Abstract

As the interaction between science and technology intensifies, the role of science in driving technological innovation has become increasingly significant. Enterprises, as key actors in market competition and innovation, can gain a substantial competitive advantage and contribute to industrial transformation by engaging in basic research. This study focuses on science-based enterprises, defining enterprises’ scientific capabilities in two dimensions: internal scientific capabilities and external scientific capabilities. Through a combination of empirical and simulation research, this study examines the mechanisms by which scientific capabilities influence innovation performance. The results demonstrate that internal scientific capabilities significantly enhance enterprise innovation, underlining the importance of engaging in basic research to foster scientific innovation performance. External scientific capabilities, particularly in terms of quantity, also contribute positively to innovation performance, emphasizing the value of industry-university-research collaborations and the effective absorption of scientific knowledge. Furthermore, scientific innovation intensity mediates the relationship between scientific capabilities and innovation performance, with science-based innovation acting as a bridge between scientific discoveries and technological advancement. While scientific research funding moderates the impact of internal scientific capabilities on innovation performance, it shows no significant moderating effect on external scientific capabilities. Based on these findings, the study proposes four pathways for enterprises to enhance innovation performance: independent innovation, collaborative R&D, scientific knowledge absorption, and technical iteration. This research advances both enterprise capability theory and technological innovation theory by addressing the gap in understanding how enterprises’ scientific capabilities influence innovation and providing actionable insights for the development of science-based enterprises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As emerging industries such as biopharmaceuticals, artificial intelligence, information and communication technology, and satellite internet continue to develop rapidly, an increasing number of enterprises are recognizing the importance of fundamental research for gaining competitive advantages (Shen et al. 2022). Many of these enterprises are actively participating in basic scientific research (Jong and Slavova 2014; Simeth and Lhuillery 2015). Given the high costs, long-term investment, and challenges associated with generating scientific knowledge, enterprise involvement in fundamental research has become an intriguing topic of academic interest (Liu et al. 2023). Within the context of science-based innovation, companies often voluntarily dedicate significant resources to fundamental research and disclose their scientific findings through numerous publications (Simeth and Lhuillery 2015). This trend is seen not only in large enterprises with independent research labs but also among numerous small and medium-sized tech firms that actively publish their scientific outcomes in academic journals (Åstebro et al. 2012). Notable enterprises such as Google, Apple, and Huawei have all contributed to this movement. Hicks (1995) found that some companies’ investments in fundamental research, along with their frequent publication of papers in scientific journals, resulted in contributions to science comparable to those of mid-sized universities (Hicks 1995). Scholars generally agree that in knowledge-intensive industries, scientific knowledge significantly impacts technological innovation. Science-based innovation accelerates the pace of technological progress and is considered a key factor in enhancing innovation efficiency (Sorenson and Fleming 2004). The pursuit of competitive advantage compels enterprises to increasingly participate in scientific research, giving rise to “science-based enterprises” (Miozzo and DiVito 2020). The internal creation of scientific knowledge and the absorption of external knowledge through collaboration have sparked growing interest in the exploration of enterprises’ scientific capabilities (Annapoornima and Soh 2006). Such scientific activities promote the creation and dissemination of knowledge, contribute to building academic reputations, foster engagement in broader knowledge networks, strengthen relationships with academic scientists, reduce the risks associated with technological innovation, and help integrate enterprises into the scientific community (Genin and Lévesque 2023).

However, there is a significant distinction between the scientific knowledge generated from basic research and technological innovation (Park and Kang 2009). The essence of scientific knowledge lies in exploring and understanding the fundamental laws of natural phenomena (Park and Suh 2013). It is often abstract and theoretical in nature, and the process of applying this knowledge to create new inventions, thereby generating technological knowledge, usually requires time and is fraught with uncertainty (Yang et al. 2024). Thus, successful scientific research does not necessarily lead to commercially valuable technological innovations. The transition from scientific knowledge to technological innovation involves highly complex dynamics, and successful basic research does not always result in successful technological breakthroughs (Xu et al. 2020). Enterprises’ participation in fundamental research does not always yield beneficial returns. The linear or pipeline model of knowledge flow from basic science to practical technology (Carpenter and Narin 1983), as well as the theory of co-evolution between science and technology (Meyer 2002), have been shown to have several limitations. As such, the question of how enterprises’ scientific capabilities can be translated into technological innovation performance becomes an area worthy of deeper investigation. Existing research primarily focuses on technological and product innovation (Herrera 2020), while studies specifically addressing scientific innovation remain relatively scarce.

The resource-based view and enterprise capability theory offers a suitable perspective for exploring this issue (Teece 2014a). Capabilities represent the critical skills and tacit knowledge that constitute a firm’s intellectual capital, emphasizing the enterprise’s ability to leverage various internal and external resources to gain a competitive advantage (Ma et al. 2021). Enterprises’ scientific capabilities, in this context, refer to the ability of firms to create, acquire, and absorb scientific knowledge by utilizing their internal intellectual resources and external scientific collaboration networks. Drawing on the work of Chen et al. (2007), we classify enterprises’ scientific capabilities into two dimensions: internal scientific capabilities and external scientific capabilities (Chen et al. 2007). Scientific discoveries generate technological ideas, laying the foundation for the development of new technologies and products within firms (Tijssen 2001). Scientific innovation intensity, often referred to as “science intensity” or “science linkage” or “science proximity,” indicates the degree to which a firm’s technological innovation relies on scientific knowledge (Van Looy et al. 2006). This study posits that scientific innovation intensity is a critical factor influencing the process by which enterprises cultivate scientific capabilities and translate them into technological innovation performance. Innovation rooted in science bridges the early stages of scientific research with the later stages of technological development, shortening the distance between the creation of scientific knowledge and its transformation into technological knowledge (Park and Suh 2013). However, given the limited attention this topic has received in academic research, further exploration and validation are necessary. For policymakers, enterprise participation in fundamental research is crucial to the formation and development of industries, as well as to the enhancement of regional and even national innovation systems (Vandaie 2022). Thus, providing effective research funding and support for these enterprises is a pressing issue that requires theoretical guidance.

Based on the above analysis, this study focuses on 204 publicly listed enterprises within the biopharmaceutical industry, which serves as an exemplary science-based sector (Marsili 2001). The development of new drugs heavily relies on breakthroughs in scientific research, and many biopharmaceutical enterprises actively engage in basic research, frequently publishing their findings in academic journals (Toole 2012). As such, selecting companies within this industry aligns well with the objectives of this study. This research develops a theoretical model to examine the relationship between enterprises’ scientific capabilities and technological innovation performance. The model incorporates scientific innovation intensity as an intermediary variable and research funding as a moderating variable. Using stepwise regression in an empirical study, we investigate how both internal and external scientific capabilities influence technological innovation performance and explore the underlying mechanisms. Recognizing the limitations of empirical research—particularly its inability to dynamically capture the transformation of scientific capabilities into technological innovation performance—we supplement this approach with simulation methods. Simulation allows for a more dynamic exploration, enriching and reinforcing the empirical findings of this study. Through this dual-method approach, we aim to provide a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms by which enterprises’ scientific capabilities contribute to technological innovation.

