Abstract

This article explores two primary questions: first, whether the issuance of green bonds contributes to environmental protection, particularly regarding their performance after the adoption of net-zero emission policies; and second, whether issuers of green bonds can have economic benefits. Using the Difference-in-Differences (DID) model to analyze green and conventional bonds issued from 2013 to 2023, the study finds no significant correlation between green bond issuance and CO2 emissions following net-zero adoption. Nevertheless, our findings are important and deserve attention as they indicate that the carbon reduction policies have not exerted sufficient pressure on bond issuers to reduce emissions. At the same time, however, a closer examination of issuing entities reveals that those issuing only green bonds tend to have higher ESG ratings, lower CO2 emissions, and lower financing costs. This suggests that such issuers achieve substantial environmental benefits and economic advantages. In contrast, entities issuing both conventional and green bonds do not demonstrate the same environmental benefits. This finding raises concerns about potential greenwashing, suggesting that entities issuing both green and conventional bonds may engage in practices that contradict environmental protection while presenting their activities as environmentally friendly through green bonds. The study also highlights that the impact of bond features on ESG scores and CO2 emissions varies significantly across different types of issuers. Finally, the paper recommends that policymakers strengthen carbon reduction policies, establish mechanisms to prevent greenwashing, and integrate CO2 emissions and ESG factors into assessment systems. Additionally, it calls for special attention to the carbon emissions of entities in low- and middle-income countries, as well as those in the manufacturing sector, to support the healthy development of green finance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Green has become the colour of our time. There is a widespread consensus on the need to promote environmental sustainability in politics, economy, and culture to essentially ensure the future of humanity. In the financial sector, green finance has gained wide acceptance and continues to develop. Wang and Zhi (2016) argue that if the market mechanisms behind green finance are rational, green finance encourages effective environmental risk management and supports optimal utilization of environmental resources by guiding the flow of funds. As an essential component of the economic society, the importance of enterprises in environmental protection and pollution control is undeniable (Ren et al., 2023). According to the International Capital Markets Association, green bonds are defined as “any type of bond instrument where the proceeds will be exclusively applied to finance or re-finance, in part or in full, new or existing eligible green projects.” As a representative example of green finance, green bonds have experienced rapid growth in recent years due to their unique green attributes. Green bonds are labelled as such because they are specifically designed for financing or refinancing green projects. As Sun et al. (2022) point out, the most important difference between green bonds and conventional bonds is the “green label.” While green bonds bear the green label, conventional bonds are associated with the “brown” label. The distinction between these colour labels has attracted research interest, including comparisons between green bonds and conventional bonds, analysing the advantages and disadvantages of green bonds relative to traditional bonds, examining the cost of financing green bonds, exploring motivations behind investing in green bonds, and studying the environmental impact of green bond financing (Mokni et al., 2022; Zerbib, 2019; Maltais and Nykvist, 2020).

Empirical studies also consistently show a significant yield difference between green bonds and conventional bonds, indicating that green bonds have the potential to reduce the cost of debt financing and promote sustainability within the financial community (Mokni et al., 2022; Teti et al., 2022). Companies that embrace social responsibility can issue lower-cost bonds with higher risk premiums compared to non-socially responsible companies (Menz, 2010; Oikonomou et al., (2014)), confirming the research conclusion of Bauer and Hann (2010) that proactive environmental practices by companies lead to lower debt costs. From an investment perspective, investors opt for green bonds to mitigate environmental uncertainty associated with conventional bonds (Loffler et al. (2021)). When investors engage in socially responsible investing, they not only consider payoffs but also assume preferences for assets as consumption goods (Fama and French, 2007).

When discussing green bonds, it is essential to consider ESG. Both are born and developed against the backdrop of sustainable development. Green bonds serve as financing or refinancing tools for green projects, while ESG highlights the importance of green and sustainable development. Research suggests that green bond issuers with better environmental performance and higher ESG ratings gain more attention from investors (Larcker and Watts, 2020; Cheng et al., 2022).

In discussions of environmental finance, the topic of greenhouse gases cannot be avoided. Cowan (1998) highlighted their contribution to global warming. Consequently, greenhouse gas emissions have become widely used as a metric for assessing environmental impact in lieu of environmental business strategies (Cowan, 1998; Fatica and Panzica, 2021). This has been especially pertinent since the Paris Agreement of late 2015 which introduced policies targeting net-zero carbon emissions. CO2 emissions have since become a primary measure for evaluating the environmental impacts of sustainable development projects (Zuo et al., 2012; Gupta et al., 2020; Tiwaril et al., 2024).

From the perspective of “rational actor” hypothesis, the actions taken by companies should be profitable. So, what benefits can companies gain from issuing green bonds? Due to their dual environmental and economic attributes, it is necessary to explore the financing effects of green bonds from both the perspectives of morality and profit. Have companies, as issuers of green bonds, reduced their greenhouse gas emissions, thereby contributing to environmental protection and achieving environmental benefits? In addition, have companies reduced their financing costs by issuing green bonds and gained economic benefits? To study the environmental and economic impacts of issuing green bonds on issuers, this paper selected green bonds issued by non-financial corporate entities that disclosed ESG information from 2013 to 2023 as a sample and compared them with conventional bonds. The bond issuers were categorized into three groups: those exclusively issuing green bonds, those exclusively issuing conventional bonds, and those issuing both types. To draw conclusions, we conducted descriptive statistics, Difference-in-Differences (DID) analysis, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression, decision tree analysis, random forest modelling, and robustness tests. The findings suggest that following the implementation of carbon neutrality policies, there is no significant correlation between the issuance of green bonds and equivalent CO2 emissions. However, entities that exclusively issue green bonds tend to have higher ESG scores and a stronger negative correlation between their ESG scores and equivalent CO2 emissions, indicating that issuers solely focused on green bonds can achieve environmental benefits. While the financing scale of green bonds may be smaller than that of conventional bonds, the low coupon rates and short capital occupation time result in lower total financing costs compared to conventional bonds, saving financing costs for bond issuers and thus allowing for economic benefits. Additionally, findings derived from the Random Forest Method and Decision Tree Algorithm revealed that the scale of green bond issuance has a more substantial impact on ESG scores than interest rates and maturity terms. Conversely, the financing term has a significantly greater effect on CO2 emission equivalents compared to issuance volume and interest rates. Moreover, the characteristics of the bonds, the industry, and national factors of different issuing entities also vary in their influence on ESG scores and CO2 emissions.

The main theoretical contribution of this article lies in applying the “rational actor” hypothesis and starting from the profit motive of businesses to subdivide the motivation behind the issuance of green bonds by issuers into environmental and economic benefits. It further examines the environmental performance differences of green bonds before and after the introduction of carbon neutrality policies. On this basis, it categorizes the types of bond issuers and discusses the interplay between morality and profit in the issuance of green bonds. The research-based recommendations suggest that policymakers should enhance carbon reduction measures, establish frameworks to combat greenwashing, and integrate CO2 emissions and ESG criteria into assessment systems. Finally, particular focus should be placed on the carbon footprint of entities in low- and middle-income countries and the manufacturing sector to promote the sustainable growth of green finance.

