Abstract

As crucial fixed links of the transportation systems, high bridges play an essential role in overcoming geographical barriers in mountainous areas. Despite their importance, comprehensive evaluations of the collective spatial-temporal effects of multiple high bridges across broad regions are lacking. This study addresses this gap by analyzing the impact of 295 high bridges in Guizhou, China, on travel accessibility and economic potential through spatial analysis under scenarios with and without these bridges. The aim is to quantify their contributions to accessibility and assess their impacts on regional economic integration from 2000 to 2020. The findings reveal that high bridges significantly improved travel accessibility and economic potential within counties, with the average contributions being the greatest for the period 2010–2015 within the whole study period. High bridge construction promoted accessibility convergence and economic integration, reducing regional disparities. The decline in the coefficient of variation (CV) of accessibility demonstrated a converging effect; while the CV of economic potential showed an initial growth followed by a decline. Economically disadvantaged counties gained the most in accessibility and economic potential, highlighting the role of high bridges in regional integration. This study proposes a framework for accurately measuring the economic benefits of high bridges, providing insights for future transport planning in isolated mountainous counties and supporting economic development in regions with underdeveloped transportation infrastructure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mountainous and rugged terrains pose significant transportation challenges in many impoverished regions worldwide. To address these challenges, numerous countries have prioritized the construction of transportation infrastructure as a key strategy for poverty reduction, aiming to improve travel convenience for rural residents and stimulate economic growth. Understanding the impact of such infrastructure on travel accessibility and economic integration is crucial for guiding transportation network planning and regional integrated development. However, while research has extensively explored the overall effects of transportation networks, the spatial impacts of fixed links, such as high bridges, have received less attention.

High bridges are critical in connecting remote areas across deep valleys in mountainous regions. For instance, Guizhou Province in China, which is home to half of the world’s top 100 high bridges, is often referred to as the “world’s highest bridges museum.” The construction of these bridges has substantially alleviated transportation challenges and reduced rural poverty in the region. Given the significant financial investment and technological difficulty required for constructing high bridges (HighestBridges 2019), it is essential to assess their spatial-temporal effects on travel accessibility and economic integration. This is particularly important when considering the location and timing of bridge construction. While this research is focused on China, its implications extend to other developing countries facing similar geographical and socioeconomic challenges.

Although there is extensive literature on the impact of transport infrastructure on accessibility and economic integration (Boonpanya and Masui 2021; Rokicki et al. 2021; Komikado et al. 2021; Wang 2018), the specific effects of fixed links like high bridges in mountainous areas remain underexplored (Nutley 1998). While some studies have highlighted the benefits of such links (Wu et al. 2017; Andersen et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2020; Mikula and Molnár 2023), distinguishing their impact from that of entire highway or railway networks, particularly in rural areas, is challenging. Meanwhile, the impact of transport infrastructure on economic growth is also debated. Most studies emphasize its positive effects on regional accessibility (Rokicki et al. 2021; Komikado et al. 2021) and economic integration, suggesting that infrastructure like high-speed rail (Wetwitoo and Kato 2017; Monzón et al. 2013) and airports (Mao and Chen 2023) can narrow regional economic disparities. However, others argue that improved accessibility does not always translate to economic growth (Pařil and Viturka 2020; Mao and Chen, 2023; Wang et al. 2020; Tian et al. 2024), due to spatial spillovers and network externalities (Petráš and Květoň 2022). Moreover, traditional research methods, such as structural equation models (Li et al. 2023), difference-in-differences models (Ma et al. 2021), spatial panel analyses (He et al. 2020; Rahman and Majumder 2022; Rahman et al. 2023), system dynamics models (Rothengatter 2017), global spatial autocorrelation model (Du et al. 2018), integrated land use-transport models (Wang et al. 2019), and computable general equilibrium models (Boonpanya and Masui 2021) have been widely used to study the economic impacts of transport infrastructure. However, these methods may not fully capture the spatial heterogeneity of impacts from multiple fixed links across different locations over time. Scenario analysis, despite its potential, has been relatively underutilized in this context (Haider et al. 2021; Meng et al. 2021).

There are thus research gaps in understanding how high bridges impact accessibility across different regions and whether they promote balanced regional accessibility or exacerbate disparities, particularly in impoverished mountainous areas (Cai et al. 2023; Zhu et al. 2023). While existing theories generally support the positive influence of transport infrastructure on economic growth, the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of these effects remains contested (Gao and Li 2022; Guo et al. 2022). More detailed investigations using appropriate methodologies are needed to reconcile these differences and clarify the specific contributions of high bridges to accessibility and economic outcomes.

This study seeks to answer the research question: “What are the collective spatial-temporal impacts of multiple fixed links across a region, and how can their specific effects be distinguished from the broader impacts of the entire transport network?” We use scenario-based analysis to estimate these impacts under different traffic conditions controlled by high bridges, including scenarios with newly constructed high bridges and hypothetical scenarios without them. Focusing on counties in Guizhou, China, from 2000 to 2020, this study quantifies the spatial and temporal variations in accessibility and economic potential due to high bridge construction and tests the hypothesis that high bridges significantly enhance accessibility and promote economic convergence in mountainous regions.

The contribution of this research is threefold. Firstly, it addresses critical theoretical gaps by demonstrating how high bridges enhance travel accessibility and economic potential, promote regional economic integration, and reduce disparities (Rokicki et al. 2021) in the context of rural and underdeveloped areas (Zhang and Cheng 2023). Secondly, it quantifies the contribution of high bridges to accessibility and economic potential, distinguished these effects from the impacts of the entire road or railway transport network. Thirdly, it presents a research framework for precisely assessing the accessibility impact of fixed links like high bridges through scenario simulation and GIS spatial analysis. Additionally, this study offers practical insights for policymakers to determine the optimal sequence and locations of high bridge construction, ultimately supporting regional economic development.

The following section reviews the literature on the impact of transport infrastructure on travel accessibility and economic integration. Subsequently, section 3 introduces the research methods, followed by a summary of the results in Section 4. Finally, the policy implications of this study are provided, and the main conclusions are summarized.

Literature review

The impact of transport infrastructure on travel accessibility

Hansen (1959) introduced the concept of travel accessibility to measure interaction opportunities within a transportation network. Morris et al. (1978) later expanded it to include personal preferences and ease of location changes, making it a central focus in regional economics and economic geography (Maroto and Zofío 2016). While transport infrastructure is generally believed to enhance travel accessibility by facilitating economic and technological exchanges (Wu et al. 2015), the relationship exhibits significant spatial variation. Studies on highways, railways, and ports show that the benefits of transport development on accessibility are unevenly distributed (Maroto and Zofío 2016; Gao and Li 2022; Guo et al. 2022). For example, high-speed railways can increase disparities between connected and non-connected areas (Cascetta et al. 2020), and the impact of expressways on accessibility varies, with greater improvements often observed in areas farther from city centers (Martin et al. 2010). Thus, while transport infrastructure undoubtedly improves accessibility, it is debatable whether it promotes balanced regional development or exacerbates disparities.

