Abstract

The memorialisation of conflict heritage is a complex process due to its traumatic origin. One iconic example is the Iron Belt, a mythical line of fortifications defending Bilbao during the Spanish Civil War, which has been repurposed as a political tool to convey diverse interpretations of the conflict. This article explores the dynamics of its memorialisation and examines how the same archaeological record can generate contrasting war narratives. To address these challenges, the study employs an innovative digital humanities framework to document, analyse, and interpret four sections of the Iron Belt in which archaeological structures remain preserved. The framework establishes a geospatial database model, analysed using Geographic Information Systems and data visualisation techniques. This methodology facilitates the cross-referencing of interconnected heritage variables –such as conservation, dissemination activities, and the institutions responsible for them–, that have not previously been quantitatively assessed. Results indicate divergent heritage management approaches, shaped by different political, economic, and social contexts at the local level. This suggests that the pastness of the Iron Belt is actively constructed in the present through “past presencing” policies. Additionally, the study highlights the critical role of local entities and associations, which often act as key agents in initiating the memorialisation of complex heritage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The memory of 20th-century wars remains highly significant in contemporary societies due to the profound trauma associated with these events. The Great War left inter-war Europe with deep-seated collective memories, leading to a proliferation of memorials, literature, and films. World War II and the Holocaust remembrance reinforced this trend, marking the character of societies and states from 1945 to the present day (Macdonald, 2013). The heritage of these conflicts plays a key role in defining historical narratives (Abazi & Doja, 2018).

The complex interaction between heritage and politics is central to the field of critical heritage studies (González-Ruibal et al., 2018; Harrison, 2013b; Waterton & Smith, 2010), which focuses on the present-day uses of cultural heritage (Harrison, 2018; Westmont, 2022). Societies are extremely diverse and so are their attitudes towards heritage (critical, subaltern, ignorant). There is currently intense debate around this relationship and, specifically, on how to communicate this heritage to the community (González-Ruibal et al., 2018; Harrison, 2018; Westmont, 2022, p. 2). Some theoretical paradigms, such as community archaeology, question whether these projects satisfy an internal desire of individuals and groups to explore and affirm group identity or whether, on the contrary, they are complicit in a political agenda that pushes a particular archaeological record and, thus, a particular idea of community (Moshenska & Dhanjal, 2022, p. 10).

War heritage is part of this complex heritage since it acts as a repository, where the same materiality supports different memories. In fact, Rodney Harrison defines remembrance as “an active process of cultivation and pruning, not a process of complete archiving and total recall” (Harrison, 2013a, p. 579). This dynamic is different depending on the background of each society. In the Basque Country, narratives of the Spanish Civil War (SCW, 1936–1939) diverge from the official discourse promoted by Spain’s central institutions. While the 2007 Historical Memory Law initially provided a common framework, Basque nationalism –particularly the influence of ETA, which was active from the time of late Francoism until the early 21st century– has shaped local memory. Decades of politically motivated violence left a lasting impact, with ETA self-identifying as heirs to the Basque soldiers of the SCW (Fernández Soldevilla, 2014). Since the dissolution of ETA, archaeological and heritage projects on the SCW have expanded, supported by a growing political consensus.

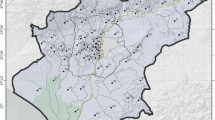

The largest piece of heritage of the SCW in the Basque Country is the Iron Belt (Cinturón de Hierro), a line of Republican fortifications that defended Bilbao from the Francoist army in 1937. A symbol of Basque resistance against Francoism, it was granted legal protection in 2019. The designated heritage area forms an 80-kilometre perimeter around Bilbao, spanning 25 towns where remnants of the fortifications still exist. Studying the Iron Belt in its entirety presents significant challenges due to its vast extent, varied locations (ranging from urban areas to remote mountainous terrain) and differing levels of memorialisation (with some sections undergoing extensive restoration and public engagement, while others remain largely untouched).

The size and complexity of the Iron Belt also raises the question of whether the memorialisation of this fortified line is being affected by the idea of the crisis of the accumulation of the past (Harrison, 2013a). This concept asserts that society can become overwhelmed by memory because of the “exponential growth of heritage objects, places and practices in the contemporary world”, potentially losing the effectiveness and value of heritage.

This work studies the divergent materialities and narratives generated by the SCW in the Basque Country by a comparative study of 3 sectors of the Iron Belt. Specifically, we explore what political, geographical, and historical factors explain the memorialisation of this iconic conflict site. We approach it through a multidisciplinary perspective by implementing the combined use of traditional archaeological methods (field surveys), and Digital Humanities analytic tools: a geospatial database, Geographical Information Systems (GIS) and data visualisation. This methodology enables the cross-referencing of various interconnected variables within the field of heritage studies that, until now, could not be compared with a quantitative approach (such as conservation, dissemination activities and the entities that run them). Geographical variables are analysed using Geographic Information Systems (GIS), while non-geographical variables are examined through data visualisation in R Studio.

The present never reproduces the past as it was, but rather its idea of “pastness” (Holtorf, 2013; Macdonald, 2013). Our framework aims to understand the memory of these historical events as an integrated approach including material culture, historical landscapes, and remembrance activities. In particular, we want to explore whether Iron Belt heritage and its different memorialisations have a premeditated geographical dimension and, if so, on the basis of what factors and how it has been constructed (whether from the past or from the present). There are authors who argue that the traumatic events of the past are the basis for the construction of the European present in the form of “past presencing” strategies as defined by Sharon Macdonald (Macdonald, 2012). Macdonald describes this “past presencing” as the dynamic ways in which the past is actively brought into the present through practices, performances, and representations. However, other scholars, such as Cornelius Holtorf, argue that “pastness” is constructed from the present through the selection of certain historical episodes (Holtorf, 2013). Holtorf’s approach, while complementing Macdonald’s view, focuses more on the cultural perceptions that make something feel connected to the past. In this context, we pose the following question: do the locations of these memorialisations align with the areas of greatest combat (Macdonald’s model - the past is what marks the dynamics of memorialisation in the present) or with those that are currently more sensitive and have more means at their disposal, e.g. greater economic capital (the construction of “pastness” from the present day, as Cornelius Holtorf argues)? The research also aims to discern which narrative(s) have been promoted and which aspects of the battle have been highlighted, as well as the agents involved in this process.

