Abstract

This study explores the relationship between the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem and female entrepreneurial activity in 45 countries using Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). It highlights the importance of female entrepreneurship for economic and social development and examines how Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem elements collectively impact female entrepreneurial activity. Methodologically, it combines Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA) and fsQCA, using data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) 2022 and the 2018 Global Digital Economy Development Index Report. The research identifies key Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem configurations that foster high levels of female entrepreneurial activity, characterized by varying societal norms and support systems. This approach challenges traditional linear models by highlighting a spectrum of conditions influencing female entrepreneurial activity. The study integrates Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem into female entrepreneurship analysis, providing insights for policymakers and stakeholders. This research contributes to a deeper understanding of how digital transformation influences the landscape of female entrepreneurship, emphasizing the role of digital ecosystems in promoting inclusive entrepreneurship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The recent proliferation of global research on female entrepreneurial activity underscores the acknowledgment of female entrepreneurship as one of the most rapidly expanding sectors on a global scale (Alecchi and Radović-Marković, 2016; Mirjana, 2022), making significant contributions to innovation and wealth creation across all economies(Menzies et al., 2024). Entrepreneurial activity is widely regarded as a primary source of development in most developed and developing nations; it is often referred to as the driving engine of economic and social progress (Shepherd et al., 2000). The robust growth of female entrepreneurial activity has contributed to enhancing women’s social status, reducing unemployment rates, and improving their overall societal quality of life (Dheer et al., 2019; Dana et al., 2022). However, significant disparities exist in female entrepreneurial activity levels among different countries (Radović–Marković et al., 2021). The 2022 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) report reveals that among the surveyed nations, only a few, such as the Dominican Republic, Kazakhstan, Morocco, and Spain, have higher female entrepreneurial activity levels than their male counterparts. Therefore, promoting female entrepreneurial activities has become an urgent concern for many countries.

Existing research has explored the factors that shape female entrepreneurial activity, often classifying them at micro (e.g., entrepreneurial intention, social networks) and macro (e.g., societal norms, policy frameworks) levels (Jamali, 2009; Thébaud, 2015). However, most studies examine these factors in isolation, neglecting the interactions between them. Additionally, while the rise of the digital economy has significantly influenced entrepreneurial ecosystems (Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2020; Salamzadeh and Ramadani, 2021), there is limited research on how digital technologies shape female entrepreneurship within this evolving landscape. Digital technology acts as a sociotechnical system that interacts with economic and social structures, offering new opportunities and constraints for women entrepreneurs (Sussan and Acs, 2017).

Previous research has primarily focused on the influence of singular factors on female entrepreneurial activities (Angulo-Guerrero et al., 2024), often neglecting the intricate interrelationships among various elements within the entrepreneurial ecosystem and their collective impact on female entrepreneurship. Female entrepreneurial endeavors are shaped by a myriad of influences, including sociocultural contexts, economic conditions, policy support, and technological innovation(Alecchi and Radović-Marković, 2016; Mirjana, 2022). However, studies frequently examine these factors in isolation, failing to delve into the ways they interact to create a more holistic understanding. This study aims not only to unveil the complexities of the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem but also to systematically analyze the synergistic effects between the digital economy and the entrepreneurial landscape, exploring how they jointly enhance or constrain the vitality of female entrepreneurship. Moreover, prior investigations have often lacked a comprehensive analysis of the multilayered factors influencing the dynamism of female entrepreneurship (Yang et al., 2024b; Alhajri and Aloud, 2024). These factors may encompass the personal characteristics of entrepreneurs, social networks, accessible resources, and the policy environment. This study proposes a comprehensive theoretical framework concerning the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem, integrating perspectives from the digital economy and deeply examining the macro-contextual influences on female entrepreneurial efforts, thereby providing broader insights for future research and policy formulation. Through this framework, we aspire to delineate more clearly how these factors interact at various stages and contexts of female entrepreneurship. Finally, while previous studies have rarely addressed the asymmetry of causal relationships, this research will employ the fsQCA method to confirm that the pathways leading to high levels of entrepreneurial activity are not simply opposed to those resulting in low entrepreneurial participation. This understanding will contribute to a more nuanced comprehension of the disparities in entrepreneurial efficiency across different nations and the complex interdependencies among various conditions. By thoroughly analyzing these pathways, this study hopes to offer practical recommendations for policymakers and practitioners to foster the sustainable development of female entrepreneurship.

Specifically, this research seeks to answer the following questions: What pathways enhance female entrepreneurial activity? Which pathways activate female entrepreneurship more efficiently? Which pathways result in non-high female entrepreneurial activity? Finally, we discuss the theoretical and practical implications and identify research limitations to delineate future research opportunities.

Literature review

Digital entrepreneurial ecosystem

Digital entrepreneurial ecosystem has become crucial to innovation, entrepreneurship research, and practice (Hechavarría and Ingram, 2019; del Olmo-García et al., 2023; Marquardt and Harima, 2024). The fusion of the digital economy with entrepreneurial ecosystems can yield a “multiplicative effect,” giving rise to the theory of the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem (Elia et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2024). This theory is defined as the mutual matching of digital consumers (users and agents) on online digital platforms, reducing transaction costs and realizing value and societal benefits for both parties (Song, 2019; Karaki, 2021). Sussan and Acs (2017) integrated two existing ecosystem studies, namely, the entrepreneurial ecosystem focusing on institutions and institutional roles and the digital ecosystem concentrating on hardware infrastructure and digital network users, to construct the theoretical framework of Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Existing research has primarily focused on the causal relationship between entrepreneurial ecosystems and female entrepreneurial activity (Huang et al., 2022b), often neglecting the broader context of the digital economy (Khodor et al., 2024). Additionally, research on digital technologies has received limited attention, and discussions on the role of digital technology in female entrepreneurship are scarce. The ecosystem in which digital enterprises operate is a vital component of growth. This lays the theoretical groundwork for an in-depth examination of the relationship between the Digital entrepreneurial ecosystem and female entrepreneurship (Elia et al., 2020). Given that the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem can facilitate the integration of supportive conditions beyond the entrepreneurial entity level (Hechavarría and Ingram, 2019), it plays a pivotal role in the success of the female entrepreneurship.

Financial capital

Financial capital refers to the monetary resources available to enterprises that support new ventures and entrepreneurial activities (Mueller and Thomas, 2001; Tan et al., 2024). Sufficient financial capital is essential for acquiring equipment and materials, preventing liquidity issues, and ensuring sustainable operations (Díez-Martín et al., 2016; Garg et al., 2024). Studies suggest that financial constraints limit entrepreneurship, while access to capital promotes it (Deng et al., 2024).

Female entrepreneurs face barriers such as gender discrimination, limited social networks, and biases about their capabilities, which restrict funding sources and affect their confidence and decision-making (Cetindamar et al., 2012; Aloulou et al., 2024). Women also experience greater economic constraints, encountering loan rejections, small loan sizes, and high interest rates (Bui et al., 2018). As a result, they often rely on informal sources like family and friends, which are limited and may not meet business needs (Wu et al., 2019).

Infusions of financial capital diversify funding options and ease capital scarcity (Alvarez et al., 2013). Moreover, financial capital enhances trust, creates favorable financing conditions, and attracts investors through developed capital markets (Bosse and Taylor, 2012). High-quality financial services and supportive financial environments are crucial, especially for female entrepreneurs, in reducing liquidity challenges and encouraging entrepreneurial participation (Huang et al., 2022b; Avnimelech and Rechter, 2023).

Government policies

The government is recognized as a public organization responsible for formulating and implementing public decisions and maintaining orderly management (Brush et al., 2019; Zamani and Rousaki, 2024). An entrepreneurship policy consists of rules established by the government that influence transaction costs, uncertainty, and the risks associated with initiating, operating, and closing businesses (Beynon et al., 2018; Candeias and Sarkar, 2024).