In rural areas, characterized by low population density and underdeveloped transport systems, accessibility significantly lags behind urban areas (Cai et al. 2023). This issue is particularly acute in developing countries with inadequate transport infrastructure and low car ownership. Research on rural transport systems, especially in impoverished mountainous regions, remains limited (Maroto and Zofío 2016; Guo et al. 2022). Due to limited infrastructure investment and challenging terrain, these areas often lack sufficient transport facilities, hindering the flow of people, capital, information, and resources (Cai et al. 2023). Transport infrastructure is thus a critical constraint on local economic development in rural regions (Zhu et al. 2023). However, the extent to which transport infrastructure affects travel accessibility in rural areas requires further investigation.

The impact of transport infrastructure on economic integration

The regional economic effects of transport infrastructure are grounded in theories across various disciplines. Classical location theory, endogenous growth theory, and new economic geography all emphasize transport costs as key factors shaping the spatial patterns of economic activity. Transport economics considers the broader economic impacts of transport projects, including welfare, social inclusion, equity, and environmental quality (Rodrigue et al. 2009; Roberts et al. 2019; Li et al. 2022). Despite general agreement on the positive impacts of transport infrastructure on accessibility and economic development, its spatially uneven effects remain controversial (Rokicki et al. 2021). Some regions benefit from transport development, while others, especially remote areas, may see little impact or even negative effects (Rodrigue et al. 2009; Rokicki et al. 2021). In endogenous growth theory, infrastructure investment’s externalities are considered a key driver of long-term economic growth, with transport infrastructure viewed as a form of physical capital with significant external benefits (Zhang and Cheng 2023). Neoclassical economic theory integrates transport infrastructure with technological and policy factors to influence economic growth. For instance, Agénor (2010) and Lakshmanan (2011) used neoclassical growth models to show that transport infrastructure enhances economic growth by making other inputs more productive.

Drawing on these theories, empirical studies have used spatial analysis to explore the relationship between transport development and economic growth. Many scholars highlight the crucial role of transport infrastructure, including roads (Wan et al. 2024), railways (Wong et al. 2021; Alotaibi et al. 2022), airports (Zhang and Xie 2023), ports (Li et al. 2023) and bridges (Park et al. 2014), in supporting economic development (Torrisi 2009). However, empirical findings vary due to differences in research focus, timeframes, and methodology. Some argue that transport infrastructure stimulates economic growth by creating demand, expanding markets, facilitating industrial agglomeration, promoting the flow of factors, accelerating technological innovation, and reducing transportation costs (Bernard et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2022; Xie et al. 2017; Wetwitoo and Kato 2017). Others suggest that its short-term effects may be insignificant and that it may not always contribute to regional economic growth (Zhang and Cheng 2023).

For developing countries, improving transport infrastructure is a common strategy to boost regional development and competitiveness (Batool and Goldman 2021; Centurião et al. 2024; Kadyraliev et al. 2022). However, some studies argue that it may hinder growth by displacing private investment (Hooper et al. 2021). The spatial impact of transport infrastructure on economic growth is thus uncertain. Ignoring transportation’s inherent spatial spillover and network externalities, the developmental impact on surrounding regions’ economies may vary (Petráš and Květoň 2022). To address this research gap, this study aims to assess whether enhancing transport infrastructure can reduce regional economic disparities and promote economic integration.

The regional impact of bridges

The construction of large-scale transportation infrastructure, such as highways, railways, and airports, can significantly compress spatial and temporal distances, accelerate the flow of factors, improve resource utilization efficiency, and promote the development of spatial structures and socio-economic systems (Wu et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2017). However, bridges, as vital fixed links in transportation system, have not been extensively studied. With the ongoing advancement of bridge construction worldwide, some research has begun to focus on the impact of cross-sea bridges (Wang et al. 2017; Wu et al. 2017) and cross-river bridges (Liu et al. 2020) on regional transportation and socio-economic development. These studies have found that bridges effectively connect regional transportation networks on either side of a strait, greatly improving transportation convenience, enhancing economic ties, and promoting regional integration (Hou and Li 2011). Additionally, bridges can reduce the cost of factor flow, optimize resource allocation, and facilitate industrial transformation and coordinated development (Meijers et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2017). While these studies have revealed the regional impact of bridges, there is still a lack of attention to the effects of high bridges in impoverished mountainous areas. Moreover, most existing studies have focused on single bridges and have not adequately addressed the spatial-temporal impacts of multiple bridges. Furthermore, the impact of bridges has not been adequately distinguished from that of the entire highway or railways network, which hinders accurate assessment of their economic benefits.

Research gaps

This review identifies several research gaps. First, the extent to which new transport infrastructure promotes balanced regional accessibility or exacerbates disparities, particularly in impoverished mountainous areas, remains unclear. Second, the spatial impact of transport infrastructure on economic growth is uncertain, especially concerning high bridges. Moreover, previous studies have lacked GIS-based scenario analysis. This paper addresses these gaps by examining the differential impact of high bridges, which are essential links in mountainous transportation networks, on travel accessibility and economic integration. It aims to determine whether high bridges can promote the coordinated development of accessibility and economic growth in mountainous areas through spatial analysis and scenario simulation.

Research methods

Theoretical framework

This study develops a theoretical framework to analyze the spatial impacts of high bridges (Fig. 1). The framework is based on the group selection theory from social psychology, contrasting two conditions: the prosocial condition and the egoistic condition. The prosocial condition focuses on decision-making that leads to greater benefits for society as a whole, while the egoistic condition prioritizes benefits for the individual or a specific group (Alcock 2017). This theoretical foundation helps to understand the balance between collective and individual interests in infrastructure investment strategies, which typically seek to achieve both efficiency and equity. The development of high bridges and highways is influenced by four key aspects: social and economic sustainable development needs, national and regional development strategies, the evolution of transportation modes, and transport infrastructure planning and layout (Cai et al. 2023). The spatial impacts of transport infrastructure are theoretically linked to six core concepts: location, distance, fixedness, attributes, relativity, and dynamics (Rodrigue et al. 2009). As transport improvements can transform spatial structures, locations that were once peripheral may become central, affecting their linked areas. However, measuring the spatial impacts of fixed transport infrastructure, especially high bridges in mountainous regions, is challenging. High bridges typically connect to the road network, forming part of the highway system. This study examines how high bridge construction affects accessibility and economic potential in mountainous regions, where shifts from peripheral to central locations can significantly alter spatial structures. It uses quantitative methods to assess the contribution of bridge construction to accessibility and economic potential, comparing scenarios with and without new high bridges, and analyzing the resulting impacts on accessibility convergence and economic integration using the coefficient of variation (CV).

The figure illustrates the theoretical framework, which follows the “process- pattern- impact” logic. In geography, this framework is based on a sequential and causal understanding of geographical phenomena. “Process” refers to the underlying mechanisms and dynamics that drive change in a system, such as the development of high bridges within transportation networks. “Pattern” denotes the observable spatial and temporal arrangements that result from the evolution of high bridges, including changes in travel accessibility and economic potential, as seen in both the business-as-usual and what-if scenarios. Finally, “impact” involves assessing the broader consequences of these patterns on regional accessibility and economic integration by comparing the two scenarios.

