Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly altered socio-economic activities, human behaviors, and crime patterns. However, less is known about how the pandemic and associated restrictions affected cyber-enabled and traditional fraud. Here, we conducted a retrospective analysis using police-recorded crime data in the UK to examine the impact of COVID-19 restrictions and changes in human activity on fraud. Results indicate that following the onset of the lockdown, the number of recorded fraud cases increased by 28.5%, contrasting with traditional property crimes, which dropped by 28.1%. However, the lockdown did not have a significant impact on the long-term trend of fraud. With the lifting of restrictions, fraud gradually regressed to levels approaching those before the pandemic. By inspecting the effects of different government responses and changes in population mobility on various types of fraud, we found that more stringent restrictions were associated with larger increases in most types of cyber-enabled fraud, except for those that rely on offline activities, whereas the impact on traditional fraud was mixed and contingent upon specific opportunity structures. These findings overall align with the assumptions of routine activity theory and provide clear support for its applicability in fraud and cybercrime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic caused unprecedented social, economic and psychological disruptions across the globe (Josephson et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2022). The containment policies implemented by governments to control the spread of the virus, such as stay-at-home requirements, restrictions on gatherings, and closures of public and entertainment venues, dramatically altered socioeconomic activities and human behaviors (Hussain et al. 2020; DeFilippis et al. 2022; Yang et al. 2022). These changes also impacted criminal opportunities and motivations in multiple ways, thereby reshaping crime patterns (Ashby 2020; Langton et al. 2021). Research from various countries indicates that the pandemic and lockdown measures led to a substantial decline in total crimes due to reduced interactions in public spaces (Boman and Mowen 2021; Nivette et al. 2021). This was particularly pronounced in traditional street crimes such as assaults, thefts, and robberies (Gerell et al. 2020; Abrams 2021; Campedelli et al. 2021; Estévez-Soto 2021; Nivette et al. 2021). On the other hand, preliminary evidence suggests a notable rise in fraud and cybercrime during the lockdown, which is interpreted as a shift of criminal opportunities from physical space to cyberspace (Buil-Gil et al. 2021a). However, compared to the extensive focus on traditional crimes, the mechanisms through which the pandemic affects fraud and cybercrime remain unclear.

Fraud refers to the willful deception, misrepresentation, or other tactics to secure an illicit advantage or cause a disadvantage to others, covering a range of civil or criminal activities (Button and Cross, 2017). Despite its contemporary association with technological elements such as “Internet”, “cyber” or “online”, traditional forms of fraud have existed for a long time and can occur offline (Kemp et al. 2020). The advancement of information and communication technologies (ICTs) has furnished fraud with novel means, increasing its scale and scope. Fraud that leverages ICTs is also recognized as a type of cyber-enabled crime (McGuire and Dowling 2013; Leukfeldt et al. 2020). This study focuses on traditional forms of offline fraud (hereinafter referred to as traditional fraud) and cyber-enabled fraud using ICTs. The outbreak of COVID-19 presented a fertile ground for criminal opportunism. Capitalizing on the public’s heightened uncertainty, anxiety, and fear, fraudsters rapidly adapted their modus operandi, resulting in a substantial increase in COVID-related fraud, particularly cyber-enabled fraud (Naidoo 2020; Buil-Gil et al. 2021b; Ma and McKinnon 2021; Plachkinova 2021; Alawida et al. 2022). Given that many traditional crimes have gradually returned to pre-pandemic levels with the lifting of restrictions(Balmori de la Miyar et al. 2021; Nivette et al. 2021; Trajtenberg et al. 2024), it is of interest to investigate whether fraud has been similarly affected. Furthermore, as fraud encompasses a broad spectrum of illicit activities, each with distinct opportunity structures, it is necessary to explore the mechanisms through which the COVID-19 pandemic differentially impacted distinct types of fraud.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK, like many countries, experienced several waves of increasing and decreasing rates of infection. The government implemented three national lockdowns along with a variety of control measures to mitigate its impact. The first national lockdown began in late March 2020 and ended in June 2020: schools and non-essential businesses were closed and people were ordered to stay at home except for essential reasons. The second national lockdown was introduced on 5 November 2020: non-essential businesses were closed, while schools and workplaces remained open, and people were allowed to meet with one person from outside their household outdoors. The third national lockdown was implemented on 6 January 2021 to contain the spread of the Alpha variant: restrictions resembled those in the first lockdown, schools and non-essential businesses were forced to shut again, and people were once again ordered to stay at home. On 8 March 2021, a four-step plan to “cautiously but irreversibly” ease lockdown restrictions came into effect. In February 2022, the “living with COVID-19” plan was released to lift all the remaining restrictions, and the country gradually returned to normal life as before the pandemic. The changes in government restrictions and the resultant alterations in human behaviors also provide a unique opportunity to examine how changes in opportunity structures could affect the patterns of fraud.

Previous studies have indicated that the immediate decrease in traditional street crime can be explained by reduced opportunities for offenders to converge with targets in physical spaces, while such opportunities simultaneously increased in digital environments (Hawdon et al. 2020; Payne 2020; Buil-Gil et al. 2021a; Kemp et al. 2021; Plachkinova 2021). Routine Activity Theory (RAT) posits that the convergence of a potential victim, a likely offender, and the absence of capable guardianship leads to an increase in crime (Cohen and Felson 1979). A central tenet of RAT is that changes in routine activities could influence the opportunity for crimes to occur, making the theory widely applicable in explaining how significant alterations in human behavior following public emergencies affect crime patterns (Decker et al. 2007; Frailing and Harper 2017; Felson et al. 2020; Johnson and Nikolovska 2024). Within the framework of RAT, we conduct a retrospective analysis to examine the mechanisms through which COVID-19 impacted fraud in the UK. Firstly, we reviewed existing literature on the impact of the pandemic on fraud and cybercrime and explored how the pandemic and associated restrictions potentially affected the three elements of RAT. Next, based on long-term fraud and other property crime records, we compared the effects of the pandemic on the long-term patterns of these two types of crime. Finally, we assessed the differential impacts of various government policies and mobility changes on specific types of fraud.

