Abstract

Based on her Chinese story “Jinsuo Ji”, the renowned bilingual writer Eileen Chang produced two English versions, i.e. The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue”. The basic difference between the two English versions lies in that The Rouge of the North is more of a rewriting, while “The Golden Cangue” is a direct translation. An interesting issue emerges as to how characters are constructed in those two inter-related texts. This study, taking direct speech as an indicator of character portrayal, adopts a corpus-assisted approach to characterisation in the two texts. The study elaborates on the functions fulfilled by direct speech in constructing characters and carries out a comparative analysis of characterisation in the two texts. The results show that, due to distinctive uses of direct speech, there are subtle yet definite differences between The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue” in shaping characters’ verbal prominence, establishing characters’ verbal interactional relationships, and presenting the protagonists’ linguistic features. Devoted to the issue of characterisation in literary metamorphosis, the study demonstrates the multiple functions performed by direct speech in character portrayal and has some implications for improving corpus methods to examine the complexities of characterisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The term characterisation refers to the overall process and result of ascribing traits, qualities, properties, attributes, or characteristics to identified agents in the storyworld (Jannidis, 2009, p. 15). Characterisation in literary texts has long been a question of great interest not only in theoretical accounts (e.g. Margolin, 1983; Rimmon-Kenan, 1983/2002; Culpeper et al., 1998; Culpeper, 2001, 2002a, 2009) but also in pilot studies (e.g. Burrows, 1987; Culpeper, 2002b, 2014a, 2014b; Bubel, 2006; Bednarek, 2011, 2012; Mahlberg and Smith, 2012; Mahlberg, 2013; Balossi, 2014; Mahlberg et al., 2016; Ruano, 2018a, 2018b; Archer and Findlay, 2020; Furlan and Kavalir, 2021). Following those literary studies, characterisation has also been approached from the perspective of translation studies in recent years (e.g. Bosseaux, 2013; McIntyre and Lugea, 2015; Ruano, 2017; Kia and Ouliaeinia, 2016; Zeven and Dorst, 2021; Zhao and Li, 2021).

Characterisation can be realised in both explicit (or direct) and implicit (or indirect) ways. Specifically, in explicit characterisation, the qualities of a certain character are directly told by the author (or via the narrator or another character). By comparison, in implicit characterisation, the traits of the character should be inferred from his/her thought, action, speech, behaviour, appearance, interaction with other characters, etc.

Among those various characterisation techniques, direct speech is “a crucial aspect of the externalisation” of characters (Mahlberg, 2013, p. 76). Providing unmediated access to the emotions, desires, and preferences of characters, direct speech minimises the intervention of the writer or narrator, and, meanwhile, maximises the immediacy of characters. According to Page (1988, p. 97), characters’ speech is as unique as their “fingerprints”. It has “a distinctive role” which helps differentiate between narrator’s report and characters’ utterance on the one hand, and also contributes to the individuality of each character on the other hand (Page, 1988, p. 3, 16). That is to say, direct speech makes a differentiation not only between the narrator and the character, but also between different characters.

Despite the peculiarities of direct speech, “fiction is often treated in corpus linguistics as if it were a homogenous genre, and there is very little quantitative research on the language of direct speech in modern fiction” (Axelsson, 2009, p. 189). That is, many corpus linguistic studies make little or no differentiation between direct speech and narrative parts when they are approaching literary texts. In fact, such disregard for direct speech exists not only in corpus linguistics but also in corpus-assisted literary studies and translation studies. Even when different forms of speech presentation are examined, indirect speech and free indirect speech prove to be the two more interesting forms, while direct speech, which is the most common and yet least deviant form, tend to be ignored by many scholars. Therefore, the role of direct speech in characterisation remains to be further explored in both theoretical accounts and empirical studies.

Against this background, the current study aims to adopt a corpus-assisted approach to re-examine fictional characterisation from the under-researched viewpoint of direct speech. It digs into characterisation in two inter-related English texts, the novel The Rouge of the North (Chang, 1967/1998) and the novella “The Golden Cangue” (Chang, 1971)Footnote 1, both of which are re-written in English by Eileen Chang in accordance with her Chinese story “Jinsuo Ji” (Chang/Zhang, 1943a, 1943b)Footnote 2. Although both texts derive from a same text, “The Golden Cangue” is a direct translation from “Jinsuo Ji”, while The Rouge of the North is more of a rewriting (more specifically an enlargement) of “Jinsuo Ji”. Since those two English texts share not only a similar plot but also similar characters, there emerges an interesting issue as to how characters are constructed in each text.

Taking direct speech as an indicator of characterisation in The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue”, this study will address the following research questions:

-

(1)

By using direct speech, do the two texts give equal verbal prominence to similar characters?

-

(2)

Based on characters’ direct speech, what verbal interactional relationships are constructed in the two texts?

-

(3)

In the case of the protagonists, do they differ in their linguistic features (including word classes and semantic fields)? If so, what do their linguistic preferences reveal about their characteristics?

The corpus-assisted approach adopted in this study allows for the possibility of detecting the multiple functions of direct speech in fictional characterisation. Meanwhile, it facilitates quantitative linguistic research on direct speech and ensures reliable results from corpus investigations. Overall, this study has some implications for recognising the multi-faceted role of direct speech in characterisation and improving the application of corpus methods in literary studies and translation studies.

Research on characterisation

Much illuminating theoretical work has been done on characterisation, and many researchers have worked out various types of characterisation techniques. Rimmon-Kenan (1983/2002, pp. 61–72), one of the pioneers in this field, considered direct definition (explicitly telling the traits of the characters) and indirect presentation (displaying and exemplifying the traits in different ways) as the two basic types of textual indicators of characterisation, and included analogy as a reinforcement of characterisation. In addition to the differentiation between direct and indirect characterisation, Pfister (1988, pp. 183–195) also distinguished figural and authorial characterisation, thus proposing four types of characterisation techniques: explicit-figural, implicit-figural, explicit-authorial, and implicit-authorial. In a similar vein, Culpeper (2001, pp. 34–38, 163–233) identified a series of textual cues for the study of characterisation, including explicit cues, implicit cues and authorial cues. Further, Culpeper and Fernandez-Quintanilla (2017, p. 93) reassembled those textual cues and then proposed three dimensions in characterisation: narratorial control, self- and other-presentation, as well as explicit and implicit textual cues. Generally speaking, the textual features, which are indicative of characterisation in various genres and media, range from action, speech, context, social relationships, to descriptions of physical appearance and body language (see Schneider, 2001, p. 611; De Temmerman, 2010, pp. 42–43; Mahlberg, 2013, p. 40; Stockwell and Mahlberg, 2015, p. 134). Those identified textual realisations can serve as valuable starting points for pilot studies of characterisation.

Based on those theoretical insights into characterisation techniques, pilot studies of characterisation have been carried out in various genres or media. A large number of pilot studies investigated characterisation in literary works produced by well-known writers, most notably William Shakespeare (Archer and Findlay, 2020; Archer and Gillings, 2020; Culpeper, 2002b, 2014a, 2014b; Furlan and Kavalir, 2021), Jane Austin (Burrows, 1987; Fischer-Starcke, 2009, 2010; Hubbard, 2002), Charles Dickens (Mahlberg and Smith, 2012; Mahlberg et al., 2016; Mahlberg et al., 2019; Stockwell and Mahlberg, 2015; Ruano, 2018a, 2018b; Ruano San Segundo, 2016, 2017), Virginia Woolf (Balossi, 2014), etc. Some pilot studies were devoted to characterisation in television (Bednarek, 2011, 2012; Bubel, 2006; Bubel and Spitz, 2006; McIntyre and Lugea, 2015), film (Bosseaux, 2015; McIntyre, 2008), as well as many other genres or media (Culpeper et al., 1998; Culpeper, 2001; Eder et al., 2010; Sheikh-Farshi et al., 2018). Overall, focused on such diverse parameters as point of view, mind style, discourse presentation, speech acts, etc., previous pilot studies have explored the issue of characterisation from a variety of research perspectives, including narratology, stylistics, pragmatics, cognitive psychology, social psychology, gender studies, (critical) discourse analysis, and corpus linguistics.