Study area

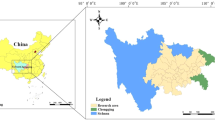

Guizhou Province in southwestern China is selected for this study due to its unique geographical, infrastructural and socio-economic characteristics (Fig. 2). The province comprises 6 prefecture-level cities, 3 autonomous prefectures, and 88 county-level regions. It spans latitude 24°37’ to 29°13’ N and longitude 103°36’ to 109°35’ E. As part of the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, Guizhou features high altitudes and steep terrains, with an average elevation of about 1100 meters. According to China’s third national land survey, approximately 61.01% of the land in Guizhou has a slope greater than 25°, and 16.91% has a slope between 15° and 25° (The People’s Government of Guizhou Province 2021). The province’s mountainous terrain and karst formations have historically posed significant transportation challenges, contributing to persistent poverty among rural residents. Improving transportation has been a key strategy for poverty alleviation in the region. From 2000 to 2020, Guizhou achieved highway access to every county and road connectivity to all villages. During this period, road network density increased from 0.20 to 1.17, and the number of impoverished counties dropped from 48 to 0. The construction of high bridges has played a crucial role in this transformation, significantly improving connectivity and reducing poverty (Cai et al. 2023).

The figure illustrates the geographical distribution of newly constructed high bridges within various counties of Guizhou Province during distinct time intervals: 2000–2005, 2005–2010, 2010–2015, and 2015–2020. All the locations of high bridges are marked on the map by the authors using the ArcGIS platform, based on the location and year of completion information for each high bridge sourced from the list of the world’s 3000 highest bridges (HighestBridges 2019).

Data source and processing

This study quantifies the spatial-temporal impacts of multiple high bridges across a region and distinguishes their specific effects from the broader road network. It examines the effects of high bridges on accessibility convergence and economic integration. Traditional methods for assessing the economic impact of transport infrastructure often focus on single projects or entire road networks, which may not reveal the spatial heterogeneity of multiple fixed links’ impacts at different locations over time. To address this limitation, this study employs scenario-based analysis (Park et al. 2014) for a direct and effective quantitative assessment of the spatial-temporal effects of specific high bridges or clusters of high bridges.

This study simplifies scenarios into two main categories: the business-as-usual scenario, which includes all newly constructed high bridges, and the what-if scenario, which assumes no newly constructed high bridges. The study period from 2000 to 2020 is divided into four intervals: 2000–2005, 2005–2010, 2010–2015, and 2015–2020. By integrating scenario analysis with accessibility and economic potential models from transport geography, the study analyzes the spatial dynamics of travel accessibility and economic potential at the county level under two scenarios for each interval. Comparing the outcomes of the business-as-usual and what-if scenarios allows for precise measurement of the spatial variances in the impact of high bridges across counties. This analysis investigates the extent to which high bridges construction fosters regional accessibility convergence and economic integration. Additionally, the study calculates the CV for both travel accessibility and economic potential across the region under both scenarios at four time points: 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020. This provides a robust measure of the variability in high bridges’ impacts on accessibility and economic potential across the region. Figure 3 illustrates the procedure used to examine the spatial impact of high bridges on travel accessibility and economic integration.

The figure illustrates the step-by-step process of applying various methods and models in this study, encompassing input data, analytical techniques, statistical models, and their corresponding research objectives. Spatial analysis is used to evaluate the accessibility and economic potential of counties in Guizhou Province based on the road network under scenarios with and without high bridges. By comparing results under different scenarios, the contribution of high bridges to the spatial impact on accessibility and economic potential can be quantified, thus evaluating the impact of high bridges on accessibility convergence and economic integration.

Data collection

This study gathers comprehensive data to analyze the spatial-temporal impacts of high bridges in Guizhou Province from 2000 to 2020. The data sources and processing methods are as follows:

(1) Road Network Data: The road network data are obtained from the National Earth System Science Data Center, National Science and Technology Infrastructure of China (2020). The data are available at a scale of 1: 250,000, providing detailed coverage of the region’s transportation infrastructure.

(2) High Bridge Data: High bridge information is derived from the list of the world’s 3000 highest bridges (HighestBridges 2019). This comprehensive list includes critical details such as the name, height, length, location, and year of completion for each high bridge (Table 1). The exact locations of these bridges are meticulously marked on the road network map of Guizhou using the ArcGIS platform, providing a clear visual representation of their spatial distribution (Fig. 4).

The figure illustrates the changes of road networks in the years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020, as well as the distribution of high bridges on road networks. All the road network data are obtained from the National Earth System Science Data Center, National Science & Technology Infrastructure of China (2020).

(3) Digital Elevation Model (DEM) Data: The DEM data, crucial for understanding the terrain and its impact on accessibility, are 30-m resolution digital elevation data from the Global Digital Elevation Model Version 2. These data are downloaded from the Geospatial Data Cloud website (2019) and are processed by splicing, merging and cropping to fit the study area’s requirements.

(4) Socioeconomic Data: Socioeconomic data, essential for analyzing the economic potential and integration, are sourced from the statistical yearbooks of Guizhou for each year within the study period. These data provide insights into the region’s economic development and population dynamics.

Spatial analysis

Accessibility model

Accessibility, a key measure of transport efficiency and interconnectivity (Sarlas et al. 2020), is quantified by the average shortest travel time, with higher values indicating lower accessibility. The process for calculating travel accessibility is as follows:

1) Rasterization of Road Network: The vector data of the road network are converted into a raster format with 1 km by 1 km grids. This process allows for a more granular analysis of travel times across different areas.

2) Speed Value Assignment: Speed values are assigned to the road network grids based on the type of road (Tables 2 and 3). This assignment is crucial as it influences the calculation of travel times.

3) Speed Cost Grid Conversion: The speed cost grid is transformed into a time cost grid, which is essential for determining the shortest travel times. The 88 counties in Guizhou Province are treated as nodes in the transport network.

4) GIS Spatial Analysis: Using the cost distance function in ArcGIS, the shortest cumulative travel time between county nodes is calculated in hours. This function is instrumental in determining the most efficient routes between different locations.

5) Aggregation of Travel Times: The average shortest travel time for each county is extracted and aggregated, providing a regional measure of accessibility.

The formula for average shortest travel time is:

where Ti is the average shortest travel time of county i; tij is the shortest cumulative travel time between two nodes; i and j are counties; and n is the total number of counties in Guizhou Province.

Economic potential model

The economic potential model, adapted from the gravity model, measures the interaction and influence ability between counties, combining economic indicators (GDP and population) and accessibility. The model evaluates the economic potential of each county by reflecting its capacity to engage in regional economic activities, considering both economic and accessibility factors. The specific formula of the economic potential model is as follows:

where Ei is the economic potential of county i; Pj is the GDP of county j; Uj is the resident population of county j; Tij is the average shortest travel time between county i and county j; n is the total number of counties in Guizhou Province; and a is the distance friction coefficient between county i and county j, with a value of 1 in this study.

