Abstract

The management of construction and demolition waste (CDW) is emerging as a significant global challenge. Traditional methods such as direct landfill and incineration fail to handle the vast amount of CDW properly, resulting in serious social and environmental issues. In this context, the construction industry has increasingly recognized the importance of CDW recycling and recovery. Consequently, construction industry leaders are advocating for development of reverse logistics networks for multiple types of CDW by solving a multi-objective mixed-integer linear programming model, which aims to restore waste for new structures toward circular economy. This model reduces landfill waste and maximizes the value of CDW, while minimizing total cost and negative environmental impact by integrating with the government under uncertainties to encourage sustainable management of CDW. A real-world case study from Hong Kong is conducted to examine and validate the practicability of the proposed model. Experimental results show that transportation activities have a significant impact on the reverse logistics network design since they are costly and generate the largest share of carbon emissions. In addition, a regulatory mechanism, i.e., setting carbon emission caps, proves effective in balancing facility workload and improving the utilization of underutilized facilities. The results also indicate that the proposed reverse logistics network is capable of adapting to costly transportation scenarios by prioritizing facilities with higher operational costs but lower transportation expenses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Construction and demolition waste (CDW) accounts for 40% of all waste generated worldwide (United Nations Environment Programme 2012). It includes a wide variety of materials, such as concrete, bricks, sub-soil, rebar, wood, glass, metals and plastic (Wu et al. 2017), arising from construction and demolition of buildings and infrastructure, as well as refurbishment, renovation and maintenance. As inevitable by-products of construction activities, CDW treatment has become a challenging issue for many countries, due to rapid industrialization and urbanization. Direct landfill and incineration, the most common approaches to CDW disposal, have been widely adopted since they are convenient and easy to implement. However, landfill spaces used for CDW are being consumed at a startling rate, while incineration produces carbon emissions and might release toxic fumes. The improper handling and disposal of CDW, particularly hazardous materials, can cause adverse effects on the environment and society, such as increased land-use requirement for landfills, resource depletion and ecosystem degradation (Xin and Wan 2023; Nawaz et al. 2023a).

As the circular economy gains widespread acceptance, numerous policies and initiatives have been devised to stimulate the adoption of sustainable methods (Chu et al. 2024), for example, the Roadmap to a Resource Efficient Europe and Circular Economy Action Plan in European Union (Nußholz et al. 2019), Bulk Solid Waste Comprehensive Utilization Plan in China (Huang et al. 2018), and Construction Waste Disposal Charging Scheme in Hong Kong SAR of China (Yu et al. 2013). The purpose of these initiatives is to decrease CDW generation, uplift its reuse and recycling, and ultimately realize a circular economy of CDW. The environmental and economic benefits of CDW recycling markets have been quantified theoretically using an analytical model (Besklubova et al. 2023). Motivated by these policies and benefits, the construction industry with social responsibility has embarked on designing reverse logistics networks for sustainable construction toward a circular economy (AECOM 2019). In addition to the administrative countermeasures, technological advancements herald sustainable approaches to CDW disposal aligned with the principles of the circular economy.

Reverse logistics is the process of planning, implementing and controlling backward flows of used products and materials from their end-users to recovery or proper disposal points (Alumur et al. 2012). However, reverse logistics network design for CDW is a more complicated problem compared with other types of waste, such as waste electrical and electronic equipment. The main hurdles can be summarized as the “three more problems”: more multifaceted processes, more decision-makers and more uncertainties. First, more multifaceted processes are involved in CDW treatment, resulting in a more complex multi-echelon topology. These processes are performed in existing facilities that are shared to dispose of other municipal waste. Thus, additional constraints need to be considered. Second, more decision-makers (e.g., regulators and facility managers) engage in its reverse logistics network design, instead of one decision-maker. Diversified, conflicting objectives must be balanced for efficient collaboration to maximize economic, environmental and social benefits (Nawaz et al. 2023b). Third, more uncertainties are closely associated with the reverse logistics network of CDW, such as the daily CDW generation amount at generation points. The reverse logistics network of CDW could lose its optimality or feasibility due to these uncertainties. Consequently, it is imperative to design a cost-effective and efficient reverse logistics network for CDW treatment.

Motivated by the industrial practices of recycling and reusing CDW, three pertinent research questions explored in this paper are as follows: (i) How can a theoretical framework be designed for stakeholders and regulators to establish reverse logistics networks when considering the “three more problems”? (ii) What model can be formulated to optimize the reverse logistics networks under uncertainties when multiple objectives are incorporated? (iii) What are the key factors affecting reverse logistics network performance, and what operational strategies can be adopted to adapt future practices of CDW recycling and reuse?

To address the above research questions, this paper proposes a multi-objective mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) model to design a multi-echelon reverse logistics network for CDW considering the “three more problems”. To answer the first question, a real-life CDW recycling practice in Hong Kong is studied to identify key stakeholders, echelons, factors and uncertainties in a reverse logistics network. A modeling framework is presented to enhance collaboration between practitioners and regulators for CDW recycling. The second question is answered by formulating a MILP model based on economic, environmental and efficiency principles to minimize the total cost and total carbon emission under uncertainties (Nawaz et al. 2022; Avotra and Nawaz 2023). More specifically, an ε-constraint method is employed to transform multiple and conflicting objectives into constraints, thereby formulating single-objective subproblems. The upper bounds of the constraints, provided by the ε-vector, help generate the Pareto frontier for optimal solutions (Bérubé et al. 2009). The fuzzy random variable technique is adopted to measure uncertainties in the proposed model due to the absence of credible and accurate data. This technique has been commonly used to estimate parameters such as demands and distances in various problems, such as the oil refinery waste management problem (Zhumadillayeva et al. 2020), the post-disaster relief distribution problem (Cao et al. 2021) and the maximal covering location problem (Aider et al. 2023). To the third question, a real-life case study from Hong Kong is introduced to validate the proposed model. Sensitivity analysis is also conducted to analyze the impact of key parameters on reverse logistics network design. According to findings and observations, some useful managerial implications are summarized for stakeholders to manage the reverse logistics network and realize a circular economy in the Hong Kong construction industry.

This research makes theoretical and practical contributions as follows. To the best of our knowledge, this research is among the first to design reverse logistics networks for multi-CDW recycling under uncertainties, considering the economic, environmental and efficiency principles. These principles are incorporated into a generic framework to facilitate collaboration with multiple stakeholders for reverse logistics network design. Second, the proposed model considers the off-site sorting strategy which is often adopted in practice but rarely studied theoretically by optimization models. This formulation contributes to the CDW reverse logistics network modeling and makes the model formulation consistent with industrial practices. Third, based on key findings and observations of the case study, several managerial insights are identified for regulators to develop CDW recycling policies and for operators to improve and manage the CDW reverse logistics network. The Hong Kong case study serves as an exemplary case for other regions that face similar challenges in sustainable construction and CDW recycling initiatives toward a circular economy (Li and Du 2015; Soto-Paz et al. 2023).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Literature review” reviews the literature on reverse logistics network design and reverse logistics in construction. Section “Problem description” gives a problem description. Section “Modeling” formulates a model for the reverse logistics network design problem. Section “Case study” verifies the proposed model through a Hong Kong case study. Section “Discussion” discusses the key findings and observations. Section “Conclusions” shows the conclusions and future research directions.

