Abstract

Corporate environmental publicity is a vital tool for enhancing a company’s image and strengthening information exchange, significantly impacting corporate green development. Using a dataset of Chinese A-share listed companies from 2008 to 2020, we investigated the influence of corporate environmental publicity on green innovation. The results indicate that while corporate environmental publicity increases overall patent output, this growth is primarily driven by strategic rather than substantive green innovation. Further analysis reveals that corporate environmental publicity behaviors, motivated by greenwashing, reputation mechanisms, environmental subsidies, and R&D manipulation, lead to these outcomes. Notably, we found that heavily polluting enterprises are more adversely affected by this phenomenon, whereas ISO 14001 environmental certification and government regulation can mitigate the inconsistency between corporate environmental publicity and actual practices, thereby promoting substantive environmental actions. This study extends the research on factors influencing green innovation, aiming to minimize the negative effects of corporate environmental publicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, worsening global environmental pollution has resulted in over ten million deaths annually—approximately 16% of total global mortality (Landrigan et al. 2018). As the world’s second-largest economy, China is also severely affected by pollution. According to Yale’s Environmental Performance Index, China ranks only 120th out of 180 economies (Cheng et al. 2019). Against this backdrop, green innovation–driven transformation has emerged as a vital pathway for harmonizing economic and environmental benefits, attracting significant scholarly attention. Studies confirm that green transformation is crucial in reconciling corporate growth with environmental conservation (Tariq et al. 2017; Chuang and Huang 2018) and that innovation-led transformation emphasizing win–win outcomes is a key driver for corporate survival and sustainable development (Pan et al. 2020; Guo et al. 2024; Farza et al. 2021; Yi et al. 2023; Mo et al. 2022). This paper explores the impact of corporate environmental publicity on the drivers of green innovation.

Corporate environmental publicity refers to the strategies and techniques used by companies to disseminate eco-friendly philosophies, showcase environmental achievements, and demonstrate their commitment to environmental responsibility (Aerts and Cormier 2009). Amid severe challenges such as climate change, resource depletion, and biodiversity loss, reporting and disseminating environmental information have become vital ways for companies to demonstrate social responsibility (Cho and Patten 2007). Effective environmental publicity enhances public awareness of corporate environmental efforts, strengthens brand image and value, and boosts competitiveness (Torelli et al. 2020), while also encouraging consumers and investors to support eco-friendly enterprises, thereby advancing sustainable development (Chen and Chang 2013). In recent years, the Chinese government has strengthened the formulation and implementation of environmental policies and increased supervision of corporate environmental disclosure (Liu et al. 2019), leading to heightened emphasis on environmental information reporting among Chinese companies (Marquis and Qian 2014; Weber 2014).

Established scholars have substantiated that corporate environmental publicity influences internal green operations by raising awareness of environmental issues and promoting green projects (Dangelico and Pujari 2010), while also enhancing consumer and investor recognition and reinforcing brand image (Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez 2009). However, excessive environmental publicity may erode trust and hinder the progress of green initiatives (Lyon and Montgomery 2015), and superficial eco-friendly actions—due to their lack of substantive measures—can negatively impact financial performance and further impede green development (Walker and Wan 2012). In summary, there is no consensus on the impact of corporate environmental publicity on green initiatives. This paper will explore their relationship in depth, focusing on the mechanisms through which environmental publicity influences green innovation and offering a fresh perspective on the drivers of green innovation.

For several compelling reasons, we posit that corporate environmental publicity facilitates green innovation. Internally, disclosing environmental information enhances a company’s awareness and responsibility toward environmental issues, prompting it to adopt additional eco-friendly measures and drive green development (Dangelico and Pujari 2010; Bai and Lyu 2023). Moreover, environmental publicity fosters a green corporate culture that attracts and retains talent with ecological values (Bansal and Roth, 2000). Externally, promoting an eco-friendly image garners greater public support, broadens sales channels, and provides financial backing for green innovation (List and Sturm, 2006; Berrone et al. 2013). Furthermore, an image that aligns with government environmental policies helps secure more fiscal subsidies, thereby accelerating green innovation (Huang et al. 2019).

However, according to Tong et al. (2014), corporate transformation relies not only on substantive innovation that drives internal technological progress but also on external incentives, which may lead to the adoption of strategic innovation for additional benefits. Unlike transformations based on substantive innovation, those driven by strategic innovation emphasize quantity over quality, serving primarily promotional and greenwashing purposes. Consequently, a company’s actual environmental contributions often diverge from its claims, thereby undermining long-term development and market value. The Oxford Dictionary defines greenwashing as an organization’s attempt to create an environmentally responsible image by disseminating false or misleading information, even when such communications lack substantiation or intentionally obscure the truth (De Freitas Netto et al. 2020). Delmas and Burbano (2011) noted that an increasing number of companies resort to deceptive publicity or labeling—exaggerating or fabricating their environmental performance, products, or services—to achieve a greenwashing effect, which severely erodes consumer and investor trust. Walker and Wan (2012) further demonstrated that superficial greenwashing can harm a firm’s financial performance. Thus, although previous studies have differentiated between substantive and strategic green innovation paths (Chen 2008; Schiederig et al. 2012), discussion from the perspective of corporate environmental publicity remains limited.

An empirical study of Chinese listed companies from 2008 to 2020 reveals that corporate environmental publicity accelerates green innovation, though the primary path is strategic rather than substantive innovation—a finding that remains robust after applying the difference-in-differences (DID) method, excluding special samples, and performing placebo tests, among other robustness checks. Furthermore, considering that both internal and external factors may influence the choice of green innovation paths, we conducted heterogeneity analyses at the macro, market, and micro levels. Specifically, the analyses show that at the micro level, environmental publicity in heavily polluting firms hinders substantive innovation; in the market context, companies with ISO14001 certification tend to pursue substantive innovation; and with greater government intervention, firms receiving more subsidies exhibit higher levels of substantive innovation.

The potential innovations of this paper are manifested in three distinct aspects: Firstly, by analyzing environmental publicity in firms from emerging countries, we explored how corporate environmental publicity differently impacts green innovation. Unlike previous studies, which predominantly highlight the positive effects of corporate green development publicity (Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez 2009; Dangelico and Pujari 2010; Bai and Lyu 2023), this paper uncovers the speculative and strategic activities prevalent in emerging markets, providing substantial evidence of the promotional strategies employed by these companies about green development. Secondly, this research categorizes corporate green innovation activities into “substantial” and “strategic” types—the former being of higher value and transformative significance, serving as a critical driver of a company’s core green competitiveness, while the latter typically employed to meet short-term stakeholder needs, often at the expense of resource utilization and environmental degradation. From this perspective of structured differences, we reveal corporate environmental publicity’s varied roles and limitations in innovation activities. This study also verifies the paradox observed in capital markets: while enterprises demonstrate pronounced enthusiasm for verbal environmental commitments, their actual performance in energy conservation and emission reduction remains suboptimal. Finally, this paper constructs a systematic mechanism analysis framework. Starting from the classical economic perspectives of “signaling”, “moral hazard” and “stakeholder”, it integrates analysis of the specific mechanisms through which corporate environmental publicity impacts green innovation activities. This study enriches the understanding of how corporate environmental publicity affects green innovation within the context of emerging markets. Furthermore, it provides empirical insights to assist policymakers and business managers in promoting sustainable green development within corporations.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows: the second section encompasses a literature review, theoretical framework and hypothesis development; the third section introduces relevant data, variables, and research design; the fourth section displays the benchmark regression results, robustness tests, mechanism analysis and heterogeneity study; the fifth and final section proffers conclusions and recommendations.

