Abstract

Around the world, many young children spend time supervising or being supervised by other children without adults. This can have both positive (e.g., strengthening sibling ties) and negative (e.g., hinder supervisor’s schooling) consequences for children, families, and communities. Population-based information from low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) is scarce on this phenomenon. Poisson random effect regression models using the most recent Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) and Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from 81 LMIC were built to estimate the prevalence of leaving children under five years-old under the supervision of another child younger than 10 years of age and the role of maternal education in this childcare arrangement. Prevalence of child-to-child supervision ranged from no supervision at all to 55.7% globally, with large variations across countries and regions. The highest prevalence was found in West and Central Africa. In 90% of the countries across all regions, higher maternal education was associated with lower prevalence rates of children supervised by another child. No clear pattern was found among the eight countries across four continents displaying the opposite trend. These findings call for context-based studies to identify determinants and consequences of this care arrangement and for continued support to mothers’ education to bolster the supervision and healthy development of child supervisors and supervisees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in studying the well-being of children without adult supervision, defined as either alone or with another child. A nurturing environment characterized by responsive caregiving and adequate supervision is pivotal to fostering early childhood development (Jeong et al. 2022). The experience can vary, however, as some children are left alone without an adult caregiver nearby while others receive partial supervision from an adult who may be a friend, a relative or a neighbor (Ekot, 2012; Ruiz-Casares and Heymann, 2009). Some children are cared for by older siblings, friends, or domestic workers who themselves are children (Gamlin et al. 2015). Indeed, children’s contribution to childcare is a common and normative practice in multiple contexts (Ruiz-Casares et al. 2018; Weisner, 2017). Though adults are usually physically present—within earshot & eyesight, child-to-child supervision also happens in their absence (Kline and Killoren, 2022; Ruiz-Casares et al. 2018a). This is clearly the case of unaccompanied child-headed households (i.e., those with no member aged 18 years or older), particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (Chademana and van Wyk, 2021; Goronga and Mampane, 2021) and also in the context of teenage parenthood in high-income countries such as the USA, where many adolescents every year become parents to their children (Mollborn, 2017; Powers et al. 2021). The public health and social consequences of these arrangements (e.g., childhood injuries and decrease in school attendance) may affect both the children who receive care and the children providing care (Bliznashka et al. 2023; Hendricks et al. 2021; Sadeghi-Bazargani et al. 2017; Swanson et al. 2018). Variations in childcare practices in line with the changing employment status of women have also been suggested to contribute (Doi et al. 2018; Khan and Meher, 2021), yet poorly explore this phenomenon as it pertains to child supervision in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). This study provides up-to-date prevalence of child-to-child supervision in LMIC and investigates whether mother’s education plays a protective role in this arrangement.

Child-to-child supervision (which can include sibling as well as care by a non-relative child) is a double-edged phenomenon. On the one hand, there are several advantages associated with children’s involvement in caring for younger children and siblings. It can promote personal growth and foster closeness and affection between family members (Kline and Killoren, 2022). It can also contribute to a sense of generosity and purpose in life among children who provide care (Dellazzana-Zanon et al. 2021). There is evidence that taking care of younger children can also help the supervising children develop problem-focused coping skills (Kelada et al. 2022), as well as self-confidence, autonomy, and positive relationships with siblings (Park, 2019). Promoting cultural values as part of age-appropriate caretaking can boost resilience and strengthen healthy family dynamics (Hendricks et al. 2021; Wei et al. 2021). Despite the advantages, child-to-child supervision can pose challenges and result in negative outcomes for supervisors and supervisees. For instance, there is evidence showing that it can increase the risk of unintentional childhood injuries as older children may not yet be fully aware of situations causing serious injuries to children under their care (Swanson et al. 2018). Additionally, it can prevent the supervising child from participating in activities that are essential for their well-being and personal growth, such as age-appropriate activities including peer socialization (Borchet et al. 2020). This can negatively impact social and educational development as caregiving responsibilities may interfere with children’s ability to complete school assignments or spend time with their friends (Stamatopoulos, 2018). In a study done in Türkiye, Akkan (2019) found that 12–14-year-old children who cared for their 0–4-year-old siblings faced a range of physical and emotional burdens as they had to prioritize the needs of their younger siblings at the expense of their own. Non-adult supervision can also lead to quarreling, anger, and violence between siblings (Järkestig-Berggren et al. 2019; Khan and Meher, 2021).

Outside the literature on home injuries, most studies examining non-adult supervision were conducted with adolescents (12–18 years old) as the supervisee. Indeed, very few studies have been done on supervision of grade-schoolers or very young children (i.e., infants, toddlers, and preschoolers). The existing gaps are even more pronounced in LMIC. When studying child supervision, attention to women—and most often mothers—is paramount as they are usually the primary caregivers of young children and tend to spend more time with them. Sociocultural beliefs often expect that women fulfill both caregiving and employment roles, posing challenges for women in maintaining a work-life balance (Okelo et al. 2022). The current literature, however, does not provide adequate evidence as to how mothers’ education may influence the likelihood of child-to-child supervision. The assumption may be that mothers with higher levels of education are more aware of potential harms caused by non-adult supervision. Higher levels of education may also lead to better job prospects and higher income for mothers, thus making daycare more affordable when available. In this way, maternal education can contribute to children’s health by increasing mothers’ knowledge and financial resources (Le and Nguyen, 2020). As a result, mothers may end up spending less time with their children to meet their financial needs. Additionally, children’s role in caring is often studied in a context of providing care to different groups of people including parents, grandparents, and siblings. Focusing primarily on the care and supervision provided by, and to children is imperative to better understand the phenomenon of child-to-child supervision in the context of the changing landscape of maternal education, and the impact of this care arrangement on children’s well-being. This study investigates the extent to which nationally representative samples of children aged under 5 years old are supervised by another child younger than 10 years old without the presence of an adult in a range of LMIC. Child supervision was investigated in the context of maternal education.

