Abstract

Political, scientific-administrative, as well as practical knowledge, are important for evidence-based policies in the public service. However, empirically, these forms of knowledge have mainly been studied independently, highlighting the need to better understand their interaction in welfare policy. On this basis, the article focuses on understanding the role of practical knowledge in evidence-based welfare policies, using two case studies. Empirically, active employment and public school policy in Denmark are studied as examples of welfare policy during the period from 2010 to 2022, based on documents and interviews with key policy actors. Based on the case studies, a three-stage model of the role of practical knowledge in evidence-based welfare reform is developed. The model illustrates that the role of practical knowledge changes at different stages of evidence-based policy. Public professionals may both rely on practical knowledge when implementing policy in response to evidence-based management and use it when acting as policy actors to re-politicise evidence-based policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evidence-based policy remains a strong ideal in public policy and governments and ministries continue to look for policies “that work” to make public services more effective (Baron, 2018). Despite the principal belief and support in evidence-based policy, however, evidence use in public service often fails to achieve its outcomes and may result in policy conflict (Newman et al., 2017; Dorren and Wolf, 2023). Some studies have emphasized the importance of low levels of policy conflict, a supply of evidence, as well as a policy capacity in public administrations to collect and interpret available, relevant and credible evidence as a key condition for evidence-based policy (Cash et al., 2002; Howlett, 2009; Jennings and Hall, 2012; Newman et al., 2017). Other studies have focused on the importance of practical knowledge and professional expertise in relation to knowledge-based decision-making and argued that evidence-based policy should be replaced by a more modest understanding of evidence-informed policy or practice (Boaz et al., 2019; Flood and Brown, 2020, Head, 2015; Nutley et al., 2007; Powell et al., 2018; Turner et al., 2022). There is a need, however, for a more systematic understanding of the different roles which practical knowledge can play in evidence-based policy (Head, 2008). On this basis the central research question of the article concerns: How to understand the role of practical knowledge in evidence-based welfare policies?

Analytically, the article addresses the question of active labour market policy and public school policy, two cases of welfare policy in Denmark where practical knowledge plays an important role, but with varying levels of professional power. The article draws on ministerial and public documents and 17 interviews with ministry officials, researchers and stakeholders. Based on the case studies, a three-stage model of the role of practical knowledge in evidence-based welfare reform is developed. The model links the interaction between political commitments to use evidence and managerial efforts focused on the advantages of basing policies on evidence to the dynamic role of practical knowledge, which may both act in response to evidence-based management and to re-politicise evidence-based policies (Head, 2008; Head et al., 2014; Howlett, 2009; Paley, 2006; Parsons, 2004; Rousseau, 2006; Toner et al., 2014; Turner et al., 2022; Williams et al., 2020). The model adds to the literature on evidence-based policy by showing how the interaction between political, scientific administrative and practical knowledge may change in different stages of evidence-based policy (Jennings and Hall, 2012; Newman et al., 2017; Dorren and Wolf, 2023; Mackillop and Downe, 2023; Migone and Howlett, 2022).

Understanding the role of political, scientific, and practical knowledge in evidence-based policy

The importance of a political commitment to using evidence, the policy capacity of public administrations and the practical knowledge of public professionals regarding evidence-based policy have been recognized and discussed in several contributions to the literature on evidence-based policy, but often independently (Christensen et al., 2023; Head et al., 2014; Howlett, 2009; Jennings and Hall, 2012; Lester, 1993; Newman et al., 2016, 2017; Mackillop and Downe, 2023; Migone and Howlett, 2022; Paley, 2006; Parsons, 2004; Toner et al., 2014). This is curious since we know that evidence-based policies are often shaped by the attitudes of public professionals in the process of implementation (Adam et al., 2018; Lipsky, 2010 [1980]; Hudson et al., 2019; Tummers and Bekkers, 2014).

Drawing on Brian Head political knowledge is understood as: ‘… the know-how, analysis and judgement of political actors’ (Head, 2008) in the following. Scientific-administrative knowledge is understood as the product of systematic analysis of current and past conditions and trends in science captured by public administrations through their policy capacity to acquire and process research evidence for use in policy-making (Howlett, 2009; Newman et al., 2017; Head, 2008). Finally, public professionals are defined as the people responsible for implementing policies and thus converting them into practice (Tummers et al., 2009). The practical knowledge of public professionals is defined as: “…the ‘practical wisdom’ of professionals in their ‘communities of practice’ and the organizational knowledge associated with managing program implementation” (Wenger, 1998; Head, 2008). To understand the role of practical knowledge in evidence-based welfare policies, the interaction between political, scientific-administrative and practical knowledge is conceptualised below.

