Abstract

This paper addresses the challenge of preserving sentiment when translating sacred texts, with a specific focus on the Quran. The proposed approach combines advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques, particularly deep learning-based Transformer Language Models (TLMs), with a novel human validation approach. We present a comprehensive study involving a newly created parallel dataset encompassing the Arabic Quran and seven English translations, analyzing the preservation of sentiment. Our findings reveal compelling insights, with neutral sentiment ranging from 59% to 74% in English translations compared to 66% in the original Arabic Quran. Negative sentiment in some translations reached 25%, while others ranged from 14% to 17%, closely paralleling the 24% in the Arabic version. Additionally, the agreement analysis among English translations indicates varying degrees of alignment, reaching a Good level (κ = 0.62) or a Moderate level (κ from 0.47 to 0.6). However, compared to the original Arabic Quran, none of the translations achieved high levels of agreement, with only four translations reaching a Fair score (approximately 0.21). These findings underscore the complexities of translating the Quran, particularly its classical Arabic, and emphasize the need for improved sentiment analysis models, potentially incorporating mixed sentiment categories to capture sentiment more effectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Semantics, pragmatics and sentiments are crucial information during the translation and must be preserved. With sacred sources, this is even more vital. Islam is the second most practiced religion in the world (Brooks and Mutohar 2018). Propagated initially in the Arabian Peninsula, this religion has now spread to other non-Arabic-speaking countries worldwide. These developments have led to several translations of the Quran, the primary legal source of Islam and considered the word of God. There are more than 60 English translations of the Quran (Murah 2013; Svensson 2019) and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC)Footnote 1 lists 293 translations in 58 languages and dialects (Sefercioğlu 2000).

Although there has been a pressing need for translations of the Quran since the early years of Islam, when a sizable number of non-Arabic individuals converted to Islam, the translatability of the Quran has always been debated (Alturki 2021; Aqad et al. 2019). The Muslim community was apprehensive about carrying out the Quran translation for several reasons, including the potential for alterations in the meaning of the Quran or the permissibility of claiming any equivalence with human books (Nassimi 2008). However, the translations have aimed to bring the implications of the Quran closer to non-Arabic speakers while remaining faithful to the sacred texts.

The implications of coherence (the hidden potential meaning connection between textual elements that the reader or listener can reveal through interpretation Blum-Kulka 1986) shifts in Quranic meanings have been examined in the literature (Aghai and Mokhtarnia, 2021; Farghal and Bloushi 2012). Moreover, with four translations and their faithfulness to the original text, several problems and translation losses have also been pointed out, resulting from nonequivalence between the Arabic and the translated texts (Abdelaal 2019). It has been noted in these and other works how difficult it can be to maintain the meanings of the Quran’s verses and the sentiment they carry.

Two of the major AI branches, Machine Learning (ML) and Natural Language Processing (NLP), have been extensively used (and successfully so) on several tasks concerning the analysis of textual data (Mehmood et al. 2022; Putra and Yusuf 2021; Sait and Ishak 2023). The tide has changed with the most recent breakthrough of deep learning-based Transformers Language Models (TLMs) (Kenton and Toutanova, 2019). TLMs present state-of-the-art results for many AI, ML and NLP tasks (Wadud et al. 2023), including sentiment analysis (AlBadani et al. 2022; Aljabri et al. 2021; Birjali et al. 2021; Haris et al. 2023; Hussein 2018; Saleh et al. 2022), machine translation (Fan et al. 2021; Yang et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2021), and language understanding (Zhang et al. 2019). However, to the very best of our knowledge, there is yet to be any analysis or study that has attempted to examine the degree to which the sentiment conveyed by the whole holy Quran have been preserved, especially using cutting-edge AI technologies. Hence, it is legitimate to ask, “Does the non-Arabic speaking reader feel the same way as an Arab reader?” and “Do the translations of the Quran manage to preserve the feelings emanating from the divine text, and to what extent is this preserved?” and examine whether AI can help us to answer these questions.

As such, this paper proposes to examine the content of seven English translations of the Quran to explore the aspect of Quran translations. Our analysis begins by comparing the contents of the different manuscripts, followed by assessing the degree of concordance between them and the Quran, using a hybrid approach based on both TLMs and human validation.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: The section “Related work” presents the related work, sections “Research objectives” and “Methodology overview” describe the objectives and the methodology of the work, section “Data” details the parallel dataset creation and its content, and section “Experiments” details the sentiment analysis experiments. The results are presented and discussed in the section “Results and Discussion”. Section “Error analysis” provides an error analysis, and finally, section “Conclusion” concludes this paper.

Related Work

Translation procedures must ensure that domain knowledge is preserved and maintained from the source to the target language. Recent studies, however, indicate that many translations frequently miss holding such important information ingrained in the source language (Kumari et al. 2021). Hence, the system’s capacity to maintain the sentiment class (a.k.a sentiment preservation) is crucial. In this paper, the related literature concerning the problem of sentiment preservation in translation is approached from different perspectives, broadly classifying into two main lines of work.

On one side, as aforementioned, a body of literature has shed some light on the translation issues of the holy Quran. This line of work is the closest to the present work. For example, Farghal and Bloushi (Farghal and Bloushi 2012) prove that coherence shifts in Quran translation lead to mismatches that significantly impact the text’s meaning potential. The cultural differences between the source and target text audiences may cause certain mismatches to be reader-focused coherence shifts. In contrast, other mismatches may originate from the translator’s poor judgments and be text-focused coherence changes. It was demonstrated how reader-focused adjustments provide difficulty for translators, and footnotes and paraphrasing have proven to be the most effective methods for closing both partial and complete cultural/reference gaps. This explanatory approach aids Quran translators in avoiding endangering the meanings of the Quran.

Similarly, Rezvani and Nouraey (Rezvani and Nouraey 2014) conduct a comparative analysis based on Catford’s (Catford 1965) shift typology to investigate the frequency of various translation shifts happening in Quran translations from Arabic into English. This led to the selection of seven translations–by SarwarFootnote 2, Arberry (Arberry 1996), Irving (Irving 1992), Pickthall (Pickthall et al. 1960), Saffarzade (Saffarzade 2001), Shakir (Shakir 1985), and Yusef Ali (Ali 2000)–of the first thirty verses of the Chapter “Yusuf” in the Quran to be examined. Each component was first compared to look for any potential shifts. The Chi-Square method was then used to determine whether there were any statistically significant variations in shift frequencies. Five different sorts of changes appeared to differ statistically significantly, according to their findings.

Abdelaal (Abdelaal 2019) has also drawn attention to the difficulties encountered in the translation of a few verses from the Holy Quran and how they might be resolved in light of various theoretical and practical viewpoints. Six verses (Ayahs) from two chapters of the Quran were purposefully chosen for this purpose. They were then examined to find out that the translations of Pickthall, Abdel Haleem (Haleem, 2005) and Sarwar had several issues and lost meaning. Furthermore, Tabriziand Mahmud (Tabrizi and Mahmud 2013) examine discourse structure concerns when comparing the holy Quran’s Arabic text and English translation. They investigate the existing translations’ equivalence and accuracy of the Quran from the perspectives of entity coherence and lexical cohesion, taking into account the variations in the arrangement of sentences, phrases, and words between translations which have an impact on the outcomes of computational text analysis.

