Abstract

In travel decision-making, searching for the optimal travel paradigm is crucial, with risk perception playing a pivotal role. Despite its significance, a comprehensive understanding of risk perception from various sources within the travel population and its implications for choosing the best travel mode remains limited in existing literature. This paper offers a twofold contribution to the field to address this gap. Firstly, it presents an innovative framework for identifying and quantifying risk perceptions based on travel notes employing text mining. This framework effectively captures measures of risk perception at both the public and individual levels for specific destinations. Secondly, it statistically explores the relationship between travel paradigms and the proposed risk perceptions. Using Xinjiang province as a case study, empirical analysis reveals several key findings: (1) Individual travel profiles are associated with various factors that significantly influence risk perceptions, with factors such as travel expenditure and duration exerting the greatest impact, this coincides with the common perception; (2) Other factors, including traveling in non-autumn seasons, traveling with friends, going by cruising, cycling, self-driving, staying at three-star hotels on the northern and central area of Xinjiang, and following linear and circular routes, substantially reduce tourism risk perception; and (3) Discernible differences in travel plans between males and females emerge when their risk perceptions are low. Incorporating risk perception into travel planning provides valuable insights for destination tourism risk management and local economic promotion and holds significant implications for enabling tourists to form rational risk assessments and adopt comfortable travel styles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Travel has progressively evolved into a pivotal recreational pursuit within individuals’ daily lives. Presently, with the emergence of novel technologies and the overwhelming abundance of extensive data, travelers are faced with the onerous task of expending significant amounts of time and energy to devise travel itineraries and make sound decisions about their desired destinations through social media (Wang et al., 2019; Zeng & Gerritsen, 2014; Wu et al., 2018). Consequently, determining the optimal and efficient traveling paradigm that ensures comfort and rationality has emerged as a pressing problem.

Numerous travel recommendation systems have been developed, utilizing advanced technologies to suggest destinations based on travelers’ behaviors and preferences. For example, the development and application of post-recommendation filters can enhance the accuracy of hotel guest rating predictions (Veloso et al., 2019). Also, with the latest advancements in processing big online data, consumer-generated information can be automatically analyzed by artificial intelligence. As an aspect of smart tourism, some studies applied sentiment analysis to examine tourists’ online reviews, revealing their perceptions of services across different categories, particularly the reasons for their dissatisfaction with transportation services (Kim et al., 2017). However, merely a limited number of studies have addressed the subjective uncertainties and concerns (risk perception) associated with individual tourist’s travel decisions.

Risk perception is a person’s subjective assessment of potential risks, influenced by various psychological and emotional factors (Siegrist & Árvai, 2020). While much of the research on tourism risk perception has focused on objective risks such as safety or health concerns, few studies have addressed the subjective uncertainties or emotional factors that influence individual travel decisions. The challenge in incorporating risk perception into travel paradigms lies in two key areas: how to measure risk perception accurately (Wilson et al., 2019) and how to connect it to individual travel paradigms. Firstly, current methods for measuring tourism-related risks, such as psychometric scales or surveys, tend to focus on generalized risk factors, often overlooking the nuanced, individual differences in risk perception (Wolff et al., 2019). Furthermore, most studies have relied on one-dimensional models, which fail to capture the complexity of how various types of risks (e.g., physical, financial, emotional) interact within an individual’s decision-making process. While textual data from social media, reviews, and online discussions offer a potential solution, these have mostly been used to assess objective risk types or other risk evaluations (Zhu et al., 2022; Li et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2019; Wei et al.,2023), with limited attention to individual subjective perceptions.

Simultaneously, another research gap currently exists in understanding the relationship between travel paradigms and individual risk perception. Scholars specializing in travel behavior analysis have notably underutilized statistical techniques for the systematic evaluation of the complex interplay between them. Thus, future research endeavors must prioritize quantitative modeling, particularly regression analysis, to investigate the nuanced relationship between travel paradigms and risk perception with a heightened level of empirical rigor and sophistication. Therefore, developing a comprehensive method that captures the multidimensional nature of tourism risk perception, ranging from public to individual perspectives, is crucial to gaining insight into the intricate relationships between risk perception and travel paradigms.

Our study addresses these gaps by proposing a novel methodology to quantify risk perception, using textual data from online platforms. By doing so, we aim to provide a more comprehensive measure of tourism risk perception that accounts for both public and personal dimensions, moving beyond the one-dimensional approaches of previous research. This approach enables a clearer understanding of how individuals assess risk and how these perceptions influence travel decisions.

The main objectives of this paper are:

-

To develop a methodology for constructing risk perception metrics from textual data at both public and individual levels. Specifically, we explore how individual risk perceptions can be quantified and how they reflect a traveler’s heterogeneity in evaluating different types of risks.

-

To investigate the relationship between individual risk perceptions and actual travel paradigms. We aim to determine how risk perceptions influence travel decisions such as travel season and mode of transport.

-

To design rational travel recommendations that help minimize perceived risks while ensuring comfort and satisfaction. We aim to propose travel suggestions tailored to individuals with high or low risk perceptions, based on their specific travel profiles.

We apply this methodology to the context of travel paradigm recommendations in Xinjiang Province, China, and find several notable patterns: (1) Travel duration and expenditure are key factors influencing perceived risk. Shorter trips with higher expenditure tend to be associated with lower perceived risk. (2) The autumn season is perceived as the riskiest for travel, influencing travelers’ preferences. (3) Travelers with lower risk perceptions prefer more engaging and autonomous modes of transport, such as cycling, self-driving, and cruising, while avoiding traditional public transport. (4) Social factors, such as traveling with friends, are also important in mitigating perceived risks. (5) Gender differences significantly affect travel choices, with variations in preferred seasons, travel companions, and transportation modes.

Literature review

Research on tourism’s risk perceptions

In tourism, Perceived Risk Theory (Lepp & Gibson, 2003) has been extensively applied to understand how individuals evaluate risks before making travel decisions. This theory posits that individuals assess risks through objective threats (e.g., safety concerns, political instability) and subjective feelings (e.g., anxiety, prior experiences). For instance, earlier research has demonstrated that perceived risks influence destination selection (Sönmez & Graefe, 1998) and significantly impact the travel experience. Scholars have further delved into various dimensions of risk perception, employing psychometric models (Yang, 2024) and more complex socio-psychological frameworks (Siegrist & Árvai, 2020). These studies underscore that risk perception is a multifaceted concept intertwined with emotional states, such as uncertainty aversion, fear, and worry (Yang & Nair, 2014). From another angle, researchers have proposed that risk perception can serve as a quantitative proxy to evaluate safety and security in tourism (Cui et al., 2016; Williams & Baláž, 2013). A variety of methodologies have been utilized to measure risk perception. Traditional methods include surveys and questionnaires, while textual data mining from online reviews and social media platforms (Zhu et al., 2022) has emerged as a novel approach to capturing risk. Despite these advancements, most existing studies fail to integrate subjective risk assessments with objective risk metrics, limiting their ability to address individual differences.

Additionally, tools explicitly designed to measure personalized risk perceptions—vital for understanding individual travel preferences—remain underdeveloped. Existing theories and methodologies illustrate the complexity of risk perception in tourism, which encompasses both cognitive evaluations of external risks and emotional reactions to uncertainty. Addressing these intertwined dimensions is crucial for designing travel recommendations that account for the rational and emotional aspects of traveler decision-making.