Literature review and theoretical framework

Cyber-enabled fraud and cybercrime during COVID-19

Against the backdrop of a general decline in many traditional crimes in offline environments (Tseloni et al. 2010; Farrell 2013; Van Dijk et al. 2022), fraud and cybercrime have increased precipitously in recent years and become a leading crime threat globally (Ionescu et al. 2011; Anderson et al. 2019; Alnuaimi and Alawida 2023), with evidence suggesting this was further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Buil-Gil et al. 2021a; Chigada and Madzinga 2021; Baig et al. 2023). The pandemic and related lockdowns present a natural experiment to understand how extensive changes in routine activities affect the patterns of fraud and cybercrime. Despite the preliminary results from Hawdon et al. (2020), which argued the pandemic did not radically change cyber-victimization rates in the United States, other studies have observed noticeable changes in fraud and cybercrime when compared with historical trends. For example, Buil-Gil et al. (2021a) and Kemp et al. (2021) observed immediate rises in fraud and cybercrime in the UK after the introduction of lockdown measures, whereas Chen et al. (2023) found that cyber-enabled fraud in a medium-sized city of China experienced a significant reduction during the lockdown period, and quickly returned to pre-COVID-19 levels. In the longer term, Buil-Gil et al. (2021a) showed that while most traditional crimes returned to the pre-COVID-19 levels when lockdown restrictions were lifted, the pandemic accelerated the long-term upward trend of cybercrime in Northern Ireland. Johnson and Nikolovska (2024) indicated that online shopping fraud and hacking increased, while doorstep fraud decreased, but the changes were not persistent and were closely coupled with the patterns of mobility and online activities. A recent systematic review from Hoeboer et al. (2024) further revealed the inconsistent findings regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fraud: while most studies indicate a decrease in fraud in response to COVID-19 restrictions (n = 3), other studies report an increase in fraud (n = 1), or found no association with restrictions (n = 1).

These studies provide valuable early insights into the impact of COVID-19 on fraud. However, existing research has largely been conducted during the early stages of the pandemic. On May 5, 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the end of COVID-19 as a public health emergency. While the lockdowns and restrictions were gradually lifted, some of the economic and societal changes caused by the pandemic could be long-lasting (Collier et al. 2020; Johnson and Nikolovska 2024). Therefore, understanding whether the pandemic has influenced the long-term trajectory of fraud is crucial for assessing and explaining the impact of rapid social changes on crime levels as well as for developing prevention mechanisms and strategies and allocating criminal justice resources effectively. Moreover, few studies have compared traditional fraud and cyber-enabled fraud within the same context, leading to mixed results across studies. Considering that the opportunity structures of different types of fraud may be essentially different, it is necessary to further explore the differentiated impact of the pandemic and related restrictions on various types of fraud.

Routine activity theory

Opportunity theory and Routine Activity Theory (RAT) of crime suggest that crime occurs when three elements converge in time and space: a likely offender, a suitable target, and the absence of capable guardianship (Cohen and Felson 1979; Leukfeldt and Yar 2016). Although RAT was initially proposed to explain traditional offline crimes, much research has extended it to cyberspace and examined its applicability to cybercrime and fraud (Holt and Bossler 2008; Pratt et al. 2010; Leukfeldt and Yar 2016). For cyber-enabled fraud, the convergence of the three core elements of RAT occurs within the virtual environment, where it may be discontinuous in both time and space. For instance, cyber fraudsters located in Country A may send messages to potential targets in Country B via email or online social platforms, which the recipients may not see until hours or days later. Despite the absence of immediate interaction between the parties, this does not preclude the possibility of the recipients eventually falling victim to fraud (Holt and Bossler 2015). Some argue that the inherent nature of cyberspace, which is unconstrained by physical or temporal boundaries, may increase the likelihood of convergence of the three elements described by RAT (Miró Llinares and Johnson 2018).

In this study, we apply RAT as a theoretical framework to explain the effect of COVID-19 on fraud crimes. From the perspectives of RAT, the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictive measures may affect the opportunity structure of fraud by altering the status of the three elements of RAT:

Suitable target

The pandemic accelerated the digital transformation across the globe. Stay-at-home orders and social distancing measures led to a surge in online activity for work, education, entertainment, and shopping (Alipour et al. 2021; Yang et al. 2022). This increased reliance on digital platforms expanded the pool of potential targets for cyber-enabled fraud. Work-from-home also increased the chances for employees to adopt insecure networks, devices and actions, leaving individuals and organizations more vulnerable to cybersecurity risks (Király et al. 2020; Khweiled et al. 2021; Klint 2023). In addition, individuals facing economic hardship, health concerns, and other stressors could be more susceptible to fraud schemes (Zhang et al. 2022). This vulnerability was exacerbated by social isolation, reduced access to support networks, and heightened stress and anxiety.

Likely offender

The economic impact of the pandemic, including job losses and financial strain, prompted individuals to seek alternative sources of income. This could lead to increased motivations to engage in illicit activities such as fraud (Hawdon et al. 2020). The chaos and disruption caused by the pandemic could also augment the motivations of opportunistic offenders to exploit crisis situations and emergencies, as they can readily leverage the emotional, economic, and health-related needs and vulnerabilities of individuals to perpetrate fraudulent schemes.

