Abstract

The article provides an overview of the translation and reception of contemporary Chinese literature in the Portuguese-speaking world, shedding light on the dynamics of cross-cultural literary exchange and reader engagement. It presents the extent, diversity, and marketing ratio of Chinese literary works translated into Portuguese, and utilizes this information to investigate how Portuguese-speaking readers engage with these translated works, focusing on their preferences, interests, demographics, and the impact of linguistic backgrounds. It then analyzes the reviews of well-received translations, including the Three-Body Problem trilogy, Iron Widow, and The Good Women of China, to determine how Portuguese-speaking readers interpret Chinese elements, historical references, narrative styles, and themes. The findings indicate the formation of the overarching impression of the ‘Chinese’ image among Portuguese-speaking readers and the potential development of the stereotypical views of Chinese women. Additionally, the study reveals that the exploration of fantasy as a universal passion underscores shared experiences that transcends cultural boundaries, connecting readers in China to those in the Portuguese-speaking world. The study highlights the challenges faced by Portuguese-speaking readers in understanding the intricacies of Chinese contexts, emphasizing the need for more detailed depiction and contextual understanding of translations. The article concludes by calling for further research on translation strategies, reader engagement, and shifts within literary systems to enhance cross-cultural literary exchange.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In an era marked by unprecedented global connectivity and cross-cultural exchange, literary translation increasingly serves as a pivotal bridge between diverse societies and languages. Early cultural exchanges often manifested through artistic form. For example, Chinese workers and artists were present in Brazil as early as the 17th century (Leite 1999), and artistic works dating from their Baroque period feature Chinese motifs, themes, and styles in their paintings and sculptures, especially in the churches in Minas Gerais. Similarly, the Shanshui motif from Chinese porcelain is integrated into early examples of Portuguese faience (Guo and Min 2022). Early Portuguese literature depicted China and Macau in contrasting ways: as ancient and rich civilizations; or as impoverished, uncivilized regions (Yuan 2024; Zhong 2022). Chinese migrants were often labeled as ‘coolies’ or the ‘yellow race’, and portrayed through such dehumanizing stereotypes as primates, ants, shrimp peddlers, or mandarins (Lee 2020). Chinese women, however, were often depicted as beautiful and mysterious, navigating “between beauty and negativity” (Zhong 2022). These early cultural products exemplify the initial stages of cross-cultural communication, characterized by imagination, partial understanding, and idealization.

Unfortunately, the Portuguese media continues to transmit and perpetuate stereotypes and prejudices about China and the Chinese (Costa and Peixoto 2021). The Chinese government recognized the importance of expanding its media influence abroad and launched the ‘media going-out’ policy as part of its broader effort to build ‘soft power’ (Thussu, De Burgh and Shi 2018). Despite the widespread recognition of Chinese cultural elements such as traditional medicine (Zheng, Lyu, Lu, Hu and Chan 2021), kung fu (Frosi, Maidana and Mazo 2011), and cuisine (Minnaert 2018) in Portuguese-speaking countries like Brazil, the Chinese media has struggled to effectively engage these audiences. While the China Global Television Network (CGTN) broadcasts in Spanish and French to reach its international audiences, it has not yet launched a dedicated Portuguese-language channel (Ye and Albornoz 2018). As a result, there is very limited literature on the influence of Chinese media in Portuguese-speaking countries.

As the influence of Chinese media remains constrained, translated literature has emerged as a crucial avenue for Portuguese-speaking audiences to engage more deeply with Chinese culture. In the Portuguese-speaking world, there has been a notable increase in the translations of Chinese literary works, which potentially offer more faithful reflections of Chinese culture. Historically, both Chinese and Portuguese have been considered peripheral languages (Heilbron 1999) compared to English and French. However, since China’s reform and opening up policy began in 1979, the translation and dissemination of Chinese literature into many languages, including Portuguese, have gained momentum, significantly contributing to the introduction of Chinese culture to Portuguese-speaking readers and fostering deeper mutual understanding. This burgeoning role prompts the necessity for further research in this area to fully grasp the complexities of the global landscape of world literature dissemination.

Several pioneering efforts have delved into the translation of Chinese literature into Portuguese, directing attention to individual translators and the impact of specific works. For instance, L. Li (2023) examines the early translations of Chinese literature by Joaquim Afonso Gonçalves, discussing the challenges and strategies of these initial cross-cultural exchanges. Pinto (2013) analyzes Feijó’s Cancioneiro Chinez, which effectively introduced Portuguese audiences to classical Chinese poetry by blending French literary influences with oriental aesthetics. S. Wang (2019) explores the role of literary translation in shaping revolutionary narratives between China and Brazil during the cultural cold war; Zhou (2019) investigates the translation of the novel O Assassino, comparing culture-specific concepts in direct and indirect translations; Sinedino (2023) addresses the difficulties in translating Chinese classical literature; and Bernardo (2022) discusses the translation of contemporary poetry.

Three pieces of research emerge as especially noteworthy. Schmaltz (2013) provides a historical overview of Sino-Portuguese translation, from early interactions to the influence of political movements on translation practices. Yao (2021) explores the nuances of translating Chinese literature into Portuguese, emphasizing Macau’s role as a translation hub and the challenges translators face in capturing the essence of Chinese poetry, and addresses the selection criteria used by Chinese publishers. Zhou (2023) examines selected translations of contemporary Chinese literary works into Portuguese, discussing the structural issues of translated works relative to social fields. However, their research provides specific insights rather than offering a comprehensive overview.

A comprehensive overview entails not only examining the quantity, variety, and trends of Chinese literature translated into Portuguese, but also delving into the crucial aspect of ‘reader reception’ theory. This includes conducting surveys and analyses to understand the demographics of the readership and their preferences. Such a comprehensive approach to translation research echoes the recent emphasis on reader reception in translation studies, a paradigm shift that originated from literary criticism scholars Hans-Robert Jauss (1982a, 1982b) and Stanley Fish (1973), whose concept of ‘interpretive community’ addresses the collective nature of interpretation and the role of social experiences and identities in shaping meanings derived from literary texts.

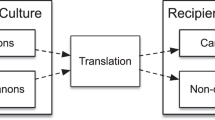

Reader reception has played a transformative role within the field of translation studies (Brems and Ramos Pinto 2013; Chan 2016) by reevaluating translation as a product of the target context, moving away from a linguistic-oriented approach focused on equivalence (Nida 1964) and comparative analysis (Catford 1965) between source and target texts. Instead, there is a growing emphasis on studying the role of translation and its impact on identity formation and dynamics within the target culture. Descriptive translation studies have contributed significantly to this perspective. By examining translation from a socio-cultural standpoint, with an emphasis on the functioning of translated texts within the target culture, the literary translation ‘polysystem’ theory examines the process of introducing cultural products in translation from one culture into another, primarily exploring the factors that influence whether the translated texts and authors occupy central or peripheral positions within the receiving culture (Even-Zohar 1978a).

To study the reception of translated literature among actual readers, both historical and empirical approaches are required. The historical approach entails the examination of archival materials and personal anecdotes related to individuals’ responses to translated literary works. For example, Qi (2023) presents an account where the source text readers became the online censors for the receivers of translated texts. Also working online, Chen (2023) quantifies the readers’ comments on internet forums to delve into the dynamics between readers and translators, scrutinizing the reception of White’s Charlotte’s Web in China.

