Abstract

The growing presence of women in the Norwegian state and military heralds an epoch-making, worldwide transformation. A key challenge is to explain why institutions which excluded women for more than a millennium no longer promote all-male membership. This tectonic shift is investigated with a data-based synthetical methodology. Multidisciplinary evidence going back five thousand years is combined with a graphical analysis of two centuries of time series data. The guiding theory is that historical pathways for cultural information flow have coevolutionary spatial and energetic sociodynamics. Accordingly, women’s exclusion from warfare and politics in agrarian-era Norway coevolved with three interconnected constraints: oral communication, dependence on musculoskeletal energy, and the spatial limitations of person-to-person contact. The contemporary relaxation of such constraints is investigated using two centuries of data culled from Norway’s statistical yearbooks. These data show that women’s entry into Norway’s national legislature, pushed by women’s organizations, roughly coevolved with literacy-based communication and education, industrial-era extrasomatic energy, and distance-closing motorization. Multidisciplinary evidence also indicates that women’s military and political careers were spatiotemporally handicapped by inflexible work hours and worksites far from childrearing locations. The Norwegian military prioritized physical endurance rather than the competencies that women would later bring to a 21st-century rapid reaction force. Today, with new information pathways forming, the digitalized knowledge economy is reversing the human-capital advantage of men compared to women. Instantaneous information exchange and high-tech energetics are reducing spatiotemporal barriers via remote work. Cross-disciplinary and time-series evidence suggest that these digital-age dynamics contribute to a more gender-neutral state and military.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In dismantling historically male domains in the state and military, Norway ranks among the world’s trendsetters. Women have served as the head of state for more than 40 percent of the years since 1981 (Henderson, 2013, p. 43; Jørgensen, 2021, pp. 42–43), and women currently comprise 45 percent of national legislators (IPU, 2022, p. 11). Norway has had four female defence ministers since 2001 (CIA, 2024; DSS, 2013). One third of the conscripts in the armed forces are now women (Forsvaret, 2022). Yet military and political institutions in Norway have traditionally excluded women. Over the half millennium extending from 1300 to 1800, only one of Norway’s monarchs was a woman (Monter, 2012). Women were not able to vote until 1913 (Heffermehl, 1972), and women were not eligible for combat positions in the armed forces until 1985 (Rones, 2015a). In exploring why this long-enduring male monopoly over the Norwegian state and military is eroding now, digital era insight would suggest starting with an investigation of historical transformations in information dynamics.

Although cultural information flows are central to the analysis which follows, social and natural phenomena are inseparably interconnected in any investigation of gender (Siltanen and Doucet, 2008). For example, social organization around gender has a highly variable and historically changing relationship with the bioenergetics and the spatiotemporal dynamics of human bodies. To capture this varying historical relationship, coevolving informatics (Girard, 2020, 2024) offers a multidimensional lens. The theoretical focus is on a three-way dynamic in which growth in the depth of information networks reduces two key physical constraints: spatiotemporal barriers and energy-conversion barriers.

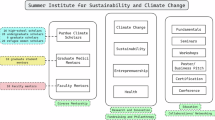

The depth of a cultural information network increases with the number of distinctive layers or pathways in the flow of information (Figs. 1 and 2). For example, the most basic pathway in cultural information flows is oral communication. Later, letterpress printing and digital media added distinctive pathways in the circulation of knowledge. This study will focus on how successive oral, textual, and digitalized pathways have impacted gender relations. These information pathways will be examined in the context of the spatiotemporal and energetic constraints of agrarian, industrial, and knowledge economies respectively.

Studies of historically fluid gender relations benefit from a multimethod approach (Siltanen and Doucet, 2008). Accordingly, consideration is first given to a multidisciplinary synthesis of findings regarding agrarian-era constraints on women’s careers. The focus then shifts to time series data for the last two centuries. Patterns in these data are assessed to determine the plausibility of a coevolving relationship between information pathways and constraints on women’s military and state participation.

Agrarian barriers to women’s state power

Mounting evidence indicates that male domination of the Norwegian state and military is likely to have emerged from agrarian sociodynamics. Revealed by pollen data indicating Neolithic cereal and grass fields, agrarian land use in Norway began to supplant foraging more than 5000 years ago (Hjelle et al., 2018). Norway’s transition from mobile foraging to fixed-site farming and herding established uniquely agrarian spatial dynamics, along with corresponding musculoskeletal energetics that govern all mobility and effort in agrarian societies (Krausmann, 2004). In such societies, people nearly always maintain physical proximity to the target of their musculoskeletal effort. Fields and animals are maintained with the peasant’s fingers and implements. Foes engage in hand-to-hand combat for defence of territory and honour. Mothers maintain proximity to babies from multiple pregnancies followed by long-term lactation. Communicators must be nearby for messages conveyed using the larynx’s muscles and body-generated gestures in predominantly oral cultures (Fig. 2a). For each of the key features of agrarian society, it is possible to pinpoint spatial and energetic constraints that impede women’s access to the Norwegian government and armed forces.

Close quarters combat sustains landholding

The overriding determinant of wealth in Norway from the Viking Age to the High Middle Ages was landholding (Bagge, 2010). Consequently, territorial conquest and defence were central to the state’s spatial dynamics. With the onset of agricultural and pastoral land use, wars were fought over resources concentrated in limited spatial locations, whether in river valleys, fertile fields, or harbours (Carneiro, 2012). Accordingly, among 590 cultures for which data were available, Wright (1942, appendix IX, table 11) found that when compared to foraging societies, societies completing the transition to agriculture or herding were the most prone to war.

Consistent with Wright’s (1942) findings, evidence from rock art and burial sites suggests that organized warfare became frequent in the aftermath of the transition from foraging to an agrarian economy in Norway (Horn, 2013; Ling and Cornell, 2017). In areas where agriculture developed during the Bronze Age, the presence of combat marks on weapons in burial sites, such as the mass grave in Sund, provide additional evidence of intensified warfare following the transition to farming (Fyllingen, 2003; Horn, 2018).

Given frequent battles over territory, agrarian societies placed a premium on the warrior’s musculoskeletal capacity for hand-to-hand combat in close quarters. Indeed, in all armed clashes from ancient times to the Middle Ages, handheld weapons delivered combatant communications primarily through direct contact with intended victims (Fig. 2a). Warriors were armed with close-range weapons such as swords, battle axes, maces, and spears. Longer-range weapons—slings, javelins, bows, and catapults—set the stage for battles but rarely ended them (Ferrill, 1997). Consequently, the soldier’s physical size and musculoskeletal power were often decisive in combat (Gabriel, 2007; Roth, 1999). Cerebral and communication capacities, for which men and women are equally endowed, were ultimately overshadowed by male musculature and body size in hand-to-hand combat.

The bioenergy dependence and the close-quarters spatial constraints of hand-to-hand fighting disadvantage female combatants. A female handicap in hand-to-hand combat is evident in early adulthood, when men typically have 75–90 percent greater strength than women in wrists, elbows, and shoulders. This gender difference in upper-limb strength is discernible in findings for two studies in Denmark (Harbo et al., 2012; Danneskiold-Samsøe et al., 2009). Widespread evidence for men’s upper-body advantage (1.9 times or nearly double women’s strength) was reported by Lassek and Gaulin (2009, p. 322) in their assessment of two studies in the U.S. (Bohannon, 1997; Murray et al., 1985) and a third study in Zürich, Switzerland (Stoll et al., 2000). In comparison to women, men also tend to have longer legs, larger lung capacity, and more oxygen-carrying haemoglobin, thereby enhancing exertion and speed (Ellis, 2008; Hopcroft, 2016). These male advantages in close-quarters combat are in accord with historical trends showing that less than one percent of all warriors in history, up until very recently, have been female (Ehrenreich, 1997).