Iron Belt: myth and reality

With the outbreak of the SCW the northern loyalist territories (Asturias, Cantabria, and the Basque region of Biscay) were isolated from the rest of the Republic as they were surrounded by Francoist-controlled zones. In response, the Basque government, beyond relying on Republican support, established its own army and constructed Bilbao’s Defensive Belt (Fig. 1), later known as the Iron Belt. Inspired by World War I fortifications (Redondo Rodelas, 2005, p. 44), this defensive line aimed to protect the capital, key resources, and infrastructure, enabling Bilbao to withstand a long-term siege.

The Iron Belt during the war

From its inception in October 1936, Bilbao’s Defensive Belt faced significant logistical and political issues. In addition to material shortages and the lack of manpower resulting from the mobilisation of the civilian population, two of the leading engineers left the project: Pablo Murga was arrested and sentenced to death for spying, while Alejandro Goicoechea defected to the Francoist side (Líbano Silvente et al., 2018, p. 247). Goicoechea provided crucial intelligence information on the fortifications, including a weakly defended 2.5-kilometre sector at Mount Gaztelumendi (Larrabetzu). The Republican government was aware that the Iron Belt was not strong enough to repel a Francoist offensive (Redondo Rodelas, 2005, pp. 44–45). The design was simply too ambitious for the newly created Basque army as there was not enough manpower and weapons to build and garrison such a long perimeter (Martínez Bande, 1971, pp. 157–158).

The Francoist army assaulted Bilbao’s Defensive Belt between 11 and 12 June 1937. It was a decisive military action: the breakthrough precipitated a fall chain reaction leading to the fall of Bilbao and the Biscay region.

Mythifications and memorialisation

Although originally known as “Bilbao’s Defensive Belt,” the Francoist regime officially rebranded it as the “Iron Belt” to reflect the Basque Country’s industrial heritage. (Beldarrain Olalde, 2012, p. 312). The conquest was already used as a symbol of victory during the war, even though this battlefield landscape was completely desolate due to the proximity of the events in time. In 1938, the Gaztelumendi area was incorporated into the Rutas de la Guerra en España (War Routes in Spain) tourist itinerary (Figs. 2, 3), alongside the bombed town of Gernika. In subsequent years, local institutions aligned with official policies by erecting monuments to Francoist soldiers in symbolic locations, selecting the summit of Gaztelumendi for this purpose. The narrative developed during these years emphasised the strength of the Iron Belt to highlight the audacity and bravery of the Francoist armies that were able to conquer it.

The victory narrative ended shortly after Francoism, as the official discourses promoted by the dictatorship began to be questioned throughout Spain (Del Arco Blanco, 2022). A variety of authors revisited the conflict, leading to the development of new memory policies and the advancement of scientific research. In the Basque Country, the proclamation of Spain’s Historical Memory Law (2007) and the ending of ETA’s terrorist violence in 2011 facilitated public debates on the SCW (Eser, 2019; Santamarina Otaola, 2022, p. 38). Once political consensus was reached, the Basque Country chose to adopt the model of Catalonia, a region at the forefront of memory policies in Spain. Thus, in 2015, the Basque equivalent of Catalonia’s public Institute of Memory (Memorial Democràtic) was established: the Gogora Institute of Memory, Coexistence, and Human Rights.

In the absence of public policies in this area until the 2010s, volunteers, enthusiasts, and local administrations took the lead in promoting awareness of these issues. These initiatives included the cataloguing of Iron Belt archaeological remains by the Sancho de Beurko association and the creation of small interpretation centres on the war with material culture recovered through the practice of looting. Over the past decade, the process of memorialisation has focused on interpreting the SCW through the lens of Basque nationalism. This represents the institutionalisation of the perspective on the war that the region’s predominant political party, the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV), has been promoting as part of its ideological agenda for decades (Herrero Acosta & Ayán Vila, 2016, pp. 111–117).

The Iron Belt is one of the core symbolic elements that supports this narrative as in 2019 it became the first war site to receive heritage status in the Basque Country (Santamarina Otaola, 2022, p. 10). The decree established a protective buffer within the multiple defence lines, prioritising larger heritage elements –such as pillboxes, machine-gun nests, and gun positions– across three zones based on factors like structural density and historical significance. While trenches and other non-monumental features are not explicitly listed, their protection is ensured within the designated buffer. The Iron Belt has now become a symbolic space of resignification by a variety of agents beyond archaeological research and official cataloguing. Initiatives such as walking tours and Living History stand out among diverse activities mostly organised by local associations (Herrero Acosta & Ayán Vila, 2016; Santamarina Otaola, 2022, p. 57).

Sectors under study

The analysis focuses on three sectors as seen in Fig. 4a) section I – Punta Lucero Hill (Zierbena); b) section IV – Mount Gaztelumendi and Larrabetzu village; and c) sector V – Mendibe-Areneburu Hill (Berango/Sopela) and the Santa Marina Crags (Urduliz). This choice was based on the need to integrate different realities: historically relevant areas, sectors including the most monumental heritage elements, and villages with diverse sociocultural dynamics. All the selected research areas received the highest degree of protection (zone 1 - special protection areas).

Section I: Punta Lucero Hill (Zierbena)

-

Context

The area of Punta Lucero is a geostrategic key point covering the access to Bilbao and its harbour. An old artillery battery built during the Third Carlist War (1872–1876) was refitted at the beginning of the SCW and three lines of fortifications strengthened the defensive positions (Beldarrain Olalde, 2012, pp. 77–78; Martínez Bande, 1971, pp. 46–47). The sector did not see major actions during the conflict but its predominant position overlooking the coast was used during Francoism to deploy a new coastal battery and garrison quarters which were in use until 1982.

-

Protection

Decree 195/2018 originally included 9 structures in the Punta Lucero sector (ZIEF01 to ZIEF09). There was some previous debate on which conflict-related structures should be preserved in this area. In 2018, excavation tasks were carried out in the nearby Moreo area: as some structures (ZIEF10, ZIEF11) had been so severely affected by urbanisation works during the 2000s, they were excluded from protection (Escribano-Ruiz et al., 2018; Santamarina Otaola, 2022, p. 336).