Research shows that government policies support can foster female entrepreneurial activity (Candeias and Sarkar, 2024). Women-led startups often face challenges (Salamzadeh et al., 2022), such as smaller scale, intense industry competition, slim profit margins, and a heightened risk of failure, among other entry barriers. Supportive entrepreneurship policies mean female entrepreneurs are more likely to gain legitimacy, reduce uncertainty, protect their creativity, access resources, and engage in proactive entrepreneurship (Huang et al., 2024). The government can also build entrepreneurial support networks to provide resources and information, helping female entrepreneurs expand their business connections. This fosters collaboration among women entrepreneurs and enhances resource sharing, ultimately increasing the success rate of their ventures (Aloulou et al., 2024; Agarwal et al., 2022; Belitski et al., 2023). Research shows that tailored entrepreneurship support policies that address local realities can significantly increase the likelihood of success for female entrepreneurs (Petridou et al., 2024), the government helps women acquire the necessary business knowledge and skills through entrepreneurship training and skill enhancement programs.Research indicates that the implementation of these policies helps eliminate the institutional barriers women face in the early stages of entrepreneurship (Carter et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2024). Policy interventions such as financial subsidies, tax reductions, and entrepreneurship training can effectively lower the economic barriers to women’s entrepreneurship (Pérez-Morote et al., 2024).

Human capital

Human capital is a composite capacity encompassing the knowledge, skills, and health status individuals acquire through education, training, and other forms of experience (Kousar et al., 2023; Sebola, 2023). It comprises four dimensions: physical, intellectual, and social abilities (Becker, 2009; Xu et al., 2024). Human capital is a crucial factor in the entrepreneurial process (Haber and Reichel, 2007; Atarah et al., 2023). It is a vital determinant for identifying opportunities and facilitating entrepreneurship (Huang et al., 2022a). Research has indicated that human capital exerts a positive influence on entrepreneurship; however, this impact is generally weaker for female entrepreneurs compared to their male counterparts (Nyakudya et al., 2024). Human capital is a critical determinant of female entrepreneurship and is widely used to predict entrepreneurial propensity (Ozaralli and Rivenburgh, 2016;Epure et al., 2024). Education, experience, skills, and knowledge are attributes of human capital (Schultz, 1961). Knowledge is seen as a source for discovering and exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities, enhancing cognitive abilities among women, and enabling female entrepreneurs to perceive and act effectively in new entrepreneurial endeavors. Research indicates that experienced female entrepreneurs are more adept at identifying business opportunities than novice female entrepreneurs (Kong and Kim, 2022). Providing effective entrepreneurship education can enhance individuals’ entrepreneurial abilities (Sevilla-Bernardo et al., 2024). Education can enhance the professional attractiveness of entrepreneurship, improve the ability to identify, assess, and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities, and develop relationship-specific skills (Bui et al., 2018). Studies suggest that a positive attitude toward entrepreneurship is essential for women considering future self-employment, and education plays a pivotal role in this process (Ester et al., (2017)). A favorable educational system for entrepreneurship can produce a significant labor force skilled in entrepreneurship and business management, stimulating potential entrepreneurs to engage in entrepreneurial activities. Entrepreneurship education is one of the most critical components of human capital that promotes female entrepreneurial activity (Hassan et al., 2024; Preisendörfer and Voss, 1990). Research indicates that the level of education, entrepreneurial experience, financial literacy, training, and vocational skills of women can enhance their entrepreneurial performance (Ajiva et al., 2024; Kamberidou, 2020). The rapid regional economic growth is supported by an increasing presence of women with strong human capital entering the entrepreneurial field, along with accelerated overall development (Fauzi et al., 2023; Sobhan and Hassan, 2024).

Market environment

In the literature, the market is defined as an arena for identifying, attracting, and retaining customers (Guerola-Navarro et al., 2024; Ojong et al., 2021). Market environment influences the scale of women-owned businesses by enhancing their customer bases and cash flows (Stokes, Wilson (2010)). The more exposure female entrepreneurs have to the local market at the early stages of their ventures, the higher their likelihood of achieving entrepreneurial success (Welsh et al., 2023). First, a highly open market environment facilitates greater access to technology, capital, and information, thereby creating a fertile ground for entrepreneurship (Odeyemi et al., 2024). Therefore, female entrepreneurs can access more resources in an open market environment, improve resource utilization efficiency, and drive greater product development efforts (Díez-Martín et al., 2016). Second, an open market environment means fewer barriers to entry and constraints on female entrepreneurs, which enhances their entrepreneurial motivation. The current digital technology environment can more effectively mitigate the entrepreneurial barriers faced by women, positioning itself as a crucial driving force for female entrepreneurship (Salamzadeh and Ramadani, 2021; Salamzadeh et al., 2024). Third, a positive open market environment increases market demand (Bui et al., 2018; Yoruk and Jones, 2023). Therefore, positive open market environment implies that women have more opportunities to engage in entrepreneurial activities and develop businesses.

Social norms

The concept of social norms is rooted in the psychology of planned behavior, which refers to the perceived social pressure manifested as the intention to perform or abstain from a particular action (Ajzen, 1991). In the current context, individuals’ normative beliefs about entrepreneurial activities are linked to their subjective consciousness, influencing their entrepreneurial behavior. This study found that social norms had a positive driving effect on female entrepreneurship (Brush, 2008; Karim et al., 2023). Therefore, with the support of social norms, women are more likely to perceive their entrepreneurial actions as conforming to societal expectations; these norms can motivate them. This, in turn, enhances the perceived legitimacy of entrepreneurship and encourages women to engage in it (Yunis et al., 2018). The existing research suggests that the proportion of women engaged in entrepreneurship in different countries is related to the normative support they receive (Patrício and Ferreira, 2024). Women are less likely to engage in entrepreneurial activities in countries with weak institutional support (Meyer, 2018; Johnson and Mehta, 2024; Aloulou et al., 2024). Female entrepreneurial activities are more influenced by cultural norms than men, and female entrepreneurial intentions and concepts are more affected by culture (Grootaert and Van Bastelaer, 2001). Therefore, an underlying bias may exist when mainstream societal views suggest that women do not possess the necessary prerequisites for entrepreneurship. If women’s enterprises are more susceptible to the influence of the surrounding societal values and expectations, social norms regarding entrepreneurship may have a stronger impact on female entrepreneurial activity levels (Hechavarría and Ingram, 2019).

Infrastructure

In the realm of business operations, infrastructure encompasses the availability of essential physical resources, such as high-speed broadband, public utilities, and various other assets. This infrastructure is instrumental in economic processes, particularly in fostering opportunities for growth and enhancing productivity (Yang et al., 2024a). Infrastructure investments facilitate entrepreneurial opportunities and typically enhance connections between individuals, which, in turn, benefit entrepreneurial activities (Canning and Pedroni, 2008). Woolley (2014) suggests that infrastructure can stimulate entrepreneurial opportunities, allowing startup entrepreneurs to seize these opportunities by establishing new companies (Woolley, 2014). A tangible framework is essential for entrepreneurship. Access to tangible infrastructure can accelerate the acquisition of relevant resources, such as offices, equipment, transportation, telecommunications, and basic utilities, thereby promoting entrepreneurship. Research shows that infrastructure development has a promotional effect on female entrepreneurship (Venkatesh et al., 2017). Improving Ifra, such as information and communication technology, enhances female entrepreneurs’ connections with the outside world and increases the size and diversity of their social networks (Brush et al., 2019), enabling them to better identify and expand the scope of entrepreneurial opportunities (Yousafzai et al., 2015), ultimately leading to improved entrepreneurial performance and greater involvement in entrepreneurial activities.

