Abstract

How do illegal markets operate in cyberspace? Drawing on interview data, this article examines the organizational structure of China’s illegal online gambling businesses and their use of extralegal governance institutions to marketize services, ensure fair play, enforce compliance, and reduce the risk of prosecution. The article also discusses the impact of China’s intensified efforts to repress illegal markets. It suggests that operators in the illegal online market now prefer to settle gambling debts using ex ante means, such as deposits, rather than ex post mechanisms, such as using interpersonal obligations or violence to enforce debt collection. This research contributes to the literature on extralegal governance, gambling, and illegal markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Participants in illegal online exchanges face many risks, from being cheated or deceived to being arrested by the police. Deception is rife because of the anonymity provided by the Internet, and there can be no formal contracts or protection from state institutions, such as courts (Hall and Antonopoulos, 2016; Lusthaus, 2012; Lusthaus and Varese, 2021). Indeed, far from receiving protection, illegal market actors face state suppression and police crackdowns (Varese et al. 2019; Wang and Antonopoulos, 2016). Yet despite these disadvantages, illegal online markets continue to flourish. Although researchers have started to investigate the development of certain types of illegal online markets, such as the stolen data market (Hutchings and Holt, 2015) and the online peer-to-peer lending market (Wang et al. 2021), there is still a lack of theoretical and empirical research into the extralegal governance institutions used by market participants to mitigate risk, build trust, and sustain illegal online transactions. Based on data from interviews about China’s illegal online gambling market, this article aims to enrich our understanding of the social order of the illegal online market and show how cooperation is secured in cyberspace without state regulation.

Gambling is strictly regulated in mainland China, and the only form of legal gambling is through state-sanctioned lotteries, the China Welfare Lottery and the China Sports Lottery. Nonetheless, due to its convenience, accessibility and better odds compared to legal gambling, illegal online gambling is increasingly popular in China, from lotteries to sports betting and mah-jong. Even though China’s online gambling sector emerged only recently, it reached sales of 403 billion RMB in 2022 (Thomala, 2023), only slightly below state-run lottery sales of 424.6 billion RMB in the same year (Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China, 2023). Drawing on first-hand empirical data and published materials, this article examines the ways in which market participants use institutional mechanisms to marketize their services, ensure fair play, facilitate the collection of gambling debts, and reduce the risk of police attention. It also finds that China’s recent anti-crime campaign, the ‘sweep away black’ campaign, prompted participants in the illegal online gambling market to increasingly use ex ante mechanisms, such as requiring deposits, rather than enforcing debt collection through ex post mechanisms, such as interpersonal obligations, threats, and violence.

This research contributes to the existing literature in two ways. First, it contributes to the study of the social order of illegal markets in cyberspace and enhances the understanding of extralegal governance mechanisms that mitigate risks and enforce agreements without state support. A growing body of literature has examined various categories of risk and uncertainty and the problem-solving strategies used to sustain private ordering, such as strategies crafted by prison gangs (Skarbek, 2014, 2020), mafias (Campana and Varese, 2013; Gambetta, 2011; Varese, 2011), pirates (Leeson, 2009), diamond merchants (Richman, 2017), and builders of informal housing (Lin and Lin, 2023). However, there is still a lack of empirical research into how extralegal governance institutions secure cooperation in a virtual social environment, where people’s strategic interactions are affected by a combination of online and offline factors. Important research has been done on the use of compromising information in the online peer-to-peer lending market (Wang et al. 2021) and the role of reputation and network mechanisms in the stolen data market and online drug deals (Décary-Hétu and Dupont, 2013; Hardy and Norgaard, 2016), but a comprehensive study of this phenomenon from an extralegal governance perspective is still needed.

Second, and more specifically, this research investigates the emergence and operation of China’s online gambling market. The existing literature investigates online gambling from several perspectives, such as problem and pathological gambling (Gainsbury, 2015; Kuss and Griffiths, 2012; Wong and So, 2014), online gambling-related crime, such as money laundering, cyber fraud, and cyberextortion (Banks, 2014; Brooks, 2012; McMullan and Rege, 2007), and the motivations, habits, and preferences of players (Kim et al. 2015; Wood and Griffiths, 2008; Wood et al. 2007). Although recent research has explored the involvement of crime groups in offline gambling (Albanese, 2018; Lo and Kwok, 2017; Wang and Antonopoulos, 2016), insufficient scholarly attention has been paid to cooperation and risk mitigation in the illegal online gambling market. This article seeks to bridge this gap by adopting the theoretical perspective of extralegal governance and using first-hand empirical data.

Theoretical discussion

Extralegal governance institutions refer to private or nonstate mechanisms, such as norms, rules, organizations, and behavioural equilibria, which are used to mitigate risks, promote cooperation, and deter opportunism (Dixit, 2004; Leeson, 2008). This section first examines the risks faced by participants in illegal markets and how these risks evolve when illegal transactions move online. It then discusses the governance institutions participants could use to mitigate these risks in both offline and online social settings.

Risk and uncertainty in illegal markets

Illegal markets emerge and flourish in the teeth of state prohibition. These markets supply in-demand goods or services that are unavailable in the legal marketplace (Schelling, 1971). State prohibition of production, supply and distribution of these goods and services generates enormous opportunities for criminal entrepreneurs (Dewey, 2019), but prohibition creates substantial risks for participants. These risks fall into two categories. First, participants in illegal markets face opportunistic behaviour, such as fraud, betrayal, and free-riding, which cannot be resolved by state institutions, such as the police and courts. Compared with participants in legal markets, illegal market participants are less inhibited about misconduct and are more likely to engage in opportunistic behaviour for a quick profit (Campana and Varese, 2013). Even though cooperation generates profits and satisfies individual needs, potential participants will hesitate if they see widespread distrust and opportunism in the illegal market. For instance, a buyer has less incentive to risk paying in advance when they are uncertain about whether the seller will deliver services or goods as promised; likewise, a lender is unwilling to lend money to a new borrower without sufficient collateral.

Second, illegal markets undermine the rule of law and state legitimacy, making them subject to police crackdown and government suppression. In authoritarian China, the government employs campaign-style law enforcement to deal with crime-related problems, including illegal markets (Trevaskes, 2007; Wang, 2020a). Harsh and unpredictable law enforcement poses the greatest threat to illegal market participants, especially suppliers and distributors of illegal commodities and services; they face a high risk of incarceration, and profits from illegal exchanges can be confiscated. State law, especially criminal law, specifies different types of criminal punishment and different severity levels for different roles: some participants are defined as producers or suppliers, some as street-level distributors, and others as customers (see Wang, 2020b). For instance, in China, operators or agents of online gambling websites are charged with operating illegal gambling businesses (kaishe duchang zui) and are subject to a maximum five-year custodial sentence according to Chinese Criminal Law. In extremely serious cases, offenders may face a maximum ten-year custodial sentence. In contrast, the vast majority of gamblers are not subject to criminal punishment and instead receive, at most, 15 days of administrative detention according to China’s Public Security Administration Punishments Law. This differential punishment divides market participants into distinct groups: high-risk actors, such as illegal gambling operators, and low-risk actors, such as gamblers. This division affects how market participants interact.