Scenario analysis

This study uses scenario analysis to assess the impact of high bridge construction on travel accessibility and economic potential in Guizhou Province. From 2000 to 2020, 295 high bridges were built, significantly expanding the road network. To quantify the contribution of bridge construction to travel accessibility, two scenarios are analyzed (Table 4):

(1) Business-as-Usual Scenario (With High Bridge Construction): In this scenario, the high bridges and the regional road network are assumed to remain unchanged, reflecting the actual development that has occurred.

(2) What-If Scenario (Without High Bridge Construction): In this hypothetical scenario, the roads adjacent to the high bridges are conceptually “broken down,” simulating a situation where the bridges were not constructed. This scenario is created by applying spatial analysis techniques on the ArcGIS platform, as referenced in the work of Shan et al. (2023).

Statistical analysis

To quantify the impact of high bridges on travel accessibility and economic potential, we calculated the contribution of high bridges for each county using data obtained from two scenarios. The calculation formula for contribution is as follows:

where Di represents the contribution of high bridges to a specific indicator (travel accessibility/economic potential); Vi,b is the indicator value of county i under the business-as-usual scenario (with high bridge construction); Vi,w is the indicator value for county under the what-if scenario (without high bridge construction).

By comparing the business-as-usual scenario with the what-if scenario, this study isolates the specific effects of high bridges from other factors influencing travel accessibility and economic potential.

Considering the regional differences in the impact of high bridges on accessibility and economic potential across different counties, CV was used to measure the degree of disparity. CV is commonly used to reflect the degree of variation and imbalance within a dataset and is widely applied in fields such as finance, statistics, materials science, and ecology (Zhang et al. 2024; Wu and Huang 2023). A higher CV indicates a greater degree of disparity among the samples. The formula for CV is as follows:

where CV represents the variation coefficient of a certain indicator, n is the total number of counties, Vi is the indicator value for county i.

Results

Business-as-usual scenario of regional accessibility

Using the inverse distance weighting (IDW) function, we interpolated the average shortest travel time of each county node in Guizhou Province to map the spatial distribution of travel accessibility from 2000 to 2020 (Fig. 5). Over the study period, the accessibility gap among Guizhou’s counties narrowed signficantly. In 2000, Yunyan District in Guiyang City had the shortest average travel time (2.97 h), while Chishui City had the longest (8.94 h), presenting a maximum accessibility value difference of nearly six hours between counties. By 2020, the gap reduced to 2 h and 44 min, with the Yunyan District having the shortest average travel time of 2.08 h and Leishan County the longest at 4.52 h. This reduction in the accessibility gap highlights improved county-to-county connectivity. Accessibility differences between the northwest and northeast regions of Guizhou also diminished, with the isolines indicating significant accessibility disparities among counties becoming less dense. Simultaneously, travel accessibility within counties improved consistently. By 2015, Guizhou had achieved expressway connectivity among all counties, promoting more balanced regional accessibility. As shown in Fig. 6, around 30% of Guizhou’s counties experienced a reduction in average travel time of more than 2 h, 63% saw a reduction of 1–2 h, and 7% had a decrease of less than 1 h. Notably, Chishui City saw the most significant improvement, with average travel time dropping from 8.94 h in 2000 to 4.05 h in 2020—a decrease of 4.89 h.

Figure (a) Illustrates the percentage of accessibility distribution among counties at different average shortest travel time levels in 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020. Figure (b) presents the cumulative percentage of accessibility distribution among counties at different average shortest travel time level across the specific years.

In terms of spatial distribution, Guizhou’s counties exhibited a “core-periphery” accessibility pattern, with accessibility decreasing unevenly from the central region to the outer periphery. Peripheral areas experienced local fragmentation, with low accessibility prevalent in the northwest, northeast, and southwest regions, while high accessibility was concentrated in the central area. In 2000, the highest average travel times were in peripheral counties like Chishui City and Xishui County in the northwest and Songtao County in the northeast. As transport infrastructure developed, these high-travel-time areas expanded across Guizhou’s periphery. Conversely, counties with shorter travel times, primarily in Guiyang City, were centered in the province, with this influence gradually spreading to neighboring counties. Over the past two decades, both highest and lowest average travel times across Guizhou’s counties have decreased, with high-travel-time zones expanding in peripheral areas and low-travel-time regions in the center shrinking, indicating a move towards balanced accessibility.

What-if scenario of regional accessibility

To assess the impact of high bridges on travel accessibility in Guizhou, we analyzed a what-if scenario without high bridge construction and compared it to the business-as-usual scenario. Figure 7 illustrates the spatiotemporal distribution and variation of travel accessibility in Guizhou Province concerning new high bridge inaugurations between 2000 and 2020. It also shows the spatial distribution of accessibility in Guizhou Province before and after the opening of new high bridges during 2000–2005, 2005–2010, 2010–2015, and 2015–2020. By comparing the scenarios in Fig. 7, it is evident that the completion of high bridges significantly altered regional accessibility in both time and space.

This figure illustrates the average shortest travel time of each county node within Guizhou Province under two scenarios: the business-as-usual scenario, which considers the presence of new high bridges, and the what-if scenario, which excludes new high bridges. It also highlights the contrast between these two scenarios for the years 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020.

Temporally, the average travel time across counties decreased significantly following the opening of new bridges. These reductions included a 40 min maximum drop after 15 new bridges were opened from 2000 to 2005, a 73 min decrease with the inauguration of 29 bridges from 2005 to 2010, a 56-min drop after 102 bridges between 2010 and 2015, and a 53 min reduction with 149 bridges from 2015 to 2020. The number of new high bridges increased 3.5 times from 2000 to 2015, greatly enhancing Guizhou Province’s road transport network and improving inter-county connectivity. By the end of 2015, every county in Guizhou Province had highway access, reflecting comprehensive transport infrastructure development. Post-2015’s 149 new high bridges were built on an already extensive road network, resulting in a reduced accessibility impact, indicating a diminishing marginal return on the effect of high bridges. Overall, each period saw improvements in travel accessibility, transitioning from rapid enhancements to more gradual ones, with the most marked improvement between 2010 and 2015.

Spatially, despite the introduction of high bridges in all four periods, the distribution of travel accessibility across Guizhou’s counties largely remained constistent, with a layered decrease from central regions to the outer periphery. Central Guizhou predominantly remained a high-accessibility area, though it slightly expanded post-bridge construction. In contrast, peripheral regions, traditionally low-accessibility zones, contracted a bit after new high bridges were opened, particularly between 2010–2015 and 2015–2020. The most significant shifts in accessibility between the two scenarios occurred in Guizhou’s peripheral areas. From 2000 to 2005, the most notable accessibility improvement was concentrated in Weining County and Hezhang County lying in western Guizhou Province. From 2005 to 2010, Renhuai City in the northwest and Ceheng County in the south saw more improvement. Between 2010 and 2015, accessibility improvements were most significant in marginal areas, mainly in the northwest (especially Chishui City), the northeast (especially Yinjiang County, Jiangkou County and Sinan County), and the southeast (especially Liping County and Congjiang County) of Guizhou Province. From 2015 to 2020, the focus shifted to the western counties of Guizhou Province, including Hezhang County, Shuicheng County, Nayong County and Puding County. Overall, accessibility improvements were concentrated in counties on the western, northeastern, and southeastern borders, highlighting the critical role of high bridge construction in improving transportation in these traditionally harder-to-reach counties.

