Abstract

Recent decades have witnessed a massive movement supported by many governments to make an effort to promote transparency through the dissemination of data to end users and society in general. Although numerous studies have examined the effects of information and communication technologies (ICT) on open data portals, the influence of data dissemination instruments and data governance practices on the quality of data published in open data portals has received less attention. This paper seeks to fill that gap. The analysis is based on survey responses from teams responsible for managing open data in public organisations in Brazilian government data portals. The study reveals that the information dissemination, institutionalisation at the macro level and the support resources of open data programmes influence the quality of published data. These conclusions are of interest to politicians and practitioners involved in raising awareness of the usability of open data portals. Government agencies seeking to stimulate development should consider improving open data governance practices and increasing user awareness of their availability to promote user engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Democratic countries have witnessed the consolidation of the dissemination of open data (Attard et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2022; Lourenço, 2015) by distributing or transmitting data to users (for example, by using electronic formats, including the internet, paper publications and files available for public use). A massive movement supported by many countries launched a progressive government transparency process to share and open their data (Tejedo-Romero and Araujo, 2018; Zhang and Kimathi, 2022). The number of countries that have open data portals has increased from 46 in 2014 to 153 in 2020 (United Nations, 2020; Yang and Wu, 2021).

Open data has a multidimensional nature, comprising open data provision, open data use or both (Borycz et al., 2023; Ruijer et al., 2017; Zuiderwijk et al., 2021). The concept has been defined by the Open Knowledge Foundation (2017), Kassen (2019) and Talukder et al. (2019) as data sets that can be freely accessed, modified and shared by anyone (while preserving their characteristics) and later consumed by others for any purpose.

Disclosing up-to-date public data is a critical success factor for individuals and organisations in professional and business fields (Huang et al., 2021; Rong and Grover, 2009). One of the challenges is the dissemination of quality data to end users, such as entrepreneurs, government agency staff, researchers, private industry. (Begany and Martin, 2020; Tejedo-Romero and Araujo, 2023). The quality of open data is a multidimensional concept which includes falling within the accepted fitness for use, “multivalence” (the different values ascribed to data) and compliance with specifications (common, non-proprietary data standards)Footnote 1 (Ehrlinger and Wöß, 2022).

Governments need to establish an effective governance structure and processes to formally identify relevant data to ensure the quality and timeliness of its publication (Adam, 2020; Cumbie and Kar, 2016; Zuiderwijk et al., 2021). They create value by ensuring data quality in terms of accuracy, consistency and timeliness (Cantador et al., 2020; Nikiforova and McBride, 2021). Studies have examined open data portals, mostly focusing on open data demand from the perspective of citizens. However, few studies have analysed the processing and dissemination of open data which may contribute to data quality, from the supply-side perspective (Zhang and Kimathi, 2022; Zuiderwijk et al., 2021). Effective data governance ensures that data management staff adopts practices that make data consistent and trustworthy and that don’t allow it to be misused. This study fills this gap in the literature on open data portals by focusing on an emerging economy: the case of Brazil.

Based on the principles of open government, it is worth exploring the influence of the dissemination instruments and data governance practices that can contribute to the quality of data published on open data portals. To do so, it is necessary to explore issues related to the following questions: Do the information dissemination instruments used in the open data portals contribute to the quality of open data? What governance practices of open data portals contribute to the quality of open data? The primary aim of this study is to understand how instruments and practices of disclosure and data governance influence open data policy outcomes, in particular the quality of data that is made available to end users. For this purpose, the instruments for disseminating information and the data governance of various organisations present on open data portals in Brazil were analysed from the perspective of the teams responsible for managing open data in order to identify the influence of management practices on data quality. The study intends to contribute to extant literature by increasing knowledge about management practices and the challenges that need to be overcome in open data programmes.

The data for this study were obtained through a questionnaire addressed to the teams responsible for publishing open data from organisations present on Brazilian open data portals. The focus on a single country is meant to ensure greater homogeneity in the results. Brazil was chosen because it has been involved in the Open Government Partnership since its inception, a sign of its commitment to open data programmes. Since then, the country has been developing a national policy of open data. This is a relatively new topic, whose findings could be useful and provide new insights into the management of open data portals for academics and practitioners. The paper begins with a review of the literature and the development and reasoning of the hypotheses, followed by the methodology, results, discussion and conclusion.

Literature review

Open data are any data produced or processed and collected by public organisations which are publicly available to advance transparency and promote the innovative use of data (Ansari et al., 2022; Kassen, 2019). Open data can be freely used, reused and distributed by anyone (Zuiderwijk et al., 2021) to disseminate information and strengthen accountability.

Countries committed to the idea of Open Government expect that it will promote transparency and accountability, enabling a more democratic government that facilitates close cooperation between public administrations, politicians, representatives of industry and the general public. The flexibility of information technologies (IT) plays an important role in open data initiatives (Adam, 2020; Alzamil and Vasarhelyi, 2019; Tejedo-Romero et al., 2022). IT is used to implement open data portals to promote government transparency, participation and collaboration (Huang et al., 2021; Tejedo-Romero and Araujo, 2023; Zhang and Kimathi, 2022). The adoption of citizen-oriented public data policies has been used as a way to involve citizens, increasing trust in government and the public value of transparency policies (Begany and Gil-Garcia, 2021). Government data is a valuable asset and a latent source of value for both the public and private sectors (van Ooijen et al., 2019). The expectation of Open Government (and open data dissemination) is that it will empower citizens and inspire a wide range of users to work creatively with open data to spur innovation, scientific discovery and entrepreneurship (Borycz et al., 2023).

Open data portals are evaluated based on the application of open data principles (Attard et al., 2015; Wang and Shepherd, 2020), which were initially formulated by Berners-Lee (2006), Malamud et al. (2007) and the Open Knowledge Foundation (2017), seeking to define guidelines that would guarantee data connection and information delivery. Furthermore, Kundra (2011) and the UK Public Sector Transparency Council have developed principles and guidelines on how to publish data and promote transparency (Public Sector Transparency Board, 2012; Ubaldi, 2013). The principles are related to practical and direct application and seek to frame the processes of production and dissemination of open data, aimed at quality, data governance and encouraging citizen participation (Issa and Isaias, 2016). Other recommendations identified in extant literature (Janssen et al., 2020; Robinson and Scassa, 2022) emphasise the technical nature of the topic, the introduction of new governance dimensions in open data and guidelines to promote institutionalisation, the availability of supporting resources and information dissemination mechanisms. In addition, the importance of leadership in open data programmes has been highlighted. These principles can be grouped into three main dimensions: 1) the dissemination of information, meaning data are made available to the widest range of users (Ansari et al., 2022; Johnson et al., 2022); 2) data quality, meaning data are collected at the source, are not in aggregate or modified forms, are made available as quickly as possible in a format over which no entity has exclusive control, are not subject to any copyright, patent, trademark or trade secret regulation and are reasonably structured to allow automated processing (Begany and Martin, 2020; Zuiderwijk et al., 2021; Ehrlinger and Wöß, 2022) and 3) data governance, which comprises the existence of an organisational structure, the availability of support resources, work processes and routines, information dissemination mechanisms and leadership in open data programmes (Ruijer et al., 2020; Robinson and Scassa, 2022; Issa and Isaias, 2016).

