Abstract

The authenticity of cultural features in souvenir design is increasingly emphasized by heritage tourism. This study takes souvenirs of the Moga Caves in Dunhuang, China, as an object of research and explores how designers integrate authentic cultural features of the heritage into product design. The study uses a qualitative approach to interview nine designers and two cultural experts from the souvenir design sector in Dunhuang to obtain perspectives on their consideration of authenticity in the souvenir design process. Thematic analysis was employed to identify critical patterns related to the authenticity of cultural representations in design. The findings revealed five themes: 1) Art Forms and Composition, 2) Contemporary Value, 3) Authenticity and Originality, and 4) Cultural Significance and Representation. The finding indicates that respecting Dunhuang murals’ aesthetic and historical significance while understanding their role in facilitating cross-cultural communication is vital to creating meaningful souvenirs. The study also emphasized the need for collaboration between designers and cultural authorities to ensure authenticity and relevance in the design of souvenirs. This study contributes to a broader discussion of the themes related to cultural heritage, sustainable development, and cultural product design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interdisciplinary research in design, within the context of global localization trends, highlights the critical link between design and culture. In culturally oriented design, the concept of “cultural eco-culture” is introduced as a way for designers to incorporate cultural identity into design elements. This emerging concept promotes a holistic and integrated approach that authentically and impactfully represents identity (Carlson and Richards 2011).

As advocates of culture, designers face the complex task of integrating traditional cultural knowledge with modern design language to cultivate a sustainable cultural eco-culture. Design serves as a channel for capturing ideas, creative endeavors, and entrepreneurial enthusiasm, broadening the scope of “cultural making” and delineating cultural identity (Carlson and Richards 2011). Since culture and design are inextricably linked, culturally oriented design is expected to be a crucial criterion for design evaluation in the future (Lin 2007). Incorporating cultural elements into design allows technology to align more closely with its social context, utilizing culture as a springboard for innovation (Moalosi et al. 2005). Therefore, designers must explore the complex relationship between design and culture in an interdisciplinary context. Their primary goal is to shape users’ everyday cultural experiences by creating relevant new products. Consciously or unconsciously, their work reflects the prevailing cultural ethos of their time (Lee 2004).

Incorporating cultural elements in the design process is becoming increasingly important for promoting the product’s cultural values (Wu et al. 2004; Lin 2007). As objects filled with emotions and stories, souvenirs challenge designers’ creativity. By combining local cultural elements into their creations, designers can enhance the value and identity of their products in the global marketplace. Souvenirs are tangible mementos of personal experiences and social interactions, pivotal in promoting tourism destinations and generating an organic word-of-mouth effect. Often, souvenir buyers can discern traditional designs and categories. Souvenir makers shape their products within these recognized categories, utilizing a range of symbols that travelers find essential. Thus, souvenirs contain symbols typically associated with introspective goods (Smith and Richards 2013).

Adapting products to cater to tourists’ tastes is dynamic, and changes are sometimes consistent. Despite the occasional historical or traditional motifs, new souvenir designs may not deeply reflect the producer’s cultural background. Moving from conventional, abstract motifs to more realistic interpretations may enhance the product’s visibility and fill the tourists’ knowledge gaps. It is also feasible that creators tend towards abstraction and sometimes reflect contemporary Western aesthetics (Cohen 1993). It is not uncommon for different tendencies to occur within the same cultural context (Michael HITCHCOCK 2001). Furthermore, establishing uniqueness is a common challenge when utilizing handicrafts in tourism and global trade. Although they have aesthetic appeal, many traditional products may need more variety to capture tourist interest. Decorating a product’s surface not only pleases the consumer but reinforces its origin story and adds value (Michael HITCHCOCK 2001). Integrating cultural elements into product design is a growing trend, requiring a deep understanding of cross-cultural communication to compete in the global marketplace while nurturing local design. Therefore, integrating culture and design has become a crucial topic that warrants an in-depth study of how local design is aligned with and influenced by global marketplace dynamics (Lin 2007).

Establishing a methodology to create diverse souvenirs that tell a country’s story to tourists is crucial (Owusu-Mintah 2020). While “culture-oriented design” emphasizes the importance of reflecting cultural identities in design, limited research exists on how designers can effectively translate cultural identities into design elements without compromising authenticity or meaning. In addition, research on developing a sustainable “cultural eco-culture,” particularly in balancing design innovation and cultural heritage preservation, remains inadequate. Therefore, this study aims to develop a framework that will enable designers to systematically incorporate indigenous cultural knowledge into contemporary design, ensuring that products are culturally relevant, authentic, and meaningful. This framework addresses the need for a holistic approach to “culture-oriented design” that preserves cultural heritage and promotes innovation and sustainable development. This research also explores how designers can act as culturalists and effectively apply cultural insights to their design work to create souvenirs that reflect and enhance users’ cultural identities.

This qualitative study attempted to answer the following core research questions:

How do designers integrate authentic local cultural features into souvenirs?

Other sub-research questions are as follows:

-

(1)

How do designers identify cultural features that serve as sources of inspiration for souvenir designs?

-

(2)

What factors in the design process contribute to authentic souvenir design?

Literature review and research perspective

Three cultural levels

Leong and Clark developed a multi-layered conceptual framework for examining cultural items, which comprises three distinct levels: the exterior ‘tangible’ level, the intermediary “behavioral” level, and the core “intangible” level. Their framework suggests that these layers can interact in various ways to facilitate a mutual cultural exchange to rejuvenate and modernize the foundational culture—in this case, Chinese culture. This rejuvenation seeks to infuse vitality into the culture while forging a novel product design approach that integrates contemporary Western cultural practices (Leong and Clark 2003). Expanding on this, Lee introduced a design-centric multi-tiered framework encompassing objects’ physical manifestation, the values they convey, and their foundational assumptions (Lee 2004). These layers are identified through crucial design attributes representing function, aesthetics, and symbols.

Based on previous research, R. T. Lin formulated a framework for studying cultural objects (Lee 2004; Leong and Clark 2003; Lin 2005; Moalosi et al. 2004; Wu et al. 2004, 2005). This model divides culture into three levers that align with Leong’s three layers of culture described above:

-

1.

Physical/Material: This layer includes daily related objects and tools, representing the tangible aspects of culture that can be physically touched and interacted with,

-

2.

Social/Behavior: This middle layer involves human-related rituals and customs, encompassing the social norms, behaviors, and practices that define a culture,

-

3.

