172:563–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.403

Scullen SE, Mount MK, Goff M (2000) Understanding the latent structure of job performance ratings. J Appl Psychol 85:956–970. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.6.956

Sedrine SB, Bouderbala AS, Hamdi M (2020) Distributed leadership and organizational commitment: moderating role of confidence and affective climate. Eur Bus Rev. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-04-2018-0073

Sharif I, Wahab SRA, Sarip A (2017) Psychological contract breach and feelings of violation: moderating role of age-related difference. Int J Asian Soc Sci 7:85–96. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.1/2017.7.1/1.1.85.96

Soper DS (2022) A-priori sample size calculator for structural equation models [Software]. Available from https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc

Steiger JH (1990) Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivar Behav Res 25:173–180. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4

Tsai Y (2011) Relationship between organizational culture, leadership behavior and job satisfaction. BMC Health Serv Res 11:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-98

Voon ML, Lo MC, Ngui KS, Ayob NB (2010) The influence of leadership styles on employees’ job satisfaction in public sector organizations in Malaysia. Int J Bus Manag Soc Sci 2:24–32

Wright TA, Bonett DG (2002) The moderating effects of employee tenure on the relation between organizational commitment and job performance: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol 87:1183. 10.1037//0021-9010.87.6.1183

Yahaya R, Ebrahim F (2016) Leadership styles and organizational commitment: literature review. J Manag Dev 35:190–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-01-2015-0004

Yiing LH, Ahmad KZB (2009) The moderating effects of organizational culture on the relationships between leadership behaviour and organizational commitment and between organizational commitment and job satisfaction and performance. Leadersh Org Dev J 30:53–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730910927106

Yukl G (2008) How leaders influence organizational efficacy. Leadersh Q 19:708–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.09.008

Zeng X, Zhang X, Chen M et al. (2020) The influence of perceived organizational support on police job burnout: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychol 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00948

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Ágata Faria and João Monteiro in data collection. The authors would also like to acknowledge that the study was conducted at two different research centres supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology: Research Centre for Human Development, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Universidade Católica Portuguesa (ref. UIDB/04872/2020) and the Psychology Research Centre (CIPsi/UM), School of Psychology, University of Minho (ref. UIDB/01662/2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CM was co-responsible for conceptualization, methodology, and responsible for formal analysis and supervision. FQ and SC assisted in methodology, and were responsible for data curation and collection and for writing—original draft preparation. RG was instrumental in conceptualization and methodology, as well as writing—review and editing. CS assisted in conceptualization, formal data analysis and writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee for Research in Social and Human Sciences (CEICSH) of the University of Minho [reference approval: CEICSH 128/2020]. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morais, C., Queirós, F., Couto, S. et al. Explaining organizational commitment and job satisfaction: the role of leadership and seniority. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1363 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03855-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03855-z