Absence of capable guardianship

Law enforcement agencies and regulatory bodies faced challenges in effectively combating fraud amidst the pandemic. Resource constraints, shifting priorities, and the need to enforce public health measures diverted attention and resources away from fraud prevention and investigation efforts (Laufs and Waseem 2020). The pandemic also disrupted traditional oversight mechanisms, such as in-person inspections, audits, and regulatory compliance checks, creating opportunities for fraudsters to operate with insufficient scrutiny and accountability.

Hence, the COVID-19 pandemic could reshape the opportunity structure of fraud by intensifying the motivation of offenders, increasing the number of suitable targets, and undermining the capability of guardianship. With all these factors combined, one might expect an increase in the overall incidence of fraud. However, it is crucial to recognize that there are significant differences in how the pandemic affects the convergence of these elements for traditional fraud and cyber-enabled fraud. Given the constraints imposed by lockdown restrictions on physical movement during the pandemic, traditional forms of fraud such as door-step fraud and retail fraud, which typically rely on face-to-face interactions and physical proximity, could experience reduced opportunities and were expected to decrease rather than increase (Kemp et al. 2021).

Materials and methods

Research design

This study aims to address the following two questions: a) whether COVID-19 lockdowns had an impact on the long-term trends of fraud, and b) how government responses and changes in human activity during the lockdown affected the patterns of different types of fraud. To answer these questions, we collected two types of police-recorded crime data: long-term monthly data on fraud and property crimes, and short-term daily data on cyber-enabled fraud and traditional fraud. Based on the monthly fraud and property crime data, we employed Interrupted Time Series (ITS) analysis to examine the impact of the lockdowns on the level and trend of fraud over a longer time frame, with property crime as a reference. Utilizing more granular daily-scale data on cyber-enabled fraud and traditional fraud following the third national lockdown in the UK, we quantified the effects of different government responses and changes in human mobility on various types of cyber-enabled fraud and traditional fraud by constructing Generalized Linear Models (GLMs). The framework of this study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Data

Crime data

Traditional property crime data was obtained from the UK crime open data portal (https://data.police.uk/data), covering 43 Police Force Areas in England, Wales and Northern Ireland from April 2014 to January 2024. The crimes included in the dataset fall into 14 categories, including bike theft, burglary, criminal damage and arson (CD&A), shoplifting, theft from the person, vehicle crime, other theft, and other 7 types of crimes. In this study, we aggregate the first 7 types of crime into property crimes to facilitate our analysis.

The monthly fraud data between April 2014 and January 2024 was accessed through a freedom of information request to the City of London Police. The City of London Police developed and oversees the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (NFIB), which runs Action Fraud, the UK’s national reporting center for fraud and financially motivated cybercrime. We incorporated monthly data on fraud and other property crime into the ITS models to estimate the impact of COVID-19 on crime trends over an extended time scale. Monthly fraud data and property crime data were utilized for ITS modeling.

In order to elucidate the mechanisms by which COVID-19 restrictions and associated changes in human activity impacted fraud, we collected finer-grained daily time series fraud data from the NFIB Fraud and Cybercrime Dashboard (https://www.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/0334150e430449cf8ac917e347897d46), published by Action Fraud. The daily time series data on fraud spans from December 2020 to September 2022, covering the period from the third national lockdown to the end of the pandemic in the UK. Compared to the monthly data above, this dataset provides more detailed information regarding the fraud types, time, and locations, enabling a more in-depth examination of the relationship between fraud trends and the restrictive measures and changes in human activity. The dataset comprises a total of 48 fraud types. However, certain types of fraud have too few cases to achieve statistical power, and were thus excluded from the analysis. Finally, 19 fraud types, including both traditional fraud and cyber-enabled fraud, were included. Additionally, we grouped these 19 fraud types into 7 major categories, including advance-fee and romance fraud, card and banking fraud, consumer fraud, investment fraud, retail fraud, service fraud, and other fraud. This typology is recommended by Correia (2022) and was developed to maximize statistical power while remaining compatible with existing typologies. GLMs were used to estimate the effects of government responses and mobility changes on different types of fraud.

Government responses and mobility

The government responses data were drawn from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) dataset, which collects systematic information on policy measures taken by governments (Hale et al. 2021). The OxCGRT dataset provides 4 comprehensive indices, including overall government response index, containment and health index, stringency index, and economic support index. Given that the OxCGRT indices measure the breadth and intensity of government policies but may not necessarily reflect their effectiveness in implementation, using these indices alone has inherent limitations. In order to complement these indices, we incorporated data from the Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports (https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility). This supplementary data provides valuable insights into how people actually respond to government measures by tracking changes in mobility patterns such as visits to retail and recreation areas, grocery stores and pharmacies, parks, transit stations, workplaces, and residential areas. By analyzing these mobility trends alongside the OxCGRT indices, we could gain a more comprehensive understanding of the stringency of government policies and their real-world impact on population behavior, which helps to understand how lockdown-induced changes in individuals’ daily activities and movements impact fraud.

Methods

Interrupted time series analysis

ITS analysis is a quasi-experimental design methodology commonly used to evaluate the longitudinal effectiveness of medical treatments, legislations, and policies among other interventions (Bernal et al. 2017). ITS analysis involves extrapolating pre-intervention trends into the post-intervention period to construct a counterfactual scenario representing what would have occurred in the absence of the intervention (Kontopantelis et al. 2015). Effects of the intervention can be evaluated by comparing counterfactual scenario with changes in the level and slope of the post-intervention period trend (Bernal et al. 2017). In an ITS design, an intervention should be implemented at a clearly defined point in time. In our investigation, the intervention pertains to the COVID-19 lockdowns. As lockdown measures came into effect almost immediately after the government announcements, ITS can be effectively applied.

