Abstract

National images today are shaped not only by state-led narratives but also through daily interactions on social networking sites, where passive consumption and active expression converge to influence public perceptions. This study investigates how message reception and expression affect Chinese audiences’ image of Japan. We examine how cognitive responses mediate the influence of SNS engagement on behavioral intentions by integrating a communication mediation framework with the bidirectional message effects model. Our findings indicate a dichotomy: while message reception fosters a positive evaluation of Japan, message expression elicits skepticism and cautious intentions toward Japan. It is thus imperative to expand beyond reception-oriented models to encompass the reciprocal nature of online communication, contesting the prevailing perspective that excessively highlights the role of digital communication in augmenting soft power. The study’s implications are noteworthy for digital and public diplomacy endeavors, suggesting practitioners should consider the interaction between passive and active engagement on SNS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social networking sites (SNS) are web-based platforms that enable individuals to generate personal profiles and share connections within a bounded system (Boyd and Ellison, 2007). SNSs have surged in popularity over the past decade, particularly with WeChat and Weibo being among China’s most frequently used platforms. WeChat alone accounted for ~13.3 billion monthly active users as of the second quarter of 2023, while Weibo accounted for 599 million monthly active users, according to the interim financial report. This surge in popularity has opened up new avenues for youth engagement, allowing for the articulation of thoughts and participation in political discourse. This trend fosters an in-depth exploration into soft power and nation branding, two intertwined methods employed by states for global projection. As defined by Joseph Nye (1990, 2004), soft power denotes a nation’s ability to shape the preferences of others through appeal and attraction, as opposed to coercion or force. Nation branding—a related concept—entails strategic promotion of a country’s image through public diplomacy, aiming to project positive images to international audiences (Anholt, 2006). Given this, social media platforms have developed into key instruments for nations to interact with foreign audiences, and disseminate narratives that reflect national identity and values, contributing to the construction of national images (Dinnie, 2015; Castells, 2008). Yet, despite the capability to serve as a vehicle for state-led branding initiatives, SNSs facilitate individual-driven discourse, empowering individuals to engage in the construction of national images, transcending their role as mere passive recipients. This reciprocal influence, wherein both message reception and expression influence public attitudes and behaviors towards a nation. SNSs thus serve as arenas for both state narratives and public discourse, enabling individuals to amplify or counteract official messaging.

This is particularly relevant in discussions on national image construction, as researchers have increasingly examined how SNS usage affects public opinion and international images from an interdisciplinary perspective. A nation’s strategic capital can be fortified through the cultivation of its national image (Whalley and Weisbrod, 2012), which can serve as an invaluable instrument for foreign policy (Cappelletti, 2019). Japan provides a compelling case study of a country that has long recognized the importance of soft power and nation branding. Since the 1920s and 1930s, Japan started leveraging its culture and media to improve its international reputation, well before the term “soft power” emerged (Sato, 2012). Its soft power assets, including its popular culture exports and constitutional rejection of military aggression, have made it an attractive player on the global stage (McConnell, 2008). Japan’s efforts to brand itself as a peaceful and culturally rich nation are integral to its soft power strategy and SNS platforms play a significant role in promoting these narratives. However, Japan’s efforts have been hindered by territorial disputes and historical memory, which have impacted Japan’s relations with other Asian countries (Lam, 2007; Iwabuchi, 2015). Despite its efforts, Japan has not been able to shake its image as an insular society (McConnell, 2008). In response, the Japanese government’s soft power campaign aims to project a positive image of the country and promote mutual understanding and trust with key targets (MOFA, 2022), including China as a prominent one. This is especially relevant given the recent decline in China’s perception of Japan since 2015, which has been attributed to tensions over territorial disputes, the Prime Minister’s visit to Yasukuni Shrine, and history textbook controversies. This decline has been extensively discussed among scholars (e.g., Burcu, 2022; Vekasi and Nam, 2019; Gries et al. 2016).

Research into the effects of SNS on national image construction has shown an increase in interdisciplinary efforts. However, the lack of an analytical framework has resulted in mainly descriptive research. Studies have demonstrated that SNS usage contributes to the negative images of Japan among the Chinese public, allowing individuals to express and amplify anti-Japanese sentiment during times of heightened tension (Hyun et al. 2014). This shift has marked a significant change from ‘state-led’ to ‘society-driven’ anti-Japanese sentiment, enabling individuals to have a greater influence on authority agendas through the use of Web 2.0 technology (Cui, 2012). SNSs have played an unprecedented role in disseminating information that facilitates the gathering of participants and is providing a public sphere for users to engage in social events and express their opinions on debated issues. A better understanding of how online communicative behavior contributes to a nation’s international image would facilitate the development of more effective interventions that encourage specific desirable attitudes and behaviors. However, the role of the user in the content generation process and the expression effects of the bidirectional trait have received little attention. Expression effects involve the impact of producing and sharing content on users’ attitudes and perceptions. Meanwhile, the bidirectional trait pertains to the interactive nature of SNS communication, wherein users are not only recipients of content but also active producers and disseminators. This dual role allows users to influence the flow of information and, consequently, the construction of national images in a dynamic and reciprocal manner. Although studies have examined the reception effects of media use on national images (Jiang, 2013, 2014; Li, 2006), there is a lack of research on how communicative behavior contributes to the construction of national images. As of yet, there is no established mechanism for how this process occurs. Therefore, this study aims to investigate how communicative behaviors on SNS affect the perception of Japan by the Chinese public. It also seeks to provide insights into the extent to which nationalist sentiments impede the cultivation of a positive image in China. A comprehensive understanding of the mechanism of SNS communication is essential in promoting positive attitudes and behaviors between Japan and China at the civil level.