When illegal exchanges move online, both challenges and opportunities increase. On the one hand, network technology transcends geographical boundaries and enables participants to conduct transactions with a much wider group. On the other hand, the anonymity of the Internet boosts opportunistic behaviour, such as fraud and cheating. Interacting with strangers online is challenging; participants find it difficult ‘to assess trustworthiness or to retaliate should dealing go sour and agreements need to be enforced’ (Lusthaus, 2012, p. 71). Dishonest participants are still able to take advantage of internet anonymity to sell products and services by disguising their identity online, even after cheating their exchange partners (Lusthaus, 2018). To make transactions possible, illegal online entrepreneurs have to develop strategies to signal their trustworthiness or make credible commitments.

Even though anonymity and identity shielding enable illegal entrepreneurs to hide behind the screen, making it harder for police to investigate illegal exchanges, illegal online entrepreneurs still risk detection, for two reasons. First, network technology helps local law enforcement agents communicate with their counterparts overseas to follow online clues across jurisdictional boundaries. Second, the traditional way of mitigating risks of criminal prosecution—bribing police officers—does not work so well online; it is harder for criminals to suborn police officers in distant geographic areas, as they are unable to build trust through face-to-face contact.

It is worth noting that those who make transactions in cyberspace not only interact in a virtual world but may also collaborate offline (Lusthaus, 2018; Lusthaus and Varese, 2021), often using pre-existing social relationships. Specifically, criminal entrepreneurs often have to rely on their interpersonal networks to find potential clients or partners. Most advertising strategies and promotional approaches adopted by legitimate businesspeople are unavailable to criminal entrepreneurs, so sellers must advertise and promote their products or services among their acquaintances. Likewise, it is less feasible for criminal entrepreneurs to recruit employees in the formal labour market. Instead, illegal sellers rely on personal relationships to recruit trustworthy collaborators and employees (Leukfeldt et al. 2017a, 2017b).

Governance mechanisms in offline and online contexts

The operation of illegal online markets is sustained by a range of governance institutions. This part investigates extralegal governance institutions from offline and online perspectives, although the effectiveness and performance of these institutions can vary according to context.

Offline extralegal governance institutions

In the offline world, participants in illegal markets have developed a set of extralegal governance mechanisms to enforce agreements, overcome opportunism, and minimize the risk of criminal punishment. One of the most frequently used offline mechanisms is reputation, which relies on the transmission of interpersonal-based information. Before initiating transactions, participants evaluate the trustworthiness of potential partners by gathering information about their reputations, including credibility, competence, and past behaviour. In practice, information is transmitted through gossip in relational networks (Giardini and Wittek, 2019). Unsurprisingly, many participants decline to interact with a person who has a record of cheating or betrayal. Given that reputational information is transmitted through close social relationships, it is reasonable for a person to behave honestly and cooperatively if they value the earnings potential of future interactions (Dixit, 2004; Greif, 2006). The interpersonal-based reputational mechanism is more efficient when the network is tight and small; it becomes expensive and inefficient when the network size significantly increases or the network becomes more socially and culturally diverse (Ellickson, 1991).

When participants in illegal markets want to exchange with those outside their close social networks, they need to solve the problem of asymmetric information, which is caused by the lack of reliable information about each other’s trustworthiness (Leeson, 2008). In such circumstances, participants need to develop strategies to signal trustworthiness. By investing in a credible signal, participants can convince potential exchange partners that they are trustworthy in the sense that they are not playing a one-shot game and will behave cooperatively, honestly, and patiently instead of opportunistically (Gambetta, 2011; Gintis et al. 2001; Lin et al. 2024). Empirical evidence suggests that people, including criminals, have developed credible signals to enhance cooperation when interacting face-to-face. These signals range from investments, such as criminal rituals (Skarbek and Wang, 2015) and gift-giving (Posner, 1998), to implicit cues of intrinsic motivation or emotion, such as eye contact, a sincere smile (Cheng et al. 2020) and tattoos on the face or neck (Gambetta, 2009). Nonetheless, it is not always possible to ensure the credibility of such signals, because they can be simulated by opportunists who can reap the benefit from a one-shot game. Trustworthiness signals are clearly not a panacea, and other mechanisms are needed to secure cooperation.

Threats and violence are commonly used to enforce compliance in criminal markets such as offline gambling (Wang and Antonopoulos, 2016), drug dealing (Durán-Martínez, 2017), and kidnapping (Shortland, 2017). Organized violence, as a means to provide protection and achieve informal control, is often provided by professional third parties such as gangs or mafias (Gambetta, 1996; Varese, 2011). Due to their capacity to use violence, gangs are often invited to get involved in illegal markets to enforce contracts, deter fraud, and solve disputes (Andreas and Wallman, 2009). In many scenarios, the mere threat of violence is sufficient, especially when participants can credibly display their toughness or convince potential partners of the toughness of their confederates (Gambetta, 2009).

Nonetheless, the purchase of gang protection and the use of violence have several drawbacks. First, illegal entrepreneurs have to pay to obtain private protection or criminal enforcement, and rates can be high. Second, extensive use of violence attracts police attention. The risk of criminal punishment is particularly high in countries where the state tries to monopolize the use of coercive power within its territory (Barzel, 2002; Wang, 2020a; Weber, 2004). Low-risk actors, who face less severe punishment if arrested, can blackmail high-risk actors by threatening to report them to the police, putting high-risk actors in a precarious situation. In this context, an act of violence and the use of gang methods are compromising information that can be exploited by others (Campana and Varese, 2013, p. 266; Gambetta and Przepiorka, 2019). Finally, violence becomes less effective when illegal entrepreneurs shift transactions online because in-person enforcement becomes more expensive and less feasible (Wang et al. 2021).

In addition to market-based risks such as opportunistic behaviour, participants in illegal online markets face the threat of prosecution. To mitigate this risk, they often resort to bribing state agents (Wang, 2020a). Corrupt police officers can offer protection to illegal entrepreneurs in two main ways. They can choose not to investigate individuals with whom they have corrupt dealings, and, taking advantage of their privileged access to information, they can inform illegal entrepreneurs of imminent police operations in their jurisdiction. Nonetheless, purchasing protection from stage agents is not sufficient for securing the operation of illegal markets in cyberspace, and therefore other strategies are called for.

Extralegal governance institutions in the online world

As participants move their interactions online, they adopt governance mechanisms that are effective in offline markets to function online. The first of these is the system-based reputation mechanism. Unlike the interpersonal-based reputation mechanism, which relies on information provided by acquaintances, in the system-based reputation mechanism strangers rate and review distant partners, allowing external parties to assess the trustworthiness of potential partners. System-based reputation mechanisms are widely used in online markets. They include not only rating and feedback systems used on sharing economy platforms, for example, e-commerce sites such as eBay, Amazon, and Alibaba (Dellarocas, 2003; Standifird, 2001), but also comments made in the forums and websites of cybercriminal markets, relating for example to stolen data, drug dealing, and botnet services (Décary-Hétu and Dupont, 2013; Hardy and Norgaard, 2016; Holt et al. 2015). However, reputation information can be seen as public goods (Bolton and Ockenfels, 2009); participants might have a tendency to free-ride on evaluations provided by others and lack the incentive to contribute to the information pool (Lev-On, 2009).

