Abstract

In this paper, we discuss the role of culture and creativity as a so far neglected growth factor, filling an important gap in the existing literature. We analyse both the relevant theoretical and empirical studies, and we find that there is a solid basis to integrate culture and creativity into a more comprehensive growth paradigm. Working on the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) database, we adopt a cross-sectional design. We find that cultural and creative sectors are characterised by higher levels of problem solving, numeracy, and literacy skills with respect to other productive sectors, and that the same positive gap holds for cultural and creative jobs with respect to other kinds of jobs. Taking into account the well-documented effects of cultural participation on pro-social attitudes and behavioural changes, we conclude that culture and creativity deserve more attention as a socially sustainable growth factor, simultaneously acting on both the supply and demand sides. Harnessing the skills-building potential of culture and creativity may, therefore, provide the basis for a new cycle of research and policy developments on the soft determinants of growth performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neoclassical economic growth models typically predict that differences in the level of development between countries (but also regions or cities) are likely to decline due to catch-up processes. However, evidence has shown that initial differences do not tend to decline over time but rather amplify (Kerschner, 2010; Mirowski, 2013; Piketty, 2014; Reinert, 2007). Hence, as Reinert (2007) puts it, the crucial question becomes “How rich countries got rich … and why poor countries stay poor”, with a special emphasis on the latter part. A pillar of Reinert’s argument is the need to invest in education and R&D to build a solid domestic skills base that is crucial to secure growth in the long term. Unlike the neoclassical economic vision, such a skills base must be built on site and cannot be acquired through the mobility of factors, including talent. In Reinert’s vision, building growth potential may require reducing mobility and investing in local assets, including knowledge and skills, rather than striving for perfect mobility and trying to outcompete other countries to attract the best skills.

However, the relationship between hard, structural factors such as investment in capital and technologies and soft factors such as talent and skills in determining growth performances is complex. The literature is constellated by a long strand of models that provide alternatives to the neoclassical growth ones. Among them, two long-time classics building on the ‘structural’ vision are the Lewis Dual Sector model (Lewis, 1955) and the Big Push (Ellis, 1961). Both models build upon a simple intuition: in a two-sector economy where one sector is ‘modern’ and the other ‘traditional’, marginal productivity in the latter is much lower whereas the level of employment in the former is too low to unleash the economy’s full growth potential. In such by now textbook explanations, the deep cause of the productivity gap is sought in technology and more generally structural factors, a view that leads to thinking of comparative long-term growth performance in terms of different structural endowments and of conditional convergence to country-specific growth trajectories, a claim which has however received limited empirical corroboration (Nell, 2020).

Failing to understand growth as an essentially structural phenomenon has led to an awareness in the literature that the persistence of developmental gaps might be at least in part related to ‘soft’, intangible factors such as human capital and innovation (Barrutia & Echebarria, 2010; Cantwell, 2006; Reinert, 2007), as in the case of endogenous growth models (Rebelo, 1991; Romer, 1994), and of institutions and their capacity to regulate the functioning of markets, the allocation of resources, and to establish an appropriate enabling environment for innovation itself (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2013). Such increasing complexity in the understanding of long-term growth determinants has culminated in the formulation of a unified growth theory (Galor, 2011), which assumes a long-term historical perspective and explains how growth performances in the modern era are strongly affected by the long-term interaction between demographics and technological progress. Such theory, in particular, highlights how the increasing role of the soft factor par excellence, education, only becomes possible when a certain developmental stage is reached. Such a long-run perspective also explains why developmental gaps may persist and amplify along different growth trajectories (Ashraf et al., 2021).

In this subtle and nuanced integration of structural, soft and historical factors in providing a fully-fledged account of the complexity of growth processes, relatively little attention has been paid to certain soft factors such as culture (EU, 2012; Throsby, 1995, 2001; UNESCO, 2012; Williamson & Mathers, 2010) and creativity (Mangematin, Sapsed, & Schüßler, 2014; Potts, Cunningham, Hartley, & Ormerod, 2008), if not as a (marginal) appendix to the wider categories of human capital or historical social factors. This is mainly because culture and creativity (CC), outside of the specific disciplinary realms of cultural economics, sociology and policy, are often misconceived as ‘fringe’ human abilities that do not matter much for successful environmental adaptation and are mostly related to leisure and entertainment. This is likely one of the reasons why culture has, for instance, been left out of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and is most generally missing among the top priorities of key policy agendas. What is typically disregarded in this narrow-focused picture is the huge role of CC in honing crucial adaptive skills such as pro-social attitudes, welfare-improving behavioural change, and cognitive ability, among others (Fletcher, 2021; Brown, 2022).

Despite this lack of wider recognition, research on the adaptive value of CC in addressing all kinds of major societal challenges is currently blooming in spheres that are acknowledged as key facilitators of growth such as health and wellbeing, social cohesion, and environmental sustainability, among others. However, despite this promising scenario, relatively little attention has been paid so far to a direct analysis of how CC impact growth factors such as skills and productivity, with a few partial exceptions. For instance, Bakhshi et al. (2008) and Potts and Cunningham (2008) have highlighted the innovation spillover potential of CC; Winner et al. (2013) and Hardiman (2019) have stressed their contribution to the building of various aspects of human capital; Guetzkow (2002) and Hasson et al. (2022) have studied their impacts on social cohesion and conflict resolution. All these studies, and several others, shed light on various processes and mechanisms through which CC have positive effects on growth and productivity. However, none of them offers concrete estimates of such effects, whereas, on the other hand, studies that incorporate CC into growth models such as Bucci et al. (2014) lack an empirical basis. What is missing is, therefore, a conceptual framework that clearly links a theoretical account of how CC contributes to growth processes with a clear and consistent evidence that it does. This important gap in the existing literature is the one that we aim at addressing in this paper, by analysing how in CC, as well as in cultural and creative jobs in any productive sector, problem solving, literacy and numeracy skills are better represented than in other productive sectors and in other jobs in any sector. This is, to our knowledge, a new result that builds a bridge between theoretical and empirical arguments on the growth potential of CC and may open new, interesting possibilities for future research and policy experimentation, offering a contribution to making CC more relevant for the economics and policy mainstream.

Another element that may have added to the conceptual confusion and to the overlooking of CC as a major growth asset is the difficulty of providing precise definitions of what is meant by culture and creativity. First of all, the term ‘culture’ is generally associated to the whole socio-anthropological sphere of human symbolic activities in all fields and is therefore hard to recognize as a specific factor beyond the mere dimension of being human. However, ‘culture’ may also relate to the much narrower sphere of ‘the arts’ (Frey and Briviba, 2023), that is specific activities and experiences with an intentional aesthetic purpose which play a crucial adaptive role in human existence (Johnson, 2015).

These two different instances of culture interact in a profound and, so far, not fully understood way; Bortolotti et al. (2024) offer a conceptual foundation to understand their relationship from a neurocognitive viewpoint, explaining how each of them is tailored to respond to a specific human adaptive challenge. Such a neurocognitive perspective will prove particularly useful in the interpretation of our results, as we will see below.