The spatial impact of high bridges on travel accessibility

From 2000 to 2020, Guizhou Province maintained a “core-periphery” accessibility spatial pattern, with high accessibility in counties around Guiyang City and low accessibility shifting from Tongren City to Qianxinan Prefecture. The accessibility gap between core and peripheral areas consistently narrowed, with high bridges helping to reduce accessibility disparities. From 2000 to 2005, Guiyang City’s counties had the highest average accessibility at 3.41 h, while Tongren City in the northeastern edge had the lowest at 5.53 h, with a gap of 2.12 h. From 2005 to 2010, the average accessibility of counties in Guiyang City was the highest, reaching 3.19 h, while the lowest average accessibility was in Tongren City, reaching 4.99 h, with a gap of 1.8 h. From 2010 to 2015, the average accessibility of counties in Guiyang City was the highest, reaching 2.73 h, while Qianxinan Prefecture on the southwestern edge of Guizhou Province had the lowest average accessibility of counties, reaching 4.26 h, with a gap of 1.53 h. From 2015 to 2020, the average accessibility of counties in Guiyang City was the highest, reaching 2.30 h, while the lowest average accessibility was in Qianxinan Prefecture, reaching 3.79 h, with a gap of 1.49 h.

As shown in Table 5, the contribution of high bridge construction to enhanced travel accessibility across Guizhou’s counties followed a trend of initial growth followed by a decline, consistent with the law of diminishing marginal utility. The average contributions during 2000–2005, 2005–2010, 2010–2015, and 2015–2020 were 3.00%, 2.60%, 8.38% and 5.36%, respectively. Before 2015, high bridge construction significantly improved travel accessibility in most counties, particularly between 2010 and 2015, when the average contribution was 8.38%. However, post- 2015, the impact of high bridge construction began to diminish. There were distinct regional differences in the effects of high bridge construction on travel accessibility across different counties.

From 2000 to 2005, most counties had a high bridge contribution to travel accessibility under 5%, with 13 counties, mainly peripheral ones, experiencing an increase above 5%. For instance, Weining, Yuqing, and Kaiyang Counties in northern Guizhou saw travel accessibility rise by more than 10%. Between 2005 and 2010, seven counties experienced over a 5% rise in travel accessibility, with border counties like Ce’en County and Renhuai city seeing the most significant increases. From 2010 to 2015, 65 counties saw travel accessibility rise by over 5%, with the highest increases still observed in peripheral areas. From 2015 to 2020, 31 counties experienced over a 5% increase in travel accessibility, with Puding County in western Guizhou experiencing the most substantial growth at 33.78%. Generally, the impact of high bridges on travel accessibility was more pronounced in peripheral and impoverished areas than in central cities.

Since 2015, poverty alleviation became a primary developmental goal for Guizhou Province. By 2020, the last nine impoverished counties in Guizhou achieved poverty alleviation, fulfilling the strategic goals of poverty alleviation in all 66 previously impoverished counties (cities, districts). In 2020, 31 counties, including five that had just achieved poverty alleviation, saw the contribution of newly constructed bridges to travel accessibility rise by over 5%. The most significant impacts were observed in counties like Hezhang and Nayong, both of which achieved poverty alleviation. This indicates that bridge construction notably improved transportation accessibility in less developed regions. The introduction of high bridges primarily affected the connectivity of existing or planned roads, particularly major routes like railways, expressways, and national highways. Consequently, areas near these bridges saw the most substantial accessibility improvements, while counties primarily connected by county and township roads saw smaller impacts.

In the business-as-usual scenario with high bridge construction, the CV of accessibility declined from 0.2521 in 2005 to 0.2100 in 2020, indicating a move toward equilibrium. On the other hand, in the what-if scenario without high bridge construction, the CV of accessibility decreased from 0.2466 in 2005 to 0.2086 in 2020, similarly reflecting a diminishing relative disparity in regional accessibility. While the regional disparity in travel accessibility under the business-as-usual scenario was marginally greater than in the what-if-scenario, the decline in the CV of accessibility was more pronounced in the former. This suggests the spatial converging effect of high bridges on regional accessibility.

The spatial impact of high bridges on economic integration

Figure 8 shows the evolution of the spatial pattern of county-level economic potential in Guizhou Province from 2000 to 2020, before and after the introduction of high bridges. All counties experienced increased economic potential, with those that had new high bridges showing greater gains. The construction of high bridges significantly boosted economic potential, with the minimum value rising from 242 to 1824, the peak from 1256 to 8663, and the average from 544 to 3570. Pearson coefficients between accessibility and economic potential in 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020 were −0.853 (p = 0.000), −0.213 (p = 0.046), −0.193 (p = 0.071), −0.179 (p = 0.095), −0.197 (p = 0.066), respectively. It showed a negative correlation exists between accessibility values and economic potential, more pronounced in 2000 and 2005. This suggests that better accessibility correlates with higher economic potential.

This figure displays the economic potential of each county node in Guizhou Province under two scenarios: the business-as-usual scenario, which incorporates new high bridges, and the what-if-scenario, excluding new high bridges. It also illustrates the impact of new high bridges on economic potential for the years 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020.

Spatially, the distribution of economic potential exhibited a “core-periphery” pattern, with the core areas showing greater expansion and positive spillover effects on surrounding regions. The highest economic potential centered around the southern districts of Guiyang city (including Baiyun District, Nanming District, Yunyan District, Wudang District, Huaxi District, and Guanshanhu District) and its neighboring counties (including Pingba District and Longli County). Areas with lowest economic potential, in contrast, were mainly located in Tongren city (Songtao County), remaining the peripheral region with minimal economic potential. Over the years, counties with more substantial economic potential increases were found in areas with more bridge construction.

Temporally, Table 6 compares the contribution of high bridge construction to county-level economic potential across different years. The average contributions of these bridges to economic potential during 2000–2005, 2005–2010, 2010–2015, and 2015–2020 were 4.83%, 2.78%, 6.73% and 5.25%, respectively. The most significant impact occurred between 2010–2015, with variations among counties. Approximately 60% of counties showed continuous growth, while around 30% saw a rise followed by a decline. High bridges are expected to remain crucial for economic potential.

In the business-as-usual scenario with high bridge construction, the CV of economic potential initially increased from 0.4301 in 2005 to 0.4543 in 2010, but subsequently decreased to 0.3967 by 2020. This pattern suggests a mixed trend of initial growth followed by a decline, which means that regional economic disparity decreased when the high bridges were constructed. On the other hand, in the what-if scenario without high bridge construction, the CV of economic potential kept increasing from 0.3596 in 2005 to 0.4071 in 2020, indicating the substantial regional economic disparities that can emerge in the absence of high bridges. Thus, high bridges are vital for regional economic integration, particularly in mountainous areas.

