Abstract

This paper investigates the grammaticalization of the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ in Jordanian Arabic. The study argues that the verb has been grammaticalized into three meanings that constitute three levels on the grammaticalization pathway. These three meanings coexist i.e. are not considered three diachronic stages. The first meaning is to introduce a purpose clause; it is the least grammaticalized since the core lexical meaning of the verb is still apparent. The second meaning that the verb ‘come’ is grammaticalized into is intention; it is more advanced since the core lexical meaning is completely absent. The third meaning the verb come is grammaticalized into is prediction. It can be considered the most advanced since the verb come is used as a preposition meaning ‘around’. Finally, the paper provides several tests to differentiate the lexical verb from the grammaticalized forms including: the types of complements the lexical verb and gramaticalized forms require, the logical completions of the sentences, negation, and elliptical answers for yes/no questions. All of these tests show that the lexical verb and the grammaticalized forms do not require the same complements, are negated differently, and are asked about in yes/ no questions in a different manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This paper studies the grammaticalized meanings of the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ in Jordanian Arabic (JA). Motion verbs particularly ‘come’ and ‘go’ are, according to Heine and Kuteva (2002), Bourdin (2008), and Nakao (2014) besides others, among the most common sources of grammaticalization cross-linguistically. We argue that the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ in Jordanian Arabic has been grammaticalized into three meanings exhibiting three different stages of grammaticalization. Two of the three grammaticalized meanings are clear examples of grammaticalization since they diverge from the core lexical meaning of the verb which involves motion. However, in the third meaning, the lexical meaning of the verb is still present causing ambiguity and exhibiting what Hopper and Traugott (2003) call ‘functional split.’

When it comes to the fully grammaticalized meanings, the most advanced and the most developed is the grammaticalization of the verb into a preposition expressing prediction. The second is the grammaticalization of the verb into an auxiliary verb meaning intention. This stage is considered an intermediate stage on the grammaticalization pathway. The grammaticalized meaning in both cases is quite clear and accessible since they involve diversion from the core lexical meaning of the verb. However, the third, to use the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ to introduce a purpose phrase, is still causing ambiguity with the core lexical meaning. This third stage shows functional split where the verb still carries its lexical meaning, but undergoes expansion in the ‘number and types of contexts in which the grammatical morpheme is appropriate. Bybee et al. (1994, 8). Along the lines of Himmelmann (2004), we argue that the verb ‘come’ in Jordanian Arabic has, in certain contexts, undergone syntactic and semantic expansion to receive unusual complements that has over time ended into the three grammaticalized meanings.

According to Bybee et al. (1994) and Heine et al. (1991), the verbs ‘come’ and ‘go’ are considered two of the most common sources from which future markers are grammaticalized. Other sources include volition verbs such as ‘want’, the action verb ‘do’ and the verb to ‘have’. The grammaticalized ‘come’ and ‘go’ have been abundantly studied cross-linguistically. However, what is really significant about the grammaticalized ‘come’ in JA is that the three grammaticalized meanings show different stages or developments on the pathway of grammaticalization suggested by Bybee et al. (1994: 240). This issue will be handled in details in the section of previous studies.

Since there are no historical records of Jordanian Arabic, the study will attempt, based on synchronic examples from Jordanian Arabic, to clarify the various grammaticalized meanings of the verb come. The data of the study has been obtained by the researchers themselves from natural real life conversations. The researchers have not interfered in the course of the conversation, and have not intended to steer it towards abundant use of the verb ‘come.’ The conversations are natural daily ones the researchers used to have with their family members and friends. The researchers used to take notes of instances of the verb come among other language phenomena.

The article is structured as follows. Section “Literature review” gives a brief theoretical background for the grammaticalization path as well as studies about grammaticalization in Arabic, in general, and in Jordanian Arabic in particular. Section “The grammaticalization of the verb ‘Come’” presents the various meanings of the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ with sundry examples on each meaning. Section “Evidence for grammaticalization” presents pieces of evidence that support the grammaticalization account. In Section “Conclusion”, we give some concluding remarks and recommendations.

Literature review

Theoretical background

The evolution of grammatical categories in the languages of the worlds has been abundantly studied by various scholars including Heine et al. (1991), Heine (1993), Bybee et al. (1994), Bybee (2003), Hopper and Traugott (2003) and Bourdin (2008) just to mention a few. According to these studies, the evolution of grammaticalized categories from lexical sources follows a universal path. As mentioned in the introduction above, the lexical sources that are most willing to undergo grammaticalization are motion verbs such as ‘come’ and ‘go’, volition verbs such as ‘want’, the verb of action ‘do’ and the verb ‘have.’

