Abstract

Working time reduction (WTR), particularly in the form of a four-day workweek, has emerged as a topical issue in the future-of-work discourse amplified by the Covid-19 pandemic. This is relevant from a sustainability perspective since WTR has long been considered as potentially beneficial for the environment. Utilising Framing Theory, we study the characteristics of the current online, written media discourse of WTR that matter for sustainability. Based on 3617 English language news pieces and 156 advocacy documents, we find that the discourse focuses on a single type of WTR which leaves aggregate production and consumption unchanged. This is the least adversarial type of WTR, but its environmental benefits are very limited. The presentation of its feasibility and impacts is overly positive and scientifically unfounded. We suggest that this hinders learning from difficulties and hides unavoidable conflicts of more widespread WTRs. To achieve more transformative change, we advocate for the inclusion of new voices, more confrontational strategies and a disaggregated view of the labour force.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spending less time on paid work may serve human well-being, economic prosperity and environmental sustainability, depending on the specific context and conditions of implementation (Gomes, 2021; Grosse, 2018; Schor, 2010). From a sustainability perspective, which is our focus in this article, working time reductions (WTRs) are relevant because they can affect the volume and composition of production and consumption (Knight et al., 2013). Characteristics of WTR schemes, such as their magnitude, timing and financial conditions, affect impacts, which occur through changes in time use and associated money flows (King and van den Bergh, 2017; Nässén and Larsson, 2015).

At the macro level, WTRs may be add-ons to technological strategies in less radical ‘green growth’ approaches that try to combine environmental targets with economic growth, or core strategies to sustainably reduce production in ‘post-growth’ scenarios that aim to achieve well-being without economic growth (Cieplinski et al., 2021). In fact, post-growth futures avoiding significant unemployment are virtually impossible without substantial WTRs unless average productivity growth abruptly reverses, because producing less with a more efficient workforce requires less labour input (Jackson and Victor, 2011). Therefore, post-growth thinking motivated by the implausibility of sufficiently fast decoupling between economic output and environmental impacts should strongly focus on WTR discussions (Antal, 2014).

The attraction of WTRs is partly linked to their perceived feasibility, especially when compared to other post-growth policy proposals and extreme geoengineering technologies widely assumed in growth-oriented climate change mitigation scenarios (Anderson and Peters, 2016; Antal, 2018; Cosme et al., 2017). WTRs can be popular with workers, some employers launch their own schemes without external pressure and even countries have started experiments. Historical examples of shortening working hours, such as the emergence of the 40-h workweek a century ago, also offer inspiration for the present day. In addition, generational changes in work-life priorities towards less work-centred lives (Méda and Vendramin, 2017) have been amplified by trends such as the ‘great resignation’ and ‘quiet quitting’ following the Covid-19 pandemic (Lee et al., 2024). As a result, recent media discussions of WTRs have been lively (Veal, 2023a).

According to Framing Theory, this discourse matters for the future of work because the media shapes how possibilities and strategies for changing working hours are imagined. By highlighting certain aspects of a complex reality and downplaying others, media frames—understood as the specific perspectives taken—promote particular definitions of the topic at hand, interpretations of its causal mechanisms and feasible actions for stakeholders (Entman, 1993). Emphasis framing, as it is more accurately called (Cacciatore et al., 2015), systematically affects how news is understood, even if individual perceptions of reality differ because they also involve personal experiences and interactions with peers (Iyengar, 1991; Neuman et al., 1992). While the attitudes and behaviours of audiences also influence the perceptions and circumstances of journalists who build the frames (Scheufele, 1999), a large number of studies concentrate exclusively on the process through which media frames affect audience perspectives. This is called frame setting, and its importance has been widely acknowledged after substantial empirical support and widespread use in fields like marketing, sustainability messaging and political communication (Druckman, 2011; Florence et al., 2022; Kidd et al., 2019).

Although we are not aware of direct evidence on the impacts of frame setting specifically in the field of WTRs, the theory of emphasis framing suggests that it likely affects stakeholders. For instance, news pieces can serve as an important source of inspiration for executives and human resource managers who want to think through whether and how WTRs could work in their organisation. As first-hand experiences of various WTRs (beyond part-time work) are rare, the types of WTRs shown by the media and the credibility of discussions can raise or limit interest among managers. Positive stories can be motivating, because seeing comparable examples and how others could address challenges can make WTRs look realistic and offer useful lessons, while overly positive media reports may be ignored as ‘too good to be true’. Furthermore, if the media framed the opportunity to translate productivity growth into WTR for workers instead of profit for shareholders as a target for the broader labour movement, then it could contribute to a sense of collective possibility and momentum. This is especially relevant in contexts where both wages and working hours have been stagnant for decades despite continuous productivity growth, enriching company owners and reducing the share of income received by workers (Messenger, 2018; Pariboni and Tridico, 2019; Rodriguez and Jayadev, 2013). Besides, individuals reading media accounts may also reflect on their own time use, potentially inspiring some to escape the treadmill of production (Gould et al., 2004), Finally, narratives around well-being, economic impacts, or alignment with progressive labour policies may shape the perceptions of policy makers.

Which effects of emphasis framing dominate depends on the characteristics of the discourse around WTRs, which we study in this paper. Our systematic analysis was motivated by the hypothesis that the media and advocacy discourses focus on specific types of reductions with limited potential for ecological benefits, exaggerating advantages and sidelining challenges compared to the scientific state-of-the-art. This may hinder the implementation of environmentally promising schemes and the wider adoption of WTRs. A discrepancy between the academic and public discourse has recently been suggested on the basis of 31 academic studies, indicating that environmental and productivity benefits are uncertain (Campbell, 2023). While Campbell’s review recognises that popular interest in the topic has been driven by the media and advocacy discourses since around 2019, it does not include a systematic analysis of these discourses.

Nevertheless, we can see why the media representation might be perceived as biased (Campbell, 2023; Spencer, 2022; Veal, 2023b, 2021)—and provide our own examples to illustrate this. One of the most visible advocacy groups, 4 Day Week Global (4DWG), claims contrary to empirical evidence (Golden, 2012; Veal, 2023a) that 4-day workweeks with no workday extension and no work intensification, resulting in no output loss and no pay loss, are possible in any workplace across any industry (4 Day Week Global, 2023). This is called the 100:80:100 model: 100% production, 80% time, 100% pay, which 4DWG co-founder Andrew Barnes (2020) suggests would improve well-being, profitability and sustainability without the trade-offs identified by research (Delaney and Casey, 2021; Hidasi et al., 2023; Kallis et al., 2013; Neubert et al., 2022; Spencer, 2022). Similarly, a report published by the 4 Day Week Campaign (4DWC) of the United Kingdom (UK) claimed that the universal adoption of this model would reduce UK emissions by 127 million tonnes per year. This report gained coverage in several of the largest global media outlets, despite the fact that very little is known about the environmental effects of WTRs, rendering the emission reduction estimate arbitrary and even the direction of change uncertain (Antal et al., 2021). The discrepancy between media and academic discourse is also visible in discussions of environmental strategies at the macro level, sometimes even within the works of the same person. Juliet Schor, the best-known academic in the field who is also a bestselling author and lead researcher for trials conducted by 4DWG, was involved in a widely-publicised research report talking about ‘healthy growth’ of revenues at companies running WTRs (Lewis et al., 2023), while also suggesting that WTRs can be useful to make ‘degrowth work’ as part of an academic team (Hickel et al., 2022). Finally, the 2019 WTR trial by Microsoft Japan gained global attention for reportedly increasing productivity by 40% along with other co-benefits (Toh and Wakatsuki, 2019). One may wonder why it was abandoned then.