Literature review, theoretical framework, and hypothesis development

Green innovation

Green transition refers to promoting new production methods and technological advancement through green innovation activities aimed at alleviating environmental issues such as pollution and resource overexploitation (Nidumolu et al. 2009; Schiederig et al. 2012). Green innovation primarily includes product, process, marketing, and organizational innovation, spanning areas from goods and services to production processes, sales channels, and management strategies (Horbach et al. 2012). With the rising global environmental awareness (Escario et al. 2022; Lou and Li 2023), green transition and its innovation activities are increasingly recognized as vital pathways to achieving the dual objectives of environmental protection and economic growth, garnering significant academic attention (Tariq et al. 2017; Chuang and Huang 2018).

Existing literature predominantly explores the positive impacts of green transition on enterprises, particularly in the manufacturing sector (Takalo and Tooranloo 2021). Research indicates that green innovation facilitates sustainable development and drives economic growth by opening new markets, enhancing competitiveness, and improving efficiency (Porter and Van der Linde 1995; Ghisetti and Rennings 2014; Vasileiou et al. 2022). Moreover, green innovation yields substantial environmental benefits, such as reduced emissions, decreased resource consumption, and minimized waste generation (Horbach 2008; Dangelico and Pujari 2010).

However, green innovation does not always yield positive outcomes. Some enterprises may resort to strategies such as greenwashing by issuing insubstantial environmental claims to secure short-term advantages, thereby eroding consumer trust and undermining policy effectiveness. Drawing on signaling theory (ST), Lyon and Maxwell (2011) observed that when environmental claims lack substance, they damage market credibility and hinder the dissemination of genuine green technologies. Similarly, Delmas and Burbano (2011) argued that lax regulatory environments and enforcement uncertainties encourage firms to adopt superficial greenwashing tactics to avoid the high costs of genuine green innovation, ultimately undermining consumer and investor confidence and impeding substantive innovation.

The drivers of green innovation are multifaceted. Internal factors include organizational culture, technological capabilities, and asset scale (Chen et al. 2006; Ghisetti et al. 2015), while external influences encompass regional characteristics, local regulatory environments, collaborations with external partners, and government support (Triguero et al. 2013; Cainelli et al. 2015). Previous research has shown that enterprises face challenges in resource allocation and balancing stakeholder interests when devising green innovation strategies. For example, Bansal and Roth (2000) noted that corporate green practices are often shaped by stakeholder demands, requiring firms to align their decisions with policy mandates while meeting the expectations of investors, consumers, and other stakeholders. It aligns with the core premise of stakeholder theory (SHT), which asserts that green innovation efforts must consider multiple interests rather than solely focusing on shareholder value maximization.

The concept of moral hazard (MH) in information asymmetry underscores that the effective integration of policy incentives with regulatory enforcement is crucial for guiding firms’ strategies. When governments provide subsidies or other forms of support without strict enforcement, moral hazard arises. Arrow (1963) noted that under information asymmetry, regulated parties may engage in opportunistic behavior; similarly, Laffont and Martimort (2009) argued that when principals cannot fully monitor agents, the latter may reduce efforts or inflate costs. In situations of weak enforcement, firms tend to opt for low-cost, superficial environmental measures to meet compliance rather than invest in high-cost, substantive green R&D, thereby undermining policy effectiveness and efficiency in resource allocation. Additionally, Triguero et al. (2013) found that in environments with weak local regulation and minimal stakeholder pressure, firms favor short-term strategies over long-term green technology R&D. This highlights the opportunistic tendencies in corporate green innovation and emphasizes the need to improve policy design and strengthen enforcement to mitigate moral hazard and promote sustainable, substantive green innovation.

In recent years, the intensification of global environmental challenges has made corporate environmental attitudes a key focus of academic attention. Previous studies have found that corporate environmental awareness and publicity practices significantly enhance innovation activities (Hermundsdottir and Aspelund 2021), yet systematic research on their differential effects on green innovation pathways remains scarce. Some studies indicate that corporate environmental attitudes are constrained by policy and stakeholder demands (Bansal and Roth 2000; Delmas and Toffel 2008) and influenced by information asymmetry, leading to trade-offs among various innovation pathways. Although firms may use green innovation to signal environmental responsibility and satisfy stakeholder expectations, such behavior often manifests as short-term signaling at the expense of long-term technological capability building. These findings provide a theoretical basis for further exploring the impact of corporate environmental publicity on diverse green innovation modes.

Corporate environmental publicity

Global environmental crises have profoundly affected the natural world, evident in resource depletion, pollution, and climate change, while also presenting both challenges and opportunities for businesses. How companies perceive environmental responsibility and implement effective strategies has become a key determinant of their financial performance. On one hand, firms that adopt proactive environmental strategies tend to achieve superior financial performance (Orlitzky et al. 2003). Their strong focus on environmental issues leads to cost savings and competitive advantages (Ameer and Khan 2023), while innovative green marketing and publicity enhance environmental awareness among younger consumers, creating new opportunities for sustainable growth (Prieto-Sandoval et al. 2022). On the other hand, such proactive strategies may incur higher investment costs and increased management complexity, potentially undermining financial performance (González-Benito and González-Benito 2005).

Corporate environmental publicity is driven not only by self-interest but also by the influence of external stakeholders. According to SHT, companies must address the diverse demands of policymakers, industry associations, the public, and investors (Freeman 2010). Government regulations often compel firms to disclose environmental issues to meet required standards, and Bansal and Roth (2000) noted that ecological concerns frequently prompt industry associations to demand environmental commitments or reports. Furthermore, Delmas and Toffel (2008) found that public and media pressure significantly influences corporate environmental reporting, especially in societies where green issues receive considerable attention, while Flammer (2013) highlighted the pivotal role of investors’ ecological awareness in shaping corporate social responsibility reports and environmental policy statements. Through environmental publicity, companies signal their commitment to sustainability and bolster investor confidence in their long-term development. However, the effectiveness of such signaling depends on the authenticity and transparency of the information conveyed; if driven primarily by strategic considerations rather than substantive innovation, it may erode stakeholder trust in the firm’s environmental commitments, underscoring the challenge posed by information asymmetry.

Corporate innovation is a key driver of competitive advantage (Mendoza-Silva, 2021), and sustainable innovation is positively associated with enhanced competitiveness (Hermundsdottir and Aspelund, 2021). Studies reveal that the technological capabilities fostered by environmental publicity and policy disclosures can effectively stimulate environmental innovation (Horbach, 2008; Bai and Lyu, 2023). However, Wu et al. (2020) highlighted that an excessive focus on environmental responsibility may adversely affect innovation performance, a phenomenon particularly evident in apparent firms. Kuk et al. (2005) further observed that underperforming firms often emphasize environmental responsibility strategies to compensate for their lack of technological innovation capabilities. In contrast, high-performing firms typically drive substantive transformation through advancements in technological capabilities and competitiveness rather than relying on environmental policy statements.

In summary, the connection between a business’s environmental publicity and green innovation has always been a hot topic for scholars. Still, there is currently no consensus on their promoting or inhibiting effect. At the same time, few existing studies have explored the impact of corporate environmental publicity on the innovation level from the perspective of green innovation. This paper attempts to fill this gap in the literature by constructing a theoretical framework of corporate environmental publicity and green innovation.

Theoretical framework and hypothesis development

Theoretical framework between corporate environmental publicity and green innovation

In asymmetric markets, firms with an informational advantage can significantly influence the decision-making of other market participants by transmitting credible signals to those with less information (Spence 1973). Based on ST, firms communicate their environmental commitments through environmental publicity to gain market recognition and competitive advantage, embodying a classic example of signaling behavior (Delmas and Toffel 2008). However, intense market competition often distorts this process, intensifying motives for greenwashing. Under such circumstances, firms may adopt short-term strategies, focusing on superficial green innovation to cater to market and investor expectations regarding their environmental reputation while maximizing resource efficiency (Delmas and Burbano 2011).