Materials and methods

Data sources and sample size

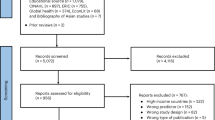

Data sources used for the present study consisted of 81 standardized, nationally representative, and population-based household surveys, including 67 Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) and 14 and Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). Both surveys were implemented in LMIC to monitor children’s well-being and use comparable multistage random sampling to generate a nationally representative sample. To study supervision practices for children under the age of five, we focused on specific items on child supervision introduced in MICS4 (see Section “Measures”). Since these items were optional, only countries that chose to include them were retained for our study. To obtain the most updated information, we included the latest wave of data collection for each country that were publicly available in July 2021. Survey dates in our sample ranged from 2010 to 2020. All survey data and questionnaires were obtained online from UNICEF (https://mics.unicef.org/) and DHS (https://dhsprogram.com/).

The total number of children available for analyses was 578,286 in 81 countries and depending on the type of analysis carried out these numbers were reduced (Fig. 1).

Measures

Several measures of interest were included in our analyses. Interviewers received training to avoid bias in questioning.

Child supervised by another child

We assessed the extent to which a child aged under five years was supervised by another child younger than ten years through a question included in the MICS and DHS. Specifically, this question was as follows: “Sometimes adults taking care of children have to leave the house to go shopping, wash clothes, or for other reasons and have to leave young children. On how many days in the past week was (name) left in the care of another child, that is, someone less than 10 years old, for more than an hour?” Responses ranged from zero to seven days. For the purposes of the current analyses, we combined responses from one to seven days to convert this measure into a dichotomous outcome (0 = zero days, 1 = one day or more), as we focus on breadth with a cross-country comparison, following earlier work (Ruiz-Casares et al. 2018b).

Mother’s education

Given the heterogeneity of each country’s education system and the varied distribution of mothers’ education level, we combined groups to dichotomize this variable of interest. For example, some countries had more than one post-secondary education levels, whereas others only had one. Moreover, some education levels of certain countries had a low case count, which might have led to convergence issues during statistical analysis. Therefore, to maximize the comparability of datasets across countries, we classified mother’s education in most countries into “Primary or below” or “Secondary and above”. The only exceptions were Belarus and Turks and Caicos, where all mothers had an education level of secondary or above. Therefore, in these two countries we regrouped the education categories as “Secondary” and “Above secondary”.

Control variables

Following the literature on child supervised by another child (Ruiz-Casares et al. 2018b), we included seven control variables. We considered demographic characteristics of the child, including sex (0 = male, 1 = female) and age (in months). We also considered demographic characteristics of the mother—marital status (3 categories: Yes, currently married; Yes, living with a partner; No, not in union) and age (in years). Household characteristics included: residence (0 = rural, 1 = urban) and household size (the total number of individuals living in the household). Lastly, we considered socioeconomic status using the Wealth Index Score (WIS) (Rutstein and Johnson, 2004), which is calculated using household characteristics (e.g., electricity, water, number of rooms), presence of material goods (e.g., television, telephone), and ownership of various goods (e.g., computer, camera). The WIS was divided into five quintiles within each country, where the lowest represented the poorest group and the highest represented the richest.

Statistical analysis and model selection

We conducted random-effect Poisson regression analyses with sampling weights to account for variation in selection probability. We ran three separate models in each country dataset for the risk of being supervised by another child: (1) base model without predictors or controls, (2) model adjusted by mother’s education, and (3) a fully adjusted model by mother’s education and seven control variables (i.e., child sex, child age in months, household size, mother’s marital status, mother’s age in years, wealth index, residence). For each of these models, we ran them once with missing cases included and once without missing cases, which affected only two variables (i.e., mother’s education and marital status). All analyses were performed using Stata 17 (StataCorp, 2021).

Certain variables were excluded from some countries’ fully adjusted models for various reasons. For Algeria, the household size, mother’s marital status, and mother’s age were not available. Next, for Argentina, we excluded residence because all participants reported living in an urban residence. Furthermore, we excluded mother’s education for Georgia, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, and Tonga because all mothers reported having secondary education. Lastly, for Qatar, wealth index was not available, and residence was also excluded because all participants reported living in urban residence.

Results

Unadjusted prevalence of child supervised by another child

Figure 2 and Table 1 show the raw prevalence values of children supervised by another child across 80 countries, without missing cases (N = 553,709). Barbados was excluded because convergence was not reached. See Supplementary Materials for the unadjusted prevalence across 81 countries with missing cases included (Table S1).

In the East Asia and Pacific (EAP) region, results showed that between 3.1% (Thailand) to 14.9% (Timor-Leste) of children under five were supervised by another child under ten. Mongolia, Myanmar, Kiribati, Samoa, and Laos reported higher prevalence of around 10%.

In Europe and Central Asia (ECA), results showed that countries in this region generally had a lower prevalence of children supervised by another child of the ages in focus compared to other regions, such that the lowest was 1.1% (Bosnia and Herzegovina) and the highest was 6.5% (Kyrgyzstan).

In the Eastern and Southern Africa (ESA) region, results revealed higher prevalence rates ranging from 10.2% (Eswatini) to 37.3% (Burundi). Other countries with high rates of children supervised by another child in this region were Uganda, Rwanda, and Malawi, which were around 30%.

In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), we observed similar results to prevalence rates found in EAP, with the lowest being 0.4% (Trinidad and Tobago) and the highest being 16.8% (Haiti). Belize also had a higher prevalence rate in this region, with 12.1% of children supervised by another child.

In the Middle East and North Africa region (MENA), results showed similar prevalence rates to EAP and LAC, ranging from 2.7% (Egypt) to 11.2% (Palestine). Tunisia also had a higher prevalence rate in this region (10.3%).

In South Asia (SA), like ESA, results showed relatively higher rates of children supervised by another child ranging from 6.4% (Bangladesh) to Afghanistan (30.4%). Among these countries, Nepal also had higher rates around of 15%.

Lastly, the highest prevalence of children supervised by another child was found in the West and Central Africa (WCA) region. Results showed that the lowest prevalence rate in the region was 9.6% (The Gambia) and the highest both in this region and across all countries was 55.7% (Chad). We also observed high prevalence rates in Central African Republic and Congo, which were around 40%.