On the other side, a growing body of literature has investigated the drawbacks associated with machine translation in terms of sentiment preservation (AR et al. 2013; Barhoumi et al. 2018; Pal et al. 2014; Shalunts et al. 2016; Wan et al. 2022; Zhang and Matsumoto 2019) or studied effective ways to analyze sentiment in Arabic (Alqahtani et al. 2023; Farha and Magdy, 2021; Sherif et al. 2023; Yu et al. 2023). The issue of how sentiment is retained in machine translation has been examined as a binary or ternary classification problem. For example, Lohar et al. (Lohar et al. 2017) constructed a sentiment classifier to study both sentiment preservation and translation quality under the hypothesis that when translation quality is low, sentiment may not be appropriately preserved. The finding was that dividing the sentiment classes into the training data for the machine translation system increased sentiment preservation in the target language. Moreover, Lohar (Lohar 2020) looked into the quality of machine translation and sentiment preservation in the context of user tweets paying particular attention to whether or not sentiment categorization aids in sentiment preservation. It was directed mainly to improve the machine translation quality of tweets while maintaining sentiment polarity through a sentiment classification-based machine translation model.

Similarly, Saadany and Orasan (Saadany and Orasan 2020) analyzed the difficulties of translating book reviews from Arabic to English, with an emphasis on the mistakes that result in the wrong translation of sentiment polarity. It highlights the unique qualities of Arabic User Generated Content (UGC), investigates sentiment transfer errors when translating Arabic UGC to English, and examines the reasons why the issue arises. Investigation shows that the output of machine translation technologies for Arabic UGC can either fully reverse the sentiment polarity of the target word or phrase and provide the erroneous emotional message or fail to transmit the sentiment at all by providing a neutral target text. Likewise, Saadany et al. (Saadany et al. 2021) present a way to determine if automatic translation techniques can successfully convey sentiment in UGC. There are linguistic characteristics that are unique and difficult to translate sentiment into other languages, they found. The characteristics that best summarize these difficulties and indicate how frequently each characteristic occurs in various language combinations were described.

Kumari et al. (Kumari et al. 2021) and Si et al. (Si et al. 2019) follow a slightly different road. For example, Kumari et al. provide a deep reinforcement learning approach to fine-tune the parameters of a neural machine translation system such that the resulting translation properly encodes the underlying sentiment. On the English-Hindi and French-English different domain review datasets, they analyze their utilized technique and discover that it delivers a considerable improvement over a supervised baseline for the sentiment classification and machine translation tasks.

Although the above-mentioned studies illuminate the Quran’s translation and machine translation issues, with regard to sentiment preservation, there are still gaps yet to be filled. First, none of the previous work on the Quran has utilized AI and ML techniques, not to mention TLMs, but resorted to manual qualitative analysis. Second, because they rely on manual qualitative analysis, only a limited number of samples (Quran’s verses) are usually selected and analyzed, not the whole holy Quran. Third, the sole focus of previous studies is the transfer of semantics, not sentiment preservation, in the Quran. Forth, even with studies concerning machine translation issues using ML classification approaches, they have not adopted TLMs despite their superiority in various AI, ML and NLP tasks. These gaps are all addressed by the work presented in this paper.

Research Objectives

As highlighted above, this study aims to address the existing gap in the literature by employing advanced AI technologies to analyze the preservation of sentiment in seven English translations of the Quran. The specific objectives of this research are as follows:

-

Creation of a Parallel Dataset: Develop and publish a parallel dataset incorporating the original Arabic Quran and its seven English translations, facilitating comparative sentiment analysis.

-

Development of a Hybrid Sentiment Analysis System: Design and implement a hybrid system combining TLMs and human validation to annotate sentiment in the Quran accurately.

-

Assessment of Sentiment Preservation: Evaluate the degree to which the sentiment of the original Arabic Quran are preserved in its English translations, focusing on differences in sentiment distribution and agreement levels among translations.

-

Exploration of Translation Challenges: Investigate the challenges faced by translators in preserving sentiment, especially in translating classical Arabic, and assess the effectiveness of English translations in conveying the sentiment of the original text.

By achieving these objectives, this study seeks to answer the following questions:

-

Does the non-Arabic speaking reader perceive the sentiment of the Quran in the same way as an Arabic reader?

-

To what extent do the English translations of the Quran preserve the sentiment of the original divine text?

-

Can AI technologies effectively contribute to the analysis of sentiment preservation in Quran translations?

This research will provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of English translations of the Quran in conveying the original sentiment and explore the potential of AI technologies in assessing sentiment preservation in sacred texts.

Methodology Overview

This section summarizes the methodology used in this study to determine the degree of sentiment preservation of the Quran after translation.

The central idea is to identify the sentiment of each verse in each Quran version, original or translated, and then assess whether the translation agrees with the original in terms of sentiment. Two preliminary steps are taken to accomplish this. The first is to create a parallel dataset for the Quran (Arabic) and its translations, while the second is to determine the sentiment of each verse.

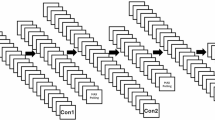

The parallel dataset is constructed from multiple sources (further details are available in Section “Parallel dataset”) and includes one verse per record for each translation as well as the original Arabic version. As shown in Fig. 1, this dataset is used to obtain and validate the sentiment of verses using a hybrid validation system based on both TLMs and human annotations. During this phase, eight different TLMs are used. The validation phase will be based on the outputs of these TLMs. Each TLM produces two elements, namely the predicted label and the score attributed to this prediction. The score is a probability between 0 and 1.

After obtaining the final set of sentiment for each translation, the last step is to assess the concordance sentiment with the original version. This is accomplished through a series of validation processes that are detailed in Section “Sentiment validation process”.

Data

Available translations

This paper targets English translations with ready-to-process digitized versions; seven English translations were obtained through a web scraping process, as described in Section “Parallel dataset”. The following paragraphs introduce each translation by presenting its name, author, and some key characteristics.

The Meaning of the Glorious Koran (Pickthall 1953). First published in 1930 by Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall. It is the first translation done by a Muslim whose mother tongue is English. Pickthall was born into an Anglican family and converted to Islam when he was 42. It is considered that his work adheres to the original and does not contain any dogmatic interpolations.

The Holy Quran, Text, Translation and Commentary (Ali 2001). It is the work of Abdullah Yusuf Ali, a British-Indian barrister born in India in 1872. The translation first appeared in 1934. According to Pickthall, it was “in better English than any previous English translation by an Indian.”, Nevertheless, he issued some comments regarding his translation style as he was opposed to “conveying the meaning of the sacred text in his own words”. Yusuf Ali’s translation is one of the most widely used translations in the world. Part of the reason for this is that it was recognized as an official translation by the Saudi Arabian government in 1990.

Interpretation of the Meanings of the Noble Quran (al Hilali and Khan 1998). Originally published in 1977, this translation is one of the most widely used and was co-authored by Muhammad Taqiuddin al-Hilali and Muhammad Muhsin Khan, and is, as they describe it, presenting “the meanings of the Quran as they knew them”. It is written in accessible English and endorses an important number of explanations, especially regarding the Islamic creed (‘Aquidah). In the rest of this paper, this translation will be referred to as Muhsin Khan.

The Holy Quran (Saheeh International) (International 1997). It was coauthored by three women who converted to Islam and based on Muhsin Khan’s translation. In addition to improving the linguistic style, the parentheses used in the initial version have been moved to the footnotes.

The Quran (Shakir) (Shakir 1999). The authorship of this translation is in doubt, despite its popularity among Shi’a Muslims. Originally published in 1968 by M. H. Shakir and is generally attributed to him, even if the initial author is said to be Mohammed Ali Esmail Habib Shakir. In his review (Clay 2009), Clay Smith notes that Shakir’s translation is heavily influenced by Muhammad Ali’s (Muhammad Ali 1917) translation.

The Holy Quran, The Arabic Text and English Translation (Sarwar 1981). Originally published in 1981 by Shi’a Muslim scholar Muhammad Sarwar, who studied at the Islamic Seminary of Najaf, Iran. It can be seen as an explanation that paraphrases the meaning of the verses.