Literature review

This paper is closely related to three streams of literature. The first relevant steam is reverse logistics network design, which has been extensively studied over the past decades. Srivastava (2008) develops a conceptual model for designing a reverse logistics network consisting of collection centers and two types of rework facilities established by an original equipment manufacturer for typical electronic devices, such as televisions, washing machines and personal computers. Alshamsi and Diabat (2015) formulate an MILP model to design reverse logistics networks by selecting optimal sites and determining the capacities of inspection centers and manufacturing facilities. Their work specifically examines the impact of providing in-house fleets and outsourcing options on reverse logistics. Govindan and Bouzon (2018) analyze the key drivers and barriers of reverse logistics through a systematic literature review, and suggest multiple perspectives (including company, society, government and customer) should be considered while addressing the reverse logistics network design problem. Prajapati et al. (2019) provide a literature review on reverse logistics, highlighting that existing research primarily focuses on the manufacturing, automobile and electronics industries. More recently, due to the outbreak of COVID-19, reverse logistics network design for medical waste management has garnered increased attention (Kargar et al. 2020). For example, Richter et al. (2021) propose an iterative tessellation-based analytical approach for efficient and practical waste management region design at the tactical level. The importance of reverse logistics is being discovered by not only in traditional industries but also across various other sectors.

The second stream focuses on technological advancements in CDW recycling and reuse. Recently, technologies for the separation and recovery of CDW have been innovated and developed, making them readily accessible and generally affordable. Davis et al. (2021) design a deep convolution neural network-based approach for classifying typical CDW using digital images for collection, sorting and recycling. Krishnan et al. (2021) present current technologies for recovering metals from waste and declare that some of them are proven and successful processes for large-scale implementation. Moreover, Guerra et al. (2020) adopt building information modeling (BIM) to enhance CDW planning with temporal-based algorithms at the project level. While all technologies have been developed, they remain limited to specific, isolated echelons, such as CDW generation points and recycling facilities. To enable more effective utilization of these technologies, reverse logistics network design is necessary to bridge these isolated echelons.

The third stream is reverse logistics in construction. Hu and Sheu (2013) highlight the importance of reverse logistics for managing post-disaster debris, and develop a multi-objective LP model to minimize reverse logistics costs, as well as environmental and operational risks. They show that their model reduces risk-induced and psychological costs compared with those models solely optimizing logistics costs. Considering the uncertainties in post-disaster debris quantities across different locations, Aydin (2020) proposes a stochastic MILP model to design reverse logistics networks for end-of-life-buildings’ debris in the Turkey context. In addition, siginificant efforts have been directed toward reverse logistics network design for CDW. Fu et al. (2017) design a multi-objective location model incorporating government subsidies and solve it using an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm. Their results show government subsidies have a substantial impact on reverse logistics network design. Rahimi and Ghezavati (2018) employ a risk-averse two-stage SP to develop a reverse logistics network under an uncertain demand and rate on investment, with particular consideration of on- and off-site separation. Xu et al. (2019) present a dynamic MILP model to select disposal processes, determine waste disposal volumes and control total costs under the government’s green tax regulation over multiple time periods. Shi et al. (2019) propose a multi-objective location model to optimize the construction waste recycling and disposal plants, aiming to minimize costs and reduce negative environmental effects. Likewise, Pan et al. (2020) formulate a multi-period, multi-objective MILP model for CDW treatment plant location planning and capacity expansion planning. Their model addresss the objective conflicts among different stakeholders, such as contractors and recycling firms. Shi et al. (2020) investigate reverse logistics network design of CDW under two carbon policies—carbon price and carbon trading—based on a real case study from China. Their findings reveal that the carbon price policy improves the CDW recycling ratio and reduces carbon emissions, while the carbon trading policy incentivizes even higher recycling rates and lower carbon emissions (Kang and Tan 2023). Yang and Chen (2020) employ robust optimization to improve the robustness of a reverse logistics network for CDW against uncertain situations. Ahmed and Zhang (2021) develop a MILP model to minimize both facility-based and non-facility-based costs for reverse logistics network design. Table 1 summarizes the model and solution details.

From the literature review, an in-depth analysis is performed to identify research gaps. First, reverse logistics has primarily been studied in traditional industries. Although its importance is intuitively evident, there is limited literature addressing its application in other sectors such as the construction industry. Second, many deterministic models are currently formulated to design reverse logistics networks in previous studies without considering uncertainties. Ignoring uncertainties affects the quality and feasibility of these models, often resulting in suboptimal or even infeasible solutions. Third, environmental effects are rarely incorporated into these models, despite the fact that the primary goal of reverse logistics is environmental protection. Most existing models are developed from an economic perspective, overlooking their environmental implications. To fill these research gaps, this research investigates the operations of CDW recycling practices in Hong Kong, proposes a multi-objective MILP model to minimize total costs and carbon emissions for multi-CDW recycling in a single period under uncertainties, and analyzes the impact of policy control parameters on reverse logistics network design for CDW management.

Problem description

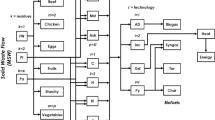

This paper designs a multi-echelon reverse logistics network for CDW through a four-layer framework as shown in Fig. 1. Four types of decision-makers follow three principles to minimize total costs and negative environmental impacts under uncertainties while designing the reverse logistics network.

They collaborate to develop an optimal reverse logistics network for CDW recycling. Regulators enact relevant standards and regulations to control and supervise the operations of CDW treatment. For example, they can implement green taxes and government subsidies to encourage recycling CDW. Project managers are responsible for managing demolition work and CDW disposal at generation points where waste is generated. Facility managers operate facilities and control their capacities for CDW disposal. Transportation companies as third logistics service providers transport CDW among these facilities according to recycling plans.

Three principles are followed by decision-makers when designing a reverse logistics network. The economic principle directs these decision-makers to maximize overall benefits and minimize costs of this reverse logistics network and balances trade-offs between these benefits and costs of stakeholders. The environmental principle safeguards the environment by minimizing the detrimental effects of activities, such as carbon emissions associated with transportation. The efficiency principle ensures that the reverse logistics network is designed to maximize benefits while minimizing costs, preventing misused resources, particularly in face of uncertainties.

Based on the principles, objectives can be summarized for model formulation as follows. Total costs are minimized while satisfying specific constraints. Meanwhile, negative environmental impacts are also minimized for environmental protection. The proposed reverse logistics network is capable of dealing with uncertainties to maintain both its efficiency and effectiveness.

The reverse logistics network is structured as a multi-echelon topology, with each echelon represented by generation points or a type of facilities. These facilities can be categorized into four types: sorting facilities where CDW (including inert and non-inert CDW) is sorted; public fill reception facilities which serves as temporary storage prior to further treatment and reuse in reclamation and site formation projects; recycling facilities where waste is recycled and used; and landfill sites where the leftover is ultimately disposed of. CDW is transported from upstream to a downstream echelons within this network.

Modeling

Model formulation

A multi-objective MILP model is formulated to solve the reverse logistics network design problem considering uncertainties. This network is composed of \(G\) generation points, \(S\) sorting facilities, \(P\) public fill reception facilities, \(R\) recycling facilities, \(L\) landfill sites with \(K\) CDWs. This model minimizes two objectives, namely total costs and carbon emissions, while employing fuzzy numbers to deal with uncertainties. Some assumptions are made to facilitate the model formulation. The following assumptions are essential for simplifying the complex problem of reverse logistics network design, making it more manageable and applicable. The single-period approach reduces model complexity, while some capacity constraints reflect real-world operational limits. By incorporating uncertainties, this model accounts for variability and enhances decision-making resilience. Simplifying the loss of CDW and assuming full market consumption of recycled materials helps in focusing on core optimization objectives without additional complications.