This study employs a mixed-method approach, combining empirical analysis and simulation, to explore the mechanisms through which enterprises’ scientific capabilities impact innovation performance. Theoretically, it enriches both enterprise capability theory and technological innovation theory, addressing the gap in academic research on enterprises’ scientific capabilities and clarifying its influence on technological innovation. Practically, the findings offer valuable insights for enterprises looking to enhance their technological development, while also providing guidance for policymakers in formulating strategies to support innovation-driven growth.

Theoretical foundation and literature review

Enterprise capability theory

With the continuous evolution of the resource-based view (RBV), enterprise capability theory emerged, encompassing concepts such as core competencies and dynamic capabilities (Ma et al. 2021). Enterprise capability theory can be divided into two main schools: the resource-based school and the capability-based school. The resource-based school posits that enterprises gain competitive advantage through heterogeneous, hard-to-imitate, and highly efficient proprietary resources (Barney et al. 2021). In contrast, the capability-based school emphasizes that an enterprise is a system or collection of capabilities, where these capabilities define the firm’s scale and scope. These capabilities consist of critical skills and tacit knowledge, forming an intellectual capital that serves as the foundation for decision-making and innovation, stemming from collective learning, mutual interaction, and participation among organizational members (Reihlen and Ringberg 2013). Enterprise capability theory highlights the importance of technology, resources, and knowledge (Teece 2014b). Among these, enterprises’ scientific capabilities stand out as a distinctive form of organizational capability, developed through active engagement in fundamental scientific research (Annapoornima and Soh 2006). These capabilities encompass the abilities to create, acquire, and absorb scientific knowledge, constituting a critical component of the enterprise’s intellectual capital.

The impetus for enterprises to engage in scientific research primarily stems from the potential to transform research findings into final products (Cardinal and Hatfield 2000). This prospect elevates the significance of enterprises’ scientific capabilities, which, despite the inherent uncertainties and serendipitous nature of scientific research, can enhance the likelihood of achieving innovation. The sources of scientific knowledge pivotal for enterprises’ scientific capabilities are varied, including collaborations with research institutions or the establishment of multifunctional new R&D organizations (Coriat et al. 2003). Science is integral to industrial advancement and foundational progress. Enterprises seeking competitive advantages must leverage scientific discoveries, relying not only on the generation of internal knowledge but also on the assimilation and integration of external knowledge sources. In science-based industries, knowledge is often tacit and complex, posing challenges in imitation, transfer, and absorption. The slow pace of understanding and applying such knowledge, particularly in grasping its full implications, is a noted obstacle (Karnani 2013). Research indicates that in science-based enterprises, tacit knowledge is predominantly held by inventors or researchers, necessitating the combined application of internal and external scientific knowledge for converting scientific understanding into innovative performance (Simonin 1999). Building on these observations, scholars posit that the core capabilities of science-based enterprises derive from multiple science-related dimensions, termed ‘scientific capabilities’ (Almeida et al. 2011). These capabilities are an amalgamation of internal and external basic research resources that enterprises utilize to develop or acquire basic research findings (Annapoornima and Soh 2006), and provide the direction and early scientific theoretical groundwork for continuous technological innovation (Genin and Levesque 2021).

Enterprises’ scientific capabilities

Referring to the research by Chen et al. (2007), we categorize these into internal and external scientific capabilities (Chen et al. 2007). Internal scientific capabilities encompass aspects like scientific level, internal interactive communication, information intelligence, and existing research and inventions (Della Malva et al. 2015; Ubeda et al. 2019). External scientific capabilities, on the other hand, include external research resources, international and domestic cooperation (Almeida et al. 2011), external interactive communication, and the acquisition of external research outcomes (Tijssen 2001). This study extends this framework, defining internal scientific capabilities as enterprises’ abilities to generate scientific knowledge, and external scientific capabilities as the abilities to collaborate in research and development with other organizations and to assimilate, integrate, and transform external knowledge.

Internal scientific capabilities are critical for transforming scientific knowledge into technological innovation and competitive advantage. Tang (2009) highlights that scientific knowledge serves as the source of technological innovation, which subsequently drives economic and social benefits (Tang 2009). Research in science-based industries underscores the importance of internal capabilities in innovation performance. For example, Archambault and Larivière (2011) demonstrate that firms engaging in scientific research produce patents with higher citation rates, reflecting greater value (Archambault and Larivière 2011). Similarly, Watts and Hamilton (2013) link scientific inputs to commercial outputs, showing that firms with a robust scientific foundation excel in new product innovation, particularly in industries like biotechnology and chemistry (Watts and Hamilton 2013). Moreover, Zhao et al. (2023) find that internal scientific capabilities positively correlate with the quantity and quality of patents in Chinese listed firms, enhancing market credibility, standard-setting influence, and talent attraction (Zhao et al. 2023). These findings suggest that internal scientific capabilities are particularly vital for knowledge-intensive and R&D-intensive firms, as well as those with dedicated research institutions.

In contrast, external scientific capabilities enable firms to collaborate with external organizations to access and integrate scientific knowledge. This collaborative approach is not only cost-effective but also fosters innovation performance (Liu et al. 2021). Guerrero et al. (2019) emphasize that firms increasingly engage in partnerships with academic and industrial organizations to leverage external knowledge for scientific innovation (Guerrero et al. 2019). Almeida et al. (2011) note that external scientific collaborations, including alliances with strategic partners and scientists, significantly influence innovation outcomes (Almeida et al. 2011). Lampathaki et al. (2012) argue that continuous and seamless collaboration with external systems enhances interoperability, reducing R&D costs, technological risks, and complexity (Lampathaki et al. 2012). Additionally, open innovation models challenge traditional closed systems, encouraging firms to learn from partners, embrace open science, and advance scientific discoveries (Slavova 2022). Despite their differences, internal and external scientific capabilities are complementary. Internal capabilities equip firms with the foundational knowledge necessary for innovation, while external capabilities expand access to diverse resources and collaborative opportunities. Together, these dimensions drive both the quantity and quality of innovation performance.

Enterprises’ scientific capabilities and technological innovation

For a long time, the academic community has not clearly distinguished between scientific knowledge and technical knowledge in the study of technological innovation, despite the significant differences that exist between the two. Scientific knowledge primarily focuses on the essence, laws, and intrinsic connections of natural and social phenomena. In contrast, technical knowledge emphasizes the application of these scientific principles to address practical problems, stressing aspects such as practicality, operability, and innovation. The relationship between science and technology is complex and remains one of the most important and intricate issues in the study of technological evolution. Scholars widely agree that in science-based industrial innovation, scientific knowledge serves as the foundation and source of technological advancement (Sorenson and Fleming 2004). An increasing number of researchers are beginning to explore the relationship between scientific capabilities and technological innovation performance (Hohberger 2016). The development of science-based industries is significantly supported by scientific research, with core technological advancements heavily reliant on new scientific discoveries. Investment in scientific innovation is shown to augment the output and quality of technological inventions, vital for enterprise survival and profitability. Basic research serves as the wellspring of technological innovation and plays a substantial role in fostering technological applications (Bush 2020; Mansfield 1991). Post-World War II industrial and enterprise growth in the United States, as observed by Pavvit (2001), was fundamentally fueled by basic research. Toole (2012) also underscores that increased investment in basic research enhances new product performance in enterprises (Toole 2012). Regarding the participation modalities in basic research, Lin and Yang (2020) suggest options such as establishing internal basic research departments or engaging in industry-university R&D collaborations to bolster enterprise innovation performance (Lin and Yang 2020). Despite universities being primary venues for basic research, Rosenberg (1990) and Fleming (2001) highlight the necessity of active involvement by enterprise internal research teams to acquire pertinent knowledge (Fleming 2001; Rosenberg 1990). As application demands increasingly influence basic research, enterprises, driven by their development needs, are incorporating basic research activities into their innovation processes, marking it as an integral component of the innovation chain (Zhao et al. 2023). Mansfield (1991) discovered in a survey of 76 American companies across seven industries that approximately 10% of new products and processes would not be developed without scientific research (Mansfield 1991).