Digital economy

The concept of digital economy is sometimes called a new economy or Internet economy (Hamid and Khalid, 2016; Zhang et al., 2024). A U.S. Department of Commerce report titled “The Emerging Digital Economy” provides a more specific definition. This report describes digital economy as a form of business activity based on industries and information technology, characterized as an inclusive sharing economy that provides equal opportunities, enabling entrepreneurial groups to engage in entrepreneurial activities more effectively (Kling and Lamb, 1999). Female entrepreneurs embrace digital technologies and cultivate innovative forms of entrepreneurial behavior that transcend conventional industry boundaries. This includes the establishment of networks, ecosystems, and communities, which collectively expedite the emergence and evolution of new business ventures (Kamberidou, 2020; Alhajri and Aloud, 2024). Previous research in feminist studies has explored women’s attitudes toward digital technology, emphasizing how the Internet can reduce the barriers encountered in traditional entrepreneurship (Nambisan, 2017). Women can benefit from digital developments with increased flexibility in work and reduced liquidity constraints (Elia et al., 2020). By using digital media platforms such as crowdfunding, women can access and absorb new knowledge more conveniently, enabling them to directly access business and financing opportunities. Female entrepreneurs increasingly need to interact with digital infrastructure, dynamic digital businesses, and financial markets. Lowering entrepreneurial barriers and the availability of rich information from the Internet can provide women with significant entrepreneurial advantages. The digital transformation of the economy and society is expected to change the entrepreneurial environment, giving more prominence to alternative sources of financing based on Internet platforms, such as crowdfunding and peer-to-peer lending, and increasing market opportunities for potential entrepreneurs, including women (Nambisan, 2017). Therefore, women tend to engage in entrepreneurial activities against the backdrop of digital economy.

Theory of digital entrepreneurial ecosystem and female entrepreneurial activity from a configurational perspective

The complex adaptive system approach is recommended for studying entrepreneurial ecosystems due to their characteristics of having numerous interacting elements, nonlinearity, and interdependency (Abootorabi et al., 2021). This study aims to lay a theoretical and practical foundation for a deeper understanding of the impact mechanisms of various factors within the Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem on female entrepreneurial activity. However, in previous research, the linear relationship between the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem and female entrepreneurship was unclear (Ragin, 2006). It was also challenging to provide answers regarding configurational effects involving multiple factors, especially three or more; consequently, it was difficult to uncover the necessary conditions and sufficient causal relationships. Furthermore, gaining insights into the complex causal relationships among the multiple elements of the Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem affecting female entrepreneurial activity has proved challenging. In reality, these elements do not exhibit a symbiotic or competitive relationship with one another; rather, they interact and match, altering the entrepreneurial environment and thus influencing female entrepreneurship.

From a holistic viewpoint, the configurational perspective attempts to explain how elements interact as a whole (Dul, 2016). This perspective posits that organizations are best understood as interconnected structures and clusters of practices rather than as isolated or loosely connected entities (Dul et al., 2020). Therefore, understanding organizations cannot be achieved by analyzing individual components in isolation, aligning with the holistic approach that we seek to understand Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Consequently, the configurational perspective is well suited to exploring the nonlinear, equifinal, and asymmetric causal complexities of the relationship between the Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem and female entrepreneurial activity. Moreover, the impact mechanisms of Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem on female entrepreneurship can be broadly categorized into two aspects: one influences the perception of gender roles in entrepreneurship (Brush et al., 2019), and the other influences women’s perception of resources and capabilities for entrepreneurship (Huang et al., 2022b). The former involves creating a supportive social atmosphere for female entrepreneurship and enhancing female identification with the legitimacy of their entrepreneurial activities, thus elevating their perception of entrepreneurship. The latter entails optimizing government policies and market conditions to improve the accessibility of resources and entrepreneurial capabilities for women in entrepreneurship.

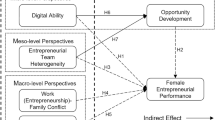

In summary, the effects of various elements of Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem on female entrepreneurship remain an open question. Based on the configurational perspective, this study focuses on uncovering the causal and complex mechanisms through which Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem influences high levels of female entrepreneurial activity, as illustrated in the theoretical framework in Fig. 1.

Research hypothesis

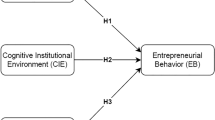

Based on previous research, the Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) method entails two fundamental hypotheses. First, there is a conjunctural causation assumption, where interrelated antecedent conditions forming different combinations result in multiple causal relationships. Second, there is an equifinality assumption, in which multiple configurations lead to the same specific outcome. This study employed the QCA method to investigate the pathways through which the elements of Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem synergistically activate female entrepreneurial activity. This study establishes hypotheses based on the combined driving paths of antecedent variables, focusing on causal relationships from both the compositional and equifinal perspectives.

The perspective of compositional relationships

This notion connects various social phenomena and attributes them to the interactions among different factors (Fiss, 2011). Female entrepreneurship is a dynamically evolving process that encompasses multiple dimensions, such as macroeconomic, cultural, social, and individual characteristics at the micro level. This process is influenced by numerous factors, including the economic development level, government policies, social norms, and individual traits (Dehghanpour Farashah (2013)). This study investigates how the synergistic configuration of seven antecedent variables within the Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem affects female entrepreneurial activity and subsequently explores the pathways that drive high levels of female entrepreneurial activity. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (compositional): The female entrepreneurial activity level is determined by the configuration formed by the seven major system elements of Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem.

The perspective of equifinality

This suggests that multiple configurations of driving paths can potentially lead to the same outcome without a singular optimal solution. This study posits that by combining various factors, such as female entrepreneurs, the market, government, and others, and integrating the complex environment with the resources at their disposal, the heterogeneous knowledge and skill proficiency of female entrepreneurs can be enhanced. This approach can potentially activate high female entrepreneurial activity levels. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (equivalency): Within various systemic factors, including financial capital, government policies, human capital, market environment, social norms, infrastructure, and digital economy, multiple configurations can enhance female entrepreneurial activity.

Research methods

Mixed methodology of necessary condition analysis (NCA) and FsQCA

Necessary and sufficient causality are two emerging explanations of causal relationships. Necessary causality refers to a situation in which the absence of a certain cause results in the non-occurrence of the effect (Charles, 2008; Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2023). In contrast, sufficient causality indicates that the cause (or combination of causes) adequately produces the result (Dul, 2016). To better analyze the necessary and sufficient causal relationships in this study, a novel NCA approach has been employed along with the QCA method, which excels in analyzing sufficient causal relationships.

First, this study employs NCA to examine whether specific psychological cognitive factors are necessary conditions for generating female entrepreneurial activity, and if so, at what level. Second, the fsQCA method explored the intricate causal mechanisms that activate female entrepreneurial activity. The fsQCA adopts a holistic perspective for cross-case comparative analysis, aiming to explore the configurations of sets of conditions that lead to the emergence of expected outcomes and those that result in the absence or non-occurrence of expected outcomes, addressing intricate causal complexity issues (Dul et al., 2020).

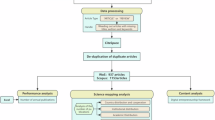

Data source and sample

The analysis presented in this article draws from two primary data sources. The indicators of financial capital, government policies, human capital, market environment, social norms, and infrastructure are derived from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) report. In contrast, the digital economy metrics originate from the report titled Global Digital Economy Development Index, published by Alibaba Research Institute. The data cleaning and matching procedures are as follows: (1) from the Global Digital Economy Development Index report, a selection of 113 countries with comprehensive digital economy development indicators was made; (2) based on the adult survey section of the GEM report, 47 countries with complete indicators of female entrepreneurship activity were identified; (3) the countries exhibiting both digital economy development indices and female entrepreneurship activity data were then matched, resulting in the exclusion of 68 countries with missing indicators, thereby yielding a final sample of 45 complete countries.

