Abstract

On the basis of the unbalanced panel financial data of Chinese commercial banks from 2007–2021, this paper first conducts an identification test of the bank risk-taking channel for China’s monetary policy transmission. Then, it tests the impact of bank microcharacteristics and macroeconomic fluctuations on bank risk-taking in monetary policy transmission. The empirical results reveal the presence of the risk-taking channel for China’s monetary policy transmission. China’s bank risk-taking in monetary policy transmission is asymmetric because of the heterogeneity of bank microcharacteristics and macroeconomic fluctuations; i.e., the larger the asset size is, the greater the capital adequacy ratio is, the greater the return on net assets is, the greater the risk-taking level is, and the lower the risk-taking level of banks with poorer liquidity and higher branch coverage is. The impact of macroeconomic fluctuations is reflected in the fact that the higher the economic growth rate is, the greater the risk-taking level of banks. Therefore, it is necessary to enhance the transparency of monetary policy, strengthen the supervision of commercial banks, stabilize the macroeconomic environment, match the risk-taking level of banks with monetary credit and economic growth, and improve the effect of monetary policy transmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global financial crisis that began in the United States of America in 2008 has raised questions about the effectiveness of loose monetary policies. This was because the monetary policy, which was characterized mainly by “quantitative easing”, led to a prolonged period of low real interest rates, fueling asset price bubbles and the proliferation of securitized credit products, which led to the build-up of financial risks in the financial system and weakened the effectiveness of the transmission of monetary policy (Borio and Zhu, 2012). The academic community widely recognizes that monetary expansion aimed at stimulating economic growth in the short term may lead to lower productivity and financial instability in the medium to long-term (Adrian and Shin, 2009). Low interest rates affect the size of bank credit and its allocation among different firms (Acharya and Naqvi, 2012). For example, in an accommodative monetary policy environment, undercapitalized banks may lend to firms with high default risk or low productivity to increase their profit margins (Asriyan et al. 2024) or relax bank financing constraints on less creditworthy firms and improve the conditions under which they can apply for loans (Gopinath et al. 2017). As a result, the topic of the risk-taking channel of monetary policy transmission has been widely discussed, which has focused on whether changes in the stance of monetary policy affect changes in the risk appetite of banking institutions from the micro- and macroperspective and to what extent bank risk appetite is transformed into realistic risk-taking behavior.

Borio and Zhu (2008) raised the issue of risk-taking channels of monetary policy transmission as early as 2008. In fact, the practical effects of global monetary policy after the 2008 financial crisis have shown that the prolonged loose monetary policy environment has changed the risk behavior of banks, which in turn affects the transmission channels of bank risk-taking. The bank risk-taking channel of monetary policy transmission is essentially a period in which loose monetary policy has an impact on bank risk perception or tolerance. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, developed countries such as the U.S. and the EU generally implemented “quantitative easing” monetary policy once again, attempting to stimulate economic recovery and growth, but this was accompanied by an economic downturn and rising inflation. To curb soaring inflation since 2022, the Federal Reserve and other major central banks have frequently raised interest rates sharply and have continued to release the expectation of interest rate hikes, exacerbating global economic fluctuations and making world economy recovery more difficult. Arbatli-Saxegaard et al. (2024) provide new evidence on financial and real spillovers from changes in US interest rates on emerging markets and advanced economies, confirming that US monetary policy shocks have sizable spillover effects on financial conditions and economic activity, with larger effects on emerging market economies: a 100-basis point unanticipated monetary policy shock is estimated to increase long-term domestic bond yields in other countries by ~25–35 basis points, with a higher pass-through for emerging market economies and during the period after the global financial crisis. Considering the effectiveness of monetary policy practices in Europe and the U.S., the “Quantitative Easing” monetary policy has increased the risk appetite of financial institutions, strengthened the willingness of commercial banks to bear risks to a certain extent and led to the precipitation and aggregation of risks in the financial system. The central bank’s stance and monetary policy adjustments significantly impact the limited rationality of commercial banks; i.e., commercial banks adjust their own willingness to take risks according to the current and expected monetary policy, which in turn affects their credit decisions. Hence, the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission and its impact on the stability of financial markets are largely determined by the risk-taking channels of commercial banks.

However, unlike the risks caused by the diversification of banks in the U.S. and the EU under the “quantitative easing” monetary policy environment, the Chinese banking industry is quite different. Owing to the separate operation and supervision of the financial system (Huang, 2021), financial innovation in China’s banking sector has been slow, leading to the aggregation of risks in the banking system. In addition, the slow process of interest rate marketization, coupled with strict financial regulation and mutual imitation of financial products and services, has led to an increased degree of homogenization of bank operations and increased risks (Song and Xiong, 2018; Yin and Li, 2021). In terms of policies, monetary policy uncertainty (Ge et al. 2023) and green credit policy (Feng et al. 2024) both lead to higher levels of bank risk-taking in China.