In their pursuit to pinpoint the pathway which grammaticalization may follow, Bybee et al. (1994) and Bybee (2003) state that the transition from lexical to grammatical usage is obtained through ‘a dramatic frequency increase’ in the number and the types of the contexts and complements the new grammaticalized morpheme may appear in. In other words, the new morpheme undergoes semantic generality. As a result of expanding its semantic content, the lexical item becomes less restricted in occurrence and tends to be used increasingly like a functional word.

According to Traugott (2010), grammatical expressions become ‘more abstract, schematic, and productive’ in comparison to the lexical ones (275). Accordingly, bleaching, a process through which the original meaning of the grammaticalized construction is lost, may take place. Traugott (2010) states that bleaching leads also to ‘loosening of constraints on co-occurence’ (275). In the same veins, Jarad (2013:70) says ‘when the semantic content of a lexical item is lost, the lexical item becomes less restricted in occurrence, i.e. it becomes functionally enriched.’

When it comes to the development of verbs of motion into grammaticalized counterparts, Bybee et al. (1994) have proposed the following figure which illustrates the pathways of the grammaticalization of future markers from movement (240).

The figure shows that the first grammaticalized meaning come and go may develop into is intention which is considered the first stage of grammaticalization. It is also the stage at which ambiguity between the lexical meaning and the grammaticalized meaning frequently takes place i.e. the hearers might not differentiate the grammaticalized meaning from the lexical meaning. The second stage which is considered more advanced and more developed is future; the verbs come and go are used to express future in a very similar manner to ‘going to’ in English. The last stage which is considered the most advanced and the most developed is prediction; the grammaticalized expressions which mean future are used to mean prediction. As mentioned before, the case of the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ in JA is distinctive since it shows the first and the third grammaticalized meanings exhibiting the earliest and latest stages.

Previous studies

In the following paragraphs, the various studies that have focused on grammaticalization in Arabic, standard or vernacular, and those that have focused on the verbs ‘come’ and ‘go’ in particular will be viewed in details.

Tain-Cheikh (2013) has studied the grammaticalized uses of the verb ra(a) ‘see’ in various Arabic dialects. She states that the verb diverges from its core lexical meanings and is used to introduce clauses to give the meaning of ‘do you know?’ The focus of the paper is on Meghrabian dialects; however, JA is mentioned in passing.

Closely related to the study at hand, Esseesy Mohssen (2010) studies the grammaticalization of Arabic prepositions and subordinators following a corpus-based approach. According to Esseesy Mohssen, the preposition fi is a typical example of a preposition that has resulted from a diachronic process starting with fam/fu ‘mouth’ as the lexical source and ending with fi ‘in’ as the end point through intermediate forms. Esseesy throughout his analysis adopts qualitative and quantitative criteria to define the stages of the grammaticalized forms. Qualitatively, the more shortened a form is, the more grammaticalized it will be. Quantitatively, the more shortened a grammaticalized item is, the higher is its frequency.

Another significant study is the one conducted by Camilleri and Sadler (2017) focusing on the relation between posture verbs and aspect in various vernaculars or dialects of Arabic. The paper is restricted to one verb only i.e. the verb gaʕad ‘sit’, and one form of the verb i.e. the active participle (ACT.PTCP.) gaʕId ‘sitting.’ Camilleri and Sadler say that the (ACT.PTCP.) form has been ‘grammaticalized into PROGESSIVE auxiliary.’ (p 168). They give examples on their claim from Tunisian, Emirati, Kuwaiti, Hijazi, Libyan, Maltese, and Jordanian Arabic. Furthermore, they say that as a result of grammaticalization, the ACT.PTCP. is now composed with verbs that are lexically incompatible in meaning with it such as y-nut ‘jump’. They also note that the grammaticalized form can now be used with inanimate subjects like ʔil-bass ‘the bus’ and ʔil-gitar ‘the train.’

Shbool, et al. (2010) have studied the grammaticalization of the future markers in Jordanian Arabic. They state that the future markers ba-, ħa- and ta- have gradually developed from the full lexical items baddI ‘want’, raħ ‘go’ and ħatta ‘until’ respectively. They also say that these clitics have undergone two processes: desementicization or bleaching, by which they have lost their lexical meanings and phonological reduction, whereby they become shortened in form.