-

Memorialisation

The lack of political commitment to the rehabilitation of these structures has not been straightforward and has given rise to much debate. Some local associations and political parties are calling for its refurbishment (Ll., 2014), but so far without success.

Section IV: Mount Gaztelumendi and Larrabetzu village (Larrabetzu)

-

Context

The north-west area of the village of Larrabetzu, specifically between the mountains of Urrusti (Gamiz-Fika) and Gaztelumendi (Larrabetzu), was the section where Franco’s troops breached the Iron Belt. This area featured a single line of trenches (which was excessively straight), thin barbed wire fences and only three machine gun nests (Martínez Bande, 1971, p. 163). The heritage elements preserved in the area are scattered, so the research focused on two different subsectors: Mount Gaztelumendi and the village of Larrabetzu. This approach was chosen to encompass not only the memorialisation of the battlefield itself, but also the dynamics of urban contexts near the Iron Belt.

-

Protection

Larrabetzu is the village with the largest number of structures protected by the decree (65). The standard protection buffer of 5 metres across the Iron Belt was extended to 30 metres in this sector due to the significant concentration of wartime structures and because it was a municipality where there was “direct war confrontation” (Decreto 195/2018, de 26 de Diciembre, Por El Que Se Califica Como Bien Cultural, Con La Categoría de Conjunto Monumental, El Cinturón de Hierro y Defensas de Bilbao (Álava y Bizkaia), 2019, p. 40).

-

Memorialisation

In recent years, we have seen growing interest in memorialising this iconic sector of the Iron Belt. These actions especially take place in the village, as its urban space is a complex landscape of memory. The urban area of Larrabetzu includes memorial spaces (the Larrabetzu Memory Space, the Historical Memory Square, or the mural that reproduces Picasso’s Guernica) alongside legally protected war structures in some buildings (LARF27-LARF33).

Section V: Mendibe-Areneburu Hill (Berango/Sopela) and the Santa Marina Crags (Urduliz)

-

Context

The fifth section of the Iron Belt was the strongest one as it was built as a 3-line deep defence position. A first line of contact was established in Barrika, the main line of resistance in Urduliz and the reserve line along the Sopela-Berango-Getxo axis. The geostrategic importance of this sector lies in its proximity of the harbour and other key elements, such as the Berango weapons factory, the Plentzia-Getxo road or the railway line to Bilbao.

-

Protection

The varied functionality of the three lines has led to the protection of several structures. They are clustered in two sectors: a) the Mendibe-Areneburu Hill includes 10 elements linked to the Iron Belt within the towns of Berango (BERF01) and Sopela (SOPF01-SOPF04, SOPF06, SOPF21-24), and b) the Santa Marina Crags (Urduliz) have 9 protected structures (URDF17, URDF19-URDF27) and two new to be included in the near future: URDFXX1 and URDFXX2 (Líbano Silvente et al., 2018, pp. 256–261).

-

Memorialisation

Section V has undergone significant memorialisation efforts, most notably with the inauguration of the pioneering Memorial Museum of the Iron Belt in Berango in 2012. Urduliz has also actively promoted this heritage through various initiatives, ranging from archaeological research (Líbano Silvente et al., 2018) and rehabilitation of war structures to the construction of a memorial park with several commemorative statues.

Materials and methods

The Iron Belt is a significant component of the heritage narratives generated by the SCW which often overlap with current political debates. This line of defence continues to generate strong interest both in terms of local archaeology and social engagement (Escribano-Ruiz et al., 2018; Líbano Silvente et al., 2018; Salazar Cañarte et al., 2018), but its public impact has seldom been analysed from the perspective of heritage studies.

The amount and diversity of Iron Belt heritage elements requires an approach with the capacity to integrate geographical, archaeological, and textual sources. In the absence of parallels in terms of methodology, we have deployed a novel framework based on digital humanities to combine data from different disciplines. The use of computational approaches to study conflict heritage is still rare yet gradually increasing (Capps Tunwell et al., 2016); among these innovative studies, there are a few works focusing on the SCW (Prades Artigas, 2012; Rubio-Campillo et al., 2021). The framework presented here aligns with the methods of these previous initiatives by creating a geospatial database of Iron Belt elements.

A geospatial database of conflict heritage

The official catalogue of protected Iron Belt structures has not been published in an open format suitable for analysis and, for this reason, it was necessary to collate different information sources. The first step was to create a geospatial database of Iron Belt heritage elements (Fig. 5). This database was implemented in SQL, and incorporates data from diverse sources, including records from the protection law (available in the Ondare Basque heritage dataset) and the results of archaeological fieldwork, which are discussed further below.

Beyond the classificatory use of databases in archaeology and heritage (Gattiglia, 2018), the database we propose takes a further step by integrating the territorial agents involved in its management and conservation, along with the cultural activities that have emerged around the Iron Belt. This approach adds significant value, enabling the study of various interconnected aspects in the process of memorialising such important war heritage in the Basque Country: identifying the actors behind these initiatives, examining the dissemination activities being carried out, and assessing the actual state of conservation of these spaces in relation to the applicable protection legislation.

The geospatial database is structured around 6 tables (Structures, Heritage Cataloguing, Activities, Museums, Routes and Entities), which are connected by identifiers (e.g., ‘id_equip’ is present in the Structures and Heritage Cataloguing tables to link a structure with its protection record). Each table also contains variables tailored to the specificities of the case study. For example, the Activities table has all the dissemination actions carried out around this heritage, the institution responsible and their frequency. This database is accessible on the GitHub platform: https://github.com/tania-gonzalez-cantera/iron_belt_legacy_ddhh.

Fieldwork

Fieldwork was essential to complete the data on the selected areas. During July and August 2022, archaeological surveys were carried out: they included Iron Belt structures (both listed and non-listed in the decree), memorialisation landmarks, monuments, and heritage presentation elements (i.e., signals, museums).

A database record was created for each item (e.g., structure), that included attributes such as geographic coordinates, architectural details, and conservation status. Surveys covered most areas within the studied sectors, except Gaztelumendi, where access was restricted due to private ownership and ongoing livestock or timber activities. Despite these constraints, the survey documented a representative sample of 125 structures and two museums.

