Abstract

Firms are increasingly shifting towards digital channels, yet the implications of this shift remain underexplored. Using a unique database of customer behaviors extracted from the top 2000 mobile apps developed by companies in China, this study investigates the impact of mobile apps on inefficient corporate investments. The results indicate that metrics such as active user count, usage duration, and app launch frequency can mitigate inefficient investments, notably by curtailing overinvestment. These findings survive a series of robustness checks such as altering the measures of inefficient investment, extending the analysis to include the top five apps, incorporating H-share listed firms, and employing instrumental variables regression. Moreover, the mechanism analysis indicates that mobile apps help reduce inefficient investments by lowering agency costs and relaxing financial constraints. Further analysis examines the business models of these apps (paid vs. free) as well as their reputation mechanisms, revealing that the pricing strategies of apps and the reputation of corporate brands also play a role in how the adoption of mobile apps affects inefficient investment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The advent of digital technology applications, particularly artificial intelligence, blockchain, and cloud computing, represents a transformative shift (Sun et al., 2023; Cao et al., 2023). Digital technologies promote the upgrading and improvement of traditional product systems, production processes, organizational structures, and business models, which provide the impetus for the overall change of corporates (Bharadwaj et al., 2013). Recent studies have used textual analysis to explore corporate digital transformation (Yermack, 2017; Chen and Srinivasan, 2024). However, as digital transformation is still in its initial stage, many corporates release digital information to gain capital market recognition and policy support, often for promotional purposes. This makes it difficult for text analysis to accurately reflect the actual application of digital technology. Given that, this paper defines the application of digital technology as the process of adopting digital technology to develop new products, improve the production process, change the organizational model, and innovate the business model.

Mobile application programs (Apps) are the key digital product, integrating digital information technology with traditional industry. They enable corporates to showcase products innovatively and establish self-sales channels, driving unprecedented informatization, flattening, and globalization in production, sales, and consumption. In recent years, non-contact services have surged, increasing reliance on apps for online office work, learning, socializing, and entertainment. According to China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the total number of apps dropped by 36% from 2017 to 2022 due to stricter Internet regulation, as shown in Fig. 1. By the end of 2022, the number of apps in China was 2.58 million, with 1.28 million on Android store and 1.3 million on Apple store. Meanwhile, according to the “Statistical Report on the Development Status of China’s Internet” published by the China Internet Network Information Center, China’s mobile Internet users steadily grow to 1.065 billion by 2022, accounting for 99.8% of all Internet users, as shown in Fig. 2. This expanding user base, alongside declining apps under stricter regulation, signals a maturing application market in China.

The application of digital technology represented by apps is transmissive and fluid, providing rich data and growth opportunities for banking, finance, and tech sectors (Panetta et al., 2023). Specifically, born from IT advancements, apps reshape the supply and demand structure of the industrial system. On the supply side, modular component technologies reduce technical monopolies and lower usage barriers through remote data and computing power support, supporting corporate operations. On the demand side, Apps digital technology application expands cyberspace functionality, enabling users to participate in product innovation and express their own unique needs. In particular, metrics like the number of active users and launches and the length of use can reflect the product's popularity, while ratings and comments produced by users online instantly reveal users' sentiments, guiding quality improvements and investment decisions. For example, e-commerce apps—such as Amazon, SHEIN, Taobao, Jingdong—facilitate sales, while social platforms—such as Facebook, Twitter, WeChat, Tik Tok, and REDnote—enhance product visibility and user feedback.

Traditional financial accounting reports tend to lag in reflecting business operations, hindering timely insights. Apps, however, accumulate user data such as user characteristics, behavior, and location, and enable real-time sharing of operational and financial information, reducing information asymmetry and mitigating agency problems (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Yermack, 2017). By providing shareholders direct access to company data, apps enhance oversight, align interests, and promote better decision-making (Avinadav and Bunker, 2022). Furthermore, apps facilitate shareholder feedback and participation in decision-making, bridging the gap between management and shareholders and fostering a more collaborative environment for investment decisions (Modgil et al., 2021). Based on the preceding analysis, this paper explores how mobile apps generated by corporates impact investment decisions. In particular, apps enhance monitoring of internal management to curb opportunism, mitigating the agency issue, while transparent user data boosts external investors’ trust, easing financing restrictions and impacting corporate investment decisions.

Using a unique database on customer behaviors extracted from the top 2000 mobile apps developed by companies in China, this paper aims to empirically investigate whether the application of digital technology indeed influences enterprise inefficient investment. We collect data on the number of active users, duration of use, and starts of mobile apps ranked within the top 2000 mobile apps from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2019. Mobile apps offer real-time data, dynamically reflecting corporate information. For instance, WeChat, the most popular mobile app in our sample, had more than 950 million active users in April 2019, accounting for 94.39% of the total number of active users on the network, and the number of starts and duration of use also exceeded 35.94 million and 2.71 million hours, respectively, for the month. The detailed dataset on mobile app user behaviors provides rich information for corporate investment decision-making.

Theoretically, we demonstrate that the data on customer behaviors in this paper has dual significance in enterprise decision-making and external investor assessment. First, these data provide a direct reflection of customer loyalty and persistence across regions and, over time, guide strategic planning. Second, the data from mobile apps complement traditional accounting information by indirectly communicating to investors to signal untapped growth potential and is currently undervalued. Empirically, we measure the application of digital technology within enterprises via the data on customer behaviors derived from mobile apps, which is a different approach from the textual analysis used to acquire enterprise digitalization in previous studies (Wang et al., 2024; Chen and Jiang, 2024), and better captures the importance and utilization of digitalization within the enterprise.

This paper focuses on apps developed by listed companies to examine their impact on corporate investment efficiency. We find that metrics such as active user count, usage duration, and app launch frequency, derived from mobile apps, are effective in correcting inefficient investments, especially in reducing overinvestment. Subsequently, we conduct a series of robustness checks to support the findings. Furthermore, our mechanism tests suggest that mobile apps correct inefficient investment by alleviating agency problems and financing constraints. We also performed heterogeneity tests and found that mobile apps influenced enterprises’ inefficient investment by the equity incentives and financing structure. Specifically, enterprises that have not implemented equity incentives and those with excessively high-debt financing experience greater correcting effects from mobile apps. Finally, we consider the business models of these apps (paid vs. free) as well as their reputation mechanisms and find that app pricing patterns and corporate brand reputation also influence the relationship between digital technology adoption and inefficient investment.

Our paper contributes to the literature in three ways. First, while existing literature measures enterprise digitalization via surveys or textual analysis (Eller et al., 2020; Mikalef et al., 2020; Ma and Zhu, 2022), we adopt mobile apps as the focal point of digital technology application, allowing for a direct examination of the relationship between digitalization and investment decisions. Based on a unique database of customer behaviors from mobile apps, our study not only assesses the importance of digitalization but also captures its tangible outcomes, providing a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between mobile apps and investment decisions.

