Abstract

Digital platforms facilitate interactions between buyers and sellers. This study examines intermediary shopping platforms’ strategic search designs and their effects by incorporating consumer behaviors. Some consumers, often referred to as “naïve,” possess limited expertise in evaluating a product’s value. We find that when confronted with higher search costs, naïve consumers tend to assess fewer products and limit the depth of their evaluations. The relationship between market prices and consumer naïvety is non-monotonic and hinges on the disparity in search costs between naïve and sophisticated consumers. Thus, platforms encounter a trade-off between reducing search costs to encourage naïve consumers to explore goods more extensively and avoiding excessive reduction to prevent sophisticated consumers from evaluating too many products. Using data from a prominent e-commerce platform, we also empirically substantiate the observation that sophisticated consumers tend to engage in more comprehensive product evaluations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Digital platforms (e.g., Amazon, eBay, and JD Mall) are essential in modern economies. Economists have long recognized that online platforms significantly reduce consumer search costs (Goldfarb and Tucker, 2019). In addition, recent studies have shown that profit-maximizing platforms intentionally increase consumer search costs. Many digital shopping platforms operate as two-sided marketplaces that enable interactions and transactions between buyers and independent third-party sellers and charge sellers a transaction-based fee, such as a proportion fee or a per-transaction fee (Teh, 2022). The search environment a platform provides could affect consumers’ search behaviors and impact both sellers and the platform’s profits. In other words, platforms can distort their search design to maximize profits. Hagiu and Jullien (2011) demonstrated that platforms may divert searches strategically. And if consumers can decide how many products they will evaluate, the platforms can provide a search environment that ensures that they do not compare too many products (Dukes and Liu, 2016).

In the recent papers mentioned above, consumers are assumed to be completely rational and not prone to making frequent mistakes. However, as stated in many studies on behavioral industrial organizations, some consumers (sometimes referred to as “naïve consumers”,) make systematic mistakes when evaluating the value they derive from a product (Heidhues and Köszegi, 2018). For example, naïve consumers may be uncertain about what they will pay for a particular product. Armstrong and Vickers (2012) found that, compared to sophisticated consumers, naïve consumers are unaware of overdraft charges, although these charges can be easily found after a few clicks on a particular website. In addition to price, consumers might also face uncertainty about other market fundamentals. For example, due to limited time and information, they may not be able to fully evaluate the value of all of the products offered.

We explore the alternative possibility that consumers misunderstand the value (quality) of a product rather than its actual price. Naïve consumers, who have limited capacitynd attention to evaluate ththe value of productsucts (Blake et al. 2021; Boyacı and Akçay, 2018; Liu and Dukes, 2016), may face uncertainty and make mistakes when purchasing goods on platforms. As an example, consider a consumer who intends to buy a computer and searches on the platform. If the consumer is naïve, they might be unfamiliar with the necessary specifications (e.g., the distinctions between different processors). Although they can explore various options on the platform for information on different computers, their capacity to evaluate the actual utility of these devices remains limited. However, sophisticated consumers could correctly infer the quality of the offered product. On the online shopping platform, consumers must select from a large set of competing products (Dinerstein et al. 2018). Therefore, in the digital age, behavioral biases continue to be widespread (Stango and Zinman, 2023).

Given the rapid progress in platform search design and consumer behavioral studies, this study aims to investigate the implications of consumer heterogeneity, particularly naïve heterogeneity, on the strategic search designs of digital shopping platforms. In particular, we focus on the difference between naïve and sophisticated consumers’ search behaviors and how the distribution of heterogeneous consumers affects seller prices and the strategic search design of the platform.

To investigate the proposed research question, we extend the framework of Dukes and Liu (2016) by introducing naive consumers. In our theoretical model, there is a monopoly of the two-sided online shopping platform and two types of consumers: naïve and sophisticated. Our main results illustrate the trade-off between these two types of consumers. We begin by analyzing the differences in search behaviors between naïve and sophisticated consumers, assuming that a naïve consumer incurs a higher evaluation cost than a sophisticated one when assessing a product’s value. A consumer’s evaluation plan includes two dimensions: (1) the number of products evaluated and (2) how deeply each product is evaluated. We show that sophisticated consumers tend to evaluate more products at a greater depth than their naïve counterparts.

First, we consider a case in which the search environment is provided exogenously on the shopping platform. Additionally, we investigate the third-party sellers’ pricing strategies. We find that market prices are non-monotonic with the degree of consumer naïvety. Compared with the market without naïve consumers, the equilibrium price remains unchanged only when the evaluation costs of both naïve and sophisticated consumers are sufficiently low. Moreover, sellers will charge a higher price when naïve consumers evaluate the products as costlier because the average evaluation breadth is lower and sellers face less competition. However, if the difference between naïve and sophisticated consumers is sufficiently large, sellers will charge a lower price because the average evaluation depth of all consumers is substantially lower. Depending on the difference in the evaluation costs of these two types of consumers, naïve consumers might exert negative or positive externalities on sophisticated consumers.

Next, we examine the platform’s strategic search design by allowing it to determine consumers’ search costs endogenously. We find that the platform faces a fundamental trade-off between lowering the search cost to encourage naïve consumers to evaluate goods at greater depth and avoiding excessive reduction to prevent sophisticated customers from evaluating too many products. This study deepens the understanding of a platform’s strategic search design by incorporating the behaviors of different types of consumers.

To test our model predictions, we also employ data from a prominent online shopping platform — “JD.com” — to explore the difference between the behaviors of different types of consumers. Based on clickstream data, we construct variables that measure consumers’ search breadth and depth and distinguish naïve and sophisticated consumers based on their membership levels. We propose a novel instrumental variable (IV) to clearly identify the causal effects. Based on individual-level regressions, we find that sophisticated consumers have a propensity to evaluate a larger number of products in greater detail than naïve ones.

Related literature

Our study builds on the growing literature on digital platform search designs and the research relating to behavioral industrial organizations. First, numerous studies have shown that digital platforms can significantly reduce consumers’ search costs. For example, a platform can provide faceted navigation aids to help consumers screen a large number of goods (Chen and Yao, 2017; Choi et al. 2018; Dukes and Liu, 2016). Moreover, recommendation systems can reduce consumers’ search costs (De Corniere, 2016; Zhong, 2023). A platform’s search cost prevents consumers from searching or not purchasing when there are either too many or too few alternatives(Kuksov and Villas-Boas, 2010). Low search costs make it easier for consumers to compare prices, which reduces products’ prices and price dispersion (Orlov, 2011; Parker et al. 2016), increases product variety (Zhang, 2018), and improves the quality of matches between buyers and sellers (Cullen and Farronato, 2021; Kuhn and Mansour, 2014). Thus, lower search costs can substantially increase overall social welfare.

Numerous recent studies have also illustrated some trade-offs associated with a platform’s search design and, thus, divert search (Dukes and Liu, 2016; Hagiu and Jullien, 2014). Zhong (2016) found that a more precise targeted search can lower the equilibrium price on the platform, but if the targeted search reaches a significant level of precision, sellers will obtain more monopoly power and the equilibrium price will increase. Dinerstein et al. (2018) showed that platforms would like to guide buyers to their most desired goods while also strengthening the competition of third-party sellers. Platforms can also steer consumers to certain sellers using a recommendation algorithm or guarantee certain sellers (Barach et al. 2020; Teh and Wright, 2022).

In some cases, a platform may assume the roles of both intermediary and seller simultaneously, leading to potential preferential treatment of its own products (Teng, 2022). Chen and Tsai (2023) empirically established that a platform’s own products are more likely to be recommended to consumers via the “Frequently Bought Together” recommendation algorithm than those third-party products. Other studies have pointed out that a platform’s “ content biases” or “self-preferencing” are not always pro-competition(Hagiu et al. 2022; Zennyo, 2022).

Our study investigates a platform’s search design by extending the framework originally proposed by Dukes and Liu (2016). However, in contrast to Dukes and Liu (2016), our analysis incorporates two distinct types of consumers within the market to provide valuable insights into how consumer heterogeneity, particularly naïve heterogeneity, influences a platform’s search design.

