Abstract

The constant development of internet technology in the digital age has changed the way people interact with space. To explore whether and what changes have occurred in the public’s spatial perception of the street during the shift from the traditional to the digital age, this paper compares the public’s spatial perception characteristics in the two contexts through a classical theory review and empirical coding analysis with the Xiaolouxiang historic district as an empirical case. The frameworks of public spatial perception characteristics are similar in both contexts, with a focus on the three dimensions of objects, buildings and spaces, and activities. However, compared with that in the traditional context, the public’s spatial perception of the street in the digital context of Xiaolouxiang has undergone new changes in three aspects: from focusing on the three-dimensional experience of space to focusing on the two-dimensional visual aesthetics of space, from emphasizing spatial totality to focusing on spatial details, and from focusing on the use of space to emphasizing the cultural characteristics of space. Research emphasizes that, within the context of digitalization, spatial design should place greater emphasis on visual aesthetics, detail processing, and cultural expression to better meet the needs and expectations of the public. This work identifies new features of the public’s perception of urban street space in the context of digitalization and accordingly provides suggestions for the future design of urban street space. The findings of this study not only enrich the foundational research content of spatial perception theory but also offer new perspectives for designers and planners in the practice of urban block renovation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Characteristics of public interaction with space in traditional contexts

In his discussion of the rise (and fall) of the public sphere (De Angelis 2021), the philosopher Habermas emphasized the importance of cafés in the city and the public sphere for people, mentioning that politicians not only drink coffee in cafés but also engage in conversations and formulate reflections (Laurier 2008), reflecting the fact that the existence of the café as a physical spatial form contributes to rational interactions and the formation of the public sphere. Interaction in physical space allows for new encounters and dialogues and facilitates social integration, which was the primary way in which people interacted before the advent of the information technology era (Laurier and Philo 2007). However, the advent of the information technology era has changed people’s interaction behaviours in the public sphere (China National Information Center 2020). Thompson, a British sociologist, stated that various forms of media influence today’s public sphere and are subject to various social and technological considerations (Thompson 2011).

Before the digital age (information technology era), people interacted with space in a very traditional way, where they developed a three-dimensional perception of space through multisensory interactions and the movement of their bodies through space. This perception has two main characteristics: first, people perceive space through sensory activities such as observing, listening, smelling, and touching, as well as brain activities such as imagining and remembering, so they can fully perceive factors such as texture, temperature, and sound and form emotional resonance (Rezvanipour et al. 2021; Slotkis 2020; Wen and Wang, 2012); second, people experience the path, continuity, and sense of sequence of the space by moving through the space by walking, riding, or driving.

Impact of digital technology on public space perception and interaction

Humanity has entered the digital age with the development of information interaction technology, such as the internet; portable electronic devices, such as cell phones; and online social media, such as microblogging. In the digital age, social media is involved in socializing almost daily (Procentese et al. 2019) and has changed how people interact with physical space (Schwartz and Hochman 2014). The emergence of social media and social media platforms has significantly altered our understanding of the concept of social environments, as these platforms are utilized to facilitate online communication and interaction (Weigle et al. 2024). In China, for example, the number of social media users has exceeded 1 billion by 2024 (China Daily 2024). People have domesticated “new technology” and are actively using the internet to change their daily lives (McDonald 2015).

With the creation of moveable digital platforms, people increasingly connect through online interactions (Shankardass et al. 2019). Digital media and physical urban spaces are interdependent; together, they can provide spaces for people to interact (Adams and Jansson 2012; Couldry and McCarthy 2004; Lim 2014). Specifically, the interaction between people and space in the digital era has changed in two ways. First, how people observe space has changed. In the ordinary traditional context, people mainly interact with physical space through their senses and brains. However, in the new context, people spend much of their time recording and perceiving space through digital devices such as cell phones and sharing them on social networks, forming a new way of interacting (Humphreys 2010). This portable personal media formed by mobile devices with photo, video, and networking capabilities allows people to coordinate their time, space, and sensory experiences (Kleinman 2007). Second, the way people perceive space has changed. In the ordinary traditional context, people can only visit the site to perceive a space. However, in the digital context, people can form a new source of perceiving space through instantaneous online images (Gatti and Procentese 2021). People can experience space by observing online spatial images without entering physical reality. These digital images become part of the spatial imagery that shapes and defines one’s perception of reality (Lee 2010).

The present study

Influenced by new technologies, the public’s perception of space has changed from a context based on physical space to a digital context. Human behaviour changes their environment, and these environmental changes, in turn, shape humans (Paus and Kum 2024). Therefore, in the digital context, we speculate that people’s perceptions of space may reveal new features. To this end, we propose three research questions: Have the characteristics of the public’s perception of space changed from those of the traditional period? What are the characteristics of these changes? What are the new implications for future spatial design?

We choose the street as a specific research object to explore the changes in people’s spatial perception characteristics in the digital context compared with those in the traditional context. The reason why we choose the street as the object of study is that it plays a crucial role in urban public space, not only connecting different areas but also providing a place for people to walk, gather, socialize, and engage in cultural exchanges and commercial activities through roads, buildings, stores, and small squares (Jacobs 1961). Therefore, the street is typically chosen as the object to explore the public perception of public space.

We carry out this research through the following steps: first, we analyse the research progress on the impact of the digital context on architecture and space in recent years and analyse the shortcomings of the existing research; second, we analyse the related studies on the interaction between people and physical street space to summarize the characteristics of the public’s spatial perception of the street in the ordinary traditional context; third, we use the Xiaolouxiang historic district in Wuxi (in southeastern China’s Jiangsu Province) as a case study to analyse the characteristics of the public’s spatial perception in the digital context; finally, we compare the characteristics of the public’s spatial perception of the street in the digital context of Xiaolouxiang with those in the ordinary traditional context to explore whether and how the public’s spatial perception of the street changes in the new context, as well as revelations for the future.

Literature review

Importance of the spatial perception of streets and related research

The public space is an open, publicly accessible place where people conduct group or individual activities (Carr et al. 1992). Many studies have shown that one of the results of people’s perception of public space is the creation of environmental preferences (Ho and Szubielska 2024; Kaplan 1985; Oyama 2024), which can be viewed as individual or collective social aspirations and representations (Stanko, 1995), and the fulfilment of these preferences is one of the important goals of urban planners (Dai and Zheng 2021; Q. Song et al. 2024; Wei et al. 2024). Streets are among the most essential types of spaces in urban public spaces, and they have a variety of spatial functions, including transportation, social communication, leisure, and culture (Carmona et al. 2018; Franke et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2024; Mehta 2007; R. Yang et al. 2024). This is why Kevin Lynch noted early on that streets are the dominant factor influencing the image of a city (Lynch 1960), and some scholars have even argued that the streets seem to be the city in a sense and that street life is city life (Duan et al. 2007).

The value and importance of street space are also reflected in people’s reliance on it and its ability to generate rich perceptual experiences. First, the perception of street space is strongly linked to people’s quality of life (Ma et al. 2024). For example, experiencing street space with high accessibility and social inclusiveness can contribute to public well-being (Francis et al. 2012; Moore et al. 2018; Mouratidis 2021). Second, street space perception affects people’s level of physical and mental health, and physical attributes, personal characteristics, or social factors in the space have specific effects on specific behaviours in the space, which in turn affect people’s health benefits (Angel et al. 2024). For example, some studies have noted that deteriorating street space may lead to a variety of mental health problems and even higher mortality rates (Ezeh et al. 2017; Kabisch et al. 2021). Given the importance of street space to cities and residents, research on the perception of urban street space has been a hot topic in urban research (Ma et al. 2024; Zeng et al. 2024).