It has already been amply acknowledged that culture, understood as a cumulative corpus of social norms and beliefs, can positively influence local and regional development (Putnam, 1993; Tabellini, 2010). However, such a social fabric of norms and beliefs also feeds upon, and feeds in turn, creative imagination. For instance, social norms inspire stories, and stories inspire social norms, in a complex co-evolution (Gottschall, 2013). Such dynamic relationships, as observed by Jenkins (2000), may unfold in different ways. First, CC can be reflected ‘outwards’ and thus marketed as an attraction factor, which is very often the case for tourist locations. Second, it can be projected ‘inwards’, driving local development by facilitating the emergence of culturally cohesive social and economic networks, with a number of different, and often complex, systemic effects channelled through culturally initiated attitude and behavioural changes. As Cochrane (2006) points out, cultural capital plays a key role in coordinating social behaviours for the pursuit of shared goals. A proper integration of these factors into the general synthesis may provide important insights and improve the understanding of so far insufficiently explored aspects of growth phenomena (Sacco and Segre, 2009).

Moving from these premises, we can specify what we mean by CC for the purposes of the present study. As already remarked, culture and creativity in their more general sense are almost ubiquitous aspects of human activity. However, it is important to consider their narrower meaning in terms of those specific activities whose purpose is the creation of aesthetic novelty and value in its many forms. In this paper, we focus on the skills content of cultural and creative jobs, that is, those jobs that are characteristic of the cultural and creative sectors and that may be created also in other sectors to carry out similar tasks in different productive contexts. Therefore, for the purposes of this paper, we consider CC as the typical output of cultural and creative sectors, namely creative products and services belonging to: visual and performing arts; museums and heritage; publishing, music, cinema, radio-television and video games; fashion, product and architectural design; communication and advertising, and digital multimedia. Cultural and creative jobs such as copywriting and music composition, for instance, exist also outside of the cultural and creative sectors, so what identifies such jobs is not the sector itself but the kind of skills that are deployed and their characteristic output. However, cultural and creative sectors provide a good mapping of the skills and outputs that are linked to such jobs. Different definitions and characterizations of cultural and creative sectors may be adopted by different authors for specific reasons, but such differences are of secondary importance for the conceptual characterization of CC for the purpose of this paper. Therefore, in what follows we will consider CC as the output of cultural and creative sectors, as well as of all the cultural and creative jobs in other sectors. It must be noted, however, that the cultural and creative sectors that we choose here for practical reasons to operationalise the CC concept should not be seen as an exact empirical translation, but simply as a convenient compromise. Not only CC could translate into other sectors of activity that are not represented in our list, and they typically will in specific cultural ad socio-economic contexts, but moreover, and even more importantly, CC is socially relevant also outside the sphere of professional production altogether. Culture and creativity are in particular also represented in the aesthetic expression of non-professionals, with relevant social impacts on a number of different dimensions, but since in the present paper we are mainly interested in the direct role of CC in growth processes, our empirical analysis will specifically focus upon the professional side. It must, however, be observed that, for individuals whose job positions are not classified as cultural and creative, voluntarily engaging with cultural and creative practices in their free, nonprofessional time or in specific educational programmes may be a powerful indirect source of soft skills creation and honing which could in principle yield indirect positive effects on growth (Katz-Buonincontro, 2011; Kim et al., 2021; Mi et al., 2022). However, their measurement at the macroscale might prove challenging.

Highlighting the role of CC in growth processes offers key insights about their social sustainability. Thinking of the cultural dimension of growth in purely socio-anthropological terms leads to a conclusion that cities and countries with a favourable ‘culture’ can manage to grow in a sustainable way, whereas others with an unfavourable ‘culture’ simply cannot, and there is little one can do about it as such cultural factors change slowly and in the very long term. However, there is ample historical evidence of sudden socio-behavioural transitions that are typically accompanied by a flourishing and mass adoption of strong symbolic and aesthetic expressions (music, literature, cinema and so on, e.g., Sommer, 1993). CC, unlike the broader category of socio-anthropological cultural factors, typically enable the socio-behavioural plasticity needed to spark a change at a timescale that is compatible with an adaptive response to major societal challenges such as those typically related to growth, e.g. skills building, improving productivity, favouring the adoption of new ideas, and so on.

Our approach provides a useful conceptual basis to understand the contribution of CC to the social sustainability of growth processes. We show how, due to the peculiar nature of their experiential sphere, and their wide accessibility by individuals from all kinds of socio-economic backgrounds, CC favour the creation and diffusion of skills that are highly instrumental to the support of growth processes. Field research on the effects of exposure to aesthetic stimuli of professionals outside the cultural and creative sphere documents how the improvement of productivity is not limited to CC specialists but may also occur to workers with many different profiles, and in particular to both blue and white collars (Berthoin Antal et al., 2014; Carè et al., 2021). This suggests that the acquisition of CC-related skills with potential relevance for growth is likely beneficial also for workers not engaged in CC jobs. Although this specific result needs further investigation, it paves the way to intriguing routes of future research.

The social sustainability of growth processes is also related to the consolidation of attitudes and behaviours that are favourable to growth, and which builds among other things on effective social incentives and behavioural interventions. Unlike typical behavioural interventions such as nudging, whose ethical legitimacy is at times controversial (Vugt et al., 2020) and which seem in most cases to generate small and quickly fading effects (Szaszi et al., 2022), cultural experiences build upon a deep-seeded emotional and cognitive grammar that has developed over hundreds of thousands of years of bio-behavioural coevolution and are felt by humans as natural and congenital (Puchner, 2023). It is also for this reason that CC can foster attitudinal and behavioural change from mere experience, even when no explicit, purposeful intervention has been envisaged (Xygalatas et al., 2013). This offers another future line of research and policy experimentation that is worth pursuing and, although not explicitly addressed in the empirical analysis of this paper, is largely complementary to our results as cultural and creative jobs are typically associated to characteristic attitudinal and behavioural traits that can be suitably elicited in humans from all socio-cognitive backgrounds (Sommer, 2013; Magsamen and Ross, 2023).

Analysing CC from the perspective of socially sustainable developmental processes can be especially interesting in the context of approaches to growth such as that of Reinert (2007), with his emphasis on the synergistic effects at the root of successful growth trajectories, once one recognizes the role of CC as a systemic activator that establishes a common platform for cross-sectoral innovation (Sacco et al., 2013) and pro-sociality (Meineck, 2018).

In a nutshell, in this paper, we provide new empirical evidence on the relevance of culture and creative sectors for economic development that goes beyond mere economic value creation and highlights the role of CC as a so far overlooked, crucial soft growth factor. In particular, we show that CC provides unique opportunities for skills development due to the peculiar nature of their production environment and processes. As a whole, CC promotes socially sustainable growth through combined effects both on the supply and demand sides, which are typical of cultural and creative sectors but can also spill over to other sectors through their strategic complementarities with the former. Acknowledging the specific and under-recognized growth potential of CC may therefore add a meaningful element to our understanding of sustainable growth and to the design of effective policies.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section “Culture and creativity as a systemic growth factor“ reviews the relevant literature on the contribution of culture and creativity to growth, whereas section “Empirical evidence of the growth potential of cultural and creative sectors” discusses the related empirical evidence. Section “Materials and Methods” introduces the methodology for the empirical analysis, whose results are presented in section “Results“. Section “Discussion: CCS as a key driver for growth” offers a discussion of the results in the context of the conceptual framework previously introduced, and section “Conclusions” concludes.