Nakao (2014) presents three grammaticalized meanings for the motion verbs ja ‘come’ and ruwa ‘go’ in Juba Arabic. The first and the least grammaticalized meaning, since the lexical meaning is still accessible, is to introduce a purpose-clause construction. The second and the most grammaticalized meaning is future. The third and the one that falls in between the two stages is to use come and go as sequential markers in narrative texts. Nakoa suggests the following path for the development of ja and ruwa into full future markers in Juba Arabic:

Reviewing the literature, one can safely say that the grammaticalization of the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ in Jordanian Arabic has not been studied at all and is worth studying since it posits new meanings that have not been mentioned before.

Altamimi (2021) states that the active participle of posture verbs ga:ʕId ‘sitting’ and ga:jIm ‘standing’, the motion verb raħ ‘he went’ and b-imperfective are the considered cases of grammaticalization. Moreover, he added that the active participle of posture verbs have gone through several processes reaching the grammaticalized status; the processes are semantic extension, semantic bleaching and decategorization but not phonological reduction unlike the b-imperfective and the motion verb raħ.

Jaradat (2021) argues that discourse markers can undergo grammaticalization in a very similar manner to other elements. Jaradat has come up with this argument on the basis of two conclusions. First, these DMs undergo most of the grammaticalization sub-processes other elements have gone through. Second, they are not separated from the structure of the sentence.

The grammaticalization of the verb ‘Come’

As mentioned before, we argue that the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ in Jordanian Arabic has been grammaticalized into three meanings. The first is a verb introducing purpose phrases; the second is an auxiliary verb conveying intention and the third is a preposition conveying prediction. Each meaning will be handled separately in the following sections.

To introduce a purpose phrase

The first meaning the verb ʔadʒa is grammaticalized into is to introduce a purpose clause. This stage is the least grammaticalized since the lexical meaning of the verb is still witnessed; however, it has undergone semantic expansion; the verb has over time developed new complements. Hopper and Traugott (2003) argue that ‘when the semantic content of a lexical item is lost, the lexical item becomes less restricted in occurrence i.e. it becomes functionally enriched’ (101). The verb ‘come’ and its complement i.e. the verb phrase forms a purpose phrase. Consider the following examples:

-

1.

b-t-i:dʒI t-Ilʕab maʕ-na

‘She comes to play with us.’

-

2.

b-i:dʒI ʔIzu:r ʕamt-u

‘He comes to visit his aunt.’

As the examples show, the lexical meaning is still evident; however, the verb come has acquired new contexts that have not been witnessed previously. A verb is not one of the complements the verb ʔadʒa requires, but as a result of the semantic expansion, the verb complement has become appropriate. This finding agrees with Nakao’s (2014) finding about Juba Arabic. Moreover, we agree with Nakao that this new meaning is the most recent and the least grammaticalized. Furthermore, we can say that it is the first stage in the grammaticalization path for the verb come.

The verb can be turned into the past form keeping the same meaning as shown in the following examples:

-

3.

ʔadʒat tIlab ʕIn-na

‘She came to play at our house.’

-

4.

ʔadʒa jIzu:r xa:lt-u

‘He came to visit his aunt.’

In both cases, the present and the past forms of ʔadʒa ‘come’, the lexical meaning is still accessible; however, a new meaning has been attached to the verb i.e. that of purpose.

This meaning i.e. purpose is not accessible in other verbs without the use of the purpose article ʕaʃa:n ‘so as to’. The following examples are considered unacceptable and for some ungrammatical:

-

5.

budrus jIndʒaħ

(he) studies succeeds

-

6.

bIʃrab gahwa jISħa

(he) drinks coffee be-awake

The two examples can be turned grammatical and acceptable when we insert ʕaʃa:n ‘so as to’ after the first verb.

ʔadʒa Intention

The second meaning ʔadʒa ‘come’ is grammaticalized into is intention. The verb form that is used to deliver this meaning is the present form. Consider the following sentences:

-

7.

b-a:dʒI ʔasa:ʕd-u b-Irfuðˤ

‘I intend to help him, but he refuses.’

-

8.

b-t-i:dʒI tIħki: l-u bItbatˤIl

‘She intends to tell him, then she refrains.’