Similar to the offline context, signalling trustworthiness is a useful way for participants in cyberspace to show potential exchange partners their reliability and competence. Online signals point either to the credibility and ability of individual participants, such as illegal entrepreneurs, or to online marketplaces, such as websites or platforms. Trustworthiness signals are as expensive for individual entrepreneurs to produce online as they are offline. For example, a digital vendor can demonstrate their desire to encourage repeat business by spending time in a forum. Trustworthiness signals also include subtle clues, such as posting personal photos (Ert et al. 2016) and using criminal nicknames that are well-known in illegal communities (Lusthaus, 2012).

Platforms or websites often establish high-profile brands, user-friendly interfaces, institutionalized rules, and formalized programmes to signal their trustworthiness and attract a large number of clients. For example, high-profile brands not only indicate that the platforms have a large number of loyal clients, but they also signify the investment of digital entrepreneurs in advertising, indicating their intention to engage in long-term business (Möhlmann and Geissinger, 2018; Riegelsberger et al. 2007). Likewise, a website that offers effective security technology and a strictly enforced privacy policy can increase the sense of safety for clients and thus their confidence in using the website (Riegelsberger et al. 2007). By contrast, it would not be surprising that clients hesitate to engage in transactions if the payment process of an online marketplace often fails or requires clients to send payment to the private account of a person they do not know.

Online platforms, such as forums, websites, and apps, serve two distinct roles. First, they can act as direct contracting parties, engaging in sales transactions with clients. Second, they can function as third-party enforcers, providing a marketplace for online transactions and associated enforcement services to both vendors and clients. As providers of goods and services, online platforms have to establish themselves as major suppliers of certain commodities by building their reputation and earning the trust of their customers. As third-party enforcers, trustworthy online platforms must address the issue of customer opportunism, where customers may attempt to exploit the platform for their own gain. As previously mentioned, violence is not a credible threat in an online setting, so alternative institutions must be developed. One common mechanism is the use of hostage-taking, which involves demanding a deposit or initial payment as an ex-ante mechanism to deter cheating by either party (Raub and Keren, 1993; Weesie and Raub, 1996). In addition, online platforms must establish clear rules to regulate online transactions, including rating and escrow systems, reporting and refund functions, and sanction mechanisms.

To lower the risk of detection and prosecution, illegal entrepreneurs in cyberspace use Internet infrastructure and network technology to conceal evidence of their activities. Several methods are commonly employed, such as frequently setting up new websites, using others’ accounts, employing web proxies located overseas, and avoiding the use of terms that are subject to police monitoring. However, these strategies can erode clients’ perception of entrepreneurs’ credibility and reliability as well as the services and goods they provide. This highlights the need for market participants to develop shared norms and an understanding of these concealment strategies.

The online gambling market in China

Gambling, including online gambling, is heavily regulated in mainland China. Even though China has two government-authorized lotteries, the China Welfare Lottery and the China Sports Lottery, they do not provide online betting services.Footnote 1 The gambling games offered lack variety and have relatively low payout rates, which may not provide enough entertainment and excitement for players. As a result, the illegal online gambling market emerged to provide more convenient and accessible gambling games, as well as more thrilling experiences that satisfy players’ demands for entertainment.

Online gambling games can be divided into three major categories (see Table 1). The first category consists of lottery games, where the outcomes usually depend on the players’ luck. Mark Six (liuhecai, a 7-out-of-49 lottery-style game with six general winning numbers and one special winning number) and shishicai, a fast-paced gambling game where players select random numbers or number combinations are typical examples. The second category is sports and race betting, where players place bets on the outcomes of sporting events such as football, basketball, motor racing, horse racing, and electronic sports. Sports and race betting differ from other forms of online gambling in that they combine the thrill of gambling with the entertainment of watching sports (Church-Sanders, 2011). This creates an immersive experience for players, adding to their sense of entertainment, relaxation, and excitement. For example, during the overlap of the 2022 World Cup and the lockdown imposed by China’s zero-COVID policy, online football betting helped players alleviate boredom and provided them with a topic of conversation, which enabled them to keep interacting with their friends in spite of the social distancing.Footnote 2 Alongside the popularity of video games and electronic sports, skin gambling has emerged and prevailed in recent years (Shan, 2023). Players wager virtual items or “skins” (i.e. cosmetic items used in video games to alter the appearance of a player’s character and weapons) as a form of currency (Zhang, 2023). The third popular category of online gambling games is poker and mah-jong, where skill and strategy, as well as chance, determine the outcome (Gainsbury, 2012).

The operation of gambling games is technically underpinned by digital and telecommunications infrastructure, websites, software, and social media platforms. Online gambling, especially lotteries and sports and race betting, is often conducted on dedicated gambling websites and software. These platforms offer functions such as placing bets, displaying real-time odds, and facilitating payment of deposits and winnings. These websites and platforms are well-organized, integrated and highly automated, allowing users to engage in illegal transactions with operators or their agents.Footnote 3

Poker and mah-jong are commonly played on gaming-specific apps. Operators usually make use of social media platforms like WeChat and QQ to establish chat groups that enable players to communicate with each other and with the operator. Operators also rely on these chat groups to organize games, facilitate payment transactions, and collect debts or winnings. During the process, operators serve as third-party enforcers, and they earn commissions for their role in facilitating the games.

Both internet technologies and social media platforms, as infrastructural supports, are not sufficient to sustain the illegal online gambling market, however. Institutional arrangements are also needed to mitigate both market-based risks and government repression. Empirical evidence shows that operators have developed strategies to marketize their services, ensure fair play, facilitate the collection of gambling debts, and avoid police attention. A crucial issue for the survival of the market is debt collection, and there are two main approaches to this. The first involves settling gambling debts between players and operators ex post, with players paying their debts or operators paying out winnings after the games have ended. This method is commonly known as a ‘credit-based transaction platform’ (xinyu wang) and relies on credible commitments made by players and operators. Like credit cards, credit-based transaction platforms enable players to place bets without deposits, which motivates them to engage in gambling activities. The second approach settles gambling debts ex ante. Websites and software adopting this approach are known as ‘cash-based transaction platforms’ (xianjin wang) and require deposits from players before gambling can begin.

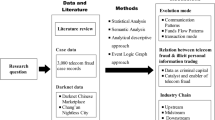

Method and data

This article is based on empirical data collected through in-depth offline and online interviews conducted between 2021 and early 2023. We conducted 47 individual and 10 group interviews with stakeholders in the online gambling market, including players (n = 26), agents (n = 8), and operators (n = 22), as well as six police officers and a prosecutor who provided valuable insights (see Table 2). We conducted interviews in four cities (Chaozhou, Guangzhou, Meizhou and Shenzhen) in Guangdong province and two cities (Ganzhou and Shangrao) in Jiangxi province.