Providing end users and society with access to open data is one of the axes that must be present in open data initiatives and must be considered in the planning phase. Attard et al. (2015) and Ubaldi (2013) pointed out the importance of identifying relevant data sets that are candidates for publication, as well as creating mechanisms events to disseminate them. Training the public that will consume the data and promoting meetings and workshops are also considered tools for disseminating information (Gascó-Hernández et al., 2018; Safarov, 2019).

Extant literature claims that the governance of open data is crucial for data processing and the dissemination of quality open data (Kim and Eom, 2019; Ruijer et al., 2020; Janssen et al., 2020; Robinson and Scassa, 2022). The institutionalisation of open data in public organisations (Kawashita et al., 2022; Tejedo-Romero et al., 2022) through the establishment of organisational structures, work processes and routines to collect and process open data has been analysed by several academics (Adamczyk et al., 2021; Kim and Eom, 2019; Safarov, 2019; Saxena, 2018). According to Wang and Lo (2016), process reengineering is necessary to create open data policies. Hartog et al. (2014) noted that better programme results involve the ability to automate data extraction without manual actions by public employees. In the same vein, scholars have argued that support resources available in open data programmes are important for modernising systems (Ruijer and Meijer, 2020) and improving data visualisation (Zuiderwijk and Reuver, 2021). The application of tools to facilitate the search for data and highlight its visibility has been cited by Lourenço (2015) and Zuiderwijk and Janssen (2014). According to Kim and Eom (2019), it is important to allocate a budget dedicated to these programmes to ensure adequate investment in infrastructure. Furthermore, strong support from senior and middle management is critical to the success of open data programmes (Ruijer and Meijer, 2020), as leadership plays an important role in driving and motivating employees (Yang and Wu, 2016), in addition to contributing to the mobilisation of tangible and intangible resources and coordinating actors (Kim and Eom, 2019). According to Luna-Reyes et al. (2016), political leadership is the most vulnerable element in open data initiatives, as it can be affected by the alternation of power and elections.

Measuring the quality of open data is not a straightforward process because it entails taking into consideration multiple and varying quality dimensions, as well as various open data stakeholders who - depending on their role/needs - may have different preferences regarding the dimensions’ importance. The literature emphasises the quality of published data as a result of the application of governance practices (Kučera et al., 2013; Lourenço, 2015; Park and Gil-Garcia, 2022) based on the availability of data and the presence of technical and quality control standards. Publishing data without proper quality control may compromise its use (Vetrò et al., 2016). In addition, metadata attribution processes can be complex (Zuiderwijk and Janssen, 2014), as open data involves data sets that, when created, were not originally designed for this purpose. Finally, quality can also be obtained by addressing the feedback from users (Safarov, 2019). Few studies have examined data governance practices to ensure the quality of data published on open data portals from the data management staff perspective (Zhang and Kimathi, 2022; Zuiderwijk et al., 2021). This study is a novelty and intends to fill this gap in the literature reflecting the perspective of the data management staff rather than citizens that have been examined in previous papers. Since open data might play a crucial role in social development, it is important to explore it from the perspective of those responsible for disseminating it, as well as the influence of dissemination instruments and data governance practices on the quality of open data portals.

Hypothesis development

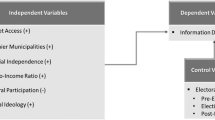

Grouping open data principles that are presented in the literature by the similarity of themes allows to identify three main dimensions (Matheus and Janssen, 2020; Safarov, 2019; Wang and Shepherd, 2020; Yang and Wu, 2021; Kim and Eom, 2019; Alzamil and Vasarhelyi, 2019; Ruijer and Meijer, 2020). Figure 1 shows the open data dimensions selected for this study based on this grouping.

Among the best-known quality definitions are “fitness for use,” as defined by Juran et al. (1974), and “conformity to specifications”, suggested by Crosby (1987). Vetrò et al. (2016) reported that for ISO 25012—which regulates software quality—data quality is defined as the ability of data to satisfy established needs when used under specific conditions. Data quality is a multidimensional concept which includes the dimensions of accuracy, completeness, consistency and timeliness (Ehrlinger and Wöß, 2022). Regarding open data, based on the principles found in the literature, the concept of quality can be understood as the data being in accordance with common and non-proprietary data standards (Ehrlinger and Wöß, 2022). This open data quality approach fits with the accepted quality concepts of fitness for use and specification compliance. Addressing the mismatches between users’ needs and what is provided in open data portals is essential for tapping into their potential value.

Extant literature states that to ensure data quality it is necessary that data quality principles are present (Cantador et al., 2020; Nikiforova and McBride, 2021; Adam, 2020; Cumbie and Kar, 2016; Zuiderwijk and Reuver, 2021), first, through the availability and usability of data to guarantee end-users and society access to open data (the dimension of information dissemination). Usability of data is a generic quality criterion, which indicates how easily the published data can be used (Attard et al., 2015). It is directly related to determining to what degree open data are accessible, interoperable, complete and discoverable. The second crucial component is the dimension of data governance, which comprises making available support resources for open data programmes and investing in technological infrastructure; institutionalisation at the macro and micro levels; providing a governance structure; tools and instruments for dealing with data and adopting practices that make data consistent and reliable. The success of data governance also depends on the leadership in coordinating, driving and motivating employees.

Dissemination of information

Governments use a variety of instruments to publicise their open data programmes and increase users’ access to information, such as symposia, workshops, data mining competitions (hackathons) and training (Yang and Wu, 2021). These actions contribute to the dissemination, discovery and use of data (Dawes et al., 2016) and help to attract public attention and create opportunities to increase the engagement of citizens and other stakeholders (Attard et al., 2015) and make them better informed (Johansson et al., 2021; Tai, 2021). Government open data initiatives are more likely to succeed if users have technical skills and knowledge (Safarov, 2019). The effect of user training as a driver of use has been reported by Gascó-Hernández et al. (2018) in a study carried out in Italy, Spain and the United States. The literature does not, so far, indicate a direct relationship between the dissemination of open data programmes and data quality. Safarov (2019), however, noted in a study carried out in the United Kingdom that promoting the involvement of society and end users through feedback is one of the priority objectives for improving data quality. User feedback and participation are likely viable and effective in disseminating information about open data, which can motivate an improvement in the data quality of these programmes (Wang and Shepherd, 2020). Thus, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H1: There is a positive relationship between information dissemination of open data programmes and data quality.