Assumption 1. The reverse logistics network design is a single-period decision problem. This indicates the decision process is reset at the beginning of the next disposal period (Shi et al. 2020). This assumption reduces the computational complexity of a multi-period analysis. It is also reasonable in scenarios where each disposal period involves distinct decisions based on updated conditions.

Assumption 2. Each facility has a minimum and maximum capacity for processing CDW to satisfy the economic principle (Xu et al. 2017). Real-world facilities operate with physical and economic limits. Imposing capacity constraints ensures that this model aligns with practical operational limits and economic principles.

Assumption 3. Unit transportation cost, daily generation of CDW and daily consumption of CDW for reclamation and site formation are assumed to be uncertain, due to influences of gasoline prices, demolition progresses and market demands (Rahimi and Ghezavati 2018, Xu et al. 2019). Uncertainties in key parameters are an inherent aspect of real-world reverse logistics operations. By modeling these uncertainties, this model enhances its applicability and robustness in decision-making under variable conditions.

Assumption 4. There is no loss of CDW during transportation and treatment of CDW (Pochampally et al. 2008). This assumption simplifies the model by focusing on core issues of cost and emission minimization. Losses are typically low or manageable in modern logistics operations, as shown in related studies.

Assumption 5. All recycled CDW in recycling facilities can be consumed by the market. It can be observed that digital marketplaces, such as Materials Marketplace (materialsmarket.com) in USA, Travis Perkins (travisperkins.co.uk) in UK and Yunzhu (yzw.cn) in China, have been established to trade recycled CDW. Authors also interviewed industrial collaborators (a digital platform and a construction company) and found that as encouraged by policies and incentives, an increasing proportion of recycled CDW is being consumed by the market. Similar details can also be found in Ding et al. (2023).

Indices, sets, parameters and decision variables

Indices and sets:

\(g\in G\): generation point where \(G\) is a set of generation points,

\(s\in S\): sorting facility where \(S\) is a set of sorting facilities,

\(p\in P\): public fill reception facility where \(P\) is a set of public fill reception facilities,

\(r\in R\): recycling facility where \(R\) is a set of recycling facilities,

\(l\in L\): landfill site where \(L\) is a set of landfill sites,

\(k\in K\): CDW where \(K\) is a set of CDWs.

Parameters:

\({{FC}}_{s}\): fixed cost for opening sorting facility \(s\),

\({{FC}}_{p}\): fixed cost for opening public fill reception facility \(p\),

\({{FC}}_{r}\): fixed cost for opening recycling facility \(r\),

\({{FC}}_{l}\): fixed cost for landfill site \(l\),

\({D}_{{gs}}\): distance between generation point \(g\) and sorting facility \({s}\),

\({D}_{{sp}}\): distance between sorting facility \({s}\) and public fill reception facility \(p\),

\({D}_{{sl}}\): distance between sorting facility \({s}\) and landfill site \({l}\),

\({D}_{{pr}}\): distance between public fill reception facility \(p\) and recycling facility \({r}\),

\({D}_{{rl}}\): distance between recycling facility \({r}\) and landfill site \({l}\),

\({{OC}}_{{sk}}\): unit operational cost of sorting facility \(s\) for sorting CDW \(k\),

\({{OC}}_{{pk}}\): unit operational cost of public fill reception facility \(p\) for storing CDW \(k\),

\({{OC}}_{{rk}}\): unit operational cost of recycling facility \(r\) for remanufacturing CDW \(k\),

\({{OC}}_{{lk}}\): unit operational cost of landfill site \(l\) for disposal of leftover of CDW \(k\),

\({E}_{k}\): unit carbon emission per unit distance for transporting a unit of CDW \(k\),

\({E}_{{sk}}\): unit carbon emission of sorting facility \(s\) for sorting CDW \(k\),

\({E}_{{pk}}\): unit carbon emission of public fill reception facility \(p\) for storing CDW \(k\),

\({E}_{{rk}}\): unit carbon emission of recycling facility \(r\) for remanufacturing CDW \(k\),

\({E}_{{lk}}\): unit carbon emission of landfill site \(l\) for disposal of leftover of CDW \(k\),

\({\underline{C}}_{{sk}}\): minimum processing capacity of sorting facility \(s\) for CDW \(k\),

\({\bar{C}}_{{sk}}\): maximum processing capacity of sorting facility \(s\) for CDW \(k\),

\({\underline{C}}_{{pk}}\): minimum processing capacity of public fill reception facility \(p\) for CDW \(k\),

\({\overline{C}}_{{pk}}\): maximum processing capacity of public fill reception facility \(p\) for CDW \(k\),

\({\underline{C}}_{{rk}}\): minimum processing capacity of recycling facility \(r\) for CDW \(k\),

\({\overline{C}}_{{rk}}\): maximum processing capacity of recycling facility \(r\) for CDW \(k\),

\({\underline{C}}_{{lk}}\): minimum processing capacity of landfill site \({l}\) for CDW \(k\),

\({\overline{C}}_{{lk}}\): maximum processing capacity of landfill site \({l}\) for CDW \(k\),

\({\theta }_{{gk}}\): collection ratio of CDW \(k\) at generation point \(g\),

\({\mu }_{{sk}}\): recyclable ratio of CDW \(k\) at sorting facility \(s\),

\({\varphi }_{{rk}}\): remanufacturing ratio of CDW at recycling facility \(r\).

Uncertain parameters:

\({\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}\): unit transportation cost per unit distance for transporting a unit of CDW \(k\), which is measured by a triangle fuzzy number, and \({\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}=\left({\underline{TC}}_{k},{{TC}}_{k},{\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}\right)\),

\({\widetilde{Q}}_{{gk}}\): quantity of CDW \(k\) generated at generation point \(g\), which is measured by a triangle fuzzy number, and \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{gk}}=\left({\underline{Q}}_{{gk}},{Q}_{{gk}},{\bar{Q}}_{{gk}}\right)\),

\({\widetilde{Q}}_{{pk}}\): quantity of CDW \(k\) used for reclamation and site formation at public fill reception facility \(p\), which is measured by a triangle fuzzy number, and \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{pk}}=\left({\underline{Q}}_{{pk}},{Q}_{{pk}},{\overline{Q}}_{{pk}}\right)\).

Policy control parameters:

\(T\): unit green tax on landfills,

\({{GS}}_{k}\): unit government subsidy for producing recycled materials from CDW \(k\),

\({Cap}\): limit of carbon emissions in a reverse logistics network.

Decision variables:

\({Q}_{{gsk}}\): quantity of CDW \(k\) transported from generation point \(g\) to sorting facility \({s}\),

\({Q}_{{spk}}\): quantity of CDW \(k\) transported from sorting facility \({s}\) to public fill reception facility \(p\),

\({Q}_{{slk}}\): quantity of the leftover CDW \(k\) transported from sorting facility \({s}\) to landfill site \({l}\),

\({Q}_{{prk}}\): quantity of CDW \(k\) transported from public fill reception facility \(p\) to recycling facility \({r}\),

\({Q}_{{rlk}}\): quantity of the leftover CDW \(k\) transported from recycling facility \({r}\) to landfill site \({l}\).