Literature review

Green finance and sustainable development

Why do we care about environmental finance? Because it is an important part of sustainability, and sustainable financing is a key component of sustainable development. Without sustainable financing, little happens (Cowan, 1998). The process of economic development has promoted economic growth while also driving improvements in social, political, and population quality (Feldman et al., 2015). While we celebrate the achievements brought about by economic development, we must also recognize its negative impact on the environment, such as greenhouse gas emissions, soil, air, and water pollution, overexploitation of land, disorderly and excessive urban growth, depletion of natural resources, and many others. All these issues have caused various problems for global society, which manifest as different risk factors (Charfeddine and Mrabet, 2017). To seek ways for coordinated economic and environmental development, the concept of sustainable development has been proposed. However, economic organizations that seek sustainable development are often constrained by funding issues (Hafner et al., 2020; Dhutta et al., 2023). The insufficient allocation of financial resources to green projects has hindered the progress of sustainable economic development (Han and Gao, 2024). In order to address the financing issues of green projects, green finance has emerged.

The concept of green finance was first proposed by Salazar (1998). He believed that environmental finance represents an innovation in the financial industry aimed at meeting the financing needs of environmental protection, establishing a bridge between financiers and environmental initiatives. Subsequently, Cowan (1998) summarized green finance as “an interdisciplinary field between green economy and finance,” mainly exploring the financing of the green economy. Labatt and White (2002) believed that green finance is a financial tool based on market research to improve environmental quality and transfer environmental risks. In 2013, the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP-FI) and the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) convened the “International Finance Dialogue” in Geneva. During this event, it was recognized that “green finance” is often synonymous with “green investment,” referring to investments made in the environmental products and services sector. Price Waterhouse Coopers Consultants (PWC) in the 2013 report “Exploring Green Finance Incentives in China” pointed out that “For the banking sector, green finance is defined as financial products and services, considering environmental factors throughout the lending decision-making, ex-post monitoring, and risk management processes, provided to promote environmentally responsible investments and stimulate low-carbon technologies, projects, industries, and businesses.” Zadek (2014) noted that while green finance is frequently equated with green investment, its scope extends beyond investments as defined by Bloomberg New Energy Finance and other sources. Despite the lack of a universally agreed definition of green financing, there is consensus on its role as a financial mechanism to advance environmental improvements within the framework of sustainable development. As Cowan (1998) highlighted, environmental economics informs societal decisions, while environmental finance addresses the financial aspects of implementing those decisions.

Green finance, as a strategic financial instrument, has been widely recognized for its positive impact on the environment and the economy. Studies emphasize the role of the green finance industry in promoting the coordinated and sustainable development of the economy, society, and environment from various aspects (Labatt and White, 2002). In terms of environmental impact, green finance has been shown to improve air quality (Chen et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2022) and plays a significant role in reducing carbon emissions by encouraging companies to develop green technologies and adjust industrial structures, which is crucial for further improving air quality (Wu, 2022; Xu et al., 2023). With its long-term investment principles, green finance can achieve environmental benefits, drive green innovation, improve energy consumption and related environmental effects, making it an important means to achieve sustainable development goals and a green economy (Wang et al., 2021; Akomea-Frimpong et al., 2022). In terms of the economy, green finance is an important means to achieve a low-carbon economy and a climate-resilient economy (Simionescu and Gavurová, 2023) and plays a significant role in promoting the harmonious coexistence of the economy and the environment (Zhou et al., 2020). Additionally, green finance provides a framework for financing environmentally sustainable development projects (Simionescu and Gavurová, 2023). By supporting low-carbon development, green finance enhances the competitive advantage of enterprises (Soundarrajan and Vivek, 2016), offering them access to low-cost financing, which gives businesses the opportunity to invest in environmentally friendly projects (Wu, 2022). It also stimulates the creation of more jobs, thereby promoting economic growth (Yin and Xu, 2022). Naturally green finance can significantly enhance a company’s sense of social responsibility, thereby affecting the efficiency of its investment decisions, especially in sustainable projects (He et al., 2022). Green finance can also alleviate financing constraints for companies, promoting their R&D innovation and encouraging their R&D activities, thus enhancing their green competitiveness (Liu and Wang, 2019; Zhang, 2021; Taghizadeh-Hesary and Yoshino, 2019).

Green bonds and sustainable development

Green bonds, which often have a long-term focus on funding green projects, particularly green infrastructure, are one of the most suitable sustainable investment tools for combating climate change while supporting the stability of the financial system (Wu, 2022). Moreover, issuers are increasingly interested in the impact of the “green label” of green bonds on financing. Maltais et al. (2020) highlights that green bonds are seen as encouraging issuers to elevate their “green ambitions.” Issuers of green bonds often expect to issue at lower capital costs due to the positive impact of green projects on sustainability, low-carbon development, and environmental risk management. They also anticipate obtaining long-term financing (Wu, 2022; Sun et al., 2022) and securing extended timeframes for financing (Sartzetakis, 2020). Therefore, the issuance of green bonds should be effective for both, the environment and the economy. Issuing green bonds can reduce the cost of capital for issuing companies, leading to economic benefits. At the same time, there is considerable market demand for green bonds, and from a self-benefit perspective, the issuing entities would opt for green bond issuance. Concerning the environmental benefits of green bonds, some scholars suggest that there is suspicion of greenwashing in green bond issuances (Walker and Wan, 2012; Nyilasy et al., 2014), suggesting that companies issue green bonds to enhance their “green sustainable” image. When green bonds are used as a greenwashing tool, the credibility of green bonds will be undermined, and investors may overlook the green label (Dorfleitner et al., 2022). One of the two major challenges for the green bond market is to ensure its environmental integrity to mitigate the greenwashing criticism that could threaten its survival (Shishlov et al., 2016). While attention has been focused on how to avoid or reduce the adverse effects of greenwashing and condemn companies for misrepresenting themselves as green, Fatica and Panzica (2021) have conducted research on the environmental benefits of green bonds with optimistic results, showing reductions in carbon emissions by green issuers, indicating that the issuance of green bonds signifies a credible commitment to climate-friendly corporate behavior. Nevertheless, there is still limited research on the environmental effects of green bonds, and further exploration is needed on whether green bonds are simply tools for businesses to engage in greenwashing practices.