We also contribute to the literature on the economic implications of enterprise digital technology applications. Previous literature confirms the positive effects of digital technology applications on enterprise performance (Usai et al., 2021; Wen et al., 2022; Zhai et al., 2022), including enterprise innovation, sustainability, and economic growth. Our study delves into whether mobile apps improve enterprises’ inefficient investment, providing a new perspective on how digitization affects the real economy. Our investigation also reveals that mobile apps influence investment decisions by mitigating agency problems and alleviating financing constraints, which may guide policymakers in promoting the digital economy and fostering high-quality growth.

Additionally, in the context of China’s economic transition from high-speed growth to high-quality growth, we underscore the significance of enhancing resource utilization efficiency and bolstering investment effectiveness. We examine the role of mobile apps in rectifying inefficient investment and enhancing investment efficiency at the enterprise level, offering practical recommendations for promoting high-quality economic development in China. Overall, our findings contribute to the advancement of knowledge on the intersection of digital technology and economic decision-making, thereby offering valuable insights for both research and policy formulation.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Literature review” presents the literature review. Section “Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses” outlines the research hypotheses. Section “Data, variables and models” introduces the data, variables, and research design. Section “Empirical results” details the empirical processes. Section “Mechanism analysis” conducts the mechanism test, while Section “Heterogeneity analysis” delves into the heterogeneity analysis. Section “Further analysis” provides further extended analysis. Finally, the section “Conclusions” concludes and provides recommendations.

Literature review

Investment decision-making, as the core of corporate financial decision-making, has been an important issue of academic concern. Existing research on the factors influencing corporate investment decisions can be broadly categorized into internal and external perspectives. The internal perspective focuses on the important influential role of a corporate’s shareholders or managers in investment decisions, especially managerial background characteristics (Ullah et al., 2021; Huang and Qiu, 2023; Sumiyana et al., 2023), compensation incentives and equity incentives (Eichfelder et al., 2023), information disclosure (Yan et al., 2024; Zhang and Wang, 2024), equity structure (Jiang et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021), and board governance (Bzeouich et al., 2019; Rajkovic, 2020). The external perspective, on the other hand, emphasizes the significant impact of the environment, including the legal environment (Zhang et al., 2023), accounting standards (Chen et al., 2023), and industrial policies (Zhou and Zhao, 2022), and the role of external monitoring, such as auditors (Bae et al., 2017; Hazaea et al., 2024; Hung et al., 2024) and the media (Yang et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2021) in shaping corporate investment decisions. The constraints imposed by many of the above factors prevent corporates from making decisions based solely on net present value, leading to deviations from the goal of value maximization and inefficient investment.

These studies highlight that corporate investment efficiency is affected by the agency problem between shareholders and management, and information asymmetry between corporates and stakeholders. From the principal-agent theory, there is a general agency problem due to the incomplete contract and divergent goals between shareholders and management, leading to irrational investment behavior such as managerial self-interest behaviors that harm shareholder value (Jiang et al., 2020; Fich et al., 2023). Simultaneously, according to the information asymmetry theory, the high external financing cost brought by information asymmetry will make corporates face financing constraints (Meng et al., 2020; Nikolov et al., 2021). This may force corporates to abandon some projects with positive net present value due to insufficient internal funds, resulting in underinvestment (He and Kondor, 2016; Xu et al., 2023). Together, agency problems can lead to overinvestment, while external financing constraints due to information asymmetry may cause underinvestment, thus leading to inefficient investment (Jensen and Meckling, 1976).

The application of digital technology enables corporates to capture and process data into useful information, which is an effective path to alleviate agency problems and financing constraints, correcting inefficient investments such as overinvestment and underinvestment (Xue et al., 2024). Existing studies found that digital technology applications have become a key competitive resource for corporates in the era of the digital economy, driving value creation (Tambe, 2014; Perrons and Jensen, 2015; Liu et al., 2024). However, the ability of corporate digital technology applications to provide decision-making usefulness remains underexplored. Although some studies explored the relationship between data and investment behavior, focusing on the vast amount of information generated by the Internet and social media (Birch et al., 2021), internal corporate digital applications have not been thoroughly investigated.

Existing literature lacks direct measures of digital technology application. Yu et al. (2024) used keyword frequency in the annual reports to gauge firm digital transformation, finding it boosts innovation investment. However, the keyword frequency can only reflect the corporates’ attention to digital transformation rather than actual application. Other studies divided digital technology into foundation and application levels and synthesized digital technology indicators with the entropy value method (Zhao et al., 2022), which overlooked the interactions between different indicators. In addition, some scholars used corporate information technology systems as indicators of digital technology applications (Hanelt et al., 2021), but this fails to reflect the specific usage pattern of digital technology applications. There is also a small body of literature that examines user-level data, incorporating indicators such as the growth rate of active users, the number of registered users, the size of the customer network, and the click-through rate of Internet businesses into valuation models (Yang and Zhai, 2022; Sakas et al., 2023), which is the unification of digital technology foundation and application.

Based on the above existing studies, this paper centers its investigation on mobile apps as a manifestation of digital technology application within corporates. It undertakes a quantitative analysis of digital technology applications among firms, aiming to deepen our understanding of the relationship between digital technology applications and inefficient investment. Furthermore, the paper seeks to elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving this relationship, drawing upon the principles of principal-agent theory and information asymmetry theory.

Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses

Theoretical framework construction

Theoretical analysis of the impact of apps on corporate investment efficiency

Under the neoclassical economics framework, any project with a positive net present value will be invested in a perfect market, eliminating inefficient investment (Modigliani and Miller, 1958). However, in real-world imperfect markets, investment activities are often influenced by internal factors such as management and governance, and external factors such as the economic environment and monitoring, which may lead to inefficient investment (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Farooq et al., 2021). With the rise of the digital economy, digital technologies can effectively improve corporate governance, gradually influencing investment decisions (Wang et al., 2024). As far as mobile apps are concerned, they offer information on user scale, data collection, and capital acquisition. Their core technologies enable real-time internal and external information capture. Mobile apps provide user-level information through interactive operation interfaces and capital crowdfunding mechanisms through user subsidies and traffic conduction, influencing corporate investment decisions. Also, apps can transmit valuable information to external stakeholders, such as app evaluation, download times, and the specific design, which can reflect user behavior and corporate operations. These capabilities improve investment decision-making at internal and external levels.

Firstly, from the internal perspective, apps enable corporates to capture essential data for daily operations, management, and investment decisions, aligning with resource-based theory. In addition, according to cognitive load theory, the digital technology contained in apps can help corporates manage the cognitive overload problem caused by information complexity, limited cognitive ability, and system tasks. By leveraging technologies like big data and cloud computing, apps enable management to extract accurate information and identify investment projects, which can reduce subjectivity in decision-making, improve cash flow and risk prediction, and enhance investment efficiency. Specifically, apps can increase operational transparency, offering management more data for precise decision-making and reducing inefficient investment brought by subjective judgment (Aben et al., 2021). It also provides shareholders with more data support, helping them monitor managements’ investment decisions and assess their accuracy (Clor-Proell et al., 2020). It can be seen that the applications of digital technology reduce information asymmetry and agency problems, which is conducive to both the management making scientific investment decisions and the shareholders strengthening the supervision of management.