The Koran Interpreted (Arberry 1996). Published in 1955 by Arthur John Arberry. The author qualifies his work as an interpretation of the Quran rather than a translation, agreeing with Pikthal’s view that the Quran is untranslatable. Arberry says in his preface: “the rhetoric and rhythm of the Arabic of the Koran are so characteristic, so powerful, so highly emotive, that any version whatsoever is bound in the nature of things to be but a poor copy of the glittering splendour of the original”. Arberry was born in Portsmouth, England, in 1905 and is the first non-Muslim Arabic scholar to translate the meanings of the Quran into English.

The seven translations were selected based on their availability in a digital format ready for processing. Further, they are the most widely used translations, and their study can indicate how well sentiment is preserved in English translations in general. In addition to that, they make various typologies according to authors’ nationalities, religions, and translation styles.

Parallel dataset

All versions, whether Arabic or translated, had to follow the same structure in order to build a sentiment analysis dataset. Each chapter (Surah) and verse number were included in the parallel dataset to ensure its validity, along with the verse text. The proposed dataset is publicly availableFootnote 3.

The Arabic Quran is downloaded in Comma Separated Values (CSV) format from a MendeleyFootnote 4 repository and checked the content according to Chapters and Verses. The English translations are obtained through a scraping step on the Corpus Quran websiteFootnote 5, which displays, for each verse, the English equivalent from the seven translations.

It is important to note that the English dataset includes not only the direct translations of the verses but also any explanatory notes that accompany these translations on the Corpus Quran website. These notes are integrated into the verse translations and are therefore considered part of the English text as it is typically presented to readers.

The next step was to verify that the datasets obtained for the Arabic version or translations each contained the same number of chapters and verses. There are 6236 verses in all datasets, covering 114 chapters, and each record pertains to one verse. After that, the various datasets are merged using chapter numbers and verse numbers as key features.

Dataset statistics

WordClouds provide the capability to compare translations with the original version, offering a comprehensive overview of their content. Figure 2 shows that the most frequent words in the Quran are  Allah (Allh), “name of God in Islam”,

Allah (Allh), “name of God in Islam”,  Earth (Al

Earth (Al rD),

rD),  Say or Tell (ql),

Say or Tell (ql),  Your Lord (rab uka),

Your Lord (rab uka),  Disbelieved (kfrwA),

Disbelieved (kfrwA),  People (AlnAs),

People (AlnAs),  Truth (AlHq).

Truth (AlHq).

The same words appear in the translations, with some differences, as shown in Fig. 3. Sarwar and Arberry use the term “God” instead of Allah, which is one of God’s names, not an equivalent of God.

Additionally, Sahih International, Pickthall, and Mohsin Khan use the word “disbeliever”, while the other translators use “unbeliever”. Furthermore, in Mohsin Khan’s translation, there is a preponderance of the words “Muhammad SAW”, meaning Muhammad (the prophet), Peace Be Upon Him (PBUH) and “Islamic Monotheism”, for example. These elements do not form an integral part of the Quran; however, they serve to validate and signify that the present translation incorporates numerous explanatory notes enclosed within brackets within the verses. It is noteworthy that these elucidations bear a pronounced correlation with the tenets of the Islamic creed (’Aqidah).

For both character and word count (Table 1), each translation requires at least twice the number to convey the meaning conveyed in the Quran. A verse in Mohsin Khan’s translation contains 177 characters on average, compared to 66 in the Quran and 135 in the other translations. As mentioned above, the translators of this translation have provided explanations within the verses themselves. Table 1 present the statistics of the different versions with and without explanations. These latter are additions incorporated by the translators to clarify the meaning of the verse or passage in question. Leaving out the explanations decreases the total number of words by 15% for Mohsin Khan but not by more than 3% for the other English translations. Shakir’s and Arberry’s translations contain the fewest explanations, only 0.89 and 0.23 per cent, respectively.

Experiments

Sentiment processing

There are two steps to uncovering the sentiment of each verse. The first step involves using pre-trained sentiment analysis models, and the second involves validating the predicted sentiment. Detailed explanations of these two steps can be found in the following two sections.

Models

HuggingFaceFootnote 6 model hub is employed to identify models aligning with the study’s objectives. A target language is specified (Arabic or English) while using the “Text classification” filter as well as a keyword related to sentiment analysis such as “Sentiment” or “SA”. Models categorizing sentiment into Neutral, Negative, and Positive categories, are retained. Conversely, models incorporating alternative categories, such as star ratings for reviews, are excluded. Models with performance scores specified at acceptable levels are retained, and others are verified by submitting obvious positive or negative sentences; those that fail to correctly predict the sentences are not retained.

The CAMeLBERT models were selected for Arabic sentiment analysis due to their comprehensive training on diverse Arabic corpora, including classical Arabic texts analogous to the Quran. These models include CAMeLBERT-MSA-SA, trained on Modern Standard Arabic texts; CAMeLBERT-CA-SA, which is trained on Classical Arabic texts closely aligning with the linguistic style of the Quran; CAMeLBERT-Mix-SA, which incorporates a blend of Modern Standard and Classical Arabic texts; and Arabic-MARBERT-Sentiment, which is trained on a broad spectrum of Arabic texts suitable for general sentiment analysis tasks. The performance of the CAMeLBERT models ranges between 72% and 93% in terms of micro F1 scores (Inoue et al. 2021), while MARBERT achieved a notable F1 score of 75% in sentiment analysis (Alotaibi et al. 2023).

For English sentiment analysis, models were selected based on their high performance on established sentiment analysis benchmarks. Sentiment Analysis DistillBERTa, a distilled version of BERT, is optimized specifically for sentiment tasks and has demonstrated robust performance with a Macro F1 score of 80%Footnote 7, making it a reliable model for capturing nuanced sentiment in English texts. Tweet Sentiment Eval, a RoBERTa-based model fine-tuned for sentiment analysis, has shown acceptable and consistent results through extensive manual testing, despite the lack of formal benchmark documentation. Sentiment Roberta Large English 3 Classes, a large-scale RoBERTa model, classifies sentiment into three categories–Positive, Neutral, and Negative–and has achieved an impressive hold-out accuracy score of 86.1% (Hartmann et al. 2021), reflecting its effectiveness in various English language contexts. Bertweet Base Sentiment Analysis, a RoBERTa-Base model fine-tuned for tweet sentiment analysis, has also demonstrated strong performance with a Macro F1 score of 72% (Pérez et al. 2021), effectively handling the challenges posed by brief, context-rich tweets.

All the selected models are TLMs, with the majority being BERT-based models. Model types and characteristics are shown in Table 2 for each language. The accuracy of these models on sentiment analysis benchmarks in their respective languages was a crucial factor in their selection. For example, the CAMeLBERT models have demonstrated strong performance on Arabic sentiment analysis tasks, while the selected English models are among the top performers in various sentiment analysis competitions and benchmarks.

After selecting models, they are evaluated for each verse to determine the predicted sentiment and prediction score. As a result, Arabic and English have four predictions per verse. Predictions are not directly used for sentiment analysis but rather are validated through a process described next.

Sentiment validation process

Arabic

The validation process is primarily based on the CAMeLBERT-CA model trained on classical Arabic content since the Quran is written in classical Arabic. Therefore, this model is considered a priority in the validation process, as illustrated in Fig. 4. This hybrid process involves checking the models’ results before sending invalidated cases to annotators for human validation, as shown in Algorithm 1.

Human Verification

The first phase, based on model predictions, concluded with the validation of 89% of the verses, meaning that 89% of the model’s predictions were accepted without requiring further human validation. The remaining 11% (705 verses) were transferred to the human validation phase. This human validation was carried out in three steps (see Fig. 5):

Step 1:

-

The 705 verses are divided into five subparts of 141 verses each.

