Abstract

Academic stress, which is a frequent experience for university students, has been demonstrated to have a considerable effect on their academic performance. However, the conceptual basis linking the biological mechanism of stress with educational outcomes remains fragmented. This systematic literature review seeks to synthesize current knowledge on the biological and educational perspectives of academic stress and its impact on student performance. Using the PRISMA framework, a comprehensive search was conducted in the Scopus database, yielding an initial pool of 4054 articles. After applying predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria focused on academic stress in university students, 31 articles were selected for detailed analysis. The review identifies four key theoretical foundations: the neurocognitive aspects of stress and performance, the neurophysiology of stress, epigenetic regulation of stress, and stress and genetic variations. Based on these insights, the study proposes three main directions for subsequent studies: enhancing the understanding of stress mechanisms, developing effective educational interventions, and employing interdisciplinary approaches in subsequent studies. These findings aim to provide a comprehensive framework for optimizing academic performance by deepening our understanding of the biological and educational dimensions of stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Academic stress is a physiological, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral response to stimuli that can influence students’ capacity to adjust to the educational setting (Pozos‐Radillo et al. 2016). This multifaceted nature of academic stress aligns with the bio-psycho-social paradigm (WHO, 2001), which highlights the integration of biological, psychological, and social components in understanding stress. Stress is also defined as an adaptive systemic process that consists of three stages: perceiving a stressor, experiencing systemic imbalance manifested as symptoms, and responding to restore equilibrium. Three components identified in this systemic process are the stimuli that trigger stress, the symptoms indicating imbalance, and coping strategies (Castillo-Navarrete et al. 2024). Academic stress among university students can be caused by factors such as academic workload, poor peer relationships, inadequate facilities, and academic demands that exceed students’ adaptive capacities (Bedewy and Gabriel, 2015; Reddy et al. 2018). This phenomenon is particularly common among students, especially those studying in fields with extensive content, and can significantly impact their overall development during their education (Briones et al. 2024).

Various studies have measured the levels of academic stress experienced by students and identified its triggers through surveys and rating scales (Mayya et al. 2022; Špiljak et al. 2022). A survey of university students found an academic stress prevalence of 51.1%, with workload, time constraints, and academic difficulties being the main stressors (Zamroni et al. 2018). Several studies confirm a significant correlation between academic stress and students’ mental well-being (Córdova Olivera et al. 2023; Barbayannis et al. 2022; Ojewale, 2020). High-stress levels among university students are associated with persistent mental health issues and can affect their academic performance (Stirparo et al. 2024).

Academic-related stress can lead to decreased academic achievement, reduced motivation, and an increased risk of mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and substance abuse (Córdova Olivera et al. 2023; Pascoe et al. 2020; Wyatt and Oswalt, 2013). Stress levels are found to be a significant predictor of academic performance, with perceived stress negatively impacting both mental health and academic performance (Amhare et al. 2021; Javaid et al. 2024). In another study (Almarzouki, 2024), stress negatively affects cognitive functions such as working memory, which is crucial for academic skills, potentially reducing academic performance.

Understanding the biological response to stress is crucial for comprehending the mechanisms and impacts of stress and mental health (Nadal et al. 2021). Analysis at the micro level provides precise information about the biochemical, psychophysiological, and neurological processes underlying behavior. This level of analysis is critical for developing models and insights related to neuropsychological and neurophysiological disorders (de la Fuente et al. 2019). Physiological parameters, such as heart rate variability and hormone levels, can be used as biological markers to objectively measure stress and its intensity (Armario et al. 2020). Studies reveal that academic stress has a significant impact on the cardiovascular system, leading to increased heart rate, blood pressure, and reduced heart rate variability, indicating sympathetic autonomic stress dominance (La Rovere et al. 2022; Seipäjärvi et al. 2022).

A number of studies have shown that salivary alpha-amylase (sAA) levels increase in response to psychological stress, such as during exams or high-risk situations (Brodersen and Lorenz, 2020). sAA has been used to assess autonomic nervous system function in clinical populations and shows secretion patterns that could be valuable indicators of autonomic nervous system dysfunction typically occurring in chronic stress-related pathologies (Ali and Nater, 2020). These studies found a positive relationship between sAA and sympathetic nervous system activity during stress, indicating its sensitivity to psychosocial stress and potential use as a non-invasive measure of stress in clinical and research settings (Rashkova et al. 2012).

In addition to salivary alpha-amylase (sAA), other biological markers, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and cortisol, are essential for understanding the body’s stress response. Levels of BDNF and cortisol are key indicators in stress research (Jiang et al. 2017; Hermann et al. 2021; Castillo-Navarrete et al. 2023). Harb et al. (2017) found that BDNF protein levels were negatively correlated with hair cortisol and somatic complaints, while hair cortisol showed a positive correlation with mental disorders. Acute and chronic psychosocial stress, such as academic stress, can affect peripheral BDNF and cortisol levels (Myint et al. 2021; Castillo-Navarrete et al. 2023). Research has investigated the interaction between BDNF and cortisol during acute stress, revealing that serum BDNF levels are responsive to stress and that there is an antagonistic relationship between BDNF dynamics and cortisol (Linz et al. 2019).

A variety of biological parameters have been extensively used to detect psychological stress; however, the current literature lacks a thorough examination of the relationship between these biological markers and academic performance. For instance, studies indicate that levels of BDNF and cortisol are crucial for understanding stress (Ballestar-Tarín et al. 2024), but their direct impact on academic achievement is underexplored. Similarly, heart rate variability and sAA have been identified as significant indicators of stress (Armario et al. 2020; Brodersen and Lorenz, 2020), yet knowledge of how these physiological responses correlate with students’ academic outcomes is limited. Existing studies primarily focus on the acute and chronic effects of psychosocial stress on these biological parameters (Hermann et al. 2021; Castillo-Navarrete et al. 2023), but the specific biological mechanisms explaining how academic stress affects academic performance remain poorly understood. This gap indicates the need for further research to elucidate the biological basis of academic stress and its direct consequences on academic achievement.

Several systematic reviews have explored stress in academic settings with various focuses and approaches. Jiménez-Mijangos et al. (2023) examined stress and anxiety detection methods in universities using psychological instruments and biological signals. They analyzed advancements, limitations, challenges, and potential research pathways for detecting stress in classrooms. This study provided valuable insights, although it focused more on psychological and biological aspects without directly linking them to academic performance. Conversely, Shanbhog and Medikonda (2023) emphasized the detrimental effects of stress on students’ sleep quality, which can, in turn, influence their academic performance. Nevertheless, the connection between stress and academic performance, especially within a biological framework, is still not well comprehended.

Although these two systematic reviews have made significant contributions to the understanding of stress detection and its effects on mental health and sleep quality, there is still a paucity of research in this area that requires further investigation. One such gap is the lack of studies that directly link the biological parameters of stress in research with academic performance. The existing studies tend to focus more on stress detection methodologies and their impact on specific health aspects, rather than comprehensively integrating biological and psychological perspectives. Secondly, a review of the literature on the use of various methodologies to detect stress reveals a lack of emphasis on the theoretical framework that bridges the biological and psychological parameters used to specifically influence academic performance. This highlights the necessity for a literature review that integrates biological and psychological perspectives to gain a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of academic stress and its impact on academic performance. To this end, this systematic literature review study was guided by several research questions (RQs), namely:

RQ1: What are the principal elements of research on the relationship between stress and academic performance?

RQ2: What are the theoretical or conceptual foundations employed in the stress and academic performance literature?

RQ3: What are some prospective avenues of inquiry in the field of academic stress and academic performance?

By identifying and analyzing limitations in previous studies, this study seeks to provide evidence-based recommendations for future subsequent studies. These include new approaches to measuring and analyzing academic stress, as well as interventions that can help college students manage stress and improve their academic performance.