Adjusted prevalence of child supervised by another child

Figure 3 and Table 2 show the prevalence of children supervised by another child across 63 countries (N = 516,629), adjusted by mother’s education and control variables (see “Measures” section). The following countries were excluded as they presented problems of convergence due to small number in the outcomes, which made multivariable analyses unstable: Belarus, Belize, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Costa Rica, Cuba, Georgia, Jamaica, Moldova, Montenegro, Serbia, Saint Lucia, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkmenistan, Turks and Caicos, Tuvalu, Ukraine, and Uruguay.

In EAP, after adjusting for the seven control demographic variables, results showed that between 1.1% (Samoa) to 6.3% (Kiribati) of children were supervised by another child. In general, we observed lower prevalence of children supervised by another child. For example, while Timor-Leste had the highest unadjusted prevalence (14.9%), the risk of being supervised by another child was reduced to 6.2% after accounting for other variables. However, results showed higher prevalence in the unadjusted versus the adjusted models for Thailand and Tonga.

In ECA, results demonstrated lower prevalence of children supervised by another child for most countries in the region after adjusting for demographic variables, such that values were close to zero. As a result, after excluding countries with very low prevalence rates, the lowest rate was 0.2% (Kazakhstan) and the highest was 5.6% (Macedonia). For Macedonia, results showed higher prevalence in the unadjusted versus the adjusted model.

In ESA, adjusted results also demonstrated lower prevalence of children supervised by another child after adjusting for demographic variables for all countries. Rates ranged between 8.5% (Lesotho) to 26.8% (Uganda).

In LAC, like previous regions, we observed lower prevalence of children supervised by another child after adjusting for demographic variables, with values ranging from 0.5% (El Salvador) to 30.5% (Haiti). However, there was higher prevalence in the adjusted compared to the unadjusted prevalence rates for Colombia, Haiti, Honduras, and Panama. Moreover, Haiti was the country with the highest percentage of children supervised by another child both in the unadjusted and the adjusted models.

In MENA, the prevalence rates were consistently lower in the unadjusted models compared to the adjusted models. After adjusting for demographic variables, the percentage of children supervised by another child were between 0.6% (Qatar) and 10.8% (Algeria). The only country with higher prevalence in the unadjusted versus adjusted results was Algeria.

In SA, for all countries in the region, we observed lower prevalence rates when accounting for demographic variables. The percentage of children supervised by another child ranged between 2.7% (Bangladesh) to 20.5% (Afghanistan).

Finally, in WCA, consistent with the pattern observed in other regions, results showed lower prevalence of children supervised by another child after adjusting for demographic variables, except for Gambia and Sao Tome and Principe. The lowest prevalence rate for this region was 3.6% (Ivory Coast) and the highest was 29.3% (Chad).

Mother’s education

Figure 4 and Table 3 show the IRR and the confidence intervals of the association between a child supervised by another child and maternal education across 75 countries, without missing cases (N = 543,086). Barbados, Georgia, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Tonga, and Turks and Caicos were excluded because they did not produce valid estimates. See Supplementary Materials for results with missing cases included (N = 566,442) (Table S1).

Overall, results revealed that higher maternal education (Secondary and above) was associated with lower prevalence rates of children supervised by another child. This pattern was observed across most countries in all regions. Interestingly, we observed that this was the opposite for a few countries (i.e., Cuba, Qatar, Samoa, Maldives, Jordan, Kyrgyzstan, Costa Rica, Montenegro), where lower maternal education (Primary and below) was associated with lower prevalence rates of children supervised by another child. The analyses per region should be replicated here.

Discussion

Prevalence of children caring for other children

Results from this study provide evidence that many children under 5 years spend time supervised by another child younger than 10 years without an adult around. While in some countries this phenomenon was uncommon (e.g., under 1% in Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, and Turks and Caicos Islands), in others, such as Burundi, Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, more than one-third of children under 5 years of age are reported to spend time home alone supervised by a child under 10 years of age. In Chad, that proportion reaches 55%.

Several factors may contribute to this care arrangement. Many countries—though not all, with high prevalence of child-to-child supervision are facing or have faced structural situations of instability following conflict or natural disaster (e.g., Afghanistan, Burundi, Chad, Nepal, Palestine, Rwanda, and Timor-Leste). Indeed, the breakdown of family-support services may compound customary practices of shared care involving young people as caregivers. Social and cultural norms as well as parents’ experiences and circumstances influence their attitudes about the appropriate age at which a child can be left under the supervision of another child or in charge of a younger sibling (Park, 2019). According to a study done by Wei et al. (2021) in Taiwan, non-adult supervision can be conceptualized in terms of taking on adult-like roles; a practice that aligns with cultural expectations surrounding children’s contributions to supporting their parents and younger siblings. Cultural norms and values can also explain different views on child-to-child supervision (van der Hoek, 2021). Archard (1993) for example argues that societies that have followed a different historical trajectory to Western Europe and North America do not make such clear-cut distinctions between children and adults. In West Africa for example research has shown that the distinction made between the phase of adulthood and that of childhood in much of Western Europe and North America is not as clearcut (Nsamenang, 1992, 2004). This has implications for conceptualizations of both adulthood and childhood and the roles each are supposed to play in their society (Twum-Danso, 2009; Twum-Danso Imoh, 2022; Twum-Danso Imoh and Okyere, 2020). Moreover, in many societies today, including those in Sub-Saharan Africa, transitions from childhood and adulthood are not based on chronological age, but instead on key markers that have been passed down from one generation to the next for hundreds of years, such as motherhood (in the specific case of girls) or economic independence (for boys in particular) (Nsamenang, 2004; Tafere and Chuta, 2020; Twum-Danso Imoh, 2019). Nonetheless, whereas some studies have shown that non-adult supervision practices vary due to the distinct gender roles (e.g., girls provided more child care and domestic work compared to boys (Becker and Sempik, 2019; Joseph et al. 2019; Wikle et al. 2018), others have found that there is no significant difference between boys and girls in terms of caring activities (Järkestig-Berggren et al. 2019).