While extensive research acknowledges the role of scientific knowledge in promoting technological innovation, much of the existing literature focuses on national and industry levels, predominantly employing qualitative methods. There is still a lack of sufficient evidence demonstrating the exact impact of corporate participation in basic research on innovation performance and the mechanisms involved (Wu et al. 2024). Therefore, it is essential to explore the relationship between enterprises’ scientific capabilities and technological innovation performance to provide theoretical guidance for companies engaging in basic research. Fortunately, there are well-established quantitative indicators for measuring both scientific and technical knowledge (Yang et al. 2024). These indicators have been widely used for benchmarking and evaluating science and technology. Specifically, publication-related metrics are primarily utilized to measure scientific capabilities, while patent-related indicators assess technological innovation capabilities (Chen et al. 2024). This provides a solid foundation for conducting empirical analysis in this study.

Hypothesis development

Enterprises’ scientific capabilities and innovation performance

Based on previous analysis, we divide scientific capabilities into internal scientific capabilities and external scientific capabilities. The concept of internal scientific capabilities in enterprises is fundamentally concerned with the organization’s inherent capacity to generate knowledge. Internal capabilities include three stages: investment in scientific research, management of scientific research, and the output of scientific research, with the latter being the resultant variable of the former two. It is understood that the transfer of scientific knowledge across organizational boundaries tends to be slower than within the confines of a single enterprise. Bartsch et al. (2013) assert that knowledge flows more efficiently within the boundaries of an organization, facilitated by technological interconnectedness (Bartsch et al. 2013). Furthermore, enterprises with robust innovative capabilities often engage with a broader spectrum of scientific and technological fields, enhancing their capacity for knowledge flow and absorption. Science-based enterprises, characterized by their diverse research capabilities and resource allocation, are particularly inclined towards internal research and development, focusing notably on basic research. Murray (2002) and Aghion et al. (2008) highlight that, in contrast to universities, these enterprises are more application-driven, contributing principle knowledge to the development of new products (Aghion et al. 2008; Murray 2002). Hence, enterprises are not merely consumers of basic research findings; they are active participants, laying the foundational knowledge for technological innovation.

The internal scientific capabilities of an enterprise encompass the development and acquisition of basic research outcomes. This includes directed basic research, applied research, forefront directional research in existing fields, exploratory research in new disciplines and cross-fields, and investment in ‘pre-competitive research’ related to product process application development (Bruno Cassiman et al. 2018). These capabilities provide a trajectory and foundational scientific theory for sustainable technological innovation within enterprises. Consequently, the scientific capabilities of an enterprise are indicative of its technological innovation capabilities, serving as a fundamental guarantor of technological capacity, guiding innovation development, and exerting a significant positive influence on enterprise innovation performance (Subramanian and Soh 2010).

In light of these theoretical considerations, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Enterprise’s internal scientific capabilities have a positive impact on innovation performance.

The concept of external scientific capabilities in enterprises focuses on their ability to assimilate scientific knowledge from external sources. These capabilities are largely contingent upon deep collaborations with external partners such as universities and research institutions. They encompass the processes of identifying, acquiring, interpreting, applying, transforming, and integrating new external scientific knowledge (Cohen and Levinthal 1990). Zahra and George (2002) delineate these into potential absorptive capacities (encompassing acquisition and digestion capacities) and actual absorptive capacities (including transformation, integration, and utilization capacities) (Zahra and George 2002).

In science-based industries, where knowledge is often tacit and complex, the transfer of such knowledge necessitates extensive interpersonal communication and interaction. Zucker et al. (2002) highlight the challenges posed by the ‘newness’ of knowledge, noting that without active participation in basic research teams, knowledge transfer can be exceedingly slow and arduous. For enterprises to accrue scientific knowledge and experience that catalyzes innovation, embedding themselves in pivotal scientific networks is essential. Such networks provide not just social capital but also facilitate tangible and intangible benefits from interactive and cooperative activities (Aldridge et al. 2014; Murray 2004). These benefits extend to information flow about market demands and complex technologies, enabling enterprises to reach technological innovation milestones (Aldridge et al. 2014).

The dynamics, interactivity, and circularity of networks have become central to contemporary innovative research. Strategic development in science-based industries demands comprehensive and intensive industry-university-research collaborations. Research in scientific networks demonstrates that such collaborations enhance enterprises’ rapid assimilation and learning of scientific knowledge (Baba et al. 2009), and provide tacit knowledge crucial for reducing innovation timelines (Jensen et al. 2007). Valuing basic research and fostering broad collaborations among enterprises, universities, and research institutions is vital for nurturing enterprise R&D capabilities, and the unique structure of R&D expenditure in science-based industries necessitates joint participation in basic research by enterprises, universities, and research institutes to fuel industrial development through innovation (Choi et al. 2018). Consequently, for enterprises, collaborating with external organizations to solidify and enhance their external scientific capabilities is imperative for not only their innovative development but also for the broader industry. Based on these theoretical insights, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Enterprise’s external scientific capabilities have a positive impact on innovation performance.

The mediating role of scientific innovation intensity

Scientific innovation intensity, also referred to as ‘scientific intensity’, ‘scientific relevance’, or ‘scientific proximity’, reflects the degree to which an enterprise is engaged in science-based innovation. This concept serves as an intuitive indicator of the interplay between science and technology, conceptualized as the exchange process from science to technology (Meyer 2002), or as a measure of the correlation and trends in technological opportunities (Van Looy et al. 2006).

Given the complex and non-linear relationship between scientific research and enterprise innovation performance, the translation of basic research into innovation performance is intricate. Fleming and Sorenson (2004) posit that scientific knowledge, by explaining phenomena and predicting new experiments, provides inventors with foundational insights. In science-based industries, innovation activities inherently link the scientific research at the front end with the technological R&D at the back end, disseminating knowledge from scientific research into technological innovation (Rickne 2006). Scientific innovation intensity bridges the gap between technological innovation and scientific knowledge discovery. It effectively links basic research with industrial development, preventing disconnection between academic research and practical applications, aiding in making scientific research more application-oriented, and expediting the transformation of scientific and technological advancements (Lee Fleming and Sorenson 2004). Researchers such as Motohashi and Tomozawa (2016) and Du et al. (2014) have discussed innovation models where technology directly emanates from science (Du et al. 2014; Motohashi and Tomozawa 2016). Huang et al. (2015) and Fukuzawa and Ida (2016) have further proposed the concept of ‘science-based’ innovation intensity indicators, suggesting that the intensity of scientific innovation acts as an intermediary variable (Fukuzawa and Ida 2016; Huang et al. 2015). Hence, enterprises engaging in basic research utilize scientific knowledge to yield innovative outcomes, which in turn are indicative of science-based innovation and can amplify the intensity of scientific innovation.