Studies related to human perception in street space in traditional contexts

Research on the public perception of street space in traditional contexts mainly refers to studies on public interaction and perception in physical space before being influenced by the internet and modern communication technologies. Scholar Jack L. Nasar summarized the characteristics of street space perception research in the traditional context with a simple model in which physical environmental attributes in street space influence human cognition, emotion, or behaviour, producing various street environment benefits (Nasar 2008). In the above model, various street perception elements (environmental attributes of street space and various human characteristics) are the basis for influencing the perception results (human cognition, emotion, or behaviour); thus, previous research has often focused on finding or identifying the characteristics of various perception elements and their dimensions (Gehl 1987; Skjoeveland 2001; Targhi and Razi 2022).

As early as the 1960s, Kevin Lynch noted in his pioneering research that the five categories of paths, edges, nodes, districts, and landmarks are the main factors in the composition of urban images (Lynch 1960). This point of view highlights the main physical elements in the public perception of urban space, and it has had a profound impact on the research of various types of urban spatial perception, including street spatial perception. Subsequent scholars have continued to enrich and develop the five perceptual elements (Ashihara 1981; Edward T. Hall 1988), and Whyte, Gehl, Jacobs, and others have further reported that objects in space (tables, chairs, food, plants), as well as human activities (e.g., commercial activities, musical performances), are also important factors influencing the public’s perception of space (Gehl 1987; Jacobs 1961; Whyte 1980).

Because street space is a typical type of urban space, many characteristics of urban spaces are present in street space. Therefore, when we narrow the perspective of previous research from the study of public perceptions of urban space to the study of public perceptions of street space, we find that the public’s concerns about the spatial perceptions of streets are similar to those summarized by scholars such as Lynch, Whyte, Jan Gehl, Jane Jacobs and others concerning the public’s perceptions of urban space. The public’s concerns are still about the street space and the buildings, objects, and activities. The space and architecture of the street mainly refer to spatial nodes (with attributes such as different scales, private or shared, diverse functions, and uniqueness) (Chen et al. 2022; Targhi and Razi 2022; Tian et al. 2022), paths (with attributes such as imaginability and length) (Mehta 2007; Targhi and Razi 2022; Vichiensan and Nakamura 2021), and buildings (including architectural elements such as street-facing facades, colours, entrances, windows, and skylines) (Berto 2007; Brancato et al. 2022; Knuiman et al. 2014; Koh and Wong 2013; Mahmoudi and Ahmad 2015; Porter et al. 2018; Quercia et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2023). The objects in the street space primarily include plants (Brancato et al. 2022; Fukahori and Kubota, 2003; Kuo and Sullivan 2001; Mehta 2007; Neale et al. 2017; Quercia et al. 2014; Sung et al. 2013; Zhou et al. 2023), skyscapes (Chen et al. 2022; Zhou et al. 2023), guardrails and signage (Mehta 2007), seating (Mehta 2007; Tian et al. 2022), food (Abdulkarim and Nasar 2014b; Targhi and Razi 2022; Xie et al. 2024), display cases (Targhi and Razi 2022), awnings (Mehta 2007), trash receptacles (Mehta 2007), public artwork and sculpture (Yosifof and Fisher-Gewirtzman 2024), natural environments (e.g., sunlight, wind, water, and temperature) (Arens and Bosselmann 1989; Pushkarev 1975; Share 1978; Shi et al. 2015; Zacharias et al. 2001), streetlights (Fukahori and Kubota 2003), and vehicles (Blitz 2021; Choi et al. 2016; Ettema 2016). Kaplan, an environmental psychologist, stated that “human beings respond not only to ‘things’ but to their arrangement, and also to the inferences that make that arrangement possible” (Kaplan 1985). In street spaces, physical space properties and spatial qualities can also significantly affect people. In terms of the physical attributes of space, scholars have found accessibility (Y. Guo and He, 2021; Koh and Wong, 2013; Tao et al. 2022), physical disorder (Ashihara 1981; Mahmoudi and Ahmad 2015; Zhou et al. 2023), motorization (Blitz, 2021; Saelens et al. 2003; Szarata et al. 2017), functional diversity (Abdulkarim and Nasar 2014a; Gehl 1987; Knuiman et al. 2014; Rui and Xu 2024; Sung et al. 2013), openness (Porter et al. 2018), building density (Porter et al. 2018; Yosifof and Fisher-Gewirtzman 2024), microclimate (Tao et al. 2022), enclosure (or closure) (Ashihara 1981; Tao et al. 2022; Yosifof and Fisher-Gewirtzman 2024), and complexity to be the foci of attention (Abdulkarim and Nasar, 2014a; Zhou et al. 2023). In terms of the quality of space, scholars have reported that humanization (Quercia et al. 2014), comfort (Abdulkarim and Nasar 2014a; Edward T. Hall 1988; Jacobs 1961; Zhou et al. 2023), safety (Harcourt and Ludwig 2006; Jacobs, 1961; Koh and Wong 2013; Kuo and Sullivan 2001), friendliness (Rui and Xu 2024), and restoration influence people’s perception of the street (Berto 2007; Ettema 2016; Ho and Szubielska 2024).

In addition to space, buildings and objects, another focus of public perception in streets in traditional contexts is activity. The physical attributes of space affect a range of activities in space (Dodge et al. 2011; Hillier and Sahbaz 2008; Kirk et al. 1963). Activities in the street space primarily include a variety of physical activities (including running, walking, and biking) (Blitz 2021; Brownson et al. 2009; Ettema 2016; Koh and Wong 2013; Rui and Xu 2024; Saelens et al. 2003), socializing (Mehta 2007), recreational activities (Ho and Szubielska 2024; Mehta 2007), and supervisory activities (Harcourt and Ludwig 2006; Kelling and Wilson 1982).

The detailed literature analysis revealed two characteristics of the public’s spatial perception of physical streets in traditional contexts. First, human perceptual preferences in physical space in traditional contexts focus on buildings and spaces, objects in buildings and spaces, and activities in buildings and spaces, as shown in the subdivision map of street space perception in the traditional period in Fig. 1. Clarifying the public’s perceived preferences for the environment not only helps scholars identify important research objects but also helps urban planners clarify the focus of street reconstruction, so many studies on environmental perception have explored the public’s expectations, value choices and preferences for the environment (Kaplan 1985). Therefore, we clarify the public’s perceptual preferences for street space in traditional contexts, which is an essential foundation for exploring the public’s perceptual preferences in the digital context. Second, the public perception of street space in traditional contexts is often based on assessing real street space wholeness, utility, and experience. For example, people are very concerned about physical attributes such as functional diversity, openness, and space enclosure, which reflects their concern for the wholeness and utility of the space, and their concern for spatial qualities such as safety, comfort, and a humanized scale of the space can reflect their emphasis on the sense of experience of the space.

In terms of research methodology, the traditional approach to research the spatial perception of streets is to use onsite observations (Groenewegen et al. 2006; Neale et al. 2017; Sung et al. 2013; Tao et al. 2022), interviews or semistructured interviews (Cerin et al. 2013; Choi et al. 2016; Mahmoudi and Ahmad 2015; Mehta 2007), and questionnaires (Brancato et al. 2022; Ettema 2016; Knuiman et al. 2014; Mahmoudi and Ahmad 2015; Porter et al. 2018; Quercia et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2023). This research method often consumes much time, and an adequate sample size is relatively small (Ma et al. 2024; Wei et al. 2024). With the development of digital technology, in recent years, an increasing number of scholars have begun to study people’s perceptual preferences in street space using digitization and big data, such as research on street space using virtual technology (X. Guo et al. 2022; Wu et al. 2024), mobile application data (Angel et al. 2024; Basu and Sevtsuk 2022; Damjanović et al. 2022; De Nadai et al. 2016; Q. Song et al. 2024), street view image data (Harvey et al. 2015; Klompmaker et al. 2024; Rui and Xu 2024; Xu et al. 2018; Ye et al. 2019; Zeng et al. 2024) and multisource datasets (Ma et al. 2024; Wei et al. 2024). For example, Wang et al. developed a new method for assessing street quality on a large scale by determining a linear relationship between trip rates and the quality of the street space through a deep learning scoring model constructed using streetscape images of the Binjiang District of Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China (L. Wang et al. 2022). Although these digital methods can be used to obtain more valid sample data more quickly and conveniently than previous methods, such as onsite questionnaires, they can also be used to study the spatial perception of streets on a larger scale. However, these studies still need to be more responsive to the phenomenon that technological changes such as internet interconnectivity and instant messaging have already impacted the public’s perception of street space in the digital age.

