Abstract

Since the establishment of the green patent system in 2012, China has promoted significant advancements in green technologies in areas such as energy conservation, emission reduction and clean energy through accelerated patent examination mechanisms, policy incentives, and the construction of an intellectual property protection framework. However, despite the notable growth in the number of green patents, China’s green patent system still faces numerous challenges, particularly in terms of examination scope, examination standards, patent quality enhancement, and the participation of private entities. In addressing these challenges, China can draw on the valuable aspects of the green patent systems in the United Kingdom, the United States, Japan, and South Korea to gradually improve its own green patent system. In the future, China’s green patent system should progressively shift its focus from the growth in patent quantity to the enhancement of patent quality, ensuring the depth of technological innovation and its market value. Only in this way can China better achieve its “dual carbon goal” and provide a viable “Chinese solution” for global climate governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to ERA5 data from the EU-funded Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), the first three weeks of July were the warmest 3-week period on record, and the month is on track to be the hottest July and the hottest month on record (Copernicus, 2023a). The global average temperature in July of this year was briefly 1.5 °C above the world’s preindustrial level—a key global warming threshold set by the Paris Agreement (Copernicus, 2023b; Sohu.com, 2023). There have been repeated warnings, on the basis of a myriad of scientific studies, that the Earth’s ecology will face devastating damage if the global temperature rises by 1.5 °C above preindustrial levels (Djalante, 2019; Döll et al. 2018; Dosio et al. 2018; Mba et al. 2018). With respect to this situation, the Secretary-General of the United Nations claimed that “the era of global warming has ended” and “the era of global boiling has arrived (United Nations, 2024).

In this context of increasingly severe global climate change challenges, promoting the green and low-carbon transformation of societal development has become a core task for countries worldwide (Franklin and MacDonald, 2024; Toromade et al. 2024). As the world’s second-largest economy and the largest emitter of greenhouse gases, in 2020, China officially proposed the “dual carbon goals” of carbon peaking by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 and has ensured the achievement of these targets through the implementation of the most stringent legal measures. (Jia et al. 2022; An and Sang, 2022; Zhou et al. 2024). The achievement of these goals is not only essential for China to address climate change and fulfill its international commitments but also represents a crucial step in driving high-quality economic development in the country.

The development of environmental technologies forms the most critical foundation for China’s realization of its “dual carbon goal.” Since 2012, China has implemented a green patent system, which has provided essential legal protection for the development of environmental technologies within the Chinese legal framework (Liu et al. 2023; Lu, 2013). Green patents refer to invention patents that cover fields such as energy conservation and emission reduction, clean energy, and carbon capture and storage (Hsu, 2016). Their core function lies in promoting the development of a low-carbon economy through technological innovation (Petruzzelli et al. 2011). The establishment and optimization of the green patent system incentivizes companies and research institutions to invest in innovation while facilitating the marketization and global dissemination of environmental technologies (Hall and Helmers, 2013). Through the establishment of green patent systems, countries worldwide provide intellectual property protection for innovators, encouraging the commercialization of green technologies and thereby advancing the transition to a low-carbon economy (Liu et al. 2023). The strengths and weaknesses of a country’s green patent system not only affect the effectiveness of its environmental policies but also determine its standing in the global low-carbon competition.

The realization of China’s “dual carbon goal” cannot rely only on the direct closure of heavily polluting industries or enterprises; rather, China must continuously improve the technological content of industrial manufacturing and continuously reduce greenhouse gas emissions through the development and application of green technologies (Dong et al. 2021). To this end, in February 2021, China’s State Council issued the Guiding Opinions on Accelerating the Establishment of a Sound Green, Low-Carbon and Circular Development Economic System and emphasized in the document that green and low-carbon technology research and development should be encouraged and that green technological innovation research actions should be implemented to layout a number of forward-looking, strategic, and disruptive scientific and technological research projects in the fields of energy conservation and environmental protection, clean production, and clean energy (China Government Network, 2021). In December 2022, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) also specifically issued the Implementation Program on Further Improving the Market-oriented Green Technology Innovation System (2023–2025). The program proposes accelerating the research and development and popularization and application of energy-saving and carbon-reducing advanced technologies and gives full play to the key supporting role of green technologies for green and low-carbon development (China Government Network, 2022). In view of this, how to protect and incentivize the development and application of green technologies has become an important part of whether China’s “dual carbon goal” can be achieved.

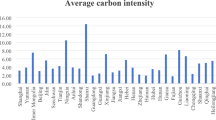

At present, China has secured a significant position in the global green patent application landscape. According to the latest data released by the China National Intellectual Property Administration in 2024, the number of publicly disclosed green and low-carbon patent applications in China reached 573,000 from 2016 to 2023, with an average annual growth rate of 10% (CNIPA, 2024; Toromade et al. 2024). However, the mere increase in the number of patents is insufficient to support the high-quality development of China’s green economy. While China boasts a large volume of green patent applications, these applications often lack technological depth and market value (Zheng, 2016). The large number of filings may result in varying patent quality, indicating that China’s green patent system needs to shift from a focus on quantity-driven growth to quality-oriented improvement (Wu and You, 2022). At the same time, the development of green patents in China remains highly dependent on government policies and financial support. Between 2016 and 2023, among the top fifty applicants for global green and low-carbon patents, China accounted for 13 positions. However, the majority of these applicants, such as State Grid, Sinopec, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Tsinghua University, are entities supported by state funding (Ma and Qin, 2019; Rikap, 2022). This reliance on government support may result in an overdependence by enterprises on policy incentives, thus neglecting the crucial role of market mechanisms in driving green technology innovation. In fact, this is one of the main reasons why the industrialization process of green patents in China has been relatively slow, as it remains largely disconnected from actual market demand.

In conclusion, China’s green patent system still requires more scientific institutional design and policy guidance to ensure that patent applications for green technologies receive more effective protection and market promotion, thus facilitating the successful achievement of the “dual carbon goal.” This is not only a crucial issue faced by China’s policymakers and scholars today but also the core focus of this paper. The primary research objective of this paper is to systematically review the development of China’s green patent system; compare it with the green patent systems of the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and South Korea; and identify the characteristics of and gaps in China’s system. This paper will also conduct a thorough analysis of the current deficiencies in China’s green patent system and, on the basis of these findings, propose recommendations for further optimize China’s green patent system and support the timely completion of the “dual carbon goal.” Furthermore, this research aims to contribute to China’s efforts to offer solutions to the escalating global climate change crisis. These research objectives will be addressed progressively in sections two, three, four, and five of this paper.