Extensive research on online communication and international public relations has highlighted a lack of consensus on the subject, both theoretically and empirically. While existing research has explored the reception effects of SNS use on national images (Jiang, 2013, 2014; Li, 2006), there remains a gap in understanding how communicative behavior—both receiving and expressing—on SNS contributes to the construction of national images. To understand the impact of online communication on international public relations, the expression-effect perspective is crucial (Pingree, 2007; Valkenburg et al., 2016; Valkenburg, 2017). This study integrates recent theorizing based on the O–S–R–O–R model (orientations–stimulus–reasoning–orientation–response; Shah et al. 2007; Cho et al. 2009) and the bidirectional message effects model (Pingree, 2007), which presumes mediating roles for online expression and cognition in explaining the relationship between reception and behavioral responses. The proposed theoretical model suggests mediated cause–effect relationships between communication and outcomes and highlights both the direct and indirect effects of SNS use. A comprehensive understanding of this mechanism is essential in promoting positive attitudes and behaviors between Japan and China at the civil level.

Theoretical background

As early as the beginning of the 21st century, the boundaries between content recipients and producers have blurred, especially with the rise of Web 2.0 technologies (Gillmor, 2006; McQuail and Windahl, 2015; Lüders, 2008). This dynamic communication process is especially relevant in the context of SNS, where individuals frequently switch between consuming and producing content (Valkenburg et al. 2016). To explore this dynamic, this study adopts a framework that integrates several key models from communication theory to understand how exposure to Japan-related messages on SNS shapes both cognitive and behavioral outcomes.

Bidirectional message effects model: integrating expression and reception in analyzing cognitive-behavioral outcomes

The bidirectional message effects model (BMEM), proposed by Pingree (2007), stems from self-perception theory (SPT; Bem, 1967, 1972), which posits that individuals infer their attitudes and beliefs from their own behavior. According to this model, communication via SNS is not a one-way process where users are passively influenced by what they consume. Instead, the expression itself has a feedback effect on the sender. For instance, when individuals express messages about Japan, whether through sharing posts or commenting on content, their attitudes, cognitions, and behaviors toward Japan can change as a result of the act of expression. This model highlights the recursive nature of SNS communication, where message production impacts both recipients and the sender themselves, thus supporting a dual pathway of influence. BMEM challenges traditional models of media effects that focus predominantly on the impact of reception. Instead, it suggests that the sender, through message production, experiences changes in their own attitudes or beliefs. This is relevant for understanding how engagements with Japan-related messages on SNS may alter perceptions of Japan, not only for receivers but for the message senders themselves. By highlighting the expression effect, this model complements cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1962) by emphasizing behavioral influence on attitudes.

Communication mediation model: linking SNS communication to cognitive characteristics and behaviors

Over the past decade, there has been a renewed interest in the relationship between digital media use and national image. Previous research has examined how exposure to social media affects cognitive traits like impression or perception, though the results remain inconclusive so far. While some studies have indicated that social media use has no correlation with one’s image of Japan in China (Jiang, 2014), others have found modest reception effects (Turcotte et al. 2015; Li, 2006). The communication mediation model (CMM; Cho et al. 2009; Shah et al. 2017) further enriches the understanding of SNS communication by positing that media exposure influences cognitive and behavioral outcomes through post-exposure communicative processes. It proposes that after individuals receive media messages, they engage in further cognitive and communicative activities (e.g., discussing or sharing messages), which in turn mediate the effect of message reception on behavioral outcomes. This model is particularly relevant for studying the influence of SNS communication on national image. After being exposed to Japan-related messages, individuals engage in cognitive activities such as discussing or reflecting on the content, which can mediate the impact of media exposure on subsequent behaviors, including travel intentions or economic interactions.

Recent studies offer compelling evidence that online communication has a significant impact on an individual’s attitudes and actions. Scholars view expression, independent from reception, as a critical factor in communication processes. Notably, Pingree (2007) and Shah (2016) have highlighted the complementary effects of expression and reception in shaping cognitive outcomes. In this context, expression does not merely reinforce received messages but can also alter or strengthen attitudes. This dual perspective leads us to the idea that cross-cutting exposure—where individuals encounter messages from multiple perspectives—often includes a feedback loop. Expression, in turn, influences the cognitive processes involved in how individuals perceive and respond to information (Pingree, 2007). Such a viewpoint sheds light on how online communication shapes both cognitions and behaviors. Furthermore, research shows that the joint process of consuming and sharing relevant information influences cognitive characteristics, which, in turn, could shape behaviors (Yoo et al. 2016). The mediation of cognitive characteristics between communication and behavioral outcomes has been supported by numerous studies (Mutz, 2006; Pingree, 2007; Valkenburg et al. 2016; Valkenburg, 2017). For instance, Lu et al. (2022) investigated the indirect influence of social media news consumption on political consumerism, such as boycotting and buycotting, during the US–China trade dispute. They found that the influence is mediated through the expression of opinions and supportive attitudes toward tariffs on China. These results emphasize that expressing messages is as crucial as receiving them in shaping opinions and behaviors. The research compiled demonstrates that engaging with Japan-related content on SNS, whether by receiving or sharing messages, can either fortify or diminish users’ cognitive and behavioral responses. The cognitive characteristics influenced by SNS exposure (e.g., recognition, evaluation, and impression of Japan) are hypothesized to be mediated by the impact of post-exposure communication on behavioral responses. This provides a critical framework for understanding how digital media contributes to nation branding and public diplomacy efforts.