Simultaneously, SHT offers a multifaceted perspective on how firms balance external pressures and internal resource allocation in conditions of information asymmetry (Freeman 2010). Through environmental publicity, firms signal an environmental commitment to consumers and investors and address the expectations of governments, non-governmental organizations, and other stakeholders (Nguyen-Viet 2023). However, due to stakeholders’ limited ability to discern a firm’s actual environmental practices, companies may exploit information asymmetry to cultivate a green reputation and secure external support, such as government subsidies. The allocation of such subsidies relies on the “credible” green image portrayed by the firm’s publicity efforts, while stakeholders’ capacity to monitor actual innovation quality and resource use remains limited (Bi et al. 2024). Against this backdrop, firms are incentivized to prioritize more perceptible but superficial green innovations (e.g., strategic innovations) over substantive innovations with long-term value to maintain their reputation and satisfy external short-term demands.

Furthermore, MH sheds light on firms’ opportunistic behaviors under information asymmetry and regulatory inadequacies (Holmström 1979). Governmental and external regulatory bodies often face challenges in fully understanding internal corporate operations and effectively constraining their actions. It allows firms to channel subsidies into low-cost, superficial green innovation projects rather than genuine, deep-green innovations. To better align with external expectations, firms may manipulate R&D activities, exaggerating green innovation expenditures or selectively disclosing outcomes to project a positive environmental image and secure additional resources (Ketata et al. 2015). Such actions deviate from the original intent of policies and distort the rational allocation of innovation resources.

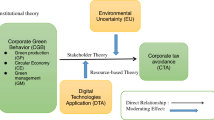

In summary, ST, SHT, and MT collectively illuminate the theoretical mechanisms by which corporate environmental publicity influences green innovation. Under conditions of information asymmetry, ST focuses on how firms convey credible signals through publicity, SHT emphasizes how firms use publicity to balance multi-party interests and gain external support, and MH highlights how firms exploit regulatory loopholes for resource misallocation and opportunistic behavior. Together, these frameworks underpin this study’s theoretical foundation. Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical framework. Building on this foundation, we propose research hypotheses as follows:

H1: Corporate environmental publicity effectively increases the company’s green innovation output, but this improvement has strong strategic characteristics, with output concentrated on strategic green patents.

Corporate environmental publicity, greenwashing, and green innovation based on ST

Under conditions of information asymmetry, based on the principles of ST (Spence 1973), firms can use environmental publicity to transmit “green” signals to the market, enhancing recognition and trust in their environmental commitments. As an observable signal, environmental publicity reduces stakeholders’ uncertainty regarding corporate environmental performance (Delmas and Toffel 2008). However, the effectiveness of signaling depends on the authenticity and transparency of the information conveyed. When external environmental pressures intensify—such as stricter regulations and heightened public environmental awareness—firms often increase the intensity of their publicity to meet the multifaceted expectations of “government-public” interactions (Marquis et al. 2016). In such scenarios, firms may strategically exploit signaling mechanisms, exaggerating their environmental performance to avoid the high costs of substantive environmental improvements (Nyilasy et al. 2014). Particularly under limited resources and intense market competition, firms are inclined to enhance their publicity efforts rather than implement in-depth improvements, reducing costs and increasing market recognition (Delmas and Burbano 2011). Consequently, increased environmental publicity intensity often coincides with a heightened propensity for greenwashing, representing a “rational” choice for cost-effective signaling.

Driven by greenwashing motives, firms may shift progressively from substantive green innovation to strategic green innovation. Strategic green innovations, such as green utility model patents, offer low-cost and low-risk advantages that quickly bolster perceived environmental performance and enhance external recognition of corporate green initiatives. In contrast, substantive green innovations require sustained high investment and entail significant risks, making them less appealing for firms seeking to elevate brand image and market performance in the short term (Li et al. 2023). This tendency is particularly pronounced in emerging economies, where information asymmetry is more severe, and stakeholders struggle to accurately assess corporate green innovation’s actual value. In such contexts, firms prioritize increasing strategic green innovations to maximize short-term green returns. However, this behavior undermines investments in substantive green innovation, impeding genuine technological transformation and the advancement of environmental management capabilities (Delmas and Burbano 2011). Building upon the analysis above, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1a: Increased intensity of corporate environmental publicity leads to a rise in greenwashing motives, driving companies to focus more on increasing strategic green patents.

Corporate environmental publicity, corporate reputation, and green innovation based on ST and SHT

The intensity of corporate environmental publicity is crucial for shaping a positive reputation. In markets characterized by information asymmetry, firms frequently and impactfully use publicity to transmit green signals, thereby enhancing their image and credibility as socially responsible and environmentally conscious entities (Spence 1973; Mukonza and Swarts 2020; Nguyen-Viet 2023). This enhanced image attracts a broader base of consumers and investors, enabling firms to gain a competitive edge. By consistently promoting their environmental stance, firms reinforce their green identity, augmenting brand equity and market acceptance. The strong positive reputation built through extensive publicity secures significant support and resources in both policymaking and market competition, which aligns with SHT’s emphasis on addressing diverse stakeholder demands (Freeman 2010).

However, under reputation pressure, companies often adopt strategic green innovation to preserve a favorable image. This strategy aligns with ST theory, wherein firms use low-cost, easily quantifiable outputs—such as green utility model patents—to project an illusion of “green prosperity” (Bi et al. 2024). Owing to their low risk and rapid returns, strategic innovations become the primary means of meeting short-term stakeholder expectations (Li et al. 2023; Peng et al. 2024). In contrast, substantive green innovation, which demands long-term investment and carries higher risks, frequently fails to boost market image and short-term performance (Nyilasy et al. 2014). From a corporate governance perspective, board decisions and incentive mechanisms are pivotal—with long-term oriented management more likely to support substantive innovation for technological breakthroughs (Shah and Ivascu 2024; Xu et al. 2024). Yet, intense reputation pressures combined with short-term incentives lead firms to prioritize quantity over quality, neglecting long-term environmental benefits and reducing investment in substantive technologies, thereby hindering genuine technological transformation and environmental management improvement (Delmas and Burbano 2011). Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1b: Increased intensity of corporate environmental publicity enhances the company’s positive reputation, and to maintain this reputation level, companies often respond by increasing the output of strategic green patents.

Corporate environmental publicity, fiscal environmental subsidies, and green innovation based on SHT and MH

According to SHT, corporate environmental publicity enhances a firm’s green image, enabling it to better meet the environmental responsibility expectations of governments, the public, and other stakeholders, thereby increasing the likelihood of securing fiscal subsidies (Han et al. 2024). Governments and relevant institutions typically prioritize firms with strong ecological reputations to drive green development (Li et al. 2023). Through environmental publicity, companies communicate their commitment to sustainable development and build a positive social responsibility image, further solidifying their status as “environmental pioneers” in the market. In this process, environmental publicity is crucial for corporate-government interaction, aligning a firm’s image with policy objectives and enhancing competitiveness in resource allocation (Opoku et al. 2023). Moreover, extensive environmental publicity significantly boosts a firm’s bargaining power in securing fiscal subsidies by garnering recognition and support from governments and other stakeholders, thereby enhancing market standing and providing additional funding for green innovation initiatives in the short term.

However, from a moral hazard perspective, the allocation of fiscal and environmental subsidies may trigger opportunistic behaviors that undermine resource efficiency (Holmström 1979; Zhu et al. 2019). With governments struggling to fully verify environmental practices, firms may exaggerate green performance to secure extra subsidies. Once granted, companies tend to adopt low-cost, low-risk strategic green innovations to meet quantifiable performance targets (Ren et al. 2021), which, though quickly satisfying evaluations, typically lack technological breakthroughs and long-term benefits. Moreover, limited fiscal resources lead firms to underinvest in high-cost, long-term substantive innovations while pursuing short-term goals, thereby weakening intrinsic green innovation and increasing subsidy reliance, which hampers core green technological competitiveness. Consequently, while environmental subsidies can stimulate short-term green innovation, overreliance on strategic approaches may hinder firms’ long-term green transition. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1c: Increased intensity of corporate environmental publicity leads to increased environmental subsidies the company receives, with government subsidy interventions often being distorted, thereby triggering an increase in strategic green patents.