To gain a more comprehensive view of the discourse and evaluate its environmental implications, we formulated the following research question: How do characteristics of the current online written news and advocacy discourses on WTRs help or hinder sustainability? This includes attention to the features of WTRs discussed because they matter for impacts of individual schemes and the feasibility of widespread adoption, which together determine overall environmental impacts.

We conducted discourse analyses focusing predominantly on the years after the Covid-19 outbreak when interest in WTR grew substantially (Campbell, 2023). We studied dominant actors, types of WTRs, the tone of discussions and claims regarding feasibility and environmental impacts. The analysis covered 3617 English language news pieces and 156 documents produced by 34 organisations advocating WTR. Our approach was mainly quantitative, but subsamples of the corpus were also coded qualitatively. After outlining the methods (Section ‘Methods’), we present the results of our analysis, explaining what the studied discourses look like (Section ‘Results’). Then we offer a discussion that interprets findings from a sustainability perspective, relying on relevant findings from academic research and on evidence we collated on the topics found to be strongly represented in the studied discourses (Section ‘Discussion’). Finally, we draw conclusions, calling for a re-framing of the issue and mentioning a few potential ways in which that could be done (Section ‘Conclusion’).

Methods

News discourse

Our aim was to identify the dominant framing of WTRs in the news discourse around working time reduction. While definitions of media frames can differ widely across different studies (Guenther et al., 2024), we associated them with specific expressions and combinations of expressions. For instance, a ‘win-win’ frame was associated with words expressing positive emotions and word combinations that referred to benefits for all stakeholders. In contrast, a ‘trade-off’ frame was associated with words expressing mixed emotions and word combinations referring to both pros and cons for stakeholders. We did not empirically study the process of media framing (how the discourse emerged), only its outcome (what it looked like). Nevertheless, we analysed how often specific actors and WTRs were mentioned because some proponents tend to use the ‘win-win’ frame and the 100:80:100 model is more compatible with this frame than other types of WTR. Similar, frequency-based approaches to identify typical media messaging are common (Riffe et al., 2024). Examples include the analysis of the prevalence of different emotions in news media headlines, the occurrence of prejudicial words related to social identities, as well as the frequency of words related to metaphors of the COVID-19 pandemic and the human-nature relationship (Antal and Drews, 2015; Rozado et al., 2023, 2022; Wicke and Bolognesi, 2020). Such computer-assisted studies can cover larger corpora than qualitative methods while also identifying frames more transparently based on the use of specific words (Entman, 1993; Matthes and Kohring, 2008). At the same time, deeper qualitative understanding requires the closer reading of subsamples, which is why we did this for the environmental sub-sample of the corpus.

In the sampling stage, we collected English-language online articles published between June 2020 and June 2023. We used a social listening platform called SentiOne, which allows the mass collection of news pieces and social media posts. This tool has been applied in various areas of communication studies, including the analysis of COVID-19-related online content, coping strategies of parents and teachers during pandemic-related school closures, depression narratives in social media posts and sources of discontent in an urban setting expressed in Facebook posts (Burzyńska et al., 2020; Neag and Healy, 2023; Sik et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2021). We used SentiOne to collect articles from news sources and aggregators with broad audiences like cnbc.com, theguardian.com, cnn.com, reuters.com, yahoo.com and msn.com. Our dataset contained articles from more than 1400 websites (the list is available as an online Supplementary Data file). We used a list of 56 keyword combinations—including many synonyms and variations—to identify a broad set of potentially relevant articles (Supplementary Information). The resulting corpus size was 33310 and included the full text for each article.

Despite the specific keywords, we identified many articles in the corpus that did not refer to our research topic, so we had to filter out irrelevant content. Instead of a simple stop-word approach (filtering out articles that contain specific words or terms), we chose an iterative topic modelling solution. Topic modelling aids in comprehending extensive text corpora by delving into the underlying structure of the corpus (Liu, 2020). The most prevalent technique for topic modelling is Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) (Blei et al., 2003). LDA posits that words carry significant semantic information, and related documents employ similar word sets. The algorithms underpinning LDA operate on a hierarchical Bayesian probabilistic model, where topics and their distributions across documents are latent variables. Each document (article) can be associated with multiple topics and varying probabilities. For the efficient use of this topic modelling approach, we first had to pre-process the text. We removed HTML tags and links, lemmatised the text and collocated the most frequent bi-grams. We first ran a topic model with 15 topics. This high topic number helped us to identify many different themes and topics. We manually reviewed the results of the topic models and identified topics whose content was irrelevant to our research. We omitted those contents and re-ran the topic model with the narrower corpus. We did this in three rounds, resulting in a set of 7251 articles. Subsequently, we identified and removed duplicated articles, creating a dataset with unique articles (always keeping the one published earliest). This final dataset contained 3617 articles.

To identify the actors and locations in the articles, we used a bert-base-NER language model, a fine-tuned Named Entity Recognition model (https://huggingface.co/dslim/bert-base-NER). For each entity, we recorded the number of total occurrences as well as the number of articles in which they appeared. After the computerised name recognition, we manually went through the list of 2396 entities, identified all relevant ones and categorised them. We distinguished persons, organisations/institutions and WTR examples. We also identified terms that referred to the same entity and re-ran the calculations for occurrences.

Concerning the types of WTRs mentioned, we studied how productivity and wages were discussed, because aggregate production and consumption are likely the most impactful mechanisms through which environmental benefits can be achieved (Nässén and Larsson, 2015; Neubert et al., 2022). For this, we applied dependency parsing, which is the process of analysing the grammatical structure of a sentence by determining the relationships between words based on their dependencies or syntactic connections. This method is more suitable than topic modelling when analysing discourse below the level of full documents (Németh and Koltai, 2021; Stuhler, 2022). For dependency parsing we used a Roberta language model on this database for individual sentences (https://huggingface.co/spacy/en_core_web_trf). We selected the words ‘productivity’, ‘salary’, ‘wage’ and ‘pay’ (and their plurals) from the dependency tree and searched for their nominal modifiers (NMOD), such as ‘increase’, ‘boost’, or ‘loss’. The first dependencies contained many variations of the same word co-occurrence. To achieve higher validity, we cleaned and standardised the dependencies (e.g. ‘increased wages’ and ‘increase wage’ were considered equal). To find the negations, we searched for negating terms (such as ‘not’, ‘don’t’, ‘avoid’, ‘without’) in the five-word proximity of our target words. If we found a negating term, we marked the dependency as a negation. Based on a selection of three pairs of terms (i.e. ‘cut’ and ‘pay’; ‘boost’ and ‘productivity’ [negated]; as well as ‘increased’ and ‘productivity’, which included the most common pairs that we did not expect), we manually checked a subsample of 355 sentences to identify instances of incorrect coding as well as the reasons for them. Using an iterative process, corrections were made (e.g. further negating terms were added) until no further options for improvement could be identified. In the final round of checking the accuracy of the dependencies within the subsample, 96.61% were correct. Then we analysed all pairs of terms. As they could appear in many contexts, not just with reference to WTR, we filtered the results to those dependencies where the sentence contained one of the keywords we used for selecting the corpus.