The explanations for each indicator are as follows:

The female entrepreneurial activity refers to the proportion of women engaged in entrepreneurial activities in a country. It specifically measures the percentage of women between 18 and 64 who are either new entrepreneurs or business managers. financial capital is measured from two aspects: the availability of sufficient entrepreneurial funds for new entrepreneurs and the ease of obtaining entrepreneurial funds. This study considered the average of these two aspects as the data points. Government policies is divided into two aspects: policy support and the tax system. It measures the degree of public policy support for entrepreneurship and the corporate tax burden. This study considered the average of these two aspects as the data points. Human capital is divided into two aspects: foundational and high-level entrepreneurial education. This includes whether entrepreneurship concepts are introduced in primary and secondary schools and whether universities offer entrepreneurship courses. This study considered the average of these two aspects as the data points. ME measures the degree of freedom for new enterprises to enter the market and whether the market maintains freedom, openness, and continuous growth. infrastructure measures the ease with which startups can access tangible material resources (e.g., communication, infrastructure, land, and space). social norms gauges the degree to which the social environment and cultural norms incentivize or support entrepreneurship to enhance individual wealth and income. The DE measures the extent of digital development. It is calculated by weighing the digital infrastructure (20%), digital research (20%), digital public services (20%), digital consumers (20%), and the digital industrial ecosystem (20%) to derive the Digital Economy Development Index.

Data calibration

Calibration is the process of assigning set membership degrees to cases. Before calibrating the data, three anchor points were set: full membership, mid-membership, and no membership. After calibration, the set membership degrees ranged from 0 to 1. This study used the 25%, 55%, and 75% percentiles of the sample data distribution as the three anchor points. The calibrated anchor points and descriptive statistics for each variable are presented in Table 1.

Results

Necessity analysis of single conditions

NCA can discern whether a specific condition is unnecessary for an outcome and can handle both continuous and discrete cases. When both variables were continuous or discrete, with more than five levels, an upper-bound regression, i.e., ceiling regression (CR), was employed to establish the upper-bound function. When both the conditioning and outcome variables are binary or have discrete levels below five, the ceiling envelopment (CE) method is used to construct the corresponding functions. With these functions in place, the magnitude of the influence can be analyzed.

Table 2 presents the results of the NCA using the CR and CE estimations, including the number of effects. In the NCA method, necessary conditions must satisfy two requirements: effect size (d) > 0.1 (Dul, 2016), and the results of Monte Carlo simulations of permutation tests show that the effect size is significant (Dul et al., 2020). In summary, while financial capital and social norms have significant impacts, their effect sizes are too small to be considered as necessary elements for female entrepreneurial activity. By contrast, the validation results for government policies (p = 1.0), human capital (p > 0.05), ME (p = 1.0), infrastructure (p = 1.0), and DE (p = 1.0) were not significant and had small effect sizes. Therefore, these factors were not deemed necessary for the female entrepreneurial activity.

Building on this, we conducted an in-depth verification analysis of the required conditional variables using fsQCA. Table 3 shows necessity test for a single condition. It shows that the consistency data for the necessity of each factor are consistently below 0.9, indicating that none of the conditional variables is a necessary condition for the outcome variables in this study. This conclusion aligns with the analysis findings of the NCA, suggesting the absence of the necessary antecedent conditions that lead to a high female entrepreneurial activity.

Sufficiency analysis

A combined analysis of conditions was primarily employed to examine the explanatory power of different combinations of antecedent variables on the outcome variable. By introducing the seven conditional variables into fsQCA 3.0 and using the fsQCA module for computation, regarding previous research (Tavakol, 2018), this study sets the consistency threshold at 0.8 and the case frequency threshold at 1. As per the software settings, assignments greater than 0.7 are assigned a value of 1 in the truth table, while assignments less than 0.7 are assigned a value of 0. A value of 1 represents a higher level of that factor, and 0 represents a lower level. As shown in Table 4 and 5, the results ultimately retained four paths leading to a high female entrepreneurial activity and six paths leading to a low female entrepreneurial activity.

Discussion

Driving mechanisms of female entrepreneurial activity

The fuzzy set analysis identified four configurations for generating a high female entrepreneurial activity (as shown in Table 4), with consistency values of 0.928, 0.869, 0.876, and 0.818. The results indicate that these four configurations are sufficient for achieving high female entrepreneurial activity. The obtained solution consistency index was 0.897, suggesting that the four configurations covering most case countries can be considered sufficient conditions for high female entrepreneurial activity. The model coverage ratio was 0.344, indicating that the four configurations of the analytical results could explain the mechanisms behind ~35% of the high female entrepreneurial activity. Table 4 shows the configurations for achieving high female entrepreneurial activity.

-

(1)

Infrastructure-Driven by Social Norms Support

In configuration H1, despite the disparities in governmental policies regarding support for women’s entrepreneurial activities, the backing of society emerges as particularly vital in the face of inadequate financial resources, unfavorable market conditions, and the underdevelopment of human capital and the digital economy. Research indicates that women often encounter constraints imposed by environmental factors during their entrepreneurial endeavors, especially in contexts characterized by a lack of funding and market opportunities, which may diminish the efficacy of governmental initiatives. However, if various societal stakeholders actively cultivate an environment conducive to female entrepreneurship—such as providing entrepreneurial training and establishing networks and communities for women entrepreneurs—then the intent of women to engage in entrepreneurial activities is likely to experience a significant enhancement.Furthermore, robust infrastructure development is equally paramount. For instance, improvements in transportation, communication, and information technology infrastructure can reduce operational costs for women entrepreneurs, thereby augmenting their market competitiveness. As infrastructure becomes more sophisticated, female entrepreneurs will find it easier to access resources and information, bolstering their confidence and aspirations for entrepreneurship. This synergistic interaction between societal support and infrastructure enhancement has the potential to invigorate women’s entrepreneurial engagement, enabling them to identify opportunities even amidst adversity, and thereby promoting diversity and innovation within the broader economy. Consequently, even in the absence of substantial policy support, proactive societal involvement and infrastructure advancements can create a favorable environment for women entrepreneurs, leading to heightened levels of entrepreneurial activity.

Based on the GEM report, the Dominican Republic stands as a representative case among entrepreneurship ecosystems, receiving a score of 2.4 for entrepreneurial financing conditions and 2.8 for financing accessibility—both the lowest among C-tier economies on the entrepreneurship index. Similarly, experts rated market activity with comparably low scores. However, the Dominican Republic received a score of 6.7 in infrastructure, ranking second among C-tier economies, and a fifth-place ranking for social norms, while it achieved the highest female entrepreneurship activity. These findings align well with the typical characteristics of infrastructure-driven configurations underpinned by supportive social norms, as discussed in this paper.

-

(2)

Social Norms-Government Policies-Human Capital Support-Driven

In configuration H2a, regardless of the sufficiency of financial resources, when infrastructure and the development of the digital economy are relatively lagging, the combination of societal and governmental support for entrepreneurial activities, along with ample human capital, can significantly enhance the success rate of female entrepreneurs. Specifically, the government can implement policy incentives and financial backing to motivate women to engage in entrepreneurship. For instance, establishing dedicated funds or offering tax incentives can lower the initial investment barriers for female entrepreneurs. Additionally, enhancing education and skill training to elevate women’s professional competencies and market competitiveness will further facilitate their entrepreneurial success. In configuration H2b, despite the inadequacies in infrastructure and the underdevelopment of the digital economy, as long as societal and governmental support for entrepreneurship remains steadfast, women’s participation in entrepreneurial endeavors can still be maintained at a high level. In this context, abundant human capital and the freedom of the market, particularly through an improved financing environment, play a critical role. Increased market freedom allows female entrepreneurs to operate flexibly within a broader market context, while a favorable financing environment provides the essential financial support needed to help them overcome initial funding challenges. Thus, the dual impact of policy guidance and market mechanisms can effectively enhance the activity levels of female entrepreneurs, fostering a robust entrepreneurial ecosystem.In summary, these two configurations underscore the significance of social support and human capital in the vibrancy of female entrepreneurship, while indicating that the effects of infrastructure and digital economic development on women’s entrepreneurial activities can be alleviated through external support and improvements in the market environment. This comprehensive perspective offers vital insights for policymakers, emphasizing the need to consider multifaceted factors when promoting female entrepreneurship, particularly in resource-constrained settings, and to establish a more holistic support system to facilitate the overall development of female entrepreneurs.