Recent years have also witnessed emerging studies of characterisation in translated texts. For example, focusing on the television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer and its French translations, Bosseaux (2013) compared the original and the translation in terms of the performance of the character Spike, examined Spike’s vampiric otherness against his American background, and reflected on how translation could be used to reduce his otherness. McIntyre and Lugea (2015) investigated the characterisation in a peculiar translation type, i.e. from audio dialogue to corresponding subtitles for deaf and hard-of hearing (DHOH) viewers. Based on the differences between the dialogue and subtitles, the authors followed a cognitive model of characterisation to determine the influence of such differences on DHOH viewers’ conception of characters. Their findings showed that omissions from the subtitles were mostly interpersonal features of dialogue, which had an adverse effect on the relationships between characters. Kia and Ouliaeinia (2016) drew on the model of lexical explicitation in literary translation to investigate the English translations of modern Persian literary works of different genres. Paying particular attention to the relationship between lexical explicitation and drama translation, the study pointed out that lexical explicitation served as a strategic device for enhancing characterisation and performability in drama translation. Comparing Dicken’s novel Hard Times and its four Spanish translations, Ruano (2017) carried out a corpus-based study into the role of speech verbs in characterisation, and discovered that none of the four translations entirely preserved the value of the speech verbs in characterisation. Ruano argued that the misfunction of speech verbs in the four translations might affect the way in which readers formed impressions of characters in their minds. Zeven and Dorst (2021) explored the characterisation of Daisy Buchanan in two Dutch translations of The Great Gatsby, and found that, compared with the source text, both translations reinforced the manipulative power and perceived seductiveness of Daisy, which painted a more negative picture of the female character. Zhao and Li (2021) conducted a corpus-based study of English translations of Luotuo Xiangzi to determine the role of translator positioning in characterisation. Adopting a systemic framework which incorporated Appraisal Theory into the characterisation model, the study found that translator positioning had a significant effect in constructing the character Xiangzi in translation.

Together, current studies of characterisation in translated texts, to some extent, are limited in research scope, perspective, and methodology. Many questions concerning characterisation and translation (e.g. How is characterisation realised in source text and (multiple) translated texts? Whether elements of characterisation in source text are skewed in (multiple) translated texts, and, if so, in what way? What are the consequences of such skewness for the characterisation in (multiple) translated texts? Whether and how multiple translated texts of a same source text diverge in literary characterisation? How to systemically describe those divergences between multiple translated texts?) remain to be answered or responded. It is noteworthy that characterisation in translations studies still needs further exploration.

Direct speech as an indicator of characterisation

Character’s direct speech “provides the illusion of real conversation” (Leech and Short, 2007, p. 132). It makes up a complete system which is peculiar to each literary text. Usually in the form of dialogue, direct speech vividly displays the verbal exchanges between characters. Those verbal interactions can be frequent or infrequent, depending on specific characters in literary works.

As an important technique of characterisation, direct speech performs at least three functions in the process of constructing characters in literary texts. First, at the macro-level, characters’ direct speech, be it in monologue or dialogue, suggests the verbal prominence of certain characters through speech length. When assigned more space to “speak” in a literary work, the character is actually given more verbal prominence by the writer or narrator. This means the longer a character’s direct speech is, the more verbally prominent the character is. Such a function can be easily noticed by readers.

Second, at the meso-level, when characters’ direct speech is used to make up dialogues, it establishes the verbal interactional relationships between characters. In other words, direct speech in dialogues not only displays characters’ verbal exchanges in a story, but also relates to the interactional or interpersonal relationships constructed between the characters.

Third, at the micro-level, direct speech reflects certain linguistic features (e.g. lexical features, grammatical features, semantic features) peculiar to each character. That is to say, the specific lexis and grammar employed by a certain character in direct speech exactly reveal his/her individual linguistic habits, which is hidden and thus less perceptible in characterisation.

Those three functions of direct speech are of different degrees of recognition and perception. For example, the macro-level function (characters’ verbal prominence) can be more readily recognised, compared with the micro-level function (characters’ linguistic features). The above-discussed three functions of direct speech in characterisation will be explored in detail in this study.

Methods

Materials

The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue” can be seen as the literary metamorphoses from a Chinese novella into English versions. As shown in Fig. 1, both The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue” can be traced back to “Jinsuo Ji” written by Eileen Chang, a renowned woman writer in Chinese literature as well as world literature. The Chinese novella “Jinsuo Ji” was originally serialised in two parts in 1943 on Shanghai magazine Zazhi (Vol. 12, issues 2–3). Based on the plot of “Jinsuo Ji”, an English novel entitled Pink Tears was produced, but it was unfortunately rejected by the publisher Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1957 (Hsia, 2014, p. 5). Then Pink Tears was re-written in English, renamed The Rouge of the North, but still remained unpublished (Li, 2010, p. 392; Bu, 2013, p. 145). Subsequently, The Rouge of the North was translated into Chinese under the title Yuannü, which was serialised in Xingdao Wanbao (Hong Kong) and Huangguan (Taiwan) in 1966 (Tang, 1984, p. 372, cited in Li, 2010, p. 392). Yuannü was further developed into two versions: it was, one the one hand, back translated into English under the title The Rouge of the North, which was published by Cassell and Company, Ltd. in 1967 and republished by the University of California Press in 1998 (Gao, 2015, pp. 205–206); on the other hand, it was revised and then published by Crown Publishing Co. in 1968. Later on, the original Chinese novella “Jinsuo Ji” was translated into “The Golden Cangue”, which was included in Hsia’s Twentieth Century Chinese Stories, published by Columbia University Press in 1971.

As described above, the intertextual relations between The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue” are quite complex. From 1943 to 1971, the same story was (re)narrated for several times in both Chinese and English, and all the derivative translations, revisions, and rewritings were completed by the original author Eileen Chang herself, which is remarkable not only in the history of Chinese literature but also in the history of world literature.

The texts under discussion are The Rouge of the North (Chang, 1967/1998) and “The Golden Cangue” (Chang, 1971), which are currently accessible to popular readers, scholars and critics. As shown in Fig. 1, The Rouge of the North (Chang, 1967/1998) is a rewriting based on its previous versions (including “Jinsuo Ji”, Pink Tears, The Rouge of the North, and Yuannü), while “The Golden Cangue” (Chang, 1971) is a direct translation from “Jinsuo Ji”.

A series of differences between the two texts are effected due to the continuous textual developments. For example, regarding the initial publication date, The Rouge of the North is prior to “The Golden Cangue”. Meanwhile, the storyline of The Rouge of the North slightly deviates from that of “The Golden Cangue”. In addition, The Rouge of the North (55,831 words) is much longer than “The Golden Cangue” (21,461 words).

Despite the above-listed differences, The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue” share similarities in two major aspects. First, there is a high level of consistency in characters between the two texts (see Table 1). Both texts are centred on a female character, named Chai Yindi in The Rouge of the North and Ts’ao Ch’i-ch’iao in “The Golden Cangue”. The two texts embed the protagonists into similar family relationships. Male relatives in both texts include husband, son, brother, Eldest Master, Third Master, and Ninth Old Master, while female relatives include mother-in-law, Eldest Mistress, Third Mistress, daughters-in-law, and so on.

The second major similarity between the two texts lies in the plot. The protagonist got married, through an arranged marriage, to Second Master, a disabled son of a rich family. Suffering from marital dissatisfaction, the protagonist had an affection for her brother-in-law, Third Master. After the death of her husband and mother-in-law, the protagonist became the mistress of her own family. When she found Third Master attempted to defraud her of her money by taking advantage of her affection, she broke her illusion and drove him away. Afterwards, with her worsening madness, she even destroyed the chances of happiness for her children, as compensation for her own unhappiness.

The textual relationships and similarities between The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue” serve as the basis of comparison, and arouses our attention to the issue of how characters are constructed in those two inter-related texts.

Procedures

For a systemic and objective investigation of the two texts, a corpus-assisted approach is employed in the current study. Compared with traditional qualitative methods, a corpus-assisted approach offers several advantages. First, it allows for a quantitative analysis of linguistic features, providing a data-driven perspective on the texts and revealing hidden patterns or trends that might be overlooked in a qualitative analysis. Second, the use of computational tools and standardised procedures in a corpus-assisted approach ensures the reliability and validity of the findings. Third, a corpus-assisted approach can help identify subtle linguistic differences between texts which might be difficult to detect through qualitative methods. By adopting a corpus-assisted approach, this study aims to contribute to the growing body of research that builds on the strengths of quantitative methods to gain new insights into literary writings, translation and characterisation, which may, further, lead to a more nuanced understanding of fictional character construction.

Specifically, we constructed two corpora based on the electronic versions of the two texts under discussion. With the assistance of MAXQDA 2022 (VERBI Software, 2021), we manually coded the direct speech of each character in both texts, and attributed the label of a specific character to each piece of direct speech (see Fig. 2). The coding work served as the basis of follow-up analysis.