Conversely, the empirical approach emphasizes the investigation of real, individual readers’ responses through systematic data collection methods such as questionnaires, interviews, and more specialized techniques like eye-tracking and interactive tasks (Brems and Ramos Pinto 2013). For example, Cussel (2024) utilizes focus groups and questionnaires to explore the varied interpretations of translated texts among readers from diverse cultural backgrounds, offering insights into the challenges and cultural influences shaping reader reception. Studies by Farghal and Al‐Masri (2000) employ open- and closed-form questionnaires to analyze English readers’ understanding to translated Quranic verses. Chesnokova et al. (2017) similarly employed a questionnaire containing a 15-item semantic differential scale to assess the responses of Brazilians and Ukrainians to Poe’s The Lake, revealing that while the initial responses to the poem are mainly determined by cultural factors, its translation also affects their reactions.

Chan (2022) investigates readers’ interactions regarding the translation of Murakami’s Norwegian Wood on the internet and argues for the importance of locating the ‘real’ readers. F. Wang and Humblé (2020) employ corpus linguistics and stylistic perception analysis to compare reader comments on Anthony Yu’s two translations of Wu Cheng’en’s The Journey to the West, thus providing nuanced insights into stylistic preferences and reader perceptions of translated texts.

With the rise of cognitive perspective in translation studies, behavior observation has become popular for investigating reader response. Walker’s (2021) book uses eye-tracking to compare reader experiences of Queneau’s Zazie dans le Métro and its English translation. This method integrates principles and methods from various fields, earning commendation for its comprehensive approach.

While this literature review has illuminated the vibrant discourse surrounding translation studies and reader reception on the translation of languages playing “hyper-central” or “central” roles (Heilbron 1999), it also reveals a notable gap in our understanding: the reception of Chinese literature translated into Portuguese. This study aims to address this by being the first to investigate the readership within this specific academic context. Our research questions include:

-

1.

What is the significance of the types and quantities of Chinese literary works that are translated into Portuguese?

-

2.

What are the preferences, interests, and demographics of the Portuguese-speaking readers of translated Chinese texts, and how does their language background influence the way they engage with the texts?

-

3.

How do Portuguese-speaking readers interpret Chinese elements, historical references, narrative styles, and themes in the most popular Chinese literary works translated into Portuguese and what are the outcomes?

This exploration will shed light on the nuanced interplay between languages, cultures, and literature, ultimately fostering a deeper appreciation for the resonance of Chinese contemporary literature in the Portuguese-speaking world.

Methodology

From June to December 2022, a survey project was undertaken to compile a comprehensive list of Chinese literature translated into Portuguese, which was updated in April 2024 before submission. Chinese literature in our project refers to the literary works authored by individuals of Chinese origin and characterized by thematic, linguistic, and cultural elements originating from China. We utilized Octoparse, a visual web crawling tool that simulates human browsing behavior, to extract structured data on translated Chinese literature from a range of publicly available sources, including Goodreads (www.goodreads.com), Amazon Brazil (www.amazon.com.br), Skoob (www.skoob.com.br), Wook (www.wook.pt), and the WorldCat library catalog database (http://search.worldcat.org).

The data extracted from each book entry included: information on the author, translator, editor, sales ranking, year of publication, publisher, price, book dimensions, ISBN, ratings, number of ratings, gender of the readers, number of comments, and the comments themselves. Reader gender data, obtained from Skoob, one of the most prominent literary platforms in Brazil, categorized users as male or female based on the platform’s registration details. The homepage of each book in Skoob publicly displays the gender distribution of users who rated it. While non-binary identities were not represented due to platform limitations, the dataset offers valuable insights into reader demographics. Age-related insights were inferred from genre classifications on Amazon, such as the categorization of Iron Widow under “Teen & Young Adult” genres, suggesting a target audience of readers aged 12 to 18. Goodreads, a global community of book lovers with readers writing reviews in more than 50 languages, provides data on the linguistic diversity of comments, with its review filter showing the language used in each review.

To ensure the credibility of the online reviews, we prioritized data from reputable platforms like Goodreads, Amazon Brazil, and Skoob, known for their robust review mechanisms. Recent studies, such as those by Bartl and Lahey (2023), Tselenti et al. (2024), and Silva and Curcino (2023), have utilized these platforms for reader response analysis. All collected entries were imported into an Excel spreadsheet, where each row corresponded to an individual book review. The columns contained the detailed attributes of each review (e.g., reviewer details, review content, and associated metadata). Each row was carefully examined to eliminate duplicates using Excel’s automated “Remove Duplicates” function. User activity and history were examined, with more credit given to reviewers with established profiles and consistent reviewing patterns. Longer reviews were favored for their depth and insight. The review texts were organized and stored in various corpus formats, including plain text (TXT) files, for further analysis.

Translation of Chinese Literature into Portuguese

Translation quantity and ratio

Through our data collection efforts, we identified a total of 274 Chinese literary works translated into Portuguese on the platforms. They encompass a wide range of genres and formats and each record was uniquely identified by its ISBN. The data shows significant growth in the translation of Chinese literature into Portuguese, with a notable surge after the initiation of China’s reform and opening-up policy in 1979. There were 255 literary works identified between 1979 and April 2024, including printed books, e-books, and illustrated books. Almost all have been published by Portuguese or Brazilian publishers, indicating they are treated as commercialized commodities subject to market scrutiny.

Based on our data, out of the total of 274 works, nearly half consists of translations of classical Chinese antiquity. Among these, translations of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War account for 29.56%, Tao Te Ching for 10.95%, and The Analects of Confucius for 5.11%. The remainder includes translations of contemporary mainland Chinese novels (15.69%), contemporary works by overseas Chinese (14.96%), classical poems and ancient stories (11.31%), modern Chinese essays and poems (4.38%), and Hong Kong and Macau literature (2.92%). In addition to the Tao Te Ching, other Taoist works represent 1.82% of the total; and excluding The Analects of Confucius, Confucian works represent 0.73% of the total. The rest consists of comic stories (1.09%) and other categories (1.46%).

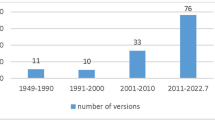

There is an increasing consumption within the Portuguese-speaking world of the translation and assimilation of Chinese literature from 1979 to April 2024, with an annual increase of 32% (see Fig. 1). The evolution unfolds in three discernible phases. The initial phase (pre-2003) centered on classical Chinese literature, introducing renowned poets like Li Bai, Du Fu, and philosophical texts such as the Tao Te Ching. The yearly growth was moderate, with sporadic releases of translations. The subsequent phase (2004–2011) marked a significant increase in translations, encompassing works by contemporary mainland and overseas Chinese authors. This period witnessed a notable annual growth, indicating a growing appetite for a diverse range of Chinese literary genres. The final phase (2012-present) witnessed an unprecedented surge, coinciding with Mo Yan’s Nobel Prize award. The growth reached its peak during this phase, emphasizing the profound impact of accolades and global recognition on the translation landscape.