Corporate environmental publicity, R&D manipulation, and green innovation based on MH

According to moral hazard, when external regulation and information access are incomplete, firms may exploit information asymmetries and supervisory gaps to pursue maximal benefits (Holmström 1979). In environmental publicity, firms enhance their green image to attract market and policy support, although they face heightened external expectations and oversight (Du 2015). To meet the demands for green innovation from governments, the public, and other stakeholders, firms may exaggerate R&D investments or modify their R&D content, using fabricated or inflated signals to mask deficiencies in substantive green innovation. Such R&D manipulation includes inflating reported R&D expenditures, selectively disclosing outcomes, and prioritizing low-end green projects that are easily recognized by the market while avoiding complex, high-risk core technology development (Liu et al. 2021). For example, companies may repackage routine improvements as green innovation or allocate R&D budgets to low-tech, short-cycle projects to quickly satisfy external scrutiny. Although this behavior may enhance a firm’s market reputation in the short term, it distorts resource allocation efficiency and impedes technological breakthroughs.

R&D manipulation disrupts the progress of green innovation by diverting scarce research resources from core areas and weakening a firm’s green competitiveness. Under conditions of information asymmetry and insufficient oversight, firms tend to manipulate R&D for short-term gains. Specifically, after intensifying environmental publicity, companies mainly adopt easily demonstrable, low-cost, and low-risk strategic innovations—such as design or utility model patents—to meet government assessments and public expectations (Ketata et al. 2015). This manipulation enhances the visibility of green innovation outcomes, boosting a firm’s reputation and market competitiveness, but often at the expense of high-tech, long-term substantive innovation (Liu et al. 2021). Insufficient investment in core technologies exacerbates resource misallocation, as strategic innovations mask deficiencies in substantive innovation, hindering deep technological breakthroughs and undermining long-term green competitiveness and sustainability. Thus, R&D manipulation not only reflects firms’ attempts to evade external pressure and pursue short-term gains but also deepens imbalances in green innovation and technological accumulation. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1d: Increased intensity of corporate environmental publicity leads to increased corporate R&D manipulation activities, disrupting the normal trajectory of innovation and triggering an increase in strategic green patents.

Data and methodology

Sample and variables

Our study started with a sample of Chinese A-share listed companies from 2008 to 2020. To ensure the validity of the data, we carried out several steps of data processing: We excluded financial companies, special treatment companies, particular transfer companies, and observations with missing data. Moreover, all continuous variables were winsorized at the 1% and 99% levels. Ultimately, we were left with 22014 observations from 2960 companies. To determine the companies’ level of environmental publicity, we used text mining tools in Python to extract the relevant information from their annual reports. The data on green patent grants were obtained from the Chinese Research Data Services (CNRDS) database. In contrast, other financial data were obtained from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database.

According to the studies by Hao and He (2022) and Jiang and Bai (2022), the degree of green innovation can be replaced by the number of green patents, which is measured by the number of green patents granted (GTI-T). This paper further divides the green patents into invention patents (GTI-I) and green utility model patents (GTI-U) as necessary. Jiang and Bai (2022) suggest that, typically, granting invention patents indicates significant technological progress and high practical value. Hence, the number of such patents can be used to measure substantive innovation. Meanwhile, utility model patents have less stringent licensing requirements, lower technological complexity, and reduced costs, making them a common proxy for strategic innovation. The number of patents is transformed by adding one and taking the natural logarithm.

The key explanatory variable in this study is corporate environmental publicity (CEP). Gao et al. (2024), Guo et al. (2024), and Zhang et al. (2024) provided a framework for quantifying CEP, which was followed in this paper. Firstly, a raw text lexicon was developed by grouping keywords related to corporate environmental publicity in relevant government documents. We expanded the lexicon with the help of the Python “Synonymous” extension package to reduce the potential for omitting appropriate environmental words and broaden the environmental text thesaurus. Secondly, the Python Jieba word-splitting package was utilized to identify the keywords in the annual reports of the sample companies with high correlation coefficients with the keywords in the thesaurus, and these were included in the expanded environmental thesaurus. Thirdly, the frequency of the environmental keywords was calculated by matching and collecting them in the annual reports of the sample firms and aggregated to quantify the extent of the firms’ environmental publicity.

Methodology

To examine the relationship between corporate environmental publicity and green innovation, we used the results of the Hausman testFootnote 1 to design the following fixed-effects model.

Where i and t represent the enterprise and year, respectively, the dependent variable GTI represents the level of green innovation by the enterprise. GTI is reflected in three aspects: overall green innovation (GTI-T), substantive green innovation (GTI-I), and strategic green innovation (GTI-U). Given the time lag between patent application and grant, we follow the approach of Ding et al. (2022) and apply a two-period lead to GTI. The core explanatory variable CEP represents the degree of corporate environmental publicity. To control for other factors, we include a series of control variables, following the research of Jiang and Bai (2022), including total assets (Size), leverage (Lev), return on assets (Roa), firm age (Age), the growth rate of total assets (Growth), operating cost ratio (OD), the shareholding ratio of the top 1 shareholder (Top1), management shareholding ratio (Mana), financial constraint (SA), and cash ratios (Cash). _cons represents the intercept term, while Year FE and Firm FE represent the year and individual fixed effects, respectively, and ε defines the error term.

The definitions and descriptive statistics of the variables are shown in Table 1. The descriptive statistics generated a dataset comprising 22014 “firm-year” observations. The distribution of corporate green innovation activities demonstrates a decreasing trend with the increasing difficulty of innovations. Specifically, for substantial green innovations (GTI-I), the average value is 0.133 with a maximum of 2.197; for strategic green innovations (GTI-U), the average value is 0.239 with a maximum of 2.773. This study posits that the diminishing quantity of outputs as the complexity of patent innovations increases aligns well with current practical scenarios. It can also be observed that all variance inflation factors (VIF) are less than 10, indicating the absence of severe multicollinearity issues among the variables.

Empirical results

Baseline regression tests

The baseline regression results presented in Table 2 reveal the impact of corporate environmental publicity (CEP) on green innovation, demonstrating a significant overall positive effect on green innovation activities (GTI-T). However, this influence is markedly differentiated across various levels of green innovation. While environmental publicity exerts a statistically significant positive effect on strategic green innovation, it shows no substantial practical impact on substantive green innovation. This conclusion holds regardless of whether control variables are included, providing empirical support for H1.

From the perspective of ST, CEP is a key indicator of a firm’s commitment to sustainable development, enhancing reputation by earning the trust of consumers, investors, and governments. However, under conditions of information asymmetry, firms may exaggerate or selectively disclose “green” practices, engaging in greenwashing. While CEP can boost market recognition and attract valuable resources in the short term, it may also lead firms to favor superficial, strategic green innovations—such as design or utility model patents—over substantial, high-tech projects. Moreover, according to SHT, corporate environmental publicity bolsters corporate reputation and aligns with stakeholders’ expectations, particularly policymakers. By showcasing a company’s green image and environmental commitments, CEP increases the likelihood and scale of government environmental subsidies. As stakeholders increasingly prioritize environmental responsibility, governments may respond by providing financial support or preferential policies to companies perceived as environmentally proactive. However, this subsidy-driven incentive, rooted in stakeholder dynamics, may disproportionately favor companies with visible “green” achievements over those genuinely investing in technologically intensive green breakthroughs. Finally, from a moral hazard perspective, once a firm secures environmental subsidies, it may face loosened oversight or misaligned incentives, prompting opportunistic behaviors such as R&D manipulation. Specifically, firms may inflate R&D expenditures or selectively divert resources to low-cost, easily demonstrable innovation projects to meet short-term expectations. This not only diverts investment from substantive green innovations but also undermines the long-term development of genuine green innovation capabilities.

