Abstract

Social media and public attention have resulted in an excessive concentration of humanitarian relief goods in high-exposure disaster areas and supply shortages in surrounding areas, which we refer to as a “celebrity disaster area effect”. This study uses system dynamics modeling and simulations to explore the impact of this effect on the humanitarian supply distribution during the 2022 Luding earthquake. We establish a celebrity disaster area effect measurement model that introduces a deprivation cost concept. We found that adjusting the overall public opinion to 70% of its current level is the most effective way to mitigate the celebrity disaster area effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The scale and scope of humanitarian action are also expanding (Swaminathan, 2018) because of the increased frequency of disaster events (EM-DAT, 2024, Guha-Sapir et al., 2017). The latest “Global Humanitarian Assistance Report” stated that the global number of people in need of humanitarian assistance grew by one-third in 2022–2023 to an estimated 406.6 million (Urquhart et al., 2022), and international humanitarian aid donations increased by 27% to 46.9 billion USD. While these humanitarian funds provided significant assistance to countries and regions in deep crisis, the assistance revealed humanitarian logistics problems (Prakash et al., 2022). One notable issue has been the uneven distribution of humanitarian supplies due to media attention and public opinion, a phenomenon we refer to as the “celebrity disaster area effect” in this paper, which is when the central disaster area receives media attention and consequently becomes the primary area for humanitarian relief, leaving the other surrounding severely affected areas with insufficient relief.

With the development of communication technology, the use of social media has significantly changed the way humanitarian operations are carried out. First, the media attention generated by discussions on social media greatly influences the amount of humanitarian donations (Eftekhar et al., 2017). Additionally, humanitarian organizations are progressively utilizing real-time data from social media to assess disaster risks, save lives, and provide assistance to those in distress (Vieweg, 2012, Sodhi, Tang (2014)). However, at the same time, the use of social media has also brought a certain degree of negative impact on humanitarian operations. For example, fake news and misinformation on social media have significantly reduced the efficiency of humanitarian disaster response (Li and Sakamoto, 2015). Furthermore, unequal attention on social media has led to an unequal distribution of humanitarian resources (Zheng et al., 2024).

Research has found that social media platforms, such as Twitter and Facebook, have become major information sources for determining unfolding disaster situations (Bakillah et al., 2015; Crooks et al., 2013, Swaminathan, 2018). However, social media has significant unstructured data and unverified content, much of which is inaccurate (Gürer et al., 2023), the massive humanitarian response to it has resulted in traffic jams, supply chain bottlenecks, and serious inaccuracies in assessing post-disaster needs (Maghsoudi and Moshtari, 2021). For example, the media attention after the 2017 Kermanshah earthquake resulted in many people and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) lacking the necessary expertize seeking to assist in the humanitarian logistics operations, which led to relief goods waste (Hosseini et al., 2023) and herding behaviors in humanitarian logistics driven by information from the internet and social media (Davies and Klasen, 2019).

To create a good public image, many international NGOs and humanitarian organizations prefer to operate in areas that have high media exposure (Jones et al., 2023; Eftekhar et al., 2017). Therefore, compared with government post-disaster relief, the humanitarian relief “celebrity disaster area effect” is much more significant as it can cause serious goods surpluses in the celebrity disaster areas and insufficient relief goods in surrounding areas (Heaslip et al., 2019). For example, most humanitarian relief supplies after the 2023 Turkey-Syria earthquake were sent to Turkey, while Syria, which also suffered severe earthquake damage, received inadequate humanitarian assistance (Jones et al., 2023; Anadolu Agency, 2023, France 24, 2023). During the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan at the end of 2019, many of the humanitarian medical supplies donated by the public were delivered to the large city center hospitals and the makeshift hospitals that had received the most media attention. However, community hospitals and primary healthcare workers on the city outskirts did not receive sufficient medical resources (Lu and Wang, 2023).

The “celebrity disaster area effect” generated by social media also results in many unsolicited and sometimes unwanted donations by aid agencies (Chomilier et al., 2003). These can include drugs and food that are past their expiry dates (Murray, 2005), laptops that require power, and heavy clothing unsuitable for tropical regions (Dignan, 2005).

To investigate the impact of the “celebrity disaster area effect” on humanitarian logistics, this paper uses system dynamics (SD) to establish a humanitarian distribution model under the influence of social media to examine the 2022 Luding earthquake in China as a case. Using SD simulation, we explore the celebrity disaster area effect on humanitarian logistics and the methods to mitigate it, the results from which can provide suggestions and guidance to future humanitarian organization actions.

Literature review

Our post-disaster humanitarian goods distribution system dynamics model quantifies the media attention impact on relief goods donations and distribution. Therefore, our literature review first examines the existing research on the impact of social media on humanitarian operations and the distribution of humanitarian goods, and then discusses the research methods related to humanitarian logistics. It also highlights the methods and research focus adopted in this study.

Social media significantly influences humanitarian operations, partly because social media disaster information has become an important source for demand estimations (Sodhi, Tang (2014)), and partly because media attention can affect future humanitarian organization donations (Eftekhar et al., 2017) and their consequent development.

Maghsoudi et al. (2021) analyzed the challenges faced by humanitarian operations during the 2017 Kermanshah earthquake and comments that the social media impact on humanitarian operations requires more academic attention. Fu and Lai (2021) argued that the ability of humanitarian organizations to use social media to gather information and coordinate with stakeholders is highly correlated with their disaster reduction performances. Ghadge (2023) argued that the application of social media can fully leverage the flexibility of humanitarian logistics and proposes a post-disaster information management method that integrates search engines, social media, drones, and artificial intelligence.