China’s online gambling market operates clandestinely, making it very challenging for researchers to find participants, particularly operators and agents. It is even more challenging to gain their trust and convince them to be interviewed. To address these challenges, we used the snowball sampling method to generate a pool of participants. We selected sites where we had already established trust relations with acquaintances who could help us persuade suitable participants to accept our invitation. Being vouched for by these acquaintances was essential for building trust with participants whom we had not previously contacted (Wei et al. 2023). The trust we gradually established significantly increased their willingness to share their stories and perceptions.

We ensured confidentiality during our interviews by disallowing participants from disclosing any sensitive information, such as names and IDs of offenders or criminal enterprises, if the information had not been revealed by the media to the public. The existence of social connections or the involvement of trusted middlemen made participants believe that we would use their personal experiences and opinions in an appropriate and secure way. Besides informing participants about our ethical guidelines for interviews, we used their nicknames when communicating with them. This tactic not only helped protect their privacy but also gave them the impression that we were professional and reliable, which, in turn, strengthened their willingness to share their knowledge, stories, and experiences. Moreover, we often initiated the interviews with a casual conversation about participants’ daily lives and some interesting stories about our mutual friends. The use of warm-up questions made our participants feel relaxed and comfortable, which helped encourage them to share their experiences and perceptions concerning the gambling market. As trust was gradually built, many participants were willing to introduce us to their friends or partners involved in gambling activities.

We also sought to include participants from as many cities as possible. This strategy not only helped us mitigate selection bias during the identification of interviewees (Robinson, 2014) but also enabled us to expand our interview data pool. Given the illegal nature of online gambling, conducting interviews with dozens of participants, particularly agents and operators, in a single city was impractical. By selecting interviewees from six cities, we were able to gain valuable information regarding players’ gambling preferences, illegal entrepreneurs’ strategies to mitigate market-based uncertainty and the risk of criminal punishment, and the response of local law enforcement to illegal online gambling. While our interview data may not be comprehensive, it provides valuable insights into the social order of China’s illegal online gambling market.

Besides conducting in-person interviews, we also recruited intervieweesFootnote 4, particularly players, online. We conducted interviews over the phone, particularly during the 2022 World Cup when online betting on football was widespread. It was a period of restrictive COVID-19 lockdown in China, and offline interviews were less feasible. Unlike agents and operators, who were cautious about being approached by strangers, those betting on football were less likely to face criminal charges and were thus more willing to share their motivations, experiences, and opinions. Given that the risk and severity of punishment are fairly low for players, the monetary awards serve as an effective mechanism to motivate players to participate in our interviews. These interviewees were diverse in terms of their city of origin and level of gambling experience. The phone interviews created a helpful set of data on China’s online gambling market, complementing the data obtained through in-person interviews. In order to understand the mechanisms used to settle gambling debts, we employed a game theoretical model with game trees (e.g. the extensive form) to show our empirical data on the strategic interactions between players and operators or agents, which will be discussed later in this article.

Mitigating market-based risks

Our empirical data shows that participants in China’s online gambling market have developed strategies and organizational structures to signal trustworthiness, gain the trust of exchange partners, and facilitate illegal transactions. Of the three major categories of online gambling games (see Table 1), the following discussion focuses on the first and second categories of online gambling games facilitated by gambling websites and software. The discussion also includes an explanation of how social media platforms facilitate gambling games that belong to the third category.

Organization, marketing, and ensuring fair play

To attract clients, online gambling operators and agents need to market and advertise their products and services. Commonly adopted marketing approaches, such as television advertising, are obviously unavailable, so operators and agents must find alternatives. The most typical way to attract clients is to use personal networks. As our empirical data and Fig. 1 show, operators and agents of web-based and software-based gambling platforms often resort to a pyramid-like structure to scale up their business. Our observation is consistent with the existing literature. For example, Liu (2023) randomly selected 100 cases from China Judgement Online concerning charges of operating casinos and found that a pyramid-like structure was adopted in up to 74 cases. Operators act as ‘shareholders’ and establish two or three layers of agents. These operators are typically composed of individual bookmakers who take a significant share of the money wagered. These operators often have a clear division of labour based on their skills, resources, and experience. Some are technical experts responsible for providing overseas servers and designing and managing gambling platforms. Others possess extensive social networks that bring in agents and customers. Some are members or leaders of local gangs or have close ties with these gangs, allowing operators to resort to threats and violence if necessary. Finally, there are influential or wealthy individuals serving as operators who convey an image of competence and credibility, signalling the trustworthiness of their platforms.Footnote 5

In the pyramid-like structure, agents may be referred to by other titles, such as ‘general agents’ or ‘directors’. Agents at a lower level are developed and managed by those at a higher level. Their role is to seek out clients and provide them with services, such as assisting them with registering on websites and placing bets. The profits of these agents primarily come from service fees (shui) offered by operators. These fees are typically a certain percentage of the amounts wagered by their clients, who are also known as ‘members’. As an agent advances, their percentage of service fees also increases. The specific level of service fee is subject to market competition and may vary. As one interviewee mentioned, the service fee once dropped from 10% to 2% as more operators and agents entered the market.Footnote 6

In social-media-platform-based gambling, however, operators do not develop such a comprehensive organizational structure. They rely on their personal networks to identify and attract players, and they use platforms such as WeChat and QQ to manage their players and enforce agreements. They often reward individuals who introduce new players by giving them red envelopes that usually contain cash.Footnote 7

Furthermore, the growth of live streaming in China has given rise to the emergence of informal sports presenters, known as anchors, who draw in viewers to bet on sports streaming applications such as Justfun, QiE.tv, and Blue Whale Sports. These anchors have expertise in specific sports and good knowledge of athletes, which allows them to provide insightful commentary and make more accurate predictions about match outcomes than an ordinary gambler could. Recognizing the value of these anchors in attracting gamblers, operators often establish partnerships with them. Figure 2 depicts a progressive rewards system that motivates anchors to attract more gamblers.Footnote 8 Anchors demonstrate their exceptional prediction abilities by regularly posting their prediction records on their personal websites.Footnote 9

The information mentioned in the panel on the left indicates that sports anchors who collaborate with gambling websites to attract new players will receive monetary rewards. The rewards increase with the number of players that the anchor attracts. For instance, the anchor could receive a reward of 300 RMB from the gambling website when they attract the first player for the website. Attracting a second player could bring an additional reward of 400 RMB, while the third player could bring a reward of 500 RMB, and the fourth one 600 RMB. The rewards can go as high as 1000 RMB per player.

Additional marketing methods operators use include spam messages and emails sent indiscriminately to potential gamblers, as well as pop-up advertisements on certain websites, especially those associated with pornography or electronic gaming. One interviewee mentioned that during the 2022 World Cup, she was frequently exposed to such advertisements and noticed that ‘the gambling apps were very active’.Footnote 10To attract new players, gambling websites and software companies often offer coupons and bonuses to incentivize registration.