-

Two annotators are assigned to each subpart, resulting in a total of 10 annotators.

-

In each subpart, annotations for which both annotators assign the same label are retained.

As a result of this step, 436 verses (62%) were validated.

Step 2:

-

To ensure better validation of the two annotations from Step 1, a third annotation is added. As a matter of fact, the remaining 269 verses have been divided into two subparts for annotation by the authors.

-

222 verses are retained based on the majority votes of the three annotations.

Step 3:

Finally, the two authors discussed their decisions and agreed on final annotations for the 47 verses that did not receive a majority vote.

As part of this stage of human validation, the annotators, whose mother language is Arabic and who are fluent in reading the Quran as well as proficient in both Arabic and English, were given label assignment instructions. Each annotator completed a Google Form that displayed three categories of annotations for each verse. Each of these three categories has been thoroughly explained. Following is an approximate translation of the Arabic text submitted to the annotators:

Category 1

A verse that encourages or shows mercy, or that speaks of heaven and bliss, or that inspires joy and enthusiasm in the soul (even if it has nothing to do with heaven or bliss). This is the equivalent of the Positive label.

Category 2

A verse that contains threats, punishment, torment, or mention of Hell’s fire or any other topic that causes the soul to contract (even if it is not about fire or torment). Category 2 corresponds to the Negative label.

Category 3

A verse that is neither encouraging nor intimidating and falls into neither of the first or second categories. This is considered the Neutral Label.

The annotation instructions avoided using the labels “Positive”, “Neutral”, and “Negative” to avoid offending the annotators. This is because a religious text in general, and particularly the Quran, which is considered the word of God, cannot be perceived as “Negative” by Muslims, for example. This study, however, keeps these labels as they are relevant to the NLP sentiment analysis field.

English

The English translations were validated by a majority vote. The first step is to keep the label predicted by the majority of models (hard voting). If there is no majority label, then the label with the highest average prediction score (Soft voting) is assigned, as shown in Algorithm 2.

The validation of English translations using a majority vote approach may be influenced by performance discrepancies among sentiment analysis models. To assess potential bias and evaluate the robustness of sentiment classification, a sensitivity analysis was conducted on the Sahih International translation. This analysis involved testing 25 different weighting scenarios for the four models used in sentiment prediction.

Algorithm 1

Arabic Prediction Validation

Input: V = {v1, v2, …, v6236} Verses ensemble

Output: \(P=\{{P}_{{v}_{1}},{P}_{{v}_{2}},\ldots ,{P}_{{v}_{6236}}\}\) Predictions ensemble

M = {m1, m2, m3, m4}: Models ensemble, m1 is CAMeLBERT-CA

Pv,m: Hard prediction of model m for verse v

Sv,m: Soft prediction’s score of model m for verse v

MajorityVote: Label predicted by the majority of models (3 models)

HighestAverageScore() : Calculates average score per label and returns the highest average score

1: for vi ∈ Vdo

2: for mi ∈ Mdo

3: Get prediction and score \(\{{P}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{i}};{S}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{i}}\}\)

4: if ∃ MajorityVote then

5: if \({P}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{1}}\) == MajorityVote then

6: if \({S}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{1}} > 0.5\) then

7: \({P}_{{v}_{i}}\leftarrow {P}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{1}}\)

8: else

9: HumanVerification()

10: else

11: if \({S}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{1}} > 0.7\) then

12: \({P}_{{v}_{i}}\leftarrow {P}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{1}}\)

13: else

14: HumanVerification()

15: else

16: if \({P}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{1}}==Argmax(HighestAverageScore())\) then

17: \({P}_{{v}_{i}}\leftarrow {P}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{1}}\)

18: else

19: if \({S}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{1}} > 0.5\) then

20: \({P}_{{v}_{i}}\leftarrow {P}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{1}}\)

21: else

22: HumanVerification()

Algorithm 2

English Prediction Validation

Input: V = {v1, v2, …, v6236} Verses ensemble

Output: \(P=\{{P}_{{v}_{1}},{P}_{{v}_{2}},\ldots ,{P}_{{v}_{6236}}\}\) Predictions ensemble

M = {m1, m2, m3, m4}: Models ensemble

Pv,m: Hard prediction of model m for verse v

Sv,m: Soft prediction’s score of model m for verse v

MajorityVote: Label predicted by the majority of models (3 models)

LabelHighestAverageScore() : Calculates average score per label and returns the label with highest average score

1: for vi ∈ V do

2: for mi ∈ M do

3: Get prediction and score \(\{{P}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{i}};{S}_{{v}_{i},{m}_{i}}\}\)

4: if ∃ MajorityVote then

5: \({P}_{{v}_{i}}\leftarrow MajorityVote\)

6: else

7: \({P}_{{v}_{i}}\leftarrow LabelHighestAverageScore()\)

The analysis aimed to determine the impact of varying model weightings on sentiment classification. In each scenario, different weights were assigned to the models’ predictions, reflecting diverse assumptions about their relative accuracy. A weighted majority vote was then calculated for each scenario, where the sentiment label with the highest weighted score was selected as the final classification.

To quantify the variability in sentiment predictions across scenarios, the Gini Index and Entropy were employed:

-

Gini Index: measures inequality in label distribution, with a lower value indicating minimal variability.

-

Entropy: assesses the randomness in label distribution, with lower entropy suggesting consistency in predictions.

The sensitivity analysis yielded a mean Gini Index of 0.1 and a mean Entropy of 0.23. These low values indicate minimal variability and high consistency in sentiment labels across different weighting scenarios. The results confirm that the majority vote validation method is robust, with the final classifications remaining stable and unbiased despite variations in model performance.

Evaluation method

Although the main objective is to quantify the agreement between the detected sentiment for the Quran in Arabic and the translations, this work also assesses the agreement between each pair of English translations as well as the overall agreement between all English translations. To do this, measures of inter-rater reliability are used.

A variety of statistical techniques can be used to assess inter-rater reliability. Despite this, the most commonly used metrics are Cohen’s Kappa (Landis and Koch 1977), Fleiss’ Kappa (Fleiss et al. 2013), and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). This section defines each of the three metrics before presenting and debating the best metric for the problem at hand.

Cohen’s Kappa: is a statistical index used to measure the degree of agreement between two raters or two methods of evaluating how to categorize individuals or objects into a number of categories defining the terms of a nominal variable. This coefficient represents the proportion of elements classified the same way by both raters. As opposed to the simple calculation of an agreement proportion, it incorporates a correction that considers the fact that a certain amount of agreement can be attributed to chance alone. The Kappa coefficient is calculated by applying the following formula:

Where:

-

P(A): is the proportion of agreement between raters, i.e., the number of items on which the raters gave the same category divided by the total number of items.

-

P(C): is the proportion of agreement due to chance, i.e., the proportion of cases for which agreement is expected purely by chance. It is calculated based on the marginal probabilities of each rater’s category assignments.

Kappa coefficients can have negative values for totally unmatched annotations and a maximum value of 1 for totally matched annotations. Table 3 presents the interpretation of the Kappa scores proposed by Landis and Koch and adapted for this work.

Fleiss Kappa: Joseph L. Fleiss introduced this coefficient in the 1980s for application when there are more than two raters. This coefficient takes values between -1 and +1, and the interpretation is similar to Cohen’s Kappa. However, this interpretation is questioned because the values also depend on the number of categories. In addition, some conditions must be met in order to use this index. Only one is intrinsically related to the present study, namely the need for a large sample size of annotators and that different samples be used for each annotated observation. As mentioned by Fleiss et al.: “The raters responsible for rating one subject are not assumed to be the same as those responsible for rating another”. Taking the current study as an example, this condition requires the use of a different sample of annotators (sentiment analysis models) for each verse. Since the number of annotating models to annotate all the verses is fixed, this condition is not satisfied. In contrast, the Kappa coefficient does not require this condition since it involves two fixed annotators.

