Abstract

The collaboration of healthcare systems in Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China is a critical issue for addressing the medical needs of internal migrants in China, who often face disparities in coverage and access to services when moving across these three regions. These migrants are particularly disadvantaged by the structural differences between the universal public healthcare systems of Hong Kong and Macao and the combined social medical insurance and universal health insurance system in the mainland of China. This paper examines these distinct healthcare models and finds that significant differences in coverage, funding, and service delivery pose key challenges to the portability of benefits for cross-region migrants and the collaboration of regional healthcare systems. To advance healthcare collaboration and ensure that migrant populations receive equitable healthcare, the paper proposes establishing a fiscal compensation mechanism to address the financial imbalances caused by cross-region service usage. It also advocates for adopting principles for the portability of healthcare benefits and regulating cross-region medical services to create a more cohesive and integrated regional healthcare system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Collaborative governance is utilized to tackle complex public policy challenges and public service delivery tasks (Siddiki et al., 2017). Over the past two decades, healthcare collaboration has increasingly emerged as a vital component of public policy integration in Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China. Since their return to China, both Hong Kong and Macao have maintained distinct healthcare systems that operate independently from each other and from the mainland of China. Healthcare collaboration among Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China, not only addresses the medical service needs of cross-region individuals, but also promotes the flow of production factors and people in China, advancing the overall development of the country.

The increasing mobility of populations between Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China has introduced new challenges for healthcare access, particularly for cross-region migrants who encounter inconsistent coverage and service delivery across these regions. Migrant typically refers to individuals who move temporarily, typically for work-related purposes, and may not intend to settle permanently in their destination country or region (IOM, 2019). The seventh national population census in 2020 recorded 371,380 residents from Hong Kong and 55,732 from Macao in mainland China (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2021), marking increases of 136,551 (58.1%) and 34,531 (162.9%) respectively since 2010. As the number of Hong Kong and Macao residents in the mainland of China increases, their use of local medical services is also growing. In Guangdong Province alone, medical institutions recorded 8037 inpatient visits from Hong Kong residents and 2072 from Macao residents in 2019 (Guangdong Provincial Health Commission Government Service Center, 2019), with these figures rising significantly in 2021 to 10,750 and 5403 visits, respectively (Guangdong Provincial Health Commission Government Service Center, 2022).

Migrants often encounter significant barriers to accessing healthcare services due to a combination of economic, legal, and social challenges (Savas et al., 2024). This issue has garnered increasing attention in recent years. Nur et al. (2024) conducted a literature review focusing on healthcare access and equity among migrants globally, analyzing journal articles published since 2017. Their findings indicate that inequalities within migrant communities persist, particularly concerning access to healthcare services. In the context of Europe, Galanis et al. (2022) performed a literature review of sixty-five studies, identifying that the lack of health insurance is one of the common barriers faced by migrants in accessing healthcare. Similarly, Lebano et al. (2020) conducted a scoping review on healthcare access for migrants across nine European countries, revealing that many migrants encounter significant legal barriers that restrict their access to public healthcare services. Bettin and Sacchi (2020) explored the impact of immigrants on public health expenditure across various regions in Italy from 2003 to 2016, shedding light on the financial implications of migrant health. Schmidt et al. (2022) carried out systematic analysis of literature and online databases on EU-funded cross-border healthcare collaborations from 2007 to 2017 revealed that shared historical ties and geographical proximity are crucial for these collaborations.

In the mainland of China, Chen et al. (2022) highlighted that, despite the growing popularity of the country as a destination for domestic workers, the health status of these international migrant workers remains largely overlooked both as a public concern and within academic research. While research on healthcare services for China’s internal migrant population has primarily concentrated on rural migrant workers, there is considerably less focus on the mobility between the mainland of China and the Hong Kong and Macao regions. This gap underscores the need for more comprehensive studies addressing the healthcare challenges faced by these populations.

The purpose of this paper is to explore the challenges and propose solutions for promoting cross-regional collaboration in healthcare systems among Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China. The core research question driving this study is: How can healthcare systems in Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China overcome structural and operational disparities to ensure equitable and portable healthcare access for cross-region migrants?

Centering on the research question, this study employs a comparative framework to analyze the healthcare systems of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, focusing on the dimensions of coverage, funding, and service delivery. By utilizing policy documents, statistical data, and international case studies from regions that have faced similar integration challenges, the paper highlights the distinct healthcare models and the specific issues they pose for cross-region migrants, particularly concerning funding and service delivery. Ultimately, this paper aims to provide actionable insights into how regional collaboration can be achieved, thereby improving healthcare equity and accessibility across the Greater Bay Area. A particular emphasis will be placed on exploring the establishment of a fiscal compensation mechanism, which is crucial for addressing disparities in healthcare access.

