Abstract

To address the global climate crisis, the Chinese government has vigorously advanced the “Dual Carbon Goals,” which are designed to attain carbon peak and carbon neutrality by implementing comprehensive measures to reduce carbon emissions in both production and consumption sectors. These goals have been incorporated into the educational system with the objective of cultivating low-carbon and environmentally friendly behaviors among the public, particularly university students. This study examines the impact of environmental education on the low-carbon behaviors of university students in China by investigating the role of various types of environmental knowledge. Specifically, environmental knowledge is divided into three categories: System Knowledge (comprehension of environmental systems and ecological processes), Action Knowledge (knowledge of specific actions to reduce carbon emissions), and Efficacy Knowledge (awareness of the effectiveness of these actions). By leveraging a dataset from 2646 questionnaires collected from students across eight major Chinese cities, we employ Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to analyze the data. Our results indicate that while Action Knowledge and Efficacy Knowledge positively influence low-carbon behaviors, System Knowledge has a negative impact, likely due to cognitive dissonance. We propose that future environmental education should place greater emphasis on practical knowledge and take demographic characteristics into account to enhance educational effectiveness. This research not only strengthens the theoretical foundation of environmental education but also offers empirical support for policy-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the world’s largest carbon emitter, China released 11.48 billion tons of carbon in 2022, representing one-third of global emissions (Wu et al., 2023). To tackle this challenge, the Chinese government has established dual carbon goals and adopted comprehensive measures. These efforts aim to enhance energy conservation and reduce emissions in production, while also promoting environmentally friendly and sustainable lifestyle changes among consumers. In terms of industrial policy, the focus has been on optimizing and upgrading the industrial structure, complemented by nationwide low-carbon education initiatives.

The United Nations Environment Program’s “Emissions Gap Report 2020” reveals that two-thirds of global carbon emissions originate from consumer activities (Nielsen et al., 2022). This is corroborated by Chinese research, which shows that residential consumption accounts for over 50% of total carbon emissions, making it the second-largest source after industry (Cao et al., 2019). As a result, scholars argue that achieving China’s dual carbon goals requires fostering low-carbon, green, and environmentally friendly consumption patterns among the public (Yan et al., 2021). This transformation hinges on lifestyle changes, with education being a crucial tool for cultivating low-carbon habits.

In the education sector, the Chinese government has emphasized the importance of instilling low-carbon and environmentally friendly behaviors from a young age. Since 2014, environmental education has been integrated into the “Moral Education Outline” for primary and secondary schools and actively promoted through campus activities. Universities have also placed significant emphasis on promoting environmental behaviors such as waste sorting and the “Clean Plate Campaign” (Kuang & Lin, 2021; Qian et al., 2021). However, the question remains whether these educational policies and initiatives can achieve their intended goals. This paper seeks to provide answers through both theoretical analysis and empirical research.

Exploring this theme offers several benefits. First, it provides unique strategies and insights from China in the global fight against climate change. Second, it contributes to the existing body of knowledge on environmental education, offering valuable references and insights for other countries as they develop and implement their own environmental education policies.

From a theoretical standpoint, the “Knowledge—Attitude—Behavior” framework posits that knowledge forms the basis for shaping attitudes, which subsequently drive behavioral change (Hungerford & Volk, 1990). Environmental education, therefore, hinges on imparting environmental knowledge to foster eco-friendly behaviors. This paper examines how the dissemination of low-carbon knowledge through China’s environmental education impacts students’ low-carbon behaviors. Since 2014, China has integrated environmental education into primary and secondary schools, aiming to instill ecological civilization concepts in students by incorporating ecological protection, resource conservation, and environmental preservation into their learning and daily lives. The goal is to develop low-carbon and environmentally friendly lifestyle habits that persist into adulthood. However, the outcomes have been underwhelming. For instance, the average annual carbon emissions per college student in China have reached 4.1 tons (4100 kilograms) (Liu Yixin, 2019). These emissions are distributed across five main areas: clothing (3.3%), food (53.8%), housing (0.3%), transportation (1.8%), daily goods usage (40.8%), and others (2.42%) (Pang Jiao, 2023). This translates to annual per capita emissions of 135.3 kilograms for clothing, 2205.8 kilograms for food, 12.3 kilograms for housing, 73.8 kilograms for transportation, 1672.8 kilograms for daily goods usage, and 99.22 kilograms for other categories.

Food and daily goods consumption are the primary sources of carbon emissions among college students. Food waste, in particular, is a pressing issue, with an average of 8.4 kilograms of carbon emissions per person resulting from food waste behavior (Pérez et al., 2023; Qian et al., 2022). Additionally, alcohol consumption, overeating, and the inefficient use of daily goods contribute 291.536 kilograms, 454.651 kilograms, and 530.351 kilograms of carbon emissions per person, respectively (Junting et al., 2024).

In total, unsustainable consumption behaviors among Chinese college students generate an additional 1284.938 kilograms of carbon emissions annually, exceeding one-third of the average annual per capita emissions. Given that China has over 40 million college students (Luo et al., 2023), widespread adoption of a low-carbon lifestyle could reduce carbon emissions by 51.397 million tons per year. This underscores the significant potential of college students to reduce their carbon footprint and promote sustainable development, highlighting the urgency of advocating for a low-carbon lifestyle.

Most current college students in China, having enrolled after 2014, have been exposed to environmental education throughout their primary and secondary schooling. However, this education has not significantly altered their behavior, a phenomenon known as “cognitive dissonance” (Festinger, 1962). Scholars have observed a disconnect between college students’ environmental awareness and their actions, attributing it to factors such as social influence (Bentler et al., 2023), values (Ullah et al., 2024), and resource facilities (C. C. Li et al., 2023a). Yet, research on how knowledge shapes behavior and how environmental education can drive behavioral change among students remains insufficient. Given that higher education builds on earlier educational experiences, it appears that current environmental education has not effectively cultivated low-carbon behaviors in college students.

This paper, grounded in the “Knowledge—Attitude—Behavior” theory and the “Motivation—Capability—Opportunity” model, explores how educational interventions can enhance students’ environmental awareness and motivate them to adopt low-carbon behaviors. It addresses the following questions: (1) How do cognitive disparities in low-carbon behavioral practices among Chinese college students arise? (2) How does environmental knowledge influence the low-carbon behavioral choices of Chinese college students? (3) How can environmental education be designed to effectively enhance the low-carbon practice capabilities of Chinese college students?

The manuscript is structured as follows: the section “Literature review” provides an exhaustive review of the literature, integrating key studies to set the academic backdrop for our research. Section “Research design” outlines the research methodology, including data collection protocols and analytical strategies. Section “Results and discussion” delves into a thorough examination of our findings, elucidating the complex interplay between environmental knowledge and low-carbon behaviors. Section “Conclusion and limitation” synthesizes the study’s conclusions, contrasting them with current literature and offering practical insights and strategic recommendations. This structured approach aims to provide a solid theoretical foundation and pragmatic implications for enhancing environmental education and promoting low-carbon behaviors, thereby contributing to global efforts to achieve sustainable development.