The research procedures are as follows:

(1) Extract the coded segments from MAXQDA 2022 (VERBI Software, 2021), create a single text file for each character to contain their direct speech, and use the corpus tool WordSmith 6.0 (Scott, 2012) to generate the statistics of each text file. The generated statistics imply the verbal prominence of each character.

(2) Use Code Relations Browser tool of MAXQDA 2022 (VERBI Software, 2021) to display the proximity relations between the coded segments. The type of analysis is set as “proximity of codes in the same document,” and the maximal distance is defined within one paragraph. The generated code map represents the verbal interactions between different characters.

(3) Upload the files of protagonists’ direct speech to Wmatrix5 (Rayson, 2008) for part-of-speech tagging and semantic field annotation, and use the web-based tools of Wmatrix5 to generate frequency lists as well as key grammatical and semantic categories (loglikelihood >6.63, p < 0.01, frequency ≥3). The generated results reveal the linguistic features in the two protagonists’ direct speech.

Results

Statistics of characters’ direct speech

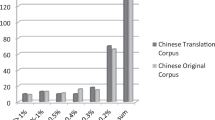

Tables 2 and 3, respectively, display the statistics of characters’ direct speech in The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue”, including speech length (number of tokens), proportion (compared to the direct speech of all characters), and normalised speech length (per 1000 words of the whole text).

As shown in Table 2, in terms of speech length and proportion, the top five prominent characters in The Rouge of the North are Yindi (the protagonist, 5941 words, 50.33%), Third Master (third brother-in-law, 1641 words, 13.90%), Bingfa’s wife (sister-in-law, 1024 words, 8.68%), Third Mistress (third sister-in-law, 688 words, 5.83%), and Old Mistress (mother-in-law, 524 words, 4.44%). Meanwhile, periphery characters with little or no direct speech include the Elder daughter of Big Master (daughter of Eldest Brother-in-law), Ahmei (niece), Big Master (eldest brother-in-law), Yensheng’s wife (daughter-in-law), and Dungmei (daughter-in-law).

According to Table 3, based on speech length and proportion, the top five prominent characters in “The Golden Cangue” are Ch’i-ch’iao (the protagonist, 3882 words, 56.53%), Chi-tse (third brother-in-law, 775 words, 11.29%), Tai-chen (eldest sister-in-law, 638 words, 9.29%), Lan-hsien (third sister-in-law, 411 words, 5.99%), and Ta-nien’s wife (sister-in-law, 194 words, 2.83%). Additionally, periphery characters who are given no direct speech are Old Mistress (mother-in-law), Eldest Master (eldest brother-in-law), Second Master (husband), Chih-shou (daughter-in-law), and Chuan-erh (daughter-in-law).

Comparing the normalised speech length of corresponding characters, there are some differences between the two texts. Specifically, the normalised speech length of all characters in The Rouge of the North (211.41) is much lower than that in “The Golden Cangue” (319.98). The most noticeable difference lies in the protagonists: the normalised speech length of Yindi (106.41) in The Rouge of the North is much lower than that of Ch’i-ch’iao (180.89) in “The Golden Cangue”. Similar increases in normalised speech length also happen to other characters such as third brother-in-law (Third Master/Chi-tse), third sister-in-law (Third Mistress/Lan-sien), and eldest sister-in-law (Big Mistress/Tai-chen). Worthy of special note is the case of Old Mistress (mother-in-law)—this character has a normalised speech length of 9.39 in The Rouge of the North, but she is deprived of direct speech in “The Golden Cangue”.

Verbal interactions between characters

Figures 3 and 4, respectively, represent the verbal interactions between the characters in The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue”. The larger the dots, the higher the frequencies of characters’ direct speech. The thicker and darker the lines, the more frequent verbal interactions between characters.

As shown in Fig. 3, verbal interactions take place between different characters in The Rouge of the North. First and foremost, the protagonist, Yindi, maintains verbal interactions with most characters. Meanwhile, among all verbal interactions, most of them occur between Yindi and her brother-in-law Third Master. Frequent verbal interactions also take place between Yindi and other characters, such as Bingfa’s wife (sister-in-law), Yensheng (son), and Second Mistress Sun (cousin-in-law), even though the latter two are not quite verbally prominent compared with other characters. Infrequent verbal interactions happen occasionally between other characters, such as Big Mistress and Third Master. Overall, there are 24 verbal interactional relationships in The Rouge of the North.

By comparison, verbal interactions in “The Golden Cangue” show another picture (see Fig. 4). Similar to Yindi, Ch’i-ch’iao has the “privilege” to have verbal interactions with most characters in the text. And her verbal interactions with Chi-tse (third brother-in-law) remain to be the most frequent. Besides, she also often verbally interacts with Ta-nien’s wife (sister-in-law), Ch’ang-an (daughter), and Ch’ang-pai (son). The mother-daughter verbal interactions between Yindi and Ch’ang-an prove to be peculiar to “The Golden Cangue”. Finally, infrequent verbal interactions take place occasionally between other characters, such as Tai-chen and Yün-tse. Altogether, those frequent and infrequent interactions between different characters contribute to 20 verbal interactional relationships in “The Golden Cangue”.

Linguistic features of protagonists: a case study

Word class analysis

Table 4 lists the top ten word classes in Yindi’s and Ch’i-chiao’s speech. Among these most frequently used grammatical categories, seven are shared by both protagonists: NN1 (singular common noun), VVI (infinitive), JJ (general adjective), II (general preposition), RR (general adverb), PPY (second-person personal pronoun), and NN2 (plural common noun). Apart from the seven shared word classes, the two protagonists differ from each other in three-word classes. Yindi in The Rouge of the North frequently uses AT (article, 3.49%), VV0 (base form of lexical verb, 3.01%) and VBZ (third-person singular of BE verb “is”, 2.99%), while Ch’i-ch’iao in “The Golden Cangue” frequently uses VM (modal auxiliary, 3.36%), XX (“not”/“n’t”, 3.2%) and PPIS1 (first-person singular subjective personal pronoun “I”, 3.17%).

Based on the frequency lists of word classes, we conducted a keyness analysis so as to know whether there are statistically significant differences between the two protagonists in grammatical categories. For the limitation of space, detailed analysis will be focused on the keyword classes whose loglikelihood values are no lower than 10.83.Footnote 3 Additionally, some representative examples extracted from both texts are provided to illustrate the differences between the protagonistsFootnote 4.

Keyword classes in Yindi’s speech

Table 5 lists the keyword classes overused by Yindi in The Rouge of the North, which includes PPHS2 (third-person plural subjective personal pronoun “they”), PPHO1 (third-person singular objective personal pronouns “him” and “her”), RT (quasi-nominal adverbs of time: “now,” “again,” “today,” “then,” “nowadays,” “before,” “tomorrow,” “now and then,” and “forever”), UH (interjections: “yes,” “oh,” “huh,” “no,” “ai-ya,” “aw,” “ai-yo,” “hey,” and “ah”), and NP1 (singular proper nouns: “Buddha,” “Wong Ji,” “Li,” “Hsia,” “Little Monk,” “Shanghai,” “Dungmei,” etc.).

Among the above keyword classes overused in Yindi’s speech, PPHS2 (LL > 15.13, p < 0.0001) and PPHO1 (LL > 10.83, p < 0.001) prove to be the most prominent ones, compared with the other grammatical categories.

Appendices A and B respectively show the concordances of PPHS2 and PPHO1 in Yindi’s speech (character width = 100). In most cases, rather than referring to a specific group or person, Yindi uses “they” to refer to a third party in general (e.g. “Nowadays they don’t marry early” in Concordance 7 of Appendix A), and uses “him” or “her” to refer to a certain person (e.g. “If you’re going to be like him I’d rather have you dead” in Concordance 39 of Appendix B). In addition, it is noticeable that the pattern “they say” (and its relevant forms) recurs in many concordances of Appendix A. This shows that Yindi prefers to talk about a third party or person and sometimes makes reference to the utterances of an unspecific group.

Example 1

The Rouge of the North:

‘The Wong sisters were the belles that day, dressed like twins,’ she went back to the birthday. ‘Did you see?’

‘I saw,’ he mumbled boredly. They were his prettiest cousins and laughed at people more than any of the others. The very mention of Second Aunt and Cousin Yensheng and they collapsed backwards and forwards laughing.

‘These two—no father, no mother, live with an aunt so they’d have somebody to look after them. Even if the widow lady doesn’t benefit by it you’d think at least she’d save a little. Huh! Always squealing for Aunt to stand them treats. And Sixth Mistress Wong is pitiful now, really has to pinch and save. She’s supposed to keep the young ladies company in sewing, embroidering and going out, keep an eye on them. Of course it’s Aunt who pays at theatres and restaurants, can’t let the children pay. Small advantages mean a lot to these rich girls. When boy friends give them presents, the more expensive the more they like it. The boys are willing to invest too and poor Sixth Mistress Wong dies of fright. Just shocking goings on she says.’