Comparative analysis of regional healthcare system

The Welfare Regime Theory can serve as a starting point for comparative studies of healthcare systems (Yang and Leung, 2010). Welfare regime, in general, encompass all institutional arrangements, policies, and practices that shape welfare outcomes and social stratification across various social and cultural contexts s (Gough, 2004). The construction and reform of welfare regime are deeply influenced by factors such as political regimes, democratization processes, government bureaucracies, state capacity, market economy development, and civil society growth, which result in significant variations across countries (Xiong, 2010). Titmuss (1974) outlined three welfare regime models: institutional redistribution based on universalism, residual welfare based on selectivism, and industrial achievement-performance models centered on work performance and productivity. Esping-Andersen (1990) categorized welfare regimes into three ideal types, namely Social Democratic, Christian Democratic, and Liberal. A welfare regime typically operates within regional boundaries, with coverage restricted to populations within the designated area. Given that migration may involve movement across different welfare regimes, addressing healthcare access for migrants may require regional coordination among these regimes.

Healthcare system is a social mutual aid mechanism that provides financial protection against the risks associated with illness (Shen, 2021). In Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China, distinct models of healthcare systems are currently in operation. Healthcare systems encompass various options, including social medical insurance, universal health insurance, and universal public healthcare (Gu, 2017). Presently, Hong Kong and Macao implement a universal public healthcare model, while the mainland of China employs a combination of social medical insurance and universal health insurance (Gu, 2019). This diversity in healthcare systems complicates efforts to promote collaboration among the regions, particularly for cross-regional migrants who may encounter barriers to accessing essential medical services. The promotion of healthcare collaboration is significantly challenged by the need to coordinate these differing models, which can hinder effective integration and accessibility of healthcare for mobile populations.

To advance healthcare collaboration among Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China, it is essential to first identify the key differences in their healthcare systems. This step is crucial for understanding the barriers that hinder effective collaboration. This paper’s comparative analysis of healthcare systems across the three regions will focus on three critical aspects: coverage, funding, and service delivery. The characteristics of regional healthcare systems in the mainland of China, Hong Kong and Macao are shown in Table 1.

Coverage

The mainland of China forms a multi-level healthcare system with urban employee medical insurance and urban-rural resident medical insurance as the two core programs, supplemented by serious illness insurance, and medical assistance. Urban employee medical insurance covers employees of all urban employers, urban-rural resident medical insurance covers urban and rural residents without formal employment, and medical assistance targets economically disadvantaged residents. Although China’s basic medical insurance system has achieved universal coverage in terms of institutional design, there are still segments of the population, such as certain workers, who are not covered due to their lack of participation in the insurance program (He, 2024). Based on the number of participants in the national basic medical insurance program and the total population at the end of 2022, it is estimated that there are still 66.05 million people in the mainland of China who have not yet participated in basic medical insurance (Shu et al., 2024).

Hong Kong operates a universal public healthcare system that provides comprehensive coverage for all permanent and non-permanent residents, offering them access to subsidized public healthcare services. Macao implements a similar model, providing universal public healthcare to its residents. Hong Kong has inherited the healthcare system of the UK National Health Service, with public medical institutions providing basic medical protection for every resident (Zhang et al., 2022). Although Hong Kong has historically eschewed the welfare state system and adopted a deficiency-based social policy approach, it has a deep government intervention in healthcare policy (Ramesh, 2004).

Funding

Funding is a critical aspect of healthcare system operation. In a healthcare system, the principle of service funding is often based on specific models of local healthcare service demand and supply, with interconnected institutional elements forming a cohesive whole (Werding and McLennan, 2015). In the mainland of China, the medical insurance for urban employees adopts a funding system where employees contribute while retirees do not, and the medical insurance for urban-rural residents adopts a lifetime payment system (Sun et al., 2019). While urban employee medical insurance is funded jointly by the contribution from both employers and employees, urban-rural resident medical insurance adopts a fixed funding system combining individual contributions and government subsidies. The whole system faces the problem of fragmented funding models (Gu, 2017).

In Hong Kong and Macao, funds are allocated to public healthcare institutions through direct government funding from taxation, while some medical services are diverted to private healthcare institutions through medical vouchers. Unlike the mainland’s model of subsidizing both supply and demand sides simultaneously, the Hong Kong SAR government subsidizes the supply side, with annual fiscal appropriations accounting for 90% of public healthcare institution expenditures (Gao et al., 2019). Similarly, the operating expenses of public medical institutions in Macao are funded by the Macao SAR government through budget allocations (Song and Bian, 2020).