Spiritual/Ideal: The innermost layer reflects the spiritual, emotional, and ideological elements of a culture, such as art and religion, which are intangible but profoundly influential.

Cultural design features

In Emotional Design, Norman introduces a holistic framework for product analysis that includes the product’s allure, practicality, and the impression it creates for users and owners. He associates various facets of a product with the different planes on which individuals interact, specifically the visceral, behavioral, and reflective levels. These correspond to distinct styles of design: visceral design targets the product’s initial visual impact; behavioral design relates to the user’s experience, including product utility and ergonomics; and reflective design involves the contemplation sparked by the product, encompassing the feelings it evokes, the reputation it imparts, and how it reflects the user’s style (Norman 2003).

The following three design features can be identified when incorporating cultural objects. These features correlate with each culture level to guide the design process:

-

1.

Visceral Design (related to the Outer level): Focuses on the user’s first impression of a product, which is influenced by visual factors such as shape, color, texture, and detailed aesthetics.

-

2.

Behavioral Design (related to the Mid-level): Emphasizes the product’s functional attributes, including ease of use, functionality, safety features, and overall satisfaction.

-

3.

Reflective Design (related to the Inner level): Relates to the product’s symbolic and personal value, such as the individual identity it supports, the emotional attachments it fosters, and the cultural connections to the user at a more profound level.

Authenticity

Souvenirs are physical reminders of a tourist’s experience and often spark discussions on authenticity. This topic has been explored in social science research by prominent scholars (Baudrillard 2016; Graburn and Jafari 1991; MacCannell 2013; Richards 2013). Studies suggest marketers sometimes create or enhance a sense of authenticity (Grayson and Martinec 2004; Milman 2015; Rose and Wood 2005), a concept relevant to designers, distributors, and retailers in the souvenir industry. Benjamin defines “aura” as an original artwork’s authenticity and unique identity, encompassing its cultural and historical significance and the specific context in which it exists (Benjamin 2008). The product’s quality, uniqueness, and cultural integrity measure the authenticity of the souvenir, which is valued for its ability to evoke connections and memories of a specific place or experience (Elomba and Yun 2018; Littrell et al. 1993). Authenticity can be inherent to an object, linked to historical context, organizational origins, or nature, or attributed to marketers and consumers, as explained by Beverland (Beverland 2005; Milman 2015).

Several studies have examined the origins and authenticity of souvenirs at major attractions (Lacher and Nepal 2011; Hashimoto and Telfer 2007; Saunders 2004) and their economic effects on local communities (Lacher and Nepal 2011). Souvenirs are a coherent whole composed of the forms and positions of original totems while also demonstrating the complex relationship between primitive totems and their adaptations (Hunter 2011; Milman 2015). Traditional items are still being produced; new designs are emerging to satisfy new market needs (Graburn 1979; Richards 2013). Souvenir products also strongly influence regional economic development and cultural inheritance. The role of the souvenir trade in protecting heritage has been the subject of several studies (Schiller 2008). However, some argue that souvenirs, especially replicas, are often considered inauthentic and, therefore, do not deserve the attention of serious collectors, museum visitors, and scholars (Richards 2013).

Most souvenir-related literature is framed within the tourism sector relating to souvenir categorization, tourists’ experiences and behaviors, and the perspectives of producers and suppliers. Researchers acknowledge the significance of crafting souvenirs that represent the origins’ cultural and historical characteristics, emphasizing the value of handcraftsmanship (Zhu et al. 2023). While most souvenir research has focused on consumers, some have approached the subject from the producers’ standpoint. Many studies concern artisan producers (Kim and Littrell 2001; Swain 1993) and the range of souvenirs from mass-produced to antique and unique items (Swanson and Horridge 2004). Additionally, studies have examined the souvenir vendors and retailers, as well as their role in the tourist experience and the destination’s sustainable development (Cukier and Wall 1994; Sambrook et al. 1992; Yamamura 2003). These articles offer extensive methods for assessing cultural products and merging theoretical ideas with tangible design practices. They emphasize the complex process of infusing cultural authenticity into products (especially souvenirs) and explore the impact of authentic products on cultural representation, economic development, and heritage preservation.

However, there is a lack of information about the experiences of designers within the souvenir development sector, which is the focus of this study. There is a discernible need in the literature to harmonize the crafted authenticity of souvenirs with their inherent cultural significance. Since designers play a crucial intermediary role in this process, investigating the experiences of designers is imperative to recognize and fully enhance their contribution to the cultural ecosystem.

Research methodology

Research design

This study employed a qualitative approach to explore the designers’ experiences using authentic features of the Mogao Cave murals in the souvenir innovation process. The goal was to preserve the region’s cultural heritage while recognizing the evolving nature of the representations (Creswell et al. 2007; Driessnack et al. 2007). A case study approach was selected to address the “how” research questions (Merriam and Tisdell 2016). Due to their strong market presence, three cases were chosen from the souvenir design departments authorized by cultural preservation institutes in Dunhuang.

The study examined the role of design in cultural heritage preservation from the designers’ perspectives. As the primary research instrument, the researcher collected, processed, and analyzed data with the flexibility to seek clarifications and corrections in real-time (Lincoln and Guba 1985, p. 194). Data collection progressed alongside analysis, allowing the researcher to extract critical insights. The study drew on multiple data sources, including in-depth interviews, observational analysis, and document review. An inductive approach was used to generate theory from the data (Strauss and Corbin 1998, p. 12). Although the researcher developed interview topics based on theoretical frameworks derived from the literature, the study remained exploratory, building on abstract and conceptual assumptions or theories rather than testing existing theories (Merriam 1998). Finally, by interpreting the data collected, co-occurring patterns and essential themes regarding the relationship between souvenir design and cultural heritage preservation emerged from participants’ descriptive narratives.

Site and participants

Dunhuang, located on the edge of the Desert in China’s Gansu province, served as the primary research site for this study. Historically, it has been a key hub on the Silk Road and is renowned for the Mogao Caves. It is home to millennia-old Buddhist murals that visually record ancient tales and religious doctrines (Zeng et al. 2022). These murals, an artistic heritage of humanity, inspire souvenir design and highlight the need for innovative preservation methods (Jiang et al. 2022).