Discussion

The spatial impact of high bridges

The impact of transport infrastructure on regional development has been debated, with differing views on the effectiveness of transport infrastructure investments in enhancing accessibility and economic growth. While some scholars argue that improving accessibility to urban centers leads to positive socioeconomic outcomes (Weiss et al. 2018), others caution that such developments may merely concentrate resources in already prosperous regions (Pařil and Viturka 2020; Wang et al. 2020). Our study contributes to this debate by demonstrating that high bridges, especially in remote mountainous regions, play a pivotal role in improving accessibility, reducing regional economic disparities, and fostering economic integration. This is particularly evident in regions where high-performing areas are surrounded by zones of low accessibility, as suggested by Freiria et al. (2022). Our findings challenge the notion that infrastructure investments primarily benefit urban centers by showing that high bridges can have a more pronounced positive impact on underdeveloped areas. This outcome highlights the importance of strategic infrastructure development in challenging terrains, where such investments can break down long-standing barriers and stimulate economic and social progress (Cascetta et al. 2020; Martin et al. 2010; Knowles and Matthiessen 2009). Moreover, the rapid development of fixed links in these regions has led to the integration of previously isolated areas into the broader transport network (Gao and Li 2022), underscoring the transformative potential of high bridges in bridging urban-rural divides (Wong et al. 2021; Wan et al. 2024; Alotaibi et al. 2022) and encouraging rural revitalization (Wetwitoo and Kato 2017; Monzón et al. 2013; Mao and Chen 2023).

The evolution of spatial impact of high bridges

The dynamic nature of high bridges’ impact over time is a crucial aspect of our study. By analyzing the coefficient of variation in transport accessibility and economic potential under different scenarios, we observed that high bridges contribute to regional accessibility convergence and economic integration, consistent with the findings of He et al. (2019) and Fageda and Olivieri (2019). As shown in Fig. 9, the spatial impacts on travel accessibility and regional economic integration can be discerned across multiple phases. Initially, natural barriers isolated mountainous counties, but the construction of high bridges and roads has gradually enhanced connectivity, fostering regional interaction and collaboration. As high bridges proliferate, the economic potential of counties following a “core-periphery” model improves, narrowing the gap between core and peripheral areas. However, it is essential to recognize that regional imbalances persist, often due to underdeveloped industries and insufficient funding in peripheral regions. Therefore, while high bridges lay the groundwork for regional integration, complementary policies are needed to attract talent, technology, and investment to underdeveloped counties, ensuring sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

Policy implications

The practical implications of our findings are twofold. First, they provide a theoretical reference for decision-makers in determining the sequence and optimal location of high bridges, emphasizing the importance of considering both immediate accessibility improvements and long-term economic integration. Second, our research offers insights for countries and regions facing similar topographical constraints (Voumik et al. 2022), illustrating how targeted infrastructure investments can bridge the urban-rural divide and promote rural revitalization.

In summary, this study not only advances the methodological framework for assessing transport infrastructure impacts but also contributes to a deeper understanding of the socio-economic dynamics in mountainous regions. Amidst the debate on whether to prioritize efficiency or equity in transport infrastructure investment (Cascetta et al. 2020), the case of Guizhou Province exemplifies a balanced approach to infrastructure investment, where both regional equity and economic efficiency are considered. However, the diminishing marginal benefits of high bridge construction over time suggest that future investments must be carefully planned and predicted using the framework proposed in this paper. By doing so, governments and enterprises can maximize the economic and social benefits of these critical infrastructures, fostering sustainable development in challenging terrains.

Conclusions

This study examines the impact of high bridge construction across 88 counties in Guizhou Province from 2000 to 2020. Two distinct scenarios were formulated: one with and one without the construction of high bridges, to evaluate their influence on accessibility convergence and economic integration. The key findings are as follows:

-

(1)

High bridges construction significantly narrows the gaps in travel accessibility and economic strength among counties, enhancing both accessibility and economic development. Over time, a “core-periphery” pattern emerges, with central central areas consistently outperforming peripheral regions. However, the improvement in accessibility and economic potential due to high bridges varies regionally. The decrease in the CV of accessibility in both scenarios indicates a converging effect, moving regional accessibility toward equilibrium. High bridges reduce disparities between core and peripheral areas, with less developed regions benefiting more than urban centers.

-

(2)

The marginal benefits of bridge construction diminish as transport infrastructure improves. Investors should prioritize enhancing the external road network. Governments must integrate transport development with advancements in industries, talent acquisition, and technology to support rural revitalization after achieving poverty alleviation goals.

-

(3)

This study highlights regional disparities in the impact of high bridges on accessibility and economic potential. Constructing high bridges in peripheral counties is strategic for reducing disparities with central counties and aiding poverty alleviation. The findings offer a practical framework for other developing countries with similar terrain challenges, demonstrating how transport infrastructure can improve accessibility and promote economic integration.

This study makes several theoretical contributions by addressing critical gaps in the literature. It demonstrates that high bridges enhance accessibility, promote economic integration, and reduce regional disparities, particularly in rural and underdeveloped areas. These findings offer valuable insights into the spatial and temporal dimensions of transport infrastructure’s economic benefits and highlight the importance of considering spatial spillover effects and network externalities in future research and policy-making.

Despite its contributions, this study has limitations that suggest future research directions. First, due to limited county-level economic data, only two socioeconomic indicators—resident population and regional GDP—were considered. Second, the estimation of economic potential relies on gravity models, which may not fully capture the economic connections between counties. Future research could incorporate additional socioeconomic factors, such as population dynamics, industrial upgrades, and land-use changes, to better understand how high bridges influence economic integration. Moreover, ongoing infrastructure development can attract foreign investment and further promote economic integration (Majumder et al. 2022; Rahman 2023). Future studies could analyze shifts in travel behaviors and track changes in population, freight, and investment flows due to high bridge construction (Majumder and Rahman 2020) to comprehensively understand its economic impact.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Some additional information is included in the supplementary file.