However, it is essential to recognize that cross-national media exposure may yield dual effects. On the positive side, such exposure often fosters pro-social attitudes, including enhanced cultural engagement and support for diplomatic initiatives. Research by Cull (2009) and Hayden (2012) demonstrates that foreign media can raise awareness of a country’s contributions, thereby promoting favorable perceptions and encouraging international collaboration. Conversely, media exposure can also amplify security concerns. Studies on public diplomacy and international relations suggest that increased media focus on geopolitical tensions and military activities may heighten perceived threats, potentially leading to more cautious or adversarial responses towards the involved nation. We, therefore, hypothesize the following:

H1: Receiving Japan-related information via SNS positively causally influences cognitive responses, such as greater recognition of Japan’s cultural and economic contributions, and also leads to more favorable behavioral intentions, such as willingness to visit Japan or engage in interactions with Japanese individuals.

H2: Expressing Japan-related information via SNS leads to more favorable evaluations of Japan’s image and stronger behavioral intentions, including increased support for diplomatic relations and a higher likelihood of visiting Japan.

Mediating roles of cognitive characteristics: evaluation, recognition, and impression

Theoretical perspectives on media effects have long recognized that most influences are indirect, mediated through various cognitive and affective processes (e.g., Petty and Cacioppo, 1986). The present study investigates the four scales of image composition: recognition, evaluation, impression, and behavioral intentions, as defined in social psychology (Midooka et al. 1990). In exploring the relationship between SNS communication and behavioral outcomes, the current study emphasizes the mediating role of three key cognitive characteristics. These cognitive dimensions not only reflect an individual’s immediate reaction to Japan-related messages but also shape their subsequent behaviors, such as travel intentions or social and economic interactions with Japan. The evaluation of Japan refers to a subjective assessment or judgment, often measured through semantic differential (SD) scales assessing favorability or unfavourability (Jiang, 2013). The recognition of Japan, meanwhile, concerns cognitive awareness or knowledge of Japan’s culture, politics, and economic contributions. Finally, impression reflects the emotional response and affective associations that individuals hold toward Japan, which are formed through both direct exposure to Japan-related content and interpersonal communication.

These three characteristics—evaluation, recognition, and impression—are central to the mediation process within the extended O–S–R–O–R model (Shah et al. 2007; Cho et al. 2009), which builds on the traditional S–O–R model (Markus and Zajonc, 1985). This model posits that after initial exposure to media stimuli (e.g., Japan-related content), individuals engage in reasoning, a critical mediating process that influences their cognitive characteristics (the second ‘O’) and ultimately affects their behavioral responses (the second ‘R’). The O–S–R–O–R model emphasizes the role of cognitive processing in transforming media stimuli into meaningful cognitive outcomes. In this study, the O–S–R–O–R model is adapted to explain how receiving and expressing Japan-related information via SNS influences Chinese university students’ perceptions of Japan. Exposure to Japan-related messages (the stimulus) triggers cognitive processing, which manifests as changes in evaluation, recognition, and impression of Japan. These cognitive changes, in turn, mediate the effect of SNS communication on behavioral outcomes, such as individuals’ intentions to travel to Japan or engage in economic activities related to Japan.

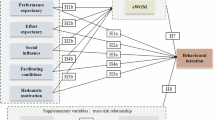

Furthermore, the framework incorporates the expression effects proposed by Pingree’s bidirectional message effects model (BMEM), which suggests that message production (e.g., commenting or sharing Japan-related posts) influences not only the recipients but also the message producers themselves (Pingree, 2007). Thus, SNS communication is a bidirectional process where both receiving and producing messages play a role in shaping users’ cognitive and behavioral responses. A mediating model that incorporates the bidirectional effects of SNS communication and a framework of mediation communication has been advanced, as shown in Fig. 1. This model examines the perceptions of Japan among Chinese university students, with a focus on the expression effects of SNS communication, leveraging Web 2.0 technology attributes and underlying theoretical frameworks. It considers demographics (age, gender, origin, and annual household income) as potential predictors of SNS communication, thereby outlining the structural propositions of the audience, identified as the initial ‘O’. Adapting Pingree’s (2007) model, the framework delineates the message exchange process, denoted as the S–R portion, focusing on the reception and expression of relevant messages. This study posits a correlation, rather than causality, between reception and expression, following Shao’s (2009) suggestion that active participation may boost reception activities like commenting, rating, or sharing. Hence, this research posits a correlation between the reception and expression of content pertaining to Japan on SNSs.

Building on this integrated framework, the following hypotheses are proposed to examine the mediating roles of cognitive characteristics:

H3: Cognitive responses to Japan, including evaluation, recognition, and impression, positively lead to behavioral intentions.

H4: The effect of Japan-related information acquired via SNSs on individuals’ behavioral intentions is channeled by cognitive responses, encompassing progressiveness evaluation, perception of threat, and Japan’s overall impression.

H5: The dissemination of information related to Japan on SNSs influences behavioral intentions through cognitive responses, including progressiveness evaluation, perception of threat, and Japan’s overall impression.

Materials and methods

Procedure and participant

Undergraduate students were selected as participants due to their high education level and age, as the Statistical Report on Internet Development suggests that young, highly educated adults are the primary users of SNS. As a result, selecting university students for this study is deemed to be the most relevant for this study. Over a fortnight, spanning from 2 September to 15 September 2017, an anonymous survey was carried out at two national universities located in Beijing. The study received approval for human subject research. To ascertain the optimal sample size for the survey, a specific equation was utilized, which took into consideration the population and other statistical indices:

where

σ = standard error of the sample mean;

z = level of confidence of the estimate (in the case of 95% = 1.96);

ε = sampling error;

n = sample size.