Intra Class Correlation (ICC): measures the strength of inter-rater agreement when a continuous or ordinal rating scale is used. Like Fleiss Kappa, it is suitable for two or more raters. Although it does not require the limiting Fleiss assumption about the sampled raters, it cannot be used for this study since it concerns only continuous values or ordinal categories. Although nominal, our categories (neutral, positive, and negative) are not ordinal.

Considering the conditions of applicability of each metric and the nature of the problem, this paper adopts Cohen’s Kappa coefficient. In addition to comparing different pairs of translations, English translations are evaluated as a whole by taking the arithmetic mean of their pairs’ Kappa scores.

Results and Discussion

The sentiment distribution illustrated in Table 4 and Fig. 6 reveals that the translations generally mirror the structural pattern observed in the original Arabic Quran. The sentiment analysis consistently shows a predominance of neutral sentiment, followed by negative and then positive. The proportion of neutral sentiment spans from 59% to 74% in the English translations, while it constitutes 66% in the Arabic original. Notably, Muhammad Sarwar’s translation exhibits a higher percentage of negative sentiment (25%) compared to the Arabic version (24%), whereas other translations range from 14% to 17%. Additionally, Muhammad Sarwar’s translation also shows a higher proportion of positive sentiment (16%), contrasting with the other English translations and the original version, which are around 11%.

The inter-agreement analysis of the English translations, visualized in Fig. 7 through Kappa scores, indicates that only the Mohsin Khan and Sahih International translations achieve a “Good” level of agreement with a score of 0.62. This strong agreement aligns with the fact that Sahih International is derived from Mohsin Khan’s translation. The remaining translation pairs exhibit a “Moderate” level of agreement, with scores ranging from 0.47 (Muhammad Sarwar-Arberry) to 0.6 (Shakir-Sahih International and Yusuf Ali-Mohsin Khan). The average Kappa score across all English translations is 0.5, signifying a moderate level of inter-agreement.

While the inter-English agreement generally reaches “Moderate” or “Good” levels, the agreement between these translations and the Arabic Quran, as depicted in Fig. 8, presents a different picture. None of the translations attain “Moderate” or “Good” levels of agreement when compared to the original text. Only four translations–Pickthall, Shakir, Muhammad Sarwar, and Mohsin Khan–achieve “Fair” scores, with an approximate Kappa score of 0.21. The detailed Kappa scores for each translation’s agreement with the Arabic version are presented in Table 5. It is interesting to note that although Sahih International aims to refine the style of Mohsin Khan’s translation, this refinement does not appear to extend to sentiment preservation. Mohsin Khan’s translation exhibits a slightly higher Kappa score in comparison.

These results suggest that the studied English translations may not evoke the same emotional responses or sentiments in English-speaking readers as the Arabic Quran does for Arabic speakers. This observation underscores the inherent challenges in effectively translating the Arabic language, especially the classical Arabic employed in the Quran. The translators often resort to using lengthier expressions, as evidenced by the increased word count in the translations compared to the original, highlighting the complexities involved in capturing the nuances of the source text.

In summary, the sentiment analysis conducted in this study reveals intriguing patterns in sentiment distribution and agreement across different English translations of the Quran. While the translations demonstrate moderate agreement among themselves, their concordance with the original Arabic text in terms of sentiment remains relatively low. This discrepancy emphasizes the difficulties inherent in translating not only the semantic meaning but also the emotional depth embedded within sacred texts. The study calls for further research into developing more sophisticated sentiment analysis models and translation approaches that can better capture and preserve the multifaceted nature of sentiment in translated religious texts.

Error Analysis

This section examines the discrepancies in sentiment between the original Arabic verses and their English translations. Through a series of examples, we analyze why some translations align with the true sentiment while others diverge.

Example 1

Verse (2:12)  [Negative].

[Negative].

-

Yusuf Ali: “Of a surety, they are the ones who make mischief, but they realise (it) not.” [Neutral]

-

Sahih International: “Unquestionably, it is they who are the corrupters, but they perceive [it] not.” [Negative]

-

Muhammad Sarwar: “They, certainly, are corrupt but do not realize it.” [Negative]

The term  (al-mufsidun) in the original Arabic verse refers to individuals who engage in actions that cause significant harm and disorder, carrying a clear negative connotation that emphasizes the seriousness of their wrongdoing. This sentiment of condemnation is somewhat diluted in Yusuf Ali’s translation, where the word “mischief” is used, a term that in contemporary English often suggests minor wrongdoing with playful or non-malicious intent. As a result, the translation portrays a neutral sentiment, which does not fully capture the gravity of the corruption implied by

(al-mufsidun) in the original Arabic verse refers to individuals who engage in actions that cause significant harm and disorder, carrying a clear negative connotation that emphasizes the seriousness of their wrongdoing. This sentiment of condemnation is somewhat diluted in Yusuf Ali’s translation, where the word “mischief” is used, a term that in contemporary English often suggests minor wrongdoing with playful or non-malicious intent. As a result, the translation portrays a neutral sentiment, which does not fully capture the gravity of the corruption implied by  . In contrast, the Sahih International translation uses the term “corrupters,” which aligns more closely with the original meaning and conveys a strong negative sentiment, emphasizing the seriousness of the wrongdoing. Similarly, the Muhammad Sarwar translation uses the word “corrupt,” a term that accurately reflects the severe wrongdoing and moral decay implied in the original verse, further reinforced by the word “certainly.” Both the Sahih International and Muhammad Sarwar translations effectively preserve the negative sentiment of the original Arabic, whereas Yusuf Ali’s choice of wording results in a less negative interpretation.

. In contrast, the Sahih International translation uses the term “corrupters,” which aligns more closely with the original meaning and conveys a strong negative sentiment, emphasizing the seriousness of the wrongdoing. Similarly, the Muhammad Sarwar translation uses the word “corrupt,” a term that accurately reflects the severe wrongdoing and moral decay implied in the original verse, further reinforced by the word “certainly.” Both the Sahih International and Muhammad Sarwar translations effectively preserve the negative sentiment of the original Arabic, whereas Yusuf Ali’s choice of wording results in a less negative interpretation.

Example 2

Verse (2:4)

[Positive].

[Positive].

-

Arberry: “who believe in what has been sent down to thee and what has been sent down before thee, and have faith in the Hereafter;” [Neutral]

-

Muhammad Sarwar: “who have faith in what has been revealed to you and others before you and have strong faith in the life hereafter.” [Positive]

The original Arabic verse describes individuals who hold a deep belief in the revelations given to Prophet Muhammad and previous prophets, as well as a firm conviction in the Hereafter. The key phrases  (yu’minun) and

(yu’minun) and  (yuqinun) inherently carry positive connotations, highlighting the qualities of the faithful and emphasizing their strong, unwavering belief, which is viewed positively in Islamic tradition. In Arberry’s translation, the text is presented in a factual manner, using the words “believe” and “have faith” without emphasizing the positive nature of these beliefs. The straightforward, almost clinical approach, results in a neutral sentiment, as the translation focuses more on the informational content than on the positive emotional aspects of belief and faith. In contrast, the Muhammad Sarwar translation conveys a positive sentiment by using the phrase “strong faith,” which adds emotional weight to the verse. The term “strong” enhances the intensity of the sentiment, accurately reflecting the deep and firm conviction implied by

(yuqinun) inherently carry positive connotations, highlighting the qualities of the faithful and emphasizing their strong, unwavering belief, which is viewed positively in Islamic tradition. In Arberry’s translation, the text is presented in a factual manner, using the words “believe” and “have faith” without emphasizing the positive nature of these beliefs. The straightforward, almost clinical approach, results in a neutral sentiment, as the translation focuses more on the informational content than on the positive emotional aspects of belief and faith. In contrast, the Muhammad Sarwar translation conveys a positive sentiment by using the phrase “strong faith,” which adds emotional weight to the verse. The term “strong” enhances the intensity of the sentiment, accurately reflecting the deep and firm conviction implied by  (yuqinun) in the original Arabic. This choice of wording ensures that the translation aligns closely with the positive sentiment of the original verse.