In this study, we used a dummy variable to represent the intervention of COVID-19 lockdown, wherein the time periods preceding the first national lockdown (March 23, 2020) and post-implementation of the “living with COVID-19” policy (February 23, 2022) were coded as 0, while the time in between was coded as 1. Meanwhile, the months since the start of the study (time) and months since the first lockdown (time since lockdown) were included to represent the trends before and after the lockdown. To address the potential time-varying confounders of the ITS models, we included harmonic terms (pairs of sine and cosine functions) to account for seasonality (Bernal et al. 2017). The incidence rate ratio (IRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to estimate the effect of the lockdown on the incidence of crimes.

Generalized linear model

In this study, we use GLMs to estimate the effect sizes of government responses and mobility changes on fraud. A GLM is a regression model that extends ordinary regression to include non-normal response distributions and modeling functions (Faraway 2016). When constructing the GLMs, the dependent variables are the numbers of different types of fraud incidents recorded by the police, and the independent variables are the government responses and mobilities in different places. As the government responses and mobility trends are highly correlated with each other, we use them to build the GLMs separately. In addition, we include the holidays, day of the week, and month of the year to control for seasonal trends and potential time-varying confounders. All analyses were performed in R version 4.1.2 using the “stats” package, and figures were plotted using the “ggplot2” package.

Results

Immediate but divergent effects of lockdown on fraud and property crime

Our study first examined the long-term trends of fraud and other property crimes in the UK, as well as the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the patterns of these two types of crime. We employ ITS analysis to estimate these effects by comparing the actual crime trends with the counterfactual trends. The results of ITS suggest that the actual incidence of fraud consistently exceeded the projected level based on pre-pandemic trends, while the trend of traditional property crime remained below the counterfactual line (Fig. 2).

a Fraud. b Property crime. The solid blue line indicates the observed crime trend. The dashed orange line indicates the predicted crime trend if COVID-19 had not taken place (counterfactual scenario). The three dashed red lines correspond to the dates of the three national lockdowns (23 March 2020, 5 November 2020, and 6 January 2021), while the dashed green line the indicates the date the “living with COVID-19” plan was released (23 February, 2022).

Following the first national lockdown, significant shifts were observed in the patterns of recorded fraud and property crime: fraud surged dramatically following the lockdown, with an immediate increase of 28.5% in the number of monthly incidents (IRR: 1.285; 95% CI: 1.161–1.422; P < 0.001) (Table 1). However, this upward trend in fraud did not persist, which peaked in early 2021 during the third national lockdown, before plummeting to pre-pandemic levels around early 2022, coinciding with the introduction of the “living with COVID-19” policy. In contrast, property crime exhibited a rapid decline following the lockdown, with the number of monthly incidents falling by 28.1% (IRR: 0.719; 95% CI: 0.661–0.782; P < 0.001). During the first and third national lockdowns, the number of property crime incidents experienced two significant declines. As pandemic restrictions were relaxed, it gradually rebounded to near pre-pandemic levels and then continued its previous downward trend.

According to the trend coefficients before the lockdown (time), over the past decade, fraud in the UK gradually increased at a rate of 4.7% per year, while traditional property crime has exhibited a fluctuating decline at an annual rate of 1.4% (Table 1). The trend coefficients after the lockdown (time since lockdown) suggest that the change in fraud trend after the lockdown is not statistically significant. Although the trend coefficient for property crime is significant, the change in its trend is only marginal and temporary (IRR: 1.008; 95% CI: 1.002–1.013; P < 0.01). These results indicate that the pandemic and lockdown measures only had immediate effects on fraud and property crime but lacked sustained effects. In other words, the pandemic and lockdown measures only engendered short-term fluctuations in the levels of fraud and property crime, without altering their long-term trajectories. From the perspective of RAT, the lockdowns exerted a substantial but differential impact on fraud and traditional property crime by increasing the presence of offenders and targets in cyberspace while reducing their interactions in physical spaces. However, these effects gradually diminished as restrictions were lifted and routine activities resumed, restoring the opportunities for offenders to interact with targets in both physical and digital spaces to pre-pandemic levels. Subsequent analysis, accounting for crime seasonality, yielded results consistent with those presented herein (Figure S1).

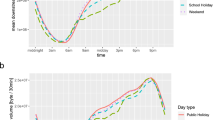

Responses of fraud to government policies and mobility changes

In order to gain a better understanding of how fraud relates to the pandemic and associated social changes, we compared trends in daily traditional fraud and cyber-enabled fraud incidents in the UK with government responses and human mobility patterns between December 2020 and September 2022. The Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) suggest that the trend of cyber-enabled fraud incidents is strongly correlated with the stringency index (r = 0.837, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3a), but shows opposite trend with the mobility in transit stations (r = −0.804, P < 0.001). Cyber-enabled fraud incidents peaked following the third national lockdown, and decreased gradually with the relaxation of lockdown measures and the recovery of mobility. After the beginning of 2022, the trend in cyber-enabled fraud levelled off, with only minor fluctuations. In comparison, the number of traditional fraud incidents was relatively smaller, with a weak negative correlation with the stringency index (r = −0.140, P < 0.001) and moderate positive correlation with the mobility in transit stations (r = 0.420, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3b). This further indicates that the increase in fraud during the lockdown period was primarily attributable to the rise in cyber-enabled fraud. Despite the presence of motivated offenders, lockdown measures restricted people’s outdoor activities and social interactions, significantly reducing the targets and opportunities for traditional fraud in physical spaces. In contrast, the strong correlation between cyber-enabled fraud and the stringency of lockdown measures demonstrates that the convergence of offenders and targets in cyberspace led to an increase in cyber-enabled fraud. The period around New Year’s Day saw a marked drop in both cyber-enabled fraud and traditional fraud, which appeared to be closely linked to the plummet in population mobility during holidays.