Comparative research on green bonds and conventional bonds

Once bonds were categorized by their financing purposes, research into comparing different types of bonds commenced. Scholars often use matching methods to compare and analyze green bonds with conventional bonds by controlling factors such as bond maturity, issuer characteristics, and currency features. In terms of research conclusions, Wu (2020) observes the reaction of stock markets to the issuance of green bonds and uses regression analysis to identify factors affecting the green bond premium. The results suggest that the issuance of green bonds may reduce the issuer’s stock returns. However, no significant negative green bond premiums were found for both the Chinese and global markets, indicating that green bonds are not noticeably underpriced compared to conventional bonds. Sun et al. (2022) emphasize that the cost of financing green bonds is lower than conventional bonds in the issuance market, but the green label does not bring a greenium to green bonds, in contrast to the findings of Gianfrate and Peri (2019). In addition to comparing bond prices, there is extensive research from other perspectives. Zerbib (2019) compares the liquidity of green bonds and conventional bonds from the perspective of investor preferences. Hachenberg and Schiereck (2018) compare the risk-return profiles of green bonds and conventional bonds and find that green bonds did not trade significantly tighter than conventional bonds, but ESG ratings had a greater impact on the credit spreads of green bonds. Yeow and Ng (2021) use PSM and DID models to compare green bonds with conventional bonds and find that green bonds are effective in improving environmental performance, especially when certified by third parties, but they do not have an impact on financial performance.

Theoretical background and hypothesis development

Theoretical background

The “rational actor” hypothesis suggests that individuals (or businesses) make decisions by logically assessing their options to maximize their utility - whether that be profit, satisfaction, or another objective - and traditionally views businesses as entities focused on maximizing profits. However, in the era of sustainable development, corporate goals have expanded to include environmental stewardship as a key measure of success. With environmental concerns intensifying, green bonds have emerged as a crucial financial instrument for funding eco-friendly projects, drawing significant interest from both businesses and investors. While continuing to deliver value to shareholders, corporations now also address the interests of a broader range of stakeholders by prioritizing transparency in their ESG performance. These disclosures help combat information asymmetry, providing investors with critical insights that promote more informed and efficient investment decisions. Additionally, the theory of information asymmetry further emphasizes the need for external stakeholders to access decision-relevant information. This demand has driven companies to proactively disclose their ESG performance, enabling stakeholders to make more informed decisions based on transparency.

Guided by this theoretical framework (Fig. 1), this paper conducts an in-depth exploration of whether the issuance of green bonds has indeed achieved the dual objectives of economic and environmental benefits, and examines the intricate relationship between ESG disclosures and green bonds. This analysis aims to illuminate the effectiveness of these financial instruments in aligning corporate strategies with sustainable growth.

Hypothesis development

The label of green bonds is undoubtedly the main characteristic that distinguishes them from conventional bonds. However, whether green bonds have achieved a green effect under the green label or not is still worth exploring. At the end of 2015, the Paris Agreement, reached by countries around the world, called for all nations to limit the rise in global average temperature and strive to achieve the goal of carbon net-zero emissions. Achieving net-zero emissions has become a critical objective for energy and emissions policies worldwide due to its increasing significance (Tiwari et al., 2024). Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the major greenhouse gas and is different from many other air pollutants that we in environmental economics and environmental protection are accustomed to dealing with (Cowan, 1998). Currently, the measurement of greenhouse gas emissions has become an important way to gauge the environmental effectiveness of green instruments. Several studies have explored achieving Net Zero Emissions (NZE) and its impact on sustainable development (Zuo et al., 2012; Gupta et al., 2020). Green bonds, by definition, are intended to support environmental protection, prompting theoretical inquiries into their actual environmental benefits. To formulate more specific hypotheses, we rely on the findings of Fatica and Panzica (2021), who analyze the environmental benefits of green bonds by measuring CO2 emissions. Additionally, studies by Labatt and Watts (2002), Cheng et al. (2022), Tang and Zhang (2020), Flammer (2021) suggest a correlation between issuers of green bonds with strong ESG performance and better environmental outcomes, including lower CO2 emissions. Hence, to examine the practical impact of green bonds on environmental protection, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: The issuance of green bonds following the implementation of net-zero carbon policies contributes to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

H2: Issuers of green bonds tend to have higher ESG ratings.

H3: Issuers of green bonds demonstrate better control over carbon dioxide emissions.

Through the examination of Hypothesis 1, a comparison of CO2 emissions between green and conventional bonds before and after the introduction of carbon neutrality policies will be conducted to explore the responsiveness of bond financing to carbon emission policies to investigate whether there is an issue of greenwashing associated with green bonds. By examining Hypotheses 2 and 3, the relationship between the issuance of green bonds and both ESG ratings and carbon emissions can be scrutinized. If the issuance of green bonds is associated with higher ESG ratings and a reduction in carbon emissions, this would suggest that green bonds are indeed contributing to environmental protection and would refute the concept of greenwashing. On the contrary, if the issuance of green bonds does not correlate with an improvement in ESG ratings or a decrease in carbon emissions, it may imply that such issuances are merely a form of greenwashing.

Is the issuance of green bonds profitable? This question has sparked a discussion on the economic viability of green bonds, leading to a debate on the issue of the greenium (Gianfrate and Peri, 2019; Sun et al., 2022). Sangiorgi and Schopohl, (2023) emphasize that the financing cost of green bonds is lower than that of conventional bonds in the issuance market, but the green label does not confer a greenium to green bonds. In contrast, Sun et al., (2022) and Gianfrate and Peri, (2019) believe that there is a green premium associated with green bonds. Thus, the issue of the green premium remains contentious. To further investigate the issue of the green premium, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Green bonds are associated with lower financing costs.

Hypothesis 4 is based on the characteristics of bonds themselves. By analysing the features of green bonds and comparing their advantages and disadvantages in terms of financing scale, coupon rates, and maturity, it can be determined whether the issuance of green bonds entails economic benefits for issuers.

Methodology

Since both green information disclosure and green bonds are essential in the era of sustainability, the question arises of how to link them. By using a coordinate system and applying the principle of dummy variables, the disclosure of ESG information and the issuance of green bonds can be combined. The disclosure of ESG information is defined as 1, and non-disclosure as 0, while the issuance of green bonds is defined as 1, and non-issuance as 0. As shown in Fig. 2, the four quadrants represent four combinations of ESG disclosure and green bond issuance. By analysing the data within each combination and between different combinations, the relationship between ESG information disclosure and green bond issuance can be studied.

Note: This is the ESG and Green Bond Interaction Diagram. The horizontal axis represents the disclosure of ESG information, and the vertical axis represents the issuance of green bonds. The numerical combinations within different quadrants represent different combinations of ESG disclosure and green bond issuance.

For the purpose of this research, we have focused on data samples from Quadrant 1 and Quadrant 4. Quadrant 1 samples consist of issuers who disclose ESG information and issue green bonds simultaneously, while Quadrant 4 samples consist of issuers who disclose ESG information but issue conventional bonds. After categorizing the bond issuers, we have conducted specific analyses on samples from different quadrants. During the data sorting process, we have identified a special group of issuers who issue both green bonds and conventional bonds, and they account for a significant proportion of the issuers of green bonds. Therefore, this group was treated as a separate category for data sorting and analysis. In Fig. 3, the green circles represent issuers of green bonds, the brown circles represent issuers of conventional bonds, and the overlapping section represents issuers who issue both types of bonds, referred to as overlapping issuers. Based on the different categories of bond issuance by the issuers, they were classified into three groups: issuers exclusively issuing green bonds, issuers exclusively issuing conventional bonds, and those who issue both types of bonds.