Secondly, from the external perspective, apps can not only help corporates obtain and process data into effective information but also enrich external stakeholders’ access to data and resources, reducing information asymmetry between corporates and stakeholders (Bergh et al., 2019). Stakeholders can access additional information from the interfaces of apps beyond traditional financial accounting reports so that they can better predict and oversee corporate operations. Additionally, information generated by apps can also improve auditing quality and efficiency, strengthening external supervision. This can not only force corporates to optimize management but also help external stakeholders better track corporate operations, provide funding for corporate investments, and reduce inefficient investment behaviors.

In short, with the collected data and processed information from apps, corporate internal governance and external supervision will be improved, leading to more accurate and efficient investments. It is worth noting that inefficient investment takes the form of overinvestment, caused by managerial self-interest due to principal-agent issues, and underinvestment, resulting from financing constraints due to information asymmetry. However, apps can strengthen corporate governance and supervision, curbing managerial self-interest and overinvestment brought by the blind pursuit of investment scale. It can also reduce information asymmetry, alleviating corporate financing constraints and reducing underinvestment. Based on existing literature and the above analysis, this paper explores how mobile apps enhance corporate investment efficiency from the perspective of principal-agent problem and information asymmetry, proposing hypothesis H:

H: The mobile apps developed by companies can effectively correct the inefficient investment of corporates, inhibiting over-investment and alleviating under-investment.

Framework construction of the impact of apps on corporate investment efficiency

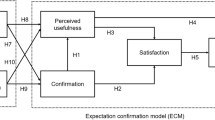

From the above theoretical analysis, based on resource-based theory, apps provide corporates with unique internal and external resources so that corporates can transform them into competitive advantages and references for investment decisions. Based on cognitive load theory, apps help management mitigate irrational investment decisions caused by information overload. In addition, corporate inefficient investment is divided into overinvestment and underinvestment, which are caused by principal-agent problems and financing constraints due to information asymmetry. However, the information generated by mobile apps can improve internal and external supervision, thereby addressing agency problems and financing constraints, and enhancing investment efficiency. To explore these mechanisms, this paper examines the roles of agency problems and financing constraints between mobile apps and corporate investment efficiency, grounded in principal-agent theory and information asymmetry theory. A theoretical framework is constructed accordingly, as shown in Fig 3.

Theoretical analysis of mechanisms

Apps, agency problems, and corporate investment efficiency

The principal-agent problem is one of the causes of corporate inefficient investment. This paper first explores how the information from apps enhances corporate investment efficiency by mitigating agency problems. First, apps help management to identify projects and break data isolation between corporate production and operation, thereby lowering private costs and alleviating agency problems. Specifically, they provide crucial data for internal management to track production and operations, predict the cash flow and risks of investment projects, minimize uncertain risks in investment decisions and the effort required to gather information. In this way, the private cost of information collection for management’s investment decision can be reduced (Bertrand and Mullainathan, 2003; Aggarwal and Samwick, 2006), thereby mitigating management’s ‘lazy’ behavior—such as abandoning projects with positive net present value (NPV) due to high private cost—and correcting the inefficient investment (Bebchuk et al., 2017).

Second, information from apps can facilitate objective evaluation and effective supervision of management’s investment behavior, alleviating the agency problem caused by management’s self-interest. Specifically, objective data, such as regional user numbers and activity levels generated by apps, often form part of the corporate’s internal information. While management controls this internal data, the board of directors and the supervisory board can access it to supervise corporate’s operations and management, ensuring investment decisions are data-driven rather than subjective (Xin and Niu, 2023). Therefore, the strengthening of internal supervision can curb management’s pursuit of private benefits. When there are fewer private benefits for management in investment projects, management will largely refrain from investing in projects with negative NPV, thereby reducing the inefficient investment.

In summary, APP digital technology applications can enhance investment efficiency by addressing agency problems in two ways. First, it lowers the cost and effort for management to access decision-making information, reducing inefficiencies caused by private costs. Second, it strengthens internal supervision, curbing the self-interested behavior and fund misuse caused by managements’ pursuit for private gain, and further correcting the corporate’s inefficient investment. Based on this, this paper proposes hypothesis H1:

H1: APP digital technology applications can improve the efficiency of business investment by reducing agency problems.

APP, financing constraints, and corporate investment efficiency

Information asymmetry is another important cause of corporate inefficient investment. This paper explores how information from apps enhances corporate investment efficiency by reducing information asymmetry. First, apps enable corporates to acquire deeper and broader information, including consumer behavior data from app users, which can be processed and analyzed to generate valuable insights for financing decisions, thereby reducing corporate financing costs (Benlemlih and Bitar, 2018). This information is also accessible to external investors through the app interface, improving information transparency and reducing information gaps. By enhancing access to and dissemination of information, APP digital technology applications strengthen corporates’ bargaining power in financing, lowering financing costs and improving investment efficiency.

Second, new information generated by APP digital technology applications can attract more investors, broadening financing channels. By enhancing communication channels between investors and corporates, it provides investors with information about corporates. This may attract more investors to focus on corporates, broadening the financing channels of corporates. APP digital technology application also enables traceable corporate information and refined financial management. This information, as a supplement of traditional accounting information, improves the quality of accounting information and signals the development potential, further attracting investment (Guariglia and Yang, 2016). Corporates can also leverage user-level data for crowdfunding funds through user subsidies and traffic conduction. Finally, aligning with national digital strategic policy, corporates with apps may be more likely to receive policy support and government funding.

In the end, reduced financing costs and expanded financing channels increase available funds, preventing corporates from abandoning high-quality projects due to financial constraints, and thereby improving investment efficiency (Li, 2011). To sum up, APP digital technology applications reduce information asymmetry, alleviate financing constraints, and enhance investment efficiency by lowering financing costs and broadening financing channels. Based on this, this paper proposes hypothesis H2:

H2: APP digital technology applications can enhance the efficiency of corporate investment by alleviating financing constraints.

Data, variables, and models

Data

The data used in this paper comes from two sources. The first data source is the mobile app data from Analysts. Specifically, it is obtained from Qianfan Analysts (https://www.analysys.cn/), a digital economy insight platform under Analysts. This platform covers 45 fields, over 300 industries, and more than 50,000 apps and serves hundreds of millions of digital users and over 1000 enterprises in China. In this paper, we select the user active behavior data corresponding to the top 2000 mobile apps in the comprehensive ranking of the mobile application market. This data on user active behavior includes metrics such as the number of active users, user usage time (in hours), and the number of app launches. The collection period for this data spans from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2019, with the data being compiled on a monthly basis. These data dimensions represent the cumulative figures for active users, user hours, and app launches each month. Another data source used in this study is the financial data of listed companies associated with the selected apps. From the top 2000 apps selected for this study, we manually compiled the names of the corresponding companies. We then identified and selected 31 A-share and 19 H-share listed companies based on these apps, totaling 50 companies. Based on this, we gathered the quarterly financial information of these targeted listed companies for the period spanning from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2021.