Culture and creativity as a systemic growth factor

Apart from the level of technological development, the most obvious explanations for the persistence of differences between the richest and poorest economies draw upon historical and cultural factors in the broader sense. However, it is now acknowledged that cultural vibrancy, that is, a high density of cultural activities in the more specific sense of experiences with an explicit aesthetic purpose, may contribute to growth in unexpected ways. Places characterised by densely clustered cultural and creative activities tend to be associated with higher wages and attract more skilled workers (Currid-Halkett, 2009; Bakhshi et al., 2014) but on the other hand, they tend to raise costs of living, as vendors can charge a higher premium for a product or service sold in a context of experiential luxury (Yeoman and McMahon-Beattie, 2006). CC are neither easily reproduced nor generated, but they tend to evolve on a timescale that is far quicker than that of cultural change in a socio-anthropological sense. Consequently, the competitive advantage resulting from the localization of cultural assets may be long-lasting under certain conditions, and this leads to a global race for cultural authenticity and vibrancy as inauthentic or culturally dull places (and their related cultural assets) are generally considered as imperfect and inferior substitutes (Lovell and Bull, 2018). On the other hand, local cultural assets such as heritage may be an important source of product differentiation when properly deployed in the design (and re-design) of iconic products with a strong historical or symbolic identity. These effects are not limited to cultural heritage in the narrowest sense, but also extend to all dimensions of material culture with strong local identity, as in the case of the redesign of classical models like the Fiat 500 and Mini of the 50s and 60s, whose brand identity is inextricably linked to their countries of origin and to the associated lifestyles (Saviolo and Marazza, 2012).

These differences in cultural and creative environments translate also into labour market conditions (Montalto et al., 2012). It is often the case that small differences in labour characteristics and skills make a huge difference in income, depending on context, and cultural and creative sectors provide many examples. For instance, being a software engineer in the high-end entertainment industry may be much more economically rewarding with respect to a job with similar skills demands in the mechatronics field. These differences become even more pronounced if certain cultural and creative products become iconic and turn into masscult when proper marketing strategies are used. Differences in technology used between top and average smartphone models are not sufficient to justify a multi-fold difference in price were it not for the cultural factors (e.g., symbolic allure, prestige), with consequent market premia that are relatively impermeable to competition (Heracleous, 2013), and which translate into the capacity to attract the best talent on the market. However, this is only part of the picture, as most jobs in cultural and creative sectors are not highly paid and often suffer from precariousness (Gill and Pratt, 2008). Therefore, cultural and creative sectors are typically characterised by the ‘Matthew effect’ where a small number of highly successful firms and professionals get the most market benefits whereas a large share of the system performs much worse (e.g., Houssard et al., 2023).

The cultural market premium phenomenon is relevant and visible in all kinds of retail markets, where very often some minor, but catchy and innovative features, allow producers to distinguish their product from the competition, gaining market advantage and being able to charge significantly more, sell more, or even both (Long and Schiffman, 1997), typically through mechanisms such as effective mass customization (Piller and Müller, 2004). Control of highly established symbolic assets may therefore become a pillar of market profitability in a post-scarcity world where consumption is mainly driven by self-expression and identity motives rather than by material needs (Morgan and Townsend, 2022). Such symbolic advantage may provide a basis for a further strengthening of market edge through targeted strategies addressing at the same time technological innovation and innovation of meaning (Benaim, 2018), as it has happened in the global rise of Silicon Valley’s high-tech giants such as Apple or Google (Kaplan, 2017).

These examples of cultural and creative influence on market performance can be better appreciated through the perspective of Kremer’s O-ring theory (Kremer, 1993), which allows not only to explain why cultural factors might be responsible for stable differences in the level of development between countries (regions, cities) but also why it might be difficult to reverse this situation. According to Kremer, production is based upon strongly complementary inputs, and the process of production is characterised by positive assortative matching. Therefore, the outcome is strongly influenced by the weakest link, which in turn results in the grouping of the best employees in one place. Classical examples are Ivy-League US universities that attract many of the most prominent scientists, the best orchestras that can sign the best musicians and even F1 teams who not only employ the best engineers, but also, say, the best wheel-changer mechanics. Working with the best improves one’s abilities to perform better and encourages to be among the best. Yet, not working with the best, reduces chances to become one of the best. Furthermore, even if it happens that one becomes highly productive outside a centre of excellence, there are strong centripetal forces (high productivity areas offer higher wages) that drain the most skilled and talented workers from their original habitats.

Culture and history play complementary roles, attracting the most efficient workers but also, due to the associated environmental amenities, the most affluent tourists. Consequently, the bond resulting from the O-ring theory is hard to break and it does not only explain differences in the level of development but also provides arguments about why it is so hard to reduce such differences. However, this is only part of the story and the lure of the main cultural and creative hubs on global talent follows a less straightforward logic than one might think.

Based upon the above reasoning, one would be led to conclude that culture and creative sectors as specific components of innovation and knowledge economies can provide at least a partial explanation of the reasons why the rich stay rich and set a benchmark for the catch-up of those developing countries which want to leverage upon similar assets. However, it is not always the case that the poor stay poor. Although rare, success stories can be found in this regard, as in the case of South Korea which, from post-WWII up to the present day, has gone through the whole developmental cycle from a severely underdeveloped country to a member of the world economic development elite, and which has also managed to become one of the most successful cultural and creative global powerhouses (Jin, 2016). Inspired by the South Korean example, many culturally under-recognized countries have been now setting ambitious goals in the development and global marketing of their cultural content ecosystems, and the global geography of CC is evolving accordingly (Sacco, 2023). Due to the development of internet and telecommunication technologies, additional opportunities for reaping cultural market premia arise. As people purchase far fewer durable goods (or produce them directly, for example using 3D printers), more salience is given to the ingenuity and appeal of the idea over the material appearance and features. Rifkin (2014) states that “The inherent dynamism of competitive markets is bringing costs so far down that many goods and services are becoming nearly free, abundant, and no longer subject to market forces”. So, it is not in general a problem of production per se, but rather of producing something people are willing to buy because of its unique symbolic and identity features, and of protecting its intellectual property to enjoy exclusive benefits from it. What makes the difference in terms of such production capacities? Certainly, it is a matter of technology and talent, but also, to some extent, of local identity assets that become culturally salient at the national, international, or global level, creating new associations between regional and country brands and cultural market premia (Schamel, 2009).

Looking for still unexploited niches of this kind and tapping into them effectively has become a key feature of business strategy. Sectors with the richer, unexploited niches are also likely the ones toward which the most creative and innovative professionals will migrate, dropping jobs requiring repetitive and routine activities (Bacon, 2015) – a trend that is likely to be dramatically exacerbated by the quick takeover of AI (Holford, 2019). The implications of the O-ring theory might suggest in this context an even further increase in developmental differences, as highly skilled jobs stay in centres of excellence, while the low-skilled are outsourced away (Balland et al., 2020). But as discussed above, if certain features of cultural market premia are related to non-reproducible and non-movable local assets, even relatively small and marginal locations may maintain and cultivate a capacity to retain and even attract specific kinds of skills and talents. Good cases in point are small cities with a strong reputation in the food and wine economy (e.g., Nelson, 2016).