Studies related to human perception in street space in digital contexts

With respect to the impact of internet connectivity and instant messaging on people in the digital age, many studies have collected and analysed internet data to understand the public’s perceptions of architecture and space, such as by analysing text and image data posted by users on social media to explore new directions for future spatial design. For example, Song et al. analysed the use of Seattle Freeway Park as a public space and users’ emotional connection to the park’s built environment by mining 3314 Instagram posts posted by 2035 users over three years (2015–2017), providing new perspectives and insights into public space design (Y. Song and Zhang 2020). However, we found through our literature review that most of the current studies that use social media data are studies that are based on the textual data of their posts (Li et al. 2021; P. Wang et al. 2022; C. Yang et al. 2022; Yuan et al. 2020). For example, based on the online review data of tourists released by TripAdvisor from 2010–2019, Peng et al. used content analysis to explore the differences in the public’s perception image of Beijing’s historical and cultural neighbourhoods. Research has revealed that diverse cultural groups have differences in the cognitive, affective, and overall image of historical districts; the authenticity of the district environment, public facilities, and the perception of crowding affect the place attachment of different cultural groups (Peng et al. 2022). Although it is possible to determine the public’s preference for a street space through the analysis of textual data, the public’s willingness to post text on the internet is weaker than that of pictures; thus, these short texts cannot wholly reflect the public’s perceived preference for a street space.

In recent years, several studies have analysed the impact of spatial elements on the public through image data related to the spatial perception of streets (Yilmaz and Kocabalkanli 2021). For example, using a human-generated image analysis of nearly 53,000 Instagram photos associated with Sanlitun Village in Beijing and Xintiandi in Shanghai, Qian et al. identified three roles that portals can play in space: “doorways”, “showrooms”, and “places”. The relationship between portals and places has been explored from the perspective of users’ understanding of urban space, and the characteristics of different forms of portals have been explored (Qian and Heath 2019). These studies, which use image data, are more advanced than textual analysis and can more clearly reveal the manifestation of the public’s subjective will in the street space. However, most of the studies still use a basic categorization of the overall features of the image data. The more in-depth content of individual images has yet to be coded and analysed in detail, and image data containing a large amount of information about the public’s subjectivity need to be more fully utilized. Therefore, we use NVivo software to conduct in-depth coding of images, meticulously identifying and annotating recurring themes or details within the pictures. This approach aims to thoroughly explore the characteristics of street space perception in the digital context and compare them with those in traditional contexts. We obtained image data from social media platforms because analysing social media data offers distinct advantages over traditional surveys, such as broad coverage, rapid data collection, the ability to capture emerging knowledge, low costs, wide-reaching results, and the representation of collective information (Weigle et al. 2024). We collected a total of 1119 valid images. When analysing the perceptions of our target group, we did not limit our focus to the views of local residents. Owing to the diversity of online data sources, our analysis includes perspectives from local residents and external visitors, making our findings more comprehensive.

Summary of current research

Research on the public’s perception of street space in traditional contexts has matured. Regarding the specific content of perception, the preference of human perception in physical space in traditional contexts focuses on buildings and spaces, objects in buildings and spaces, and activities in buildings and spaces. In terms of the characteristics of perception, the public’s perception of street space in traditional contexts is often based on assessing the wholeness, utility, and experiential sense of real street space.

In contrast, research on public street space perception in digital contexts is still in its infancy. There are two areas for improvement. First, few existing studies have systematically compared the characteristics of the public’s street space perception in digital and traditional contexts. Therefore, is there a new shift in the public’s spatial perception of the street in the digital context compared with the traditional context? What is the shift? Further research is needed. Second, there is still the problem of favouring textual data and lacking the full utilization of image data. In terms of existing research on textual data, although textual data can reflect the public’s preference for street space, the text posted by the public on the internet is often short and does not adequately describe the scene; therefore, these short texts cannot completely reflect the public’s perceptual preference for a space. In terms of existing research on image data, most studies still focus on a basic categorization of the overall features of the image data, and the more in-depth content of a single image still needs to be coded and analysed in detail.

Therefore, to more comprehensively and deeply understand the difference between public perception in digital and traditional contexts, we develop in-depth coding of the image data posted by the public on social media through typical cases for an in-depth exploration of the characteristics of the public’s perception of the street space in the digital context.

Research methods

We use case studies and comparative research to explore the following questions: Have digitized forms of human interaction with space led to changes in our perceptual preferences for space compared with traditional periods? What are the characteristics of these changes? What are the reasons behind these changes? What are the implications for us?

As a case study, we select Xiaolouxiang, one of Wuxi’s four central historical districts. Based on the grounded theory, we use NVivo software to code and analyse the photo data about Xiaolouxiang shared by people on Sina Weibo.

Case selection

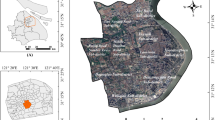

We choose Xiaolouxiang, a historical and cultural district in Wuxi, as a typical case for two reasons. First, Xiaolouxiang has a high degree of attention and popularity. It is an essential historical district space in the old urban area of Wuxi, with a history of more than 900 years, and 24 groups of historical buildings exist in the district (Zhang et al. 2010). The frequent interaction between people and the spaces that characterize the Xiaolouxiang historic district makes it ideal for studying the interaction between people and space. Second, the renovation of Xiaolouxiang was a top-down planning model dominated by the ideas of the government, developers, and a team of designers, with little participation from the community and no one to re-examine the feedback from people’s experience of the space after it was built. Therefore, we need to study the public’s spatial perception preferences from the public’s perspective and propose new design insights. The high popularity of Xiaolouxiang and its existing problems make it a typical case to be studied, and the research carried out with it is exemplary for other spatial cognition and spatial design.

The Xiaolouxiang historic district is located in the old urban area of Wuxi, spanning from Xiaolouxiang Cross Street in the east to Xinsheng Road in the west, the Municipal Public Security Bureau in the south, and Futian Lane and the Yi Garden in the north, with an area of 1.19 hectares (Wuxi Municipal Archives and Historical Records Center, 2012).

Data acquisition

As we enter the digital age, people not only interact in physical spaces but also engage online, leaving behind numerous digital traces that encapsulate and define their collective behaviour (Weigle et al. 2024). People rely increasingly on social media to obtain information, show their lives, socialize, and have fun. People often post satisfactory pictures of architectural spaces on social media, which are user-initiated and reflect each individual’s focus and emphasis on architectural spaces. These social media images provide a new data source for our study, so we can analyse and summarize the characteristics of these online data to understand the public’s perceived preferences for a particular area.

We use the Python program to collect the image data of “Xiaolouxiang” posted by the public on Sina Weibo (a platform characterized by many users and a wide distribution of age groups). The data collection process involves two components: the timeframe of data collection and the criteria for selecting and validating the photographs.