Literature review

Environmental education is pivotal in shaping the environmental behaviors of modern citizens, which has spurred extensive research into its relationship with individual actions. This research generally falls into two main categories. First, scholars examine how various factors within the environmental education process influence individual behaviors. This category can be further divided into two subcategories: one focuses on the psychological traits of learners, such as personality (Dalvi-Esfahani et al., 2020), emotions (Raeisi et al., 2018), and cognition (Duerden & Witt, 2010), while the other explores the impact of external factors, such as government policies (Wang et al., 2023), environmental infrastructure (Conway et al., 2021), and social norms (Vesely & Klöckner, 2017). These areas are increasingly integrating individual demographic characteristics for a more comprehensive analysis (Varela-Candamio et al., 2018). The second category of research examines the methods and strategies of environmental education, including teaching approaches (Ferreira et al., 2020; Kamil et al., 2020) and the effectiveness of modern technologies like MOOCs (Areias et al., 2023). These studies highlight the importance of interdisciplinary cooperation and provide a scientific basis for developing effective environmental education policies.

A significant body of literature has explored how social norms (Wu et al., 2022), conformity psychology (Li, 2022), policy regulations (Liu et al., 2019), and other factors influence college students’ environmental behaviors. These factors are often combined with students’ cognitive levels (Wang et al., 2020), value concepts (Shafiei & Maleksaeidi, 2020), and behavioral habits (Shi et al., 2019) to analyze their collective impact on environmental actions. These studies offer a multidimensional perspective and practical support for developing effective environmental education strategies.

However, existing research has largely overlooked the impact of the content of environmental education on students’ behaviors. There is a notable gap in understanding how different types and qualities of environmental knowledge influence college students’ behaviors. Additionally, the mechanisms through which environmental knowledge translates into action remain underexplored. To address this gap, this paper examines the long-term effects of environmental education on college students in China, who have all received such education since 2014. By analyzing different dimensions of environmental knowledge and their impact on students’ behaviors, this study provides insights into the effectiveness of current educational strategies and offers valuable feedback for environmental education globally. The analysis is summarized in Table 1 to provide a clear overview and framework for readers.

Research design

Theoretical analysis and proposal of research hypotheses

Theoretical analysis

This study examines the impact of low-carbon knowledge on the implementation of low-carbon behaviors among college students through a two-tiered analysis. We first establish a theoretical framework and then delve into the individual components within the model.

First Tier: Derivation of the model framework

Based on the “Knowledge—Attitude—Behavior” framework, an individual’s environmental knowledge is crucial in shaping their ecological attitudes, which in turn influence their low-carbon behaviors (Hungerford & Volk, 1990). Attitudes, which reflect a person’s evaluative predispositions towards certain objects or ideas, can be seen as a psychological preparation for action. From a social psychology perspective, attitudes and behavioral intentions are often interchangeable. Additionally, the “Motivation—Capability—Opportunity” model highlights that an individual’s actions, given sufficient opportunity, are driven by a combination of their motivation to act (in this case, low-carbon intention) and their capability to do so (Olander & Thogersen, 1995). The former theory emphasizes the motivational aspect of intentions in initiating behavior, while the latter underscores the role of capability in the actualization of behavior. In this context, low-carbon intention (LCI) and low-carbon capability (LCC) act as intermediaries between knowledge acquisition and the enactment of low-carbon behaviors. This study constructs an analytical framework in which LCI and LCC facilitate the translation of environmental knowledge into low-carbon behaviors (as depicted in Fig. 1). For college students, who have not yet fully integrated societal norms and have not established entrenched lifestyle habits, the impact of knowledge is more direct and unadulterated, with their attitudes and behaviors being more immediately shaped by their knowledge levels (Yan et al., 2015). By focusing on college students, this research aims to uncover the explicit connection between environmental knowledge and low-carbon behavior. In doing so, this study seeks to lay a scientific foundation for crafting effective environmental education strategies and to bolster the pursuit of dual carbon objectives.

Second Tier: Elaboration of variable composition

Drawing from the work of Frick et al. (2004), this study categorizes low-carbon knowledge into three distinct types: System Knowledge (SK), Action Knowledge (AK), and Effective Knowledge (EK). System Knowledge (SK) refers to an individual’s understanding of natural conditions, including environmental systems and ecological processes—the “know what” aspect of knowledge. For example, recognizing that excessive CO2 emissions significantly contribute to global warming falls under this category. Action Knowledge (AK) pertains to the understanding of personal behavioral choices and specific practices, which is the “know how” component. This includes knowing that taking public transportation frequently or turning off electrical devices promptly can reduce CO2 emissions. Effective Knowledge (EK) involves understanding the outcomes and benefits of specific actions, which is the “which is more effective” aspect of knowledge. For instance, knowing that energy-saving light bulbs offer 60 to 80% more electricity savings compared to incandescent bulbs is part of effective knowledge.

By differentiating knowledge variables into these three categories, this study aims to refine environmental education. System knowledge provides the foundation for understanding environmental issues, action knowledge guides individuals toward effective environmental behaviors, and effective knowledge evaluates and enhances the anticipated and actual effects of these behaviors, creating a cohesive and mutually supportive cognitive framework. This stratification allows for a more nuanced evaluation of the impact of various educational strategies on promoting low-carbon behaviors, thereby laying the theoretical groundwork for developing more impactful environmental education initiatives.

In daily life, an individual’s low-carbon behavior can be categorized into two main aspects: low-carbon conservation behavior (LCCB) and low-carbon expenditure behavior (LCEB) (Xiao et al., 2021). Low-carbon conservation behavior focuses on reducing energy consumption and improving product usage methods, which can save costs for individuals, such as lowering electricity bills. In contrast, low-carbon expenditure behavior involves purchasing low-carbon products and equipment, which increases costs at the consumption stage, such as buying energy-saving light bulbs. Situational theory suggests that individuals perceive savings and expenditures differently, with the pleasure derived from savings typically outweighing the pain of expenditures (Trichilli et al., 2021). Therefore, this study further divides low-carbon behavior into low-carbon conservation behavior related to savings and low-carbon expenditure behavior related to expenses to reflect the different psychological feelings and economic considerations individuals may face when implementing low-carbon behaviors.

Through this refined theoretical framework, this study aims to provide a comprehensive analytical framework to understand how low-carbon knowledge can promote the implementation of low-carbon behaviors by influencing an individual’s intentions and capabilities. This framework also emphasizes the need to consider both psychological and economic factors in shaping behaviors through environmental education. The following section will propose research hypotheses based on this analytical framework and the variables derived from it.

Proposing research hypotheses

Research hypotheses are indispensable components in scientific research, serving as answers to questions derived from existing theories and research, and guiding the direction and content of the study. This research, based on theoretical analysis, categorizes the hypotheses into three parts, each exploring different theoretical relationships and mechanisms. The three parts are as follows:

-

1.

Single Path Hypotheses: These hypotheses test the direct impact of various types of knowledge on low-carbon behaviors.

-

2.

Mediation Effect Hypotheses: These hypotheses investigate the mediating roles of low-carbon intention and low-carbon capability between knowledge and behavior.

-

3.

Total Effect Hypotheses: These hypotheses examine the combined direct and indirect effects of knowledge on low-carbon behaviors.

-

(1)

Single Path Hypotheses

In exploring how knowledge shapes attitude and ultimately affects behavior, the “Knowledge—Attitude—Behavior” model provides a fundamental framework, emphasizing the role of knowledge in forming positive attitudes and promoting goal-directed behaviors. According to the classic theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991), behavioral intention is seen as the immediate cause of behavior and serves as a mediating variable between individual psychological factors and behavior. Hines (1987), further expanded this theory by proposing the responsible environmental behavior model, highlighting the impact of environmental knowledge on low-carbon behavior through behavioral intention.