Innovative activities, although associated with considerable rewards when successful, do not yield above market-level profits when failing, that is, when they are not conducive to the development of new ideas and/or of successful products. However, according to large-scale statistical effects, the mere volume of R&D and innovation investment carried out by rich countries will ensure that they are able to defend their innovation leadership if they manage to protect intellectual property from the imitation of newcomers. Following Rifkin (2014), innovative ideas are likely to produce profits because they are likely to operate within the zero marginal cost realm. Therefore, adopting a comprehensive development strategy based upon innovation, while at the same time cultivating creativity and imagination at the micro-scale from the very early phases of the educational cycle, is likely to play out in the new global competitive context of post-scarcity consumption and knowledge-intensive experience economy (UNESCO and World Bank, 2021).

It should be kept in mind, however, that zero marginal costs certainly do not imply zero total costs. It is in general quite the opposite. In most of today’s zero marginal cost businesses, huge initial outlays were required, which would be most often untenable for any entrepreneur. In the US those costs are borne not only by venture capitalists, but also by public investments, with significant differences between Europe and the US (Lerner and Tåg, 2013; Mazzucato, 2013)

The importance of the zero marginal cost economy is heralded by the fact that such zero marginal cost companies, even today, are among those with the biggest market capitalization (e.g., Google, Meta). However, one should not forget that the whole sector is associated with significant risk. Market capitalisation of companies operating at zero marginal cost is rarely based on present revenue and most often on expected future performance. The latter, in turn, is very often either under- or overstated. Although the capitalization of Meta exceeds 1.8 trillion dollars as of February 2025, its profits are roughly 3% of that amount. This kind of business model may be very dependent on market expectations and shifts in confidence. The extreme focus on relatively uncommon examples of companies whose success is based more upon projected revenues than on real market performance (as it happens for most unicorns) can create serious instances of selection bias and of implicit structural fragility even in socio-economically advanced economies (Aldrich and Ruef, 2018). Among many dramatic examples of sudden market capitalization downsizing after major strategic failures one can mention America Online (AOL) and Yahoo!, once internet giants with over $300b. capitalization at the apex of the dot-com bubble of the late 90s, recently sold as a bundle (AOL + Yahoo!) to a venture capital firm for only $5b.

In this volatile and highly capitalised environment, the strategic importance of CC for economic growth could seem negligible, also because most cultural and creative producers are small or micro companies that are typically under-capitalised. But in a sense, due to this lack of capitalisation, the cultural and creative sectors play an interesting role in the overall knowledge economy of innovation and growth. Since most cultural and creative companies cannot rely upon an over-hyped growth through inflated market expectations of future revenues, they need to build upon individual skills and organisational creativity much more than the typical firms. This ensures that the cultural and creative sectors present almost unmatched levels of conceptual flexibility and capacity to connect to, and interact with, the most disparate value chains in the most diverse productive sectors. It is also for these reasons that the importance of CC for economic growth has gained currency (see Cochrane, 2006; Fukuyama, 2001; Throsby, 1995).

Throsby (1995) coined the term “culturally sustainable development”, making a case for a systemic perspective much in line with the one adopted by ecological economics (Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1994; Giampietro and Mayumi, 1997). As a result, we can consider the cultural and economic systems as deeply coupled structurally, to a much larger extent that has been typically assumed. Replicating the importance of natural capital for sustainable growth as discussed by Funtowicz and Ravetz (1986) and Georgescu-Roegen (1975), Throsby (1995) highlights the importance of culture and cultural capital to economic growth and its long-term social sustainability. Rephrasing the concept of natural ecosystems, critical to supporting the real economy, Throsby (1999) asserts that the ‘cultural’ ecosystems underpin the operations in the real economy affecting the way people behave and exercise choice.

Throsby’s (1995) first conceptual formulation of the notion of ‘cultural capital’ mostly reflects an economic logic. He claims that cultural capital, understood as the stock of cultural values embodied by an asset (Throsby, 1999), could exist in two forms, namely, physical and intellectual capital. The former, of tangible nature, includes works of art, buildings, or sites with both cultural significance and economic worth. Such kind of capital has analogies with classical physical capital, made by humans, durable, and with a positive market price. However, unlike physical capital, cultural capital is irreplaceable, and its social value likely exceeds its market value. Intellectual capital instead includes ideas, practices, beliefs, and such works of art as music and literature, existing in the public domain, and transmitted from generation to generation. This kind of capital is related to intellectual capital as introduced by Edvinsson and Malone (1997) in organisational research and successively developed (Edvinsson & Bounfour, 2004; Lin & Edvinsson, 2008, 2010; Seleim & Bontis, 2013; Weziak, 2007).

The relationship between growth and cultural capital has been acknowledged by the literature (Bucci et al., 2014; Bucci & Segre, 2011; Dieckmann, 1996; Maridal, 2013; Petrakis & Kostis, 2013; Williamson & Mathers, 2010; Wu, 2013). It must be remarked, however, that the operational understanding of “cultural capital” is closer to the socio-anthropological interpretation, that is, the more generic definition discussed above, as used e.g. by Putnam (2000; 1993) – with more emphasis on trust, norms and social networks, or as proposed by Bourdieu (1986) – a set of attitudes and beliefs that provide a structure of social status through distinction. As such, it has been adopted in various growth models like Dieckmann (1996), Bucci and Segre (2011), Maridal (2013), Petrakis and Kostis (2013), Tabellini (2010), and Wu (2013). However, very little has been said so far about how CC in the more restrictive sense (i.e., activities with an intentional aesthetic quality) may be an important factor for growth.

Bucci and Segre (2011) observe that, although culture had long been mainly considered as a luxury market, and in particular both a marker and a target of personal wealth and political power, the field of cultural economics has recently taken a turn. As cultural production directly and indirectly generates substantial economic effects, investment in culture may be an important driver of long-term economic growth. Moreover, and even more importantly, given its substantially cross-sectorial role and its deep impact on attitudes and behaviours, culture could be seen as one of the main production factors, alongside labour and physical capital, as defined in Solow’s model (Daly, 1997).

Neglecting this dimension and economising on culture as a fungible social resource, for instance by disregarding heritage conservation, failing to support the intergenerational transmission of intangible heritage (including rare and highly specialised crafts) and cultural content corpora, and failing to invest strategically in cultural infrastructure, not only undermines the functioning of cultural systems, but also compromises important sources of competitive advantage and social sustainability, with net welfare losses at the population level. A similar point is raised by Cochrane (2006) who stresses how cultural capital impacts the way natural resources (our ‘natural capital’) are managed and used. In particular, it wields influence over management objectives, the efficiency of demand and provision of raw materials, environmental and amenity services.

To what extent is this CC’s growth potential, highlighted by many different authors independently, empirically corroborated? And does it basically relate to cultural and creative sectors’ capacity to generate economic value added, or are there more complex factors at play? This is the issue that we are going to address in the following sections.

Empirical evidence of the growth potential of cultural and creative sectors

Cultural and creative sectors (CCS) are one of the fastest growing sectors of the economy in the world and in the European Union (EU) in particular. They account for 6.1% of the global economyFootnote 1 and generate 30 million jobs worldwide, of which 7.8 million jobs in the EU (Eurostat, 2024). Additionally, the CCS generally employ more young people than any other sector.