Children of immigrant parents, as well as children of working or single parents may be more likely to experience home alone and non-adult supervision (Klassen et al. 2022; Londoño et al. 2022; Wikle et al. 2018). Sometimes, children may experience parentification, which occurs when children are expected to provide care in a manner that exceeds their capacities and abilities (Masiran et al. 2023). However, it is also important to note that the allocation of chores to children may follow a stepwise, non-random process in many communities. Studies by Nsamenang (1992, 2004), Serpell (1993), Lancy et al. (2010), and Punch (2001) illustrate that families communities put in place mechanisms to assess a child’s maturity and capability by assessing the tasks that they can complete, giving a more complex one only when they master simple ones. This continues until they can undertake the same level of tasks as adults do. A child’s caring experience is shaped by the roles and responsibilities assigned to them, which may include basic care, household chores, helping a younger sibling with homework assignments, and assisting with other tasks when parents are unavailable or busy (Kline and Killoren, 2022; Ruiz-Casares and Rousseau, 2010). Moreover, in some places a key tenet in the construction of childhood is that children are expected to provide care and to have responsibilities. It is not just part of socialization processes, but it is embedded in conceptualizations of childhood due to notions of mutual duty, reciprocal obligations that underpin both intergenerational and intra generational relations (Kassa, 2017; Twum-Danso Imoh, 2022). As a result, there is evidence that children can develop a positive perception of caretaking if they are supported and validated by their parents (Masiran et al. 2023) or communities (Lancy et al. 2010; Nsamenang, 1992, 2004; Serpell, 1993).

Finally, other factors contributing to child-to-child supervision include sudden changes in the family such as illness, the separation of parents, or the death of the main carer (e.g., due to HIV/AIDS or conflict). These circumstances have led to the emergence of child-headed households in LMIC, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (Chademana and van Wyk, 2021; Goronga and Mampane, 2021; Leu et al. 2018), either as a result of caregivers’ disposition or children’s own decisions (Ruiz-Casares, 2009; Ruiz-Casares et al. 2018b). Sibling care may be a necessity, as extended families are not always able to fill in the absence of parents since they may have also lost adults (Ndlovu, 2020). The decline and stagnation of care by extended families within contexts characterized by HIV/AIDs has been documented widely (Chademana and van Wyk, 2021; Inbaraj et al. 2020). All in all, the importance of studying child supervision in context cannot be understated. Even more so considering likely variations in people’s understanding of what being “home alone” means (e.g., with no adult? or child? in the same room? or housing unit?). Policies and programs to support child supervision also need to be responsive to needs and circumstances in each setting.

Maternal education and children caring for other children

Studies examining caregivers’ attitudes toward non-adult supervision and its impact on children’s well-being typically involve mothers. Our findings show that in most LMIC, more maternal formal education is associated with lower prevalence of children supervising other children without the presence of an adult. The protective nature of formal education may be at least partly explained by raising awareness of risks of inadequate supervision and of alternative childcare options. Education may influence parents’ perception of children’s skills and maturity to undertake child supervision. For instance, findings from a study in India showed that caregivers with more years of formal education and higher socioeconomic status reported better knowledge about unintentional childhood injuries and were more likely to engage in preventive measures; 93% of participants in the study were mothers (Inbaraj et al. 2020). Additionally, more educated caregivers may know of and be able to access good-quality daycare centers due to having higher salaries or employment benefits. More educated mothers may also be more likely to be working in the formal sector and therefore be away from home for more than one hour at a time. They may also have a larger support network through their spouse or their employment or professional circles, able to provide more supervision to children in their absence (Du et al. 2019).

Eight countries across all regions outside the African continent display the opposite trend, namely higher maternal education is associated with more young children being supervised by other children when adults are not around. This is the case of Kyrgyzstan and Montenegro in ECA, Costa Rica and Cuba in LAC, Jordan and Qatar in MENA, Samoa in EAP, and Maldives in SA. An earlier study conducted by Ruiz-Casares et al (2018b) found lower incidence rate ratios of number of days children were supervised by another child in relation to mother’s education in Costa Rica, Jordan, and Montenegro but not in Cuba; the other countries were not part of their study sample. It is difficult to explain this pattern of association because these countries do not all share the same traits impinging on child-to-child supervision. Human development index scores in these countries range from medium to very high (0.69–0.85), with Kyrgyzstan having the lowest score and Qatar having the highest (UNDP, 2021). Migration, economic factors, and employment opportunities may contribute to child-to-child supervision in some of these countries. For instance, in Kyrgyzstan, economic challenges such as unemployment and insufficient income have led many highly educated and qualified individuals to engage in labor migration to provide for their families (Critelli et al. 2021). While adult members of the extended family often take on caring responsibilities, children—particularly adolescent girls, frequently bear the burden of assisting with household chores and taking care of their younger siblings. This raises concerns about the quality of supervision these children receive and should be considered in future studies of maternal education and child care in this context.

Studies conducted with mothers of infants in Jordan (Alzoubi et al. 2018) and Qatar (Mraweh et al. 2022) revealed higher awareness of child abuse, home injury, and safety measures among mothers with higher levels of education. Nonetheless, these studies also documented widespread lack of awareness of relevant national laws and social services (the former); and first aid, injury prevention, safety measures and materials, and the proper age at which children can do certain activities on their own (the latter). Moreover, in a study in Türkiye, mothers occasionally left them unsupervised despite believing that their 0–3-year-old children were at moderate or higher risk of injury (Aslan and Parlatan, 2021), and two-thirds of parents in the study in Qatar believed that supervision by siblings was a safe practice (Mraweh et al. 2022). Besides highlighting the importance of raising awareness of proper safety measures and adequate supervision (Aslan and Parlatan, 2021), these findings surface the need to better understand the social and cultural context in which formally educated parents make childcare arrangements as women with higher levels of formal education may prefer child-to-child supervision over other childcare arrangements wherever children are commonly requested to supervise for learning purposes and as a way to balance family relations and value everyone’s contribution to the family.