To understand the emotional context around WTR, we used a third language model—DistilRoBERTa-base (https://huggingface.co/j-hartmann/emotion-english-distilroberta-base), which identifies the six basic emotions (joy, sadness, fear, disgust, anger, surprise) on a sentence level. Each sentence receives six emotion values that add up to 1. To increase the likelihood that emotions are strong and refer to WTR, we only considered those sentences which had an emotion score above 0.75 for one feeling and included one of our keywords. We manually checked 477 such sentences, re-categorised them when necessary and removed the ones that did not refer to WTRs or were not emotionally laden. This left 386 sentences with clear emotional content.

For the environmental part of the quantitative analysis, we first identified all articles that included any of our 15 environmental keywords (Supplementary Information). This restricted the sample to 620 articles. We identified the relevant parts of the articles by highlighting the sentences that included the keywords and read the parts before and after them to make sure we understand what the article said about the topic of environmental relevance. When the relevant part of the discussion was not related to WTR, we excluded the article. This left 298 articles. Then we manually coded the actors featured, whether WTR is presented as good for the environment, as well as the causal mechanisms discussed and reference points (e.g. reports) mentioned by the article.

From these methods several limitations follow:

-

We can only talk about the written discourse. Other discourses may be different.

-

We only studied frame setting, not the actual impacts of frames on various stakeholder groups. Consequently, our interpretations of observed behaviours (such as low adoption rates of WTRs) are based on knowledge about expectable impacts of frame setting rather than on explicit measurements of impacts.

-

We only studied the characteristics of the discourse, not the process of media framing (e.g. editorial decisions). As a result, we are unable to determine whether this process involved disputes, resistance, or compromises by different stakeholders and can only make interpretations on the basis of the discursive outcome.

-

Our list of keywords may not be comprehensive, so relevant information on WTRs may have been missed.

-

Our sample is not complete, so it is possible that other parts of the discourse are different. For instance, non-English sources or sources not covered by our research tools may show a different picture, and we do not know the size of the audience that is captured and missed by our method. We do know, however, that the overwhelming majority of news pieces we were previously aware of were included in the analysis.

-

Despite several rounds of filtering, there are irrelevant articles in the final sample, which is unavoidable using computerised methods for thousands of articles. This explains why the proportion of articles mentioning dominant actors and examples is not higher still.

-

Identifying relevant entities (actors and examples) manually means that certain entities of smaller importance may have been missed. We read many articles in full and had several years of experience in the field, so it is unlikely that entities of major importance are missed.

-

The methods applied for dependency parsing and emotion identification are imperfect. We tried to correct for such errors manually, but achieving 100% accuracy is unfeasible.

-

The 5-word distance cutoff used to identify negations is not perfect as negating words may be further away. We suspect that the combination of ‘cut’ and ‘pay’ without a negation would be even less frequent if all such negations were considered. However, using a larger cutoff distance would result in many false negation cases in which the negation refers to something else.

-

Co-occurring expressions may be discussed in a positive or negative way. For instance, a reduction of productivity could be portrayed as a problem. This would further strengthen our point. Negative discussions of pay not being reduced and productivity growth are unlikely.

Advocacy discourse

For the advocacy discourse, we identified PDF files with an advanced Google search using essentially the same list of search terms referring to WTR that we used for the quantitative analysis (Supplementary Information) for the period January 2019 to June 2022. Results had to be English language documents. This produced a collection of 1607 PDF files, which we manually checked to isolate documents from organisations that advocate for WTR. To separate the advocacy discourse from the academic discourse, we excluded scientific studies, conference materials, government information on temporary workshare programmes, neutral commentaries and documents from a political party that had changed its position (i.e. UK Labour). The organisations that published the remaining documents were listed as potential advocates of WTRs.

In the following step we performed another advanced Google search on the websites of the identified organisations, again restricting the search to PDF files and documents containing any of the previous keywords. In one instance, we knew that an organisation (specifically 4DWC) had produced several online publications on WTR, but these were hyperlinked to an external platform, so we downloaded them manually in addition to the search results. After filtering out duplicates and documents published before 2019 or with an inapplicable topic focus (e.g. reduced work hours due to Covid-19), we obtained a selection of 34 organisations and a total of 156 documents, ranging between 1 and 21 per organisation (Supplementary Information, Tables S1 and S2).

We thematically coded these documents. This involved an iterative process of deduction and induction through which we developed a coding framework that distinguishes between benefits, characteristics and approaches to implementation. Finally, we aggregated the codes assigned to the documents for each organisation to create a comprehensive view of their positions.

This approach, inspired by Schlogl et al. (2021), has its own limitations:

-

It is possible that not all positions and views are properly reflected by the documents we found. One reason for this is that some organisations produced few documents, which may offer an incomplete view. Another reason is that some types of documents (such as leaflets) are shorter and less detailed than others (such as reports), so the diversity of documents used—including booklets, policy papers, newsletters, leaflets and manifestos—may have resulted in a somewhat incomplete and imbalanced view of positions. More detailed or varied positions may exist in other formats (e.g. internal policy documents, podcasts, interviews). For example, advocates not specifying their preferred WTR regimes (e.g. quantity and distribution of hours, impact on workloads) or the cause of environmental benefits could still have such preferences or reasons to expect environmental benefits.

-

It is also possible that a few less impactful organisations and their documents have not been found. One indication for this is that the first Google search (to identify organisations) did not return all documents that were found in the second search (when the websites of the specific advocates were searched).

-

In addition, limiting the sample to PDF files to improve the manageability of data collection and analysis may have led to the exclusion of relevant text materials and advocacy organisations.

-

Finally, given the inherently subjective decisions in thematic coding, variations in the interpretation of the results are possible.

Results

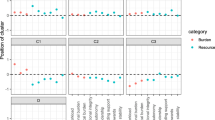

Actors dominating the online news discourse

The current discourse is dominated by members of one global and two UK-based campaigning organisations—namely 4DWG, Autonomy and 4DWC—bestselling author and academic researcher Juliet Schor, who also conducts research for these campaign groups and Mark Takano, a politician who introduced legislation to shorten the standard workweek in California. In fact, no other person made it into the top 10 most frequently mentioned names except two historical figures (Table 1a). The eight dominant contemporary persons appear more often (1603 times) than all the other 38 names that were identified as relevant based on a qualitative understanding of existing research, advocacy, policies and trials (1278 times). Schor’s name is mentioned approximately as often (310 times) as all the other researchers (13 persons) combined (332 times).

The top 10 organisations start with the three advocacy organisations, two universities mentioned in connection with their trials and the institution with which Schor is affiliated (Table 1b). These are followed by an Icelandic organisation (Alda) that conducted substantial WTR trials and published its main report together with Autonomy. Finally, two political parties and the largest European trade union bring some diversity to the top 10. The three advocacy organisations and those institutions that studied their trials or conducted research for their reports (some of which are not in the top 10), plus Schor’s institution are mentioned 1752 times, while the total number of mentions for the other 16 organisations that we identified as relevant is only 545.