It must also be noted that, by stimulating the production of new ideas and technologies, contributing to sustainable development and supporting the labour market (because of high labour-intensity), they also create many externalities that spill over onto other productive sectors, or can even establish new, systematic exchanges with apparently unrelated sectors according to the new logic of cultural crossovers as highlighted by the New European Agenda for Culture (EU, 2018). In addition, the CCS are found to be resilient to the economic slowdown that has been observed since 2007. Such resilience is observed in terms of both constantly growing GDP and employment, although such trends have been deeply shaken by the global pandemic crisis (OECD, 2020). However, in the case of unemployment, and independently of the pandemic shock, findings are not so unequivocal. Despite frequently mentioned country-specific information on growing employment in the CCS supported by the Ernst&Young reportFootnote 2, Stumpo and Manchin (2015) have shown that it is an over-generalisation to claim that in the whole EU, employment in the CCS has steadily resisted the economic crisis. Instead, they claim that this is true only in some countries.

Nonetheless, it has been long acknowledged that the CCS have been re-positioning from a trailing to a leading sector of the economy (Potts et al., 2008). Perception of the CCS has changed, too. Although, as already remarked, the sphere of arts and culture is often framed as a frivolous and expensive luxury when it comes to making tough policy choices about social welfare goals, more often than in the past they are now considered both a legitimate (although not enough acknowledged) industrial and policy priority and a potentially innovative workroom for the transformation of modern economies and societies (Mangematin et al., 2014). This is particularly true after the recent launch of the new EIT-KIC Culture & Creativity, the largest and most ambitious programme for the creation of a EU-wide cultural and creative ecosystem, which sits side-by-side with analogous projects previously launched for major policy spheres such as Climate, Digital, Energy, Health, Raw Materials, Food, Manufacturing, and Urban MobilityFootnote 3. This recent recognition of culture as a key growth and competitiveness driver is in line with the opinions of evolutionary economists who have long argued that economic growth stems from the growth of knowledge which, in turn, is found to derive also from the creative arts (Potts, 2011; Pugno, 2024).

The CCS feature several structural specificities that make the understanding of their economic and social impacts difficult to grasp to scholars and analysts working on more conventional economic sectors. They rely on the production of symbolic and aesthetic value (Mangematin et al., 2014), which is often hard to measure by means of established methods (Newport, 2024). On the other hand, the aestheticization of everyday consumption and lifestyle choices (Szmigin, 2006; Venkatesh and Meamber, 2008) pushes companies operating in various production sectors to seek new strategic complementarities with the CCS (Dell’era, 2010), e.g. through the creation of branded cultural foundations (Zorloni, 2016; Grassi et al., 2019), the recruitment of artists for product development (Carè et al., 2021) and communication campaigns (Lee, 2015; Masè and Cedrola, 2017), the sponsorship of high-leverage arts and culture events (Rowley and Williams, 2008) and production of own branded events (Robson, 2015), among others. Moreover, CCS are one of the most important laboratories for the ideation, development and testing of new technologies (UNESCO, 2013) in fields such as man-machine interface (Mara and Lindiger, 2015; Williams, 2017), virtual (Lee et al., 2020) and augmented reality (Challenor and Ma, 2019), and artificial intelligence (Werner, 2020; Tigre Moura and Maw, 2021), to name just a few. Furthermore, cultural and creative professions require the development of a very peculiar and general-purpose set of skills, as well as of very specialised ones, that reflect the high flexibility and adaptability required by the CCS peculiarity such that small and micro firms make up a large share of the whole sectors – an aspect that is particularly remarkable in view of their overall size.

Such complexity of the CCS workforce is hardly encapsulated by simple and apparently all-encompassing definitions such as Florida (2002, 2005)’s creative class. Elements of creativity and cognitive flexibility are almost inevitably present in any kind of profession and skills profile, but is there any specificity that characterises CCS workers and that justifies the increasing complementarity of such sectors with so many different value chains, and in particular the fact that they seem to be able to connect significantly to most other sectors of the economy and with practically all aspects of society (Sacco et al., 2013)? May the quest for creative depth, originality and inventiveness that is typical of CCS practices be considered a distinctive, key factor in successful growth trajectories, as suggested among others by Scott (2000), Bucci and Segre (2011), Bucci et al. (2014), Sleuwaegen and Boiardi (2014)?

The evidence base to provide a satisfactory answer to such questions is still underdeveloped. An interesting line of research and policy development is related to the attempts to expand the traditional STEM (Science-Technology-Engineering-Math) paradigm of education and skills building into the more comprehensive STEAM, where the additional A stands for the Arts (Maeda, 2013; Perignat and Katz-Buonincontro, 2019). The literature shows that building creative and artistic skills may be of great importance even for researchers working in the most technical subfields of science and technology (Smith, 1970; Root-Bernstein et al., 2019).

Such findings seem to reflect labour market trends. As pointed out by Lichtenberg et al. (2008), creativity ranks among the top five skills that US employers believe to be of increasing importance. It should be noted, however, that definitions of creativity differ between educators and employers. Educators claim that “problem solving” best demonstrates creativity, whereas employers rather argue that “problem identification or articulation” is the best evidence of it. In view of such a discrepancy, it is possible that educational systems do not directly match the needs of the labour market in this respect. Nevertheless, the need for enhancing (or at least not thwarting) creativity in the education process has gained importance with recent episodes of major economic instability and the corresponding need to work toward a more flexible and adaptable economic system.

According to the Special Eurobarometer 417- European Area of Skills and Qualifications (European Union, 2014) the presence of learning environments that stimulate students’ creativity and curiosity was pointed out by 39% of the EU citizens [third most important after teacher’s ability to engage and motivate students (65%) and teacher’s expertise or subject knowledge (50%)] as a key aspect of educationFootnote 4. However, such a feature also scores second among those most in need of improvement (41%). Such a vision of the basic importance of creative and artistic skills for highly innovative sectors and related professional profiles has found prestigious testimonials over the years. For instance, Steve Jobs (the cofounder, late chairman, and CEO of Apple Inc.) remarked that “It’s in Apple’s DNA that technology alone is not enough — that it’s technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the result that makes our hearts sing” (Lehrer, 2011).

Therefore, it becomes important to understand to what extent such specificity is found when comparing the skills profile that characterises CCS and more generally cultural and creative professions, and the corresponding skills in other sectors and jobs. If CCS work environments foster the development of skills that are more hardly found in other sectors, and if likewise creative jobs nurture different set of skills than less creative ones, one can conclude that CC are a potential growth driver whose role cannot be generically subsumed into the wider category of knowledge and education, and that their role in growth policies should be better recognized and capitalised upon. This is our research question, that we are now going to address.

Materials and Methods

Data

The Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) has been used as an empirical basis for this study. PIAAC is an international survey that assesses skills of working-age adults surveyed in OECD member countries. By collecting information on how skills are developed, maintained and lost, as well as how they are used at home, in the workplace and in the community or how these skills are related to labour market participation, income, health, as well as social and political engagement, this study enables assessment, monitoring and analysis of the level and distribution of skills among adult populations as well as of the utilisation of skills in different contexts.

The primary objective is to use the collected data to assist countries in developing strategies to enhance such skills. The methodological aspects of PIAAC encompass various elements such as sample design, survey instruments, field-work preparation, data collection, and estimation standards. The study also addresses specific methodological challenges such as the coverage of the migrant population, test-taking engagement in large-scale assessments, and measurement invariance assessments for group comparisons across countries. Adherence to high methodological standards is a prerequisite for participation in PIAAC and for the inclusion of the national data of the respective participating countries in the international dataset. PIAAC surveys individuals aged 16 to 65 who are not institutionalized and reside within the country at the time of data collection. As PIAAC data are officially released data used here as a secondary source for purposes that are consistent with the goals of the original data collection, our analysis does not require ethical review or approval.