Participants were chosen through purposive sampling based on their expertise in souvenir design, cultural product design, or heritage studies (Maxwell 2012; Patton 2002)expertise. A group of nine designers and two cultural experts working within three distinct souvenir design sectors authorized by two museums and a cultural tourism organization in Dunhuang. Semi-structured interviews were conducted, and data saturation was reached when the final interviewees provided no new information, confirming prior findings (Denzin and Lincoln 2008). The sampling process aligned with ongoing data evaluation, analysis, and collection to ensure coalesces effectively in the study (Faulkner and Trotter 2017). Table 1 consolidates the details of the eleven informants whose ages were recorded in 2023, concurrent with data collection. Designers are labeled with ‘D-‘ and pseudonyms, while cultural experts are designated with ‘E- .’ For example, D-DM/INTW/18JUL 2023 refers to an interview with designer DM on July 18, 2023.

Data collection and data analysis

Yin indicates that the data collection should connect data with the theoretical framework while ensuring construct validity and reliability from multiple sources of evidence (Yin 2018). Interviews, observations, and document analysis were employed in this research and are well-suited for gathering data (Merriam 2009; Stake 1995). Interviews were the primary method, complemented by observations of physical and online souvenir stores, design company offices, and cultural heritage sites. Additional documents data were sourced from official records of the Dunhuang Cultural Heritage Management Organization to triangulate and augment the interview data.

This study conducted 14 interviews: nine with designers who shared their experiences in souvenir design and two with cultural experts offering broader perspectives. Three pilot interviews with designers helped refine the interview protocol. Semi-structured interview questions, supplemented with probing questions, were crafted based on the research framework. Follow-up interviews were conducted online, mainly via WeChat, to clarify any ambiguities. Held from April to August 2023, all interviews were one-on-one, in-depth sessions lasting 40–60 min, recorded digitally in Chinese, and provided a comprehensive understanding of complex dynamics (Jennings 2010).

Data analysis occurred concurrently with data collection and ATLAS. ti 23 was used for thematic analysis. After data collection, findings were confirmed, refined, and rearranged, leading to adjustments in subsequent interviews. Thematic analysis, a flexible method for qualitative research, can derive themes inductively or deductively (Kasali and Nersessian 2014; Mohamed 2022). The process followed six stages: familiarizing with the data, generating codes, identifying, reviewing, naming themes, and interpreting their significance (Creswell 2013). Categories emerged through clustering similar data and systematically describing findings (Morse 2008) to answer the research questions outlined in the introduction (Bogdan and Biklen 1997; Merriam 1998). Table 2 summarizes four key themes with sub-themes and quotes illustrating their role in Dunhuang-inspired souvenir design.

This study utilized multiple sources of evidence to establish a chain of evidence, ensuring a strong connection between collected data and case findings for more excellent result reliability (Yin 2018). Key informants participated in reviewing the draft case study report, including informant review, steering group control, and expert consultation, to confirm the validity of the construct (Merriam and Tisdell 2016). In addition, a pilot study was used to avoid single-method bias.

To enhance the validity and credibility of the thematic analysis, we employed inter-rater reliability using Cohen’s kappa statistic (McHugh 2012). Two authors independently coded the interview transcripts, identifying themes and categories through an inductive approach (Neuendorf 2017). After coding, we compared the results and constructed a confusion matrix to assess agreement across four main themes. Out of 112 coding instances, 88 agreements and 24 disagreements were recorded. We calculated the observed agreement (\({p}_{o}\)) of 0.79 (\(\frac{88}{112}\)) and the expected agreement (\({p}_{e}=0.024\)) based on the distribution of codes. Applying these values to Cohen’s kappa formula \(k=\frac{{p}_{o}-{p}_{e}}{1-{p}_{e}}\), we obtained a kappa value \(k=\frac{0.786-0.024}{1-0.024}=\frac{0.762}{0.976}\approx 0.78\), indicating substantial agreement between the coders (Landis and Koch 1977). The high consistency between raters confirms that our interpretation of the topic is reliable, increasing the findings’ rigor and validity in a specialized setting.

Ethical considerations and researcher’s reflexivity

Researchers must establish their ethical stance, responsibilities, and concerns in their work (Ramazanoglu and Holland 2002) to avoid assumptions or biases during data collection while ensuring a thorough understanding of participants’ perspectives (Berger 2015). The first author, a university teacher and designer with a PhD in integrated design, leveraged her qualitative training and experience in cultural product design to emphasize participants’ narratives. However, she maintained objectivity and prevented the influence of personal bias on the study (Berger 2015).

Validity and reliability depend on the researcher’s ethical domain (Merriam and Tisdell 2016). Therefore, researchers must consider ethical issues to safeguard participants from harm in the study (Baruth 2013). The researcher obtained approval from the University Ethics Committee and sent permission to the design and culture institution. All participants were informed about the study’s purpose, signed consent forms, and had the right to withdraw (Ranjit Kumar 2019). They were treated respectfully and allowed to review all relevant documents. Pseudonyms were used to ensure confidentiality.

Results

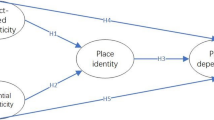

The study aims to identify the local cultural features of designing authentic souvenirs and the possible influences. When asked about the cultural features of Dunhuang, the designers generally recount their understanding of the external and internal features of Dunhuang. In contrast, cultural experts focus more on its internal identity. Participants define Dunhuang murals’ key aesthetic and artistic features, emphasizing their contemporary relevance and origins in cultural exchange. They also stress the importance of authenticity and originality in cultural product design, particularly in commercial contexts. Overall, participants affirm the cultural significance and representational role of Dunhuang heritage. Figure 1 shows the critical themes in incorporating elements of the Dunhuang Mogao murals into the design of souvenirs.

Art forms and composition

Dunhuang’s cultural and artistic heritage is rich and layered, comprising a variety of art forms and their unique interpretations. D-YQ presents that “the art of the Dunhuang caves can be broadly categorized into three parts: murals, sculptures, and architecture, each of them has a unique design aspect.” This notion is echoed by D-JJ, who suggests that “ the Dunhuang mural serves as a culmination of a master’s work or comprehensive exemplar.” Dunhuang’s artistic creations represent a historical narrative of Chinese painting; the cave art chronicles the transition from early rock art to techniques of advanced Chinese ink painting, preserving artistic methods and styles that capture the various historical epochs, such as the “depictions of blue-green landscapes from the Tang Dynasty.” Complementing this perspective, E-JYZ offers views on the expansive and enduring nature of Dunhuang’s art and culture, which is about its ethnic, local, and global aspects.