Political and scientific-administrative knowledge underpin ambitions of evidence-based policy

It is widely held that political conflict is detrimental to successful evidence-based policy (Head, 2008; Jennings and Hall, 2012). In cases, where political conflict is low, however, governments and ministries with a policy capacity to collect and interpret evidence often pursue evidence-based policies (Jennings and Hall, 2012). In such cases, government ministries are key actors in relation to evidence-based policy lending to their position close to decision-makers and their resources to give policy advice, draft legislation and monitor and evaluate policy implementation (Howlett, 2009; Jennings and Hall, 2012; Migone and Howlett, 2022). As argued by Jennings and Hall, policy capacity includes the availability, relevance and credibility of evidence (2012, 260f). A high policy capacity is dependent on the quality of evidence in terms of approximating the effects of policies and its scope in terms of knowing the effects of a set of policy alternatives. Building a substantial policy capacity may be an ambitious organizational demand in cases where the evidence base for the policy aims currently considered in decision-making is sparse (Newman et al., 2017). In situations where governments are attracted by the prospect of using evidence, ministries may be given the resources to develop a high policy capacity for evidence-based policy. As elaborated below, ministries might attempt to use evidence to increase the effectiveness of public services by setting thresholds for the minimum level of quality of evidence used in policy (research design) or the minimum level of cost-effectiveness for policies that are considered evidence-based (Howlett, 2009, 2015).

Scientific-administrative knowledge, practical knowledge, and evidence-based management

Delivering more efficient public services has been an important agenda for decades as epitomised by the New Public Management agenda (Tummers and Bekkers, 2014). For some, practical knowledge and the tendency of public professionals to exercise judgement based on their local experience rather than evidence is the root of a “performance problem”, which evidence-based policy attempts to solve (Paley, 2006). This performance problem is related to the idea that public service professionals perform their role more or less efficiently and that a central imposition of evidence can be used as a means to improve efficiency among local authorities and public professionals (Weiss et al., 2008). In policy areas where political and administrative decisions continuously refer to centrally collected evidence to improve efficiency locally, the role of scientific-administrative and practical knowledge interact. One can think of the process of imposing evidence as evidence-based management, where evidence that has shown to be effective can be regarded as “best practices” to improve policy performance generally or for poor-performing organizations specifically (Hall and Jennings, 2008; Rousseau, 2006). Imposing evidence-based policies, however, can run into an attribution problem because government ministries do not have an evidence base for knowing whether poor performance is attributable to low evidence uptake or other factors (Adam et al., 2018).

Nevertheless, the reactions of public professionals to evidence-based policy and management may vary. In some cases, public professionals might be willing and inclined to implement centrally defined evidence-based policies. Yet, public professionals are likely to be sensitive to a broad set of aims concerning their practice and to balance managerial desires for more efficiency with other “logics”, including their professional norms, institutional rules and client needs (Tummers et al., 2009; Tummers and Bekkers, 2014). By implication there is potentially a conflict between practical knowledge or “expertise” and “evidence” understood as policies that have been shown to have higher average effects on desired policy aims than policies which are not based on evidence (Paley, 2006; Sackett, 2000). It cannot be taken for granted, however, that public professionals contest such central uses of evidence. Public professionals may respond by suppressing critique and may feel alienated by new policies as they struggle to reconcile increased managerial pressures to perform more efficiently with their norms and perceptions of client needs (Tummers et al., 2009).

Political knowledge and the reactive power of public professionals

Politicians and government ministries may claim policies to be based on evidence even if their policy capacity is low and includes evidence for only a few policy alternatives (Cairney, 2016). It is an indication of a low policy capacity when government ministries look for evidence for their preferred policies without providing an evidence base for determining whether the quality of the evidence or its average effects make them preferable to viable alternatives including already implemented policies (Howlett, 2009). By implication, government ministries may advance policies based on (sometimes selectively picked) evidence to legitimise or justify them (Majone, 1989).

Policy professionals may be collectively organised in professions and hold a “jurisdiction” over a policy domain which allows them to provide diagnosis, inference and treatment of problems in their domain (Abbott, 1988). The power of professionals as policy actors can be conceptualized based on two main characteristics. First, their power to maintain discretion or autonomy over specific decisions taken in delivering public services in policy implementation (Lipsky, 2010 [1980]; Tummers et al., 2009). Second, their power as policy actors to organize and exercise collective action in response to policy initiatives which conflict with their professional norms or client needs (Olson, 1965). Powerful public professionals and the unions representing them may defend their autonomy and the needs of their clients by reacting collectively in response to evidence-based policies in an attempt to re-politicise evidence-based policy by increasing policy salience. Where professional expertise is seen as important in its own right, it can potentially persuade political decision-makers to change policies and e.g. accept calls for evidence to play an informative rather than an imposing role in suggesting evidence to public professionals (MacKillop and Downe, 2023). To summarise, evidence might be used by public professionals as a resource to publicly mobilize critique of decisions that conflict with practical knowledge (Weiss, 1979; Majone, 1989; Boswell, 2018; Wolf and van Dooren, 2018, 297). The role of practical knowledge in different evidence-based welfare policies, however, is also an empirical question, which is explored below.

Case selection and methods

To understand the role of practical knowledge in evidence-based welfare policies the interaction between the three types of knowledge is studied in the active labour market and public school policy in Denmark from 2010 to 2022. The analysis of the cases is explorative in the sense that there is no strong knowledge base for considering the interaction between centrally defined evidence-based policies and the role of practical knowledge as they have mainly been studied as independent factors for evidence-based policy (Head, 2008; Head et al., 2014; Howlett, 2009; Jennings and Hall, 2012; Landry et al., 2003; Lester, 1993; Newman et al., 2016, 2017; Mackillop and Downe, 2023; Parsons, 2004; Toner et al., 2014).