-

9.

b-t-i:dʒI tru:ħ ma: bIxalli:-ha

‘She intends to go, he does not allow her to.’

The intention meaning in (7) is evident and accessible. The speaker is saying frankly that his or her intention is to help the person referred to by the pronoun him. In (8) the verb come is used to express the intention the pronoun she.

This is considered a development on the pathway of grammaticalization since the lexical meaning is absent; it is totally absent in the meaning of the sentence. It seems that the intention meaning has risen as a result of an extension in the type of complements that the verb come requires. The verb ‘come’ has over time developed more complements. We argue that diachronically sentences (7) and (8) used to be interpreted literally i.e. ‘I come to help him, but he refuses,’ and ‘she comes to tell him, but she forgets about it.’ The verb come in both cases is followed with a purpose phrase that clarifies the reason of coming. However, over time, the verb has undergone semantic and syntactic extension resulting in its change into intention. Therefore, the two sentences respectively mean ‘I intend to help him, but he refuses,’ and ‘she intends to tell him, but she refuses.’

Following Bybee et al. (1994)’s pathways of the grammaticalization of future markers, we can safely say that intention is one of the first stages the verbs ‘come’ and ‘go’ may develop into.

The verb ʔadʒa ‘come’, in the past form, can give the meaning of irrealis mood to express unfulfilled intention. Consider the following examples:

-

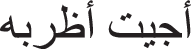

10.

ʔadʒ-i:t ʔaħki:-l-u

‘I was about to tell him.’

-

11.

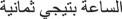

ʔadʒ-at t-xayyitˤ ʔil-farʃeh

‘She was about to sew the mattress.’

-

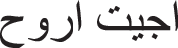

12.

ʔadʒ-u jIðˤrIb-u:

‘They were about to hit him.’

The verb is only used in the past tense in order to express the meaning of unfulfilled intention. We argue that all the sentences above have developed from intention into unfulfilled intention. Diachronically, the previous sentences could be read as (12)–(14) respectively below:

-

13.

I intended (was about) to tell him (but I didn’t).

-

14.

She intended (was about) to sew the mattress, (but she didn’t).

-

15.

They intended (was about) to hit him, (but they didn’t).

Since the actions have not taken place in each of the sentences and it is impossible to take place since the sentences are about the past, the meaning has changed into unfulfilled intention. We assume the following scenario have taken place with this grammaticalized meaning. Initially, the grammaticalized ʔadʒa ‘come’ have been used restrictively with verbs that express ability i.e. lie in the hands of the agent such as leave, hit, sleep, resign to express intention. At a later stage, since the intention is unfulfilled, the intention meaning is lost, and the verb is frequently used with a different meaning i.e. ‘about to’. In other words, the function and the meaning of the verb are being broadened or extended. At this stage, the verb with the new meaning is being used with verbs that cannot be controlled by the agent such as die, fall down, have an accident as the following examples show:

-

16.

ʔadʒ-i:t ʔamu:t

‘I was about to die.’

-

17.

ʔadʒ-at tIgaʕ

‘She was about to fall down.’

-

18.

ʔadʒi:t ʔaʕmal ħa:dIθ

‘I was about to have a car accident.’

ʔadʒa ‘around’

Relying on the data available, we can say that the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ is nowadays used as a preposition that is not related to the lexical meaning of the verb. The preposition means ‘around’ which is used with time expressions and numbers as in:

-

19.

ʕadad-hum b-i:dʒI ʕaʃarah

‘Their number is around ten.’

-

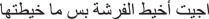

20.

ʔIs-sa:ʕah b-t-i:dʒI ʕaʃarah

‘It’s around ten.’

As the examples show, the grammaticalized verb is usually inflected to agree with a singular subject, masculine when we talk about numbers as in (19) since the word ‘number’ is masculine in Jordanian Arabic and feminine when we talk about time as in (20) since the word ʔIs-sa:ʕah which is used to tell the time and which literally means ‘the hour’ is feminine. As for the tense of the grammaticalized verb, it is only used in the present; it cannot be used in the past or changed into the past tense since it is used as a preposition.

Moreover, the function and the meaning of the grammaticalized verb as a preposition meaning ‘around’ indicates that it cannot be considered a copula since this would hinder the interpretation of the grammaticalized verb as preposition with the meaning of ‘around’. The speaker in (18) does not say ‘It is ten;’ rather, she says ‘It is around ten.’ The speaker is not sure about the exact hour or number; rather, he or she is making a prediction. Moreover, Standard Arabic as well as Jordanian Arabic does not have copulas in the present tense.