The survey required a minimum of 385 respondents, and we used a multi-stage cluster sampling technique to recruit participants. We based the sampling frame on dormitory rooms. The household drop-off method was employed to distribute hard-copy questionnaires, which voluntary respondents completed and returned later. A total of 510 respondents were recruited, and 473 valid responses were included in the study. The questionnaire recovery rate and effective rate exceed 90%. The data collection methods suggest the sample is a representative cross-section of Beijing’s undergraduate student population. Demographic analysis (Table 1) revealed a mean age of 19.37 years (SD = 1.299, range = 17–23 years) among the respondents, with males constituting 38.5%. The sample’s geographic diversity aligns with the 2021 National Population Census of China, ensuring a varied respondent base.

Measures

The survey encompasses three primary components: demographic data, SNS communication practices, and images of Japan. All variables, except for demographic information, were assessed using a Likert scale with five points. Through confirmatory factor analysis on cognitive characteristics, a two-factor solution emerged: categorizing them into progressiveness evaluation and perceived threat. Below, we provide detailed descriptions of these variables.

Independent variables

Reception and expression of Japan-related messages

The measurement of engagement with Japan-related content on SNSs was derived from an approach outlined by Yoo et al. (2016). Respondents reported their exposure to content about Japan—ranging from comments and pictures to videos and other forms of information—across various platforms like Weibo, WeChat, QQ Zone, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram over the last 30 days (M = 2.87, SD = 1.18). Similarly, the frequency of message expression was assessed using the same scale. Respondents were instructed to retrospectively assess their involvement in Japan-related expression over the preceding 30 days, without reference to specific platforms. They rated how often they engage in expression on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often), with a mean of 2.06 and a standard deviation of 1.15.

Mediators and dependent variables

Evaluation, recognition, and impression of Japan

The study assessed the evaluation and recognition of Japan (ѱ = 0.40, p < 0.01) utilizing nine SD items on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items encompass: backward and advanced, dangerous and safe, impoverished and affluent, untrustworthy and trustworthy, culturally barren and culturally rich, gender-unequal and gender-equal, militant and peace-loving, conservative and open and free, and threatening and contributing. The scale development was verified by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the responses, resulting in the identification of two subcomponents, progressiveness (Cronbach’s α = 0.71) and perceived threat (Cronbach’s α = 0.78). The variable factor loadings exceeded 0.50. The respondents were instructed to rate their impression of Japan on a five-point scale, with 1 representing a very unfavorable impression and 5 representing a very favorable impression (M = 3.20, SD = 0.97).

Behavioral intentions towards Japan

A behavioral intentions measure was developed based on four elements derived from principal component analysis (PCA): vigilant intention, intimate intention, interest, and social distance. The following assertions were put on the respondents, asking them to rate their agreement: (1) ‘We should remain vigilant regarding Japan’ (M = 3.17, SD = 0.93); (2) ‘We should enhance cooperation and cultivate intimate relations with Japan in the future’ (M = 3.58, SD = 0.81); (3) ‘Japan piques my interest’ (M = 3.53, SD = 1.02); and (4) ‘I am inclined to reside or live in Japan’ (M = 3.00, SD = 1.18). A five-point scale (1 being strongly disagreed and 5 being strongly agreed; Cronbach’s α = 0.77) was used to record the responses.

Demographic variables

For control purposes, all endogenous variables were linked to the paths of the sociodemographic factors, which functioned as exogenous variables in the mediation model of this analysis. These demographic indicators represent the structural attributes of an individual. Respondents were questioned about their gender, age, and geographic origin in China. They were also requested to estimate their household income for 2017 on a scale of 1–6, where 1 represents <RMB 100,000 and 6 signifies more than RMB 180,000. The aforementioned information was gathered to control for the structural characteristics of the respondents and to elucidate the demographics of the respondents.

Results

This study begins by assessing the reliability and validity of the CFA model. Using Cronbach’s alpha (CA) coefficients, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) as primary indicators, the results confirm high-scale reliability with CA coefficients exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.7 (Field et al. 2012). Both latent variables demonstrated strong convergent validity of measurement, with CR and AVE values above 0.8 and 0.5, respectively. The measurement model’s reliability and validity were demonstrated. To test the overall hypothesized model (Fig. 1), a structural equation model (SEM) was performed using SPSS Amos after imputing missing data using the full conditional specification (FCS) method. This method is known to be less biased and more flexible with multilevel data (Audigier et al. 2018). The goodness-of-fit between the theorized model and the sample data was assessed with two types of fit indices: absolute indices and incremental indices (Bollen, 1987; Gerbing and Anderson, 1992; Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Model evaluation

As the most common absolute fit index, the χ2-distributed test (Hoyle and Panter, 1995) indicates that the fit of the data to the hypothesized model is not adequate, yielding a chi-square value of 329.7 with 90 degrees of freedom and a probability of <0.0001. However, the χ2-distributed statistic has its limitations and additional indices were utilized for a more comprehensive evaluation of the model fit. The comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler and Bonett, 1980) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI; Tucker and Lewis, 1973) were employed to assess the improvement in model fit compared to the baseline model (Byrne, 2010), while the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) were presented together to provide a better understanding of the model’s observed sample data (Browne and Cudeck, 1993). The results of the analysis indicated that the hypothesized model was a good fit for the sample data, with a χ2 of 156.518, p-value of 0.00, degree of freedom of 81, SRMR of 0.034, RMSEA of 0.046, CFI of 0.968, and GFI of 0.966. Based on these findings, it can be concluded that the model fits the data reasonably well.