Historically, policy-making in Denmark has been shaped by a neo-corporate tradition of policy-making, which has implied a formalized coordination between key interests (Arter, 2006) and “… a remarkable orientation to negotiation, consensus making, and reasoned debate’ (Campbell and Pedersen, 2014, 14). The level of conflict in the political environment in Denmark has generally been low compared to countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, where conflict in the political environment has been used to explain the use of evidence-based policies (Boswell, 2009; Jennings and Hall, 2012, 259ff). This also applies to the two cases of policy welfare policy selected for analysis including primary education policy and active labour market policy. Even if these domains are shaped by consensual tradition, there is variation between their policy capacity and professional power. In public school policy, teachers have historically been organized as a profession and central uses of evidence have been shaped by practical knowledge and organisations (Hansen and Rieper, 2010). In active labour market policy, by contrast, public service professionals come from different backgrounds and policy capacity in the ministry has been developed based on economic models rather than practical knowledge (Andersen, 2020; Jørgensen et al., 2015). As the distinction between levels of professional power is crude, the explorative analysis below serves the dual function of nuancing and contextualizing the role of practical knowledge and public service professionals in the two cases and generating a theoretical model based on the case studies.

To gain a deep understanding of the interaction between different types of knowledge, a document analysis was conducted based on policy reforms, official ministry documents and research reports, which have evaluated policy developments in the three policy domains in the recent decade (e.g. Amilon et al., 2022; Ministry of Children and Education, 2021; Ministry of Employment, 2023). Knowledge databases and information portals on the ministry websites and public statements were also examined to understand how research-based knowledge is accumulated and disseminated.

In addition, to capture developments in political, scientific-administrative and practical knowledge, 17 semi-structured interviews with ministry officials, stakeholder organisations and researchers were conducted in 2022 and 2023 (cf. Appendix 1). These policy actors were deemed to be in a good position to understand the dynamic between political, scientific-administrative and practical knowledge over time. The interview respondents were selected to cover different perspectives from inside and outside the ministries on the use of different types of knowledge and to represent different organizations and agencies involved in the two cases. All respondents were in senior or executive positions and had several years of experience in their fields. The interviews, approximately 60 min in length, were semi-structured and asked questions about the availability, relevance and collection of evidence in the ministries, as well as how evidence was used in relation to local actors (cf. Appendix 2). All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed using NVivo 12 and coded thematically with the main focus on the three types of knowledge, but also with attention to other factors, which interview persons deemed important for evidence-based policies in the two cases (cf. Appendix 3).

The evidence-based management of active labour market policies

From the 1990s and onwards, labour market policy focused on combating unemployment through a mix of passive and active labour market policies as part of the political ideal of a Danish flexicurity model (Andersen, 2020). Based on widespread political agreement on the importance of reducing unemployment, there was an increase in scientific-administrative knowledge as the Ministry of Employment started to invest in increasing its policy capacity in the 2000s. This included generating better performance information on how job centres and municipalities were doing and accumulating evidence for effective policy interventions (Interview 8; Danish Agency for Labour Market and Recruitment, 2023). Gradually, the policy capacity to collect evidence was strengthened by collecting and ranking policies based on their employment effects. From the early 2010s, this resulted in a policy capacity, which allowed a comprehensive rating of active labour market policies based on their average effects on different groups of unemployed (Interview 8). The Ministry of Employment aimed to use evidence as a basis for increasing policy effectiveness locally, and a “performance gap” in local performance was identified (Hall and Jennings, 2008, 695; Interview 8). The general idea and narrative used by the ministry was that evidence-based policies could successfully improve performance by spreading more effective practices across local actors thus exercising a corrective function on public professional decisions, which were based on notions of expertise or experience (Interview 8; 13; Paley, 2006).

Two factors contributed towards establishing an evidence-based management of the active labour market policies that were implemented locally. First, the identification of the general effects of a high number of early interviews with the unemployed, as well as the effects of some types of business programs sustained an evidence-based policy narrative concerning the evidence-based effects of these types of interventions—in particular to the most resourceful groups of unemployed (Interview 8; 15). Second, evidence-based policies in active labour market policy interacted with the knowledge of politicians as a series of policy reforms were passed in the 2010s, which relied on evidence-based policies such as more caseworker interviews with the unemployed (Amilon et al., 2022). Some reforms simply stipulated that a higher number of interviews must be carried out with resourceful employees, while others relied on a change in economic incentives by giving relatively higher state reimbursements for business-related programs or by giving local actors economic incentives for a quicker shift to employment (Amilon et al., 2022). These reforms reflected a central ambition of improving policy performance locally by imposing centrally defined evidence-based policy interventions (Weiss et al., 2008). Rather than setting an evidence threshold, the ministry identified evidence-based policies as best practices and focused on them to improve policy performance (Hall and Jennings, 2008). Softer policy tools such as benchmarking and best practices were also developed and remain in use to address the performance gap in active labour market policies among poorly performing job centres (Ministry of Employment, 2023).