Regarding the timeframe for data collection, we focus on the microblogging data published by people in the three years after the completion of the neighbourhood transformation (from June 30, 2019, to June 30, 2022). We take the microblogging content published by people during Chinese legal holidays as our sample for data collection; see Table 1. Sampling with Chinese legal holidays as the time node can not only significantly improve the research efficiency but also make the research data more typical and effective because legal holidays are the prime time for people to go out, the number of people going out is the largest, and the age level coverage is the largest. There are three advantages to choosing 2019–2022 as the timeframe for obtaining the research data. First, it allows our research to obtain a large number of image data sources, given the sufficient passenger flow during this period. The Xiaolouxiang historic district was reopened in 2019 after renovation. During the first three years, the local government invested significant funds to promote the district’s opening, attracting numerous tourists and residents, with an average annual footfall reaching approximately 3 million (ChinaNews Jiangsu 2021; Wuxi Daily News 2020, 2023; Yangzi Evening News 2019). Second, this timeframe includes the unique impact of the pandemic on tourism and social behaviour, providing a more comprehensive reflection of how social networks have influenced changes in people’s use and perception of space. Since 2019, COVID-19 has had a broad and far-reaching impact on the travel industry, individuals’ perceptions, and people’s perspectives in China. The epidemic accelerated the development of online travel services, with people using social media to obtain travel information, share their experiences, and interact. Third, this timeframe focuses on the first phase of renovation, which also offers a reference point for future comparisons with the effects of the second phase of renovation, aiding in the assessment of the different impacts of the two renovations on space utilization and public perception. Beginning in 2023, the Strategic Cooperation Agreement for Cooperative Investment in the Xiaolouxiang historic district Phase II Project was signed. The Xiaolouxiang historic district successively entered its second phase of neighbourhood improvement (Wuxi Daily News 2023). Thus, this timeframe makes our research data more representative, better capturing the changes in spatial perception in the digital context exemplified by social networks.

Regarding the criteria for selecting and validating the photographs, we employed a four-step process. First, we retrieved images from posts with geographic tags labelled “Xiaolouxiang” or posts containing the keyword “Xiaolouxiang”. We retained photos depicting the buildings and spaces of the Xiaolouxiang historic district and excluded images unrelated to the site. Second, we performed deduplication by manually reviewing the images to ensure that each photograph appeared only once in the dataset. Third, we conducted manual screening to remove photos taken by professional travel bloggers and official institutions, which typically feature clear themes, strong narrative series, professional composition, meticulous postprocessing, and high colour saturation. Such images are often used for promotional purposes rather than reflecting individual perceptions of space. In contrast, personal photos are more likely to have uneven or less prominent compositions, varied and spontaneous content, minimal postprocessing, and potentially under- or overexposed colours. Fourth, we implemented member-checking strategies to ensure the reliability and validity of the data, with multiple team members reviewing the images beyond the primary reviewer. After these steps, we finalized a dataset of 1119 valid images.

However, despite these measures, some potential biases and limitations may still exist in the data analysis process. First, subjective judgement during the exclusion of professional bloggers and institutional photos may lead to the inadvertent removal of images that do reflect genuine spatial perceptions, potentially affecting the comprehensiveness of the data. We aim to minimize this error through repeated reviews by multiple team members. Second, although we obtained a dataset of 1119 valid images, achieving a certain sample size, the inclusion of additional samples could enable a more comprehensive analysis. Future research could develop image recognition and filtering algorithms to analyse more extensive datasets, thereby enhancing the comprehensiveness of the analysis.

Despite the aforementioned biases, we believe that through transparent data processing and stringent selection criteria, our research data can still accurately reflect the public perception of the Xiaolouxiang historic district. Selection and exclusion biases may affect the comprehensiveness of the data to some extent, but these biases do not alter the direction or strength of the primary conclusions.

Coding analysis

To analyse the research data, this work is based on grounded theory and uses the qualitative analysis software NVivo(Qin and Yan 2019) to manually code and analyse the data obtained from Sina Weibo about the Xiaolouxiang historic district (NVivo software supports qualitative and mixed research and can analyse multimedia, such as text, pictures, and videos).

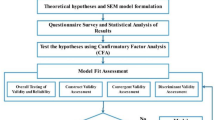

First, we use open coding to initially assign codes to the data. The process of open coding focuses on identifying and labelling various elements and salient features in the images, such as eaves tiles, guqin playing, and high and low white-walled and black-tiled buildings. As shown in Fig. 2, we obtained a total of 209 valid free nodes and 1469 reference points (reference points in the NVivo software are used to count the number of times a node or category has been tagged and coded, and the reference points can be used to determine which nodes or categories appear more frequently and in greater proportions overall).

Second, we use axial coding to find the relationships between free nodes and merge them to form new subcategories. Axial coding mainly merges free nodes based on the attributes of their keywords, e.g., clean plastered white walls and windows decorated with stacked tiles are merged into architectural details, and a total of 12 subcategories are obtained, as shown in Fig. 3.

Third, we use selective coding to integrate the subcategories. Selective coding is based mainly on the attributes of the keywords of the subcategories to merge them, such as combining the subcategories of plants, animals, objects, and food into the category of objects in architecture and space; combining the subcategories of buildings, architectural details, courtyard space, and street space into the category of architecture and space; and combining the subcategories of festivals and daily activities into the category of activities in architecture and space.

We ultimately obtained three main categories through selective coding, and the main elements under each category were determined based on the number of reference points of free nodes (presented as keywords), and the nodes or categories that were tagged and coded more often (those ranked in the top 20) were determined to be the main elements of the public’s preference for the Xiaolouxiang historic district. As a result, we constructed a framework for the public-perceived preferences for buildings and spaces in the Xiaolouxiang historic district, as shown in Fig. 4.

To ensure the reliability of the coding process, we also adopted member-checking strategies, where we had multiple members of the team code the same data and then compare the coding results of different members of the team to ensure the consistency of the coding. We also checked the preliminary coding results with the original images after the coding was completed to ensure the accuracy and authenticity of the coding results.

Research results

According to the framework of the public perception of buildings and spaces in the Xiaolouxiang historic district, the public perception of the historic district is based mainly on the three dimensions of objects in buildings and spaces, buildings and spaces, and activities in buildings and spaces. To clearly illustrate the findings, we conducted two descriptive statistical analyses. First, to determine which elements of the public’s spatial perceptions of the street are emphasized in the digital context of Xiaolouxiang, we counted all the free nodes as a percentage of the whole number of nodes and plotted a pie chart, as shown in Fig. 5. Second, to visualize the focus of public perception under buildings and spaces, objects in buildings and spaces, and activities in buildings and spaces, we plotted histograms of the top 20 free nodes according to the above three classifications, as shown in Figs. 6, 7, and 9.

The public’s preference for objects in historic district space

As shown in Fig. 6, in terms of the public’s perceived preference for objects in the historic district space, the public has a high interest in name markers for the space, installations that highlight local culture and auspicious symbols, ornamental plants, distinctive food and drink, and art installations.

As shown in Fig. 5, for name markers of spaces, the most significant proportion is the name markers for the Xiaolouxiang historic district, coded at 5.65%, which mainly include “Chinese-style streetlamps labelled with Xiaolouxiang characters”, “white walls and text backdrops hung with Xiaolouxiang logo characters”, and “plaques carved with Xiaolouxiang characters”. The largest proportion of art installations and sculptures are red and orange lanterns (4.77%). The rest are “warm light installations” (3.13%), “cool light installations” (0.95%), “western curly grass patterned ironwork and colourful light installations” (1.36%), “cultural and creative glass display cabinets embedded in the wall” (1.16%), and “cultural and creative modern style sculptures” (1.02%). Ornamental plants, including purple peonies, green peonies, moonflowers, yellow flowers, roller skies, and hydrangeas, accounted for 3.74% of the coding. Food and beverages accounted for 12.12% of the coding, which included milk tea, pizzas, crispy pancakes, hot and sour soups, etc.

The public’s preference for buildings and spaces in historic districts

As shown in Figs. 7 and 8, in terms of the public’s perceptual preferences for the buildings and spaces in the historic district, the unique perspectives and contents, quiet street space, clean plastered white walls, and details of the buildings are the four main areas of public interest.