Objective functions

In this model, total costs include five parts. The first is fixed costs (\({FC}\)) of opening facilities. The second is transportation costs (\({TC}\)) of shipping CDW between different facilities. The third is operational costs (\({OC}\)) of the facilities. The fourth is green taxes (\({GT}\)) which is a tool of regulators to motivate project managers to recycle CDW. The fifth is government subsidies (\({GS}\)) that are an incentive mechanism to encourage recycling CDW. They are presented as follows.

Thus, total costs are minimized as follows.

Total carbon emissions are derived from CDW transportation (\({TE}\)) and treatment (\({OE}\)).

Then, total carbon emissions are minimized as follows.

Constraints

Constraint (10) states \({\theta }_{{gk}}\) percent of the daily generation of CDW is collected and transported to sorting facilities. \({\theta }_{{gk}}\) is an exogenous variable, determined by the techniques and willingness of project managers. The larger \({\theta }_{{gk}}\) is, the greater the amount of CDW can be collected.

Constraints (11) and (12) are material balance constraints in recycling facilities, and indicate \({\mu }_{{sk}}\) percent of CDW can be sorted as recyclable materials and the rest is sent to landfill sites directly.

Constraint (13) presents a part of CDW in public fill reception facilities is used for reclamation and site formation, while the rest is shipped to recycling facilities for recycling and remanufacturing.

Constraint (14) shows \({\varphi }_{{rk}}\) percent of CDW is remanufactured, and the rest cannot be recycled and then is sent to landfill sites.

Constraints (15)–(18) are capacity constraints in each facility. The daily processing quantity in each facility is required to be greater than its minimum capacity and less than its maximum capacity. These constraints limit not only the maximum but also the minimum capacity of a facility. The reason for limiting the minimum capacity is that total costs would increase unreasonably due to this fixed cost, if only a small fraction of capacity is utilized.

Constraint (19) ensures \({x}_{s}\), \({x}_{p}\), \({x}_{r}\), and \({x}_{l}\) are binary variables.

Constraint (20) ensures CDW is transported from upstream to downstream facilities.

Model transformation

The proposed model is a multi-objective MILP model that minimizes both total costs and carbon emissions of a reverse logistics network. Since this model contains multiple objectives, an ε-constraint method is used (He and Zhang 2022) to convert it into a single objective MILP model so as to design an optimal reverse logistics network for CDW management. Thus, objective (9) is converted into constraint (21), where \({Cap}\) limits the maximum carbon emissions permitted by regulators.

In addition, the model formulated in Section “Model formulation” includes three uncertain parameters. These uncertainties exist in fuzzy parameters of the unit transportation cost (\({\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}\)), daily recycled CDW in a generation point (\({\widetilde{Q}}_{{gk}}\)), and daily consumed CDW for reclamation and site formation in a public fill reception facility (\({\widetilde{Q}}_{{pk}}\)). They are shown in objective (2), and constraints (10) and (13) respectively. Following Zhong et al. (2015), Cao et al. (2021) and Zhan et al. (2023), triangle fuzzy numbers are employed to measure these uncertainties of \({\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}\), \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{gk}}\) and \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{pk}}\).

Let \(\widetilde{{\mathbb{N}}}\) denote a triangle fuzzy number and abstractly represent \({\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}\), \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{gk}}\) and \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{pk}}\) from the proposed model. A triangle fuzzy number can be described by \(\underline{\mathbb{N}}\), \({\mathbb{N}}\) and \(\overline{{\mathbb{N}}}\) that are the minimum value, the value with maximum possibility and the maximum value of this triangle fuzzy number, namely \(\widetilde{{\mathbb{N}}}=\left(\underline{\mathbb{N}}{\mathbb{,}}{\mathbb{N}}{\mathbb{,}}\overline{{\mathbb{N}}}\right)\). Thus, triangle fuzzy numbers of \({\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}\), \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{gk}}\) and \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{pk}}\) can be expressed by \({\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}=\left({\underline{TC}}_{k},{{TC}}_{k},{\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}\right)\), \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{gk}}=\left({\underline{Q}}_{{gk}},{Q}_{{gk}},{\bar{Q}}_{{gk}}\right)\) and \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{pk}}=\left({\underline{Q}}_{{pk}},{Q}_{{pk}},{\bar{Q}}_{{pk}}\right)\) respectively. Following the definition, \({\underline{TC}}_{k}\), \({\underline{Q}}_{{gk}}\) and \({\underline{Q}}_{{pk}}\) are the minimum value of their fuzzy parameters; \({{TC}}_{k}\), \({Q}_{{gk}}\) and \({Q}_{{pk}}\) are the value with maximum possibility; and \({\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}\), \({\bar{Q}}_{{gk}}\) and \({\bar{Q}}_{{pk}}\) are the maximum value. For \(\widetilde{{\mathbb{N}}}\), its membership function \(f\left(\chi \right)\) can be formulated as follows:

According to Jiménez et al. (2007), the expected value of a triangle fuzzy number is formulated as \({\mathbb{E}}[\widetilde{{{{\mathbb{N}}}}}]=\frac{(\underline{{{{\mathbb{N}}}}}+2{{{\mathbb{N}}}}+\overline{{{{\mathbb{N}}}}})}{4}\) based on its membership function \(f\left(\chi \right)\), where \({\mathbb{E}}\left[\cdot \right]\) is an expectation operator. With this technique, \({\widetilde{TC}}_{k}\), \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{gk}}\) and \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{pk}}\) can be converted and expressed as their expected values, i.e., \({\mathbb{E}}[{\widetilde{TC}}_{k}]=\frac{({\underline{TC}}_{k}+2T{C}_{k}+{\overline{TC}}_{k})}{4}\), \({\mathbb{E}}[{\tilde{Q}}_{gk}]=\frac{({\underline{Q}}_{gk}+2{Q}_{gk}+{\overline{Q}}_{gk})}{4}\) and \({\mathbb{E}}[{\tilde{Q}}_{pk}]=\frac{({\underline{Q}}_{pk}+2{Q}_{pk}+{\overline{Q}}_{pk})}{4}\). Replacing \({\widetilde{TC}}_{k}\), \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{gk}}\) and \({\widetilde{Q}}_{{pk}}\) by \({\mathbb{E}}[{\widetilde{TC}}_{k}]\), \({\mathbb{E}}[{\tilde{Q}}_{gk}]\) and \({\mathbb{E}}[{\tilde{Q}}_{pk}]\) in objective (2), constraints (10) and (13), objective (22), constraints (23) and (24) can be formulated as follows:

Therefore, objective (22) calculates transportation costs of transporting CDW among different facilities with \({\mathbb{E}}\left[{\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}\right]\). Constraint (23) computes a CDW flow balance between CDW generation points and sorting facilities with \({\mathbb{E}}\left[{\widetilde{Q}}_{{gk}}\right]\), while constraint (24) indicates that the amount of CDW consumed by public fill reception facilities and recycling facilities equals the amount received by sorting facilities with \({\mathbb{E}}\left[{\widetilde{Q}}_{{pk}}\right]\). Replacing objective (2) in Eq. (6) by objective (22), total costs \({Z}_{1}\) can be formulated as

where \({FC}\) is fixed costs of opening facilities, \({TC}^{\prime}\) is transportation costs of shipping CDW between different facilities, \({OC}\) is variable costs for processing CDW, \({GT}\) is green taxes, \({GS}\) is government subsidies. In addition, since constraints (10) and (13) are transformed into constraints (23) and (24) with converting objective (9) into constraint (21), the proposed model includes constraints \((1),\,(3)-(5),\,(7),\,(8),\,(11),\,(12),\text{and}(14)-(24)\).