Literature review

For many years, the international academic community has paid increasing attention to the issue of intellectual property protection in China and has conducted discussions from multiple perspectives. Many papers have reviewed and studied the development of the legal mechanisms for intellectual property protection in China (Yang, 2003). Some papers have affirmed China’s initial establishment of the intellectual property system in the late 20th century (Bosworth and Yang, 2000), whereas others have noted that China still has not fulfilled its international responsibilities in intellectual property protection and that the infringement of intellectual property rights in China has undermined the international rule of law, damaging China’s legitimacy as a leader in the constantly evolving global governance structure (Brander et al. 2017). There are also papers that have sharply criticized China’s intellectual property protection, stating that there are still enormous loopholes in China’s current intellectual property protection, which affects China’s international relations and even poses a threat to the national security of certain countries (Cerrano, 2019; Halbert, 2016; Holmes, 2019).

Among the numerous studies on intellectual property protection in China, few have focused on the issue of intellectual property protection in China’s green technologies. Some scholars have analyzed the number of Chinese patents and noted that China has made significant progress in the intellectual property protection of green technologies, but overall, it has not reached the ideal state (Wang et al. 2019). Some scholars have noted that China is currently striving to establish a green patent framework, but the specific details still need to be improved, and the impact of legislative changes on the development of green technology remains to be observed (Wang, 2022). In September 2020, after China proposed its ambitious dual carbon goal, the International Academic Festival showed great enthusiasm for research on this issue, and there are many papers analyzing this issue from a legal perspective (Hao et al. 2022; Huang et al. 2023; Wang et al. 2021).

Another category of literature that deserves particular attention in this study is that which questions the role of intellectual property (IP) rights in driving technological innovation (Boldrin and Levine, 2009; Dreyfuss, 2010). Many scholars advocate this perspective, arguing that while IP systems are designed to encourage innovation, overly strict IP protections often result in monopolistic control, thereby impeding the diffusion of technology and the spread of knowledge (Burk, 2012; Lemley, 2015). Indeed, these scholars reveal the dual role of IP systems: on the one hand, they protect innovators’ interests and incentives; on the other, they can impede subsequent innovation and create knowledge monopolies (Gilbert, 2011). In the current era of rapid green technology development, the significant value of this critical perspective should also be acknowledged. We believe that the value of IP systems can indeed be questioned, but it is essential to distinguish across industries. Some industries, characterized by fast-paced technological updates, low barriers to innovation, and limited reliance on IP protection to secure market advantages, are more adaptable to arguments against IP systems. Examples include information technology, software, and creative industries. However, other industries that rely on high-tech investments have a strong need for IP protection; lacking it may weaken incentives for innovation and inhibit high-cost, long-term R&D activities (Kennedy, 2011; Rotta, 2024). Such industries include pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, advanced manufacturing, and the green technology sector examined in this study. The green patent systems established by many countries today do not fully guarantee the promotion of innovation; however, based on empirical evidence, countries currently leading in green technology tend to have well-developed IP systems, such as the United States, China, Germany, Japan, and South Korea. Therefore, we maintain full confidence in the value of this study.

The above literature provides valuable references for the discussion of this article. However, the literature seems to lack a connection between China’s green intellectual property protection and the fulfillment of China’s dual carbon goal, and most of them focus on exploring one of these two issues. In fact, the development of green technology is the most significant foundation for China to achieve the dual carbon goal, and the legal protection of green intellectual property rights is the fundamental guarantee for the development of green technology. Therefore, from the perspective of promoting intellectual property protection of green technology in China, we can explore China’s true environmental determination and the practical possibility of achieving the dual carbon goal. Moreover, through a systematic and detailed exploration of China’s green intellectual property protection system, this study could relieve some misunderstandings in the current international academic community regarding China’s intellectual property protection field to some extent.

Methodology

The aim of this paper is to conduct a comprehensive examination of the evolution of intellectual property protection mechanisms for green technologies in China, with a focus on achieving the dual carbon goal. The paper seeks to systematically assess the current state of the system in both legislative and judicial contexts, pinpoint the challenges it encounters, and propose specific recommendations. To fulfill these research objectives, the primary methodology employed is the legal-dogmatic approach. The legal-dogmatic method is a research approach in jurisprudence that focuses primarily on the interpretation, analysis, and reasoning of legal texts. This method emphasizes a systematic understanding of legal rules and regulations and relies on logical reasoning and the inherent structure of legal texts. The approach places a strong emphasis on highlighting the importance of deducing conclusions through the analysis of the structure and content of legal texts (Vukadinović, 2021; Wróblewski, 1987). This paper primarily employs the legal-dogmatic method to analyze the legal provisions related to green intellectual property in China, the United Kingdom, and South Korea.

In conjunction with the legal-dogmatic research method, this paper also utilizes the case study approach as a significant research tool. Through in-depth analysis of actual legal cases, this method facilitates a deeper understanding of how legal rules are practically applied. A case study is a crucial tool in empirical legal research, allowing researchers to observe and understand how the law operates in real-life situations through the analysis of actual cases. By delving into specific cases, researchers can confront the concrete challenges faced in legal applications, gaining better insights into the effectiveness and issues within the legal system. This approach reveals the genuine impact of legal rules on practice, providing a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the intricacies of the legal framework. Without employing the case study method, the paper would be limited to abstract discussions and unable to accurately depict the true and comprehensive landscape of intellectual property protection mechanisms for green technologies in China (Hancock et al. 2021; Numagami, 1998).

Additionally, the comparative research method plays a crucial role in this paper. Comparative research is a crucial methodology in legal studies, involving the analysis and comparison of similarities and differences among different countries, legal systems, or legal frameworks. By scrutinizing legal systems across various countries or regions, researchers gain a more comprehensive understanding of both the similarities and distinctions within a legal system across different nations. This aids in uncovering distinctive features within legal frameworks, enabling researchers to delve deeper into the essence of law. Additionally, it allows researchers to draw meaningful comparisons that provide valuable insights, facilitating the generation of improved recommendations for enhancing one’s own legal system on the basis of observations and lessons from others. Given that intellectual property protection mechanisms for green technologies in China are not indigenous but rather derived from international law systems, engaging in comparative research becomes imperative. This approach allows for a thorough exploration of the similarities and differences among various legal systems, frameworks, and practices. In the context of this research, comparative analysis is essential to demonstrate the distinctive features of intellectual property protection mechanisms for green technologies in China and to elucidate the challenges it confronts (Gordley, 1995).

Development history of China’s green technology intellectual property rights system

China’s green technology IPR protection system was formally established in 2012, and the landmark document for its establishment was the Administrative Measures for Priority Examination of Invention Patent Applications (Wang et al. 2019). Prior to that, China’s Patent Law (1984) and the Patent Examination Guidelines (2010) had provided, in principle, for patent applications related to ecological environment protection. Patents with a “serious” impact on the ecological environment were categorized as “detrimental to the public interest” and excluded from the scope of patent applications. Since 2012, the CIPO has prioritized the examination of important patent applications involving energy savings and environmental protection, low-carbon technologies that conserve resources and other important patents that contribute to green development and has stipulated that requests for prioritized examination should be filed electronically. The IPO issues a preliminary examination opinion within thirty working days from the date of granting its request and finalizes the authorization within one year from the date of granting the priority examination application (Wu and You, 2022). These provisions were the beginnings of IPR protection for green technologies in China. Soon after, to adapt to the status quo of China’s domestic green technology development at that time and to improve the quality and efficiency of patent examination, the State Intellectual Property Office of China revised and formed the Administrative Measures for Priority Examination of Patent Applications on the basis of the Administrative Measures for Priority Examination of Patent Applications of Invention Applications of 2012 (Ma and Qin, 2019). At present, the development of China’s green technology intellectual property protection system is reflected mainly in the following aspects:

-

1.