Geospatial analysis

The use of GIS in heritage studies primarily focuses on managerial tasks, such as creating spatiotemporal infrastructures for large-scale archaeological data (McKeague et al., 2012) and identifying risks to cultural heritage from human activities (Cecilia-Conesa et al., 2022). However, its application in exploring the spatial dimension of cultural heritage is less common than in management and digitisation tasks (Ferreira-Lopes, 2018). This limited use of GIS in heritage research is surprising, given its potential to handle the vast amounts of data generated by heritage institutions, including official records, aerial photographs, archaeological reports, and other valuable sources. The starting point for this comprehensive analysis was the geolocation of heritage elements and their data processing using GIS software to examine variables such as preservation state, typology, and ownership.

Data visualisation

Conflict-related heritage is often georeferenced, yet some factors influencing memorialisation are more challenging to explore using GIS. For instance, spatial analysis can be useful for identifying structural patterns, such as town limits or proximity to urban centres, which may impact the conservation state of defensive elements. However, GIS is less effective at combining multiple variables, for example the year of protection or the element type, in a single analysis. To overcome this limitation, the analysis integrates GIS with data visualisation techniques.

Data visualisation refers to an exploratory set of statistical tools designed to identify complex patterns within large datasets. Its use in archaeological and heritage research (Manovich, 2015) has been relatively limited, with similar applications for the SCW also scarce, despite its considerable potential (Carrero-Pazos, 2023, pp. 89–91). In this study, data visualisation techniques were employed to uncover potential dynamics and relationships within non-spatial data, presenting the complex patterns that emerged from the analysis.

Results

An overview of Iron Belt heritage

Figure 6a shows a summary of the structures recorded in the database according to conservation and location, while divided by typology to facilitate comparison. The five towns share a general trend in which concrete elements (which usually are the most typologically complex structures) are particularly present. These structures are usually adapted either to their surroundings or to specific functions. The strong visibility of these large structures has turned them into relevant landscape elements such as the fortifications of the Pikene farmhouse in Larrabetzu or the compound casemates of Urduliz.

Machine-gun nests exhibit significant variability in conservation. According to the classification developed for this research, the condition of these defensive positions in Zierbena and Larrabetzu is generally rated as “acceptable”, whereas in Urduliz and Berango, they are prioritised and in “very good” condition. The conservation and signage of excavated elements such as trenches and shelters in mine galleries are proportionally lower, with variation depending on the town. Regarding ownership, the general trend shows that structures located on public land tend to have a higher conservation status than those on private land (Fig. 6b). However, it is noteworthy that in areas with significant agricultural activity, like Larrabetzu, privately owned structures are often better conserved due to ongoing land maintenance linked to these activities.

The level of visibility of Iron Belt structures seems more linked to their location and accessibility than their type or complexity. In general, structures that are difficult to access, regardless of land ownership, are neither restored nor made accessible to the public. For example, in Larrabetzu, the machine-gun nests, and the fortification located on the hill of Basaguren (LARF24, LARF55 and LARF26), which are near the town centre, have been added into the local memory route. However, those structures are currently in such a degraded state that they are not signposted, making it difficult for the public to visit them.

Punta Lucero

Punta Lucero is a complex and unique landscape, where war remains of different chronologies and typologies coexist. The type of the war structures depends on the chronology, the location, and the role they played in the defence system in different periods. Structures built during the war as part of the Iron Belt (mainly machine-gun nests and slick slit trenches) are located on the western slope (Fig. 7a). They are rudimentary, and their complexity is very different from the defensive positions found in the rest of the sectors. However, both in the material remains of Carlist origin and in structures erected during the post-war period, the coastal batteries, and their associated structures (from quarters to checkpoints) stand out.

Punta Lucero is the only sector in which monumentality is not the primary criterion for safeguarding heritage. Instead, protection is guided by the inclusion of these structures in the original planning of the fortified line. Consequently, only the structures specifically built as part of the Iron Belt, located on the western slope, have been protected. In contrast, the elements located on the hilltop, some of which were repurposed in the Iron Belt defence system, have been excluded from any heritage protection despite their exceptional state of conservation.

The inaction of public institutions has led to the progressive degradation of this unique environment (Fig. 7b). Conservation of the Iron Belt structures protected in the 2019 decree is worse than of war structures on the summit, which receive a constant flow of visitors. Unlike the rest of the municipalities, Zierbena does not yet have any memory itinerary and has not joined this network founded by the Basque government. This is paradoxical given the increase in the number of hikers in Punta Lucero. The tourism offices in the area, such as those run by the Biscay Provincial Council or Bilbao’s City Council, have publicised the popularity of this route and even advertise Punta Lucero. The tourist information highlights the natural environment while ignoring its conflict heritage elements.

Larrabetzu

The musealisation of the Iron Belt in Larrabetzu has not been a homogeneous process, mainly because this heritage is scattered throughout a large area. Local rehabilitation and reconditioning policies focused on the town centre due to its proximity to the Historical Memory Square, the Larrabetzu Memory Space, and the reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica.

Urban Iron Belt structures in Larrabetzu differ from the rest of the case studies due their uniqueness (Fig. 8a), ranging from concrete embrasure walls (LARF27 and LARF30) to doors with concrete lintels (LARF28). Their integration into the urban landscape (houses and factories) facilitated their restoration and incorporation within the memorialisation dynamics, resulting in their excellent conservation. However, Iron Belt elements on the hill located next to the town centre have undergone the opposite dynamic: they are the worst-preserved in this area (Fig. 8c), as they are located on private rural properties.

a Map identifying the types of Iron Belt structures located within the town centre of Larrabetzu; b map identifying the types of Iron Belt structures situated on Mount Gaztelumendi; c map indicating the conservation status of structures in the village of Larrabetzu; d map illustrating the conservation status of structures located on Mount Gaztelumendi.

Gaztelumendi shows less restoration and memorialisation despite being the site of the Iron Belt assault (Fig. 8b). A major factor is that structures are mostly within private enclosed land. During our fieldwork, we had the chance to talk to landowners in the area who were willing to show and tell the story of the remains. One relevant aspect emerged from their testimony: to date, they have been responsible for restoring the structures. With the gradual loss of agricultural and livestock activity, due to a lack of generational replacement, the structures are deteriorating and becoming hidden by the undergrowth (Fig. 8d). Despite the lack of visibility, the fieldwork verified that heritage protection was fulfilled in Gaztelumendi as most structures are well preserved, particularly the concrete elements.