Case study

Parameter setting

A real-life case from Hong Kong is used to validate the applicability and practicability of the proposed model. Hong Kong represents a highly urbanized, densely populated area with significant CDW generation (Kang et al. 2022a) and has well-developed infrastructure, strict environmental regulations, and ongoing sustainability initiatives, which makes it an ideal testing ground for model validation. Specifically, Hong Kong’s policies and incentives for recycling CDW and reducing carbon emissions provide a relevant backdrop for validating this model that minimizes both costs and emissions (Yu et al. 2013). Hong Kong case is not an isolated example, but rather a representative case of urban regions with similar challenges, such as high construction activities, limited landfills, and a growing need for sustainable waste management solutions. This case study has broader relevance for other highly urbanized areas with analogous constraints and market dynamics. Although this case study is focused on Hong Kong, this model is designed with flexibility, allowing for its application to other regions facing comparable reverse logistics challenges. Some parameters used in this model, such as transportation costs, CDW generation rates, and market demands for recycled materials, are adjustable, enabling adaptation to different local conditions. Other densely populated regions with the same CDW recycling processes can apply this model with minor parameter adjustments in line with their price level to reflect local market dynamics and transportation infrastructures.

Hong Kong SAR of China, including 18 districts, is a metropolitan city with over 7.4 million residents in a 1,104 square kilometer territory (CSDHK 2022), and is one of the most densely populated places globally. Due to rapid urbanization, the quantity of CDW generation increases each year. This figure was 20.72 million tons, representing an increase of about 17% as compared with the 2019 level (EPDHK, 2020). The data is mainly collected from Waste Data & Statistics of Hong Kong (EPDHK 2009–2020), Kang et al. (2022a), and Ahmed and Zhang (2021). The data for model validation is tabulated in Supplementary Tables A.1–A.7 in Appendix. Supplementary Table A.1 shows available facilities in Hong Kong for CDW recycling. There are 17 waste generation points, 2 sorting facilities, 4 public fill reception facilities, 2 recyclers and 3 landfill sites. Their locations are depicted in Supplementary Fig. A.1. Supplementary Table A.1 presents some general parameters and policy control parameters for optimization. Supplementary Tables A.3–A.7 give the data on each facility, including the quantity of CDW, the distance between upstream to downstream echelons, fixed open costs, operational costs, carbon emissions and capacity limits. For the purpose of discussion, two types of CDW (i.e., inert CDW and noninert CDW) are considered in this case study. According to Xu et al. (2019), CDW I refers to inert CDW and could be concrete, mortar and brickwork, while CDW II is noninert CDW, such as steel, timber and sludge.

Experiments of this case study are conducted on a machine running Windows 10 Enterprise 64-bit, Dell OptiPlex 7060 with Intel® Core™ i7-8700 CPU, 3.2 GHz and 16 GB of RAM. The programming of the proposed model is completed by Python and IBM ILOG CPLEX optimizer.

Results

The optimal solutions and reverse logistics networks for CDW I and II are demonstrated with key performance indicators (KPIs) in Fig. 2. Under this parameter setting, all facilities open for CDW recycling, due to the capacity limits. According to arrows in networks, CDW from an upstream facility is transported to the closest downstream facilities for further processing. This reverse logistics network for CDW I is almost the same as that for CDW II. All CDW I generated in each district can be consumed completely by its nearest downstream sorting facility. However, CDW II generated at Yau Tsim Mong cannot be completely processed by Tuen Mun Area 38 sorting facility, requiring part of CDW II to be sorted at Tseung Kwan O Area 137 sorting facility. In addition, after CDW II sorting at Tuen Mun Area 38 sorting facility, the non-recyclable waste is shipped to not only SENT but also NENT landfill sites. This increases transportation costs and generates extra carbon emissions due to capacity limits.

KPIs studied include cost breakdowns, carbon emissions, and utilization of facilities. Overall costs are HK$ 2,094,495, including transportation costs of HK$ 1,261,483, fixed costs of HK$ 45,452, operational costs of HK$ 660,414, and green taxes of HK$ 127,144. Considering government subsidies of HK$ 907,710, total costs are decreased to HK$ 1,186,785. It is observed that the transportation and operational costs account for approximately 91.7% of overall costs. However, transportation costs are the highest among all costs, and are almost twice as high as operational costs which are the second-highest. That is, transportation significantly influences reverse logistics network design under this parameter setting. For emission analysis, total carbon emissions are 7972 kg, including emissions of 7187 kg from transportation and 785 kg from processing CDW. Similarly, transportation emissions account for around 90.1% of the total carbon emissions and are about nine times as more as operational carbon emissions.

The utilization of each facility for each type of CDW is further analyzed. It is observed that facility utilization varies considerably. For CDW I recycling, the utilization of Tseung Kwan O Area 137 public fill reception facility, SENT and NENT landfill sites reaches 100%. For CDW II, the utilization of Tapbo, and SENT and NENT landfill sites reaches 100%. These figures imply that these facilities are bottlenecks whose capacity limits could reduce the performance of these two reverse logistics networks. Especially when more CDW is generated, these facilities might fail to process the waste. There are several facilities whose utilization approaches around 90%, including Mui Wo for CDW I, and Tseung Kwan O Area 137 sorting and public fill reception facilities for CDW II. These figures mean that these facilities efficiently operate and can handle CDW generation uncertainties. The utilization of the majority of facilities ranges from 40 to 70%. However, several facilities underutilize their capacities, including Tuen Mun Area 38 public fill reception facility for CDW I, and Mui Wo public fill reception facility and Tailor for CDW II. Improving their utilization can cope with the capacity shortage of others and further improve performance of the whole reverse logistics network.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis is a technique used to evaluate how variations in input parameters affect model outcomes (Borgonovo and Plischke 2016). It investigates the impact of changes in parameters such as unit transportation costs and CDW generation on various costs and carbon emissions within the reverse logistics network. In this case study, sensitivity analysis is conducted by varying the unit transportation cost across three CDW generation scenarios, as well as considering carbon emission caps and maximum processing capacity limits.

Figure 3 presents the impact of unit transportation cost with \({\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}\) = 5.25, 7.25 and 9.25. Three scenarios are considered, i.e., a decrease of 20% in current levels of CDW generation (scenario I), current generation of CDW (scenario II) and an increase of 20% in the current generation (scenario III). The cost analysis shows that the impact of unit transportation cost is slight on fixed costs, operational costs, green taxes and green subsidies, apart from total costs and transportation costs. The transportation costs are directly influenced by unit transportation cost. When \({\widetilde{{TC}}}_{k}\) = 5.25, 7.25 and 9.25, the transportation costs are HK$ 575,774, HK$ 795,393 and HK$ 1,014,811 respectively in scenario I; are HK$ 715,976, HK$ 988,730, and HK$ 1,261,483 respectively in scenario II; and are HK$ 852,015, HK$ 1,176,593, and HK$ 1,501,170 respectively in scenario III. It is observed that the transportation costs increase linearly as unit transportation cost or amount of CDW increases. An increase in total costs is due to an increase in unit transportation cost. Similarly, carbon emissions are slightly affected by a change in unit transportation cost and remain steady in different scenarios.

The reasons for slight impacts on some KPIs are as follows. First, capacity limits are a major obstacle. In this experiment, maximum processing capacities of facilities are strictly limited, and total capacities of each echelon are nearly equal to the amount to be processed. Since processing capacities of some facilities have been fully utilized, it is difficult to further improve this network as unit transportation cost changes. Second, unit transportation cost and carbon emission dominate the reverse logistics network design optimization. In other words, compared to unit transportation cost and carbon emission, unit operational cost and carbon emission are relatively small, which hardly affects reverse logistics network design. Therefore, a change in unit transportation cost has a slight impact on some KPIs.