In terms of the objects of protection, Articles 4(1) and (2) of the 2012 Measures for Priority Examination of Patent Applications for Inventions stipulate that important patent applications involving “energy-saving and environmental protection, new-generation information technology, biology, high-end equipment manufacturing, new energy, new materials, new energy automobiles and other technological fields” and “low-carbon technology, resource conservation and other important patent applications contributing to green development” may apply for priority examination of their pending patents. Important patent applications involving “low-carbon technologies, resource conservation and other important patent applications that contribute to green development” may apply for priority examination of their pending patents. Paragraph (1) of Article 3 of the Administrative Measures for Priority Examination of Patents promulgated in 2017 stipulates that patents involving “energy-saving and environmental protection, new-generation information technology, biology, high-end equipment manufacturing, new energy, new materials, new-energy automobiles, intelligent manufacturing and other national key development industries” can apply for priority examination. The 2017 Administrative Measures for Priority Examination of Patents deleted the provisions of the 2012 Measures for Priority Examination of Patent Applications for Inventions that stipulate that “low-carbon technologies, resource conservation and other important patent applications that contribute to green development”. In addition, the 2017 Administrative Measures for Priority Examination of Patents added provisions on the “Internet, big data and cloud computing” to the examination objects.

-

2.

With respect to examination procedures, Articles 6–11 of the 2012 Administrative Measures for Priority Examination of Patents for Invention make provisions for patent priority examination procedures. Articles 5–13 of the 2017 Administrative Measures for Priority Examination of Patents also make provisions for patent examination procedures. As seen from the above provisions, the 2017 Administrative Measures for Patent Priority Examination has simplified the procedures of the patent priority examination system but still retains the requirement that it needs to be examined and recommended by the provincial intellectual property office. The applicant shall apply by way of an electronic application to propose the granting of examination by means of the Green Patent Priority Examination System. In addition, Article 7 of the 2012 Administrative Measures for Priority Examination of Patents for Invention stipulates that the applicant must provide a “search report”. While the 2017 Administrative Measures for Priority Examination of Patents deleted this procedural requirement, the applicant only needs to provide prior technology or prior design information materials. If the applicant provides a search report, then it can be used as a description of the prior technology or prior information. The 2017 Administrative Measures for Patent Priority Examination simplify the procedure for patent priority examination and provide convenience for applicants.

-

3.

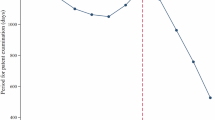

In terms of the examination period, both the 2012 Measures for Priority Examination of Invention Patents and the 2017 Measures for Priority Examination of Patents provide for substantive examination for patent preexamination and set the green patent examination cycle to be filed only after the application has entered the substantive examination stage. After an applicant initially files a request for a patent examination, it goes through a three-month preliminary examination period. After this period, the State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) makes an examination decision. The case will be closed for priority examination within one year after the substantive examination stage. Generally, the length of the priority examination for green inventions is ~16 months, whereas the length of the examination for ordinary invention patents is ~24 months. Compared with the examination period of ordinary patents, the green invention priority examination system has greatly shortened the period of patent examination. In particular, the promulgation and implementation of the Administrative Measures for Priority Examination of Patents in 2017 shortened the cycle of priority examination of patents in practice to <8 months (Zhao and Lu, 2019). Since the implementation of the national priority examination system for green patents, the number of green invention patents in China has increased annually.

-

4.

In terms of examination standards, China’s current system of intellectual property protection for green technologies has not yet formulated unified and clear standards for a priority protection system for green patents. Article 22 of China’s Patent Law positively stipulates the criteria for authorization of the patent system, i.e., the patented invention must be novel, inventive, and practical. The examination criteria for “green patents” are mentioned in the Patent Examination Guidelines. Among them, Chapter 4 of the 2001 Patent Examination Guidelines provides the “Benchmarks for Examining Invention Inventiveness”. This provision interprets the term “significant progress” in the “inventive step” of a patent for invention to mean an invention that has better technical effects than the closest existing technology. Examples include saving energy, increasing production, and preventing environmental pollution. When examined according to this standard, a patent for an invention that compounds the above-listed provisions has a beneficial technical effect and is, therefore notable. This provision incorporates the green factor into the scope of evaluation of the technical effect of “significant progress”. Since then, in Chapter 4 of the 2006, 2010, and 2019 versions of the Patent Examination Guidelines, this provision has been included in the interpretation of the “benchmarks for the examination of inventive step”. The Patent Examination Guidelines adopt the reverse exclusion provision to exclude technologies that “seriously pollute the environment, seriously waste energy or resources, or jeopardize the ecological balance” from the scope of granting patents. Chapter 4 of the Patent Examination Guidelines only provides for the reference factor that a patent for an invention cannot be easily recognized as noninventive, but it does not provide clear and direct provisions on the examination standards for “green patents”. In these versions of the Patent Examination Guidelines, the provision of “being able to produce positive effects” in the utility standard of invention patents is only interpreted as follows: on the date of the applicant’s invention or utility model patent application, the invention or utility model patent shall have positive and beneficial effects, and it should have economic and social benefits in the technical field of the invention or utility model that can be predicted by the relevant technical personnel. However, if an invention or utility model patent could have positive ecological effects on environmental protection, can it be interpreted as “capable of producing positive effects”? Therefore, the requirement of meeting the standard of utility is still questionable. If the environmental effect of the invention or utility model patent can be included in the scope of evaluation of utility, it is not clear to what extent the environmental effect can affect the connotation of utility.

In addition to the abovementioned factors, the promulgation of China’s Civil Code, particularly Articles 9, 123, and 1185, has had a significant effect on the country’s green patent system (Franklin and MacDonald, 2024; Jia et al. 2022.Footnote 1 First, the Civil Code explicitly establishes the green principle (Article 9) as a fundamental civil principle for the first time, meaning that under the legal framework, green patents, which pertain to environmental protection, energy conservation, and emission reduction, are not only granted the property rights typical of patents but are also imbued with environmental and public interest characteristics. Article 123 of the Civil Code defines intellectual property, including green patents, as the exclusive rights of the patent holder, thereby strengthening the emphasis on private rights protection. This focus on private rights helps incentivize companies and individuals to engage more in green technology innovation, thus promoting the patenting and commercialization of energy-saving and environmentally friendly technologies. Furthermore, Article 1185 of the Civil Code introduces a liability rule that grants green patent holders the right to seek punitive damages in cases of infringement. This provision increases the deterrence against infringement and enhances the bargaining power and market competitiveness of green patent holders (An et al. 2024). In specific cases, the liability rule can compensate patent holders for losses caused by infringement, particularly when disputes cannot be easily resolved through market transactions, ensuring better legal protection of the holder’s legitimate interests.