Agrarian fiscal-military structure and male defence of honour

Male dominance in warfare translated into male dominance of the early Norwegian state because of the initial overlap in political and military hierarchies. The state’s limited financing for professional armies was addressed by levees requiring a direct military contribution from all male peasants and their overlords (Bagge, 2010). State financing was limited because at the core of subsistence farming, human and animal muscle power generate little product that is not immediately consumed (Foley, van Buren (1982); Fischer-Kowalski et al., 2014). Consequently, barriers to women’s state participation arose insofar as a direct military contribution was a central feature of Norway’s early political organization. The fusion of political and military roles is demonstrated by many early Norwegian monarchs such as Hákon Haraldsson (931–960 AD), Harald Hardrada (1046–1066 AD), and Magnus Barelegs (1093–1103 AD). These monarchs personally led their warriors in territorial clashes (Bagge, 2010). Given the centrality of military organization to the early agrarian state, men overwhelmingly dominated state structures in Norway. A well-known exception is Margaret, who ruled Norway from 1386 to 1412 and was officially known as a “regent” rather than a “monarch” (Monter, 2012).

Beyond war, there is an additional connection between patriarchal governance and hand-to-hand combat. When laws in Norway were transmitted orally before the advent of written statutes, the defence of honour required an injured party to personally seek reparations or revenge (Nedkvitne, 2004). In such circumstances, women depended on the muscular dexterity of men to defend their personal or family honour in contests requiring violent combat (Mindrebø, 2021). Women’s exclusion from a male dominance hierarchy, especially given its social importance for defending honour, is likely to have hampered women seeking to exercise long-term political authority.

The limits of bioenergy-dependent childcare

A further constraint on women’s political and military participation can be traced to traditional infant care practices in agrarian societies that were bioenergy-dependent and contact-intensive. Lactating mothers likely kept babies on or close to their bodies, customarily carrying children despite the increased load and musculoskeletal stress (Wall-Scheffler and Myers, 2013). Moreover, based on stable isotope ratios found in bones, recent data reveal that breastfeeding typically lasted two to three years in continental Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean during the Neolithic period (Fulminante, 2015). In Scandinavia, an infant’s proximity to the mother’s body is likely to have been constant and long-term as in much of Europe, thereby placing spatiotemporal constraints on women’s access to state and military institutions.

Spatiotemporal barriers would also arise from higher rates of childbearing (fertility) in agricultural societies than in other kinds of societies. In an investigation of 57 preindustrial societies, 26 foraging and horticultural societies showed average total fertility rates of 5.6 and 5.4 respectively. In contrast, for 31 societies that had adopted intensive agriculture, women on average gave birth to 6.6 children during their lifetimes. The total fertility ratio (TFR) in these societies ranged between 3.5 to 9.9 (Bentley et al., 1993, p. 779). Consequently, women’s political leadership and readiness for armed combat would be constrained by pregnancy, lactation, and maternal infant carrying during most of the early adult years.

Oral culture cements male dominance of the state and military

From the standpoint of coevolving informatics, oral culture is integral to the three-way dynamic underlying male domination of the Norwegian state and military from the Viking Age to the High Middle Ages. This three-way dynamic comprises orality, almost exclusive reliance on bioenergetics, and spatial proximity in virtually all social interaction. In contests for power in agrarian societies, men have a bioenergetic advantage that is normatively elevated and reinforced by oral culture partly because of the spatiotemporal limitations of speech. In oral communication, skeletal muscles transmit vocal sounds exclusively between human bodies that are within hearing distance of each other. Consequently, orality is spatially confined to minds in proximity whereas printed words have an extrasomatic location and distant readership. Because oral societies lack a written record to sustain collective memory, according to Ong (2002, p. 41), they “must invest great energy in saying over and over again what has been learned arduously over the ages.” Unerring repetition to sustain person-to-person flows of cultural information creates a very conservative or traditionalist mindset (Ong, 2002). Cultural conservatism is further reinforced insofar as the confinement of vocal communication to audiences within hearing range subjects both the speaker and supporters to informal community sanctions. This strong and effective type of sanction includes social ostracism, shaming, and ridicule, and sometimes private violence (Posner and Rasmusen, 1999; Francis, 1985). Because repetition and participant proximity are central to muscle-powered communication, primary oral culture is constrained in challenging institutionalized male dominance.

During the formation Norwegian state, orality’s cultural conservatism included repetition of narratives that celebrated men’s heroism in battle. In 12th-and-13th-century written sagas (konungasögur), which distil centuries of oral narratives about Norway’s earliest monarchs and regional chieftains, “there are overall fewer words spent on anyone unable to hold a sword and charismatically lead warriors into battle” (Mindrebø, 2021, p. 8). A key exception would be older men, aged beyond their warrior years, acknowledged for their political power and wisdom. Providing a partial glimpse of agrarian-era culture, 12th-and-13th-century written sagas capture oral narratives that buttress masculine exclusivity in military and political institutions.

In agrarian-era Norway, patriarchal governance was reinforced by flows of cultural information that were entirely dominated by orality. Initially, state power was sustained by laws that were transmitted orally in Thing assemblies in which nearly all vocal participants were men (Nedkvitne, 2004; Sanmark, 2014). Despite the role of schooling and written communication in later consolidating the Norwegian state, oral communication retained supremacy. Literacy was restricted to a small fraction of the elite (Brégaint, 2021). Scandinavian peasants could rely exclusively on person-to-person oral communication insofar as they normally produced for themselves most of what their families consumed or bartered in local markets (Nedkvitne, 2004). At least through the 14th century, royalty depended heavily on the spoken word in official duties as well as in informal communication (Brégaint, 2021). In sum, orality’s meticulously repeated heroic and tradition-sustaining narratives—vocalized within hearing range using the larynx and other muscles—reinforced male dominance of the state and military in agrarian-era Norway.

Women’s military and political participation in the post-agrarian era

Methods

To measure the post-agrarian dynamics which are hypothesized to undergird growth in women’s political and military participation, more than two centuries of data were obtained from the statistical yearbooks of Norway. Spanning 1815 to 2021, these data include the number of women in the national legislature for 62 national election cycles (Statistics Norway, 2000a, 2021). The participation of women in Norway’s armed forces is measured from 1987 to 2021 using mainly NATO data sources (Forsvaret, 2023; NATO, 2023; Palomo et al., 2015; Schjølset, 2013; Stanley and Segal, 1988).Footnote 1 In addition, Norway’s yearbooks were culled for time series indicators regarding learning and communication, spatiotemporal dynamics, and energy conversion. Complete data were available except for mediating or intervening variables (Fig. 1).

To measure Norway’s transformation from nearly exclusive reliance on musculoskeletal power to growing use of electricity, three different period-specific indicators were joined together to measure electrical consumption. For close to a century, in the years from 1930 to 2021, electrical consumption is reported in Norwegian statistical yearbooks in gigawatt hours (GWh) (Central Bureau of Statistics Norway, 1978a; Statistics Norway, 2023a). For the initial transition to electricity between 1896 and 1914, energy consumption can be estimated from the proportion of total horsepower in manufacturing that was generated by electric drive (Venneslan, 2009). Using interpolated values for any missing years, these electric-drive proportions were first converted into estimates of electrical generator capacity. Generator capacity in kilowatts is reported for the years 1914 to 1930 in Norway’s statistical yearbooks (Central Bureau of Statistics Norway, 1920, 1929, 1932). Based on the elective-drive proportion climbing from one percent in 1896 to 80 percent in 1920 (Venneslan, 2009, p. 144), a corresponding proportional adjustment can be made in the generator capacity for years leading up to 1920. Generator capacity can then be converted into estimated gigawatt hours (GWh) based on the ratio of generator capacity to gigawatt hours in 1930. Notwithstanding the absence of precise indicators for the earliest three and one-half decades, electricity consumption in GWh is the sole multi-century measure of energy conversion available in Norwegian statistical yearbooks. Consumption data are spotty for oil, gas, and coal, which are essential contributors to industrial energy conversion. For the data analysis, annual electrical consumption was converted into a per-capita measure, based on the estimated total population for each year (Statistics Norway, 2023b).

Industrial-era, mechanised spatiotemporal dynamics are measured by railway passenger kilometres (Mitchell, 1992) per capita and motorized vehicles per capita. Starting with only two vehicles recorded in 1899, Norway now has a little more than one motorized vehicle per person (Central Statistics of Norway, 1928, 1937, 1978b; Statistics Norway, 2023c). A key limitation of this indicator is that it measures the quantity rather than the everyday use of vehicles. An increasing number of motor vehicles, however, may alter everyday movement more than railways. Neither measure assesses the spatiotemporal impact of mechanized factories and home appliances on women’s careers.