Moreover, Chinese commercial banks are subject to serious government intervention, and credit funds are concentrated in enterprises or industries that are implicitly guaranteed by the government (Qian et al. 2015; Zhu et al. 2020), which not only distorts credit fund allocation but also further intensifies bank homogeneity and increases bank risk-taking. The current environment of the Chinese banking industry is similar to that of the U.S. before the 1970s, and both are in a state of homogeneous operation under a limited business development model, which is essentially low-level competition that lacks core competitiveness and may increase banks’ risk-taking and exacerbate financial system instability. Ren et al. (2023) find that homogeneity increases bank risk-taking, and this result is heterogeneous among different bank characteristics. The World Bank data show that China’s non-performing loan ratio in the banking industry in 2021 was 1.73%, which is 2.1 times that of the United States (0.81%) and 1.8 times that of Germany (0.97%). This is only the book non-performing loan ratio, and the actual non-performing loan ratio may be even higher. Zhao and Li (2023), on the basis of the microdata of 377 commercial banks in China from 2007–2021, used a bilateral stochastic frontier model analysis method and measured the superposition of the bank’s risk control effect and profit-seeking effect, which ultimately led to the bank’s actual risk-taking being 24.6% higher than the frontier risk-taking; that is, Chinese commercial banks’ risk-taking may be underestimated.

Through there is significant empirical literature supporting the fact that loose monetary policy increases bank risk-taking (De Nicolò et al. 2010; Altunbas et al. 2014; Dell’Ariccia et al. 2014; Dell’Ariccia et al. 2017; Bonfim and Soares, 2018), the literature is silent with respect to the real effects of operating characteristics of commercial banks or business cycle fluctuations on commercial banks’ risk-taking. Most literature simply assumes that the increase in banks’ risk during periods of loose monetary policy contributes to financial instability, economic distress, and other negative macroeconomic outcomes (Bonfim and Soares, 2018). However, since there are other channels through which monetary policy affects banks’ stability, the increase in bank risk-taking does not necessarily imply “excessive” risk-taking that may lead to financial instability or have any real economic implications. This paper intends to bridge this gap in the literature by providing evidence for the connection between commercial banks’ risk-taking and real economic activity. Specifically, this paper focuses on identifying the commercial banks’ risk-taking channel of Chinese monetary policy and the impact of central bank monetary policy on commercial banks’ risk-taking behavior, and how this behavior varies with the operating characteristics of commercial banks and the macroeconomic environment, by using commercial banks’ micro-financial data.

Our paper is most related to the study of Adrian and Shin (2010;2014), who investigated the riskiness of banks’ credit assets by using data from the Federal Reserve’s Flow of Funds account. They found that banks’ leverage ratio is procyclical and that banks generally expand their balance sheet size by taking on more short-term debt during periods of low policy rate, implying the risk-taking channel of the commercial banks through expanding their balance sheet size. However, Adrian and Shin (2010;2014) didn’t analyze how commercial banks’ risk-taking behavior is affected by the microcharacteristics of the commercial banks and the macroeconomic environment. Therefore, using commercial banks’ micro-financial data, this paper intends to investigate the significant role of micro-financial characteristics and macroeconomic conditions in commercial banks’ risk-taking to provide specific evidence of the connection between the risk-taking channel, operating characteristics, and business cycle fluctuations.

To sum up, the possible marginal contributions of this paper are as follows: First, in the selection of research objectives, both the impact of macroeconomic fluctuations and the microcharacteristics of banks are taken into account, and banking institutions such as state-controlled large banks, joint-stock banks, urban commercial banks, rural commercial banks, foreign-funded banks, and agricultural credit (joint) establishments are selected, including all types of commercial banking institutions in China; in particular, the number of samples of small and medium–sized banking institutions exceeds the number of state-owned large banks and joint-stock banks, which provides an opportunity to prevent the risk of small and medium–sized banks, providing the basis for empirical testing. Second, in identifying bank risk-taking channels, this paper considers the impact of both quantitative monetary instruments (quota cuts) and price-based monetary instruments (interest rate cuts) on bank risk appetite and coordinates the impact of changes in the central bank’s monetary policy stance on bank risk-taking within the framework of macroeconomic fluctuations and on banks’ microcharacteristics. In view of this, this paper attempts to examine the mechanism and effect of monetary policy shocks on banks’ risk-taking behavior on the basis of the introduction of variables reflecting macroeconomic fluctuations and banks’ microcharacteristics to provide empirical references for the effective and precise implementation of structural monetary policy by central banks.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: “Literature review” provides a review and analysis of the theoretical mechanism of banks’ risk-taking; “Methodology” presents the methodology, data, and identification strategy; “Empirical findings” reports the results of the empirical analysis of banks’ risk-taking; “Mchanism tests” reports the results of the empirical analysis of the impact of banks’ microcharacteristics and macroeconomic fluctuation mechanism on banks’ risk-taking; “Robustness tests” provides a series of robustness tests; and “Conclusions and policy implications” presents conclusions and policy implications.

Literature review

This study is closely related to three categories of literature as follows:

The existence of bank risk-taking channels

Adrian and Shin (2009) argue that the role of banks as financial intermediaries in monetary policy transmission is passive due to the existence of financial frictions and price stickiness. On the other hand, the financial crisis has shown that banks are not risk-neutral or risk-tolerant financial intermediaries with constant risk tolerance in monetary policy transmission; rather, banks are more sensitive to risk, thus affecting monetary policy transmission (Maddaloni and Peydró, 2013). Scholars have studied the reasons for the non-risk-neutrality of banks from the risk of information asymmetry arising from the “principal-agent problem” and believe that the adverse selection caused by information asymmetry in advance and the moral hazard caused by information asymmetry in hindsight induce banks to invest in risky business (DellʼAriccia et al. 2010); in the case of the coexistence of information asymmetry and liquidity risk, the change in the stance of the monetary policy affects the bank’s willingness to take advantage of market shocks and increases the vulnerability of the bank (Diamond and Rajan, 2012).