References

Agénor P (2010) A theory of infrastructure-led development. J Econ Dyn Control 34(5):932–950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2010.01.009

Alcock J (2017) Human Sociobiology and Group Selection Theory. Hum Nat 23:383–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-420190-3.00023-5

Alotaibi S, Quddus M, Morton C, Imprialou M (2022) Transport investment, railway accessibility and their dynamic impacts on regional economic growth. Res Transportation Bus Manag 43:100702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2021.100702

Andersen SN, Gutiérrez MD, Nilsen ØL, Tørset T (2018) The impact of fixed links on population development, housing and the labour market: The case of Norway. J Transp Geogr 68:215–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.03.004

Batool I, Goldman K (2021) The role of public and private transport infrastructure capital in economic growth. Evidence from Pakistan. Res Transportation Econ 88:100886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2020.100886

Bernard AB, Moxnes A, Saito YU (2019) Production networks, geography and firm performance. J Political Econ 127(2):639–688. https://doi.org/10.3386/w21082

Boonpanya T, Masui T (2021) Assessing the economic and environmental impact of freight transport sectors in Thailand using computable general equilibrium model. J Clean Prod 280(1):124271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124271

Cai J, Huang C, Deng Z, Li L (2023) Transport Accessibility and Poverty Alleviation in Guizhou Province of China: Spatiotemporal Pattern and Impact Analysis. Sustainability 15(4):3143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043143

Cascetta E, Cartenì A, Henke I, Pagliara F (2020) Economic growth, transport accessibility and regional equity impacts of high-speed railways in Italy: ten years ex post evaluation and future perspectives. Transportation Res Part A: Policy Pract 139:412–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2020.07.008

Centurião D, Abrita MB, Neto AR, Camilo AP, Vignandi RS et al. (2024) Impacts of road transport infrastructure investments on the Latin American Integration Route. Regional Sci Policy Pract 16(8):100061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rspp.2024.100061

Du H, Chen Z, Mao G, Li R, Chai L (2018) A spatio-temporal analysis of low carbon development in China’s 30 provinces: A perspective on the maximum flux principle. Ecol Indic 90:54–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.02.044

Fageda X, Olivieri C (2019) Transport infrastructure and regional convergence: A spatial panel data approach. Pap Regional Sci 98(4):1609–1631. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12433

Freiria S, Sousa N, Calvo-Poyo F (2022) Spatial analysis of the impact of transport accessibility on regional performance: A study for Europe. J Transp Geogr 102:103371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103371

Gao D, Li S (2022) Spatiotemporal impact of railway network in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau on accessibility and economic linkages during 1984–2030. J Transp Geogr 100:103332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103332

Geospatial Data Cloud (2019) 30-m resolution digital elevation data. http://www.giscloud.cn. Accessed 21 Feb 2023

Guo J, Wang Z, Yu X (2022) Accessibility measurement of China’s coastal ports from a land-sea coordination perspective - An empirical study. J Transp Geogr 105:103479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103479

Haider J, Sanchez RV, Pettit SJ, Harris I, Beresford AKC, Shi Y (2021) Economic and environmental impacts of alternative routing scenarios in the context of China’s belt and road initiative. Marit Transp Res 2:100030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.martra.2021.100030

Hansen WG (1959) How accessibility shapes land-use. J Am Inst Plan 25(2):73–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944365908978307

He D, Yin Q, Zheng M, Gao P (2019) Transport and regional economic integration: Evidence from the Chang-Zhu-Tan region in China. Transp Policy 79:193–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2019.04.015

He Y, Lv B, Yu D (2020) How does spatial proximity to the high-speed railway system affect inter-city market segmentation in China: a spatial panel analysis. Eurasia Geogr Econ 63(1):55–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1828122

HighestBridges (2019) World’s Highest Bridges. https://www.highestbridges.com/wiki/index.php?title=Main_Page. Accessed 21 Feb 2023

Hooper E, Peters S, Pintus PA (2021) The impact of infrastructure investments on incomeinequality: Evidence from US states. Econ Transit Institutional Change 29(2):173–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecot.12266

Hou Q, Li S (2011) Transport infrastructure development and changing spatial accessibility in the Greater Pearl River Delta, China, 1990–2020. J Transp Geogr 19(6):1350–1360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.07.003

Kadyraliev A, Supaeva G, Bakasa B, Dzholdosheva T, Dzholdoshev N et al. (2022) Investments in transport infrastructure as a factor of stimulation of economic development. Transportation Res Procedia 63:1359–1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2022.06.146

Knowles RD, Matthiessen CW (2009) Barrier effects of international borders on fixed link traffic generation: the case of Øresundsbron. J Transp Geogr 17(3):155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2008.11.001

Komikado H, Morikawa S, Bhatt A, Kato H (2021) High-speed rail, inter-regional accessibility, and regional innovation: Evidence from Japan. Technol Forecast Soc Change 167:120697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120697

Lakshmanan TR (2011) The broader economic consequences of transport infrastructure investments. J Transp Geogr 19(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.01.001

Li L, Cai J, Chen W (2023) How does transport development contribute to rural income in China? Evidence from county-level analysis using structural equation model. Travel Behav Soc 34:100708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2023.100708

Li Q, Qian R, Gao J, Huang J (2022) Environmental impacts and risks of bridges and tunnels across lakes: An overview. J Environ Manag 319:115684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115684

Li W, Bai X, Yang D, Hou Y (2023) Maritime connectivity, transport infrastructure expansion and economic growth: A global perspective. Transportation Res Part A: Policy Pract 170:103609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2023.103609

Liu W, Cao Y, Wu W, Guo J (2020) Spatial impact analysis of trans-Yangtze highway fixed links: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta, China. J Transp Geogr 88:102822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102822

Liu Z, Zeng S, Jin Z, Shi JJ (2022) Transport infrastructure and industrial agglomeration: Evidence from manufacturing industries in China. Transp Policy 121:100–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2022.04.001

Ma Q, Jia P, She X, Haralambides H, Kuang H (2021) Port integration and regional economic development: Lessons from China. Transp Policy 110:430–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.06.019

Majumder SC, Rahman MH (2020) Impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth of China After economic reform. J Entrepreneurship, Bus Econ 8(2):120–153. http://scientificia.com/index.php/JEBE/article/view/140

Majumder SC, Rahman MH, Martial AAA (2022) The effects of foreign direct investment on export processing zones in Bangladesh using Generalized Method of Moments Approach. Soc Sci Humanit Open 6:100277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2022.100277

Mao X, Chen X (2023) Does airport construction narrow regional economic disparities in China? J Air Transp Manag 108:102362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2023.102362

Maroto A, Zofío JL (2016) Accessibility gains and road transport infrastructure in Spain: A productivity approach based on the Malmquist index. J Transp Geogr 52:143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2016.03.008

Martin JC, García-Palomares JC, Gutiérrez J, Román C (2010) Efficiency and equity of orbital motorways in Madrid. J Transp Land Use 3(1):67–84. https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.v3i1.106

Meijers E, Hoekstra J, Leijten M, Louw E, Spaans M (2012) Connecting the periphery: distributive effects of new infrastructure. J Transp Geogr 22:187–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.01.005

Meng L, Li RYM, Taylor MAP, Scrafton D (2021) Residents’ choices and preferences regarding transit-oriented housing. Aust Plan 57(2):85–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2021.1936094

Mikula Š, Molnár P (2023) Expected transport accessibility improvement and house prices: Evidence from the construction of an undersea road tunnel system. J Transp Geogr 111:103649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2023.103649

Monzón A, Ortega E, López E (2013) Efficiency and spatial equity impacts of high-speed rail extensions in urban areas. Cities 30:18–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2011.11.002

Morris JM, Dumble PL, Wigan MR (1978) Accessibility indicators for transport planning. Transportation Res Part A: Gen 13(2):91–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-2607(79)90012-8