However, these provisions of the Civil Code may also pose certain risks. For example, according to Article 123, the exclusive nature of green patent rights as proprietary rights grants patent holders strong control. This exclusivity can potentially lead to excessive expansion of private rights during the technology innovation phase, especially in situations of market asymmetry, where it may hinder other entities from entering the field, thereby affecting the sharing and application of green technologies and limiting the overall environmental benefits to society. Additionally, the Civil Code, in conjunction with the Administrative Measures for the Priority Examination of Patent Applications, has expedited the application and examination process for green patents. While this has encouraged green patent innovation, it may also lead to the phenomenon of “patent thickets (Hall et al. 2013).” The flaws in the fast-track examination process, such as insufficient scrutiny of application materials, could result in the authorization of low-quality patents, undermining the overall innovation and economic value of patents and impeding the entry of other promising green technologies into the market (Yuan and Li, 2020). Moreover, while the punitive damage mechanism plays a positive role in deterring infringement, it also carries the risk of abuse. Given the complexity of green technologies and the cumulative nature of innovation, many cases of infringement are passive or unintentional. Under the threat of punitive damages, some green patent holders may exploit legal measures for patent trolling, demanding excessive compensation or settlement fees from alleged infringers. This behavior could lead to an overprotection of patent rights, hindering normal innovation activities and market competition, thereby undermining the original intent of green patent protection.

In summary, China’s green patent protection system has made positive contributions to the development of green technologies in China, but several issues remain that cannot be overlooked.

International experience in the development of intellectual property protection for green technologies

In 2023, the combined number of publicly disclosed green and low-carbon patent applications from China, the US, Europe, Japan, and South Korea reached 159,000, accounting for 82.5% of the global total (Toromade et al. 2024). In terms of green technology research and development, the capabilities of the US, Europe, Japan, and South Korea remain strong, and these countries and regions have many aspects of their green patent systems that are worth China’s consideration. Since the United Kingdom was the first country to implement a green patent plan, this paper uses the UK as a representative of the European green patent system for comparative study.

The United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is considered the first country in the world to introduce a green patent protection system, with a primary focus on promoting the rapid development and commercialization of green technologies through accelerated examination processes and policy incentives (Lane, 2012). Launched in 2009, the Green Channel program is the cornerstone of the UK′s green patent protection system (Dechezleprêtre, 2013). This program allows patent applicants to apply for expedited patent examinations on the basis of the environmental benefits of their technology (Wang, 2022). Applicants need only inform the United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) that their invention relates to areas such as energy conservation, pollution control, or environmental protection technologies to request accelerated examination (Cho and Sohn, 2018). Through the Green Channel, the examination period can be shortened to under nine months. This mechanism provides businesses and research institutions with the opportunity to quickly obtain patent protection, helping innovators gain a competitive edge in the market (UK IPO, 2022). To further accelerate the market conversion of green technologies, the UK government introduced the Green Innovation Fund, which is specifically designed to support green technology projects with market potential. This fund ensures financial support for the research, development, and commercialization of green technologies, encouraging more innovations to come to fruition swiftly.

The UK′s green patent protection system not only focuses on the domestic market but also actively participates in international cooperation. The UK is a key member of the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), allowing UK companies and research institutions to apply for patents in multiple countries simultaneously through the PCT process.Footnote 2 Prior to Brexit, the UK′s patent application system worked in close collaboration with the European Patent Office (EPO), enabling U.K. companies to obtain unified intellectual property protection across EU countries through the EPO’s patent application process (Nuehring, 2010). After Brexit, the UK retained its cooperation with the EPO, ensuring that UK green technologies continue to be protected in the European market through the European Patent Office. Currently, the UK leads the world in wind power technology, and it is one of the largest offshore wind power markets globally, with world-leading expertise in the construction and operation of offshore wind farms.

The United States

The United States’ green patent protection system has had a significant global impact. In 2009, the US launched the Green Technology Pilot Program, marking an important milestone in the country’s green patent protection efforts (Zheng, 2016). This program aimed to accelerate the approval process for patent applications related to clean energy, pollution reduction, energy-saving technologies, and other relevant fields, providing businesses and research institutions with a fast track to obtaining patent protection. Through the Green Technology Pilot Program, eligible patent applications could benefit from expedited review. Typically, the patent approval process could take more than 2 years, but under this program, the review period was shortened to <12 months. This mechanism encouraged the rapid commercialization of green technologies, helping innovators gain a competitive edge in the field of environmental technologies (Ley et al. 2016). The covered technology areas included renewable energy (such as solar and wind energy), pollution control technologies (such as air and water pollution prevention), energy-saving devices, and green building technologies, ensuring that innovations in various environmental technologies received timely patent protection. In 2012, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) also launched the Patents for Humanity program, which provided patent awards and public recognition for green technologies, encouraging more innovators to participate in global environmental governance (Elliott, 2014). Participants not only received patent fee reductions but also had the opportunity to promote their environmental technologies through public platforms (Lee, 2017).

In 2022, the USPTO introduced the Climate Change Mitigation Pilot Program, which formally began on June 6, 2023 (Rahnasto, 2023). This initiative aims to further accelerate the review of patent applications related to climate change, supporting the development and commercialization of environmentally friendly technologies (Wang et al. 2024). The program focuses on technologies directly related to climate change, such as carbon capture and storage (CCS), renewable energy (such as solar and wind energy), and energy storage technologies, particularly innovations related to electric transportation and clean energy infrastructure. The launch of this program demonstrates that the US is strengthening its protection of climate change technologies and further promoting the development of green technologies (Saffery). Like the previous Green Technology Pilot Program, this new initiative also seeks to expedite patent review, with the goal of reducing the review period to 6–12 months so that relevant technologies can receive legal protection and be applied in the market as quickly as possible. Currently, the US leads in several green technology fields, including carbon capture and storage (CCS), electric transportation and energy storage technologies, and renewable energy. The US innovation incentive mechanisms, especially the Patents for Humanity program, could serve as valuable reference points for China. By establishing similar reward systems, more innovators could be encouraged to apply patent technologies to address environmental challenges.

Japan

In 2010, Japan introduced the Green Technology Accelerated Patent Examination System to encourage innovation and patent applications in environmental technologies (Fujii and Managi, 2016). The system aims to shorten the review period for green technology patents, helping businesses and research institutions secure patent protection more quickly, thereby promoting the commercialization of green technologies (Imai, 2015). Applicants can request accelerated examination on the basis of the environmental characteristics of their technologies. Typically, the patent review period for green technologies is reduced to <6 months, whereas the review time for general patents may take several years (Jiang et al. 2022). This fast-track review mechanism helps innovators gain an early advantage in the market and facilitates the early application of technologies (Nobel, 2021). The system covers a wide range of technological fields, including new energy, energy storage, electric vehicles, hydrogen technology, and waste treatment. Particularly with respect to hydrogen and energy storage technologies, Japan has promoted the rapid development of these areas through accelerated patent examination.