Compliant active labour market professionals

The key policy goal of decreasing unemployment was perceived by different actors to benefit government, as well as labour market organisations including business organisations and trade unions materially. Business organizations and trade unions generally accepted the evidence-based agenda and successive reforms and sought to participate in discussions over policy reform through insider strategies ahead of policy reforms (Interview 13). By implication, these organisations tended to rely on positive frames of unemployment reforms and their use of evidence (Mouritsen, 2019). Opposition from the unemployed and social organizations close to them was voiced but more scantly (Interview 14; 15; 17; Paulsen, 2017). One important reason was that employed in job centres were not organized as one profession with shared norms. Instead, professionals in the fields come from a mix of educational backgrounds including social work, public management and the private sector (Jørgensen et al., 2015; Interview 11; 14). In addition, the evidence-based management of active labour market policies did not challenge the job centres collectively but focused on poorly performing “laggards” (Hall and Jennings, 2008). As a result, some professionals experienced the evidence-based agenda as a positive factor in helping them improve their practice (Interview 15; 17). This made collective resistance difficult as public professionals in the field did not adopt a common view or position on evidence-based management.

Data on the application of different interventions confirm the view that job centres have, on average, complied with and implemented the policies imposed by evidence-based management. The aggregate level of interviews with unemployed in job centres—a key evidence-based policy in the ministry—increased by 27 per cent from 2.2 million in 2011 to 2.8 million in 2019 and in the same period the average number of interviews per full-time unemployed increased by 50 per cent from around 6 to 9 (Amilon et al., 2022, 40). While the level of private business-related programs increased only slightly, all other types of activation policies decreased in the same period in line with the intentions of successive reforms to focus on evidence-based business programs (Amilon et al., 2022, 39).

Even if evidence-based management was successful in changing local policy outputs in many respects, it also led to an unintended consequence: the changes in the level and mix of interventions did not reduce the costs of active labour market policies in the aggregate. In addition, the most substantial effect of evidence-based management was to increase the pace with which the groups of unemployed closest to the labour market left unemployment. Evidence-based management did not seem to result in higher employment for groups of unemployed with fewer resources and their numbers have not decreased in relative or absolute numbers (Amilon et al., 2022, 38, 39). Thus it is questionable whether evidence-based management has been effective on groups further from employment. The combined challenge of constant costs and limited effects on groups of unemployed further from the labour market has led to a change of policy. In 2022, the centralist government announced that it would pass a reform, which is currently being prepared, to shut down job centres and free local governments from central process requirements (Danish Government, 2022, 13).

Public school policy and the re-politicisation of evidence

In education, the arrival of international tests of student performance such as PISA and PIRLS in 2003 triggered policy debate and subsequent agreement that learning and well-being in Danish primary schools were the central policy goal and that policy performance needed to be improved in student learning broadly and reading and math skills in particular (Karseth et al., 2022). Based on this convergence in political knowledge, the Ministry of Children and Education subsequently focused on descriptive and analytic examinations of school performance data and standardized student skills testing and developed a national testing regime to enhance knowledge or student performance in Denmark (Interview 1, 6). As was the case for active labour market policy, there was increased interest in detailed performance information for public school policy including a specification of how different local authorities and schools were performing. On this basis, data availability and capacity to monitor performance were enhanced by the ministry from the 2010s (Interview 4).

As opposed to active labour market policy, however, there was a challenge in linking evidence-based policies to performance management (Interview 3). The challenge was not a shortage of evidence in itself. At least from the 2010s, there was a large availability of education studies including systematic reviews of the effects of different approaches to teaching (Hattie, 2008). First, however, it was challenging for the Ministry of Education to dictate how teachers should go about their teaching, lending to their legally defined autonomy to conduct teaching and the strong historical role of the profession (The Folkeskole Act, 2022: §18). Second, evidence for the effect of teaching did not link directly to performance measures as the latter focused mainly on student performance and well-being rather than measuring the quality of teaching (Interview 3; 5). In addition, there were competing theoretical understandings of how policies create effects or heterogeneous effects of a policy on different groups of people that interventions target (Interview 3, 6). The main interpretation of the mix of quantitative and qualitative educational studies in the ministry was that the effects of educational policies on teaching were as dependent on how they were carried out and on whether learning outcomes were made visible to students (Interview 1; 3; 6; 9; 16; Hattie, 2008). In contrast to the case of active labour market policy, evidence-based public school policy did not manifest itself as evidence-based management where evidence-based policies could be imposed continuously on teachers. The Ministry of Education developed performance measures to track public grade performance and well-being, but it did not identify evidence-based solutions which could be gradually imposed to address these problems. On this basis, the ministry continued to follow a broad principle of using ‘the best available knowledge’ rather than valuing some specific policies over others based on robust knowledge of their effects (Interviews 1; 2; 7; 16). This open approach to evidence use also meant that the ministerial use of evidence respected practical knowledge and the autonomy of teachers in the classroom and that teachers could interpret the added value of new policies locally as more or less useful for their teaching (Rasmussen, 2020).