The number of active users in the whole network and in the top three apps of some companies at the beginning of 2014–2019 are shown in Figs. 4, 5.

Definition of main variables and descriptive statistics of variables

Dependent variables

Mobile apps. We assess mobile apps based on three dimensions: the number of active users, the duration of use, and the number of starts for these mobile applications. Given that the shortest reporting period for the periodic financial reports of listed companies is quarterly, we have converted the monthly app data into quarterly data in this study to align it with corporate financial data. Furthermore, to address the issue of heteroskedasticity, this study calculates the ratio of the number of active users, duration of use, and the number of app starts to the total assets, respectively. For a detailed explanation, refer to models (1) through (3). Among them, the Pi,t is the top three mobile apps of i company ratio of the number of active users to the total assets in t quarter, and Ti,t is the top three mobile apps of i company ratio of duration of use to the total assets in t quarter, Ni,t is the top three mobile apps of i company ratio of the number of starts to the total assets in t quarter. Meanwhile, we also calculate the top five ranked mobile apps for the corresponding metrics in i company in the robustness test.

Independent variables

Enterprise inefficient investment. Regarding the measurement of enterprise inefficient investment, this paper draws on Richardson’s model, which is currently recognized and adopted by more scholars (Richardson, 2006). The details are as follows:

In model (4), Invi,t denotes the level of capital expenditures of i company in t quarter (calculated by dividing the ratio of the total cash paid by the firm for the purchase and construction of intangible, fixed, and other long-term assets by the book value of total assets), and accordingly, the Invi,t-1 denotes the level of capital expenditures of i company in t-1 quarter; TobinQi,t-1 denotes growth opportunities of i company in t-1 quarter; Levi,t-1 denotes asset-liability ratio of i company in t-1 quarter; Cashi,t-1 denotes balance of cash and cash equivalents held at the end of the period as a percentage of total assets of i company in t-1 quarter; Agei,t-1 denotes time of listing of i company in t-1 quarter; Sizei,t-1 denotes size of assets of i company in t-1 quarter, which analyzed as the logarithm of total assets. Reti,t-1 denotes annual return on its stock of i company in t-1 quarter; Ind and Time are industry control variables and time control variables, respectively. This paper uses the absolute value of the regression residuals in model (4) to measure the firm’s inefficient investment (Inefficient), the larger the absolute value of the residuals, the higher the degree of inefficient investment. A positive residual belongs to overinvestment (Over_I) and a negative residual belongs to underinvestment (Under_I).

Control variables

To overcome the problem of omitted variables, this paper draws on existing relevant studies, such as Love and Martínez Pería (2015), and adds control variables at the levels of corporate financial characteristics and corporate governance, including Enterprise size (Size), Asset-liability ratio (Leverage), current ratio (Liquidity), Cash holdings (Cash), TobinQ (TobinQ), management costs (Admin) and merging of two posts (Duality). The effects of quarter×year (Time) and industry (Ind) on corporate inefficient investments are also controlled. All continuous variables are subjected to a 1% reduction in the top and bottom.

Table 1 summarizes the statistical characteristics of the variables. As can be seen from Table 1, the mean value of the corporate inefficient investment is 0.0262, which is similar to the results of existing studies (Feng and Wen, 2022). The observed values of overinvestment and underinvestment samples are 238 and 307, respectively, which means that 44% of listed companies in the sample have overinvestment and 56% of listed companies have underinvestment, which shows that the phenomenon of underinvestment in the sample enterprises is more common. The mean values of overinvestment and underinvestment are 0.0282 and 0.0250, respectively, which means that overinvestment of the sample enterprises is more serious. The values of the control variables are all within a reasonable range.

To rigorously investigate the potential presence of multicollinearity among the variables, this paper verifies the correlation between the main variables by using the Pearson and Spearman methods, as presented in Table 2. Spearman correlation coefficients are above the main diagonal, and Pearson correlation coefficients are below.

Model design

In order to estimate the correcting effects of mobile apps on corporate inefficient investment, this paper constructs the following regression model:

In the model, Inefficientit denotes inefficient investment of i company in t quarter, Over I and Under Idenotes overinvestment and underinvestment, respectively. Appit denotes mobile apps of i company in t quarter, measuring with the number of active users (Pi,t), duration of use (Ti,t) and the number of starts (Ni,t). Zit denotes control variables of i company in t quarter. To prevent biased estimates due to the omission of non-time-varying factors such as industry, as well as time-trend terms, the model simultaneously controls for industry-level individual effects that do not vary over time (ΣβiLnd) with time effects that do not vary with individuals(ΣβiTime). εi,t is the random perturbation term in this paper, and to mitigate the problem of heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation, firm-level clustering robust standard errors are used in this paper.

Empirical results

Basic results

To verify the impact of mobile apps on corporate investment efficiency, we employ model (5) with control variables, time, and industry-fixed effects. The results are shown in Table 3. Panel A presents firm-level results derived from aggregating the number of active users, duration of use, and number of starts for the top three apps for the sample firm. We then utilize the cumulative number of active users (PT), the cumulative duration of use (TT), and the cumulative number of starts (NT) as an overall measure of the mobile apps’ impact. Panel B provides app-level results. We differentiate the user behavior data of the top three apps and using the number of independent active users (PI), the duration of independent usage (TI), and the number of independent starts (NI) to assess the impact of mobile apps on the inefficient investment of enterprises.

Firm-level results

The firm-level results using cumulative app data are shown in Panel A. The upper half of the results display how mobile apps affect enterprise inefficient investment, while the lower half indicates its impact on overinvestment and underinvestment. The upper half reveals that mobile apps significantly reduce inefficient investment, with regression coefficients for the number of active users, duration of use, and number of starts all negative at the 1% level. The absolute value of the impact coefficient of the number of active users on inefficient investment is 0.682, which is significantly higher than that of the duration of use and number of starts. This is attributed to the fact that the number of active users better reflects the scale and quality of the app’s user base, serving as a core measure of a mobile app’s success.

The lower half of Panel A indicates that mobile apps significantly reduce overinvestment at the 1%, 1%, and 5% levels, respectively. These levels correspond to measures using the number of active users, duration of use, and number of starts as indicators. Similarly, the regression results demonstrate that the negative impact of mobile apps on underinvestment is significant at the 1%, 1%, and 5% levels, regardless of the chosen metric for measuring enterprise mobile apps. This indicates that mobile apps also have a corrective effect on enterprise underinvestment.

Upon further comparison, it is observed that the absolute value of the impact coefficient of mobile apps on overinvestment is consistently greater than that on underinvestment. This implies that the inhibitory effects of mobile apps on enterprise inefficient investment are more pronounced in correcting overinvestment. The reason for this is that overinvestment behavior in listed companies in China is generally more evident and severe compared to underinvestment. Additionally, the descriptive statistics presented in Table 1 corroborate this, showing that the extent of overinvestment is indeed more severe among the listed companies in our sample, even though the problem of underinvestment is more common.