Note: The green circle represents the issuers of green bonds, totaling 420. The brown circle represents the issuers of conventional bonds, totaling 3268. The intersecting portion of the two circles represents the 330 entities that have issued both green and conventional bonds. Group A consists of 90 bond issuers who issued green bonds after deducting 330 from 420. Group B consists of 2938 bond issuers who issued conventional bonds after deducting 330 from 3268. Group C consists of 330 bond issuers who simultaneously issued both types of bonds.

The research is divided into seven steps:

Step 1. Grouping: Entities that issue only green bonds are classified as Group A; entities that issue only regular bonds are classified as Group B; entities that issue both types of bonds are classified as Group C.

Step 2. Variable Design: Design variables based on data characteristics and hypotheses for the study.

Step 3. Descriptive Analysis: Perform descriptive statistical analysis on different categories of data, compare differences between variables in different groups, and seek evidence to validate the hypotheses.

Step 4. Correlation Testing: Test the correlation between variables to prepare for regression analysis.

Step 5. Difference-in-Differences Analysis: The DID test is used to compare and analyze the greenhouse gas emissions of bond issuers before and after the introduction of zero-carbon emission policies.

Step 6. Regression Analysis: Conduct a regression analysis on all groups, establish relationships between variables, and seek evidence to validate the hypotheses.

Step 7. Robustness tests.

Data and analysis

Data and variables

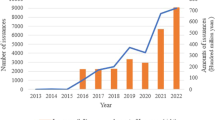

The analysis in this paper is based on data obtained from the Refinitiv database for the period 2013–2023, focusing on green bonds and conventional bonds issued by non-financial entities that disclose ESG information. The specific steps are as follows: a) Utilizing the Refinitiv Green Bonds database, collect information on green bonds issued between 2013 and 2023, including bond characteristics and issuer details. Use Excel to compile a list of unique issuers. b) Using the Refinitiv Bonds database, gather information on conventional bonds issued between 2013 and 2023, including bond characteristics and issuer details. Again, use Excel to create a list of unique issuers. c) Retrieve ESG ratings and CO2 emissions data for entities that disclose ESG information between 2013 and 2023 using the Refinitiv database. d) Determine the category of each entity. Use Excel to match the issuers of green bonds with those of conventional bonds, identifying overlap and categorizing issuers into three groups: those exclusively issuing green bonds, those exclusively issuing conventional bonds, and those issuing both green and conventional bonds. e) Match the data, combining bond characteristics, ESG ratings, and CO2 emissions for different categories of issuers. Exclude any data that is unavailable or incomplete to obtain a final research sample.

As shown in Table 1, there are 420 entities that issue green bonds, and a total of 3268 entities that issue regular bonds. Among them, there are 330 entities that overlap and issue both types of bonds (Group C). There are 815 issuances of green bonds and 4924 issuances of regular bonds. There are 90 entities (Group A) that exclusively issue green bonds, with a total of 208 green bond issuances. There are 2938 entities (Group B) that exclusively issue regular bonds, with a total of 15,724 regular bond issuances. After excluding unavailable data for the bonds issued by different entities, Group A has 182 green bond issuances, Group B has 12,054 regular bond issuances, and Group C has 658 green bond issuances and 3815 regular bond issuances.

Table 2 shows the variables and their explanations needed for this study. Among them, Bond, industry, country and policy are dummy variables. The Bond dummy variable is used to distinguish between issuers of green bonds and non-green bonds, as well as to differentiate the ESG performance, CO2 emissions, and bond characteristics of different issuer categories. The industry dummy variable categorizes the industries of bond issuers into manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors, providing a basis for discussing the characteristics of different industry issuers. The Country dummy variable distinguishes the national characteristics of bond issuers, with 1 representing developed countries and 0 representing developing countries. Policy is also a dummy variable, the year 2016 and subsequent years is 1, other is 0. ESG represents the ESG score, ranging from 0 to 100, which quantifies and visually measures the environmental, social, and governance performance of bond issuers, especially in terms of the environmental governance effects of issuing bonds, particularly green bonds. CO2 is the variable representing the greenhouse gas emissions of bond issuers, providing a quantified indicator that is crucial for measuring the environmental benefits of issuing green bonds. Scale, term, and rate provide specific descriptions of bond characteristics. Scale refers to the issuance amount of bonds, term represents the duration of bond issuance, and rate denotes the coupon rate of the bond. They serve as indicators for measuring the economic features of bonds.

Descriptive analysis

Table 3 provides statistical analysis on the mean values of variables for the three groups of entities. In terms of the issuance amount of bonds, Group B has the highest issuance amount (5.4*108), followed by C-1 in Group C (3.5*108), C-0 in Group C (4.1*108), and the lowest amount is in Group A (2.7*108). The scale of green bonds is smaller than conventional bonds. Regarding coupon rates, the lowest rate is in C-1 in Group C (2.58%), followed by C-0 (2.64%), then Group A (3.04%), with the highest rate in Group B (3.56%). When comparing Groups A and B, as well as the green bonds within Group C, the coupon rates are all lower than conventional bonds. For bond maturity, C-0 in Group C has the longest maturity (12.51 years), followed by Group B (10.55 years), then C-1 (9.66 years), with Group A having the shortest maturity (7.54 years). The financing term of green bonds is shorter than conventional bonds. In terms of ESG ratings, Group A has the highest score (64.95), followed by Group C (61.25), and Group B has the lowest score (61.09). Issuers of green bonds demonstrate better overall ESG performance. Regarding CO2 emissions, Group C has the highest emissions (283.45), followed by Group B (221.83), and Group A has the lowest emissions (117.73). When comparing Groups A and B, entities issuing green bonds perform better in CO2 emissions. However, looking at the results of Group C, it appears that issuing green bonds does not improve the CO2 emissions of entities that have issued conventional bonds. Further discussion is needed to determine whether the issuance of green bonds by such entities is a form of greenwashing. There are no significant differences in country and industry classifications among the groups.

In conclusion, green bonds have characteristics such as lower financing costs compared to conventional bonds, with issuers who solely issue green bonds having the lowest financing costs. From a financing cost perspective, issuing green bonds is economically beneficial for the issuers. Issuers of green bonds demonstrate better ESG performance, and entities issuing only green bonds perform better in CO2 emissions compared to issuers of conventional bonds, resulting in environmental benefits from issuing green bonds. It is worth noting that, although Group C has a slightly higher ESG rating than Group B, their CO2 emissions are significantly higher than those of Group B. This suggests that issuing green bonds may not lead to environmental benefits for entities in Group C that have also issued conventional bonds.