Second, recent studies on behavioral industrial organizations have demonstrated that consumer behaviors in the market can influence market outcomes and social welfare (Heidhues and Köszegi, 2018). In financial markets, many consumers ignore “hidden prices” when making purchase decisions (Gabaix and Laibson, 2006; Heidhues et al. 2016). Due to information costs, myopic or naïve consumers may purchase the initial item without recognizing the higher aftermarket prices (Armstrong and Vickers, 2012). Additionally, individuals might make erroneous projections about their future behaviors and associated costs, commonly referred to as “use-pattern mistakes” (Bar-Gill and Ferrari, 2010). In certain instances, a consumer’s behavior may diverge from their initial ex-ante beliefs, creating potential opportunities for price discrimination. Gurun et al. (2016) showed that lenders target naïve consumers with advertisements for expensive mortgages.

On digital platforms, consumers can typically access an extensive array of products offered by numerous sellers; however, they tend to evaluate only a limited number of items. Ursu et al. (2020) found that most consumers only search for a few restaurants on the platform. Although there are thousands of products to choose from on the platform, consumers often evaluate only a small number of them (Dinerstein et al. 2018). Although many platforms provide summary symbols about sellers, consumers may be limited to corresponding ratings (Zhong, 2022). When purchasing from a seller, consumers might not have access to complete and pertinent information (e.g., product quality references) (Liu and Dukes, 2016) or misperceive the value of the products (Murooka, 2015). Consequently, sellers might “cheat” consumers who fail to recognize low-quality items (Armstrong and Chen, 2009).

Nowadays, platforms can collect and analyze enormous quantities of consumer data (Gardete and Hunter, 2020; Ghose et al. 2019) and identify or exploit different types of consumers. Using digital technologies, platforms can track users and analyze their behaviors at a low cost. For example, Ursu et al. (2024) showed that, with the help of eye-tracking technology, a platform can predict consumers’ choices based on their prior information and consumers rely on partially myopic rules. Using rich data, a platform can implement price discrimination among different types of consumers (Baik and Larson, 2023; Ru and Schoar, 2016). The exploitation of naïve consumers could affect not only the allocation of welfare between consumers but also the distribution between sellers and consumers (Armstrong and Vickers, 2012; Gabaix and Laibson, 2006; Grubb, 2015). Subsequently, firms may have incentives to educate (Eliaz and Spiegler, 2011a, b) or obfuscate naïve consumers (Carlin, 2009; Chioveanu and Zhou, 2013).

Our work focuses on naïve consumers as their ability to evaluate the value of various products is limited. Our specification broadens the notion of “naïve consumers" beyond its conventional reference to misconceptions about contracts in financial markets to encompass a misunderstanding of product valuation on digital platforms.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical model setup and analysis, and Section 3 explores some discussions on the topic. Section 4 provides empirical evidence, and Section 5 concludes. All of the omitted proofs are presented in the Appendix.

Model

The platform consists of n third-party sellers who sell horizontally differentiated products, each of whom sells a single product. There are m buyers on the platform, and each consumer has a demand for one product. Consumers can be categorized as naïve or sophisticated. The proportion of naïve consumers is α. Therefore, the proportion of sophisticated consumers is 1 − α. Both naïve and sophisticated consumers face initial information imperfections regarding product fit, and realized fit is independent of consumers. Consequently, consumers evaluate a product through a search process on a platform to ascertain its idiosyncratic utility. The search process incurs costs, and the platform can influence consumer search costs through its search design. When analyzing the platform’s search environment, consumers make decisions regarding the breadth of evaluation (the number of products to assess) and the depth of evaluation (the extent of information to gather about each considered product).

The timeline of the model is as follows:

-

1.

Nature chooses which consumer is naïve and which is sophisticated, which implies that nature chooses the proportion of naïve consumers (α) and the proportion of sophisticated consumers (1 − α).

-

2.

The platform determines its search environment by controlling search costs.

-

3.

Every n seller simultaneously selects a price for a product.

-

4.

Both naïve and sophisticated consumers choose their search depth and breadth.

-

5.

Both naïve and sophisticated consumers evaluate the products they choose at a selected search depth. Consumers acquire knowledge about the realized idiosyncratic fit parameter and price of each evaluated product. Ultimately, consumers make purchase decisions based on this information.

As in Dukes and Liu (2016), we use subgame perfection as our equilibrium.

Consumer’s search choice

The consumer’s overall ex-post realized utility of product i, if evaluated at full, is

where v is the base level of utility Footnote 1, pi is product \({i}^{{\prime} }s\) price, and εi is a random utility term drawn from a standard extreme value distribution. We also assume that εi is independent and identically distributed(i.i.d.). The mean E(εi) = γ and the variance \(var({\varepsilon }_{i})=\frac{{\pi }^{2}}{6}\). In Equation(1), μ captures the degree of differentiation between products. For analytical convenience, consistent with Dukes and Liu (2016), we assume that a consumer’s search process occurs simultaneously across products (Stigler, 1961), and that the consumer commits to their evaluation plan before finalizing a purchase decision. Before evaluating products, the consumer chooses their “evaluation plan”: (b, d); that is, the consumer decides how many products to evaluate ("evaluation breadth” b ∈ (0, n]) and how deep to evaluate them ("evaluation depth ”d ∈ (0, 1]). We exclude the cases of b = 0 and d = 0, which imply that if a consumer chooses not to search for any product or knows nothing about it, they cannot buy it.

Additionally, in our setting, a consumer can choose to partially evaluate a product. If d = 1, the consumer chooses to fully evaluate the product. In this scenario, the consumer learns to realize εi. If the consumer chooses d ∈ (0, 1), the product is partially evaluated. In this case, εi can be expressed as \({\varepsilon }_{i}=\,{\text{D}}\,{\rm{d}}{\hat{\varepsilon }}_{\rm{i}}+{\theta }_{\rm{i}}({\rm{d}})\). In this context, \({\hat{\varepsilon }}_{i}\) represents a random utility term drawn from a standard extreme value distribution (EVD). Additionally, θi(d) denotes another random variable with a known mean of (1 − d)γ and a variance of (1 − d2)var(εi). We also assume that \(d{\hat{\varepsilon }}_{i}\) and θi(d) are distributed independently. In other words, if a consumer evaluates products at depth d, they can observe \(d{\hat{\varepsilon }}_{i}\) but cannot observe the remaining portion θi(d). Under evaluation plan (d, b), the consumer reveals the realized utility components \({d{\hat{\varepsilon }}_{i}}_{i = 1}^{b}\), while the remaining component is unobservant of \({\theta (d)}_{i = 1}^{b}\).

The consumer can observe pi, the price of the product sold by seller i. Thus, the consumer purchases the product with the highest expected utility among the b partially evaluated products. That is,

where E[θi(d)] is the expected utility of a product when the search depth is d. {dεi} are i.i.d. random variables with EVD. We derive a closed-form expression for the purchase probability of the product i.

The consumer selects an evaluation plan (b, d) before assessing the products. Consequently, the purchase decision relies on expected evaluation values rather than the realized utility. Because all products are identical before the evaluation, the consumer believes (correctly) that all sellers charge the same price, pi = p, in equilibrium. We can then obtain the expected benefit of the evaluation plan (b, d):

which can be simplified to

A key assumption of this study is the difference in the ability of naïve and sophisticated consumers to learn the realized utility of products. A sophisticated consumer can fully learn about the realized utility of a product at a lower cost. However, the evaluation cost is much higher for naïve consumers. Recall our motivating example, in which a consumer who wishes to buy a computer. A sophisticated consumer knows his or her preferences in computers (e.g., color, size, processor, storage, memory, etc.) but does not have a particular computer in mind. Thus, they search on an online platform and evaluate a set of computers offered by third-party sellers. Although the search process is expensive, the sophisticated consumer can evaluate the realized utility of different computers in more detail and identify the computer that best matches their preferences. However, if the consumer is naïve, they may want to buy a computer for work but are uncertain about its technical specifications. For instance, they might not know the difference between an 8-core processor and a 4-core processor. Thus, although they can still search on the platform for information on different computers, their ability to learn about the realized utility is very limited. In other words, due to the complications of product attributions, a naïve consumer’s evaluation cost is much higher, and it is harder for them to evaluate the products, which leads to them making systematic mistakes in assessing the value they will derive from a product.