(yuqinun) in the original Arabic. This choice of wording ensures that the translation aligns closely with the positive sentiment of the original verse.

Example 3

Verse (7:190)

[Negative].

[Negative].

-

Muhammad Sarwar: “When they were given a healthy son, they began to love him as much as they loved God. God is too exalted to be loved equally to anything else.” [Positive]

The original Arabic verse describes a situation where a couple, after being blessed with a healthy child, begins to associate others with Allah, attributing the gift they received to other deities or beings. In Islamic theology, this act of “shirk” (associating others with Allah) is considered a grave sin, leading to the verse’s negative sentiment. Muhammad Sarwar translation takes a different approach by introducing the concept of the couple loving the child “as much as they loved God.” This interpretation shifts the focus from the act of shirk to the love for the child, with the phrase “God is too exalted to be loved equally to anything else” framing the issue as one of misplaced love rather than the severe sin of associating partners with Allah. This reframing results in a sentiment that is perceived as positive, as it emphasizes the exaltation of God without condemning the couple’s actions as harshly. By shifting the focus away from the negativity of shirk, the translation leads to a positive sentiment.

Example 4

Verse (3:98)

[Negative].

[Negative].

-

Shakir: “Say: O followers of the Book! why do you disbelieve in the communications of Allah? And Allah is a witness of what you do.” [Neutral]

-

Mohsin Khan: “Say: ’O people of the Scripture (Jews and Christians)! Why do you reject the Ayat of Allah (proofs, evidences, verses, lessons, signs, revelations, etc.) while Allah is Witness to what you do?”’ [Negative]

The Arabic verse serves as a direct rebuke to the “people of the Book” (Jews and Christians) for their disbelief in the signs and communications of Allah, asserting that Allah witnesses their actions and responses to His revelations. The sentiment of the verse is negative due to its accusatory nature and the challenge it poses to the addressees’ disbelief. Shakir’s translation retains the essence of the original verse but presents it in a more neutral tone. Despite using terms like “disbelieve” and “witness,” which align with the negative sentiment of the original text, the overall tone of Shakir’s translation is more factual and less emotionally charged. This neutral sentiment may result from the straightforward phrasing that does not emphasize the confrontational aspect of the original verse. In contrast, Mohssin Khan’s translation conveys the negative sentiment more clearly. By using terms like “reject” and stressing that Allah is a “Witness” to their actions, this translation maintains the accusatory and confrontational nature of the original verse. The focus on rejection and the reminder of Allah’s witness effectively reflect the negative sentiment, aligning well with the tone of the original Arabic text.

Example 5

Verse (37:49)  [Positive].

[Positive].

-

Pickthall: “as they were hidden eggs (of the ostrich).” [Neutral]

The Arabic verse employs the metaphor  (as if they were hidden eggs), suggesting a positive quality of being precious or cherished. The image of hidden or protected eggs often signifies value, care, and purity, leading to a positive sentiment because it implies that the subject is highly valued and safeguarded, emphasizing their beauty or purity. Pickthall’s translation captures the literal comparison of the subject to “hidden eggs of the ostrich`” but does not fully convey the positive sentiment inherent in the original Arabic text. By focusing on the literal description rather than the implied connotations of value and protection, Pickthall’s translation maintains a neutral tone, missing the emotional nuance of the metaphor.

(as if they were hidden eggs), suggesting a positive quality of being precious or cherished. The image of hidden or protected eggs often signifies value, care, and purity, leading to a positive sentiment because it implies that the subject is highly valued and safeguarded, emphasizing their beauty or purity. Pickthall’s translation captures the literal comparison of the subject to “hidden eggs of the ostrich`” but does not fully convey the positive sentiment inherent in the original Arabic text. By focusing on the literal description rather than the implied connotations of value and protection, Pickthall’s translation maintains a neutral tone, missing the emotional nuance of the metaphor.

Example 6

Verse (49:4)

[Negative].

[Negative].

-

Sahih International: “Indeed, those who call you, [O Muhammad], from behind the chambers - most of them do not use reason.” [Neutral]

-

Pickthall: “Lo! those who call thee from behind the private apartments, most of them have no sense.” [Negative]

-

Muhammad Sarwar: “Most of those who call you from behind the private chambers do not have any understanding.” [Negative]

The Arabic verse criticizes those who call out to the Prophet Muhammad from behind private quarters, suggesting they lack understanding or reason  This criticism implies a negative judgment of their behavior and a lack of respect or comprehension, resulting in a negative sentiment. Sahih International’s translation conveys that those calling from behind the chambers “do not use reason,” but the phrasing lacks a strong emotional or accusatory tone, which may contribute to a neutral sentiment. In contrast, Pickthall’s translation describes them as having “no sense,” which captures the negative sentiment by emphasizing a critical judgment of their behavior. Similarly, the Muhammad Sarwar’s translation describes the callers as lacking “understanding,” reflecting the negative sentiment and disapproval present in the original Arabic verse.

This criticism implies a negative judgment of their behavior and a lack of respect or comprehension, resulting in a negative sentiment. Sahih International’s translation conveys that those calling from behind the chambers “do not use reason,” but the phrasing lacks a strong emotional or accusatory tone, which may contribute to a neutral sentiment. In contrast, Pickthall’s translation describes them as having “no sense,” which captures the negative sentiment by emphasizing a critical judgment of their behavior. Similarly, the Muhammad Sarwar’s translation describes the callers as lacking “understanding,” reflecting the negative sentiment and disapproval present in the original Arabic verse.

Example 7

Verse (15:83)  [Negative].

[Negative].

-

Sahih International: “But the shriek seized them at early morning.” [Neutral]

-

Pickthall: “But the (Awful) Cry overtook them at the morning hour,” [Negative]

The verse describes a divine punishment characterized by a devastating cry  that strikes the people early in the morning, leading to their destruction. The term

that strikes the people early in the morning, leading to their destruction. The term  implies a sudden, catastrophic force, signaling overwhelming and fatal divine retribution. Thus, the sentiment is clearly negative, depicting a moment of severe punishment. The Sahih International translation uses “shriek,” which accurately reflects the term but may not fully capture the event’s devastating nature. The absence of descriptive adjectives like “awful” or “terrible” makes the translation more neutral, focusing on the time of the event rather than its severity. In contrast, the Pickthall translation effectively conveys the negative sentiment by describing the event as an “(Awful) Cry,” emphasizing its terrifying and catastrophic quality. The adjective “Awful” and the term “overtook” highlight the event’s intensity and inescapable nature, aligning well with the original sentiment of severe divine punishment.

implies a sudden, catastrophic force, signaling overwhelming and fatal divine retribution. Thus, the sentiment is clearly negative, depicting a moment of severe punishment. The Sahih International translation uses “shriek,” which accurately reflects the term but may not fully capture the event’s devastating nature. The absence of descriptive adjectives like “awful” or “terrible” makes the translation more neutral, focusing on the time of the event rather than its severity. In contrast, the Pickthall translation effectively conveys the negative sentiment by describing the event as an “(Awful) Cry,” emphasizing its terrifying and catastrophic quality. The adjective “Awful” and the term “overtook” highlight the event’s intensity and inescapable nature, aligning well with the original sentiment of severe divine punishment.