Operators of gambling platforms make great efforts to ensure fair play, or at least convince potential clients that the gambling games they provide are not subject to outcome manipulation. To ensure fair play, operators often use focal/reference points to show that their games are determined by chance rather than any external factors. Specifically, the outcomes of illegal online gambling games are derived from those of licensed, legalized gambling, or high-profile matches. For example, the popular but illegal lottery game Mark Six, which is run in mainland China, uses winning numbers based on those of the licensed Mark Six in Hong Kong. Mainland Chinese operators may offer players additional wagering options, such as betting on a single general winning number or the even or odd nature of the winning special numbers, but the winning numbers remain identical to those of the licensed Hong Kong game.

Similarly, when it comes to sports or race betting, operators usually base their illegal gambling games on high-profile matches. This is because gamblers tend to believe that high-profile matches are less likely to be fixed. As a football fan explained:

Athletes who compete in lesser-known matches may not earn as much money or receive the same level of recognition and sense of achievement from their sport as those who compete in televised matches. I don’t think these athletes [who compete in lesser-known matches] would refuse the opportunity to earn quick money [by engaging in match-fixing]. But for athletes in top-level matches, for example, I don’t think that an athlete in the Argentina vs. France final would say, ‘I’ll take money to let the opponent win.’ It’s a lifelong honour that they wouldn’t compromise.Footnote 11

In another popular lottery game, shishicai, operators from different gambling platforms base their games on results from a well-known website called 168, which acts as a third party for lottery draws.Footnote 12 Because many platforms use 168 as their reference point for the outcomes of lottery games, the likelihood of outcome manipulation in 168 is very low. Therefore, using a well-known website as the reference point can be seen as a signal of credibility and trustworthiness.

Settling gambling debts

Settling gambling debts is a crucial issue in the online gambling market. As previously mentioned, gambling websites, software and applications can be divided into two categories: credit-based transaction platforms that settle gambling debts ex post and cash-based transaction platforms that settle debts ex ante. The smooth operation of credit-based transaction platforms is dependent on credible commitments made by players and operators. Our empirical data shows that the operators of credit-based platforms are wealthy, influential people who are strongly motivated to pay out winnings in order to avoid damaging their social standing and losing users to competing platforms.Footnote 13

Operators or agents of credit-based platforms use several mechanisms to ensure players to pay their gambling debts. To better understand the operation of the institutional mechanisms adopted to settle these debts, we employed a game tree to capture the strategic interaction between operators or agents and their familiar or unfamiliar players (see Fig. 3). Each branch of the tree shows the strategy of operators or agents and players with respect to paying or collecting debts, and the equilibrium indicates the outcome of their interaction under certain conditions.

When operators or agents deal with players they are familiar with, they often do not require players to pay a deposit; they rely on the reputation systems embedded in interpersonal networks, rather than violence, to recover gambling debts. In a pyramid-like structure, agents are responsible only for collecting gambling debts from their own clients. If a client fails to pay, the agent who owns that client must cover the debt; the higher-level agent is not responsible for collecting these debts. This structure incentivizes agents to carefully assess the trustworthiness of their clients, which helps to minimize the risk of non-payment.

Agents consider three key elements when evaluating their clients. First, they prefer to work with people they already know. As an agent we interviewed noted: ‘It must be someone with whom we are familiar and who can be easily located, such as a relative or very close friend, so that they cannot escape [their debts].’Footnote 14 Second, related to the first point, agents need to target credible players. As one interviewee noted, ‘developing trustworthy players is the only solution [that ensures gambling debt collection], because the authorities do not acknowledge these debts.’Footnote 15 Agents often rely on information provided by their network of acquaintances to identify potential gambling players with a good reputation. A player with a reputation for debt evasion is not welcome and can even be ostracized in the social network.Footnote 16 Third, agents often prefer clients with financial capacity, as this closely correlates with the probability that the clients will honour their debts. An operator shared with us how he judged a player’s trustworthiness by saying, ‘if a player is rich, he has credit.’Footnote 17 Likewise, another operator noted, ‘I evaluate a player’s trustworthiness based on how wealthy they are.’Footnote 18

Agents on credit-based platforms evaluate players’ trustworthiness and financial capacity and use this evaluation to determine the level of credit to grant. Once gambling debts exceed the credit limit, players must settle their debts before they can continue betting. As shown in the upper part of Fig. 3, when operators and agents deal with players they are acquainted with, the reputation mechanism is generally sufficient to ensure prompt debt settlement by players. When operators or agents collect debts ex post and players fulfil their obligations, the assurance of the reputation mechanism creates an equilibrium. In most cases, threats, violence, and police intervention are not necessary to enforce compliance.

To maximize profits, operators and agents must expand their pool of clients by attracting people they have not yet known, but the reputation mechanism is not sufficient for settling debts with such players. Before China’s ‘sweep away black’ campaign, unfamiliar players were not required to pay deposits in order to gamble. To ensure that players fulfilled their obligations, operators and agents commonly relied on threats, violence, and even self-ham. An interviewee who was an agent told us:

In the past, we resorted to self-harm to collect debts. Self-harm works like this: we’d come to your (i.e. a player in debt) house, and if you refused to pay, our collector would take a beer bottle and smash it on their own head. If you still refused to pay, they would do it again.Footnote 19

Local police opted not to intervene even when debtors reported being victimized by gang methods, because police officers were not responsible for dealing with interpersonal lending disputes. As discussed, some operators and agents are themselves members or leaders of local gangs and often manage offline gambling houses before becoming involved in online gambling businesses. The use of gang methods to enforce agreements was not uncommon in collecting debts resulting from online gambling.Footnote 20

To reduce the risk of police crackdown, gangsters often employed ‘soft violence’ (ruan baoli, psychological coercion without causing physical injuries) to enforce compliance. Soft violence methods included blocking access to a debtor’s home, splashing paint on the door of debtor’s home, and occupying the debtor’s home until the debts were settled.Footnote 21 In most circumstances, the threat of soft violence was enough to compel debtors to pay their debts. An operator of an online mah-jong gambling platform based in Chaozhou, a city in Guangdong province, mentioned that he used to invite a professional debt collector to help him recover debts from a player in Beijing, a long way from Chaozhou. The debt collector sent a message to the debtor stating that he knew her home address and would visit her there and cause a disturbance if the debt remained unpaid.Footnote 22 This message was enough to persuade the debtor to fulfil her obligations.

In 2018, the Chinese government launched a nationwide anti-crime campaign named ‘sweep away black’ to combat the widespread use of soft violence (Wang 2020a). This campaign targeted gambling operators and agents who used gang methods to collect debts. Many debtors took advantage of the government’s intensive efforts to eradicate gangs and repress illegal markets to escape their obligations. As a number of interviewees mentioned, debtors could threaten agents or operators: if an agent pursued a debt, the debtor would report the agent’s involvement in illegal gambling to the police (as the lower right part of Fig. 3 shows).Footnote 23 An experienced agent told us:

When a player loses a lot of money [in gambling], he may choose to report the gambling activities to the police…. He will be fine, but his agent will be taken away (i.e. arrested) by the police.Footnote 24

The decreased cost-effectiveness of gang methods or soft violence and the increase in associated risks compelled operators and agents of online gambling platforms to change how they got paid from ex post to ex ante. In other words, as Fig. 3 shows, prior to the ‘sweep away black’ campaign, the threat or use of violence ensured that unfamiliar players paid their debts ex post. However, after the ‘sweep away black’ campaign, violence became a more risky strategy, leading to a change in the equilibrium of participants’ interaction so that operators and agents now require deposits from players.