Women across education levels can face difficulty balancing work and caring responsibilities. The existence of social interventions such as family policies to facilitate access to daycare can provide crucial alternatives to children staying home alone or with young siblings. Arranging for alternative childcare can be challenging for working mothers, including growing numbers in female- and single mother-headed households in countries such as Costa Rica (Gindling and Oviedo, 2008) and Cuba (Stavropoulou et al. 2020). Even for stay-at-home mothers, if women are heavily occupied (e.g., with household chores) their lack of availability for childcare may result in inadequate child supervision (Siu et al. 2019). Of course, attention needs to be paid to the implementation of these policies as current social assistance programs and free daycare and preschool services have been described to fall short of the needs of the population, for example in Cuba (Stavropoulou et al. 2020) and Montenegro (Bošković et al. 2021) (e.g., overcrowded or not accept children under 2 years- old). In consequence, many mothers have no choice but to leave their child with a family member—including children, search for private daycare, or even take the child to work. In Samoa, Brinkman et al. (2017) identified higher level of mother’s education as a major contributor to enhancing child development and the presence of someone at home who can take care of the child, as one of the reasons not to send children aged 2–5 years to early childhood education centers. Whether these alternative caregivers must be adults or not is unclear. Moreover, in their study of family policies in Montenegro, Bošković et al. (2021) posit that policies such as long and well-paid maternity leave may not result in better child care and supervision as they may negatively affect career prospects for mothers. Whether and how this applies to women across the formal education continuum needs to be further studied.

Effective programs to support child supervision

Social protection programs aimed at removing structural barriers to childcare and enhancing capacity to supervise can enhance child care and wellbeing. Interventions addressing structural barriers to adequate supervision include, for instance, policies to increase minimum wage or to facilitate flexible workking schedule, access to early childhood education and paid parental leave (Li and Zhang, 2023). There is accumulating evidence of the positive effects of such interventions on child health and development (Heymann et al. 2017; Nandi et al. 2016; Ponce et al. 2018), even if the extent to which those extend to the informal economy and any effects on child-to-child supervision require more research. Equally necessary is the evaluation of specific interventions—both programs and policies, aimed at addressing those barriers overtime and in a range of different contexts in LMIC.

Several interventions showed promise on increasing maternal awareness of risks and adequate supervision practices. The extent to which those curve supervision of children by other children, however, is not studied. During a study conducted in Egypt, Aly (2020) offered training sessions to both first-time and experienced mothers about how to prevent and respond to common home injuries. As a result of this intervention, both groups of mothers showed notable improvements in various domains such as active supervision and knowledge of emergency interventions. The education level of most participants, however, was very high (84% of first-time mothers and 63% of experienced mothers had a university education). Some studies and programs targeted mothers with lower levels of formal education in other contexts. For instance, studies in Egypt (Ayed et al. 2021), Iran (Cheraghi et al. 2014), and Guatemala (Domek et al. 2019) reported increases in mothers’ knowledge of safety behaviors for young children. None of these studies explored whether these interventions have any impact on the occurrence and frequency of child-to-child supervision. Moreover, oftentimes, studies only use self-report measures and do not explore the effects of the training on supervision practices or outcomes. Notably, a study conducted in Canada, authors examined the effectiveness of a program called Supervising for Home Safety on mothers’ supervision behaviors (Morrongiello et al. 2013). As part of this program, mothers were taught about children’s physical and cognitive development stages, risk factors for home injuries, and ways to improve safety behaviors by addressing barriers to adequate child supervision. Findings demonstrated that this program led to an increase in supervision among mothers of children aged 2–5.5 years and a reduction in the amount of time children were left unattended. More research like this is needed, particularly in LMIC contexts. Educating mothers about the importance of adequate supervision may ultimately reduce inadequate supervision, but more research is needed to examine this relationship.

Few studies exist on interventions aimed at preparing children for safe caregiving behaviors. Some programs exist in high-income countries, yet most have not been evaluated and they generally target children older than 10 years (Ruiz Casares and Kilinc, 2021). A rare offering for younger children, Safe Sibs is an online program offered to children aged 7–11 years and their younger siblings (2–5 years) in Canada to enhance the supervision knowledge and practices of child supervisors (Schell et al. 2015). Along with improved supervision knowledge, child supervisors who participated in the program demonstrated improved proactive safety behaviors when caring for younger siblings. In societies where child-to-child care are normative practices, learning to provide childcare often happens gradually and informally as children take increasingly complex tasks and responsibilities. Nonetheless, interventions to enhance the knowledge and skills of child supervisors and supervisees can contribute to preventing injuries and promoting healthy child development. This is the case, for instance, of Careful Cubs, a program in Uganda that helps grade one students recognize hazards and engage in personal safety behaviors (Swanson, 2022). This is an area that deserves attention by program designers and researchers alike, particularly in LMIC. As mentioned earlier, though, a priority in research and intervention must go beyond enhancing individual knowledge and rather establish the environmental conditions and supports that children need to thrive such as access to early childhood education programs.

Strengths and limitations

This study used rigorous methods to analyze nationally representative information from many LMIC. It is further unique by addressing the supervision of very young children. An interdisciplinary team with expertise in sociology, child development, and child rearing in a range of cultural contexts contributed diverse perspectives needed towards the interpretation of the complex phenomenon under study.

Several limitations must be noted. First, regarding the dataset, analyses were performed separately by country rather than pooled due to variations in sampling and weights. Only countries with publicly available datasets in July 2021 were included in our study. The datasets excluded children supervising other children without adults in non-household settings such as in orphanages or in the streets. Second, regarding survey respondents, in MICS, information was provided by mothers or caregivers of children under 5 years, while information was provided by biological mothers in DHS. This may have influenced the provision of information about orphans and foster children as well as respondent’s perceptions of the child ability to supervise/be supervised by another child. The use of dialects and local childcare norms may have influenced respondents’ answers too, particularly in contexts where children supervising other young children is not considered adequate care. This is despite standardization and translation of tools and training of enumerators on non-biased questioning. Third, low prevalence of children supervised by other children in some countries resulted in their exclusion in some analyses and wide confidence intervals. Fourth, pertaining comparable variables, disparate education systems across countries forced us to group different levels of education yet may hide differences within those groups as well as countries. Similarly, lack of indicators across all countries to measure relevant variables such as maternal employment, immigration status, and childhood injuries limit our ability to perform global analyses. Particularly relevant will be to incorporate immigration and employment besides marital status in future models to explain the risk of child-to-child supervision. For instance, to explore whether higher maternal education provides single mothers with better employment opportunities while also forcing them to prioritize work over caring for their children since earning a better income ensures financial stability, and how this may be linked to changes in child-to-child supervision. Future analyses should look at this information within countries and regions, as natural disasters, political violence, and presence/absence of family-support polices may help explain child-to-child supervision patterns. Also needed are targeted qualitative studies to understand how these associations unfold in specific contexts and not in others. At the individual level, since the child supervisor is unknown, it is not possible to assess whether gender, age, or ability influence this childcare arrangement or the impact that it may have on their wellbeing or education. Finally, seasonal variations in child supervision as well as data collection are not considered in our analyses yet may contribute to the interpretation of findings.