Popularity of contemporary novels

Of the Chinese literary works translated into Portuguese, recent years have witnessed a drastic increase in contemporary Chinese texts; that is, those written after 1949. 84 contemporary Chinese novels have found their way into Portuguese translation including 43 by Chinese mainland authors such as Liu Cixin, Su Tong, Yan Lianke, Mai Jia, Yu Hua, and Chen Zhongshi. Some works have multiple versions, showing the evolving landscape of Chinese literature in the Portuguese-speaking world. For instance, Liu Cixin’s science fiction masterpiece, O Problema dos Três Corpos: 1 (The Three-Body Problem), was initially translated into English and then translated into Portuguese by a Brazilian translator, Leandro Alves, in 2016. In 2021, the same work received a direct translation by Portuguese translator, Telma Carvalho, courtesy of the Portuguese publisher Relógio D’a Água. Similarly, Yu Hua’s novel Chronicle of a Blood Merchant witnessed two distinct version, translated from English and Chinese, respectively. His two Portuguese versions of To Live, while both translated directly from Chinese to Portuguese, differed. One was crafted by Brazilian sinologist and translator Márcia Schmaltz in 2008, the other by Portuguese translator Tiago Nabais in 2018. (Notably, Nabais has translated several other novels by Yu Hua, including China em Dez Palavras (China in Ten Words).) The Portuguese version of Chen Zhongshi’s In the Land of White Deer marks the first substantial international debut of this Chinese novel in the global market, particularly in the Americas, and serves as a prime example of an emergence from a peripheral zone as, prior to this, there was no English version available. This evolving landscape indicates the dynamics of the international translation system: the increasing global communication enables interactions among peripheral or semi-peripheral regions, thereby encouraging direct translations among these languages. Brazil could potentially emerge as a significant cultural hub in the global dissemination of literary works.

In the realm of contemporary novels, there is a near-equivalent presence on the market by the novels of overseas Chinese authors. These works, predominantly authored in English or French and subsequently translated into Portuguese, account for 41 instances in this study. Notable among them are Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China by Jung Chang, Balzac and the Little Seamstress by Dai Sijie, and Iron Widow by Xiran Jay Zhao. While Xiran Jay Zhao told a story about imaginative historical China, Jung Chang and Dai Sijie’s works are set against the backdrop of modern Chinese political movements or significant upheavals. They have garnered a substantial number of ratings and comments on book platforms, indicating readers’ profound interest in the historical, cultural, or feminist perspectives these novels offered. The success of Xiran Jay Zhao’s novels can also be attributed to the cumulative impact of effective social media marketing, particularly on platforms like TikTok.

The Portuguese-speaking readership

General preference and interest

Our project identifies the Portuguese-speaking readers by language in Goodreads, Amazon Brazil, and Skoob. The general preferences observed in the ratings and reader engagement for translated Chinese literature in Portuguese is presented in Table 1. The engagement metrics on book platforms are measured through three key indicators: stars, representing the average rating; ratings, indicating the number of individuals who rated the book; and reviews, reflecting the number of individuals who provided written feedback. Collectively, these three metrics offer insight into the level of reader engagement and reception.

It is important to note that the comments for different formats of the same book, for example printed books and e-books, are often grouped together by the platforms, making it challenging to separate data based on the format. Despite this, we observed potential differences in reader engagement between formats. For instance, comments for e-books, particularly Kindle versions, tend to be more numerous but shorter, possibly influenced by mobile app usage habits. The book Iron Widow exemplifies this trend, with reviews reflecting the characteristics of e-book and online dissemination.

Table 1 illustrates the varied preferences of Portuguese-speaking readers for different novels within Chinese literature. The Three-Body Problem trilogy stands out prominently, achieving high scores and substantial participation on Amazon Brazil, Goodreads, and Skoob. Despite the official Portuguese release of the first book of the trilogy in 2016, readers had already begun sharing their reviews in Portuguese. The proactive engagement signifies an early interest and anticipation among readers, suggesting a readiness to engage with Chinese literature in various forms, whether through original language editions, or translations into other languages including, in this case, Portuguese. As of November 2022, data from the platforms we examined reveal a sustained and upward trend in readership and number of reviews. The novel’s popularity and reader involvement show no signs of waning. While the sales and reviews of The Dark Forest and Death’s End (the second and third books of the trilogy, respectively) may not match those of the first book, the cumulative impact of the trilogy, as subsequent volumes were published, has kept its popularity consistently high and continues to grow. Following the release of The Three-Body Problem animated series and TV show in China and the United States from December 2022, the number of ‘likes’ and ‘want to read’ ratings and reviews on various reading platforms is still on the rise. The success of this trilogy indicates a growing interest in Chinese science fiction literature, demonstrating that the themes and storytelling have resonated beyond cultural and linguistic boundaries.

Additionally, the positive reception extends to other works, as evidenced by the strong ratings and engagement for novels by other contemporary authors. This trend reflects a broader acceptance and appreciation among Portuguese-speaking readers for a diverse range of Chinese literary genres, including historical narratives, contemporary stories, and women’s writings. The data reflects an encouraging trajectory for the dissemination and reception of Chinese literature in the Portuguese-speaking literary landscape.

Reader profile

The readership profile of Chinese literature in Portuguese is multifaceted, encompassing diverse age groups and gender preferences. The intersection of gender, age, and linguistic dynamics contributes to a rich and evolving landscape of literary engagement among Portuguese-speaking readers.

The impact of gender on book selection is a nuanced aspect of the readership landscape. As shown in Fig. 2, while females show a preference for contemporary novels and works with women-centric themes, males exhibit sustained interest in technically-intricate narratives. The diversity in preferences portrays a broad acceptance and appreciation for various genres of Chinese literature among Portuguese-speaking readers.

According to Skoob, the majority of Chinese literature readers in Portuguese are female, ranging from 50% to 90%. They show a preference for contemporary novels, especially those written by female authors, that pinpoint themes and history related to Chinese women. Notable examples include The Iron Widow, The Good Women in China, Letters from an Unknown Mother, Wild Swans, Empress Dowager Cixi, and Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister, where the proportion of female readers is exceptionally high, ranging from 80% to 90%. Female readers are clearly driving the sales, especially for The Iron Widow and The Good Women in China where they constitute 89% of readership. Interestingly, even works authored by men, such as Chronicle of a Blood Merchant and To Live, maintain a predominantly female readership, ranging from 60% to 70%. Surprisingly, females (52%) also dominate readership of traditionally male-preferred works like The Art of War, in which the Portuguese translations emphasize practical applications.

While almost all translated texts we examined appealed to female readers, in the Three-Body Problem trilogy the dominant proportion of readership shifts to males for the second and third books. Since we cannot determine the gender of the reviewers, we cannot definitively ascertain why female readers did not continue with the second and third books of the trilogy. However, this nuanced shift may suggest that the trilogy’s thematic depth, artistic expression, and creativity continue to engage dedicated readers despite the change in the readership demographics.

The age distribution among readers exhibits distinct genre preferences, notably exemplified by The Iron Widow, strategically tailored for the young adult demographic aged 12 to 18. This demographic, commonly identified as the ‘Z-generation’, is characterized by seamless integration with digital technologies and active participation in social media platforms. Within the contemporary literary landscape, young adult readers, particularly females, manifest a fervent enthusiasm for reading coupled with adept utilization of social media, fostering a dynamic BookTok community. This community thrives on the enthusiastic exchange of book recommendations through engaging videos, discussions, and expressive dialogues. The thematic explorations in works such as The Iron Widow, delineating the transformation of a modest female protagonist into a formidable queen, effectively resonates with the prevailing ideals and aspirations of this age cohort. As noted by Baker (2014, p. 23), the impact of new media cultures on translation is among the most promising new lines of research, reflecting the evolving ways in which literature is consumed and disseminated.