“An international brand and an inexhaustible resource for artists. Regardless of their discipline, anyone involved in art can draw inspiration from Dunhuang. Whether painting, sculpture, architecture, music, or dance, there is always something valuable to gain if you come to learn in Dunhuang.” (E-JYZ)

Dunhuang’s cultural and artistic heritage is multifaceted, with unique design elements. Its value as an international brand and a limitless source of inspiration for artists across disciplines, from painting to music and dance.

Contemporary value

Religious value

Several designers share the connection between Buddhism and the culture of Dunhuang’s caves. D-JJ observes that “the foundational elements of the art and culture in the Dunhuang caves are heavily influenced by Buddhism, with its sculptures, murals, and architectural designs all drawing from Buddhist themes.” D-XB suggests that “Mogao’s art and culture are the most reflective of the ancient Silk Road’s thousand-year culture and have immeasurable preservation value for future generations.” D-YQ and D-HP discuss how the art reflects personal experiences and religious rituals, with D-HP mentioning that “the murals are based on people’s lives and religious activities, and every year, we would go to the Mogao Caves on the Bathing Buddha Festival, partaking in activities like rejoicing with Buddha.” D-HP and E-ZYZ contribute a layered perspective, pointing out,

“The art of Mogao is more like a by-product of spreading Buddhism. As time progressed, there was a transformative shift in their significance: the caves transcended their initial religious purpose, and their artistry became more dominant and widely recognized. Moreover, what brings out the splendor of the Mogao Caves is not just Buddhism but faith, which is an expression of internalization.” (D-HP, E-ZYZ)

Once internalized and later expressed externally, the faith transforms into an artistic expression. While Mogao’s art and culture originate from Buddhist traditions, their impact extends beyond spiritual confines. The creative works act as vessels for Buddhist teachings and reflect the history, societal customs, and the potency of faith that is part of the Silk Road’s legacy. Therefore, the Mogao heritage is a cultural and spiritual treasure within the history and spiritual narrative.

Spirit value

Furthermore, the art of the Mogao Caves offers a deep reflection of the human psyche. “The mind state of the people is instrumental in shaping the artistic landscape of this region” (D-PC). The mental aspect resonates with a broader cultural ethos, “a reverence for nature as a cornerstone of Chinese philosophy” (E-ZYZ). E-ZYZ appreciates the quality of Mogao art that thrives in extreme environments, for “it represents an innate human love for life, and the essence of love is to stimulate creativity.” This idea is vividly captured in the phrase “the romance of stones blossoming, which reflects the transformative power of art in a desert landscape characterized primarily by its monotone color palette.” He further figures out that the art of Mogao fundamentally focuses on the pursuit of beauty: “This beauty serves to record history, reflect reality, and express a longing for a good life.”

The creations within Mogao are not solely depictions of historical or religious ideologies but also represent a broader spectrum of human values. E-JYZ reflects on a childhood time in Dunhuang:

“In Dunhuang, since childhood, I have been walking this path, interacting primarily with those involved in history and art—people in these cultural circles. The interconnectedness of Dunhuang’s history, art, and community creates a unique environment that attracts and inspires many as a hub for cultural exchange and artistic innovation.” (E-JYZ)

Ultimately, the artworks of the Mogao Caves are not just historical chronicles or manifestations of aesthetic concepts but a “mirror reflecting the human condition,” in the words of E-ZYZ. Dunhuang art witnesses the indomitable human spirit, from fostering creativity to overcoming harsh environmental conditions, from filtering negativity to manifesting the beauty of life. The unique blend of psychological, cultural, and ecological factors gives Dunhuang art enduring appeal.

Authenticity and originality

Authenticity in representation

Authenticity is essential in portraying traditional art forms such as the murals of Dunhuang. D-HP suggests adhering to original methods and materials to ensure replicas are as authentic as possible.

“Mud Board Paintings are locally sourced in Dunhuang, the soil from the local Dangquan River, to restore the previous craftsmanship or material. The reproduction process for Mud Board Paintings follows the original creation methods, from making the mud board to drying and painting, reflecting the accumulation of many dynasties.” (D-HP)

Such practices achieve “a sense of restoring the old with the old.” The key is to set boundaries and maintain the integrity of the original elements instead of reinterpreting or modifying them in pursuit of a creative vision. D-HP suggests that some of the “masterpieces painted by our ancestors can be kept intact or carried in a more popular or better product form… and there’s no need to redraw or reimagine them.” The reason is that the works made by the ancestors have an intrinsic value that modern adaptations cannot surpass. He said, “We won’t change these things, even if it means incurring a loss, still insisting on presenting the authentic feel of the Dunhuang murals in the products.” This view suggests that innovation is a cautious approach to respecting tradition and avoiding unnecessary alterations. D-FF pays particular attention to “restoring the mural’s original color and enhancing it.”

However, what worried D-HP was the rise of online products that claimed to be inspired by Dunhuang but lacked recognizable or authentic elements from the Mogao Caves. He asserts that while creativity and adaptability are essential, some aspects or “roots” are non-negotiable and should “remain intact.” Therefore, balancing the complexities of tradition and innovation becomes particularly important in adapting traditional Dunhuang elements into modern products. E-ZYZ also outlined the importance of balancing “local authenticity and overall authenticity” in product design.

Authenticity of design elements

Some designers are dedicated to authentically preserving the historical appearance and intrinsic style of the Dunhuang Mogao Murals when they design souvenirs. D-FF insists on fidelity to the initial creation, remarking, “Firstly, it will still be based on the original image and color.” She references features such as “the wings of the winged horse” can be “customized according to the image of the mural.” Further detailing her approach, she says, “I don’t want to rebuild a Mogao Mural; instead, I want to present it more completely to everyone.” D-XB draws attention to the time-weathered nature of the murals, describing that “the mural has a mottled feel because it has gone through more than 2,000 years of oxidation.” By mentioning a mural adorned with diminutive Buddha faces that have darkened over centuries, she dedicates balance to honoring the original hues while infusing modern elements that resonate with contemporary viewers. Similarly, D-JJ also presents the necessity of “ensuring the original color of the mural” and is prudent to avoid “major changes” to the coloration, considering both its style and “painting by use mineral pigments.”

Essentially, these designers are committed to preserving the murals’ original character and the venerable patina they have acquired over time. Their overarching design philosophy is anchored in the principle of honoring and safeguarding the core attributes like form and hue that define the cultural heritage with which they engage.