However, empirical research has revealed the limitations of these theories. Mainieri et al. (1997) found that relying solely on behavioral intention to predict actual behavior is not always accurate. Bamberg and Möser (2007) also noted that despite a high number of individuals with low-carbon behavioral intentions, the proportion who act is relatively low. These findings suggest the need for a more comprehensive theoretical framework to explain the complex relationship between low-carbon awareness and behavior.

To this end, the “Motivation—Capability—Opportunity” model proposed by Olander and Thogersen (1995) offers a new perspective, emphasizing the key roles of behavioral motivation and capability in driving behavior. Rondi et al. (2021) further pointed out that even with strong behavioral intentions, the lack of capability to perform actions significantly reduces the likelihood of successfully executing those actions. Wei et al. (2016) also found that individuals with higher carbon capabilities are more likely to engage in low-carbon behaviors.

Considering this, the study focuses on college students as the research subjects, a group that not only experiences the wave of environmental education in Chinese campuses but also typically possesses strong environmental awareness and sensitivity to sustainable development issues. Thus, the college student population serves as an ideal sample for studying low-carbon behavioral intentions, with the potential to demonstrate leadership in forming and practicing low-carbon behaviors. By deeply analyzing this group, the study aims to reveal how knowledge can be transformed into actual behaviors through attitudes, providing theoretical and practical guidance for promoting a low-carbon lifestyle.

Based on the theoretical analysis, this study constructs a multidimensional knowledge system that includes System Knowledge (SK), Action Knowledge (AK), and Effective Knowledge (EK), and distinguishes between low-carbon conservation behavior (LCCB) and low-carbon expenditure behavior (LCEB). On this basis, the study proposes a series of hypotheses to explore how low-carbon knowledge affects low-carbon behaviors through the dual mediation of low-carbon intention and capability. These hypotheses not only help refine the theoretical model of low-carbon behaviors but also offer new strategies and methods for promoting such behaviors.

H1a: System Knowledge positively promotes low-carbon intention.

H1b: System Knowledge positively promotes low-carbon capability.

H1c: Action Knowledge positively promotes low-carbon intention.

H1d: Action Knowledge positively promotes low-carbon capability.

H1e: Effective Knowledge positively promotes low-carbon intention.

H1f: Effective Knowledge positively promotes low-carbon capability.

H1g: Low-carbon intention positively promotes low-carbon conservation behavior.

H1h: Low-carbon intention positively promotes low-carbon expenditure behavior.

H1i: Low-carbon capability positively promotes low-carbon conservation behavior.

H1j: Low-carbon capability positively promotes low-carbon expenditure behavior.

-

(2)

Mediation Effect Hypotheses

In line with the research objectives and the hypotheses proposed earlier, this study puts forth the following mediation effect hypotheses:

H2a: System Knowledge affects low-carbon conservation behavior through low-carbon intention (based on H1a, H1g).

H2b: System Knowledge affects low-carbon expenditure behavior through low-carbon intention (based on H1a, H1h).

H2c: System Knowledge affects low-carbon conservation behavior through low-carbon capability (based on H1b, H1i).

H2d: System Knowledge affects low-carbon expenditure behavior through low-carbon capability (based on H1b, H1j).

H2e: Action Knowledge affects low-carbon conservation behavior through low-carbon intention (based on H1c, H1g).

H2f: Action Knowledge affects low-carbon expenditure behavior through low-carbon intention (based on H1c, H1h).

H2g: Action Knowledge affects low-carbon conservation behavior through low-carbon capability (based on H1d, H1i).

H2h: Action Knowledge affects low-carbon expenditure behavior through low-carbon capability (based on H1d, H1j).

H2i: Effective Knowledge affects low-carbon conservation behavior through low-carbon intention (based on H1e, H1g).

H2j: Effective Knowledge affects low-carbon expenditure behavior through low-carbon intention (based on H1e, H1h).

H2k: Effective Knowledge affects low-carbon conservation behavior through low-carbon capability (based on H1f, H1i).

H2l: Effective Knowledge affects low-carbon expenditure behavior through low-carbon capability (based on H1f, H1j).

-

(3)

Total Effect Hypotheses

H3a: System Knowledge has a total promoting effect on low-carbon conservation behavior (based on H2a, H2c).

H3b: System Knowledge has a total promoting effect on low-carbon expenditure behavior (based on H2b, H2d).

H3c: Action Knowledge has a total promoting effect on low-carbon conservation behavior (based on H2e, H2g).

H3d: Action Knowledge has a total promoting effect on low-carbon expenditure behavior (based on H2f, H2h).

H3e: Effective Knowledge has a total promoting effect on low-carbon conservation behavior (based on H2i, H2k).

H3f: Effective Knowledge has a total promoting effect on low-carbon expenditure behavior (based on H2j, H2l).

Given that this study primarily targets college students as the research sample, it also considers the impact of demographic characteristics on behavior by incorporating four demographic characteristics into the analysis: gender and age, which are natural student characteristics, and academic stage and academic inclination, which are specific to the college student population. Further details are elaborated in the subsequent sections.

In summary, the establishment of the above hypothesis system ultimately leads to the development of the conceptual model for this paper, as shown in Fig. 2. The validation of this model reveals how different dimensions of knowledge influence low-carbon behaviors through the mediating variables of intention and capability, as well as how demographic characteristics affect this process. These findings provide theoretical and practical guidance for the formulation of environmental education strategies and the promotion of low-carbon lifestyles, contributing to the advancement of sustainable development and environmental protection efforts.

Measurement of variables and research methods

One of the primary goals of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of environmental education in primary and secondary schools. Since students at these levels have not yet completed their education, conducting direct surveys among them would not be appropriate. In contrast, college students have completed their primary and secondary education and can serve as representative samples who have received comprehensive environmental education. Surveying college students can more effectively reflect the long-term impact and outcomes of early environmental education. Therefore, this research aims to use questionnaires to survey college students and collect data to analyze and evaluate the effectiveness of environmental teaching strategies in primary and secondary schools and their potential impact on environmental awareness and behavior.

Based on the research objectives and path hypotheses proposed earlier, seven constructs have been identified: System Knowledge (SK), Action Knowledge (AK), Effective Knowledge (EK), Low-carbon Intention (LCI), Low-carbon Capability (LCC), Low-carbon Conservation Behavior (LCCB), and Low-carbon Expenditure Behavior (LCEB). The items corresponding to these constructs and their sources are listed in Table 2. The questionnaire items are designed based on existing literature, expert opinions, the purpose of the study, and the local context of Chinese society. To facilitate the understanding of the questionnaire items by the respondents, a Likert five-point scale is used to measure the variable values, ranging from 1 to 5, representing “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “neutral,” “agree,” and “strongly agree,” respectively. Demographic characteristics of the subjects are also measured using the questionnaire, including gender (1 for male, 2 for female), age, academic inclination (1 for humanities and social sciences, 2 for natural sciences), and academic stage (1 for undergraduate, 2 for master’s, 3 for doctoral).

Given the categorical variables involved in this study, such as academic inclination and gender, generalized structural equation modeling (GSEM) is employed for modeling and analysis. There are generally two methods for estimating parameters of structural equation models: covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) (Wang et al., 2023) and partial least squares-based structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (Fernandez et al., 2020). Researchers view these two methods as complementary. CB-SEM is more appropriate when the research model is theoretically validated, variables are reflective constructs, and the sample data adheres to the assumption of normal distribution (Zhang & Zheng, 2023). PLS-SEM estimation is recommended for research purposes involving prediction or exploratory analysis, or when variables are formative or mixed constructs, especially when data may not follow the assumption of normal distribution (Wang et al., 2023). Hair et al. (2011) argue that the PLS-SEM estimation procedure is superior to CB-SEM. Since the variables and the model of this study are not based on established theories and the nature of this research is exploratory, the PLS-SEM estimation procedure is selected as the data analysis method. Given that smart-PLS is a structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis software based on partial least squares (PLS), it is capable of effectively addressing issues such as multicollinearity among variables and non-normal distribution of data (Hair et al., 2020). Therefore, this study selects smart-PLS as the statistical analysis tool. The version used in this study is smart-PLS 4.0.