The industrial transition from nearly exclusive reliance on oral communication to increasing use of written communication, especially with letterpress print, can be partially and indirectly measured with data culled from Norwegian statistical yearbooks. Two different period-specific indicators are available. The flow of paper-based text can be indirectly gauged by statistical yearbook data on postal traffic per capita, which is available from 1848 to 1997 (Bureau de Statistique du Ministère de L’intérieur, 1875; Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway, 1949a, 1959; Statistics Norway, 1995, 1998, 2023d). For many of the years, this postal traffic indicator includes printed paper packets, letters, money orders, postcards, newspapers, periodicals, and postal cheques. A more direct and comprehensive indicator, which covers the period from 1992 to 2021, is the minutes expended during an average day for reading periodicals, books, weeklies, and newspapers (Statistics Norway, 2023e). Because this more recent measure spans only three decades and diverges in content from the earlier measure, it is not shown in the graphical analysis but is discussed in the results section.

In the information age, the coevolution of digital information flow, exceedingly portable devices for long-distance communication, and alternative energy conversion can be measured by three indicators respectively. Digital-era spatiotemporal dynamics are at least partially captured by the growing percentage of the population using mobile phones on an average day between 2000 and 2021 (Statistics Norway, 2023f). Estimations of the percentage of the population using mobile phones for an earlier period, between 1980 and 1997, can be derived from per capita mobile phone subscriptions (Statistics Norway, 2000b). The growth of a digital information flow can be measured by the percentage of the population (aged 16–79) with internet access (Statistics Norway, 2023e). For gauging the trend in alternative energy conversion such as wind and solar power, data are available from the International Energy Agency (2023) for 1993 to 2021. More direct measures would have included lithium-ion batteries for powering mobile devices and the use of remote control as key contributors to digital-age energetics and spatiotemporal dynamics.

A major methodological challenge is to measure a shift in the flow of cultural information which, at job-entry level, is reversing Norway’s centuries-old gender gap in human capital (OECD, 2023; World Economic Forum, 2018, pp. 10–11). The reversal of the gender gap arises from trends in formal education at two levels. On the first level of educational advancement is an increase in women’s proportion among students who have completed upper secondary school. These data are comparable for almost two centuries, from 1815 to 1992 (Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway, 1949b, 1978c; Statistics Norway, 2024). On the next level of educational advancement is the growing proportion of university graduates who are women. However, because gender-specific data on university graduates only begins in the 1990s in Norway’s statistical yearbooks, an alternative measure is the proportion of university students who are women (to sustain longitudinal consistency, college students outside universities are excluded from this indicator). For the most recent years, from 1973 to 2021, data from Norway’s statistical yearbooks permit the direct calculation of women’s percentage among university students (Statistics Norway, 2023g, 2023h, 2023i). For 1891 to 1969, when women’s university enrolment was above zero, women’s enrolment percentage could be estimated based on a downward adjustment of women’s proportion among students who complete upper secondary school each year. The downward-adjusting fraction was calculated by dividing women’s proportion among college students in 1973 by women’s somewhat larger proportion among students completing secondary school in 1973. The selection of 1973 was based on this being the earliest year for which available data allowed calculating the adjustment. The adjustment was applied to data that reports Norway’s total number of university students for years preceding the 1970s (Statistics Norway, 2023j). The downward adjustment of women’s proportion among students who completed upper high school from 1891 to 1969 at best estimates the upper bound of women’s university enrolment.

To construct a gender-specific measure of shifting human capital across two centuries, the human capital of women was assumed to increase in proportion to the growth of women’s university enrolment. Although a more commonly used and more comprehensive measure of human capital is educational attainment (Teixeira and Queirós, 2016), annual attainment data for 200 years were unavailable. Consequently, estimates of women’s university enrolment were used to measure sex-specific university-based human capital. The estimates were standardized by dividing by Norway’s population for each year given that the size of the university-age cohort was not reported in the yearbooks.Footnote 2 To facilitate graphical comparisons with other coevolving trends, the measure was then recalibrated by dividing by five.

Methodological limitations arise insofar as the hypothesized coevolutionary relationships are between trends that remain at a zero level for the first half of two centuries and thereafter move mostly upward. A preliminary data analysis showed that the nonstationary error variances, regardless of variable transformations such as first differencing, remain barriers to rigorous statistical analysis. Methodological limitations also arise from the absence of the full range of measures for the hypothesized coevolutionary trends. Consequently, a graphical analysis will provide a data-based overview of the proposed longitudinal relationships, followed by a discussion of evidence supporting causal inferences.

Results

Figures 3–5 show graphical results for measures that were generated by combining, converting, and recalibrating two centuries of data. The time series graphical analysis permits visual inspection of the timing, and therein the plausibility, of the hypothesized connection between coevolutionary trends.

Figure 3 displays industrial-era trends for non-musculoskeletal energy conversion and for the spatiotemporal dynamics of mechanized transport. Notably, both trends show some historical overlap with women’s growing percentage in Norway’s national legislature. Persisting through all 36 election cycles between 1815 and 1918, the invariant pattern is that no women were chosen as fulltime national representatives. In parallel trends, electrical energy consumption and the use of motorized vehicles began a few decades before the first woman entered fulltime into the national legislature (Storting). Railway use begins in the mid-1800s but climbs more steeply around 1906. All upward trends emerge from an invariant zero level over previous centuries.

Regarding the coevolution of literate culture, the historical trends shown in Fig. 4 reveal growth in written communication and women’s formal education. Both trends precede the entry of women into the national legislature. One-half century before the first woman is elected to the Storting, postal service traffic starts expanding from a floor of under one annual delivery per person.Footnote 3 Postal expansion contributes toward written communication being able to augment and sometimes replace orality. Consistent with the hypothesized coevolutionary relationships, mail deliveries per capita continue to grow through national election cycles until the reporting of this statistic ends in the 1990s. In addition, Fig. 4 shows that 50 to 60 years after women’s formal education begins expanding near the end of the 19th century, there is a rise in university-based human capital possessed by women. This increase in human capital closely parallels the entry of women into the national legislature.

Figure 5 reveals digital-era trends that overlap with a contemporary surge in women’s participation in Norway’s parliament and military. Women’s parliamentary representation jumped from 26 percent in 1981 to 45 percent in 2021 (Statistics Norway, 2021). In the combined armed forces, women’s share was only 1.4 percent in 1986–1987, but climbed to 3.2 percent in 2001, 9.7 percent in 2013, and 15 percent in 2021 (Forsvaret, 2023; NATO, 2023; Palomo et al., 2015; Schjølset, 2013; Stanley and Segal, 1988). Accompanying these epochal shifts in four decades, the spatiotemporal dynamics of Norway’s national intercourse were becoming less dependent on physical transport between fixed locations. During 1981–2021, mobile-phone users grew from less than 1 percent (estimate) to 81 percent of the population aged 16–79 (calculations based on Statistics Norway, 2000b, 2023f). Digitalized information began to supplement and sometimes supplant forms of communication and learning that require delivery of printed materials. Between 1997 and 2021, internet users climbed from 2 percent to 93 percent of people aged 16–79. Meanwhile, this age group reduced time spent on magazines, weeklies, and newspapers. From 1992 to 2021, the time expended on reading these printed materials was reduced by 80 percent (calculated from Statistics Norway, 2023e).Footnote 4 Finally, from 1993 to 2021, alternative energy conversion jumped from .0058 to 7.97 gigajoules per capita (International Energy Agency, 2023; Statistics Norway, 2023b).

Overall, the graphical analysis is consistent with the hypothesized coevolutionary relationships. Most striking is the longitudinal overlap of indicators that undergo a dramatic surge after centuries of dormancy. The discussion in the following section will identify specific mechanisms connecting the coevolutionary trends.

Discussion

Women’s military and political participation in industrial and post-industrial eras

Norway’s industrialization creates a new pathway for cultural information flow: mass-produced text for a literate public that is scattered throughout Norway. Mechanized production and delivery of printed text is enabled by industrial-era spatiotemporal dynamics—assembly lines and machine-generated motion—which coevolve with the non-muscular energetics of fossil fuels and electricity. The electromechanical and fuel-powered movement of objects and people is manifested not only in mass-produced literature, but in all areas of industrial society from mechanized mobile warfare to children transported outside the home for schooling (Figs. 1 and 2b). For each of these key features of the industrial era, it is possible to pinpoint new spatial and energetic constraints that both impede and facilitate women’s access to the Norwegian government and armed forces.