One way to prove this preposition interpretation is that the new preposition plus its object whether it is a number or an hour could be used as an answer to a yes/no question. In (19) below, the expression ‘around 10’ could be used as an answer to a question ‘how many are they?’ It is unacceptable to consider ʔadʒa ‘come’ as a copula here since copulas do not appear in short-form answers to yes/no questions. The argument applies to (20) as well. The phrase bidʒi ʕaʃarah can only be interpreted as ‘around ten’ not ‘is ten’ since a copula normally does not appear in elliptical answers to yes/no questions.

-

21.

kam ʕadad-hum? b-i:dʒI ʕaʃarah

‘How many are they?’ ‘Around ten.’

-

22.

kam ʔIs-sa:ʕah?b-t-i:dʒI ʕaʃarah

‘What time is it?’ ‘Around ten.’

The grammaticalized interpretation is further made convincing by the invalid meaning of the previous examples when the verb is interpreted lexically as the English translations of examples 17 and 18 show given below as 21 and 22.

-

23.

*Their number comes ten.

-

24.

*The time/ the hour comes ten.

The purpose of the preposition here is to make predictions. The speaker in both cases is not sure about the exact number of the people in a group or about the exact hour, so he or she is making a prediction. According to the pathways of future markers proposed by Bybee et al. (1994), prediction is the most developed, the most grammaticalized and last stage of grammaticalization ‘come’ and ‘go’ may reach. It seems that this meaning has developed from an earlier use of ‘come’ as a future marker. Diachronically speaking, ‘come’ used to be used as a future marker. Therefore, sentences (17) and (18) used to be interpreted as (23) and (24) below:

-

25.

Their number will be ten.

-

26.

The time will be ten.

Evidence for Grammaticalization

Some generalizations can be deduced from the previous examples in support of the grammaticalized meaning of come. The first generalization has to do with the types of the complements and modifiers the verb ʔadʒa requires. Lexically speaking, the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’, as a motion verb, is an intransitive verb that does not require any complement. One can simply make a fully-grammatical sentence by using the verb with a subject to mean ‘X come (s).’ The verb, however, could be followed by an adjective as in (27), an adverb indicating manner as in (28) or a prepositional phrase acting as an adverb as in (29). The grammaticalized verb, on the other hand, could be followed by a verb as in (30), a noun indicating number as in (31) or by a noun indicating time as in (32).

-

27.

ʔadʒ-a mʕasˤsˤIb

‘He came nervous.’

-

28.

ʔadʒ-u ʔIrkaðˤ

‘They came running.’

-

29.

ʔadʒ-u b-surʕa

‘They came in haste.’

-

30.

ʔadʒi:t ʔaðˤrIb-u

‘I was about to hit him.’

-

31.

ʕadad-hum bi:dʒ-I ʕaʃarah

‘Their number is around ten.’

-

32.

ʔIs-sa:ʕah b-t-i:dʒI θama:njeh

‘It is around eight.’

Another piece of evidence comes from the inflections that may be attached to the lexical verb versus those that appear on the grammaticalized versions. The lexical verb is inflected for number, gender, and person in the past and the present forms. Consider the paradigm of the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ in the present and the past tenses (Table 1).

The grammaticalized expressions, on the other hand, do not show all the inflections the lexical verb usually shows. This is due to the new meanings the expression has and the new grammatical functions. As for the purpose phrase meaning, the verb come still shows all the inflections of the lexical verb since the meaning ‘come’ is still accessible; however, it acquired a new grammaticalized meaning i.e. to express purpose. In the second meaning, which is ‘intention’, the verb is inflected to be in the present tense singular or plural. When changed into the past form, it expresses unfulfilled intention and is inflected to agree with singular or plural, masculine and feminine subjects. This meaning is more varied and can be used with all pronouns in the past.

As for the third meaning i.e. ‘around’, the verb, though grammaticalized as a preposition, is inflected in the present tense to agree with a singular masculine subject when one talks about number and with a singular feminine subject when one talks about time as examples above show.

When compared with the lexical verb, which can be inflected to agree with singular and plural nouns in the past and the present tenses, the new meanings show limited inflections and uses.

The third piece of evidence can be distilled from the following examples.