Assume that the consumer’s evaluation cost for a product at full depth (d = 1) in an exogenously given search environment is τ, and the cost of evaluation plan (b, d) is f(b, d) = τbd2 (or “search cost”). The quadratic specification of search depth reflects that consumers evaluate a product based on easy attributes (e.g., colors and size) and then harder attributes that incur higher costs. In this study, we divide consumers into two types: naïve and sophisticated. The key difference between the two is their evaluation cost (Spiegler, 2019). The evaluation cost for naïve and sophisticated customers is τN and τS, respectively. We assume 0 < τS < τN, which implies that naïve consumers find it more difficult to evaluate products. The definition of naïve consumers in this study is consistent with that of many behavioral industrial organization studies. Heidhues and Köszegi (2018) argued that some consumers are “naïve” and make mistakes in assessing the value they will derive from a product. A typical naïve consumer usually ignores the “hidden price.” In this study, a naïve consumer has difficulty assessing the fitness of a product based on their preference, but they can easily observe the product’s price.

First, we assume that the search environment on a monopoly platform is exogenously given and investigate the optimal search plan and optimal pricing strategy for consumers and sellers, respectively. We then endogenize the platform’s search cost to investigate its optimal search design.

For a consumer with an evaluation cost τ (τ = τN or τ = τS), the expected utility with evaluation plan (b, d) is given by

By maximizing both types of consumers’ expected utility with respect to b ∈ (0, n] and d ∈ (0, 1], we can derive their optimal search plan with a certain exogenously given search environment \((\hat{b},\hat{d})\), shown in Lemma 1 Footnote 2.

Lemma 1

Given n > e2, b ∈ (0, n], and d ∈ (0, 1], the consumer’s optimal evaluation plan is

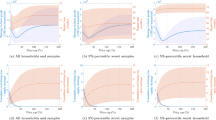

Lemma 1 reflects how a consumer’s optimal evaluation plan \((\hat{b},\hat{d})\) varies with the evaluation cost. If the evaluation cost is high (\(\tau\, >\, \frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}}\)), the consumer chooses to partially evaluate the products at a fixed amount. When the evaluation cost decreases below a certain threshold (\(\tau =\frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}}\)), the consumer evaluates a greater number of products fully. If consumers can evaluate products at a sufficiently low cost, they will fully evaluate all products (\(\hat{b}=n,\hat{d}=1\)). Lemma 1 also indicates that with larger product differentiation (μ), a consumer will evaluate more products in greater depth. Lemma 1 illustrates that if consumers are rational but heterogenous in their ability to assess the value they derive from a product, their optimal search behaviors will also differ. The following proposition characterizes how naïve and sophisticated consumers behave differently when choosing their evaluation plans in an exogenous search environment on a monopoly intermediary platform.

Proposition 1

When n > e2, and 0 < τS < τN, \({\hat{b}}_{S}\ge {\tau }_{N}\),

-

\({\hat{b}}_{S}\ge {\hat{b}}_{N}\), with the equality holds only when \(0 \,<\, {\tau }_{S}\, <\, {\tau }_{N}\le \frac{\mu }{n}\) or \(\frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}}\le {\tau }_{S} \,< \,{\tau }_{N}\),

-

\({\hat{d}}_{S}\ge {\hat{d}}_{N}\), with the equality holds only when \(0 \,<\, {\tau }_{S} \,<\, {\tau }_{N}\,\le\, \frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}}\).

In Proposition 1, \({\hat{b}}_{S}\) and \({\hat{d}}_{S}\) represent the optimal evaluation breadth and depth of a sophisticated consumer, respectively. The naïve consumer’s optimal evaluation plan is \(({\hat{b}}_{N},{\hat{d}}_{N})\). Figure 1 illustrates Proposition 1. Specifically, Figure 1A shows the optimal search depth for naïve and sophisticated consumers. Figure 1B shows the different types of consumers’ optimal search breadths. This proposition illustrates that in a certain search environment on a platform, sophisticated consumers tend to evaluate more products at a greater depth than naïve consumers.

In our model, the evaluation costs are higher for naïve consumers. Consumers may incur higher evaluation costs for several reasons. First, some consumers may be unfamiliar with specific products or lack expertise (Gamp and Krähmer, 2022). For instance, when a consumer intends to purchase a computer but lacks knowledge about its technical specifications, evaluating whether a computer aligns with their preferences becomes more challenging despite having easy access to detailed technical information for all available computers. Second, for some consumers, the opportunity cost is higher. For example, a student might have more time to find out what the technical attributes of a computer mean, but a person’s time who has to work might be very limited. Therefore, the opportunity cost is higher for individuals with limited time.

Proposition 1 also implies that, owing to higher evaluation costs, naïve consumers face greater uncertainty about the product’s value than sophisticated consumers. In other words, naïve consumers choose to evaluate fewer products at a lower depth. Consequently, they are more likely to make mistakes when assessing the value they derive from a product. Although both naïve and sophisticated consumers are rational, the former has a higher probability of making mistakes.

Seller’s pricing strategy

Next we investigate the price decisions of the n sellers given the platform’s search environment and consumers’ anticipated evaluation plan, \((\hat{b},\hat{d})\). The anticipated evaluation plan for naïve consumers is \(({\hat{b}}_{N},{\hat{d}}_{N})\), and that for sophisticated consumers is \(({\hat{b}}_{S},{\hat{d}}_{S})\). We also assume that the proportion of naïve consumers on the platform is α; thus, the proportion of sophisticated consumers is 1 − α. As the mass of consumers is normalized to one, we assume that the probability of the representative consumer being a naïve and sophisticated consumer is α and 1 − α, respectively.

Because the sellers are the same, we assume that they charge the same prices at equilibrium. A consumer’s evaluation plan is developed before knowing the prices; therefore, it depends on their rational expectations. In other words, the consumer’s evaluation plan remains unchanged, even if the sellers deviate from the symmetric equilibrium price. By contrast, consumers’ purchase decisions are contingent on observing product prices. Consequently, any deviation in price influences consumers’ choices. Seller i charges price pi, and all other sellers charge price p. Under the above assumptions, we can derive the purchase probability of product i as

where d is either dN or dS, If d = dN, the probability of a naïve consumer purchasing product i is denoted by qNi; when d = dS, qi = qSi.

Because the products are identical to those of consumers before evaluation, consumers randomly choose b products for evaluation. Thus, the probability of product i being selected for evaluation is \(\frac{b}{n}\). As the representative consumer may be a naïve consumer with probability α or a sophisticated consumer with probability 1 − α, the conditional demand for product i is \((1-\alpha )\frac{{b}_{S}}{n}{q}_{Si}+\alpha \frac{{b}_{N}}{n}{q}_{Ni}\). Then seller i’s expected profit is

where ρ ∈ (0, 1) is the platform’s referral fee. Seller i selects price pi to maximize its expected profit. The seller’s optimal pricing strategy is as follows:

Lemma 2

When n > e2, with a sophisticated consumer’s optimal evaluation plan \(({\hat{b}}_{S},{\hat{d}}_{S})\) and a naïve optimal evaluation plan \(({\hat{b}}_{N},{\hat{d}}_{N})\), the seller’s equilibrium prices are given by

The symmetric equilibrium price in Lemma 2 aligns with the results derived from different micro-foundations involving unit-demand consumers, e.g., Dukes and Liu (2016), Choi et al. (2018), Teh and Wright (2022), and Zhong (2023). As reflected in Lemma 2, the sellers’ prices at equilibrium are partially affected by both sophisticated and naïve consumer evaluation depth and breadth. Specifically, if consumers (either naïve or sophisticated) choose a greater evaluation depth, they can better appreciate the value of the most preferred product, which can be called the “evaluation depth effect” (Dukes and Liu, 2016). Lemma 2 also implies the “evaluation breadth effect”: as consumers (either naïve or sophisticated) evaluate more products, sellers face more competition and the equilibrium price falls. If no naïve consumers exist (α = 0), the seller’s equilibrium price is reduced to

which is identical to that proposed by Dukes and Liu (2016).