The radar charts in Fig. 3 show the utilization of facilities for CDW I and II recycling. It is observed that the utilization is unchanged given the same scenarios, when unit transportation cost equals HK$ 5.25 or 7.25. With this cost of HK$ 9.25, the utilization is still unchanged in scenario I, but the utilization varies significantly in scenario I for recycling CDW II and in scenarios II and III for recycling CDW II. This implies this reverse logistics network is almost unchanged when unit transportation cost varies from HK$ 5.25 to 7.25. As this cost continues growing, this reverse logistics network changes in some scenarios. This change is determined by trade-offs between unit operational cost and unit transportation cost. When unit transportation cost is sufficiently high, the optimization result would rather select a facility with a high operational cost than one with a low cost to avoid transportation costs. For example, a large amount of CDW II is transferred from Mui Wo to Tuen Mun Area 38 public fill reception facility when unit transportation cost increases from HK$ 7.25 to 9.25. It is also observed that under current parameter setting, the optimal reverse logistics network can be obtained and utilization can be further improved. However, utilization of some facilities approaches 100%. Some measures should be taken to balance facility workloads, such as reducing unit operational cost of some facilities (i.e., Mui Wo and Chai Wan public fill reception facilities).

Carbon emission limits are a useful policy control tool for regulators to optimize this reverse logistics network. Its impact is analyzed as shown in Fig. 4. According to cost analysis, fixed costs and green taxes remain steady as this limit increases, because all facilities open for CDW recycling and the leftovers sent to landfill sites are unchanged. Transportation costs are increasing, but total costs and operational costs are decreasing in carbon emission limits. After carbon emission limits reaches 7950 kg, these costs also remain steady. For emission analysis, operational emissions are unchanged, but transportation emissions and total emissions are increasing before carbon emission limits reach 7950 kg. Both KPIs show that this reverse logistics network is cost-effective when carbon emission limits of 7950 kg are allowed. Comparing transportation emissions with operational emissions, reducing unit transportation carbon emission is important, since transportation emissions account for approximately 85% of total emissions. This not only causes environmental pollution but also makes it difficult to further improve reverse logistics network performance.

In addition, utilization analysis presents that controlling carbon emission limits can balance facility workloads with similar functions. For CDW I, as carbon emission caps increase, it is obvious that utilization of WENT decreases from around 98 to 48%, while that of NENT increases from 33 to 100%. Utilization of others changes moderately. Similarly, for CDW II, utilization of NENT increases from 60 to 100% but that of WENT decreases from 80 to 40%. Regulators can adjust the reverse logistics network by controlling the carbon emission limit.

The maximum processing capacity limit affects reverse logistics network design, as highlighted in previous analysis. In these experiments, the impact of minimum capacity constraints on KPIs is also analyzed. Figure 5 depicts their impacts on costs and carbon emissions. The trend remains consistent whether or not minimum capacity constraints are incorporated into the model. It is observed that KPIs without minimum capacity constraints outperform those with the constraints. In terms of costs, the total costs decrease sharply when the capacity limits are increased by 50%, with only a marginal decrease as the capacity limit increases from 100 to 200%. The trend in operational costs mirrors that of total costs. However, transportation costs increase and reach a peak of HK$ 1,280,000 (with minimum capacity constraints) and HK$ 1,277,000 (without constraints), before steadily decreasing. Despite an increase in transportation costs, the total costs still drop, which is attributed to a dramatic decrease in the operational costs.

For carbon emissions, the trend in total emissions is similar to that of transportation emissions. Both increase to a peak and then decrease gradually as the maximum processing capacity limits increase. Operational emissions fall dramatically and then slightly. This indicates that transportation emissions play a critical role in reverse logistics network improvement. As the limits increase, this reverse logistics network sacrifices the transportation costs for lower operational costs first. Once the capacity limits of bottleneck facilities are sufficiently large, both transportation and operational costs can be minimized as the bottlenecks are eliminated.

Figure 6 demonstrates the impact of capacity limits on facility utilization when the limit remains unchanged, or increases by 50%, 100% or 200%. Overall, minimum capacity constraints have a more profound impact on CDW II than CDW I, since the utilization of nearly all facilities changes under the current parameter setting. For CDW I, only a few facilities experience slight changes in utilization. As maximum processing capacities increase, two facilities—Chai Wan public fill reception facility and WENT landfill site—are excluded from this reverse logistics network for processing CDW, leading to a decrease in fixed costs. It is also observed that the utilization would change slightly if there are no minimum capacity constraints. For CDW I, Tseung Kwan O Area 137 public fill reception facility and SENT landfill site are critical to this reverse logistics network, because their utilization remain more than 80% even if the maximum processing capacity has doubled. For CDW II, Tseung Kwan O Area 137 public fill reception facility, and NENT and SENT landfill sites are critical to this reverse logistics network. Among them, SENT landfill site is significant because of its high utilization (100% for CDW I and over 70% for CDW II), when the capacity limit is increased to three times the current level. The radar charts make it easy to identify bottleneck facilities and work out an improvement plan. For example, under the current situation, expanding the maximum processing capacity of Tseung Kwan O Area 137 and Mui Wo public fill reception facilities, long with WENT and SENT landfill sites, would enhance CDW I recycling efficiency.

Discussion

Key findings and observations

According to experimental results and sensitivity analysis, there are several key findings and observations.

Dominance of transportation costs and emissions in network design

The reverse logistics network is significantly affected by transportation costs and emissions which take up a substantial part of total costs and carbon footprint. This implies that the increased transportation costs, due to higher unit transportation costs, underline the importance of transportation route optimization at the execution stage and the adoption of eco-friendly transportation modes to mitigate both environmental impacts and financial expenditure.

Efficacy of carbon emission caps as a regulatory mechanism

Carbon emission caps emerge as an effective regulatory tool to optimize reverse logistics and supply chains. The incremental carbon emission caps can balance facility utilization and stabilize transportation costs as well as total costs. However, the transportation emissions represent more than 80% of the total carbon emissions. Critical attention should be paid to decreasing transportation emissions for improvement in reverse logistics network performance and sustainability.

Impact of capacity constraints on network efficiency

Facility capacity constraints noticeably affect the efficiency of reverse logistics. Maximum processing capacity limits and minimum capacity constraints profoundly affect cost and emission metrics. Particularly, increasing capacity limits sharply lower total and operational costs, despite an initial rise in transportation costs, which subsequently decline. To alleviate bottlenecks and optimize network operations, expanding capacities of strategically critical facilities is imperative.

Utilization patterns and facility balancing through emission controls

Facility utilization patterns are markedly influenced by variations in carbon emission limits and capacity constraints. Adjusting carbon emission limits proves effective in balancing workloads across facilities, thereby preventing over-utilization of specific sites.

Strategic trade-offs in reverse logistics network design

Designing this reverse logistics network involves strategic trade-offs between transportation and operational costs. The network’s adaptability is demonstrated by its tendency to prioritize facilities with higher operational costs but lower transportation expenses when transportation costs are elevated. This change underscores the importance of flexibility in network design to maintain cost-effectiveness while minimizing environmental impacts. The ability to adjust operational strategies in response to dynamically changing costs is crucial for sustainable operations in a reverse logistics network.