App-level results

To leverage detailed information from mobile apps, we employ the same estimation strategy by using the enlarged app-level sample. In Table 3, the results of the upper half of Panel B indicate that, by using the indicators of the number of active users, duration of use, and number of starts as dependent variables, the effects of mobile apps on inefficient investment are negatively significant at the 5%, 1%, and 5% levels, respectively. The absolute value of the impact coefficient of the number of active users on inefficient investment (0.505) is the largest, while that of the number of starts (0.004) is the smallest, consistent with firm-level results.

Using the same strategies, we further examine the differentiated effects of mobile apps on both overinvestment and underinvestment. Similarly, mobile apps significantly reduce overinvestment at the 1% level when measured by the number of active users and duration of use. The effects of mobile apps on overinvestment are not significant, but the coefficient remains negative when measured by the number of starts. These results align with firm-level results, further supporting the corrective effect of mobile apps on inefficient investment.

Long-term effects results

To mitigate the endogeneity issue, one strategy we use in this paper is to treat the enterprise's inefficient investment variables with one year (four quarters) and two years (eight quarters) of backward projection. We then rerun the regression in Eq. (5) to test long-term effects of mobile apps. The results, both of firm-level and app-level are shown in Table 4. We find that the mobile apps, measured by the number of active users, duration of use, and the number of starts, significantly reduce inefficient investment, overinvestment, and underinvestment in one year (four quarters) backward push, consistent with the basic results.

The results of the long-term effects of two years’ backward projection shown in the lower part of Panel A and Panel B, indicate that mobile apps, measured by the number of active users, duration of use, and the number of starts, continue to negatively impact inefficient investment. Meanwhile, the effects of mobile apps on overinvestment in the two-year backward push are negative and significant, but the absolute value of the regression coefficient is significantly reduced year-on-year. None of the effects of mobile apps on underinvestment in two years of backward push are significant. It can be seen that mobile apps not only correct current inefficient investment but also have a long-term impact, but there may be a time-decreasing trend.

Robustness checks

To examine the robustness and reliability of the basic regression results, we adopt four methods to conduct robustness tests: replacing the explanatory variables and the explanatory variables, enlarging the sample range, and instrumental variable method.

Replacing measures of inefficient investment

On the basis of Richardson’s model, we replace Tobin’s Q value with an indicator of corporate growth opportunities (the ratio of the market capitalization to the book value). Then, we reconstruct the variables for inefficient investment, overinvestment and, underinvestment. The results using these new variables are shown in row (1) of Panel A and Panel B in Table 5. Both firm-level and app-level results show that the number of active users, duration of use, and the number of starts have significant negative effects on the new inefficiency investment, with the magnitude of impact decreasing from number of active users to duration of use to number of starts. These findings align with the basic regression results in Table 3.

Using data from the top five apps

To address concerns that large firms with multiple mobile apps may exhibit different investment behaviors, potentially affecting our basic results, we replace the data from top three apps with the data from the top five apps in the basic regression. Results are shown in the row (2) of Panel A and Panel B in Table 5. Panel A presents firm-level results using the cumulative app data of the top five apps. Panel B shows app-level results of the top five apps. The findings remain consistent with the basic results in Table 3, suggesting that large firms do not dominate the outcomes in this paper.

Enlarging the samples by including H-share companies

To more comprehensively assess the impact of mobile apps on investment efficiency, we expand our sample by including H-share listed firms with mobile app data in our database, adding 19 H-share companies to the regression of model (1). Results at both firm-level and app-level show that the coefficients of the number of active users and duration of use are significantly negative on inefficient investment, while the number of starts is negative but insignificant. Overall, the results after adding the Hong Kong stock sample are still highly similar to the basic regression results.

Further analysis of overinvestment and underinvestment reveals that the number of active users and duration of use have significant negative effects on overinvestment and underinvestment, while the number of starts, which has the smallest impact, is insignificant. Specifically, the absolute values of coefficients for the impacts of mobile apps on overinvestment are greater than those of underinvestment, consistent with the basic regression results, indicating that mobile apps primarily correct overinvestment. This expanded sample analysis confirms the robustness of the basic regression results.

Instrumental variables regression

We have added firm-level control variables and controlled for time and industry-fixed effects, mitigating the omitted variable problem to some extent. However, unmeasured variables like corporate culture, which may influence both mobile apps and inefficient investment, are omitted in the regression models. More importantly, reverse causality between digital technology adoption of mobile apps and inefficient investments may exist, as firms investing in digital technology might also affect the effectiveness of mobile apps by attracting more app users. Therefore, the endogeneity issue in this study remains to be addressed. To further mitigate these issues, we introduce instrumental variables.

Specifically, user behavior of enterprise mobile apps is usually affected by the level of mobile apps in the same industry, which does not directly affect inefficient investment. Following Tao et al. (2023), we use the industry-average value of digital technology applications that does not include the company itself as an instrumental variable (IV). Since we focus on the overall mobile apps of the company affected by the level of industry application, rather than research based on the app level, we conduct the IV test using firm-level data. Results are shown in Table 6.

First, we test whether the instrumental variable is a weak instrumental variable. The results show that the value of the Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic exceeds the critical value at the 10% level (Stock and Yogo, 2005), rejecting the original hypothesis that the IV is weak and confirming the relevance. Second, we verify the exogeneity of the IV by regressing inefficient investment on mobile app variables and the IV based on the idea of Fang and Zhao (2011). If IV indirectly affects inefficient investment through the mobile apps, the impact of the IV on inefficient investment should be insignificant when controlling for mobile apps variable. The results show that the IV significantly affects inefficient investment without controlling for mobile apps but becomes insignificant after controlling for mobile apps, satisfying the exogeneity requirement of IV. The two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimates in columns (4)-(6) of Table 6 show that mobile apps have significantly negative effects on inefficient investment.

In addition, although this paper has done its best to ensure the robustness of the relationship between digital technology adoption and corporate investment efficiency by conducting robustness tests through a variety of methods, it is important to point out that the relationship may also be affected by unidentified variables or potential endogeneity issues. For example, there may be other important factors that simultaneously affect the level of corporate digital technology adoption and investment efficiency, which may not have been adequately considered or are difficult to fully control for in existing studies. Therefore, future research should explore and control these potential endogeneity issues in order to reveal more precisely the impact of digital technology adoption on corporate investment efficiency.

Mechanism analysis

Channels for agency issues

Previous theoretical analysis shows that corporate mobile apps can alleviate agency problem and correct inefficient investment by reducing management’s private costs and private gains. The reduction also lowers supervision costs and residual losses, which are important parts of agency costs. To measure agency problems, we adopt agency cost-related indicators. Existing literature often measures agency cost between shareholders and management by the indexes of management expense ratio, operation and management expense ratio, and total asset turnover ratio (Ang et al., 2000).