Science-based innovation plays a critical role in fostering invention activities in developing scientific fields, thereby laying the groundwork for industry formation and evolution. Consequently, the intensity of enterprise scientific innovation aids enterprises in consolidating their knowledge base and stimulating technological innovation outcomes. This intensity reflects the extent to which existing scientific knowledge informs the novelty, creativity, and applicability of a enterprise’s technological innovation (Michel and Bettels 2001), bridging disparate technical knowledge elements and catalyzing significant innovations. Research indicates that technological innovation in a science-based context is variably reliant on scientific knowledge, with innovations of higher scientific intensity containing richer scientific content and yielding more valuable technology. In the biological field, Sorenson and Fleming (2004) discovered that innovations with higher scientific intensity tend to diffuse more rapidly (Sorenson and Fleming 2004), possessing greater technical and economic value (Harhoff et al. 2003). Gittelman and Kogut (2003) showed that patents with high scientific intensity are frequently cited. Furthermore Gittelman and Kogut (2003), Petruzzelli et al. (2015) found that utilizing scientific knowledge positively impacts organizational performance in science-based industries (Petruzzelli et al. 2015). From a enterprise perspective, Nagaoka (2007) established that increased intensity of enterprise scientific innovation significantly enhances technological innovation performance (Nagaoka 2007). At a macro level, Van Looy et al. (2006) analyzed the relationship between scientific innovation intensity and technological capabilities, revealing that patents, which represent technological capabilities output, are generally positively correlated with scientific intensity (Van Looy et al. 2006).

Based on these theoretical insights, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Scientific Innovation Intensity mediates the relationship between internal scientific capabilities and innovation performance.

H4: Scientific Innovation Intensity mediates the relationship between external scientific capabilities and innovation performance.

The moderating role of scientific research funding

Governmental support for scientific and technological innovation activities often manifests through scientific research funding. This funding is a key mechanism used by governments to guide scientific endeavors and stimulate the production of scientific knowledge. To a certain extent, it represents the policy intention to promote certain areas of research. Currently, grants are the primary form of scientific research funding, emerging as a crucial public resource for scientific advancement. Lane (2009) notes that scientific research funding plays a pivotal role in enabling the purchase of equipment, provision of materials, and training of talent, thereby fostering the development of cutting-edge fields and enhancing national research capabilities (Lane 2009).

At the micro level, scientific research funding positively influences the increase in scientific outputs, enhances academic impact, promotes research collaboration, and boosts the citation frequency of funded research (Álvarez-Bornstein and Bordons 2021). Gök et al. (2016) and Costas and van Leeuwen (2012) found that funded research yields higher innovation outputs and social impact compared to unfunded research (Costas and van Leeuwen 2012; Gök et al. 2016). In quantum physics, Gao et al. (2019) demonstrated that the impact of funding exceeded the field’s average (Gao et al. 2019). Fedderke and Goldschmidt (2015) analyzed the South African National Research Foundation (NRF) funded projects and observed a positive influence of funding on publication numbers and citations, although noting variations across different subjects (Fedderke and Goldschmidt 2015). Additionally, Saqib and Rafique (2021) explored the link between health research funding and outputs in Pakistan, concluding that funding directly impacts scientific outputs (Saqib and Rafique 2021). Given these findings, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5a: Scientific research funding positively moderates the relationship between enterprise’s internal scientific capabilities and innovation performance.

H5b: Scientific research funding positively moderates the relationship between enterprise’s external scientific capabilities and innovation performance.

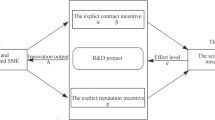

The theoretical model proposed in this study is based on the ‘capabilities-behavior-outcome’ pathway, illustrated in Fig. 1.

This figure illustrates the theoretical framework constructed in this study. It presents the proposed relationships between enterprises’ internal and external scientific capabilities and innovation performance, with scientific innovation intensity as a mediating variable and scientific research funding as a moderating variable. The model includes and visualizes hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H4, H5a, H5b, H= Hypothesis.

Method

Data resource

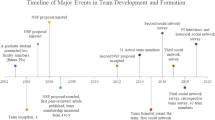

To delve into the formation mechanism of innovation performance in science-based enterprises and to explore how scientific capabilities impact innovation performance, this study focuses on the biopharmaceutical industry, Marsili (2001) identified industries like biotechnology, medicine, electronic communications, and chemicals as highly reliant on scientific knowledge, thus categorizing them as science-based industries (Marsili 2001). In terms of data acquisition, this study employs data from the CSMAR database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and the Incopat patent search platform, undergoing a rigorous data selection and processing procedure as illustrated in Fig. 2.

This flowchart outlines the three-step data processing process: (1) identifying eligible biopharmaceutical enterprises from the CSMAR database, (2) collecting research publication and patent data from CNKI and Incopat platforms, and (3) matching and filtering the dataset to finalize a sample of 204 enterprises.

Firstly, using the CSMAR database, we extracted a list of all publicly listed enterprises in China. Drawing on the work of Wei et al. (2021), we utilized the “Industry Classification (2012)” by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) and the “2017 High-tech Industry (Manufacturing) Classification” by the National Bureau of Statistics of China to select high-tech industries engaged in scientific research and development, such as pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and electronics. The high-tech manufacturing industry in China is categorized into 21 sectors, and through comparative analysis, we selected the CSRC’s industry codes for these sectors. Based on these criteria, we ultimately chose the biopharmaceutical industry (C27) as our research focus, compiling a database of 418 publicly listed biopharmaceutical enterprises. We retrieved basic data of these listed enterprises, including their establishment years, R&D investments, and employee numbers, from the CSMAR database (Fig. 2).

Secondly, based on these 418 biopharmaceutical enterprises, we used the CNKI database to conduct a bulk search using the company names as author affiliations, covering the period from 1993 to 2024. This search yielded 14,312 articles, with a total of 82,457 citations and 4,692,819 downloads. Subsequently, using the Incopat patent search platform, we searched for patents with the company names as applicants for the same period, retrieving a total of 30,425 patents with 194,006 citations.

Finally, we matched and aggregated the basic enterprise information, research publications, and patent data from the three databases. Recognizing the inadequacy of small-scale patent and paper output as measures of enterprise innovation, we selected biopharmaceutical enterprises with at least five publications and patents for our sample. We also removed outliers, retaining 204 biopharmaceutical enterprises. These enterprises have published 12,491 articles, representing 87.3% of the industry, and applied for 22,507 patents, accounting for 74% of the industry, indicating that our sample selection is highly representative and encompasses the majority of biopharmaceutical enterprise data.

Measurement

This research employs papers and patents as representative outputs of scientific knowledge and technological innovation, respectively. These are widely recognized as indicators for identifying and predicting hotspots and frontiers in scientific and technological domains. Analyzing the correlation between them facilitates a deeper understanding of the interplay between science and technology (Kim and Lee 2015). Regarding the assessment of enterprises’ scientific capabilities, this study adopts the widely accepted benchmark of scientific research outcomes as an indicator of scientific capabilities, reflecting the results of research investment and organizational management. Bibliometric indicators, including publication-related indicators, are employed to quantitatively measure scientific capabilities. External scientific capabilities are defined as an enterprise’s ‘scientific exchanges and collaborations with external organizations’ (Almeida et al. 2011). Hence, this study measures an enterprise’s external scientific capabilities based on the quantity and quality of co-authored publications with universities and research organizations.