-

33.

-

a.

ʔadʒi:t ʔarawwIħ

‘I was about to leave.’

-

b.

ʔadʒi:-na nrawwIħ

‘We were about to leave.’

-

c.

-

a.

ʔadʒa ʔIrawwIħ

‘He was about to leave.’

The meaning of the verb ‘come’ is evidently not the lexical meaning. If these examples are taken literally, their meaning will involve contradiction; all of them will mean ‘come to leave/go’ consequently, these examples cannot be interpreted literally. Their meanings are incompatible with the physical disposition of the original meaning of the verb ‘come’. There must be another meaning taken in consideration to explain the acceptability of these examples.

The fourth piece of evidence on the grammaticalized meanings comes from the logical completions of the sentences. As examples 34 and 35 below show, the lexical ‘come’ cannot be followed by completions that mean the opposite of the meaning of the verb:

-

34.

*

ʔadʒi:t mItaxxIr bas bakki:r

‘I came late but early.’

-

35.

*

ʔadʒi:t bI-l-baasˤ bas ma:dʒi:t

‘I came by bus but I didn’t come.’

The grammaticalized verb which carries the meaning ‘unfulfilled intention’, on the other hand, can be followed by completions that mean the opposite as in:

-

36.

ʔadʒi:t ʔaxajjItˤ Il-farʃeh bas ma: xajjatˤit-ha

‘I was about to sew the mattress but then I decided not to.’

-

37.

ʔadʒi:na nrawwIħ bas ma rawwaħ-na

‘We were about to go home but we didn’t’

-

38.

ʔadʒi:t ʔagol-lo- bas ma golIt-l-u

‘I was about to tell him but I refused.’

These examples show that the instances of ‘come’ are not the main verbs of the sentences.

In the same vein, instances of the lexical forms of ‘come’ can be negated by the negation prefixes and suffixes as the following examples show:

-

39.

ʔadʒi:t mItaxxIr / ma: dʒ-i:t-Iʃ mItaxxIr/ ma:ʔadʒi:t mItaxxIr

‘I came late.’/ ‘I did not come late.’/ ‘I did not come late.’

-

40.

ʔadʒ-u mItaxxIri:n /ma ʔadʒ-u:-ʃ mItaxxIri:n / ma: ʔadʒ-u mItaxxIri:n

‘They came late.’/‘They did not come late.’/ They did not come late.

Examples 39 and 40 show that the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ can be negated by both the negation particle ma and the negation suffix -Iʃ, or by the negation particle alone. On the other hand, instances of the grammaticalized ‘come’ cannot be negated in the same manner since they are not the main verbs of the sentences as in:

-

41.

ʔadʒi:t ʔaxxajjItˤ ʔIl-farʃeh / ma xxajjItˤ-Iʃ ʔIl-farʃeh/ ma xxajjItˤ-It ʔIl-farʃeh

‘I was about to sew the mattress.’/‘I did not sew the mattress.’/‘I did not sew the mattress.’

-

42.

ʔadʒi:-na nrawwaħ/ ma rawwaħ-na:-Iʃ /ma rawwaħ-na

‘We were about home.’/‘We did not go home.’/ ‘We did not go home.’

-

43.

ʔadʒi:t ʔagul-l-u / ma gul-t-ulhu:-Iʃ / ma gulut-l-u

‘I was about to tell him.’/ ‘I did not tell him.’/ ‘I did not tell him.

The previous examples show that the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ is not used as the main verb and it is not usually targeted by negation. It is usually the main verb that is targeted by negation.

The previous examples and arguments clearly show that the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ is extensively used to provide grammaticalized meanings that diverge semantically and syntactically from the lexical interpretation of the verb.

The findings of the study are significant from theoretical and pedagogical perspectives. Theoretically speaking, this research contributes to the understanding of language change in general and the processes through which grammatical words change over time from their lexical meanings to acquire new meanings and functions. Additionally, this study contributes to the understanding of grammaticaliztion as a universal unconscious process subsuming some sub-processes leading to the formation of new previously-nonexistent grammatical articles.

The findings of the study emphasize the validity of the grammaticalization pathway as suggested Bybee et al. (1994); the three gramaticalized meanings in the paper follow the pathway of the development of grammaticalized items.