However, compared to the management expense ratio, which contains too much noise, the total asset turnover ratio has the advantages of less volatility and a lower degree of manipulation (Luo, 2014). Therefore, we use total asset turnover (Turnover) as a proxy for agency cost, with higher Turnover indicating lower agency cost. Results in Table 7 show that the number of active users, duration of use, and number of starts on have significantly positive effects on the total asset turnover ratio, indicating that mobile apps reduce agency costs. These results confirm that mobile apps help correct inefficient investment by alleviating agency problems, supporting the existence of this mechanism.

Channels for financing constraints

Previous theoretical analysis shows that corporate mobile apps can reduce information asymmetry between investors and enterprises, and then alleviate financing constraints by lowering financing cost and broadening financing channels. According existing literature, KZ index (Kaplan and Zingales, 1997), WW index (Whited and Wu, 2006), SA index (Hadlock and Pierce, 2010) are often used to measure financing constraints. We construct the SA index using enterprise size and the number of listing years, as follows: SAit = −0.737sizeit + 0.043sizeit2−0.04ageit. The higher SA index represents stronger financing constraints. Results in Table 7 show that the number of active users, duration of use, and number of starts significantly and negatively affect the SA index, which means that mobile apps reduce financing constraints. The above results confirm that mobile apps help correct inefficient investment by alleviating financing constraints, supporting the existence of this mechanism.

Heterogeneity analysis

Equity incentives

Reasonable equity incentives are conducive to aligning the interests of management and shareholders, improving the motivation and efficiency of management, and alleviating agency problems. Corporates without equity incentives may face greater agency problems compared to those with equity incentives. Therefore, we separate the sample into two groups based on whether management holds shares and compare the average inefficient investment levels. The results show that enterprises without equity incentives have higher average inefficient investment, confirming our conjecture. This suggests that mobile apps may have greater correcting effects on inefficient investment in firms lacking equity incentives.

To further examine this, we conduct group regression analysis based on whether the management holds shares. Results in Table 8, the upper half of Panel A and Panel B, show that regardless of equity incentives, data type or indexes used, the effects of mobile apps on enterprise inefficient investment is negative and significant, indicating that mobile apps can correct enterprise inefficient investment.

Financing structure

Debt payments, including principal and interest, dilute management’s control over internal cash flows, reducing their ability to allocate cash and discouraging investment in negative NPV projects. The periodic nature of debt payments increases pressure on management to improve investment efficiency and subjects their decisions to creditor scrutiny. While enterprises with higher debt levels are expected to invest more efficiently, high-debt can also lead to inefficiencies. Creditors get most of the benefits from investment projects, while shareholders and management bear all the costs but receive only a portion of the benefits. This misalignment may cause highly indebted firms to forgo some positive NPV projects, resulting in inefficient investment. Therefore, it is theoretically unclear under which financing structure mobile apps have a stronger corrective effect on inefficient investment.

To explore this, we conduct group regression analysis using the average ratio of total liabilities to total assets as the grouping criterion. Results in Table 8 show that mobile apps have a negative and mostly significant effect on inefficient investment across all debt levels. However, the absolute values of the regression coefficients are larger for high-debt-financed compared to low-debt-financed firms, and the differences between groups are significant for all indicators except the number of starts, which has the smallest impact. This suggests that excessive debt financing may lead firms to abandon some positive NPV projects, exacerbating inefficient investment in high-debt enterprises. Consequently, mobile apps exhibit a stronger corrective effect on inefficient investment in high-debt financing enterprises. In addition, we calculate the average value of inefficient investment for high-debt and low-debt firms. The results show that high-debt financing enterprises have a higher average inefficient investment (0.0305) compared to low-debt financing enterprises (0.0226), supporting the above conjecture.

Further analysis

Pricing models

User behavior differs between paid and free apps. In this paper, from the perspective of the app pricing model, we categorize apps into paid and free based on user payment behavior during download and usage. Since most apps are not paid downloads, we classify mobile apps in video, travel, finance, and life shopping as paid, while apps in fields like application management, utilities, communication, and information are classified as free, according to the app fields summarized in the database of Qianfan analysts.

Then, we conduct separate regressions for paid and free app groups. Results in Table 9 show that mobile apps have a more significant corrective effect on inefficient investment in enterprises with paid mobile apps compared to that with free mobile apps. This is primarily due to the cost of using such mobile apps. Free apps, with minimal user burden to download and use, are more attractive to users than paid apps. In this case, free or less-paid apps can bring a large amount of investment-related information and improve the efficiency of investment.

Brand reputation

The Top 100 Chinese Internet Enterprises list evaluates companies based on financial indexes such as revenue, profit, human capital, and business indexes such as product traffic and the number of active users, and comprehensively considers the corporate scale, social impact, development potential, and social responsibility. Inclusion in this list often means a strong brand reputation. To examine whether brand reputation influences the corrective effect of mobile apps on inefficient investment, we identify sample companies from the list, jointly published by the Internet Society of China and the Information Center of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology.

We divide the sample into brand and non-brand companies and conduct regression, respectively. Results in Table 9 show that non-brand companies have more significant corrective effects on inefficient investment compared to brand enterprises. This is because brand enterprises, with their complete internet industry chain, already leverage digital technologies to drive manufacturing and service industries. The data of mobile app users contributes only marginally to their business development, and thus they rely less on such data to convey new information for decision-making. Additionally, their strong brand reputation itself signals financial stability to investors, reducing financing constraints. In contrast, non-brand firms, which are weaker in size, social impact, growth potential, and social responsibility, depend more on mobile apps to provide valuable information for investment decisions and to correct inefficient investments.

Conclusions

Research findings

The booming development of digital technology has brought new opportunities for the transformation and upgrading of the real economy and high-quality development in recent years. In order to explore the impact of app digital technology applications on corporate investment efficiency, we collect data on the number of active users, duration of use, and starts of mobile apps ranked within the top 2000 mobile apps from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2019, on Qianfan Analysts. Then we screen out listed companies and match them with the quarterly financial indexes from the CSMAR database. The results indicate that the number of active users, duration of use, and starts of mobile apps brought by apps digital technology applications can enhance corporate investment efficiency and alleviate overinvestment and underinvestment. The findings are supported by a series of robustness checks. In addition, our mechanism tests suggest that mobile apps correct investment efficiency by reducing agency problems and alleviating financing constraints. We also perform heterogeneity tests and find that mobile apps influence enterprises’ inefficient investment by the equity incentives and financing structure. Specifically, improvement effects are stronger in firms without equity incentives and those with high-debt financing, as these firms face greater inefficiencies. Further analysis of app pricing models and corporate brand reputation finds that corporates belonging to the free apps and those not on the Internet 100 list exhibit greater efficiency improvements.