Scientific innovation intensity, also known as ‘scientific relevance’ or ‘scientific proximity,’ indicates the relationship between science and technology, serving as a metric for the linkage between scientific knowledge and technological innovation outcomes. This concept draws upon the impact of innovation results on non-patented literature citations (NPC). In evaluating technological innovation performance, this study utilizes patent-related indicators such as the number and value of patents, which are established methods in academic research for assessing technological capabilities (Cassiman et al. 2008; Meyer 2002; Sung et al. 2015).

Based on the above analysis, we measured each variable as Table 1.

Empirical analysis results

Based on the measurement of variables, this study employs stepwise regression analysis to examine the data. Stepwise regression, a method within multiple regression analysis, involves sequentially introducing variables into the model. After each variable is added, an F-test is conducted, and t-tests are performed on the already included variables. If a previously included explanatory variable becomes non-significant due to the introduction of a new variable, it is removed. This process ensures that the regression equation only includes significant variables before a new variable is added. Stepwise regression is often used to establish an optimal or suitable regression model, particularly when dealing with numerous variables, allowing for a more in-depth exploration of the dependency relationships between variables.

Therefore, this study uses stepwise regression analysis to test the impact of enterprises’ scientific capabilities on innovation performance, and to explore the mediating effect of scientific innovation intensity and the moderating effect of research funding.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

The descriptive statistics of the variables are presented in Table 2. It is important to note that to standardize the regression model, logarithmic transformations were applied to variables with large values, including ISCQ, ESCQ, RDN, and employee.

The results of the correlation analysis between the variables are shown in the table below. The correlation analysis indicates significant correlations between the independent variables, dependent variables, mediating variable, and moderating variable, providing a foundation for multiple linear regression analysis (Table 3).

Main regression analysis results

When considering the quantity dimension of innovation performance (PN) as the dependent variable, Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3 in Table 4 present the relationship between independent variables (internal scientific capabilities and external scientific capabilities) and the dependent variable. The stepwise regression analysis revealed that ISCQ, ESCN, and RDN were significant predictors of PN. As these variables were added sequentially, the R-squared value increased from 0.329 in Model 1 to 0.408 in Model 3. The overall model significance in all three models was below 0.05, indicating that the models are statistically reliable. An examination of the regression coefficients for ISCQ, ESCN, and RDN shows values of 0.143, 0.397, and 0.348, respectively, with significance p values all below 0.05. These results confirm a significant main effect. Specifically, the quality dimension of internal scientific capabilities and the quantity dimension of external scientific capabilities both significantly enhance enterprise innovation performance. Thus, hypotheses H1 and H2 are partially validated.

Similarly, when considering the quality dimension of innovation performance (PCN) as the dependent variable, Model 4, Model 5, and Model 6 in Table 4 illustrate the relationship between the independent variables and PCN. Stepwise regression results identified RDN, ESCN, and ISCN as significant predictors. As these variables were added progressively, the R-squared value increased from 0.289 in Model 4 to 0.310 in Model 6. The significance levels for all three models remained below 0.05, confirming their statistical reliability. The regression coefficients for ISCN, ESCN, and RDN were 0.171, 0.192, and 0.386, respectively, with all results being statistically significant (p < 0.05). Based on these findings, it can be concluded that hypothesis H1, which posits a positive correlation between internal scientific capabilities and innovation performance, is supported. Similarly, hypothesis H2, positing a positive correlation between external scientific capabilities and innovation performance, is also validated.

Mediating effect of scientific innovation intensity

Table 5 presents the stepwise regression analysis results for testing the mediating effect of scientific innovation intensity (NPCN). In Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3, the relationships between the independent variables and NPCN are analyzed. The regression coefficients for ISCQ, ESCN, and RDN are 0.127, 0.535, and 0.224, respectively, with all p-values below 0.05. When the quantity dimension of innovation performance (PN) is used as the outcome variable, Model 4 incorporates NPCN as the mediating variable alongside the independent variables. The regression coefficient for NPCN is 0.973, with a significance p value less than 0.01. This finding supports hypotheses H3 and H4, and demonstrates that NPCN serves as a partial mediator between scientific capabilities and PN. Similarly, when the quality dimension of innovation performance (PCN) is used as the dependent variable in Model 5, NPCN remains a significant mediator. The regression coefficient for NPCN is 0.968, with a significance p value less than 0.01. This also supports hypotheses H3 and H4. Based on the comprehensive analysis above, it can be concluded that the impact of enterprises’ scientific capabilities on innovation performance is mediated by scientific innovation intensity.

Moderating effect of scientific research funding

Table 6 presents the stepwise regression analysis results for testing the moderating effect of scientific research funding on the relationship between enterprises’ scientific capabilities and innovation performance. In Model 1 and Model 2, the interaction terms of internal scientific capabilities and research funding (ISCFN) and external scientific capabilities and research funding (moderator) are examined with PN as the dependent variable. The results indicate that the coefficient of ISCFN*ISCN is significant, confirming that research funding positively moderates the relationship between internal scientific capabilities and PN. This suggests that research funding enhances the ability of enterprises to translate their internal scientific capabilities into increased innovation output. However, ESCFN is not significant, indicating that research funding does not moderate the relationship between external scientific capabilities and PN. These findings support hypothesis H5a but do not support hypothesis H5b.

When considering PCN as the dependent variable in Model 3 and Model 4, the regression results reveal that neither ISCFN nor ESCFN are significant. This indicates that while research funding may boost the quantity of innovation output, it does not directly improve the quality of innovation performance.

To further examine the moderating effect, a simple slope analysis was conducted in this study. Using the mean value of Scientific Research Funding (ISCFN) as a reference, one standard deviation above and below the mean was calculated to create two scenarios: high ISCFN and low ISCFN. The results indicate that internal scientific capabilities have a significant positive impact on innovation performance (PN) under both high and low ISCFN conditions. However, the effect is stronger under the high ISCFN scenario. This suggests that when enterprises with strong internal scientific capabilities receive higher levels of Scientific Research Funding, their innovation performance improves more significantly. The findings are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Endogeneity test—instrumental variable method

In the regression model, despite efforts to control for factors that might simultaneously affect enterprises’ scientific capabilities and innovation performance, the empirical results may still be influenced by unobservable factors. This issue of omitted variables can bias the estimated coefficients of enterprises’ scientific capabilities variables. Additionally, higher innovation performance can lead to better business performance, which enables enterprises to invest more in R&D and scientific resources, potentially creating a positive feedback loop that affects enterprises’ scientific capabilities. Therefore, there may be a reverse causality between the two. To mitigate endogeneity issues caused by omitted variables, measurement errors, or reverse causality, this study further adopts the instrumental variable (IV) estimation method.

Drawing on the approach of Chong et al. (2013), this study uses the total number of papers published by the biopharmaceutical industry in the city where the enterprise is located as the instrumental variable. The instrumental variable regression is based on this sample. (1) Relevance: the total number of papers published by the biopharmaceutical industry in a enterprise’s city represents the region’s industrial development and R&D capabilities. Strong regional R&D capabilities can drive the development of local enterprises, indicating a high correlation between enterprises’ scientific capabilities and the overall industrial capabilities of the region. (2) Exogeneity: the scientific research capabilities of the region where the enterprise is located do not directly impact the innovation performance of a specific enterprise, especially patent applications. Thus, the chosen IV meets the relevance and exogeneity assumptions of instrumental variables.