According to the GEM report, Kazakhstan exemplifies the characteristics of a nation with strong support for entrepreneurship through social norms, receiving a score of 5.6, ranking second overall. This robust entrepreneurial culture could counteract potential pessimism toward entrepreneurship during periods of economic contraction. Experts rated the relevance of government policies highly, awarding a score of 5.6, the second highest among B-tier economies. Kazakhstan’s human capital ranks mid-range, while scores for infrastructure and the digital economy are lower; nevertheless, female entrepreneurship activity ranks fourth. This profile aligns with the configuration solution identified in this study, driven by social support, government policies, and human capital. In Configuration H2b, India represents a notable example, achieving the highest scores for financial capital and government policies among C-tier economies, with its market environment scoring second (6.2), social norms fourth (6.4), human capital first (3.8), and a lower digital economy score. Female entrepreneurship activity surged in 2022. This profile reflects the configuration solution outlined in this paper, characterized by support from social norms, government policies, and human capital. The original coverage level for this configuration is among the highest, suggesting it may provide a pathway with broader impact on promoting high levels of female entrepreneurship activity.

-

(3)

Human Capital-Driven by Social Norms Support

In configuration H3, despite the formidable challenges posed by insufficient financial capital, limited governmental policy support, an unfavorable market environment, underdeveloped digital economy, and inadequate infrastructure, the entrepreneurial recognition among women can still experience a notable enhancement, provided that society maintains a supportive attitude toward female entrepreneurship. In such an environment, women not only perceive encouragement from family, friends, and the broader community but also gain access to invaluable information and resources through participation in entrepreneurial networks and communities.Moreover, possessing substantial human capital emerges as a crucial determinant of women’s entrepreneurial success. The state should bolster entrepreneurial education for women by establishing dedicated training programs and incubation centers that enhance their business acumen, managerial competencies, and market awareness. As these support measures are implemented, we can anticipate a continual rise in women’s entrepreneurial activity. This transformation will not only create additional employment opportunities for women but also stimulate overall economic growth and innovation within society. Thus, considering these factors holistically, it is evident that even in less-than-ideal conditions, women can thrive within a nurturing social atmosphere, thereby fostering diversity and inclusivity in the community.

The GEM report highlights Colombia as a representative case, scoring 3.4 in entrepreneurial financing framework conditions, ranking tenth, and 3.5 in financial capital, placing seventh. Experts also identified government policy as a limiting factor, ranked seventh; despite improvements since 2020, challenges related to taxes and bureaucratic hurdles continue to constrain the expansion of venture capital. Nevertheless, Colombia achieved a high ranking for social norms at 5.8 (second place) and human capital at 5.9 (first place), fostering a renewed rise in female entrepreneurship activity. This profile aligns with the mechanisms characteristic of a human capital-driven configuration supported by social norms, as discussed in this study.

Analysis of mechanisms driving low female entrepreneurial activity

Six configurations were observed from the fuzzy set analysis results (as shown in Table 5). The consistency index values for the six configurations are 0.938, 0.960, 0.898, 0.932, 0.940, and 0.834. These results indicate that all six configurations have sufficient conditions, leading to a low female entrepreneurial activity. However, the consistency index for the configuration solutions was 0.894, and that for the model coverage data was 0.473. These six configurations encompass a significant portion of the case countries, constituting sufficient conditions for low female entrepreneurial activity and explaining ~50% of the mechanisms driving low female entrepreneurial activity among non-high women. Table 5 shows the configurations for achieving low female entrepreneurial activity.

Configuration H4a indicates that regardless of the quality of infrastructure, even with improvements in the financing environment, optimization of social norms, increased investment in human capital, and development of the digital economy, neglecting improvements in government policies and market conditions remains the primary cause of low female entrepreneurial activity among non-high women. In configuration H4b, only improving the financial capital and infrastructure while neglecting other digital entrepreneurial ecosystem elements was the primary cause of the low female entrepreneurial activity among non-high women. Configuration H5 indicates that regardless of the adequacy of financial capital, even with government policies supporting female entrepreneurship, optimization of infrastructure, enhanced human capital, and development of digital economy, disregarding the optimization of social norms and improvements in market environment remains the main cause of low female entrepreneurial activity among non-high women. In configuration H6, even with government policies supporting female entrepreneurship, the lack of improvement in other factors within the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem is a significant reason for the relatively low female entrepreneurial activity level. In configuration H7, although a positive financing environment is cultivated, infrastructure is improved, an entrepreneurship policy encouraging women’s participation is formulated, and there is accelerated development in the digital economy landscape. The primary cause of low female entrepreneurial activity among non-high women is the absence of social norms and human capital. Configuration H8 indicates that regardless of government policies supporting female entrepreneurship, even if other elements of the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem are well developed, neglecting the improvement in market environment remains the primary cause of low female entrepreneurial activity among non-high women.

Robust analysis

This study altered the calibration points of the data by changing them to 0.95, 0.50, and 0.05 to conduct robustness tests on the driving configurations leading to a high female entrepreneurial activity. The configurations of the new model exhibited a clear subset relationship with those of the original model (Fiss, 2011). To further test the robustness of the conclusions, this study reduces the consistency threshold of the PRI to 0.75 and, through robustness testing, obtains an entirely new configuration that leads to a high female entrepreneurial activity. The configuration pathways between the new and original models exhibited a distinct subset relationship (Kraus et al., (2018)), indicating that the research results were relatively reliable.

Research conclusions and implications

Research findings

This study reveals the intricate causal mechanisms influencing female entrepreneurial activity from the perspectives of Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem and configurations. First, a single element of the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem is not necessary for obtaining a high female entrepreneurial activity value. This research deepens the understanding of various factors, such as market environment, government policies, human capital, and social norms, that are associated with female entrepreneurial behavior (Hechavarría and Ingram, 2019). Moreover, a strong social norms has a broader impact, subsequently influencing the effects of other elements on digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Additionally, this study confirms that social norms significantly influences female entrepreneurial cognition concerning gender roles (Grootaert and Van Bastelaer, 2001). Furthermore, the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem generating a high female entrepreneurial activity can be classified into four types. Among them, the “Social Norms-Government Policies-Human Capital Support-Driven” type is more likely to effectively stimulate female entrepreneurship. Conversely, digital entrepreneurial ecosystems that lead to low female entrepreneurial activity can be classified into six types. Additionally, an asymmetrical relationship exists between the driving mechanisms of high female entrepreneurial activity and those of low female entrepreneurial activity. Finally, this study integrates the seven major elements of the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Previous research has primarily focused on examining the impact of factors such as social norms, government policies, human capital, market environment, and financial capital on female entrepreneurial activity (Yousafzai et al., 2015) while overlooking the influence of digital economy on female entrepreneurial activity (Thébaud, 2015). This study comprehensively explored the relationship between the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem and female entrepreneurship.