Berango/Sopela

Berango is the municipality with the longest public tradition of reconditioning the Iron Belt, despite being a secondary defensive line. The conservation of the Iron Belt in the Berango/Sopela area follows the same pattern as in the other case studies: the most monumental structures, such as machine-gun nests or the SOPF22-SOPF24 complex fortifications (Fig. 9a), which were included in the protection decree, are better preserved (Fig. 9b). In contrast, the elements legislatively protected due to their proximity to special protection areas are poorly conserved. Our fieldwork documented four sections of trenches not recorded in the official catalogue, which remain invisible to visitors. This situation embodies the underlying premise of the decree: prioritising the more monumental war structures, typically built for combat, while minimising the visibility of less spectacular heritage related to the soldiers’ daily routines.

Local institutions integrate Iron Belt structures into mountain routes and educational activities. Their commitment to promoting these conflict spaces results in a constant flow of visitors, especially due to their proximity to the town centre and the frequent activities organised by the Memorial Museum. Public interest in this heritage is also visible in the presence of signposts marking Iron Belt elements and the regular care of the structures. During the fieldwork, we witnessed regular cleaning and preservation activities of Iron Belt heritage carried out by a forestry brigade.

Urduliz

The epicentre of the intense memorialisation in this sector is the Memorial Park that links the two crags of Santa Marina, along which Iron Belt remains are distributed (Fig. 10a). Signposts and memorial items are located on the first crag of Santa Marina despite the scarcity of Iron Belt elements. The second crag includes a cluster of monumental elements unique within the entire Iron Belt, such as the URDF25 compound casemate to deploy three machine-guns (Líbano Silvente et al., 2018, p. 247). The fieldwork documented several sections of communication trenches. The path that runs along this set of structures, which are communicated visually, follows the shape of the trench where the topography allows it. This route makes it easier for the visitor to understand the functionality of these structures, as it does not show isolated structures, but the connection between them all. The use of the war landscape is a memorial strategy that, despite being possible in other sectors, has only been adopted in Urduliz.

This sector shows a strong pattern linking public land ownership with the level of conservation and, therefore, accessibility. Iron Belt structures located on public land are part of the Urduliz memory itinerary and are well preserved and easily accessible, as public interest leads to routine maintenance (Fig. 10b). This is no coincidence if we bear in mind that Iron Belt remains are a tourism asset for Urduliz, complementing the outdoor climbing in Santa Marina.

Active memorialisation: events, routes, and associations

The protection decree left the management of the protected Iron Belt heritage in the hands of town councils, which have developed different preservation and dissemination strategies. The only common strategy is concerning hiking routes, partly because it does not entail continuous, excessive expenditure. Hiking is a deeply rooted tradition in Basque society, and, for this reason, the four studied areas include the Iron Belt landscape within several routes.

The situation is very different in terms of public institutions organising activities, exhibitions, memorials or tributes, as each municipality has a different position when it comes to dissemination. Figure 11a shows that Larrabetzu, which covers a sector of the battlefield, is the municipality that organises the greatest number of research and educational activities on the heritage and history of the Iron Belt. However, several of these are either one-off (such as archaeological excavations) or once-yearly activities (such as tributes). This lack of continuity in educational activities in Larrabetzu means that it is the Memorial Museum of the Iron Belt in Berango that attracts most visitors and has established itself as the centre of reference in this field. Despite offering fewer activities, the Berango museum runs these activities more frequently (especially school visits and guided tours) and, therefore, receives a continuous flow of visitors throughout the year.

The lack of exhibition centres focusing on the Iron Belt is, from the outset, a handicap when it comes to organising activities related to this heritage in the rest of the municipalities. In Urduliz, to date, the town council has made a commitment to promote Iron Belt heritage research and dissemination activities (e.g. excavations and conferences). However, this council has expressed its intention to build a centre focusing on the Iron Belt (Goitia, 2020), together with an adventure centre to complement the climbing option in Santa Marina.

Sopela and Zierbena are at the bottom of the list in terms of the number of activities; in Sopela the main reason may be that guided tours organised by the nearby Berango Memorial Museum extend to Sopela, while, in Zierbena, there has been no interest on organising heritage events since 2015 (Fig. 11b). Furthermore, the activities organised in Punta Lucero (Zierbena), mainly guided tours and historical reenactments, were sporadic and always run by local associations.

Nowadays activities related to the Iron Belt spearheaded by local institutions (such as town councils and museums) and associations, or through collaboration between these entities. This partnership has developed progressively in recent years. In terms of activity types, guided tours are favoured by public organisations due to their broad appeal to various audiences, including schools and families. In contrast, associations tend to organise more unique events, such as historical reenactments (e.g. the 2015 event organised by the Sancho de Beurko and Enigma associations in Zierbena) or mountaineering races (e.g. the annual race hosted by the Karraderan association in Larrabetzu).

Discussion

Uses of the Iron Belt: from marginalisation to tourism

Conflict landscapes and monuments are a key historical source for researching the memories that have prevailed about the war and its transformation over time. In the post-war period, the remains of the Iron Belt were “marginalised”, although this does not equate to complete abandonment as these structures were often reused over the decades. Gaztelumendi is an excellent example of this repurposing as the Franco regime converted the landscape of the breakthrough into a powerful political symbol by including war structures in tourism routes and erecting a cross-shaped monument to the fallen Francoist soldiers.

Another form of “marginalisation” is the continued use of some of the war structures in Zierbena. Elements of Carlist origin, reused within the Iron Belt, were incorporated into the military complex that was established at the top of Punta Lucero during the Francoist period. In contrast to the other case studies, the continuity of the military use of these structures, has positively contributed to their preservation. Paradoxically, structures built specifically to form part of the Punta Lucero Iron Belt have not received the same status and have gradually been degraded.

Iron Belt heritage remained widely ignored at a collective level until the 2000s, when the growing demands of local associations began to take hold in society. The first educational initiative involving Iron Belt heritage took place in Punta Lucero in 2007. The Aldapa cultural group organised a 23 km mountain walk along Zierbena, including the remains of Punta Lucero from the Carlist, SCW and post-war periods. The dynamic mountain route – guided tours also took place in Larrabetzu years later. Since 2017, the number of activities around the Iron Belt, particularly school visits, has significantly grown thanks to the creation and consolidation of Gogora Institute.