Governance: support resources

The use of resources to support the publication of open data is considered by the literature to be a determinant that contributes to the quality of the data that is disseminated (Ruijer et al., 2020). Alexopoulos et al. (2015) mentioned in a study on open data portals in Greece that the use of more technology in the publishing processes allows the provision of more tools to discover, visualise and obtain feedback from users, with the benefit of increasing data quality. According to Alzamil and Vasarhelyi (2019), the publication of current and high-quality data depends on the allocation of human resources to the organisation and the preparation of the data. Kim and Eom (2019) argued that the processes of publishing open data comprise extra tasks that demand resources, requiring the existence of a specific budget to ensure that the publication of data is carried out through processes that guarantee its quality. Thus, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H2: There is a positive relationship between support resources of open data programmes and data quality.

Governance: institutionalisation

Institutionalisation, one of the dimensions identified in the literature, is represented by the organisational structure responsible for open data at the macro level and by the work processes at the micro level (Kawashita et al., 2022; Safarov, 2019). Dawes et al. (2016) highlighted the importance that the selection, choice and publication processes have in the dissemination of quality data. The literature states that the institutionalisation of open data governance through organisational structures (the macro level), and work processes and open data collection and processing routines (the micro level) guarantees higher quality open data (Adamczyk et al., 2021; Kim and Eom, 2019; Kawashita et al., 2022; Lourenço, 2015). In the same way, Ubaldi (2013) observed that good data management practices that provide the necessary tools and instruments value the effort needed to make machine-readable data available, which is one of the basic principles linked to the quality of open data. Hartog et al. (2014) stated that improving programme results and the quality of available data involves the ability to automate their extraction without manual action on the part of public servants. Consequently, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H3: There is a positive relationship between the macro-level institutionalisation of open data programmes and data quality.

H4: There is a positive relationship between the micro-level institutionalisation of open data programmes and data quality.

Governance: leadership

The role played by public managers in the implementation of open data portals and their influence on users’ access to data is a relevant topic in the literature (Johnson et al., 2022). According to Wang and Lo (2016), top management support is perceived as an important factor in promoting these programmes. Kim and Eom (2019) pointed out that the ability to mobilise tangible and intangible resources and apply them in the right places and processes under the guidance of capable leaders contributes to the success of open data projects. The continuation of these projects in the future will depend on top managers’ commitment to the development and use of methodologies to produce and distribute the data (Styrin et al., 2017). Ruijer and Meijer (2020) stressed that the publication of open data with low leadership commitment, supported only by guidelines and technical guides, resulted in low-quality data that were rarely updated. It is expected that the support and monitoring of open data portals by top management will create conditions to establish processes capable of promoting better data quality. Thus, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H5: There is a positive relationship between the leadership of open data programmes and data quality.

The open data policy in Brazil

Access to public information is a fundamental right that has been enshrined in the Federal Constitution since 1988 (Presidência da República, 1988). The first initiative to promote open data at the national level was the Transparency Portal, created in 2004 by the Comptroller General of the Union (CGU), which provides information on the use of public financial resources by the federal government (Controladoria Geral da União, 2004). The incorporation of open data into the scope of transparency was approved by the Access to Information Law (Law n° 12.527 of 18 November 2011), which regulates the right of access to information, determining publicity as the rule and secrecy as an exception (Presidência da República, 2011). Thus, both the Transparency Portal and the Open Data Portals provide information and data on most activities and operations of federal public bodies and are important instruments in the pursuit of transparency policy and societal development. Subsequently, the Open Data Policy of the Federal Executive Branch (Decree No. 8777 of 11 May 2016) established for public organisations the obligation to actively disclose data in an open format and in line with the principles defined for information dissemination (Presidência da República, 2016). The main instruments for implementing this policy are Open Data Plans (PDA), which guide the implementation and promotion of data opening by public organisations, and the Open Data Portals (http://www.dados.gov.br).

The Open Data Portal is the result of the implementation of a data disclosure policy for end users and society, managed by the CGU, which monitors the publications and commitments of public organisations through the Data Monitoring Panel (Controladoria Geral da União, 2021). Published data must meet requirements that include publicity, social participation and citizen involvement, unrestricted access to data, periodic updating and database integrity and interoperability. These requirements are important to ensure open data disclosure. The portal currently hosts 202 public organisations, with 10,987 data sets. Publication on the portal is done directly by participating organisations, which belong to different areas of the public sector, namely financial entities, regulatory agencies, defence, security and public order, ministries, environmental and social protection, education, research and health, among others. The portal does not contain data that are considered confidential, as data subject to confidentiality or privacy restrictions, as defined in the Access to Information Law, need to be previously classified by those responsible and are not published (Controladoria Geral da União, 2016).

Research design

The research design of this study is non-experimental and has cross-sectional characteristics.

Method

To answer the research questions and test the hypotheses, a survey method was used. The survey questions aimed to examine how the information dissemination instruments and the information about the governance structure of the open data programmes related to data quality. The results reported in this paper are based on the opinion of data management staff involved in the processing and disclosure of data from those organisations whose web pages were operational in the Brazilian open data portals.

Descriptive statistics were used to determine the extent of the application of open data principles to data quality, information dissemination instruments and governance practices. To determine impact, this was followed by factorial analysis and linear regression. Regression analysis was a good method in this case since the goal was to determine the direct impact of the information dissemination instruments and governance practices on data quality.

Sample and data collection

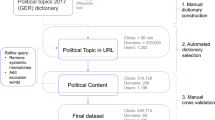

The empirical study drew on the entire population of organisations whose web pages were operational on the Brazilian open data portals. At the time the study was carried out, 190 organisations published data or metadata that were considered operational in a total population of 202 organisations.

Using the Fala.BR—Integrated Ombudsman and Information Access Platform (https://www.gov.br/cgu/pt-br), each organisation was contacted requesting authorisation to respond to the questionnaire and the provision of the names, emails and telephone numbers of the open data management team so that the questionnaire could be sent. Of the 190 organisations which were contacted, 164 provided authorisation (86%) and either the emails of managers and teams or a generic email of the department responsible for open data. The 164 organisations that authorised the sending of the questionnaire provided 393 contact emails.