Varying effects on specific types of fraud

Next, we used GLMs to estimate the effect size of the stringency index on different types of fraud. Overall, the stringency index is associated with an increase in major categories of fraud, including consumer fraud, investment fraud, and other fraud, while it is related to a decrease in retail fraud (Table S1). However, the impact on specific types of fraud is not uniform. An increase in the stringency index leads to an increase in most types of cyber-enabled fraud (Table 2). Specifically, the stringency index exhibits the greatest impact on computer software service fraud, with each unit increase in the stringency index resulting in a 52% increase in computer software service fraud. Following this, “419” advance fee fraud, charity fraud, online shopping or auctions fraud, and share sales or boiler room fraud are respectively associated with increases of 29%, 25%, 22%, and 21% in response to increases in the stringency index. By contrast, an increase in the stringency index leads to a reduction in ticket fraud, rental fraud, pyramid or Ponzi schemes, and application fraud. Each unit increase in the stringency index results in reductions of 31%, 16%, 14%, and 8% respectively for these four types of cyber-enabled fraud.

The impact of the stringency index on traditional fraud is mixed. An increase in the stringency index is associated with a decrease in retail fraud, door to door sales or bogus tradesmen fraud, and fraud by abuse of position of trust. These three types of fraud particularly rely on interactions in physical spaces. According to RAT, lockdown measures restricted the movements of offenders and their opportunities to come into contact with targets, while enhancing the guardianship provided by society and families, thereby reducing the occurrence of these types of fraud. Notably, each unit increase in the stringency index results in a 68% increase in consumer phone fraud. Additionally, a higher stringency index is also associated with an increase in pension liberation fraud and other fraud (none of the above), with each unit increase in the stringency index leading to increases of 45 and 26% in these two types of fraud, respectively.

Given that different types of policies can have divergent impacts, and that population mobility reflects actual behavioral changes, we further examine the effects of different government responses and mobility changes on fraud. The results of the GLMs displayed in Fig. 4 indicate that overall government response index, economic support index, health and containment index, and stringency index exhibit similar patterns of influence on various types of fraud. The only discrepancy lies in the slight positive effect of the economic support index on application fraud and door to door sales or bogus tradesmen fraud, contrary to the effects of other indices. The influence of residential mobility aligns roughly with that of the stringency index, while contrasting with the effects of other non-residential mobilities (i.e., mobility in transit stations, workplaces, retail and recreation venues, grocery and pharmacy). Notably, population mobility in transit stations and retail and recreation venues exerts a greater impact on ticket fraud, rental fraud, and consumer phone fraud. Mobility in retail and recreation venues and grocery and pharmacy has a larger effect on retail fraud. The analysis results for the seven major categories of fraud are similar to the above: indicators reflecting stricter lockdown measures and increased residential mobility corresponded with an increase in consumer fraud, investment fraud, and other fraud, as well as a decrease in retail fraud. Conversely, indicators reflecting the relaxation of lockdown measures and increased non-residential mobility had the opposite effect (Figure S2).

Discussion

Over the past three decades, the drop in recorded property crime has remained a central feature of criminological discussion (Aebi and Linde 2010; Gruszczyńska and Heiskanen 2018). However, this seemingly declining trend has not taken into account the rapid growth of fraud crime. Although fraud is encompassed within the broad definition of property crime, it is often excluded from the analysis (Kemp et al. 2020). Our research indicates that, in the long-term trajectory, the growth rate of fraud crime in the UK surpasses the rate of decline observed in traditional property crimes. While the absolute number of fraud cases recorded by the police is significantly lower than that of traditional property crimes, considering the low reporting rate of fraud (Kemp et al. 2020; Correia 2022), the rapid growth in fraud crime is sufficient to render the reduction in traditional property crimes seemingly inconsequential. Evidence from our study also suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic and related societal changes only resulted in short-term fluctuations in levels of fraud and traditional property crime in the UK, without substantively impacting their long-term trends. In fact, the pandemic and associated lockdowns significantly affected the short-term opportunity structures for fraud and other traditional crimes. Social distancing measures reduced opportunities for contact between victims and offenders in physical spaces, leading to a substantial decrease in traditional property crimes. Meanwhile, during lockdown periods, increased time spent online led to a significant rise in fraud, as offenders and victims had more opportunities to interact in virtual spaces. Following the relaxation of pandemic restrictions, as population mobility and daily activities gradually resumed, fraud, like other traditional crimes, also returned to pre-pandemic levels. Subsequent analysis further substantiates this, as trends in fraud, particularly cyber-enabled forms of advance fee fraud, consumer fraud and investment fraud, are closely coupled with changes in stringency of restrictions and population mobility.

The analysis of the seven major categories of fraud indicates that the strengthening of lockdown measures significantly contributed to an increase in consumer fraud, investment fraud, and other fraud, while reducing retail fraud. However, by modeling specific types of fraud separately, we found that the impact of lockdown measures within each category of fraud is not homogeneous but depends on the extent of their online components and their connection to offline human activities. This reflects the importance of contextual and situational factors in the occurrence of crime, as emphasized by opportunity theory and routine activity theory, where each type of crime has its unique opportunity structure. Overall, we have observed a correlation between more stringent restrictions and the increase in most types of cyber-enabled fraud.

Specifically, there is a pronounced increase in computer software service fraud, “419” advance fee fraud, charity fraud, online shopping and auctions fraud, as well as share sales or boiler room fraud during lockdown periods. During the strictest period of lockdown, individuals are compelled to adopt the internet for socializing, shopping, working, and other online activities. According to RAT, longer internet usage and increased online shopping activities enhance target visibility and accessibility, thereby increasing individuals’ exposure to fraud victimization (Pratt et al. 2010; Kennedy et al. 2021). This may explain the rise in computer software service fraud and online shopping and auctions fraud. The escalation in consumer phone fraud can also be attributed to similar reasons. Although consumer phone fraud is not perpetrated through online means, it also exhibits non-contact characteristics and remains unhindered. Additionally, the economic downturn, social disorder, and emotional stress accompanying lockdowns make it difficult for individuals to make rational decisions and judgments (Bogliacino et al. 2021), thereby increasing target suitability. For instance, the pandemic-induced economic instability led to job losses or income reductions for many individuals, increasing their desire for quick monetary gains. Some investors may be more susceptible to the allure of high-yield investment opportunities without thoroughly considering the associated risks, resulting in an increase in investment-related fraud. Moreover, the heightened empathy during disasters may be exploited by criminals (Aguirre and Lane 2019), and the rampant dissemination of false and misleading information during the pandemic makes it challenging for individuals to distinguish between fraudulent charity websites and genuine ones, contributing to the increase in charity fraud.