In addition to gender and age, the linguistic background of readers also plays a crucial role in their engagement with Chinese literature. The prevalence of bilingual or multilingual backgrounds among global readers, particularly in English-dominant contexts, is reflected in the linguistic composition of reviews on platforms like Goodreads (Fig. 3). Among the 171 Chinese literary works with existing Portuguese translations on Goodreads, there were 56,063 reviews: a substantial 85.2% written in English, a mere 0.58% written in Portuguese. While comparable to reviews written in French (0.68%), Italian (0.82%), and Vietnamese (0.92%), it significantly lagged behind Spanish (4.41%). This discrepancy shows that the Portuguese-speaking readers, or readers who would like to share their views in Portuguese, constitutes a very small audience globally. The data strongly implies that most Chinese works translated into Portuguese likely had prior English versions. Portuguese, in this context, appears to occupy a peripheral position in the global dissemination chain and a closer examination of individual works further substantiated this trend. Given the historical dominance of English, more than half of the translations in the semi-peripheral and peripheral languages are translated from the English (Heilbron 1999). Furthermore, it’s plausible that some Portuguese-speaking readers with bilingual or multilingual backgrounds may choose English for expressing their thoughts, further reflecting the pervasive influence of English in the literary landscape.

Analysis of reviews

The analysis of reader reviews provides essential insights into how Portuguese-speaking readers respond to translations of Chinese literature. A database was created from reviews with the highest ratings and engagement on Amazon Brazil, Goodreads, and Skoob, collected until October 2022. While not exhaustive, this database offers a rich resource to explore key themes and reader perspectives.

To analyze reviews, a corpus-based approach was used. Separate corpora were compiled from Chinese, English, and Portuguese reader responses. Keywords unique to each work were identified by comparing each corpus with general language patterns in the same language, using Sketch Engine. At last, approximately 250 Portuguese keywords were found in each work, reflecting themes and perspectives unique to Portuguese-speaking readers.

Table 2 summarizes the number of reviews included in the corpus analysis and the platforms they were sourced from.

Keywords in reader responses to the works were categorized into five thematic groups:

-

1.

Narrative and Character Description: This category includes references to the names, actions, and relationships of characters, such as “Zetian” and “Nine-Tailed Fox”.

-

2.

Thematic Abstraction: This includes reflections on major cultural, political, or philosophical issues, with abstract terms like “China”, “women”, “culture,” “science” and “society.”

-

3.

Contextual Observations: This group captures references to geographical, climatic, and historical context, including terms like “Communism”, “Cultural Revolution” and “Mao Zedong”.

-

4.

Literary Critique: This category encompasses criticism of literary techniques, authorial intent, or symbolic elements, using terms such as “novel”, “Cixin,” “metaphor,” and “realism.”

-

5.

Sentimental Evaluation: This includes assessments of the novel’s quality through descriptive and evaluative language, often reflecting positive or negative attitudes with terms like “brilliant,” “vivid,” and “great.”

These thematic categories were developed through a manual coding process. Using the corpus’s concordance tool, sentences containing these keywords were examined to explore their semantic context. While the keywords provided a starting point, the following discussion builds on this analysis to synthesize overarching themes that capture the broader cultural and emotional resonance of the works.

China as a cultural image

Portuguese-speaking readers, approaching Chinese literary works as representatives of an exotic culture, initially perceive the novels as distinctly ‘Chinese’. This observation primarily comes from the type 2 and type 3 keywords. This perception is particularly evident in the historical narratives In the Land of White Deer, The Three-Body Problem, and Iron Widow. Unlike Chinese readers who prioritize the narrative content and its reflection of self-cultural identity as observed on the Chinese Douban review platform, Portuguese-speaking readers tend to prioritize the overarching ‘China’ label. This preference is attributed to their default state of cultural unfamiliarity.

The first image within the label identifies China as a country with a distinctive ideological style. On the Chinese Douban platform, the term “共产党” (Communist Party) ranks 8th, and “共产主义” (communism) ranks 42nd in the review keyword list of In the Land of White Deer. Notably, in Portuguese reviews, the term “comunismo” (communism) and its derivatives, such as “comunista” (communist), take precedence as the novel engages with historical contexts. The rich semantic collocations of “comunismo/comunista/comunistas” in Portuguese unveil nuanced interpretations of modern Chinese political ideology, encompassing notions like “communist ideals”, “forces led by the Communist Party”, “Communist Party influence”, “historical era led by the Communist Party in China”, and even “Communist Party members”. These terms, strategically positioned in the discourse, allow readers to sense their association and contribute to a vivid portrayal of China. Additionally, terms like “20th century”, “revolution”, “Mao Zedong”, “regions”, “Japan”, and “invasion” collectively form an associated interpretation of Chinese political culture.

The prominence of certain terms in Portuguese reviews indicates readers’ sensitivity to ideological distinctions between the East and the West. Not surprisingly, ideology is a factor that drives people to accept or not accept a story (P. Li 2012). The frequent discussions around “communismo” suggest a level of familiarity among Portuguese-speaking readers with the concept, fostering curiosity about how the Chinese Communist Party achieved victory in the revolution. Consequently, terms like the Nationalist Party are also brought into the discourse. It is discernible that the tumultuous narrative of the rivalry between the Nationalist and Communist parties serves as a selling point for publishers, adding an intriguing layer to the book’s narrative. This lexical emphasis in Portuguese reviews uncovers how readers construct their image of China through the lens of ideological and historical contexts, showcasing a nuanced understanding of the political landscape and historical events in the country.

“Cultural Revolution” is among the high-frequency terms in Portuguese reviews of The Three-Body Problem, mentioned in approximately one in every six comments. This significant presence depicts the historical backdrop of the story, introducing a key element to the protagonist Ye Wenjie. Technically, it rationalizes the storyline of Ye seeking contact with the Trisolarans. Many readers stated that beginning with the Cultural Revolution adds force to the story as it was shocking to read about the sadness and disaster of the Revolution. One reader on Amazon.br stated, “The novel begins with a compelling narrative centered around the peak of the Cultural Revolution in China and how politics, and even more so, ignorance, affect the scientific community” (Lerner, 10/19/2017).

The second image within the overarching ‘China’ label associates with a mystified and surreal China. Among Portuguese-speaking readers of Iron Widow, approximately 30% of Skoob comments explicitly mention “China,” underscoring the novel’s deep integration of Chinese elements. The story, originally written in English and heavily reliant on western writing technique, frequently refers to Chinese tradition and incorporates characters’ names drawn from Chinese history. There is a surreal operation based on the concept of qi with the five traditional Chinese elements – metal, wood, water, fire, and earth. Allusions to Chinese culture and historical customs abound, such as the war machine ‘Nine-Tailed Fox’ named after a classic Chinese fable. The Chinese elements in the book have sparked a torrent of love among readers; however, while some express admiration for the portrayal of Chinese culture, others notably find the representation of China to be mysterious and elusive. Camouflaged under the fictional nature of the plotlines and vague locations, the real history of ancient China is mystified.