Ethics and credibility in design

D-PC and D-HP affirm the close relationship between “authority” and “authenticity” in cultural heritage and design. D-PC emphasizes the importance of authoritative institutions, such as the Dunhuang Academy and Dunhuang Cultural Tourism Group, which lend legitimacy to their work. D-HP notes that the market responds favorably to expert artisans’ authentic works and craftsmanship, like the Dunhuang Academy’s seasoned painters. Despite higher costs, discerning clients value genuine artistry and are willing to invest in it. He advises artists to remain true to their vision, encouraging them to “follow your path” and appeal to those who genuinely appreciate their efforts rather than catering to the masses. According to him, achieving commercial success and artistic integrity depends on concerning the niche audience while maintaining authenticity. When a recognized authority endorses this view, it becomes a defining feature in the cultural heritage marketplace.

Nevertheless, a particular conflict exists between maintaining authenticity in design and personal bias when developing products influenced by cultural heritage. D-HP observes that designers with prestigious academic backgrounds may inject “a strong sense of individualism into their work, sometimes overloading it with too many ideas.” This over-personalization can diminish the authenticity and core identity of the cultural elements represented. Thus, despite their visual appeal, these products need a deeper, more authentic connection to the culture they depict.

“Adhering to the classics or the source is crucial, especially with the cultural elements. But sometimes, if the designer is too individualistic, they may ‘draw legs on a snake.’ These Dunhuang Ips look beautiful but have nothing to do with Dunhuang.” (D-HP)

Balancing authority and authenticity in cultural heritage design is essential for artistic integrity and commercial success.

Cultural significance and representation

Cultural significance of iconic Dunhuang elements

D-PC regards the historical and cultural relevance of the motifs used in design. He notes, “If we trace its origins, it has wide applications in early Europe and Central Asia, for instance, the pattern of Three Rabbits and Four Rabbits Share Ears. This choice is far from arbitrary.” Such choices are deliberate and informed by “its historical background, as well as the pattern’s development, transformation, and evolution.” The thorough understanding and precise representation of cultural narratives significantly inform their design choices. “If the amount of knowledge or the clarity of the cultural narrative is sufficiently clear and can present a particularly grand cultural state, we are more willing to undertake such work.” This method proves their comprehensive research and dedication to historical and cultural authenticity. D-XB affirms the lasting significance and charm of Dunhuang’s iconic motifs.

“Like the Feitian (flying Apsara) and the Jiuselu (Nine-Colored Deer) have been well-known, continuously circulated classic elements; these are certain ‘hot’ cultural IPs, lots of souvenirs based on the elements, so this IP has been popular from the beginning to now in this culture category” (D-XB).

When designers follow historical authenticity and deeply understand the cultural meaning in the design process, they foster an ongoing dialogue about the role of cultural heritage in modern design.

Cultural interpretation and storytelling

Drawing on cultural heritage, designers such as D-DM, D-XB, and D-JJ consider not only the visual appeal of products but also incorporate the functional and cultural significance of the murals into their work. D-XB explains the dual role of the “ ZaojingFootnote 1“ architectural element, which is decorative and implies fireproofing.

“The symbolism of Zaojing is quite apparent; it was originally a metaphor for fire prevention in (Chinese) ancient architectural decoration…So, when we utilize the Zaojing in our designs, we use some design techniques that strongly connect to water and fire.” (D-XB)

Similarly, D-JJ delivers a holistic approach that combines cultural expression with modern product design. She mentions a tearable note tab designed in the image of the Mogao Grottoes cliffs at Dunhuang, infused with the thematic idea of “Lighting Up Mogao, which is about conveying a topic of guardianship.” This concept presents the ideological dimension of product design, which essentially means to evoke the consumer’s memories of a specific cultural or historical context for achieving a visually appealing product with desirable value. In discussing the distinctive approach to product design and display, D-JJ refers to ‘product stories’ that distinguish their items from other museums.

“ What sets us apart from other museums is our product’s story. It concentrates on the product’s cultural essence, connection with Dunhuang, and practical usefulness. The explanation combines the content with the product itself. This storytelling could extend to the product details page.” (D-JJ)

These approaches rely on designers’ comprehensive understanding of connecting cultural heritage and commercial products, which can bridge the gap between culture and consumer goods.

Discussion

The cultural identity of a property is shaped through the interpretive lens of the designers. The extent to which designers grasp cultural identity dramatically influences how they handle the design elements. Given their educational backgrounds and professional experiences, many designers have a multi-layered perception of cultural elements. The Dunhuang Mogao Cave murals embody East-West cultural exchange, a collection of aesthetics, styles, and artistic narratives, and a record of cultural fusion along the ancient Silk Road. The murals possess artistic value, religious value, and spiritual meaning, offering opportunities for positive reinterpretation and application of historical and cultural insights to meet modern needs. It provides design inspiration and commercial chances for contemporary souvenir designers. However, one challenge is to express the cultural identity of the heritage in the products while appealing to the tastes and cultural sensitivities of the contemporary generation.

Designer interpretations of heritage culture features in souvenir

Synthesizing the insights of designers and cultural experts, the uniqueness and importance of Dunhuang culture are reflected in three cultural dimensions: physical, social, and spiritual.

On the material level, the Mogao Caves, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, contain a wealth of murals, sculptures, and architectural designs dating back over a thousand years (Zeng et al. 2022). Designers in this study first respected these murals’ aesthetic and historical significance as sources of inspiration. This observation aligns with cultural heritage and can shape modern cultural construction and aesthetics through transmission (Song 2021).

Socially, the murals depict the intersection of multiple cultures, reflecting a social structure characterized by tolerance, integration, and exchange. Designers incorporate these motifs into modern products to celebrate multicultural history and promote appreciation of ancient customs to support arguments that historical art forms influence contemporary consumer culture (Cave and Buda 2013). Spiritually, the Mogao murals embody profound Chinese philosophical and religious concepts. Designers’ insights into these spiritual values align with Chen and Hua’s discussion of the aesthetic spontaneity of the murals, highlighting their potential integration with contemporary art (Chen and Hua 2021).

The designers began by respecting the aesthetic and historical significance of the murals of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang as a source of inspiration. From these dimensions, designers can create authentic, meaningful, and appealing products for local and international audiences. Thus, preliminary findings suggest that incorporating these three cultural layers in souvenir design may be associated with enhanced cultural preservation and commercial success, which coincides with recent literature exploring the role of cultural heritage in modern design, particularly how historical art forms resonate in contemporary consumer culture (Cave and Buda 2013; Ponimin 2021; Zhu 2013).

In contrast to previous research focusing on the artistic characteristics and expressions of historical artifacts, this preliminary finding delves into designers’ practical understanding of cultural elements and their application in products that conform to market trends. This study contributes to the broader discussion of preserving cultural heritage through design.