Methods

The study employs a systematic literature review (SLR) approach, a desk-based research method characterized by its rigorous, standardized, and verifiable methodology. This ensures the review is replicable, transparent, objective, unbiased, and thorough (Višić, 2022; Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2015). The SLR approach helps researchers systematically map the current state of the literature, providing a structured exploration of topics and findings, and serves as a foundation for further investigations (Pati and Lorusso, 2018).

Search strategy

The search for relevant literature was conducted using the Scopus database. Scopus is a prominent citation and indexing database that provides access to global peer-reviewed literature across a wide range of subject areas (Renjith and Pradeepkumar, 2021). Automated screening with user-friendly operations can save time and costs while enhancing search accuracy with specific keywords (Van Dinter et al. 2021). Leveraging advanced features in Scopus enables researchers to narrow their search to the most pertinent and current articles within their field of study.

In order to obtain relevant data, this study utilized specific keywords within the “search” menu of the Scopus database, employing Boolean conjunction operators to achieve a more focused result set. The key search comprised (TITLE (“academic stress” OR “academic-related stress” OR “exam stress” OR “examination stress” OR “task stress” OR “work-load stress” OR “perceived stress” OR “psychological stress” OR anxiety OR depression) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (biomarker OR molecular OR physiology OR physiological OR biology OR biological OR salivary OR saliva OR cortisol OR hormone OR genetic OR epigenetic OR methylation OR bdnf OR neuron OR bmi OR “body mass index”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“academic performance” OR “academic achievement” OR “academic success” OR grade* OR gpa OR cgpa OR score OR “academic attainment” OR “academic outcome*“) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (student* OR university OR college OR undergraduate OR graduate OR postgraduate OR pre-service) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY (school OR pupil* OR staff OR professionals OR patients)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (OA, “all”)).

A comprehensive selection technique was employed to identify relevant articles, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Using these search terms and patterns, we conducted the search on June 6, 2024, identifying 4054 articles related to academic stress, depression, and anxiety mentioned in titles, abstracts, and keywords. To focus the analysis on this theme, the first search was refined to include only articles where the keywords appeared in the title.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We applied the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) model to guide the inclusion and exclusion processes, aiming to identify articles that strictly met the criteria. The PRISMA guidelines were developed to facilitate transparent and comprehensive reporting of systematic reviews, ensuring that the methods and results are detailed enough for users to assess the reliability and applicability of the review’s findings (Page et al. 2021). The following key points formed the basis of the inclusion criteria used in this systematic literature review (SLR): (1) The primary focus of the article is on stress, depression, or anxiety related to academic performance, (2) The study population consists of university students, (3) The article is an original research article, not a review, (4) Only open access articles, and (5) Articles are published in English.

A comprehensive search of electronic databases was conducted using Scopus, resulting in a total of 4054 articles related to academic stress, depression, and anxiety. The articles were then filtered to focus on those emphasizing academic stress, depression, and anxiety, narrowing the selection to 1116 articles. At this stage, 293 articles were excluded because their primary focus was not on stress, depression, or anxiety within the academic context of university students.

The subsequent criterion applied was the study population, which had to be comprised of university students. This resulted in the exclusion of 501 articles. Consequently, 615 articles were excluded on the grounds that the population under consideration included school students, university staff, professionals, or patients at a university hospital. Subsequently, the articles were further screened to include only those published in English, resulting in a total of 456 articles. This step excluded 45 articles that were reviews, conference papers, letters, books, or articles not in the English language. In the subsequent phase, the focus was narrowed to include only open-access articles, reducing the number to 222 articles. At this point, 234 articles were excluded because they were not open access.

A manual screening process was conducted to ensure eligibility, resulting in the final inclusion of 31 articles. During this step, 190 articles were excluded for reasons such as being related to pandemic-related stress, lacking biological measurements, not being related to academic performance, involving unhealthy samples, not focusing on university students, or being review articles. This process concluded with a total of 31 studies included in the review, following the stringent criteria outlined in the PRISMA guidelines.

Data extraction and analysis

The data and information from the collected 31 articles were tabulated using Microsoft Excel. The extraction table contains information on the authors, year of publication, research methodology, sample size, theoretical or conceptual framework, biological parameters, psychological instruments, main results, and limitations of the study. The table proved invaluable in the recording of pertinent information during the content analysis and synthesis phases. The data obtained from the reviewed articles were organized and subjected to analysis. Subsequently, a textual narrative synthesis was conducted. Narrative synthesis is a method for combining and summarizing data from multiple studies, relying on the use of words and literature to describe the synthesis findings (Jahan et al. 2022).

Results

A systematic review was conducted using the Scopus database, which identified a large pool of studies related to academic stress, depression, and anxiety. Through a rigorous multi-step screening process, articles were filtered based on specific inclusion criteria such as relevance to academic stress among university students, availability in English, and open-access status. Additional manual screening ensured that only studies aligning with the review’s focus on academic stress, biological measurements, and academic performance were included. This thorough process resulted in the final selection of 31 articles. The detailed decision-making process is presented in Fig. 1.

Key aspects of research

The analysis identified 31 relevant studies within the scope of research conducted across 19 countries. Two studies were conducted in African countries, namely Uganda and South Africa. Eight studies were conducted in Europe, covering Finland, the UK, Croatia, Germany, and Italy. Six studies were carried out in the US and Canada. Nine studies were conducted in Asian countries, including Hong Kong, Pakistan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Japan, and India. Finally, six articles were from South America, covering Chile, Brazil, and Mexico. All articles reported research examining stress, anxiety, and depression among university students. Each study used biological and psychological approaches to identify stress and develop discussions on the impact of stress on academic performance (Table 1).

Biological parameters

Thirty-four biological parameters were used across the 31 studies analyzed. Some of these studies utilized biological parameters to identify stress, depression, or anxiety status without necessarily explaining their interactions with academic performance. For example, several studies employed salivary proteins to detect the body’s response to academic stress (Zallocco et al. 2021; Cai et al. 2018; Špiljak et al. 2024). Cardiovascular parameters were also widely used for detecting stress, depression, and anxiety across various studies (Nakamura et al. 2010; Abromavičius et al. 2023; Cronje et al. 2024). A portion of these studies used biological parameters to evaluate the impact of interventions aimed at reducing stress, anxiety, and depression (Harris et al. 2019; Mäkelä et al. 2023; Usichenko et al. 2020). Cortisol, one of the most frequently used parameters, was found to be associated with students’ academic stress levels (Anjum et al. 2021; Jamieson et al. 2021). However, not all researchers explored how these biological parameters are related to and can explain their implications for academic achievement.

We identified 12 studies that used 10 specific markers to discuss how academic stress biologically affects academic performance. Some of these parameters utilized neurophysiological, genetic, and epigenetic frameworks, linked to cognitive psychology and educational concepts. Table 2 presents the types of parameters, the sample sizes used, and a discussion based on their findings, which contribute to understanding the relationship between stress and academic performance.

Psychological instruments of stress measurement

All the studies analyzed employed psychological instruments to detect psychosocial stress related to academics. These tools allowed researchers to gather data on various aspects of mental health and behavior. The most frequently used instrument was the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), which appeared in 12 articles. The Abbreviated Mathematics Anxiety Scale (AMAS) was utilized in two articles to assess mathematics anxiety. Other anxiety instruments, such as the Test Anxiety Inventory (TAI), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), were also used, demonstrating validity and reliability across different populations. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) appeared in three articles to measure perceived stress levels. The SISCO Inventory of Academic Stress (SISCO) was employed in two articles to evaluate academic stress among university students, focusing on stressors, symptoms, and coping strategies. The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was used in four articles to gauge the intensity of various subjective experiences, including academic stress, depression, and anxiety. Additionally, the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) was employed in three articles to simultaneously measure depression, anxiety, and stress. Lastly, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), used in three articles, assessed the severity of depression (Table 3).