BM02 (3/16/2022) theorizes that lacking a background in Chinese culture might leave readers perplexed, as the author doesn’t extensively explain these details. Leo Oliveira (6/12/2022) shares this sentiment, expressing lingering confusion about the worldbuilding. This sentiment resonated, garnering considerable likes, indicating a shared difficulty among readers in comprehending the intricacies of the constructed Chinese world. The lack of detailed depiction of societal settings, geographical locations, and political systems creates a virtual and unreal ancient China. For example, readers struggle to grasp the settings with only two distinctly identified: the Great Wall, the most powerful cocoon and the pilot’s headquarters; and Chang’an, the hometown of the male protagonist Yi Zhi. Mostly the characters’ locations remain ambiguously situated, hindering readers when attempting to recall and visualize these settings. The novel mentions that Wu Zetian comes from a Chinese rural area, her hometown conquered by “周” (Zhou). She is described in the second chapter as walking on frozen rice terraces, with bound, painful feet. However, such an image does not align with reality in China, as rice terraces only appear in warm regions where rice is harvested long before winter. These images serve an emotional purpose, essentially constructing a virtual and not necessarily authentic world. Readers familiar with Chinese culture may recognize that her childhood suffering, presented in a fragmented and fabricated manner, lacks authenticity; but for those without a deep cultural understanding of China, the novel falls short in providing the depth and complexity expected by informed readers. Instead, it risks presenting a superficial and stereotypical view of Chinese history and literature.

Additionally, for readers less inclined to delve into Chinese culture, which may constitute a significant portion of the audience, the novel effectively blends emotions, characters, imagery, and environmental settings, reinforcing a virtual and fragmented image of Chinese culture. As noted by Bueno (2013), a Sinologist and Portuguese translator of The Art of War, many Portuguese-speaking readers hold a mixed impression of China, often conflating elements from other Eastern cultures like India and Japan. This confusion is evident, for instance, in Brazilian editions of The Art of War featuring Japanese swords on the cover. Misconceptions are further exacerbated by the inaccurate portrayal of Chinese elements, such as Tang dynasty women binding their feet, rice seedlings on frozen terraces, and ancient silk robes embroidered with bamboo shoots. These erroneous fictional depictions contribute to widespread misunderstandings among readers.

Such misunderstandings are compounded by the dissemination of romanticized, ‘Chinese-style’ novels, which solidify stereotypes and limit the accurate portrayal of authentic Chinese culture. Bueno has criticized the use of Japanese elements on Chinese books, lamenting the challenge of presenting authentic Chinese cultural elements for Western audiences accustomed to such inaccuracies, romanticizations, or aesthetic expressions. This challenge, known as the translator’s “difficulty in adaptation,” arises from the broader impact of fictional representations on cultural perceptions and understanding.

The third image of China emerges through perceptions of “bizarre” and “absurd” elements, particularly in In the Land of White Deer. While the literary quality has received high acclaim, when viewed through a Western lens, some scenes may be unconventional and discomforting. Take, for instance, the opening scene where Grandpa Bingde is ailing:

Mr. Leng instructed others to press tightly on the old man’s legs, feet, and neck. He inserted a steel plate into old man Bingde’s mouth. Using his left index finger, he split it into a V-shaped brace, forcing Bingde’s mouth wide open to its limit. Simultaneously, with his right hand, he plunged a steel needle, glowing red and yellow from the alcohol flame, directly into the throat.

This narrative approach exemplifies the style of ‘legendary’ writing in Chinese literature, where novels specifically depict stories with unusual plotlines or unconventional character behavior. The reader’s emphasis on the “bizarre” and “absurd” elements manifests a cultural interpretation within the context of cross-cultural transmission.

Women as the oppressed

With over 60% of the Portuguese-speaking readers analyzed being female, there is perhaps unsurprisingly a clear preference for novels that offer a female perspective, that feature women as protagonists, and explore women’s issues. Novels such as Iron Widow and The Good Women of China stand out for their vivid female characters, resonating deeply with Portuguese-speaking readers whose understanding of Chinese women is predominantly shaped by their portrayal as being oppressed. The insight primarily draws on keywords from type 3 and type 5, which reflect the focus on women’s experiences and the emotional resonance these novels evoke.

Iron Widow tells the story of Wu Zetian, China’s only woman emperor, piloting mechs to battle extraterrestrial creatures. The narrative unfolds in a society marked by gender bias, where a girl’s sole value lies in becoming a concubine and providing family compensation upon her death. Wu Zetian risks her life to avenge her sister’s death by becoming a concubine, successfully pairing with the pilot Yang Guang, and accessing his memories through a mental connection. She sees the girls he abused and ultimately kills him. Rising in power, she earns the title ‘Iron Widow’ and determines to destroy the Chrysalis system, eliminating the dependence on female sacrifices. The author envisions the life experiences of Chinese women, describing the protagonist’s environment as an “extremely misogynistic society”, which resonates with many young women’s aspirations for recognition, success, and empowerment. The novel receives continuous praise from teenage girls on social media for its exploration of gender roles, feminism, and patriarchy.

Skoob reflects the overwhelmingly positive reception of Iron Widow. The highest-rated reader, Let (3/22/2022), passionately praises the protagonist, narrative, and ending. Another reader, bia (7/18/2022), expresses her profound admiration, stating the book as one of the best she has ever read. Evaluative adjectives in Portuguese reviews overwhelmingly express admiration, with terms like “I love it”, “looking forward to more”, “amazing”, “liked it”, “interesting”, “perfect”, “wow”, and “fantastic” dominating the feedback, emphasizing the widespread acclaim for the novel.

The Good Women of China tells ‘true’ stories from 15 women in modern China. The protagonists include: a rural girl who falls victim to sexual assault; a female college student compelled to trade her body for financial gain; a mother grappling with the aftermath of her daughter’s sexual assault during the Tangshan earthquake; and a highly educated woman entangled in a half-century of romantic challenges. All the names in the book are pseudonyms and the central characters, under the dual pressures of male dominance and centralized power, lead lives marked by misery, pain, confusion, extremism, or misguided choices. Employing a range of writing techniques, the book utilizes novelistic descriptive skills, dramatic dialogues, poetic leaps, and even narrative methods reminiscent of film scenes. The original Chinese text was published in 2003 in China. The author of the book, Xinran, claimed it to be a journalist’s factual memoir. The book received acclaim from The Guardian, The Washington Post, and The New Yorker. In Brazil, the Portuguese-language version has gained popularity since its publication, with over 8000 readers on the Skoob website as of June 2022. It ranks 14th in sales in the ‘Asian History’ category, making it one of the top 20 books in this category written by a Chinese author.