In summary, environmental publicity, by shaping stakeholder perceptions and behaviors, fosters the superficial prosperity of green innovation in the short term. Yet, information asymmetry and imbalanced incentives also drive firms toward strategic innovation pathways, thereby hindering the more profound development of substantive innovation. This process has significant economic and environmental implications, enhancing a firm’s market image and short-term competitiveness while sowing the seeds for inadequate long-term green technological capabilities.

Robustness and endogeneity tests

To address endogeneity concerns, we conducted a series of robustness and endogeneity tests on the conclusions in Table 2, including the propensity score matching (PSM) method, poisson fixed-effects model, replacement of core variables, difference-in-differences model, exclusion of special samples, placebo test, instrumental variable method, and reverse causality test. The results are presented in Appendix A (Tables A1 to A7). The findings from these tests confirm the conclusions in Table 2, suggesting that the main conclusions of this paper are robust and reliable.

Mechanism analysis

This paper examines the constructs of “signaling”, “moral hazard” and “stakeholder” as analytical frameworks. These three perspectives are employed to investigate key issues such as greenwashing, corporate reputation, environmental subsidies, and R&D manipulation. However, the above conjectures have not been empirically corroborated. To this end, we further consider the impact of corporate environmental publicity (CEP)-induced changes in mechanism variables on green innovation (GTI) based on the test of “CEP→Mechanism Variable (MV)”.

For testing the “CEP→Mechanism Variable (MV)” step, we set up the following Eq. (2):

Where MV denotes a series of mechanism variables, including greenwashing (GW), corporate reputation (CR), fiscal environmental subsidy (FES), and R&D manipulation (RDM). Controls denotes a series of control variables, which are consistent with the definition of Eq. (1). The residual term \({\pi }_{i,t}\) represents the error between the observed value and the fitted value of MV:

Based on this, we construct a “pseudo” regression model of the mechanism variable that excludes the influence of CEP:

In Model (4), although the influence of CEP on the mechanism variable is removed, it still contains the potential impact of CEP on MV that has not been captured. At the same time, since Model (2) already treats CEP as an explanatory variable, \({\pi }_{i,t}\) has already excluded the effect of CEP on MV. Therefore, by combining Eq. (5) with Eq. (3), we obtain:

Here, \(\varDelta \overline{M{V}}_{i,t}\) represents the “net” effect of CEP on the mechanism variable MV and will be used as the core explanatory variable in the regression analysis of the dependent variable GTI:

In Model (7), the economic significance of the regression coefficient θ1 represents the further impact of the net effect of the mechanism variable induced by CEP on the dependent variable GTI.

Specifically, the setting of the greenwashing variable references the methods of Chen et al. (2024), Li and Chen (2024), and Yin and Yang (2024), using the difference between standardized ESG disclosure scores and standardized ESG performance scores to measure the extent of a company’s greenwashing. The ESG disclosure scores are sourced from the CNRDS database, which is based on international ESG disclosure standards such as ISO 26000, GRI Standards, and SASB Standards, as well as prominent domestic and international ESG databases. It also incorporates relevant policies on ESG disclosure in China to create a unique ESG scoring system for Chinese enterprises. The ESG performance scores are derived from the Wind database, reflecting the Huazheng Index ESG ratings, which assess corporate responsibility performance in environmental, social, and governance aspects. These ratings are segmented into nine levels: AAA, AA, A, BBB, BB, B, CCC, CC, and C. Companies are scored from 9 to 1 based on their ESG ratings from highest to lowest, with the average rating data per quarter serving as the annual Huazheng Index ESG rating for the company. This data is widely utilized in academic circles (Chen et al. 2024; Li and Chen 2024; Yin and Yang 2024) and is regarded as a reliable reflection of a company’s actual environmental performance (Liao et al. 2023). The specific formula for the greenwashing index (GW) is as follows:

In establishing the reputation variable, Milbourn (2003) posits that CEOs frequently mentioned in public media or newspapers generally possess superior personal reputations compared to those less often cited. Weng and Chen (2017) define a CEO’s reputation as better when there is abundant news coverage related to the CEO. Following the scholarly approach of these academics, we have constructed a corporate reputation indicator. Considering that news reports can be positive, neutral, or negative, it is crucial to account for the adverse effects of negative coverage on corporate reputation. Therefore, we ultimately define corporate reputation (CR) as the proportion of non-negative news coverage relative to the total media reports.

Regarding the measurement of environmental subsidies, this study adopts the methodology of Guo et al. (2024), using the intensity of government environmental subsidies relative to core business revenue as a proxy variable.

For the setting of leverage manipulation, following the approach of Mao et al. (2023), we have developed a research and development manipulation (RDM) indicator, where the presence of R&D manipulation behavior is denoted as 1, otherwise 0. Specifically, under the “Management Measures for the Recognition of High-Tech Enterprises,” if a company’s annual sales revenue falls below 50 million, between 50 million and 200 million, or above 200 million, and the intensity of R&D investment is above 6%, 4%, and 3% respectively, these enterprises benefit from a preferential corporate income tax rate of 15%, compared to the standard rate of 25%. In line with Mao et al. (2023), we set a critical threshold of 1%. If a company’s annual sales revenue falls into the categories of below 50 million, between 50 million and 200 million, or above 200 million, with R&D investment intensities respectively within the ranges of [6%, 7%], [4%, 5%], and [3%, 4%], we consider that the enterprise is engaged in R&D manipulation.

In Table 3, the study initially examines how corporate environmental publicity influences greenwashing motives and subsequently impacts green innovation. Column (1) demonstrates that an increase in the intensity of corporate environmental publicity significantly enhances greenwashing motives. Furthermore, an escalation in greenwashing motives leads companies to focus more on short-term performance within the green sector. Empirical results indicate that although an increase in greenwashing motives significantly elevates the overall level of green innovation, this growth predominantly relies on strategic green innovation, creating an illusion of flourishing green activities, thus supporting H1a of this paper.

In Table 4, we focuse on corporate reputation to identify mechanisms affecting green innovation. It has been found that corporate environmental publicity significantly boosts the level of a positive corporate reputation. Moreover, an increase in corporate reputation paradoxically imposes excessive short-term expectations on companies, leading them to prioritize the quantity of green output over quality improvements. The empirical regression results show that while corporate reputation level can lead to an increase in strategic green innovations, it does not statistically enhance substantial green innovation, lending empirical support to H1b of this study.

From Tables 5 to 6, we explore the environmental subsidy mechanism and the research and development manipulation mechanism, respectively. In Table 5, this paper examines how corporate environmental publicity affects environmental subsidies and, consequently, green innovation. Column (1) indicates that an increase in the intensity of corporate environmental publicity significantly boosts the intensity of environmental subsidies received by the company. Further, while the enhancement in environmental subsidies can lead to an increase in low-quality strategic green innovations, it fails to significantly affect substantial green innovation, resulting in an overall growth that lacks sufficient value, consistent with H1c of this paper.