Approaches to data gathering

In analyzing the data collection methods used across the 31 articles reviewed, it is evident that various study designs were employed, reflecting diverse approaches to investigating academic stress and performance in biological contexts. The methods can be broadly categorized into experimental, observational, and mixed-method research. Table 4 summarizes the research designs, authors, and years of publication.

The crossover study design emerged as one of the most common approaches in experimental methods, accounting for 9.7% of all studies. This type of study, as conducted by Cardozo et al. (2023), Nakamura et al. (2010), and Usichenko et al. (2020), involves administering multiple interventions sequentially to participants. Blinded trial designs also accounted for 9.7% of all studies and were included in the research by Mäkelä et al. (2023), Márquez-Morales et al. (2021), and Kato-Kataoka et al. (2016). Within-subject and between-subject designs were used in studies by Zallocco et al. (2021), Brodersen and Lorenz (2020), and Pizzie et al. (2020), also comprising 9.7%. Quasi-experimental designs, as seen in Harris et al. (2019) and Cardozo et al. (2020), accounted for 6.4% of all studies. Špiljak et al. (2024) employed a prospective and interventional method, which was the only study of this type reviewed. Cai et al. (2018) was also the only study using randomized controlled trials (RCTs), considered the gold standard in experimental research due to their ability to minimize bias through randomization. Lastly, Abromavičius et al. (2023) applied measurement and modeling techniques, accounting for 3.2% of all studies. All articles employing interventions with this method are classified under the 1st level of prevention, focusing on programs aimed at mitigating academic stress before it escalates into a significant issue.

Observational study designs are a significant component of the reviewed articles, highlighting the importance of non-interventional approaches in understanding symptoms and the relationships between variables in natural conditions. Cross-sectional studies, including those by Cronje et al. (2024), Mujinya (2022), Tripathi et al. (2022), Ibrahim and Audi (2021), Tavakoli et al. (2017), and Kabrita and Hajjar-Muça (2016), are the most common observational design in the reviewed articles. Longitudinal studies, such as those conducted by Castillo-Navarrete et al. (2023), Cipra and Muller-Hilke (2019), Ringeisen et al. (2019), and Pradhan et al. (2014), involve repeated observations of the same variables over a period of time. Various observational designs, besides cross-sectional and longitudinal, were also employed in different studies. Wong et al. (2023) conducted a correlational study to identify associations between several stress and anxiety indicators and exam competence. Peter et al. (2023) used Ambulatory Assessment, Anjum et al. (2021) utilized a comparative study, Malanchini et al. (2020) conducted a twin study, Jamieson et al. (2021) employed a multilevel design, and Bedard et al. (2017) used a case-control study.

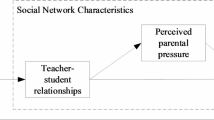

Conceptual framework of stress and performance

A variety of theoretical frameworks from different research areas, such as learning methods, neurophysiology, psychology, genetics, and epigenetics in studies of stress and academic performance, are illustrated in Table 5. We classified these theories based on the identified research clusters and categorized them according to the foundational theories or concepts associated with each cluster. In this way, we demonstrate that the association between stress and academic performance can be depicted from various theoretical perspectives. Furthermore, Fig. 2 illustrates a conceptual framework of stress and academic performance developed based on the analysis of scientific articles, providing a clear visualization of how different theories and concepts interact within the context of this research.

Of the 31 articles, only 74.18% (n = 23) discussed the theories they employed. The remaining 25.81% (n = 8) did not specifically mention the underlying theories of their research, possibly because the focus was not on forming a hypothesis-driven argument based on the relationship between stress, anxiety, depression and academic performance. The focus of these articles was on the detection or intervention to reduce academic-related stress, depression, or anxiety (Abromavičius et al. 2023; Anjum et al. 2021; Ibrahim and Audi, 2021; Kabrita and Hajjar-Muça, 2016; Nakamura et al. 2010; Tripathi et al. 2022; Usichenko et al. 2020; Zallocco et al. 2021).

Neurocognitive stress and performance

Wong et al. (2023) found that students who experienced higher stress levels with lower heart rate variability (HRV) actually had better academic performance. This finding suggests that when stress increases to an optimal level, students may become more focused on their tasks, thereby enhancing their performance. However, the anxiety assessment results in this study were not significant, indicating that students with high academic scores and lower HRV did not necessarily experience higher levels of stress. These students might possess effective coping strategies that help them manage stress despite having low HRV.

The study by Brodersen and Lorenz (2020) showed that perceived stress and salivary alpha-amylase were higher during exams compared to homework conditions, but there was no significant increase in cortisol levels. This indicates that exams trigger a high-stress response and activation of the sympathetic nervous system but do not activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPAA) response. Ringeisen et al. (2019) found that anxiety and cortisol levels increased on exam days compared to control days. Self-efficacy was found to be negatively correlated with anxiety and positively correlated with exam scores, suggesting that students with high self-efficacy perceive exams as challenges that can be overcome rather than threats.

Cai et al. (2018) found that the group receiving attention bias modification intervention showed a significant change in attention bias scores after training, but there was no significant change in salivary alpha-amylase levels. These findings suggest a reduction in attention towards stressors following training, although the lack of a well-validated psychosocial stressor may have contributed to the absence of significant changes in biological responses. Pradhan et al. (2014) reported that stress, measured through increased pulse rate, blood pressure, and reaction time, significantly affected students’ cognitive function before exams. Students with higher stress levels showed longer touch and audio reaction times, as well as faster visual reaction times, indicating that stress impacts the somatosensory cortex areas that process touch and visual stimuli.

Neurophysiology stress and performance

EEG analysis shows that stress and anxiety are associated with decreased alpha waves and increased delta waves in the left temporal lobe, which plays a crucial role in learning and memory processes (Cronje et al. 2024). This condition could potentially affect academic performance, where a decrease in alpha waves might indicate a reduced capacity for relaxation and focus, while an increase in delta waves may suggest disruption or inhibition in learning and memory processes. Studies also found a correlation between concentration, brain waves, and exam results, indicating that students who focus longer tend to achieve better grades or show significant improvement between exams (Kokubo and Shoji, 2017). Additionally, brain activity scans using fMRI evaluated activity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). The cognitive reappraisal process involves the PFC, a brain area responsible for executive functions like planning, decision-making, and cognitive control. Increased activity in the PFC can enhance the ability to focus, solve problems, and think critically, which are all essential for solving mathematical tasks (Pizzie et al. 2020).

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPAA) is involved in the systemic effects of stress, depression, and anxiety, which also play a role in the neurophysiology of cognition. Cortisol, as the primary stress hormone in the HPA axis, is one of the most widely used biomarkers in research related to academic stress (Anjum et al. 2021; Cardozo et al. 2020; Ringeisen et al. 2019; Kato-kataoka et al. 2016; Špiljak et al. 2024; Cardozo et al. 2023; Mäkelä et al. 2023; Peter et al. 2023; Jamieson et al. 2021; Brodersen and Lorenz, 2020; Ferreira et al. 2020; Cipra and Muller-Hilke, 2019). In stressful situations such as exam stress, serotonin, acetylcholine, and inflammatory cytokines are released as stress signals that activate the HPA axis (Hall et al. 2012). Stress signals also activate the sympathetic nervous system response, causing a positive feedback loop and a continuous cycle between the HPAA and the sympathetic nervous system (Hong et al. 2022). When the HPA axis is activated, stress hormones are released, including corticotropic releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus (Contoreggi, 2015), which then stimulates the anterior pituitary to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (Fukuoka et al. 2020). ACTH, in turn, regulates the production of glucocorticoids, such as cortisol, from the adrenal glands (Lightman et al. 2020). Elevated cortisol levels can negatively impact memory, attention, and executive functions, all of which are essential for academic performance (Ouanes and Popp, 2019). Stress hormones affect learning circuits through intermediary brain regions like the hippocampus, amygdala, and striatum tegmental nuclei, causing disruptions in the formation of strong memories (Cardozo et al. 2023).