It would be interesting to compare \(\hat{p}\) to \({\hat{p}}^{* }\). Given that the search environment on the platform is determined exogenously, if \(\hat{p} > {\hat{p}}^{* }\), naïve consumers exert a negative externality on sophisticated consumers. On the contrary, naïve consumers exert a positive externality on sophisticated consumers when \(\hat{p} \,<\, {\hat{p}}^{* }\). The following proposition shows how the values of τS and τN affect the relationship between \(\hat{p}\) and \({\hat{p}}^{* }\):

Proposition 2

Let n > e2,

-

\(\hat{p}={\hat{p}}^{* }\), when \({\tau }_{S}\, <\, {\tau }_{N}\le \frac{\mu }{n}\),

-

\(\hat{p}\ge {\hat{p}}^{* }\), when (i)\({\tau }_{S}\, <\, \frac{\mu }{n} \,<\, {\tau }_{N}\le \frac{(1-1/n)\mu }{{e}^{2}-1}\); or (ii) \(\frac{\mu }{n}\, <\, {\tau }_{S}\le \frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}}\), and \({\tau }_{S} \,< \,{\tau }_{N}\le \frac{\mu -{\tau }_{S}}{{e}^{2}-1}\). with equality holds only when \({\tau }_{N}=\frac{(1-1/n)\mu }{{e}^{2}-1}\), or \({\tau }_{N}=\frac{\mu -{\tau }_{S}}{{e}^{2}-1}\),

-

\(\hat{p}\, <\, {\hat{p}}^{* }\), when (i) \({\tau }_{S}\le \frac{\mu }{n}\), and \({\tau }_{N}\, >\, \frac{(1-1/n)\mu }{{e}^{2}-1}\); or (ii)\(\frac{\mu }{n} \,<\, {\tau }_{S}\le \frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}}\), and \({\tau }_{N} \,>\, \frac{\mu -{\tau }_{S}}{{e}^{2}-1}\), or (iii) \(\frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}} \,<\, {\tau }_{S}\, <\, {\tau }_{N}\).

Proposition 2 states how different types of consumers’ abilities to assess the value of a product affect sellers’ pricing strategies. If both naïve and sophisticated consumers’ evaluation costs are sufficiently small \(({\tau }_{S}\le \frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}})\), they will evaluate all products in full depth. Thus, from the sellers’ perspective, there is no difference between naïve and sophisticated consumers. The sellers’ pricing strategy is the same as when all consumers in the market are sophisticated.

When the evaluation cost of sophisticated consumers is small, naïve consumers assess the products as costlier and may exert a negative externality on sophisticated consumers. In other words, due to the existence of naïve consumers, sophisticated consumers have to buy products at higher prices. More specifically, if the evaluation cost of sophisticated consumers is low \(({\tau }_{S} \,<\, \frac{\mu }{n})\) and the naïve consumers’ evaluation cost is moderately high \((\frac{\mu }{n}\, <\, {\tau }_{N}\le \frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}})\), both naïve and sophisticated will evaluate the products at full depth (\({\hat{d}}_{S}={\hat{d}}_{N}=1\)). Naïve consumers evaluate fewer products than sophisticated consumers (\({\hat{b}}_{N}=\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{N}} \,<\, {\hat{b}}_{S}=n\)). In this case, the naïve consumers reduce the “evaluation breadth effect.” When naïve consumers’ evaluation costs increase slightly \(\left(\frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}} \,< \,{\tau }_{N}\le \frac{(1-1/n)\mu }{{e}^{2}-1}\right)\), they will evaluate a fixed number of products (\({\hat{b}}_{N}={e}^{2}\)). Consequently, the “evaluation depth effect” from naïve consumers will be weaker, and the equilibrium price will become lower but still higher than \({\hat{p}}^{* }\). This is similar to the cases of \(\frac{\mu }{n} \,<\, {\tau }_{S}\le \frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}}\) and \({\tau }_{S} \,<\, {\tau }_{N}\le \frac{\mu -{\tau }_{S}}{{e}^{2}-1}\). As the evaluation cost increases, the naïve consumer evaluates fewer products, which could increase the equilibrium price. They also evaluate products less in depth, which may reduce the sellers’ equilibrium prices. If the difference between naïve and sophisticated consumers is not sufficiently large, naïve consumers will exert a negative externality on sophisticated consumers.

When the evaluation cost between naïve and sophisticated consumers is sufficiently large, naïve consumers may exert a positive externality on sophisticated consumers. According to Proposition 2, if a sophisticated customer’s evaluation cost is low (\({\tau }_{S}\le \frac{\mu }{n}\)) and a naïve consumer’s evaluation cost is high (\({\tau }_{N} > \frac{(1-1/n)\mu }{{e}^{2}-1}\)), the equilibrium price \(\hat{p}\) will be lower than \({\hat{p}}^{* }\). Because naïve consumers’ evaluation costs are high, they will rationally choose to evaluate fewer products at a much less depth. Subsequently, sellers face less competition and their products are less appreciated by naïve consumers. In other words, the “evaluation breadth effect” from naïve consumers’ search behavior increases the equilibrium price, while the “evaluation depth effect” decreases the price and dominates the “evaluation breadth effect.” The proportion of naïve consumers, α, also affects the magnitude of the positive externality exerted by naïve consumers on sophisticated consumers. It is obvious that the externality increases as α increases. The case is similar when \(\frac{\mu }{n}\, <\, {\tau }_{S}\le \frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}}\), and \({\tau }_{N}\, >\, \frac{\mu -{\tau }_{S}}{{e}^{2}-1}\); or \(\frac{\mu }{{e}^{2}} \,<\, {\tau }_{S} \,<\, {\tau }_{N}\).

In summary, Proposition 2 indicates that naïve consumers may exert a negative or positive externality on sophisticated consumers depending on the magnitude of their “evaluation breadth” and “evaluation depth” effects. When a naïve consumer’s evaluation cost is moderately higher than a sophisticated consumer’s, the “evaluation breadth effect” dominates, leading to a lower equilibrium price. In contrast, if the naïve consumers’ evaluation cost is sufficiently higher than that of sophisticated consumers’, the “evaluation depth effect” dominates. Sellers lower prices to attract naïve consumers, and sophisticated consumers benefit from them.

Platform’s search design

In Section 2.2, we investigate the sellers’ pricing strategies with heterogenous consumers and an exogenous platform search environment. We assume that a platform can lower consumer evaluation costs. For example, a platform can provide various search aids or more precise recommendations to reduce consumer search costs. Let s ∈ [0, 1] denote the platform’s effort to lower consumer search costs. Subsequently, the consumer’s search cost with evaluation plan (b, d) is (1 − s)τbd2, where τ = τS or τ = τN. If s = 0, the platform does not try to help consumers evaluate the products. In this case, neither naïve nor sophisticated consumers’ evaluation costs change. When s = 1, consumers can evaluate products at no extra cost. s ∈ (0, 1) indicates that the platform partially lowers the consumer search costs.