Before general distribution, a pilot questionnaire was run with five selected respondents who were considered to be representative of the whole sample. Moreover, the final questionnaire was validated by several expert researchers in this field. The reliability of the questionnaire is discussed in more detail below. Finally, using the Qualtrics software, a link to the anonymous online survey was sent by email to those staff responsible for disseminating open data and to the respective data production and publication teams from January to February 2021. From the 393 questionnaires sent, 215 complete responses were received, which corresponds to a response rate of 55%. This was considered an acceptable rate and representative of the total population of the organisations, consequently avoiding possible bias from non-respondent cases. At the same time, and to address the possibility of selection bias in the survey responses, the characteristics of the survey respondents were compared to those of the population in terms of government area and legal form of organisation. The resulting sample was balanced between organisations from all government areas and the legal form of organisation in which participants were employed. The profile of the surveyed participants is explored later in the results section.

The questionnaire was developed in consideration of the principles identified in the open data literature. These were grouped into three major dimensions: quality (10 items), information dissemination (10 items) and governance, which was further broken down into three sub-dimensions: support resources (five items), leadership (five items) and institutionalisation. The latter was broken down into two other categories: macro-level institutionalisation (six items) and micro-level institutionalisation (five items).

Variables and empirical model

Figure 2 presents the variables used to determine the factors that influence data quality based on open data principles.

As in any empirical study, it is important to consider how the proposed questionnaire items should be measured for each of the variables to be considered. Due to nature of the items, it was necessary to adopt different measurement scales. To quantify each of the dimensions (variables) of the study, weighted indexes were developed using factor analysis.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was data quality. To operationalise and capture data on the perception of the quality of open data, the survey was built based on the characteristics previously identified in the literature (Dawes et al., 2016; Matheus and Janssen, 2020; Safarov, 2019). The data quality variable was computed through 10 questions (10 items).

Independent variable

The variables identified in the literature (Kim and Eom, 2019; Ruijer et al., 2020; Ruijer and Meijer, 2020; Wang and Shepherd, 2020; Yang and Wu, 2021) that can influence data quality were as follows: information dissemination, support resources, macro-level institutionalisation, micro-level institutionalisation and leadership. These variables were operationalised through the survey. The information dissemination variable was constructed from dichotomous questions (yes or no). The variables support resources and leadership were computed using a five-point Likert scale. The macro-level institutionalisation variable was composed of dichotomous questions that represented the perception of the organisational structure, and the micro-level institutionalisation variable, which represents the perception of work processes, was computed using five-point Likert-scale questions.

Control variable

To avoid biased results, the following control variables were selected: age, gender, seniority and legal form. These variables were obtained through the survey. The age variable was categorised according to the ages of the respondents: less than 30 years old; between 31 and 40 years old; between 41 and 50 years old and over 51 years old. The gender variable defined the sex of the respondent (male or female). The seniority variable was defined as the number of years that the respondent worked in the organisation, according to the following criteria: up to five years; from six to 10 years; 11 to 15 years and 16 years or more. The legal form variable was the typology of the organisation where the respondent works: direct administration (public service answering directly to the minister); indirect administration-autarchy (public service that does not answer directly to the minister); indirect administration-foundation (public service that does not answer directly to the minister) and other (this group includes organisations such as public companies, mixed-economy companies and others).

Empirical model

To verify the influence of the independent variables on the dependent one, a multivariate linear regression model was built and empirically tested.

where α is the intercept, Ɛ is the error term and βn are the coefficients calculated by the regression model.

Multiple regression analysis was carried out using data quality as the dependent variable, with the following factors of open data dimensions as independent variables: information dissemination, support resources, micro-level institutionalisation and macro-level institutionalisation. Age, gender, seniority and legal form were included as control variables. Multicollinearity was removed using principal component (or factor) analysis to derive a new set of orthogonal (uncorrelated) predictors. One factor was extracted for the dependent and each of the independent variables using the principal components method, absolute values less than 0.2 were removed and the variables were saved as regression scores. The regression scores produced were entered as dependent and independent variables in the regression analysis.

Results

This section presents the empirical results of the study, namely the profile of the respondents and the analysis of the descriptive and multivariate statistics.

Respondents’ profile

Table 1 shows the profile of the 215 federal civil servants who responded to the survey. Women represent 42% of responses and men 58% of responses. The vast majority of respondents (92%) belong to public institutions, direct administrations and foundations. The largest number of responses came from the education area (42%) followed by general civil service organisations (27%) and economic affairs (15%), totalling 84% of the responses received. Most respondents (79%) have been working there for more than five years and are between 30 and 50 years old (76%).

Reliability of the questionnaire

To prove the reliability (internal consistency) of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha and Split-Half tests were performed for the set of 215 responses obtained, as shown in Table 2:

Results for all dimensions show acceptable reliability and validity.

Descriptive analysis

Data quality

The frequency of occurrence for each of the criteria defined in the literature for data quality (Matheus and Janssen, 2020; Safarov, 2019) is shown in Table 3.

Most of the 215 respondents (89% and 87%, respectively) stated that the data are published in an open format and that downloading is possible. These are two basic characteristics of open data that denote compliance with the basic rules for open data Additionally, but with greater moderation (71 and 61%), were the declared periodicity and the publication of metadata. These are important conditions for using the data in research and policy-making decisions. In general, quality requirements were judged as medium to good (around 50–60%). The exception was the fine granularity of the data (37%) and the presence of other forms of visualisation (39%). These features often require more sophisticated IT tools to be in place. The perception of the respondents indicates that the basic formal requirements to obtain data quality are present, but there is room for progress in updating data and metadata and a need to invest in ways to make data more accessible to end users and society.

Information dissemination

Table 4 shows that the majority of respondents (68%) considered the publication of open data on the institutional website as an instrument to disseminate information, followed by public consultations and publication on social networks. These are CGU’s recommendations for the preparation and dissemination of open data in the PDAs of public bodies (Controladoria Geral da União, 2020).

The least mentioned instrument by the respondents was data exploration contests, with only 3% of the responses. Data contests have been pointed out in the literature as an effective instrument to disseminate open data. The publication of data on websites as a dissemination tool may be the most frequent instrument because it requires less effort and uses traditional communication channels. It can be inferred from the survey responses that the dissemination of information through participatory channels, training, lectures, audiences and contests for data exploration is still not common or routine. These forms of dissemination represent an opportunity to improve interaction with end users and society.

Support resources

Table 5 presents the respondents’ perception of support resources using a Likert scale (Likert, 1932). Overall, the data suggest that respondents’ perception was positive regarding the competence of people dealing with open data, documentation and publishing tools (Agree and Strongly Agree responses represent more than 60%).