As a result of the anti-crime campaign, cash-based transaction platforms have become increasingly popular; they complement and sometimes replace credit-based transaction platforms. In other words, settling gambling debts through payment of deposits has become an increasingly important mechanism. Operators and agents only allow a limited number of players who are very trustworthy and financially sound to stay on a credit-based transaction platform and settle their debts ex post. However, requiring deposits puts players at a disadvantage: dishonest operators and agents may withhold players’ deposits and refuse to pay out winnings. To address players’ concerns, operators and agents must demonstrate their trustworthiness. One way for operators to signal trustworthiness is to establish their online platform as a high-profile brand. Operators, therefore invest in increasing the exposure of their platforms to potential players. For instance, Yabo, a high-profile sports betting platform, sponsors football teams and matches, and its brand logo is printed on team uniforms and on advertising hoardings in football stadiums.Footnote 25 When an online gambling platform has a significant market presence, players are less likely to fear that the platform’s operators and agents will engage in dishonest practices.Footnote 26

Another way for operators to increase players’ sense of safety is to set up user-friendly interfaces and establish convenient and secure payment methods. As Fig. 4 shows, the gambling platform—Oubao—not only provides 13 payment methods but also informs clients about scams they may encounter when gambling. The user-friendly interface developed by this gambling platform also increases players’ trust in the platform. One player told us that the clean, simple interface boosted her confidence in using the OB sports platform, another well-known gambling platform.Footnote 27

Dear Members, Recently, we discovered that in certain regions (such as Zhen, Nanning, etc.), some base stations are sending suspicious messages or making calls to deceive players into clicking on links to withdraw funds. Please do not trust any calls or messages requesting you to “click to confirm receipt.” Please always verify the amount through your mobile banking app. If you need assistance, please contact our 24-h online customer service.

Avoiding police crackdowns

Avoiding criminal investigation, prosecution and imprisonment is a significant task for all online gambling participants, particularly operators and agents. An avoidance strategy for operators and agents is to purchase protection from police officers by bribing them. Operators and agents described to us the methods they use to establish friendly relations with local police officers; for instance, they invite officers to expensive restaurants,Footnote 28 purchase cigarettes for them,Footnote 29 or pay monthly protection fees.Footnote 30 Some operators even offer police officers a certain percentage of their business shares.Footnote 31 In return, these corrupt police officers choose not to enforce the law against the operators and agents who pay them and also give the operators confidential information about police anti-gambling initiatives.

Operators and agents also use technology and internet anonymity to avoid the legal consequences of their actions. Some operators rent web servers located overseas, for instance in Hong Kong, Taiwan, or Cambodia, which makes it difficult for police officers to trace the location of a gambling platform.Footnote 32 Operators also frequently alter network routings to their websites and update the security codes for player accounts. As an operator explained:

We change our security codes monthly in order to avoid our business being reported to the police and to prevent police investigation of our players and agents. If one of us is placed under criminal investigation, we promptly change the security code and website to reduce the risk of others being implicated.Footnote 33

As Fig. 5 shows, when using social media platforms to organize gambling activities, operators and agents frequently remind players to avoid using sensitive words or sharing screenshots related to the gambling platform, because this can attract police attention. A player shared with us the insider language used during the 2022 World Cup:

We use ‘pizza’ to indicate the Italian team and ‘helicopter’ to indicate the French team. For instance, ‘a piece of pizza and two helicopters’ means a player is betting on the Italians losing 1–2 to the French.Footnote 34

Group Announcement: Rules for the Lazy Lady World Cup Group: 1. Please be cautious when you exchange in private transactions; if you are cheated, this group will not take any responsibility. 2. Don’t flood the screen, please discuss normally. 3. Please avoid using sensitive words such as lottery, superstition, magic, witchcraft, etc. You can use pinyin instead. Do not post lottery screenshots or the group will be blocked. 4. Please state your purpose when adding the group manager as your WeChat friend.

To prevent leaving a trail that could aid a criminal investigation, agents often suggest that players settle debts with cash instead of electronically.Footnote 35 If electronic payment is unavoidable, operators and agents often use a ‘puppet’ to handle the transactions. Specifically, a ‘puppet’ refers to an elderly person who is willing to sell their personal identification information for profit. Operators and agents use intermediaries to purchase the identification, phone SIM card, bank account, and login details for online platforms such as Alipay and WeChat of elderly people and use these accounts for money transfers. If police investigate these transactions, they will only get as far as the puppet, an elderly person who has no connection to the operators and agents of the gambling platform, is unaware of the illegal gambling activities, and is not criminally liable. This strategy poses significant technical challenges for law enforcement agencies. As one police officer acknowledged, it can be highly challenging and resource-intensive to identify all the participants involved in a case of illegal online gambling and ascertain the amount of money being wagered.Footnote 36

Discussion

Since the mid-1990s, illegal gambling operations that were primarily organized locally and regionally have moved to the Internet and become globalized (Spapens, 2014). Gambling, both online and offline, is subject to varying forms of regulation in different jurisdictions (Newburn, 2018). Some countries, such as member states of the European Union, regulate most types of gambling, while other countries, like the United States, and jurisdictions such as Macau, legalize and regulate specific types of gambling, such as casinos and sports betting (Spapens, 2014). The gambling industry in mainland China deserves further examination, because the Chinese authorities outlaw most types of gambling, and the two state-sanctioned lotteries are far from sufficient to meet players’ increasing demands for entertainment and excitement.

The rapid development of information technologies and the disparity in government regulation of gambling across different jurisdictions have significantly facilitated the growth of the online gambling industry in mainland China. In contrast to traditional and local gambling businesses (e.g. gambling houses) that often face a significant risk of criminal prosecution, criminal entrepreneurs who operate online gambling businesses are often able to avoid detection and criminal punishment by using internet anonymity and renting web servers overseas. These entrepreneurs set up user-friendly interfaces, establish convenient payment methods, and use outcomes of foreign-licensed gambling and high-profile matches as reference points to convey clear signals of trustworthiness and their competence to ensure fair play. Through intense communication with players in online chat groups, illegal entrepreneurs have managed to create new norms: the frequent altering of network routings to their websites and the periodic updating of the security codes for player accounts, which have been widely accepted by all players.

The case study of online gambling in China enables researchers to explore the offline dimensions of illegal online gambling businesses. We find that interpersonal trust relationships are the starting point for the launch of this type of illegal business in cyberspace and play an essential role in establishing the pyramid-like structure, deterring opportunistic behaviour, attracting potential customers, and enforcing loan repayment. Nevertheless, the online gambling business is not restricted to interpersonal trust relationships, because operators and agents at various levels can expand their businesses beyond direct personal interactions. They use spam messages and emails and outsource many marketing tasks to anchors. The adoption of these marketing strategies enables operators and agents to attract new players with whom they do not have existing offline connections. This generates the need for operators to use cash-based transaction platforms to regulate these new players’ gambling activities and settle gambling debts.