Stress and epigenetic regulations

Stress can trigger epigenetic changes that affect gene expression and modulate the psychobiological response to stress (Stoffel et al. 2022). These changes involve DNA methylation of genes involved in the stress response and development (Unternaehrer and Meinlschmidt, 2016). Academic stress is believed to cause epigenetic changes that affect gene expression related to learning and memory, such as the BDNF gene (Castillo-Navarrete et al. 2023). Some studies use brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) as a biomarker of neuronal plasticity, linking explanations between academic performance and epigenetic regulation influenced by stress. BDNF plays a significant role in memory formation and processing through the regulation of synaptic plasticity, including synaptogenesis and long-term potentiation (LTP), the primary cellular mechanisms underlying learning and memory (Soliman et al. 2010; Karpova, 2014). Castillo-Navarrete et al. (2023) observed that academic stress could increase global DNA methylation percentage and decrease BDNF levels in blood plasma. Tavakoli et al. (2017) reported that male students with higher depression scores had lower BDNF levels.

Genetic variations and stress

Genetic variation, particularly the Val66Met polymorphism in the BDNF gene, can affect individual cognition and emotions (Al-Hatamleh et al. 2019; He et al. 2018). Bedard et al. (2017) found that individuals with low self-efficacy were more likely to have high depression compared to those with high self-efficacy, regardless of their BDNF genotype. The study also showed that individuals with the Val/Val genotype might have poor neurocognitive vulnerability to experiences of loneliness. Malanchini et al. (2020) observed 3410 pairs of identical and fraternal twins to separate the influence of genetic and environmental factors on traits related to attitudes and mathematical abilities. The study’s findings suggest that academic performance in mathematics is influenced by specific genetic variants for mathematics and is different from the genes regulating general academic performance.

Discussion

Certain parameters in the context of genetics and epigenetics can serve as potential biomarkers for understanding the complexity of academic performance. A polygenic analysis study of the NPS and NPSR1 genes found that neuroticism genetics can predict stress in high-pressure situations, such as academic exams (Peter et al. 2023). Tavakoli et al. (2017) utilized brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a crucial neurotrophic factor involved in the growth and maintenance of nerve cells in the brain. However, this study did not explain the implications of stress on learning and memory, which could affect academic performance. Similarly, studies examining gut microbiota diversity (Marquez-Morales et al. 2021; Kato-Kataoka et al. 2016) did not provide detailed explanations of how the gut–brain axis connection under stress conditions could influence academic performance.

The use of psychological instruments in these studies allowed researchers to collect comprehensive data on various aspects of mental health and behavior, facilitating the development of more effective interventions to address academic-related psychosocial stress. By assessing different dimensions of stress, anxiety, and depression, research has provided deeper insights into how these factors interact and impact individuals in both biological and academic contexts. Although the SISCO Inventory of Academic Stress is not the most widely used scale, its focus on stressors, symptoms, and coping strategies offers a comprehensive and targeted approach to assessing academic stress among university students (Castillo-Navarrete et al. 2024). This instrument, along with others, contributes to a nuanced understanding of academic stress and supports the development of targeted interventions to improve student well-being and academic performance.

The findings of this review underscore the multidimensional nature of academic stress, as evidenced by the significant interactions between biological markers, psychological coping strategies, and social influences identified across the studies analyzed. This aligns with the Bio-Psycho-Social paradigm (WHO, 2001), which emphasizes the integration of biological, psychological, and social factors in understanding stress and wellbeing. Key results reveal that markers such as BDNF and cortisol are highly sensitive to stress but show variability depending on psychological states and social contexts, such as peer support and institutional environment. These findings resonate with recent theoretical advancements, such as the conceptual model for managing stress and promoting wellbeing (de la Fuente et al. 2024), which integrates these dimensions into a cohesive framework.

The analysis of research designs employed across the reviewed studies provides significant insights into the methodologies used to explore academic stress and performance within biological contexts. Each design offers unique advantages and limitations, contributing to the overall understanding of the field. Despite the richness of insights provided by these designs, there remains a notable scarcity of mixed-method approaches in the literature. Mixed-methods research, which combines qualitative and quantitative techniques, has the potential to offer a more comprehensive perspective by integrating detailed numerical data with contextual understanding. Its underrepresentation suggests a missed opportunity to explore academic stress from both statistical and narrative perspectives, which could enrich our understanding of complex phenomena and lead to more nuanced interventions. Addressing this gap could enhance future research and provide a more holistic view of the interplay between academic stress and performance.

Theoretical underpinnings

The findings provide insights into how academic stress, measured through various biological parameters, can affect students’ academic performance and cognitive function. The findings by Wong et al. (2023) support the concept that stress at an optimal level can enhance academic performance by increasing focus, although the exact optimal level remains unclear. However, this also highlights that effective coping strategies play a crucial role in mitigating the negative impacts of stress, as seen in students with low HRV but high academic performance. These findings can be explained by the transactional theory of stress and coping by Lazarus and Folkman (1984).

The transactional theory of stress focuses on how individuals appraise and manage stress (Zhao et al. 2020; Spătaru et al. 2024). According to this theory, stress is not merely the result of external situations or stimuli, but also arises from an individual’s perception of the situation and their ability to cope with it. Several studies (Brodersen and Lorenz, 2020; Ringeisen et al. 2019) within the scope of this review have utilized this theoretical framework to explain the relationship between stress and academic performance, supported by evidence from biological parameters.

Brodersen and Lorenz (2020) underscore the role of HPAA adaptation in response to chronic stress, such as frequent exams, which may reduce cortisol response despite the activation of the sympathetic nervous system. This finding aligns with the concept of appraisal in transactional theory, where an individual’s perception of a situation influences their stress response. The findings from Ringeisen et al. (2019) emphasize the importance of self-efficacy in managing stress and improving academic performance. High self-efficacy can change the perception of exams from threats to manageable challenges, thereby reducing anxiety and enhancing performance.

Within the context of attention bias theory, the results from Cai et al. (2018) indicate that attention bias modification interventions can reduce attention toward stressors, although effects on biological parameters like alpha-amylase may require clearer and more validated stress conditions to demonstrate significant changes. This suggests that the effectiveness of interventions depends on the validity and intensity of the stressors used.

The execution focus model employed by Pradhan et al. (2014) also confirms that stress affects how the brain processes information, reflected in changes in reaction times. While there is general support for the role of reaction time in academic performance, the differing results in this study may reflect variations in coping strategies or optimal stress levels that have not been fully explained, indicating a need for further research to understand these complex relationships.

The results from EEG and fMRI analyses indicate the importance of brain regions like the left temporal lobe and prefrontal cortex in academic performance under stress. The decrease in alpha waves and increase in delta waves observed in the EEG studies (Cronje et al. 2024) suggest that stress can interfere with brain functions associated with learning and memory, potentially reducing students’ ability to perform academically. Furthermore, the increased activity in the prefrontal cortex during cognitive reappraisal (Pizzie et al. 2020) highlights the role of executive functions in managing stress and performing complex cognitive tasks, such as mathematics. This suggests that training students in cognitive strategies that enhance PFC activity could potentially improve their academic outcomes.

The findings on HPAA’s role in stress response highlight its significance in academic settings where stress levels are often high. Although there is strong evidence of cortisol’s negative impact on cognitive function (Ouanes and Popp, 2019), the inconsistencies in findings regarding cortisol’s relationship with exam performance (Ferreira et al. 2020; Ringeisen et al. 2019) suggest that cortisol alone may not be a definitive predictor of academic outcomes. Factors such as different cortisol measurement methods, individual differences in stress responses, and variations in exam environments could contribute to these inconsistencies. Understanding how the HPAA and sympathetic nervous system influence academic performance has important implications for education. Providing adequate resources for counseling units and training students on stress management strategies have been recommended to address high levels of academic stress among students (Munyaradzi and Addae, 2018). Implementing strategies to foster a more conducive academic environment has been suggested based on the predictive relationship between stress coping, self-efficacy, and academic satisfaction (Estrada-Araoz et al. 2024).