Research on travel paradigm selection

The concept of travel paradigms encompasses the range of strategies and preferences travelers adopt when planning and experiencing their journeys. This includes decisions regarding destination choice, transportation modes, and itinerary planning. Various proposals have been put forth regarding travel paradigms. With the advent of cutting-edge technologies, there are more ways to give suggestions to tourists based on their travel patterns (Buhalis & Law, 2008; Hunecke et al., 2001; Le-Klaehn & Hall, 2015), including (1) considering travel personality categories to classify users and providing more accurate recommendations without the need for complex diagnostic questions (Gretzel et al., 2004); (2) predicting the tailored travel destinations based on tourists’ travel backgrounds and histories (Sun et al., 2018; Sohrabi et al., 2020; Lv & Wang, 2020); and (3) incorporating user interests, visit durations and visit sequence in the recommendation task to suggest personalized itineraries (Shen et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2020). However, in the context of interest-based recommendation systems, an important aspect that significantly impacts people’s feelings and overall travel experience—risk—tends to be disregarded. Psychological studies indicate that social and emotional concerns are integral to travelers’ pre-trip and post-trip evaluations (Xie et al., 2020). Scholars like Ritchie and Jiang (2019) emphasize that greater attention should be given to risk factors, as they can overshadow enjoyment and satisfaction during trips. Incorporating risk considerations into travel paradigms would not only enhance their practical utility but also provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding travel behavior.

Research on risk perceptions as a determinant of traveling decisions and destination choice

Therefore, understanding the relationship between risk perception and travel decisions is vital for improving the efficacy of travel recommendation systems (Chi & Qu, 2008). Studies have consistently highlighted that perceived risks directly influence destination choice and travel behavior. According to Karl (2018), tourists’ perceptions of risks associated with a destination significantly impact their willingness to visit. Several researchers have examined the effects of various types of risks—such as physical, financial, or emotional—on travelers’ destination choices (Seyidov & Adomaitienė, 2016). For instance, Karl et al. (2020) used an integrated risk typology and survey data to explore how past experiences and perceived risks interact with specific destination attributes during decision-making. These findings align with broader theories, such as the multistage travel decision-making model, which identifies destination choice as a critical sub-decision influenced by risk and uncertainty (Quintal et al., 2010; Elias & Shiftan, 2012; Qin et al., 2023; Xie et al., 2020). Additionally, intuitive risk judgments—described as rapid, subjective assessments of risk (Slovic, 1987)—further shape tourists’ preferences and decisions. Early works by Roehl and Fesenmaier (1992) revealed that tourists base their decisions not solely on rational evaluations but also on their perceptions and emotional responses to potential risks. Despite the growing body of research, most studies focus on either individual risk perception or travel paradigms in isolation. Limited efforts have been made to integrate these two dimensions and explore how their interaction influences overall travel decisions in a quantitative way.

Drawing on the insights from the literature, the subsequent sections will detail the research methodology, analysis process, and findings.

Methodology

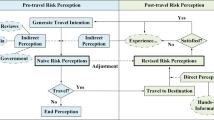

In this section, we briefly introduce our proposed methodology for evaluating tourists’ risk perception, encompassing both the public and individual levels. We systematically employ relevant data sources to implement this method. Additionally, we offer a succinct elucidation of how this approach can be used to characterize individual travel profiles effectively by integrating individual risk perceptions with travel paradigms. Subsequently, through rigorous statistical analysis, we can derive valuable insights and recommendations for tourists. To visually illustrate our approach, Fig. 1 portrays the proposed methodology, demonstrating the depiction of public-to-individual risk perception, the relationship between travel paradigms, and the risk perception framework (tourism paradigm recommendation model).

Data

For our research, we rely primarily on two distinct data sources obtained from Ctrip (https://www.ctrip.com). It is now officially known as Trip.com Group, and is one of the largest online travel agencies (OTAs) in the world, headquartered in China. It provides a wide range of travel-related services, including booking flights, hotels, trains, and vacation packages. For this study, Ctrip is used as a data source due to its extensive database of user-generated content, such as travel notes, reviews, and ratings, which provide valuable insights into tourists’ perceptions and behaviors.

The first data facet comprises tourism questions and answers (Q&A) specifically related to Xinjiang province, while the second encompasses travel notes along with various travel paradigms of the tourists, revealing their individual preferences. To ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant topics, we manually annotate a total of 14,320 Q&A text entries related to Xinjiang, encompassing a wide range of issues such as distance, route planning, physical exertion, weather conditions, and other concerns. The second data facet we utilize is the collection of 3035 travel notes, which serves as a primary source for our analysis. Each travel note documents the travelers’ experiences and emotions. Finally, we employ a dictionary method combined with a sentiment approach to comprehensively analyze our data. The details of the method will be recapitulated in the following subsections.

In addition to these two data facets, we collect supplementary information about the travelers who post the travel notes on the website, including the season of travel, trip duration, travel expenditure, travel companions, and travel way (chosen mode of transportation). These details are essential in constructing a foundational profile of each traveler, also known as one person’s travel paradigm, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Moreover, we gather the timestamps of when the notes are posted, and some authors even provide details of the hotels they stayed in, the activities they engaged in, and the routes they took during their trip. This information is invaluable in furnishing us with a reference for suggesting potential tour routes later. Subsequently, we present a specific example of a travel note from a visitor who stayed in Xinjiang. This brief excerpt vividly portrays the breathtaking scenery in the Altay Region:

“Amid a warm July, under the radiant sunshine and gentle breeze, the land of Xinjiang comes alive with vibrant colors and breathtaking landscapes. It is a place where nature’s gifts, including blooming flowers, majestic mountains, and flowing waters, harmonize with the tranquility of picturesque villages. This serene oasis offers a timeless escape, where one can immerse themselves in the symphony of nature’s “song” and be captivated by its enchanting “smile.” Every corner of this land reveals hidden treasures, inviting exploration and discovery.”

Undoubtedly, the textual content within a travel note encapsulates a myriad of insights and reflections on diverse aspects of the traveler’s experience. Through meticulous analysis of the travel notes, we can discern sentences containing crucial information about risk perception. These may encompass words associated with uncertainty, safety concerns, potential hazards, or emotions evoked by perceived risks.

The framework for measuring risk perception

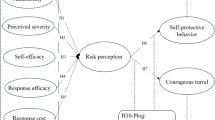

The formulated framework for gauging risk perception comprises two integral components: the establishment of Public Risk Perception (PRP) through keyword-based sentence weighting, followed by the subsequent development of Individual Risk Perception (IRP) through the application of sentiment analysis to assess emotional value, public risk perception provides a basis for individual risk perception, including the types of risks and the weights of the corresponding risks. As Fig. 3 denotes, the establishment of Public-to-Individual Risk Perception involves a systematic two-step process:

Step 1: Extract the keywords from the Q&A data to form a risk data dictionary

In the initial phase, we utilize Question and Answer (Q&A) data to annotate individual concerns or worries expressed by the public. Each query is classified into specific risk categories. For instance, the question, “What are the accommodation conditions? Is the service attentive?” can be distilled to the keyword “accommodation,” thereby identifying the associated accommodation risk. This keyword is subsequently added to a risk dictionary. To ensure the accuracy of risk classification and the corresponding dictionary, we convene an expert group for multiple rounds of annotation and validation. This collaborative effort culminated in the identification of various risk types and their associated terminologies, drawing also on existing literature that describes tourism risk categories.