Identification of bank risk-taking channels

Monetary policy transmission occurs through the credit channel, interest rate channel, and balance sheet channel; the key is eliminating the interference of other channels to identify the “pure” bank risk-taking channel (Soares and Bonfim, 2018). Domestic scholars prefer to use the non-performing loan ratio, Z value, risk-weighted assets to total assets ratio, loan loss provision to total loans, and other indicators to indirectly measure the size of the bank’s risk-taking (Li, 2014). The logic of the mechanism is that the essence of the bank is to operate the risk. The premise of risk-taking is to have a matching risk premium; that is, the higher the level of risk-taking by the bank is, the greater the risk premium it asks for, and thus, the greater the risk it may face, the greater the risk may also be. Altunbas et al. (2014) identify the risk-taking channel independently by controlling for the interest rate channel, the credit channel, and the balance sheet channel. In terms of bank risk measurement, Ramayandi et al. (2014) use different measures of bank risk-taking, such as non-performing loan ratio, Z score to validate the existence of bank risk-taking in the Asian region.

The mechanism of bank risk-taking

The literature suggests that there is a negative correlation between monetary policy and commercial bank risk-taking; i.e., a long-term loose monetary policy environment encourages banks’ risk-taking behavior. The mechanism of bank risk-taking is reflected in four main aspects.

First, in terms of the valuation and cash flow effect, the mechanism of banks’ risk-taking is as follows: when the central bank implements a long-term loose monetary policy characterized by low interest rates, the value of assets and collaterals will increase, the bank’s revenues and profits will also increase. Therefore, the bank’s risk sensitivity and risk tolerance will tend to decrease in a situation of good business performance, which will cause the bank to relax its risk budget, thus creating positive incentives for risk taking. Additionally, the popularity of measures such as Value at Risk (VaR) accelerates the formation of this effect (Zhang and He, 2012). The recent financial and sovereign debt crises emphasized the interdependence between bank and sovereign default risk and showed that major shocks may lead to a self-reinforcing negative spiral. For example, Lovreta and López Pascual (2020) show that endogenously identified turning points coincide with important public events that affect investors’ perceptions of the government’s capacity and willingness to repay debt and support distressed banks and finally provide evidence that structural dependence in the system extends to the interaction between bank and sovereign default risk volatility.

The second is the benefit-chasing effect, which is driven mainly by the spread between the market interest rate and the target rate of return. Usually, the liability side of a bank is marked by a long-term fixed nominal interest rate, while the target rate of return to achieve the profitability requirement is often sticky. In an accommodative monetary policy environment, bank lending rates fall, leading to a subsequent reduction in the target rate of return. According to Jiang and Chen (2011), to achieve the expected profit target, the bank will seek high-yield and high-risk assets, which ultimately leads to an increase in the bank’s risk tolerance.

Third, the communication feedback effect refers to the fact that the central bank’s monetary policy commitment and transparency affect the bank’s ability to supply credit, which affects output, employment, and price. In particular, when the central bank improves the transparency of monetary policy and fulfills commitments by increasing market communication, this weakens the uncertainty of important variables such as interest rates and inflation expectations, which is conducive to stabilizing the operating expectations of commercial banks, thereby reducing their risk premium and enhancing their asset pricing capacity and liability levels (Dai and Hai, 2014).

The fourth is the risk transfer effect, which was first proposed by Dell’Ariccia et al. (2010). Assuming the existence of information asymmetry and limited liability, Dell’Ariccia et al. (2010) argue that the downward movement of the policy rate leads to a decrease in the yield on the asset side of the bank, which increases the bank’s demand for risky assets; at the same time, the downwards movement of the policy rate leads to a decrease in the rate of interest paid on the liability side of the bank, which in turn reduces the cost of bank debt, preventing banks from adopting risky means to achieve the target return and realize risk transfer.

In summary, the extant literature has focused mainly on the channel identification and transmission of bank risk-taking mechanisms in advanced countries such as the U.S., whereas research on how macroeconomic fluctuations and microcharacteristics affect bank risk-taking is relatively insufficient. Especially, there is little literature exploring the determinants of risk-taking behavior among Chinese commercial banks. On the one hand, owing to the procyclicality of commercial banks’ operating behaviors, macroeconomic fluctuations amplify the behavioral characteristics of commercial banks; on the other hand, there are obvious differences in the risk identification and tolerance of commercial banks with different operating characteristics when they face the same monetary policy shocks, which results in obvious heterogeneity in the monetary policy transmission effect in commercial banking institutions, weakening the overall effect of monetary policy. Hence, the study of Chinese commercial banks’ risk-taking will likely provide new stylized facts and have great implications for global financial stability.

Methodology

Theoretical studies have shown that bank risk-taking includes both the willingness to take risks and the degree of bank risk-taking. To objectively reflect the impact of changes in monetary policy on bank risk-taking, the empirical research in this paper focuses on the degree of bank risk-taking and empirically examines whether there is a risk-taking channel for the transmission of monetary policy. If so, what characteristics will be exhibited by banking institutions with significant differences in micro characteristics such as asset size, capital position, liquidity level, profitability position, and market coverage? In addition, how does bank risk-taking behavior respond to changes in monetary policy when variables such as bank microcharacteristics and macroeconomic fluctuations are controlled for?