The PIAAC standard sampling approach entails a self-weighting design involving individuals (or households in nations lacking person registries). A self-weighting design ensures that each selected individual (or household, in cases of sampling of dwelling units) has an equal chance of being chosen. In countries with extensive geographical coverage, a typical sample design involves a stratified, multistage, clustered area sampling. Conversely, smaller participating countries exhibit less clustering and fewer sampling stages in their sample design. Furthermore, several countries utilize existing lists of households or individuals from national registries or registries administered by municipalities. Full documentation on sample design and instruments used is available in a technical report on PIAAC (OECD, 2019).

Variables

Among the skills measured in PIAAC, key information-processing competencies can be identified (i.e., literacy, numeracy and problem solving in technology-rich environments), as well as the information-processing and generic skills used in the workplace (OECD, 2013).

Regarding information processing competences, three alternative variables were examined. First, numeracy, as defined in PIAAC, refers to the capacity to comprehend, utilize, interpret, and communicate mathematical data and concepts, which are essential for managing various adult life situations. Numeracy encompasses more than just arithmetic skills. It involves a variety of skills and knowledge and requires dealing with multiple representations beyond numbers in texts. Second, literacy has been defined as the ability to understand, evaluate, use, and engage with written texts to participate in society, achieve individual goals, and develop personal knowledge and potential. This definition encompasses a range of cognitive strategies required to appropriately respond to a variety of text formats and types in numerous contexts, including the ability to read digital texts and traditional print-based texts. Third, problem solving in technology-rich environments as measured in PIAAC encapsulates the use of digital technology, communication tools, and networks to procure, examine, communicate, and perform practical tasks. The aim is not to isolate the usage of ICT tools and applications, but rather to assess the ability of adults to employ these tools to effectively access, process, evaluate, and analyse information.

Regarding the use of generic skills at work, two variables were used. First, learning at work which includes activities as the instruction of others, formal and/or informal learning, and staying current with advancements in one’s professional domain (OECD, 2019). Second, readiness to learn at work was defined as an inclination toward acquiring new knowledge, integrating it with existing understanding and life experiences, and actively participating in problem solving and information seeking (Smith et al., 2015).

The PIAAC dataset, apart from skills-related variables, also offers an extensive set of background variables. Among these there are the current and last job industry variables, identified according to the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC rev. 4), and current and last occupation, identified according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ILO, 2012). These variables were instrumental for identification of CCS employees as described in the Methods section.

Methods

Employees in the cultural and creative sectors were identified in two distinct ways. First, following the classification presented by Bakhshi et al. (2013), we identified individuals performing cultural and creative activities (CCA) including: (1) publishing activities: publishing of books, periodicals, software and other publishing activities; (2) motion picture, video and television programme production, sound recording and music publishing activities; (3) programming and broadcasting activities: radio broadcasting, television programming and broadcasting activities; (4) creative arts and entertainment activities. To this end the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) codes were used. Principally we used 4-digit ISIC codes. However, in some countries they were not available and hence 3-, and 2- digits codes were used in such cases. The ISIC codes selected were as follows: 1820, 2341, 3211, 5811, 5813, 5819, 5820, 5911, 5912, 5913, 5920, 592, 60, 601, 6010, 602, 6020, 62, 620, 6201, 6202, 6209, 7111, 73, 731, 7311, 7312, 7320, 74, 740, 7410, 7420, 7430, 9101, 9102, 9103, 90, 900, 9000 (a detailed explanation for the ISIC codes used to identify CCA can be found in an online appendix). Such listing covers a substantial share of the sectors listed in the introduction in our operational definition of CCS.

Second, we identified individuals employed in culture and creative occupations (CCO) as suggested by Bakhshi et al. (2013). To this end the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) codes were used. We selected the following codes: 1134, 2126, 2431, 2432, 3121, 3411–3416, 3421, 3422, 3431–3434, 3543, 5244, 5411, 5421–5424, 8112 (a detailed explanation for the ISCO codes used to identify CCO can be found in an online appendix).

As employees in the cultural and creative sectors, we included both currently employed individuals as well as those whose last job was classified as such either in terms of industry or occupation.

The final set of countries considered in this study included: Czechia, Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Spain, Belgium (Flanders), the United Kingdom, and the Russian Federation. However, in the analysis with respect to occupations, Norway was excluded because information on occupation was not provided. Therefore, our estimates correspond to the average computed for all countries included in the analysis.

The final sample size totalled 3219 CCA workers and 2606 CCO workers. Those individuals were compared to the remainder of the sample which comprised 128,526 and 119,165 individuals, respectively. These relatively small sample sizes of both CCA and CCO individuals result from the fact that the EU population of CCS workers was (and still is) relatively small and accounts for at most 6.5% of the total EU workforce at the time of PIAAC data collection (TERA Consultants, 2014). Basic socio-demographic characteristics of analytical samples are presented in Table 1.

We present only pooled results as country-level estimates would not be reliable. In particular, we compared people working in the CCS to the remaining workers population in terms of key information-processing competencies such as problem-solving, literacy, and numeracy as well as the use of generic skills at work in terms of learning at work and readiness to learn at work. A similar approach was applied for creatively occupied workers, that is, comparisons of average levels of problem-solving, literacy and numeracy as well as learning at work and readiness to learn at work between creatively occupied workers and others were conducted. These variables are constructed from single-item questions according to the PIAAC methodology (OECD, 2013) and available in the PIAAC dataset. Problem-solving, literacy and numeracy are measured on a 0–500 scale, while learning at work and readiness to learn at work, on a 0–4 scale. The complex sample design and psychometric design were applied in the analysis using the repest Stata command (Avvisati and Keslair, 2023). The repest procedure in Stata is a programme designed to estimate statistics using replicate weights, such as balanced repeated replication (brr) weights and jackknife replicate weights. This allows for the accounting of complex survey designs in the estimation of sampling variances. The procedure is particularly useful for data analysis in international skills assessments and is specifically designed to be used with datasets produced by the OECD, such as PISA, PIAAC, and TALIS.

Results

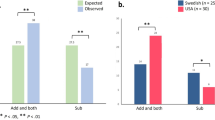

We found that people performing cultural and creative activities, as well as workers with creative occupations, commanded a significantly higher level of all key information-processing competencies assessed in the PIAAC than the remaining worker populations (Table 2). These competencies include problem-solving skills in technology-rich environments – regarded as a proxy of creativity – but also other key skills such as literacy or numeracy. Specifically, people employed in the CCS scored 30.7 points higher in numeracy, 26.6 points higher in literacy, and 25.0 points higher in problem solving compared to people employed in other industries. Similar differences were observed for creatively occupied workers who differed from other employees in numeracy by 13.1 points, in literacy by 14.8 points, and in problem solving by 4.3 points.

Regarding the use of general skills at work, we found that employees from the CCS scored higher in learning at work (difference of 0.10 points on a 0–4 scale) and readiness to learn at work (difference of 0.16 points on a 0–4 scale). Similarly, the differences in these skills were also for culturally and creatively occupied employees compared to others (differences of 0.21 for learning at work and of 0.15 for readiness to learn at work).