Correlation analysis

Tables 4–6 present the results of Pearson correlation analysis for variables in Groups A, B, and C. Comparing the correlation test results of the three groups, the highest degree of correlation is observed in Group C, where only ESG and country show no significant correlation, while other variables exhibit significant correlations at different confidence levels. Group B also shows good correlation, with some exceptions such as no correlation between rate and term, ESG, and CO2, and no correlation between term and ESG or industry and country. Other variables in Group B demonstrate varying degrees of correlation. In the correlation test for variables in Group A, only two variables show significant correlation at a 1% confidence level: financing scale is significantly negatively correlated with coupon rate (−0.255), and CO2 is significantly negatively correlated with the country of establishment (−0.299). At a 5% confidence level, four variables show significant correlation: scale is significantly positively correlated with ESG (0.172), rate is significantly negatively correlated with ESG (−0.188), and ESG is significantly positively correlated with the country (0.038). From the results of the correlation tests, it can be observed that the variables in the three groups display different levels of correlation. In Group C, which includes both green bonds and conventional bonds, the correlation between variables is the most significant, indicating significant mutual influence among the variables. Group B follows with significant correlations between the characteristics of entities issuing conventional bonds (ESG, CO2 emissions, country of establishment, industry) and the financing scale and duration of bonds. Group A, which consists of entities issuing green bonds, shows a lower level of significance in the correlations between the entity’s characteristics (ESG, CO2 emissions, country, industry) and the bond’s characteristics (scale, rate, term) compared to Groups B and C.

Regression analysis

Model 1, established to observe the impact of bond issuance on greenhouse gas emissions following the proposal of carbon net-zero emission policies, utilizes a difference-in-differences (DID) approach as follows:

Y-CO2 it represents the carbon dioxide emissions of the i entity at time t. The independent variable Bond is a dummy variable, taking the value of 1 if the bond is a green bond, and 0 otherwise. The independent variable Policy is also a dummy variable, taking the value of 1 if the time is in or after the year 2016, and 0 otherwise. The interaction term Bond × Policy represents the core of the DID estimation, measuring the difference in CO2 emission changes between the green bond group and the non-green bond group after the policy implementation. β0 represents the constant term, β1 represents the treatment effect, reflecting the difference in CO2 emissions between the green bond group and the non-green bond group before the policy implementation. β2 represents the time effect, reflecting the change in CO2 emissions for all groups after the policy implementation in 2016 compared to before. β3 is the DID coefficient, which is the focus of our study, measuring the difference in CO2 emission changes between the green bond group and the non-green bond group after the policy implementation, thereby providing a causal estimate of the policy effect. β4 represents the coefficients for control variables, which are used to control for other factors that may affect CO2 emissions. Finally, ϵit represents the error term, capturing the unobserved random variation in the model.

Model 2 analyses the factors influencing ESG scores, where the dependent variable is Y-ESG and the independent variables are bond, scale, term, and rate. In this model, bond is a dummy variable taking a value of 1 for green bonds and 0 otherwise. The control variables include industry and country. Industry is a dummy variable taking a value of 1 for the manufacturing industry and 0 otherwise. Country is also a dummy variable taking a value of 1 for high-income countries and 0 otherwise. ε represents the error term, i and j respectively represent the issuer and the bond, β0 is the constant term, and β1 to β6 represent the coefficients of the variables.

Model 3 analyses the factors influencing CO2 emissions, with the dependent variable Y-CO2 and the independent variables ESG, scale, term, and rate. In this model, bond is a dummy variable taking a value of 1 for green bonds and 0 otherwise. The control variables include industry and country. Industry is a dummy variable taking a value of 1 for the manufacturing industry and 0 otherwise. Country is also a dummy variable taking a value of 1 for high-income countries and 0 otherwise. ε represents the error term, i and j respectively represent the issuer and the bond, β0 is the constant term, and β1 to β7 represent the coefficients of the variables.

Table 7 reveals that the difference-in-differences treatment effect value is −3.415 and is not statistically significant, indicating that there has been no significant change in CO2 emissions following the issuance of bonds after the proposal of carbon net-zero emission policies. However, it is noteworthy that after 2016, the effect value for the treatment group is lower than that for the control group and lower than before 2016. Although the CO2 emissions did not show statistical significance according to the results of the DID model, the issuance of green bonds resulted in a reduction in the treatment effect value. However, this reduction is negligible when compared to the total emissions.

Table 8 presents the OLS regression results of DID estimation, where the F-statistic is 52.325 with a p-value of 0.000, indicating that the model is statistically significant overall. The coefficient for ‘coupon’ is 2.429, significantly positively affecting the dependent variable, while the coefficient for maturity is 0.061, which is not significant. The coefficient for amount is −13.917, significantly negatively influencing the dependent variable. The coefficients for ‘ESG-s’ and the environmental and social factors are −0.369 and 0.233, respectively, both significantly positively affecting the dependent variable. The influence of industry and country is significant, with coefficients of 47.905 and −47.615, respectively, where the former has a positive impact and the latter a negative impact. The coefficient for bond is 2.948, and for policy it is −9.225, with the latter significantly negatively affecting the dependent variable. The interaction term between bond and policy has a coefficient of −3.415, but it is not significant. Overall, the model explains 3.2% of the variability, and the adjusted R-squared is the same, indicating that the model’s explanatory power for the dependent variable is limited when controlling for other variables.

The least squares method is widely used in economic research because it quantifies the extent to which the dependent variable changes in response to a one-unit change in the corresponding independent variable. By estimating the linear relationship between variables, this method can predict the dependent variable’s values based on the independent variable(s). Therefore, the least squares method is often applied to test and estimate the linear relationships in research models. Table 9 presents the test results of models 2 and 3 using the least squares method. Columns (1), (2), and (3) represent the regression results of model 2 on the data for groups A, B, and C, respectively, indicating the impact of each variable on ESG scores. Columns (4), (5), and (6) represent the regression results of model 2 on the data for groups A, B, and C, respectively, indicating the impact of each variable on CO2 emissions equivalent.

The values of R² and Adjusted R² are relatively low, indicating a low level of curve regression fit. In the results of the F-test, the P-value is significant at a 5% level, rejecting the null hypothesis of a regression coefficient being zero. Therefore, the model largely meets the requirements. The overall evaluation of R² and F-test indicates that Models 2 and 3 are well-constructed and generally conform to the research design.