Service delivery

Highly equitable and accessible healthcare services can effectively enhance the legitimacy of the healthcare system (Ramesh, 2008). In the mainland of China, insured individuals receive corresponding medical treatments and services based on their program and duration of coverage, leading to evident hierarchical divisions. For instance, the social medical insurance system in Shenzhen is multi-tiered and multi-form, with basic medical insurance divided into three forms based on insured individuals’ contributions and corresponding benefits. Although the overall level of China’s basic medical insurance has gradually improved, different populations still apply to different programs, resulting in a significant disparity in the benefits provided by these programs (He, 2024).

The Hong Kong SAR government provides healthcare services to all residents at minimal or no cost, ensuring broad access to essential medical care (Kong et al., 2015). For patients receiving comprehensive social security assistance and some socially disadvantaged groups, public hospitals have fee exemption mechanisms. Similarly, Macao’s health centers provide free basic medical services to Macao residents. The Conde de São Januário Hospital Center mainly provides specialist services, and its emergency and outpatient services are charged on a per-visit basis, with a consultation fee of MOP 42 per visit, while services such as tests, drugs, treatments, and surgeries are charged at 70% of the actual cost. Certain specific populations, such as pregnant and puerperal women, the elderly, children, students, teachers, public servants or their family members, impoverished groups, and patients with specific diseases who meet certain conditions, do not need to pay these fees.

Challenges of collaboration

Hong Kong, Macao and the mainland of China are characterized by the unique attribute of “one country, two systems, three legal jurisdictions”. In terms of healthcare system collaboration, this challenge specifically manifests as difficulties in aligning the healthcare systems of the three regions due to differences in their healthcare financing models.

Funding

Healthcare financing in the Hong Kong and Macao regions relies on general taxation, with no direct association with individual members of society. In contrast, the mainland of China emphasizes individual contributions and participation responsibilities in healthcare financing, closely linking welfare entitlements with responsibilities. Given that the current level of economic development may not fully support a purely welfare-oriented healthcare financing model, the mainland of China may continue to rely predominantly on a social health insurance model for a considerable period, resulting in a significant disparity between its healthcare financing model and those of Hong Kong and Macao (He and Li, 2018).

In this context, healthcare coordination cannot adopt the widely used principle of cumulative insurance periods in pension coordination. This is especially pronounced in many mainland cities, where the duration of insurance coverage is strongly linked to medical insurance benefits. An example is Shenzhen, where a continuous insurance period of 36 months is required to receive 90% fund reimbursement for major outpatient expenses. This issue becomes even more significant for cross-region workers from the Hong Kong and Macao employed in these Greater Bay Area cities, who cannot provide records of continuous insurance coverage in other cities similar to mainland workers, nor do they benefit from regional transfers of healthcare insurance funds. Therefore, establishing coordinated healthcare across the mainland of China, Hong Kong, and Macao poses significant technical challenges in aligning the healthcare benefit qualification of workers from the Hong Kong and Macao with the mainland healthcare system and calculating the necessary transfers of healthcare funds.

Service delivery

The synergy of healthcare provision represents a reform of the healthcare system for members of the region. Systemic reforms bring about income redistribution and restructuring of the pattern of public service utilization, resulting in beneficiaries and losers from the reform. Ensuring and balancing the interests of all parties to achieve fairness in institutional reform is crucial for the successful implementation of such reforms (Wu, 2009). One critical aspect of the rule alignment in healthcare provision is the output of healthcare benefits. Effective benefit output measures should ensure that other members of the healthcare system do not suffer losses or gain unexpected benefits due to the movement of certain members (Werding and McLennan, 2015). Otherwise, opposition from societal members to regional alignment schemes is highly likely.

In this regard, Brexit provides a practical example. The National Health Service (NHS), a universal healthcare system in the UK, has been a prideful institutional arrangement for the British, addressing healthcare concerns for its citizens through the power of public finances. However, within the framework of EU social security integration, the UK’s NHS became a focal point of issues. Before Brexit, workers from EU member states could freely access the UK for employment and, through the EU’s integrated social security system, benefit from the UK’s NHS. As a highly developed economy within the EU, the UK experienced a significant influx of workers and their families from less economically developed member states, such as Poland, after the EU’s eastward expansion. The net number of immigrants from EU countries rose sharply, increasing from 72,000 in 2012 to 189,000 in 2016—a surge of nearly 120,000 (ONS, 2018). This rapid influx strained the NHS, increasing the financial burden on the healthcare system and extending waiting times for British citizens, with the proportion of patients waiting over 18 weeks from referral to treatment continuing to rise (National Health System, England, 2018). Consequently, British citizens began opposing the UK’s continued membership in the EU, leading to Brexit through a referendum (Wu and Liang, 2019). The funding issue for the NHS was a significant factor leading up to the referendum (Drinkwater and Robinson, 2023).