The analysis of these examples shows that differences in sentiment between original texts and their translations often arise from subtle choices in wording, emphasis, and how metaphors or culturally specific language are interpreted. Translators face the challenge of not only conveying the literal meaning but also capturing the emotional and cultural nuances of the original text, which can sometimes unintentionally change the intended sentiment. This highlights the need for a thorough study that looks at a wide range of verses and systematically examines the various factors contributing to these sentiment differences. The findings from such research could help improve translation methods, making future translations more faithful to the original text’s emotional and cultural impact.

Conclusion

Muslims believe that the Quran is God’s word and the basis of all jurisprudence. According to Islamic belief, it was revealed in Arabic. In order to communicate God’s message to non-Arabic speakers, this manuscript has been translated into several languages. There has been extensive study of the fidelity of these translations with respect to the meaning conveyed by these verses but not with respect to the sentiment conveyed by the Quran.

This paper proposes a hybrid method based on TLMs and human validation to study how sentiment is preserved after the translation of the Quran. Seven English translations were considered to create and publish a parallel Arabic-Translation dataset and to evaluate their degree of concordance in terms of sentiment analysis. Even though the English translations agree with one another at an acceptable level, the level of agreement with the Quran remains low and does not reflect the effort put forth to ensure meaning equivalence.

The findings reveal compelling insights, with neutral sentiment ranging from 59% to 74% in English translations compared to 66% in the original Arabic Quran. Negative sentiment in some translations reached 25%, while others ranged from 14% to 17%, closely paralleling the 24% in the Arabic version. Additionally, the agreement analysis among English translations indicates varying degrees of alignment, reaching a Good level (κ = 0.62) or a Moderate level (κ from 0.47 to 0.6). However, compared to the original Arabic Quran, none of the translations achieved high levels of agreement, with only four translations reaching a Fair score (approximately 0.21).

The discrepancies in sentiment preservation observed in this study can be attributed to several factors. First, the intrinsic linguistic differences between Arabic and English, particularly in conveying emotional and moral nuances, pose significant challenges. Arabic, with its rich morphological structure and polysemy, allows for sentiments to be expressed in more nuanced ways, which can be difficult to mirror in English. Second, the cultural and theological significance of certain terms in the Quran often necessitates interpretative translation choices, leading to variations in sentiment. For example, terms associated with divine attributes or moral judgments may carry different connotations in English, influencing the overall sentiment. Lastly, the translators’ subjective interpretations and the intended audience’s expectations play a crucial role in how sentiment is conveyed, sometimes prioritizing accessibility over fidelity to the original sentiment.

These findings underscore the complexities of translating the Quran, particularly its classical Arabic, and highlight the importance of preserving not only the semantic meaning but also the sentiment of sacred texts. This study emphasizes the need for improved sentiment analysis models, potentially incorporating mixed sentiment categories, to more effectively capture sentiment in translation. Future research should focus on developing more sophisticated translation methods, including AI models trained on both semantic and sentiment datasets, to ensure that translations of sacred texts remain faithful to both their content and emotional depth.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Github repository mentioned in Note number 3.

Notes

References

Abdelaal NM (2019) Faithfulness in the translation of the holy Quran: Revisiting the skopos theory. Sage open 9:2158244019873013

Abdul-Mageed M, Elmadany AR, Nagoudi El MB (2020) Arbert & Marbert: deep bidirectional transformers for Arabic. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.01785

Aghai M, Mokhtarnia S (2021) Catford’s translation shifts in translating vocabulary-learning books from english to Persian. Iran J Translation Stud 19:65–80

al H, Muhammad T-D, Khan MM (1998) The noble Qur’an: The english translation of the meanings and commentary. Madinah: King Fahd Complex

AlBadani B, Shi R, Dong J (2022) A novel machine learning approach for sentiment analysis on Twitter incorporating the universal language model fine-tuning and SVM. Appl Syst Innov 5:13

Ali AY (2000) The holy Qur’an. Wordsworth Editions

Ali Y (2001) The Holy Quran: Translation and Commentary. Birmingham, UK: Islamic Vision

Aljabri M, Chrouf SMhdB, Alzahrani NA, Alghamdi L, Alfehaid R, Alqarawi R, Alhuthayfi J, Alduhailan N (2021) Sentiment analysis of arabic tweets regarding distance learning in Saudi arabia during the covid-19 pandemic. Sensors 21:5431

Alotaibi A, Rahman A, Alhaza R, Alkhalifa W, Alhajjaj N, Alharthi A, Abushoumi D, Alqahtani M, Alkhulaifi D (2023) Spam and sentiment detection in arabic tweets using marbert model. Math Model Eng Probl 9:1574–1582

Alqahtani Y, Al-Twairesh N, Alsanad A (2023) Improving sentiment domain adaptation for arabic using an unsupervised self-labeling framework. Inf Process Manag 60:103338

Alturki, Majed Mansour M (2021) The Translation of God’s Names in the Quran: A Descriptive Study. PhD thesis, University of Leeds

Aqad MHAl, Bin Sapar AA, Bin Hussin M, Mohd Mokhtar RA, Mohad AH (2019) The english translation of arabic puns in the holy quran. J Intercultural Commun Res 48:243–256

AR B, Khapra MM, Bhattacharyya P (2013) Lost in translation: viability of machine translation for cross language sentiment analysis. In Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing: 14th International Conference, CICLing 2013, Samos, Greece, March 24-30, 2013, Proceedings, Part II 14, pages 38–49. Springer

Arberry AJ (1996) The Koran interpreted: A translation. Simon and Schuster

Barhoumi A, Aloulou C, Camelin N, Esteve Y, Belguith L (2018) Arabic sentiment analysis: an empirical study of machine translation’s impact. In Language Processing and Knowledge Management International Conference (LPKM2018)

Birjali M, Kasri M, Beni-Hssane A (2021) A comprehensive survey on sentiment analysis: Approaches, challenges and trends. Knowl-Based Syst 226:107134

Blum-Kulka S (1986) Shifts of cohesion and coherence in translation shoshana blum-kulka, hebrew university of jerusalem. Interling intercultural Commun: Discourse cognition translation second Lang Acquis Stud 272:17

Brooks MC, Mutohar A (2018) Islamic school leadership: A conceptual framework. J Educ Adm Hist 50:54–68

Catford JC (1965) A linguistic theory of translation, volume 31. Oxford University Press London

Clay S (2009) English translations of the qurans; (updated 2009.07.17). http://www.claychipsmith.com/English_Translations.htm. Accessed: 2023-09-15

Fan A, Bhosale S, Schwenk H, Ma Z, El-Kishky A, Goyal S, Baines M, Celebi O, Wenzek G, Chaudhary V et al. (2021) Beyond english-centric multilingual machine translation. J Mach Learn Res 22:4839–4886

Farghal M, Bloushi N (2012) Shifts of coherence in quran translation. Sayyab Transl J (STJ) 4:1–18

Farha IA, Magdy W (2021) A comparative study of effective approaches for arabic sentiment analysis. Inf Process Manag 58:102438

Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik M (2013) ChoStatistical methods for rates and proportions. john wiley & sons

Haleem, MA Abdel (2005) The Qur’an. OUP Oxford

Haris MJ, Upreti A, Kurtaran M, Ginter F, Lafond S, Azimi S (2023) Identifying gender bias in blockbuster movies through the lens of machine learning. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:1–8

Hartmann J, Heitmann M, Schamp C, Netzer O (2021) The Power of Brand Selfies. J Market Res 58(6):1159–1177. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222437211037258