The table below reports the two-stage regression results of the instrumental variable approach. Column (1) presents the first-stage regression results, and Column (2) presents the second-stage regression results. The first-stage regression results show that the coefficient estimate of the IV is significantly positive at the 5% level, indicating that the stronger the scientific capabilities of the region, the stronger the enterprise’s scientific capabilities, validating the relevance assumption of the instrumental variable. The second-stage regression results show that the coefficients of the independent variables are significantly positive at the 5% level, indicating that even after addressing potential endogeneity, the conclusions of this study remain valid. Specifically, enterprises’ scientific capabilities significantly promote innovation performance, and scientific innovation intensity continues to exhibit a mediating effect. Additionally, this study tested for weak instrumental variables, and the results indicate that there is no weak instrument problem (Table 7).

Robustness test

To ensure the robustness of the conclusions, this study conducted robustness checks, primarily by excluding specific samples. The enterprise sample in this study consists of Chinese publicly listed enterprises, including those listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) A-shares, SSE B-shares, Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) A-shares, SZSE B-shares, ChiNext, and the National Equities Exchange and Quotations (NEEQ, or “New Third Board”). Different exchanges and segments have distinct starting digits for their stock codes. For example, SSE A-shares start with 600, 601, or 603, while ChiNext stocks start with 300. Using this standard, we retained only SSE A-shares and SZSE A-shares enterprises, leaving a sample of 144 enterprises. We then conducted a second regression analysis with the remaining variables. The robustness test results indicate that, overall, the impact of enterprises’ scientific capabilities on innovation performance remains significant. Therefore, the conclusions of this study are robust and reliable, and do not fundamentally change with variations in external conditions.

Simulation research

Simulation research design

While the utilization of papers and patents as proxies for scientific knowledge and technological innovation achievements is a well-established practice in academia, the employment of secondary data sources to reflect the nexus between enterprises’ scientific capabilities and innovation performance is not without limitations. For instance, secondary data may present issues such as data correlation, leading to low empirical research fit. Additionally, the potential lack of timeliness, wide-ranging data spans, and the static nature of these data sources could hinder the accurate observation of the dynamic evolution between scientific capabilities and technological innovation.

To address these limitations, this study proposes a multi-agent simulation approach to complement the empirical analysis. This study will utilize NetLogo for simulation modeling, an integrated environment for multi-agent modeling and simulation that is adept at simulating natural and social phenomena. NetLogo is particularly well-suited for modeling complex systems evolving over time. By enabling modelers to direct the actions of hundreds or thousands of independent “agents,” it facilitates the exploration of the interplay between micro-level individual behaviors and macro-level patterns.

The simulation component of this study will encompass two types of real entities: enterprises and public institutions. Additionally, scientific knowledge and technological innovation achievements (patents) will be incorporated as virtual entities within the simulation. The interactions and relationships among these entities will be modeled to provide a more nuanced understanding of the dynamics at play. The specific configuration of these relationships and their representation in the simulation will be detailed in Table 8.

In constructing the multi-agent simulation model, this study establishes the following initial assumptions to guide the modeling process:

-

(1)

Knowledge creation capabilities: enterprises have the capacity to assimilate public scientific knowledge, thereby enhancing their own knowledge creation capabilities.

-

(2)

Technological innovation capabilities: by learning from public scientific knowledge, enterprises can significantly improve their technological innovation capabilities.

-

(3)

Collaboration with public institutions: enterprises are capable of collaborating with public institutions, contributing to the generation of new scientific knowledge.

-

(4)

Costs incurred in knowledge creation: the process of knowledge creation by enterprises entails the consumption of certain organizational resources, representing a cost to the enterprise.

-

(5)

Returns from technological innovation: the technological innovation achieved by enterprises is posited to yield quantifiable operational returns.

These assumptions are pivotal in developing a comprehensive simulation model. They reflect key dynamics and interactions between enterprises and public institutions and their respective roles in the knowledge creation and innovation process. The assumptions also underscore the resource implications and potential benefits associated with these activities, providing a realistic foundation for the simulation analysis (Table 9).

The specific simulation flowchart is as follows (Fig. 4):

Simulation research results

The relationship of scientific capabilities and innovation performance

The simulation results reveal significant trends in the relationship between scientific knowledge output and technical performance within science-based industries. These trends are observable across different stages of industry development, as delineated in the simulation model (Fig. 5).

Industry gestation stage (time step set to 200): during this initial phase, the simulation (Fig. 5a) indicates that the scientific knowledge output in the industry predominantly originates from public institutions. Enterprises exhibit limited engagement in basic research at this stage, underscoring a nascent stage of enterprise involvement in scientific knowledge generation.

Industry formation stage: at this juncture, the simulation (Fig. 5b) illustrates a shift towards collaborative efforts between enterprises and public institutions in producing scientific knowledge. Enterprises start to leverage existing knowledge within the industry, including both public institutions’ and their own scientific achievements, to foster science-based innovation. This stage marks the beginning of a more active enterprise role in harnessing scientific knowledge for innovation.

Industry mature stage: the simulation (Fig. 5c) demonstrates a significant upsurge in both scientific knowledge output and technological innovation achievements. Notably, enterprises emerge as the principal contributors to scientific research. Enhanced internal and external scientific capabilities within these enterprises are observed, with science-based innovation playing a pivotal role in shaping enterprise technological innovation capabilities.

Overall, these simulation results underscore the evolving role of enterprises in science-based industries, from initial observers and learners to active contributors and innovators. The progression from the industry gestation to maturity stages highlights the growing importance and impact of enterprise participation in scientific research and innovation.

In analyzing the data from a single enterprise perspective within science-based industries, the study classified enterprises based on their innovation performance and depicted the findings in a histogram. This visualization reveals a typical ‘long-tail effect’ in these industries, characterized by a few leading enterprises with robust scientific and technological innovation capabilities. These top-performing enterprises significantly outpace others in terms of scientific knowledge output and innovation performance, dominating their respective industries, a finding that aligns with empirical observations in the real world.

For individual enterprises, the study observes significant positive correlations between their scientific capabilities, scientific innovation intensity, and innovation performance. This correlation is indicative of the influential role scientific capabilities and innovation intensity play in determining an enterprise’s performance in innovation. Such findings lend further empirical support to our hypothesized relationship, underlining the critical importance of scientific capabilities and innovation intensity in driving successful innovation outcomes in science-based industries (Fig. 6).

The impact of scientific research funding

-

(1)

Impact on innovation performance

This study utilized a model running 1000 time steps to assess the impact of different levels of scientific research funding on knowledge output and technological innovation performance (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7: The impact of research funding on innovation performance. No funding scenario: with zero scientific research funding, the peak technological innovation performance of enterprises reached 8390 units, while the output of scientific knowledge remained relatively low (Fig. 7a).

Medium funding level (5% of R&D investment): at this funding level, technological innovation performance peaked at 10,600 units, accompanied by a significant increase in scientific knowledge output (Fig. 7b).