‘As if that lady can control them,’ he snickered blushing.

‘Such skinflints already at their age and always sneering at people—not a sign of longevity, although I shouldn’t say this. Both their parents died of tuberculosis.They all have it.’

‘They do?’ He sounded shaken.

‘Why not? Only they don’t like to mention it. In all fairness though, but for this illness in the family they wouldn’t be so well off either. That’s why they’re the only Wongs that have money. Their father didn’t get to spend it. They said our second branch has no man. We’re lucky to have no man.’

They had one now. It struck her the minute the words were out of her mouth but he didn’t seem to notice. He was still in a rosy glow, shy and happy. (Chang, 1967/1998, pp. 153–154)Footnote 5

Example 1 shows a dialogue between Yindi and her son Yensheng. In this passage, Yindi uses “they” with three main implications. First, when Yindi says “These two—no father, no mother, live with an aunt so they’d have somebody to look after them” and “the more expensive the more they like it,” “they” specifically refers to the Wong sisters. In her description, Yindi reveals her disdain and dissatisfaction towards the Wong sisters. Second, when mentioning that the Wong sisters’ parents died of tuberculosis, Yindi says “They all have it.” In this context, “they” refers to the entire Wong family. Although Yindi does not explicitly state it, she seems to be implying that the Wong sisters may also have inherited this disease, with a hint of schadenfreude in her tone. Third, when Yindi mentions, “They said our second branch has no man,” “they” refers to other people in general who have gossiped about Yindi and her husband having no son in the past. By quoting others’ words and adding “We’re lucky to have no man,” Yindi implies her contempt for such gossip. In summary, the frequent use of “they” in Yindi’s speech reflects her sense of alienation from others: she is trying to keep some distance from the Wong sisters and the people who gossip about her. Moreover, while criticising the Wong sisters’ selfishness and opportunism, Yindi also envies them having inherited wealth from their parents. This complex mentality reflects Yindi’s contradictory personality.

Example 2

The Rouge of the North:

‘Their Little Fifth has his eyes on Pink Cloud,’ he said grinning, back to the birthday performance.

‘I saw them together after she got out of costume.’

‘She’s not much to look at offstage.’

‘She has a certain dash.’

‘Lively enough,’ he admitted and hastened to add, ‘onstage.’

‘Yes, offstage these actresses can be very stiff. Actually, they are more strictly brought up than the young ladies nowadays. They’re so afraid of their teacher. There’s also their parents, usually very old-fashioned, these northern theatre people.’

‘They have terrible burdens, the family and their own musicians, their own troupe, scores of people depending on them for a living. How much will it cost Little Fifth to retire Pink Cloud?’

‘Little Fifth won’t get her. For one thing his father won’t let him. Too much in the public eye. They generally end up as gangsters’ concubines. Theirs is a sad life too in spite of all the glory. They’re grateful when people have real feelings for them. There’s this Old Mrs Wang, she’s an opera fan. She boosted an actress, paid for her costumes and curtains and adopted her as daughter as the men do, and they say she was very filial, always coming to the house to stay. In the end she became the old lady’s son’s concubine.’ (Chang, 1967/1998, p. 155)

Example 2 shows the follow-up dialogue between Yindi and her son Yensheng. The word “they” occurs 5 times in the direct speech of Yindi, mainly used to describe the life of actresses like Pink Cloud. In the words of Yindi, actresses live a hard life since childhood (e.g. “Actually they are more strictly brought up than the young ladies nowadays,” “They’re so afraid of their teacher”), and they are bound to suffer a sad fate despite all the glory (e.g. “They generally end up as gangsters’ concubines.”) Similar to Example 1, the last occurrence of “they” refers to an unspecified group of people who have talked about the actress’s filial behaviour. This use of “they” suggests that this information comes from hearsay, rather than Yindi’s direct knowledge. Overall, the frequent use of “they” not only positions Yindi as an informed and observant character, but also allows her to maintain a certain distance from the people she talks about.

Keyword classes in Ch’i-ch’iao’s speech

By comparison, the keyword classes overused by Ch’i-ch’iao in “The Golden Cangue” show a different picture (see Table 6). Specifically, Ch’i-ch’iao’s direct speech relies on the excessive use of PPIO1 (first-person singular objective personal pronoun “me”), PPIS1 (first-person singular subjective personal pronoun “I”), and PPY (second-person personal pronoun “you”). Among them, PPIO1 (LL > 10.83, p < 0.001) and PPIS1 (LL > 10.83, p < 0.001) are much more prominent, compared with PPY (LL > 6.63, p < 0.01).

Appendix C shows the concordances of PPIO1 in Ch’i-ch’iao’s speech (character width = 100). Within the 40 concordances, the word “me” is most frequently used in the forms “for me” (6 occurrences) and “to me” (5 occurrences), which are indicative of Ch’i-ch’iao’s selfishness. Specifically, the phrases “settle it for me” (Concordance 18), “go and get Master Pai for me” (Concordance 19), “worry for me” (Concordance 27), “fill the pipe for me” (Concordance 29), “cook opium for me” (Concordance 30), as well as “grow up and win back some face for me” (Concordance 40) show that Ch’i-ch’iao is excessively concerned with her own needs and feelings, paying too much attention to herself.

Appendix D shows the concordances of PPIS1 in Ch’i-ch’iao’s speech (character Width=100). Within the 120 concordances, the word “I” is most frequently used in the forms “I’m” (14 occurrences), “I can’t” (14 occurrences), and “I’d” (12 occurrences). Specifically, by using the expression “I’m”, Ch’i-ch’iao mainly states her mentalities or emotions (e.g. “I’m afraid” in Concordances 6 and 58, “I’m full of aches and pains from anger” in Concordance 50, “I’m not worried about my daughter” in Concordance 85). By using the expression “I can’t”, Ch’i-ch’iao describes her inability in different contexts (e.g. “I can’t vouch for the others” in Concordance 21, “I can’t get over” in Concordance 30, “I can’t keep other people from talking” in Concordance 35, “I can’t stand the agitation” in Concordance 39). Additionally, the expression “I’d” is the abbreviated form of “I had” and “I would.” In the case of “I had”, Ch’i-ch’iao proposes a possible situation (e.g. “if I’d been easy to bully” in Concordance 48, “If only I’d sold it, then I wouldn’t be caught” in Concordance 70). In the case of “I would”, Ch’i-ch’iao mainly proposes a possible situation (e.g. “I’d be out of luck indeed if I had to rely” in Concordance 40, “I’d have been trampled to death long ago” in Concordance 49, “As if I’d believe you” in Concordance 64).

Example 3

The Rouge of the North:

‘Mother,’ she murmured.

Old Mistress acknowledged the greeting with a faraway ‘Hm’ at the back of the nose. She sucked at her long pipe, her sharp chin curling out from the little walnut face. She turned to her right and aimed the chin at Big Mistress. ‘We must seem like country bumpkins, getting up at dawn.’

Big Mistress and Third Mistress smiled discreetly into their handkerchiefs.

She directed her chin at Third Mistress. ‘We’re behind the times. Nowadays people no longer have shame, nothing like before.’

Nobody dared smile any more. Late rising could only mean one thing, especially with newly-weds. In her case with the bridegroom in such poor health, the bride must be really rapacious and inconsiderate. Yindi’s colour drained away instantly leaving the rouge stranded on her face like the crimson patches on a green apple. (Chang, 1967/1998, p. 34)

“The Golden Cangue”:

Lan-hsien and Yün-tse rose to ask her to sit down but Ts’ao Ch’i-ch’iao would not be seated as yet. With one hand on the doorway and the other on her waist, she first looked around. On her thin face were a vermilion mouth, triangular eyes, and eyebrows curved like little hills. She wore a pale pink blouse over narrow mauve trousers with a flickering blue scroll design and greenish-white incense-stick binding. A lavender silk crepe handkerchief was half tucked around the wrist in one narrow blouse sleeve. She smiled, showing her small fine teeth, and said, “Everybody’s here. I suppose I’m late again today. How can I help it, doing my hair in the dark? Who gave me a window facing the back yard? I’m the only one to get a room like that. That one of ours is evidently not going to live long anyway, we’re just waiting to be widow and orphans—whom to bully, if not us?” (Chang, 1971, p. 144)

Example 3 shows two excerpts extracted, respectively, from The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue”, describing the situation in which the protagonist is late for meeting Old Mistress (mother-in-law) in the morning.