However, not all types of cyber-enabled fraud increased in tandem with the severity of restriction measures. For instance, ticket fraud, rental fraud, pyramid or Ponzi schemes, and application fraud do not exhibit such a pattern. It is noteworthy that these four types of cyber-enabled fraud rely on certain types of offline activities. Specifically, ticket fraud is typically associated with real-world events such as sports games, concerts, and flights. Due to pandemic restrictions on the opening of large-scale events and gathering places, many performances, exhibitions, sports events, flights, and other activities were canceled or postponed. Consequently, the targets of ticket fraudsters diminished, and their opportunities correspondingly decreased. Similarly, with school closure and work-from-home orders, people spent most of their time living with family and friends at home, potentially reducing the demand for relocation and rental housing, thereby decreasing occurrences of rental fraud. Pyramid or Ponzi schemes typically rely on face-to-face socializing and gatherings to recruit new victims or organize meetings at expensive venues to appear credible, activities which were also impacted by lockdown restrictions. This has important implications for crime prevention and policy, highlighting the need to enhance fraud detection systems and public awareness campaigns focused on fraud types that rely on online interactions when physical activity is severely impacted by rapid social changes. In the long run, there is also a need to monitor the resurgence of fraud types dependent on physical interaction, as opportunities may increase with the return of in-person activities. During the process of applying for opening financial accounts, some financial institutions may require applicants to complete certain offline activities (e.g., mailing documents or visiting branches) to finalize their applications, which may explain the decrease in application fraud during lockdown periods.

For traditional fraud that rely entirely or mostly on offline activities, their numbers also decrease as lockdown measures intensify. For instance, the reduction in retail fraud, door to door sales and bogus tradesmen, and fraud by abuse of position of trust is akin to other traditional property crimes, primarily due to social distancing restrictions reducing opportunities for victims to come into contact with offenders in physical spaces. Pension liberation fraud and other scams are exceptions. The COVID-19 pandemic not only had the greatest impact on the health of the elderly but also inflicted significant damage to their psychological and economic well-being (Pant and Subedi 2020; Grolli et al. 2021), with concerns about finances or inheritance prompting them to consider pension transfers. Fraudsters persuade the elderly to transfer their pensions by designing lucrative investment proposals, exploiting the lack of vigilance and discernment in elderly individuals, particularly when rushed or under pressure. Additionally, common methods for pension fraudsters to contact victims include cold-calling, text messages, or unsolicited emails, none of which are hampered by lockdown restrictions. Since other types of fraud encompass many known classification and recording errors (Correia 2022), they may actually include some fraud conducted through online means, hence showing an increased response to lockdowns.

By estimating the varying impacts of different types of government responses and population mobility on fraud, we have found that the economic support index has a certain positive effect on application fraud and door to door sales or bogus tradesmen fraud, indicating that fraudsters may exploit government-implemented economic support policies in designing their schemes. The increase in population mobility in transit stations and retail and recreation venues has a greater impact on ticket fraud, while the impact of mobility in retail and recreation venues and grocery and pharmacy on retail fraud is more pronounced, highlighting the sensitivity of these two types of fraud to changes in population mobility within their primary occurrence settings. This is because the increase in population mobility at transit stations and retail and recreation venues is closely associated with increased ticket purchases for activities such as flights, offline concerts, and sports events, whereas the increase in population mobility at retail and recreation venues and grocery and pharmacy reflects an increase in retail activities. Overall, the pandemic and lockdowns produced heterogeneous impacts on fraud, contingent upon their effects on specific opportunity structures. The findings of this study broadly align with the assumptions of routine activity theory, providing clear support for its applicability in fraud and cybercrime.

This study provides solid evidence and deeper insights about how the pandemic and associated lockdown restrictions affected fraud. The long-term time-series data allow us to mitigate the impact of short-term fluctuations. Correction for seasonality, and the fine-grained fraud data ensure the robustness and reliability of our results. However, there are some limitations that need to be addressed in the future. Firstly, our study suffers from the common problem facing many crime research, that is, the under-reporting of police recorded crimes and especially fraud and cybercrime (Leukfeldt and Yar 2016; van de Weijer et al. 2020). According to the telephone-operated Crime Survey for England and Wales (TCSEW), only 9% of fraud experienced by individuals were reported to police through Action Fraud in the year ending March 2021 (Elkin 2021). Similarly, Kemp et al. (2023) found that only 8% of cyber-related incidents suffered by companies in the UK are reported to public authorities. Subsequent research could consider integrating victim survey data to enhance the robustness of the findings. Furthermore, fraud is a complex human behavior influenced by multiple factors including offenders, victims, and external environments. This study only incorporated pandemic-related factors, and future research, given data availability, could encompass a broader range of socio-economic factors such as unemployment rates, income levels, personal well-being and online activities to improve the explanatory power of the model. At last, our study covers only the UK and its subnational regions. Other countries enforced different responses to the pandemic and to changes in crime (Lazarus et al. 2020; Díaz et al. 2022). It is of interest to extend future studies into more developing and developed countries and include more socioeconomic predictors to further improve the generalizability of the results.

