Abstract

This study examines the associations of teachers’ personal and job resources (occupational commitment, self-efficacy, collective efficacy, resilience & adaptability) to job engagement. To determine the relationships between constructs, we surveyed 170 Australian teachers during a period of disruption—COVID-19 pandemic. The Job Demands-Resource (JD-R) model provided a theoretical lens for examining teachers’ job-related characteristics (job demands, and job resources) and their influence on job engagement. Results of structural equation modelling show that high teacher self-efficacy is related to a high level of engagement; that teacher’s adaptability and resilience are positively associated with self-efficacy beliefs, as are collective teacher efficacy beliefs. These findings contribute to understanding the importance of personal and job resources in enhancing teachers’ commitment and job engagement. Conclusions include implications for preparing a teaching workforce for future disruptions. This study offers a reminder to policymakers and school leaders of the importance of work climates that nurture collective teacher efficacy, help to support teachers’ adaptability and resilience, which-in-turn, can influence teachers’ sense of self-efficacy when faced with challenging job demands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Teaching is a complex profession that engages strongly with politics of education and culture with teacher’s practice often bound by educational conceptions of efficacy and efficiency (Biesta et al. 2024). In the face of these challenges, the teacher is viewed as an in-school-factor deemed most important for educational success (e.g., Berkovich and Benoliel 2020). The significant disruption and operational challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic impacted teaching staff in Australia (Collie 2023; Miller et al. 2024) and worldwide (Murphy and Devine 2023). Consequently, there is now an increased awareness of teachers’ wellbeing (OECD 2020; Pöysä et al. 2021; Sokal et al 2020; Viac and Fraser 2020; White and McCallum 2021) and a growing international demand for enhancing teachers’ job engagement in an increasingly complex profession (e.g., Berkovich and Bogler 2021; Collie 2021; De Nobile and Bilgin 2022; Fenech et al. 2022). However, there is less known about the contribution of different psychological characteristics beyond self-efficacy in relation to teacher retention (Bardach et al. 2022).

It is well known that increased stress and emotional exhaustion of teachers are associated with teacher burnout (Upadyaya et al. 2022). Current research has seen disruptions impact teaching curriculum and learning, equity issues, resourcing and workloads (Pöysä et al. 2021; Sokal et al. 2020). Teachers’ increasing occupational stress and burnout is a worldwide concern linked to teacher retention and staff shortages (Caudal 2022; Euronews 2022; Morris et al. 2021). The role of teachers’ personal resources has been identified as an important determinant in adaptation to work environments (Xanthopoulou et al. 2007). Substantial challenges continue to trouble the teaching profession, particularly post-COVID-19, given the emotional toll associated with ongoing reforms and staffing shortages (Heffernan et al. 2022).

This study uniquely expands our understanding of the role of teachers’ personal resources as mediators of job engagement during times of heightened disruption (White and McCallum 2021). Personal resources such as resilience, self-efficacy, and adaptability play crucial roles in how teachers manage job demands, leading to higher levels of job engagement and overall wellbeing (Granziera 2022). White and McCallum (2021) found that resilience predicts job satisfaction and wellbeing among teachers, acting as a protective factor against job demands such as stress and burnout. Similarly, occupational commitment, another important personal resource, has been identified as the strongest predictor of actual turnover in employees (Liu and Onwuegbuzie 2012). In disrupted contexts, teachers may utilise these resources to maintain control and manage work demands, allowing them to handle additional tasks or emotional stress caused by disruptions in their teaching routines. Despite extensive research on key constructs associated with teachers’ work (Bingöl et al. 2019; Mérida-López et al. 2020), there is limited understanding of the combined association of personal constructs, with few attempts to unite existing work (Granziera 2022).