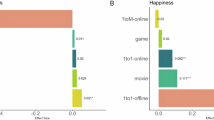

The direct effects of message reception and expression

Upon analysis of the hypothesized paths outlined in Fig. 2 and the interrelationships among communicative behaviors and three dimensions related to the image of Japan in the eyes of Chinese undergraduate students, Table 2 presents estimates of these results. The results support the notion that message reception and expression are positively correlated (r = 0.61, p < 0.001), as predicted in the theorized model, and support Shao’s (2009) work. In other words, respondents who frequently receive Japan-related information are more likely to produce Japan-related messages on SNS and vice versa. The direct effects of receiving Japan-related messages on SNS were also examined, and the data supports the H1 that receiving such information facilitates Chinese university students’ evaluation of Japan’s progressiveness (β = 0.184, p < 0.01) and impression of Japan (β = 0.225, p < 0.001). However, no significant effects on the perceived threat (β = 0.122, n.s.) were found. Additionally, while message reception has a positive direct effect on respondents’ interest in Japan (β = 0.179, p < 0.01), there was little total effect on vigilant intention (β = −0.079, n.s.), intimate intention (β = 0.092, n.s.), interest in Japan (β = 0.175, n.s.), or social distance to Japan (β = 0.113, n.s.). Thus, this study did not find support for the total effects of Chinese undergraduate students’ message reception on their behavioral intentions towards Japan.

Supporting H2, expressing Japan-related messages on SNS yielded a scant effect on the evaluation of Japan’s progressiveness (β = −0.173, p < 0.05). Those who posted about Japan more frequently exhibited lower levels of evaluation of Japan’s progressiveness. It is difficult to explain this result, but it might be related to the nature of the issues that users are inclined to post on SNS. Another theorized relationship between message expression and the perceived threat of Japan fell just short of the threshold of significance. Only intimate intention showed a significant positive effect, partially supporting H2 that sharing messages is associated with Chinese undergraduate students’ intimate intention towards Japan (β = 0.023, p < 0.10).

Supporting H3, the evaluation of Japan’s progressiveness has positive associations with behavioral intentions. Specifically, there is a strong link between the evaluation of progressiveness and vigilant intention (β = 0.632, p < 0.001), intimate intention (β = 0.472, p < 0.01), interest of Japan (β = 0.309, p < 0.001), and social distance (β = 0.200, p < 0.001). However, the perceived threat of Japan is positively associated with the vigilant intention (β = 0.778, p < 0.001), while negatively associated with social distance (β = −0.215, p < 0.10). The findings partially support H3. Nevertheless, the relationship between the evaluation of progressiveness and intimate intention (β = −0.109, n.s.) and interest in Japan (β = −0.077, n.s.) appears to leave relatively little to be explained. In this section, three hypotheses in terms of direct effects were tested. It is worth noting that most media effects are indirect rather than direct, as advocated by some theorists (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986). In order to comprehensively understand the processes and mechanisms of SNS communication, indirect effects have been taken into account in this study.

The indirect effects of message reception and expression

Table 3 presents estimates and critical values for a 95% confidence interval of the total indirect effects of message reception and expression on behavioral intentions. The study found that Japan-related message received through SNS produces positive total indirect effects on intimate intention (β = 0.125, p < 0.001), interest in Japan (β = 0.162, p < 0.001), and reduction in social distance from Japan (β = 0.131, p < 0.001). This suggests that compared to information that may provoke vigilant intention, users are more likely to consume the opposite of Japan-related information. In contrast, we found that Japan-related message expression has a positive total indirect effect on vigilant intention towards Japan (β = 0.166, p < 0.001) through outcome orientations, indicating that the more frequently individuals produce Japan-related messages on SNS, the more likely they intend to be vigilant towards Japan. These findings confirmed that the expression effects channeled by cognitive characteristics are positively linked with vigilant intention only. The concluding section will discuss the reasons for the inverse findings.

Table 4 displays the estimates and a 95% confidence interval of specific indirect effects of message reception and expression on behavioral intentions mediated by cognitive outcomes. H4 posited that cognitive outcomes will mediate the relationship between receiving relevant information and behavioral intentions. The results supported this hypothesis, demonstrating that the evaluation of Japan’s progressiveness served as a mediator by channeling the effects of receiving Japan-related messages on behavioral intentions, except for vigilant intention (β = 0.132, p < 0.01 for intimate intention; β = 0.148, p < 0.01 for interest in Japan; β = 0.133, p < 0.01 for social distance). Additionally, this study found that a higher level of receiving relevant messages led to a favorable impression of Japan (see Fig. 2). This in turn predicted higher levels of interest in Japan (β = 0.082, p < 0.001) and willingness to reduce the social distance from Japan (β = 0.068, p < 0.001).

As proposed in H5, the perceived threat of Japan partially mediated the effects of expressing Japan-related messages on behavioral intentions. Interestingly, we observed that a higher level of expressing Japan-related messages led to an increased perception of threat, resulting in a greater intention to remain vigilant (β = 0.266, p < 0.01) and to reduce the social distance from Japan (β = 0.093, p < 0.01). However, the impression of Japan did not mediate the relationships between expressing Japan-related messages and behavioral intentions towards Japan. Hence, H4 and H5 were partially supported.