When the search environment is endogenously given, the consumer’s (either naïve or sophisticated) expected utility with evaluation plan (b, d) can be rewritten as

where τ = τS or τ = τN, and we can easily obtain both naïve and sophisticated consumers’ optimal evaluation depths:

Consumers’ optimal evaluation breadths

As argued by Dukes and Liu (2016), a platform’s search environment can affect a consumer’s optimal evaluation plan. In particular, when the search cost is low, consumers evaluate more products at greater depths and vice versa. Profit-maximizing sellers choose an optimal price given the consumer’s evaluation plan and the platform’s search environment. The following lemma characterizes the sellers’ equilibrium prices:

Lemma 3

Let n > e2 for any s ∈ [0, 1], α ∈ [0, 1], and 0 < τS < τN, with the naïve consumers’ optimal evaluation plan (\(\hat{b},\hat{d}\)) and τ = τS or τ = τN. The seller’s symmetric equilibrium prices are given by

Lemma 3 illustrates how the platform’s search design affects the sellers’ symmetric equilibrium prices. When the platform only modestly lower consumers’ search cost (\(0\le s\le 1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{S}{e}^{-2}}\)), both naïve and sophisticated consumers will choose to partially evaluate a fixed number of products (\({\hat{b}}_{S}={\hat{b}}_{N}\)) at a lower depth (\({\hat{d}}_{S}=\frac{\mu }{(1-s){\tau }_{S}}\), and \({\hat{d}}_{N}=\frac{\mu }{(1-s){\tau }_{N}}\)). Thus, symmetric price increases only through the “evaluation depth effect.” When s is gets a little bit higher (\(1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{S}}{e}^{-2} \,<\, s\le 1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{N}}{e}^{-2}\)), the sophisticated consumer will fully evaluate the products (\({\hat{d}}_{S}=1\)), whereas the naïve consumer will still only partially evaluate the products. On the other hand, sophisticated consumers will evaluate more products (\({\hat{b}}_{S}=\frac{\mu }{(1-s){\tau }_{S}}\)), whereas naïve consumers will still evaluate a fixed number of products. In this case, the “evaluation depth effect” from naïve consumers will increase the equilibrium price, while the “evaluation breadth effect” from sophisticated consumers will decrease the price. If s increases (\(1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{N}}{e}^{-2}\, <\, s\le 1-\frac{\mu }{n{\tau }_{S}}\)), both naïve and sophisticated consumers will evaluate the products at full depth (\({\hat{d}}_{S}={\hat{d}}_{N}=1\)) and the price will decrease through naïve and sophisticated consumers’ “evaluation breadth effect”.

The platform can also choose an even higher s (\(1-\frac{\mu }{n{\tau }_{S}} < s\le 1-\frac{\mu }{n{\tau }_{N}}\)). In this case, the sophisticated consumers will evaluate all of the products (\({\hat{b}}_{S}=1\)) at full depth (\({\hat{d}}_{S}=1\)). However, naïve consumers will not evaluate all of the products (\({\hat{b}}_{N}=\frac{\mu }{(1-s)\tau \_N}\)). Consequently, the equilibrium price decreases only through naïve consumers’ “evaluation breadth effect.” If s are sufficiently high, both naïve and sophisticated consumers will evaluate all products in full depth. In this case, the symmetric equilibrium price does not depend on the s or consumer’s evaluation cost.

We now consider the platform’s search design by choosing s ∈ [0, 1] and assume that the platform incurs a 0 cost by providing a search environment. Thus, the platform’s expected profit is

where ρ ∈ (0, 1) is the referral fee charged by sellers and \(\hat{p}(s)\) is the symmetric equilibrium price given in Lemma 3.

The platform’s objective is to maximize the equilibrium price. From Lemma 3, we can see that when \(0\le s\le 1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{S}}{e}^{-2}\), the seller’s equilibrium increases with s, whereas when \(1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{N}}{e}^{-2} \,<\, s\), the equilibrium price decreases with s. When \(1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{N}}{e}^{-2} \,<\, s\le 1-\frac{\mu }{n{\tau }_{S}}\), the equilibrium may increase or decrease with the s depending on the proportion of naïve consumers α. The following proposition characterizes the platform’s optimal search design s, given the consumers’ optimal evaluation plan and the sellers’ pricing strategy.

Proposition 3

Let n > e2. In equilibrium,

-

If \(\frac{{e}^{2}}{{e}^{2}-1}\frac{{\tau }_{S}}{{\tau }_{N}}\le \frac{\alpha }{1-\alpha }\), the platform has a search design \({s}^{* }=1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{N}}{e}^{-2}\), the sophisticated and naïve consumers’ optimal evaluation plans are \(\{({\hat{b}}_{S},{\hat{d}}_{S}):{\hat{b}}_{S}=\frac{\mu }{(1-{s}^{* }){\tau }_{S}}\, > \,{e}^{2},{\hat{d}}_{S}=1\}\), and \(\{({\hat{b}}_{N},{\hat{d}}_{N}):{\hat{b}}_{N}={e}^{2},{\hat{d}}_{N}=1\}\) respectively, and the sellers’ price is \(\hat{p}({s}^{* })={[(1-\alpha )\frac{\mu -(1-{s}^{* }){\tau }_{S}}{{\mu }^{2}}+\alpha \frac{({e}^{2}-1)(1-{s}^{* }){\tau }_{N}}{{e}^{2}{\mu }^{2}}]}^{-1}\).

-

If \(\frac{{e}^{2}}{{e}^{2}-1}\frac{{\tau }_{S}}{{\tau }_{N}} > \frac{\alpha }{1-\alpha }\), the platform has a search design \({s}^{* }=1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{S}}{e}^{-2}\), the sophisticated and naïve consumers’ optimal evaluation plans are \(\{({\hat{b}}_{S},{\hat{d}}_{S}):{\hat{b}}_{S}={e}^{2},{\hat{d}}_{S}=1\}\), and \(\{({\hat{b}}_{N},{\hat{d}}_{N}):{\hat{b}}_{N}={e}^{2},{\hat{d}}_{N}=\frac{\mu }{(1-{s}^{* }){\tau }_{N}} < 1\}\) respectively, and the sellers’ price is \(\hat{p}({s}^{* })={[(1-\alpha )\frac{\mu -(1-{s}^{* }){\tau }_{S}}{{\mu }^{2}}+\alpha \frac{({e}^{2}-1)(1-{s}^{* }){\tau }_{N}}{{e}^{2}{\mu }^{2}}]}^{-1}\).

Proposition 3 illustrates how the proportion of naïve consumers in a market affects a platform’s search design strategy. When designing the search environment, the platform faces two main trade-offs. First, the platform’s optimal search environment should lower both naïve and sophisticated consumers’ search costs to allow them to evaluate the products at a greater depth so that consumers appreciate the products they purchased. However, the platform does not provide a search environment that allows consumers to evaluate products at a sufficiently low search cost. Evaluating more products induces sellers to price their products more competitively.

Second, since the responses from a naïve consumer and a sophisticated consumer to the platform’s search cost differ, the platform needs to balance between the “evaluation breadth effect” from sophisticated consumers and the “evaluation depth effect” from naïve consumers. Specifically, if \(1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{S}}{e}^{-2} \,<\, s\le 1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{N}}{e}^{-2}\), sophisticated consumers already fully evaluate the products, whereas naïve consumers only partially evaluate them. In this case, increasing s leads the sophisticated consumers to evaluate more products at full depth and the naïve to evaluate a fixed number of products at a greater depth. In other words, the “evaluation breadth effect” from sophisticated consumers will decrease the equilibrium price while the “evaluation depth effect” from naïve consumers will increase the price.

Proposition 3 states that the total effect depends on the proportion of naïve consumers in the market. If the proportion of naïve consumers is high enough (\(\frac{{e}^{2}}{{e}^{2}-1}\frac{{\tau }_{S}}{{\tau }_{N}}\le \frac{\alpha }{1-\alpha }\)), the “evaluation depth effect” from naïve consumers will exceed that of the “evaluation breadth effect” from sophisticated consumers. Thus, to encourage naïve consumers to evaluate products in greater depth, the platform provides a search environment with lower search costs (smaller s*). Suppose the proportion of naïve consumers is small (\(\frac{{e}^{2}}{{e}^{2}-1}\frac{{\tau }_{S}}{{\tau }_{N}} > \frac{\alpha }{1-\alpha }\)). In this case, the “evaluation breadth effect” from sophisticated consumers will exceed that of the “evaluation depth effect” from naïve consumers and the platform will choose to make sure the sophisticated consumers will not evaluate too many products. In this search environment, rational but naïve consumers choose to evaluate products partially.

Proposition 3 also shows how the proportion of naïve consumers affects the welfare distribution among different types of consumers. If there is a sufficiently large number of naïve consumers, the platform will rationally lower the search cost to attract naïve consumers to evaluate the products in greater depth. Subsequently, sophisticated consumers evaluate more products, increasing the expected welfare of both naïve and sophisticated consumers. If the proportion of naïve consumers is small, the platform will increase the search costs to prevent sophisticated consumers from evaluating too many products. Naïve consumers must partially evaluate products and face uncertainty about the value of the products they purchase. Similar to Dukes and Liu (2016), Proposition 3 also illustrates that greater product differentiation increases consumers’ benefits by evaluating more products at greater depths.