Examples of WTRs in the news

We coded the examples according to the locations and companies where WTRs took place (Table 1c). The top 10 were mentioned 4003 times, while the other 23 examples were mentioned 1259 times. The Icelandic trial consisted of two overlapping stages, first in Reykjavík (2014–2019) involving around 2500 workers at its peak, then in the governmental sector (2017–2021) involving a maximum of 440. Working hours were decreased from 40 to 35 or 36 per week. The aim was to maintain per capita production and pay (Haraldsson and Kellam, 2021). The second most frequently mentioned WTR was that of Microsoft Japan, which consisted of five free Fridays in August 2019 for 2300 workers. Pay was not reduced and production was supposedly greater in four days than in five. 100:80:100 schemes were introduced by mid-sized companies (80–800 workers) Unilever New Zealand, Kickstarter, Perpetual Guardian, Atom Bank and Bolt. Belgium made compressed 4-day workweeks possible, without changing weekly working hours. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) introduced 4.5-day, 36.5-h workweeks for public employees without reducing their salaries, except for the city of Sharjah where 4-day, 32-h workweeks were introduced. The WTR scheme of Panasonic was just announced during our sampling period (early 2022) with various options for changing work schedules.

A common characteristic of the frequently discussed WTRs was the aim to increase productivity, thereby maintaining or increasing per capita production, while preserving pay. To confirm that this is indeed the type of WTR that is most frequently discussed, we checked the co-occurrence frequencies of various combinations of keywords (Table 2). While the variations of ‘increase’/‘improve’/‘higher’/etc. and ‘productivity’ occurred 1108 times within a range of 5 words (without negation or a question mark), and the variations of ‘maintain’/‘remain’/etc. and ‘productivity’ occurred 250 times, the variations of ‘loss’ and ‘productivity’ occurred 43 times. If we only considered those sentences which also included any of the keywords used to identify the articles of interest, i.e. almost certainly referred to WTRs, then the same numbers were 372 (for upward change in productivity), 60 (for no change) and 16 (for downward change). Similarly, synonyms of ‘loss’ and ‘pay’ plus a word expressing negation co-occurred 749 times, some versions of ‘increase’ and ‘pay’ 190 times, while words for ‘cut’ and ‘pay’ without a negation within 5 words 152 times. This further confirms that most discussions are about WTRs that aim to increase productivity and maintain wages.

Given the dominance of actors who tend to emphasise the benefits of WTRs and the examples in which employers win through stable or increasing production and employees win by working less for the same money, the tone of the discourse was predictably positive. We tested the frequency with which the six basic emotions (joy, sadness, fear, disgust, anger, surprise) are used in connection to the implementation or desirability of WTRs, finding that 89% of all emotionally charged sentences expressed a positive mood—overwhelmingly in the form of joy, but sometimes through a positive surprise or other emotions. On the negative side, fear is dominant, but it still makes up less than 9% of emotion codes.

Environmental impacts in news discussions

Beyond the general overview of the corpus, we also identified a subset of 298 news pieces that mentioned environmental aspects of WTRs. Among these, the majority (87%) focused primarily on WTR itself, while the rest (13%) discussed a post-growth future or the future of work more broadly, where WTRs were often presented as tools for facilitating sustainable scenarios. Concentrating on the larger group in which direct environmental relevance is discussed, WTRs were portrayed as environmentally beneficial 237 times, likely beneficial with some qualifications 15 times, and questionable or bad in 3 cases. While the quoted researchers were often cautious in their optimism, they did not reflect critically on very confident claims by advocacy groups. Doubts and negative opinions were formulated in the ‘readers write’ section (twice) and as an audience comment to positive opinions of a panel discussion (once).

The causal mechanisms through which WTRs are expected to deliver environmental benefits are very often (52%) unspecified. Instead, there are frequent references to reports produced by campaign groups asserting environmental benefits—especially one commissioned by the 4DWC (Mompelat, 2021) (mentioned 34 times)—and a small number of research papers using statistical methods to compare countries by working hours and environmental indicators, usually co-authored by Schor. When causal pathways are specified, the reduction of commuting (31%), office energy use (9%) and broader lifestyle changes (8%) are mentioned.

Advocacy documents

The messages in the documents published by WTR advocates are similar to those of the news pieces, with somewhat greater diversity and nuance. We categorised the 34 organisations qualitatively based on promoted values and organisation types. This led to a distribution of 14 progressive organisations (including advocacies that engage in consultancy), 11 unions or union affiliates, 4 environmental organisations, 2 firms, 2 government organisations and 1 libertarian think tank (Supplementary Information, Table S1). Overall, there is more emphasis than in the news discourse on implementation strategies that require power struggles, class conflict, or political action, such as collective bargaining (found for 62% of the organisations and 39% of advocacy documents), changes to labour law (including increased worker control over working time) (47% and 12%), and WTR subsidies (29% and 11%). However, recognising that workers do not currently have sufficient bargaining capacity (35% and 22%), WTR advocates often pursue paths of lower resistance. For instance, they frequently emphasise the business case (59% and 67%), portraying productivity growth as a direct outcome of WTR (44% and 26%) or a prerequisite to it (29% and 17%). Calls for hiring additional staff are not common (21% and 6%) and sometimes occur as a last resort initiative, should work intensify too much. In some cases, WTR appears as a tool to manage the adverse employment effects of productivity growth stemming from automation (62% and 35%). Workload reductions are mostly discussed when sectoral labour input is set to fall, e.g. due to automation or regulation (41% and 12%). Advocates also suggest that the public sector could set an example by implementing WTRs (24% and 11%) or emphasise government initiatives to encourage WTRs through accreditation schemes (3% and 0.6%) or public procurement policy favouring reduced hours employers (18% and 6%). The conciliatory nature of this advocacy is also reflected in the environmental case that is made. If specified, the most frequently mentioned source of environmental benefits is lifestyle change that reduces carbon intensity, such as less commuting or consumption of convenience foods (44% and 22%). In addition, WTR is often suggested to facilitate a just transition while downscaling employment in environmentally harmful sectors (41% and 18%). Less consumption due to income loss receives comparatively little attention (15% and 3%).

Discussion

Little reason to expect sustainability benefits from 100:80:100

From a sustainability perspective, the promise of WTRs depends on two factors: participation rates and the environmental impacts of participation. The fact that the 100:80:100 model gets most emphasis and its presentation is overly optimistic in the current news and advocacy discourses is a problem for progress from both perspectives.

Concerning participation, the ‘win-win’ framing suggests that all actors should be keen on voluntarily implementing this type of WTR. This would mean that a great opportunity has only been recognised by a tiny fraction of employers. Without explaining why adoption rates are not higher (the largest national trial involved around 2900 employees (Lewis et al., 2023)), campaign groups claim growing interest in the 4-day workweek. While the diversity of work contexts is sometimes acknowledged, difficulties receive limited attention, despite failures even among companies volunteering to try such WTRs (Telekom, 2024) and the obvious impossibility of using the 100:80:100 concept everywhere. For instance, professional athletes competing with each other surely cannot achieve the same while working 20% less, but manual workers in highly optimised environments and intrinsically motivated artists are also unlikely targets for this model. As a matter of fact, actual working hours did not change during past WTRs in academia, where both competitive institutional pressures and intrinsic interests are strong (Askenazy, 2013). Moreover, the limited measurability of working hours and performance in many contexts can create uncertainty whether goals of the 100:80:100 model are achieved (Lukács and Antal, 2023, 2022; Veal, 2023b). In other words, the current focus on this single type of WTR is not helpful to increase participation.