Step 2: Identify the sentences in the travel notes according to the obtained dictionary, to quantify Public Risk Perception and Individual Risk Perception

In the second phase, we employ the established risk dictionary to conduct keyword searches within travel note data, extracting sentences that describe relevant risk types. The weight of these sentences is then utilized to compute PRP. To assess the emotional value of the identified sentences, we apply five distinct sentiment analysis methodologies. By averaging the results and applying inversion techniques, we quantify the perceived risk levels for each individual. Furthermore, the previously calculated PRP served as a weighting factor in deriving IRP, which integrates 23 distinct risk types.

Public risk perception mainly responds to the initial perceptions of the large population about the uncertainty of several types of risks, while individual risk perception reflects the individual’s overall cognition of the combined types of risks, with heterogeneity and unique feelings. The specific construction process will be elaborated in the section “The framework for building the risk perception metrics”.

The correlation between risk perception and travel modes

Furthermore, we propose an innovative approach aimed at investigating the relationship between individual risk perception and travel paradigms, utilizing Beta Regression techniques. The exploration of the correlation between risk perception and travel modes mainly contains two steps:

Step 1: Use Beta regression to rank travel paradigms by their effectiveness in reducing perceived risk

For the first step, we employ Beta regression to determine which mode of transportation is most effective in reducing perceived risk. This analysis incorporates key influencing factors such as travel season, trip duration, travel companions, and expenditure, allowing us to rank travel modes based on their impact on IRP. Additionally, the regression coefficients provide insights into which factors travelers prioritize when making decisions. To enhance the robustness of our findings, we validate the results using a Random Forest model (Appendix 1), ensuring consistency in identifying key determinants of risk perception.

Step 2: Identify travel preferences of low-IRP group people

In the second step, we extend our analysis beyond regression by conducting a clustering-based investigation of travel-related characteristics that cannot be directly included in the model. By ranking individuals based on their IRP scores, we identify those with the lowest perceived risk and analyze their travel preferences, including accommodation choices, preferred tourist attractions, and common travel routes. Furthermore, we explore variations in risk perception across different risk types among individuals with extreme IRP—both high and low. This deeper understanding provides valuable insights for policymakers and tourism managers, enabling them to design travel recommendations that align with varying levels of risk perception while optimizing overall travel experiences. The specific exploration and discussion process will be described in detail in section. “Investigating the relationship between individual risk perception and travel paradigm”.

The framework for building the risk perception metrics

Before delving into the methodology for measuring public risk perception, it is crucial to distinguish it from individual risk perception. Public risk perception encompasses the collective awareness and apprehension of the general populace regarding various categories of risks, including those related to climate, health, or safety. This aggregated viewpoint often mirrors societal attitudes, media impact, and cultural influences across a diverse population (Yang, 2024; Janzik et al., 2024). Conversely, individual risk perception relates to the personal evaluation by a specific individual of the probability and implications of specific risks, which is influenced by personal experiences, beliefs, and cognitive biases.

Risk perception is thought to be a subjective feeling and assessment of uncertainty that is motivated by variations in different people’s psychological, as Table 1 depicts, in the past, people used interviews, questionnaires, and some psychological analysis methods to measure people’s risk perception (Siegrist et al., 2021; Árvai et al.,2023), but these methods can be unprecise because only few individual samples are selected, and people only get the information through some hearsay experiences. Thus, in the novel metrics of tourism risk perception, we use text mining methods to combine the intuitive results of people who have been there with the uncertainty of the consequences that have happened to the individuals. Results for different types of risks as a definite synthesis of the uncertainty of the consequences that have already occurred in an individual, and the collected samples of individuals are tourists who have been to the final destination, so the metric is accurate, and also the travel experience of these people who have been there can be used to give the travel paradigm in the lowest case of risk perception, to provide reference for those who have not been there in the future.

At the same time, we believe that there are two stages of traveling, before or after travel (Fig. 4), pre-travel people have a lot of uncertainties about the destination but also want to know some information in advance, so people will go to Q&A sites and ask questions, such as “What is the most appropriate mode of transportation for traveling from Xi’an to Xinjiang?”. and “Will Urumqi be very uncomfortable to travel in summer temperature?”, waiting for some answers, and these questions reflect the uncertainty of the people who have not yet traveled, and each question and answer can be judged as a certain type of risk according to the reference of existing literature and manual annotation methods. According to existing travel note data, the size of each risk type is quantified (public risk perception). Also, combined with the weight for each risk type, the whole risk perception for each individual is quantified, which constructs a measure of individual risk perception, with individual heterogeneity. This measure is constructed based on the textual travel notes of the people who have already been there, so the quantification comes out to be more accurate. It can provide a reference for people who have not traveled before to find the optimal travel paradigm and reduce the perception of risk.

The construction of public risk perception

The development of a framework for measuring public risk perception entails the categorization of various risk types identified within the travel Q&A data. This process necessitates domain knowledge and expertise to accurately align the Q&A data with specific risk categories. The risk types delineated in prior literature, encompass factors such as route selection risk, traffic risk, expense risk, equipment risk, seasonal risk, entry risk, time risk (when to go), climate risk, health risk, accommodation risk, security risk, openness risk, agency risk, food (dining) risk, clothing risk, shopping risk, tradition risk, covid risk, and communication risk, constitute the foundational elements for this categorization (Feng et al., 2022).

By grouping the identified risk types, we can create a comprehensive and meaningful classification framework for public risk perception. This framework not only incorporates the established risk types from previous literature but also uncovers new risk types that emerge from the analysis, such as snow risk, ticket risk, queuing risk, and nation risk. While manual annotation can be time-consuming and labor-intensive, it ensures the accuracy and quality of the results, especially when domain knowledge is essential (Bao & Datta, 2014; Wei et al., 2019). Automatic annotation methods, although useful in some cases, may not be as suitable when precise categorization and understanding of specific risk types are required (Boella et al.,2014), that is why in our study, we also employ manual annotation to ensure the accuracy of our risk type classification.

The detailed steps for identifying potential risks and constructing a public risk perception metric are as follows, as Fig. 5 describes:

Step 1. Convene a discussion group comprising several experts and annotate the Q&A data on a line-by-line basis. Each Q&A entry is categorized into a specific risk type based on its keywords, followed by the execution of a final KAPPA test after the completion of categorization by all participants (Li et al., 2020).

Step 2. Specific keywords are allocated to each of the manually annotated risk types, thereby creating an initial risk dictionary. Subsequently, these keywords are incorporated into all the travel notes, enabling the extraction of sentences encompassing those keywords.

Step 3. Sentences containing a specific keyword representing a particular risk type are extracted, as outlined by Huang & Li (2011). In the process of constructing the final keyword dictionary, it is essential to iteratively determine the optimal number of keywords to include in the lexicon. This determination is achieved through the evaluation of two metrics: recall and precision, as highlighted in the study by Feng et al. (2022). It was observed that after eight rounds of iteration, both metrics consistently surpassed 90% stability, as indicated in Fig. 6. This outcome signifies that the final constructed dictionaries successfully passed the consistency test, leading to the preservation of the identified set of dictionaries. Count indirectly reflects the significance attributed to each specific risk type.

Table 2 illustrates the identified risk types and detailed information, including descriptions and examples (both in Q&A data and travel notes data). Additionally, it includes correlated examples that serve to enrich our comprehension of the specialized process involved in identifying various types of risks. These concrete examples play a pivotal role in elucidating the nuances of each risk type, thereby contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the risk identification process. What can be seen is that the types of risks involved in the Q&A before traveling are people’s subjective perceptions because they did not go and had a lot of doubts and uncertainties about the place, whereas after arriving and completing the travel notes, they have their judgments about the different types of risks, and so the risk perceptions that are formed can be either positive (good comments, low risk perception) or negative (bad comments, high-risk perception) depending on the people’s real, intuitive assessment of how they feel about the risks when they are traveling.