Conclusions

Population-based estimates from this study confirm that child-to-child supervision in the absence of adults occurs in most LMIC. We hope these results will provide the basis for future studies on this phenomenon as the link between the risk of child-to-child supervision and further learning and health outcomes, beyond the risk of injuries, is grossly understudied. Whereas maternal education seems to be protective in most countries, there are notable exceptions. We need to determine what socioeconomic and other factors may influence caregivers’ decision to leave their children under the supervision of another child when adults are not around. Maternal education alone cannot provide the full picture. To assist with the interpretation of these findings, research focused on context (e.g., policies and practices surrounding parental employment) and socio-cultural norms (e.g., status of children and expectation regarding caretaking across age and sex groups) are needed in these settings. The overwhelming majority of studies that focus on interventions intended to improve mothers’ knowledge about appropriate supervision focus primarily on home injuries without adequately exploring how these interventions may impact the frequency and incidence of child-to-child supervision. There is also an urgent need to develop and evaluate interventions aimed at educating children on proper and safe supervision practices in LMIC.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study were obtained online and are available in UNICEF (https://mics.unicef.org/) and DHS (https://dhsprogram.com/) websites.

References

Akkan B (2019) Contested agency of young carers within generational order: older daughters and sibling care in Istanbul. Child Indic Res 12(4):1435–1447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9579-7

Aly HMA (2020) Education program for new and experienced mothers around child-hood accidents safety and emergency intervention J Nurs Health Sci 9:16–32. https://doi.org/10.9790/1959-0906071632

Alzoubi FA, Ali RA, Flah IH, Alnatour A (2018) Mothers’ knowledge & perception about child sexual abuse in Jordan. Child Abus Negl 75:149–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.006

Archard D (1993) Children: Rights and Childhood. Routledge. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mcgill/detail.action?docID=235107

Aslan D, Parlatan ME (2021) Safety issue at home: what is mothers’ concern, what they do, and what they need? Int Prim Educ Res J 5(3):260–271

Ayed MM, Yousef FK, Elsherbeny EM, Anwr DB (2021) Webinar Effectiveness in Teaching Mothers regarding Accident Prevention and First Aids in Children during Corona Virus Pandemic. Assiut Sci Nurs J 9(24):62–72

Becker S, Sempik J (2019) Young adult carers: the impact of caring on health and education. Child Soc 33(4):377–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12310

Bliznashka L, Jeong J, Jaacks LM (2023) Maternal and paternal employment in agriculture and early childhood development: a cross-sectional analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data. PLOS Glob Public Health 3(1):e0001116. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001116

Borchet J, Lewandowska-Walter A, Połomski P, Peplińska A, Hooper LM (2020) We are in this together: retrospective parentification, sibling relationships, and self-esteem. J Child Fam Stud 29(10):2982–2991. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01723-3

Bošković B, Churchill H, Hamzallari O (2021) Family policy and child well-being: the case of Montenegro in the European perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(17):Article 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179118

Brinkman S, Sincovich A, Vu BT (2017) Early Childhood Development in Samoa (AUS0000129). World Bank, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.1596/32262

Chademana KE, van Wyk B (2021) Life in a child-headed household: exploring the quality of life of orphans living in child-headed households in Zimbabwe. Afr J AIDS Res 20(2):172–180. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2021.1925311

Cheraghi P, Poorolajal J, Hazavehi SMM, Rezapur-Shahkolai F (2014) Effect of educating mothers on injury prevention among children aged <5 years using the Health Belief Model: a randomized controlled trial. Public Health 128(9):825–830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2014.06.017

Critelli FM, Lewis LA, Yalim AC, Ibraeva J (2021) Labor migration and its impact on families in Kyrgyzstan: a qualitative study. J Int Migr Integr 22(3):907–928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00781-2

Dellazzana-Zanon LL, Zanon C, Tudge JRH, Freitas LBdeL (2021) Life purpose and sibling care in adolescence: possible associations. Estudos Psicol 38:Article e200038. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0275202138e200038

Doi S, Fujiwara T, Isumi A, Ochi M, Kato T (2018) Relationship between leaving children at home alone and their mental health: results from the A-CHILD study in Japan. Front Psychiatry 9:192. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00192

Domek GJ, Macdonald B, Cooper C, Cunningham M, Abdel-Maksoud M, Berman S (2019) Group based learning among caregivers: Assessing mothers’ knowledge before and after an early childhood intervention in rural Guatemala. Glob Health Promot 26(2):61–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975917714287

Du F, Dong X, Zhang Y (2019) Grandparent-provided childcare and labor force participation of mothers with preschool children in Urban China. China Popul Dev Stud 2(4):347–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-018-00020-3

Ekot M (2012) Latchkey experiences of school-age children in low-income families in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Afr Dev 37(3):Article 3. https://doi.org/10.4314/ad.v37i3

Gamlin J, Camacho AZ, Ong M, Hesketh T (2015) Is domestic work a worst form of child labour? The findings of a six-country study of the psychosocial effects of child domestic work. Child’s Geogr 13(2):212–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2013.829660

Gindling T H & Oviedo L (2008) Single mothers and poverty in Costa Rica (IZA Discussion Papers No. 3286). Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn

Goronga P, Mampane MR (2021) Resilience processes employed in child-headed households in Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe. J Afr Educ 2(3):133–161. https://doi.org/10.31920/2633-2930/2021/v2n3a6

Hendricks BA, Vo JB, Dionne-Odom JN, Bakitas MA (2021) Parentification among young carers: a concept analysis. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 38(5):519–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00784-7