The discussion on epigenetic changes driven by stress underscores the complexity of how academic stress impacts cognitive functions at the molecular level. Epigenetic regulation, such as BDNF gene methylation, suggests that the effects of stress on students are not only evident in their psychological and physiological responses but also at a deeper molecular level, ultimately influencing academic performance and cognitive abilities. Understanding these epigenetic mechanisms is crucial for explaining how stress can impact learning and memory abilities in students.

The research on genetic variations and academic performance extends the scope of studies on the genetic factors influencing academic potential. It is suggested that different academic potentials in individuals may be influenced by different genes (Rimfeld et al. 2015). Understanding how genetic variability can affect stress responses could lead to the development of more tailored and personalized interventions to help individuals manage stress more effectively, particularly in high-pressure environments like exams (Peter et al. 2023).

Overall, the findings from these studies support the importance of biological parameters in measuring stress responses and suggest that academic stress can affect performance in complex, context-dependent ways. This emphasizes the need for a multidimensional approach to understanding the impact of academic stress on student performance. To provide a comprehensive understanding of the intricate relationships among various factors influencing academic stress and performance, a conceptual framework is illustrated in Fig. 2. This framework synthesizes findings from the analyzed studies, highlighting the interconnected roles of neurophysiological mechanisms, epigenetic regulations, genetic variations, and other psychological factors in shaping academic outcomes.

Future research directions

Research on the association between stress, anxiety, and depression with academic performance has evolved rapidly and has been examined from various perspectives. From our review, however, we argue that several areas require further exploration to enhance our understanding of the complexity of academic performance as an outcome of various interrelated factors and study contexts. To provide recommendations for forthcoming research, we evaluated the limitations and explored the potential and gaps from studies over the past three years included in our analysis. This procedure resulted in three major potential research agendas, as discussed below.

Academic performance and stress mechanism

Efforts to uncover the influence of stress on academic performance have been the focus of many studies. Various biomarkers have been used to identify changes in the body’s biological functions when an individual experiences stress. Nonetheless, our understanding of the biological mechanisms linking stress to academic performance remains incomplete. Future studies need to investigate the biological processes influencing academic performance and use biomarkers that can more closely explain the relationship between stress mechanisms and academic performance (Cronje et al. 2024; Castillo-Navarrete et al. 2023; Peter et al. 2023).

The use of cardiovascular parameters as markers of stress presence is widespread in research (Anjum et al. 2021; Usichenko et al. 2020; Zallocco et al. 2021). However, cardiovascular parameters cannot directly explain how stress, whether acute or chronic, affects academic performance. While stress can trigger cardiovascular responses, its effects on memory, concentration, and cognitive abilities are more influenced by how stress interacts with the central nervous system and involves various hormones (Lindau et al. 2016; Vogel and Schwabe, 2016). Cardiovascular parameters are part of a series of processes initiated in the brain, impacting the body’s readiness for a ‘fight or flight’ response to pressure (Shah et al. 2019).

The detection of neurophysiological signals, such as electrodermal activity (Abromavičius et al. 2023), electroencephalogram (EEG) (Cronje et al. 2024), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) (Pizzie et al. 2020), has also been used in several studies analyzed and contributes to the understanding of the relationship between stress and central and autonomic nervous system activities. Measurement techniques using such parameters have drawbacks; they are time-consuming and can introduce bias due to the potential stress caused by sensor placement or participation in experiments (Jiménez-Mijangos et al. 2023). To obtain accurate and comprehensive results, we suggest using non-invasive biomarkers in more natural settings.

Cortisol, the primary stress hormone involved in mechanisms in the central nervous system, is the most widely used parameter in the analyzed studies. Cortisol levels are known to be associated with student stress (Anjum et al. 2021; Cardozo et al. 2020; Ringeisen et al. 2019). The advantage of this parameter is its ability to be measured non-invasively from urine (Borghi et al. 2021), saliva (Kato-Kataoka et al. 2016), and hair (van den Heuvel et al. 2022; Heming et al. 2023; Romero-Romero et al. 2023). However, inconsistencies in study results regarding the effects of stress on cortisol levels and academic performance necessitate further research (Brodersen and Lorenz, 2020; Ferreira et al. 2020; Ringeisen et al. 2019; Cipra and Muller-Hilke, 2019). Recognizing the complexity of academic performance as a result of interactions among various factors, not just physiological but also psychological and social, we suggest that upcoming studies consider an interdisciplinary approach.

Based on the analysis of existing studies, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) emerges as a promising biomarker in elucidating the influences of psychological factors and educational strategies on academic performance. BDNF is a neurotrophin abundantly expressed in the brain and plays a critical role in the survival, growth, and cognitive function of neurons under normal and neuropathological conditions (Ismail et al. 2020). This marker can also be measured non-invasively through urine (Olivas-Martinez et al. 2023) and saliva (Ballestar-Tarín et al. 2024), making it more comfortable for participants and reducing the risk of stress bias due to plasma sampling procedures. Additionally, it facilitates repeated sampling in longitudinal study designs or ambulatory assessment.

In the context of academic stress, peripheral BDNF levels may fluctuate, with the potential for significant decreases in students facing chronic academic pressure (Castillo-Navarrete et al. 2023; Tavakoli et al. 2017). In other studies, acute stress induced by academic exams increased BDNF production (Myint et al. 2021). These varied findings present opportunities to explore BDNF as a potential biomarker in understanding how effective management strategies and assessments can mitigate the negative impacts of academic stress on academic performance.

Given the potential of BDNF as a biomarker for academic performance, it is essential to conduct in-depth studies on the genetic and epigenetic regulation that influences BDNF synthesis. Polymorphisms in the BDNF gene have been associated with variations in cognitive performance, particularly in tasks involving psychomotor speed, working memory, and executive function (Dowlati et al. 2020; Wiłkość et al. 2016). The BDNF Val66Met gene polymorphism is also linked to mental health, which can affect academic performance (Bedard et al. 2017). These genetic factors can provide insights into how individuals respond differently to academic stress, which in turn can influence optimal learning strategies and curriculum adjustments to enhance academic outcomes.

Beyond genetic regulation, epigenetic aspects also play a crucial role in BDNF expression and could be an area for further exploration in educational research. Epigenetic regulation, such as global DNA methylation, MeCP2, and various non-coding RNAs, has been shown to influence BDNF expression (Castillo-Navarrete et al. 2023; Lee et al. 2019; Lipovich et al. 2012; Modarresi et al. 2021). Research in this area could provide new insights into how educational environments and social experiences interact with biological factors to shape students’ academic performance. This has implications for developing more effective educational interventions that not only focus on cognitive aspects but also consider individual biological aspects in supporting optimal academic performance.

Research on educational interventions

Cardozo et al. (2023) found that implementing active learning methods combined with formative assessments can reduce exam stress and anxiety and improve students’ academic performance compared to traditional lecture methods. These results indicate that more interactive and student-centered approaches have the potential to create a more conducive learning environment and support better academic achievement (Angraini, et al. 2023). For instance, learning that uses the joyful-inquiry interactive demonstration model assisted by Android games has been shown to improve students’ cognitive learning outcomes by engaging them more actively in the learning process (Mustikasari et al. 2020). Additionally, Dou et al. (2018) and Muntholib et al. (2024) argue that students’ self-efficacy is influenced by the learning strategies or models implemented. Specifically, learning models that accommodate active student participation in investigating topics can enhance self-efficacy. This investigative process allows students to build confidence through active class discussions and presenting their findings to peers, fostering strong problem-solving skills (Fitriani et al. 2020).