Step 4. Following this identification process, data cleaning is conducted to eliminate any irrelevant sentences that may not contribute meaningful insights into risk perception. This crucial step ensures that the subsequent analysis is centered on pertinent and informative data, thus enhancing the overall quality of the findings.

Step 5. The public risk perception measure is defined as the ratio of the number of sentences about a specific type of risk to the total number of sentences referencing the 23 types of risks. This ratio, represented by Eq. (1), signifies the public perception of varying risk magnitudes and is denoted as the “Public Risk Perception” for risk type j. Sent_numberj refers to the number of sentences correlated with risk type j. There are 23 risk types in total, and the denominator represents the sum of the sentences containing all 23 risk types. PRPj represents the size of the public risk perception for a specific risk type and is calculated from a holistic perspective since the included sentences are derived from all visitors.

Here, the extraction results in 73,312 sentences containing the keyword and representing this specific risk type. This calculation offers a quantitative measure of the frequency with which a particular risk type is mentioned in the travel notes, relative to the total number of sentences representing all risk types, as derived from a dictionary method. This outcome assists in determining the relative significance or attention given to that specific risk type within the broader public perception of risks in the context of travel.

Given that the data is extracted from universal group Q&A data, this scale serves as a measure of the magnitude of public risk perception. As depicted in Table 3, the findings indicate that individuals exhibit the highest degree of concern for seasonal risk (16.7%), climate risk (10.1%), expense risk (8.0%), accommodation risk (7.8%), and risk associated with determining the timing of travel (7.6%). It is noteworthy that relatively few sentences contain information related to epidemic control, despite the substantial impact of the recent COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism industry. This can be attributed to the fact that individuals are permitted to travel when the pandemic situation is not severe. When examining travel notes, individuals are more inclined to depict aspects related to the travel destination rather than focusing on content associated with epidemic control. Therefore, individuals tend to prioritize their experiences during the travel process, resulting in minimal emphasis on risks such as covid (0.7%) and openness (1.9%) within this context.

Indeed, the Public Risk Perception (PRP) measure functions as an indicator of the collective risk perception held by a homogeneous group, encapsulating their shared concerns when evaluating risks. This measure can be effectively utilized as an objective weight in the subsequent development of the individual risk perception metric, providing valuable insights into the overall risk perception landscape within the specified group or context.

The construction of individual risk perception

To estimate individual risk perception (IRP), we consider the inherent variability among individuals and their diverse perceptions of travel experiences. This approach captures nuanced perspectives on travel-related risks, enriching our understanding of risk perception in this context.

In this study, five sentiment analysis techniques—Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BILSTM), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), and Bag-of-Words (BOW)—are employed, as they have been widely applied in previous studies (Feng et al., 2022). These models calculate sentiment probabilities for perceived risks in travel notes. By training the models on a corpus of sentences extracted in the section “Data”, the emotional polarity of text is automatically identified, with confidence scores provided for each sentiment (Han et al., 2022; Feng et al., 2022). This methodology supports the analysis of travelers’ behavior patterns and prominent topics in risk management.

The IRP calculation process proceeds as follows:

-

1.

Sentence-Level Sentiment Scores: For each sentence, sentiment scores are obtained using the five models.

-

2.

Averaging Across Models: Sentiment scores for each sentence are averaged across the five models to ensure robustness.

-

3.

Averaging Across Sentences: The overall sentiment score for an individual is calculated by averaging the scores of all sentences they mentioned regarding a specific risk type.

-

4.

Weighting by Perceived Risk Probability (PRP): The averaged sentiment score is multiplied by the PRP weight assigned to each risk type (e.g., climate risk, safety risk).

-

5.

Aggregating Across Risk Types: Summing the weighted scores across all risk types provides a total risk perception score for each individual.

Since higher sentiment scores reflect lower perceived risk, the aggregated IRP value is adjusted by subtracting it from 1 to ensure that higher values indicate higher levels of risk perception.

In Eq. (2), Sentiment_scoreji denotes the emotional score for risk j (j = 1,..23) derived through deep learning methods for one individual i, reflecting the satisfaction level. Here, PRPj represents the public risk perception within the population, serving as a weight for the specific risk type j. By aggregating the weighted sentiment scores, we can derive the overall individual risk perception for tourist j. This composite emotion encompasses potential risk events that may occur during a trip, considering each of the 23 risk types for different individuals.

After obtaining the individual risk perception of each tourist, a histogram of the IRP distribution is plotted, as depicted in Fig. 7. Most of the IRP values fall between 0 and 0.25 (1408 people), followed by 0.25–0.5 (1090 people) and 0.5–0.75 (223 people), with 189 people having IRP values between −0.25 and 0. As illustrated in Fig. 7, most of the individual risk perceptions are distributed above 0, indicating an overall positive sentiment regarding traveling to the area. However, their distribution still exhibits significant variation due to individual heterogeneity.

Investigating the relationship between individual risk perception and travel paradigm

The application of the IRP metric enables us to delve into the correlation between tourists’ risk perception and their choice of travel paradigms, offering profound insights into how risk perception influences their travel preferences.

What is the most risk-minimized paradigm of travel?

In pursuit of formulating a more comfortable travel plan conducive to risk mitigation, the selection of an appropriate travel paradigm emerges as of paramount importance. We endeavor to ascertain the particular pattern of travel associated with the lowest risk perception. This endeavor equips us to furnish well-substantiated recommendations to tourists, thereby facilitating informed decision-making.

Model formulation and likelihood ratio test comparison

The objective of this study revolves around conducting a comprehensive exploration of the intricate interplay among five pivotal factors that represent basic travel paradigms: travel duration (measured in days), travel expenditure, the season of travel, the composition of travel companions, and travel mode (the choice of transportation). This analysis aims to ascertain the magnitude of their influence on individual risk perception, as quantified by the dependent variable, Individual Risk Perception (IRP), delineated in section “The construction of individual risk perception”. Although the initial IRP values are calculated for over 3000 participants, many don’t specify their travel characteristics when submitting their travel notes. For this analysis, we select only the samples that included information about their choice of travel. However, we compute the IRP for all tourists, which continues to play a significant role when providing specific characteristics such as hotel selection, attraction choice, and itinerary planning. To provide a clear overview of the dataset used for this analysis, Table 4 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the samples. It categorizes the data by year, presenting the distribution and proportions of key variables such as travel season, mode of transportation, and composition of travel companions.

The IRP variable encapsulates the collective perceived magnitude of each individual’s comprehensive evaluation of the 23 distinct destination risk types, accounting for variations in individual behaviors and idiosyncrasies. The majority of individual risk perceptions exhibit a magnitude greater than 0, necessitating their normalization to a range between (0,1). While linear regression is commonly employed in various applications, it proves unsuitable for scenarios where the response variable is constrained to the interval (0,1), as it may yield fitted values that exceed the lower and upper boundaries of the variable of interest. Therefore, we aim to employ a specialized regression model designed for situations in which the dependent variable (y), in our case, IRP is continuously measured within the standard unit interval, i.e., 0 < y < 1. The proposed model is predicated on the assumption that the response follows a beta distribution, addressing the unique characteristics of such data, which underpins our adoption of beta regression. Beta regression is particularly suited for analyzing our dependent variable, which is bounded between 0 and 1, making it ideal for capturing the distributional properties of individual risk perception.