Discussions

Personalized recommendations

In Section 2 we assume that all consumers face the same search environment provided by an online shopping platform. However, platforms can reduce some (but not all) consumer search costs by providing personalized recommendations (Choudhary and Zhang, 2023) or targeted search results based on individual consumers’ historical data (e.g., search and purchase histories) (De Corniere, 2016). Platforms can also increase the precision of recommendations by improving the search algorithms (Zhong, 2023). In this section, we allow the platform to provide personalized recommendations to different types of consumers to examine how the ability to treat different types of consumers affects a platform’s search design.

In this section, the environment is identical to that of the benchmark model, except that the platform can provide different personalized recommendations to naïve and sophisticated consumers, causing them to potentially incur different search costs. Specifically, we assume that the search cost for naïve consumers with an evaluation plan (bN, dN) is (1 − sN)τbd2. Thus, a sophisticated consumer’s search cost is (1 − sS)τbd2. The difference between sN and sS indicates that the platform can provide recommendations to the two types of consumers that fit them differently. Then naïve consumers’ optimal evaluation depth (τ = τN) is given by

Naïve consumers’ optimal evaluation breadth (τ = τN) is

Similarly, sophisticated consumers’ optimal search depth and breadth are the same as those in Equations (15) and (14), except that the platform’s effect lowers consumers’ search costs s = sS. Consumers’ optimal search depth and breadth decrease with higher search costs. The sellers choose their optimal pricing strategy according to Lemma 2. In this scenario, the sellers’ optimal pricing strategy depends on each of the two types of consumer evaluation plans. According to Lemma 3, it is convenient to show that for sellers optimal price \(\hat{p}({s}_{N},{s}_{S})\), we have \(\frac{\partial \hat{p}({s}_{N},{s}_{S})}{\partial {s}_{S}} \,>\, 0\) when \(0\le {s}_{S}\le 1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{S}}{e}^{-2}\). Furthermore, \(\frac{\partial \hat{p}({s}_{N},{s}_{S})}{\partial {s}_{S}}\le 0\) when \(1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{S}}{e}^{-2} \,<\, {s}_{S}\le 1\). Similarly, \(\frac{\partial \hat{p}({s}_{N},{s}_{S})}{\partial {s}_{N}} \,>\, 0\) when \(0\le {s}_{N}\le 1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{N}}{e}^{-2}\), and \(\frac{\partial \hat{p}({s}_{N},{s}_{S})}{\partial {s}_{N}}\le 0\) when \(1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{N}}{e}^{-2}\, <\, {s}_{N}\le 1\).

The platform’s profit aligns with sellers’ prices. When the platform could design different search environments for both naïve and sophisticated consumers, Proposition 4 provides the optimal search design for the platform.

Proposition 4

Let n > e2, and sN, sS ∈ [0, 1]. In the equilibrium, the platform chooses search designs \({s}_{N}^{* }=1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{N}}{e}^{-2}\) and \({s}_{S}^{* }=1-\frac{\mu }{{\tau }_{S}}{e}^{-2}\).

Proposition 4 suggests that if a platform can distinguish between naïve and sophisticated consumers and provide them with personalized search environments, it will provide a search environment with lower search costs to naïve consumers. For example, a platform can provide personalized recommendations to naïve consumers. Intuitively, to encourage deeper evaluation of products by naïve consumers, the platform has an incentive to lower their search costs. Simultaneously, the platform will increase sophisticated consumers’ search costs to prevent them from evaluating more products. The platform’s ability to provide different search environments to different consumer types enables it to eliminate the trade-off presented in Proposition 3.

Number of sellers

The benchmark model focuses on the case in which n > e2. This extension relaxes this assumption and assumes n ≤ e2, which means that the number of sellers on the platform is small. With the platform’s search design s, naïve and sophisticated consumers’ optimal search plans are given in the following lemma:

Lemma 4

Given n ≤ e2 and the platform’s search environment s ∈ {0, 1}, all consumers’ optimal search breadth is n, and the naïve consumer’s optimal search depth is

Likewise, sophisticated consumers’ optimal search depth is

According to Lemma 4, because the number of sellers is small, consumers always evaluate all the available products on the platform. We then obtain the seller’s optimal pricing strategy regarding consumers’ evaluation plans as follows:

From the seller’s optimal pricing strategy, we find that the price increases with the platform’s search design s. The economic intuition here is that reducing consumers’ search costs can only lead to a deeper search. Thus, the platform will not have to trade off between the “evaluation depth effect” and the “evaluation breadth effect.” The platform will select a search design that ensures all consumers evaluate the product in full depth. Proposition 5 illustrates the platform’s optimal search design and different types of consumers’ optimal evaluation plans.

Proposition 5

If n ≤ e2, the platform’s optimal search design is \({s}^{* }\in [1-\frac{\mu }{n{\tau }_{N}},\le 1]\), and the naïve and sophisticated consumers optimal evaluation plan is {(b*, d*)∣b* = n, d* = 1}.

This proposition shows that the main results of the benchmark model require that the number of sellers on the platform is not too small. Otherwise, consumers will evaluate all products on the intermediary platform, regardless of whether they are naïve or sophisticated. In the real world, there are too many products on a platform; normally, we cannot evaluate all products. Thus, our assumption of a “large number of sellers” in the benchmark model holds true in most cases.

Empirical study

To support the theoretical predictions with empirical evidence, this section presents a study to demonstrate how consumer heterogeneity pertaining to naïvety affects their search behaviors on a real-world online shopping platform. The analysis utilizes individual-level click stream data from JD.com, one of China’s leading e-commerce platforms.

Data

The original dataset contains more than 1 million anonymous users’ behaviors from February 1, 2018 to April 15, 2018. Given that most of February 2018 was the Chinese Spring Festival holiday, we chose our data sample to span from March 1, 2018 to April 15, 2018. Thus, no significant shocks occurred during our sample period. We also deleted observations with missing values (s) for the major variables. In our final data sample, there were 1,124,108 anonymous users with demographics, including age, gender, registration time, and the level of user’s account. The data also include user actions such as browsing the product page (89.1%), placing an order (5.9%), following(1.2%), commenting(2.2%), and adding items to a shopping cart(1.6%).

In our final sample data period, products consumers browsed were distributed across 81 product categories, among which the category with the highest number of observations of actions had 11,628,793 observations. We can only observe unique IDs for different product categories and cannot see the specific categories to which they belong. In our baseline empirical analysis, we use data from the category with the highest number of observations (Separating sample data). For comparison, we use the entire sample dataset with 81 categories in the robustness test section (Pooling sample data).

The empirical model

In this section, we specify two reduced-form linear regression models and discuss the relationship between consumer types and their search behaviors (search depth and search breadth). In the first regression model, we characterize consumers as naïve or sophisticated based on their membership levels. The baseline linear regression model is as follows:

In Models (16) and (17), Depthi is consumer \(i^{\prime} s\) search depth, Breadthi is the search breadth, and Naivei indicates whether consumer i is naïve. Controlsj refers to the control variables, which are mainly consumer demographics, including consumers’ age level (Age, Levels 1–6), the square of Age (Age2), consumers’ gender (Gender), and the cities where consumers live (City). In the second regression model, for comparison, we specify consumer membership level directly as the main explanatory variable. The regression model is as follows:

where Userleveli is the consumer membership level during the sample period. Membership levels range from Levels 1 (low) to Level 7 (high).