In recent years, Japan has made significant progress in green patent protection. Currently, Japan is one of the leading countries in global hydrogen technology, with innovations covering every stage of hydrogen production, storage, transportation, and application (Aldieri et al. 2019). The Japanese government’s financial support and technical research in the hydrogen sector have helped the country maintain its leadership in the global hydrogen field and drive the large-scale promotion of hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles (Khan et al. 2021). In the global green technology sector, energy storage technology is another major area of innovation for Japan, especially in electrochemical energy storage, where Japan has become a global leader. China can learn from Japan’s experience in international patent layout to further enhance the global market influence of its green patents, particularly by establishing closer patent protection networks in cooperation with other countries. Additionally, Japan’s focus on technological depth offers insights for China in improving patent quality, avoiding an overemphasis on quantity at the expense of the innovation value and technical depth of patents.

South Korea

The Korean Intellectual Property Office (KIPO) introduced a dedicated program in 2011 to support the development of green technologies, combining accelerated examination, financial support, and intellectual property policies (De Lima et al. 2013). The program aims to increase the nation’s competitiveness in addressing climate change and ensure that environmentally innovative technologies can quickly receive patent protection and enter the market. Green patent examinations are typically completed within 6 months, whereas the review process for regular patents may take over two years (Lu, 2013). The South Korean government, through KIPO, also provides commercialization support for green technologies to enterprises, encouraging collaboration among companies, universities, and research institutions to accelerate the marketization of technologies (Patton, 2011). KIPO also offers consulting services on patent application and management, assisting companies in developing intellectual property strategies.

In 2020, the South Korean government launched the “Green New Deal,” a major policy framework aimed at addressing climate change and promoting the development of green technologies (Lee and Woo, 2020). This plan is closely linked to the green patent system, driving innovation in areas such as renewable energy, electric transportation, and smart cities (Han and Lee, 2023). Currently, South Korea’s battery manufacturers (such as LG Energy Solution and Samsung SDI) hold a significant position in the global power battery market, providing advanced lithium-ion and solid-state battery technologies for the global electric vehicle industry (BusinessKorea, 2024; Lu, 2013). South Korea is also one of the global leaders in hydrogen technology, with Hyundai’s development of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (such as the Nexo) gaining international recognition (Sery and Leduc, 2022).

South Korea’s green technology accelerated patent examination system is one of the most efficient in the world and serves as a key reference point for China. Moreover, South Korea’s Green New Deal provides a coordinated policy approach between the government and enterprises, which is crucial for the commercialization of green technologies and represents a comprehensive model that China can adopt to further promote the development of its green technologies.

In conclusion, the United Kingdom, the United States, Japan, and South Korea each demonstrate unique strengths in the construction of their green patent systems (see Table 1). China can draw valuable lessons from these four countries, adapting them to its own national conditions to optimize its green patent protection system. In the following section, we propose specific measures to improve China’s green patent system.

The dilemma of intellectual property protection for green technology in China

With the proposal of the “dual carbon” goal, the construction of China’s green technology intellectual property rights protection mechanism has gradually attracted attention. However, in the process of realizing the “dual carbon” goal, China’s green technology intellectual property protection mechanism faces multiple challenges and deficiencies. Specifically, it mainly includes the following dilemmas.

Relatively limited scope of protection of green IPRs

With the global focus on environmental sustainability, green technologies, and innovations are becoming key elements in driving economic growth and reducing emissions. However, the protection of green IPRs in China still faces several challenges. Against the backdrop of the global dual carbon target, the scope of green IPR protection in China is relatively limited. While national key development industries and local key encouragement industries have received more attention, the scope of attention for green technology industries has been decreasing. In the case of waiting for the surplus of the patent examination department’s examination capacity, there are very few green patent applications that can be obtained on the express train (Brander et al. 2017).

First, while China has made remarkable progress in terms of environmental protection and sustainable development, the criteria for defining and classifying green technologies remain ambiguous. This lack of clarity not only affects the speed and efficiency of patent examination but also limits the range of technologies that qualify for green patent protection. For example, China does not have a well-established green technology classification system akin to the WIPO Green Inventory, which is used internationally to identify green patents. Without this, there is confusion about what qualifies as a green technology, and this ambiguity hinders the development of a consistent protection framework. Additionally, the national and local key industries that receive more attention may not always align with green technologies. This has resulted in a narrowing focus on green technology industries, leaving many innovative green technologies, such as advanced waste recycling systems or new energy storage solutions, outside the scope of fast-track patent protection. In contrast, countries such as Japan and Korea have more targeted green patent policies, which ensures that emerging technologies in specific environmental sectors can benefit from accelerated examination and enhanced protection.

Second, the limited capacity of the patent examination department has also contributed to the slow progress in green patent applications. Even though green patents can technically qualify for fast-track examination, the overall examination capacity is constrained, meaning that many green patent applications experience long delays. This situation discourages enterprises from prioritizing green innovations, as they cannot rely on timely protection of their intellectual property. In countries such as the United States, the implementation of specialized green patent examination units has streamlined the process, offering a potential model for China to consider.

In conclusion, the lack of a comprehensive classification system for green technologies and the overburdened patent examination capacity are two key factors limiting the scope of green IPR protection in China. To expand this scope, clearer guidelines on what constitutes green technology, along with increased examination resources, are necessary. These improvements will not only enhance innovation in environmentally friendly technologies but also strengthen China’s role in international green technology development.

Lack of uniform and clear priority examination criteria for green patents

Green patents, as a special form of innovation in the field of environmental protection, are highly important for sustainable development and the construction of an ecological civilization. However, there is a lack of unified and clear priority examination standards for green patents in China, which has a certain impact on stimulating innovation and promoting the transformation and promotion of green technologies. Currently, the criteria for determining what qualifies as a green patent are inconsistent, which causes confusion during the examination process. In the face of increasingly severe environmental challenges, the importance of green patents has become increasingly prominent. A more standardized and transparent framework is necessary to ensure that green technologies, especially those with high environmental and societal impacts, can benefit from expedited examination.

The creation and protection of green patents helps to not only promote R&D, the application of environmentally friendly technologies and create innovation value and commercial interests for enterprises but also enhance China’s international discourse rights. However, the absence of a standardized classification system for green technologies, which we see in other countries such as the United States and Japan, prevents China from developing a more effective fast-track patent system. In contrast, these countries have introduced specific green patent categories, ensuring that priority examination is given to technologies that address key environmental issues, such as carbon capture, renewable energy technologies, and energy efficiency improvements.