Heymann J, Sprague AR, Nandi A, Earle A, Batra P, Schickedanz A, Chung PJ, Raub A (2017) Paid parental leave and family wellbeing in the sustainable development era. Public Health Rev 38(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0067-2

Inbaraj LR, Sindhu KN, Ralte L, Ahmed B, Chandramouli C, Kharsyntiew ER, Jane E, Paripooranam JV, Muduli N, Akhilesh PD, Joseph P, Nappoly R, Reddy TA, Minz S (2020) Perception and awareness of unintentional childhood injuries among primary caregivers of children in Vellore, South India: a community-based cross-sectional study using photo-elicitation method. Inj Epidemiol 7(1):62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-020-00289-4

Järkestig-Berggren U, Bergman A-S, Eriksson M, Priebe G (2019) Young carers in Sweden—a pilot study of care activities, view of caring, and psychological well-being. Child Fam Soc Work 24(2):292–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12614

Jeong J, Bliznashka L, Sullivan E, Hentschel E, Jeon Y, Strong KL, Daelmans B (2022) Measurement tools and indicators for assessing nurturing care for early childhood development: a scoping review. PLOS Glob Public Health 2(4):e0000373. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000373

Joseph S, Kendall C, Toher D, Sempik J, Holland J, Becker S (2019) Young carers in England: findings from the 2018 BBC survey on the prevalence and nature of caring among young people. Child 45(4):606–612. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12674

Kassa SC (2017) Drawing family boundaries: children’s perspectives on family relationships in rural and urban Ethiopia. Child Soc 31(3):171–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12200

Kelada L, Wakefield CE, Drew D, Ooi CY, Palmer EE, Bye A, De Marchi S, Jaffe A, Kennedy S (2022) Siblings of young people with chronic illness: caring responsibilities and psychosocial functioning. J Child Health Care 26(4):581–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/13674935211033466

Khan S, Meher Z (2021) Sibling relationship and expression of anger among the children of working women. Pak J Physiol 17(2):38–41

Klassen CL, Gonzalez E, Sullivan R, Ruiz-Casares M (2022) I’m just asking you to keep an ear out’: parents’ and children’s perspectives on caregiving and community support in the context of migration to Canada. J Ethn Migr Stud 48(11):2762–2780. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1707647

Kline GC, Killoren SE (2022) Adolescents’ perceptions of sibling caregiving. J Fam Issues 44(9):2239–2257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X221079330

Lancy D F, Bock J. & Gaskins S (2010) The Anthropology of Learning in Childhood. AltaMira Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mcgill/detail.action?docID=480070

Le K, Nguyen M (2020) Shedding light on maternal education and child health in developing countries. World Dev 133:105005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105005

Leu A, Frech M, Jung C (2018) Young carers and young adult carers in Switzerland: caring roles, ways into care and the meaning of communication. Health Soc Care Commun 26(6):925–934. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12622

Li Z-D, Zhang B (2023) Family-friendly policy evolution: a bibliometric study. Human Soc Sci Commun 10(1):303. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01784-x

Londoño T, Gulbas LE, Zayas LH (2022) Sibling relationships among U.S. citizen children of undocumented Mexican parents. Fam Process 61(2):873–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12685

Masiran R, Ibrahim N, Awang H, Lim PY (2023) The positive and negative aspects of parentification: an integrated review. Child Youth Serv Rev 144:106709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106709

Mollborn S (2017) Teenage mothers today: what we know and how it matters. Child Dev Perspect 11(1):63–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12205

Morrongiello BA, Zdzieborski D, Sandomierski M, Munroe K (2013) Results of a randomized controlled trial assessing the efficacy of the Supervising for Home Safety program: impact on mothers’ supervision practices. Accid Anal Prev 50:587–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2012.06.007

Mraweh G, Mustafa M, Lorenzo LC, Rosales N, Singh K, Salameh K (2022) Parents’ knowledge and perception toward unintentional home injury in children and safety measures in qatar: a cross-sectional study archives of pediatrics. Arch Pediatr 7:2575–2825. https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-825X.100225

Nandi A, Hajizadeh M, Harper S, Koski A, Strumpf EC, Heymann J (2016) Increased duration of paid maternity leave lowers infant mortality in low- and middle-income countries: a quasi-experimental study. PLOS Med 13(3):e1001985. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001985

Ndlovu NP (2020) Financial Security Of Child- And Youth-Headed Households In South Africa [Masters, University of KwaZulu-Natal]. https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/handle/10413/20506

Nsamenang A B (1992) Human development in cultural context: a third world perspective. SAGE Publications

Nsamenang A B (2004) Cultures of human development and education: challenge to growing up African. Nova Science Publishers

Okelo K, Nampijja M, Ilboudo P, Muendo R, Oloo L, Muyingo S, Mwaniki E, Langat N, Onyango S, Sipalla F, Kitsao-Wekulo P (2022) Evaluating the effectiveness of the Kidogo model in empowering women and strengthening their capacities to engage in paid labor opportunities through the provision of quality childcare: a study protocol for an exploratory study in Nakuru County, Kenya. Human Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01260-y

Park S (2019) Understanding child supervision through a different lens: perspectives of South Korean caregivers and adolescents in Toronto, Canada. McGill University. https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/z890rz949

Ponce N, Shimkhada R, Raub A, Daoud A, Nandi A, Richter L, Heymann J (2018) The association of minimum wage change on child nutritional status in LMICs: a quasi-experimental multi-country study. Glob Public Health 13(9):1307–1321. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2017.1359327

Powers ME, Takagishi J (2021) Committee on Adolescence, & Council on Early Childhood Care of adolescent parents and their children Pediatrics147(5):e2021050919. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-050919

Punch S (2001) Negotiating autonomy: children’s use of time and space in rural Bolivia. Routledge, Falmer

Ruiz Casares M, Kilinc D (2021) Legal age for leaving children unsupervised across canada introduction. CWRP, Canadian Child Welfare Research Portal. https://cwrp.ca/publications/legal-age-leaving-children-unsupervised-across-canada-0

Ruiz-Casares M (2009) Between adversity and agency: child and youth-headed households in Namibia. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud 4(3):238–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450120902730188