As shown in Fig. 5, the unique perspectives and contents include “narrow alleyways” (0.82% of the total), “traditional buildings with modern high-rise commercial buildings in the background” (3% of the total), and “eaves, buildings and the sky from an upwards perspective” (1.5% of the total). Quiet street spaces, which are coded at 3.74%, mainly include streets with few travellers and small empty squares. Clean plastered white walls are coded at 3.06%. Architectural details are coded at approximately 2.8% and include elements such as eaves, ridges, horsehead walls, eave tiles, and mottled old white walls.

The public’s preference for activities in historic district space

As shown in Fig. 9, in terms of the public’s perceived preference for activities in the historic district space, the public’s main activities are divided into two categories: festivals and daily activities. Festival activities have more content, including tea ceremonies, parent-child festivals, ancient-style cultural performances, drama singing, and New Year’s events. In contrast, daily activities include painting, bubble shows, and children’s handicrafts.

By studying the Xiaolouxiang historic district, we constructed a subdivision map of the public’s preference for spatial perception in the digital context of Xiaolouxiang, as shown in Fig. 10.

Discussion

Findings from the comparison of the two contexts

A comparison of Figs. 1 and 10 reveals that in terms of the basic dimensions of the framework, the public’s spatial perceptions of the street in the digital context of Xiaolouxiang have not changed in a subversive manner compared with the ordinary traditional context. The public’s spatial perception remains focused on three dimensions: buildings and spaces, objects within these spaces, and activities occurring within these spaces.

In terms of the objects, people’s attention in the digital context of Xiaolouxiang is consistent with that in the traditional context, with a sustained focus on elements such as exterior store signs (Chen et al. 2022), landscaping (Nagata et al. 2020), food (Xie et al. 2024), public artwork and sculpture (Whyte 1980; Yosifof and Fisher-Gewirtzman 2024), multifunctional facilities (Ding et al. 2023), and “display cases and their decorations” (Targhi and Razi 2022), as shown in Fig. 6. The reason for this sustained interest in objects within space is their inherent attraction to people. For example, colourful plants and flowers in the physical environment are highly appealing, and when presented in an online environment, they easily resonate aesthetically and are widely shared.

In terms of buildings and spaces, people in traditional contexts seek a clear line of sight for observation (Yosifof and Fisher-Gewirtzman 2024), a pleasant spatial scale (Whyte 1980), and a spatial rhythm that combines movement and quietness (Gehl 1987). In the digital context of Xiaolouxiang, the public also pays attention to spaces with clear sight lines, pleasant scales, and peaceful street environments, as shown in Fig. 7. The main reason for this phenomenon is that when people participate in spatial activities, the requirement for environmental comfort is always a constant concern.

In terms of activities, research in ordinary traditional contexts has summarized the public’s perceptions of activities on the street, such as crowds gathering to do things in the space (e.g., chatting, gathering for a walk, playing chess, and playing cards) (Chen et al. 2022; Z. Wang et al. 2022), musical performances (Mehta 2007; Whyte 1980), gaming activities (Gehl 1987), sound activities in scenes (Ren et al. 2023; Yu, Kang and Ma 2016), and commercial activities (Ding et al. 2023). The focus of the public’s perception in the digital context of Xiaolouxiang has remained the same, and people still pay great attention to all kinds of activities, as shown in Fig. 8. With respect to human needs, people like a vibrant atmosphere and entertainment, comfort, safety, outdoor activities, and attractive promotional activities (Subramanian et al. 2023). At the same time, people are visually attracted to events and other activities (Targhi and Razi 2022), which creates the urge to participate in, record, and share such activities on the internet.

The characteristics of the spatial perception of the street in the digital context of Xiaolouxiang continue those in the traditional context. However, in our case study of the Xiaolouxiang historic district, we found that the perception of different aspects of the street in the digital context, while not undergoing a complete turn, has undergone three subtle changes, and these changes affect mainly individuals who engage and share content on digital platforms.

The first change was from a focus on the three-dimensional experience of space to a focus on the two-dimensional visual aesthetics of space. In the ordinary traditional context, people interact with space in the street through their senses to form a profound spatial experience (visual, auditory, tactile, and other senses work together to enable people to fully perceive the texture, temperature, sound, etc., of the space), and the sense of the sequence of routes in three-dimensional space and the richness of space are essential to people (i.e., people feel the continuity and coherence of space by walking, cycling or driving), so pleasant spatial scales (Edward T. Hall 1988), edges that are functionally diverse (Lynch 1960), rich and unique nodes (Targhi and Razi 2022), building entrance spaces (Chen et al. 2022), and building facades (Xie et al. 2024) have received attention. Moreover, functional objects such as multifunctional facilities (Ding et al. 2023), seating and support (Hass-Klau et al. 1999), awnings (Mehta 2007), and trash receptacles (Mehta 2007) in spaces have also received considerable attention. However, in the digital context of Xiaolouxiang, these elements of space and objects in the traditional context are no longer the focus of perception. The public perception of spatial objects is characterized by an emphasis on visuality and culture at the expense of functionality. This shift is particularly evident among social media users, who prioritize visually engaging content. In the digital context of Xiaolouxiang, the public is curiously looking for anything striking and unique when specific aspects of urban space are photographed through photographic frames (Lee 2010). In our empirical study, we found that some perspectives and contents that were less frequently noticed during the spatial experience frequently appeared in the coding process of the pictures, including “narrow alleyways”, “traditional buildings with modern high-rise commercial buildings in the background”, “eaves, buildings and the sky from an upwards perspective”, and “clean plastered white walls”. The visual stimulation caused by the two-dimensional visual aesthetics of space (e.g., composition, colour, light, and shadow) has had a tremendous impact on people. These unique perspectives and contents have strong compositions, visual aesthetics, and storytelling, which can satisfy people’s curiosity and freshness and are more likely to spread and cause socialization among people.

There is a deeper reason why people focus on what is unique and show it to the outside world. It is that people pursue excellence in the public sphere, thus distinguishing themselves from others (Arendt 2009). Through their visual impact and novelty, the two-dimensional visual aesthetics of space enable individuals to stand out in the public sphere and realize their pursuit of excellence. This phenomenon is particularly evident in modern society, and the popularization of social media has further amplified this trend, making the two-dimensional visual aesthetics of space an indispensable part of people’s daily lives. We should note, however, that this preference for two-dimensional visual aesthetics of space can also lead to potential problems. First, an excessive focus on the momentary aesthetics captured by photography may lead to a neglect of the ongoing real spatial experience, weakening people’s functional and substantive perception of space (Saló 2019). Second, people’s excessive pursuit of excellence in social media may lead to an overemphasis on external displays, which in turn may lead to a series of psychosocial problems, such as “self-identity crisis” and “social comparison anxiety” (F. Yang et al. 2023). Third, excessive visual stimulation may lead to aesthetic fatigue and diminish people’s interest in experiencing real space.