High funding level (10% of R&D investment): in this scenario, a peak technological innovation performance of 30,000 units was observed, marking a substantial improvement. While the output of scientific knowledge also improved, its increase was not as pronounced as that of technological innovation performance (Fig. 7c).

These results indicate that increased levels of scientific research funding positively impact technological innovation performance, with the most significant improvement observed at the highest funding level. However, the enhancement in scientific knowledge output, although positive, is less dramatic than the gains in technological innovation.

-

(2)

Impact on enterprise survival

No funding scenario: with no scientific research funding, the size of enterprises in the industry fluctuated around 59 units (Fig. 8a).

Medium funding level (5% of R&D investment): at this funding level, enterprise size fluctuated around 71 units (Fig. 8b).

High funding level (10% of R&D investment): the size of enterprises increased, fluctuating around 111 units under this higher funding condition (Fig. 8c).

The simulation results suggest that scientific research funding plays a significant role in fostering enterprise survival and growth. Increased funding levels correlate with greater enterprise size and a more robust technological performance output. This implies that strategic investment in scientific research funding can catalyze innovation returns, enhance competitive survival, and contribute to more dynamic industrial development.

Conclusion and discussion

Conclusion

This study focuses on science-based enterprises, elucidating the concept of enterprises’ scientific capabilities from a theoretical perspective. By employing both empirical research and simulation methods, it explores the impact mechanisms of enterprises’ scientific capabilities on innovation performance. The study identifies the mediating effect of scientific innovation intensity and validates the moderating effect of research funding. The research conclusions are as follows:

Firstly, both the quantitative and qualitative dimensions of internal scientific capabilities positively impact its innovation performance. Engaging in scientific research helps enterprises develop their internal scientific capabilities, facilitating the rapid flow, absorption, and transformation of scientific knowledge, thereby promoting the output of innovation performance.

Secondly, the quantitative dimension of external scientific capabilities positively influences enterprises’ innovation performance. Collaborating with external organizations on basic research and development allows enterprises to acquire scientific knowledge, expanding the scale and scope of knowledge output, which positively impacts innovation performance. However, while the focus might be on the quantity of scientific output due to the need to assess the performance of industry-university-research collaborations, there is insufficient attention to quality factors. Whether the scientific knowledge from these collaborations can be converted into innovation performance largely depends on the enterprise’s ability to absorb this knowledge and its science-based innovation capability. If the enterprise’s technological development does not deeply integrate with scientific breakthroughs, it will be challenging to produce high-quality innovation outcomes.

Thirdly, scientific innovation intensity, as measured by non-patent literature citations, partially mediates the relationship between enterprises’ scientific capabilities and innovation performance. The essence of enterprise’s scientific innovation is the ability to directly use scientific knowledge to generate innovative outcomes. The path from scientific capabilities to technological capabilities is not linear, with science-based innovation playing a crucial role. Enterprises must rely on scientific breakthroughs to innovate, then continuously iterate technologies based on these innovations to develop innovative technological capabilities.

Lastly, scientific research funding positively moderates the relationship between internal scientific capabilities and innovation performance but does not positively moderate the relationship between external scientific capabilities and innovation performance. Scientific Research funding can alleviate the pressure of R&D costs, enhancing an enterprise’s willingness to engage in scientific research, which positively impacts innovation performance. However, providing research funding to external collaborating organizations does not necessarily improve the enterprise’s innovation performance. This discrepancy is largely related to the goal orientation of the various innovation entities in industry-university-research collaborations. Public institutions tend to focus on research tasks and lack motivation for technology application and transformation. Therefore, it is crucial to emphasize the deep integration of industry-university-research collaborations.

These conclusions offer a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics between scientific capabilities, innovation intensity, and funding, contributing to the discourse on fostering innovation in science-based enterprises.

Theoretical contributions

Science plays a crucial role in industrial development and enterprise innovation, prompting an increasing number of enterprises to actively engage in fundamental research. However, theoretical discourse has not adequately addressed this issue, resulting in a lack of corresponding theoretical foundations and guidance. Therefore, this study focuses on science-based enterprises, introducing the concept of enterprises’ scientific capabilities. It enriches the theoretical framework of enterprise capability theory by empirically analyzing the impact of scientific capabilities on technological innovation performance and its underlying mechanisms, yielding significant theoretical contributions and practical value.

-

(1)

Theoretical contribution: this research expands the content of enterprise capability theory. The current theoretical framework remains incomplete, overly emphasizing internal resources while neglecting the importance of external cooperative networks and intellectual resources (Ma et al. 2021). Although enterprise capability theory acknowledges the value of knowledge resources, it has not clearly distinguished between scientific knowledge and technological knowledge. This study introduces the novel concept of enterprises’ scientific capabilities, further refining their meaning by categorizing them into knowledge-creating internal scientific capabilities and knowledge-absorbing external scientific capabilities, and specifying concrete measurement indicators for each dimension. This work fills the gap in research on enterprises’ scientific capabilities and lays a theoretical foundation for future related studies.

-

(2)

Exploration of mechanisms: this study explores the mechanisms through which enterprises’ scientific capabilities influence innovation performance, conducting an in-depth analysis from both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. This provides a valuable theoretical complement to existing research. Additionally, we validate the significant role of scientific innovation intensity in this process, reflecting the extent to which enterprises engage in science-based innovation. While some scholars have qualitatively discussed the importance of science-based innovation in industrial development, few studies have conducted in-depth quantitative analyses, making this a notable theoretical contribution of our research.

-

(3)

Practical value: from a practical perspective, the findings of this study suggest that enterprises should prioritize the cultivation of both internal and external scientific capabilities and strengthen science-based innovation to effectively enhance technological innovation performance. This provides important practical insights for enterprise development, particularly for science-based enterprises, and offers guidance for national policy formulation.

Practical inspiration

This study, focusing on science-based enterprises, elaborates on the essential role of scientific knowledge in sustainable enterprise development and its emergent status as a competitive focal point in high-tech enterprise growth. The research underscores the need for enterprises to transition from a narrow focus on technical and process knowledge to embracing science-based innovation and enhancing scientific innovation capabilities. To build independent innovation capabilities, enterprises should engage in both basic and applied research to nurture their internal scientific capabilities. However, as indicated by the simulation results, not all enterprises benefit equally from scientific research. Smaller enterprises, in particular, may face significant survival risks if they over-invest in basic research. Thus, developing scientific capabilities requires long-term investment and sustained commitment. Moreover, fostering external cooperation with universities and research institutions is essential for enhancing external scientific capabilities. While these collaborations can increase the quantity of innovation, they do not always lead to corresponding improvements in the quality of innovation. This highlights the need for application-oriented partnerships and a focus on absorbing and transforming external knowledge. Additionally, enterprises should actively integrate scientific knowledge into their technological innovation processes, strengthening the synergy between science and technology. Science-based innovation serves as the foundation for technological advances, shaping enterprises’ technical capabilities and generating numerous valuable outcomes.

Finally, the findings of this study underscore the critical role of scientific research funding in enhancing innovation performance, particularly through its impact on internal scientific capabilities. Traditional funding policies have primarily focused on supporting universities and research institutions, often overlooking the potential of enterprises as key players in science-based innovation. Policymakers should consider shifting this approach by providing greater funding support directly to enterprises engaged in fundamental research, especially during the early stages of industrial development. Such support can encourage enterprises to actively participate in foundational scientific exploration, thereby increasing their survival probability and fostering the development of science-based industries. By integrating enterprises into the broader research ecosystem and equipping them with the resources needed for long-term innovation, governments can accelerate the transformation of scientific knowledge into economic and technological advancements. This shift in policy focus will not only promote a more balanced innovation ecosystem but also strengthen the competitive edge of industries reliant on scientific breakthroughs.