Macao and Hong Kong, as economically developed regions with universal public healthcare systems, share similarities with the UK. Apart from minor differences in institutional frameworks, both regions have experienced continuous increases in public healthcare expenditure. Public healthcare expenditure in Hong Kong has grown steadily over the past few decades, from HKD 6.73 billion in the 1989–1990 fiscal year to HKD 117.7 billion in the 2022–2023 fiscal year, excluding identified COVID-19 expenditures (Health Bureau, Hong Kong, 2024). Based on current taxation structures, public healthcare expenditure is expected to continue being a prominent issue in Hong Kong’s future development (Yung, 2016). The Hong Kong SAR government has continuously worked to accommodate the growing public healthcare expenditure in recent years (Kong et al., 2015). Moreover, some Hong Kong residents believe that only they are entitled to access Hong Kong’s resources and that only they should decide who can qualify for such entitlements (Mok, 2016).

If cross-region collaboration is implemented too quickly, Hong Kong and Macao could face challenges similar to those experienced by the UK, such as an influx of patients from economically less developed areas. The capacity constraints of healthcare systems inevitably lead to waiting times, and if local capacity is not scaled up while cross-region collaboration expands, residents may experience longer wait times, potentially leading to dissatisfaction (Wu and Liang, 2019). Thus, it is crucial to advance cross-region healthcare collaboration cautiously, ensuring that the resources and capacities of Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macao are aligned with the expected increase in patient demand. This careful approach will safeguard the quality of health services for residents while promoting shared prosperity within the Greater Bay Area.

Actions of collaboration

Actions of the healthcare collaboration in the mainland of China

At present, residents of Hong Kong and Macao who work in the mainland of China, along with their family members, are already integrated into the mainland’s healthcare system and receive benefits equal to those of residents in the mainland of China. Hong Kong and Macao residents employed in mainland cities can legally participate in local employee basic medical insurance and enjoy equal benefits. Even Hong Kong and Macao residents who only reside, but do not work, in the mainland of China can participate in the local urban and rural residents’ basic medical insurance. As of the end of 2022, in Guangdong Province alone, over 100,000 individuals from Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan participated in employee health insurance, and more than 120,000 participated in urban and rural resident health insurance (Guangdong Provincial Healthcare Security Bureau, 2023)

Actions of the healthcare collaboration in Hong Kong

For residents seeking medical treatment in the mainland of China, Hong Kong has initiated pilot programs, currently limited to specific groups, namely eligible elderly individuals, with designated service scopes. Facing the challenge of rapidly aging populations, cross-region elderly care is one of the key measures to address this challenge. The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government began addressing cross-region elderly care issues after 1997, while the Macao Special Administrative Region government has actively promoted cross-region elderly care for Macao residents in the Hengqin Guangdong-Macao In-depth Cooperation Zone in recent years. Hong Kong’s elderly population may relocate to the mainland of China due to lower living costs and a desire to reunite with family members in the mainland. In 2015, the Hong Kong SAR government launched a pilot policy within the existing framework of the “Elderly Healthcare Voucher Scheme”, allowing elderly individuals residing in the mainland of China to use medical services at the Hong Kong University Shenzhen Hospital. Under Hong Kong’s Elderly Healthcare Voucher Scheme, elderly Hong Kong residents can receive annual vouchers of HKD 2000 from the government for medical expenses at private medical institutions, with any unused balance carried over to the next year (He and Li, 2018).

By the end of 2018, the number of Hong Kong elderly individuals using healthcare vouchers at the University of Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital had risen from 507 in 2015 to 3415, with total claims exceeding HKD 7.3 million, covering around RMB 6.3 million in medical service costs (Department of Health, Hong Kong, 2019). The total amount claimed under the “Elderly Health Care Voucher Scheme” at this hospital increased to HKD 34.9 million between 2021 and 2023, with 106,800 claims submitted during this period (PwC China, 2024). Currently, within the scope of the Hong Kong University Shenzhen Hospital, the use of healthcare vouchers is limited to outpatient medical care services provided by departments designated under the pilot policy, with inpatient services not covered. Additionally, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of cross-region medical services for Hong Kong residents residing in the mainland of China has significantly increased. The Hong Kong SAR government has introduced special policies for Hong Kong residents stranded in the mainland of China due to pandemic control measures, allowing them to visit the Hong Kong University Shenzhen Hospital for follow-up consultations and treatment based on their Hong Kong medical records. In 2023, the Hong Kong SAR government launched the “Pilot Scheme to Support Hospital Authority Patients in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area”, allowing patients with scheduled follow-up appointments at designated specialist or general outpatient clinics under the Hospital Authority to receive subsidized medical services at the University of Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital. The subsidy limit for each patient is RMB 2000.