To address this objective, the Job Demands-Resources model (JD-R) (Bakker and Demerouti 2007, 2017) served as the theoretical framing for this study. Incorporating and considering personal resources enhances the JD-R model and addresses the research gap. In Skaalvik and Skaalvik’s (2023) study of self and collective efficacy on feelings of belonging and teacher engagement, it was suggested that research “include alternative resources and demands” (p. 1419). In Collie’s (2023) study on teachers’ well-being and turnover, social support appeared central to teachers’ well-being and intentions to leave. Our study contributes to existing knowledge on teachers’ job engagement (e.g., Collie 2023; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2023) by focusing on the combined influence of personal and social resources.

Specifically, we examined the associations between constructs of resilience, adaptability, self-efficacy, and collective-efficacy beliefs as determinants in teacher’s adaptation to disruptions at work and their commitment and engagement to the job. As such we asked: What role do teachers’ personal and job resources play in predicting job commitment and engagement in a disruptive working climate?

Theoretical framework

The JD-R model (Demerouti et al. 2001) has two forms of job-related characteristics: job demands and job resources. Job demands potentially evoke strain and exceed the employee’s capability to adapt. These can be physical, social, or organisational aspects of the job, which may not necessarily be negative but can become the stressors with physiological and psychological costs (Bakker and Demerouti 2017) that teachers experience when trying to meet workplace demands. Personal and collective social-emotional resources can contribute to an individual’s ability to control and influencetheir environment, which in turn can affect teacher motivation and retention (Cao et al. 2020; Hobfoll et al. 2003).

An important inference in the JD-R model is that teachers’ working characteristics can evoke two psychologically different responses. In the first instance, when a teacher’s job is over-demanding and constantly over-taxing, the outcome will lead to teacher exhaustion. This can result in a negative consequence for the organisation and the individual (e.g., absenteeism; Bakker et al. 2003). In the second instance, a teacher’s resources (e.g., self-efficacy, collective efficacy, resilience, occupation commitment) can potentially influence job engagement and positive outcomes (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004).

Job resources are functional in achieving work goals and encouraging personal growth and development (Schaufeli and Taris 2014), while having the potential to negatively predict exhaustion beyond job demands (Bakker and Demerouti 2007). In general, job resources are negatively related to high work pressure and are emotionally demanding, as in heavy workloads or emotionally demanding interactions (e.g., Bakker and Bal 2010). Such resources can help reduce exhaustion or help teachers recover from disruptions and work demands (Dicke et al. 2018). Similarly, high levels of job resources (e.g., high collective teacher efficacy) may consist of social support and feedback that, in turn, can reduce the impact of job demands. Personal resources such as high teacher self-efficacy can also promote teachers’ investment and contributions to the success of the school (Dicke et al. 2018). As such, motivation and exhaustion from high work demands may mediate the relationship between job demands and job resources, thus impacting on job performance (Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Schaufeli and Taris 2014). Bakker and Demerouti (2017) recommend differentiating between job resources (e.g., support from colleagues) and personal resources (e.g., self-efficacy), based on the level of control a teacher can have over their work environment. This study recommended that more attention is needed to fully understand the dual processes in the JD-R model (Bakker and Demerouti 2017; Schaufeli and Taris 2014).

The JD-R constructs are pertinent to studying teachers during periods of disruption and high work pressures, as they help explore the factors affecting teachers’ psychological well-being and job motivation (Bakker and Demerouti 2017). Specifically, we examined teachers’ personal resources (i.e., efficacy beliefs, resilience, and adaptability) to see if these resources act as a buffer or mediator job demands and predict teachers’ job engagement.

Based on our literature review and the theoretical framework presented, we formulated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Collective teacher efficacy can influence the ability to adapt to disruptions and a level of commitment. We expected collective teachers’ efficacy to positively predict occupational commitment and adaptability.

Hypothesis 2: Teachers’ well-being is associated with occupational commitment. We expected teachers’ occupational commitment (as a job resource) to predict their adaptability and resilience (personal resource contributing to wellbeing).

Hypothesis 3. Resilience and adaptability a are associated with teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. We expected that teachers’ adaptability would predict their resilience and self-efficacy beliefs (personal resource contributing to motivation).

Hypothesis 4: Teachers’ well-being can impact their motivation. We expected teachers’ resilience (as a personal resource) to predict their self-efficacy beliefs (as a personal resource contributing to motivation).