Nevertheless, the political interest in improving school performance and equality among students irrespective of socioeconomic background continued and became a priority of the Social-democratically led government in 2011. Rather than solving the challenges in developing an evidence-based policy capacity, the government envisaged a nationwide reform including a number of large-scale changes to the primary school and the context for teaching (Interview 2; 4; 7; 16). This strategy reflects that governments and ministries may use evidence to legitimize policy decisions even if policy capacity is not high (Boswell, 2009; Cairney, 2016; Majone, 1989). The government saw a window of opportunity to demonstrate policy action through large-scale reform (Interview 7). The law passing the reform focused on improving the local context for better performance and well-being by centrally defined, and arguably evidence-based, longer school days, an increased physical exercise of students for a minimum of 45 min per day and a common set of compulsory learning aims (Danish Parliament, 2013; Ministry of Children and Education, 2020).

Defiance from a strong teacher’s profession: a shift to negative frames and reform failure in education

Initially, around 2011 the ministry used the label “New Nordic School” to gather stakeholders to discuss potential policy reform. The government’s reform strategy was first to focus on the potential benefits associated with the reform and second to finance the reform using a mix of government funding and higher teacher productivity including an ambition to deliver two additional hours of teaching per week (Interview 7). The strategy worked initially in the sense that the Danish Union of Teachers, parent organizations and other key stakeholders in public school policy felt included and supported efforts towards more physical activity in school and more interaction between the school and its surrounding environment. The strategy worked politically as a cross-partisan majority of six political parties committed politically to key reform elements.

In April 2013, however, before the reform was passed in parliament, significant disagreements over education policy emerged. The triggering event was a conflict over collective working agreements and a subsequent breakdown in negotiations which resulted in a lockout of teachers with closed schools in 25 days. The conflict was ended by a government intervention, which imposed a regulation of teacher’s working time by law instead of negotiation. Even if the conflicts over collective agreements on working conditions and the Primary School Reform were separate events, the intense conflict over working conditions between the Danish Union of Teachers and local governments spilt over into reactions to the reform (Interview 10). The deeper conflict revealed an ongoing tension between a political inclination to take national political action to do something significant to improve student performance, equality and well-being and on the other hand a local and teacher experience of lack of respect for teacher’s professional values, working conditions and autonomy (Interview 6, 10; Tummers et al., 2009). Although the political party majority was maintained throughout 2013 and the reform was passed in parliament in 2014, the policy conflict became a shadow which rested over the implementation of the reform and most of the primary education policy for years.

As a well-organised profession with the Danish Union of Teachers at the centre, teachers had substantial power to collectively question the legitimacy of the reform and the evidence underpinning it even if it had been passed politically. Evidence for the effect of reform initiatives including longer school days was already questioned before the passing of the reform (Ravn and Jørgensen, 2013). In addition, the combination of a national scope of reform and the conflict over working conditions provided an excellent foundation for the Danish Union of Teachers to collectively contest the reform. One of the most illustrative responses of the Danish Union of Teachers was a reframing of the central idea of the reform of more teaching in schools. While initially framing the aim of the reform positively as a “holistic school” (helhedsskole), the Danish Union of Teachers started to frame it negatively as a “whole-day school” (heldagsskole) thus implying that the reform was more about long school days than about increasing the quality of learning (Interview 6, 7). The combination of the late discovery of who would carry the costs of reform, as well as the manifest and public display of intense policy conflict over working conditions created a boomerang effect in educational policy conflict (Wolf and van Dooren, 2018). Divergence in policy positions became generalized and policy implementation was characterized by a lack of will in many schools to implement the reform, which eventually failed to achieve its key objectives of increasing student learning, equality and well-being and thus had negative long-term implications for primary school reform efforts (Ministry of Children and Education, 2020, 2021).

A three-stage model of the role of practical knowledge in evidence-based welfare reform

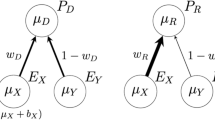

The above case studies have explored variations in the role of practical knowledge in evidence-based policies in the active labour market and public school policy. On this basis, the model presented in Fig. 1 links political, scientific-administrative and practical knowledge to three stages of evidence-based welfare reform to understand the role of practical knowledge in evidence-based welfare policies.

As illustrated by the model, stage 1 involves the identification of evidence-based policies through a combination of political and scientific-administrative knowledge. Following Jennings and Hall, this process is likely to be dependent on the policy capacity of government agencies, as well as a low level of political conflict over the prospect of collecting evidence to identify effective policies to achieve selected policy aims (2012). In policy areas where government ministries have a high policy capacity, they may identify and adopt specific evidence-based policies as was the case in active labour market policy. In this stage, practical knowledge is likely to play a limited role as the interplay between political and scientific-administrative knowledge mainly takes place between governments and their ministries.

Stage 2 involves evidence-based management in which evidence is imposed on public professionals to make public services more effective. As illustrated by the case of active labour market policy, evidence may be imposed by a mix of regulation, benchmarking, incentives and best practices (Hall and Jennings, 2008; Weiss et al., 2008). Policy change is gradual and does not create spikes in salience or policy conflict. In this stage, public professionals act as implementers with responsibility for translating evidence-based policies into practice (Møller, 2018). Public professionals in poorly performing organisations in particular are put under pressure to accept a gradual imposition of evidence even if they may have questions about the effects on clients. Collective professional resistance to policy imposition is unlikely as it is mainly the laggards that feel efficiency pressures. For professionals in poorly performing organisations in particular there is a risk of suppressed policy conflict and alienation because the managerial pressure for efficiency conflicts with a client logic (Tummers et al., 2009).