As some scholars have noted, in the process of system design, the intellectual property system can stimulate innovation and promote economic and social progress and development by establishing the protection of private rights and stimulating the interests of intellectual property rights holders (Wang, 2022). The identification of green technologies with inconsistent standards is bound to be an obstacle that causes difficulties in the international patent application (PCT) filing of green technologies, as well as in the internationalization process of the fast-track examination system for green patents (Huang et al. 2023). Without a uniform green patent classification, it has also become more challenging for China to align with international standards, especially as global cooperation on climate change mitigation intensifies. This discrepancy hinders the competitiveness of Chinese green innovations on a global scale.

China’s active participation in the formulation of international standards in technological fields where it is in a position to do so will not only improve its international competitiveness and break the monopoly of developed countries over important seats in the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) but also gain more international discourse rights (Hao et al. 2022). To build on this, China must focus on implementing clearer criteria for green patent examination that align with international best practices. By doing so, China can not only facilitate the PCT process but also strengthen its position in international patent collaborations, making it easier for Chinese green innovations to be recognized and protected globally.

However, owing to the lack of uniform and clear standards for the prioritized examination of green patents, many environmentally friendly technological innovations face problems such as long examination cycles and cumbersome examination processes, which impede the rapid transformation and application of green technologies. For example, in China’s current system, some green technologies—such as those in advanced recycling systems or sustainable agriculture innovations—might not receive adequate attention because of a lack of standardization. This has led to longer wait times for patent approvals and, ultimately, slower deployment of crucial green innovations in the market.

The ambiguity and nonuniformity of the standards will lead to difficulties in the application of international patent applications (PCTs) for green technologies and increase the obstacles to the internationalization of the green patent priority examination system (Huang et al., 2023). Therefore, China should develop clearer standards and guidelines for green patent examination, as more consistent criteria can stimulate enterprises to innovate in environmentally friendly fields. The establishment of unified and clear green patent priority examination standards is highly important for accelerating the pace of green innovation.

First, the formulation of a unified and clear examination standard for green patent priority helps stimulate the enthusiasm of enterprises for innovation in the field of the environment and further promotes the research, development, and application of green technology. It will also help reduce the examination time and costs associated with green patents, improving the efficiency of the entire process. Additionally, this will increase China’s competitiveness in terms of environmental innovation, as it would create a more predictable and supportive environment for green tech enterprises.

Moreover, a unified and clear examination standard can reduce the examination cycle and examination cost, improve the examination efficiency of green patents, and provide enterprises with more convenient and efficient intellectual property protection services. In addition, such standards can be adapted over time to address new environmental challenges, ensuring that China’s green patent system remains responsive and forward-looking.

Relative lag in the development of intellectual property protection mechanisms for green technologies

Against the backdrop of the global response to climate change, China, as one of the world’s most populous countries, has taken a proactive approach to addressing environmental challenges and implementing the dual carbon target, a move that has attracted much attention. However, at the same time, we should also be concerned that China is lagging behind in terms of intellectual property protection mechanisms for green technologies.

First, China’s legal and regulatory system for the protection of green technology intellectual property rights is not yet perfect. Although some legal documents already address the protection of green intellectual property rights, the overall situation still lacks systematization and pertinence. While certain regulations exist, they are often fragmented and lack the comprehensive, cohesive structure that is seen in more mature IP systems in countries such as Japan and the US. In particular, the green IP regulatory framework in China does not clearly differentiate between different categories of green technologies, making it difficult to implement protections that are specific to each type of innovation, whether related to renewable energy, waste management, or carbon capture. This lack of a detailed, technology-specific regulatory framework diminishes the effectiveness of the protection.

Moreover, the supervision and enforcement of green IPRs need to be strengthened to ensure their effective implementation. Although punitive damages were introduced in China’s Civil Code to deter patent infringement, enforcement mechanisms for green patents remain weak and inconsistent. For example, many local patent offices lack the technical expertise to accurately assess the value of green innovations, leading to inconsistent enforcement across regions. In contrast, Korea has established specialized green patent divisions within its intellectual property offices, which ensures that these patents are evaluated and protected with the necessary expertise.

Second, there are major limitations in China’s assessment and identification of green IPRs. Internationally, the assessment and identification of green IPRs is relatively mature. However, in China, the lack of relevant professional organizations and standards often leads to disputes over the recognition of green innovations. This also restricts the transfer and application of green technologies and further affects the progress of environmental protection. In countries such as the United States, green patent certification programs have been introduced to ensure that the most environmentally impactful technologies are clearly identified and given priority protection. China currently lacks such a formal certification system, which makes it harder to differentiate between truly innovative green technologies and more conventional innovations that have only marginal environmental benefits.

In addition, China needs to strengthen its awareness of green technology intellectual property protection. As an emerging field, awareness of green IPR protection and related knowledge is not yet widespread in China. Many enterprises and individuals lack awareness of the importance of green intellectual property rights, which not only makes their innovations susceptible to infringement but also hinders the sustainable advancement of green innovation. While China’s government has made significant strides in promoting environmental technologies, through policies such as the Green Development Fund and financial support for green enterprises, the issue of intellectual property remains underemphasized. Green technology innovators, especially in smaller firms or startups, often struggle with the costs and complexity of patent applications, which further reduces their motivation to secure proper protection for their innovations.

To address these challenges, China must develop a more structured and targeted system for identifying, evaluating, and protecting green innovations. This could include the establishment of dedicated green patent offices or divisions within the existing IP framework, as seen in Korea and Japan. Additionally, greater education and awareness campaigns aimed at businesses and entrepreneurs would help foster a stronger culture of green innovation protection. Collaborating with international organizations, such as the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), could also provide a platform for China to adopt best practices and ensure that its green patents are globally competitive.

Improvement of intellectual property protection mechanisms for green technologies in China

Against the backdrop of increasingly severe global environmental problems, China, as one of the world’s largest carbon emitters, has responded positively to and committed itself to the realization of the dual carbon goal and is determined to move toward a low-carbon, green path of future development (An and Liu, 2023). Against this background, it is particularly important to improve the protection of intellectual property rights for green technologies in China.

Progressively broadening the scope of the review of the intellectual property rights mechanism for green technologies

Given today’s growing concern for environmental protection and sustainable development, the gradual expansion of the scope of scrutiny of the green intellectual property rights system has become an important initiative. This review of the green intellectual property system aims to protect innovative products and technologies that make a significant contribution to environmental protection, renewable energy, and sustainable development. Expanding the scope of the review is crucial, as green technologies are evolving rapidly and encompass a wider range of innovations than ever before. These include emerging fields, such as hydrogen energy, electric vehicles, and smart grids, which are essential for the transition to a low-carbon economy and will also be highly beneficial for resolving many of China’s current environmental disputes on the international stage (An et al. 2024). In the process of expanding the scope of review, it is necessary to focus on innovative areas such as environmentally friendly new energy technologies, cleaner production methods, and the reuse of recyclable materials, with the goal of ensuring that innovations in these areas receive fair and effective intellectual property rights protection.