Theoretical contributions

First, previous research has been limited in providing a clear understanding of the underlying mechanisms through which elements of the entrepreneurial ecosystem influence female entrepreneurial activity. Therefore, this study enriches the findings of digital entrepreneurial ecosystem theory within the realm of female entrepreneurship. This study examines the synergistic linkage mechanisms between entrepreneurial ecosystems and digital economy. Not only does it uncover ten pathways through which female entrepreneurship is influenced, but it also identifies more efficient driving pathways for female entrepreneurship. This contributes to unveiling the “black box” of how elements of the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem impact female entrepreneurial activity.

Second, this study introduces a comprehensive theoretical framework of the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem for analyzing female entrepreneurial activity. This study incorporated digital economy into the entrepreneurial ecosystem and analyzed female entrepreneurial activity from a digital entrepreneurial ecosystem perspective. Furthermore, it researches the influence of female entrepreneurship. This comprehensive analytical framework aids in delving deeper into the macroscopic contexts affecting the female entrepreneurial activity level. This study integrated the context of digital economy to investigate the multidimensional influencing factors of female entrepreneurial activity. This study advances the theoretical understanding of female entrepreneurial activity enhancement, providing insights and references for subsequent research and relevant policy considerations.

Third, this study employed the QCA method to uncover the asymmetry in the causal mechanisms driving the female entrepreneurial activity. The pathways leading to high female entrepreneurial activity were not necessarily the opposite of those leading to low activity. In other words, the reasons for high activity cannot be directly deduced from the opposite side of the reasons for low activity. This finding better explains the differential entrepreneurial activity among efficiency-driven countries and the configurational effects of mutual interdependencies between conditions.

Managerial implications

To effectively enhance the vibrancy of women’s entrepreneurship, the primary objective is to promote the establishment and reinforcement of social norms. High-level social norms not only directly influence the entrepreneurial perceptions of female entrepreneurs but also exert profound effects on other elements within the digital entrepreneurship ecosystem. Consequently, policymakers and social organizations should actively engage in campaigns centered on women’s entrepreneurship, aimed at shaping positive public discourse and enhancing societal recognition of female entrepreneurs. Specifically, various media platforms and social networks should be harnessed to disseminate the stories of successful women entrepreneurs. This could involve the production of documentaries and short videos that authentically portray the experiences and challenges faced by women who have achieved significant success in their respective fields. Such an approach not only serves to inspire potential entrepreneurs but also assists the public in reevaluating the value and potential of women in the entrepreneurial landscape. Moreover, through the interactive nature of social media, the public should be encouraged to share their personal experiences and success stories, thereby fostering a virtuous cycle that raises awareness of the importance of women’s entrepreneurship. Simultaneously, businesses and community organizations should be incentivized to establish reward mechanisms to recognize individuals and institutions that actively support women’s entrepreneurial endeavors. These rewards could encompass financial grants, resource support, and public acknowledgment, all aimed at motivating more enterprises to participate in initiatives that bolster women’s entrepreneurship.By strengthening these social norms, a more conducive entrepreneurial environment for women will be created, enabling them to access greater.

To further enhance the dynamism of women’s entrepreneurship, the establishment of a comprehensive support system is of paramount importance. This system should encompass critical elements such as market conditions, government policies, and human capital, thereby offering holistic support to female entrepreneurs. Research indicates that the synergistic effects of social norms, government policies, and human capital can significantly invigorate women’s entrepreneurial potential. Positive social recognition and supportive policies can elevate women’s willingness to embark on entrepreneurial ventures, while high levels of human capital provide them with a competitive advantage. In this context, educational institutions should bolster their collaboration with businesses to provide more targeted training and internship opportunities for women, enhancing their market competitiveness. These training programs could cover essential topics such as business plan development, market analysis, financial management, and digital marketing, equipping women with the requisite skills and knowledge for successful entrepreneurship. Additionally, organizing regular entrepreneurial salons and experience-sharing sessions can create platforms for female entrepreneurs to engage in dialog and learning, thereby stimulating their innovative thinking and collaborative spirit. Through the concerted efforts of government entities, financial institutions, and educational organizations, the creation of a comprehensive support system will greatly promote women’s entrepreneurial capabilities and aspirations. This system will not only offer the necessary resources and information but also cultivate a supportive societal atmosphere that encourages more women to boldly pursue their entrepreneurial dreams.

Female entrepreneurs should actively embrace the trends of the digital economy, leveraging digital technologies to enhance their entrepreneurial activity and market competitiveness. In today’s rapidly evolving digital landscape, women entrepreneurs face unprecedented opportunities and challenges. By utilizing digital platforms, they can expand their business reach and integrate resources, thereby enhancing their competitive edge. For instance, social media platforms enable female entrepreneurs not only to promote their brands but also to engage directly with target customers, thus bolstering brand awareness and customer loyalty. Furthermore, establishing online sales channels is a crucial step in the digital transformation process. Through e-commerce platforms, women entrepreneurs can efficiently reach a broad customer base, diversify their sales channels, and reduce operational costs. These platforms also offer data analysis tools that can provide insights into consumer behavior, allowing entrepreneurs to refine product positioning and market strategies, ultimately enhancing sales performance. Through their active participation in the digital economy, women entrepreneurs can expand their market reach while simultaneously boosting their innovative capabilities, thereby promoting the overall dynamism of women’s entrepreneurship.

Limitations

This study initially examines the key factors influencing female entrepreneurial activity within the digital entrepreneurship ecosystem. However, the analysis of antecedent variables is constrained by limitations in the number and specificity of case studies. It does not fully account for micro-level cognitive factors, such as entrepreneurial willingness, intentions, and fear of failure, that could significantly affect female entrepreneurial activity. Therefore, future research should expand its scope to explore these cognitive factors in greater depth. Specifically, incorporating psychological variables like self-efficacy, risk tolerance, self-recognition, and emotional regulation will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics shaping women’s entrepreneurial decisions and behaviors.

In terms of research methodology, this study utilizes fsQCA, which combines both qualitative and quantitative approaches, enabling a detailed analysis of the interactions between antecedent conditions. This is well-suited to the multifaceted nature of women’s entrepreneurial activity. However, the current study focuses primarily on the static impact of various factors on female entrepreneurial activity (FEA), without considering how these factors evolve over time. Therefore, future research could benefit from incorporating temporal elements by using time-ordered QCA. This would allow for the examination of stable configurations related to high and low levels of women’s entrepreneurial activity over time, shedding light on the factors driving fluctuations in entrepreneurship. Such an approach would provide richer empirical evidence to support policy development and theoretical advancement.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the present study are available from the Corresponding author upon reasonable request or openly available from Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) 2022 and the 2018 Global Digital Economy Development Index Report.

References

Abootorabi H, Wiklund J, Johnson AR, Miller CD (2021) A holistic approach to the evolution of an entrepreneurial ecosystem: an exploratory study of academic spin-offs. J Bus Ventur 36:106143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106143

Agarwal S, Ramadani V, Dana LP, Agrawal V, Dixit JK (2022) Assessment of the significance of factors affecting the growth of women entrepreneurs: study based on experience categorization. J Entrep Emerg Econ 14:111–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-08-2020-0313

Ajiva OA, Ejike OG, Abhulimen AO (2024) Empowering female entrepreneurs in the creative sector: overcoming barriers and strategies for long-term success. Int J Adv Econ 6:424–436. https://doi.org/10.51594/ijae.v6i8.1485

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Alecchi BEA, Radović-Marković M (2016) Women and entrepreneurship: female durability, persistence and intuition at work. Routledge

Alhajri A, Aloud M (2024) Female digital entrepreneurship: a structured literature review. Int J Entrep Behav Res 30:369–397. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-09-2022-0790

Aloulou WJ, Shatila K, Ramadani V (2024) The impact of empowerment on women entrepreneurial intention in Lebanon: the mediating effect of work–life balance. FIIB Bus Rev 23197145241241402. https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145241241402