To make things worse, the media representation of most examples is misleading. In the Icelandic case that is frequently mislabelled as a 4-day workweek (Veal, 2021), it is often reported that 86% of the workforce now either has shorter hours or the right to negotiate reductions. However, it is generally not mentioned that collectively agreed working hours were only reduced by 0–65 min per week (0–3%) after the trial (Haraldsson and Kellam, 2021), before which Icelandic hours were well above the European average (Eurostat, 2024)Footnote 1. Furthermore, it is completely unrecognised in the media that some workers, e.g. in health care, could not sufficiently increase productivity, so new workers were hired at a cost of 0.5% of the total state budget.Footnote 2 Microsoft Japan’s 5-days-off-in-total policy is better described as a very successful public relations stunt than a WTR trial. The successful Unilever New Zealand WTR involved 80 white-collar workers, but it is unclear whether Unilever Australia is equally satisfied with its larger trial (which ended in May 2024, yet no results have been published by January 2025), while global managers of the company seem to be reluctant to test the idea on a workforce well over 100,000. The Belgian 4-day workweek enabled rescheduling, not reducing, working hours. Compression was also the most popular option for the 0.2% of Panasonic workers who chose to change their work schedule (Jucca, 2024; Singh, 2024). Several tech companies among the top 10 examples are still growing or operate in sectors where attracting or retaining workers is difficult, which makes WTR more compatible with profitability than elsewhere (Hidasi et al., 2023). The widely heralded UK trials of 4DWG, 4DWC and Autonomy resulted in an average reduction of just 4 h per week (i.e. not 100:80:100), which is left out from the executive summary of their report (Lewis et al., 2023) and virtually all media discussions. The public sector of the UAE is generally not described as the employer of privileged citizens of the country whose WTR is enabled by oil income and the exploitation of migrant workers (Soojung-Kim Pang, 2021). The latter group, making up 90% of the labour force, is overwhelmingly employed in the private sector where the standard workweek is 48 h (UAE Government, 2024). All these examples suggest that the actual scale of WTR is often smaller than one would think on the basis of the current discourse.

Concerning environmental impacts of participation in WTR, reasons for optimism regarding the 100:80:100 model are very questionable. First of all, this type of WTR does not affect the total volume of consumption and production, ruling out any ‘scale effect’ (i.e. decreasing aggregate consumption or production), which has been identified as the most important mechanism through which environmental impacts could shrink (Nässén and Larsson, 2015; Neubert et al., 2022). In principle, translating productivity gains into more free time for employees instead of more profit for employers could prevent damages from future economic growth, but campaign groups promise productivity gains that would not otherwise happen. This also raises the question whether companies would reduce working hours if they could instead increase productivity and produce more.

Second, while the changing composition of consumption (e.g. less commuting, less office energy use) may reduce impacts, other mechanisms that are rarely mentioned (e.g. more leisure travel, more energy use at home) can increase them. The net impact is uncertain (Antal et al., 2021) and may depend on details of implementation—e.g. whether workdays or workweeks are shortened (King and van den Bergh, 2017). Moreover, speculations on reduced working hours enabling less emission-intensive leisure activities echo the unfulfilled optimism of leisure scholars and futurists in earlier decades that workers would use the extra time for creative activities (Veal, 2023a). Instead, television viewing emerged as the most time-consuming leisure pursuit (Fisher and Robinson, 2010), indicating that major shifts in leisure behaviour are not guaranteed to be ecologically or socially beneficial and require additional policies to facilitate and encourage them (Kallis et al., 2013).

Third, the country comparisons frequently used as reference points are unsuitable for evaluating prospects of current WTRs. They use historical data in which WTRs often meant part-time work with proportional wage reductions, preventing far-reaching conclusions for other types of WTRs. Furthermore, they all suffer from significant methodological problems. For instance, they omit key drivers of environmental indicators, such as changes in the energy mix, attributing their impacts to the independent variables that are included in the statistical models, such as changes in working hours (Antal et al., 2021). The most frequently used report that quantified the impacts of WTR in the UK is a non-peer-reviewed, methodologically flawed study (Mompelat, 2021) (Supplementary Information). The 4DWC was informed about the complexities of quantifying the environmental impacts of WTR but chose to ignore themFootnote 3: they commissioned and published a report with a headline number that supported their narrative; and got media attention globally.

Towards more transformative change

As managers and politicians might fear negative consequences, some advocates may believe that WTRs should be framed as low risk by emphasising benefits and downplaying difficulties. In their view, an overly positive narrative could facilitate the wider adoption of a single type of WTR by raising interest among a core group of business leaders and creating expectations among employees that will compel other employers to adopt shorter workweeks. We argue that this is unlikely. While the 100:80:100 model may play some role in a transition to shorter working hours, it has not spread to most sectors in recent years, raising questions about the credibility of mutual gains. The ‘win-win’ frame is likely unconvincing to large segments of the target audience for being unrealistic or undesirable in their contexts. They may rightly suspect that the various goals often undermine each other, e.g. efforts to increase productivity may jeopardise well-being and environmental benefits (Delaney and Casey, 2021; Neubert et al., 2022). The overoptimistic discourse hides practical challenges and conflicts (Lukács and Antal, 2023; Spencer, 2022), which could prompt the exploration of alternative types of WTRs or different routes towards them.

We suggest that WTRs with trade-offs are likely to be more important in many contexts, as shown by examples that receive limited attention. For instance, companies facing shrinking demand may cut working hours while reducing salaries less than proportionally, as Desigual did in 2021 (Desigual, 2021). Other trade-offs might include slightly longer daily working hours, fewer holidays, or more flexibility from employees in exchange for working one day less, as European examples show (Hidasi et al., 2023; Hoffrogge, 2019). Where such trade-offs cannot be agreed upon amicably, (collective) bargaining is key (Alesina et al., 2006; Hayter et al., 2011; Keune, 2021). Fighting for the right to part-time work or financially compensated reductions without proportionate productivity gains are examples here. A ‘trade-off’ frame of WTRs could concentrate on distributive justice, given that key determinants of working hours include labour power and levels of inequality (since additional hours pay off less in more equal societies) (Huberman and Minns, 2007). Beyond these aspects often neglected by the media, WTRs could also be framed as social and political struggles, given the role of government legislation (Lewis et al., 2008) and cultural norms (Lehndorff, 2014).

In our view, a useful step towards making WTRs more widely available is to identify which types are most feasible in specific contexts. This will depend on practical characteristics, such as workloads and workplace norms, the definition of working hours and measurement tools, as well as the level of trust and the relative bargaining power between employers and employees (Lukács and Antal, 2024). Such insights into the feasibility of WTRs and how working hours are interpreted may also help to achieve collective, (inter-)national reductions, as opposed to company-level schemes.