Recommendations

From the managerial perspective, firms should actively introduce digital technology applications and digitization-related talents to leverage their decision-making value in corporate investment activities. By integrating intelligent systems and digitalization-related talents, corporates can enhance investment efficiency, support scientific decision-making, and accelerate digital transformation. Additionally, establishing diversified equity incentive mechanisms can align management and shareholder interests, reducing agency problems and further improving governance. From the regulatory perspective, the government should guide corporate digitalization through policies, offering financial subsidies and incentives to motivate corporates. A differentiated digital incentive system is essential, as firms vary by ownership, industry, and location. Tailored policies should address these differences, ensuring support aligns with specific needs and promotes high-quality development of the real economy.

Limitations

However, there are some limitations of this paper. First, despite leveraging Qianfan Analysts data, the sample is limited to 31 A-share companies and 19 H-share companies. The limitation of the sample determines that the relevant statistical results of this paper need to be further tested. Second, in the measurement of digital technology application variables, relying solely on app metrics may not fully capture the diversity of digital technology applications. Future research can consider expanding samples, refining digital application metrics, and exploring other digital tools beyond mobile apps. Third, while findings suggest apps improve investment efficiency by reducing agency problems and financing constraints, other mechanisms remain underexplored, such as enhanced external monitoring through company stocks. Finally, the limited accessibility of the non-public app user data may weaken observed effects, particularly for underinvestment correction. These issues require further exploration in future research.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aben TA, van der Valk W, Roehrich JK, Selviaridis K (2021) Managing information asymmetry in public–private relationships undergoing a digital transformation: the role of contractual and relational governance. Int J Oper Prod Manag 41(7):1145–1191. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-09-2020-0675

Aggarwal RK, Samwick AA (2006) Empire-builders and shirkers: investment, firm performance, and managerial incentives. J Corp Financ 12(3):489–515. https://doi.org/10.3386/w7335

Ang JS, Cole RA, Lin JW (2000) Agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ 55(1):81–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00201

Avinadav T, Bunker AE (2022) The effect of risk aversion and financing source on a supply chain of in‐app products. Int Trans Operational Res 29(4):2145–2171. https://doi.org/10.1111/itor.13076

Bae GS, Choi SU, Dhaliwal DS, Lamoreaux PT (2017) Auditors and client investment efficiency. Account Rev 92(2):19–40. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51530

Bebchuk LA, Cohen A, Hirst S (2017) The agency problems of institutional investors. J Econ Perspect 31(3):89–112. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.31.3.89

Benlemlih M, Bitar M (2018) Corporate social responsibility and investment efficiency. J Bus Ethics 148:647–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3020-2

Bergh DD, Ketchen Jr DJ, Orlandi I, Heugens PP, Boyd BK (2019) Information asymmetry in management research: Past accomplishments and future opportunities. J Manag 45(1):122–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318798026

Bertrand M, Mullainathan S (2003) Enjoying the quiet life? Corporate governance and managerial preferences. J Polit Econ 111(5):1043–1075. https://doi.org/10.1086/376950

Bharadwaj A, Sawy O, Pavlou PA, Venkatraman NV (2013) Digital business strategy: Toward a next generation of insights. MIS Q 37(2):471–482. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37:2.3

Birch K, Cochrane DT, Ward C (2021) Data as asset? The measurement, governance, and valuation of digital personal data by Big Tech. Big Data Soc 8(1):20539517211017308. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211017308

Bzeouich B, Lakhal F, Dammak N (2019) Earnings management and corporate investment efficiency: does the board of directors matter? J Financ Report Account 17(4):650–670. https://doi.org/10.1108/jfra-06-2018-0044

Cao S, Jiang W, Yang B, Zhang AL (2023) How to talk when a machine is listening: Corporate disclosure in the age of AI. Rev Financ Stud 36(9):3603–3642. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhad021

Chen CW, Correia M, Urcan O (2023) Accounting for leases and corporate investment. Account Rev 98(3):109–133. https://doi.org/10.2308/TAR-2018-0406

Chen W, Srinivasan S (2024) Going digital: Implications for firm value and performance. Rev Account Stud 29(2):1619–1665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-023-09753-0

Chen Z, Jiang K (2024) Digitalization and corporate investment efficiency: evidence from China. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 91:101915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2023.101915

Clor-Proell SM, Guggenmos RD, Rennekamp K (2020) Mobile devices and investment news apps: the effects of information release, push notification, and the fear of missing out. Account Rev 95(5):95–115. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52625

Eichfelder S, Jacob M, Schneider K (2023) Do tax incentives affect investment quality? J Corp Financ 80:102403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2023.102403

Eller R, Alford P, Kallmünzer A, Peters M (2020) Antecedents, consequences, and challenges of small and medium-sized enterprise digitalization. J Bus Res 112:119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.004

Fang Y, Zhao Y (2011) Looking for instruments for institutions: estimating the impact of property rights protection on Chinese economic performance. Econ Res J 46(5):138–148. (Chinese version)

Farooq U, Ahmed J, Khan S (2021) Do the macroeconomic factors influence the firm’s investment decisions? A generalized method of moments (GMM) approach. Int J Financ Econ 26(1):790–801. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.1820

Feng X, Wen W (2022) Can state-owned institutional investor ownership improve corporate investment efficiency? Bus Manag J 44(1):65–84. https://doi.org/10.19616/j.cnki.bmj.2022.01.004. (Chinese version)

Fich EM, Harford J, Tran AL (2023) Disloyal managers and shareholders’ wealth. Rev Financ Stud 36(5):1837–1888. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhac070

Gao X, Xu W, Li D, Xing L (2021) Media coverage and investment efficiency. J Empir Financ 63:270–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2021.07.002

Guariglia A, Yang J (2016) A balancing act: managing financial constraints and agency costs to minimize investment inefficiency in the Chinese market. J Corp Financ 36:111–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.10.006

Hadlock CJ, Pierce JR (2010) New evidence on measuring financial constraints: Moving beyond the KZ index. Rev Financ Stud 23(5):1909–1940. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhq009

Hanelt A, Bohnsack R, Marz D, Antunes Marante C (2021) A systematic review of the literature on digital transformation: Insights and implications for strategy and organizational change. J Manag Stud 58(5):1159–1197. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12639

Hazaea SA, Al-Matari EM, Omer AM, Farhan NH, Zhu J (2024) The impact of internal audit system on performance: evidence from emerging markets. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:1307. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03835-3

He Z, Kondor P (2016) Inefficient investment waves. Econometrica 84(2):735–780. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA11788

Huang Y, Qiu J (2023) The power influence of executives and corporate investment efficiency: empirical evidence from Chinese state-owned enterprises. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:586. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02107-w

Hung WJ, Gong L, Wang Y, Wang Y (2024) Exploring the impact of auditor industry specialization on income smoothing. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:910. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03438-y

Jensen MC, Meckling WH (1976) Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. J Financ Econ 3(4):305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

Jiang F, Cai W, Wang X, Zhu B (2018) Multiple large shareholders and corporate investment: evidence from China. J Corp Financ 50:66–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2018.02.001

Jiang F, Ma Y, Wang X (2020) Multiple blockholders and earnings management. J Corp Financ 64:101689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101689