In addition, the quantitative limitation on the priority examination of green patents should be revised, and exceptions should be added. When examining green invention patents, the State Intellectual Property Office may, in accordance with the provisions of the green patent standard, stipulate that environmentally friendly technologies that comply with the green standard may be specified as exceptions and cancel the quantitative restriction (Green Channel for Patent Applications, 2024). By removing or adjusting such limitations, the review process can become more flexible and adaptive to the diverse range of green innovations being developed. In particular, advanced technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) or bioenergy innovations should not be restricted by the current limits, as their impact on reducing greenhouse gases is significant.

By expanding the scope of scrutiny of the green intellectual property rights system, environmentally friendly innovations are actively encouraged and supported, helping to promote the process of sustainable development. This initiative encourages enterprises and individuals to invest more in green technologies by providing a clearer and more inclusive protection mechanism. For example, companies that are developing breakthrough technologies in areas such as ocean energy or urban air quality control could benefit from a more comprehensive intellectual property protection system.

This initiative is committed to establishing a fair and transparent review mechanism for the green intellectual property system to ensure that all environmentally friendly technologies and innovations that meet the relevant standards can fairly enjoy the rights and interests of intellectual property protection. Strengthening this system will also help combat illegal infringement more effectively, ensuring that innovators’ legitimate rights are better safeguarded. As China faces increasing international competition in green technology innovation, improving the IP review system can also position the country more favorably on the global stage. Countries such as Germany and South Korea have already broadened their own green patent systems to encourage innovation in next-generation energy storage and electric mobility.

Moreover, improvements in the green patent examination system also need to strengthen the regulation and protection of intellectual property rights, combat illegal infringement, and safeguard the legitimate rights and interests of innovators. Expanding the scope of the review of the green intellectual property rights system is one of the important measures for promoting sustainable development. In this context, improving cooperation between patent examiners and environmental experts could help ensure that patent decisions are based on sound scientific understanding, enhancing the credibility and reliability of the system.

Establishment of uniform and clear priority examination standards for green technology patents

In the context of the current era of increasingly prominent environmental issues, to encourage and promote green innovation, it is imperative to formulate a unified and clear green patent priority examination standard. The green patent priority examination standard refers to the policy measures of giving priority examination and accelerated approval to patent applications that are environmentally friendly, support sustainable development, and have a significant impact on solving environmental problems.

One of the main challenges today is the lack of a clear and consistent standard for determining which green technologies qualify for priority examination. This lack of clarity can result in delays for innovations that could otherwise contribute significantly to environmental protection. For example, technologies such as carbon-neutral fuel production or next-generation renewable energy storage should receive priority, yet their classification as “green” often depends on subjective interpretation due to the absence of standardized criteria. Therefore, creating a clear standard will help ensure that the most impactful technologies receive timely approval.

First, the formulation of review criteria is an inevitable response to today’s environmental situation. As global warming, ecological damage, and resource waste continue to escalate, the need for green innovation becomes more urgent. The formulation of the priority examination standard for green patents can motivate enterprises and individuals to carry out innovative research and development in the field of environmental protection and provide effective technologies and solutions for solving environmental problems, thus realizing sustainable development. For example, specific criteria related to energy efficiency, emissions reduction, and pollution control can be established to guide the patent review process, ensuring that innovations targeting these areas are prioritized.

Second, the formulation of standards will promote technological progress and information sharing. The Green Patent Priority Examination Standard can encourage companies to pursue bold innovations by reducing the risk of long delays in patent approval. This will broaden the market application and promotion of green technologies and encourage innovative enterprises to make more investments and research and development in the field of environmental protection technologies. In countries such as Japan and South Korea, clear and transparent priority examination policies for green patents have already encouraged investment in emerging green technologies, such as hydrogen fuel cells and smart grid systems. Moreover, standards should facilitate better information sharing between patent applicants and environmental experts. The Green Patent Priority Examination Standard will also promote information sharing and encourage patent applicants to disclose and share their knowledge of green technologies, thereby accelerating the process of solving environmental problems (Zheng, 2016). Encouraging the sharing of patented technologies within certain environmental sectors, such as water purification or carbon capture, could also help foster collaboration and accelerate green innovation.

In addition, the development of standards will provide stronger policy support for the field of green innovation. By clearly defining what qualifies for priority examination, the government can target financial incentives, such as tax benefits and subsidies, to support companies in developing these technologies. By prioritizing the examination and accelerating the approval of green patent applications, it can provide green innovation enterprises with more competitive advantages and business opportunities in the market. This also aligns with China’s dual carbon goal, encouraging businesses to pursue innovations that directly support national environmental targets.

Finally, the development of review standards will also enhance international competitiveness. In the global race to develop green technologies, having a clear, efficient patent examination process gives China an advantage. Environmental protection is a common challenge facing the world, and all countries are actively seeking solutions (Jinyan, 2017). By formulating a unified and clear standard of priority examination for green patents, China can attract more international companies and researchers to collaborate and invest in the country’s green technology sector. This will boost China’s competitiveness in terms of environmental innovation and enhance its leadership in global sustainability efforts.

In summary, the formulation of uniform and clear priority examination standards for green patents is an important initiative that will promote the development of green innovation, facilitate the progress of environmental protection technology, enhance national competitiveness, and realize the goal of sustainable development. The government, enterprises and all sectors should collaborate in the establishment of these standards. At present, some scholars have proposed the idea of adding new green standards. These suggestions highlight the need for more specific criteria, particularly in emerging fields such as biodegradable materials and carbon-negative technologies. By focusing on these areas, China can ensure that its patent system remains relevant and responsive to the most pressing environmental challenges.

Strengthening of the intellectual property rights regime for green technologies

China needs to intensify its efforts to build an intellectual property protection mechanism for green technologies. This is essential in light of the growing need to promote sustainable development and achieve the country’s dual carbon goal. First, the government should strengthen the formulation and improvement of relevant laws and regulations to establish a complete green technology intellectual property protection system (Cao, 2016). While China has made progress in enacting environmental protection laws, there remains a gap in the specific legal framework that governs green intellectual property rights. Many of the current regulations are fragmented and lack the systematic support needed to address the unique challenges posed by green technologies, such as their interdisciplinary nature and the rapid pace of innovation.

In particular, it is crucial to create specific legal provisions for the protection of key green technology sectors, such as renewable energy, carbon capture, and waste-to-energy innovations. These technologies are often the target of infringement and unauthorized use, making robust legal protections all the more important. Moreover, the supervision and enforcement of green intellectual property rights should be strengthened to ensure their effective implementation (Qin, 2017). This can be achieved by developing specialized green IP enforcement teams within relevant regulatory bodies. Countries such as Germany and Japan have already established specialized green IP divisions, which ensure that green technologies receive the focused attention and enforcement they require.