The study of online gambling in China also provides an ideal opportunity for researchers to examine the effects of law enforcement actions on the operation of illegal businesses in cyberspace. Increased law enforcement due to China’s latest anti-crime campaign has brought higher levels of risks and uncertainties, especially for operators and agents of online gambling who still prefer to use coercion and violence to enforce overdue loans. To lower the risk of detection and criminal prosecution, which can be achieved by reducing reliance on violence and coercion, operators and agents have to replace credit-based transaction platforms with cash-based transaction platforms, especially when they regulate new players’ gambling activities on their websites or apps. This gives rise to two consequences: on the one hand, increased reliance on cash-based transaction platforms may discourage potential customers from gambling on these platforms, requiring operators to demonstrate clearer and stronger signals of their trustworthiness than before by improving their online persona, websites, and apps; on the other hand, the common use of cash-based transaction platforms has reduced operators and agents’ reliance on interpersonal trust relationships, which may allow operators to expand their gambling businesses beyond interpersonal connections. The topic of the extent to which increased reliance on cash-based transaction platforms constrains or expands online gambling businesses deserves further empirical investigation.

Conclusion

Participants in illegal online markets encounter substantial risks because they lack access to contract enforcement provided by state institutions and face the threat of police investigation. Furthermore, their interactions are facilitated and constrained by Internet anonymity. Despite these risks, illegal markets continue to flourish online. However, until recently, there has been little empirical research examining how participants in illegal online markets use both offline and online strategies to address the risks they face. This article aims to fill the literature gap by focusing on a case study of the illegal online gambling market in China and examining the extralegal governance institutions that have been developed to address both market-based uncertainty and the risk of criminal prosecution.

Drawing on in-depth interviews, this article reveals the operation and evolution of institutional mechanisms that ensure cooperation and minimize risk in the illegal online gambling market. Our empirical evidence suggests that operators and agents of illegal online gambling platforms develop a pyramid-like structure to manage their businesses and incentivize agents to attract players. They also use live streams, spam emails, and pop-up advertisements on websites to increase their pool of potential customers. Moreover, operators and agents seek to convince players that they can ensure fair play by directly referring to the outcomes of licensed gambling websites and high-profile overseas sports matches or outcomes provided by trustworthy third parties. China’s recent efforts to repress organized crime and illegal markets have led to a decreased use of threats of violence by illegal market participants, a decline in credit-based transaction platforms, and the rapid development of cash-based transaction platforms. Operators and agents now prefer to settle gambling debts by requiring deposits from players. In addition, bribing police officers and using network technologies remain complementary strategies for reducing the risk of criminal punishment.

In the digital era, illegal online transactions have become increasingly prevalent, causing harm to society and presenting additional challenges to law enforcement agents. Researchers can contribute to addressing these challenges through theoretical and empirical examinations of illegal online markets. More research is needed to understand how offline mechanisms facilitate illegal online transactions, how network technologies promote the exchange of illegal goods and services in cyberspace, and how law enforcement actions influence the evolution of strategies used by illegal entrepreneurs. We hope our work will focus scholarly attention on illegal markets and assist further research and policy development.

Data availability

The data utilized is subject to confidentiality restrictions. Following the research ethics, the researchers have the responsibility to protect the privacy of the interview participants; the interview data, therefore cannot be shared. Regrettably, we are unable to fully share the data publicly. However, if readers have a specific interest or a reasonable need to access the data, we encourage them to contact the corresponding author for further details and potential arrangements.

Notes

The China Sports Lottery used to offer online betting services, but these services were shut down in 2014.

Interviews IG202210, IG202211, IG202218, IG202220, and IG202222.

Operators of gambling websites and software are shareholders. They not only collect service fees from players but also engage in gambling games directly. Agents, on the other hand, only charge service fees; they do not participate in gambling games. In order to incentivize agents to sign up more players, operators sometimes distribute a portion of the profits from service fees to agents. For a more detailed discussion, please refer to the section “Mitigating market-based risks”.

The majority of interviewees were betting on football.

Interview IG202101, IG202103, IG202108, IG202110, IG202112, and IG202113.

Interview IG202116.

Interview IG202113.

Interview IG202205.

Interview IG202206.

Interview IG202220.

Interview IG202213.

Interview IG202113.

Interview IG202109, IG202114, IG202116, and IG202302.

Interview IG202212.

Interview IG202215.

Interview IG202113.

Interview IG202111.

Interview IG202201.

Interview IG202203

Interview IG202114 and IG202301.

Interview IG2021101 and IG202115.

Interview IG202117.

Interview IG202102, IG202103, IG202105, IG202106, IG202107, IG202108 and IG202111.

Interview IG202101

Interview IG202217.

Interview IG202210.

Interview IG202217.

Interview IG202106.

Interview IG202102.

Interview IG202103.

Interview IG 202129.

Interview IG202108, IG202111, and IG202113.

Interview IG202103.

Interview IG202211.

Interview IG202207.

Interview IG202125.

References

Albanese JS (2018) Illegal gambling businesses and organized crime. Trends Organ Crime 21:262–277

Andreas P, Wallman J (2009) Illicit markets and violence. Crime Law Soc Change 52:225–229

Banks J (2014) Online gambling and crime. Routledge, London

Barzel Y (2002) A theory of the state. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bolton GE, Ockenfels A (2009) The limits of trust in economic transactions. In: Cook KS, Snijders C, Buskens V, Cheshire C (eds) eTrust. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp. 15–36

Brooks G (2012) Online gambling and money laundering. J Money Laund Control 15(3):304–315

Campana P, Varese F (2013) Cooperation in criminal organizations. Ration Soc 25(3):263–289

Cheng Y, Mukhopadhyay A, Williams P (2020) Smiling signals intrinsic motivation. J Consum Res 46(5):915–935

Church-Sanders R (2011) Online sports betting. iGaming Business, London

Décary-Hétu D, Dupont B (2013) Reputation in a dark network of online criminals. Glob Crime 14(2–3):175–196

Dellarocas C (2003) The digitization of word of mouth. Manag Sci 49(10):1407–1424

Dewey M (2019) The characteristics of illegal markets. oxford research encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.486

Dixit AK (2004) Lawlessness and economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Durán-Martínez A (2017) The politics of drug violence. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Ellickson RC (1991) Order without law. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Ert E, Fleischer A, Magen N (2016) Trust and reputation in the sharing economy. Tour Manag 55:62–73

Gainsbury S (2012) Internet gambling. Springer, New York

Gainsbury S (2015) Online gambling addiction. Curr Addictn Rep 2:185–193

Gambetta D (1996) The Sicilian Mafia. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Gambetta D (2009) Codes of the underworld. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Gambetta D (2011) Signaling. In: Hedström P, Bearman P, Bearman PS (eds) The Oxford handbook of analytical sociology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 168–194

Gambetta D, Przepiorka W (2019) Sharing compromising information as a cooperative strategy. Sociol Sci 6:352–379