Ways forward

To address the fragmentation of regional healthcare systems and meet the needs of cross-regional migrants, enhanced collaboration is essential. A fundamental challenge lies in establishing collaborative governance among Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China. The central government of China leads and coordinates affairs involving Hong Kong and Macao. Thus, this collaborative governance encompasses both vertical collaboration, which involves coordination between the central government and the governments of Hong Kong and Macao, and horizontal collaboration, which includes interactions between the governments of Hong Kong and Macao and the provincial governments in the mainland of China, as well as local governments in mainland cities. This collaboration mechanism operates under the “One Country, Two Systems” framework, adding complexity compared to collaboration between different local governments within the mainland of China.

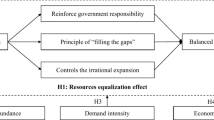

It is crucial to leverage the key factors identified through empirical research and to draw on international best practices in a targeted manner to foster innovation in government collaboration mechanisms among Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China. As illustrated in Fig. 1, this collaborative governance framework will encompass policy coordination, service integration, interest coordination, and information communication. In the context of healthcare systems, several key issues must be addressed, including multilateral agreements on healthcare, welfare export, fiscal compensation, and medical information sharing.

The international schemes for the export of healthcare benefits generally cover two categories of migrants and adopt different export principles: (1) For migrant workers and their families, bilateral or multilateral agreements typically allow workers and their families to enter the host country’s medical security coverage once they obtain legal status through formal work permits; (2) For other types of mobile populations, such as retirees returning to their home country or moving to another country, it is essential to define under what circumstances they can access medical services in their place of residence and how the medical systems of the host and home countries should share the corresponding medical service costs (Werding and McLennan, 2015). In practice, the EU’s scheme for aligning social security regulations is widely regarded as the most comprehensive solution for addressing the export of social security benefits (Avato et al., 2010). In 2011, the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union passed the Directive on the Rights of Patients in Cross-region Healthcare, further enhancing the portability of healthcare benefits. Portability, in this context, refers to the capacity of migrants to retain, sustain, and transfer social security entitlements, including healthcare benefits, internationally (Cruz, 2004). The EU has established a relatively comprehensive management system for coordinating healthcare security systems, which can serve as a reference for China (Wang et al., 2023). Based on international principles and EU practices, this paper attempts to outline a basic scheme for aligning medical security regulations in Hong Kong, Macao and the mainland of China for cross-region workers, retirees, and those seeking specific medical services.

To support migrant workers, establishing a fiscal compensation mechanism between the healthcare systems of Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China is essential. Migrant workers, defined as individuals employed in a region or country other than their usual place of residence (Taha, Siegmann, and Messkoub, 2015), often work across both their home and host regions, with some returning to their home region after retirement. This mobility places a financial burden on the healthcare systems in both areas. Therefore, it is crucial to create a mechanism where the medical cost funding systems in these regions compensate one another, ensuring fiscal fairness and accounting for the economic impact of these migrations (Werding and McLennan, 2015). Such a system would enhance equity and sustainability in cross-region healthcare collaboration.

In this issue, the central government of China needs to take the necessary steps to push forward policies. The establishment of a fiscal compensation mechanism would involve the fiscal revenues and expenditures of Hong Kong and Macao, as well as the medical insurance fund revenues and expenditures of the mainland cities in the Greater Bay Area. For instance, in Zhuhai, which is adjacent to Macao, from January 1, 2020, the government of Zhuhai fully opened participation in its basic medical insurance to Hong Kong and Macao residents who hold residence permits, regardless of employment status. As of the end of February 2023, a total of 73,800 Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan residents were enrolled in Zhuhai’s medical insurance system, with 63,400 from Macao and 9100 from Hong Kong, making up 98.2% of the total (Qian, 2023). Between 2020 and February 2023, nearly 130,200 Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan enrollees enjoyed Zhuhai’s medical insurance benefits, with the medical insurance fund paying out a total of RMB 123 million (Qian, 2023).