The selection of patent examiners should be in line with the qualifications, and in the process of examination, it should be ensured that the indicators are distinct and independent of each other and can comprehensively, realistically, and concretely reflect the impact of the technological environment rather than relying on subjective assumptions (Dechezleprêtre, 2013). Moreover, examiners should receive additional training in green technologies to ensure that they can properly evaluate the ecological and technical benefits of each invention. In fields such as biotechnology and energy storage, where innovations are rapidly advancing, the need for skilled examiners is particularly acute.

Second, professional organizations should be established, or the capacity building of existing organizations should be strengthened to enhance the professionalism and scientificity of green intellectual property assessment and recognition. Establishing independent green technology evaluation bodies would allow for more accurate assessments of the environmental impact and market potential of green innovations. These organizations can provide expert opinions during the patent review process, thereby reducing disputes and ensuring that patents are awarded only to truly innovative and beneficial technologies.

This will help reduce disputes and promote the transfer and diffusion of green technologies. Green technologies are often complex and involve multiple fields of science and technology, which can make patent enforcement and technology transfer difficult. Strengthening these institutions will ensure that green patents are more easily enforceable and that innovators feel confident in the protection of their IP rights. For example, technologies related to urban sustainability and renewable material innovations can be rapidly scaled up and transferred to other markets if IP protections are clear and enforced consistently.

In addition, it is necessary to strengthen publicity and education on green technology intellectual property protection and increase the awareness of enterprises and individuals about protection. Many businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), lack awareness of how to protect their green innovations. By organizing awareness campaigns and providing training programs, the government can help these enterprises understand the importance of green IP and the steps necessary to protect it. This is crucial for fostering a culture of innovation, where companies actively pursue environmentally friendly technologies knowing that their IP rights are secure. By strengthening publicity and education, the awareness of green intellectual property rights can be increased, stimulating innovation and further promoting the development of China’s green economy. This also aligns with the broader goal of building an innovative and sustainable economy. Promoting IP education at the university level, particularly in technical fields related to environmental engineering and clean energy, can also help raise awareness among future innovators, ensuring that green technologies continue to advance and are protected under a comprehensive legal framework.

In conclusion, the construction of IPR protection mechanisms for green technologies in China is relatively lagging behind, but with the increasing awareness of environmental protection and the implementation of the dual carbon target, it is necessary for us to pay more attention to and invest in the protection of IPR for green technologies. By improving laws and regulations, strengthening assessment and recognition, enhancing the construction of professional organizations, and strengthening protection awareness, we can establish an efficient, scientific, and systematic IPR protection mechanism for green technologies and inject new vitality into China’s green development. Additionally, collaborating with international organizations such as the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) can help China adopt global best practices in green IP protection.

Balancing state-owned forces and free market forces to promote the commercialization of green patents

From 2016 to 2023, among the top 50 applicants for green patents in China, 13 were state-owned entities, with major state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and research institutions such as State Grid, Sinopec, and Tsinghua University playing a dominant role (Toromade et al. 2024). While this dominance of SOEs ensures foundational investments in green technology research and development, the participation of private enterprises, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), remains relatively low, resulting in a lack of market dynamism (Jiang and Liu, 2024). Although SOEs hold an advantage in green patent development, their reliance on policy-driven initiatives rather than market demand has led to slower commercialization processes.

The key to addressing this issue lies in targeted government policy incentives, such as green innovation funds, green project tenders, and tax incentives specifically designed for SMEs, to encourage greater private sector involvement in green technology innovation (Ali et al. 2023). To accelerate patent commercialization, China should establish a green technology market platform that connects the needs of enterprises with those of research institutions and patent holders. For example, drawing on South Korea’s experience, the Korean government has set up a green technology patent exchange center to foster closer collaboration between universities, research institutions, and businesses, thereby facilitating the application of patent outcomes in the market (Zhang et al. 2024). Additionally, financial support for technology transfer should be increased to encourage enterprises to bring green technology patents to the market more swiftly.

Conclusion

With the support of the green patent system, China’s environmental protection technologies have made significant progress over the past decade, which is worth acknowledging. However, compared with the emission reduction responsibilities that China must bear—especially if China aims to achieve its proposed dual carbon goal—there is still considerable room for improvement in the country’s green patent system. In this context, China should learn from and draw on the strengths of the green patent systems in other environmentally competitive nations, such as the United Kingdom, the United States, Japan, and South Korea. By progressively expanding the scope of examination within the green intellectual property system, establishing uniform and clear standards for green patent priority examination, and balancing state-owned forces and free market forces, China can continuously improve its green patent system. This will better enable China to fulfill its environmental commitments to the world and contribute to the development of global environmental protection by offering Chinese solutions.

Data availability

All tables and data are open-sourced and do not require copyright approval. All are referenced within this document.

Notes

Article 9 of China’s Civil Code: The parties to civil legal relations shall conduct civil activities contributing to the conservation of resources and protection of the environment.

Article 123 of China’s Civil Code: Civil entities legally enjoy intellectual property rights. Intellectual property refers to the exclusive rights that the rights holder legally enjoys over the following objects: works of authorship; inventions, utility models, and designs; trademarks; geographical indications; trade secrets; layout designs of integrated circuits; new plant varieties; and other objects as prescribed by law.

Article 1185 of China’s Civil Code: For intentional infringement of another’s intellectual property rights, where the circumstances are serious, the infringed party is entitled to request corresponding punitive damages.

Annex, I. C. 47 See International Association for the Protection of Intellectual Property, Standing Committee on Intellectual Property and Green Technology, Climate Change and Environmental Technologies—The Role of Intellectual Property, esp. Patents (2014) (“The United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) was the first office to introduce an accelerated. Intellectual Property, 50, 161.

References

Aldieri L, Carlucci F, Cirà A, Ioppolo G, Vinci CP (2019) Is green innovation an opportunity or a threat to employment? An empirical analysis of three main industrialized areas: the USA, Japan and Europe. J Clean Prod 214:758–766

Ali S, Ghufran M, Ashraf J, Xiaobao P, ZhiYing L (2023) The role of public and private interventions on the evolution of green innovation in China. IEEE Trans Eng Manag 71:6272–6290

An R, An X, Li X (2024) A new transboundary EIA mechanism is called for: legal analysis and prospect of the disposal of Fukushima ALPS-treated water. Environ Impact Assess Rev 105:107435

An R, Liu P (2023) Research on the environmental philosophy of China’s environmental crime legislation from the perspective of ecological civilization construction. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(2):1517

An R, Sang T (2022) The guarantee mechanism of China’s environmental protection strategy from the perspective of global environmental governance—focusing on the punishment of environmental pollution crime in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(22):14745

An R, Zhou Y, Zhang R (2024) The development, shortcomings and future improvement of punitive damages for environmental torts in China—a reflection and comparative research. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(1):507

Boldrin M, Levine DK (2009) Does intellectual monopoly help innovation? Rev Law Econ 5(3):991–1024

Bosworth D, Yang D (2000) Intellectual property law, technology flow and licensing opportunities in the People’s Republic of China. Int Bus Rev 9(4):453–477