Regarding the staff involved in publishing the data, opinions were not positive, which suggests that not all organisations have the necessary human resources for the tasks they need to perform. As for the adequacy of the open data budget, this was the only question in the questionnaire with 48% of neutral responses, which may indicate that those responsible for open data do not have information on this question due to their technical roles. In general, the graph shows a trend of positive responses, which indicates the presence of resources to support the publication of open data.

Institutionalisation

The institutionalisation dimension was evaluated from the perspective of macro-level (organisational) and micro-level (work processes) institutionalisation. The responses regarding macro-level institutionalisation addressed the existence of open data organisational structures and the responses to micro institutionalisation recorded perceptions about the routines associated with open data (see Tables 6 and 7).

The table above shows that 59% of respondents mentioned the existence of an open data unit, which is a first step towards institutionalising the data area in an organisation. The presence of a team specifically designed for this task was mentioned by 52% of respondents. Forty-nine percent of respondents stated that there are governance instruments for managing open data. However, the allocation of a specific budget and the presence of civil society volunteers or end users contributing to the open data was not frequent. Regarding the existence of a dedicated budget, only 5% of the respondents responded positively, which indicates that the publication of open data is done by existing employees without the great possibility of carrying out more dissemination actions that could leverage the use of data and benefit society.

Table 7 shows that the respondent’s perception was positive regarding the existence of open data processing processes for a timely response to citizens within the deadline (84% of respondents Agreed or Strongly Agreed). There was also a positive opinion on the data selection and quality control processes. The survey results show that work processes for choosing data, verifying data quality and publishing open data have been implemented. Conducting employee training and preparation is seen as neutral (31% of respondents Agreed or Strongly Agreed). However, with regard to the automation of data publication, which is recognised in the literature as one of the vectors of quality promotion, most respondents (69%) disagreed with the existence of these processes.

Leadership

Table 8 shows more prominently the perception that managers were informed about open data activities (82% overall agreement). This result is expected since open data plans need to be formally approved by the directors of each agency to be accepted by the CGU.

The participation of managers in decision-making and planning was seen as positive, but to a lesser extent than managers’ knowledge on the subject. The perception of the exercise of direct leadership and employee motivation was predominantly neutral (33% and 41% of responses, respectively). This result was expected since the structures of public organisations are strongly based on hierarchy, and open data teams may have little to no contact with managers. The big picture suggests that leadership in open data programmes remains formal and low in proactivity.

In addition, a principal component factor analysis of each of the open data dimensions was carried out to reduce its size and obtain a weighted index, and a regression analysis was carried out to contrast the proposed hypotheses.

Factorial analysis and multivariant analysis

Based on the 215 responses given by the teams responsible for managing open data that make up the sample, the latent dimensions summarising the information in each of the six major dimensions/sub-dimensions of open data relating to quality (10 items), information dissemination (10 items), support resources (five items), leadership (five items), macro-level institutionalisation (six items) and micro-level institutionalisation (five items) were examined using the Principal Components Analysis (PCA) method. PCA explores the underlying patterns of relationships between dimensions/sub-dimensions, which generates new variables (factors) that are uncorrelated with one another and that avoid the multicollinearity problem in the regressions.

To apply the PCA method, the correlation matrix of the items/variables of the dimensions/sub-dimensions involved was submitted to various tests to highlight data adequacy, as shown in Table 9. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) statistic is appropriate because it presents a value higher than the recommended value of 0.50, and the Bartlett test is statistically significant at the p < 0.001 level. These results show that the sample can be subjected to PCA to uncover the underlying patterns of the variables/items of each of the dimensions/sub-dimensions.

As Table 9 shows, the factor analysis obtained one factor with eigenvalues greater than or equal to the unit for all the items in total, comprising the construct on each of the dimensions/sub-dimensions. Additionally, the commonalities between variables and factors are also high (all their values are greater than 0.5), which indicates that these explain a high percentage of their variability. Furthermore, the rotated factor matrix was obtained using varimax normalisation. Finally, the factor score coefficient matrix was obtained on which the creation of weighted indices to be considered in the regression analysis was established (see Annex I). Table 10 shows the results of the multiple regression analysis using factor scores as variables, which indicate that the final model can explain 35.4% of data quality results.

Five models were run. In model 1 (column 3, Table 10), the control variables were considered. In model 2 (column 4, Table 10), the information dissemination variable was also incorporated. In model 3 (column 5, Table 10), the support resources variable was also incorporated. In model 4 (column 6, Table 10), the macro-level and micro-level institutionalisation variables were also incorporated. In the last model, model 5 (column 7, Table 10), the leadership variable was also incorporated.

For the validation of the models, a specification test was used to check for violations of the ordinary least squares (OLS) model assumptions: the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test for heteroskedasticity and the Ramsey RESET test for omitted variables. The overall significance of the model was tested through the F-test. The Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test revealed heteroskedastic results. To address the possibility of heteroskedasticity in the models and to have more robust results, the Huber-White sandwich correction was employed to adjust standard errors of regression coefficients and corresponding t-statistics. The Ramsey RESET test, which was performed for the models’ specifications, indicated that the models have no omitted variables. Moreover, the models were globally significant at the 1% level.

Using the global empirical model of multiple regression (column 7, Table 10), it was possible to statistically confirm the following hypotheses: H1—the dissemination of information positively influences data quality, H2—support resources positively influences data quality and H3—macro-level institutionalisation positively influences data quality. The micro-level institutionalisation and leadership variables were not considered significant, so hypotheses H4 and H5 were not confirmed (β4 = 0.056; p-value = 0.506 and β5 = − 0.112; p-value = 0.124, respectively). The adjusted coefficient of determination R2 explains 35.4% of the variance of data quality as a function of the other variables when they act together in the model. It is noteworthy that support resources (β2 = 0.368; p-value = 0.000) and information dissemination (β1 = 0.192; p-value = 0.002) are the variables that most contributed to explaining data quality. Regarding the control variables, the gender (female) variable and the seniority variable have a significant negative relationship (with a significance level of 10%) with data quality and legal form (indirect administration-autarchy) has a significant positive relationship (with a significance level of 10%) with data quality.