On the one hand, gendered life course opportunities and restrictions remain intertwined with childcare (Fawcett, 2023). Women’s career opportunities in Norway have continued to be limited by rigid spatiotemporal boundaries that maintain worksite distance from childrearing locations. Notably, in the early stages of Norway’s industrialization, mostly men shifted from workforce participation in agriculture to the industrial and commercial sector. Consequently, there was a brief period in the first half to middle of the 20th century with men as breadwinners and women as homemakers (Gornick and Meyers, 2008; Knudsen and Wærness, 2001). Domestic work was for most women spatially confined to the home with employment largely divorced from the site of childcare (Chafetz and Hagan, 1996). Up to the present, time expended traveling to and from work has remained a bigger burden and concern for mothers caring for children (Petrongolo and Ronchi, 2020; Silbermann, 2015). This spatial separation of homemakers and breadwinners, which had no precedent in the rural economy, eventually began to erode in the latter part of the 20th century (Gornick and Meyers, 2008).

On the other hand, whereas industrialization impeded women’s careers with new spatiotemporal barriers, women’s career constraints were also reduced with a new information pathway comprising mass-produced print and public education (Fig. 4). Industrial-era fossil fuels and electricity enabled mechanized printing and delivery of written text which can overcome the spatial limitations of larynx-dependent oral communication. The industrial-era’s machine-produced text, at first delivered on horseback, was later distributed more rapidly and over a wider area using fossil-fuel-powered transportation (Behringer, 2006). This newly emerging pathway for cultural information flow—printed text in machine-produced books and articles—fostered growth in human capital that enabled women to be drawn into a white-collar workforce.

Affordable machine-produced literature provides the foundation for mass schooling that eventually extends from elementary schools to universities (Allen, 1991; Davis, 1962). Growth in women’s schooling via mass-produced printed literature provides human capital that is no longer exclusively reliant on apprenticeships under men or informal training within male-dominated sectors of the workforce. The expansion of literacy-based secondary schooling causes skills, initially learned on the job, to become increasingly dependent on a formal education (Goldin and Katz, 1998). Freed from the constraints of orality and an initial emphasis on reading aloud, individuals begin to read silently and alone (Allen, 1991; Venezky, 2002). Women can ponder the meaning of texts without intrusion from authorities or kin. This new channel for cultural information flow provides women with human capital and independence that enable challenging exclusion from state and military participation. Accordingly, formal education becomes a key asset for the women’s movement in Norway (Larsen, 2020; Sass, 2022) and for women pursuing political careers (Gaxie and Godmer, 2007; Iversen and Rosenbluth, 2008).

Women’s human capital increases as mechanization replaces muscle power

Norway’s early development of comprehensive elementary education for both sexes increased latent human capital in the form of reading and writing skills, though the level of formal education remained low (Leknes and Modalsli, 2020). Building on this foundation, formal schooling for both men and women continued to expand in response to specialization in Norway’s industrial energy sources (Figs. 3, 4). The boost that growing energy specialization gave to human capital formation was twofold. On the one hand, reliance on the muscle power of less educated manual labourers was reduced by fossil fuels and electricity. On the other hand, the technical complexity of electrified production increased the demand for workers with skills that are augmented by a formal education and literacy (Venneslan, 2009).

Dependence on muscle power was reduced by the growing contribution of electric drive to total manufacturing horsepower in Norway. This contribution increased from 1 percent in 1896 to 80 percent in 1920 (Venneslan, 2009, p. 144). Greater specialization in energy conversion overcame coal power’s spatial rigidity, which was linked to jobs requiring low human capital. Electric motors for individual machines could replace coal-powered arrays of centrally driven shafts and pulleys (Goldin and Katz, 1998; Devine, 1983). The spatial dispersal and portability of electric motors reduced the need for muscle power to move work on the factory floor. Men pushing handcarts and carrying heavy loads could be replaced by conveyor belts and overhead cranes (Nye, 1990). This shift away from “brute work” (Nye, 1990, p. 15) was in the U.S. accompanied by increased demand for white-collar labour with a high-school education (Goldin and Katz, 1998).

Because of shortages in the Norway’s market for white-collar labour, there was increasing demand for women workers, including those who were married (Chafetz and Hagan, 1996). Between 1896 and 1920, growth in demand for women’s labour was concomitant with the tripling of the proportion of the manufacturing workforce that was classified as white collar (Venneslan, 2009, p. 140). As industrialization proceeded, women’s labour overcame its initial concentration in a few light manufacturing/service jobs—clerical, secretarial, retail—mostly before marriage. Later, between 1960 and 1990, when service occupations in Norway expanded 235 percent, there was a corresponding 185 percent increase in women’s employment (Chafetz and Hagan, 1996, p. 190). One significant consequence is that within the expanding service sector, women educated beyond high school were attracted to the electronics-age workforce by both higher wages and intrinsically rewarding work (Chafetz and Hagan, 1996).

The late-19th-century timing of growth in women’s human capital can be understood, in part, from the growing importance of literacy and formal schooling for a mechanized industrial economy. Most notably, as late as the first three quarters of the nineteenth century, women had been blocked from higher levels of education. This gender barrier was reinforced by the cultural belief that girls were not as intellectually capable as boys (Rust, 1989). Girl’s schools in Norway did not receive state funding until 1896, when government funding to private and public schools was made contingent on the absence of discrimination based on sex (Rust, 1989, p. 138). In 1882, path-setting legislation was adopted that permitted women to attend the upper level of secondary school, and then, in 1884, women were able to qualify for university study (Heffermehl, 1972, p. 630). In this early period, between 1880 and 1890, about one fifth of middle school graduates were women (Rust, 1989, p. 139). By the 1890s, only 8 percent of those passing the exam that permits university entrance (artium examen) were women. However, by the late industrial era, in 1975, more girls were passing the university entrance exam than boys (Rust, 1989, pp. 140, 255). The recent timing of this reversal coincides with industrial society’s growing demand for mass education, relying on affordable machine-produced texts. Women’s comparative advantage in human capital is dramatically boosted as part of 20th-century shifts in mechanization and electrification, setting the stage for women pursuing military and government careers.

Industrial-era spatiotemporal and energetic constraints on women in warfare

The industrial age has also reduced energetic and spatiotemporal constraints on women’s military participation. Female soldiers emerge globally when hand-to-hand combat is displaced by energy outside the body, such as with gunpowder and fossil fuels, and when long-distance information flow (radio, telephone) permits launching attacks far from targets. This increase in distance is partly enabled by gunpowder technology that emerges much earlier in fourteenth century Europe. Insofar as modern rifles can strike an enemy at 500 yards or more, hand-to-hand combat becomes infrequent (Grossman, 1995). The distance between soldier and target is also increased by industrial-age mobile and mechanized warfare (Watson, 1993). Warfare not requiring close-quarters, hand-to-hand combat reduces the male advantage over women regarding strength, height, lung capacity, and amount of oxygen-carrying haemoglobin.

The entry of women into the Norwegian military is delayed until a series of government directives are issued (Rones, 2015b) at the dawn of the information revolution (Fig. 5). Near the forefront of post-war global trends, Norway’s armed forces reversed their policy of barring women in the 1970s. Two decades prior to this transformation, in 1957, the Norwegian parliament had passed a law allowing women to be employed in defence activities, but only as civilians (Heffermehl, 1972, p. 645). In 1977 women were for the first time given access to some noncombat jobs in the military. Soon thereafter, in 1985, Norway adopted a law giving women equal access to the armed forces that included entry into all combat positions. Notably, Norway led most other countries in welcoming its first female helicopter pilot, submarine commander, and jet fighter piolet in the early 1990s (Loukou, 2020; Straits Times, 2016). In the late industrial era, as mechanized combat and long-distance communication continued to change the nature of war, government directives allowed women to gain greater access to Norway’s armed forces.