Ruiz-Casares M, Gentz S, Beatson J (2018a) Children as providers and recipients of support: redefining family among child-headed households in Namibia. In: (eds M. R. T. de Guzman, J. Brown, C. P. Edwards), Parenting From Afar and the Reconfiguration of Family Across Distance (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190265076.003.0011

Ruiz-Casares M, Heymann J (2009) Children home alone unsupervised: modeling parental decisions and associated factors in Botswana, Mexico, and Vietnam. Child Abus Negl 33(5):312–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.010

Ruiz-Casares M, Nazif-Muñoz JI, Iwo R, Oulhote Y (2018b) Nonadult supervision of children in low- and middle-income countries: results from 61 National Population-Based Surveys. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(8):Article 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15081564

Ruiz-Casares M, Rousseau C (2010) Between freedom and fear: children’s views on home alone. Br J Soc Work 40(8):2560–2577. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq067

Rutstein SO, Johnson K (2004) DHS Comparative Reports The DHS wealth index (6). https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-cr6-comparative-reports.cfm

Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Mohammadi R, Ayubi E, Almasi-Hashiani A, Pakzad R, Sullman MJM, Safiri S (2017) Caregiver-related predictors of thermal burn injuries among Iranian children: a case-control study. PLoS ONE 12(2):e0170982. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170982

Schell SL, Morrongiello BA, Pogrebtsova E (2015) Training older siblings to be better supervisors: an RCT evaluating the “Safe Sibs” program. J Pediatr Psychol 40(8):756–767. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsv030

Serpell R (1993) The Significance of Schooling: Life-Journeys in an African Society. Cambridge University Press

Siu G, Batte A, Tibingana B, Otwombe K, Sekiwunga R, Paichadze N (2019) Mothers’ perception of childhood injuries, child supervision and care practices for children 0–5 years in a peri-urban area in Central Uganda; implications for prevention of childhood injuries. Inj Epidemiol 6(1):34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-019-0211-1

Stamatopoulos V (2018) The young carer penalty: exploring the costs of caregiving among a sample of Canadian youth. Child Youth Serv 39(2–3):180–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2018.1491303

StataCorp (2021) Stata Statistical Software (Release 17) [Computer software]. College Station, StataCorp LLC, TX. https://www.stata.com/

Stavropoulou M, Torres A, Samuels F, Solis V, Fernández R (2020) The woman in the house, the man in the street: Young women’s economic empowerment and social norms in Cuba (ODI Report). Overseas Development Institute (ODI), London

Swanson MH (2022) Preventing Unintentional Childhood Injuries in Rural Uganda: Caregiver Perceptions and Promotion of Personal Safety Skills Through Classroom-Based Instruction [Ph.D.]. The University of Alabama at Birmingham. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2709025782/abstract/400A7457DD3C4A61PQ/1

Swanson MH, Johnston A, Rouse JB, Schwebel DC (2018) Sibling supervision: a risk factor for unintentional childhood injury in rural Uganda? Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol 6(4):364. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpp0000252

Tafere Y, Chuta N (2020) Transitions to adulthood in Ethiopia. Policy Studies Institute. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:d68f9ecb-c32f-4fbf-94ed-11031785e0e3/download_file?safe_filename=Transitions%2Bto%2BAdulthood%2Bin%2BEthiopia.pdf&file_format=pdf&type_of_work=Report

Twum-Danso A (2009) Reciprocity, respect and responsibility: the 3Rs underlying parent-child relationships in ghana and the implications for children’s rights. Int J Child’s Rights 17(3):415–432

Twum-Danso Imoh A (2019) Terminating childhood: dissonance and synergy between global children’s rights norms and local discourses about the transition from childhood to adulthood in Ghana. Hum Rights Q 41(1):160–182

Twum-Danso Imoh A (2022) Framing reciprocal obligations within intergenerational relations in Ghana through the lens of the mutuality of duty and dependence. Childhood 29(3):439–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/09075682221103343

Twum-Danso Imoh A, Okyere S (2020) Towards a more holistic understanding of child participation: foregrounding the experiences of children in Ghana and Nigeria. Child Youth Serv Rev 112:104927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104927

UNDP (2021) Human Development Index. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/human-development-index

van der Hoek JJ (2021) Variaties van sibling care in Nederland: Het perspectief van oudste kinderen in Randstedelijke, Urker en Turkse gezinnen [PhD-Thesis - Research and graduation internal]. s.l

Wei H-S, Shih A-T, Chen Y-F, Hong JS (2021) The impact of adolescent parentification on family relationship and civic engagement. J Soc Work 21(6):1413–1432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017320955249

Weisner TS (2017) Socialization for parenthood in sibling caretaking societies. In Parenting across the Life Span. Routledge

Wikle JS, Jensen AC, Hoagland AM (2018) Adolescent caretaking of younger siblings. Soc Sci Res 71:72–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.12.007

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Emmanuelle L. Bolduc, Sol Park, Emilia Gonzalez, and Yinan Yu for assistance with the MICS and DHS databases. This study was funded by Insight Grant 435-2020-0685 by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC - CRSH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: MR-C, JIN-M; Methodology: JIN-M, MR-C, MJ; Formal analysis and investigation: RYF, RI; Writing—original draft preparation: MR-C, RYF, NZ; Writing—review and editing: MR-C, RYF, NZ, RI, MJ, AT-DI, JIN-M; Validation: RYF, JIN-M; Resources: MR-C, MJ, AT-DI, JIN-M; Supervision: MR-C, JIN-M. All authors have revised the paper for important intellectual content and have read and agreed to the present version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the McGill University Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (protocol code A09-E84-09B) on September 28, 2009 and the Ethics Board of Toronto Metropolitan University (protocol code 2022-421) on November 7, 2022.

Informed consent

Participants’ consent was not obtained since this study consisted on secondary analysis of MICS and DHS survey datasets that are publicly available and fully anonymized.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41599_2025_5008_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Table S1. Predictors of child supervised by another child (Incidence Rate Ratio) by mother’s level of edu-cation, unadjusted and adjusted with missing cases.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruiz-Casares, M., Feng, R.Y., Zamani, N. et al. Children supervising children across low- and middle-income countries: the role of mothers’ education. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 694 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05008-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05008-2