Alvarez SA, Barney JB, Anderson P (2013) Forming and exploiting opportunities: the implications of discovery and creation processes for entrepreneurial and organizational research. Organ Sci 24:301–317. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0727

Angulo-Guerrero MJ, Bárcena-Martín E, Medina-Claros S, Pérez-Moreno S (2024) Labor market regulation and gendered entrepreneurship: a cross-national perspective. Small Bus Econ 62:687–706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-023-00776-0

Atarah BA, Finotto V, Nolan E, van Stel A (2023) Entrepreneurship as emancipation: a process framework for female entrepreneurs in resource-constrained environments. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 30:734–758. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-05-2022-0243

Avnimelech G, Rechter E (2023) How and why accelerators enhance female entrepreneurship. Res Policy 52:104669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104669

Becker GS (2009) Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Univ Chicago Press

Belitski M, Korosteleva J, Piscitello L (2023) Digital affordances and entrepreneurial dynamics: new evidence from European regions. Technovation 119:102442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2021.102442

Beynon MJ, Jones P, Pickernell D (2018) Entrepreneurial climate and self-perceptions about entrepreneurship: a country comparison using fsQCA with dual outcomes. J Bus Res 89:418–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.014

Bosse DA, Taylor IIIPL (2012) The second glass ceiling impedes women entrepreneurs. J Appl Manag Entrep 17(1):52–68

Brush CG (2008) Women entrepreneurs: a research overview. The Oxford handbook of entrepreneurship. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199546992.003.0023

Brush C, Edelman LF, Manolova T, Welter F(2019) A gendered look at entrepreneurship ecosystems Small Bus Econ 53:393–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9992-9

Bui HT, Kuan A, Chu TT (2018) Female entrepreneurship in patriarchal society: motivation and challenges. J Small Bus Entrep 30:325–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2018.1435841

Candeias JC, Sarkar S (2024) Entrepreneurial ecosystems policy formulation: a conceptual framework. Acad Manag Perspect 38:77–105. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2022.0047

Canning D, Pedroni P (2008) Infrastructure, long-run economic growth and causality tests for cointegrated panels. Manchester Sch 76:504–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9957.2008.01073.x

Carter S, Mwaura S, Ram M, Trehan K, Jones T (2015) Barriers to ethnic minority and women’s enterprise: existing evidence, policy tensions and unsettled questions. Int Small Bus J 33:49–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242614556823

Cetindamar D, Gupta VK, Karadeniz EE, Egrican N (2012) What the numbers tell: the impact of human, family and financial capital on women and men’s entry into entrepreneurship in Turkey. Entrep Reg Dev 24:29–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2012.637348

Charles R (2008) Redesigning social inquiry: fuzzy sets and beyond. University of Chicago Press Chicago

Dana LP, Nziku DM, Palalić R, Ramadani V (2022) Women entrepreneurs in North Africa: historical frameworks, ecosystems and new perspectives for the region. World Sci. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789811236617

Dehghanpour Farashah A (2013) The process of impact of entrepreneurship education and training on entrepreneurship perception and intention: study of educational system of Iran. Educ Train 55:868–885. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-04-2013-0053

del Olmo-García F, Crecente-Romero FJ, del Val-Núñez MT, Sarabia-Alegría M (2023) Entrepreneurial activity in an environment of digital transformation: an analysis of relevant factors in the euro area. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02270-0

Deng W, Orbes I, Ma P (2024) Necessity-and opportunity-based female entrepreneurship across countries: the configurational impact of country-level institutions. J Int Manag 101160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2024.101160

Dheer RJ, Li M, Treviño LJ (2019) An integrative approach to the gender gap in entrepreneurship across nations. J World Bus 54:101004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2019.101004

Dul J, Van der Laan E, Kuik R (2020) A statistical significance test for necessary condition analysis. Organ Res Methods 23:385–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118795272

Dul J (2016) Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA): logic and methodology of “Necessary but Not Sufficient” causality. Organ Res Methods 19(1):10–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115584005

Díez-Martín F, Blanco-González A, Prado-Román C(2016) Explaining nation-wide differences in entrepreneurial activity: a legitimacy perspective Int Entrep Manag J 12:1079–1102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-015-0381-4

Elia G, Margherita A, Passiante G (2020) Digital entrepreneurship ecosystem: how digital technologies and collective intelligence are reshaping the entrepreneurial process. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 150:119791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119791

Epure M, Martin-Sanchez V, Aparicio S, Urbano D (2024) Human capital, institutions, and ambitious entrepreneurship during good times and two crises. Strateg Entrep J 18:414–447. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1492

Ester P, Román A (2017) A generational approach to female entrepreneurship in Europe. J Women’s Entrep Educ 2017:3–4

Fauzi MA, Sapuan NM, Zainudin NM (2023) Women and female entrepreneurship: past, present, and future trends in developing countries. Entrep Bus Econ Rev 11:57–75

Fiss PC (2011) Building better causal theories: a fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad Manag J 54:393–420. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.60263120

Garg S, Gupta S, Mallick S (2024) Financial access and entrepreneurship by gender: evidence from rural India. Small Bus Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-024-00925-z

Grootaert C, Van Bastelaer T (2001) Understanding and measuring social capital: a synthesis of findings and recommendations from the social capital initiative. World Bank, Social Development Family, Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Network, Washington, DC

Guerola-Navarro V, Gil-Gomez H, Oltra-Badenes R, Soto-Acosta P (2024) Customer relationship management and its impact on entrepreneurial marketing: a literature review. Int Entrep Manag J 20:507–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-022-00800-x

Haber S, Reichel A (2007) The cumulative nature of the entrepreneurial process: the contribution of human capital, planning and environment resources to small venture performance. J Bus Venturing 22:119–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.09.005

Hamid N, Khalid F (2016) Entrepreneurship and innovation in the digital economy. Lahore J Econ 21:273–312

Hassan S, Poon WC, Hussain IA (2024) Heterogeneous social capital influencing entrepreneurial intention among female business students in the Maldives. J Entrep Emerg Econ 16:209–230. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-01-2023-0024

Hechavarría DM, Ingram AE (2019) Entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions and gendered national-level entrepreneurial activity: a 14-year panel study of GEM. Small Bus Econ 53:431–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9994-7

Huang Y, Li S, Xiang X, Bu Y, Guo Y (2022a) How can the combination of entrepreneurship policies activate regional innovation capability? A comparative study of Chinese provinces based on fsQCA. J Innov Knowl 7:100227

Huang Y, Zhang M, Wang J, Li P, Li K (2022b) Psychological cognition and women’s entrepreneurship: a country-based comparison using fsQCA. J Innov Knowl 7:100223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100223

Huang Y, Zhang J, Xu Y, Sun S, Bu Y, Li S, Chen Y (2024) College students’ entrepreneurship policy, regional entrepreneurship spirit, and entrepreneurial decision-making. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03242-8

Jamali D (2009) Constraints and opportunities facing women entrepreneurs in developing countries: a relational perspective. Gender Manag Int J 24:232–251. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542410910961532

Johnson AG, Mehta B (2024) Fostering the inclusion of women as entrepreneurs in the sharing economy through collaboration: a commons approach using the institutional analysis and development framework. J Sustain Tour 32:560–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2091582

Kamberidou I(2020) “Distinguished” women entrepreneurs in the digital economy and the multitasking whirlpool. J Innov Entrep 9:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-020-0114-y

Karaki FJ (2021) Mapping Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (EE) of Palestine. J Entrep Bus Econ 9(2):174–217

Karim S, Kwong C, Shrivastava M, Tamvada JP (2023) My mother-in-law does not like it: resources, social norms, and entrepreneurial intentions of women in an emerging economy. Small Bus Econ 60:409–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00594-2