Today, the tourism and educational activities on offer related to the Iron Belt vary greatly between municipalities, reflecting differing societal attitudes towards this contested heritage. In some towns, such as Berango, highly successful educational activities are run, exemplified by the guided tours organised by the Memorial Museum of the Iron Belt. In contrast, other areas, like Zierbena, offer minimal or no such activities. Beyond the political, economic, and associative factors that underpin these disparities (which are examined in the following section), the local population’s attitude towards this heritage is a key aspect to consider. The lack of interest, ignorance or even rejection of this heritage may be due a combination of factors: a) the general tendency to forget or disregard the war promoted by the institutions for decades (Encarnación, 2017), b) social fatigue due to the crisis of accumulation of vestiges of the past as noted by Harrison (Harrison, 2013a), and c) the community (or part of it) possibly non-identification with the established official narrative (Moshenska & Dhanjal, 2022). This unbalanced state of the memorialisation of the Iron Belt could be reversed through greater collaboration with the local community, more effectively shaping their vision of this heritage. This would generate a more critical identity towards this contested past and the tensions that derive from it.

Divergent narratives

Interest in Iron Belt elements culminated with the Iron Belt heritage protection decree in 2019. Monumentality seems to be the main criterion for both the protection and rehabilitation of war heritage, while machine-gun emplacements or air raid shelters are protected on an individual basis, trenches or spaces outside the protection buffer remain vulnerable. This criterion is also supported by the lower costs involved in the conservation of concrete and stone structures to the detriment of excavated elements in the ground or made of masonry.

In the process of cataloguing and rehabilitation, town councils and associations played a significant decision-making role. This indicated that municipalities would have considerable autonomy in managing this heritage. As a result, a clear differentiation has emerged in the rehabilitation and public management of these structures. For instance, Zierbena consistently neglects this heritage, despite these remains being protected by the highest legal status within the Basque legal system. In contrast, villages such as Berango, Sopela, and Urduliz view Iron Belt remains as cultural and tourism assets, using them to boost local economies. The result is that nowadays these municipalities have a continuous flow of visitors, given their proximity to the town centres and thanks to other complementary activities (e.g., the Urduliz climbing circuit). These differences in the state and pace of the memorialisation of the Iron Belt are profoundly influenced by the combination of three present-day factors. This is an indicator that the narrative of the past or the “pastness” (Holtorf, 2013) of the Iron Belt is constructed on the basis of different present-day factors (politics, economics, the role of associations) and, in contrast, is not grounded in the geography of the battlefield.

The first factor is economic: both the municipalities on the Right Bank (Berango, Sopela and Urduliz) and those in inner region of Biscay (Larrabetzu) are financially well-off areas, with a greater capacity to invest in this type of heritage. This buoyant economy means that these municipalities sometimes claim a strong link to Iron Belt heritage despite not having experienced any armed confrontation during the war. The case of Berango is paradigmatic: home to Memorial Museum and with only one structure belonging to the Iron Belt protected (BERF01), it currently leads the way in terms of memorial actions linked to this heritage, even more so than the breakthrough sector in Larrabetzu. The decontextualization of this heritage has not been a problem when it comes to structuring their message, plagued by constant allusions to the fall of Gaztelumendi and the resistance of the Basque army. This is an example of how the political agenda clearly shapes the war narrative and the sense of community surrounding this particular archaeological record (Moshenska & Dhanjal, 2022). This set of actions has been possible thanks to the support of a powerful service-driven local economy as compared to the other sectors.

The opposite dynamic can also be observed in the analysis: an already consolidated tourism area that deliberately ignores the controversial contested heritage. Iron Belt structures in Punta Lucero go unnoticed in an area increasingly visited by hikers attracted by routes on which the main landmarks are barracks and the guns of the Francoist battery. The omission of this heritage (Ibarra Álvarez, 2024) may be related to the fact that the local economy is fully focused on the port rather than tourism: its intensive industrial activity makes Zierbena one of the Biscayan municipalities with the highest income. This fact contrasts sharply with its immediate surroundings as the mining zone on the Left Bank region where Zierbena is located has been in economic and industrial decline for decades (Plan Estratégico Comarcal de Ezkerraldea/Meatzaldea 2030, 2020, pp. 14–15).

The second factor that deeply influences the process of memorialisation of the Iron Belt is the political tradition of each municipality. Basque nationalism, whether right-wing or left-wing, has historically been a dominant force in the political landscape of the Right Bank and the inner region of Biscay. For example, since the return of democracy, all municipalities in Berango, Sopela, Urduliz, and Larrabetzu have had nationalist mayors. In contrast, the region where the town of Zierbena is located has a working-class tradition, and the nationalist discourse only gained traction at the beginning of the 2000s (López Romo, 2017).

Lastly, the role of the associative sector has also been key in the way this heritage has been memorialised. Before the “boom” in Basque memory, it was the associations that undertook actions to remember and reassess both the battle and the soldiers who took part in it (Herrero Acosta & Ayán Vila, 2016; Santamarina Otaola, 2022). In the municipalities of both the inner and the Right Bank regions is where there was the greatest associative pressure to recover the heritage of the Iron Belt. This trend continues and is still visible today: while in Larrabetzu (inner area), Berango, Sopela and Urduliz (Right Bank) memorialisation is progressing, the lack of popular pressure and the demobilisation of associations in Zierbena (Left Bank) is a symptom of the serious state of the Iron Belt heritage in Punta Lucero. The lack of interest in war heritage in Punta Lucero could also reflect the crisis of accumulation of the past, as proposed by Harrison, with the presence of numerous war remains from different periods potentially overwhelming the local community.

When political efforts eventually focused on protecting the Iron Belt, the entities that had been advocating for its preservation for years, and even decades, were included in the process. Although this incorporation has taken place in the different heritage institutions, mainly in the Memorial Museum of the Iron Belt (Berango) and the Larrabetzu Memory Space (Larrabetzu), the result is very different.