Columns (1), (2), and (3) respectively correspond to the testing results of Groups A, B, and C for Model 2. In terms of the impact of bond characteristics on ESG scores, regarding scale, both Groups B and C show a significant negative correlation with ESG scores at a 1% confidence level, with Group B (−0.003) having a slightly greater impact than Group C (−0.001), while Group A shows a positive correlation between scale and ESG scores, indicating that issuing green bonds can promote ESG scores. As for bond yields, Groups A and B have a significant negative correlation with ESG scores at the 10% and 1% confidence levels, while Group C’s rate is positively correlated with ESG scores, with Group A (−1.12) having a greater impact than Group B (−0.571), suggesting that issuing entities that only issue green bonds can improve ESG scores while maintaining lower issuance rate. In terms of financing term, Group A shows a positive correlation (0.207) with ESG scores, while Groups B and C exhibit a significant negative correlation with ESG scores at a 1% confidence level. Issuing only green bonds can enhance ESG scores by extending the financing term of green bonds. Regarding the country of origin of the issuer, Groups B and C are significantly positively correlated with ESG scores at a 1% confidence level, while Group A is negatively correlated, indicating that bond issuers from non-high-income countries can improve ESG scores through the issuance of green bonds, especially those issuers who exclusively issue green bonds. The industry of Group A issuers is significantly positively correlated with ESG scores at a 10% confidence level, while Group B is negatively correlated. Group C shows a significant negative correlation at a 5% level. Notably, in Group C, the issuance of green bonds is significantly positively correlated with ESG scores, suggesting that manufacturing entities are more inclined to issue only green bonds to enhance their ESG scores. From the regression results of Model 3, issuers in Group A who issue large-scale, low-yield, long-term green bonds achieve higher ESG ratings, while issuers in Group B who issue small-scale, low-yield, short-term conventional bonds can obtain higher ESG ratings. In Group C, which issues a mix of green bonds and conventional bonds, the regression indicators of each variable fall between those of Groups A and B, indicating that issuing green bonds can improve the ESG levels of issuers of conventional bonds.

Columns (4), (5), and (6) correspond to the test results for groups A, B, and C in relation to model 2. From the results, it can be observed that ESG scores are negatively correlated with CO2 emissions, with group C showing significant negative correlation at a 1% confidence level. Scale is significantly negatively correlated with CO2 emissions. Concerning bond rate, groups A and C show significant negative correlation at 5% and 1% confidence levels, respectively, while group B shows significant positive correlation at a 1% confidence level. In terms of term, the term of bonds in group A is positively correlated with CO2 emissions, while groups B and C exhibit negative correlation. Regarding the country where the issuer is established, both groups A and C show significant negative correlation at the 1% confidence level, while industry shows positive correlation, with groups B and C exhibiting significant positive correlation at a 1% confidence level. The issuance of green bonds in group C shows a very weak positive correlation with CO2 emissions. Based on the regression results of model 3, entities with higher ESG scores tend to have lower CO2 emissions. Issuers that only issue green bonds have a stronger indication of CO2 emissions reduction. Entities that issue large-scale, high-yield, and short-term green bonds demonstrate better carbon management capabilities. For entities that issue both conventional and green bonds, the issuance of green bonds shows weaker positive correlation with CO2 emissions, indicating that greenwashing behavior requires further investigation.

Based on the regression analysis of our model, we observed significant variations in the correlation of variables across diverse groups. To better understand the mechanisms by which the explanatory variables influence the dependent variables, we have explored the following research avenues. Firstly, we utilized the decision tree algorithm from the machine learning suite to evaluate the influence of bond characteristics on ESG ratings and CO2 emissions equivalents across distinct groups. The analysis, as depicted in Figs. 4 and 5, reveals that the issuance volume of green bonds exerts the most significant impact on ESG ratings (41.63%), outweighing the other groups. This is trailed by the issuance rate (38.08%), whereas the influence of maturity is the most minimal (20.29%), ranking below the other groups. These insights suggest that ESG ratings are substantially swayed by the scale of green bond financing, whereas for conventional bonds, the interest rate (40.37%) holds a more pronounced influence on ESG ratings. Furthermore, our examination of the impact of bond characteristics on CO2 emissions indicates that the financing tenure of green bonds has a markedly substantial effect on CO2 emissions (63.99%). This underscores the necessity for an extended timeframe to realize the environmental benefits of green bonds, a patience that the market appears to extend to such instruments. Conversely, for conventional bonds, the interest rate factor (38.07%) and the scale of issuance (35.24%) emerge as pivotal determinants of CO2 emissions.

To further explore the impact of coupon rate, transaction size, maturity, industry, and country on ESG ratings and CO2 emissions, we employed the random forest algorithm from the machine learning arsenal. This approach allowed us to meticulously analyze and assess the heterogeneous effects of control variables on the dependent variables. Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the distribution of influence weights for these control variables on ESG ratings and CO2 emissions, respectively. The analysis reveals notable disparities in the impact weights, with bond-specific characteristics significantly outstripping the effects of industry and national factors. In ESG rating analysis, Group A exhibits a more substantial influence from the scale factor (40.36%) compared to the other groups (30.94%, 33.57%). Meanwhile, Group B shows a particularly strong effect from the coupon rate (37.15%) and maturity (26.42%) factors. When examining CO2 emissions, Group A again has a marked influence from the coupon rate (41.28%) and maturity (29.69%) factors. Although Group C indicates a slightly more significant impact from the scale factor (30.35%), this difference is not markedly pronounced. It is also noteworthy that the influence of the industry factor varies among the groups, with Group C experiencing the most considerable effect from this factor.

Robust test

In order to enhance the robustness of the conclusions, a different regression method was chosen to retest the experimental samples. Ridge regression (also known as Tikhonov regularization) was employed for regression analysis in the robustness test. This method is essentially an improved least squares estimation method that sacrifices the unbiasedness of least squares in order to obtain regression coefficients that are more practical and reliable. Table 10 presents the results of the robust regression, which are largely consistent with the results of least squares regression, indicating that the regression results of this study are reasonably robust.

Conclusion

This article explores two main questions, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding of the issues under consideration. The first question investigates the extent to which the issuance of green bonds contributes to environmental protection, with particular emphasis on evaluating their effectiveness after the adoption of net-zero emission policies. The second question investigates whether entities issuing green bonds achieve measurable economic benefits. To address these questions in a systematic and thorough manner, the study developed and tested four specific hypotheses.

In examining the first hypothesis, the DID analysis revealed no significant impact on greenhouse gas emissions from the issuance of either green bonds or conventional bonds, even after the introduction of carbon net-zero emission policies. As a result, there is insufficient evidence to support this hypothesis. Nonetheless, this finding remains significant and warrants attention. It appears that this substantial carbon reduction policy has not exerted enough pressure on bond issuers to reduce emissions. However, a more detailed analysis throughout this paper reveals that issuers exclusively focusing on green bonds tend to have higher ESG ratings, supporting the second hypothesis, and exhibit the lowest CO2 emissions equivalents. Moreover, the ESG ratings of entities issuing green bonds are negatively correlated with CO2 emissions equivalents (Flammer, 2021). Hence, in terms of CO2 emissions, green bonds appear to play a significant role, and the moral effect of the green label is evident. Interestingly, entities issuing both conventional and green bonds do not demonstrate the same level of environmental benefits, suggesting that only those exclusively focusing on green bonds can achieve significant environmental gains. This finding raises the possibility that entities issuing both green and conventional bonds may engage in behaviours contrary to environmental protection under the guise of green bonds, therefore justifiably considered as greenwashing. Further findings indicate that bond issuers from high-income countries perform better in CO2 emission reduction, with the performance of the manufacturing industry however, raising many concerns. This discrepancy may be attributed to stricter carbon reduction requirements in high-income countries and greater investments in resources and technologies. For the manufacturing industry, however, achieving substantial carbon emission reductions in the short term remains challenging with current production methods.