National Earth System Science Data Center, National Science & Technology Infrastructure of China (2020) Road traffic data in Guizhou Province. https://www.geodata.cn. Accessed 21 Feb 2023

Nutley S (1998) Rural areas: the accessibility problem. Mod Transp Geogr 2:185–215. http://worldcat.org/isbn/1852931582

Pařil V, Viturka M (2020) Assessment of Priorities of Construction of High-Speed Rail in the Czech Republic in Terms of Impacts on Internal and External Integration. Rev Economic Perspect 20(2):217–241. https://doi.org/10.2478/revecp-2020-0010

Park J, Kwon C, Son M (2014) Economic implications of the Canada–U.S. border bridges: Applying a binational local economic model for international freight movements. Res Transportation Bus Manag 11:123–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2014.06.003

Petráš M, Květoň V (2022) Spatial patterns of transport accessibility and traffic load in Czechia: towards a typology of the new road infrastructure impacts. J Maps 18(1):33–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2022.2035265

Rahman MH (2023) Does the current account balance influence foreign direct investment in the Indian economy? Application of quantile regression model. SN Bus Econ 3:94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-023-00471-y

Rahman MH, Majumder SC (2022) Empirical analysis of the feasible solution to mitigate the CO2 emission: evidence from Next‑11 countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29:73191–73209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-20908-5

Rahman MH, Chowdhury MA, Akter MS (2023) Interaction of market size, inflation and trade openness on foreign direct investment inflows in India, China and Japan: panel dynamic analysis. Int J Indian Cult Bus Manag 29(1):45–64. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJICBM.2023.130963

Roberts M, Melecky M, Bougna T, Xu YS (2019) Transport corridors and their wider economic benefits: A quantitative review of the literature. J Regional Sci 60(3):207–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12467

Rodrigue JP, Comtois C, Slack B (2009) The Geography of Transport Systems, second edition. Taylor & Francis Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429346323

Rokicki B, Haddad EA, Horridge JM, Stępniak M (2021) Accessibility in the regional CGE framework: the effects of major transport infrastructure investments in Poland. Transportation 48:747–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-019-10076-w

Rothengatter W (2017) Wider economic impacts of transport infrastructure investments: Relevant or negligible? Transp Policy 59:124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.07.011

Sarlas G, Páez A, Axhausen KW (2020) Betweenness-accessibility: Estimating impacts of accessibility on networks. J Transp Geogr 84:102680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102680

Shan M, Wang Y, Lu Y, Liang C, Wang T, Li L, Li RYM (2023) Uncovering PM2.5 transport trajectories and sources at district within city scale. J Clean Prod 423:138608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138608

The People’s Government of Guizhou Province (2021) Main data bulletin of the third National Land Survey of Guizhou Province. Accessed 21 Feb 2023. Retrieved from https://www.guizhou.gov.cn/zwgk/zdlygk/jjgzlfz/zrzy/zrzydcjcgl/202201/t20220121_72378280.html

Tian Z, Hu A, Yang Z, Lin Y (2024) Highway networks and regional poverty: Evidence from Chinese counties. Struct Change Economic Dyn 69:224–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2023.12.010

Torrisi G (2009) Public infrastructure: definition, classification and measurement issues. Econ, Manag, Financial Mark 4(3):100–124. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/12990/

Voumik LC, Rahman MH, Hossain MS (2022) Investigating the subsistence of Environmental Kuznets Curve in the midst of economic development, population, and energy consumption in Bangladesh: imminent of ARDL model. Heliyon 8:10357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10357

Wan J, Ma C, Jiang T et al. (2024) A spatial econometric investigation into road traffic accessibility and economic growth: insights from the Chengdu-Chongqing twin-city economic circle. Humanities Soc Sci Commun 11:183. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02695-1

Wang C, Lim MK, Zhang X, Zhao L, Lee PT (2020) Railway and road infrastructure in the Belt and Road Initiative countries: Estimating the impact of transport infrastructure on economic growth. Transportation Res Part A: Policy Pract 134:288–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2020.02.009

Wang L (2018) High-speed rail services development and regional accessibility restructuring in megaregions: A case of the Yangtze River Delta, China. Transp Policy 72:34–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2018.09.015

Wang W, Zhong M, Hunt JD (2019) Analysis of the Wider Economic Impact of a Transport Infrastructure Project Using an Integrated Land Use Transport Model. Sustainability 11(2):364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020364

Wang Z, Xu G, Bao C, Xu J, Sun F (2017) Spatial and economic effects of the Bohai Strait Cross-Sea Channel on the transportation accessibility in China. Appl Geogr 83:86–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.04.002

Weiss DJ, Nelson A, Gibson HS et al. (2018) A global map of travel time to cities to assess inequalities in accessibility in 2015. Nature 553:333–336. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25181

Wetwitoo J, Kato H (2017) Inter-regional transportation and economic productivity: a case study of regional agglomeration economies in Japan. Ann Regional Sci 59(2):321–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-017-0833-6

Wong Z, Li R, Peng D, Kong Q (2021) China-European railway, investment heterogeneity, and the quality of urban economic growth. Int Rev Financial Anal 78:101937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101937

Wu J, Zhang Y, Zukerman M, Yung EK (2015) Energy-efficient base-stations sleep-mode techniques in green cellular networks: a survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor 17(2):803–826. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2015.2403395

Wu Q, Fan J, Zhang H, Ye Y (2017) The spatial impacts model of trans-strait fixed links: A case study of the Pearl River Delta, China. J Transp Geogr 63:30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.07.003

Wu X, Huang X (2023) Screening of urban environmental vulnerability indicators based on coefficient of variation and anti-image correlation matrix method. Ecol Indic 150:110196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110196

Xie R, Fang J, Liu C (2017) The effects of transportation infrastructure on urban carbon emissions. Appl Energy 196:199–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.01.020

Zhang H, Xie T (2023) A key to urban economic growth or an unnecessary burden? Opening airports in small and medium-sized cities. Cities 133:104105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.104105

Zhang S, Hu X, Wang J, Zhou P, Ren X (2024) Optimal design of adaptive EWMA monitoring schemes for the coefficient of variation and performance evaluation with measurement errors. Computers Ind Eng 191:110107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2024.110107

Zhang Y, Cheng L (2023) The role of transport infrastructure in economic growth: Empirical evidence in the UK. Transp Policy 133:223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2023.01.017

Zhu M, Wang Z, Chi H, Yang Y, Qie P (2023) Situation and hotspot analysis on rural transport infrastructure from the perspective of bibliometric analysis. J Traffic Transportation Eng (Engl Ed) 10(6):1074–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtte.2023.04.009

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the data support provided by the National Earth System Science Data Center, National Science & Technology Infrastructure of China. (http://www.geodata.cn). This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42293272, 42071227).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiayuan Cai: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization, Visualization. Zilin Deng: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Conceptualization, Visualization. Linna Li: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, J., Deng, Z. & Li, L. The spatial impact of high bridges on travel accessibility and economic integration in Guizhou, China: a scenario-based analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1565 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04106-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04106-x