In stage 3, evidence use is re-politicised. In this stage, public professionals are conceived of as policy actors, which may rely on practical knowledge and collective action to challenge evidence-based policies. Practical knowledge can take the form of shared professional knowledge or be performed more independently by different public service professionals. As exemplified by the public school case, powerful professionals may cause conflict by defying evidence use, even in cases where there is broad political agreement on policy change. This shows that powerful professionals can defy and politicise the use of evidence-based on their professional expertise and influence the knowledge of political actors in turn. An important aspect of practical knowledge is to facilitate a shift between policy implementation (stage 2) and re-politicisation (stage 3). This is more likely in cases where evidence cannot be directly linked to the performance of public service professionals, such as in the case of public school policy where teachers have maintained autonomy in teaching. In addition, a move towards re-politicisation is likely to occur faster in cases where powerful professionals have the resources to contest and re-politicise policy reform. Policy conflicts with a high salience and contestation over evidence use may have long-term consequences, which may lead policy-makers to pursue more collaborative modes of policy-making to avoid future policy conflicts (Dorren and Wolf, 2023).

Conclusions

This article has studied the role of practical knowledge in evidence-based welfare policies. The analysis of evidence-based welfare reform in the active labour market and public school policy in Denmark from 2010 to 2022 illustrates that the role of practical knowledge is influenced by the ability of public professionals to challenge evidence-based policies. In active labour market policy, public professionals mainly used practical knowledge in policy implementation, while the role of practical knowledge in public school policy focused more on re-politicising policy reform.

The three-stage model presented in Fig. 1, suggests two central roles for practical knowledge in evidence-based welfare reform. First, practical knowledge responds to scientific-administrative knowledge, which is used for the evidence-based management of public professionals. As illustrated by the case of active labour market policy the evidence-based management stage may stretch over several years in cases where politicians and government ministries remain committed to delivering on policy goals by promoting the effectiveness of public services. Second, as illustrated by the public school case, however, public service professionals can also use their practical knowledge to re-politicize the use of evidence in an attempt to persuade political decision-makers to change policy. The move to this stage was fast in public school policy in response to policy conflict over working conditions and a failure to pursue evidence-based management in public school policy in Denmark. The model thus conceptualises how the role of practical knowledge in relation to evidence-based welfare policies unfolds over time. The model can be applied to other cases of welfare policy to study changes in the three stages in the model depending on the ability of evidence-based policies and performance indicators to guide and influence practical knowledge and the power of public professionals.

Some scholars have considered the role of practical knowledge mainly as a source of error in implementing evidence-based policies (Paley, 2006; Sackett, 2000). In such a perspective, practical knowledge should be subordinated to scientific-administrative knowledge, which imposes evidence-based policies on implementing public professionals. While this line of thinking resonates with the evidence-based management pursued in active labour market policy, the effect of evidence-based management on professions varies. Public service professionals in active labour market policy were willing to adapt to new centrally defined policies and standards, but without developing a more “explicit professionalism”, which has been used to characterise the development of public service professionals in Danish child protective services (Møller, 2019). In public school policy, teachers have retained their autonomy to define how they go about their teaching despite centrally defined learning goals (Rasmussen, 2020). The article and three-stage model presented above have added that practical knowledge can also serve the function of re-politicising evidence-based policies. This implies that it cannot be taken for granted that government agencies with substantial policy capacities and low political conflict will continue to act as evidence-based agencies as suggested by Jennings and Hall (2012). Practical knowledge can appeal to politicians by re-politicising policy thus contributing towards a change in the political knowledge that dictates evidence-based policy in the first place. This reflects the conflict potential of practical knowledge found in other studies (Boswell, 2009; Dorren and Wolf, 2023). The dynamic understanding of the role of practical knowledge in evidence-based welfare reform provided by the three-stage model is important for understanding how the interaction between political, scientific-administrative and practical knowledge may change in different stages of evidence-based welfare policy even if the pace with which these changes take place may vary in different policy contexts (Jennings and Hall, 2012; Newman et al., 2017; Dorren and Wolf, 2023; Mackillop and Downe, 2023; Migone and Howlett, 2022; Dorren and Wolf, 2023).

Data availability

The data used in this research are available from the author upon reasonable request.

References

Abbott A (1988) The system of professions: an essay on the division of expert labor. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Adam C, Steinebach YY, Knill C (2018) Neglected challenges to evidence-based policy-making: the problem of policy accumulation. Policy Sci. 51:269–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-018-9318-4

Amilon A, Holt H, Houlberg K, Jensen JK, Jonsen EH, Kleif HB, Mikkelsen CH, EHE Topholm. 2022. “Jobcentrenes Beskæftigelsesindsats”. VIVE—Det Nationale Forsknings- og Analysecenter for Velfærd

Andersen NA (2020) The constitutive effects of evaluation systems: lessons from the policymaking process of danish active labour market policies. Evaluation 26(3):257–74

Arter D (2006) Democracy in scandinavia: consensual, majoritarian or mixed? Manchester University Press, Manchester

Baron J (2018) “A brief history of evidence-based policy”. ANNALS Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 678(1):40–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218763128

Boaz A, Huw TO, Davies AF, Nutley SM (2019) What works now? Evidence informed policy and practice. Bristol University Press, Bristol