Some research has recognized the potential harm social media abuse can have on humanitarian logistics, mainly caused by factors such as rumors on social media and unequal attention. Based on their work experience in the crisis response arena, Tran et al. (2020) concluded that large amounts of inaccurate media information can cause potential humanitarian operational crises and that misinformation synthesis can adversely affect people’s perceptions of harm. Gürer et al. (2023) argued that large amounts of unstructured media information can lead to many humanitarian organizations and individuals blindly flooding into celebrity disaster areas and causing congestion and chaos.

There is a relatively rich body of research in academia on rumors and misinformation on social media after disasters, including studies on the mechanisms of rumor propagation, methods for rumor monitoring, and control strategies (Mondal et al., 2018). Liu et al. (2014) developed a model of rumor retransmission on social media during disasters based on rumor theory and the elaboration likelihood model. They analyzed the process of rumor generation to resolution on social media after disasters, from the perspective of rumor mechanisms. Hunt et al. (2022) demonstrated the effectiveness of machine learning models in the governance of misinformation on social media after disasters by developing a machine learning framework.

Nevertheless, there is limited research on the focus of this paper—the negative impacts caused by inequal attention on social media. To the best of our knowledge, the closest work to the topic of this paper comes from Zheng et al. (2024). Through the analysis of panel data, they found that there is inequality in social media attention during disasters, economically underdeveloped areas are often ignored, leading to potential long-term social inequality. They demonstrate the important role of state media in addressing this inequality. However, that work focused on the possible long-term impacts of inequal social media attention and the role of the government, while our study focuses more on the unequal supply and distribution of humanitarian relief supplies caused by inequal attention.

In terms of research methods, studies on different stages of humanitarian logistics often employ varying approaches. For example, random programming models are used in the pre-selection phase (Hong et al. 2015, Hu et al., 2023), while post-disaster transportation and distribution place greater emphasis on information and systematization. During this stage, queueing network methods(Ozen and Krishnamurthy, 2022) and blockchain technology are widely applied (Dubey et al., 2020).

In addition, system dynamics is also a suitable technique for studying complex, volatile operations components and is well-suited for humanitarian logistics distribution (Behl and Dutta, 2019). System dynamics is particularly suitable for predicting and simulating supply chains due to the following characteristics: a) it predicts and observes the overall behavior of the system simultaneously (Arboleda et al. 2007); b) it includes delays and feedback structures (Cannella et al., 2018); c) it constructs positive and negative feedback loops through causal relationships (Khanmohammadi et al. 2018). Humanitarian logistics, as a supply chain model in a specific context, is equally suitable for study using system dynamics.

Cannella et al. (2018) used an SD-based approach to address a disaster inventory management problem, finding that resource demand miscalculations can impact supply chain performance. Diedrichs et al. (2016) applied an SD simulation approach to study communications during humanitarian operations, concluding that communication quality is a key component in good storage practices and the reduction of material convergence and shortages. To provide basic guidance in disasters Mishra and Sharma (2020) employed an SD model to simulate social welfare supply chains. One of the first and most meaningful research humanitarian logistics system dynamics projects is Kunz et al. (2014), who used an SD model to measure the impact of prepositioned goods on humanitarian response activities, finding that although inventory prepositioning reduces inventory build-up, it also increases overall expected costs. Giedelmann-L et al. (2022) proposed an SD model to compare centralized and decentralized supply chain configurations and evaluate the perishable product distribution capabilities of different humanitarian food supply chain configurations.

The above studies demonstrate that SD is highly applicable in humanitarian supply chain research. However, they do not sufficiently consider the impact of social media on humanitarian supply chains and distribution outcomes. Therefore, the main difference between this paper and the aforementioned studies is the construction of a media attention subsystem, which is used to examine how changes in various elements of media public opinion influence the distribution of humanitarian relief goods.

Overall, some attention has been paid to the challenges faced by humanitarian organizations when using social media information, but there is no relevant research on uneven social media-induced humanitarian logistics distribution. Therefore, to address this gap, taking the 2022 Luding earthquake in China as an example, this paper uses system dynamics modeling and simulation to answer the following research questions.

-

a.

What is the celebrity disaster area effect, and how is it manifested in specific disaster events?

-

b.

How to measure the severity of the celebrity disaster area effect?

-

c.

How can the impacts of celebrity disaster area effects be reduced or eliminated?

Case study

This section introduces basic information on the 2022 Luding earthquake, the humanitarian assistance situation after the earthquake, and the reasons for choosing this disaster event as a case study.

Case study of a disaster and relief operations

An M6.8 earthquake occurred in Luding County, Sichuan Province, China, at 12:52 PM on September 5, 2022. The epicenter was 29.59°N, 102.08°E, and the source depth was 16 km (China Earthquake Network Center) (Wang et al., 2023). This earthquake resulted in 93 deaths, 424 injuries, 24 missing, and the damage or destruction of 13,000 homes and other infrastructure. It was the largest earthquake to strike the province since 2017 (Reuters, 2022). The seismic intensity map is shown in Fig. 1.

The 2022 Luding earthquake attracted significant social media attention, with the earthquake and related topics taking first place on Sina Weibo’s (the Chinese equivalent of Twitter) hot search for over 48 h and a massive increase in the Baidu search index (the Chinese equivalent of Google).

As shown in Fig. 1, the 2022 Luding earthquake impacted many locations over a wide area. The areas near the epicenter, including Luding, Shimian, Kangding, and Hanyuan, all experienced varying degrees of impact. However, because the epicenter was in Luding, the event was named the “Luding Earthquake”. As a result, most social media attention was focused on this specific disaster area, which resulted in a celebrity disaster area effect.

Luding earthquake humanitarian logistics

The social media attention to the 2022 Luding earthquake and the associated public opinion sparked public enthusiasm for donations. A statement released by the Sichuan Provincial Government in China stated that over 1.6 billion CNY was received in humanitarian donations from businesses and individuals, of which 140 million CNY was used to purchase food, drinking water, tents, and other disaster relief goods for the disaster area. The remaining 1.46 billion CNY was to be fully used for the post-disaster reconstruction in October 2022. Some caring enterprises and individuals also directly transported materials to the disaster area for distribution rather than donating them to governmental organizations (GOs) or NGOs.