Furthermore, self-efficacy has become a trending variable in the application of collaborative science learning over the past decade. It is frequently associated with motivation, learning systems, and e-learning. These findings indicate that integrating self-efficacy into various learning models, especially in STEM fields, holds significant promise for enhancing students’ engagement and performance in the classroom (Marlina et al. 2024).

However, further research is needed, especially longitudinal studies, to observe the long-term impact of these active methods. Additionally, it is essential to explore various variations of active learning methods and evaluate their effectiveness, including integration with technology, to identify the most effective approaches for application in different educational contexts. Developing and evaluating these methods is crucial to help students manage stress and improve their academic performance (Cardozo et al. 2023; Wong et al. 2023). The crucial role of self-efficacy in student success and its connections to psychological, physiological, and educational aspects, highlights the need for further interdisciplinary research into this area.

Several studies suggest that the impact of stress on academic achievement may vary and may be influenced by various factors (Brodersen and Lorenz, 2020; Ferreira et al. 2020; Wong et al. 2023). The influence of stress on academic performance is not linear and can be affected by other factors such as self-efficacy, motivation, individual learning approaches, and emotional intelligence (Ferreira et al. 2020; Ringeisen et al. 2019; Wong et al. 2023; Cipra and Muller-Hilke, 2019; MacCann et al. 2022). These findings suggest that subsequent studies should consider these variables to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between stress and academic performance. Thus, a holistic approach to examining the interaction between stress and other psychological factors can provide deeper insights into efforts to improve student academic achievement.

Another approach to reducing the negative impact of stress and enhancing students’ well-being is through the development of educational programs that encourage students’ connection to nature and their knowledge of environmental issues (Sulfa et al. 2024). These programs have the potential to benefit not only students’ mental health but also increase their awareness and responsibility toward the environment. Continued inquiry could explore the potential of this intervention in learning practices, particularly in the natural sciences, to assess its impact on reducing academic stress and improving students’ well-being and academic performance.

Prospective research should develop predictive models based on individuals’ biological responses to stress, as suggested by Abromavičius et al. (2023). Predictive models can help identify individuals more susceptible to stress and potentially experiencing declines in academic performance. Additionally, it is essential to develop interventions tailored to individual needs, as proposed by Peter et al. (2023). A more personalized approach to intervention strategies is likely to yield more optimal results because it can accommodate individual variations in response to stress and their psychological needs. This approach requires a deep understanding of the biological and psychological factors contributing to stress so that interventions are truly effective in reducing the negative impact of stress on academic performance (Lee et al. 2019).

Interdisciplinary approach

From the eligibility analysis of 222 studies included in the topic analysis, only 31 studies combined biological and psychological approaches in examining the topic of stress and academic performance (Fig. 1). Further content analysis showed that only 12 of these studies genuinely integrated interdisciplinary approaches in the analysis and discussion of their research findings (Table 2). This indicates a gap in more holistic approaches, considering that academic achievement is highly likely influenced by interactions among various factors, including genetics, epigenetic regulation, and environment (Lee et al. 2019). Indeed, some reviewed studies focused more on biological studies without comprehensively linking them to psychological and social aspects (Abromavičius et al. 2023; Kabrita and Hajjar-Muça, 2016; Špiljak et al. 2024).

Most of the analyzed studies predominantly employed quantitative methods, including both experimental and observational approaches (Table 4). Only one study adopted a mixed-method approach in its methodology (Ferreira et al. 2020). This limitation may hinder the generation of findings that are more generalizable and relevant across various contexts. While quantitative approaches promise standardization, control, reliability, and a stronger basis for making causal claims, qualitative approaches offer a broader context, phenomenological understanding, and insights into behavioral complexities (Sockolow et al. 2016). Therefore, the use of mixed methods is highly recommended for ongoing explorations to achieve a broader perspective, a more in-depth analysis, and a better understanding of the complexities of education and cognition (Poortinga and Fontaine, 2022). For example, a comprehensive mixed-method study that combined electrodermal activity (EDA) measurements with qualitative analysis of video recordings of the learning process revealed that hands-on learning, which is generally assumed to foster higher student engagement, could actually trigger more stress rather than productive involvement (Sung et al. 2023). This serves as a concrete example of how mixed-method research can enhance the understanding of academic stress.

A more comprehensive methodology can also minimize bias associated with self-report measurements in psychological instruments. Next step in the research should consider incorporating more objective measures to complement self-reported data. In addition to objective measures such as physically or physiologically measured data, direct observations by researchers, which are less influenced by respondents’ personal perceptions, are also recommended.

Additionally, current interventions tend to be limited and are not yet integrated with strategies aimed at holistically enhancing academic performance. Hence, interdisciplinary studies that not only rely on quantitative data but also involve qualitative approaches are needed to address the complexities of academic performance (Rodríguez-Torres et al. 2024; Vajaradul et al. 2021). Anticipated studies should focus not only on identifying stress within academic environments (Acevedo et al. 2021; Jiménez-Mijangos et al. 2023; Shanbhog and Medikonda, 2023), but also on evaluating the impact of interventions from a broader perspective (Špiljak et al. 2024; Mäkelä et al. 2023). This will pave the way for developing more effective and relevant interventions tailored to the needs of students.

Limitations of the study

Although this study successfully identified several significant findings regarding the relationship between stress, depression, and anxiety with academic performance among university students, there are some limitations that should be noted. The limitation of using only the Scopus database restricts the scope of the study. The diversity of articles on the Web of Science could offer different perspectives. It is recommended to incorporate additional databases in future directions to enhance the breadth and accuracy of the findings. The restriction of the search to English-language and open-access articles could potentially overlook relevant studies published in other languages or hidden behind paywalls of subscription-based journals. Additionally, the strict inclusion criteria, such as focusing solely on university students, may limit the generalizability of the findings. Prospective research should explore academic stress across different educational levels to provide a more comprehensive understanding. Nevertheless, the results of this analysis provide a strong foundation for further research on this topic.

Conclusion

This study reviewed literature exploring the relationship between academic stress and academic performance through a structured literature review, employing content analysis techniques. From this analysis, we identified three key aspects in the literature, encompassing biological parameters, psychological instruments, and research methodologies used. Commonly utilized biological parameters include cardiovascular measures, cortisol hormone levels, and salivary α-amylase. We also found several psychological instruments frequently used to measure stress, anxiety, and depression among university students. In terms of methodology, the research generally employed quantitative approaches and rarely applied mixed-method approaches.

As key findings, this study identifies two important points. First, there are four main theoretical foundations that can be used to understand the interaction between stress and academic performance in the context of biology and education: the neurophysiology of cognition and emotion, stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, stress and epigenetic regulation, and genetic variation and stress. Second, we recommend three future directions emphasizing the development of students’ academic performance. Further studies should focus on understanding the mechanisms of stress and academic performance, educational interventions, and interdisciplinary research approaches. These findings are expected to guide future studies in the fields of education and psychology to optimize students’ academic performance through a deeper understanding of the impact of stress.

Data availability

All data is available in the published literature of the primary source.