Data sources

This study is committed to examining how the dissemination of low-carbon knowledge through China’s environmental education influences the low-carbon behavior patterns of college students. The goal is to conduct a thorough analysis of the current environmental education system in China. To achieve this, we designed and implemented a questionnaire survey targeting college students across the country. The process involved forming a research team, training team members, conducting offline surveys, and expanding the scope through online platforms. The survey was conducted over seven months, from September 2023 to March 2024. We chose September as the starting point to include students of various age groups at the beginning of the academic year. March was selected as the end point because students typically have lighter academic loads at the start of the term, making them more likely to actively participate in the survey.

-

(1)

Establishing a Diverse Research Team with Broad Geographic Coverage

Given the vast territory of China and the widespread distribution of colleges and universities, a diverse research team was established to broadly collect samples and cover more regions in China. Specifically, the team included members from prestigious institutions in northern central cities like Tsinghua University and China University of Mining and Technology (Beijing); scholars from southeastern areas like Wenzhou University of Technology and southwestern areas like Guizhou University of Applied Technology for Science; and researchers from Guangzhou University. This ensured comprehensive coverage of China’s eastern, central, western, southern, northern, northeastern, northwestern, and southeastern regions. Prior to the launch of the survey, team members underwent extensive training to enhance their communication skills and ability to engage students in the survey. Additionally, we encouraged team members to recruit part-time questionnaire administrators in their respective cities to further expand the sample coverage and ensure representativeness.

-

(2)

Training to Enhance the Survey Collection Capabilities of Team Members

Before commencing the formal survey, to ensure that team members could collect as much relevant information and data as possible for this study, we conducted training sessions via online meetings. Firstly, we detailed the logic behind each survey item, explaining the type of information we expected to obtain. Secondly, tailored to the psychological characteristics of current college students, we provided training in communication skills, such as how to encourage students to patiently complete the survey and how to recruit additional part-time college students to assist in the research and ensure the accuracy of the collected information. Lastly, our team simulated future research scenarios through role-play, adopting the identities of both respondents and researchers, to anticipate and strategize solutions for potential obstacles and difficulties in data collection.

-

(3)

Conducting Offline Questionnaire Surveys in Eight Major University Cities in China

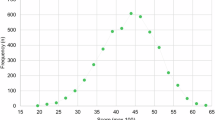

To maximize the efficiency of our data collection, it simply wasn’t feasible to survey every city in China. Instead, we opted for a more strategic method by focusing on areas with a dense population of universities. Consequently, we selected eight cities that are representative for our sampling surveys: Beijing (491 responses, 18.59%), Wuhan (329, 12.43%), Guangzhou (294, 11.11%), Nanjing (186, 7.02%), Shenyang (102, 3.85%), Shanghai (262, 9.90%), Xi’an (183, 6.92%), and Chengdu (160, 6.04%)—as illustrated in Fig. 3. These cities are home to a total of 557 colleges and universities and represent a significant portion of China’s higher education landscape, constituting 20.37% of such institutions, while also spanning across the main geographical regions of the country, ensuring a wide and varied sample. As shown in Fig. 3, the eight cities we surveyed (marked with blue dots) essentially cover all the major areas of China, which speaks to the strong representativeness of our collected data.

Our team members, along with part-time survey administrators, visited the cities and began by engaging directly with college students through face-to-face interviews. They collected experiences regarding the students’ environmental behaviors and carried out stratified sampling, considering the age and gender distribution of college students as provided by the National Bureau of Statistics. In this phase, we gathered a total of 732 samples.

-

(4)

Expanding the Research Scope through Online Questionnaire Platforms

To balance the representativeness of the sample with the cost-effectiveness of the survey, we crafted a hybrid sampling plan that integrates both probability and non-probability sampling techniques. Beyond the collection of data through traditional face-to-face methods, we broadened our research reach by utilizing online questionnaire platforms. We implemented a snowball sampling strategy and motivated participants to share the survey link, thereby improving the diversity and representativeness of our sample. The electronic questionnaire for this study can be accessed through the following URL: https://www.wjx.cn/vm/wFaQf2H.aspx# (access to August 11th, 2024). To improve the response rate and quality of the questionnaire, we introduced a red envelope incentive mechanism in the questionnaire design and clearly informed participants of the research purpose and confidentiality, ensuring their informed consent. Leveraging the characteristics of online questionnaires, we filtered out duplicate IP addresses and samples suspected of being hastily completed, ultimately obtaining 2646 valid samples, accounting for 86.9% of the total submitted questionnaires (Table 3).

Table 3 Sample statistical characteristics and balance test results.

Results and discussion

In this study, we utilized the PLS-SEM method to estimate the proposed structural equation model, aiming to uncover how various types of knowledge influence low-carbon behaviors. Prior to diving into the detailed model analysis, we conducted tests on the reliability and validity of the outer model to ensure the robustness and credibility of our findings. Subsequently, we will delve into the results of the inner model structure tests, which encompass single path hypotheses, mediation effect hypotheses, total effect hypotheses, and the influence of demographic characteristics. This comprehensive examination will provide a deeper insight into the interplay between knowledge and low-carbon behavior.

Outer model reliability and validity test

This study used PLS-SEM to estimate the structural equation model shown in Fig. 2. According to the PLS-SEM testing process (Hair, 2017), the outer model test is required first, which primarily refers to the relationship between the scale items and the constructs they are intended to reflect, measuring whether the scale items can adequately represent the constructs. The outer model test requires the examination of the following indicators: 1. Reliability, which mainly refers to the relationship between measurement indicators (scale items) and latent variables (also known as constructs); 2. Composite Reliability (CR); 3. Average Extraction Variance (AVE); and 4. Factor Loadings. Cronbach’s α is used to test the reliability of the measurement indicators, with values typically ranging between 0 and 1. An α coefficient below 0.6 is generally considered to indicate insufficient internal consistency; a value between 0.7 and 0.8 indicates adequate reliability, while a value between 0.8 and 0.9 indicates very good reliability (Agbo, 2010). Next, Composite Reliability (CR) measures the internal consistency of the latent variable’s measurement indicators, with higher CR values indicating greater internal consistency, and 0.7 is the acceptable threshold (Hair et al., 2020). Then, the Average Extraction Variance (AVE) is measured, which assesses the variance explained by the latent variable’s measurement indicators, also known as convergent validity; a higher value indicates better reliability and convergent validity, with an ideal standard value greater than 0.5, and 0.36 to 0.5 as the acceptable threshold (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Lastly, Factor Loadings are measured, which statistically represent the degree to which each item contributes to a latent variable, with higher values indicating better measurement effectiveness, and generally above 0.5 being the acceptable range (Monecke & Leisch, 2012). The test results, as shown in Table 4, indicate that the reliability of the outer model in this study is acceptable.