The seismic intensity map in Fig. 1 shows that the most severely affected areas were Luding and Shimian and most areas in Hanyuan and Kangding. However, through interviews with GO and NGO leaders, we learned that material demand saturation in the celebrity earthquake disaster area, Luding was reached one week after the earthquake. Regardless, NGOs and individuals continued to transport large amounts of unnecessary food and other materials to Luding, which resulted in significant waste. Some of these materials were donated by people who had been influenced by social media and others were distributed in the Luding celebrity disaster area by NGOs wanting to gain media attention. However, in the other earthquake-affected areas, such as Shimian County, Hanyuan County, and Kangding, there were unmet material disaster victim needs, such as cotton clothes and quilts (The earthquake occurred in a high-altitude area in southwestern China, where the temperature was relatively low).

Methods

This study primarily uses system dynamics methods for model development and simulation analysis, with the software Vensim PLE version 10.2.2 employed for the analysis.

SD model development

System dynamics (SD), a pseudo-continuous modeling and simulation approach, has been widely applied to holistically analyze complex, interdependent, nonlinear systems (Arboleda et al., 2007). As the SD modeling strength is its ability to forecast system behaviors beyond the problem symptoms, it has been widely employed to model humanitarian logistics (Diedrichs et al., 2016; Kunz et al., 2014; Giedelmann et al., 2022) and evaluate the policy effects on systems (Park et al., 2009).

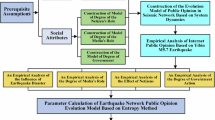

Empirical SD research comprises four consecutive steps (Lu et al., 2023) (Fig. 2): 1) systems analysis; 2) causal loop diagram (CLD) construction; 3) stock and flow diagram (SFD) creation; and 4) a simulated system analysis.

System analysis

Environmental constraints regulate system behavior and system construction. Before describing the humanitarian supply system structure, the system context needs to be further explored. As humanitarian logistics under the control of “media attention” is a complex process that has multiple links; materials procurement, collection, transportation, and distribution; it is necessary to balance the supply and the demand under resource, time, information, and transportation constraints. Therefore, we need to first analyze the system structure and functions.

The humanitarian logistics system can be divided into three subsystems based on the main system’s function and element characteristics: demand, supplement, and media attention. The demand subsystem includes first estimating the affected population based on disaster severity and population density and then estimating the relief goods demand. The supplement subsystem is a complete process from the receipt of the goods to the final distribution to the victims, which involves relief goods acquisition, procurement, transportation, storage, sorting, and distribution (Lu and Wang, 2023). The media attention subsystem depicts the evolutionary media attention process and its possible impact on materials distribution. The system framework is shown in Fig. 3.

Building the causal loop diagram (CLD)

The first step is to interpret the development community by drawing a causal loop diagram or “system map”. CLD depicts the important variables and the causal links between them (Sterman, 2002). For our purposes, the variables are actor behavior, relationships between the actors, system conditions or states, and interventions that can cause system changes (Blair et al., 2021).

The high-level causal loop diagram in Fig. 4 shows the leading humanitarian logistics feedback loops and the impact of certain parameters, such as earthquake magnitude and public opinion attention. The CLD illustrates the three system dynamics humanitarian logistic model dimensions; media attention, supplement, and demand; and describes the feedback between the model components.

When the variable values change, the CLD reflects the reinforcement and balancing effects occurring in the system, that is, a change in an initial variable value results in a change in the other variables that strengthen the initial variable’s value after a certain time. This feedback loop is self-reinforcing, which is identified with an “R” in the CLD. However, conversely, when a response in the other variables in the loop causes the initial variable’s original effect to decrease, this decreases the system’s changes. This loop is called a balancing loop and is identified with a “B” in the CLD.

The CLD shown in Fig. 4 has two balancing loops and two self-reinforcing loops. The self-reinforcing loops are when both media reports and social media discussions promote increased public opinion attention, which increases the number of media reports and social media discussions. One of the balancing loops is when the number of government news reports increases government engagement, which in turn, increases public satisfaction with the government, decreases public opinion attention, and reduces the quantity of government news. Another balancing loop is when public opinion attention promotes humanitarian relief goods donations, which increases the relief goods inventory, reduces the demand for relief goods, and finally reduces the public opinion attention.

The model, which we develop from the humanitarian relief goods supplement perspective, comprises several variables and constants that holistically characterize the system’s behavior. The model boundaries are set so that the model incorporates media attention by considering the key variables under their control. Based on the model boundaries, we classify the model variables into three main groups: endogenous, exogenous, and excluded, the details for which are shown in the Appendix. The endogenous variables influence the system’s behavior and are also influenced by it and the exogenous variables influence the system’s behavior but cannot be influenced by it; however, because the effects of the excluded variables on the model are negligible, this is not considered.

Developing the stock and flow diagram (SFD)

The SFD distinguishes the nature of each variable and describes the nature of the system elements and the overall framework. Intuitive symbols depict the logical relationships between the elements and explore the system’s feedback and control rules (Xu et al., 2016). Based on the CLD, the resulting SFD is shown in Fig. 5.

The main role of the humanitarian supply chain is to convert donations into living materials and deliver them to the disaster areas (Zhang and Chen, 2016). The living materials can be divided into cumulative and non-cumulative materials, which have different system structures in the SD model development. Cumulative materials are materials that the demand for accumulates over time, such as clothes and tents; however, the daily demand for non-cumulative materials, such as food and drinking water, is a fixed value determined by the disaster victims. Even if the demand for one day is not met, the demand for that day does not accumulate until the next day.