Khodor S, Aránega AY, Ramadani V (2024) Impact of digitalization and innovation in women’s entrepreneurial orientation on sustainable start-up intention. Sustain Technol Entrep 3:100078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stae.2024.100078

Kling R, Lamb R (1999) IT and organizational change in digital economies: a socio-technical approach. ACM SIGCAS Comput Soc 29:17–25

Kong H, Kim H (2022) Does national gender equality matter? Gender difference in the relationship between entrepreneurial human capital and entrepreneurial intention. Sustainability 14:928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020928

Kousar S, Ahmed F, Afzal M, Segovia JE (2023) Is government spending in the education and health sector necessary for human capital development? Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01514-3

Kraus S, Ribeiro-Soriano D, Schüssler M (2018) Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) in entrepreneurship and innovation research – the rise of a method. Int Entrep Manag J 14:15–33

Kumar RK, Pasumarti SS, Figueiredo RJ, Singh R, Rana S, Kumar K, Kumar P (2024) Innovation dynamics within the entrepreneurial ecosystem: a content analysis-based literature review. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02817-9

Marquardt L, Harima A (2024) Digital boundary spanning in the evolution of entrepreneurial ecosystems: a dynamic capabilities perspective. J Bus Res 182:114762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114762

Menzies J, Chavan M, Jack R, Scarparo S, Chirico F (2024) Australian indigenous female entrepreneurs: the role of adversity quotient. J Bus Res 175:114558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114558

Meyer N (2018) Research on female entrepreneurship: are we doing enough? Pol J Manag Stud 17:158–169. https://doi.org/10.17512/PJMS.2018.17.2.14

Mirjana RM (2022) Women entrepreneurs’ resilience in times of COVID-19 and afterwards. J Entrep Bus Resilience 5:25–30

Mueller SL, Thomas AS (2001) Culture and entrepreneurial potential: a nine-country study of locus of control and innovativeness. J Bus Venturing 16:51–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00039-7

Nambisan S (2017) Digital entrepreneurship: toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Pract 41:1029–1055. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12254

Nyakudya FW, Mickiewicz T, Theodorakopoulos N (2024) The moderating role of individual and social resources in gender effect on entrepreneurial growth aspirations. Int Entrep Behav Res 30:1576–1599. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-05-2023-0519

Odeyemi O, Oyewole AT, Adeoye OB, Ofodile OC, Addy WA, Okoye CC, Ololade YJ (2024) Entrepreneurship in Africa: a review of growth and challenges. Int J Manag Entrep Res 6:608–622. https://doi.org/10.51594/ijmer.v6i3.874

Ojong N, Simba A, Dana LP (2021) Female entrepreneurship in Africa: a review, trends, and future research directions. J Bus Res 132:233–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.032

Ozaralli N, Rivenburgh NK (2016) Entrepreneurial intention: antecedents to entrepreneurial behavior in the USA and Turkey. J Glob Entrep Res 6:1–32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-016-0047-x

Patrício LD, Ferreira JJ (2024) Unlocking the connection between education, entrepreneurial mindset, and social values in entrepreneurial activity development. Rev Manag Sci 18:991–1013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-023-00629-w

Petridou E, Johansson R, Eriksson K, Alirani G, Zahariadis N (2024) Theorizing reactive policy entrepreneurship: a case study of Swedish local emergency management. Policy Stud J 52:73–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12508

Piñeiro-Chousa J, López-Cabarcos MÁ, Romero-Castro NM, Pérez-Pico AM (2020) Innovation, entrepreneurship and knowledge in the business scientific field: mapping the research front. J Bus Res 115:475–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.045

Piñeiro-Chousa J, López-Cabarcos MÁ, Pérez-Pico AM, Caby J (2023) The influence of Twitch and sustainability on the stock returns of video game companies: before and after COVID-19. J Bus Res 157:113620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113620

Preisendörfer P, Voss T (1990) Organizational mortality of small firms: the effects of entrepreneurial age and human capital. Organ Stud 11:107–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084069001100109

Pérez-Morote R, Pontones-Rosa C, Alonso-Carrillo I et al. (2024) Men’s and women’s visions of employment policies to combat depopulation in rural Spain. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:1417. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03918-1

Radović–Marković M, Đukanović B, Marković D, Dragojević A (2021) Entrepreneurship and work in the gig economy: the case of the Western Balkans. Routledge

Ragin CC (2006) Set relations in social research: evaluating their consistency and coverage. Polit Anal 14:291–310. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpj019

Salamzadeh A, Ramadani V (2021) Entrepreneurial ecosystem and female digital entrepreneurship–lessons to learn from an Iranian case study. In: Ramadani V, Palalić R, Dana LP (eds) The Emerald Handbook of Women and Entrepreneurship in Developing Economies. Emerald Publishing Limited, pp 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80071-326-020211016

Salamzadeh A, Radović-Marković M, Ghiat B (2022) Women Entrepreneurs in Algeria. In: Dana LP, Palalić R, Ramadani V (eds) Women Entrepreneurs in North Africa Historical Frameworks, Ecosystems and New Perspectives for the Region. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., pp 87–102

Salamzadeh A, Dana LP, Ghaffari Feyzabadi J, Hadizadeh M, Eslahi Fatmesari H (2024) Digital technology as a disentangling force for women entrepreneurs. World 5:346–364. https://doi.org/10.3390/world5020019

Schultz TW (1961) Investment in human capital. Am Econ Rev 51:1–17

Sebola MP (2023) South Africa’s public higher education institutions, university research outputs, and contribution to national human capital. Hum Resour Dev Int 26:217–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2022.2047147

Sevilla-Bernardo J, Herrador-Alcaide TC, Sanchez-Robles B (2024) Successful entrepreneurship, higher education and society: from business practice to academia. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03916-3

Shepherd DA, Douglas EJ, Shanley M (2000) New venture survival: ignorance, external shocks, and risk reduction strategies. J Bus Ventur 15:393–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00032-9

Sobhan N, Hassan A (2024) The effect of institutional environment on entrepreneurship in emerging economies: female entrepreneurs in Bangladesh. J Entrep Emerg Econ 16:12–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-01-2023-0028

Song AK (2019) The digital entrepreneurial ecosystem—a critique and reconfiguration. Small Bus Econ 53:569–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00232-y

Stokes D, Wilson N (2010) Small business management and entrepreneurship. Cengage Learning EMEA

Sussan F, Acs ZJ (2017) The digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Bus Econ 49:55–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9867-5

Tan N, Fang J, Li X (2024) Digital finance, cultural capital, and entrepreneurial entry. Finance Res Lett 62:105109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.105109

Tavakol N (2018) The effect of changes (time, profession, etc.) on the position of women entrepreneur. Curr Trends Organ Perform Fut Perspect 294–306

Thébaud S (2015) Business as plan B: institutional foundations of gender inequality in entrepreneurship across 24 industrialized countries. Adm Sci Q 60:671–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839215591627

Venkatesh V, Shaw JD, Sykes TA, Wamba SF, Macharia M (2017) Networks, technology, and entrepreneurship: a field quasi-experiment among women in rural India. Acad Manag J 60:1709–1740. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.0849

Welsh DH, Kaciak E, Fadairo M, Doshi V, Lanchimba C (2023) How to erase gender differences in entrepreneurial success? Look at the ecosystem. J Bus Res 154:113320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113320

Woolley JL (2014) The creation and configuration of infrastructure for entrepreneurship in emerging domains of activity. Entrep Theory Pract 38:721–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12017

Wu J, Li Y, Zhang D (2019) Identifying women’s entrepreneurial barriers and empowering female entrepreneurship worldwide: a fuzzy-set QCA approach. Int Entrep Manag J 15:905–928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-019-00570-z