Yet cultural, spatial, and bioenergetics constraints remain for women in the industrial-age Norwegian military. Consistent with cultural norms inherited from Norway’s agrarian past, a barrier to the recruitment and retention of women may be partly anchored in the military’s traditional masculine ideal: the outdoorsmen having natural ability to cope with Norway’s rough terrain and harsh climate (Rones, 2015a, 2015b; Rones and Fasting, 2017). Undoubtedly, competent use of modern military equipment and technology is becoming more dependent on “brainpower” and less dependent on the individual soldier’s physical capacity (Kümmel, 2002). Yet masculine physical qualities such as hauling a heavy backpack and walking long distances have been used as measures of military proficiency in Norway (Rones, 2015a, 2015b).

Bioenergetics barriers have also trumped women’s recruitment into the Norwegian Special Operations Command (NORSOC) elite paratrooper platoon (the Fallskjermjegertroppen). This elite platoon has been open to women since the late 1980s. However, despite the successful performance of female soldiers as pilots and submarine commanders, women have not successfully competed with men in the physically demanding NORSOC training for paratroopers. Consequently, an alternative avenue for women to perform military service in special forces, the Jegertroppen (the Hunter troop), opened exclusively for women in 2014 (Steder and Rones, 2019).

Spatiotemporal barriers continue to deter women with new-born and younger children from becoming soldiers. Mothers in combat positions who want to breastfeed have not been assured regular pumping times. There is no place to store breast milk for an extended period or a way to transport the milk to the infant (Stevens and Janke, 2003). In addition, rigorous military training and travel require geographic mobility, inflexible schedules, and periodic separation from the family. Because of these largely spatiotemporal constraints on family life, the Norwegian military continues to create a work-life imbalance for women with young children.

Constraints arising from maternity and domesticity in industrial society

In industrial Norway, the spatial separation of employment from domesticity both impedes and facilitates women’s political and military participation. In the government, as in the military, one key spatiotemporal constraint on mother’s careers is the separation of worksites from childrearing locations. Most contemporary workplaces are not in the home, whether in Norway or in other developed countries such as Canada (Donnan, 2008). Worksite separation from childrearing locations is compounded by inflexibly long work hours for political and military leaders, as indicated by evidence from nearby countries that are like Norway. For example, one survey found that over 92 percent of British MPs work over 50 hours per week, and 41 percent work 70 hours per week or more (Flinders et al., 2020, p. 256). The politician’s time away from home could explain why more women than men drop out of politics in Sweden’s municipal councils. The family situation is reported as the cause of dropping out for one third of women compared to one quarter of men (Sevä and Öun, 2019, p. 368). Moreover, government career disruptions for women who are caring for young children result in the depreciation and non-accumulation of human capital (Rønsen and Kitterød, 2015). Politicians accumulate political capital early in their careers, precisely when women interrupt their advancement in the workforce to rear young children (Fiva and King, 2024; Iversen and Rosenbluth, 2008). Given this work-life balance constraint for women, it is not surprising that a survey of 647 British MPs in 2013 found that 45 percent of female MPs have no children compared to 28 percent of male MPs (Campbell and Childs, 2014, p. 488). A recent study shows that Norwegian municipalities which hold some or all council meetings at night have less local representation by young mothers (age 18–40) than municipalities with meetings only in the daytime. No comparable municipal difference is found for childless women in this age group (Fiva and King, 2024). Ultimately, spatiotemporal constraints imposed by childcare hamper government and military participation more for women than for men.

On the other hand, industrialism’s manufacture of goods outside the home has eased physiological exertion and bioenergy dependence for maternity and domesticity, allowing more women to work in time-inflexible jobs. For example, career-disrupting hospital stays arising from post-partum debilitation were reduced because of production of sulphonamides, first synthesized in 1932 (Jayachandran et al., 2010). Since the 1920s, mass-produced infant formula (Albanesi and Olivetti, 2016) has reduced contact-intensive childcare by shortening breastfeeding time. Later enhancements to women’s mobility came from home appliances (Greenwood et al., 2005) and, in 1960, the introduction of oral contraception (Bailey, 2006). In sum, goods made outside the home, along with mechanization and electrification, have reduced women’s reliance on contact-intensive bioenergy for house cleaning, bearing children, and breast feeding. Consequently, women are less constrained when pursuing time-demanding careers.

In addition, increasing education requirements for Norway’s industrial workforce promotes lifestyles that reduce the spatiotemporal constraints of childbearing. The average number of children in a Norwegian women’s lifetime, which was 4.32 in 1800 and 4.4 in 1900, dropped precipitously to 1.78 in 1934 (GCDL, 2017). Twentieth-century rates subsequently remained at a lower level than in the 1800s, although the total fertility ratio rose to 2.96 in 1964 before declining again (GCDL, 2017; World Bank, 2022). It is likely that over the long run, the declining fertility rate in Norway reflects rising opportunity costs for staying home to care for children. The loss of income and intrinsic rewards is greater for women who forgo jobs that require more human capital (Chafetz and Hagan, 1996). Although these opportunity costs have been lowered by Norway’s work- and family-related policies (Kornstad and Rønsen, 2018), a negative but weakened educational gradient remains in Scandinavian countries (Merz and Liefbroer, 2018). The evidence strongly suggests that through direct and indirect effects that have lowered fertility rates, industrialism’s demand for a more educated workforce has reduced barriers for women seeking government and military jobs.

Mechanized printing and formal education reduce the constraints of oral culture

Industrial-era printing has generated a distinct extrasomatic pathway for information flow. One manifestation of this new pathway is an expanding postal delivery system (Fig. 4). Mass-produced books and articles can be distributed across multiple distant locations simultaneously, overcoming the larynx’s bioenergy dependence and the ear’s hearing-range limitations. In addition, printing faithfully reproduces identical information for large numbers of people (Nedkvitne, 2004). Faithful reproduction occurs without memorization or unerring repetition of previously established narratives. A new form of diachronic, long-distance communication is possible because printed words appear in a long-lasting visual field outside the human body, unlike vocal sounds that permeate both speaker and listener and then disappear (Ong, 2002).

Challenges to patriarchal governance are enabled by printed literature as a new extrasomatic pathway for cultural information flow. By providing a spatial location outside the mind for breaking apart, analysing, and then storing what is known, print “downgrades” oral “repeaters of the past” (Ong, 2002, p. 41). Primary oral cultures of agrarian societies continually repeat the wisdom of the past, including patriarchal norms, because there is no place for storage of information outside the listener. In contrast, more impersonal, evidence-based analysis within print culture allows a re-evaluation of gender-reproducing oral traditions.

In Norway the “epoque of the housewife,” roughly from 1900 to 1960 (Sass, 2022), was countered effectively by a growing stream of scholarly publications. Especially prominent in this regard was the Norwegian Institute of Social Research (ISF), established in 1950 (Larsen, 2020, p. 154). Institute academicians Harriet Holter and Erik Grønseth became leaders in Nordic gender studies. Holter’s coedited book Women’s life and work (Dahlström et al., 1962), which analysed sex-order reorganization, sold out when first published jointly in Norway and Sweden (Larsen, 2020, p. 155). As a sex-role specialist, Holter influenced the content of other important publications, such as a Labour Party pamphlet titled “The woman’s place—where?” (Gerhardsen, 1965). The pamphlet also reflected the work of a University of Oslo professor, Åse Gruda Skard, who in 1953 had published Women’s issues: act three (Larsen, 2020, pp. 157-158; Skard, 1953). The pamphlet’s subject matter included steps to increase women’s political power. Considering these goals were distributed in print, the Labour Party was obliged to comply with the women’s movement campaign for more women in local councils. In 1967, this cross-party campaign increased women’s share of the elected local-council representatives by 50 percent (Halsaa, 2024, p. 144). The evidence suggests that more women in the state, state feminism (Hernes, 1987), and the 1970s revolution that redirected women’s identities toward careers (Goldin, 2006) were closely linked with scholarly writing and its use by the women’s movement.

Owing to the expansion of formal schooling, which partly reflects the industrial-era’s mass-production of books and articles, highly educated women have been predominant among activists challenging Norway’s gendered state. Teachers were prominent among early activists. For example, the founding leader of the Female Teachers Association (Anna Rogstad) was selected in 1911 as a deputy (backup) representative, becoming the first woman in Norway’s national legislature (Sass, 2022). Since 1922, women with a university degree or background as a teacher have accounted for more than three quarters of the presidents of the Norwegian Association of Women’s Rights (calculated from Wikipedia, 2022). This activist organization is part of a women’s movement that has pushed successfully for legislation such as the 1978 law making abortion a civil right (van Der Ros, 1994). Women’s organizations also pushed for coeducation and curriculum changes that advanced gender equality, and by 1974 “housewife ideology” was largely gone (Sass, 2022). Between 1960 and 1980, the Secretariat for Feminist research was decisive in channelling expert scholarship toward the interpretation and implementation of women-friendly welfare state policies (Larsen, 2020).