Data availability

All data used in this study can be found in Section 3: Materials and methods.

References

Abrams DS (2021) COVID and crime: An early empirical look. J Public Econ 194:104344

Aebi MF, Linde A (2010) Is there a crime drop in Western Europe? Eur J Crim Policy Res 16:251–277

Aguirre BE, Lane D (2019) Fraud in disaster: Rethinking the phases. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 39:101232

Alawida M, Omolara AE et al. (2022) A deeper look into cybersecurity issues in the wake of Covid-19: A survey. J King Saud Univ -Computer Inf Sci 34(10):8176–8206

Alipour J-V, Fadinger H et al. (2021) My home is my castle–The benefits of working from home during a pandemic crisis. J Public Econ 196:104373

Alnuaimi RA, Alawida M (2023) Understanding Cyberterrorism: Exploring Threats, Tools, and Statistical Trends, 2023 IEEE Intl Conf on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, Intl Conf on Pervasive Intelligence and Computing, Intl Conf on Cloud and Big Data Computing, Intl Conf on Cyber Science and Technology Congress (DASC/PiCom/CBDCom/CyberSciTech), IEEE

Anderson R, Barton C et al. (2019) Measuring the changing cost of cybercrime. The 18th Annual Workshop on the Economics of Information Security

Ashby MP (2020) Initial evidence on the relationship between the coronavirus pandemic and crime in the United States. Crime Sci 9(1):1–16

Baig Z, Mekala SH et al. (2023) Ransomware attacks of the COVID-19 pandemic: Novel strains, victims, and threat actors. IT Professional 25(5):37–44

Balmori de la Miyar JR, Hoehn-Velasco L et al. (2021) The U-shaped crime recovery during COVID-19: Evidence from national crime rates in Mexico. Crime Sci 10(1):14

Bernal JL, Cummins S et al. (2017) Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol 46(1):348–355

Bogliacino F, Codagnone C et al. (2021) Negative shocks predict change in cognitive function and preferences: Assessing the negative affect and stress hypothesis. Sci Rep. 11(1):3546

Boman JH, Mowen TJ (2021) Global crime trends during COVID-19. Nat Hum Behav 5(7):821–822

Buil-Gil D, Miró-Llinares F et al. (2021) Cybercrime and shifts in opportunities during COVID-19: a preliminary analysis in the UK. Eur Societies 23(sup1):S47–S59

Buil-Gil D, Zeng Y (2021a) Meeting you was a fake: investigating the increase in romance fraud during COVID-19. J Financ Crime 29(2):460–475

Buil-Gil D, Zeng Y et al. (2021b) Offline crime bounces back to pre-COVID levels, cyber stays high: interrupted time-series analysis in Northern Ireland. Crime Sci 10(1):1–16

Button M, Cross C (2017) Cyber frauds, scams and their victims, Routledge

Campedelli GM, Aziani A et al. (2021) Exploring the immediate effects of COVID-19 containment policies on crime: An empirical analysis of the short-term aftermath in Los Angeles. Am J Crim Justice 46(5):704–727

Chen P, Kurland J et al. (2023) Measuring the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on crime in a medium-sized city in China. J Exp Criminol 19(2):531–558

Chigada J, Madzinga R (2021) Cyberattacks and threats during COVID-19: A systematic literature review. South African. J Inf Manag 23(1):1–11

Cohen LE, Felson M (1979) Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. Crime: Crit Concepts Sociol 1:316

Collier B, Horgan S et al. (2020) The implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for cybercrime policing in Scotland: A rapid review of the evidence and future considerations. Briefing paper. (Research Evidence in Policing: Pandemics). Scottish Inst Policing Res

Correia SG (2022) Making the most of cybercrime and fraud crime report data: a case study of UK Action Fraud. Int J Popul Data Sci 7:1

Decker SH, Varano SP et al. (2007) Routine crime in exceptional times: The impact of the 2002 Winter Olympics on citizen demand for police services. J Crim justice 35(1):89–101

DeFilippis E, Impink SM et al. (2022) The impact of COVID-19 on digital communication patterns. Humanities Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–11

Díaz C, Fossati S et al. (2022) Stay at home if you can: COVID-19 stay-at-home guidelines and local crime. J Empir Leg Stud 19(4):1067–1113

Elkin M (2021) Crime in England and Wales: Appendix tables-Year ending March 2021. ONS, Titchfield, UK

Estévez-Soto PR (2021) Crime and COVID-19: Effect of changes in routine activities in Mexico City. Crime Sci 10(1):1–17

Faraway JJ (2016) Extending the linear model with R: generalized linear, mixed effects and nonparametric regression models, Chapman and Hall/CRC

Farrell G (2013) Five tests for a theory of the crime drop. Crime Sci 2(1):1–8

Felson M, Jiang S et al. (2020) Routine activity effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on burglary in Detroit, March, 2020. Crime Sci 9(1):10

Frailing K, Harper DW (2017) Toward a criminology of disaster: What we know and what we need to find out, Springer

Gerell M, Kardell J et al. (2020) Minor covid-19 association with crime in Sweden. Crime Sci 9(1):1–9

Grolli RE, Mingoti MED et al. (2021) Impact of COVID-19 in the mental health in elderly: psychological and biological updates. Mol Neurobiol 58:1905–1916

Gruszczyńska B, Heiskanen M (2018) Trends in police-recorded offenses at the beginning of the twenty-first century in Europe. Eur J Crim Policy Res 24(1):37–53

Hale T, Angrist N et al. (2021) A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat Hum Behav 5(4):529–538

Hawdon J, Parti K et al. (2020) Cybercrime in America amid COVID-19: The initial results from a natural experiment. Am J Crim Justice 45(4):546–562

Hoeboer C, Kitselaar W et al. (2024) The impact of COVID-19 on crime: A systematic review. Am J Crim Justice 49(2):274–303