Model specification

Referring to Altunbas et al. (2014), Delis and Kouretas (2011), and Dong and Sun (2020), this paper constructs the following benchmark model to identify the presence of risk-taking channels for China’s monetary policy transmission.

In Eq. (1), Riski,t represents the risk premium of bank i’s loan issuance at time t; monetary policy shocks, including the deposit reserve ratio (DRR) and the growth rate of the broad money supply (M2); banki,t represents the microcharacteristics of the bank in time, including the size of assets (Size_ln), the capital adequacy ratio (CapR), the liquidity ratio (DTLR), the return on equity (ROE), and the number of bank branches (AgeNo); and Macrot represents the variables portraying macroeconomic fluctuations, including the real economic growth rate (GDPG) and inflation (CPI). number of outlets (AgeNo); and variables that portray macroeconomic fluctuations, including the real economic growth rate (GDPG) and inflation rate (CPI). εi,t denotes the random error term.

Furthermore, to analyze the impact of banks’ microcharacteristic variables on the risk-taking channel of monetary policy transmission, monetary policy shock proxies and proxies for banks’ microcharacteristic variables are added on the basis of benchmark Model (1), and the sign and size of the interaction term coefficients are used to determine how macroeconomic fluctuations affect the relationship between monetary policy and bank risk-taking. Following Fang et al. (2019), who studied the impact of bank size, cost efficiency, profit efficiency, and the inflation rate on bank risk-taking levels, and revealed that when banks take on greater risk and face more fierce competition, banks with better operating characteristics have greater profitability and lower risk, we specify the regression Eq. (2) by incorporating the interaction term of the variable of monetary policy and operating characteristics of commercial banks (MPt ‧ banki,t):

The coefficients in Eq. (2) have the same meaning as those in Eq. (1), and the relationship between monetary policy and bank risk-taking is represented mainly by the coefficient of the interaction term δj. Since ∂Risk/∂MP = \({\alpha }_{1}+{\delta }_{j}\cdot bank\), if δi is significantly negative and opposite to α1, this means that the operational characteristics of banks weaken the risk-taking effect of monetary policy. The converse is also true. Therefore, through Eq. (2), it can be judged whether the effect of monetary policy on bank risk-taking differs due to the heterogeneity of bank microcharacteristics, which provides a theoretical reference for monetary authorities to effectively implement structural monetary policy.

In addition, macroeconomic fluctuations affect monetary policy risk-taking channels while affecting banks’ microcharacteristics. Therefore, to analyze the impact of macroeconomic fluctuations on the risk-taking channel of monetary policy, on the basis of the benchmark regression model (1), we add the interaction term between monetary policy shocks and macroeconomic fluctuation variables and analyze how macroeconomic fluctuations affect the relationship between monetary policy and banks’ risk-taking through the sign and size of the coefficients of the interaction term to obtain Eq. (3).

The meanings of the coefficients in Eq. (3) are the same as those in Eqs. (1) and (2), and the relationship between the characteristics of macroeconomic fluctuations in monetary policy and bank risk-taking is reflected mainly by the signs of the coefficients of the interaction terms. In Eq. (3), because \(\partial Risk/\partial MP={\alpha }_{1}+{\gamma }_{j}\cdot Macr{o}_{t}\), if γj is significantly negative and opposite to α1, macroeconomic fluctuations weaken the monetary policy risk-taking effect. The effect of monetary policy on bank risk-taking can be used to determine whether the effect of monetary policy on bank risk-taking shows significant variability due to macroeconomic fluctuations.

Variables

First, we select bank risk-taking (Riski,t) proxy variables. When studying the risk channel of monetary policy transmission, scholars tend to use indicators such as the non-performing loan ratio (Delis et al. 2017), the proportion of risk-weighted assets to total assets (Deng and Zhang, 2018), and the Z value (Duan et al. 2018) as proxy variables for bank risk-taking. However, two problems may arise from the use of these proxy variables: on the one hand, these variables are calculated on the basis of the bank’s balance sheet, which is the result of the bank’s risk accumulation in the long-term operating process, an ex-post indicator, and cannot reflect whether it is incremental or stock risk; on the other hand, these risk proxy indicators are derived on the basis of the data at the bank-level, and it is not possible to identify whether bank risk-taking is caused by the bank’s own operation; on the other hand, these risk proxies are based on bank-level data, which cannot identify whether the bank’s risk-taking is caused by its own business behavior or by macroeconomic fluctuations and thus cannot solve the problem of identifying risk-taking channels.

To overcome the problems that may arise from the above proxy variables for bank risk-taking, this paper adopts the spread between the bank’s rate of return on interest-earning assets (ROA) and the one-year benchmark lending rate as a proxy variable for bank risk-takingFootnote 1. On the one hand, the spread between the rate of ROA and the benchmark lending rate reflects the risk premium of the bank’s loan issuance, and the greater the spread is, the greater the bank’s risk-taking level and willingness to take risks; on the other hand, there are significant differences in the risk-taking ability and risk appetite of different types of banks, especially in the face of monetary policy shocks, and the change in the spread can accurately identify the distribution of financial risk in different types of banking institutions to provide a better solution for the maintenance of financial risk. On the other hand, there are significant differences in the risk tolerance and risk appetite of different types of banks, especially in the face of monetary policy shocks. More importantly, after controlling for the impact of banks’ microcharacteristics and macroeconomic fluctuations on spreads, the impact of changes in the stance of monetary policy on the risk-taking of different types of banks can be effectively identified, providing empirical evidence for the precise identification of the risk-taking channel of monetary policy transmission.