Secondly, discriminant validity needs to be measured, which refers to whether a latent variable is truly distinct from other constructs by empirical standards. The commonly used assessment method is the Fornell-Larcker criterion, which is based on whether the average extracted variance (AVE) of a latent variable is greater than the square of the correlation coefficients between that latent variable and other latent variables (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The intuitive understanding of the Fornell-Larcker criterion is that if a construct’s measurement indicators explain its own variance (AVE) to a greater extent than its association with other constructs (correlation coefficients), then these constructs can be considered distinctly different, i.e., they possess discriminant validity.

The advantage of this assessment method is that it provides a clear, quantifiable standard to judge the discriminant validity between constructs, helping to ensure that the constructs in the study are independent and discriminating. This is particularly important for multivariate analysis methods such as Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), which rely on clear and independent relationships between constructs.

This method is systematic and convenient, thus widely adopted (Wang et al., 2023). This study also employed this testing method, and the specific test results are shown in Table 5. The square root values of AVE on the diagonal are all greater than the other values in the box, indicating good discriminant validity.

Inner model structure test

In this paper, the inner model structure test process involves validating the interrelationships between the latent variables (constructs) as depicted in Fig. 2. This process also encompasses the evaluation of the hypotheses proposed in the section “Theoretical analysis and proposal of research hypotheses” of the article. The results of the test are detailed in Table 6, which is divided into four main sections, each corresponding to the four types of hypotheses presented in this paper:

-

(1)

Single Path Hypothesis Test: This section tests the hypotheses regarding the direct impact relationships between individual latent variables.

-

(2)

Mediation Effect Hypothesis: In this section, we assess the potential mediating effects between variables, that is, whether one variable influences the outcome by affecting another variable.

-

(3)

Total Effect Hypothesis: This section focuses on the total effects between latent variables, considering the sum of the direct and indirect impacts without the mediating variables.

-

(4)

The Role of Demographic Characteristics: The final section explores how demographic characteristics affect the relationships between variables in the model.

Each of these four types of tests corresponds to the respective hypotheses proposed in section “Theoretical analysis and proposal of research hypotheses”. The term “Hypothesis” here refers to the theoretical hypotheses previously presented in the article, while “Path” describes the specific pathways of interaction between variables. The “Standardized path coefficient” represents the quantification of the strength of the relationship between variables. The “t-values” that follow demonstrate the statistical results of the t-test, which aid in judging the credibility of the hypotheses. The use of asterisks (*) below the test results indicates the level of acceptance of the test outcomes, with more asterisks signifying stronger support. The “Is it supported” column directly indicates whether the inner model structure test results support the corresponding hypotheses. Through this structured presentation, we can clearly understand the validation of each hypothesis and its role and significance within the model.

-

(1)

Single Path Hypothesis Test

To maintain conciseness and clarity, this study presents the validation results of the single path hypothesis and the mediating effect hypothesis graphically (see Fig. 4). The data supported hypotheses H1a, H1c, H1d, H1f, H1g, and H1j, while H1b, H1e, and H1i were not confirmed. Specifically, the results for H1a and H1c showed that systemic knowledge and action knowledge impact subjects’ low-carbon intentions. Notably, systemic knowledge (βH1a = −0.101) negatively affected low-carbon intentions, a phenomenon known as “cognitive dissonance” in psychology and environmental behavior research. Cognitive dissonance, introduced by social psychologist Leon Festinger in 1957, describes the psychological discomfort and tension that arises when an individual holds conflicting cognition (knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors) (Festinger, 1962). In environmental behavior research, cognitive dissonance explains why individuals, despite having systematic environmental knowledge, may feel overwhelmed by information overload (Chen et al., 2023) and perceive their actions as ineffective (Xu et al., 2022). Information overload refers to the stress and anxiety caused by a large amount of environmental problem information, leading individuals to avoid information and reduce their willingness to act. Perceived ineffectiveness involves individuals feeling powerless to act, despite recognizing the seriousness of climate change, and thus being unwilling to participate in environmental activities. College students, who lack extensive social experience and resources, often feel insignificant and frustrated when facing environmental issues (Marvell & Child, 2023). Andersen (2024) found that college students feel confused and frustrated after recognizing the seriousness of climate change, often due to a lack of feasible solutions. This emotional experience may lead them to believe that their personal actions have a negligible impact on global climate change, reducing their willingness to engage in environmental behaviors (Andersen, 2024).

The negative impact can be understood through the following mechanisms: First, individuals may feel overwhelmed by a large amount of environmental problem information, leading to cognitive load and psychological discomfort. This stress may prompt them to adopt defensive mechanisms, such as avoiding information, to alleviate discomfort. Second, even if individuals recognize the seriousness of the problem, they may be unwilling to act because they feel their power is limited. This sense of insignificance may lead them to perceive ineffectiveness in their environmental responsibilities, believing that their personal actions cannot make a substantial change. This phenomenon, known as “cognitive dissonance,” was first proposed by Festinger (1962) and refers to the discomfort felt by individuals when they hold conflicting cognitions, leading them to change their behavior or attitudes to reduce discomfort.

To enhance college students’ willingness to engage in environmental behaviors, it is necessary to reduce their cognitive load through education and policy intervention, provide concrete action plans, enhance their sense of self-efficacy, and create a supportive environment that makes their actions meaningful and effective. Community participation and practical activities can help college students build confidence in their ability to make a positive impact, motivating them to take more environmental actions (Fig. 5).

H1b was not supported, indicating that systemic knowledge does not directly impact low-carbon capabilities. This suggests that changing low-carbon behavior involves multiple aspects, such as personal habits, social norms, economic conditions, and the availability of technology. Mere awareness of the problem’s seriousness (systemic knowledge) is insufficient to overcome these obstacles and improve low-carbon capabilities. For college students, economic conditions, available resources, and living environments may limit their ability to transform systemic knowledge into practical low-carbon actions. The average living expenses of college students in China do not exceed 1500 RMB (approximately 210 USD), and many students rely on student loans to live (Zhang, 2024). This directly leads to students being unable to afford energy-saving equipment or implement effective energy-saving measures due to economic constraints.

In contrast, action knowledge (βH1c = 0.231) positively impacts low-carbon intentions, indicating that understanding specific environmental behaviors and practices enhances low-carbon intentions. Action knowledge covers specific behaviors such as energy saving, waste reduction, and using public transportation, helping individuals feel capable of making a positive contribution to environmental issues. Additionally, action knowledge promotes the establishment of self-efficacy, the confidence in successfully performing a certain behavior, which further stimulates low-carbon intentions. College students, in the process of forming their self-identity and values, are particularly sensitive to behaviors that reflect personal values and social responsibility. For example, Alfirević et al. (2023) found that college students’ sense of personal value and social responsibility is significantly enhanced when participating in environmental protection activities. Li (2022) also noted that college students’ attitudes towards environmental protection behaviors are closely related to their values and self-identity, making them more inclined to adopt behaviors that reflect their personal beliefs and social responsibility. Action knowledge not only provides specific guidelines for environmental protection behaviors but also helps build self-efficacy, which is crucial for stimulating low-carbon intentions because it makes individuals believe their actions can bring about positive changes.

The results of H1d further confirm that action knowledge not only enhances low-carbon intentions but also significantly improves low-carbon capabilities. Action knowledge covers the specific skills, methods, and strategies needed to achieve environmental protection goals, directly impacting the improvement of college students’ low-carbon capabilities. However, the role of action knowledge in promoting low-carbon intentions (βH1c = 0.231) is greater than its role in enhancing low-carbon capabilities (βH1d = 0.069). This is because low-carbon intentions refer to an individual’s motivation and intention to take environmental actions. Action knowledge, by providing clear action plans, helps individuals overcome the obstacle of “not knowing how to act,” thereby enhancing their willingness to engage in environmental behaviors. This enhancement is often accompanied by positive emotional responses, such as hope, excitement, and increased self-efficacy, which are important psychological factors that motivate individuals to act.