Afterward, through this approach, we can ascertain which specific paradigm category exhibits the highest correlation with individual risk perception. This helps people make rational choices of travel modes, reducing risk perception and uncertainty. The building model process is as follows: Firstly, for regression analysis, it is typical to model the mean of the response. It is also typical to define the model so that it contains a precision (or dispersion) parameter, which they are defined as E(y) = μ and \({\mathrm{var}}(y)=\frac{V(\mu )}{1+\varphi }\), where V (µ) = µ(1 − µ) so that µ is the mean of the response variable and φ can be interpreted as a precision parameter(Cribari-Neto & Zeileis, 2010), for fixed µ, the larger the value of φ, the smaller the variance of y. Then, let IRP1, …, IRPi be independent random variables, where each IRPi, i = 1, …, n, follows the density in beta distribution with mean µi and unknown precision φ. The model is obtained by assuming that the mean of IRPi can be written as:

Finally, g(·) is a strictly monotonic and twice differentiable link function that maps (0,1) into R. Considering the interaction nature between travel expenditure and travel duration, i.e., the longer the number of travel days, the more the travel expenditure is likely to be, we include a crossover term Expenditure × Duration to manifest and investigate the interaction effect between them. Here we conclude model 2, model 3, model 4, model 5, and model 6. Considering the other cross-items: expenditure × duration, expenditure × season, expenditure × companion, duration × season, and duration × companion. Therefore, we summarize them into the following models and list the coefficients and the reason for choosing these cross-items in Appendix 2. However, after testing, according to the p-values, it is obtained that these two cross terms are not significant, so we did not consider three or even more cross terms because the result is still meaningless according to two useless cross terms. And the five models are as Eqs. (4) to (8) follows:

and

and

and

and

In this study, the comparison of six models, represented by Eq. 3 to Eq. 8, is conducted using the Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT), a statistical method employed to compare the fit of two nested models. In this context, the more intricate model may potentially offer a superior fit to the data; however, it is imperative to statistically assess whether the added complexity is justified. The LRT computes a test statistic that gauges the disparity in fit between the two models and evaluates whether the more complex model enhances the fit significantly in comparison to the simpler model (Cribari-Neto & Zeileis, 2010).

Equations 4–8 represent expansions of Eq. 3, integrating additional predictors in the form of cross-items. The LRT outcomes reveal a significant decrease in model fit upon the inclusion of cross-items. The test p-values, as delineated in Table 5, exceed 0.1. Consequently, we reject the null hypothesis that Eqs. 4–8 outperform Eq. 3, and accept the alternative hypothesis that Eq. 3 affords a superior fit to the data.

As Eq. 3 represents the parsimonious model, we can derive its coefficients and diagnostic charts. Additionally, the Mean Squared Error (MSE) of Eq. 3 is calculated to be 0.0135, while the pseudo-R-squared value stands at 0.1318, indicating a well-fitted and robust model. The coefficients of the parsimonious model are detailed in Table 6.

Furthermore, Fig. 8 illustrates that the residuals exhibit a random dispersion around zero, devoid of discernible patterns such as curves or slopes, thereby substantiating the adequacy of Eq. 3 as a good fit. Consequently, we select Eq. 3 as our ultimate refined model, characterized by substantial explanatory power.

Also, in this study, we use the beta regression model to analyze and rank the importance of key factors influencing travel decisions. The results indicate that Expenditure and Duration are the two most influential factors in the dependent variable. Although their regression coefficients are relatively small, their statistical significance is very high (p < 0.01), warranting their prioritization in the ranking, which indicates duration and expenditure emerge as the two most critical considerations for travelers when considering individual risk perception.

Additionally, sub-variables under Travelway and Season also demonstrated strong importance and statistical significance, showing considerable explanatory power in the model. The choice of transportation is also important, with travelers often booking tickets during discounts for cost savings and to ensure availability. In contrast, the impact of Companion was relatively weaker, with only a few sub-variables showing significance.

To validate the robustness of these findings, Appendix 1 presents a supplementary analysis using the random forest method to assess the importance of variables. The results of the two methods are largely consistent, further supporting the reliability of the Beta regression conclusions. Details of the Random Forest results and implementations are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 in Appendix 1.

Summary on the above findings

-

(1)

Choose the expenditure they spent and the duration they stayed

The results show from the result of Eq. 3 that both expenditure (β = −0.09613, p < 0.01) and duration (β = 0.06105, p < 0.01) are significantly associated with individual risk perception. Specifically, we have:

Finding (1): As expenditure increases, individuals’ risk perception decreases, while risk perception decreases with a decrease in the duration of travel.

Indeed, travelers’ decision-making is significantly influenced by the interplay between traditional attributes like expenditure, duration, transfer type, journey purpose, risk perception, and cultural/sociodemographic factors. Both duration and cost are closely tied to these risk perceptions (Manca et al., 2023). This connection can be attributed to the idea that increasing resources for necessities such as sustenance, entertainment, and accommodations enhances travel comfort and quality, thereby reducing apprehension in unfamiliar environments. Simultaneously, a longer travel duration can increase individual risk perception due to the uncertainties associated with prolonged stays in a destination. Consequently, those with higher expenditures and shorter durations typically exhibit lower risk perceptions.

Remark on Finding (1): This finding coincides with people’s common sense, as we have explained above, which validates the effectiveness of the risk perception measure we proposed, and therefore the following findings are reliable.

-

(2)

Choose the best season

Finding (2): Compared to the autumn season, individuals’ risk perception is lower during spring, summer, and winter.

This finding suggests a predilection among individuals to visit Xinjiang during these seasons as opposed to autumn. This preference may stem from the recognition that autumn represents a peak travel period, characterized by heightened crowding compared to other seasons, consequently elevating visitors’ levels of risk perception. Also, studies have shown that there are seasonal variations in how tourists perceive the risk of traveling and their level of worry about being involved in some seasonal activities (Kummeneje et al., 2019).

The inclination towards spring, summer, and winter travel in Xinjiang resonates with the promotional narratives prevalent on travel websites. Each season presents unique landscapes and attractions. Spring showcases boundless grasslands and mountains, while summer features the ripening of fruits and melons, offering a delectable culinary journey, as well as an ideal period for traversing the Silk Road and immersing in exotic scenery. Winter in Xinjiang unveils snow-covered landscapes that provide a picturesque backdrop for winter activities and leisure pursuits.

The ranking of seasons in terms of preference for travel to Xinjiang, based on the analysis, as Fig. 9 depicts, is as follows.

-

1.

Spring

-

2.

Summer

-

3.

Winter

-

4.

Autumn

This finding implies that individuals tend to perceive a reduced level of risk when traveling to Xinjiang during the spring, summer, and winter seasons. The presence of varied natural landscapes and cultural encounters during these times likely contributes to a more favorable and enticing travel perception.

-

(3)

Choose the best travel way

Finding (3): People have a preference for cruising and cycling as a mode of transportation, as it offers a more enjoyable experience compared to ordinary travel by public transport and walking. They also prefer various ways that are interesting and relaxing.

Furthermore, except for cruising, cycling is generally perceived as a leisurely and relaxing means to explore a destination, which could account for the lower risk perception associated with combining cycling with cruising. Previous studies indicated that commuters’ preferences vary based on their attributes. Commuters often prefer cars, valuing familiarity and lower risk. Cautious commuters are more risk-aware (Xiang et al., 2023). The results indicate that regularly using public transportation or engaging in activities like walking (e.g., hiking) can be physically demanding, leading to increased fatigue and a consequently heightened perception of risk, which is not satisfactory. Based on the coefficient values, the ranking of preferred travel ways for Xinjiang (from low Individual Risk Perception to high Individual Risk Perception), as depicted in Fig. 9, is as follows.