Discussion

The results of this study provide valuable insights into the relationship between SNS communication behaviors (reception and expression) and national image perceptions. The analysis examined how bidirectional communicative behaviors (both receiving and expressing messages) regarding Japan influenced Chinese audiences’ cognitive responses and behavioral intentions. It contributes to the literature by addressing the underexplored expression effects of SNS communication on foreign countries’ national images. The key objective was to investigate how bidirectional communicative behaviors shape attitudes and intentions toward Japan. Five hypotheses were proposed to guide the analysis, and the results yielded mostly consistent support for these pathways.

In general, the findings demonstrate that the frequency of receiving and expressing relevant messages on SNS does exert influences on Chinese youth’s cognitive and behavioral intentions towards Japan. Specifically, for the total reception effect, the data shows that receiving Japan-related information had a causality with an improved evaluation of Japan’s progressiveness and a favorable impression of Japan, suggesting that exposure to Japan-related information, including potentially diverse or counter-attitudinal viewpoints, has a positive impact on the cognitive characteristics of Chinese youth. This supports the idea that incidental or cross-cutting exposure to foreign information may help moderate negative national images and foster more favorable views. On the other hand, the expression of Japan-related messages on SNS negatively affected the respondent’s evaluation and overall impression of Japan. This finding contrasts with some existing literature, which posits that individuals may reinforce their attitudes by engaging in expressive behavior. However, in this study, higher levels of expression were associated with less favorable perceptions of Japan. This seeming paradox–that reception of information is linked to more positive perceptions, while expression is associated with more negative views—can be understood through an alternative explanation, as suggested in the discussion. It is plausible that individuals with more extreme negative views about Japan are more likely to express these views on SNS, while those with more moderate or positive evaluations may be less motivated to engage in message expression. This could explain why expressing Japan-related messages is linked to more negative attitudes.

An interesting pattern emerged in the analysis of indirect effects: while reception had positive indirect effects on intentions like reducing social distance and fostering interest in Japan, expression showed a different trajectory. Expressing Japan-related messages positively affected vigilant behavioral intention, underscoring the idea that expression involves deeper cognitive engagement and may reinforce pre-existing negative cognitions. This aligns with previous findings that suggest goal-directed behaviors, like message production, require greater cognitive elaboration and self-reinforcement, which in turn influence behaviors (Namkoong et al. 2013; Shim et al. 2011; Yoo et al., 2016). The contrasting impact of message reception and expression suggests the need to further examine how different communicative behaviors interact with specific issue frames, such as historical tensions or security concerns. These nuanced dynamics could explain why frequent message expression results in less favorable evaluations of Japan.

One of the most intriguing findings is the variation in direction and slope of each frequency of communicative behaviors, in particular, message expression. Hierarchical plots show that the tendency of a frequent Japan-related message sender is inconsistent with the general tendency of other frequencies. Those who did not send Japan-related messages in the past 30 days scored higher in their evaluation of Japan’s progressiveness and had less vigilant intention. This divergence in behavior raises questions about the motivations behind expressing opinions on SNS and the broader effects of message production. This distinction between reception and expression effects highlights the complexity of how SNS engagement influences national image perceptions and suggests that engagement patterns may be influenced by the intensity of pre-existing opinions. This study’s theoretical contribution lies in its integration of a bidirectional message effects model within the O–S–R–O–R framework. This model recognizes the reciprocal and interactive features of SNS communication processes. By analyzing the reception and expression effects simultaneously, this study fills a gap in the literature that has historically focused on message reception without fully accounting for the impact of message production.

Implications

This study has significant implications both theoretically and practically. Firstly, this study, which found considerable support for the mediation model, provides insights into communicative behaviors and cognitive and behavioral intentions concerning international communication of national images, especially when compared with the studies rooted in a mere reception-effects paradigm. Secondly, the model’s value lies in its focus on the mechanism through which communicative behaviors generate effects, remedying the limitations of considering only simple, direct effects. Additionally, the study also identified the mediator of consuming and producing Japan-related messages on SNS and behavioral intentions. This finding has crucial implications for research into public diplomacy and international and political communication. Finally, the study’s findings not only benefit communication researchers but also media practitioners of all sorts, especially We Media practitioners and political communicators. The findings on the mechanism by which online communicative behaviors affect the Chinese public’s image of Japan may help researchers and practitioners develop more effective interventions to promote desirable attitudes or behaviors within individuals and improve Sino-Japan relations at the individual level.

Limitations and future directions

Although the present study has furthered the extant literature in some aspects, several limitations should be noted here. Firstly, the respondents of the study were undergraduate students from two 4-year public and comprehensive universities in Beijing, which may not be representative of the more general Chinese population. This limitation significantly affects the generalizability of the study’s findings, making it crucial to recognize the influence of the sample’s uniqueness. Secondly, the study primarily focused on behavioral intentions towards Japan rather than actual behaviors, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Thirdly, the analysis relied on self-reported data, particularly regarding exposure to information and behavior. Self-reports, while a common method in social science research, are prone to biases such as social desirability and recall bias, which may undermine the accuracy of the findings. This factor should be considered when interpreting the results, as the respondents’ reported behavior may not fully align with their actual behavior. This reliance on self-reported behavior opens the door to self-selection bias. Individuals with pre-existing negative attitudes toward Japan might have been more likely to engage in SNS messaging. Consequently, the observed relationship between SNS expression and attitudes may be distorted by the participants’ initial attitudes, leading to a potential reverse causality issue.