In contrast, improving low-carbon capabilities involves applying knowledge, skills, and resources in practical operations. This includes understanding and mastering relevant knowledge and skills and investing time and energy to practice, adjust, and optimize behaviors. The improvement of low-carbon capabilities may be a gradual process that requires continuous practice and experience accumulation in daily life. Therefore, although action knowledge has a direct promoting effect on low-carbon capabilities, this process may be relatively slow and requires more time and sustained effort.

The positive results of H1f and the unsupported results of H1e indicate that effective knowledge positively impacts individuals’ low-carbon capabilities but not significantly their low-carbon intentions. This is because improving low-carbon capabilities depends on mastering specific skills and the conditions for executing low-carbon behaviors, while forming low-carbon intentions reflects an individual’s internal motivation and tendencies. Although effective knowledge can help individuals realize the benefits of specific environmental actions and improve their ability to perform these actions, this cognitive understanding does not always translate into a profound understanding of environmental values. Low-carbon intentions are influenced not only by cognitive factors but also by emotions, values, and social environment. Effective knowledge mainly focuses on the execution of actions and may not deeply touch the individual’s values and emotional level. Statistical data show that more than 95% of college students agree with a low-carbon lifestyle, but actual actions are relatively few, reflecting a “knowledge-behavior gap” (Xiang & Liu, 2024). Individuals may know that taking a certain environmental action is beneficial, but if they lack a deep emotional resonance with environmental issues or do not feel that these actions are closely related to their values and life goals, their low-carbon intentions may still not be high. For college students, who have relatively low economic and social status and face practical pressures such as employment and career development, this gap is particularly significant.

-

(2)

Hypothesis of Mediation Effect

In examining the mediation effects, hypotheses H2h and H2l were supported by empirical data, while the other hypotheses from H2a to H2k were not confirmed. This outcome has significant implications for understanding the psychological and behavioral mechanisms through which college students develop low-carbon behaviors.

Specifically, the supported hypotheses H2h and H2l indicate that action knowledge and efficacy knowledge can positively influence low-carbon expenditure behaviors by enhancing individuals’ low-carbon capabilities. For college students, this means that when they have mastered the specific methods to implement low-carbon behaviors (action knowledge) and believe these actions can effectively improve the environment (efficacy knowledge), they are more likely to make low-carbon choices in their daily lives, such as in shopping, transportation, and energy use. This is particularly pronounced among college students, who generally have a strong capacity for learning and accepting new knowledge. For instance, Wu et al. (2022) found that college students are more inclined to adopt environmental behaviors after understanding the specific methods of environmental actions, enabling them to quickly absorb and apply action knowledge. Moreover, their environmental awareness and desire to see tangible results encourage them to engage in low-carbon behaviors.

However, the unsupported results for hypotheses H2a to H2d reveal a practical issue: although systemic knowledge provides a comprehensive understanding of low-carbon lifestyles, it does not effectively promote the formation of low-carbon behaviors through low-carbon intentions and capabilities. This may be because systemic knowledge lacks specific action guidance or fails to fully stimulate college students’ low-carbon intentions and enhance their capabilities. College students may be more motivated by concrete action guides and direct environmental benefits rather than abstract concepts and ideas. For example, Shafiei & Maleksaeidi (2020) found that college students’ willingness to engage in environmental behaviors is stronger when they perceive the direct benefits of such actions. Additionally, Ridhosari & Rahman (2020) showed that college students’ understanding of green infrastructure and environmental policies on campus affects their willingness and behavior in participating in environmental activities. This suggests that to enhance college students’ low-carbon behaviors, it is necessary to provide more specific and easily implementable action plans and ensure they can see the positive impact of these behaviors on the environment.

The unsupported findings for hypotheses H2e through H2j further indicate that even though action knowledge and efficacy knowledge can enhance an individual’s low-carbon intentions, these intentions do not directly translate into actual low-carbon behaviors. This underscores that while low-carbon intentions are a key driver for behavior change, achieving such transformation requires the support of additional factors, such as the enhancement of low-carbon capabilities and favorable external environmental conditions. For college students, this may imply that they require more support and resources, as well as an encouraging campus and societal environment that promotes low-carbon behaviors, to convert their low-carbon intentions into tangible actions.

Finally, the unsupported results for hypotheses H2g and H2k demonstrate that despite action knowledge and efficacy knowledge being able to boost an individual’s low-carbon capabilities, this capability does not directly lead to an increase in low-carbon conservation behaviors. This may be because the implementation of low-carbon conservation behaviors is influenced by a variety of factors, including personal habits, social norms, economic incentives, and the availability of resources. For college students, they might already possess a certain level of low-carbon capabilities, but due to economic conditions, lifestyle habits, or a lack of sufficient incentives, these external factors could become barriers to adopting low-carbon conservation behaviors.

-

(3)

Hypothesis of Total Effect

In the validation process of the total effect hypothesis, we found that hypotheses H3c and H3f were supported by the data, while hypotheses H3a, H3b, H3d, and H3e were not confirmed. This finding is significant for understanding the mechanisms by which college students form low-carbon behaviors.

The support for hypothesis H3c indicates that action knowledge has a significant promoting effect on low-carbon conservation behaviors. For college students, action knowledge encompasses the specific skills and strategies they need to implement low-carbon behaviors, such as energy saving, waste reduction, and optimizing resource use. This type of knowledge is directly linked to the execution of behaviors and can effectively encourage them to adopt more low-carbon conservation behaviors in their daily lives. College students typically have strong learning abilities and a willingness to practice, enabling them to quickly absorb and apply action knowledge, thus achieving significant results in low-carbon conservation behaviors.

Similarly, the supported hypothesis H3f reveals the comprehensive promoting effect of efficacy knowledge on low-carbon expenditure behaviors. For the college student demographic, efficacy knowledge involves their firm belief in the effectiveness of low-carbon behaviors, that is, their belief that adopting low-carbon behaviors can positively impact the environment. This belief can stimulate their internal motivation, prompting them to be more willing to invest in low-carbon products and services. However, due to the relatively limited economic resources of college students, this belief may be more reflected in their low-carbon intentions rather than directly translated into actual low-carbon expenditure behaviors.

The unsupported hypotheses H3a and H3b suggest that although systemic knowledge provides a comprehensive understanding of low-carbon lifestyles, it does not directly promote low-carbon behaviors. This may be because systemic knowledge lacks specific action guidance and implementation strategies, and college students may prefer to guide their low-carbon behaviors through concrete action and efficacy knowledge rather than relying solely on systemic knowledge.

The unsupported result for hypothesis H3d indicates that while action knowledge has a positive impact on low-carbon conservation behaviors, its overall impact on low-carbon expenditure behaviors is not significant. This may be because low-carbon expenditure behaviors are subject to various factors, including economic conditions, market supply, and policy support. For college students, these external factors may limit their ability to convert action knowledge into low-carbon expenditure behaviors.

Finally, the unsupported result for hypothesis H3e shows that although efficacy knowledge can enhance individuals’ beliefs in the effectiveness of low-carbon consumption and promote low-carbon expenditure behaviors to some extent, it does not produce an overall promoting effect. This may be because individual expenditure behaviors are influenced by various factors, including personal financial conditions, consumption habits, and market environments. For college students, these factors may weaken the comprehensive impact of efficacy knowledge on low-carbon expenditure behaviors.