Myths and symbols play an important role in the mobilisation and creation of identities and this can be seen in the different approaches to memory chosen by the museums driving the memorialisation of the Iron Belt. In Berango, the museum is seen as a cabinet of curiosities. Its permanent exhibition displays artifacts that are private donations by the Sancho de Beurko association. The narrative highlights and mythologises the Iron Belt and the gudaris who defended it, leaving not only other groups in the background but also contributing to the creation of the “neogudarism” (Herrero Acosta & Ayán Vila, 2016). In contrast, the Larrabetzu Memory Space is the paradigm of current approaches to the memory of the SCW. The centre was conceptualised as a “memory centre”, rather than a traditional museum, and for this reason, it does not feature a permanent exhibition. It also covers the entire 20th century and does not focus the whole narrative exclusively on the Iron Belt, but also on the role of women during the war, the ideologies of Republican troops beyond the Basque Army, and the persecution of the Basque language during Franco’s dictatorship.

Although institutions today seek both to support and establish permanent links with associations, these actions sometimes pose the following problems: a) these centres do not always reflect the demands of associations; and b) museums can even promote the legitimisation of possible heritage crimes. One example of the first case is that the memory of traditionally forgotten and silenced groups in Larrabetzu is confined to the exhibition hall and, thus, it fails to integrate within the daily lives of citizens. While the Larrabetzu centre is the only institution giving these groups a voice, they remain absent from its activities, monuments, and public tributes. On the second phenomenon is reflected in the recent controversy surrounding the sculpture Agurra (2023); this piece commemorates the tenth anniversary of the opening of the museum. According to its director, Agurra was made using “bronze rescued from the (Iron Belt) battlefield thanks to the work of Euskal Prospekzio Taldea” (an amateur metal detectorist group) (Miñambres Amézaga, 2023). The looting of Iron Belt archaeological remains was not illegal before the 2019 decree. However, the use of this material to create a commemorative sculpture and its publicisation as a benchmark of good community practices may be counterproductive to the preservation of SCW heritage.

Conclusion

Since its construction, the Iron Belt has always been surrounded by different interpretations and memories. Public interest in this war heritage has grown considerably over the last ten years, culminating with the approval of a heritage protection decree.

We have explored the materialities and memories of this war structure by developing an open-access database. This database not only incorporates its physical attributes but also the agents managing its conservation, and the cultural activities linked to the Iron Belt. This approach enables an analysis of the various interconnected factors in the memorialisation process.

Municipalities play an important decision-making role when it comes to the rehabilitation and dissemination of Iron Belt heritage. The result has been a clear differentiation in the memorialisation of the Iron Belt in the four case studies analysed (Berango/Sopela, Larrabetzu, Urduliz, Zierbena). This indicates that the “pastness” of the Iron Belt is constructed from the present-day (Holtorf, 2013); the main underlying causes, apart from the internal characteristics of each village, are a combination of economic, political and associative factors. Although the legislation is the same, differences in management are enormous: a case of serious failure to comply with the law in terms of conservation and maintenance has been documented (Zierbena). At the other extreme, there are town councils that consider Iron Belt heritage to be a potential economic and tourism asset (Berango, Urduliz).

“Past presencing” policies (Macdonald, 2012) have also been detected: where there is an interest in promoting these structures and the memory of the war, these aspects are usually combined with the canonical war myths of Basque nationalism (e.g. the gudaris’ resistance). Therefore, the narrative of the Iron Belt incorporates various elements associated with Basque nationalism to shape the image of the structure while fostering a new identity element for the community (Moshenska & Dhanjal, 2022). The incorporation of more diverse groups and perspectives into these memories is a slow process, which has so far only been documented in exhibition rooms and not in the public space.

The memorialisation of Iron Belt is a living process that was spearheaded by local associations. After years of campaigning, institutions have eventually echoed their claims and incorporated these associations in the organisation of activities and routes, collaborating on a regular basis.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are accessible on the GitHub platform: https://github.com/tania-gonzalez-cantera/iron_belt_legacy_ddhh.

References

Abazi E, Doja A (2018) Time and narrative: Temporality, memory, and instant history of Balkan wars. Time Soc 27(2):239–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X16678249

Beldarrain Olalde, P (2012). Historia crítica de la guerra en Euskadi (1936-37) (1. ed). Intxorta 1937 Kultur Elkartea

Capps Tunwell D, Passmore DG, Harrison S (2016) Second World War bomb craters and the archaeology of Allied air attacks in the forests of the Normandie-Maine National Park, NW France. J Field Archaeol 41(3):312–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2016.1184930

Carrero-Pazos, M (2023). Arqueología computacional del territorio. Métodos y técnicas para estudiar decisiones humanas en paisajes pretéritos. Archaeopress Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.32028/9781803276328

Cecilia-Conesa F, Orengo HA, Lobo A, Petrie CA (2022) An Algorithm to Detect Endangered Cultural Heritage by Agricultural Expansion in Drylands at a Global Scale. Remote Sens 15(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15010053

Decreto 195/2018, de 26 de Diciembre, Por El Que Se Califica Como Bien Cultural, Con La Categoría de Conjunto Monumental, El Cinturón de Hierro y Defensas de Bilbao (Álava y Bizkaia), Pub. L. No. 195/2018, 55 (2019). https://www.legegunea.euskadi.eus/decreto/decreto-1952018-26-diciembre-que-se-califica-como-bien-cultural-categoria-conjunto-monumental-cinturon-hierro-y-defensas-bilbao-alava-y-bizkaia/webleg00-contfich/es/

Del Arco Blanco, MÁ (2022). Cruces de memoria y olvido: Los monumentos a los caídos de la Guerra Civil española (1936-2021) (Primera edición). Crítica

Encarnación, OG (2017). Peculiar but not unique: Spain’s politics of forgetting. Aportes. Revista de Historia Contemporánea, 32(94), Article 94. https://www.revistaaportes.com/index.php/aportes/article/view/265

Escribano-Ruiz S, Santamarina-Otaola J, Herrero Acosta X, Pozo C, Martín Echebarria G (2018) Cinturón de Hierro en Punta Lucero (Zierbena). Arkeoikuska: Investigación arqueológica 2018:360–368

Eser P (2019) Narrativas del después: El “boom de la memoria” y las imaginaciones culturales del pasado violento en el escenario del pos-conflicto vasco. Olivar 19(30):1–15. https://doi.org/10.24215/18524478e059