The second change was from emphasizing spatial totality to focusing on spatial details. In the ordinary traditional context, people pay attention to the overall parts of the street space, such as districts with clear edges (Lynch 1960), striking landscapes and landmarks (Jacobs 1961), spaces adapted to different social distances (Gehl 1987), areas to stop and linger (Gehl 1987), building entrance spaces(Chen et al. 2022), building facades (Xie et al. 2024), and prominent building facade shapes (X. Guo et al. 2022). The overall parts of the space described above offer the possibility of a space that can be experienced in a multisensory, immersive manner. This holistic experience can provide a clear sense of direction, spatial continuity, and overall ambiance, giving people a sense of psychological security and identity. However, in the digital context of Xiaolouxiang, new characteristics of the public’s spatial perception of the street have emerged. People pay attention to the details of architectural spaces such as eaves, roof ridges, horsehead walls, eaves tiles, mottled old white walls, door locks, stone carvings, and stone lions. The reason for this phenomenon is mentioned in Dong-Hoo Lee’s research, as the mobile photographer looks at a place through a photographic frame and thus becomes more attentive to its details (Lee 2010). Compared with the macro view of the overall space, architectural details are more likely to highlight specific aesthetic styles and cultural symbols, thereby creating unique and interesting themes. Driven by social media, people photograph and share details in spaces to form visually appealing and culturally significant content on the web. These details highlight the author’s unique aesthetic preferences and enhance the effect of interaction and the breadth of communication on social media. This shift reflects not only a change in visual focus but also changes in the way information is disseminated in the digital age and in social interaction. In the traditional era of mainstream media influence, such as the dissemination of information through steam printing presses, radio, and television, information was delivered in a one-way, centralized, broadcast manner (Standage 2019). However, with the increasing popularity of the internet and social media, information dissemination has become decentralized. The public is no longer just the receiver of information but has become the creator and disseminator. As a result, many people have begun to record ordinary scenes or banal moments as compelling (Lee 2010). By capturing and displaying details, individuals can express themselves in the digital space, establish and strengthen their connection with culture, and thus gain a sense of identity and belonging in social interactions. This new change could lead to adverse problems. First, excessive attention to spatial details may lead to a neglect of spatial wholeness, causing the original intent of architectural and spatial design to be misunderstood. Second, this change may also lead to the experience of fragmented space (Lee 2010). People experience space through cell phone screens, resulting in spatial perception being cut into individual visual fragments. This fragmented experience of space may weaken people’s overall perception and memory of the space, affecting its long-lasting identity and emotional connection. Third, in digital displays, some details may need to be embellished, leading to a discrepancy between the audience’s expectations and the reality of the actual space.

The third change is from a focus on the usability of the space to a focus on the cultural characteristics of the space. In the ordinary traditional context, people are mainly concerned with the humanization of the function of the street and the rationality of its use. For example, people pay attention to multifunctional facilities (Jacobs 1961) because they highly value the convenience of space for daily use. Similarly, they show significant interest in exterior store signs and branding logos (Mehta 2007), as these allow them to quickly identify information in the environment to plan their next actions.

In the digital context of Xiaolouxiang, in addition to the use of space, people are very interested in the content of the street that can convey cultural symbols. For example, people are very concerned about the red and orange lanterns that can convey the meaning of auspicious reunion, the plaques in traditional Chinese forms, the white walls with regional characteristics, and the identifiers of the place identity marked by words or images. One of the reasons why people pay attention to the cultural characteristics of space is to alleviate cultural anxiety. With the development of media and information technology, the changeability and mobility of space and place currently lead to much uncertainty, which has resulted in cultural anxiety (Morley 2001). The display and dissemination of cultural symbols through digitalization has become one of the means to alleviate this anxiety. As a result, people’s social interactions are undergoing profound changes (Pan and Yu 2015), and each person unconsciously builds his or her identity by promoting and disseminating culture (Van Dijck 2008). However, excessive attention to cultural symbols may lead to adverse problems. First, it may lead to the neglect of spatial functionality, affecting the convenience and practicality of daily life. Second, cultural displays on social media are often influenced by aestheticization and commercialization, so the display and dissemination of cultural symbols may be reduced to superficial symbolic consumption while ignoring their deeper cultural connotations and historical background.

Implications for future space design

We need to pay attention to the new characteristics of the public’s spatial perceptual preferences in the new era so that the design of the space can adapt to new forms of interaction and retain the spirit of the place while stimulating its vitality.

First, we need to pay attention to the fact that in the digital context, the public pays much attention to the aesthetics of spaces captured as two-dimensional images. In our spatial design, we need to strengthen the parts of the space that do not receive much attention in daily life but can produce unique compositions and visual aesthetics, such as creating more diversified top interfaces of the space to form more interesting visual images, setting up more traditional-style (round, vase-shaped) doorways and windows to capture unique images, strengthening the contrast between wide and narrow streets to form unique visual aesthetics, and using new installations that are graphic, Chinese, and have uniform colours to form visually striking images.

Second, we need to pay attention to the fact that the public pays more attention to spatial details in the digital context. We need to strengthen the spatial details in the design and enhance the richness and visualization of the details. By hiring experienced local craftsmen to carry out architectural tile work, woodwork, stonework, paintwork, copper work, and ironwork, we can create exquisite architectural details such as eaves tiles, windows decorated with stacked tiles, horsehead walls, and roof ridges, which are characterized by regional characteristics.

Third, we need to pay attention to the fact that the public is very concerned about the cultural characteristics of space in the context of digitization. The cultural characteristics of space can be enhanced through the design of space and objects. For example, we can use creative word markers with regional features to strengthen regional characteristics, use cultural elements with auspicious symbols to convey a friendly and joyful atmosphere to the public, and design a catering space with local cultural characteristics to convey the concept of regional branding and form a regional characteristic of Jiangnan through clean white walls. The cultural characteristics of space can also be achieved through the setup of activities. We can not only consider increasing the number of daily thematic activities such as book clubs, museum exhibitions, music festivals, and life creativity exhibitions but also consider increasing the number of festivals with different holiday themes, combining the stories behind the festivals with the history of the region and folk customs of the neighbourhood itself, and organizing various kinds of activities that can allow the audience to participate in the interaction together.

Current limitations and future research

First, this study relies primarily on the manual coding of data based on grounded theory. Although the team collaboratively coded as much data as possible, the sample size remains limited. Consequently, the new characteristics of Xiaolouxiang’s digital context presented in this study reflect only a portion of the public’s spatial perception in a digital environment. In the future, implementing image recognition algorithms could be considered to code data more efficiently, thereby expanding the research sample and leading to more comprehensive conclusions.

Second, this study utilizes social media data, which offers numerous advantages, such as broad coverage, rapid data collection, the ability to capture emerging knowledge, low costs, wide-reaching results, and the representation of collective information. However, this data source also presents several limitations. These include the potential for individual posts to be fabricated (bots or fake posts may distort the data), the lack of key demographic statistics (such as age, gender, race, income, education, and employment status), unclear definitions of control groups (observational studies of virtual communities can reveal group characteristics, but the corresponding control group warrants further exploration), and potential selection bias (as social media users tend to be younger and more tech-savvy, which often results in underrepresentation of the elderly population) (Weigle et al. 2024).

In our study, we implemented measures to mitigate the limitations of social media data. During data collection, we endeavoured to code as many image samples as possible and involved multiple team members in repeated image screenings to reduce the impact of individual fabricated posts on the overall data. In our comparative analysis, we established a framework for public spatial perception in traditional contexts based on extensive existing research. This served as a control group for the results derived from social media data, enabling us to draw valuable conclusions and identify new characteristics. Therefore, in future research, we must continue to harness the advantages of social media data while striving to minimize its limitations or compensate for them through methodological improvements.

Conclusion

Taking the Xiaolouxiang historic district in Wuxi, China, as an empirical case, this study compares the characteristics of the public’s perception of urban street space in traditional and digital contexts through a classical theory review and empirical coding analysis. The findings show that the characteristics of the public’s spatial perception of the street in the ordinary traditional and digital context of Xiaolouxiang are similar, with a focus on three dimensions: space, objects, and activities. However, in the digital era, the way people interact with the real world has changed, so the comparison reveals that the public’s spatial perception of the street in the digital context of Xiaolouxiang has undergone new changes in three aspects: from focusing on the three-dimensional experience of space to focusing on the two-dimensional visual aesthetics of space; from emphasizing spatial totality to focusing on spatial details; and from focusing on the use of space to emphasizing the cultural characteristics of space. These changes inspire us to pay attention to the new characteristics of the public’s spatial perception preferences in the new era so that spatial design can adapt to new forms of interaction and stimulate spatial vitality while retaining the spirit of the place. Therefore, in the context of digitalization, current spatial design should place greater emphasis on visual aesthetics, detail processing, and cultural expression.