-

(4)

The Role of Demographic Characteristics

When examining the influence of demographic characteristics on low-carbon conservation and expenditure behaviors, the study revealed that gender and academic inclination significantly impact low-carbon conservation behaviors. Specifically, females tend to place more emphasis on low-carbon conservation behaviors compared to males. This may be attributed to females’ more frequent participation in saving and resource management activities in daily life, which aligns with their traditional roles in family settings. Additionally, females may exhibit higher sensitivity to environmental issues and climate change, especially when these issues directly affect health and quality of life. This heightened sensitivity may prompt them to adopt more low-carbon conservation measures. Furthermore, societal expectations and role modeling during the socialization process may encourage females to exhibit more environmentally friendly behaviors.

The influence of academic inclination is related to an individual’s educational background and professional knowledge. Students with a natural science inclination may have a deeper understanding of environmental science and sustainable development, thus recognizing the impact of human activities on the environment and the importance of adopting conservation measures. The discipline training in natural sciences may cultivate problem-solving and innovative thinking in students, inspiring them to actively seek and implement low-carbon conservation strategies in their daily lives.

Regarding the impact of the academic stage, as students progress in their studies, they may be exposed to more knowledge about environmental protection and sustainable development. The accumulation of this knowledge may enhance their awareness of long-term environmental issues and the long-term impact of personal behaviors. Additionally, as students grow older, they may gain more economic autonomy and consumption capacity, making them more willing to pay extra for low-carbon products and services, thus showing a positive effect on low-carbon expenditure behaviors.

Comprehensive discussion of research findings

This study provides a nuanced categorization of knowledge types and dimensions of low-carbon behaviors. It further integrates the “Knowledge—Attitude—Behavior” framework with the “Motivation—Capability—Opportunity” model, explicitly positioning low-carbon intention and capability as mediating variables, and deeply explores the mechanisms through which low-carbon knowledge influences low-carbon behaviors via these mediators. The main innovations of this study are summarized in Table 7.

In terms of research design:

-

(1)

Unlike previous studies that treated knowledge as a single entity (Liu et al., 2020), this study subdivides environmental knowledge into system knowledge, action knowledge, and efficacy knowledge, refining the impact mechanisms of different types of knowledge on low-carbon behaviors.

-

(2)

Unlike previous studies that generalized low-carbon behaviors (Raeisi et al., 2018), this study further distinguishes low-carbon behaviors into low-carbon conservation behaviors and low-carbon expenditure behaviors, clarifying behavioral differences under different psychological and economic motivations.

-

(3)

Unlike previous studies that only used low-carbon intention as a mediating variable (C. Li et al., 2023b), this study introduces low-carbon capability as an additional mediating variable, deepening the mechanism of how knowledge translates into behavior through capability and providing a more comprehensive explanation for the formation of low-carbon behaviors.

In terms of research conclusions:

-

(1)

System knowledge has a negative impact on low-carbon intention, challenging the common view in previous studies that knowledge only positively affects low-carbon behaviors (Liu et al., 2020). The study further discusses the “cognitive dissonance” individuals may experience when confronted with the severity of environmental issues, as well as the numbness to environmental problems due to information overload (perceived ineffectiveness). Unlike studies focusing on the positive role of knowledge (Anthonysamy et al., 2020; Ardoin & Bowers, 2020; Grilli & Curtis, 2021), this paper supplements existing research from a cognitive psychology perspective.

-

(2)

Low-carbon intention only significantly affects low-carbon conservation behaviors but not low-carbon expenditure behaviors, which is different from the common assumptions in previous studies (e.g., Hines, 1987) and reveals the limitations of low-carbon intention. In contrast, low-carbon capability significantly affects low-carbon expenditure behaviors but not low-carbon conservation behaviors. This finding addresses the insufficient explanatory power of low-carbon intention for overall low-carbon behaviors in previous studies (Mata et al., 2021), indicating that both low-carbon intention and capability are needed to promote the formation of low-carbon behaviors.

In summary, this study not only enriches the theoretical foundation of low-carbon behavior research but also provides new insights and empirical support for the formulation of environmental education strategies.

Conclusion and limitations

Conclusion

This study investigates how the dissemination of low-carbon knowledge influences the adoption of low-carbon behaviors among Chinese college students. By constructing a theoretical model and testing hypotheses related to the interplay between low-carbon knowledge, intention, capability, and behavior, the research employs Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to rigorously analyze the collected data. Given that environmental education has been integrated into China’s primary and secondary education curriculum since 2014, and current college students have been exposed to this education, this study aims to evaluate its long-term impact and effectiveness. The findings lead to several key conclusions:

Firstly, systemic knowledge, which involves understanding environmental systems and ecological processes, has been found to have a negative impact on low-carbon intentions. This counterintuitive effect can be attributed to cognitive dissonance, where individuals, despite recognizing the severity of climate change, may feel overwhelmed and anxious due to a sense of personal powerlessness or information overload, leading to a reluctance to engage in low-carbon behaviors.

Secondly, the research reveals that action knowledge and efficacy knowledge significantly and positively influence low-carbon intentions and capabilities. Action knowledge, by providing specific insights into environmental behaviors and practices, effectively enhances individuals’ intentions and capabilities to act. Efficacy knowledge, in turn, indirectly influences low-carbon expenditure behaviors by bolstering individuals’ low-carbon capabilities, indicating that different types of knowledge can impact behaviors through various psychological mechanisms.

Lastly, demographic characteristics, such as gender and academic inclination, significantly impact low-carbon conservation and expenditure behaviors. Female students and those with a natural science background are more inclined to adopt low-carbon conservation behaviors, while students at higher academic stages are more likely to engage in low-carbon expenditure behaviors.

These conclusions contribute to the theoretical frameworks of environmental psychology and behavioral science by shedding light on the cognitive dissonance that systemic knowledge may cause. The results highlight the positive roles of action knowledge and efficacy knowledge in promoting low-carbon behaviors, providing empirical support for the “Knowledge—Attitude—Behavior” model and underscoring the pathways through which different types of knowledge can influence behavior.

The implications for environmental education strategies are clear. Educators and policymakers should focus on strategies that reduce cognitive dissonance and enhance students’ willingness and capability to adopt low-carbon behaviors. Environmental education should emphasize practicality and teach students how to implement low-carbon behaviors in their daily lives. Additionally, demographic factors such as gender and academic inclination should be considered in the design and implementation of educational interventions to ensure they are effective and targeted.

The study’s contributions are notable:

-

(1)

It pioneers the categorization of knowledge types and dimensions of low-carbon behaviors, addressing the controversy over the impact of knowledge on behavior by introducing a framework that recognizes the functional differences among various types of knowledge.

-

(2)

It expands the “Knowledge—Attitude—Behavior” model by incorporating the “Motivation—Capability—Opportunity” model, introducing a new mediating variable, “low-carbon capability,” which is based on low-carbon intention. This dual mediation model offers a more comprehensive understanding of how different types of low-carbon knowledge affect behaviors.

-

(3)

The findings challenge the conventional view of knowledge’s uniformly positive role by showing that systemic knowledge can negatively influence low-carbon intentions, providing a new perspective for developing environmental education strategies and low-carbon promotion policies.