References

Abromavičius V, Serackis A, Katkevičius A, Kazlauskas M, Sledevič T (2023) Prediction of exam scores using a multi-sensor approach for wearable exam stress dataset with uniform preprocessing. Technol Health Care 31(6):2499–2511. https://doi.org/10.3233/THC-235015

Acevedo CMD, Gómez JKC, Rojas CAA (2021) Academic stress detection on university students during COVID-19 outbreak by using an electronic nose and the galvanic skin response. Biomed Signal Process Control 68:102756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2021.102756

Al-Hatamleh MA, Hussin TM, Taib WR, Ismail I (2019) The brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene Val66Met (rs6265) polymorphism and stress among preclinical medical students in Malaysia. J Taibah Univ Med Sci 14(5):431–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2019.09.003

Ali N, Nater UM (2020) Salivary alpha-amylase as a biomarker of stress in behavioral medicine. Int J Behav Med 27:337–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-019-09843-x

Almarzouki AF (2024) Stress, working memory, and academic performance: a neuroscience perspective. Stress 27(1):2364333. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2024.2364333

Amhare AF, Jian L, Wagaw LM, Qu C, Han J (2021) Magnitude and associated factors of perceived stress and its consequence among undergraduate students of Salale University, Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. Psychol Health Med 26(10):1230–1240. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1808234

Anjum A, Anwar H, Sohail MU, Ali Shah SM, Hussain G, Rasul A, Shahzad A (2021) The association between serum cortisol, thyroid profile, paraoxonase activity, arylesterase activity and anthropometric parameters of undergraduate students under examination stress. Eur J Inflamm 19:20587392211000884. https://doi.org/10.1177/20587392211000884

Angraini E, Zubaidah S, Susanto H (2023) TPACK-based active learning to promote digital and scientific literacy in genetics. Pegem J Educ Instr 13(2):50–61. https://doi.org/10.47750/pegegog.13.02.07

Armario A, Labad J, Nadal R (2020) Focusing attention on biological markers of acute stressor intensity: empirical evidence and limitations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 111:95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.01.013

Ballestar-Tarín ML, Ibáñez-del Valle V, Mafla-España MA, Navarro-Martínez R, Cauli O (2024) Salivary brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cortisol associated with psychological alterations in University students. Diagnostics 14(4):447. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14040447

Barbayannis G, Bandari M, Zheng X, Baquerizo H, Pecor KW, Ming X (2022) Academic stress and mental well-being in college students: correlations, affected groups, and COVID-19. Front Psychol 13:886344. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.886344

Bedard M, Woods R, Crump C, Anisman H (2017) Loneliness in relation to depression: the moderating influence of a polymorphism of the brain derived neurotrophic factor gene on self-efficacy and coping strategies. Front Psychol 8:1224. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01224

Bedewy D, Gabriel A (2015) Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: the Perception of Academic Stress Scale. Health Psychol Open 2(2):2055102915596714. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102915596714

Boell SK, Cecez-Kecmanovic D (2015) On being ‘systematic’in literature reviews in IS. J Inf Technol 30(2):161–173. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2014.26

Borghi F, da Silva PC, Canova F, Souza AL, Arouca AB, Grassi-Kassisse DM (2021) Acute and chronic effects of exams week on cortisol production in undergraduate students. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.23.432585

Briones NGP, Vázquez KR, Reyes BJL, Melasio DAG, Lara AR, Hernández PET (2024) Clinical practice stressors and anxiety in nursing students during COVID-19. Salud Mental 46(6):287–293. https://doi.org/10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2023.037

Brodersen L, Lorenz R (2020) Perceived stress, physiological stress reactivity, and exit exam performance in a prelicensure Bachelor of Science nursing program. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh 17(1):20190121. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijnes-2019-0121

Cai W, Pan Y, Chai H, Cui Y, Yan J, Dong W, Deng G (2018) Attentional bias modification in reducing test anxiety vulnerability: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 18:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1517-6

Cardozo LT, Azevedo MARD, Carvalho MSM, Costa R, de Lima PO, Marcondes FK (2020) Effect of an active learning methodology combined with formative assessments on performance, test anxiety, and stress of university students. Adv Physiol Educ 44(4):744–751. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00075.2020

Cardozo LT, Lima POD, Carvalho MSM, Casale KR, Bettioli AL, Azevedo MARD, Marcondes FK (2023) Active learning methodology, associated to formative assessment, improved cardiac physiology knowledge and decreased pre-test stress and anxiety. Front Physiol 14:1261199. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2023.1261199

Castillo-Navarrete J, Bustos C, Guzman-Castillo A, Vicente B (2023) Increased academic stress is associated with decreased plasma BDNF in Chilean college students. PeerJ 11:e16357. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.16357

Castillo-Navarrete JL, Bustos C, Guzman-Castillo A, Zavala W (2024) Academic stress in college students: descriptive analyses and scoring of the SISCO-II inventory. PeerJ 12:e16980. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.16980

Cipra C, Müller-Hilke B (2019) Testing anxiety in undergraduate medical students and its correlation with different learning approaches. PLoS ONE 14(3):e0210130. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210130

Contoreggi C (2015) Corticotropin releasing hormone and imaging, rethinking the stress axis. Nucl Med Biol 42(4):323–339

Córdova Olivera P, Gasser Gordillo P, Naranjo Mejía H, La Fuente Taborga I, Grajeda Chacón A, Sanjinés Unzueta A (2023) Academic stress as a predictor of mental health in university students. Cogent Educ 10(2):2232686. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2232686

Cronje R, Beukes J, Masenge A, du Toit P, Bipath P (2024) Investigation of neopterin and neurophysiological measurements as biomarkers of anxiety and stress. NeuroRegulation 11(1):25–25. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.11.1.25

De la Fuente J, González-Torres MC, Aznárez-Sanado M, Martínez-Vicente JM, Peralta-Sánchez FJ, Vera MM (2019) Implications of unconnected micro, molecular, and molar level research in psychology: the case of executive functions, self-regulation, and external regulation. Front Psychol 10:1919. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01919

De la Fuente J, Martínez-Vicente JM (2024) Conceptual Utility Model for the Management of Stress and Psychological Wellbeing, CMMSPW™ in a university environment: theoretical basis, structure and functionality. Front Psychol 14:1299224. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1299224

Dou R, Brewe E, Potvin G, Zwolak JP, Hazari Z (2018) Understanding the development of interest and self-efficacy in active-learning undergraduate physics courses. Int J Sci Educ 40(13):1587–1605

Dowlati MA, Shayan A, Zar A (2020) The effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor single nucleotide polymorphism on cognitive factors. Middle East J Rehabil Health Stud. 7(3). https://doi.org/10.5812/mejrh.101559

Estrada-Araoz EG, Larico-Uchamaco GR, Roman-Paredes NO, Ticona-Chayña E (2024) Coping with stress and self-efficacy as predictors of academic satisfaction in a sample of university students. Salud Cienc Tecnol 4:840–840. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2024840

Ferreira ÉDMR, Pinto RZ, Arantes PMM, Vieira ÉLM, Teixeira AL, Ferreira FR, Vaz DV (2020) Stress, anxiety, self-efficacy, and the meanings that physical therapy students attribute to their experience with an objective structured clinical examination. BMC Med Educ 20:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02202-5

Fitriani A, Zubaidah S, Susilo H, Al Muhdhar MHİ (2020) The effects of integrated problem-based learning, predict, observe, explain on problem-solving skills and self-efficacy. Eurasian J Educ Res 20(85):45–64

Fukuoka H, Shichi H, Yamamoto M, Takahashi Y (2020) The mechanisms underlying autonomous adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion in Cushing’s disease. Int J Mol Sci 21(23):9132

Hall JM, Cruser D, Podawiltz A, Mummert DI, Jones H, Mummert ME (2012) Psychological stress and the cutaneous immune response: roles of the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Dermatol Res Pract 2012(1):403908

Harb H, Gonzalez-De-La-Vara M, Thalheimer L, Klein U, Renz H, Rose M, Peters EMJ (2017) Assessment of brain derived neurotrophic factor in hair to study stress responses: a pilot investigation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 86:134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.09.007

Harris RB, Grunspan DZ, Pelch MA, Fernandes G, Ramirez G, Freeman S (2019) Can test anxiety interventions alleviate a gender gap in an undergraduate STEM course? CBE—Life Sci Educ 18(3):ar35. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-05-0083

He SC, Wu S, Wang C, Du XD, Yin G, Jia Q, Zhang XY (2018) Interaction between job stress and the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism affects depressive symptoms in Chinese healthcare workers. J Affect Disord 236:157–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.089