Balancing authenticity and originality in the design of cultural souvenirs

The findings also discuss how the designers comprehend, construe, and utilize cultural elements to ensure the artifacts produced are true to their origins. The consensus among designers is that authentic expression portrays cultural symbols, traditions, and values, while authentic cultural reproduction is about the faithful and respectful dissemination of cultural practices and artifacts. Achieving authenticity in design involves multiple dimensions, including innovation, trustworthiness, accuracy, and the ability to replicate authentically.

Designers affirmed the close relationship between authority and authenticity in product design. These observations align with prior studies on design authenticity. Benjamin, for example, posits that art should be removed from its ritual context when artifacts aim to become objects within art’s narrative of authenticity (Benjamin 2018). Authenticity is seen through the lens of belief and imagination as evidence and a social construct (Grayson and Martinec 2004). Some designers note that the marketplace favors the authenticity and mastery of professional artisans and artists to stick to their ideals and appeal to those who genuinely appreciate them rather than catering to the masses. Expertise can be validated and linked with authoritative certifying bodies with measurable qualities like attributed originality and replicated authenticity, which serve as metrics for objective authenticity (Harkin 1995). The authenticity and reliability of a product or experience are scrutinized in various contexts. Gilmore and Pine discuss consumer perceptions of authenticity, which relate to our understanding of authenticity in design elements and cultural representations, as these perceptions shape design practices and the ethical framing of cultural elements (Gilmore and Pine 2007).

Besides, there is an ethical aspect to design wherein designers actively ensure the integrity and authority of cultural elements and deliberately eschew personal biases that could skew the authenticity of the murals. Ethical dilemmas in design are multifaceted, touching on authenticity, integrity, intellectual property, inclusivity, and sustainability. Authenticity suggests originality and adherence to domain-specific norms (Asplet and Cooper 2000; Beverland 2005; Hashimoto and Telfer 2007). Objective authenticity is “original” authenticity (Wang 1999, p. 353). At the same time, Engeset & Elvekrok utilize the ‘concept of authenticity’ to assess the genuine nature of attractions and places, stressing the significance of originality and authority (Engeset and Elvekrok 2014). Authenticity narrates a dedication to artisanal skill and production excellence, a declaration of traditional commitments, and an explicit critique of modern industrial techniques and commercial objectives (Beverland 2005).

This initial finding is significant because a review of the authenticity literature revealed a lack of empirical research dealing with designers’ perceptions of the identity of cultural elements. This gap provides an opportunity for further research in this area, including those focusing on designers’ ethical considerations and the balance between authenticity and originality. By exploring how designers navigate this balance, cultural institutions and practitioners are good at meeting the need for ethical and credible design practice. In terms of implementation, first and foremost, to maintain the credibility and authority of the design, designers should avoid appropriating or distorting cultural symbols and practices, including by conducting thorough research, consulting with relevant cultural experts, and obtaining permission or authorization to incorporate culturally significant elements into design projects. By adhering to a code of ethics, designers can establish credibility and authority in their work and foster trust and respect among the cultural communities they engage with. Second, designers should reflect critically on their biases and perspectives and avoid imposing their interpretations on cultural elements. In addition, accepting different perspectives and engaging in a co-design process that involves members of the represented culture can enrich the authenticity of the design outcome.

Positive representations of heritage and cultural identity in souvenir design

Research has shown that incorporating heritage and cultural features in souvenir design positively affects cultural preservation and market relevance. Designers and cultural experts engage in cultural interpretation, storytelling, symbolization, and representation to create products that reflect Dunhuang’s cultural identity and promote cross-cultural connections. Incorporating symbolic elements from Dunhuang culture may be associated with enhanced cultural preservation and commercial success in souvenir design. This view aligns with previous studies highlighting heritage elements’ socio-economic and cultural importance and their role in sustainable development (Gražulevičiūtė 2006). Ruan (2023) explains the cultural symbolism of Dunhuang’s motifs and their inherent evolution and preservation. Similarly, Miao emphasized the cultural connections and emotional resonance between Dunhuang culture and countries associated with the Belt and Road Initiative, illustrating Dunhuang’s role in promoting cultural development and exchange (Miao 2022). As Song suggests, Dunhuang art draws inspiration from its historical murals to encourage new forms of expression in contemporary art, indicating that Dunhuang’s historical significance positively affects modern art and design (Song 2021).

This study enriches the literature on cultural heritage and product design by analyzing these elements’ cultural significance and expression. As prior studies have often focused on the socio-economic and cultural importance of heritage elements but have not profoundly explored the complexity of cultural interpretation and representation in product design (Gražulevičiūtė 2006; Ruan 2023), this research employs different perspectives and approaches from the experience of designers and cultural experts. This approach enriches our understanding of the cultural importance of Dunhuang ornamentation and contributes to a larger scholarly conversation about cultural heritage. It acknowledges the dynamic nature of cultural interpretation, the impact of globalization on cultural heritage, and the interaction of traditional cultural symbols with the contemporary environment. The role of storytelling in conveying cultural meaning is particularly crucial.

Designers advance the narrative of cultural preservation through the medium of design. In this process, maintaining the authenticity of these designs is vital to preserving the integrity of the ancient art for contemporary and future appreciation.

Conclusion

This study investigated the practical challenges and creative strategies designers and cultural experts face when incorporating authentic local cultural characteristics into souvenir designs, using three souvenir design departments in the Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes as case studies. The study’s results, which were revealed through a thematic analysis of interviews with nine designers and two cultural experts, revealed several key insights directly related to the research objectives. This study shows the practical challenges and creative strategies designers and cultural experts employ in integrating authentic local cultural features into souvenir design, specifically focusing on the Dunhuang Mogao Cave murals.

First, authentically and accurately conveying the characteristics of cultural heritage became the main challenge for designers. They acknowledged that understanding and respecting the traditional aesthetics and historical value of cultural heritage elements is an essential requirement for designers. Second, designers adopted innovative strategies to incorporate authentic cultural characteristics into souvenirs. They studied the aesthetic and cultural meanings of cultural relics, such as the murals of the Mogao Grottoes, in-depth to ensure that while preserving the cultural integrity of these elements, they are also transformed in a restrained manner that resonates with contemporary consumers. Third, collaboration between designers and cultural experts was identified as a key factor in maintaining the authenticity and originality of souvenirs. This collaboration can enhance the value and appeal of souvenirs in the market and should become a guiding principle for the design industry. Finally, adherence to design ethics is one of the fundamental requirements for ensuring the cultural integrity of souvenirs.