Post-disaster relief goods transportation decision-makers must determine the types of disaster relief supplies needed and the demand quantity (Naji-Azimi et al., 2012). From interviews with the NGOs involved in the humanitarian supply transportation during the Luding earthquake, we learned that the unevenly distributed supplies are mainly non-cumulative. When large amounts of unnecessary food, drinking water, and toilet paper were transported to Luding, the food was discarded after spoiling, and most other materials were directly stacked in the resettlement area without any management. Therefore, the humanitarian relief goods studied in this paper refer mainly to the non-cumulative relief goods, the demand for which is a linear function determined by the victims.

Compared to the relief goods surpluses in Luding, the surrounding disaster areas, such as Shimian, Hanyuan, and Kangding, had different degrees of relief goods shortages. Therefore, we take these four regions as examples to develop the humanitarian material transportation and distribution SD model.

In the media attention subsystem, the number of government news reports refers to the total number of news reports related to the Luding earthquake on the official Chinese government department emergency response websites at all levels. The time series data for the number of media reports on the Luding earthquake was obtained through a Baidu and Bing search, and the social media discussion value was obtained based on the number of posts related to the Luding earthquake in the Baidu Post Bar and the number of related microblogs on Sina Weibo.

Data collection and parameter settings

Both partial and full model calibration require time series data on several variables (Goncalves et al., 2023). Precise time series data are required to develop an effective humanitarian relief goods supply SD model and to test the accuracy of the model parameters. The required data were:

-

(i)

The number of government news reports, media reports, social media discussions, and other media attention subsystem data;

-

(ii)

The humanitarian donations received;

-

(iii)

The population density in each disaster area and the distance to the epicenter; and,

-

(iv)

The relief goods resumption rate.

To obtain the data for (i) to calculate Public opinion attention, We conducted a statistical analysis of the number of reports related to the Luding earthquake in four affected areas within two weeks after the earthquake, as retrieved from Baidu and Bing search results. Additionally, we used web scraping to collect data on relevant government official reports, user posts, comments, and reposts on Sina Weibo. To obtain the data for (ii) and (iv), we interviewed the person in charge of the Sichuan Charity Federation in China, which is an official government-organized NGO (GONGO) and public affairs organization created by the Sichuan Provincial Department of Civil Affairs that is actively involved in social welfare (Lu and Xu, 2015; Cumming, 2010). The Sichuan Charity Federation received 1.46 billion CNY in donations from enterprises and the public in the two weeks following the 2022 Luding earthquake, which accounted for over 90% of the total donations. We obtained time series data on the amount of donations received from the head of the organization for item (ii) and used the living material subsidy standard (70 CNY per person per day) issued by the Charity Association for the Luding earthquake victims as the relief goods consumption rate for item (iv). The data for item (iii) were taken from the 2022 Sichuan Provincial Statistical Yearbook.

Other relevant data for the correlation equation and exogenous variable values in the SD model were collected from previous research. The model took 00:00 on September 5, 2021, as the simulation starting point, with each simulation step being one day. The initial values after preprocessing for the external variables in this model are shown in Table 1. The data for variables 1–6 are sourced from the China Earthquake Networks Center (URL: news.ceic.ac.cn, accessed on January 1, 2023), while the data for variables 7–10 are obtained from the 2023 Sichuan Province Statistical Yearbook.

Model validation and testing

Several testing methods have been proposed to evaluate the validity of SD models (Sterman, 2002; Shreckengost, 1985). This section discusses the tests most used in SD literature (Deuten, 2017; Kapourani and Kapmeier, 2017) and presents the proposed model’s application results.

The key model test assumptions were as follows.

-

1.

Disaster events are sudden, and at the beginning of the simulation, the humanitarian inventory and public opinion attention value is 0.

-

2.

There is no unified coordination between emergency departments on how humanitarian supplies are distributed to different regions, and the distribution results are highly influenced by public opinion attention.

-

3.

All victims affected by disasters, the displaced, and the resettled require daily material subsidies to ensure their survival needs.

Behavior reproduction test

We used model calibration to test the ability of the model to replicate observed behavior by comparing the simulated behavior of the model against available time series data from real counterparts (Forrester, 1979; Homer, 2012). Model calibration drives real-time series input data through the model structure and compares the simulated output behavior with the associated time series data for the output, which is an essential step in SD model empirical analyses. In this study, the simulated results, in which the relief goods supply speed in each region was taken as the core index, were compared with the reported results from the websites of the Luding, Shimian, Hanyuan, and Kangding people’s governments.

The time series data on the humanitarian goods received by the governments in the four disaster areas are shown in Humanitarian goods received.xlsx. In the released government data, a portion of the humanitarian goods received by each region were targeted supplies donated to other disaster areas; therefore, we made certain adjustments to the data released by the government and obtained the results in Humanitarian goods received.xlsx.

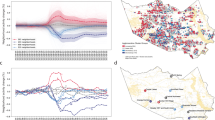

Figure 6 shows that the simulated results and the reported result curve trends in the four disaster areas were roughly the same. It should be noted that the simulation result is the time humanitarian goods arrive at the disaster area, including transportation delays, while the reported result is the time donations are received. Therefore, we advanced the simulation result by two days to compare it with the reported result. The results show that the simulation results are consistent with the actual results and within an acceptable error range.

Extreme conditions test

To determine whether the model behaved properly when extreme values (e.g., zero or infinity) were assigned to a given variable, an extreme condition test was conducted to evaluate the model’s capability in extreme conditions (Shreckengost, 1985). Extreme condition tests can be implemented by directly inspecting the model equations or by running a simulation model (Sterman, 1994). In this case, we implemented both approaches.