Under the fiscal compensation mechanism, the Hong Kong and Macao SAR governments would need to reimburse Zhuhai up to RMB 123 million in extreme cases to compensate for the expenditures from Zhuhai’s medical insurance fund. This figure only accounts for the expenses of one mainland Greater Bay Area city—Zhuhai. If the data from all nine mainland Greater Bay Area cities were aggregated, it would imply that the Hong Kong and Macao SAR governments would need to bear even higher fiscal expenditures. However, in the current absence of a fiscal compensation mechanism, Hong Kong and Macao SAR governments are not required to bear these expenses. Therefore, Hong Kong and Macao face a financial dilemma in pushing forward the establishment of such a mechanism. At present, the innovation and implementation of cross-border healthcare cooperation policies are still primarily driven unilaterally by the mainland of China, and comprehensive cooperation and coordination have not yet fully begun. There remains a lack of shared risk in healthcare, which may pose challenges to the long-term sustainable development of the three regions’ healthcare systems. Therefore, it is necessary to gradually explore and advance this under the guidance of the central government of China.

Furthermore, it is essential to clarify the basic principles of cross-region portability of healthcare benefits. Given the differences in funding rules for healthcare between the mainland of China, Hong Kong, and Macao, the portability of benefits can take inspiration from the EU’s “temporal” principles for welfare benefit portability. For workers who have been employed in Hong Kong and Macao and later move to mainland cities for work, their employment duration in Hong Kong and Macao should be counted as insured time under the urban employee medical insurance in the mainland of China. This will prevent them from losing their healthcare rights due to cross-region employment and ensure that they meet the continuous insurance period requirements in mainland cities to access corresponding benefits.

Similarly, for mainland workers who return to the mainland of China for work or retirement after a period of employment in Hong Kong and Macao, their work time in those regions should also be counted as insured time and added to their previous insured period in the mainland of China. This will ensure that mainland workers returning for work or retirement can qualify for the medical insurance benefits offered by mainland cities, maintaining continuity of coverage and reducing financial insecurity related to healthcare. This approach promotes fairness and security for cross-region workers, preventing disruptions in healthcare coverage during periods of employment mobility.

For cross-region retirees and patients seeking specific medical services, reimburse cross-region medical expenses through existing healthcare systems. For these two groups, the EU scheme follows the principle of settling medical expenses at the price of the treatment country, with reimbursement by the home country’s healthcare fund. Existing cross-region retirees can remain covered by the system of their home country and have their medical services in the host country reimbursed through their home country’s healthcare system (Werding and McLennan, 2015). The same principle can apply to patients seeking specific medical services across regions, where medical expenses are settled in the treatment region and reimbursed by the insurance region. Second, define the scope of cross-region medical services coverage. According to the EU’s practice, the basic principle is that medical services obtained abroad must be covered by the healthcare system of the home country to be eligible for reimbursement. Additionally, for those seeking specific medical services abroad, they must first undergo an assessment by their home country’s healthcare system to confirm the necessity of seeking treatment abroad. The EU scheme also excludes certain medical services, such as organ transplants and vaccinations, from cross-region medical service coverage. Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China can conduct in-depth research to determine whether similar regulations should be adopted within the region.

Conclusions

In China, collaborative governance is a relatively new concept, and the capacity of public management to manage such collaboration is still in its early stages (Brown et al., 2012). The integration of healthcare systems in Hong Kong, Macao and the mainland of China is a complex but critical endeavor that addresses the medical service needs of cross-region individuals and promotes the overall development of the region. Actively addressing the healthcare issues of cross-region migrants is essential to ensure that residents of the Greater Bay Area can easily access adequate medical services regardless of their location within the region (Zeng, 2018). The fragmentation and segregation of healthcare systems hinder the overall effectiveness of the region’s healthcare delivery and particularly increase occupational risks for cross-region workers (Lu et al., 2010). The primary challenges arise from significant differences in the healthcare systems of the mainland of China, Hong Kong, and Macao.

This paper has addressed the significant challenges in promoting cross-regional healthcare collaboration among Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China. By identifying critical differences in coverage, funding, and service delivery, the study proposed targeted solutions, including the establishment of a fiscal compensation mechanism and the development of healthcare benefit portability. These solutions are grounded in a comparative analysis of the healthcare systems across the regions, supported by relevant policy data and case studies. The findings underscore the need for strategic, midrange approaches to foster greater collaboration and ensure equitable healthcare access for cross-region migrants, contributing to the broader discourse on regional healthcare integration. Successful integration of these healthcare systems in China can serve as a model for other regions facing similar challenges, demonstrating the importance of collaboration and innovation in addressing complex regional healthcare issues.

Data availability

The data analyzed in this study are from original publications or official websites. China Population Census Yearbook 2020, https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/7rp/indexch.htm. Tabulation on the 2010 Population Census of the Peoples Republic of China, https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm. China Statistical Yearbook 2023, https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2023/indexeh.htm. The datasets of Long-Term International Migration and International Passenger Survey estimates, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/datasets/tableofcontents. Hong Kong’s Domestic Health Accounts, https://www.healthbureau.gov.hk/statistics/en/dha.htm.