Regarding the third hypothesis, it was found that only group A (exclusively green bond issuers) supports it, which is consistent with the findings discussed above. When comparing groups, A and C (Dual Bond Issuers), it can be observed that the financing scale of green bonds is lower than that of conventional bonds, with higher coupon rates and shorter funding durations. Overall, the financing costs associated with green bonds are lower than those of conventional bonds (Sun et al., 2022; Sangiorgi and Schopohl, 2023). Moreover, the findings supporting Hypothesis 4 indicate that green bond financing can lead to economic benefits for bond issuers, particularly in terms of reduced total financing costs.

In conclusion, entities exclusively issuing green bonds outperform those issuing conventional bonds in terms of ESG ratings, financing costs, and CO2 emissions management, thereby achieving both economic and environmental benefits. Conversely, entities issuing both green and conventional bonds tend to exhibit higher CO2 emissions intensities compared to those solely issuing conventional bonds, suggesting that, for dual bond issuers, green bond issuance may serve as a form of greenwashing.

After reviewing the findings of this study, we recommend that policymakers focus on several key areas to enhance environmental and economic sustainability. Monitoring the effects of carbon neutrality initiatives should be a priority. This includes establishing stringent greenhouse gas emission standards, introducing incentive mechanisms to encourage low-carbon actions by businesses, and continuously tracking and evaluating the effectiveness of these measures to ensure the achievement of net-zero emissions. Additionally, improving the quality of ESG information disclosure is crucial for the sustainable development of enterprises.

At the same time, the progress achieved and ongoing updates within the European Union in this field are directly relevant to this research. From the 2014 Non-Financial Reporting Directive to the 2022 Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and the adoption of the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) in 2024 for large public-interest companies, each step has progressively elevated the standards and requirements for ESG information disclosure. It is important to note that the ESRS framework will be expanded in the future to include other types of companies, further broadening the scope of sustainability reporting requirements while simultaneously increasing the relevance of this study. Notably, both the ESRS and green bonds share the objective of aligning corporate activities with the EU’s sustainability goals, as outlined in the European Green Deal and the Paris Agreement. These initiatives also aim to assist investors and stakeholders in evaluating a company’s sustainability performance. Furthermore, the ESRS provides a standardized reporting framework that ensures consistency and comparability in disclosures, a feature particularly valuable to green bond issuers and investors alike. Lastly, our research indicates that the issuance of green bonds has a positive impact on environmental protection, but there is also a risk of enterprises engaging in greenwashing. To regulate the issuance and supervision of green bonds, the European Commission issued the EU Green Bond Regulation in 2023, providing clear standards for market participants to reduce greenwashing behavior. Based on this, policy formulation should focus on balancing the economic and environmental aspects of green bonds. Mandatory certification procedures should be required for issuance, and comprehensive information disclosure should be enforced throughout their lifecycle. Particular emphasis should be placed on rigorously assessing their environmental attributes to ensure alignment with green objectives and achieve sustainability in both economic and environmental terms. Finally, policymakers should focus on creating a robust framework that integrates green bonds with broader sustainability goals. This would ensure that green bonds are not just financial instruments but also powerful tools for achieving the EU’s and other global climate objectives, while fostering long-term environmental and economic sustainability. By strengthening the regulatory landscape for green bonds and improving ESG reporting, policymakers can ensure that green finance contributes meaningfully to sustainable development.

Summarizing, by linking carbon reduction policies with the environmental impacts of bonds this study assesses how bond issuance affects greenhouse gas emissions after the implementation of carbon net-zero policies. Green bond issuance is also explored in terms of economic and environmental advantages and then bond issuers are assessed and categorized based on their bond types. Our paper demonstrates that bond characteristics have a greater impact on ESG ratings and CO2 emissions than industry and country factors, with green bonds providing superior environmental benefits compared to conventional bonds. The findings provide practical guidance for governments and other intergovernmental institutions, which should focus on regulating the effectiveness of carbon neutrality policies, developing an ESG information disclosure system, and enhancing the green bond issuance and regulatory framework.

Finally, the limitations of this study include the imbalance in sample sizes among different groups, which could affect results, and the focus on CO2 emissions equivalent as the sole indicator of environmental benefits without showing changes in greenhouse gas emissions before and after the issuance of green bonds. Future research in this field could explore whether entities issuing both conventional and green bonds engage in greenwashing behaviours, i.e., using green bonds for non-environmentally friendly purposes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

22 January 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04402-0

References

Akomea-Frimpong I, Kukah AS, Jin X, Osei-Kyei R, Pariafsai F (2022) Green finance for green buildings: A systematic review and conceptual foundation. J. Clean. Prod. 356:131869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131869

Bauer R and Hann D (2010). Corporate Environmental Management and Credit Risk. 1-44. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1660470 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1660470

Charfeddine L, Mrabet Z (2017) The impact of economic development and social political factors on ecological footprint: a panel data analysis for 15 MENA countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 76:138–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.031

Chen Y, Cheng L, Lee CC et al. (2021) The impact of regional banks on environmental pollution: evidence from China’s city commercial banks. Energy Econ. 102:105492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105492

Cheng LTW, Sharma P, Broadstock DC (2022) Interactive effects of brand reputation and ESG on green bond issues: A sustainable development perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 32(1):570–586. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3161

Cowan E (1998) Topical issues in environmental finance. EEPSEA Special and Technical Paper 43(3). http://203.116.43.77/publications/specialp2/ACF346.html

Dhutta A, Bouri E, Rothovius T, Uddin G (2023) Climate risk and green investments: new evidence. Energy 265:126376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.126376

Dorfleitner G, Utz S, Zhang R (2022) The pricing of green bonds: External reviews and the shades of green. Rev. Manag. Sci. 16(3):797–834. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00458-9

Fama EF, French KR (2007) Disagreement, tastes, and asset prices. J. Financial Econ. 83(3):667–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.01.003

Fatica S, Panzica R (2021) Green bonds as a tool against climate change? Bus. Strategy Environ. 30(5):2688–2701. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2771

Feldman M, Hadjimichael T, Lanahan L, Kemeny T (2015) The logic of economic development: a definition and model for investment. Environ. Plan. C. Gov. Policy l34(1):5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774x15614653