The study also revealed that designers act as intermediaries, connecting ancient heritage to the contemporary cultural context. By integrating storytelling, symbolism, and cultural interpretation into their designs, they foster cross-cultural connections and contribute to the sustainable development of cultural heritage. This approach enriches the narrative of cultural preservation, ensuring that the stories and symbols of the past continue to be represented and appreciated in the present and future.

However, the research suggested the contradictions designers face in pursuing originality. While striving to meet the needs of different consumers, the authenticity of cultural heritage may be undermined. Therefore, the relationship between cultural traditions and innovative design must be handled carefully to enrich the contemporary narrative of cultural preservation.

Although providing a unique perspective on designers’ views of originality and innovation in souvenir design, this study has limitations. The small sample for this study was limited to the specific heritage site of Dunhuang, China, and is not representative of the broader community of designers; therefore, it cannot be assumed that participants have the same experiences and perceptions as other cultural product designers. In addition, the participants interviewed may differ from designers and cultural experts in different sectors in terms of their traits or experiences, for example, by having different design philosophies.

Future research could focus on specific collaboration models between designers and cultural experts. In addition, quantitative studies are recommended to explore a more diverse range of cultural contexts and artifacts using quantitative methods to assess the impact of authentic design on consumer behavior and the economic success of cultural souvenirs. At the same time, the study should be extended to different cultural heritage contexts to explore further issues related to souvenir design’s commitment to cultural heritage preservation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Cave Roof Decoration in Dunhuang Caves.

References

Asplet M, Cooper M (2000) Cultural designs in New Zealand souvenir clothing: The question of authenticity. Tour Manag 21(3):307–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00061-8

Baruth GD (2013) Exploring the experiences and challenges faced by school governing bodies in secondary schools in the province of KwaZulu Natal. University of South Africa

Baudrillard J (2013) Symbolic exchange and death. London: Sage

Benjamin W (2018) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In: A museum studies approach to heritage. London: Routledge, pp. 226–243

Berger R (2015) Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Res 15(2):219–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475

Beverland MB (2005) Crafting Brand Authenticity: The Case of Luxury Wines*. J Manag Stud 42(5):1003–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00530.x

Bogdan R, Biklen SK (1997) Qualitative research for education. Allyn & Bacon, Boston, MA

Carlson D, Richards B (2011) Design+Culture: A Return to Fundamentalism. http://davidreport.com/the-report/design-culture-time-cultural-fundamentalism/

Cave J, Buda D (2013) 7. Souvenirs as Transactions in Place and Identity: Perspectives from Aotearoa New Zealand. In: Tourism and Souvenirs, vol. 33. Multilingual Matters, pp. 98–117. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781845414078-008

Chen H, Hua L (2021) To Reform and Develop Based on the Past: the Aesthetic Study of Dunhuang Murals and its Self-disciplined Development. Int J Front Sociol 3(5):97–99. https://doi.org/10.25236/ijfs.2021.030517

Cohen E (1993) The study of touristic images of native people: Mitigating the stereotype of a stereotype. In: Tourism Research: Critiques and Challenges, 36–69. London and New York: Routledge

Creswell JW (2013) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Creswell JW, Hanson WE, Clark Plano VL, Morales A (2007) Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. Counc Psychol 35(2):236–264

Cukier J, Wall G (1994) Informal tourism employment: vendors in Bali, Indonesia. Tourism Manage 15(6):464–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(94)90067-1

Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (2008) Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In: Strategies of qualitative inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, inc, pp 1–43

Driessnack M, Sousa VD, Mendes IAC (2007) An overview of research designs relevant to nursing: part 2: qualitative research designs. Rev Lat Am de Enferm 15(4):684–688. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692007000400025

Elomba MN, Yun HJ (2018) Souvenir authenticity: The perspectives of local and foreign tourists. Tour Plan Dev 15(2):103–117

Engeset MG, Elvekrok I (2014) Authentic Concepts: Effects on Tourist Satisfaction. J Travel Res 54(4):456–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514522876

Faulkner SL, Trotter SP (2017) Data Saturation. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, Vol 1, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, pp 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0060

Gilmore JH, Pine BJ (2007) Authenticity: What consumers really want. Boston: Harvard Business Press

Graburn NHH (1979) Ethnic and tourist arts: Cultural expressions from the fourth world. Oakland: University of California Press

Graburn NHH, Jafari J (1991) Introduction: Tourism social science. Ann Tour Res 18(1):1–11

Grayson K, Martinec R (2004) Consumer perceptions of iconicity and indexicality and their influence on assessments of authentic market offerings. J Consum Res 31(2):296–312. https://doi.org/10.1086/422109

Gražulevičiūtė I (2006) Cultural Heritage in the Context of Sustainable Development. Environmental research, engineering and management 3(37):74–79

Harkin M (1995) Modernist anthropology and tourism of the authentic. Ann Tour Res 22(3):650–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00008-T

Hashimoto A, Telfer DJ (2007) Geographical representations embedded within souvenirs in Niagara: The case of geographically displaced authenticity. Tour Geographies 9(2):191–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680701278547

Hitchcock M (2013) Souvenirs and cultural tourism. In The Routledge handbook of cultural tourism. Routledge, pp. 201–206

Hunter WC (2011) The Good Souvenir: Representations of Okinawa and Kinmen Islands in Asia. J Sustain Tour 20(1):81-99 https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.586571

Jennings G (2010) Chapter 5. Research Processes for Evaluating Quality Experiences: Reflections from the ‘Experiences’ Field(s). In: The Tourism and Leisure Experience, Vol 44, Multilingual Matters, pp. 81–98. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781845411503-008

Jiang C, Jiang Z, Shi D (2022) Computer-Aided Virtual Restoration of Frescoes Based on Intelligent Generation of Line Drawings. Mathematical Problems in Engineering. 2022(1):9092765 https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9092765

Kasali A, J. Nersessian N (2014) Evidence-based design in practice: a thematic analysis. Rev Arquitectura 18(26):4. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-5427.2012.32536

Kim S, Littrell MA (2001) Souvenir buying intentions for self versus others. Ann Tour Res 28(3):638–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00064-5

Kumar R (2019) Research Methodology a step-by-step guide for beginners. SAGE Publications Ltd

Lacher RG, Nepal SK (2011) The economic impact of souvenir sales in peripheral areas: a case study from Northern Thailand. Tour Recreat Res 36(1):27–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2011.11081657