Most reader comments express a strong sympathy in Xinran’s portrayal of the modern condition of women in China, referring to it as “captivating”, “amazing”, “shocking”, “eye-opening”, and even “painful”. Through the compelling stories, readers assert gaining an understanding of the hardships, humiliations, and sufferings of Chinese women, with many having a “powerful experience”, feeling “shocked” and “sad” by the poignant aspects of these women’s destinies. However, the reception of the book in China contrasts sharply with its popularity in Brazil. On the Chinese Douban website, it has a score of 8.2 out of 10.0, with only a few dozen reviews and 17 comments. In major bookstores and libraries, the book has not received significant attention. The lukewarm response in China can be attributed to her fictive and imaginative narrative style, a facet of her writing style that readers interpret as lacking veracity. The publication of such a biased book in China can be understood in the context of the prevalent popularity during the 1980s-90s of ‘reportage literature’, a literary form that writer Mao Dun (1937) locates “between news reporting and fiction…. characterized by prose that combines elements of journalism and literature” in China. It draws from real news but, more importantly, employs “literary techniques, covering news events with the colorful clothing of the fictive”(Yang 1982). Because of the alleged fiction-like inauthenticity, this genre wanes after 2000. Xinran’s work in Chinese was published in 2003, coinciding with the tail end of the popularity of reportage literature. This timing allowed her to capture an audience that was still interested in that genre, albeit their numbers were declining. If her work had been published later, it may not have received as much attention.

The diminishing belief in the authenticity of news presented in the form of reportage literature in China starkly contrasts with the Portuguese translation of The Good Women of China, which resonated with Brazilian readers. The classification of the book as non-fiction conveniently aligns with Western literary norms, where the boundary between fiction and non-fiction is well-defined. This categorization has fostered an appreciation for the narrative as an accurate portrayal of Chinese women’s lives, offering Brazilian readers a distinctive perspective characterizing Chinese women as profoundly oppressed.

The reception of a text in its source context, thus, “does not necessarily exert any influence on how it is going to be interpreted, translated, marketed, consumed and received in the target culture” (Qi 2023). Cultural norms and ideological contexts construct specific circumstances operating in the polysystem, playing a crucial role in shaping the reception of translated literature. In both Iron Widow and The Good Women of China, the authors employed literary techniques and storytelling styles to cater to Western tastes, contributing to the reinforcement of stereotypical impressions of Chinese women. Portuguese-speaking readers then collectively construe Chinese women as emblematic of oppression, which can result in the perceptions of Chinese women being limited to one-sided and inaccurate, conservative viewpoints.

Fantasy as a universal passion

Fantasy, characterized by boundless creativity and immersive narratives, has emerged as a universal passion that captures the hearts and minds of readers across the globe. This phenomenon is vividly illustrated in the fervor surrounding works like Iron Widow and The Three-Body Problem, where the allure of fantasy creates a shared experience, connecting readers from China and the Portuguese-speaking world. The inference draws from type 1, 2, 3 and 4 keywords, reflecting the universal appeal of fantasy through its rich narratives, profound themes, and cross-cultural connections.

Iron Widow weaves a rich tapestry of fantasy through its unique blend of East Asian historical romance and Western epic narratives. The concept of ‘Silkpunk’, as coined by Ken Liu (2022), is central to this work. Silkpunk combines elements from diverse global literary traditions, merging the skeleton of Western epic fantasy with the flesh of Eastern mythological history (Jin 2022). In Iron Widow, readers encounter historical allusions and mythological creatures, such as the ‘Nine-Tailed Fox’ which is the flying war machine. The nine-tailed fox originates from Chinese mythology, specifically the Classic of Mountains and Seas (Nanshan Jing), which describes it as “a beast resembling a fox with nine tails in the mountains of Qingqiu.” In Iron Widow, it is depicted as a towering seven- or eight-storey building, with bristly green fur and metallic claws that pound the earth, creating a fusion of history and myth that constructs a fantastical world both familiar and exotic to readers.

Fantastical technology also play an important role in the story. “Qi was the vital essence that sustained everything in the world, from the sprouting of leaves to the blazing of flames to the turning of the planet” (Zhao 2021). The use of qi and the five traditional Chinese elements in technological operations adds a layer of fantasy, blending mystical concepts with futuristic technology. Readers from the Portuguese-speaking world have shown great enthusiasm for the fantastical elements in Iron Widow. Reviews often underline the unique blend of East and West, appreciating the novel’s ability to transport them to a richly-imagined world. As one reviewer notes, “The question of the different Qis and their powers, such as the chrysalis that can transform according to the pilots is one of the most interesting things” (Zyotic, 07/03/2022). Another states, “I really liked the combination of ancient Chinese traditions and culture with technology, it was able to create a very unique and beautiful mental image.” (Nana_tsur, 02/03/2022). In the reviews, “qi” was mentioned 199 times, and “chrysalis” 138 time. Such responses exhibit a universal appeal of fantasy when it successfully merges diverse cultural elements.

The Three-Body Problem series, on the other hand, masterfully intertwines elements of fantasy with rigorous scientific concepts, crafting an extraordinary universe that captivates readers across linguistic and cultural divides. The depiction of the Trisolarans and their advanced technology introduces readers to a fantastical vision of alien life and interstellar communication. The use of virtual reality games blurs the line between reality and fantasy, immersing readers in a complex, layered narrative. It has been translated into 30 languages and has won nine top-tier international science fiction awards, including the Hugo Award for Best Novel, and the highest honors in Chinese science fiction. It is regarded as one of the most successful Chinese science fiction novels of the past two decades on Chinese Douban, with over 500,000 comments. Readers from the Portuguese-speaking world and other regions have engaged deeply with the series and in Brazil, where there is traditionally limited interest in science fiction, the trilogy has attracted a small but devoted fan base. These fans demonstrate a high capacity for engaging in discussions, summarizing the story, evaluating literary aspects, and discerning the quality of science fiction novels. Portuguese-speaking readers consistently rate The Three-Body Problem trilogy between 4.2 and 4.8 stars out of 5.0, showing a profound understanding and appreciation for this work of science fiction.

Reviews frequently mention the novel’s ability to blend hard science with fantastical elements, creating a unique reading experience. One reader said, “I really enjoyed the book, which explores the theme of contact with another civilization in space by blending historical elements from China with many scientific concepts” (Juliano.Camargo, 01/06/2020). Another said, “First class science fiction with very interesting elements: virtual reality, microcosm, extraterrestrial invasion, betrayals” (Joao Neto, 11/13/2020). It is widely accepted that the novel has succeeded in transcending cultural and national boundaries through its universal appeal to fantasy and science.

Portuguese-speaking readers in particular have shown a keen interest in the scientific themes of the series, as evidenced by the prominence of terms like “science” and “scientific” in their reviews. This contrasts with their English-speaking counterparts, who prioritize the word “culture” (0.74‰). The term “scientific” (científico) tops the adjective list in Portuguese reviews, with common combinations like “science fiction” (ficção científica), “scientific concepts” (conceitos científicos), and “scientific explanations” (explicações científicas). Portuguese-speaking readers frequently delve into scientific nuances, including physics, theoretical physics, sophons, and quantum physics. “Physical” (físico) ranks 3rd in the adjective list, with common combinations like “physical concepts”, “physical phenomena”, and “physical theories”. The trend of highlighting “science” also reveals that Portuguese-speaking readers resonate with this aspect of the novel, showing its ability to transcend cultural and national boundaries. By sidestepping deep-seated cultural opposition, readers immerse themselves in the universal theme of science, overcoming ideological biases, historical values, and geographical limitations.

The series’ success in integrating scientific concepts with fantastical storytelling is further demonstrated by the high regard in which author Liu Cixin is held, as shown by the numerous mentions of his name in discussions surrounding the trilogy. In the noun category, the term “Cixin” tops the wordlist, with discussions on his personal experiences, work evaluations, writing techniques, plot guidance, character development, fields involved, and knowledge levels. The author’s name appears 145 times, exemplifying the intense discussions surrounding him and his contributions to the trilogy.