Flammer C (2021) Corporate green bonds. J. Financial Econ. 142(2):499–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.01.010

Gianfrate G, Peri M (2019) The green advantage: exploring the convenience of issuing green bonds. J. Clean. Prod. 219:127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.022

Gupta S, Gupta E, Sarangi GK (2020) Household Energy Poverty Index for India: An analysis of inter-state differences. Energy Policy 144:111592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111592

Hachenberg B, Schiereck D (2018) Are green bonds priced differently from conventional bonds? J. Asset Manag. 19:371–383. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41260-018-0088-5

Hafner S, Jones A, Anger-Kraavi A, Pohl J (2020) Closing the green finance gap - A systems perspective. Environ. Innov. Societal Transit. 34:26–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.11.007

Han J, Gao H (2024) Green finance, social inclusion, and sustainable economic growth in OECD member countries. Humanities Soc. Sci. Commun. 11(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02662-w

He L, Zhong T, Gan S (2022) Green finance and corporate environmental responsibility: evidence from heavily polluting listed enterprises in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29(49):74081–74096. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-21065-5

Loffler KU, Petreski A, Andreas S (2021) Drivers of Green Bond Issuance and New Evidence on the “Greenium. Eurasia. Economic Rev. 11:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40822-020-00165-y

Labatt S, White R (2002) Environmental Finance: A Guide to Environmental Risk Assessment and Financial Products. Canada, John Wiley and Sons

Larcker DF, Watts EM (2020) Where’s the greenium? Journal of Accounting and Economics 69(2-3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2020.101312

Liu X, Wang E (2019) Green credit policy, property rights and debt financing: Quasi-natural experimental evidence from China. Financial Res. Lett. 29:129–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2019.03.014

Maltais A, Nykvist B (2020) Understanding the role of green bonds in advancing sustainability. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 1(3):233–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2020.1724864

Menz K (2010) Corporate social responsibility: is it rewarded by the corporate bond market? A critical note. J. Bus. Ethics 96:117–134. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40836192

Mokni K, Mensi W, Hammoudeh S, Ajmi AN (2022) Green bonds and oil price shocks and uncertainty: A safe haven analysis. Int. Econ. 172:238–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2022.11.003

Nyilasy G, Gangadharbatla H, Paladino A (2014) Perceived greenwashing: the interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions. J. Bus. Ethics 125(4):693–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1944-3

Oikonomou I, Brooks C, Pavelin S (2014) The effects of corporate social performance on the cost of corporate debt and credit ratings. Financial Rev. 49:49–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/fire.12025

Pricewaterhouse Coopers Consultants (PWC) (2013): Exploring Green Finance Incentives in China. PWC

Ren X, Zeng G, Sun X (2023) The peer effect of digital transformation and corporate environmental performance: Empirical evidence from listed companies in China. Economic Model. 128:106515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2023.106515

Salazar J (1998) Environmental Finance: Linking Two World. In A Workshop on Finance Innovations for Biodiversity. Presente. a Workshop Financial Innov. Biodivers. Bratisl. 1:2–18

Sangiorgi I, Schopohl L (2023) Explaining green bond issuance using survey evidence: Beyond the greenium. The British Accounting Review 55(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2021.101071

Sartzetakis ES (2020) Green bonds as an instrument to finance low carbon transition. Economic Change Restruct. 2:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-020-09266-9

Shishlov I, Morel R, Cochran I (2016) Beyond transparency: unlocking the full potential of green bonds. Institute for Climate Economics Report. https://doi.org/10.13140/rg.2.2.11081.85606

Simionescu M, Gavurová B (2023) Pollution, income inequality and green finance in the new EU member states. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02197-6

S Zadek (2014) South-Originating Green Finance: Exploring the Potential. International Institute for Sustainable Development. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=70986691-7729-336b-9778-a97a89320390

Soundarrajan P, Vivek N (2016) Green finance for sustainable green economic growth in India. Agric. Econ. 62(1):35–44. https://doi.org/10.17221/174/2014-agricecon

Sun Z, Feng J, Zhou R, Yu Y, Deng Y (2022) Can labelled green bonds reduce financing cost in China? Sustainability (Switzerland) 14(20). https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013510

Tiwari S, Bashir S, Sarker T, Shahzad U (2024) Sustainable pathways for attaining net zero emissions in selected South Asian countries: role of green energy market and pricing. Humanities Soc. Sci. Commun. 11(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02552-7

Taghizadeh-Hesary F, Yoshino N (2019) The way to induce private participation in green finance and investment. Financial Res. Lett. 31:98–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2019.04.016

Tang DY, Zhang Y (2020) Do shareholders benefit from green bonds? Journal of Corporate Finance 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2018.12.001

Teti E, Baraglia I, Dallocchio M, Mariani G (2022) The green bonds: Empirical evidence and implications for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132784

Walker K, Wan F (2012) The harm of symbolic actions and green-washing: corporate actions and communications on environmental performance and their financial implications. J. Bus. Ethics 109(2):227–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1122-4

Wang W, Tian Z, Xi W, Tan YR, Deng Y (2021) The influencing factors of China’s green building development: an analysis using RBF-WINGS method. Building and Environment 188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107425

Wang Y, Zhi Q (2016) The role of green finance in environmental protection: two aspect of market mechanism and policies. Energy Procedia 104:311–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2016.12.053

Wu Y (2022) Are green bonds priced lower than their conventional peers? Emerging Markets Review 52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2022.100909

Xu X, Xie Y, Obobisa ES, Sun H (2023) Has the establishment of green finance reform and innovation pilot zones improved air quality? Evidence from China. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01773-0

Yeow KE, Ng S (2021) The impact of green bonds on corporate environmental and financial performance. Manag. Financ. 47(10):1486–1510. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-09-2020-0481

Yin X, Xu Z (2022) An empirical analysis of the coupling and coordinative development of China’s green finance and economic growth. Resour. Policy 75:102476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102476

Zerbib OD (2019) The effect of pro-environmental preferences on bond prices: evidence from green bonds. J. Bank. Financ. 98:39–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2018.10.012

Zeng YT, Wang F, Wu J (2022) The impact of green finance on urban haze pollution in China: a technological innovation perspective. Energies 15(3):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15030801

Zhang D (2021) Green credit regulation, induced R & D and green productivity: Revisiting the Porter Hypothesis. International Review of Financial Analysis 75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101723

Zhou XG, Tang XM, Zhang R (2020) Impact of green finance on economic development and environmental quality: a study based on provincial panel data from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27(16):19915–19932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-08383-2

Zuo J, Zillante G, Wilson L, Davidson K, Pullen S (2012) Sustainability policy of construction contractors: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16(6):3910–3916

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, D., Kythreotis, A. Why issue green bonds? Examining their dual impact on environmental protection and economic benefits. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1761 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04318-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04318-1