Discussion of results

The results confirm that data quality is positively influenced by the dissemination of information and the characteristics of data governance, namely support resources and institutionalisation at the macro level, confirming hypotheses H1, H2 and H3. It indicates that the variety of instruments to publicise open data (improving its availability and usability) increases users’ access and contributes to the quality of the data. These results are similar to previous studies that found a positive relationship between data dissemination and data quality (Yang and Wu, 2021; Dawes et al., 2016; Wang and Shepherd, 2020). Open government data can and should be disseminated through various activities that promote citizen participation, such as contests, workshops, training and public hearings (Attard et al., 2015; Johansson et al., 2021; Yang and Wu, 2021). According to the study carried out by Safarov (2019) and Wang and Shepherd (2020), this is effective in improving data quality. In addition, high data quality contributes to the transparency efforts of open data portals, which enables organisations and end users to make well-informed decisions. Although the organisations that integrate the open data portals publish data on their websites through existing institutional communication mechanisms, only a minority use initiatives that promote citizen participation and collaboration.

The results also show the contribution of data governance to and the relevance of support resources and tools for data quality confirming previous studies (Alexopoulos et al., 2015; Robinson and Scassa, 2022; Ruijer et al., 2020). Those factors connected to support resources and institutionalisation at the macro level have a positive effect on open data quality. This result is similar to the studies of Adamczyk et al. (2021) and Kawashita et al. (2022) which highlighted the importance of the institutionalisation of open data governance. Furthermore, the availability of resources to use more technology in the dissemination processes, the allocation of human resources to manage open data and the creation of an organisational unity responsible for open data management seem to have a greater influence on open data quality. This confirms the results of previous studies on open data governance (Ruijer et al., 2020; Alexopoulos et al. 2015; Alzamil and Vasarhelyi, 2019).

The empirical model did not confirm the positive influence of leadership on data quality and programme success. Previous studies point out the role of leaders in mobilising tangible and intangible resources, contributing to the success of open data projects and high-quality data (Kim and Eom, 2019; Ruijer and Meijer, 2020; Wang and Lo, 2016). In the case of Brazil leadership in open data programmes seems to be limited to the formalism of approving plans and communicating with managers. The results indicate little recognition of the direct action of top management both in driving and motivating the employees involved in these initiatives.

The control variables related to indirect administration-autarchy organisations had a positive relationship with data quality. Perhaps the autonomy of these organisations pressures them to disseminate quality open data to legitimise their activities among citizens and other interested parties. Finally, gender and seniority variables had a negative relationship with data quality. This result suggests that women and junior staff have a negative opinion about data quality, which could be an interesting aspect to explore for future studies.

In brief, open data programmes are properly institutionalised. There is usually a unit and team responsible for the open data programme and its governance. The survey results also indicate that citizen participation in the open data structure is reduced even though (according to Johansson et al., 2021; Ubaldi, 2013; Wang and Shepherd, 2020) it should be encouraged. Regarding data processing processes, these are present in citizen requests, data selection and quality control. However, data extractions are not completely automated, which can compromise the results of the programmes (Hartog et al., 2014; Robinson and Scassa, 2022). Open data information is available and known by those involved in its disclosure. Regarding the budget allocated to this activity, the analysis indicates that only a small number of respondents consider it adequate. It should be noted that, according to Attard et al. (2015) and Kim and Eom (2019), an adequate budget is necessary for the preparation and dissemination of data. Overall, however, data published on open data portals meet basic quality requirements, namely in terms of format, transparency and metadata.

Conclusion

This study sought to analyse whether the instruments and practices used in open data portals were able to promote data quality. Extant literature emphasised that open data programmes and the adoption of open data principles in the management of open data portals contribute to the success of open data portals (Robinson and Scassa, 2022).

It can be concluded that the quality of data published on the open data portal is positively influenced by information dissemination and data governance factors. Among the data governance factors, the allocation of support resources and institutionalisation at the macro level has a particularly strong influence. This is in line with previous studies that argue that the lack of supporting resources and institutionalisation influence the success of implementing open data portals. (Adamczyk et al., 2021; Kawashita et al., 2022; Ruijer et al., 2020). The study confirms that the existence of a stable organisational unit and the availability of resources (human and financial) are requirements to positively influence the quality of open data.

The study identifies three aspects that contribute to improving open data quality in open data portals and the dissemination of information. The importance of citizen participation through different electronic government and electronic participation instruments that facilitate interaction with end users and society for the quality of open data (Yang and Wu, 2021). The need to provide organisations with the necessary resources for activities related to the dissemination of open data (Robinson and Scassa, 2022). Promoting the participation and involvement of staff working on data dissemination. As other studies have found (Johansson et al., 2021; Kim and Eom, 2019; Robinson and Scassa, 2022; Ruijer et al., 2020; Ubaldi, 2013; Wang and Lo, 2016), these are important characteristics for open data quality.

The study contributes to the existing literature related to open data portals by focusing on instruments and practices that promote data quality. The research demonstrated theoretically and empirically that the dissemination of information and the characteristics of data governance influence open data quality. It broadens the knowledge from previous studies about open data by identifying the most relevant management practices associated with the quality of open data.

This study has practical implications for open government data managers and practitioners in several aspects, including those related to awareness of open data portals’ usability. Government agencies seeking to stimulate development should consider the instruments and data governance practices for disseminating data and making users aware of its availability, as well as facilitating user engagement with these resources. Through open data portals, government agencies and managers could highlight features and functionality of open data resources that correspond with different needs as a means of attracting potential data users. Government agencies should seek to provide a wide range of features for open data users at different points in their user experience and different levels of expertise to increase awareness about the available features at other levels of engagement that may attract users to open data, for instance, by optimising the usability of their open data portals, the crucial gateway into the actual open data sets themselves.

This paper has several limitations. The study was designed to analyse open data management and practices that contribute to the quality of data disseminated on open data portals. However, open data programmes are complex and dependent on several other factors influencing data quality and the success of these programmes that were not considered here. Other studies could deepen the analysis by considering variables like the influence of organisational culture and data protection legislation. The research was carried out from the point of view of management staff involved in data processing and the dissemination of data in organisations using open data portals. Other studies could analyse data quality from the perspective of end users who use government data for research or decision-making. The perspective of these actors on data quality can contribute to improving the quality of disclosure and transparency. Finally, data quality was assessed through a survey based on respondents’ perceptions, and not through direct analysis of published data.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the DataReporitoriUM repository, https://doi.org/10.34622/datarepositorium/HXKX8C.