Managerial implications

Some observations from this case study can be summarized as useful managerial implications for stakeholders.

First, it is significant to reduce unit transportation carbon emission under the current setting. Compared to a facility unit operational emission, an exorbitant unit transportation carbon emission is an obstacle to improving reverse logistics network performance. Experimental results indicate that transportation generates the largest share of carbon emissions in this reverse logistics network. When the carbon emission objective is considered in the proposed model, this reverse logistics network changes slightly unless its unit transportation emission can be reduced. Electric vehicles could be a potential solution, since they are recently being promoted in Hong Kong (EPDHK 2022). According to Zhang et al. (2023), electric vehicles can decarbonize transportation and significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions using life cycle assessment from a spatiotemporal perspective. Their mass adoption can greatly improve this reverse logistics network. Current underutilized facilities can be efficiently used to cope with an increasing amount of CDW without expanding facility processing capacities.

Second, expanding existing facilities’ processing capacities is unnecessary. The capacity limit analysis shows that the current processing capacity is adequate to handle CDW. A 50% increase in facility capacities results in a noticeable decrease in utilization. Some experiments also show that the current situation can still handle CDW with a 20% increase. If CDW generation continues to rise, the processing capacities of the identified bottleneck facilities should be expanded first, rather than increasing the capacity of all facilities.

Third, controlling carbon emission limits could balance facility workloads. As transportation is the largest contributor to carbon emissions, reducing carbon emission limits would have a more negative impact on CDW transportation. This shortens CDW transportation, which means CDW has to be transported to the nearest downstream facilities. This control method is applicable when downstream facilities with a high operational cost are closer to high-utilization upstream facilities.

Fourth, those facilities with low utilization should reduce their unit operational cost when the unit transportation cost is high. The results reveal trade-offs between the transportation and operational costs. Thus, facility managers can increase their market share by implementing this strategy.

Conclusions

Motivated by real-life CDW recycling practices, this paper studies the reverse logistics network design problem for CDW recycling in Hong Kong. A multi-objective MILP model is proposed to design a multi-echelon reverse logistics network when there are the “three more problems” in Hong Kong CDW management. A four-layer theoretical framework is proposed to coordinate interests of multiple stakeholders and manage conflicting objectives while considering economic, environmental and efficiency principles. Under this framework, a MILP model is further formulated to minimize total costs and negative environmental impacts under uncertainties for developing a reverse logistics network of CDW. For model transformation, the \(\varepsilon\)-constraint method and fuzzy parameters are employed to conduct multi-objective optimization and quantify uncertainties in this model respectively. In this research, a case study from Hong Kong is selected to validate the proposed model, given a strong commitment to sustainable construction, circular economy initiatives, stringent environmental regulations, and advanced CDW recycling infrastructure. This case study demonstrates this model’s practicability, applicability, and effectiveness in designing reverse logistics networks for recycling and reusing CDW within the Hong Kong context. Extensive numerical studies are conducted to analyze and explore the impact of key parameters on designing a reverse logistics network in Hong Kong. Experimental results from this case study suggest that compared with other costs, transportation costs and emissions play a dominant role in reverse logistics network design, which underscores the need for route optimization and eco-friendly transport modes to reduce both environmental impacts and financial costs. Moreover, carbon emission caps can be employed as a critical policy control parameter to balance facility utilization and stabilize total costs for improving overall sustainability and reverse logistics network performance.

Future research can be conducted to integrate the vehicle routing problem into the reverse logistics network design problem. In practice, large dump trucks might be banned on some roads or be required to ship CDW within a specific time window (Wy et al. 2013). This integration facilitates planning more practical and efficient routes for reverse logistics networks at an operational level. CDW from prefabricated buildings can be investigated. Prefabricated construction has been mainstreamed in many countries (Zhang et al. 2021, Kang et al. 2022b). There will be a large amount of CDW related to prefabricated construction in the future. How to design reverse logistics networks for prefabricated buildings is important with consideration of their disassembly, recycling and reusing. Finally, the reverse logistics network design problem at an operational level can be further integrated with the waste management region optimization issue at a tactical level (Richter et al. 2021) to create a more comprehensive optimization framework that enhances coordination across different regions in CDW recycling.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

References

AECOM (2019) Re-use of construction materials will help UK meet net zero carbon emissions target. https://aecom.com/uk/press-releases/re-use-of-construction-materials-will-help-uk-meet-net-zero-carbon-emissions-target/. Accessed 27 February 2022

Ahmed RR, Zhang X (2021) Multi-stage network-based two-type cost minimization for the reverse logistics management of inert construction waste. Waste Manage 120:805–819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2020.11.004

Aider M, Dey I, Hifi M (2023) A hybrid population-based algorithm for solving the fuzzy capacitated maximal covering location problem. Comput Ind Eng 177:108982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2023.108982

Alshamsi A, Diabat A (2015) A reverse logistics network design. J Manuf Syst 37:589–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2015.02.006

Alumur SA, Nickel S, Saldanha-Da-Gama F et al. (2012) Multi-period reverse logistics network design. Eur J Oper Res 220(1):67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2011.12.045

Avotra AARN, Nawaz A (2023) Asymmetric impact of transportation on carbon emissions influencing SDGs of climate change. Chemosphere 324:138301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138301

Aydin N (2020) Designing reverse logistics network of end-of-life-buildings as preparedness to disasters under uncertainty. J Clean Prod 256:120341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120341

Bérubé JF, Gendreau M, Potvin JY (2009) An exact ϵ-constraint method for bi-objective combinatorial optimization problems: Application to the Traveling Salesman Problem with Profits. Eur J Oper Res 194(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2007.12.014

Besklubova S, Kravchenko E, Tan BQ et al. (2023) A feasibility analysis of waste concrete powder recycling market establishment: Hong Kong case. Environ Impact Assess Rev 103:107225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2023.107225

Borgonovo E, Plischke E (2016) Sensitivity analysis: A review of recent advances. Eur J Oper Res 248(3):869–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2015.06.032

Cao C, Liu Y, Tang O et al. (2021) A fuzzy bi-level optimization model for multi-period post-disaster relief distribution in sustainable humanitarian supply chains. Int J Prod Econ 235:108081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108081

Chu T, Ma J, Zhong Y et al. (2024) Shared recycling model for waste electrical and electronic equipment based on the targeted responsibility system in the context of China. Hum Soc Sci Commun 11:442. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02901-0

CSDHK (2022) Census and Statistics Department. https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/. Accessed 27 March 2022

Davis P, Aziz F, Newaz MT et al. (2021) The classification of construction waste material using a deep convolutional neural network. Autom Constr 122:103481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103481

Ding Z, Wang X, Zou PXW (2023) Barriers and countermeasures of construction and demolition waste recycling enterprises under circular economy. J Clean Prod 420:138235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138235

EPDHK (2009-2020) Waste Data & Statistics. Environment Protection Department. https://www.wastereduction.gov.hk/en/assistancewizard/waste_red_sat.htm. Accessed 27 March 2022

EPDHK (2020) Monitoring of Solid Waste in Hong Kong 2020. Environment Protection Department. https://www.wastereduction.gov.hk/sites/default/files/msw2020.pdf. Accessed 27 March 2022

EPDHK (2022) Promotion of Electric Vehicles in Hong Kong. Environment Protection Department. https://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/english/environmentinhk/air/prob_solutions/promotion_ev.html. Accessed 17 June 2022