References

Avato J, Koettl J, Sabates-Wheeler R (2010) Social security regimes, global estimates and good practices: the status of social protection for international migrants. World Dev 38(4):455–466

Bettin G, Sacchi A (2020) Health spending in Italy: the impact of immigrants. Eur J Polit Econ 65:101932

Brown TL, Gong T, Jing J (2012) Collaborative governance in Mainland China and Hong Kong: introductory essay. Int Public Manag J 4:393–404

Chen H, Gao Q, Yeoh BSA, Liu Y (2022) Irregular migrant workers and health: a qualitative study of health status and access to healthcare of the Filipino domestic workers in Mainland China. Healthcare 10(7):1204

Cruz A (2004) Portability of benefit rights in response to external and internal labour mobility: the Philippine experience. Paper presented at the International Social Security Association (ISSA), Thirteenth Regional Conference for Asia and the Pacific in Kuwait, March 8–10

Department of Health, Hong Kong (2019) Elderly healthcare voucher scheme review report. Available at: https://www.hcv.gov.hk/files/pdf/Review_Report_Chinese.pdf

Drinkwater S, Robinson C (2023) Brexit and the NHS: voting behaviour and views on the impact of leaving the EU. Br Polit 18:557–578

Esping-Andersen G (1990) The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press

Galanis P, Spyros K, Siskou O, Konstantakopoulou O, Angelopoulos G, Kaitelidou D (2022) Healthcare services access, use, and barriers among migrants in Europe: a systematic review. medRxiv 2022-02

Gao Y, Gong X, Lin X (2019) The role and opportunities of Hong Kong in the medical development of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Hong Kong Macao Stud 4:65–73+95-96

Gough I (2004) Welfare regimes in development contexts: a global and regional analysis. In: Gough I et al. (eds.), Insecurity and welfare regimes in Asia, Africa, and Latin America: social policy in development contexts. Cambridge University Press

Gu X (2017) Towards quasi-universal free medical care: organizational and institutional innovations in China’s basic healthcare security system. Soc Sci Res 1:102–109

Gu X (2019) The new era of China’s medical reform and the new challenges facing the national medical security bureau. Acad Horiz 1:106–115

Guangdong Provincial Health Commission Government Service Center (2019) Analysis of inpatient rates within counties of Guangdong Province in 2018. Available at: https://www.gdhealth.net.cn/html/2019/tongjishuju1_0402/3853.html

Guangdong Provincial Health Commission Government Service Center (2022) Analysis of inpatient rates within counties of Guangdong Province in 2021. Available at: https://www.gdhealth.net.cn/html/2022/tongjishuju1_0512/4219.html

Guangdong Provincial Healthcare Security Bureau (2023). Guangdong Provincial Healthcare Security Bureau’s response to Proposal No. 20230196 of the 13th Guangdong Provincial CPPCC Session. Available at: https://hsa.gd.gov.cn/gkmlpt/content/4/4170/post_4170794.html#2605

He J, Li Z (2018) How does the world’s most efficient healthcare system address challenges?—the medical management system, reform measures, and implications for the Mainland of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Chin Health Policy Res 12:68–74

He W (2024) Optimization of the medical security system based on common prosperity. Soc Sci Chin Univ 5:56–66+158

Health Bureau, Hong Kong (2024) Hong Kong’s Domestic Health Accounts (exclude identified COVID-19 expenditure). Availible at: https://www.healthbureau.gov.hk/statistics/en/dha_2.htm

IOM (2019) International Migration Law No. 34 - Glossary on Migration. Available from: https://publications.iom.int/books/international-migration-law-ndeg34-glossary-migration

Kong X, Yang Y, Gao J, Guan J, Liu Y, Wang R, Xing B, Ma W (2015) Overview of the health care system in Hong Kong and its referential significance to mainland China. J Chin Med Assoc 78(10):569–573

Lebano A, Hamed S, Bradby H, Gil-Salmerón A, Durá-Ferrandis E, Garcés-Ferrer J et al. (2020) Migrants’ and refugees’ health status and healthcare in Europe: a scoping literature review. BMC Public Health 20(1):1–15

Lu Z, Jin J, Liang Y et al. (2010) Path selection and policy recommendations for the medical security system for migrant workers. Med Philos 6:64–66

Mok F K T (2016) The ethics of admission and rejection of immigrants—the case of children born in Hong Kong to mainland parents. In: Yung B, Kam Por Y (eds.), Ethical dilemmas in public policy, governance and citizenship in Asia. Springer, Singapore