Hussein DME-DM (2018) A survey on sentiment analysis challenges. J King Saud Univ-Eng Sci 30:330–338

Inoue G, Alhafni B, Baimukan N, Bouamor H, Habash N (2021) The interplay of variant, size, and task type in arabic pre-trained language models. In: Habash N, Bouamor H, Hajj H, Magdy W, Zaghouani W, Bougares F, Tomeh N, Abu Farha I, Touileb S (eds) Proceedings of the Sixth Arabic Natural Language Processing Workshop. Association for Computational Linguistics, Kyiv, Ukraine (Online) pp 92–104

International S (1997) The Qur'an: Arabic text with corresponding english meanings. Abul Qasim Publishing House Almunatada Alislami

Irving, Thomas B (1992) The Qur’an: the noble reading. Mother Mosque Foundation

Kenton JDM-WC, Toutanova L (2019) Kristina Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of naacL-HLT, volume 1, page 2

Kumari D, Ekbal A, Haque R, Bhattacharyya P, Way A (2021) Reinforced not for sentiment and content preservation in low-resource scenario. Trans Asian Low-Resour Lang Inf Process 20:1–27

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. biometrics, pages 159–174

Lohar P (2020) Machine translation of user-generated content. PhD thesis, Dublin City University. School of Computing. https://books.google.co.ma/books?id=MmKS0AEACAAJ

Lohar P, Afli H, Way A (2017) Maintaining sentiment polarity in translation of user-generated content. Prague Bull Math Linguist 108:73–84

Mehmood S, Ahmad I, Khan MA, Khan F, Whangbo T (2022) Sentiment analysis in social media for competitive environment using content analysis. Computers, Materials & Continua, 71(3)

Muhammad AM (1917) The holy qur-án. Containing the Arabic Text with English Translation and Commentary. Woking, Surrey: The “Islamic Review” Office

Murah (2013) Mohd Zamri Similarity evaluation of english translations of the holy quran. In 2013 Taibah University International Conference on Advances in Information Technology for the Holy Quran and Its Sciences, pages 228–233. IEEE

Nassimi (2008) Daoud MohammadA thematic comparative review of some English translations of the Qur’an. PhD thesis, University of Birmingham

Pal S, Patra BG, Das D, Naskar, Sudip Kumar, Bandyopadhyay S, van Genabith J (2014) How sentiment analysis can help machine translation. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Natural Language Processing, pages 89–94

Pérez JM, Giudici, JC, Luque F (2021) pysentimiento: A python toolkit for sentiment analysis and socialnlp tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.09462

Pickthall MW (1953) The Meaning of the Glorious Koran: An Explanatory Translation by Mohammed Marmaduke Pickthall. New American Library

Pickthall MW et al. (1960) The meaning of the glorious Koran. New American Library

Putra DIA, Yusuf M (2021) Proposing machine learning of tafsir al-quran: In search of objectivity with semantic analysis and natural language processing. IOP Conf Ser: Mater Sci Eng 1098:022101

Rezvani R, Nouraey P (2014) A Comparative Study of Shifts in English Translations of The Quran: A Case Study on “Yusuf” Chapter. Khazar J Humanit Soc Sci 17:70–87. https://doi.org/10.5782/2223-2621.2014.17.1.70

Saadany H, Orasan C (2020) Is it great or terrible? preserving sentiment in neural machine translation of arabic reviews. In: Zitouni I, Abdul-Mageed M, Bouamor H, Bougares F, El-Haj M, Tomeh N, Zaghouani W (eds) Proceedings of the Fifth Arabic Natural Language Processing Workshop. Association for Computational Linguistics, Barcelona, Spain (Online) pp 24–37

Saadany H, Orasan C, Quintana RC, Carmo Fdo, Zilio L (2021) Challenges in translation of emotions in multilingual user-generated content: Twitter as a case study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.10719

Saffarzade T (2001) Translation quran. Tehran: Moassese Farhangi Jahan Yarane Kosar

Sait RW, Ishak MK (2023) Deep learning with natural language processing enabled sentimental analysis on sarcasm classification. Comput Syst Sci Eng 44:2553–2567

Saleh H, Mostafa S, Alharbi A, El-Sappagh S, Alkhalifah T (2022) Heterogeneous ensemble deep learning model for enhanced arabic sentiment analysis. Sensors 22:3707

Sarwar M (1981) The holy Quran: Arabic text and English translation. Elmhurst, NY, USA: Tahrike Tarsile Quran

Sefercioğlu N (2000) World bibliography of translations of the Holy Qur’an in manuscript form. Research Center for Islamic History, Art and Culture, IRCICA

Shakir MH (1999) The Holy Quran Translated. Elmhurst, NY, USA: Tahrike Tarsile Quran

Shakir MH (1985) Holy Quran

Shalunts G, Backfried G, Commeignes N (2016) The impact of machine translation on sentiment analysis. Data Analytics 63:51–56

Sherif SM, Alamoodi AH, Albahri OS, Garfan S, Albahri AS, Deveci M, Baker MR, Kou G (2023) Lexicon annotation in sentiment analysis for dialectal arabic: Systematic review of current trends and future directions. Inf Process Manag 60:103449

Si C, Wu K, Aw A, Kan M-Y (2019) Sentiment aware neural machine translation. In Proceedings of the 6th Workshop on Asian Translation, pages 200–206

Svensson J (2019) Computing qur’ans: a suggestion for a digital humanities approach to the question of interrelations between english qur’an translations. Islam Christ–Muslim Relat 30:211–229

Tabrizi AA, Mahmud R (2013) Issues of coherence analysis on english translations of quran. In 2013 1st International Conference on Communications, Signal Processing, and their Applications (ICCSPA), pages 1–6. IEEE

Wadud MAH, Mridha MF, Shin J, Nur K, Saha AK (2023) Deep-BERT: Transfer Learning for Classifying Multilingual Offensive Texts on Social Media. Computer Syst Sci Eng 44:1775–1791

Wan Y, Yang B, Wong DF, Chao LS, Yao L, Zhang H, Chen B (2022) Challenges of neural machine translation for short texts. Computat Linguist 48:321–342

Yang Y, Liu R, Qian X, Ni J (2023) Performance and perception: machine translation post-editing in chinese-english news translation by novice translators. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:1–8

Yu J, Zhao Q, Xia R (2023) Cross-domain data augmentation with domain-adaptive language modeling for aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 1456–1470

Zhang J, Matsumoto T (2019) Corpus augmentation for neural machine translation with chinese-japanese parallel corpora. Appl Sci 9(10). ISSN 2076-3417. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9102036. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/9/10/2036

Zhang Z, Wu S, Jiang D, Chen G (2021) Bert-jam: Maximizing the utilization of bert for neural machine translation. Neurocomputing 460:84–94

Zhang Z, Wu Y, Hai Z, Li Z, Zhang S, Zhou X, Zhou X (2019) Semantics-aware bert for language understanding. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:202539891

Acknowledgements

The Researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KG undertook data curation, analysis, and experimental activities, while MA participated in experiments and conducted data content analysis and exploration. Additionally, MA played a significant role in elaborating the related work and introduction sections. KG also contributed to the preparation of the related work. MA managed communication with annotators, while KG took charge of preparing and managing annotation forms and outputs. Both authors collaborated on the overall paper revision, engaged in technical discussions, and contributed to the development of the methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gaanoun, K., Alsuhaibani, M. Sentiment preservation in Quran translation with artificial intelligence approach: study in reputable English translation of the Quran. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 222 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04181-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04181-0

This article is cited by

-

Leveraging large language models for detecting and preserving emotions in quran translations

Journal of King Saud University Computer and Information Sciences (2025)