Figures 7 and 8 show the inventory and consumption of relief goods in Shimian when we respectively set the magnitude to zero and infinity. The results in Fig. 7 show that when the magnitude is 0, there are no disaster victims and no media attention; therefore, both inventory and consumption are 0, which is consistent with the actual situation. The results in Fig. 8 show that when the magnitude is infinite, all residents are transformed into disaster victims; however, as the quantity of humanitarian goods is limited, the inventory and consumption curves are completely consistent. This indicates that once supplies arrive, they are consumed, and the demand gap is huge, which is consistent with the actual situation.

In summary, the model developed in this article passed the extreme condition testing.

Results

The celebrity disaster area in the Luding earthquake

Figure 9 shows the humanitarian relief goods consumption in various regions under the influence of the public opinion levels during the Luding earthquake. The red dashed line represents the rated consumption in each disaster area when there are sufficient supplies.

Four days after the earthquake, humanitarian relief goods began to arrive in the disaster area, and except for the celebrity disaster area, Luding, the other disaster areas had varying degrees of material shortages. The rated consumption in Hanyuan was about 6.16 million per day; however, the daily arrival of humanitarian relief goods was far from this value. Therefore, the different public opinion attention caused a significant celebrity disaster area effect in the Luding earthquake. (Note that because emergency supplies for the 3–4 days after a disaster are generally provided by the government to ensure the basic survival of disaster victims, the shortage of supplies in the first four days due to information and transportation delays is not considered in this study).

Measurement of the celebrity disaster area effect

As alleviating human suffering is the main goal of post-disaster humanitarian logistics, it is generally agreed that measuring the supply and distribution effectiveness of humanitarian logistics using the deprivation costs concept is particularly promising. Therefore, we introduce the deprivation cost concept to measure the severity of the celebrity disaster area effect.

Deprivation cost is defined as “the economic value of the human suffering caused by lack of access to a good or service” (Holguín-Veras et al., 2013). Wang et al. (2017) summarize the deprivation function for emergency supplies in humanitarian logistics, such as food, as Eq.(1), the function graph shown in Fig. 10, with the upper deprivation limit being 9.75.

The introduction of the deprivation levels allows for the development of the humanitarian relief goods distribution measurement subsystem shown in Fig. 11. We use the value “1-(relief goods consumption/relief goods demand)” to represent the proportion of disaster victims who lack relief goods on that day, accumulate the proportion of victims who lack relief goods 14 days after the disaster to obtain the deprivation time, and then use the deprivation function to calculate the deprivation level and measure the effectiveness of the relief goods supply.

Figure 12 shows the simulation results for the deprivation levels in each disaster area. Because of the impact of the celebrity disaster area effect, the deprivation levels in Luding and Shimian are both below 0.1. Kangding has a slight shortage of relief goods, with the deprivation level around 0.4, but Hanyuan has a serious shortage of relief goods, with the deprivation level reaching 5.25. As the simulation results are consistent with our assumptions, we believe that the subsystem has good measurement capabilities to assess the celebrity disaster area effect.

Alleviate the celebrity disaster area effect

To alleviate the celebrity disaster area effect, the following are two obvious goals: first, to align the level of Public opinion attention with the required level of humanitarian donations for the disaster, avoiding excessive attention and insufficient attention; second, to balance the Public opinion attention across all affected areas on actual demand, preventing the celebrity disaster area from receiving disproportionate attention while surrounding areas are neglected.

Building on existing research, this paper explores two methods of public opinion guidance: increasing official news coverage or limiting the flow of media news and social media discussions. To increase official news coverage, we set a step function with a 25% increase in the speed of government news reports starting on the second day when disaster-related news began to surge, which returned to normal levels after three days. For limiting media traffic, we directly reduced media coverage and social media discussions to 75% of their original levels. The effects of these two adjustments on the Public opinion attention levels in the four disaster areas are shown in Fig. 13.

We can observe clear differences between the two methods. Government reporting can guide public opinion towards actual needs, reducing the attention on celebrity disaster areas while increasing attention to other disaster areas. However, frequent government reports also lead to a significant rise in media coverage and social media discussions, with this impact occurring more rapidly than the adjustment in the balance of attention towards the disaster areas. Government reports quickly generate a lot of media news, sparking hot topics, but guiding attention towards the needs of the disaster areas usually requires more time. As a result, under this guidance method, the attention in the four disaster areas will all experience a surge in the early stages, with the attention on Luding only dropping below the current level in the later stages. In contrast, the effect of limiting media traffic is relatively simple, with attention to the four disaster areas maintaining the same trend, but at a reduced level. Moreover, the decrease in media attention leads to a reduction in social media discussions, which further results in an overall decrease in the attention on the event. Therefore, when media traffic is restricted to 75% of its original level, the actual public attention decreases even more, by approximately 30–40%.

This result is an important complement to the findings of Zheng et al. (2024), which suggest that government official reports can indeed address the inequality of media attention in post-disaster situations. However, it also highlights that such reports may lead to an overall surge in public opinion levels, resulting in more severe resource waste.

Due to the inconsistencies between the public opinion attention and the actual relief goods needs in each disaster area, we expect to guide the public opinion attention based on the actual demand in the previous day, so that the proportion of social media attention in each disaster area is consistent with the material needs, which can effectively reduce the celebrity disaster area effect and achieve a balanced distribution of humanitarian relief goods. We use the established deprivation level subsystem to measure the effects of the adjustments.

Because of the delays in receiving and publishing information on social media, we add a one day information delay to the guidance results. Based on the different guidance levels, we respectively set the upper limits of the daily changes in public opinion attention to 10%, 50%, 100%, and 200%. The adjusted deprivation levels in the disaster area are shown in Fig. 14.

It can be seen that guiding public opinion attention based on the actual demand in the disaster areas has a very good effect on the humanitarian relief goods distribution and shows that the stronger the guidance, the lower the level of deprivation in each disaster area, and the closer the distribution results are to actual needs. Considering the guiding cost of media attention and the utilization of social resources, we believe that it is more appropriate to guide and control the level of attention with a daily change rate of 50%.