Table 6 illustrates that this paper conducts mechanism identification tests within the “moral hazard” framework based on R&D manipulation, primarily examining how corporate environmental publicity influences R&D manipulation and thereby affects green innovation. The study finds that corporate environmental publicity significantly intensifies R&D manipulation—including actions such as adjusting R&D budgets and selectively choosing projects—which exhibit a strong short-term bias. As a consequence, firms tend to prioritize green innovation projects that yield rapid results and are easy to publicize over forward-looking, high-innovation projects. Empirical evidence shows that while R&D manipulation significantly enhances strategic green innovation, it has no significant impact on substantive green innovation. Although overall innovation increases statistically, it does not translate into effective core competitiveness, thereby empirically supporting H1d.

Heterogeneity analysis

The prior discussion on the relationship between corporate environmental publicity and green innovation is grounded in a comprehensive sample framework. However, factors such as the micro-nature of firms, market management standards, and variations in government intervention exert different tractive effects on the green innovation pathway of firms (Hojnik and Ruzzier 2016; Guo et al. 2024; Lai et al. 2023). To further unravel the heterogenous impacts caused by corporate environmental publicity on green innovation within diverse frameworks and to discuss more comprehensively the interaction mechanism between the two variables, we segmented the sample based on micro-nature into heavily polluting and lightly polluting firms, according to market management standards into firms that have obtained ISO14000 certification and those that haven’t; and gauge the influence of macro-factors on corporate green initiatives based on the intensity of government subsidies. The detailed findings are explicated henceforth.

Heavily polluting firms

At the micro level, we have specifically examined the heterogeneous impacts on green innovation engendered by the environmental publicity behaviors of heavily polluting firms, as depicted in Table 7. Here, HPE is a dummy variable, taking 1 for heavily polluting firms and 0 otherwise (Lai and Zhang 2022)Footnote 2. The focus is on the coefficient of the interaction effect of CEP × HPE. As can be discerned from columns (1), (2), and (3), the environmental publicity of heavily polluting firms fails to enhance the overall level of green innovation (it does not pass the significance test), and their green publicity behaviors could even hinder substantive innovation (the impact coefficient of GTI-I is negative and significant at the 5% level). In comparison, strategic innovation continues to benefit from environmental publicity behaviors (the impact coefficient of GTI-U is positive and practical at the 10% level).

A plausible explanation is that heavily polluting firms are generally larger and require substantial investment to retrofit emission reduction facilities, thereby raising the barriers to green innovation such that costs may outweigh benefits (Hu et al. 2021; Xie et al. 2022). Under these conditions, heavily polluting firms tend to showcase strategic innovation to bolster their environmental image, as such innovation is lower in cost, easier to implement, and more likely to attract public support and government subsidies. Consequently, driven by external incentives, they may reduce investments in substantive innovation once the benefits of strategic innovation are realized.

ISO14001 market certification

At the market level, this paper verifies the heterogeneous impact of ISO14001 certification on corporate green innovation. The certification of an environmental management system is conducted by a third-party institution based on publicly available ISO14000 series standards, through which suppliers are evaluated. Suppliers meeting the standards receive certification, which is registered and publicized to attest to their ability to provide products or services in accordance with established environmental standards and legal requirements. Table 8 presents the related results, where ISO is a dummy variable (1 for certified firms, 0 otherwise). The coefficient of the CEP × ISO interaction indicates that enterprises with ISO14001 certification are more inclined to enhance their overall green innovation (with a positive and significant impact at the 5% level). This positive effect is mainly concentrated on substantive green innovation (GTI-I), while strategic green innovation (GTI-U) remains unaffected.

A plausible interpretation is that firms with ISO certification must have the capability to meet established standards and regulatory requirements, reflecting high-level internal environmental management that fosters a favorable institutional environment for green innovation (Khan and Johl 2020). In this context, a firm’s environmental publicity primarily aims to promote substantive innovation through advanced technology for competitive advantage, rather than merely pursuing superficial external benefits. Given the significant investment required for ISO certification and its limited three-year validity, if publicity were solely for external gains, firms would not endure such a cumbersome certification process. Consequently, their environmental publicity is driven by intrinsic factors, thereby promoting substantive green innovation.

Government subsidies

At a macro level, this study delves into the heterogeneous effects of government subsidy intensity on the relationship between corporate environmental publicity and green innovation, as presented in Table 9. Herein, Subsidy represents the intensity of government subsidies, defined as the proportion of government subsidies to operating income. As suggested by the coefficient of the interaction term CEP × Subsidy, the stronger the government subsidy intensity, the more influential the enterprise is in driving substantive innovation through environmental publicity (the coefficient of GTI-I is positive and significant at the 1% level). In contrast, no significant promotional effect on strategic innovation is observed (it does not pass the significance test).

A potential explanation for these results could be that although government subsidies do indeed play a role in propelling corporate green innovation (Hojnik and Ruzzier, 2016), the number of green innovation subsidies that do not distinguish types will not be substantial. As the intensity of offerings continues to rise, the government needs to conduct further scrutiny on corporate green innovation outcomes. The government would limit the subsidy amount for green patents of practical new types that bear low-value content, reallocating more funds to enterprises engaged in substantive innovation activities. Consequently, enterprises can only secure continuous large-scale government subsidies by making more substantial contributions while conducting environmental publicity, manifesting as the promotional effect of government subsidies on substantive innovation.

Regulatory distance

Following the approach of Zhong et al. (2025), the regulatory distance (Reg_Dis) is determined by the natural logarithm of the distance between the registered location of listed companies and the provincial ecological and environmental departments, as calculated by Baidu Maps. A higher Reg_Dis value indicates a greater distance between the company and the environmental department, resulting in a lower regulatory “deterrence” effect. The negative significance of the interaction term in Table 10 suggests that a smaller Reg_Dis can more actively promote substantive green innovation (GTI-I).

One plausible explanation is that a shorter regulatory distance enables more frequent, direct interactions between companies and regulators, intensifying regulatory pressure and prompting companies to provide practical information in their environmental publicity for effective oversight of green innovation. Substantive green innovation, which meets strict standards and aligns with societal needs, also exhibits a strong innovation-driven effect. Moreover, tighter regulatory proximity increases verification frequency and the risk of false claims, encouraging firms to boost credibility through substantive innovation. Additionally, a shorter geographical distance facilitates access to accurate policy guidance and technical support, thereby showcasing genuine technological progress and innovative outcomes in their environmental publicity.

Conclusions

This study investigates the role of corporate environmental publicity in facilitating green innovation among Chinese-listed companies from 2008 to 2020. Empirical findings indicate that CEP enhances overall green innovation, primarily by promoting strategic rather than substantive innovation. The mechanism validation indicates that the impact of CEP on substantive and strategic innovation is influenced by greenwashing incentives, reputation-driven motives, environmental subsidies, and R&D manipulation, which hinders the long-term enhancement of corporate competitiveness. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that heavily polluting industries tend to favor strategic innovation, whereas firms with ISO14001 certification or government subsidies are more likely to achieve substantive innovation. Based on these conclusions, we propose measures to strengthen CEP’s effect on promoting substantive innovation.

First, a robust disclosure and evaluation system for corporate environmental publicity should be established. Companies must transparently disclose accurate green innovation outcomes and technical details to ensure that the public and regulators receive correct information, thereby preventing false advertising and the proliferation of strategic patents. Third-party agencies should evaluate environmental publicity based on the substantiality, practicality, and environmental improvement of innovations and publish their findings, providing a basis for policy support and market recognition.

Second, the formulation and enforcement of environmental policies must be refined. More scientific, stable, and transparent policies can effectively motivate enterprises to pursue substantive green innovation. Therefore, the government should establish long-term, operable, and prudent environmental policies while strengthening enforcement and supervision to mitigate uncertainties and avoid frequent changes that adversely affect enterprises.

Third, the green innovation support system must be optimized. Given the high investments, extended return periods, and considerable technological and market uncertainties involved in green transformation, enterprises urgently require external support through measures such as tax incentives, subsidies, credit facilities, and intellectual property protection to reduce costs and risks while enhancing innovation efficiency. Additionally, they should strengthen cooperation with government, research institutions, industry associations, and social organizations to promote information sharing and technological interaction, thereby boosting green innovation capabilities.