The second variable is the core explanatory variable. The deposit reserve ratio (DRR) and the growth rate of the broad money supply (M2) are selected as proxies for the monetary policy shock (MPt). The weighted deposit reserve ratio (DRR_W) reflects the credit expansion capacity of the entire banking system; the higher the weighted DRR is, the tighter the credit constraint of the banking system. The higher the growth rate of the broad money supply (M2) is, the more abundant the liquidity of the whole society, the lower the level of risk-free interest rate of the society in theory, and the lower the level of risk-taking of banks.

The third variable is the key control variable. According to the practices of scholars, the real GDPG and CPI are selected as proxy variables for macroeconomic fluctuations, with the former affecting banks’ profitability expectations and the latter reflecting the level of real interest rates, which affects banks’ real risk premiums. The control variables reflecting the microcharacteristics of banks are Size_ln, CapR, DTLR, ROE, and AgeNo. These microindicators reflect the safety, liquidity, profitability, and market coverage of banks’ operations and reflect changes in the level of risk-taking of banks with heterogeneous characteristics under different monetary policy stances.

Fourth, we address the interaction term indicator. The interaction term indicates the degree to which bank risk-taking is sensitive to monetary policy shocks when variables such as macroeconomic fluctuations and bank microcharacteristics change. At the macroeconomic level, monetary policy is countercyclical and crosscyclical in nature; i.e., it implements tight monetary policy (e.g., raising the reserve requirement ratio and base rate) when the economy is overheating and expansionary monetary policy (e.g., lowering the reserve requirement ratio and base rate) when the economy is weakening, and it affects the level of banks’ risk-taking by eliminating economic fluctuations. At the micro level, different types of banks show significant differences in terms of asset size, capital adequacy, liquidity, profitability, and market coverage, leading to markedly different risk preferences and business strategies and, thus, sensitivity to monetary policy shocks. Therefore, identifying and testing the bank risk-taking channel of monetary policy transmission requires focusing on the magnitude and sign of the interaction term coefficients. Empirical studies have shown that there is a time lag in monetary policy transmission due to the presence of financial frictions, leading to the possibility of a lagged effect of monetary policy shocks (MPt) on bank risk-taking behavior. Drawing upon Huang and Xiong (2013), this long-run cumulative effect is examined by constructing long-run coefficients of elasticity (long-run coefficients) on the basis of Wald’s significance test for this coefficient.

Methodology and sample selection

Drawing on Dai and Li (2016), the GMM estimation method is chosen in this paper because it increases the available instrumental variables, overcomes the limitation that differential GMM is unable to estimate the coefficients of the variables that do not change over time, and improves the precision of parameter estimation; at the same time, to overcome the possible problem of endogeneity, the instrumental variables are appropriately introduced to objectively and accurately describe monetary policy shocks under the dynamic change characteristics of bank risk-taking.

The sample of the study included Chinese commercial banks, covering the financial data of state-controlled large commercial banks, joint-stock commercial banks, urban commercial banks, rural commercial banks, foreign banks, rural credit unions and cooperatives, and new rural financial institutions; these data were obtained from the CSMAR database, Wind database, and annual reports of commercial banks. After the removal of missing sample values, 2788 bank sample observations are obtained. The time period is 2007–2021, during which China’s monetary policy experienced a complete cycle of easing and contracting. The descriptive statistics of the variables are reported in Table 1.

Empirical findings

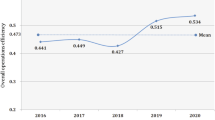

Baseline results

Table 2 presents the OLS, GMM, and FGLS estimates of the benchmark regression Eq. (1). All the monetary policy shocks are significant at the 1 percent level after controlling for the effects of bank microcharacteristics and macroeconomic volatility variables on bank loan risk premiums. Specifically, a 1 percentage point increase in the reserve requirement ratio increases bank risk-taking by 0.1544 percentage points, suggesting that tight monetary policy reduces banks’ loanable funds and that banks need to increase the risk premium on loans to achieve their profitability goals; conversely, a 1 percentage point increase in the growth rate of the broad money supply decreases bank risk-taking by 0.1458 percentage points, suggesting that accommodative monetary policy decreases the market risk-free rate and the risk premium of bank loans.

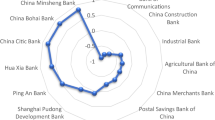

From a micro perspective, commercial banks with different microcharacteristics exhibit significant asymmetry in their risk-taking levels in the face of monetary policy shocks. The larger the asset size is, the greater the degree of risk-taking of banks, contrary to the findings of Delis et al. (2017) and Dong and Sun (2020). This is because the Chinese economy experienced a downwards cycle from 2007−2021, during which the risk of commercial bank lending increased, and the larger the asset size was, the greater the level of risk that banks needed to take in pursuit of the set profitability targets. The higher the capital adequacy ratio is, the greater the degree of risk-taking is because capital, as an important risk mitigation tool, tends to maximize its loss-absorbing role, driven by the profitability motive. A higher loan-to-deposit ratio (lower liquidity) indicates a bank’s ability to utilize capital and profitability; accordingly, its level of risk-taking is lower. The higher the NPA is, the stronger the incentive for a bank to maintain and pursue a high-yield target in the next period and the greater its risk-taking. The greater the number of bank branches is, i.e., the greater the market coverage is, the greater the risk tolerance and the lower the bank’s risk-taking. The higher the economic growth rate is, the better the environment for bank credit allocation, the lower the loan default rate and the lower the level of risk-taking. The higher the inflation rate is, the lower the level of real interest rates, the lower the bank risk premium and the lower the bank’s risk-taking.