Heming M, Angerer P, Apolinário-Hagen J et al. (2023) The association between study conditions and hair cortisol in medical students in Germany—a cross-sectional study. J Occup Med Toxicol 18:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-023-00373-7

Hermann R, Schaller A, Lay D, Bloch W, Albus C, Petrowski K (2021) Effect of acute psychosocial stress on the brain-derived neurotrophic factor in humans—a randomized cross within trial. Stress 24(4):442–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2020.1854218

Hong Y, Zhang L, Liu N, Xu X, Liu D, Tu J (2022) The central nervous mechanism of stress-promoting cancer progression. Int J Mol Sci 23(20):12653

Ibrahim JN, Audi L (2021) Anxiety symptoms among Lebanese health-care students: prevalence, risk factors, and relationship with vitamin D status. J Health Sci 11(1):29–36. https://doi.org/10.17532/jhsci.2021.1191

Ismail NA, Leong Abdullah MFI, Hami R, Ahmad Yusof H (2020) A narrative review of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) on cognitive performance in Alzheimer’s disease. Growth Factors 38(3-4):210–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/08977194.2020.1864347

Jahan SS, Nerali JT, Parsa AD, Kabir R (2022) Exploring the association between emotional intelligence and academic performance and stress factors among dental students: a scoping review. Dent J 10(4):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj10040067

Jamieson JP, Black AE, Pelaia LE, Reis HT (2021) The impact of mathematics anxiety on stress appraisals, neuroendocrine responses, and academic performance in a community college sample. J Educ Psychol 113(6):1164. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000636

Javaid ZK, Chen Z, Ramzan M (2024) Assessing stress causing factors and language related challenges among first year students in higher institutions in Pakistan. Acta Psychol 248:104356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104356

Jiang R, Babyak MA, Brummett BH, Siegler IC, Kuhn CM, Williams RB (2017) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66Met polymorphism interacts with gender to influence cortisol responses to mental stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 79:13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.02.005

Jiménez-Mijangos LP, Rodríguez-Arce J, Martínez-Méndez R et al. (2023) Advances and challenges in the detection of academic stress and anxiety in the classroom: a literature review and recommendations. Educ Inf Technol 28:3637–3666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11324-w

Kabrita CS, Hajjar-Muça TA (2016) Sex-specific sleep patterns among university students in Lebanon: impact on depression and academic performance. Nat Sci Sleep 8:189–196. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S104383

Karpova NN (2014) Role of BDNF epigenetics in activity-dependent neuronal plasticity. Neuropharmacology 76(Part C):709–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.002

Kato-Kataoka A, Nishida K, Takada M, Kawai M, Kikuchi-Hayakawa H, Suda K, Rokutan K (2016) Fermented milk containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota preserves the diversity of the gut microbiota and relieves abdominal dysfunction in healthy medical students exposed to academic stress. Appl Environ Microbiol 82(12):3649–3658. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.04134-15

Kokubo Y, Shoji Y (2017) Relationship between good grades and brain waves. In: Matsuo T, Fukuta N, Mori M, Hashimoto K, Hirokawa S (eds) 2017 6th IIAI International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics (IIAI-AAI). IEEE, Conference Publishing Services, pp. 687–690

La Rovere MT, Gorini A, Schwartz PJ (2022) Stress, the autonomic nervous system, and sudden death. Auton Neurosci 237:102921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102921

Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company, New York

Lee LC, Su MT, Cho YC, Lee‐Chen GJ, Yeh TK, Chang CY (2019) Multiple epigenetic biomarkers for evaluation of students’ academic performance. Genes Brain Behav 18(5):e12559

Lightman SL, Birnie MT, Conway-Campbell BL (2020) Dynamics of ACTH and cortisol secretion and implications for disease. Endocr Rev 41(3):bnaa002. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnaa002

Lindau M, Almkvist O, Mohammed AH (2016) Effects of stress on learning and memory. In: Fink G (ed) Stress: concepts, cognition, emotion, and behavior. Academic Press, pp. 153–160

Linz R, Puhlmann LMC, Apostolakou F, Mantzou E, Papassotiriou I, Chrousos GP, Singer T (2019) Acute psychosocial stress increases serum BDNF levels: an antagonistic relation to cortisol but no group differences after mental training. Neuropsychopharmacology 44(10):1797–1804. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0391-y

Lipovich L, Dachet F, Cai J, Bagla S, Balan K, Jia H, Loeb JA (2012) Activity-dependent human brain coding/noncoding gene regulatory networks. Genetics 192(3):1133–1148. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.112.145128

MacCann C, Double KS, Clarke IE (2022) Lower avoidant coping mediates the relationship of emotional intelligence with well-being and ill-being. Front Psychol 13:835819. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.835819

Mäkelä SM, Griffin SM, Reimari J, Evans KC, Hibberd AA, Yeung N, Patterson E (2023) Efficacy and safety of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei Lpc-37® in students facing examination stress: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial (the ChillEx study). Brain Behav Immun-Health 32:100673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2023.100673

Malanchini M, Rimfeld K, Wang Z, Petrill SA, Tucker-Drob EM, Plomin R, Kovas Y (2020) Genetic factors underlie the association between anxiety, attitudes and performance in mathematics. Transl Psychiatry 10(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-0711-3

Marlina R, Suwono H, Ibrohim I, Yuenyong C, Husamah H, Hamdani H (2024) Theoretical frameworks of self-efficacy in collaborative science learning practices: a systematic literature review. J Pendidik Biol Indones10(2):602–615

Márquez-Morales L, El-Kassis EG, Cavazos-Arroyo J, Rocha-Rocha V, Martínez-Gutiérrez F, Pérez-Armendáriz B (2021) Effect of the intake of a traditional Mexican beverage fermented with lactic acid bacteria on academic stress in medical students. Nutrients 13(5):1551. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051551

Mayya SS, Martis M, Mayya A, Iyer VLR, Ramesh A (2022) Academic stress among pre-university students of the commerce stream: a study in Karnataka. Pertanika J Soc Sci Humanit 30(2). https://doi.org/10.47836/pjssh.30.2.10

Modarresi F, Fatemi RP, Razavipour SF, Ricciardi N, Makhmutova M, Khoury N, Faghihi MA (2021) A novel knockout mouse model of the noncoding antisense Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (Bdnf) gene displays increased endogenous Bdnf protein and improved memory function following exercise. Heliyon 7(7):e07570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07570

Mujinya R, Kalange M, Ochieng JJ, Ninsiima HI, Eze ED, Afodun AM, Kasozi KI (2022) Cerebral cortical activity during academic stress amongst undergraduate medical students at Kampala International University (Uganda). Front Psychiatry 13:551508. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.551508

Muntholib M, Muhdhar MHIA, Zahro SM, Abdillah RR, Astuti L, Wardhani YS, … & Achmad R (2024) The effect of inquiry social complexity (ISC)-based adiwiyata e-module on self-efficacy and environmental literacy. In: Habiddin H, Roncevic T (eds) AIP conference proceedings, vol 3106(1). AIP Publishing

Munyaradzi M, Addae D (2018) Effectiveness of student psychological support services at a technical and vocational education and training college in South Africa. Community College J Res Practice 43(4):262–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2018.1456379

Mustikasari VR, Suwono H, Farhania K (2020) Improving students’ science learning outcomes through joyful-inquiry interactive demonstration assisted by game android. In: Habiddin H, Majid S, Ibnu S, Farida N, Dasna IW (eds) AIP conference proceedings, vol 2215(1). AIP Publishing

Myint K, Jacobs K, Myint AM, Lam SK, Henden L, Hoe SZ, Guillemin GJ (2021) Effects of stress associated with academic examination on the kynurenine pathway profile in healthy students. PLoS ONE 16(6):e0252668