Yindi’s only speech is a murmured “Mother,” a simple greeting to Old Mistress. She remains quiet as Old Mistress makes pointed remarks about her lateness. Yindi’s silence and the description of her “colour drain[ing] away instantly” suggest that she feels ashamed of her lateness. Her lack of verbal response and the use of passive language (“leaving the rouge stranded on her face”) presents her as a submissive character who is unable or unwilling to defend herself.

In contrast, Ch’i-Ch’iao’s speech is lengthy, assertive, and unapologetic. One of the most noticeable aspects of her speech is the repeated use of “I” and “me”, the function of which is multi-faceted. To begin with, by emphasising “I” and “me,” Ch’i-Ch’iao ensures that she herself is the focus of attention, despite her lateness. Meanwhile, by saying “How can I help it, doing my hair in the dark? Who gave me a window facing the back yard? I’m the only one to get a room like that.”, Ch’i-Ch’iao provides reasons for her lateness and portrays herself as a victim of unfair treatment, shifting the blame away from herself and onto external factors. Overall, the frequent use of “I” and “me” asserts Ch’i-Ch’iao’s presence, justifies her lateness, and highlights the unfairness she suffers.

Example 4

The Rouge of the North:

‘Ninth Old Master, this is too hard on us.’ In the sudden silence, her woman’s voice sounded unnaturally thin, flat as a razor-blade. ‘In times like these, a war every year, it’s difficult to get money from the land up north. Houses also have to be in Shanghai to be worth anything. As Ninth Old Master said the second branch has no man. A woman is a crab without legs and the child is still little. There’re long years ahead. What’s to become of us?’ (Chang, 1967/1998, p. 95)

“The Golden Cangue”:

Ch’i-ch’iao suddenly cried out, “Ninth Old Master, this is too hard on us.”

…

“‘Even brothers settle their accounts openly,’” Ch’i-ch’iao quoted. “Eldest Brother and Sister-in-law say nothing, but I have to toughen my skin and speak out this once. I can’t compare with Eldest Brother and Sister-in-law. If the one we lost were able to go out and be a mandarin for a couple of terms and save some money, I’d be glad to be generous, too—what if we cancel all the old accounts? Only that one of ours was pitiful, ailing and groaning all his life, never earned a copper coin. Left us widow and orphans who’re counting on just this small fixed sum to live on. I’m a crab without legs and Ch’ang-pai is not yet fourteen, with plenty of hard days ahead.” Her tears came down as she spoke. (Chang, 1971, p. 159)

Example 4 consists of two excerpts which, respectively, show the reactions of Yindi and Ch’i-Ch’iao when they are facing unfair treatment in the division of family assets. They differ significantly in their speech and action, revealing distinct personalities.

Yindi’s speech is relatively short, simple, and objective. She uses the first-person plural pronoun “us” twice to refer to herself and her child. Her voice is described as “unnaturally thin” and “flat as a razor-blade,” suggesting a sense of weakness and vulnerability. Yindi points out a series of difficulties, including the war, the challenges of obtaining money from their northern land, and the lack of a man in their branch of the family. She uses metaphorical language (“A woman is a crab without legs”) to objectively symbolise her helplessness and the long, difficult journey ahead for her and her child. As she asks “What’s to become of us?”, Yindi is emphasising her predicament and making a plea for understanding and support.

By contrast, Ch’i-Ch’iao’s speech is longer, more complex, and more subjective. She repeatedly uses the first-person singular pronouns “I” and “me” to draw attention to herself and her situation. Specifically, by mentioning “I have to toughen my skin and speak out this once. I can’t compare with Eldest Brother and Sister-in-law”, Ch’i-Ch’iao distinguishes herself from her eldest brother and sister-in-law, highlighting the differences in their circumstances. Additionally, Ch’i-Ch’iao directly compares herself to “a crab without legs,” painting a picture of her hardships and struggles, and attempting to elicit sympathy and understanding from others. The description “Her tears came down as she spoke” further expresses her bitterness in that situation. Overall, by repeatedly referring to herself, Ch’i-Ch’iao emphasises her own difficult circumstances and insists on her own requirements.

Semantic field analysis

Table 7 lists the top ten semantic fields in Yindi’s and Ch’i-ch’iao’s speech. Among these most frequently used semantic fields, nine are shared by both protagonists: Z5 (grammatic bin), Z8 (pronoun), A3+ (existing), A6 (negative), M1 (moving, coming and going), S4 (kin), M6 (location and direction), A9+ (getting and possession), and A7+ (likely). Apart from the nine shared semantic fields, the two protagonists differ from each other in one semantic field: Yindi in The Rouge of the North frequently uses S7.1+ (power, organising; 1.53%), while Ch’i-ch’iao in “The Golden Cangue” frequently uses B1 (anatomy and physiology, 1.51%).

Based on the frequency lists of semantic fields, we conducted a keyness analysis so as to detect any statistically significant difference between the two protagonists in semantic categories. For the limitation of space, detailed analysis will be focused on the key semantic fields whose loglikelihood values are no lower than 10.83. Additionally, some representative examples are extracted from the two texts to show the protagonist’s preferences in semantic fields.

Key semantic fields in Yindi’s speech

Table 8 shows the key semantic field overused by Yindi in The Rouge of the North: S7.1+ (in power). Among all the items in this semantic field, “Master” (38 occurrences) and “Mistress” (38 occurrences) are the two most frequent ones, and other infrequent expressions include “elders” (2 occurrences), “control” (2 occurrences), “put your foot down” (1 occurrence), “force” (1 occurrence), etc. Appendix E shows the concordances of S7.1+ (in power) in Yindi’s speech (character width = 100).

As shown in Appendix E, in its close context, the word “Master” is used to refer to Third Master (21 occurrences), Ninth Old Master (7 occurrences), Big Master (5 occurrences), Second Master (4 occurrences), and Young Master (1 occurrence). It can be found that Yindi frequently refers to her brother-in-law, Third Master, instead of her husband, Second Master. As mentioned previously, the protagonist has an affection for her third brother-in-law. Yindi’s repeated references to the Third Master exactly indicate her special attention to him. Before she realises that he attempts to deceive her, Yindi has developed deep feelings for Third Master. Even after seeing through Third Master’s deceitful intentions, Yindi is still curious about Third Master’s life and asks about his information (e.g. “How is Third Master doing?”, “Third Master never comes?”, “Is Third Master using her money?”).

What is particularly interesting is the word “Mistress” which is mainly used to refer to Yindi’s mother-in-law Old Mistress (19 occurrences). Based on the expressions “If Old Mistress gets angry everybody is done” (Concordance 5), “You’ll be blamed too if Old Mistress finds out you’ve been covering up” (Concordance 10), “Old Mistress was angry” (Concordance 28), “As long as Old Mistress was here even if the sky falls down” (Concordance 37), “I want to go and explain to Old Mistress” (Concordance 38), “I’ll tell Old Mistress I’m sorry I failed the Yao ancestors” (Concordance 40), it can be concluded that Yindi regards her mother-in-law Old Mistress as an absolute authority of the big family.

Example 5

The Rouge of the North:

‘Yes, the woman always gets the blame,’ Yindi said. ‘You’ll be blamed too if Old Mistress finds out you’ve been covering up for him.’ And Third Mistress felt sickeningly certain that she would hear of it soon. ‘She’d say that you let him do whatever he likes just to please him.’

‘Yes, it’s always the wife’s fault,’ said Third Mistress.

‘Old Li, go tell Third Master that Old Mistress asked for him,’ Yindi said, half laughing. ‘We’re all in for it when it gets known that he’s gone without coming in.’

Old Li looked at Third Mistress, who dropped her eyes and jerked her head slightly towards the door. Old Li went. (Chang, 1967/1998, p. 41)

Example 5 shows the dialogue between Yindi and her sister-in-law Third Mistress. Yindi makes reference to Old Mistress for three times in this passage. The words “You’ll be blamed too if Old Mistress finds out you’ve been covering up for him” and “She’d say that you let him do whatever he likes just to please him” indicate the complex power dynamics within the family and the high expectations placed on the wives. When instructing the servant to deliver the message that “Old Mistress ask[s] for him,” Yindi invokes Old Mistress’s authority and attempts to compel the Third Master to come upstairs to meet them. Yindi’s manner (“half laughing”) in delivering the instruction adds a layer of humour and irony. It suggests that she finds amusement in the way she is compelling the Third Master to come upstairs. Such manipulation of Old Mistress’s authority can also be found in a similar situation:

Example 6

The Rouge of the North:

He shouted her down, ‘What am I to do, Second Mistress, if you insist it’s not enough? And what if there’s really not enough? If you’re to take more who’s to take less?’