Globally, women who have fought for hiring equality, promotions, and day-care facilities have tended to be highly educated (Chafetz and Hagan, 1996). Indeed, in the suffrage movements emerging worldwide before WWII, leaders and rank-and-file members of women’s organizations were largely educated, urban, and middle-class women (Paxton and Hughes, 2016). In sum, the political leverage of women has been elevated by industrial-age print culture and the corresponding growth in the proportion of women among graduates of secondary and tertiary educational institutions.

Women’s access to the state and military in the digital era

Norway’s transition to a knowledge economy is creating a distinctive pathway for the flow cultural of information. Whether this flow is halfway around the globe or local, multisite information exchanges and data processing occur instantaneously on rapidly expanding digital and computerized networks. Moreover, the knowledge economy is generating a learning-centred culture. This culture is based on intellectual capital and on research by university-trained professionals. Instantaneously transmitted, learning-centred culture is coevolving with specialization in high-tech energy conversion (e.g., solar, lithium-ion, etc.), further reducing reliance on muscle power (Fig. 5). Accordingly, gendered spatiotemporal and energetic dynamics are being transformed by AI-assisted robotic production, cyber warfare, lifelong education from infancy onward, and hyperlinked global data networks (Figs. 1 and 2c).

Specifically, increased reliance on non-muscular, social-cerebral skills is reducing industrialism’s worksite constraints on women’s employment. The digital era’s focus on communication and research rather than on manual labour permits university-trained professionals to work far from the factory floor (Temple, 2012). Underlying this shift away from the factory’s spatial dynamics, intellectual capital in the post-industrial economy is supplanting physical capital (Švarc and Dabić, 2017; Powell and Snellman, 2004; Brown et al., 2008). Accordingly, tertiary educational institutions, which graduate more women than men in Norway and in all 38 OECD countries (OECD, 2023), are becoming a key driver for economic productivity (Bejinaru, 2017; Temple, 2012). The expansion of knowledge-intensive industries is enlarging the pool of well educated, professional women that provides many politicians (Gaxie and Godmer, 2007; Iversen and Rosenbluth, 2008). As women move from local representation to holding higher national offices in Norway’s political system, the educational attainment advantage of women widens relative to men when occupying the same political office (Fiva and King, 2024). The knowledge economy requires “brain skills” which demand more intensive use of communication and interpersonal abilities for which women have a comparative advantage (Ngai and Petrongolo, 2017).

As the knowledge economy began emerging in the 1970s, a “quiet revolution” was transforming the identities of women from being household-centred to more career-oriented. Paid work became a source of life satisfaction rather than merely a job (Goldin, 2006). Women increasingly pursued professional careers such as law, once monopolised by men (Michelson, 2013). Cross-national analyses reveal that university-trained professionals constitute a pipeline to holding political office (Kenworthy and Malami, 1999; Viterna et al., 2008), partly because of the high status, contacts, and public-speaking experience of some professionals (Norris and Lovenduski, 1995; Thomsen and King, 2020). Many women candidates for Norway’s parliament listed their occupations as “housewives” in the early 1900s, whereas today professional careers are common (Fiva and King, 2024). In addition, growing competitiveness of non-military career options prompted the military to officially recruit women and provide officer training in the 1970s. These policy shifts compensated for a shortage of both military manpower and female volunteer labor that had been relied upon since WWII (Ahlbäck et al., 2024). Also contributing to the quiet revolution in the 1970s was a global women’s movement which promoted gender quotas (Paxton et al. 2006). In the mid-1970s, Norway began incorporating such quotas into military recruitment goals (Ahlbäck et al., 2024) and into candidate lists for political parties (Fiva and King, 2024).

Constraints on women in warfare

In the digital era, gender-role and musculature-based restrictions on women’s military service are apparently receding as more women are recruited into Norway’s armed forces. The Norwegian Ministry of Defence (White paper 14, 2012–2013) has prioritized a range of competencies in addition to the traditional physical fitness thresholds that create greater difficulty for women than for men (Rones, 2015b, p. 184). In 2015, Norway introduced universal conscription regardless of gender (Forsvaret, 2021). By 2019, women comprised 14 percent of the army, 13 percent of the air force, and 12 percent of the navy (NATO, 2023). In 2021, 15.0 percent of all military personnel (Forsvaret, 2023, p. 2) and 34.5 percent of conscripts in the Norwegian armed forces were women (Forsvaret, 2022) (Fig. 5). Norway has established mixed-gender combat units, such as the Norwegian air defence battalion of the 138th Air Wing, which was half female in 2015 (Hellum, 2017; Loukou, 2020).

Twenty-first-century Norway is restructuring its military into a professionalized, gender-neutral “rapid reaction” force, partly in response to globalization (Rones, 2015b; White paper 14, 2012–2013). Global pressures toward professionalization are linked to the spatial dynamics and high-tech energetics of modern warfare. The digital-age military has prioritized a transition toward computerization and information networks in which wireless energy transfer systems may play a critical role (Saritas and Burmaoglu, 2016). In the future, soldiers will be increasingly supervising at the highest level of knowledge-based cognitive control, allowing human energy-conversion problems of fatigue to be overcome (Cummings, 2021). Moreover, frontline combat increasingly requires technical sophistication. Proportionally fewer military careers include physically demanding activity in the infantry because most soldiers are now support personnel (Kennedy‐Pipe, 2000). Women’s disadvantages in upper-body strength or carrying heavy backpacks become less important as non-kinetic warfare and cyberwar become more prominent. In fact, because Norway is among the most digitalized countries in the world, cybersecurity is a top concern in terms of the country’s threats and risks (Gjesvik, 2021). Accordingly, the Norwegian Armed Forces Cyber Defence (NAFCD) was inaugurated in 2012 with a key focus on ICT technology. In addition to defending physical space, the Norwegian armed forces now protect a “cyber dimension” or digital space created by computers and information networks (Boe and Torgersen, 2018; White paper 14, 2012–2013). Because the resulting information flows operate outside the muscular energetics and rigidly bounded spatial dynamics of close-range combat conducted on foot, constraints on women’s military careers are further reduced.

The reduction of childcare constraints in the information age

The growth of learning-centred culture in post-industrial Norway contributes toward less rigidly bounded spatiotemporal dynamics for infant socialization. Education-oriented day-care facilities, allowing mothers to work outside the home, initially were expanded in Norway to get children ready for school (Leira, 1992; Sörensen and Bergqvist, 2002; Rindfuss et al., 2010). Implementing a “lifelong learning” strategy promoted by the European Union (Ellingsæter and Gulbrandsen, 2007), the Norwegian government subsidized day-care so that it is affordable and accessible (Rindfuss et al., 2010). In 1975, the Daycare Act was passed, after more than a decade of agitation by the women’s movement for childcare provisions (Leira, 1992). By 2010, kindergartens were providing education-oriented daycare for almost 80 percent of 1- to 2-year-old children (Rønsen and Kitterød, 2015, p. 82). During the period in which day-care was being expanded, the employment rate for women with young children climbed as well, reaching 82 percent in 2010 among mothers in couples with children between ages 1–2 (Rønsen and Kitterød, 2015, p. 62). This trend suggests that learning-centred culture, generated in knowledge economies, is reducing career barriers for mothers with young children.

Learning-centred culture and a corresponding increase in women’s human capital are also likely to be contributing to reduced fertility, diminishing a key cause of career interruption for women. Nearly two thirds (64.9 percent) of Norwegian women aged 25–34 are now entering the job market with a tertiary-level education (OECD, 2023). This proportion is significant because women with more rather than less education, up until recent times (Jalovaara et al., 2019), have been more likely to postpone childbirth and have fewer children to pursue career opportunities (Roser, 2014). The negative impact on fertility is consistent with higher pay and more intrinsic rewards for jobs that require higher education levels (Chafetz and Hagan, 1996). Accordingly, Norway’s total fertility ratio (TFR) dropped from a high of 2.96 in 1964 to a low of 1.7 in 1980. After 1987, the TFR rose moderately to a new high of 2.0 in 2009 and subsequently declined to a new low between 1.5 and 1.6 in 2019, 2020, and 2021 (World Bank, 2022). The consistently low post-industrial TFR in Norway, which in all likelihood is partly attributable to increasing human capital for women, reduces childcare constraints on women’s careers.