What is particularly noteworthy about these data, is the systematic positive difference of CCS workers on all kind of skills at the same time. This result makes a conceptually strong case for a possible causal nexus from the CC environment to skills building – which of course needs to be demonstrated by specifically designed studies. Generally, performance in different types of skills tends to be variable within the same individual: one can have a knack for numerical thinking but less so for literacy, for example. If, however, the overall performance of CCS workers is systematically higher for all skills, and often by a significant margin, this does not likely reflect a lucky pick of a top-tier segment of the workforce with strong polymath inclinations or at least of the top-tier workers in each and every specific skill category, but rather an environmental effect of cultivation of such skills benefiting all workers on average, irrespective of personal inclinations toward specific kinds of skills.

This surprising result might have a clear neurobiological foundation as suggested by Bortolotti et al. (2024). In a predictive coding neurobiological framework which characterizes the brain as a prediction machine set to minimize costly prediction errors, there may be a strong value added in honing the brain’s predictive abilities with respect to challenging prediction contexts characterized by unexpected, atypical environmental circumstances. Cultural and creative activities have an evolutionarily established role of training the brain’s predictive capacities in very unfamiliar and challenging but low-stake situations where prediction errors are not costly as the cultural experience space is constructed to be fictional, imaginary or in any case detached from practical concerns. Such neurocognitive foundations and the related effects apply to all humans engaging with CC, but in the case of CC professionals they have the extra chance of exploiting the neurocognitive boost of cultural and creative experiences in their own working practice. This provides an appealing explanation of why CC environments are so favourable to all kinds of skills building, although more specific studies are needed to further analyse and possibly confirm this specific neurocognitive pathway behind the effects we find in our study.

Discussion: CCS as a key driver for growth

Our results, to the best of our knowledge, are not found in the previous literature. While this is in itself a reason for interest in our results, it also hinders comparison to other studies as to the direction and size of the effects we find. Therefore, more studies should be conducted on comparable databases to assess to what extent the gaps that we find in skills building capacity between CCS and other sectors are replicated or not. As we will mention below, this would be of special importance for countries characterized by different socio-economic and cultural contexts than those included in our panel. A replication in very heterogenous work environments would provide a particularly solid basis to our results, whereas a failure to replicate would probably offer useful clues as to what are the specific factors behind the effects we find in the countries considered in our study.

Our results corroborate the deep-rooted intuition that CCS may provide a unique, and still partly, not properly understood, contribution to an economy’s growth potential and skills base. It has been reflected in the available data, even beyond expectations. Average scores on key general-purpose abilities such as numeracy, literacy, and problem solving are consistently and significantly larger both in CCS with respect to other sectors and in the comparison between culturally occupied workers and other groups of workers. This signals that, indeed, contexts that stimulate creativity and related skills of adaptability and flexibility reflect into the development of general-purpose capacities that enhance performance in all kinds of environments, and not just in creatively-intensive ones. Such effects also apply in the case of workers with cultural and creative occupations in other kinds of sectors. This may suggest that cultural and creative practices may be conducive to exceptional skills development even in environments where such practices are less widespread.

The reverse causality is also, at least theoretically, possible. However, it is difficult to claim that more creative individuals with better numeracy, literacy and problem-solving skills are naturally attracted by CCS and to cultural and creative occupations more generally. As we discussed above, it is true that certain segments of the CCS feature the best talents due to their wage and market premia, but this is far from the norm in cultural and creative sectors as a whole, where occupation is most often precarious and average pay is lower than that available in other sectors (Hesmondhalgh and Baker, 2010; Cunningham, 2014). However, Bakhshi et al. (2014) show that creative workers may enjoy a wage premium in urban settings characterised by dense cultural clustering, which, in accordance with our results, seem to suggest that even the non-profit components of CCS may cause knowledge spillovers into the commercial creative economy.

Therefore, although the presence of selection effects preferentially drawing the most skilled and talented towards CCS cannot be excluded in principle on the basis of our analysis, our results do not strongly support to this hypothesis. The homogeneity of the skills gap between CCS and other sectors across all kinds of skills suggest a more systematic set of factors at work, and we have offered a specific hypothesis of a neurocognitive pathway that could explain our results in view of CC’s key role in honing human predictive ability. Broadening the brain’s predictive skills has proven highly adaptive for humans due to their tendency to colonize a broad spectrum of different environments. Despite that, the role of CC in this regard has been relatively neglected until very recently, increasingly solid neurobiological evidence is emerging, which could explain why CCS jobs seem to boost so dramatically the development of all kinds of productively useful skills. Although we need far more specific evidence and analysis of whether the observed skills gaps can be traced to such neurobiological mechanisms in a compelling way, this provides us at least with a clear hypothesis to test which has a sound logical and bio-evolutionary rationale.

On the macrolevel, our results indicate that although the connection between education and growth has been consistently highlighted as a key developmental factor, the direction of causality is doubtful. Thus, if the sceptics are right that in general the direction of causality is reversed (from prosperity to education and not the other way round), and education’s value does not reside primarily in its intrinsic growth potential but in the capacity of forming better human beings, then the CCS provide the rare exception where the two goals conflate, so that related forms of education have a genuine direct impact on jobs (and perhaps on growth).

Our results explain at least in part why cultural and creative sectors are generally capable of establishing meaningful strategic complementarities with virtually every other productive sector, and why a thriving cultural and creative environment may be a signal of a local economic environment’s overall vibrancy and attractiveness. Therefore, integrating such specificities of CCS into a new generation of growth models may be important to better capture the fine-grained factors that explain differences in growth performance between local systems whose fundamentals might otherwise be basically similar.

On the other hand, these so far overlooked characteristics of cultural and creative work environments in terms of skills building may also contribute to explain the thus far equally overlooked role of passive and especially active cultural participation in achieving social impact goals in the most disparate fields such as mental health and wellbeing (Grossi et al., 2012; Crociata et al., 2014; Weziak-Bialowolska et al., 2018), social cohesion (Hasson et al., 2022), social competencies (Lewandowska and Weziak-Bialowolska, 2022), and environmental sustainability (Crociata et al., 2015; Quaglione et al., 2017; Agovino et al., 2017), among others. If cultural and creative environments are so rich in their skills development potential, it may be expected, as already remarked, that such effects also emerge, at least to some extent, for non-professionals who regularly engage with cultural and creative activities (Di Maggio and Useem, 1980). Such effects are likely to be particularly relevant in the case of active participation where people are directly involved in creative practice rather than enjoying the creative performances of others. Active participation is inherently related to one’s mind stimulation, which, in turn, leads to positive health and well-being effects (Weziak-Bialowolska et al., 2023). Therefore, the growth potential of cultural and creative production might not be limited to the supply side but might also extend to the demand side in that also non-professional engagement, and even mere passive consumption, might be beneficial to a significant extent for skills improvement and for building of assets with considerable developmental value (Cerisola and Panzera, 2022). This would in turn provide a foundation for at least part of the psycho-behavioural pathways that enable cultural and creative crossovers as a possible foundation of a new paradigm of culture-led growth.

There is, however, one additional factor to consider, which is related to the current digitally mediated forms of access to cultural and creative experiences. In pre-digital times, access to the best cultural and creative experiences (and to the related creative talent) was highly conditioned by local availability. Attending the best theatre performances by the best actors, or the best concerts by star musicians, was to a large extent related to living in cities with a vast and diverse offering of cultural and creative productions, and therefore this created a natural advantage for large cities with respect to small centres (Scott, 2001). With the emergence of analogue mass media such as radio and television, such a gap has been already partly reduced and the access to valuable cultural experiences and talents has been significantly extended (Throsby, 2008). However, such access was still largely conditioned by the programming choices of television or radio stations, so that content provision substantially depended on the available palimpsests of broadcasters, with substantial socio-behavioural consequences (e.g., Kang, 1998).