Search depth

In our study, consumer search depth indicates how “deeply” a consumer evaluates a product. Referring to Ursu et al. (2020), we measure a consumer’s search depth by how much time they spend browsing a product’s page. The data include the exact time stamp of every consumer action; thus, we can obtain consumers’ search depth by using the difference in the time stamps. The precision of the timestamp for each behavior is measured in minutes. From the data, we can observe the beginning of an individual clicking on a certain product page; however, we do not know when they leave the page. Thus, one concern about our method for obtaining the search depth is the measurement error. To handle this issue, similar to Ursu et al. (2020), we collapse the “search depth” above 60 minutes since it is more likely to include other activities that are not related to viewing the product. The upper bond of our “search depth” is higher than the “search duration” of restaurant viewing Ursu et al. (2020) since the information product page in “JD.com” is much richer than the restaurant page. In the sample of Fradkin (2017), the median searcher on Airbnb spent 58 minutes browing the website before sending an inquiry.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of consumer search depth. We found that the variation in consumer search depth is large. The distribution has a large right tail, similar to the data pattern in Ursu et al. (2020). The significant variation in consumer search depth also helps us identify the influence of consumer naïvety.

Search breadth

In Section 2, consumer “search breadth” refers to the number of products a consumer has evaluated before purchasing. Our data contain every click record of individual consumers; thus, we can obtain the number of product pages a consumer has browsed directly. Similar to the measurement of search depth, here we also collapse the “search breadth” that is above 100 to eliminate the influence of “click farming” in e-commerce platforms (Jiang et al. 2022). Figure 3 presents the distribution of consumers’ search breadth for a certain product on “JD.com”. The distribution of consumers’ search breadths also shows large variation and a large right tail.

Naïve vs. sophisticated consumers

In the theoretical analysis, we showed that due to the search cost, naive and sophisticated consumers’ search behaviors differ. In our final sample, we could observe the demographics of individual users on “JD.com”. One important characteristic of individuals was consumers’ membership levels or tiers (Userlevel), which reflect their historical behaviors in “JD.com”. Each user’s membership level is determined by their past purchases (Shen et al. 2020), and consumers are distributed among seven levels of membership (Levels 1–7) in our sample period. If a consumer has used “JD.com” more frequently, their membership level will be higher, which indicates that they are more “experienced.” This attribution helps to distinguish between naïve and sophisticated consumers. In the sample period, “JD.com’s” membership system contains seven tiers. For consistency with the theoretical analysis, we divided consumers into two groups. If a consumer’s membership level is less than or equal to level 4, we characterize them as “naive consumers” (Naive = 1). Conversely, we classify consumers with higher membership levels as “sophisticated consumers” (Naive = 0). Our final sample consisted of 335,334 naïve consumers and 788,774 sophisticated consumers.

Figure 4 shows the difference in search depth and breadth between naïve and sophisticated consumers. We find that compared to sophisticated consumers, both naïve consumers’ search depth and breadth are slightly lower. To more precisely investigate the relationship between consumer types and their search behaviors, we conduct a linear regression of consumers’ search depth and breadth on their types. The primary regression results are presented in the following sections.

Control variables

The control variables in our empirical model are primarily consumer demographics. To be more specific, the demographic variables are as follows:

Age: the level of consumers’ age (ranging from 1 to 6, with 1 being the youngest user). Considering that the older a consumer is, the less familiar they may be with online shopping, we also add the quadratic term for Age (Age2) as a control variable.

Gender: the gender of individual consumers (0: female, 1: male, −1: unknown).

City: the level of cities where the consumers are located (range = 1–6). For example, Beijing and Shanghai are Tier 1 cities in China. In our data, the less developed a city, the larger its city level.

Table 1 presents the summary statistics for the variables used in the empirical analysis. In Table 1, Panel A, which presents the data in a certain industry, we can find that the average consumer browsed 21.75 products in our sample period and spent 24.44 minutes evaluating a single product. In the pooled sample (Panel B), the average search breadth and depth were slightly lower. The average membership level was 5.00.

Main results

We estimated the empirical models using data in the category with the largest number of observations. Table 2 reports the results. Specifically, in Table 2, Columns (1) and (3) report the results of Models (17) and (19), respectively. Columns (2) and (4) report the results of Models (16) and (18), respectively.

Columns (1) and 2 show that the coefficient of Naive is negative (-0.1871) and statistically significant at the 1% level. This negative coefficient indicates that the search breadth of naïve consumers is significantly smaller than that of sophisticated consumers. Specifically, naïve consumers’ search breadth is, on average, 18.71% smaller than that of sophisticated consumers. Furthermore, in column (2), the coefficient of Userlevel is positive (0.0431) and significant at the 1% level, indicating that a more sophisticated consumer evaluates more products. The results in columns (1) and (2) of Table 2 support the theoretical predictions presented in Proposition 1 that, compared to naïve consumers, sophisticated consumers tend to evaluate more products on the platform because they incur lower search costs.

Column (3) shows that the coefficient of Naive is -0.1148 and is significant at the 1% level. In other words, the search depth of naïve consumers is significantly lower than that of sophisticated consumers. The coefficient of Userlevel in column (4) is also significant and positive, indicating that more sophisticated consumers will evaluate products more deeply on “JD.com”. In summary, the results in columns (3) and (4) of Table 2 provide empirical evidence for the prediction presented in Proposition 1 that sophisticated consumers tend to evaluate products at higher depths than naïve consumers. In the empirical analysis, we also controlled for individual characteristics, age, gender, and the level of the city where the consumers lived.

Endogeneity

In the baseline empirical model, an endogeneity problem may arise due to omitted variables. For example, consumers who like to shop online might have a higher level of membership in “JD.com” and also spend more time searching for products. To handle the potential endogeneity issue, we propose an instrument variable based on the consumer’s registration time on “JD.com”.

On the one hand, if a consumer registered on “JD.com” earlier, their membership level is more likely to be higher. However, registration time does not correlate with consumer search behaviors. We take the difference between 1 May 2018 and the registration time of individual consumers (Registration) as the instrument variable for consumers’ type ("naïve” or “sophisticated”) and the level of membership. We then estimate the models (17), (19), (16), and (18) using the two-stage least squares method (2SLS). Table 3 shows the results of the 2SLS estimation. Consistent with the baseline empirical model, in this section, we use the data from the “Separating Sample Data.”

In Table 3, columns (1) and (3) report the 2SLS results of models (17) and (16). We find that the coefficient of Naive is significantly negative, which is consistent with previous findings related to consumer types and their search breadth and depth. The signs of Userlevel in columns (2) and (4) confirm the findings of the previous baseline model.

Robust test

In this section, we re-estimate the baseline regression models by pooling all data into 81 product categories to test the robustness of the results in our baseline model.

Columns (1), (2), (3), and (4) in Table 4 report the regression results of Models (17), (19), (16), and (18), respectively, using the pooling data. The coefficients of Naive in columns (1) and (3) of Table 4 are significantly negative, and the coefficients of Userlevel in Columns (2) and (4) are significantly positive. The results in Table 4 are consistent with the findings of our baseline model, supporting the predictions in Proposition 1. Therefore, the findings of the baseline model are robust.

Conclusion

Platforms’ design can affect sellers, buyers, and social welfare. This study investigated the strategic search design of a digital shopping intermediary with heterogeneous consumers. In this study, we define a platform’s search design by controlling for consumer search costs. Consumers may make mistakes when assessing the value they derive from a product, especially when facing a huge number of products available on the platform. Naïve consumers’ limited ability to assess product value influences their search behavior and consequently affects sellers’ pricing strategies and the platform’s strategic search design.

More specifically, we show that compared to sophisticated consumers, naïve consumers tend to evaluate fewer products at a lower depth. The sellers’ optimal price might be higher or lower, depending on the magnitude of the difference in search costs between naïve and sophisticated consumers. If naïve consumers’ evaluation costs are moderately higher than those of sophisticated consumers, the search breadth of naïve consumers lowers the average search breadth of the market, and sellers can charge a higher price. However, if the evaluation cost difference between naïve and sophisticated consumers is sufficiently large, naïve consumers will evaluate the product at a lower depth. Thus, to attract naïve consumers, sellers must charge lower prices.