Recommendations

Based on the key findings of this study, action knowledge and efficacy knowledge are more effective in promoting low-carbon environmental behaviors compared to systemic knowledge. However, the dissemination of systemic knowledge can sometimes lead to cognitive dissonance among students, which contradicts the primary objective of environmental education. To effectively enhance students’ low-carbon intentions and capabilities, it is crucial to integrate all three types of knowledge into a cohesive educational system. Currently, environmental education in China places excessive emphasis on systemic knowledge while neglecting action and efficacy knowledge. To address this issue, the government should take a leading role by focusing on action and efficacy knowledge, rather than solely on environmental value education. It should create conducive conditions for teaching these types of knowledge, such as establishing special funds to support schools in conducting practical teaching and low-carbon living experience activities. This would enable students to learn low-carbon behaviors through hands-on operations. Additionally, the government should promote the establishment of community environmental activity platforms and organize diverse environmental-themed activities to raise public awareness and participation in environmental protection. Strengthening cooperation with families, media, and other social sectors to build a comprehensive environmental education network and foster a social atmosphere conducive to low-carbon behaviors is also essential. In addition to cultivating students’ values through systemic knowledge, schools should incorporate action and efficacy knowledge into their education systems. Interactive teaching methods, such as case studies and role-playing, can enhance students’ understanding and interest in low-carbon behaviors. Schools should also establish resource recycling systems, like setting up recycling stations and encouraging the trade of second-hand items, to promote the rational use of resources. Furthermore, schools can collaborate with enterprises to offer internships and project-based learning, allowing students to experience and practice low-carbon behaviors in real-world work settings. Families and society should actively participate in environmental education to jointly foster environmental awareness and behavioral habits among young people. Families can set examples for children through daily behaviors and participate in community environmental activities, such as “Car-Free Day” and “Energy Saving Week,” to enhance children’s practical experience in environmental protection. On a broader societal level, public awareness of low-carbon living can be raised through media campaigns and public lectures. Policy guidance and incentive mechanisms, such as low-carbon behavior reward systems, can encourage public engagement in low-carbon lifestyle practices. Through these comprehensive measures, the effective promotion of low-carbon environmental behaviors among Chinese college students can be achieved, contributing to the realization of sustainable development goals.

Limitations and future work

While this study has made progress in analyzing the relationship between low-carbon knowledge and behavior among Chinese college students, it is not without limitations. First, the study’s focus on college students to assess the long-term impact of China’s environmental education is constrained by a sample size of 2646, primarily sourced from major university cities. This limits the representativeness of the sample, suggesting that future research should broaden to include a wider range of students and regions.

Second, the cross-sectional design of the study makes it challenging to establish causal relationships. Future research would benefit from adopting longitudinal methods to track changes in low-carbon knowledge and behaviors over time, offering a more precise understanding of their interplay.

Additionally, reliance on self-reported questionnaires may introduce social desirability bias. Future studies should incorporate experimental designs and objective behavioral data, such as energy consumption records, to enhance the accuracy of measurements.

Regarding policy recommendations, this study offers several suggestions without empirical validation. Future work should pilot these recommendations on a small scale, evaluate their effectiveness, and refine them based on feedback.

Moreover, the study predominantly examines individual knowledge, intentions, and capabilities, with limited consideration of external environmental factors. Future research should investigate how policies, market incentives, and social norms influence low-carbon behaviors and interact with individual psychological factors.

In summary, while this study provides valuable insights into low-carbon education and behavior, further exploration is needed. Refining research methods and deepening analysis will enhance our understanding of the mechanisms driving low-carbon behavior, ultimately providing stronger scientific support for environmental education and policy development.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are publicly available on GitHub at the following link: https://github.com/newyork1000/shali-Wang. Readers are welcome to access and download the data for further research purposes.

References

Agbo AA (2010) Cronbach’s alpha: review of limitations and associated recommendations. J Psychol Afr 20(2):233–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2010.10820371

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Alfirević N, Arslanagić-Kalajdžić M, Lep Ž (2023) The role of higher education and civic involvement in converting young adults’ social responsibility to prosocial behavior. Sci Rep. 13(1):2559. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29562-4

Andersen IV (2024) Seeking consensus on confusing and contentious issues: young Norwegians’ experiences of environmental debates. Environ Commun 18(4):435–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2023.2299358

Anthonysamy L, Koo A, Hew S (2020) Self-regulated learning strategies and non-academic outcomes in higher education blended learning environments: a one decade review. Educ Inf Technol 25(5):3677–3704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10134-2

Ardoin NM, Bowers AW (2020) Early childhood environmental education: a systematic review of the research literature. Educ Res Rev 31:100353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100353

Bassul Areias G, Martins Nobre IA, Silva Passos ML (2023, 2023-1-1) Assessment of learning Mediated by Digital Technologies in the Context of Environmental Education: Teacher Training through a MOOC Course. Paper presented at the 2023 International Symposium on Computers in Education (SIIE). https://doi.org/10.1109/SIIE59826.2023.10423715

Bamberg S, Möser G (2007) Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: a new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J Environ Psychol 27(1):14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.12.002

Bentler D, Kadi G, Maier GW (2023) Increasing pro-environmental behavior in the home and work contexts through cognitive dissonance and autonomy. Front Psychol 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1199363

Cao Q, Kang W, Xu S, Sajid MJ, Cao M (2019) Estimation and decomposition analysis of carbon emissions from the entire production cycle for Chinese household consumption. J Environ Manag 247:525–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.06.044

Chen T, Li X, Duan Y (2023) The effects of cognitive dissonance and self-efficacy on short video discontinuous usage intention. Inf Technol People. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-08-2022-0634

Conway TM, Ordóñez C, Roman LA, Yuan A, Pearsall H, Heckert M, Dickinson S, Rosan C (2021) Resident knowledge of and engagement with green infrastructure in Toronto and Philadelphia. Environ Manag 68(4):566–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01515-5

Dalvi-Esfahani M, Alaedini Z, Nilashi M, Samad S, Asadi S, Mohammadi M (2020) Students’ green information technology behavior: Beliefs and personality traits. J Clean Prod 257:120406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120406

Duerden MD, Witt PA (2010) The impact of direct and indirect experiences on the development of environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. J Environ Psychol 30(4):379–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.03.007

Fernandez J, Mithraratne K, Alipour M, Handsfield G, Besier T, Zhang J (2020) Towards rapid prediction of personalised muscle mechanics: integration with diffusion tensor imaging. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng: Imaging Vis 8(5):492–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681163.2018.1519850

Ferreira M, Martinsone B, Talić S (2020) Promoting sustainable social emotional learning at school through relationship-centered learning environment, teaching methods and formative assessment. J Teach Educ Sustain 22(1):21–36. https://doi.org/10.2478/jtes-2020-0003

Festinger L (1962) A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Mark Res 18(3):382. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

Frick J, Kaiser FG, Wilson M (2004) Environmental knowledge and conservation behavior: exploring prevalence and structure in a representative sample. Personal Individ Differ 37(8):1597–1613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.02.015

Grilli G, Curtis J (2021) Encouraging pro-environmental behaviours: a review of methods and approaches. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 135:110039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110039

Guan X, Ma W, Zhang J, Feng X (2021) Understanding the extent to which farmers are capable of mitigating climate change: a carbon capability perspective. J Clean Prod 325:129351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129351

Hair JF (2017) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE, Los Angeles

Hair JF, Howard MC, Nitzl C (2020) Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J Bus Res 109:101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2011) PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J Mark Theory Pract 19(2):139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hines JM (1987) Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behavior: a meta-analysis. J Environ Educ 18(2):1