Portuguese-speaking readers demonstrate an openness to various cultural contributions in the global context. In their science fiction market, foreign works consistently dominate while domestic productions remain scarce (Ferreira 2008). According to Even-Zohar (1978b), in circumstances where a literary scene is deemed “peripheral” or “weak”, translated literature can integrate with innovative forces, actively contributing to the shaping of the literary polysystem’s core. As Portuguese-speaking readers tire of the Anglo-Saxon paradigm, they might eagerly seek literature from beyond the confines of Europe and America to enrich their reading experiences. The Three-Body Problem, with its distinctive writing style infused with Eastern characteristics, adeptly meets these demands. The novel evokes a sense of empathy for humanity’s fate rather than solely focusing on interspecies conflicts, offering a more nuanced technocratic perspective. By recognizing these distinctions, Portuguese-speaking readers engage in insightful comparisons between Liu Cixin and Western authors with comments such as these on Amazon Brazil echoing these sentiments:

In short, it doesn’t have to be American and full of clichés to be interesting. (Anderson, 11/5/2017)

Different from the American or English style of writing, it maintains historical interest and shows a worldview distinct from the Western view. (Claudinei Dias, 1/1/2021)

It’s interesting to see science fiction from authors who are not European or American. This book allows us to do that. Very good. (Cicero Marques, 4/25/2018)

In short, the rise of Chinese-themed fantasy or science fiction, as exemplified by works like Iron Widow and The Three-Body Problem, reflects the eagerness of Portuguese-speaking readers to embrace innovation. These works, seeking the common passion, challenge traditional Western paradigms and contribute to the evolution of the literary landscape by integrating innovative elements from diverse cultural traditions. In the Portuguese-speaking world, where foreign literature dominates and domestic productions are scarce, the reception of Chinese science fiction indicates a growing receptivity to cultural diversity.

Conclusion

This paper provides a broad overview of reception and reader engagement with translated Chinese literary works among Portuguese-speaking readers. Our examination of data post-1979 from platforms like Amazon, Goodreads, Skoob, and WorldCat, reveal a consistent upward trajectory in the number of translations. This growing trend encompasses a diverse array of genres, from classical poetry to contemporary novels and philosophical texts, ensuring a broad readership for Chinese literature with varied interests.

Contemporary Chinese literature, reflecting societal realities, tastes, trends, and cultural transformations, has gained remarkable popularity among readers. This success can be attributed to several key factors. Esteemed contemporary authors like Liu Cixin, Chen Zhongshi, Mo Yan, and Yu Hua, celebrated for their literary excellence and global recognition, continue to enthrall audiences with their high-quality works and well-preserved translations. Reader reception is notably influenced by market dynamics driven by growing curiosity about Chinese culture, feminist themes, and fantasy genres. Genres like science fiction and fantasy resonate deeply, sparking vibrant discussions and forging connections across geographical and cultural boundaries. Effective marketing strategies, especially targeting younger audiences through social media, have further contributed to the success of certain books, fostering widespread engagement and interest.

While English currently dominates the international translation system, the role of Chinese-Portuguese translation is evolving from periphery to prominence. As translation activities between these languages expand, the Portuguese-speaking world may increasingly serve as a gateway through which the Western world perceives China. Within this sphere, Chinese literature is progressively gaining recognition and influence. Nonetheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that the accomplishments and discussions surrounding specific Chinese literary works in the marketplace do not necessarily signify a comprehensive understanding of the intricate and diverse essence of China by Portuguese-speaking readers. Their perceptions of Chinese culture may exhibit nuances or complexities shaped by cultural norms, assumptions, and community standards. For example, works like The Good Women of China might inadvertently stereotype Chinese women as perpetually oppressed, overlooking the nuanced and progressive roles of contemporary Chinese women within their socialist context. Such perspectives are molded by the readers’ ideological frameworks, which may differ from those of native Chinese readers.

Our findings have several theoretical implications. Firstly, the increasing prominence of Chinese-Portuguese translation reflects the dynamic nature of the international translation system, as opposed to a static one, and aligns with the principles of the polysystem theory suggesting that translated literature is influenced by evolving socio-cultural and literary trends. Secondly, literary reception is inherently shaped by cultural contexts and perspectives, so there is need for translators and publishers to navigate these complexities, such as cultural stereotypes and reader expectations, effectively. Thirdly, the popularity of translated literature not only adheres to literary norms but also reflects universal human interests. Genres like science fiction and fantasy, due to their universal appeal and potential to transcend cultural boundaries, serve as bridges across ideological and political divides. They stimulate global dialogue and foster a deeper understanding between cultures.

In conclusion, this study offers valuable insights into the translation and reception of Chinese literature in the Portuguese-speaking world. As one of the pioneering studies in this emerging field, it acknowledges the current lack of extensive research and lays the groundwork by introducing key aspects of this underexplored area. Future research could delve into investigating translation strategies and their influence on reader engagement, exploring detailed reader engagement through qualitative research methods, examining gender dynamics in literary engagement, and analyzing changes within literary systems. Addressing these research gaps will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the reception of Chinese literature in Portuguese-speaking countries and facilitate the continued enrichment of cross-cultural literary exchange.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the findings of this study, consisting of 84 Portuguese-translated versions of contemporary Chinese literary works collected from publicly accessible platforms, is available at the Harvard Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/2PNPP2. Additional details regarding the data sources are available upon request.

References

Baker M (2014) The changing landscape of translation and interpreting studies. In C. P. Sandra Bermann (Ed.), A companion to translation studies (pp. 13–27): Wiley-Blackwell

Bartl S, Lahey E (2023) ‘As the title implies’: How readers talk about titles in Amazon book reviews. Lang Lit 32(2):209–230

Bernardo MP (2022) “Iron Moon”: a vida de trabalhadores migrantes retratada em poesia contemporânea chinesa. Daxiyang Guo - Revista Portuguesa de Estudos Asiáticos/Portuguese. J Asian Stud (29):101–112. https://ojs.apl.pt/index.php/rapl/article/view/187

Brems E, Ramos Pinto S (2013) Reception and translation. In Doorslaer YGLv (ed), Handbook of translation studies (vol 4, pp 142–147): John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Bueno A (2013) As dificuldades de uma tradução: um ensaio sobre o Sunzi bingfa 孫子兵法 e o contexto cultural brasileiro. Cadernos de Literatura em Tradução(14), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2359-5388.i14p89-98

Catford JC (1965) A linguistic theory of translation: An essay in applied linguistics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Chan LT-H (2016) Reader response and reception theory. In Angelelli CV, Baer BJ (eds), Researching translation and interpreting. Routledge, pp 146–154

Chan LT-H (2022) Historical and empirical approaches to studying the “real” reader of translations. Asia Pac Transl Intercult Stud 9(2):117–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/23306343.2022.2100091

Chen X (2023) Interactive reception of online literary translation: the translator-readers dynamics in a discussion forum. Perspectives 31(4):690–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2022.2030375

Chesnokova A, Zyngier S, Viana V, Jandre J, Rumbesht A, Ribeiro F (2017) Cross-cultural reader response to original and translated poetry: An empirical study in four languages. Comp Lit Stud 54(4):824–849