References

Adam IO (2020) Examining E-Government development effects on corruption in Africa: the mediating effects of ICT development and institutional quality. Technol Soc 61:101245

Adamczyk WB, Monasterio L, Fochezatto A (2021) Automation in the future of public sector employment: the case of Brazilian Federal Government. Technol Soc 67:101722

Alexopoulos C, Loukis E, Mouzakitis S, Petychakis M, Charalabidis Y (2015) Analysing the characteristics of open government data sources in Greece. J Knowl Econ 9(3):721–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-015-0298-8

Alzamil ZS, Vasarhelyi MA (2019) A new model for effective and efficient open government data. Int J Discl Gov 16:174–187. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41310-019-00066-w

Ansari B, Barati M, Martin EG (2022) Enhancing the usability and usefulness of open government data: a comprehensive review of the state of open government data visualization research. Gov Inf Quart 39(1):101657

Attard J, Orlandi F, Scerri S, Auer S (2015) A systematic review of open government data initiatives. Gov Inf Quart 32(4):399–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.07.006

Badiee S, Crowell J, Noe L, Pittman A, Rudow C, Swanson E (2021) Open data for official statistics: History principles and implementation. Stat Jour IAOS 37(1):139–159. https://doi.org/10.3233/SJI-200761

Begany GM, Martin EG (2020) Moving towards open government data 2.0 in U.S. health agencies: engaging data users and promoting use. Inf Pol 25(3):301–322

Begany GM, Gil-Garcia R (2021) Understanding the actual use of open data: levels of engagement and how they are related. Telem Inf 63:101673

Berners-Lee T (2006) Linked Data 5 star model. W3C. https://www.w3.org/DesignIssues/LinkedData.html. Accessed 12 Jan 2023

Borycz J, Olendorf R, Specht A, Grant B, Crowston K, Tenopir C, Sandusky RJ (2023) Perceived benefits of open data are improving but scientists still lack resources, skills, and rewards. Hum Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01831-7

Cantador I, Cortés-Cediel ME, Fernández M (2020) Exploiting Open Data to analyze discussion and controversy in online citizen participation. Inf Proc Manag 57(5):102301

Controladoria Geral da União (2004) Portal da Transparência. Portal Da Transparência Na Internet. https://www.portaltransparencia.gov.br/sobre/o-que-e-e-como-funciona. Accessed 15 Dec 2022

Controladoria Geral da União (2016) Sobre Dados Abertos. https://dados.gov.br/pagina/sobre. Accessed 15 Dec 2022

Controladoria Geral da União (2020) Manual de Elaboração de Planos de Dados Abertos (PDAs). https://www.gov.br/cgu/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/transparencia-publica/arquivos/manual-pda.pdf. Accessed 15 Dec 2022

Controladoria Geral da União (2021) Painel de Dados Abertos CGU. Site https://dados.gov.br/dataset/painel-de-monitoramento-de-dados-abertos. Accessed 15 Dec 2022

Crosby P (1987) Quality process improvement management college. Philip Crosby Associates, San Jose

Cumbie BA, Kar B (2016) A study of local government website inclusiveness: the gap between e-government concept and practice. Inf Technol Dev 22(1):15–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2014.906379

Dawes SS, Vidiasova L, Parkhimovich O (2016) Planning and designing open government data programs: an ecosystem approach. Gov Inf Quart 33(1):15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.01.003

Ehrlinger L, Wöß W (2022) A survey of data quality measurement and monitoring tools. Front Big Data 28(5):1–30. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2022.850611

Gascó-Hernández M, Martin EG, Reggi L, Pyo S, Luna-Reyes LF (2018) Promoting the use of open government data: cases of training and engagement. Gov Inf Quart 35(2):233–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2018.01.003

Hartog M, Mulder B, Spée B, Visser E, Gribnau A (2014) Open data within governmental organisations. EJ EDemo Open Gov 6(1):49–61. http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=tsh&AN=99675140&site=ehost-live Accessed 19 Feb 2023

Huang L, Li OZ, Yi Y (2021) Government disclosure in influencing people’s behaviors during a public health emergency. Hum Soc Sci Commun 8(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00986-5

Issa T, Isaias P (2016) Internet factors influencing generations Y and Z in Australia and Portugal: a practical study. Inf Proc Manag 52(4):592–617

Janssen M, Brous P, Estevez E, Barbosa LS, Janowski T (2020) Data governance: organizing data for trustworthy Artificial Intelligence. Gov Inf Quart 37(3):101493

Johansson JV, Shah N, Haraldsdóttir E, Bentzen HB, Coy S, Kay J, Mascalzoni D, Veldwijk J (2021) Governance mechanisms for sharing of health data: an approach towards selecting attributes for complex discrete choice experiment studies. Technol Soc 66:101625

Johnson N, Turnbull B, Reisslein M (2022) Social media influence, trust, and conflict: an interview-based study of leadership perceptions. Technol Soc 68:101836

Juran JM, Gryna FM, Bingham RS (1974) Quality control handbook. McGraw Hill, New York

Kassen M (2019) Open data and e-government—related or competing ecosystems: a paradox of open government and promise of civic engagement in Estonia. Inf Technol Dev 25(3):552–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2017.1412289

Kawashita I, Baptista AA, Soares D (2022) Open government data use by the public sector—an overview of its benefits, barriers, drivers, and enablers. In Proceedings of the 55th Hawaii international conference on system sciences- HICSS: 2533–2542. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/79648. Accessed 15 Jan 2023

Kim JM, Eom SJ (2019) The managerial dimension of open data success: focusing on the open data initiatives in Korean local governments. Sustainability 11(23):6758. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236758

Kučera J, Chlapek D, Nečaský M (2013) Open government data catalogs: current approaches and quality perspective. In: Proceedings of the technology-enabled innovation for democracy, government and governance: second joint international conference on electronic government and the information systems perspective, and electronic democracy, EGOVIS/EDEM 2013. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-40160-2_13. Accessed 15 Jan 2023

Kundra V (2011) Vivek Kundra’s Ten Principles for Improving Federal Transparency. Sunlight Foundation. https://sunlightfoundation.com/2011/07/14/vivek-kundras-10-principles-for-improving-federal-transparency/. Accessed 15 Jan 2023

Likert R (1932) A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psych 22:140

Lourenço RP (2015) An analysis of open government portals: a perspective of transparency for accountability. Gov Inf Quart 32(3):323–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.05.006

Luna-Reyes LF, Harrison TM, Styrin E (2016) Open data and open government: from abstract principles to institutionalized practices. In: Proceeding of the 17th international digital government research, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1145/2912160.2912161. Accessed 15 Jan 2023

Malamud C, O’Reilly T, Elin G, Sifry M, Holovaty A, O´Neil DX, Migruski M, Allen S, Tauberer J, Lessig L, Newman D, Geraci J, Bender E, Steinberg T, Moore D, Shaw D, Needham J, Hardi J, Zuckerman E, Swartz A (2007) Open government data principles. open government data principles. https://opengovdata.org/. Accessed 15 Jan 2023

Matheus R, Janssen M (2020) A systematic literature study to unravel transparency enabled by open government data: the window theory. Public Perform Manag Rev 43(3):503–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1691025