This brings us to a critical question: How can discourse facilitate larger scale and more transformative change? We argue that various stakeholders could have a role in improving the frame setting process. Advocacy should avoid depoliticising by confronting unavoidable conflicts over difficulties of implementation and misaligned stakeholder interests, instead of pre-emptively settling for less environmentally ambitious mutual gains strategies. Similarly, researchers who often represent prestigious institutions should be cautious about legitimising dominant advocacy groups by working with them (Lewis et al., 2023; Schor et al., 2022) without openly voicing concerns about the overinterpretation of data, misleading claims, or the flawed reports produced by these organisations. More critical scholars should contribute by painting a realistic and scientifically robust picture, but so too should unions from various industries, which have been largely ignored by the media so far. Finally, journalists and politicians who are interested in the topic should be more rigorous, avoid the repetition of misleading claims and look beyond the handful of advocacy voices that dominate the current media discourse. This could also help them to recognise more diverse approaches to promoting WTRs, including not just trials, but also improved time-use rights, legislative changes and social campaigns (Goerlich and Vis, 2024).

Organisations invested in the 100:80:100 model who also generate revenue through consultancy are unlikely to change their communication. While some acknowledge the need to resist a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach, the commitment to maintaining pay and output remains (Backmann et al., 2024; Lewis et al., 2023). As such, we believe that amplifying new voices is essential. This will not be easy because the currently dominant actors have very strong communication networks and media sources often repeat each other. Nevertheless, as scientific knowledge and real-world experiences increasingly undermine their messages, opportunities could emerge for alternative perspectives to gain greater attention. Recent efforts to bring together various research perspectives within the Work Time Reduction Research Network (‘WTR-RN: About us’, 2024) may hold promise by increasing diversity and critical engagement. While the 100:80:100 model still seems to receive most attention even within this network (e.g. Gomes and Fontinha, 2024; Pink et al., 2024), moving beyond it can be a next step for the research community (‘WTR-RN: News and media coverage’, 2024).

From a sustainability perspective, this is desirable because it may facilitate a wider adoption of WTRs, some of which also offer substantially more positive environmental impacts than the model currently dominating communication. For instance, reducing workloads for underpaid workers may have positive (primary) effects by reducing production, while reducing the salaries of high income WTR participants is likely to benefit the environment by reducing consumption. Reducing both at the same time without increasing the working hours of others—e.g. by creating a culture and institutional environment in which skilled workers who are difficult to replace choose shorter hours—is even more likely to improve sustainability. In fact, such WTRs are actual post-growth strategies, whereas preserving (or even increasing) aggregate production and consumption align more with the strategy of ‘green growth’, which is very likely to be insufficient to achieve internationally agreed sustainability targets (Antal and van den Bergh, 2016; Haberl et al., 2020; Hickel and Kallis, 2020; Vadén et al., 2020). These observations call for discussions of WTRs to adopt a broader, more systemic perspective that integrates bargaining power, income inequality, institutional drivers and constraints, as well as attitudes to work and consumption—all differentiated between cultural and work contexts.

Conclusion

Our analysis confirms the hypothesis that media and advocacy discourses on WTRs are dominated by a specific type of reduction whose potential to attract participants and trigger environmental benefits is significantly exaggerated in comparison to the scientific discourse. Crowding out more environmentally promising types of WTRs from media discussions is a risk from a sustainability perspective. Advocacy organisations have a key role in the frame setting process, contributing to a depoliticised and misleading media representation of WTRs.

Other stakeholders could do more to make the picture more realistic. Journalists could pay more attention to not repeat false claims previously made in the media and ideally contact researchers whenever they write about the topic. As a result, they might realise that gradual WTRs triggered by a variety of promotion methods are more significant than the trials that currently receive most attention. Researchers, who are likely to be the main audience of this paper, could make their cooperation dependent on a more balanced and transparent communication by advocacies. For instance, they could refuse collaboration if pilot reports leave key pieces of information out of the executive summaries that are widely used by journalists. More generally, cooperation could also be suspended with groups spreading misleading information, even if that may diminish access to studying trials. Furthermore, researchers could explain under which conditions they would favour WTRs for their potential to spur economic growth as emphasised by advocacies vs. their potential to make degrowth socially acceptable. How each could work in specific contexts is a crucial question not appearing in current media discussions.

We argue that advocates, researchers, journalists and other potential stakeholders should focus more on other types of WTR to contribute to a more credible discourse that addresses practical and political trade-offs when they arise. We also point out that this is especially important from a sustainability perspective because currently neglected types of WTRs can be more environmentally beneficial. Therefore, we suggest a major reframing of WTRs, shifting away from promising automatic success for all through a model that does not suggest significant potential for ecological benefits and toward one that emphasises distributive justice and sustainability through a mix of bargained trade-offs and power struggles.

Data availability

Article texts cannot be shared because of copyrights. All other data are disclosed or can be shared upon reasonable request.

Notes

Lessons from the Icelandic WTR are unclear. Average full-time hours were reduced by 3.8 h between 2019 and 2023, while the average European reduction was only 1 h in the same period, bringing Icelandic full-time hours down to the average European level. The relative importance of the WTR trials and the subsequent collective agreements compared to other factors, especially the Covid-19 pandemic, is unknown. Neither literature searches nor personal communication with an Icelandic researcher involved in the trials could clarify this.

To support this claim, we searched for the name and abbreviation of the Icelandic currency (as given in the widely quoted report by Alda (Haraldsson and Kellam, 2021)): krona and ISK. It was used only once in the whole corpus, without explaining the costs of the WTR programme.

They requested and received guidance from the corresponding author of this paper (who is the main author of a review on the environmental impacts of WTRs (Antal et al., 2021)), which included warnings against quantification in general and the use of cross-country analysis in particular. Their subsequent report did both, committing several other mistakes (Supplementary Information).

References

4 Day Week Global (2023) 4 common myths about the 4 day week, Newsletter (23 Nov 2023) URL https://4dayweekglobal.cmail20.com/t/y-e-xydltid-dyuikrdjkl-m/ Accessed 07 Apr 2025

Alesina A, Glaeser E, Sacerdote B (2006) Work and leisure in the United States and Europe: why so different?, In: Gertler M, Rogoff K (eds) NBER macroeconomics annual 2005. MIT Press

Anderson K, Peters G (2016) The trouble with negative emissions. Science 354:182–183. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah4567

Antal M (2014) Green goals and full employment: are they compatible. Ecol Econ 107:276–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.08.014

Antal M (2018) Post-growth strategies can be more feasible than techno-fixes: focus on working time. Anthr Rev 5:230–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019618794212

Antal M, van den Bergh JCJM (2016) Green growth and climate change: conceptual and empirical considerations. Clim Policy 16:165–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2014.992003

Antal M, Drews S (2015) Nature as relationship partner: an old frame revisited. Environ Educ Res 21:1056–1078. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2014.971715

Antal M, Plank B, Mokos J, Wiedenhofer D (2021) Is working less really good for the environment? A systematic review of the empirical evidence for resource use, greenhouse gas emissions and the ecological footprint. Environ Res Lett 16:013002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abceec

Askenazy P (2013) Working time regulation in France from 1996 to 2012. Camb J Econ 37:323–347. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bes084

Backmann J, Hoch F, Hüby J, Platz M, Sinnemann M (2024) The 4-day-week in Germany: first results of Germany’s trial on work time reduction. Intraprenör, Berlin, Germany