Boswell C (2009) The political uses of expert knowledge: Immigration policy and social research. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Boswell C (2018) Manufacturing political trust. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Cairney P (2016) The politics of evidence-based policy making. Palgrave Macmillan

Campbell JL, Pedersen OK (2014) The national origins of policy ideas: knowledge regimes in the United States, France, Germany, and Denmark. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Cash D, Clarck WC, Alcock F, Dickson NM, Eckley N, Jäger J (2002) Salience, credibility, legitimacy and boundaries: linking research, assessment and decision making. Available at SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.372280

Christensen J, Holst C, Molander A (2023) Expertise, policy-making and democracy. Routledge, Abingdon

Danish Agency for Labour Market and Recruitment (STAR) (2023) ”Evidence-based policy-making”. Available at https://www.star.dk/en/evidence-based-policy-making/

Danish Government (2022) Ansvar for Danmark: det politiske grundlag for Danmarks regering. Statsministeriet. Available at https://www.stm.dk/statsministeriet/publikationer/regeringsgrundlag-2022/

Danish Parliament (2013) L 51 Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om folkeskolen og forskellige andre love, Folketinget. Available at https://www.ft.dk/ripdf/samling/20131/lovforslag/l51/20131_l51_som_vedtaget.pdf

Dorren L, Wolf EE (2023) How evidence-based policymaking helps and hinders policy conflict. Policy Politics. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557321X16836237135216

Flood J, Brown CC (2020) Exploring teachers’ conceptual uses of research as part of the development and scale up of research-informed practices. Int J Educ Policy Leadersh 16(10):1–17. https://doi.org/10.22230/ijepl.2020v16n10a927

Hall JL, Jennings Jr ET (2008) Taking chances: evaluating risk as a guide to better use of best practices. Public Adm Rev 68(4):695–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.00908.x

Hansen HF, Rieper O (2010) The politics of evidence-based policy-making: the case of Denmark. Ger. Policy Stud. 6(2):87–112

Hattie J (2008) Visible learning—a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge, London

Head BW (2008) Three lenses of evidence‐based policy. Aust J Public Adm 67(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.2007.00564.x

Head BW (2015) Toward more “evidence-informed” policy making? Public Adm Rev 76(3):472–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12475

Head BW, Ferguson M, Cherney A, Boreham P (2014) Are policy-makers interested in social research? Exploring the sources and uses of valued information among public servants in Australia. Policy Soc. 33:89–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2014.04.004

Howlett M (2009) Policy analytical capacity and evidence‐based policy‐making: lessons from Canada. Can Public Adm. 52(2):153–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-7121.2009.00070_1.x

Howlett M (2015) Policy analytical capacity: The supply and demand for policy analysis in government. Policy Society 34(3-4):173–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.002

Hudson B, Hunter D, Peckham SS (2019) Policy failure and the policy-implementation gap: can policy support programs help? Policy Des Pract 2(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2018.1540378

Jennings Jr ET, Hall JL (2012) Evidence-based practice and the use of information in state agency decision making. J Public Adm Res Theory 22(2):245–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur040

Jørgensen HK, Baadsgaard, Nørup I (2015) De-professionalization through managerialization in labour market policy: lessons from the Danish experience. In Klenk T, Pavolini E (eds) Restructuring welfare governance: marketisation, managerialism and welfare state professionalism. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp 163–182

Karseth B, Sivesind K, Steiner-Khamsi GG (2022) Evidence and expertise in Nordic education policy: a comparative network analysis. Springer Nature

Landry R, Lamari M, Amara N (2003) The extent and determinants of the utilization of university research in government agencies. Public Adm Rev 63(2):192–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00279

Lester JP (1993) The utilization of policy analysis by state agency officials. Knowl Creation Diffus Utilization 14(3):267–290

Lipsky M (2010 [1980]) Street-level bureaucracy: dilemmas of the individual in public service. Russell Sage Foundation

MacKillop E, Downe J (2023) What counts as evidence for policy? An analysis of policy actors’ perceptions. Public Adm Rev 83(5):1037–1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13567

Majone G (1989) Evidence, argument, and persuasion in the policy process. Yale University Press, Yale

Migone A, Howlett M (2022) Assessing policy analytical capacity in contemporary governments: new measures and metrics. Aust J Public Adm 82(1):3–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12564

Ministry of Children and Education (2020) Folkeskolens udvikling efter reformen. En vidensopsamling om folkeskolereformens følgeforskningsprogram 2014–2018. Available at https://www.uvm.dk/publikationer/2021/210531-en-vidensopsamling-om-folkeskolereformens-foelgeforskningsprogram-2014-2018

Ministry of Children and Education (2021) Sammen om Skolen”. Available at https://www.uvm.dk/aktuelt/nyheder/uvm/2021/maj/210528-regeringen-og-folkeskolens-parter-gaar-sammen

Ministry of Employment (2023) Benchmarking: Hvilke kommuner gør det godt? Available at https://bm.dk/arbejdsomraader/aktuelle-fokusomraader/benchmarking/