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

Lee K-P (2004) Design Methods for Cross-Cultural Collaborative Design Project. Futureground DRS Int Conf 2004:17–21

Leong D, Clark (2003) Culture-Based Knowledge Towards New Design Thinking and Practice — A Dialogue. Des Issues 19(3):211–212

Lin RT (2005) Creative learning model for cross cultural product. Art Apprec 1(12):52–59

Lin RT (2007) Transforming Taiwan aboriginal cultural features into modern product design: A case study of a cross-cultural product design model. Int J Des 1(2):45–53

Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Sage publications

Littrell MA, Anderson LF, Brown PJ (1993) What makes a craft souvenir authentic? Ann Tour Res 20(1):197–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(93)90118-M

MacCannell D (2013) The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. Univ of California Press

Maxwell JA (2012) Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Sage publications

McHugh ML (2012) Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia Med 22(3):276–282

Merriam SB (1998) Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. Revised and Expanded from” Case Study Research in Education.” Jossey-Bass Publishers

Merriam SB (2009) Qualitative research a guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Merriam SB, Tisdell EJ (2016) Qualitative research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Jossey-Bass, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

Miao Y (2022) The Role of Dunhuang Culture in the Context of “One Belt, One Road.” In Proceedings of the 2022 5th International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences (ICHESS 2022) 2566–2575. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-494069-89-3_294

Milman A (2015) Preserving the cultural identity of a World Heritage Site: The impact of Chichen Itza’s souvenir vendors. Int J Cult Tour Hospitality Res 9(3):241–260. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-06-2015-0067

Moalosi R, Popovic V, Hudson A (2004) Socio-cultural factors that impact upon human-centred design in Botswana. In Proceedings Design Research Society International Conference 1–11. http://eprints.qut.edu.au/2740/

Moalosi R, Popovic V, Hudson A, Kumar KL (2005) Integration of culture within Botswana product design. In: Futureground: Vol 2: Proceedings, pp. 1–11

Mohamed Z (2022) Contending With the Unforeseen “Messiness” of the Qualitative Data Analysis Process. Waikato J Educ. https://doi.org/10.15663/wje.v27i2.945

Morse JM (2008) Confusing categories and themes. In Qualitative health research, 18. Sage CA, Los Angeles, CA, pp. 727–728

Neuendorf KA (2017) The content analysis guidebook. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Norman DA (2003) Emotional design: People and things. JND Org, 1–10. http://katsvision.com/canm606/session_4/M4_Emotional_Design.pdf

Owusu-Mintah S (2020) Souvenirs and Tourism Promotion in Ghana. Int J Technol Manag Res 1(2):31–39. https://doi.org/10.47127/ijtmr.v1i2.21

Patton MQ (2002) Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Sage publications

Ponimin (2021) Diversification of ceramic craft for tourism souvenir: local culture as art creation and production idea. Int J Vis Perform Arts 3(1):33–42. https://doi.org/10.31763/viperarts.v3i1.276

Ramazanoglu C, Holland J (2002) Women’s sexuality and men’s appropriation of desire. In Up against Foucault. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 249–274

Smith M, Richards G (2013) The Routledge Handbook of Cultural Tourism. London and New York: Routledge

Rose RL, Wood SL (2005) Paradox and the consumption of authenticity through reality television. J Consum Res 32(2):284–296. https://doi.org/10.1086/432238

Ruan Y (2023) Exploring the Symbolism and Cultural Importance of Dunhuang Lotus Motifs. Int J Educ Humanit 10(3):3–5

Sambrook RA, Kermath BM, Thomas RN (1992) Seaside resort development in the dominican Republic. J Cultural Geogr 12(2):65–75

Saunders KJ (2004) Creating and Recreating Heritage in Singapore. Curr Issues Tour 7(4–5):440–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500408667999

Schiller A (2008) Heritage and Perceptions of Ethnicity in an ‘Italian’ Market: The Case of San Lorenzo. J Herit Tour 3(4):277–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/17438730802366573

Song Y (2021) The Impact of Dunhuang Murals on Modern and Contemporary Chinese Art. In Senior Projects Spring 2021, 107

Stake RE (1995) The Art of Case Study Research. Sage Publications, Inc

Strauss A, Corbin J (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. SAGE Publications Inc

Swain MB (1993) Women producers of ethnic arts. Ann Tour Res 20(1):32–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(93)90110-O

Swanson KK, Horridge PE (2004) A structural model for souvenir consumption, travel activities, and tourist demographics. J Travel Res 42(4):372–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504263031

Wang N (1999) Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann Tour Res 26(2):349–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00103-0

Wu T-Y, Cheng H, Lin R (2005) The study of cultural interface in Taiwan Aboriginal Twin-Cup. In: HCI International 2005 22–27

Wu T-Y, Hsu C-H, Lin R (2004) The study of Taiwan aboriginal culture on product design. Proc Des Res Soc Int Conf Pap 238:377–394

Yamamura T (2003) Indigenous society and immigrants: tourism and retailing in Lijiang, China, a World Heritage city. TOURISM Int Interdiscip J 51(2):215–235

Yin RK (2018) Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. SAGE Publications, Inc

Zeng Z, Sun S, Li T, Yin J, Shen Y (2022) Mobile visual search model for Dunhuang murals in the smart library. Libr Hi Tech 40(6):1796–1818. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-03-2021-0079

Zhu M (2013) The analysis of dalian special tourism souvenirs. Proc Int Conf Adv Inf Eng Educ Sci, ICAIEES 2013:253–255

Zhu Q, Rahman R, Alli H, Effendi RAARA (2023) Souvenirs Development Related to Cultural Heritage: A Thematic Review. Sustainability 15, 2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042918

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants involved in this study for their expertise.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QZ conceptualized the investigation and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. RR reviewed and supervised. QZ and RR analyzed and interpreted the results. All authors reviewed subsequent versions of the manuscript several times. All authors have read and agreed to the published manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The interview and methodology for this study were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University Putra Malaysia (JKEUPM) (Approval No. JKEUPM-2022-363).

Informed consent

The authors obtained written consent from the individuals who participated in the study before data collection. The identity details of the study participants were not described in writing, and in the report, the study participants were given pseudonyms. The authors obtained consent from the participants to publish their data before submitting it to the journal.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Q., Rahman, R. Authenticity in souvenir design integrating cultural features of Dunhuang’s mural heritage: a qualitative inquiry. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 403 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04710-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04710-5