Barnes A (2020) The 4 day week: How the flexible work revolution can increase productivity, profitability and wellbeing, and help create a sustainable future. Piatkus, London, UK

Blei DM, Ng AY, Jordan MI (2003) Latent dirichlet allocation. J Mach Learn Res 3:993–1022

Burzyńska J, Bartosiewicz A, Rękas M (2020) The social life of COVID-19: early insights from social media monitoring data collected in Poland. Health Inform J 26:3056–3065. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458220962652

Cacciatore MA, Scheufele D, Iyengar S (2015) The end of framing as we know it … and the future of media effects. Mass Commun Soc 19:7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2015.10688

Campbell TT (2023) The four-day work week: a chronological, systematic review of the academic literature. Manag Rev Q. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00347-3

Cieplinski A, D’Alessandro S, Guarnieri P (2021) Environmental impacts of productivity-led working time reduction. Ecol Econ 179:106822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106822

Cosme I, Santos R, O’Neill DW (2017) Assessing the degrowth discourse: a review and analysis of academic degrowth policy proposals. J Clean Prod 149:321–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.016

Delaney H, Casey C (2021) The promise of a four-day week? A critical appraisal of a management-led initiative. Empl Relat Int J 44:176–190. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-02-2021-0056

Desigual (2021) Official statement 4-day workday [WWW Document]. URL https://www.desigual.com/en_US/Desigual-statement-4day-working-week.html. Accessed 5 Apr 2024

Druckman JN (2011) What’s It All About? Framing in political science. Perspect Fram 279:282–296

Entman RM (1993) Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun 43:51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Eurostat (2024) Average number of actual weekly hours of work in main job [WWW Document]. Eurostat Data Brows. URL https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/lfsa_ewhan2__custom_10607516/default/table?lang=en. Accessed 28 Mar 2024

Fisher K, Robinson J (2010) Daily routines in 22 countries: diary evidence of average daily time spent in thirty activities (Technical Paper). Centre for Time Use Research, Oxford

Florence ES, Fleischman D, Mulcahy R, Wynder M (2022) Message framing effects on sustainable consumer behaviour: a systematic review and future research directions for social marketing. J Soc Mark 12:623–652. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-09-2021-0221

Goerlich C, Vis B (2024) Different ways of promoting working time reduction: a comparative analysis of actors, motives, forms, and approaches in Germany, Ireland, and Spain. J Comp Policy Anal Res Pract 26:159–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2024.2332437

Golden L (2012) The effects of working time on productivity and firm performance: a research synthesis paper (No. 33), conditions of work and employment series. International Labour Office, Geneva

Gomes P (2021) Friday is the new Saturday: how a four-day week can save capitalism. Flint, Cheltenham, UK

Gomes P, Fontinha R (2024) Four-day week: results from Portuguese trial (final report). Birkbeck/University of Reading

Gould KA, Pellow DN, Schnaiberg A (2004) Interrogating the treadmill of production: everything you wanted to know about the treadmill but were afraid to ask. Organ Environ 17:296–316

Grosse R (2018) The four-day workweek. Routledge, New York, USA

Guenther L, Jörges S, Mahl D, Brüggemann M (2024) Framing as a bridging concept for climate change communication: a systematic review based on 25 years of literature. Commun Res 51:367–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502221137165

Haberl H, Wiedenhofer D, Virág D, Kalt G, Plank B, Brockway P, Fishman T, Hausknost D, Krausmann F, Leon-Gruchalski B, Mayer A, Pichler M, Schaffartzik A, Sousa T, Streeck J, Creutzig F (2020) A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: synthesizing the insights. Environ Res Lett 15:065003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab842a

Haraldsson GD, Kellam J (2021) Going public: Iceland’s journey to a shorter working week. Alda, Association for Democracy and Sustainability & Autonomy

Hayter S, Fashoyin T, Kochan TA (2011) Review essay: collective bargaining for the 21st century. J Ind Relat 53:225–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185610397144

Hickel J, Kallis G (2020) Is green growth possible? N Polit Econ 25:469–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964

Hickel J, Kallis G, Jackson T, O’Neill DW, Schor JB, Steinberger JK, Victor PA, Ürge-Vorsatz D (2022) Degrowth can work—here’s how science can help. Nature 612:400–403. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-04412-x

Hidasi K, Venczel T, Antal M (2023) Working time reduction: employers’ perspectives and eco-social implications—ten cases from Hungary. Eur J Soc Secur 25:426–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/13882627231214547

Hoffrogge R (2019) Voluntarism, corporatism and path dependency: the metalworkers’ unions amalgamated engineering union and IG Metall and their place in the history of British and German industrial relations. Ger Hist 37:327–344. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerhis/ghz037

Huberman M, Minns C (2007) The times they are not changin’: days and hours of work in old and new worlds, 1870–2000. Explor Econ Hist 44:538–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2007.03.002

Iyengar S (1991) Is anyone responsible? How television frames political issues. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Jackson T, Victor P (2011) Productivity and work in the ‘green economy. Environ Innov Soc Transit 1:101–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2011.04.005

Jucca L (2024) Four-day week is clever fix to economic malaise. Reuters

Kallis G, Kalush M, O ’Flynn H, Rossiter J, Ashford N (2013) Friday off”: reducing working hours in Europe. Sustainability 5:1545–1567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5041545

Keune M (2021) Inequality between capital and labour and among wage-earners: the role of collective bargaining and trade unions. Transf Eur Rev Labour Res 27:29–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/10242589211000588

Kidd LR, Garrard GE, Bekessy SA, Mills M, Camilleri AR, Fidler F, Fielding KS, Gordon A, Gregg EA, Kusmanoff AM, Louis W, Moon K, Robinson JA, Selinske MJ, Shanahan D, Adams VM (2019) Messaging matters: a systematic review of the conservation messaging literature. Biol Conserv 236:92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.05.020

King LC, van den Bergh JCJM (2017) Worktime reduction as a solution to climate change: five scenarios compared for the UK. Ecol Econ 132:124–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.10.011

Knight KW, Rosa EA, Schor JB (2013) Could working less reduce pressures on the environment? A cross-national panel analysis of OECD countries, 1970–2007. Glob Environ Chang 23:691–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.02.017

Lee D, Park J, Shin Y (2024) Where are the workers? From great resignation to quiet quitting. Fed Reserve Bank St Louis Rev 106:1–13. https://doi.org/10.20955/r.106.59-71

Lehndorff S (2014) It’s a long way from norms to normality: the 35-hour week in France. ILR Rev 67:838–863. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793914537453

Lewis J, Campbell M, Huerta C (2008) Patterns of paid and unpaid work in Western Europe: gender, commodification, preferences and the implications for policy. J Eur Soc Policy 18:21–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928707084450

Lewis K, Stronge W, Kellam J, Kikuchi L, Schor JB, Fan W, Kelly O, Gu G, Frayne D, Burchell B, Hubbard NB, White J, Kamerāde D, Mullens F (2023) The results are in: the UK’s four-day week pilot. Autonomy, Hampshire, UK

Liu B (2020) Sentiment analysis—mining opinions, sentiments, and emotions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Lukács B, Antal M (2022) The reduction of working time: definitions and measurement methods. Sustain Sci Pract Policy 18:710–730. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2022.2111921