Mechanism test

Bank microcharacteristics and bank risk-taking

The GMM estimation results when the reserve requirement ratio is adjusted are given in Eq. (1) to (5) in Table 3. The empirical results show that when the central bank adjusts the deposit-to-reserve ratio, this type of monetary policy has a significant effect on the level of risk-taking of commercial banks, thus verifying that monetary policy transmission has a bank risk-taking effect. The coefficients of the interaction terms between bank microcharacteristics and monetary policy (deposit reserve ratio) show that the effects of bank microcharacteristics on the relationship between monetary policy and bank risk-taking are significant, but these effects are significantly asymmetric among banking institutions with different microcharacteristics. Specifically, when the central bank raises the reserve requirement ratio (implements a tight monetary policy), banks with larger assets, higher capital adequacy ratios, and higher returns on net assets have greater risk-taking; banks with lower liquidity and greater market coverage have lower risk-taking.

The GMM estimation results when regulating the broad money supply are given in Eq. (1) to (5) in Table 4. The empirical results show that this quantitative monetary policy affects bank risk-taking when the central bank regulates the money supply to test the existence of the risk channel of monetary policy transmission. From the coefficients of the interaction terms between bank microcharacteristics and monetary policy (broad money supply growth rate M2 increase), it can be conluded that bank microcharacteristics have a significant effect on the relationship between monetary policy and bank risk-taking, and this effect is characterized by significant asymmetry due to differences in bank microcharacteristics. When the central bank increases base money such that the growth rate of the broad money supply (M2) increases, i.e., through the implementation of tight monetary policy, the larger the asset size is, the greater the capital adequacy ratio is, the greater the return on net assets is, and the greater the risk-taking of banks is. Additionally, the lower the liquidity is, the greater the market coverage of banks is, and the lower the risk-taking of banks is.

Macroeconomic fluctuations and banks’ risk-taking

Table 5 shows the responses of commercial banks with different microcharacteristics to accommodative or tight monetary policies under macroeconomic fluctuations such as economic growth and inflation, respectively. Table 5, Eq. (1) shows that the central bank tends to reduce the reserve requirement ratio during an economic downturn, which causes the bank’s loanable funds to increase, leading to a decrease in the market risk-free interest rate and a decrease in the risk-taking of commercial banks. Table 5 Eq. (2) shows that when inflation declines, the central bank tends to reduce the deposit reserve ratio, which increases the funds available for commercial banks to lend, causing the market risk-free interest rate to fall, and commercial banks’ risk-taking tends to decline. Table 5, Eq. (3) shows that when the economy is in a downwards cycle, the central bank tends to increase its money supply, resulting in an increase in the growth rate of the broad money supply (M2), which decreases the market risk-free interest rate, thus decreasing the risk-taking of commercial banks. Table 5, equation (4) shows that when inflation tends to decrease, the central bank tends to implement an accommodative monetary policy, increasing the broad money supply to enhance market liquidity, which decreases the market risk-free rate; all the other factors are held constant. Similarly, the risk premium of commercial banks subsequently decreases, and the level of risk-taking decreases.

Robustness tests

Robustness test method

This paper attempts to test the robustness of the empirical results of the previous paper from two aspects: method selection and replacement of proxy variables. In terms of method selection, since the central bank’s monetary policy stance and bank risk taking are both affected by macroeconomic fluctuations—and thus, monetary policy shocks, as the core explanatory variable in this paper—may lead to endogeneity problems in the model. Generalized moment estimation (GMM) can eliminate the endogeneity problems of the variables, and GMM estimation is more effective than OLS estimation is; therefore, the GMM estimation method is used. In terms of variable selection, the spread between the bank lending rate and the one-year deposit base rate is used as a proxy variable for bank risk-taking (Risk2), reflecting the movement of the bank risk premium.

Robustness test results

Tables 6–8 present the results of the robustness test. The coefficients of the monetary policy shock, the interaction term of the monetary policy shock with the microcharacteristics of the bank, and the interaction term of the monetary policy shock with the macroeconomic fluctuations are overwhelmingly significant at the 1% level. The signs of the coefficients are consistent with those in the previous Tables 2–5, and there is no obvious difference in the size of the variable regression coefficients or the level of significance, thus supporting the basic conclusions of this paper.

Conclusions and policy implications

Conclusions

The risk-taking of Chinese commercial banks is affected not only by the impact of monetary policy but also by the microcharacteristics of commercial banks themselves and the macroeconomic environment. Moreover, the interactions among the micro-operating characteristics of commercial banks, macroeconomic factors, and monetary policy may strengthen the risk-taking behavior of commercial banks. However, the literature does not fully understand these interactions. Academics usually focus on a specific influencing factor when analyzing this issue, and a systematic assessment is lacking. However, against the backdrop of rising risk in China’s real estate and local debt in recent years, the risk-taking level of Chinese commercial banks with government credit endorsement has been underestimated (Zhao and Li, 2023), whereas small and medium-sized banking institutions with weak microoperational capabilities and greater influence of macroeconomic factors have incurred greater risk, which has been amplified to some extent by the central bank’s loose monetary policy. In this paper, we comprehensively assess the risk-taking level of commercial banks by looking for interactions among banks’ micro operational characteristics, the macroeconomic environment, and monetary policy within a formal econometric framework.