Kaplan SN, Zingales L (1997) Do investment-cash flow sensitivities provide useful measures of financing constraints? Q J Econ 112(1):169–215. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355397555163

Li D (2011) Financial constraints, R&D investment, and stock returns. Rev Financ Stud 24(9):2974–3007. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhr043

Liu Y, Dong Y, Qian W (2024) The impact of digital transformation on the quality and safety level of agricultural exports: evidence from Chinese listed companies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:817. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03321-w

Love I, Martínez Pería MS (2015) How bank competition affects firms’ access to finance. World Bank Econ Rev 29(3):413–448. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2144888

Luo M (2014) Property right, agent cost and investment efficiency—evidence from Chinese listed companies. China Soft Sci (7):172–184. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-9753.2014.07.014. (Chinese version)

Ma D, Zhu Q (2022) Innovation in emerging economies: Research on the digital economy driving high-quality green development. J Bus Res 145:801–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.03.041

Meng Q, Li X, Chan KC, Gao S (2020) Does short selling affect a firm’s financial constraints? J Corp Financ 60:101531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2019.101531

Mikalef P, Krogstie J, Pappas IO, Pavlou P (2020) Exploring the relationship between big data analytics capability and competitive performance: the mediating roles of dynamic and operational capabilities. Inf Manag 57(2):103169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.05.004

Modgil S, Gupta S, Sivarajah U, Bhushan B (2021) Big data-enabled large-scale group decision making for circular economy: an emerging market context. Technol Forecast Soc Change 166:120607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120607

Modigliani F, Miller MH (1958) The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. Am Econ Rev 48(3):261–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/1809766

Nikolov B, Schmid L, Steri R (2021) The sources of financing constraints. J Financ Econ 139(2):478–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2020.07.018

Panetta IC, Leo S, Delle Foglie A (2023) The development of digital payments–past, present, and future–from the literature. Res Int Bus Financ 64:101855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2022.101855

Perrons RK, Jensen JW (2015) Data as an asset: what the oil and gas sector can learn from other industries about “Big Data”. Energy Policy 81:117–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2015.02.020

Rajkovic T (2020) Lead independent directors and investment efficiency. J Corp Financ 64:101690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101690

Richardson S (2006) Over-investment of free cash flow. Rev Account Stud 11:159–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-006-9012-1

Sakas DP, Giannakopoulos NT, Terzi MC, Kanellos N, Liontakis A (2023) Digital transformation management of supply chain firms based on big data from DeFi social media profiles. Electronics 12(20):4219. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12204219

Stock JH, Yogo M (2005) Asymptotic distributions of instrumental variables statistics with many instruments. In: Identification and inference for econometric models: essays in honor of Thomas Rothenberg. Cambridge University Press. pp. 109–120

Sumiyana S, Na’im A, Kurniawan F, Nugroho AH (2023) Earnings management and financial distress or soundness determining CEOs’ future over-and under-investment decisions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:164. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01638-6

Sun G, Li T, Ai Y, Li Q (2023) Digital finance and corporate financial fraud. Int Rev Financ Anal 87:102566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2023.102566

Tambe P (2014) Big data investment, skills, and firm value. Manag Sci 60(6):1452–1469. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1899

Tao F, Zhu P, Qiu C, Wang X (2023) The impact of digital technology innovation on enterprise market value. J Quant Tech Econ 40(5):68–91. https://doi.org/10.13653/j.cnki.jqte.20230310.010. (Chinese version)

Ullah I, Majeed MA, Fang HX (2021) Female CEOs and corporate investment efficiency: evidence from China. Borsa Istanb Rev 21(2):161–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2020.09.010

Usai A, Fiano F, Petruzzelli AM, Paoloni P, Briamonte MF, Orlando B (2021) Unveiling the impact of the adoption of digital technologies on firms’ innovation performance. J Bus Res 133:327–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.035

Wang J, Wang H, Wang D (2021) Equity concentration and investment efficiency of energy companies in China: evidence based on the shock of deregulation of QFIIs. Energy Econ 93:105032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2020.105032

Wang S, Wen W, Niu Y, Li X (2024) Digital transformation and corporate labor investment efficiency. Emerg Mark Rev 59:101109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2024.101109

Wen H, Zhong Q, Lee CC (2022) Digitalization, competition strategy and corporate innovation: evidence from Chinese manufacturing listed companies. Int Rev Financ Anal 82:102166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2022.102166

Whited TM, Wu G (2006) Financial constraints risk. Rev Financ Stud 19(2):531–559. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhj012

Xu G, Li G, Sun P, Peng D (2023) Inefficient investment and digital transformation: What is the role of financing constraints? Financ Res Lett 51:103429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103429

Xin F, Niu Y (2023) The bank organizational level and loan contract behaviors: empirical evidence from commercial bank divisional system reform. Account Econ Res 37(2):99–117. https://doi.org/10.16314/j.cnki.31-2074/f.2023.02.008

Xue L, Dong J, Jiang S (2024) Digital financial development and inefficient investment: a study based on the dual perspectives of resource and governance effects. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:104. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02411-5

Yan Y, Wang M, Lai J (2024) Does corporate digitalization promote labor investment efficiency? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:1265. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03777-w

Yang X, Cao D, Andrikopoulos P, Yang Z, Bass T (2020) Online social networks, media supervision and investment efficiency: an empirical examination of Chinese listed firms. Technol Forecast Soc Change 154:119969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119969

Yang Y, Zhai P (2022) Click-through rate prediction in online advertising: a literature review. Inf Process Manag 59(2):102853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102853

Yermack D (2017) Corporate governance and blockchains. Rev Financ 21(1):7–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfw074

Yu J, Xu Y, Zhou J, Chen W (2024) Digital transformation, total factor productivity, and firm innovation investment. J Innov Knowl 9(2):100487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2024.100487

Zhai H, Yang M, Chan KC (2022) Does digital transformation enhance a firm’s performance? Evidence from China. Technol Soc 68:101841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101841

Zhang C, Wang Y (2024) Non-financial information farsightedness and capital market information efficiency. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:1174. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03657-3

Zhang L, Chen W, Peng L (2023) The impact of tax enforcement on corporate investment efficiency: evidence from the tax administration information system. Account Financ 63(2):1635–1669. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12921

Zhao X, Li R, He H (2022) Does digital technology promote innovation efficiency? Stud Sci Sci 41(4):732–743. https://doi.org/10.16192/j.cnki.1003-2053.20221110.004. (Chinese version)

Zhou B, Zhao S (2022) Industrial policy and corporate investment efficiency. J Asian Econ 78:101406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2021.101406

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (No. 19BJY029).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fu Xin: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision. Huimiao Yu: software, data curation, visualization, writing—review & editing. Xuan Dong: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing—review & editing. Chunhua Chen: validation, methodology, supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xin, F., Yu, H., Dong, X. et al. When the customers comes to you: mobile apps and corporate investment efficiency. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 326 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04625-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04625-1