Fernández Soldevilla, G (2014). ‘Gudaris’: El imaginario bélico de ETA y su opción por la violencia. David contra Goliat: guerra y asimetría en la Edad Contemporánea, 2014, ISBN 978-84-617-0550-4, págs. 303–323. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5037914

Ferreira-Lopes, P (2018). Achieving the state of research pertaining to GIS applications for cultural heritage by a systematic literature review. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLII–4, 169–175. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLII-4-169-2018

Gattiglia, G (2018). Databases in Archaeology. In S. L. López Varela (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of Archaeological Sciences (1st ed., pp. 1–4). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119188230.saseas0147

Goitia, JA (2020, May 20). Urduliz creará un parque de aventuras y un centro de interpretación junto al Cinturón de Hierro. El Correo. https://www.elcorreo.com/bizkaia/margen-derecha/urduliz-creara-parque-20200520184944-nt.html

González-Ruibal A, Alonso González P, Criado-Boado F (2018) Against reactionary populism: Towards a new public archaeology. Antiquity 92(362):507–515

Harrison R (2013a) Forgetting to remember, remembering to forget: Late modern heritage practices, sustainability and the ‘crisis’ of accumulation of the past. Int J Herit Stud 19(6):579–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2012.678371

Harrison, R (2013b). Heritage: Critical approaches. Routledge

Harrison R (2018) Critical heritage studies beyond epistemic popularism. Antiquity 92(365):e9

Herrero Acosta, X, & Ayán Vila, X (2016). De las trincheras al museo: Sobre el reciente proceso de patrimonialización de la Guerra Civil española en Euskadi. In I. Arrieta Urtizberea (Ed.), Lugares de Memoria Traumática: Representaciones museográficas de conflictos políticos y armados (pp. 99–122). Universidad del País Vasco

Holtorf C (2013) On Pastness: A Reconsideration of Materiality in Archaeological Object Authenticity. Anthropological Q 86(2):427–443

Ibarra Álvarez JL (2024) El papel de los arqueólogos y la Administración en la pérdida de patrimonio arqueológico: Una reflexión desde el caso de la provincia de Bizkaia (País Vasco, España). Nailos: Estudios Interdisciplinares de Arqueología 10:177–211

Líbano Silvente I, Salazar Cañarte S, Miñambres A, Vega López S, Zuazo Gibelondo K, Olabarrieta I, Trebolazabala A, Baizan J (2018) Seguimiento arqueológico en el cinturón de hierro de Bilbao. Terminos de ‘Loba’ (Gamiz-Fika) y ‘Santa Marina’ (Urduliz). Kobie Paleoantropol ía 36:245–263

Ll., S (2014, February 4). Reclaman la recuperación de la batería de Punta Lucero por su «importancia histórica». El Correo. https://www.elcorreo.com/vizcaya/v/20140204/margen-izquierda/reclaman-recuperacion-bateria-punta-20140204.html

López Romo R (2017) Terrorismo y nacionalización en Euskadi: El caso de la margen izquierda. Sancho el Sabio: Rev de Cult e investigación vasca 40:93–122

Macdonald, S (2012). Presencing Europe’s Pasts. In A Companion to the Anthropology of Europe (pp. 231–252). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118257203.ch14

Macdonald, S (2013). Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203553336

Manovich, L (2015). Data Science and Digital Art History. International Journal for Digital Art History, No 1. https://doi.org/10.11588/DAH.2015.1.21631

Martínez Bande, JM (1971). Vizcaya. San Martín

McKeague P, Corns A, Shaw R (2012) Developing a spatial data infrastructure for archaeological and built heritage. Int J Spat Data Infrastruct Res 7:38–65

Miñambres Amézaga, A (2023, February 25). Inauguración escultura Agurra (II). Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/museocinturondehierro/posts/pfbid0Z5Q9Rsg9RcpPYAu9S2sppqt2ZeM2nxuvcLXnYqRhydqWEf75Ys4628F57FTZ5zBLl

Moshenska, G, & Dhanjal, S (2022). Community Archaeology. Oxbow Books

Plan Estratégico Comarcal de Ezkerraldea/Meatzaldea 2030, Pub. L. No. PEC 2030, 64 (2020). https://gardentasuna.bizkaia.eus/documents/1261696/1397467/PEC+Ezkerraldea-Meatzaldea_cas.pdf/fc7378dd-ee10-e623-962b-f1889260247f?t=1634222879454

Prades Artigas, ML (2012). Sistema de información digital sobre las brigadas internacionales: Brigadistas, fuentes documentales y bases de datos (SIDBRINT) (1a. ed). Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha

Redondo Rodelas, J (2005). Franco rompe el ‘cinturón de hierro’: (Junio 1937). Unidad Editorial

Rubio-Campillo X, Feliu Torruella M, González Cantera T (2021) Datos, patrones y narrativas: Nuevas perspectivas sobre la Guerra Civil y la represión franquista a partir de la visualización de datos abiertos. Ebre 38: Rev Internacional de La Guerra Civ, 1936-1939 10:147–167. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/hysd7

Salazar Cañarte S, Líbano Silvente I, Vega López S (2018) Peñas de Santa Marina. Elementos URDF19 a URDF25 (Urduliz). Arkeoikuska: Investigación arqueológica 2018:356–358

Santamarina Otaola, J (2022). Euzkadi, ko lur-ganian: Arqueología del paisaje de la guerra civil en el País Vasco (1936-1950)

Waterton E, Smith L (2010) The recognition and misrecognition of community heritage. Int J Herit Stud 16(1–2):4–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441671

Westmont, VC (Ed.). (2022). Critical public archaeology: Confronting social challenges in the 21st century. Berghahn Books

Acknowledgements

TGC received the support of a fellowship from “la Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434). The fellowship code is LCF/BQ/DR21/11880004. XRC is funded by the Ramón y Cajal programme RYC2018-024050-I (Fondo Social Europeo – Agencia Estatal de Investigación). This research is part of MAELSTROM PID2023-147060NB-I00 (Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.G.C. led the fieldwork and data collection, and also conducted the data analysis and revision of the manuscript. X.R.C. designed and created the database. Both authors drafted the manuscript and performed the data visualisation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

González-Cantera, T., Rubio-Campillo, X. Battlefield memories: the legacy of Bilbao’s Iron Belt (Spanish Civil War) through digital humanities. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 709 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04987-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04987-6