-

1.

Cruising combined with cycling

-

2.

Self-drive combined with walking and cycling

-

3.

Self-drive combined with cycling

-

4.

Self-drive combined with public transport, walking, and cycling

-

5.

Self-drive combined with public transport

-

6.

Public transport combined with walking

-

7.

Self-drive combined with walking

-

8.

Self-drive combined with public transport, walking

-

9.

Self-drive

-

10.

Public transport

-

11.

Public transport combined with cycling

-

12.

Public transport combined with walking and cycling

-

13.

Walking

-

(4)

Choose the best companion

Finding (4): Traveling with friends is associated with lower risk perception (β = −0.12093, p < 0.05) compared to other accompanying types, such as traveling with couples, traveling with parents, traveling with kids, and traveling alone.

Travelers to relatively remote destinations such as Xinjiang are predominantly young individuals; however, the perceived safety concerns associated with such locations may be amplified. The choice of travel organization, and traveling in a group or alone (Adam, 2015), is contingent upon tourists’ risk perceptions. Furthermore, previous studies reveal that traveling in the company of friends serves as a risk-reduction strategy. Consequently, people exhibit a greater inclination to travel in pairs, preferring companionship with friends and partners, thereby mitigating the perceived level of risk and fostering a heightened sense of ease and peace of mind during their travels, which aligns with social support theory (Xiong et al., 2021). Based on the coefficient values, the ranking of the preferred accompanying options for Xinjiang, as illustrated in Fig. 9, is as follows.

-

1.

Travel with friends

-

2.

Travel with couples (not married)

-

3.

Travel with parents, Parents-kids tour, Travel with couples (married), Travel alone

-

1.

(These four ways are with no significant difference in reducing individual risk perception)

Figure 9 depicts the ranking of seasons, travel ways, and companions available for selection according to individual risk perception (from low to high). TW13 here refers to cruising combined with walking and cycling because we haven’t defined this in the coefficient table as an abbreviation. The outcomes reveal that numerous travel paradigm-related factors, encompassing expenditure, duration, season, travel mode, and companion, exhibit substantial associations with individual risk perception.

These findings carry practical implications for the formulation of efficacious risk management strategies and the communication of travel-associated risks to the public. Through comprehensive consideration of these factors, stakeholders within the travel industry can customize their approaches to mitigate specific concerns and bolster the safety and contentment of travelers.

What are the extreme risk perception group’s characteristics?

In this section, our attention turns to distinct population segments exhibiting low and high Individual Risk Perception (IRP), along with their associated travel behaviors. Following the ranking of individual risk perception values from highest to lowest, we identify the top and bottom 5% of the population as the extreme groups with high and low IRP, respectively. Subsequently, we tabulate the preferences of these extreme IRP groups in Appendix 3. Our objective in this section is to provide a comprehensive analysis that illuminates two facets: variances in different types of risk perception and the low-risk perception group’s specific travel preferences. These insights enable the formulation of recommendations for hotels, tourist spots, and travel routes, starting with general guidelines and progressing toward more targeted and context-specific management suggestions based on the preferences of individuals with extreme risk perceptions. Through this analysis, we aim to make a scholarly contribution to the existing literature on travel behavior and risk perception. Furthermore, our findings hold practical significance for informing risk management and communication strategies within the travel industry.

Discrepancies in perceptions of different risk types

Given that our individual risk perception encompasses 23 distinct types, we aim to conduct a cross-sectional comparison of the values associated with different risk types within the group. As delineated in Table 7, the foremost concerns pertain to the choice of travel season (0.95), the alignment of the season with climatic conditions (0.89), the duration of the trip (0.63), the local tradition (0.84), and the state of available accommodations (0.54). Concurrently, upon selecting the 5% of the population exhibiting high IRP, their most pronounced dissatisfactions also center on the season (19.36), climatic conditions (10.42), trip duration (6.51), expenditures (6.31), and route selection (6.24). Notably, these outcomes align with the overarching trends, signifying heightened dissatisfaction with these specific aspects. Furthermore, this particular cohort exhibits elevated discontent with accommodation, amenities, and ticketing arrangements.

For example, the seasonal factor with a low IRP people, Slow travel in the northwest with a sentiment score of 0.996 said, “It is summer, the water and sky are the same, blue water and sky, it is the most beautiful season of Saihu Blue”. Xiao Xu Hua, with an emotion score of 0.995, said, “The river valley grassland, you can see the beautiful sunset, a handful of shots are a big picture of the village of Wo Mu—summer Wo Mu village, wild flowers everywhere”. “The winter in the north is a black and white world, not as clear and transparent as the spring, as blue as the summer and as green as the autumn”, says Lu. For example, the accommodation factor with a low IRP people, Citizen Hu with an emotion score of 0.9888 said, “On the first day I arrived in downtown Karamay, I booked a hotel next to the Karamay River in advance, with a beautiful view outside the window and a sparkling view at night, which was a good start for the trip. A good start to the trip”. With a sentiment score of 0.9885, Happy Valley Master said, “We had a buffet dinner and then checked in to the better Hu Yang International Hotel, the hotel lobby is very well built because of the assistance from Shanghai, the service is also very good, quite big.”

Based on the findings, the manager of the places of interest can consider the following recommendations:

-

Climate and Weather Information: It is essential to furnish visitors with precise and comprehensive details regarding the climate and weather conditions corresponding to each season. This empowers individuals to make well-informed decisions regarding their preferred time of visit, taking into account their specific inclinations and the activities they intend to partake in (Verbos et al., 2018). Emphasizing the distinctive characteristics and attractions characteristic of each season, such as winter snowfall or springtime blossoms, aids them in aligning their travel plans with their desired experience.

-

Flexible Booking and Cancellation Policies: Providing flexible booking and cancellation policies can assuage apprehensions related to committing to a specific duration of stay. By affording potential visitors the flexibility to modify their travel plans following their preferences and unforeseen circumstances, such policies enhance overall satisfaction and trust (Pung et al., 2022).

-

Safe and Well-Maintained Accommodation: It is imperative to guarantee that the accommodation options near the site are not only safe but also pristine and diligently maintained. Emphasizing any supplementary safety measures that have been instituted to address visitor apprehensions, such as heightened cleaning protocols, contactless check-in/check-out procedures, and strict adherence to social distancing guidelines, is crucial (Jannach et al., 2014). Furnishing visitors with this detailed information instills a sense of security and significantly contributes to a positive and gratifying travel experience.

By implementing these recommendations, the manager of the tourist attractions can augment the overall travel experience in specific aspects, diminish particular types of risk perception, and advance visitor satisfaction and safety.

Other factors pertain to recommended travel paradigms

To delve deeper into the additional travel paradigm factors influenced by individual risk perception, a representative sample of individuals is examined to elucidate the comfort and rationality of their travel choices. The analysis specifically focuses on three distinct aspects: hotel selection, tourism attraction preferences, and tour route suggestionsFootnote 1.

-

Hotels

In our analysis, we concentrate on the top 5% of individuals exhibiting the lowest risk perception regarding accommodations. To illustrate their hotel preferences, we categorize them into five geographical directions within Xinjiang: east, west, north, south, and central regions. Subsequently, employing the Gaode Map API, we visually map the corresponding hotel information, utilizing distinct colors to symbolize each direction.

Figure 10 depicts the spatial distribution of the selected hotels, with green markers denoting hotels situated in the north, blue markers for the south, purple markers for the west, red markers for the east, and orange markers for the central region. Moreover, to furnish supplementary details, the numerical value within each marker signifies the star rating of the respective hotels.