Since digital shopping platforms normally derive revenue from third-party sellers, their optimal design involves a trade-off between the search depth of naïve consumers and the search breadth of sophisticated consumers. The platform lowers the search cost to ensure that naïve consumers evaluate the product at a greater depth but not too low to prevent sophisticated consumers from evaluating too many products. We also show that if the proportion of naïve consumers is sufficiently large, the platform have to lower search costs to attract naïve consumers. Thus, the platform has an incentive to educate naïve consumers. When a platform can provide different search environments to different types of consumers, it lowers naïve consumers’ search costs while maintaining sophisticated consumers search costs at a higher level. Based on individual-level data from the real world, we find empirical evidence that sophisticated consumers tend to evaluate more products at higher depths than naïve consumers.

In the theoretical model, we investigate the difference between naïve and sophisticated consumers’ search behaviors and seek to determine how naïve consumers affect the distribution of welfare between consumers. However, as argued by Goldfarb and Tucker (2019), instead of charging different customers different prices, intermediaries may prefer to show different customers more profitable personalized advertising. For example, if the platform can distinguish “naïve consumers” from “sophisticated consumers,” it might have the incentive to recommend products with a high-profit margin but this may not best match the naïve consumer’s preference. The theoretical model in this study does not capture the distortion of the recommendation system (or advertising system) provided by a platform. This issue should be addressed in future studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

We assume that the value of v is substantial enough to incentivize all consumers to engage in the search process.

The key difference is with Lemma 1 in Dukes and Liu (2016) is that we assume τ = τN or τ = τS.

References

Armstrong M, Chen Y (2009) Inattentive consumers and product quality. Journal of the European Economic Association 7(2-3):411–422

Armstrong M, Vickers J (2012) Consumer protection and contingent charges. Journal of Economic Literature 50(2):477–93

Baik SimonAnderson,A, Larson N (2023) Price discrimination in the information age: Prices, poaching, and privacy with personalized targeted discounts. The Review of Economic Studies 90(5):2085–2115

Bar-Gill O, Ferrari F (2010) Informing consumers about themselves. Erasmus L. Rev. 3:93

Barach MA, Golden JM, Horton JJ (2020) Steering in online markets: the role of platform incentives and credibility. Management Science 66(9):4047–4070

Blake T, Moshary S, Sweeney K, Tadelis S (2021) Price salience and product choice. Marketing Science 40(4):619–636

Boyacı T, Akçay Y (2018) Pricing when customers have limited attention. Management Science 64(7):2995–3014

Carlin BI (2009) Strategic price complexity in retail financial markets. Journal of Financial Economics 91(3):278–287

Chen N, Tsai H-TT (2023) Steering via algorithmic recommendations. RAND Journal of Economics 55(4): 501–518

Chen Y, Yao S (2017) Sequential search with refinement: Model and application with click-stream data. Management Science 63(12):4345–4365

Chioveanu I, Zhou J (2013) Price competition with consumer confusion. Management Science 59(11):2450–2469

Choi M, Dai AY, Kim K (2018) Consumer search and price competition. Econometrica 86(4):1257–1281

Choudhary V, Zhang Z (2023) Product recommendation and consumer search. Journal of Management Information Systems 40(3):752–777

Cullen Z, Farronato C (2021) Outsourcing tasks online: Matching supply and demand on peer-to-peer internet platforms. Management Science 67(7):3985–4003

De Corniere A (2016) Search advertising. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 8(3):156–88

Dinerstein M, Einav L, Levin J, Sundaresan N (2018) Consumer price search and platform design in internet commerce. American Economic Review 108(7):1820–59

Dukes A, Liu L (2016) Online shopping intermediaries: The strategic design of search environments. Management Science 62(4):1064–1077

Eliaz K, Spiegler R (2011a) Consideration sets and competitive marketing. The Review of Economic Studies 78(1):235–262

Eliaz K, Spiegler R (2011b) On the strategic use of attention grabbers. Theoretical Economics 6(1):127–155

Fradkin A (2017) Search, matching, and the role of digital marketplace design in enabling trade: Evidence from airbnb. Working Paper

Gabaix X, Laibson D (2006) Shrouded attributes, consumer myopia, and information suppression in competitive markets. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 121(2):505–540

Gamp T, Krähmer D (2022) Competition in search markets with naive consumers. The RAND Journal of Economics 53(2):356–385

Gardete P, Hunter M (2020) Guiding consumers through lemons and peaches: An analysis of the effects of search design activities. Working Paper

Ghose A, Ipeirotis PG, Li B (2019) Modeling consumer footprints on search engines: An interplay with social media. Management Science 65(3):1363–1385

Goldfarb A, Tucker C (2019) Digital economics. Journal of Economic Literature 57(1):3–43

Grubb MD (2015) Consumer inattention and bill-shock regulation. The Review of Economic Studies 82(1):219–257

Gurun UG, Matvos G, Seru A (2016) Advertising expensive mortgages. The Journal of Finance 71(5):2371–2416

Hagiu A, Jullien B (2011) Why do intermediaries divert search? The RAND Journal of Economics 42(2):337–362

Hagiu A, Jullien B (2014) Search diversion and platform competition. International Journal of Industrial Organization 33:48–60

Hagiu A, Teh T-H, Wright J (2022) Should platforms be allowed to sell on their own marketplaces? The RAND Journal of Economics 53(2):297–327

Heidhues P, Köszegi B (2018) Behavioral industrial organization. Handbook of Behavioral Economics: Applications and Foundations 1 1:517–612

Heidhues P, Köszegi B, Murooka T (2016) Inferior products and profitable deception. The Review of Economic Studies 84(1):323–356

Jiang C, Zhu J, Xu Q (2022) Dissecting click farming on the Taobao platform in China via PU learning and weighted logistic regression. Electronic Commerce Research 22(1):157–176

Kuhn P, Mansour H (2014) Is internet job search still ineffective? The Economic Journal 124(581):1213–1233

Kuksov D, Villas-Boas JM (2010) When more alternatives lead to less choice. Marketing Science 29(3):507–524

Liu L, Dukes A (2016) Consumer search with limited product evaluation. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 25(1):32–55

Murooka T (2015) Deception under competitive intermediation. Working Paper

Orlov E (2011) How does the internet influence price dispersion? Evidence from the airline industry. The Journal of Industrial Economics 59(1):21–37

Parker C, Ramdas K, Savva N (2016) Is it enough? Evidence from a natural experiment in India’s agriculture markets. Management Science 62(9):2481–2503

Ru H, Schoar A (2016) Do credit card companies screen for behavioral biases? Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research

Shen M, Tang CS, Wu D, Yuan R, Zhou W (2020) Jd. com: Transaction-level data for the 2020 MSOM data driven research challenge. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management

Spiegler R (2019) Behavioral economics and the atheoretical style. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 11(2):173–194

Stango V, Zinman J (2023) We are all behavioural, more, or less: A taxonomy of consumer decision-making. The Review of Economic Studies 90(3):1470–1498

Stigler GJ (1961) The economics of information. Journal of Political Economy 69(3):213–225

Teh T-H (2022) Platform governance. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 14(3):213–54

Teh T-H, Wright J (2022) Intermediation and steering: Competition in prices and commissions. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 14(2):281–321

Teng X (2022) Self-preferencing, quality provision, and welfare in mobile application markets. Working Paper

Ursu RM, Erdem T, Wang Q, Zhang Q (2024) Prior information and consumer search: Evidence from eye-tracking. Management Science 70(12):8685–8708

Ursu RM, Wang Q, Chintagunta PK (2020) Search duration. Marketing Science 39(5):849–871

Zennyo Y (2022) Platform encroachment and own-content bias. The Journal of Industrial Economics 70(3):684–710

Zhang L (2018) Intellectual property strategy and the long tail: Evidence from the recorded music industry. Management Science 64(1):24–42

Zhong Z (2022) Chasing diamonds and crowns: Consumer limited attention and seller response. Management Science 68(6):4380–4397

Zhong Z (2023) Platform search design: The roles of precision and price. Marketing Science 42(2):293–313

Zhong ZZ (2016) Targeted search and platform design. Working Paper

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Shenzhen University (Grant no. 000001033102) and the National Social Science Fund of China - Major Project (Grant no. 23&ZD088).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing; CH: Visualization, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing; ZS: Resources, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, funding acquisition. All authors read, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., He, C. & Shi, Z. Platform search design with heterogeneous consumers. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 673 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04932-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04932-7