She started to cry. ‘All I ask is one fair word from Ninth Old Master. Who can we turn to with Old Mistress gone? As long as Old Mistress was here even if the sky falls down there’s the tall one to hold it up with his head. Now what are we going to do, a woman with a child in tow living on some dead money, with just outgoings and none coming in.’

He jumped up. ‘I wash my hands of the whole business.’ He kicked the marble-inlaid armchair over with a crash and walked out.

The men looked at one another up and down the table, except for the two brothers slumped in their seats, avoiding everybody’s eyes. Then they all got up and hurried after him.

She sat there crying. ‘My husband, dear person, how cruel you are!’ she wailed. ‘Leave us all alone in the world. Poor you, never had a single happy day when you were alive. Whatever you did wrong in other lives you paid for it. Haven’t you suffered enough, your son has to be trampled down too? What sins were they that you never finish paying for, dear person?’

Old Mr Chu was the only one who stayed. He could not leave his valuable account books and it would be rude for him to just walk away. ‘Second Mistress. Second Mistress,’ he pleaded.

‘I want to go and explain to Old Mistress, her spirit can’t be so far away yet. I’ll catch up with her. Where’s Little Monk? I’ll take him with me to kotow to Old Mistress. His father’s only seed and I had to stand there and see him get trodden down. I’ll tell Old Mistress I’m sorry I failed the Yao ancestors, I’ll ram my head against the coffin and follow Old Mistress.’ (Chang, 1967/1998, pp. 96–97)

In Example 6, Yindi frequently mentions Old Mistress when faced with unfair division of family assets. The references to Old Mistress serve several purposes. In the beginning, the repeated mentions of Old Mistress (e.g. “Who can we turn to with Old Mistress gone? As long as Old Mistress was here, even if the sky falls down, there’s the tall one to hold it up with his head”) suggests Yindi’s strong dependence on the absolute authority of Old Mistress, a figure who is able to maintain the stability of the family. Besides, by frequently mentioning Old Mistress (e.g. “I want to go and explain to Old Mistress”, “I’ll take him with me to kotow to Old Mistress”, “I’ll tell Old Mistress I’m sorry I failed the Yao ancestors”), Yindi seems to believe that the spirit of deceased Old Mistress can still influence the family’s affairs. Thus, Yindi attempts to appeal to a higher authority who can help her secure the resources for herself and her child. What’s more, Yindi’s references to Old Mistress, combined with her dramatic declarations (e.g. “I’ll catch up with her,” “I’ll ram my head against the coffin and follow Old Mistress”) and emotional outbursts (e.g. “She started to cry,” “She sat there crying”), can be seen as another form of manipulation. By constantly invoking the memories of the deceased matriarch and threatening to take extreme actions, Yindi is attempting to impose pressure on others and make them comply with her demands.

Key semantic fields in Ch’i-ch’iao’s speech

In comparison, Ch’i-ch’iao in “The Golden Cangue” overuses a different set of key semantic fields in her speech (see Table 9), which includes A7+ (likely), I2.2 (business: selling), B1 (anatomy and physiology), and A5.3− (evaluation inaccurate). The use of A7+ and I2.2 (LL > 10.83, p < 0.001) is much more prominent and will be analysed in detail.

Appendix F lists the concordances of A7+ (likely) in Ch’i-ch’iao’s speech (character width = 100). The most frequent node words include “’d” (24 occurrences), “can’t” (19 occurrences), “can” (16 occurrences), and “could(n’t)” (16 occurrences). Those modal verbs are repeatedly used after the first-person singular subjective personal pronoun “I”. For example, “I can’t”, mainly expressing Ch’i-ch’iao’s inability in many contexts, is used in 14 concordances; “I’d”, mainly expressing Ch’i-ch’iao’s preference or willingness, is used in 10 concordances. This further shows that Ch’i-ch’iao places excessive focus on herself rather than anyone else.

Example 7

“The Golden Cangue”:

Ts’ao Ta-nien said, “Listen to a word from me, Sister. Having your own family around makes it a little better anyhow, and not just now when you’re unhappy. Even when your day of independence comes, the Chiangs are a big clan, the elders keep browbeating people with high-sounding words, and those of your generation and the next are like wolves and tigers, every one of them, not a single one easy to deal with. You need help too for your own sake. There will be times aplenty when you could use your brother and nephews.”

Ch’i-ch’iao made a spitting noise. “I’d be out of luck indeed if I had to rely on your help. I saw through you long ago—if you could fight them, the more credit to you and you’d come to me for money; if you’re no match for them you’d just topple over to their side. The sight of mandarins scares you out of your wits anyway: you’ll just pull in your neck and leave me to my fate.” (Chang, 1971, pp. 154–155)

Example 7 shows a dialogue between Ch’i-ch’iao and her brother Ts’ao Ta-nien when he visits her. After her brother mentions the importance of family support, Ch’i-ch’iao responds with frequent use of “would” (’d) and “could.” By saying “I’d be out of luck indeed if I had to rely on your help,” Ch’i-ch’iao suggests that it would be disastrous if she relies on her brother’s support. Such lack of trust in her brother is further expressed in the description of a hypothetical situation: if her brother were to fight the Chiangs successfully, he would definitely come to her for financial support; if he were unable to stand up to the Chiangs, he would readily switch sides and abandon her. Such a description indicates that Ch’i-ch’iao knows that relying on her brother’s help would be a highly undesirable and unfortunate circumstance for her. Overall, the use of “’d” (would) and “could” reveals Ch’i-ch’iao’s scepticism, distrust, as well as sarcasm.

Appendix G lists the concordances of I2.2 (business: selling) in Ch’i-ch’iao’s speech (character width = 100). The lemmas “sell” (8 occurrences) and “buy” (4 occurrences) prove to be the most frequent words in this semantic field. Actually, the words such as “sell,” “buy,” “sold” mainly occur in the dialogue between Ch’i-ch’iao and her third brother-in-law:

Example 8

“The Golden Cangue”:

Ch’i-ch’iao seemed to be making conversation. “How are you getting on with the houses you were going to sell?”

Chi-tse answered as he ate, “Some people offered eighty-five thousand; I haven’t decided yet.”

Ch’i-ch’iao paused to reflect. “The district is good.”

“Everybody is against my getting rid of the property, says the price is still going up.”

Ch’i-ch’iao asked for more particulars, then said, “A pity I haven’t got that much cash at hand, otherwise I’d like to buy it.”

“Actually there’s no hurry about my property, it’s your land in our part of the country that should be gotten rid of before long. Ever since we became a republic it’s been one war after another, never missed a single year. The area is so messed up and with all the squeeze—the collectors and bookkeepers and the local powers—how much do we get when it comes to our turn, even in a year of good harvest? Not to say these last few years when it’s either flood or drought.”

Ch’i-ch’iao pondered. “I’ve done some calculating and kept putting it off. If only I’d sold it, then I wouldn’t be caught short just when I want to buy your houses.”

“If you want to sell that land it had better be now. I heard Hopeh and Shantung are going to be at war again.”

“Who am I to sell it to in such a hurry?”

He said after a moment of hesitation, “All right, I’ll see if I can find out for you.”

Ch’i-ch’iao lifted her eyebrows and said, smiling, “Go on! You and that pack of foxes and dogs you run with, who is there that’s halfway reliable?”

Chi-tse dipped a dumpling that he had bitten open into the little dish of vinegar, taking his time, and mentioned a couple of reliable names. Ch’i-ch’iao then seriously questioned him in detail and he set his answers out tidily, evidently well prepared.

Ch’i-ch’iao continued to smile but her mouth felt dry, her upper lip stuck on her gum and would not come down. She raised the lidded teacup to suck a mouthful of tea, licked her lips, and suddenly jumped up with a set face and threw her fan at his head. The round fan went wheeling through the air, knocked his shoulder as he ducked slightly to the left, and upset his glass. The sour plum juice spilled all over him.