With the advent of digital media and of the internet, high quality material is now not only generally accessible, but also no longer mediated by the programming choices of the content gatekeepers, as all materials are now available on demand, catering to the interests and needs of users. This means that it is now possible to create rich cultural environments and access to the best creative talents even for people residing in less culturally served locations, and this may in turn further amplify the positive skills building effects of CC (Wu et al., 2016). Moreover, similar mechanisms are likely to operate for all other knowledge assets that were strictly localised in pre-digital environments, such as high-quality teaching in best universities and colleges (Bennett and Kent, 2017). And such amplification might be boosted even more by the quick development of immersive digital technologies that replicate (and extend) the affordances that are typical of direct physical access (as well as create new, intrinsically digital ones) also in the context of remote access (Dincelli and Yayla, 2022). The current scenario might therefore make the growth potential of cultural and creative production and activities even more apparent and understandable.

This, however, calls in turn for a substantial reshaping of economic policies to take the specificity of the current labour market into proper account, and once again the cognitive models of cultural and creative agency offer an effective blueprint (Hukkinen, 2020). Creative sectors will be more efficient in attracting highly skilled employees if they are able to propose a sufficiently attractive package of monetary and non-monetary benefits and offer the skills nurturing environment that makes cultural and creative professions so uniquely appealing. Cultural and creative workers do not only respond to price signals but are also primarily interested in working in an environment that offers stimulating professional challenges and are often willing to accept negative wage premia in exchange for a challenging enough creative job that focuses on experimentation and skills development (Stokes, 2021). This is the profound reason why CC have such a potential for skills development: they both attract workers with a strong intrinsic motivation to develop their capacities and provide a learning environment where quality of the stimulus is prioritised over instrumental reward, paving the way for a self-catalytic process (Frenette and Ocejo, 2018).

To fully leverage upon the growth potential of the CCS, there is a need of creating a culturally and creatively vibrant environment where workers can find the best context to develop their skills. Such culturally thriving context also favours the exposure to cultural stimuli of non-professionals, who increase their levels of active and passive cultural participation. This has significant effects in terms of both skills development and honing of pro-social attitudes and behaviours, for instance in the sphere of environmentally responsible practices such as waste recycling and energy saving behaviours (Crociata et al., 2015). This raises the already mentioned issue of the omission of CC from the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The fact that they have never been explicitly mentioned in any of the goals may be partly responsible for the difficulty in properly acknowledging the role of CCS in terms of growth at least. This omission has been noted and highlighted with reference to the broader definition of culture in the socio-anthropological sense (Zheng et al., 2021), but once again to date there has been no specific recognition of the role of culture in the more specific sense of intentional aesthetic creation.

Might there be a reason to introduce a new culture and creativity-themed SDG in this latter meaning, for instance in terms of ensuring a fair access to cultural and creative opportunities to all human beings to reap the socio-behavioural and cognitive benefits of cultural participation? Based on the analysis provided in this paper, we believe that this is the case, and invite both policymakers and cultural and creative stakeholders to seriously consider this possibility and to act accordingly. In our view, the results provided in this paper offer useful support in making a case for it.

The article also has some methodological limitations. The study builds on a theoretical foundation, and empirical considerations of skills related to CCS present a secondary analysis only. PIAAC, despite being the most suitable dataset to answer questions related to skills and competences of adult populations, as well as providing a robust and comprehensive dataset for analysing the skills of workers in the cultural and creative sectors, is primarily focused on the skills of early-career workers. This feature could potentially lead to an underestimation of the lifetime returns to skills, as the analysis with PIAAC might not fully capture the skill development and career progression over time. Moreover, PIAAC assesses key information-processing skills such as literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving. While these skills are undoubtedly important, they might not encompass all the specific skills required in the cultural and creative sectors. For instance, creative abilities, artistic talents, or specific technical skills might not be adequately captured by the PIAAC survey. The same holds for the skills most useful and needed in productive sectors other than CCS. It would then be of special importance to replicate our analyses on different and ideally larger skills sets to check whether our results reflect a deep structural trend or are at least in part an artefact of the specific skills set considered in this study. Future research could therefore benefit from incorporating further data and growth-related measures of cognitive and social outcomes from CC engagement in professional contexts, as well as of other key skills of particular relevance in any kind of productive sector. Finally, as we mentioned in the Methods section, the international comparability of PIAAC data might be affected by country-specific factors. The factors related to unionization, employment protection, and importance of the public-sector in the economy could influence the returns to skills in different countries, potentially complicating cross-country comparisons. In addition, the study’s scope, constrained by the PIAAC’s geographical coverage, limits the geographical generalizability of its findings. As remarked above, the capacity of CC to hone key growth-related skills need not, at least in principle, carry over to other socio-economic and cultural settings.

Adding to the limitations already discussed, it is important to note that our study, like many others based on observational data such as PIAAC, faces challenges in establishing causal relationships due to the lack of experimental control over variables. While observational studies can suggest causal relationships, they often require experimental assignment to treatment and control groups to support or reject these suggestions. Additionally, the presence of confounding factors and selection bias can distort the results. Reverse causality might also be an issue. Despite the considerations offered above, we cannot rule out in principle that the possession of skills influences the career path in the CCS and not that employment in CCS stimulates growth of skills. This limitation is, however, inherent in observational studies and can potentially bias our results. The cross sectional design of PIAAC is also problematic because in order to establish causality, it would be beneficial to measure the independent variable before the dependent variable. Yet, in cross-sectional data like PIAAC, it can be challenging to establish this temporal order, and this further complicates the establishment of causal relationships.

In the light of these limitations, the findings of our study should be interpreted with caution. While we believe that our study provides valuable insights into the skills of workers in the cultural and creative sectors and their potential contribution to growth, further research, ideally using experimental or quasi-experimental designs, would be beneficial to establish actual causal relationships.

Conclusions

In this study, we have offered a preliminary exploration of the role played by culture and creativity (CC) in contemporary growth paradigms, a topic that has been somewhat overlooked in mainstream discussions. Our research pivots on the premise that integrating culture and creativity into growth models can unveil a so far poorly understood driver of skills building and its important productivity and social sustainability implications.

The argument moves from the underappreciated economic value of culture and creativity. It is maintained that CC sectors are not merely peripheral economic domains related to leisure and entertainment but play a central role in a comprehensive growth paradigm. Notably, jobs within the CC sectors are characterised by higher levels of problem-solving, literacy, and numeracy skills compared to other sectors. This finding is crucial, as it positions CC jobs not just as contributors to the economic value but as fundamental to enhancing the skills basis of growth. Our results align well with the existing literature on the potential contributions of CC to growth that stresses how cultural and creative sectors and the related jobs harness people’s cognitive flexibility and capacity for constant adaptation and creative problem solving.

Moreover, although not providing new evidence in this respect, the paper stresses the well-documented positive impact of cultural participation on pro-social attitudes and behaviours, which may have a major impact on our capacity to respond to societal challenges, thereby underscoring the dual role of CC in acting on both the supply and demand sides of socially sustainable growth.