Pedagogically speaking, the findings of the study could be employed in situations where Jordanian Arabic is taught for non-native speakers as a foreign language; the findings could be utilized in curricula of teaching Jordanian Arabic for non-native speakers. The findings of study could enable instructors to account for some linguistic issues that are considered- by some- problematic or not easy to explain.

Finally, it is worth saying that the study is significant since it is one the very few studies that have investigated grammaticalization in Jordanian Arabic, and since it has thoroughly investigated the verb come. It is hoped that the study will pave the way for future research in the field to unveil other grammaticalized expressions in Jordanian Arabic. However, the study is limited in scope since the focus is on one verb only.

Conclusion

This paper has given an account of grammaticalization of the verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ in Jordanian Arabic. The data revealed that the verb come in JA, like several other languages, has undergone grammaticalization, but, unlike what happens in other languages, it has been grammaticalized into three meanings that coexist; the first is to introduce a purpose phrase, the second is intention and the third prediction. These interpretations show that the verb has been semantically broadened.

The paper has shown that the lexical verb ʔadʒa ‘come’, being an intransitive verb, is usually followed by modifiers i.e. an adjective, an adverb or a prepositional phrase as an adverb, while the grammaticalized verb is followed by different complements. The paper has also provided some pieces of evidence that might support the assumed grammaticalized meanings. In addition, the grammaticalized meanings show limited inflections in comparison to the lexical verb which show a whole verbal paradigm.

Data availability

All data analysed in this study are included in this article.

References

Altamimi MI (2021) The Grammaticalization of Lexical Verbs into Progressive and Future Markers in Saudi Najdi Arabic [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Arizona State University

Bourdin P (2008) On the Grammaticalization of Come and Go into Markers of Textual Connectivity. In: Lopez-Couso MJ, Seoana E (Eds.) Rethinking Grammaticalization: New Perspectives. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, p 61–103

Bybee J (2003) Mechanisms of change in grammaticalization: the role of frequency. In: BD Joseph & RD Janda (Eds.) Handbook of Historical Linguistics. p 602–623

Bybee J, Perkins R, Pagliuca W (1994) The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect, and Modality in the Languages of the World. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Camilleri M, Sadler L (2017) Posture verbs and aspect: a view from vernacular Arabic. In: Butt M, King TH (Eds.) Proceedings of LFG’17 Conference, University of Konstanz. CSLI Publications, Stanford, CA, p 167–187

Esseesy M (2010) Grammaticalization of Arabic Prepositions and Subordinators: A Corpus-based Study. Brill, Leiden/ Boston

Heine B, Claudi U, Hunnemeyer F (1991) Grammaticalization: A Conceptual Framework. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Heine B (1993) Auxiliaries: Cognitive Forces and Grammaticalization. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Heine B, Kuteva T (2002) World Lexicon of Grammaticalization. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Himmelmann NP (2004) Lexicalization or grammaticalization: opposite or orthogonal. In: W Bisan, NP Himmelmann & B Wiemer. (Eds.) What Makes Grammaticalization: A Look from its Fringes and Its Components. p 21–42

Hopper PJ, Traugott EC (2003) Grammaticalization. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Jarad NI (2013) The evolution of the B-future marker in Syrian Arabic. Lingua Posnaniensis, 69–85

Jaradat A (2021) Grammaticalization of discourse markers: views from Jordanian Arabic. Heliyon 7(7):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07632

Nakao S (2014) Grammaticalization of já ‘come’ and rúwa ‘go’ in Juba Arabic. In: Osamu H (Ed.) Recent Advances in Nilotic Linguistics (Studies in Nilotic Linguistics 8). ILCAA, Tokyo, p 33–49

Shbool Y, Al-shboul S, Asassfeh S (2010) Grammaticalization of the Future Markers in Jordanian Arabic. AUMLA 5(4):99–110

Taine-Cheikh K (2013) Grammaticalized uses of the verb ra(a) in Arabic: a Maghrebian Specificity? In: Lafkioui M (Ed.) African Arabic: Approaches to Dialectology. De Gruyter, 121–159

Traugott EC (2010) In: Luraghi, S & Bubenik, V (Eds.) Continuum Companion to Historical Linguistics. Bloomsbury Academic. p 269–283

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable. This was not required, as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jaradat, A.A., Al-Omari, M.A., Al-Khawaldeh, N.N. et al. The verb ʔadʒa ‘come’ in Jordanian Arabic: three levels of grammaticalization. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1431 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03901-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03901-w