The limitations of this paper lie in its exclusive focus on the substantial-strategic perspective of corporate environmental publicity’s effects and mechanisms, which—although vital for understanding its constraints and informing decision-makers—fails to address methods for mitigating its negative impacts. Empirical research on governance strategies is still insufficient and will be a key focus in future studies.

In future research, we will develop a comprehensive “internal-external” optimization framework to mitigate the adverse impacts of corporate environmental publicity on green innovation. This framework will optimize corporate management and incentive systems to neutralize negative drivers and ensure effective utilization of R&D resources, while guiding governments to design more effective environmental subsidy incentives to promote substantive green innovation. We envision that through such integrated internal-external collaboration, the adverse effects can be minimized or even transformed into a catalyst for substantive green innovation; however, this hypothesis requires further empirical validation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

After replacing GTI with GTI-T, GTI-I, and GTI-U in Model (1), the Hausman test results were 189.87, 89.74, and 177.16, respectively. These results indicate that the original hypothesis in favor of the random-effects model was rejected in all cases. Therefore, this paper adopts a fixed-effects model.

References

Aerts W, Cormier D (2009) Media legitimacy and corporate environmental communication. Account, Organ Soc 34(1):1–27

Ameer F, Khan NR (2023) Green entrepreneurial orientation and corporate environmental performance: A systematic literature review. Eur Manag J 41(5):755–778

Arrow KJ (1963) Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. Am Economic Rev 53(5):941–973

Bai X, Lyu C (2023) Environmental information disclosure and corporate green innovation: The moderating effect of formal and informal institutions. Sustainability 15(7):6169

Bansal P, Roth K (2000) Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Acad Manag J 43(4):717–736

Berrone P, Fosfuri A, Gelabert L et al. (2013) Necessity as the mother of ‘green’ inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strategic Manag J 34(8):891–909

Bi Q, Feng S, Qu T et al. (2024) Is the green innovation under the pressure of new environmental protection law of PRC substantive green innovation. Energy Policy 192:114227

Cainelli G, D’Amato A, Mazzanti M (2015) Adoption of waste-reducing technology in manufacturing: Regional factors and policy issues. Resour Energy Econ 39:53–67

Chen L, Ma Y, Feng, G, et al. (2024) Does environmental governance mitigate the detriment of greenwashing on innovation in China? Pacific-Basin Financ J 86:102450

Chen YS, Chang CH (2013) Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J Bus Ethics 114:489–500

Chen YS, Lai SB, Wen CT (2006) The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. J Bus Ethics 67:331–339

Chen YS (2008) The driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. J Bus Ethics 81:531–543

Cheng Z, Li L, Liu J (2019) The effect of information technology on environmental pollution in China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 26(32):33109–33124

Cho CH, Patten DM (2007) The role of environmental disclosures as tools of legitimacy: A research note. Account, Organ Soc 32(7-8):639–647

Chuang SP, Huang SJ (2018) The effect of environmental corporate social responsibility on environmental performance and business competitiveness: The mediation of green information technology capital. J Bus Ethics 150(4):991–1009

Dangelico RM, Pujari D (2010) Mainstreaming green product innovation: Why and how companies integrate environmental sustainability. J Bus Ethics 95:471–486

De Freitas Netto SV, Sobral MFF, Ribeiro ARB et al. (2020) Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environ Sci Eur 32(1):1–12

Delmas MA, Burbano VC (2011) The drivers of greenwashing. Calif Manag Rev 54(1):64–87

Delmas MA, Toffel MW (2008) Organizational responses to environmental demands: Opening the black box. Strategic Manag J 29(10):1027–1055

Ding N, Gu L, Peng Y (2022) Fintech, financial constraints and innovation: Evidence from China. J Corp Financ 73:102194

Du X (2015) How the market values greenwashing? Evidence from China. J Bus Ethics 128(3):547–574

Escario JJ, Rodriguez-Sanchez C, Valero-Gil J et al. (2022) COVID-19 related policies: The role of environmental concern in understanding citizens’ preferences. Environ Res 211:113082

Farza K, Ftiti Z, Hlioui Z et al. (2021) Does it pay to go green? The environmental innovation effect on corporate financial performance. J Environ Manag 300:113695

Flammer C (2013) Corporate social responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. Acad Manag J 56(3):758–781

Freeman RE (2010) Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge University Press

Gao X, Lai X, Tang X, Li Y (2024) Does environmental regulation affect corporate environmental awareness? A quasi-natural experiment based on low-carbon city pilot policy. Economic Anal Policy 84:1164–1184

Ghisetti C, Marzucchi A, Montresor S (2015) The open eco-innovation mode. An empirical investigation of eleven European countries. Res Policy 44(5):1080–1093

Ghisetti C, Rennings K (2014) Environmental innovations and profitability: How does it pay to be green? An empirical analysis on the German innovation survey. J Clean Prod 75:106–117

González-Benito J, González-Benito Ó (2005) Environmental proactivity and business performance: an empirical analysis. Omega 33(1):1–15

Guo C, Wang Y, Hu Y et al. (2024) Does smart city policy improve corporate green technology innovation? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. J Environ Plan Manag 6(67):1182–1211

Hadlock CJ, Pierce JR (2010) New evidence on measuring financial constraints: Moving beyond the KZ index. Rev Financial Stud 23(5):1909–1940

Han F, Mao X, Yu X et al. (2024) Government environmental protection subsidies and corporate green innovation: Evidence from Chinese microenterprises. J Innov Knowl 9(1):100458

Hao J, He F (2022) Corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance and green innovation: Evidence from China. Financ Res Lett 48:102889

Hartmann P, Apaolaza-Ibáñez V (2009) Green advertising revisited: Conditioning virtual nature experiences. Int J Advertising 28(4):715–739

Hermundsdottir F, Aspelund A (2021) Sustainability innovations and firm competitiveness: A review. J Clean Prod 280:124715

Hojnik J, Ruzzier M (2016) What drives eco-innovation? A review of an emerging literature. Environ Innov Societal Transit 19:31–41

Holmström B (1979) Moral hazard and observability. Bell J Econ 10(1):74–91

Horbach J (2008) Determinants of environmental innovation—New evidence from German panel data sources. Res Policy 37(1):163–173

Horbach J, Rammer C, Rennings K (2012) Determinants of eco-innovations by type of environmental impact—The role of regulatory push/pull, technology push and market pull. Ecol Econ 78:112–122

Huang Z, Liao G, Li Z (2019) Loaning scale and government subsidy for promoting green innovation. Technol Forecast Soc Change 144:148–156

Hu G, Wang X, Wang Y (2021) Can the green credit policy stimulate green innovation in heavily polluting enterprises? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Energy Econ 98:105134

Jiang L, Bai Y (2022) Strategic or substantive innovation? The impact of institutional investors’ site visits on green innovation evidence from China. Technol Soc 68:101904

Ketata I, Sofka W, Grimpe C (2015) The role of internal capabilities and firms’ environment for sustainable innovation: evidence for G ermany. Rd Manag 45(1):60–75

Khan PA, Johl SK (2020) Firm performance from the lens of comprehensive green innovation and environmental management system ISO. Processes 8(9):1152

Kuk G, Fokeer S, Hung WT (2005) Strategic formulation and communication of corporate environmental policy statements: UK firms’ perspective. J Bus Ethics 58:375–385

Laffont JJ, Martimort D (2009) The theory of incentives: the principal-agent model. In The theory of incentives. Princeton University Press

Lai X, Yue S, Guo C et al. (2023) Does FinTech reduce corporate excess leverage? Evidence from China. Economic Anal Policy 77:281–299