Overcoming constraints of regional political representation

The industrial-era system of government in Norway prioritized political representation for regions rather than for constituencies such as women. This spatial prioritization was partially jettisoned between 1974 and 1993, when the major political parties adopted quotas for women in Norway’s proportional representation system. These quotas greatly increased the number of women elected to parliament. Accordingly, women in Norway’s post-industrial state typically occupy 40 percent or more of parliamentary seats, which compares favourably to an average of only 28 percent for the European Union in 2015 (Fiva and Smith, 2017, p. 1380). In Norway, the adoption of quotas has been particularly effective in the political sphere (Kjeldstad, 2001).

Microprocessors and learning-centred culture

The instantaneous long-range transfer of information through the internet and satellites enables government officials and soldiers, including mothers with young children, to conduct many transactions remotely. Portable fingernail-sized microprocessors and the rapid expansion of wireless transmission on the World Wide Web (Fig. 5) are increasingly permitting instantaneous communication between computers regardless of their location (Fig. 2c). Hypertext links are permitting access to spatiotemporally “disembedded” or location-free information, which eliminates time-consuming searches through semiportable, paper-based periodicals, books, or libraries (Fuchs, 2008, p. 314; Dewar, 2000). Ultimately, digital information flow enables the boundaries of spatiotemporal “locality” to be surpassed (Kirkebø et al., 2021). In this way, information flowing through computers and digital networks worldwide is narrowing industrialism’s home-worksite gap.

As university-trained professionals become more central to the knowledge economy, universities worldwide are reversing an enduring gap in human capital that is among many barriers to women’s entry into professional careers. Most countries currently show women outnumbering men in college. Specifically, this dominance of women among university students has been reported for 96 out of 137 countries with data on tertiary-institution enrolment broken down by gender (World Economic Forum, 2018, pp. 10-11). Reinforced by this recent educational trend, women’s comparative advantage in job competition is enhanced by growth in labour-market returns for cognitive skills and decreasing returns for motor skills (Bacolod and Blum, 2010; Blau and Kahn, 2017). Moreover, among 115 countries and dependent territories, the participation of women in higher-education STEM programs has grown so women now constitute more than one third of program enrolments (UNESCO, 2017, p. 11). In Norway women constituted 60 percent of tertiary-education graduates in 2015 (Borgonovi et al., 2018, p. 11). As noted earlier, higher education contributes toward success in political careers (Gaxie and Godmer, 2007; Iversen and Rosenbluth, 2008). Ultimately, women’s career-limiting constraints are being reduced by a learning-centred knowledge economy and by instantaneous, digitalized exchanges of information.

Conclusion

A data-based synthetical methodology provides an avenue for exploring why a millennium-old male monopoly on the Norwegian state and military is now eroding. A vast multidisciplinary literature analyses pieces of the puzzle. A synthetical approach is needed to put the pieces together. Although some influences remain unmeasured, key structural shifts have been revealed by synthesizing multidisciplinary findings and quantifying trends over the last two centuries.

In agrarian-era Norway, women’s participation in state and military institutions was limited by dependence on oral communication, spatial proximity in virtually all social interaction, and reliance on muscle power. Later, in the industrial era, these interconnected constraints on women’s political and military participation began to erode. Yet growing depth in cultural information flows from literacy and schooling, coevolving with industrial-era mechanization and electrification, did not overcome a gender gap in human capital. Moreover, time-inflexible employment and a home-worksite gap continued to hamper women’s political and military careers.

Deepening cultural information flow underlies tectonic political and economic shifts. In Norwegian politics, scholarly research and mass-produced literature wielded by the women’s movement contributed to trend-setting state-provisioned daycare and gender-balancing quotas. As Norway transitions to an information-age economy that features increasingly specialized high-tech energetics, constraints on women’s access to Norway’s government and armed services are further eroded. Women’s comparative advantage in political and military careers has been enhanced by growth in labour-market returns for cognitive skills and decreasing returns for motor skills. With the growing reliance of the knowledge economy on information transmitted through tertiary education, human capital is expanding more rapidly for women than for men. In addition, the home-worksite gap that had disadvantaged women is narrowing as microprocessors expand instantaneous information exchange. In broad perspective, women’s comparative advantage has increased with growing depth in cultural information pathways.

In conclusion, coevolving informatics links three key processes: increasing depth in cultural information flow, social evolution toward less rigidly bounded spatiotemporal dynamics, and greater specialization in energy conversion. Based on the coevolution of these three dynamics, women’s access to state and military institutions in Norway is enabled by increasing depth of cultural information flows. Depth increases with the addition of more expansive and high-speed pathways for the generation, transfer, and storage of cultural information. The most basic pathway is oral communication, later followed by mass-produced literature and computer-dependent, knowledge-intensive networks. The additional information pathways are creating a more learning-centred global culture, which multidisciplinary evidence suggests is contributing to altering the gender balance of the Norwegian state and military.

Data availability

All data compiled for this study are available in a supplementary information file.

Notes

A cautionary note regarding these data is that although the NATO Committee on Gender Perspectives (NCGP) has standardized the collection procedure since 2002, researchers have no means of cross-checking for data accuracy and comparability over time (Schjølset, 2013).

The number of female university students was calculated based on annual estimates of women’s proportion among the total number of university students.

Between 1992 and 2021, the average time for reading magazines, weeklies, and newspapers fell from 51 minutes to 10 minutes per day. To reduce clutter, this trend is not shown in Fig. 5. The average time for reading books remained approximately 14 minutes per day. Books, weeklies, and magazines in the tabulations were exclusively printed on paper.

References

Ahlbäck A, Sundevall F, Hjertquist J (2024) A Nordic model of gender and military work? Labour demand, gender equality and women’s integration in the armed forces of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Scand. Econ. Hist. Rev. 72(1):49–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/03585522.2022.2142661

Albanesi S, Olivetti C (2016) Gender roles and medical progress. J. Polit. Econ. 124(3):650–695. https://doi.org/10.1086/686035

Allen JS (1991) In the public eye: a history of reading in modern France, 1800-1940. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey

Bacolod MP, Blum BS (2010) Two sides of the same coin: U.S. ‘Residual’ inequality and the gender gap. J. Hum. Resour. 45(1):197–242. http://jhr.uwpress.org/content/45/1/197.abstract

Bagge S (2010) From Viking stronghold to Christian kingdom: state formation in Norway, c. 900-1350. Museum Tusculanum Press, Copenhagen

Bailey MJ (2006) More power to the pill: the impact of contraceptive freedom on women’s lifecycle labor supply. Q J. Econ. 121(1):289–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/121.1.289

Behringer W (2006) Communications revolutions: a historiographical concept. Ger. Hist. 24(3):333–374. https://doi.org/10.1191/0266355406gh378oa

Bejinaru R (2017) Universities in the knowledge economy. Manag Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 5(2):251–271. https://www.managementdynamics.ro/index.php/journal/article/view/213

Bentley GR, Jasienska G, Goldberg T (1993) Is the fertility of agriculturalists higher than that of nonagriculturalists? Curr. Anthropol. 34(5):778–785. https://doi.org/10.1086/204223

Blau FD, Kahn LM (2017) The gender wage gap: extent, trends, and explanations. J. Econ. Lit. 55(3):789–865. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20160995

Boe O, Torgersen G-E (2018) Norwegian “digital border defense” and competence for the unforeseen: a grounded theory approach. Front Psychol 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00555

Bohannon RW (1997) Reference values for extremity muscle strength obtained by hand-held dynamometry from adults aged 20 to 79 years. Arch. Phys. Med Rehabil. 78(1):26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90005-8

Borgonovi F, Ferrara A, Maghnouj S (2018) The gender gap in educational outcomes in Norway. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/f8ef1489-en

Brégaint D (2021) Kings and aristocratic elites: communicating power and status in Medieval Norway. Scand. J. Hist. 46(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2020.1784267