Costa MMD, Peixoto BEN (2021) A imagem estereotipada dos chineses em crónicas portuguesas. Diacrítica 35(1):229–246

Cussel M (2024) When solidarity is possible yet fails: A translation critique and reader reception study of Helena María Viramontes’ “El café ‘Cariboo’. Translation Stud 17(1):70–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2023.2177331

Even-Zohar I (1978a) Papers in historical poetics (Vol. 15): Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics Tel Aviv

Even-Zohar I (1978b) The position of translated literature within the literary polysystem. In Papers in historical poetics, vol 15. Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics Tel Aviv, pp 21–27

Farghal M, Al‐Masri M (2000) Reader responses in quranic translation. Perspectives 8(1):27–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2000.9961370

Ferreira RH (2008) Review of Anuário Brasileiro de Literatura Fantástica: Ficção científica, fantasia e horror no Brasil em 2005. J Fantastic Arts 19(3):422–425, 453

Fish SE (1973) What is stylistics and why are they saying such terrible things about it? In Approaches to poetics (pp. 109–152): Columbia University Press

Frosi TO, Maidana W, Mazo JZ (2011) Os primórdios da prática do wu-shu/kung fu em Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul (décadas de 1970-1990). Rev da Educção FíSci da Univ Estadual de Mará 22(3):387–397

Guo M, Min R (2022) Beyond representation: Shanshui motif on Chinese porcelain and Portuguese faience. Arts 11(5):103

Heilbron J (1999) Towards a sociology of translation: Book translations as a cultural world-system. Eur J Soc theory 2(4):429–444

Jauss HR (1982a) Aesthetic experience and literary hermeneutics. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

Jauss HR (1982b) Literary history as challenge to literary theory. Toward an aesthetic of reception. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

Jin X (2022) Yi qi wei dao, yi sichou pengke wei jieyao 以器为道, 以丝绸朋克为解药 (Using artifacts as the way, silk punk as the remedy). Kehuan yanjiu tongxun 科幻研究通讯 (Science Fiction Research Newsletter), 2(1). Retrieved from https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/qyqziq35IpWIHQZQl42mdQ

Lee AP (2020) Mandarin Brazil: Race, representation, and memory. California: Stanford University Press

Leite JRT (1999) A China no Brasil: Influências, marcas, ecos e sobrevivências chinesas na arte e na sociedade do Brasil: Unicamp

Li L (2023) Estratégias e praticas de tradução do Padre Joaquim Gonçalves. Revista da Associação Portuguesa de Linguística (10):162–181. https://doi.org/10.26334/2183-9077/rapln10ano2023a9

Li P (2012) Ideology-oriented translations in China: a reader-response study. Perspectives 20(2):127–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2011.589906

Liu K (2022) What is “Silkpunk”? Retrieved from https://kenliu.name/books/what-is-silkpunk/

Mao Dun (1937) Guanyu baogao wenxue 关于“报告文学” (On reportage literature). 中流(上海1936) Zhong Liu (Shanghai, 1936). 1(11):21–623

Minnaert ACDST (2018) A comida na diáspora: um olhar antropológico sobre a comida chinesa em Salvador, Bahia. Afro-Ásia 58:119–153

Nida E (1964) Principles of correspondence. In Toward a science of translating. Leiden: E. J. Brill, pp 152–192

Pinto MP (2013) The first Portuguese anthology of classical Chinese poetry. In L. D. h. Teresa Seruya, Alexandra Assis Rosa and Maria Lin Moniz (Ed.), Translation in Anthologies and Collections (19th and 20th Centuries) (pp. 57–74): Benjamins

Qi L (2023) Source text readers as censors in the digital age: a paratextual examination of the English translation of Wuhan Diary. Perspect 31(2):282–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2021.1939741

Schmaltz M (2013) Apresentação e panorama da tradução entre as línguas chinesa e portuguesa. Cadernos de Literatura em Tradução (14):13–22. https://www.revistas.usp.br/clt/article/download/96703/95906

Silva ARD, Curcino L (2023) Por que não li antes? Da vergonha ao orgulho de ler em postagens de jovens leitores na rede SKOOB. Estudos Linguísticos (São Paulo 1978) 52(1):265–282

Sinedino G (2023) One text, many voices: “diffuse authorship” and the translation of Chinese classical literature into Portuguese. Cad de Tradução 43(3):47–76

Thussu DK, De Burgh H, Shi A (2018) China’s media go global. Routledge London, London/New York

Tselenti D, Cardoso D, Carvalho J (2024) Constructing sexual victimization: a thematic analysis of reader responses to a literary female-on-male rape story on Goodreads. J Sex Res 61(3):374–388

Walker C (2021) An eye-tracking study of equivalent effect in translation: Springer

Wang F, Humblé P (2020) Readers’ perceptions of Anthony Yu’s self-retranslation of The Journey to the West. Perspect 28(5):756–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2019.1594317

Wang S (2019) Transcontinental Revolutionary Imagination: Literary Translation between China and Brazil (1952–1964). Camb J Postcolonial Lit Inq 6(1):70–98

Yang R (1982) Baogao wenxue ruogan shiliao kaobian 报告文学若干史料考辩 (An Examination of Reportage Literature through the Prism of Historical Sources). Xin wenxue shiliao 新文学史料 (N. Lit Historical Mater) 4:180–189

Yao J (2021) Traduzindo a China literária. Rotas a Oriente. Revista de estudos sino-portugueses. (1):199–214. https://doi.org/10.34624/ro.v0i1.26205

Ye P, Albornoz LA (2018) Chinese Media ‘Going Out’ in Spanish Speaking Countries: The Case of CGTN-Español. Westminst Pap Commun Cult 13(1):81–97

Yuan J (2024) Figuras da China e de Macau entre duas navegações portuguesas do século XX: consolidação e desconstrução. Via Atlântica 25(1):766–804

Zhao XJ (2021) Iron Widow. Penguin, Canada

Zheng X, Lyu L, Lu H, Hu Y, Chan G (2021) The internationalization of TCM towards Portuguese-speaking countries. Chinese Med 16(81). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13020-021-00491-6

Zhong C (2022) O exotismo na literatura orientalista portuguesa. Orientes do Portês 4:163–179. https://doi.org/10.21747/27073130/ori4a7

Zhou M (2019) Translation of ‘culture-specific concepts’ in context of indirect translation. Diacrítica. https://doi.org/10.21814/diacritica.5147

Zhou M (2023) Exploring homology of fields in translation: A sociological examination of Chinese contemporary literature translation in Brazil and Portugal (2000–2022). Babel: Revue Intérnationale de la Traduction/International Journal of Translation 70(6):852–870. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00363.zho

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Teresa Goudie for her professional editing of this manuscript. This research is funded by Macao Polytechnic University [grant number RP/ESLT-02/2021].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xin Huang, the first author, served as the primary executor of the study, responsible for experimental design, implementation, data collection, and analysis. She also drafted the manuscript and continuously revised it to ensure its quality and coherence. Xiang Zhang, as the corresponding author, conceptualized the study, provided the initial dataset and research ideas, and oversaw the submission process. He also secured funding from Macao Polytechnic University and provided support for the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not applicable as the study did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Zhang, X. Translating culture: the rise and resonance of Chinese contemporary literature in the Portuguese-speaking world. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 168 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04457-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04457-z