Finally, following this method and the 50% guidance change rate level, to determine the best media attention for earthquakes of different magnitudes, we simulate the overall public opinion scale of the 2022 Luding earthquake by increasing and decreasing the overall media attention.

As shown in Fig. 15, the current media attention curve and the 150% and 300% curves overlap, indicating that there was excessive media attention on the 2022 Luding earthquake. Increasing the media attention levels can no longer improve the effectiveness of the humanitarian relief goods supply. When we compare the media attention 50%, 60%, 70%, and 80% curves with the current curve, we see that when the media attention level is 70% of the current level, the humanitarian supply is relatively good as the overall deprivation level in the disaster area does not exceed 1, the living standards of the disaster victims are relatively high, and unnecessary waste from donations and excessive public resource occupation are avoided.

Conclusion

This paper systematically explored the celebrity disaster area effect resulting from excess public opinion attention on the uneven distribution of post-disaster humanitarian relief goods in the core disaster areas. The celebrity disaster area effect can be attributed to various factors, such as disordered online media reporting, the overly narrow naming scope of disaster events, and the humanitarian logistics bandwagon effect. This celebrity disaster area effect can lead to resource wastage in the celebrity disaster areas, resource shortages in the surrounding areas, disaster management chaos, and inefficient humanitarian actions. We measured the celebrity disaster area effect using deprivation costs, discussed the effects of different public opinion guidance methods and explored methods to alleviate this effect using sensitivity analyses to determine the appropriate levels of media attention for disaster relief. The following conclusions were made based on the results. Items (1), (2) and (3) correspond to questions a, b and c raised in Section 2 of this study.

-

1.

We simulated the humanitarian relief goods distribution during the Luding post-earthquake period and discovered that there was a serious celebrity disaster area effect. Except for the celebrity disaster area in Luding, the surrounding disaster areas had varying degrees of relief goods shortages. The relief goods shortage in Hanyuan is the most severe, with the daily supply of humanitarian relief goods in the area failing to meet the demand.

-

2.

By incorporating deprivation costs into the SD model, the extent of inequality in humanitarian relief goods distribution can be effectively measured.

-

3.

The 2022 Luding earthquake case study reveals that with public opinion attention guidance intensity of around 50% per day and media attention of around 70% of current levels, the celebrity disaster area effect can be effectively alleviated. In terms of guiding public opinion, increasing official news coverage can address the inequality in attention, but they may also lead to a surge in overall public opinion levels. On the other hand, limiting media traffic only reduces the overall attention level. The optimal guidance method should combine both approaches.

Based on the simulation results, some policy recommendations are given to provide a reference for humanitarian organizations participating in humanitarian relief goods supply in similar future natural disasters.

-

1.

To avoid the “celebrity disaster area effect” caused by unequal media attention, humanitarian supply chain organizations should scientifically and effectively conduct demand assessments, have a detailed understanding of the disaster area information, and avoid excessive reliance on social media for relief goods distribution.

-

2.

Consider naming disaster events to indicate the broader disaster area scope to avoid creating celebrity disaster areas, which would direct media and public attention to the entire affected region, rather than specific locations. Additionally, the media should improve their disaster reporting mechanism by making their reports more objective and comprehensive, rather than focusing solely on the celebrity disaster areas.

-

3.

To ensure that disaster relief donations are appropriately directed, foundations should ensure that corporate and public donations are channeled through specific pathways that are well-informed about the actual situation on the ground. The government needs to promptly disseminate information about the disaster and provide comprehensive timely updates about the conditions in the affected areas and the status of received donations. This would allow the media and the public to stay dynamically informed about the relief efforts and prevent the over-allocation of resources to one area. Additionally, the government should ensure a safety net for the non-celebrity disaster areas inadequately covered by social donations to ensure the livelihood of these victims.

To the best of our knowledge, this research was the first to apply an SD modeling evaluation approach to the uneven distribution of relief goods resulting from public opinion attention on humanitarian logistics. However, as this was exploratory research, there were several limitations. First, different disaster relief supplies have different demand curves and deprivation functions. To simplify the simulation model, we uniformly measured them in monetary terms and used local post-disaster subsidy standards as the daily demand, which may have led to some errors. Future research could use different types of materials for the simulation. Second, disaster relief goods supply varies depending on the event, such as floods, earthquakes, and hurricanes, and the associated secondary disasters. Further research could, therefore, include different disaster relief scenarios to optimize and verify the model. Third, there are social and cultural factors behind humanitarian relief and there are differences between countries. Whether a model based on Chinese humanitarian logistics could be applied to other countries and regions remains to be seen. In the future, country-by-country comparative research based on this model could be conducted to provide more general policy recommendations.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The datasets Humanitarian goods received and The number of government news reports, media reports, social media discussions have been shared.

References

Anadolu Agency. (2023, February 17). “Türkiye—One Heart”: 6 billion dollars were collected for the victims of the earthquake”. Turan News. Anadolu Agency. 17 February 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.”