Giardini F, Wittek R (eds) (2019) The Oxford handbook of gossip and reputation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gintis H, Smith EA, Bowles S (2001) Costly signaling and cooperation. J Theor Biol.213(1):103–119

Greif A (2006) Institutions and the path to the modern economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hall A, Antonopoulos GA (2016) Fake meds online. Springer, New York

Hardy RA, Norgaard JR (2016) Reputation in the Internet black market. J Inst Econ 12(3):515–539

Holt TJ, Smirnova O, Chua YT, Copes H (2015) Examining the risk reduction strategies of actors in online criminal markets. Glob Crime 16(2):81–103

Hutchings A, Holt TJ (2015) A crime script analysis of the online stolen data market. Br J Criminol 55(3):596–614

Kim HS, Wohl MJ, Salmon MM, Gupta R, Derevensky J (2015) Do social Casino gamers migrate to online gambling? J Gambl Stud 31:1819–1831

Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD (2012) Internet gaming addiction. Int J Ment Health Addctn 10:278–296

Leeson PT (2008) Social distance and self-enforcing exchange. J Leg Stud 37:161–188

Leeson PT (2009) The invisible hook. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Leukfeldt ER, Kleemans ER, Stol WP (2017a) Cybercriminal networks, social ties and online forums. Br J Criminol 57(3):704–722

Leukfeldt ER, Kleemans ER, Stol WP (2017b) The use of online crime markets by cybercriminal networks. Am Behav Sci 61(11):1387–1402

Lev-On A (2009) Cooperation with and without trust online. In: Cook KS, Snijders C, Buskens V, Cheshire C (eds) eTrust. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp. 292–318

Lin W, Kang S, Zhu J, Ding L (2024) Till we have red faces: drinking to signal trustworthiness in contemporary China. Public Choice. Available via https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11127-024-01180-2. Accessed 30 Oct 2024

Lin W, Lin GC (2023) Strategizing actors and agents in the functioning of informal property rights. World Dev 161:106111

Liu K (2023) Dilemma and path of online gambling crimes governance in information age. J Liaoning Coll 142(6):49–57. (in Chinese)

Lo TW, Kwok SI (2017) Triad organized crime in Macau Casinos. Br J Criminol 57(3):589–607

Lusthaus J (2012) Trust in the world of cybercrime. Glob Crime. 13(2):71–94

Lusthaus J (2018) Industry of anonymity. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Lusthaus J, Varese F (2021) Offline and local. Policing 15(1):4–14

McMullan J, Rege A (2007) Cyberextortion at online gambling sites. Gaming Law Rev 11(6):648–665

Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China (2023) National lottery sales in December 2022. Available via http://zhs.mof.gov.cn/zonghexinxi/202301/t20230131_3864601.htm. Accessed 5 Apr 2023

Möhlmann M, Geissinger A (2018) Trust in the sharing economy.In: Cook NM, Snijders M, Buskens JJ (eds) eTrust. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 27–37

Newburn T (2018) Criminology: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Posner EA (1998) Symbols, signals, and social norms in politics and the law. J Leg Stud 27:765–797

Raub W, Keren G (1993) Hostages as a commitment device. J Econ Behav Organ 21(1):43–67

Richman BD (2017) Stateless commerce. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Riegelsberger J, Sasse MA, McCarthy JD (2007) Trust in mediated interactions. In: Joinson A, McKenna K, Postmes T, Reips UD (eds) Oxford handbook of Internet psychology. Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp. 54–69

Robinson OC (2014) Sampling in interview-based qualitative research. Qual Res Psychol 11(1):25–41

Schelling TC (1971) What is the business of organized crime? Am Sch 40(4):643–652

Shan YC (2023) Research on online gambling crime and its countermeasures. Netw Secur Technol Appl 7:135–139. (in Chinese)

Shortland A (2017) Governing kidnap for ransom. Governance 30(2):283–299

Skarbek D (2014) The social order of the underworld. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Skarbek D (2020) The puzzle of prison order. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Skarbek D, Wang P (2015) Criminal rituals. Glob Crime 16(4):288–305

Spapens T (2014) Illegal gambling. In: Paoli L (ed) The Oxford handbook of organized crime. Oxford University Press, New York. pp. 402–418

Standifird SS (2001) Reputation and e-commerce. J Manag 27(3):279–295

Thomala L (2023) Market scale of the online gaming market in China 2016–2022. Available via https://www.statista.com/statistics/284942/market-volume-of-online-gaming-market-in-china/. Accessed 5 Apr 2023

Trevaskes S (2007) Severe and swift justice in China. Br J Criminol 47(1):23–41

Varese F (2011) Mafias on the move. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Varese F, Wang P, Wong RW (2019) Why should I trust you with my money. Br J Criminol 59(3):594–613

Wang P, Antonopoulos GA (2016) Organized crime and illegal gambling. Aust NZ J Criminol 49(2):258–280

Wang P (2020a) Politics of crime control. Br J Criminol 60(2):422–443

Wang P (2020b) How to engage in illegal transactions. Br J Criminol 60(5):1282–1301

Wang P, Su M, Wang J (2021) Organized crime in cyberspace. Br J Criminol 61(2):303–324

Weber M (2004) The vocation lectures. Hackett Publishing Company, Cambridge

Weesie J, Raub W (1996) Private ordering. J Math Sociol 21(3):201–240

Wei S, Jiang A, Hu Q, Liang B, Xu J (2023) Conducting criminological fieldwork in China: a comprehensive review and reflection on power relations in the field. Criminol Crim Justice. Available via https://doi.org/10.1177/17488958231166561. Accessed 30 November 2024

Wong ILK, So EMT (2014) Internet gambling among high school students in Hong Kong. J Gambl Stud 30:565–576

Wood RT, Griffiths MD (2008) Why Swedish people play online poker and factors that can increase or decrease trust in poker websites. J Gambl Issues 21:80–97

Wood RT, Williams RJ, Lawton PK (2007) Why do Internet gamblers prefer online versus land-based venues? J Gambl Issues 20:235–252

Zhang J (2023) Skin gambling in Mainland China: survival of online gambling companies. Cogent Soc Sci 9(2):2265209

Acknowledgements

This research project has been sponsored by a grant from the Research Grants Council in Hong Kong (Project Code: 17613224). Furthermore, the authors acknowledge the support provided by the Post-doctoral Fellowship on Contemporary China, Faculty of Social Sciences, the University of Hong Kong. The authors also thank research assistants Ye Lin, Boyu Li, and Penglong Fu for their help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wanlin Lin: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, visualization. Peng Wang: Conceptualization, formal analysis, resources, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong (reference no. EA200198) on 16th November 2020. The ethical approval permits the researcher to conduct fieldwork and interviews, and collect data. The research was conducted in accordance with the guidelines set by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong.

Informed consent

All participants were adults, and no vulnerable individuals were involved. Informed consent was signed or acquired by interview participants before the interview started. Interview participants were fully informed of their rights to withdraw from the interview. They answered our questions voluntarily and without any obligation. The anonymity of participants was assured.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, W., Wang, P. The social order of illegal markets in cyberspace: extralegal governance and online gambling in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1643 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04166-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04166-z