This study utilized social media data as research data, which has many advantages, such as broad coverage, rapid data collection, and low costs. However, this study has several limitations, such as a lack of key demographic information, potential selection bias, and unclear definitions of the control groups. Hence, future research should develop appropriate processing measures or methods to take advantage of the strengths of social media data while minimizing their limitations.

Moreover, despite the emergence of new characteristics of the public’s perception of the space of the street in the digital context, which brings new opportunities for our spatial design, there are also many potential problems and challenges. Therefore, in the context of digitization, future research needs to explore how to balance overall spatial perception and attention to detail, achieve a balance between spatial functionality and cultural symbolic features, and achieve compatibility between the integrity of the spatial experience and the pursuit of visual aesthetics, which is highly important for the future spatial design and preservation of historical and cultural spaces.

Data availability

The raw image data in the research could not be shared due to the relevant regulations of the Weibo Community Convention, and it can be accessed at the official website of Sina Weibo (https://weibo.com) according to the retrieval method in the paper. The coded base dataset can be found in the supplementary file.

References

Abdulkarim D, Nasar JL (2014a) Are livable elements also restorative? J Environ Psychol 38:29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.12.003

Abdulkarim D, Nasar JL (2014b) Do Seats, Food Vendors, and Sculptures Improve Plaza Visitability? Environ Behav 46(7):805–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512475299

Adams PC, Jansson A (2012) Communication Geography: A Bridge Between Disciplines. Commun Theory 22(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2012.01406.x

Angel A, Cohen A, Nelson T, Plaut P (2024) Evaluating the relationship between walking and street characteristics based on big data and machine learning analysis. Cities 151:105111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2024.105111

Arendt H (2009) The Human Condition (Y Wang, Trans.). Shanghai People’s Publishing House, Shanghai

Arens E, Bosselmann P (1989) Wind, sun and temperature—Predicting the thermal comfort of people in outdoor spaces. Build Environ 24(4):315–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-1323(89)90025-5

Ashihara Y (1981) Exterior Design in Architecture. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York

Basu R, Sevtsuk A (2022) How do street attributes affect willingness-to-walk? City-wide pedestrian route choice analysis using big data from Boston and San Francisco. Transportation Res Part A: Policy Pract 163:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2022.06.007

Berto R (2007) Assessing the restorative value of the environment: A study on the elderly in comparison with young adults and adolescents. Int J Psychol 42(5):331–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590601000590

Blitz A (2021) How does the individual perception of local conditions affect cycling? An analysis of the impact of built and non-built environment factors on cycling behaviour and attitudes in an urban setting. Travel Behav Soc 25:27–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2021.05.006

Brancato G, Van Hedger K, Berman MG, Van Hedger SC (2022) Simulated nature walks improve psychological well-being along a natural to urban continuum. J Environ Psychol 81:101779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101779

Brownson RC, Hoehner CM, Day K, Forsyth A, Sallis JF (2009) Measuring the Built Environment for Physical Activity. Am J Preventive Med 36(4 Suppl):S99–123.e112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.005

Carmona M, Gabrieli T, Hickman R, Laopoulou T, Livingstone N (2018) Street appeal: The value of street improvements. Prog Plan 126:1–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2017.09.001

Carr S, Francis M, Rivlin LG, Stone AM (1992) Public Space. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA

Cerin E, Sit CHP, Barnett A, Cheung M-C, Chan W-M (2013) Walking for Recreation and Perceptions of the Neighborhood Environment in Older Chinese Urban Dwellers. J Urban Health: Bull N. Y Acad Med 90(1):56–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-012-9704-8

Chen Y, Chen Z, Du M (2022) Designing Attention-Research on Landscape Experience Through Eye Tracking in Nanjing Road Pedestrian Mall (Street) in Shanghai. Landsc Architecture Front 10(2):52–70. https://doi.org/10.15302/j-laf-1-020064

China Daily (2024) China’s social media users have exceeded 1 billion, and young people’s habits are changing. Retrieved from https://caijing.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202401/22/WS65adb59da310af3247ffcc06.html

China National Information Center (2020) 2019 China Online Media Social Value White Paper. Retrieved from https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/jd/wsdwhfz/202004/t20200414_1225675.html

ChinaNews Jiangsu (2021) Wuxi Xiaolouxiang historic district opens for 2nd anniversary, annual turnover reaches over 60 million yuan. Retrieved from https://www.js.chinanews.com.cn/news/2021/0627/204694.html

Choi J, Kim S, Min D, Lee D, Kim S (2016) Human‐centered designs, characteristics of urban streets, and pedestrian perceptions. J Adv Transport 50(1):120–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/atr.1323

Couldry N, McCarthy A (2004) MediaSpace: Place, scale and culture in a media age: Routledge

Dai T, Zheng X (2021) Understanding how multi-sensory spatial experience influences atmosphere, affective city image and behavioural intention. Environ Impact Assess Rev 89:106595

Damjanović M, Stević Ž, Stanimirović D, Tanackov I, Marinković D (2022) Impact of the number of vehicles on traffic safety: multiphase modeling. Facta Universitatis, Ser: Mech Eng 20(1):177. https://doi.org/10.22190/FUME220215012D

De Angelis G (2021) Habermas, democracy and the public sphere: Theory and practice. Eur J Soc Theory 24(4):437–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310211038753

De Nadai M, Vieriu RL, Zen G, Dragicevic S, Naik N, Caraviello M, Hidalgo CA, Sebe N, Lepri B (2016) Are Safer Looking Neighborhoods More Lively? A Multimodal Investigation into Urban Life. In: Proceedings of 24th ACM international conference on Multimedia, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 15–19 October 2016

Ding W, Wei Q, Jin J, Nie J, Zhang F, Zhou X, Ma Y (2023) Research on Public Space Micro-Renewal Strategy of Historical and Cultural Blocks in Sanhe Ancient Town under Perception Quantification. Sustainability 15(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032790

Dodge M, Kitchin R, Perkins C (2011) The map reader: theories of mapping practice and cartographic representation: John Wiley & Sons

Duan J, Hillier B, Shao R, Dai X, Read S, Ye M, Sheng Q (2007) Spatial syntax and urban planning. Southeast University Press, Nanjing

Edward T, Hall (1988) The Hidden Dimension. Doubleday, New York, p240

Ettema D (2016) Runnable Cities: How Does the Running Environment Influence Perceived Attractiveness, Restorativeness, and Running Frequency? Environ Behav 48(9):1127–1147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916515596364

Ezeh A, Oyebode O, Satterthwaite D, Chen Y-F, Ndugwa R, Sartori J, Lilford RJ (2017) The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. Lancet 389(10068):547–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31650-6

Francis J, Wood LJ, Knuiman M, Giles-Corti B (2012) Quality or quantity? Exploring the relationship between Public Open Space attributes and mental health in Perth, Western Australia. Soc Sci Med 74(10):1570–1577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.032

Franke T, Tong C, Ashe MC, McKay H, Sims-Gould J (2013) The secrets of highly active older adults. J Aging Stud 27(4):398–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2013.09.003

Fukahori K, Kubota Y (2003) The role of design elements on the cost-effectiveness of streetscape improvement. Landsc Urban Plan 63(2):75–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-2046(02)00180-9

Gatti F, Procentese F (2021) Experiencing urban spaces and social meanings through social Media: Unravelling the relationships between Instagram city-related use, Sense of Place, and Sense of Community. J Environ Psychol 78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101691

Gehl J (1987) Life Between Buildings. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York

Groenewegen PP, Van Den Berg AE, De Vries S, Verheij RA (2006) Vitamin G: effects of green space on health, well-being, and social safety. BMC Public Health 6(1):149. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-149

Guo X, Cui W, Lo T, Hou S (2022) Research on dynamic visual attraction evaluation method of commercial street based on eye movement perception. J Asian Architecture Build Eng 21(5):1779–1791. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2021.1944872

Guo Y, He SY (2021) Perceived built environment and dockless bikeshare as a feeder mode of metro. Transportation Res Part D: Transp Environ 92:102693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2020.102693