From a micro perspective, the interaction between commercial banks’ microoperational characteristics and monetary policy makes the channel through which monetary policy transmits bank risk-taking asymmetric. That is, commercial banks with larger asset sizes, higher capital adequacy ratios, and higher returns on net assets have higher risk-taking levels; commercial banks with better liquidity and higher network coverage have lower risk-taking levels. For example, frequent rotation of local officials can increase the risk-taking level of commercial banks through improper allocation of credit resources and increased competition, which may have a particularly damaging effect on banking institutions with lower operating levels (Zhang et al. 2024). From a macroperspective, the interaction between the macroeconomic environment and monetary policy makes the channel through which monetary policy is transmitted to bank risk-taking symmetrical; that is, the higher the economic growth rate and inflation level are, the lower the overall risk-taking level of commercial banks.

Limitations and outlook of this paper. Unforeseen events such as the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 coronavirus pandemic have had a significant impact on the risk-taking level of commercial banks. However, the Chinese government has mitigated the risks of individual enterprises and systemic market risks through financial policies to help enterprises, which has led to an underestimation of the risk-taking level of Chinese commercial banks (Zhao and Li, 2023). Owing to the unavailability of data, this paper does not use the event comparison method to analyze the impact of China’s monetary policy on the risk-taking of commercial banks. On the other hand, since almost all Chinese commercial banks have a government credit endorsement, the risk-taking level of commercial banks has actually been partially transferred to the government’s sovereign credit, which has affected the transmission effect of monetary policy. In the future, this paper will draw on the research ideas of Lovreta and López Pascual (2020) to focus on the interaction between commercial banks and sovereign debt risk and analyze the impact of unexpected events such as the subprime mortgage crisis and the new coronavirus epidemic to more comprehensively and truly reflect the risk behavior of Chinese commercial banks. Finally, as China’s pace of financial reform and development accelerated, the spillover effect of European and American central bank monetary policies on China’s economy and finances significantly increased. Future research may fully consider the impact of the European Central Bank’s monetary policy cycle.

Policy implications

This paper has the following policy implications: since bank risk-taking serves as an important channel of the monetary policy transmission mechanism, the People’s Bank of China (PBC) needs to consider the significant role of bank risk-taking when formulating and implementing monetary policy. First, it is necessary to strengthen the market communication of monetary policy and improve its transparency. In terms of the use of monetary policy tools, it is necessary to maintain the relative stability of intermediary variables such as the money supply, interest rate levels, and reserve requirement ratios and to guide market expectations in an orderly manner so that the level of bank risk-taking matches the outlook for money and credit and economic growth. Second, the supervision of commercial banks should be strengthened to improve their operation and management capabilities. Commercial banks in China should be guided to establish a belief of “risk neutrality”, adhere to the principle of prudent management, achieve an organic balance of profitability, liquidity and safety, better play the role of commercial banks in credit creation, and smooth banking channels for monetary policy transmission. Third, since maintaining macroeconomic stability is very helpful for weakening the effects of bank risk-taking on financial stability, the market-oriented and rule-of-law business environment should be continuously improved, and the level of market competition in the banking sector should be enhanced to strengthen the risk-resistant capabilities of commercial banks.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are subject to third-party restrictions. The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Note: As a result of the loan interest rate market reform, the 1-year Loan Rate Market Offer (LPR) is used in lieu of the base lending rate in 2019 and thereafter.

References

Acharya V, Naqvi H (2012) The seeds of a crisis: a theory of bank liquidity and risk taking over the business cycle. J Financ Econ 106(2):349–366

Adrian T, Shin HS (2009) The shadow banking system: implications for financial regulation. Banq Financ Stab Rev 13:1–10

Adrian T, Shin HS (2010) Liquidity and leverage. J Financ intermed 19(3):418–437

Adrian T, Shin HS (2014) Procyclical leverage and value-at-risk. Rev Financ Stud 27(2):373–403

Altunbas Y, Gambacorta L, Marques-Ibanez D (2014) Does monetary policy affect bank risk. Int J Cent Bank 10(1):95–135

Arbatli-Saxegaard EC, Furceri D, Dominguez PG, Ostry JD, Peiris SJ (2024) Spillovers from US monetary policy: role of policy drivers and cyclical conditions. J Int Money Financ 143:103053

Asriyan V, Laeven L, Martin A, Van der Ghote A, Vanasco V (2024) Falling interest rates and credit reallocation: lessons from general equilibrium. Rev Econ Stud rdae065

Bonfim D, Soares C (2018) The risk-taking channel of monetary policy: exploring all avenues. J Money Credit Bank 50(7):1507–1541

Borio C, Zhu H (2008) Capital regulation, risk-taking and monetary policy: a missing link in the transmission mechanism? BIS Working Papers, No. 268

Borio C, Zhu H (2012) Capital regulation, risk-taking and monetary policy: a missing link in the transmission mechanism. J Financ Stab 8(4):236–251

Dai JX, Hai MT (2014) A Survey on the research of risk-taking channel in monetary policy transmission. Wuhan Univ J 67(04):18–23