Arboleda CA, Abraham DM, Lubitz R (2007) Simulation as a tool to assess the vulnerability of the operation of a health care facility. J Perform Constr Facil 21(4):302–312. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0887-3828(2007)21:4(302)

Bakillah M, Li RY, Liang SH (2015) Geo-located community detection in Twitter with enhanced fast-greedy optimization of modularity: the case study of typhoon Haiyan. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 29(2):258–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/13658816.2014.964247

Behl A, Dutta P (2019) Humanitarian supply chain management: a thematic literature review and future directions of research. Ann Oper Res 283(1):1001–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-018-2806-2

Blair C, Gralla E, Wetmore F, Goentzel J, Peters M (2021) A systems framework for international development: the data‐layered causal loop diagram. Prod Oper Manag 30(12):4374–4395. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13492

Cannella S, Dominguez R, Framinan JM, & Bruccoleri M (2018) Demand sharing inaccuracies in supply chains: a simulation study. Complexity, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1092716

Chomilier B, Samii R, Van Wassenhove LN (2003) The central role of supply chain management at IFRC. Force Migr Rev 18(2):15–16

Crooks A, Croitoru A, Stefanidis A, Radzikowski J (2013) Earthquake: Twitter as a distributed sensor system. Trans GIS 17(1):124–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9671.2012.01359.x

Cumming LS (2010) GONGOs in Anheier. In H.K. Anheier and S. Toepler (eds) International Encyclopedia of Civil Society. Springer, New York, NY, pp 779–783. ISBN: 978-0-387-93994-0

Davies RB, Klasen S (2019) Darlings and orphans: Interactions across donors in international aid. Scand J Econ 121(1):243–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12261

Deuten S (2017) Taking care of the right pressure: a dynamic theory of health care work pressure, nurses well-being and patient satisfaction. https://theses.ubn.ru.nl/handle/123456789/6876

Diedrichs DR, Phelps K, Isihara PA (2016) Quantifying communication effects in disaster response logistics: a multiple network system dynamics model. J Humanit Logist Supply Chain Manag 6(1):24–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHLSCM-09-2014-0031

Dignan L (2005) Tricky currents; tsunami relief is a challenge when supply chains are blocked by cows and roads don’t exist. Baseline 1(39):30. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujibm.2014.020602

Dubey R, Gunasekaran A, Bryde DJ, Dwivedi YK, Papadopoulos T (2020) Blockchain technology for enhancing swift trust, collaboration and resilience within a humanitarian supply chain setting. Int J Prod Res 58(11):3381–3398. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1722860

Eftekhar M, Li H, Van Wassenhove LN, Webster S (2017) The role of media exposure on coordination in the humanitarian setting. Prod Oper Manag 26(5):802–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12669

EM-DAT (2024) The International Disaster Database. Available online at: http://www.emdat.be/ (accessed January 1, 2024)

Forrester JW (1979) An alternative approach to economic policy: macro behavior from microstructure. Econ Issues Eighties 103:80–108

France 24 (2023) “UN admits aid failure for Syria as quake toll hits 33,000”. France 24. 12 February 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023

Fu JS, Lai CH (2021) Determinants of organizational performance in disaster risk reduction: A preliminary study of global humanitarian NGOs. J Contingencies Crisis Manag 29(3):232–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12346

Ghadge A (2023) ICT-enabled approach for humanitarian disaster management: a systems perspective. Int J Logist Manag 34(6):1543–1565. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-11-2021-0532

Giedelmann-L N, Guerrero WJ, Solano-Charris EL (2022) System dynamics approach for food inventory policy assessment in a humanitarian supply chain. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 81:103286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103286

Gonçalves P, Ferrari P, Crivelli L, Albanese E (2023) Model‐informed health system reorganization during emergencies. Prod Oper Manag 32(5):1323–1344. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13710

Guha-Sapir D, Hoyois P, Wallemacq P, & Below R (2017) Annual Disaster Statistical Review 2016. The numbers and trends, 1–91

Gürer D, Hubbard J, Bohon W (2023) Science on social media. Commun Earth Environ 4(1):148. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00810-9

Heaslip G, Vaillancourt A, Tatham P, Kovács G, Blackman D, Henry MC (2019) Supply chain and logistics competencies in humanitarian aid. Disasters 43(3):686–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12361

Holguín-Veras J, Pérez N, Jaller M, Van Wassenhove LN, Aros-Vera F (2013) On the appropriate objective function for post-disaster humanitarian logistics models. J Oper Manag 31(5):262–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2013.06.002

Homer JB (2012) Partial‐model testing as a validation tool for system dynamics (1983). Syst Dyn Rev 28(3):281–294. https://doi.org/10.1002/sdr.1478

Hong X, Lejeune MA, Noyan N (2015) Stochastic network design for disaster preparedness. IIE Trans 47(4):329–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/0740817X.2014.919044

Hosseini SA, Mohammadi L, Amirbagheri K, de la Fuente A (2023) Assessing humanitarian supply chain operations in the aftermath of the Kermanshah earthquake. J Humanit Logist Supply Chain Manag 13(4):378–398. https://doi.org/10.1108/jhlscm-01-2022-0001

Hu S, Hu Q, Tao S, Dong ZS (2023) A multi-stage stochastic programming approach for pre-positioning of relief supplies considering returns. Socio-Econ Plan Sci 88:101617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2023.101617

Hunt K, Agarwal P, Zhuang J (2022) Monitoring misinformation on Twitter during crisis events: a machine learning approach. Risk Anal 42(8):1728–1748

Jones R, Cloud DS, Kalin S (2023) “Turkey, Syria Mourn Losses as Earthquake Death Toll Climbs Above 24,000”. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 February 2023

Kapourani EE, & Kapmeier F (2017) “ Boom without limits?”–An analysis of the Stuttgart real estate market. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference of the System Dynamics Society and 60th Anniversary of System Dynamics Celebration, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA Conference (pp 1-37). System Dynamics Society

Khanmohammadi S, Farahmand H, Kashani H (2018) A system dynamics approach to the seismic resilience enhancement of hospitals. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 31:220–233

Kunz N, Reiner G, Gold S (2014) Investing in disaster management capabilities versus pre-positioning inventory: a new approach to disaster preparedness. Int J Prod Econ 157:261–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.11.002

Li H, Sakamoto Y (2015) Re-Tweet count matters: social influences on sharing of disaster-related tweets. J Homel Security Emerg Manag 12:No. 3. https://doi.org/10.1515/jhsem-2014-0081