Lai X, Zhang F (2022) Can ESG certification help company get out of over-indebtedness? Evidence from China. Pac -Basin Financ J 76:101878

Landrigan PJ, Fuller R, Acosta NJ et al. (2018) The lancet commission on pollution and health. Lancet 391(10119):462–512

Li M, Chen Q (2024) Executive pay gap and corporate ESG greenwashing: Evidence from China. Int Rev Financ Anal 95:103375

Li W, Li W, Seppänen V et al. (2023) Effects of greenwashing on financial performance: Moderation through local environmental regulation and media coverage. Bus Strategy Environ 32(1):820–841

Liao F, Sun Y, Xu S (2023) Financial report comment letters and greenwashing in environmental, social and governance disclosures: Evidence from China. Energy Econ 127:107122

List JA, Sturm DM (2006) How elections matter: Theory and evidence from environmental policy. Q J Econ 121(4):1249–1281

Liu X, Wang E, Cai D (2019) Green credit policy, property rights and debt financing: Quasi-natural experimental evidence from China. Financ Res Lett 29:129–135

Liu Y, Wang A, Wu Y (2021) Environmental regulation and green innovation: Evidence from China’s new environmental protection law. J Clean Prod 297:126698

Lou, X, Li LMW (2023) The relationship of environmental concern with public and private pro‐environmental behaviours: A pre‐registered meta‐analysis. Eur J Soc Psychol 53(1):1–14

Lyon TP, Maxwell JW (2011) Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. J Econ Manag Strategy 20(1):3–41

Lyon TP, Montgomery AW (2015) The means and end of greenwash. Organ Environ 28(2):223–249

Mao J, Xu D, Yang S (2023) Female executives and corporate R&D manipulation behavior: Evidence from China. Financ Res Lett 57:104240

Marquis C, Qian C (2014) Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Symbol or substance? Organ Sci 25(1):127–148

Marquis C, Toffel MW, Zhou Y (2016) Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organ Sci 27(2):483–504

Mendoza-Silva A (2021) Innovation capability: a systematic literature review. Eur J Innov Manag 24(3):707–734

Milbourn TT (2003) CEO reputation and stock-based compensation. J Financial Econ 68(2):233–262

Mo X, Boadu F, Liu Y, et al. (2022) Corporate social responsibility activities and green innovation performance in organizations: Do managerial environmental concerns and green absorptive capacity matter? Front Psychol 13:938682

Mukonza C, Swarts I (2020) The influence of green marketing strategies on business performance and corporate image in the retail sector. Bus strategy Environ 29(3):838–845

Nidumolu R, Prahalad CK, Rangaswami MR (2009) Why sustainability is now the key driver of innovation. Harv Bus Rev 87(9):56–64

Nguyen-Viet B (2023) The impact of green marketing mix elements on green customer based brand equity in an emerging market. Asia-Pac J Bus Adm 15(1):96–116

Nyilasy G, Gangadharbatla H, Paladino A (2014) Perceived greenwashing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions. J Bus Ethics 125:693–707

Opoku RA, Adomako S, Tran MD (2023) Improving brand performance through environmental reputation: The roles of ethical behaviorand brand satisfaction. Ind Mark Manag 108:165–177

Orlitzky M, Schmidt FL, Rynes SL (2003) Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ Stud 24(3):403–441

Pan X, Chen X, Sinha P et al. (2020) Are firms with state ownership greener? An institutional complexity view. s Bus Strategy Environ 29(1):197–211

Peng X, Li J, Tang Q et al. (2024) Do environmental scores become multinational corporations’ strategic “greenwashing” tool for window‐dressing carbon reduction? A cross‐cultural analysis. Bus Strategy Environ 33(3):2084–2115

Porter M, Van der Linde C (1995) Green and competitive: ending the stalemate. The Dynam GCS of the eco-efficient economy: Environmental regulation and competitive advantage. Harv Bus Rev, Brighton 33:129–134

Prieto-Sandoval V, Torres-Guevara LE, Garcia-Diaz C (2022) Green marketing innovation: Opportunities from an environmental education analysis in young consumers. J Clean Prod 363:132509

Ren S, Sun H, Zhang T (2021) Do environmental subsidies spur environmental innovation? Empirical evidence from Chinese listed firms. Technol Forecast Soc Change 173:121123

Schiederig T, Tietze F, Herstatt C (2012) Green innovation in technology and innovation management–an exploratory literature review. RD Manag 42(2):180–192

Shah SGM, Ivascu L (2024) Accentuating the moderating influence of green innovation, environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and innovation output between vigorous board and Romanian manufacturing firms’ performance. Environ, Dev Sustainability 26(4):10569–10589

Spence M (1973) Job market signaling. Q J Econ 87(3):355–374

Takalo SK, Tooranloo HS (2021) Green innovation: A systematic literature review. J Clean Prod 279:122474

Tariq A, Badir YF, Tariq W et al. (2017) Drivers and consequences of green product and process innovation: A systematic review, conceptual framework, and future outlook. Technol Soc 51:8–23

Tong TW, He W, He ZL, et al. (2014) Patent regime shift and firm innovation: Evidence from the second amendment to China’s patent law. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2014, No. 1, p. 14174). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management

Torelli R, Balluchi F, Lazzini A (2020) Greenwashing and environmental communication: Effects on stakeholders’ perceptions. Bus Strategy Environ 29(2):407–421

Triguero A, Moreno-Mondéjar L, Davia MA (2013) Drivers of different types of eco-innovation in European SMEs. Ecol Econ 92:25–33

Vasileiou E, Georgantzis N, Attanasi G et al. (2022) Green innovation and financial performance: A study on Italian firms. Res Policy 51(6):104530

Walker K, Wan F (2012) The harm of symbolic actions and greenwashing: Corporate actions and communications on environmental performance and their financial implications. J Bus Ethics 109:227–242

Weber O (2014) Environmental, social and governance reporting in China. Bus Strategy Environ 23(5):303–317

Weng PS, Chen WY (2017) Doing good or choosing well? Corporate reputation, CEO reputation, and corporate financial performance. North Am J Econ Financ 39:223–240

Wu W, Liang Z, Zhang Q (2020) Effects of corporate environmental responsibility strength and concern on innovation performance: The moderating role of firm visibility. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 27(3):1487–1497

Xie Z, Wang J, Zhao G (2022) When does it pay to be good? A meta-analysis of the relationship between green innovation and financial performance. IEEE Transac Engineering Manag 70(9):3260–3270

Xu N, Zhang D, Bai Y (2024) Managerial long‐termism and corporate innovation: Evidence from China through text mining approaches. Bus Strategy Environ 33(3):2269–2286

Yi Y, Zeng S, Chen H, et al. (2023) When does it pay to be good? A meta-analysis of the relationship between green innovation and financial performance. IEEE Transac Engineering Manag 70(9):3260–3270

Yin L, Yang Y (2024) How does digital finance influence corporate greenwashing behavior? Int Rev Econ Financ 93:359–373

Zhang F, Lai X, Guo C (2024) ESG disclosure and investment-financing maturity mismatch: Evidence from China. Res Int Bus Financ 70:102312

Zhong Y, Lai X, Tan L (2025) Silent generosity: The impact of regulatory distance on silent donations. Econ Lett 247:112130

Zhu J, Fan C, Shi H et al. (2019) Efforts for a circular economy in China: A comprehensive review of policies. J Ind Ecol 23(1):110–118

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Youth Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72202046), and the General Program of the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2024A1515010275).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HL: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, and writing-original draft. LQ: formal analysis and writing-original draft. FW: formal analysis and writing-original draft. ST: investigation, project administration, and funding acquisition. CG: formal analysis and writing-original draft. XL: conceptualization, software, supervision, validation, writing-original draft, writing-reviewing, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.