Lukács B, Antal M (2023) The practical feasibility of working time reduction: do we have sufficient data? Ecol Econ 204:107629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107629

Lukács B, Antal M (2024) Six clusters with radically different outlooks for working time reduction: insights from a survey and implications for post-growth thinking. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4693610

Matthes J, Kohring M (2008) The content analysis of media frames: toward improving reliability and validity. J Commun 58:258–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00384.x

Méda D, Vendramin P (2017) Reinventing work in Europe—value, generations and labour. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Messenger J (2018) Working time and the future of work (Research Paper No. 6), research paper series. International Labour Organization, Geneva

Mompelat L (2021) Stop the clock—the environmental benefits of a shorter working week (Report by Platform London). 4 Day Week Campaign, London, UK

Nässén J, Larsson J (2015) Would shorter working time reduce greenhouse gas emissions? An analysis of time use and consumption in Swedish households. Environ Plan C Gov Policy 33:726–745. https://doi.org/10.1068/c12239

Neag A, Healy S (2023) Daddy should search for help on Google instead of swearing … ’: escaping the boundaries of technologically mediated learning. Learn Media Technol 48:649–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2023.2249812

Németh R, Koltai J (2021) The potential of automated text analytics in social knowledge building. In: Rudas T, Péli G (eds) Pathways between social science and computational social science: theories, methods, and interpretations. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54936-7_3

Neubert S, Bader C, Hanbury H, Moser S (2022) Free days for future? Longitudinal effects of working time reductions on individual well-being and environmental behaviour. J Environ Psychol 82:101849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101849

Neuman RW, Just MR, Crigler AN (1992) Common knowledge: news and the construction of political meaning. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Pariboni R, Tridico P (2019) Labour share decline, financialisation and structural change. Camb J Econ 43:1073–1102. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bez025

Pink J, Kamerade, Burchell, B (2024) Four-day week trial: South Cambridgeshire council’s key performance indicator evaluation (Research Report). University of Salford/University of Cambridge, URL https://www.scambs.gov.uk/media/hdepajv2/report-rec-200524.pdf Accessed 7 April 2025

Riffe D, Lacy S, Watson BR, Lovejoy J (2024) Analyzing media messages: using quantitative content analysis in research, 5th edn. ed. Routledge, New York London

Rodriguez F, Jayadev A (2013) The declining labor share of income. J Glob Dev 3:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1515/jgd-2012-0028

Rozado D, Al-Gharbi M, Halberstadt J (2023) Prevalence of prejudice-denoting words in news media discourse: a chronological analysis. Soc Sci Comput Rev 41:99–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393211031452

Rozado D, Hughes R, Halberstadt J (2022) Longitudinal analysis of sentiment and emotion in news media headlines using automated labelling with Transformer language models. PloS ONE 17:e0276367. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276367

Scheufele D (1999) Framing as a theory of media effects. J Commun 49:103–122

Schlogl L, Weiss E, Prainsack B (2021) Constructing the ‘Future of Work’: an analysis of the policy discourse. New Technol Work Employ 36:307–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12202

Schor JB (2010) Plenitude: the new economics of true wealth. Penguin Press

Schor JB, Fan W, Kelly O, Gu G, Bezdenezhnykh T, Bridson-Hubbard N (2022) The four day week—assessing global trials of reduced work time with no reduction in pay. Four Day Week Global, Auckland, NZ

Sik D, Németh R, Katona E (2023) Topic modelling online depression forums: beyond narratives of self-objectification and self-blaming. J Ment Health 32:386–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1979493

Singh N (2024) Japan pushes four-day workweek amid labour shortage, faces cultural hurdles. Business Standard

Smith MK, Sziva IP, Olt G (2021) Overtourism and resident resistance in Budapest. In: Travel and tourism in the age of overtourism. Routledge

Soojung-Kim Pang A (2021) UAE joins the global movement for a shorter workweek. Gulf News 13 Dec 2021, URL https://gulfnews.com/opinion/op-eds/uae-joins-the-global-movement-for-a-shorter-workweek-1.84346589 Accessed 7 April 2025

Spencer DA (2022) A four-day working week: its role in a politics of work. Polit Q 93:401–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.13173

Stuhler O (2022) Who does what to whom? Making text parsers work for sociological inquiry. Sociol Methods Res 51:1580–1633. https://doi.org/10.1177/00491241221099551

Telekom (2024) Press release [WWW Document]. URL https://www.telekom.hu/about_us/press_room/press_releases/2024/february_13

Toh M, Wakatsuki Y (2019) Microsoft tried a 4-day workweek in Japan. Productivity jumped 40% | CNN Business [WWW Document]. CNN. URL https://www.cnn.com/2019/11/04/tech/microsoft-japan-workweek-productivity/index.html. Accessed 31 Jul 2024

UAE Government (2024) Working hours and overtime [WWW Document]. URL https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/jobs/employment-in-the-private-sector/working-hours. Accessed 27 Mar 2024

Vadén T, Lähde V, Majava A, Järvensivu P, Toivanen T, Hakala E, Eronen JT (2020) Decoupling for ecological sustainability: a categorisation and review of research literature. Environ Sci Policy 112:236–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.016

Veal A (2021) The success of Iceland’s ‘four-day week’ trial has been greatly overstated [WWW Document]. The Conversation. URL http://theconversation.com/the-success-of-icelands-four-day-week-trial-has-been-greatly-overstated-164083. Accessed 27 Mar 2024

Veal A (2023a) The 4-day work-week: the new leisure society? Leis Stud 42:172–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2022.2094997

Veal A (2023b) 4-day work week trials have been labelled a ‘resounding success’. But 4 big questions need answers [WWW Document]. The Conversation. URL http://theconversation.com/4-day-work-week-trials-have-been-labelled-a-resounding-success-but-4-big-questions-need-answers-201476. Accessed 27 Mar 2024

Wicke P, Bolognesi MM (2020) Framing COVID-19: how we conceptualize and discuss the pandemic on Twitter. PLoS ONE 15:e0240010. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240010

WTR-RN: About us (2024) WTR-RN. URL https://www.wtr-rn.com/about-us. Accessed 13 Jan 2025

WTR-RN: News and media coverage (2024) WTR-RN. URL https://www.wtr-rn.com/news-and-media-coverage. Accessed 13 Jan 2025

Acknowledgements

The MTA-ELTE Lendület New Vision Research Group is funded by the Lendület grant (95245) of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The research was supported by the European Union within the framework of the RRF-2.3.1-21-022-00004 Artificial Intelligence National Laboratory Program. The work of ZK was supported by the Bolyai Scholarship, grant number: BO/834/22. We thank Bence Lukács, András Takács-Sánta and Lili Krámer for comments.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Eötvös Loránd University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Benedikt Lehmann participated in research design, collected data for the qualitative analysis and participated in data analysis and paper writing. Zoltán Kmetty participated in research design, performed quantitative data collection and described the quantitative methods. Miklós Antal obtained funding, participated in research design and data analysis, and led paper writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Consent was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lehmann, B., Kmetty, Z. & Antal, M. Too good to be true: the English-language discourse of working time reductions and its implications for environmental sustainability. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 511 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04569-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04569-6