Dai JX, Li LX (2016) Empirical study of risk-taking channels of monetary policy in China: A case study of commercial banks. J Cent South Univ (Social Sciences) 22(2):84–91

De Nicolò G, Dell’Ariccia G, Laeven L, Valencia F (2010) Monetary policy and bank risk taking. Available at SSRN 1654582

Delis MD, Hasan I, Mylonidis N (2017) The risk-taking channel of monetary policy in the US: evidence from corporate loan data. J Money Credit Bank 49(1):187–213

Delis MD, Kouretas GP (2011) Interest rates and bank risk-taking. J Bank Financ 35(4):840–855

Dell’Ariccia G, Laeven L, Marquez R (2014) Real interest rates, leverage, and bank risk-taking. J Econ Theory 149:65–99

Dell’Ariccia G, Laeven L, Suarez GA (2017) Bank leverage and monetary policy’s risk-taking channel: evidence from the United States. J Financ 72(2):613–654

Dell’Ariccia G, Marquez MR, Laeven ML (2010) Monetary policy, leverage, and bank risk-taking. International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. 2010/276

Deng XR, Zhang JM (2018) Monetary policy, bank risk taking and bank liquidity creation. J World Econ 41(4):28–52

Diamond DW, Rajan RG (2012) Illiquid banks, financial stability, and interest rate policy. J Political Econ 120(3):552–591

Dong HP, Sun Y (2020) A research on risk taking channel of monetary policy based on micro loan data: from the perspective of bank characteristics, borrowing enterprise characteristics and loan contract characteristics. Econ Surv 37(6):151–162

Duan JS, Yang F, Gao HM (2018) Deposit insurance, institution environment and commercial bank risk-taking: based on the evidence of the global sample. Nankai Econ Stud 3:136–156

Fang J, Lau CKM, Lu Z, Tan Y, Zhang H (2019) Bank performance in China: a perspective from bank efficiency, risk-taking and market competition. Pac-Basin Financ J 56:290–309

Feng YC, Pan YX, Sun C, Niu JY (2024) Assessing the effect of green credit on risk-taking of commercial banks in China: further analysis on the two-way Granger causality. J Clean Prod 437:140698. ISSN 0959–6526

Ge X, Liu Y, Zhuang J (2023) Monetary policy uncertainty, market structure and bank risk-taking: evidence from China. Financ Res Lett 52:103599

Gopinath G, Kalemli-Ozcan S, Karabarbounis L, Villegas-Sanchez C (2017) Capital allocation and productivity in South Europe. Q J Econ 132(4):1915–1967

Huang RH (2021) Financial regulatory structure in China: challenges and transitioning to twin peaks. In: Godwin A, Schmulow A, eds. The Cambridge Handbook of Twin Peaks Financial Regulation. Cambridge Law Handbooks. Cambridge University Press; 2021:253–269

Huang X, Xiong QY (2013) Bank capital buffers, credit behavior and macroeconomic fluctuations: empirical evidence from the chinese banking sector. Stud Int Financ 1:52–65

Jiang SX, Chen YC (2011) Monetary policy, bank capital and risk-taking. J Financ Res 04:1–16

Li HW (2014) Bank capital and monetary policy’s risk-taking channel: a theoretical model and empirical study of China’s banking industry. Financ Econ Res 29(03):34–43

Lovreta L, López Pascual J (2020) Structural breaks in the interaction between bank and sovereign default risk. SERIEs 11(4):531–559

Maddaloni A, Peydró JL(2013) Monetary policy, macroprudential policy and banking stability: evidence from the euro area. European Central Bank, WPS1560

Qian X, Zhang G, Liu H (2015) Officials on boards and the prudential behavior of banks: evidence from China’s city commercial banks. China Econ Rev 32:84–96

Ramayandi A, Rawat U, Tang HC (2014) Can low interest rates be harmful: an assessment of the bank risk-taking channel in Asia. Asian Development Bank, WPS136167

Ren MX, Zhao JM, Ke KL, Li YD (2023) Bank homogeneity and risk-taking: evidence from China. Q Rev Econ Financ 92:142–154

Song ZM, Xiong W (2018) Risks in China’s financial system. Annu Rev Financ Econ 10:261–286

Yin Z, Li Z (2021) Competition avoidance and the diffusion of bank financial innovation—an empirical test from the perspective of bank homogeneity. Manag World 37(11):71–89

Zhang S, Yuan R, Li Y, Chen L, Luo D (2024) Local official turnover and bank risk-taking: evidence from China. Emerg Mark Rev 101208

Zhang XL, He DX (2012) Monetary policy stance and bank risk-taking: an empirical study of banking industry in China (2000-2010). Econ Res J 47(5):31–44

Zhao XX, Li SJ (2023) Is risk-taking appropriate for Chinese commercial banks? Shanghai Financ 12:19–33

Zhu J, Yue H, Rao P (2020) Local governments’ fiscal pressure and bank credit resource allocation efficiency: evidence from Chinese city commercial Banks. J Financ Res 1:88–109

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Social Science Fund of Hubei Provincial Education Department (Grant No.22ZD025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chunjiao Yu: Conceptualization, methodology, language improvement, and revision; Wei Tang: The first draft of the manuscript, methodology, and formal analysis. Jiaqi Zhao: language improvement and overall proofs.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, C., Tang, W. & Zhao, J. Assessing China’s bank risk-taking: a study from the microeconomic and macroeconomic perspectives. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1619 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04144-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04144-5