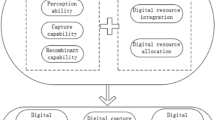

Furthermore, the study posits four paths to achieve technological innovation performance in science-based industries (Fig. 9):

-

(1)

Path 1—Independent innovation: engaging deeply in basic scientific research to enhance internal capabilities, leading to technological innovation.

-

(2)

Path 2—Cooperative R&D: collaborating with external entities in basic research to develop external capabilities, while still achieving technological innovation.

-

(3)

Path 3—Scientific absorption: utilizing external scientific breakthroughs for science-based innovation without direct involvement in basic research.

-

(4)

Path 4—Technical iteration: focusing on purely applied technological innovation without direct participation in basic research.

The above four paths are some ways to achieve technological innovation performance and do not correspond to a certain type of enterprise. Among them, path (1) and (2) are typical and necessary strategies adopted by science-based enterprises, often existing in the top enterprises in science-based industries. These enterprises are leaders in the industry, have a large amount of innovation resources, actively invest in basic scientific research, and lead the development process of the entire industry, Stimulate a large number of breakthrough innovations; The path(3)and (4) often exist in latecomer enterprises and are followers in the process of industrial development. These types of enterprises require strong scientific knowledge absorption ability, internal transformation of publicly available scientific and technological knowledge, and formation of their own technological capabilities. Due to their lack of participation in basic research, research and development costs are relatively low, and they are mostly incremental innovations. In the short term, they can seize the market with lower costs, But it cannot become the dominant player in the industry and affect its development. These paths represent strategies to attain technological innovation, with no intrinsic preference for any particular path. Enterprises may adopt one or more of these strategies to foster innovation.

Limitations and future directions

This study advances the understanding of enterprises’ scientific capabilities by categorizing them into internal and external dimensions; however, it is still an emerging area of research with limitations that warrant further discussion. First, the classification criteria for internal and external scientific capabilities remain basic and could benefit from more rigorous theoretical refinement. Future research could enrich the conceptualization of enterprises’ scientific capabilities, drawing from knowledge management perspectives, such as knowledge creation, acquisition, absorption, and transformation. Additionally, this study does not comprehensively address the factors influencing the cultivation and enhancement of enterprises’ scientific capabilities. Future studies could investigate human factors, such as the roles of employees, executive teams, and founders with scientific knowledge backgrounds, as well as the diversity and depth of existing scientific knowledge. The impact of scientific communities, including prominent and bridging scientists, and the role of emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and digitalization, should also be explored.

A significant limitation lies in the assumptions made within the simulation model employed in this study. The simplifications and constraints inherent in the model may influence the results, necessitating caution in interpretation. Future research could delve deeper into the assumptions of simulation models, evaluate their potential biases, and refine methodologies to enhance the robustness of the findings.

Moreover, this study primarily focuses on science-based enterprises within a single industry and national context. Future research could expand the scope by exploring other industries or conducting cross-country comparative analyses to understand how enterprises’ scientific capabilities function under different institutional, cultural, and economic conditions. Such studies could also examine how these capabilities contribute to fostering emerging industries, transforming traditional industries, and enhancing the sustainability and competitiveness of entire industrial ecosystems.

By addressing these limitations and expanding the research scope, future studies could provide more comprehensive insights into the development and application of enterprises’ scientific capabilities in diverse contexts.

Data availability

The data used in this paper were obtained from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and the Incopat patent platform. The website is available at https://data.csmar.com/, https://www.cnki.net/ and https://www.incopat.com/, respectively. Due to the involvement of data licensing in the databases, if validation is required, data will be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aghion P, Dewatripont M, Stein JC (2008) Academic freedom, private‐sector focus, and the process of innovation. RAND J Econ 39(3):617–635

Aldridge TT, Audretsch D, Desai S, Nadella V (2014) Scientist entrepreneurship across scientific fields. J Technol Transf 39:819–835

Almeida P, Hohberger J, Parada P (2011) Individual scientific collaborations and firm-level innovation. Ind Corp Change 20(6):1571–1599. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtr030

Álvarez-Bornstein B, Bordons M (2021) Is funding related to higher research impact? Exploring its relationship and the mediating role of collaboration in several disciplines. J Informetr 15(1):101102

Annapoornima MS, Soh PH (2006) The impact of scientific capability on valuable innovation. Paper presented at the IEEE international conference on management of innovation and technology (ICMIT 2006), Singapore, Singapore

Archambault É, Larivière V (2011) Scientific publications and patenting by companies: a study of the whole population of Canadian firms over 25 years. Sci Public Policy 38(4):269–278. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234211x12924093660192

Åstebro T, Bazzazian N, Braguinsky S (2012) Startups by recent university graduates and their faculty: implications for university entrepreneurship policy. Res Policy 41(4):663–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.01.004

Baba Y, Shichijo N, Sedita SR (2009) How do collaborations with universities affect firms’ innovative performance? The role of “Pasteur scientists” in the advanced materials field. Res Policy 38(5):756–764

Barney JB, Ketchen DJ, Wright M (2021) Resource-based theory and the value creation framework. J Manag 47(7):1936–1955. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063211021655

Bartsch V, Ebers M, Maurer I (2013) Learning in project-based organizations: the role of project teams’ social capital for overcoming barriers to learning. Int J Proj Manag 31(2):239–251

Bush V (2020) Science, the endless frontier. Princeton University Press

Cardinal LB, Hatfield DE (2000) Internal knowledge generation: the research laboratory and innovative productivity in the pharmaceutical industry. J Eng Technol Manag 17(3-4):247–271

Carpenter MP, Narin F (1983) Validation study: patent citations as indicators of science and foreign dependence. World Pat Inf 5(3):180–185

Cassiman B, Veugelers R, Zuniga P (2008) In search of performance effects of (in)direct industry science links. Ind Corp Change 17(4):611–646. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtn023

Cassiman B, Veugelers R, Arts S (2018) Mind the gap: capturing value from basic research through combining mobile inventors and partnerships. Res Policy 47(9):1811–1824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.06.015

Chen J, Zheng Y-Y, Qiu J-M, Yu F-Z (2007) Discussion and definition of the concept of enterprise scientific capability. Stud Sci Sci S 2:210–214

Chen X, Mao J, Ma YX, Li G (2024) The knowledge linkage between science and technology influences corporate technological innovation: evidence from scientific publications and patents. Technol Forecast Soc Change 198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122985

Choi H, Shin J, Hwang W-S (2018) Two faces of scientific knowledge in the external technology search process. Technol Forecast Soc Change 133:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.02.020

Chong TTL, Lu LP, Ongena S(2013) Does banking competition alleviate or worsen credit constraints faced by small- and medium-sized enterprises? Evidence from China. J Bank Finance 37(9):3412–3424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.05.006

Cohen WM, Levinthal DA (1990) Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm Sci Q 35(1):128–152

Coriat B, Orsi F, Weinstein O (2003) Does biotech reflect a new science-based innovation regime? Ind Innov 10(3):231–253