Liu F, Burton-Jones A, Xu D (2014) Rumors on social media in disasters: Extending transmission to retransmission

Lu Y, Wang Y (2023) Dynamic analysis of NGO emergency relief goods supply: 2020 Hubei COVID-19 as a case. Front Public Health 11:1037846. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1037846

Lu Y, Xu J (2015) NGO collaboration in community post‐disaster reconstruction: field research following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. Disasters 39(2):258–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12098

Lu Y, Wang Y, Zhang L (2023) System dynamic modeling of the NGO post-disaster relief contribution in the 2021 Henan flood in China. Int J disaster risk Reduct 89:103626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103626

Maghsoudi A, Moshtari M (2021) Challenges in disaster relief operations: evidence from the 2017 Kermanshah earthquake. J Humanit Logist Supply Chain Manag 11(1):107–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHLSCM-08-2019-0054

Mishra V, Sharma MG (2020) Understanding humanitarian supply chain through causal modelling. South Asian J Bus Manag Cases 9(3):317–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277977920958084

Mondal T, Pramanik P, Bhattacharya I, Boral N, Ghosh S (2018) Analysis and early detection of rumors in a post disaster scenario. Inf Syst Front 20:961–979

Murray S (2005) How to deliver on the promises: Humanitarian agencies are learning lessons from business in bringing essential supplies to regions hit by the tsunami. Financial 9:1–7

Naji-Azimi Z, Renaud J, Ruiz A, Salari M (2012) A covering tour approach to the location of satellite distribution centers to supply humanitarian aid. Eur J Oper Res 222(3):596–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2012.05.001

Ozen M, Krishnamurthy A (2022) G-network models to support planning for disaster relief distribution. Int J Prod Res 60(5):1621–1632. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1867920

Park M, Ji SH, Lee HS, Kim W (2009) Strategies for design-build in Korea using system dynamics modeling. J Constr Eng Manag 135(11):1125–1137. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000095

Prakash C, Roy V, Charan P (2022) Mitigating interorganizational conflicts in humanitarian logistics collaboration: the roles of contractual agreements, trust and post-disaster environmental uncertainty phases. Int J Logist Manag 33(1):28–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-06-2021-0318

Reuters (2022) “Earthquake in China’s Sichuan kills more than 30, shakes provincial capital”. Reuters. 5 September 2022. Archived from the original on 5 September 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2022

Shreckengost RC (1985) Dynamic simulation models: How valid are they? Self-Rep. Methods Estimating Drug Use Curr Chall Validity Natl Inst Drug Abus Res Monogr 57:63–70

Sodhi MS, Tang CS (2014) Buttressing supply chains against floods in Asia for humanitarian relief and economic recovery. Prod Oper Manag 23(6):938–950. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12111

Sterman J (2002) System Dynamics: systems thinking and modeling for a complex world. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Engineering Systems Division. http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/102741

Sterman JD (1994) Learning in and about complex systems. Syst Dyn Rev 10(2‐3):291–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/sdr.4260100214

Swaminathan JM (2018) Big data analytics for rapid, impactful, sustained, and efficient (RISE) humanitarian operations. Prod Oper Manag 27(9):1696–1700. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12840

Tran T, Valecha R, Rad P, Rao HR (2020) An investigation of misinformation harms related to social media during humanitarian crises. In Secure Knowledge Management In Artificial Intelligence Era: 8th International Conference, SKM 2019, Goa, India, December 21–22, 2019, Proceedings 8 (pp 167-181). Springer Singapore

Urquhart A, Girling F, Nelson-Pollard S, & Mason E (2022) Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2022. Development Initiatives

Vieweg SE (2012) Situational Awareness in Mass Emergency: A Behavioral and Linguistic Analysis of Microblogged Communications, PhD Thesis, University of Colorado at Boulder

Wang W, Li Y, Zhang Z, Xin D, He Z, Zhang W, Chen X (2023) Rapid estimation of disaster losses for the M 6.8 Luding earthquake on September 5, 2022. Sci China Earth Sci 66(6):1334–1344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-022-1078-6

Wang X, Wang X, Liang L, Yue X, Van Wassenhove LN (2017) Estimation of deprivation level functions using a numerical rating scale. Prod Oper Manag 26(11):2137–2150. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12760

Xu J, Dai J, Rao R, Xie H, Lu Y (2016) Critical systems thinking on the inefficiency in post-earthquake relief: a practice in Longmen Shan fault area. Syst Pract Action Res 29:425–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-016-9374-7

Zhang YL, Chen L (2016) Emergency materials reserve of government for natural disasters. Nat Hazards 81:41–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-015-2065-3

Zheng L, Chen L, Long F, Liu J, Li L (2024) Reducing social media attention inequality in disasters: the role of official media during rainstorm disasters in China. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 15(3):388–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-024-00562-w

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 72274131), and the Civilization Mutual Learning and Global Governance Research Program of Sichuan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceptualized by Yuhang Wang, who also designed and developed the analytical models and drafted the manuscript. Liuyue Zhang contributed to data collection, processing, and the preparation of figures. Rui Li participated in refining the models and conducted language editing and proofreading. Yi Lu provided overall supervision, guided the research direction, and secured funding for the project. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statements

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This study utilized the following data sources: (1) 9·5 Luding Earthquake disaster data from the (publicly reported by government agencies and authorized media outlets), (2) anonymized donation statistics from official charitable platforms (no personal identifiers included), (3) socioeconomic data from the Sichuan Statistical Yearbook (publicly available government-published material), and (4) social media engagement metrics (total discussion volume related to the earthquake, excluding any textual content, user identities, or personal information). So, the informed consent was neither required nor sought.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Zhang, L., Li, R. et al. The celebrity disaster area effect: exploring the impact of social media on the distribution of humanitarian goods. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 463 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04722-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04722-1