Mouritsen J (2019) Fagbevægelsen kræver opgør med jobcentre: Vi har et system, som er så uensartet, at det er helt uacceptabelt. Børsen. Available at https://borsen.dk/nyheder/politik/fagbevaegelsen-kraever-opgor-med-jobcentre-vi-har-et-system-som-er-saa-uensartet-at-det-er-helt-uacceptabelt?b_source=fagbevaegelsen-kraever-opgor-med-jobcentre-vi-har-et-system-som-er-sa-uensartet-at-det-er-helt-uacceptabelt&b_medium=row_&b_campaign=1218503_

Møller AM (2019) Explicit professionalism. A cross-level study of institutional change in the wake of evidence-based practice. J Prof Organ 6(2):179–195. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/joz003

Møller AM (2018) Organizing knowledge and decision-making in street-level professional practice: a practice-based study of Danish child protective services. SL Grafik, Frederiksberg

Newman J, Cherney A, Head BW (2016) Do policy makers use academic research? Reexamining the two communities theory of research utilization. Public Adm Rev 76(1):24–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12464

Newman J, Cherney A, Head BW (2017) Policy capacity and evidence-based policy in the public service. Public Manag Rev 19(2):157–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1148191

Nutley SM, Walter I, Davies HTO (2007) Using evidence. how research can inform public services. Bristol University Press, Bristol

Olson M (1965) The logic of collective action. public goods and the theory of groups. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Paley J (2006) Evidence and expertise. Nurs Inq 13(2):82–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2006.00307.x

Parsons W (2004) Not just steering but weaving: relevant knowledge and the craft of building policy capacity and coherence. Aust J Public Adm 63(1):43–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.2004.00358.x

Paulsen S (2017) 10 år med jobcentre—Hvad er der at fejre? Socialrådgiveren. Available at https://socialraadgiverne.dk/faglig-artikel/jobcentre-10-aars-reformstorm/

Powell A, Davies HTO, Nutley SM (2018) Facing the challenges of research-informed knowledge mobilization: ‘Practising what we preach?’. Public Adm 96(1):36–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12365

Rasmussen NB (2020) Lærerfaglighed som genstand for styring. Hvordan lærere gav mening til læringsmålstyret undervisning i årene efter folkeskolereformen 2014. Tidsskr Arbejdsliv 22(3):25–41. https://doi.org/10.7146/tfa.v22i3.122823

Ravn K, Jørgensen HB (2013) Lærere—det er jer, der kan løfte folkeskolen. Folkeskolen. Available at https://www.folkeskolen.dk/arbejdsliv-folkeskoleloven-folkeskolen-nr-09-2013/laerere-det-er-jer-der-kan-lofte-folkeskolen/470793

Rousseau DM (2006) Is there such a thing as “evidence-based management”? Acad Manag Rev 31(2):256–269. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.20208679

Sackett DL (2000) The sins of expertness and a proposal for redemption. Br Med J 320:1283. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1283

The Folkeskole Act (Folkeskoleloven) (2022) Available at https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2022/1396

Toner P, Lloyd C, Thom B, MacGregor S, Godfrey C, Herring R, Tchilingirian J (2014) Perceptions on the role of evidence: an English alcohol policy case study. Evid Policy 10(1):93–112. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426514X13899745453819

Tummers L, Bekkers V, Steijn B (2009) Policy alienation of public professionals: application in a new public management context. Public Manag Rev 11(5):685–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030902798230

Tummers L, Bekkers V (2014) Policy implementation, street-level bureaucracy, and the importance of discretion. Public Manag Rev 16(4):527–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.841978

Turner S, D’ Lima D, Sheringham J, Swart N, Hudson E, Morris S, Fulop NJ (2022) “Evidence use as sociomaterial practice? A qualitative study of decision-making on introducing service innovations in health care”. Public Manag Rev 24(7):1075–1099. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1883098

Weiss CH (1979) The many meanings of research utilization. Public Adm Rev 39(5):426–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/3109916

Weiss CH, Murphy-Graham E, Petrosino A, Gandhi AG (2008) The fairy godmother—and her warts: making the dream of evidence-based policy come true. Am J Eval 29(1):29–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214007313742

Wenger E (1998) Communities of practice: learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Williams J, Rychetnik L, Carter S (2020) Evidence-based cervical screening: experts’ normative views of evidence and the role of the ‘evidence-based brand’. Evid Policy 16(3):359–374. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426418X15378680442744

Wolf EE, Van Dooren W (2018) Conflict reconsidered: the boomerang effect of depoliticization in the policy process. Public Adm 96(2):286–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12391

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Independent Research Fund Denmark (DFF) under grant number: 0133-00183B. DFF has funded the research project “Evidence-based policy-making in ministries. Explaining the effects of evidence standards on knowledge utilization”, to which this article contributes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author has written this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The research presented in the article was performed in accordance with the Danish Code of Conduct for Research Integrity, which does not require formal approval of studies based on publicly available documents or interviews.

Informed consent

Informed written consent was obtained from all interview participants before the interviews took place. All participants were fully informed that their anonymity was assured, why the research was being conducted and how their data would be utilized.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kelstrup, J.D. Understanding the role of practical knowledge in evidence-based welfare reform—a three-stage model. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1438 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03937-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03937-y

This article is cited by

-

Study on design and practice of PBL teaching model based on STEM education concept

Scientific Reports (2025)