Brown P, Lauder H, Ashton D (2008) Education, globalisation and the future of the knowledge economy. Eur. Educ. Res J. 7(2):131–156. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2008.7.2.131

Bureau de Statistique du Ministère de L’intérieur (1875) Table 24. Poste. Résumé de renseignements statistiques sur la Norvége. Th. Steen, Christiana, p 52. https://www.ssb.no/a/histstat/aarbok/annuaire_1875.pdf

Campbell R, Childs S (2014) Parents in parliament: ‘where’s mum?’. Polit. Q 85(4):487–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12092

Carneiro R (2012) The circumscription theory: a clarification, amplification, and reformulation. Soc. Evol. Hist. 11:5–31. https://www.socionauki.ru/journal/files/seh/2012_2/005-030.pdf

Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway (1920) Table 43. Usines d'électricité au 31 décembre 1917. Annuaire statistique de la Norvège 1919. I Kommisjon Hos H. Aschehoug & Co., Kristiana, p 52. https://www.ssb.no/a/histstat/aarbok/1919.pdf

Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway (1928) Table 87. Nombre des automobiles, motocyclettes et courses des automobiles 1913-1927. Annuaire statistique de la Norvège 1928. I Kommisjon Hos H. Aschehoug & Co., Oslo, p 85. https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/statistisk-arbok-for-kongeriket-norge-1928

Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway (1929) Table 71. Usines d'électricité au 31 décembre 1927. Annuaire statistique de la Norvège 1929. I Kommisjon Hos H. Aschehoug & Co., Oslo, p 69. https://www.ssb.no/a/histstat/aarbok/1929.pdf

Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway (1932) Table 75. Usines d'électricité au 31 décembre 1927. Annuaire statistique de la Norvège 1931. I Kommisjon Hos H. Aschehoug & Co., Oslo, p 81. https://www.ssb.no/a/histstat/aarbok/1931.pdf

Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway (1937) Table 113. Nombre des automobiles, motocyclettes et courses des automobiles 1915-36. Annuaire statistique de la Norvège 1937. I Kommisjon Hos H. Aschehoug & Co., Oslo, p 107. https://www.ssb.no/a/histstat/aarbok/1937.pdf

Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway (1949a) Table 152. Number of permanent post-offices. Pieces of mail sent. Statistical survey 1948. 1 Kommisjon Hos H. Aschehoug & Co., Oslo, p 41. https://www.ssb.no/a/histstat/hs1948.pdf

Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway (1949b) Table 208. Secondary schools with rights of examination. Statistical survey 1948. 1 Kommisjon Hos H. Aschehoug & Co., Oslo, pp 383-384. https://www.ssb.no/a/histstat/hs1948.pdf

Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway (1959) Table 137. Postal service. Number of permanent post-offices. Pieces of mail sent. Statistical survey 1958. Oslo, p 130. https://www.ssb.no/a/histstat/hs1958.pdf

Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway (1978a) Table 145. Consumption of electricity, by consumer group. GWh. Historical statistics 1978. Oslo, p 243. https://www.ssb.no/a/histstat/hs1978/hs1978.pdf

Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway (1978b) Table 219. Motor vehicles. Historical statistics 1978. Oslo, p 428. https://www.ssb.no/a/histstat/hs1978/hs1978.pdf

Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway (1978c) Table 352. Graduates from secondary general schools, upper stage. Historical statistics 1978. Oslo, p 623. https://www.ssb.no/a/histstat/hs1978/hs1978.pdf

Chafetz JS, Hagan J (1996) The gender division of labor and family change in industrial societies: a theoretical accounting. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 17(2):185–219. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.27.2.187

CIA (2024) World leaders—historical data. Online directory of world leaders and cabinet members of foreign governments. Last updated 19 April 2024. https://www.cia.gov/resources/world-leaders/historical-data/. Accessed 18 June 2024

Cummings MLM (2021) The human role in autonomous weapon design and deployment. In: Galliott J, MacIntosh D, Ohlin JD (eds) Lethal autonomous weapons: re-examining the law and ethics of robotic warfare. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 273-288

Dahlström G, Dahlström E, Thyberg S, et al. (1962) Kvinnors liv och arbete: svenska och norska studier av ett aktuellt samhälls problem. Studieförbundet Näringsliv och Samhälle [SNS], Stockholm

Danneskiold-Samsøe B, Bartels EM, Bülow PM et al. (2009) Isokinetic and isometric muscle strength in a healthy population with special reference to age and gender. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 197(s673):1–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02022.x

Davis O (1962) Chapter ii: textbooks and other printed materials. Rev. Educ. Res 32(2):127–140. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543032002127

Devine WD (1983) From shafts to wires: historical perspective on electrification. J. Econ. Hist. 43(2):347–372. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700029673

Dewar JA (2000) The information age and the printing press: looking backward to see ahead. Ubiquity 2000(August). https://doi.org/10.1145/347634.348784

Donnan ME (2008) Making change: gender, careers, and citizenship. In: Siltanen J, Doucet A, Gender relations in Canada: intersectionality and beyond. University Press, Oxford, 134-171. https://archive.org/details/genderrelationsi0000silt/mode/2up

DSS (2013) Ministry of Defense - minister of state. Reggeringenno. The Ministries’ Security and Service Organization. Last Modified 17 Oct 2013. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/om-regjeringa/tidligere-regjeringer-og-historie/ks/dep/6-departementforsvarsdepartementet-1885-/id426227/. Accessed 17 Feb 2023

Ehrenreich B (1997) Blood rites: origins and history of the passions of war, 1st edn. Metropolitan Books, New York

Ellingsæter AL, Gulbrandsen L (2007) Closing the childcare gap: the interaction of childcare provision and mothers’ agency in Norway. J. Soc. Policy 36(4):649–669. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279407001225

Ellis L (2008) Sex differences: summarizing more than a century of scientific research. Psychology Press, New York

Fawcett B (2023) Feminisms in social work and social care: backwards, forwards or something in between. Int Soc. Work 66(3):831–841. https://doi.org/10.1177/00208728221095962

Ferrill A (1997) The origins of war: from the Stone Age to Alexander the Great, revised edn. History and warfare. Westview Press, Boulder, CO

Fischer-Kowalski M, Krausmann F, Pallua I (2014) A sociometabolic reading of the Anthropocene: modes of subsistence, population size and human impact on Earth. Anthr. Rev. 1(1):8–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019613518033

Fiva JH, King MM (2024) Child penalties in politics. Econ. J. (Lond.) 134(658):648–670. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/uead084

Fiva JH, Smith DM (2017) Norwegian parliamentary elections, 1906–2013: representation and turnout across four electoral systems. West Eur. Polit. 40(6):1373–1391. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1298016

Flinders M, Weinberg A, Weinberg J et al. (2020) Governing under pressure? The mental wellbeing of politicians. Parliam. Aff. 73(2):253–273. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsy046

Foley G, van Buren A (1982) Energy in the transition from rural subsistence. Dev. Policy Rev. A15(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.1982.tb00319.x

Forsvaret (2021) Our history. Norwegian Armed Forces. Last Modified 8 Oct 2021. https://www.forsvaret.no/en/about-us/our-history

Forsvaret (2022) Armed forces in numbers. Norwegian Armed Forces. https://www.forsvaret.no/en/about-us/armed-forces-in-numbers

Forsvaret (2023) Forsvarets likestillings-redegjørelse 2022. https://www.forsvaret.no/aktuelt-og-presse/publikasjoner/forsvarets-arsrapport/(U)_Likestillingsredegjorelse_Forsvaret_2022.pdf/_/attachment/inline/255840b3-e987-4ea9-ae9c-435ab2585ee5:e9669be3f9fe5357a1196d4a490ac898ec5fc552/(U)_Likestillingsredegjorelse_Forsvaret_2022.pdf

Francis H (1985) The law, oral tradition and the mining community. J. Law Soc. 12(3):267–271. https://doi.org/10.2307/1410120

Fuchs C (2008) Internet and society: social theory in the information age. Routledge, New York

Fulminante F (2015) Infant feeding practices in Europe and the Mediterranean from prehistory to the Middle Ages: a comparison between the historical sources and bioarchaeology. Childhood 8(1):24–47. https://doi.org/10.1179/1758571615Z.00000000026