Given these limitations, several avenues for future research should be pursued. Although previous research has primarily focused on university students in major urban centers, recent trends indicate a broader adoption of SNS platforms across diverse demographics, including middle-aged and elderly populations. To address this, future investigations should encompass a more representative sample that reflects the diversity of SNS users nationwide, extending beyond the confines of first-tier cities. Additionally, there is a need to expand research beyond behavioral intentions to actual behaviors. While behavioral intentions provide useful insights, they may not always align with actual actions. Incorporating longitudinal studies or experimental designs can help address the limitations of self-reported data and offer a more precise understanding of how SNS communication influences attitudes toward national images. Moreover, although existing research has examined the expression-effect paradigm of SNS communication (e.g., Finkel and Smith, 2011; Prislin et al. 2011; Shah et al. 2017; Valkenburg, 2017; Yoo et al. 2016), there remain significant gaps in understanding its broader implications. Future studies should adopt interdisciplinary approaches to explore how SNS interactions impact psychological, social, and behavioral outcomes. By integrating insights from psychology, sociology, and communication studies, researchers can develop a more comprehensive understanding of how SNS interactions shape cognitions, beliefs, and behaviors at both individual and societal levels.

Conclusions

Despite numerous attempts by international relations scholars to uncover the reasons behind the decline of the Chinese public’s image of Japan, there has been a notable lack of research grounded in communication effects studies. In this interdisciplinary study, media and communication effect theories were utilized to explore the issue of national images. This study is among the first to comprehensively examine the impact of SNS communication on foreign country perceptions and its resulting outcomes. The study emphasizes the nuanced and mediated effects of SNS expression on behavioral intentions toward Japan. A mediation model was utilized to investigate the bidirectional effects of SNS communication on behavioral intentions toward Japan, mediated by cognitive characteristics. In conclusion, the results of the analysis align with theoretical and empirical literature, indicating that cognitive characteristics mediate the effects of online communication on behavioral responses. As SNS have become essential communication tools in everyday life, it is increasingly important to continue studying the communication processes and dynamics within communicators. Future research should focus on the mechanism of communication processes in greater detail.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Anholt S (2006) Competitive identity: the new brand management for nations, cities and regions. Palgrave Macmillan

Audigier V, White IR, Jolani S et al. (2018) Multiple imputation for multilevel data with continuous and binary variables. Stat Sci 33(2):160–183

Bem DJ (1967) Self-perception: an alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena. Psychol Rev 74(3):183–200

Bem DJ (1972) Self-perception theory. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 6:1–62

Bentler PM, Bonett DG (1980) Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol Bull 88(3):588–606

Bollen KA (1987) Total, direct, and indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol Methodol 17:37–69

Boyd DM, Ellison NB (2007) Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. J Comput-Mediat Commun 13(1):210–230

Browne MW, Cudeck R (1993) Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sage Publications

Burcu O (2022) The Chinese government’s management of anti-Japan nationalism during Hu-Wen Era. Int Relat Asia-Pac 22(2):237–266

Byrne BM (2010) Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge

Cappelletti A (2019) Between centrality and re-scaled identity: a new role for the Chinese state in shaping China’s image abroad: the case of the Twitter account of a Chinese diplomat in Pakistan. Chin Political Sci Rev 4:349–374

Castells M (2008) The new public sphere: global civil society, communication networks, and global governance. Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci 616(1):78–93

Cho J, Shah DV, McLeod JM et al. (2009) Campaigns, reflection, and deliberation: advancing an O‐S‐R‐O‐R model of communication effects. Commun Theory 19(1):66–88

Cui S (2012) Problems of nationalism and historical memory in China’s relations with Japan. J Hist Sociol 25(2):199–222

Cull NJ (2009) Public diplomacy: lessons from the past, vol 22. Figueroa Press, Los Angeles, CA

Dinnie K (2015) Nation branding: concepts, issues, practice. Routledge

Festinger L (1962) A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press

Field A, Miles J, Field Z (2012) Discovering statistics using R. Sage Publications

Finkel SE, Smith AE (2011) Civic education, political discussion, and the social transmission of democratic knowledge and values in a new democracy: Kenya 2002. Am J Political Sci 55(2):417–435

Gerbing DW, Anderson JC (1992) Monte Carlo evaluations of goodness of fit indices for structural equation models. Sociol Methods Res 21(2):132–160

Gillmor D (2006) We the media: grassroots journalism by the people, for the people. O’Reilly Media, Inc

Gries PH, Steiger D, Wang T (2016) Popular nationalism and China’s Japan Policy: the Diaoyu Islands protests, 2012–2013. J Contemp China 25(98):264–276

Hayden C (2012) The rhetoric of soft power: public diplomacy in global contexts. Lexington Books

Hoyle RH, Panter AT (1995) Writing about structural equation models in structural equation modeling. In Hoyle RH (ed) Structural equation modeling: concepts, issues, and applications. Sage, pp. 158–176

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6(1):1–55

Hyun KD, Kim J, Sun S (2014) News use, nationalism, and internet use motivations as predictors of anti-Japanese political actions in China. Asian J Commun 24(6):589–604

Iwabuchi K (2015) Pop-culture diplomacy in Japan: soft power, nation branding and the question of ‘International Cultural Exchange'. Int J Cult Policy 21(4):419–432

Jiang H (2013) Chugoku ni okeru Nihon imēji oyobi sono kouzo ni kan’suru ken’to [A structural model for the images of Japan in China]. Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies 29:221–249

Jiang H (2014) Gen’dai chūgokujin ga idaku tainichi imēji no keisei niokeru jyohougen no yakuwari [The effects of information sources on modern Chinese images to Japan]. Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies (87), pp. 53–70

Lam PE (2007) Japan’s quest for “Soft Power”: attraction and limitation. East Asia 24(4):349–363