Nikiforova A, McBride K (2021) Open government data portal usability: a user-centred usability analysis of 41 open government data portals. Telemat Inform 58:101539

Open Knowledge Foundation (2017) Open definition. Open Knowledge Foundation. http://opendefinition.org/. Accessed 15 Jan 2023

Park S, Gil-Garcia JR (2022) Open data innovation: visualizations and process redesign as a way to bridge the transparency-accountability gap. Gov Inf Quart 39(1):101456

Presidência da República (1988) Constituição Federal do Brasil. Diario Oficial Da União. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm. Accessed 15 Jan 2023

Presidência da República (2011) Lei de Acesso à Informação. Diario Oficial Da União, 1–13

Presidência da República (2016) Decreto 8.777 de 2016. Diario Oficial Da União. https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2016/decreto/D8777.htm. Accessed 15 Jan 2023

Public Sector Transparency Board (2012). Public data principles. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/665359/Public-Data-Principles_public_sector_transparency_board.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2023

Robinson P, Scassa T (2022) The future of open data. University of Ottawa Press, Ottawa

Rong G, Grover V (2009) Keeping up-to-date with information technology: testing a model of technological knowledge renewal effectiveness for IT professionals. Inf Manag 46(7):376–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2009.07.002

Ruijer E, Détienne F, Baker M, Groff J, Meijer AJ (2020) The politics of open government data: understanding organizational responses to pressure for more transparency. Am Rev Public Admin 50(3):260–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074019888065

Ruijer E, Meijer A (2020) Open government data as an innovation process: lessons from a living lab experiment. Public Perform Manag Rev 43(3):613–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1568884

Ruijer E, Grimmelikhuijsen S, Meijer A (2017) Open data for democracy: developing a theoretical framework for open data use. Govt Inf Quart 34(1):45–52

Safarov I (2019) Institutional dimensions of open government data implementation: evidence from the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK. Public Perform Manag Rev 42(2):305–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2018.1438296

Saxena S (2018) Drivers and barriers towards re-using open government data (OGD): a case study of open data initiative in Oman. Foresight 20(2):206–218. https://doi.org/10.1108/FS-10-2017-0060

Styrin E, Luna-Renyes L, Harrisson TM (2017) Transforming government: people, process, and policy. University of Newcastle, pp 5–6

Tai K (2021) Open government research over a decade: a systematic review. Gov Inf Quart 38(2):101566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2021.101566

Talukder MdS, Shenb L, Talukder MdFH, Bao Y (2019) Determinants of user acceptance and use of open government data (OGD): an empirical investigation in Bangladesh. Technol Soc 56:147–156

Tejedo-Romero F, Araujo JFFE (2018) Transparency in Spanish municipalities: determinants of information disclosure Convergencia, 153–174. https://doi.org/10.29101/crcs.v25i78.9254

Tejedo-Romero F, Araujo JFFE (2023) Critical factors influencing information disclosure in public organisations. Hum Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01814-8

Tejedo-Romero F, Araujo JFFE, Tejada A, Ramírez Y (2022) E-government mechanisms to enhance the participation of citizens and society: exploratory analysis through the dimension of municipalities. Technol Soc 70:101978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101978

Ubaldi B (2013) Open government data: towards empirical analysis of open government data initiatives. OECD Work Pap Public Gov 22(22):61. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k46bj4f03s7-en

United Nations (2020) E-Government Survey 2020—Digital Government in the decade of action for sustainable development: with addendum on COVID-19 response. https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/Reports/UN-E-Government-Survey-2020. Accessed 15 November 2022

van Ooijen C, Ubaldi B, Welby B (2019) A data-driven public sector: enabling the strategic use of data for productive, inclusive and trustworthy governance, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 33, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/09ab162c-en

Vetrò A, Canova L, Torchiano M, Minotas CO, Iemma R, Morando F (2016) Open data quality measurement framework: definition and application to Open Government Data. Gov Inf Quart 33(2):325–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.02.001

Wang HJ, Lo J (2016) Adoption of open government data among government agencies. Gov Inf Quart 33(1):80–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.11.004

Wang V, Shepherd D (2020) Exploring the extent of openness of open government data—a critique of open government datasets in the UK. Gov Inf Quart 37(1):101405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.101405

Yang TM, Wu YJ (2016) Examining the socio-technical determinants influencing government agencies’ open data publication: a study in Taiwan. Gov Inf Quart 33(3):378–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.05.003

Yang TM, Wu YJ (2021) Looking for datasets to open: an exploration of government officials’ information behaviors in open data policy implementation. Gov Inf Quart 38(2):101574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2021.101574

Zhang Y, Kimathi FA (2022) Exploring the stages of E-government development from public value perspective. Technol Soc 69:101942

Zuiderwijk A, Janssen M (2014) Open data policies, their implementation and impact: a framework for comparison. Gov Inf Quart 31(1):17–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.04.003

Zuiderwijk A, Pirannejad A, Susha I (2021) Comparing open data benchmarks: which metrics and methodologies determine countries’ positions in the ranking lists? Telemat Inform 62:101634

Zuiderwijk A, Reuver MD (2021) Why open government data initiatives fail to achieve their objectives: categorizing and prioritizing barriers through a global survey. Transform Gov People Process Policy 15(4):377–395

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted at the Research Center in Political Science (UIDB/CPO/00758/2020), University of Minho/University of Évora and supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and the Portuguese Ministry of Education and Science through national funds and partially funded by the University of Castilla-La Mancha Research Plan in the call for research stays at universities and research centres abroad, BDNS (Identif.): 596086 [2021/12543].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FTR: Conception and design of study, revising theoretical framework, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual contents. Approval of the version of the manuscript to be submitted. JFFEA: Revising theoretical framework, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual contents. Approval of the version of the manuscript to be submitted. MJGR: Conception and design of study; acquisition of data; revising theoretical framework; drafting the manuscript; interpretation of data. Approval of the version of the manuscript to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The Social Research Ethics Committee (SREC) of the University of Castilla-La Mancha issued a waiver confirming that all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations (e.g. Declaration of Helsinki or similar). According to the policy of the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Castilla-La Mancha the study did not require approval from the SREC.

Informed consent

Prior to participation, informed consent was provided electronically via Qualtrics software at the start of the survey. They were informed about the study’s purpose and the voluntary nature of their participation and assured that their responses would remain anonymous and used solely for academic and scientific purposes. No incentives were offered.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tejedo-Romero, F., Ferraz Esteves Araujo, J.F. & Gonçalves Ribeiro, M.J. The usability of Brazilian government open data portals: ensuring data quality. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 297 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04404-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04404-y