Fu P, Li H, Wang X et al. (2017) Multiobjective location model design based on government subsidy in the recycling of CDW. Math Probl Eng 2017:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9081628

Govindan K, Bouzon M (2018) From a literature review to a multi-perspective framework for reverse logistics barriers and drivers. J Clean Prod 187:318–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.040

Guerra BC, Leite F, Faust KM (2020) 4D-BIM to enhance construction waste reuse and recycle planning: Case studies on concrete and drywall waste streams. Waste Manage 116:79–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2020.07.035

He L, Zhang L (2022) A bi-objective optimization of energy consumption and investment cost for public building envelope design based on the ε-constraint method. Energy Build 266:112133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2022.112133

Hu ZH, Sheu JB (2013) Post-disaster debris reverse logistics management under psychological cost minimization. Transp Res Pt B-Methodol 55:118–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trb.2013.05.010

Huang B, Wang X, Kua H et al. (2018) Construction and demolition waste management in China through the 3R principle. Resour Conserv Recycl 129:36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.029

Jiménez M, Arenas M, Bilbao A et al. (2007) Linear programming with fuzzy parameters: An interactive method resolution. Eur J Oper Res 177(3):1599–1609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2005.10.002

Kang K, Besklubova S, Dai Y et al. (2022a) Building demolition waste management through smart BIM: A case study in Hong Kong. Waste Manage 143:69–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2022.02.027

Kang K, Li M, Wu W et al (2022b) A case study of building information modeling-enabled prefab logistics for smart construction supply chain management. In: Lu W, Anumba CJ (eds) Research Companion to Building Information Modeling. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp 395–414. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839105524.00030

Kang K, Tan BQ (2023) Carbon emission reduction investment in sustainable supply chains under cap-and-trade regulation: An evolutionary game-theoretical perspective. Expert Syst Appl 227:120335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120335

Kargar S, Pourmehdi M, Paydar MM (2020) Reverse logistics network design for medical waste management in the epidemic outbreak of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Sci Total Environ 746:141183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141183

Krishnan S, Zulkapli NS, Kamyab H et al. (2021) Current technologies for recovery of metals from industrial wastes: An overview. Environ Technol Innov 22:101525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2021.101525

Li, RYM, Du H (2015). Sustainable construction waste management in Australia: a motivation perspective. Construction Safety and Waste Management: An Economic Analysis, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12430-8_1

Nawaz A, Chen J, Su X et al. (2022) Material based penalty-cost quantification model for construction projects influencing waste management. Front Env Sci 10:807359. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.807359

Nawaz A, Chen J, Su X (2023a) Exploring the trends in construction and demolition waste (C&DW) research: A scientometric analysis approach. Sustain Energy Techn 55:102953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2022.102953

Nawaz A, Chen J, Su X (2023b) Factors in critical management practices for construction projects waste predictors to C&DW minimization and maximization. J King Saud Univ Sci 35(2):102512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102512

Nußholz JLK, Nygaard Rasmussen F, Milios L (2019) Circular building materials: Carbon saving potential and the role of business model innovation and public policy. Resour Conserv Recycl 141:308–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.10.036

Pan X, Xie Q, Feng Y (2020) Designing recycling networks for construction and demolition waste based on reserve logistics research field. J Clean Prod 260:120841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120841

Pochampally KK, Nukala S, Gupta SM (2008) Strategic planning models for reverse and closed-loop supply chains. CrC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420054798

Prajapati H, Kant R, Shankar R (2019) Bequeath life to death: State-of-art review on reverse logistics. J Clean Prod 211:503–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.187

Rahimi M, Ghezavati V (2018) Sustainable multi-period reverse logistics network design and planning under uncertainty utilizing conditional value at risk (CVaR) for recycling construction and demolition waste. J Clean Prod 172:1567–1581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.240

Richter A, Ng KTW, Karimi N et al. (2021) An iterative tessellation-based analytical approach to the design and planning of waste management regions. Comput Environ Urban 88:101652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2021.101652

Shi Q, Ren H, Ma X et al. (2019) Site selection of construction waste recycling plant. J Clean Prod 227:532–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.252

Shi Y, Huang Y, Xu J (2020) Technological paradigm-based construction and demolition waste supply chain optimization with carbon policy. J Clean Prod 277:123331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123331

Soto-Paz J, Arroyo O, Torres-Guevara LE et al. (2023) The circular economy in the construction and demolition waste management: A comparative analysis in emerging and developed countries. J Build Eng 78:107724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107724

Srivastava SK (2008) Network design for reverse logistics. Omega-Int J Manage Sci 36(4):535–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2006.11.012

United Nations Environment Programme (2012) Sustainable, resource efficient cities–making it happen!: United Nations Environment Programme Division of Technology, Industry and Economics Paris, France

Wu ZZ, Yu ATW, Shen LY (2017) Investigating the determinants of contractor’s construction and demolition waste management behavior in Mainland China. Waste Manage 60:290–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2016.09.001

Wy J, Kim BI, Kim S (2013) The rollon–rolloff waste collection vehicle routing problem with time windows. Eur J Oper Res 224(3):466–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2012.09.001

Xin F, Wan X (2023) A sustainable solution to promote interest-based municipal solid waste management. Hum Soc Sci Commun 10:649. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02189-6

Xu J, Shi Y, Zhao S (2019) Reverse logistics network-based multiperiod optimization for construction and demolition waste disposal. J Constr Eng Manage 145(2):04018124. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001592

Xu Z, Elomri A, Pokharel S et al. (2017) Global reverse supply chain design for solid waste recycling under uncertainties and carbon emission constraint. Waste Manage 64:358–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2017.02.024

Yang C, Chen J (2020) Robust design for a multi-echelon regional construction and demolition waste reverse logistics network based on decision Maker’s conservative attitude. J Clean Prod 273(10):122909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122909

Yu ATW, Poon CS, Wong A et al. (2013) Impact of Construction Waste Disposal Charging Scheme on work practices at construction sites in Hong Kong. Waste Manage 33(1):138–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2012.09.023

Zhan J, Deng J, Xu Z et al. (2023) A Three-Way Decision Methodology With Regret Theory via Triangular Fuzzy Numbers in Incomplete Multiscale Decision Information Systems. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst 32(8):2773–2787. https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2023.3237646

Zhang C, Zhao X, Sacchi R (2023) Trade-off between critical metal requirement and transportation decarbonization in automotive electrification. Nat Commun 14:1616. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37373-4

Zhang W, Kang K, Zhong RY (2021) A cost evaluation model for IoT-enabled prefabricated construction supply chain management. Ind Manage Data Syst 121(12):2738–2759. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-12-2020-0735

Zhong S, Chen Y, Zhou J (2015) Fuzzy random programming models for location-allocation problem with applications. Comput Ind Eng 89:194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2014.11.013

Zhumadillayeva A, Orazbayev B, Santeyeva S et al. (2020) Models for oil refinery waste management using determined and fuzzy conditions. Information 11(6):299. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11060299

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (23YJC630158), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (RCBS20231211090512003), the third phase of high-level university construction of interdisciplinary innovation team project of Shenzhen University (24JCXK03), Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2022KCXTD027) and Guangdong Key Construction Discipline Research Ability Enhancement Project (2021ZDJS108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KK: writing—original draft, writing—reviewing, validation, conceptualization, methodology, software. BQ: methodology, modeling, validation, writing—reviewing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, K., Tan, B.Q. Multi-echelon reverse logistics network design in the context of circular economy: a Hong Kong case study. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 40 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04323-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04323-4