Harcourt BE, Ludwig J (2006) Broken windows: New evidence from New York City and a five-city social experiment. U Chi L Rev 73:271

Harvey C, Aultman-Hall L, Hurley SE, Troy A (2015) Effects of skeletal streetscape design on perceived safety. Landsc Urban Plan 142:18–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.05.007

Hass-Klau C, Crampton G, Dowland C, Nold I (1999) Streets as living space: Helping public places play their proper role. Landor, London

Hillier B, Sahbaz O (2008) Crime and urban design: an evidence based approach. In: Cooper R, Evans G, Boyko C (ed) Designing sustainable cities. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, p 163–186

Ho R, Szubielska M (2024) Field experiment on the effect of musical street performance/busking on public space perception as mediated by street audience experience. Sci Rep. 14(1):13147. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62672-1

Humphreys L (2010) Mobile social networks and urban public space. N. Media Soc 12(5):763–778. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809349578

Jacobs J (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities (H Jin, Trans.). Vintage Books, New York

Kabisch N, Püffel C, Masztalerz O, Hemmerling J, Kraemer R (2021) Physiological and psychological effects of visits to different urban green and street environments in older people: A field experiment in a dense inner-city area. Landsc Urban Plan 207:103998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103998

Kaplan R (1985) The analysis of perception via preference: A strategy for studying how the environment is experienced. Landsc Plan 12(2):161–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3924(85)90058-9

Kelling GL, Wilson JQ (1982) Broken windows. Atl monthly 249(3):29–38

Kirk W, Lösch A, Berlin I (1963) Problems of geography. Geography 48(4):357–371

Kleinman S (2007) Displacing place: Mobile communication in the twenty-first century. Peter Lang, New york

Klompmaker JO, Mork D, Zanobetti A, Braun D, Hankey S, Hart JE, James P (2024) Associations of street-view greenspace with Parkinson’s disease hospitalizations in an open cohort of elderly US Medicare beneficiaries. Environ Int 188:108739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108739

Knuiman MW, Christian HE, Divitini ML, Foster SA, Bull FC, Badland HM, Giles-Corti B (2014) A Longitudinal Analysis of the Influence of the Neighborhood Built Environment on Walking for Transportation: The RESIDE Study. Am J Epidemiol 180(5):453–461. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwu171

Koh PP, Wong YD (2013) Influence of infrastructural compatibility factors on walking and cycling route choices. J Environ Psychol 36:202–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.08.001

Kuo FE, Sullivan WC (2001) Environment and Crime in the Inner City: Does Vegetation Reduce Crime? Environ Behav 33(3):343–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160121973025

Laurier E (2008) Drinking up endings: Conversational resources of the cafe. Lang Commun 28(2):165–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2008.01.011

Laurier E, Philo C (2007) ‘A parcel of muddling muckworms’: revisiting Habermas and the English coffee-houses. Soc Cultural Geogr 8(2):259–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360701360212

Lee D-H (2010) Digital Cameras, Personal Photography and the Reconfiguration of Spatial Experiences. Inf Soc 26(4):266–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2010.489854

Li Y, Chen F, Hua G (2021) On the Tourist Experience Based on Web Text of Historical and Cultural District of the Grand Canal. Nanjing J Soc Sci 02:157–165. https://doi.org/10.15937/j.cnki.issn1001-8263.2021.02.019

Lim M (2014) Seeing spatially: people, networks and movements in digital and urban spaces. Int Dev Plan Rev 36(1):51–72. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2014.4

Lynch K (1960) The image of the city. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Ma S, Wang B, Liu W, Zhou H, Wang Y, Li S (2024) Assessment of street space quality and subjective well-being mismatch and its impact, using multi-source big data. Cities 147:104797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2024.104797

Mahmoudi M, Ahmad F (2015) Determinants of livable streets in Malaysia: A study of physical attributes of two streets in Kuala Lumpur. Urban Des Int 20(2):158–174. https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2015.3

McDonald T (2015) Affecting relations: domesticating the internet in a south-western Chinese town. Inf Commun Soc 18(1):17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2014.924981

Mehta V (2007) Lively streets - Determining environmental characteristics to support social behavior. J Plan Educ Res 27(2):165–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456x07307947

Moore THM, Kesten JM, López-López JA, Ijaz S, McAleenan A, Richards A, Audrey S (2018) The effects of changes to the built environment on the mental health and well-being of adults: Systematic review. Health Place 53:237–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.07.012

Morley D (2001) Belongings: Place, space and identity in a mediated world. Eur J Cultural Stud 4(4):425–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/136754940100400404

Mouratidis K (2021) Urban planning and quality of life: A review of pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being. Cities 115:103229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103229

Nagata S, Nakaya T, Hanibuchi T, Amagasa S, Kikuchi H, Inoue S (2020) Objective scoring of streetscape walkability related to leisure walking: Statistical modeling approach with semantic segmentation of Google Street View images. Health Place, 66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102428

Nasar JL (2008) Assessing Perceptions of Environments for Active Living. Am J Preventive Med 34(4):357–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.01.013

Neale C, Aspinall P, Roe J, Tilley S, Mavros P, Cinderby S, Thompson CW (2017) The aging urban brain: analyzing outdoor physical activity using the emotiv affectiv suite in older people. J Urban Health 94:869–880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-017-0191-9

Oyama Y (2024) Spatial city image and its formative factors: A street-based neighborhood cognition analysis. Cities 149:104898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2024.104898

Pan Z, Yu H (2015) Liminality and Potentials of Urban Space. Open Times(03), 140-157+148-149

Paus T, Kum H-C (2024) Digital Ethology: Human Behavior in Geospatial Context. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Peng X, Wang Y, Huang Z (2022) Research on Differences of Image Perception of Beijing Historical and Cultural Districts among Various Cultural Groups. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis 58(05):949–958. https://doi.org/10.13209/j.0479-8023.2022.078

Porter AK, Kohl HW, Pérez A, Reininger B, Pettee Gabriel K, Salvo D (2018) Perceived Social and Built Environment Correlates of Transportation and Recreation-Only Bicycling Among Adults. Preventing Chronic Dis 15:180060. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.180060

Procentese F, Gatti F, Di Napoli I (2019) Families and Social Media Use: The Role of Parents’ Perceptions about Social Media Impact on Family Systems in the Relationship between Family Collective Efficacy and Open Communication. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(24). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245006

Pushkarev B (1976) Urban space for pedestrians. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Qian X, Heath T (2019) Examining three roles of urban “portals” in their relationship with “places” using social media photographs. Cities 90:207–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.02.011

Qin F, Yan L (2019) The Communication Effect and Enhancement Path of Cultural TV Programs-NVivo Analysis Based on the Microblog Data of the program “Everlasting Classics”. China Television (10), 46-51

Quercia D, O’Hare NK, Cramer H (2014, 2014-02-15). Aesthetic capital: what makes london look beautiful, quiet, and happy? Paper presented at the CSCW'14: Computer Supported Cooperative Work

Ren X, Wei P, Wang Q, Sun W, Yuan M, Shao S, Xue Y (2023) The effects of audio-visual perceptual characteristics on environmental health of pedestrian streets with traffic noise: A case study in Dalian, China. Front Psychol 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1122639

Rezvanipour S, Hassan N, Ghaffarianhoseini A, Danaee M (2021) Why does the perception of street matter? A dimensional analysis of multisensory social and physical attributes shaping the perception of streets. Architectural Sci Rev 64(4):359–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/00038628.2020.1867818

Rui J, Xu Y (2024) Beyond built environment: Unveiling the interplay of streetscape perceptions and cycling behavior. Sustain Cities Soc 109:105525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2024.105525

Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD (2003) Environmental correlates of walking and cycling: Findings from the transportation, urban design, and planning literatures. Ann Behav Med 25(2):80–91. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2502_03