The markers faithfully depict the spatial distribution of the selected hotels within Xinjiang, offering valuable insights into the preferences and decisions of individuals with low accommodation risk perception. This visualization not only enriches our comprehension of travel patterns within Xinjiang but also serves as a practical resource for travelers seeking accommodation options based on geographical regions and star ratings. Notably, the central region of Xinjiang, delineated in orange, corresponds to the location of hotels favored by individuals with the lowest individual risk perception, primarily concentrated around Urumqi. For detailed distributions of hotels among them, please refer to Appendix 4.

There are 53 three-star hotels, 27 four-star hotels, 14 five-star hotels, and 11 two-star hotels. As indicated in Table 8, this distribution reveals that the majority of the hotels are rated at three stars and above, with a concentration primarily in the north and central regions, and comparatively less in the south and east. Despite the relatively advanced state of the tourism industry in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, the economic conditions are not yet at the forefront of the country. Consequently, there is still a need for improvement in the quality of hotel services.

Based on the conclusion, endeavors to enhance the quality of hotel services could encompass facility upgrades, staff training enhancements, and the implementation of effective management strategies. By prioritizing these aspects, hotels can elevate their services to align with traveler expectations, consequently bolstering the reputation of the tourism industry in the region (Zhu et al., 2021).

-

Scenic Spots

The choices of tourists’ destinations are influenced by risk and uncertainty, both of which are concepts linked in some way to the potential loss that could result from an event (Quintal, Lee & Soutar, 2010). The influence of risk perception varies across destinations and evolves during the destination selection process, as noted by Williams and Baláž (2015). This variation is further shaped by the way individuals process information, as differences in how people acquire and interpret new information lead to variations in their destination choices.

In our investigation, we have examined the selection of places of interest by the lowest ten individuals with low Individual Risk Perception. We have employed the PageRank algorithm, originally developed by Google to assess the rank and importance of web pages, as a method for evaluating the significance of nodes within the travel routes of these ten individuals. By leveraging the PageRank algorithm, which is integral to refining the relevance and quality of search results, we aim to ascertain the popularity and importance of various scenic spots visited by these individuals (Langville & Meyer, 2004).

The significance of nodes is determined by their degree, or the number of connections to the node where the attraction is located. We posit that a higher degree correlates with a higher PageRank score, indicating that the node is likely to be a central or popular travel destination. As depicted in Fig. 11, nodes with degrees of 6 and 5 are less prevalent, while those with degrees of 2 and 3 are more common. Following the acquisition of the degree nodes, we computed the PageRank scores for different scenic spots, as illustrated in Table 9. The most noteworthy spots include Tianshan (0.029), Kanas Lake (0.025), Hormu (0.025), Jiuzhangzhi (0.023), Fish Viewing Platform (0.022), Wolong Bay (0.022), and Kanas (0.021). These findings suggest that these spots could be recommended to individuals planning future travel to Xinjiang.

-

Tour route

Accommodation choices are inherently influenced by individual preferences and personal considerations. Moreover, the selection of travel routes, which is profoundly shaped by personal factors, is particularly subjective. Our study concentrates on a cohort of ten individuals characterized by the lowest risk perceptions in route selection. These ten individuals are regarded as representative figures whose routes can be recommended to others. As delineated in Table 10, individuals with low-risk perceptions demonstrate a predilection for linear and circular routes, suggesting that these itineraries could serve as recommendations for individuals inclined to visit Xinjiang in the future. The visual representation of these routes can be observed through the utilization of ArcGIS software, as presented in Appendix 5.

Notably, although the findings presented in this subsection focus specifically on individuals with low-risk perception, they apply to those with high-risk perception.

Sensitivity analysis

The subsequent sensitivity analysis investigates the resilience of individual risk perception across temporal time, risk type dimensions. Additionally, it delves into the gender-specific distinctions in travel characteristics in the backdrop of risk perception. This sensitivity analysis not only reaffirms the earlier findings but also furnishes crucial insights for both researchers and practitioners within the tourism industry.

Robustness of IRP over time and gender: analysis of risk types

This subsection presents an analysis indicating that there is no substantial variation in the perception of each category of risk over time. Through a sensitivity analysis conducted over multiple years, Fig. 12 illustrates a gradual increase in individual-level perceived risk across different risk types from 2017 to 2022, without significant variance or disruption. This observation suggests that our IRP metric exhibits a degree of robustness. Moreover, based on this trend, it can be inferred that a similar trajectory may persist in 2023 and beyond. Consequently, managers of scenic spots should continue formulating appropriate policies aimed at mitigating travel risks for tourists in line with this ongoing trend.

The Kruskal–Wallis test was utilized to assess whether the IRP for various risk types exhibits temporal variations (McKight & Najab, 2010). The obtained p-value of 0.4599 leads us to reject the hypothesis positing differences across different years.

Based on the preceding analysis, it is inferred that spring constitutes the primary tourist season in Xinjiang. Consequently, it is recommended that managers intensify promotional endeavors highlighting the summer climate, seasonal esthetics, and related activities to enhance public awareness. Furthermore, about ticketing and pricing, offering corresponding preferential activities could mitigate perceived travel risks arising from financial concerns.

Likewise, the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test was employed to ascertain potential disparities in IRP across different risk types between males and females (Lin et al., 2021). The calculated p-value of 0.4567 suggests that gender does not engender discernible differences in IRP across various risk types, as depicted in Fig. 13.

Gender differences in travel characteristics: exploring season, mode of travel, and companionship

Additionally, we conduct beta regression and random forest analyses separately for men and women, yielding coefficient tables detailed in Appendix 5. Notably, the models are configured identically, and the coefficients with their respective standard errors from both models are extracted individually. Subsequently, t-tests are performed, and the resulting p-values are presented in Supplementary Table 18 within Appendix 6.

Finding (5): Results show that both males and females with shorter durations and higher expenditures resulted in lower perceived risk.

However, there are significant differences between men and women in the characteristics of season, mode of travel, and the companion they travel with, mainly:

Finding (6):

-

Men generally prefer to travel in the summer, while women believe that there is a greater perception of risk in going in the summer, related to the high summer temperatures and ultraviolet rays in Xinjiang, and women are relatively focused on skincare and whitening, believing that too much sun can affect the skin.

-

Men prefer self-driving to women. Men are more adventurous and women are relatively conservative, and men are more likely to drive by themselves.

-

Men, compared to women, believe that going with friends and going with couples (not married) will be less risky, while women are not different between the options of companionship.

The divergences observed between men and women concerning travel expenditure, duration of stay, seasonal preferences, mode of transportation, and companions underscore the influence of gender on travel arrangements, as depicted in Table 11. These distinctions predominantly stem from variances in personality traits, behavioral characteristics, risk perceptions, as well as psychological dispositions between men and women.

Conclusion

This study investigates the influence of risk perception with a specific emphasis on understanding the correlation between tourists’ risk perceptions and their travel behaviors. Through the analysis of textual real-time data sourced from tourism websites, a comprehensive risk perception framework is constructed, incorporating both public-level and individual-level perspectives. Also, this research explores the relationship between individual risk perception and tourists’ travel paradigms, including duration, season, expenditure, travel way, and travel companions, giving deep insights into how to better plan one’s trip and reduce individual risk perception to the largest extent during traveling, which factor should be paid more attention to.