Holt T, Bossler A (2015) Cybercrime in progress: Theory and prevention of technology-enabled offenses. Routledge

Holt TJ, Bossler AM (2008) Examining the applicability of lifestyle-routine activities theory for cybercrime victimization. Deviant Behav 30(1):1–25

Hussain MW, Mirza T et al. (2020) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the human behavior. Int J Educ Manag Eng 10(8):35–61

Ionescu L, Mirea V et al. (2011) Fraud, corruption and cyber crime in a global digital network. Econ, Manag Financial Mark 6(2):373

Johnson SD, Nikolovska M (2024) The effect of COVID-19 restrictions on routine activities and online crime. J Quant Criminol 40(1):131–150

Josephson A, Kilic T et al. (2021) Socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 in low-income countries. Nat Hum Behav 5(5):557–565

Kemp S, Buil-Gil D et al. (2023) When do businesses report cybercrime? Findings from a UK study. Criminol Crim Justice 23(3):468–489

Kemp S, Buil-Gil D et al. (2021) Empty streets, busy internet: A time-series analysis of cybercrime and fraud trends during COVID-19. J Contemp Crim Justice 37(4):480–501

Kemp S, Miró-Llinares F et al. (2020) The dark figure and the cyber fraud rise in Europe: Evidence from Spain. Eur J Crim Policy Res 26(3):293–312

Kennedy JP, Rorie M et al. (2021) COVID-19 frauds: An exploratory study of victimization during a global crisis. Criminol Public Policy 20(3):493–543

Khweiled R, Jazzar M et al. (2021) Cybercrimes during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Inf Eng Electron Bus 13:2

Király O, Potenza MN et al. (2020) Preventing problematic internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consensus guidance. Compr Psychiatry 100:152180

Klint R (2023) Cybersecurity in home-office environments : An examination of security best practices post Covid. Student thesis 53, Skövde, Sweden, University of Skövde, School of Informatics

Kontopantelis E, Doran T et al. (2015) Regression based quasi-experimental approach when randomisation is not an option: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ 350:h2750

Langton S, Dixon A et al. (2021) Six months in: pandemic crime trends in England and Wales. Crime Sci 10(1):1–16

Laufs J, Waseem Z (2020) Policing in pandemics: A systematic review and best practices for police response to COVID-19. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 51:101812

Lazarus JV, Ratzan S et al. (2020) COVID-SCORE: A global survey to assess public perceptions of government responses to COVID-19 (COVID-SCORE-10). PloS One 15(10):e0240011

Leukfeldt ER, Notté R et al. (2020) Exploring the needs of victims of cyber-dependent and cyber-enabled crimes. Vict Offenders 15(1):60–77

Leukfeldt ER, Yar M (2016) Applying routine activity theory to cybercrime: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Deviant Behav 37(3):263–280

Ma KWF, McKinnon T (2021) COVID-19 and cyber fraud: Emerging threats during the pandemic. J Financ Crime 29(2):433–446

McGuire M, Dowling S (2013) Cyber crime: A review of the evidence. Summary of key findings and implications. Home Res Rep. 75:1–35

Miró Llinares F, Johnson SD (2018) Cybercrime and place: Applying environmental criminology to crimes in cyberspace. The Oxford Handbook of Environmental Criminology, Oxford University Press

Naidoo R (2020) A multi-level influence model of COVID-19 themed cybercrime. Eur J Inf Syst 29(3):306–321

Nivette AE, Zahnow R et al. (2021) A global analysis of the impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home restrictions on crime. Nat Hum Behav 5(7):868–877

Pant S, Subedi M (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on the elderly. J Patan Acad Health Sci 7(2):32–38

Payne BK (2020) Criminals work from home during pandemics too: a public health approach to respond to fraud and crimes against those 50 and above. Am J Crim Justice 45(4):563–577

Plachkinova M (2021) Exploring the Shift from Physical to Cybercrime at the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Cyber Forensics Adv Threat Investig 2(1):50–62

Pratt TC, Holtfreter K et al. (2010) Routine online activity and internet fraud targeting: Extending the generality of routine activity theory. J Res Crime Delinquency 47(3):267–296

Trajtenberg N, Fossati S et al. (2024) The heterogeneous effects of COVID-19 lockdowns on crime across the world. Crime Sci 13(1):1–12

Tseloni A, Mailley J et al. (2010) Exploring the international decline in crime rates. Eur J Criminol 7(5):375–394

van de Weijer S, Leukfeldt R et al. (2020) Reporting cybercrime victimization: determinants, motives, and previous experiences. Polic: Int J 43(1):17–34

Van Dijk J, Nieuwbeerta P et al. (2022) Global crime patterns: An analysis of survey data from 166 countries around the world, 2006–2019. J Quant Criminol 38(4):793–827

Wang J, Fan Y et al. (2022) Global evidence of expressed sentiment alterations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Hum Behav 6(3):349–358

Yang L, Holtz D et al. (2022) The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. Nat Hum Behav 6(1):43–54

Zhang Y, Wu Q et al. (2022) Vulnerability and fraud: evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanities Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–12

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Project of China, grant number 2023YFB3107201 and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant number 2024M753189.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.J. and C.D.G. designed the research; S.C., F.Y.D., D.J., J.Z., and M.M.H. performed the research; S.C., F.Y.D., J.Z., J.P.D, and D.B. analyzed the data; S.C., J.Z., D.J., and M.M.H. wrote the first draft of the paper; D.B., J.Y.F., J.M., J.P.D, C.D.G., and D.J., gave useful edits, comments, and suggestions to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., Ding, F., Buil-Gil, D. et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on fraud in the UK. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1676 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04201-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04201-z

This article is cited by

-

The effect of true crime docuseries on romance fraud reporting to the police

Crime Science (2025)