Li Y (2006) Chūgokujin no nihonjin imēji ni miru media no eikyō [The influence of the media on the Chinese’s images of the Japanese]. J Mass Commun Stud 69:22–40

Lu Y, Vierrether T, Wu Q, Durfee M, Chen P (2022) Social Media use and political consumerism during the US–China trade conflict: an application of the OSROR model. Int J Commun 16:4890–4906

Lüders M (2008) Conceptualizing personal media. N Media Soc 10(5):683–702

Markus H, Zajonc RB (1985) The cognitive perspective in social psychology. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E (eds) Handbook of social psychology (3rd ed.). Random House, pp. 137–229

McConnell DL (2008) Japan’s image problem and the soft power solution. In: Watanabe Y, McConnell DL (eds) Soft power superpowers: cultural and national assets of Japan and the United States. ME Sharpe, Armonk, NY, pp. 18–33

McQuail D, Windahl S (2015) Communication models for the study of mass communications. Routledge

Midooka K (1990) Bunka shūdan no imēji: masu leberu ni okeru bunka rikai [Cultural group image: cultural understanding at the mass level]. In: Daibo I, Ando K, Ikeda K (eds) Shakai Shinrigaku Pāsupekuteibu 3: Shūdan Kara Shakai E [Social psychology perspectives 3: from group to society]. Seishin Shobo, Tokyo

MOFA (2022) Diplomatic Bluebook 2022. https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/culture/public_diplomacy.html. Accessed 25 Jan 2025

Mutz DC (2006) Hearing the other side: Deliberative versus participatory democracy. Cambridge University

Namkoong K, McLaughlin B, Yoo W et al. (2013) The effects of expression: how providing emotional support online improves cancer patients' coping strategies. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2013(47):169–174

Nye JS (1990) Soft power. Foreign Policy 80:153–171

Nye JS (2004) Soft power: the means to success in world politics. PublicAffairs Books

Petty RE, Cacioppo JT (1986) The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In: Berkowitz L (ed) Advances in experimental social psychology, vol 19. Academic Press, pp. 123–205

Pingree RJ (2007) How messages affect their senders: a more general model of message effects and implications for deliberation. Commun Theory 17(4):439–461

Prislin R, Boyle SM, Davenport C et al. (2011) On being influenced while trying to persuade: The feedback effect of persuasion outcomes on the persuader. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 2(1):51–58

Sato T (2012) Bunka teikoku ‘nihon’ ni okeru mediaron no hinkon [Poverty of the discussion of media communication in Japan as a culture nation]. In: Sato T, Watanabe Y, Shibauchi H (eds) Sofuto pawa no media bunka seisaku [Media cultural policy of soft power]. Shin’yousha, Tokyo, pp. 143–176

Shah DV (2016) Conversation is the soul of democracy: expression effects, communication mediation, and digital media. Commun Public 1(1):12–18

Shah DV, McLeod DM, Rojas H, Cho J, Wagner MW, Friedland LA (2017) Revising the communication mediation model for a new political communication ecology. Hum Commun Res 43(4):491–504

Shah DV, Cho J, Nah S, Gotlieb MR, Hwang H, Lee NJ, McLeod DM (2007) Campaign ads, online messaging, and participation: extending the communication mediation model. J Commun 57(4):676–703

Shao G (2009) Understanding the appeal of user-generated media: a uses and gratification perspective. Internet Res 19(1):7–25

Shim M, Cappella JN, Han JY (2011) How does insightful and emotional disclosure bring potential health benefits? study based on online support groups for women with breast cancer. J Commun 61(3):432–454

Tucker LR, Lewis C (1973) A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 38(1):1–10

Turcotte J, York C, Irving J, Scholl RM, Pingree RJ (2015) News recommendations from social media opinion leaders: effects on media trust and information seeking. J Comput-Mediat Commun 20(5):520–535

Valkenburg PM (2017) Understanding self-effects in social media. Hum Commun Res 43(4):477–490

Valkenburg PM, Peter J, Walther JB (2016) Media effects: theory and research. Annu Rev Psychol 67:315–338

Vekasi K, Nam J (2019) Boycotting Japan: explaining divergence in Chinese and South Korean economic backlash. J Asian Secur Int Aff 6(3):299–326

Whalley J, Weisbrod A (2012) The contribution of Chinese FDI to Africa’s pre crisis growth surge. Glob Econ J 12(4):1–26

Yoo W, Choi D, Park K (2016) The effects of SNS communication: how expressing and receiving information predict MERS—preventive behavioral intentions in South Korea. Comput Hum Behav 62:34–43

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on a section of the author’s Ph.D. dissertation at Waseda University, which has undergone significant revision and expansions for publication. This work was supported by the National Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences under the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 22CGJ051).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The research was conducted solely by the author, who was responsible for the following: conceptualization of the study, designing the methodology, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. The author also prepared and revised the manuscript for publication, approved the final version, and took full responsibility for the accuracy, integrity, and completeness of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The research was approved by the Ethics Review Committee on Research with Human Subjects of Waseda University (Approval Number: 2017-199) on 5 October 2017. All procedures adhered to relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. The scope of approval covered all aspects of the study, including participant recruitment, data collection, and data analysis. Participant anonymity and confidentiality were strictly maintained.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation. Participants were fully informed about the purpose of the study, the use of their data, their right to withdraw at any time, and the compensation provided for their participation. No vulnerable individuals were involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T. Scrolling, sharing, shaping: cognitive and behavioral effects of SNS communication on Japan’s national image in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 92 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04377-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04377-y