“You want me to sell land to buy your houses? You want me to sell land? Once the money goes through your hands what can I count on? You’d cheat me—you’d cheat me with such talk—you take me for a fool—” She leaned across the table to hit him, but P’an Ma held her in a desperate embrace and started to yell. Ch’iang-yün and the others came running, pressed her down between them, pleaded noisily. Ch’i-ch’iao struggled and barked orders at the same time, but with a sinking heart she quite realised she was being foolish, too foolish, she was making a spectacle of herself. (Chang, 1971, pp. 164–165)

Example 8 presents the dialogue between Ch’i-ch’iao and her third brother-in-law, Chi-tse, concerning his houses and her land. It is an excerpt that shows the biggest conflict between the two characters in the story. At the beginning of the dialogue, Ch’i-Ch’iao initiates the conversation by asking about the selling price of Third Master’s houses (“How are you getting on with the houses you were going to sell?”) and expresses that if she had enough cash on hand, she would consider buying them (“A pity I haven’t got that much cash at hand, otherwise I’d like to buy it.”). When Chi-tse suggests that Ch’i-Ch’iao sell her land, she doesn’t immediately agree; instead, she carefully asks for details and weighs the pros and cons (“If only I’d sold it, then I wouldn’t be caught short just when I want to buy your houses.” “Who am I to sell it to in such a hurry?”). After Chi-tse proposes to help Ch’i-Ch’iao find a buyer for her land, she questions his relationships and credibility (“Go on! You and that pack of foxes and dogs you run with, who is there that’s halfway reliable?”). When realising that Chi-tse is misleading her into selling her land and buying his houses, Ch’i-Ch’iao flies into a rage and sharply questions, “You want me to sell land to buy your houses? You want me to sell land?” She points out his deceitful intentions, accuses him of cheating her and taking her for a fool, and even tries to hit him. This reaction shows Ch’i-ch’iao’s strong opposition to Chi-tse’s proposal. She does not truly want to buy his houses or sell her land, and her inquiries are merely a way of maintaining the conversation and probing into his real intentions. Overall, the frequent use of “sell” and “buy” in Ch’i-Ch’iao’s speech, together with the tone of sarcasm, shows that Ch’i-Ch’iao has suspicion and distrust of her third brother-in-law and that she is reluctant to entrust property transactions to him.

Discussion

Verbal prominence of characters

As indicated by Tables 2 and 3, The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue” show similar but not identical patterns in characters’ verbal prominence. Seen from speech length and proportion, to start with, both protagonists are foregrounded through the use of direct speech, with Yindi in The Rouge of the North and Ch’i-Ch’iao in “The Golden Cangue” having the largest proportion of direct speech among all the characters. Apart from protagonists, three characters prove to be verbally prominent in both texts: Third Master/Chi-tse (third brother-in-law), Third Mistress/Lan-sien (third sister-in-law), and Bingfa’s wife/Ta-nien’s wife (sister-in-law). Moreover, some periphery characters exist in both texts. For example, Big Master/Eldest Master (first brother-in-law), Yensheng’s wife/Chih-shou (daughter-in-law), and Dungmei/Chuan-erh (daughter-in-law) are given no direct speech and are also rarely described in both texts.

Regarding the normalised speech length of corresponding characters, differences emerge between the two texts. Generally speaking, direct speech takes up a rather smaller part in The Rouge of the North (211.41) than in “The Golden Cangue” (319.98). That means The Rouge of the North tends to decrease the immediacy of characters in direct speech, while “The Golden Cangue” prefers to make characters more “visible” verbally. Specifically, some corresponding characters (such as Yindi/Ch’i-ch’iao, Third Master/Chi-tse, Third Mistress/Lan-sien, and Big Mistress/Tai-chen) are verbally less prominent in The Rouge of the North than in “The Golden Cangue”. Yet there are also exceptions. For example, Old Mistress (mother-in-law), the fifth most prominent character in The Rouge of the North, is prevented from having direct speech in “The Golden Cangue”. Such a contrast implies that the authority of the rich family—Old Mistress—is characterised in different ways in the two texts: in “The Golden Cangue”, Old Mistress’s image is indirectly portrayed through her absence and silence; by comparison, in The Rouge of the North, with a greater presence of her direct speech, Old Mistress is constructed into a more well-rounded and vivid character.

Verbal interactional relationships between characters

As suggested by Figs. 3 and 4, The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue” show some similarities as well as differences in characters’ verbal interactional relationships. First, both protagonists maintain verbal interactional relationships with most characters in the text. By initiating and maintaining most verbal interactions in the text, the protagonists naturally lie in the “centre” of the verbal interactional network.

Second, in both texts, the strongest verbal interactional relationship is established between the protagonist (Yindi/Ch’i-ch’iao) and her third brother-in-law (Third Master/Chi-tse), given their most frequent verbal interactions.

Third, the verbal interactional relationships in The Rouge of the North (24 lines in Fig. 3) show a higher degree of complexity than those in “The Golden Cangue” (20 lines in Fig. 4). That means, more characters in The Rouge of the North are involved in verbal interactions. For example, the protagonist Yindi in The Rouge of the North has verbal interactions with the Second Master (husband) and Old Mistress (mother-in-law), while the protagonist Ch’i-ch’iao in “The Golden Cangue” has no verbal interactions with those two characters. These exclusive dialogues in The Rouge of the North indicate power dynamics in the feudal society, providing an overall background and an immediate context for the readers to better understand the changes in the protagonist’s personalities.

Fourth, some secondary verbal interactional relationships are formed differently between the protagonist and other characters. The most important difference between the two texts lies in the mother-daughter interaction. In The Rouge of the North, the protagonist Yindi has no daughter, and thus the mother-daughter interaction does not exist at all. In stark contrast, “The Golden Cangue” creates frequent verbal interactions between the protagonist Ch’i-ch’iao and her daughter Ch’ang-an, which are mainly used to show Ch’i-ch’iao’s complete control over her daughter and the consequential mother-daughter conflict.

Linguistic preferences and implied characteristics of the two protagonists

Yindi in The Rouge of the North

In her direct speech, Yindi is found to have a particular preference for the third-person plural subjective personal pronoun “they”, third-person singular objective personal pronouns “him” and “her”, as well as the semantic field S7.1+ (in power).

The excessive use of “they,” “him,” and “her” in Yindi’s speech implies her sense of alienation on the one hand, and reflects her inner loneliness on the other. As indicated by Examples 1 and 2, whether judging the Wong sisters (e.g. “When boy friends give them presents, the more expensive the more they like it”), describing the actresses (e.g. “They generally end up as gangsters’ concubines”), or quoting others’ gossip (e.g. “they say she was very filial”) (Chang, 1967/1998, p. 153, p. 155), Yindi always stands from the perspective of an observer. She maintains a critical distance from the people she talks about, rarely expressing a sense of connection with them. This detachment is further revealed by her frequent use of “him” and “her” (e.g. “It’s torture for him to live, he’d be better off dead”) (Chang, 1967/1998, p. 83), which strengthens the barrier between herself and the subjects of she observes. However, this very act of distancing herself from others ultimately underscores Yindi’s loneliness. Her sharp perception of others’ life and her eagerness to judge the people around her, in turn, reveal her feelings of isolation and vulnerability.

Additionally, Yindi’s preference for the semantic field S7.1+ (in power) is attributed to the frequent mentions of “Third Master” and “Old Mistress” in her speech. The repeated references to Third Master in Yindi’s speech indicate her longing for intimate relationships. Married to Second Master who is blind and has “the soft bone disease” (Chang, 1967/1998, p. 73), Yindi fails to develop or enjoy intimate relationships in her own marriage. Instead, she has an affection for her brother-in-law Third Master. As described in the novel, “When she saw Third Master coming it suddenly seemed endless like the repetitious vista in a mirror facing another mirror. […] He seemed to come miles towards her looking at her, smiling. She could only talk to the baby in her embarrassment.” (Chang, 1967/1998, pp. 79–80) Yindi pays special attention to Third Master and is deeply attracted by him. By frequently referring to Third Master in her speech, Yindi expects to have more interactions with him. For example, Yindi proposes to “Wait till Third Master gets up” to play mahjong together (Chang, 1967/1998, p. 37). Even after she sees through Third Master’s deceitful intentions, she still attempts to know more about him by asking “How is Third Master doing?” (Chang, 1967/1998, p. 137). All those references bear Yindi’s complex feelings for Third Master and thus indicate her longing for intimate relationships.

What is more interesting is that Old Mistress is mentioned many times in Yindi’s speech, which serves several purposes in the text. For one thing, as suggested by Examples 5 and 6, frequent references to Old Mistress underscore the significant role she plays within the household as well as the complex power dynamics in a traditional family. Even after the death of Old Mistress, such influence persists, as described in the novel: “She kept to Old Mistress’s ways in everything except for her mouthful of smoke” (Chang, 1967/1998, p. 121). For another, by constantly mentioning Old Mistress, Yindi attempts to take advantage of Old Mistress’s authority. Especially when faced with unfair treatment, she does not hesitate to achieve her goals by using emotional manipulation (e.g. “I want to go and explain to Old Mistress, her spirit can’t be so far away yet”) (Chang, 1967/1998, p. 97). This indicates that Yindi relies heavily on the persisting influence of Old Mistress. In this sense, it can be said that Yindi respects family hierarchy and sticks to traditional moral and ethical values. Additionally, the repeated references to Old Mistress also reveal Yindi’s helplessness in complex power dynamics: she has no other choice but to appeal to the influence of a deceased authority.