Recommendations are based on the empirical results. This study extends beyond prior studies that predominantly concentrated on endorsing travel modalities, instead highlighting the incorporation of individual risk perception magnitudes. At the same time, the study has certain managerial significance. For the managers of scenic spots, the travel patterns of low-risk groups undeniably provide a reference for them to consider the risk perception of tourists in their future management decisions, and introduce more favorable management measures to increase tourism revenue according to the travel paradigm of the groups with lower individual risk perception, moreover, for tourists, referring to the travel patterns of low-risk-perceiving people, they can better plan their travel characteristics to minimize risk and improve travel satisfaction.

Using Xinjiang province as a case study, we find that individuals demonstrate specific concerns regarding the duration and expenditure aspects of their travel choices. The research findings indicate a preference for non-autumn seasons for travel, with a tendency towards unconventional modes of transportation such as cruises and cycling, diverging from traditional transportation methods. Moreover, the study underscores a reluctance among individuals to embark on solitary journeys, evincing heightened apprehension when traveling alone and displaying a preference for group or couple travel arrangements, coupled with a willingness to allocate higher budgets while shortening the travel duration to assuage perceived risks. Furthermore, individuals characterized by lower risk perceptions exhibit a heightened focus on climatic conditions, seasonal variations, cost considerations, and route planning. They display a predilection for selecting central accommodations in the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture and 3-star or higher-rated hotels in proximity to Urumqi, along with a greater inclination towards visiting scenic destinations in northern Xinjiang such as Tianshan and Kanas Lake, with travel itineraries predominantly concentrated in northern and western Xinjiang. Additionally, gender disparities engender differential preferences in seasonal choices, travel companions, and travel ways, prompting individuals to select more suitable approaches to mitigate their respective risk perceptions.

This research also has practical implications for public policy. Tourism managers can use the findings to develop policies that promote safer, more comfortable travel experiences. For instance, creating risk-reducing travel environments, offering off-season incentives, and providing clearer information about potential risks could alleviate tourists’ concerns. Furthermore, individual risk perceptions could guide tourists in making more informed decisions, such as opting for group travel (travel with friends), avoiding high-risk seasons (autumn), or selecting accommodations with higher safety standards. These insights could be applied not only to Xinjiang but to other destinations facing similar concerns.

This study still has several limitations. Primarily, as a result of the relatively limited occurrence of keywords employed within travel notes, the study fails to adequately emphasize the significant impact of the epidemic on tourism in Xinjiang, thereby neglecting the prominence of epidemic-related content within the textual data. Additionally, the website travel notes overlook the multi-sourced nature of data originating from distinct populations. In the future, the study can pay much attention to individual-specific information and attributes such as age, occupation, prior experiences, and backgrounds, all of which could wield substantial influence over travel patterns.

Data availability

Data are provided in supplementary files.

Notes

These factors are not discussed in the previous regression model because not everyone in the selected sample data submitted their routes, hotel information, and information on attractions they visited, and therefore could not be treated in a unified regression model and requires additional discussion.

References

Adam I (2015) Backpackers’ risk perceptions and risk reduction strategies in Ghana. Tour Manag 49:99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.02.016

Árvai J, Cohen AS, Lutzke L et al. (2023) I think, therefore I act, revisited: building a stronger foundation for risk analysis. Risk Anal 44(3):513–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.14177

Bao Y, Datta A (2014) Simultaneously discovering and quantifying risk types from textual risk disclosures. Manag Sci 60(6):1371–1391. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1930

Boella G, Caro LD, Ruggeri A et al. (2014) Learning from syntax generalizations for automatic semantic annotation. J Intell Inf Syst 43:231–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10844-014-0320-9

Buhalis D, Law R (2008) Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—the state of eTourism research. Tour Manag 29(4):609–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.01.005

Chen L, Zhang L, Cao S et al. (2020) Personalized itinerary recommendation: deep and collaborative learning with textual information. Expert Syst Appl 144:113070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2019.113070

Chi CGQ, Qu H (2008) Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: an integrated approach. Tour Manag 29(4):624–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.007

Cribari-Neto F, Zeileis A (2010) Beta regression in R. J Stat Softw 34:1–24. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v034.i02

Cui F, Liu Y, Chang Y et al. (2016) An overview of tourism risk perception. Nat Hazards 82:643–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2208-1

Elias W, Shiftan Y (2012) The influence of individual’s risk perception and attitudes on travel behavior. Transp Res A-Pol 46(8):1241–1251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2012.05.013

Feng Y, Li G, Sun X et al. (2022) Identification of tourists’ dynamic risk perception—the situation in Tibet. Hum Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01335-w

Gretzel U, Mitsche N, Hwang YH et al. (2004) Tell me who you are and I will tell you where to go: Use of travel personalities in destination recommendation systems. Inf Technol Tour 7(1):3–12. https://doi.org/10.3727/1098305042781129

Han Z, Shen M, Liu H et al. (2022) Topical and emotional expressions regarding extreme weather disasters on social media: a comparison of posts from official media and the public. Hum Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01457-1

Huang KW, Li Z (2011) A multilabel text classification algorithm for labeling risk factors in SEC form 10-K. ACM Trans Manag Inf Syst 2(3):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1145/2019618.2019624

Hunecke M, Blöbaum A, Matthies E et al. (2001) Responsibility and environment: ecological norm orientation and external factors in the domain of travel mode choice behavior. Environ Behav 33(6):830–852

Jannach D, Zanker M, Fuchs M (2014) Leveraging multi-criteria customer feedback for satisfaction analysis and improved recommendations. Inf Technol Tour 14(2):119–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-014-0010-z

Janzik R, Koch S, Zamariola G, Vrbos D et al. (2024) Exploring public risk perceptions of microplastics: findings from a cross‐national qualitative interview study among German and Italian citizens. Risk Anal 44(3):521–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.14184

Karl M (2018) Risk and uncertainty in travel decision-making: Tourist and destination perspective. J Travel Res 57(1):129–146

Karl M, Muskat B, Ritchie BW (2020) Which travel risks are more salient for destination choice? An examination of the tourist’s decision-making process. J Destin Mark Manag 18:100487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100487

Kim K, Park OJ, Yun S (2017) What makes tourists feel negatively about tourism destinations? Application of hybrid text mining methodology to smart destination management. Technol Forecast Soc 123:362–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.01.001

Kummeneje AM, Ryeng EO, Rundmo T (2019) Seasonal variation in risk perception and travel behaviour among cyclists in a Norwegian urban area. Accid Anal Prev 124:40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2018.12.021

Langville AN, Meyer CD (2004) Deeper inside pagerank. Internet Math 1(3):335–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427951.2004.10129091

Le-Klaehn DT, Hall CM (2015) Tourist use of public transport at destinations–a review. Curr Issues Tour 18(8):785–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.948812

Lepp A, Gibson H (2003) Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Ann Tour Res 30(3):606–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00024-0

Li J, Feng Y, Li G et al. (2020) Tourism companies’ risk exposures on text disclosure. Ann Tour Res 84:102986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102986

Lin T, Chen T, Liu J (2021) Extending the Mann‐Whitney‐Wilcoxon rank sum test to survey data for comparing mean ranks. Stat Med 40(7):1705–1717. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.8865

Lv Z, Wang M (2020) Applying Internet information technology combined with deep learning to tourism collaborative recommendation system. PLoS ONE 15(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240656

Manca F, Pawlak J, Sivakumar A (2023) Impact of perceptions and attitudes on air travel choices in the post-COVID-19 era: a cross-national analysis of stated preference data. Travel Behav Soc 30:220–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2022.10.006

McKight PE, Najab J (2010) Kruskal–wallis test. The corsini encyclopedia of psychology 1-1. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0491