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2021) The seventh national population census bulletin (No. 8) — situation of Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan residents and foreign nationals registered in the census. Available at: https://www.stats.gov.cn/zt_18555/zdtjgz/zgrkpc/dqcrkpc/ggl/202302/t20230215_1904004.html

National Health System, England (2018) Referral to treatment (RTT) waiting times statistics for consultant-led elective care 2017/18 Annual Report. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/06/RTT-Annual-Report-2017-18-PDF-1295K.pdf

Nur ZF, Suryadarma AY, Mengistu AG, Pangestuti A, Ariza NR, Mahmudiono T (2024) Health care access and equity among migrants: a literature review. Med Health Sci J 8(1):51–62

ONS (2018) Migration statistics quarterly report: november 2018. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/releases/migrationstatisticsquarterlyreportnovember2018

PwC China (2024) Integration and mutual benefit: a healthy Greater Bay Area. Available at: https://www.pwccn.com/zh/research-and-insights/greater-bay-area/integration-healthy-sep2024.pdf

Qian Y (2023) Zhuhai explores new model for healthcare insurance integration in the Greater Bay Area, selected as a provincial example. Sohu. Available at https://www.sohu.com/a/663671119_120046696

Ramesh M (2008) Autonomy and control in public hospital reforms in Singapore. Am Rev Public Adm 1:62–79

Ramesh M (2004) Social policy in east and southeast Asia: education, health, housing and income maintenance. Routledge, London

Savas ST, Knipper M, Duclos D, Sharma E, Ugarte-Gurrutxaga MI, Blanchet K (2024) Migrant-sensitive healthcare in Europe: advancing health equity through accessibility, acceptability, quality, and trust. Lancet Reg Health Eur 41:100805

Schmidt AE, Bobek J, Mathis-Edenhofer S, Schwarz T, Bachner F (2022) Cross-border healthcare collaborations in Europe (2007–2017): moving towards a European Health Union? Health Policy 126(12):1241–1247

Shen S (2021) What kind of healthcare security system do we need? Soc Secur Rev 5(1):24–39

Shu G, Jin C, Wang L, Niu H (2024) Key issues and countermeasures for the high-quality development of China’s basic medical security system. Chin Health Econ 43(5):43–47

Siddiki S, Leach WD, Kim J (2017) Diversity, trust, and social learning in collaborative governance. Public Adm Rev 77(6):863–874

Song Y, Bian Y (2020) Development of the health service system and public-private partnership in Macao after 20 years of reunification. Health Econ Res 37(1):15–17

Sun L, Ma X, Shen S (2019) Analysis of the impact of rural-urban population migration on the long-term actuarial balance of basic medical insurance funds—based on the study of regional population development models. Soc Secur Res 4:61–77

Taha N, Siegmann KA, Messkoub M (2015) How portable is social security for migrant workers? a review of the literature. Int Soc Secur Rev 68(1):95–118

Titmuss R (1974). Social policy: an introduction. Allen & Unwin

Wang L, Liang L, Wang Y, Xu W (2023) Insights from Germany’s inter-state medical care and the EU’s cross-border healthcare for China. Chin Health Econ 42(11):88–91

Werding M, McLennan S (2015) International portability of health-cost cover: mobility, insurance, and redistribution. CESifo Econ Stud 61(2):484–519

Wu W (2009) Intense interest game - Challenges and prospects of the US medical security system reform. China Soc Secur 12:22–24

Wu W, Liang Q (2019) Dilemmas of international social security cooperation and the UK’s Brexit actions. Soc Secur Res 2:105–111

Xiong Y (2010) The social foundation of constructing and developing the welfare system in China: a comparative perspective. Comp Econ Soc Syst 5:63–72

Yang H, Leung CB (2010) Welfare regime theory in health care system study: analysis of the health care regime in urban China. Int J Arts Sci 3(8):520–544

Yung B (2016) Justice and taxation: From GST to Hong Kong tax system. In: Yung B, Kam Por Y (eds) Ethical dilemmas in public policy governance and citizenship in Asia. Springer, Singapore

Zeng K (2018) Implications of the EU’s talent mobility policy for the development of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Sci Manag Res 3:87–90

Zhang X, Tian T, Yi X, Sun J (2022) Comparison of medical dispute resolution mechanisms at home and abroad. J Forensic Med 38(2):150–157

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (23BZZ099).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Weidong Wu is the sole author of the paper, wrote the original manuscript and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, W. Promoting collaboration in regional healthcare systems in Hong Kong, Macao, and the mainland of China: midrange strategies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1581 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04105-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04105-y