Ch’i-ch’iao in “The Golden Cangue”

Ch’i-ch’iao’s direct speech is highlighted by the overuse of the first-person singular objective personal pronoun “me”, first-person singular subjective personal pronoun “I”, as well as the semantic fields A7+ (likely) and I2.2 (business: selling).

The frequent use of “I” and “me” by Ch’i-Ch’iao in her speech reveals that she is characterised as being self-centred and paying excessive attention to herself. As shown in Example 3, when she is late for meeting her mother-in-law in the morning, she imputes her lateness to external factors such as “a window facing the back yard”, and complains that “I’m the only one to get a room like that” (Chang, 1971, p. 144). Similarly, when she is dissatisfied with the solution in the division of family assets, she emphasises her difficult circumstances (e.g. “I’m a crab without legs”) (Chang, 1971, p. 159) and voices her own demands. By overusing “I” and “me”, Ch’i-Ch’iao is only concerned with her own wants and needs and never thinks about other people, her children included. Such self-centredness is most reflected in her pursuit of money and particular care of her property. As described at the end of the novella, Ch’i-Ch’iao is trapped in the “golden cangue” she wears: “For thirty years now she had worn a golden cangue. She had used its heavy edges to chop down several people; those that did not die were half killed.” (Chang, 1971, p. 190) Out of her self-centredness, Ch’i-Ch’iao uses the “golden cangue” to attack anyone who may take her property, which finally makes herself alienated by all others, as described in the novella: “She knew her son and daughter hated her to the death, that the relatives on her husband’s side hated her, and that her own kinsfolk also hated her.” (Chang, 1971, p. 190)

Meanwhile, the overuse of modal verbs such as “would,” “can’t,” “can,” and “could” in the semantic field A7+ (likely) implies Ch’i-Ch’iao’s feelings of insecurity, uncertainty and helplessness. As indicated by Example 7, Ch’i-Ch’iao refuses to rely on the support of her brother by saying “if you could fight them, the more credit to you and you’d come to me for money; if you’re no match for them you’d just topple over to their side” (Chang, 1971, p. 155). Similarly, in Example 8, Ch’i-Ch’iao points out Chi-tse’s tricky scheme by saying, “Once the money goes through your hands what can I count on? You’d cheat me—you’d cheat me with such talk—you take me for a fool.” (Chang, 1971, p. 165) The modal verbs “would,” “could,” and “can” in her speech show that Ch’i-Ch’iao lacks confidence in the people surround her (such as her brother), believing that they all come for her money or land. At a deeper level, Ch’i-Ch’iao’s feelings of insecurity and uncertainty mainly stems from her helplessness in her life, as expressed by the phrases “I can’t” or “I couldn’t”. She directly expresses her helplessness by complaining to her brother: “You have ruined me well and good. You walked away just like that, but I couldn’t leave. You don’t care if I live or die.” (Chang, 1971, p. 153) Such feelings of helplessness deepen after the death of her husband and mother-in-law, since she has to rely on herself to raise her children, as said by Ch’i-Ch’iao herself: “Left us widow and orphans who’re counting on just this small fixed sum to live on.” (Chang, 1971, p. 159) It should be noted that Ch’i-Ch’iao’s feelings of insecurity, uncertainty and helplessness also explain her later determination to protect her own interests.

Besides, the frequent use of such words as “sell” and “buy” in the semantic field I2.2 (business: selling) implies Ch’i-Ch’iao’s distrust of intimate relationships and her determination of protecting her own interests. The words “sell” and “buy” are mainly used in Ch’i-Ch’iao’s conversation with her third brother-in-law Chi-tse. By actively enquiring about Chi-tse’s houses and expressing that she would consider purchasing them if she had sufficient cash, Ch’i-ch’iao is actually intending to probe into Chi-tse’s real intentions. Despite her special feelings for Chi-tse, Ch’i-ch’iao does not easily believe him, as described in the novella: “No, she could not give this rascal any hold on her. The Chiangs were very shrewd; she might not be able to keep her money. She had to prove first whether he really meant it.” (Chang, 1971, p. 164) This shows Ch’i-Ch’iao’s suspicions of intimate relationships. After discovering Chi-tse’s deceitful intentions, Ch’i-Ch’iao adopts an aggressive and defensive attitude to protect her own property. Particularly, by asking “You want me to sell land to buy your houses? You want me to sell land?” (Chang, 1971, p. 165), Ch’i-Ch’iao uses the words “sell” and “buy” within the same context to create a juxtaposition, which not only highlights the apparent absurdity of Third Master’s proposal, but also expresses Ch’i-Ch’iao’s strong opposition and sarcasm.

Conclusion and implications

Taking direct speech as an indicator of character portrayal, this study adopts a corpus-assisted approach to characterisation in The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue”. The results show that there are subtle yet definite differences in character portrayal between The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue”. First, in shaping characters’ verbal prominence, both texts tend to foreground their protagonists (among all the characters), but many characters (particularly the protagonist) in The Rouge of the North are assigned a much lower degree of verbal prominence than those in “The Golden Cangue”. Second, in terms of characters’ verbal interactional relationships, the relationships between the characters in The Rouge of the North are more complex than those in “The Golden Cangue”, and, meanwhile, such relationships are presented differently in the two texts. Third, with regard to linguistic features, the protagonist Yindi in The Rouge of the North and the protagonist Ch’i-ch’iao in “The Golden Cangue” have distinctive grammatical and semantic preferences in their speech, and thus they exhibit different characteristics.

It should be noted that the current study is a tentative exploration into the characterisation of corresponding characters in two inter-related literary texts. As explained before, both The Rouge of the North and “The Golden Cangue” are produced by the renowned Chinese writer Eileen Chang, the latter being a direct translation, while the former is more of a rewriting. By their very nature, the two texts are actually two versions of the same story. Corresponding characters (e.g. Yindi in The Rouge of the North and Ch’i-ch’iao in “The Golden Cangue”) in the two texts are constructed in subtly different ways through direct speech. It still requires further explanation as to why Eileen Chang made many changes in the two texts when constructing those corresponding characters.

This study demonstrates the potential of a corpus-assisted approach in the study of characterisation. Regarding the characters in a particular literary text, even less obvious and less easily observable features have an accumulative and decisive effect in characterisation (Culpeper, 2002a, p. 11; 2014b, pp. 9–10; 2014a, p. 37). A corpus-assisted approach helps discover regular patterns in texts and also unveil those less obvious and less easily observable features in language use. Based on the recurring linguistic features extracted by corpus tools, it is easier to analyse the accumulative effect of linguistic features on character construction. In addition, although some non-controverted notions about characterisation have been formed on a fairly firm basis and widely accepted by literary critics long before (see Garvey, 1978, pp. 66–68), the study of characterisation needs to incorporate new perspectives and approaches to confirm or falsify those previous notions. In the future, it is advisable to integrate the corpus-assisted method with other methods and establish a multi-disciplinary approach to characterisation, combining the insights from corpus linguistics, digital humanities, narratology, stylistics, pragmatics, and so on.

Meanwhile, this study also has some implications for the multi-faceted role played by direct speech in constructing fictional characters. Compared with indirect speech and free indirect speech, direct speech seems to be the most common and simple form of speech presentation. Thus, considered as a less valuable speech form, direct speech is rarely independently investigated in corpus linguistics (Axelsson, 2009), corpus-assisted literary studies, or corpus-assisted translation studies. However, in literary texts, language variations exist not only between the narrator and the character but also between different characters. Direct speech is indeed one of the useful means to effect such variations. As argued in the current study, direct speech plays a significant role in characterisation at three levels: macro-level, meso-level, and micro-level. Specifically, direct speech suggests the verbal prominence of certain characters, establishes the verbal interactional relationships between characters, and reflects specific linguistic features peculiar to each character. Therefore, direct speech proves to be a special indicator of characterisation in literary texts. As shown in this study, when we separate direct speech from the other parts of literary texts and make an independent analysis of direct speech itself, we are able to discover the particular functions of direct speech in constructing fictional characters. On the basis of manual annotation, such work can be carried on in corpus linguistics, corpus-assisted literary studies, as well as corpus-assisted translation studies, so as to arrive at a broader conceptualisation of direct speech and a deeper understanding of characterisation.