Hypothesis 5: Evidence suggests that teachers’ personal resources, job resources, and engagement can be related. We expected teachers’ job resources and personal resources to predict and mediate teacher engagement through teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs (personal resource contributing to motivation).

Teachers’ job engagement

Job engagement is defined as a positive, fulfilling, work-related psychological state combining related dimensions of vigour, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004). Teachers’ occupational engagement plays a critical role in students’ learning outcomes, and teachers’ effectiveness (Yerdelen et al. 2018). Highly engaged teachers are less likely to report intentions to quit (Yerdelen et al. 2018) and are more likely to possess high levels of personal resources and engagement in teaching (Podolsky et al. 2019; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2018). Teachers’ engagement is influenced by personal, environmental, relational and job-related factors. Personal factors, like job expectations and satisfaction play an important role in individual teachers’ affective teaching commitment (Berkovich and Bogler 2021) with job hindrances or obstacles positively related to exhaustion and burnout (Crawford et al. 2010).

The workplace environment is seen to impact teachers’ occupational commitment, particularly regarding, job demands, resources, and leader-related factors (Collie et al. 2020; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2018). Skaalvik and Skaalvik’s (2023) study emphasised the importance of focusing on teachers’ learning goals rather than learning performance, particularly in relation to self-efficacy and job engagement. Relational factors such as the peer relationships are thought to cultivate teachers’ occupational commitment (Berkovich and Bogler 2021). Gu’s (2014) research identified three sets of important relationships: teacher–teacher relations, teacher–principal relations, and teacher–student relations, that foster or hinder teachers’ sense of commitment. Collegial, emotional, and intellectual connections with colleagues are known to positively influence job commitment (Day 2017).

Occupational commitment

Teachers’ occupational commitment is defined as the level of attachment to a career role (Klassen and Chiu 2011). Teacher wellbeing is a growing concern and an international issue (OECD 2020; Viac and Fraser 2020), with an increasing number of teachers reporting high levels of emotional exhaustion, with many showing low levels of engagement and intentions to leave the profession (Australia Productivity Commission 2022; Pöysä et al. 2021; Sokal et al. 2020). Factors that influence teachers’ decisions regarding occupational commitment, include organisational and systemic factors, stress, job satisfaction, resilience, and self-efficacy (Fenech et al. 2022; Olson et al. 2019). There has been however, little research in the recent 10 years on the influence of teachers’ personal resources and occupational commitment on work engagement.

Collective teacher efficacy

Collective efficacy beliefs are defined as the collective belief about the collective capacity to influence and to make a difference (Tschannen-Moran and Barr 2004). Perceived collective efficacy is predicted to effect individual teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2007). Interestingly however, research evidence tends to place the failure to engage on the individual teacher, rather than how the collective operates (e.g., Guglielmi et al. 2016; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2014). It is suggested that perceived collective efficacy may serve as a normative expectation for teachers’ goal attainment (Goddard and Goddard 2001), and influence teachers’ behaviours affected by the shared beliefs (Goddard and Skrla 2006; Tschannen-Moran and Barr 2004). Collective efficacy beliefs are associated with job satisfaction (Yetim and Yetim 2006; Wilson et al. 2025) and job stress (Klassen et al. 2010; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2007), with job satisfaction and motivation influenced by teachers’ interactions with colleagues and students (Klassen 2010). Meihami and Ge’s (2022) study emphasises the importance of work engagement, highlighting self-efficacy as a significant predictor. Donohoo’s (2018) review of literature found that collective efficacy was associated with job satisfaction, commitment to students and a positive attitude to professional development and teaching students with diverse needs. While collective efficacy also positively influences work engagement, its impact is less pronounced compared to self-efficacy and underrepresented in literature and in practice (de Carvalho et al. 2023).

A high degree of perceived collective efficacy act in framing individual teachers’ efficacy beliefs (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2007), impacting teachers’ persistence and resilience (Tschannen-Moran et al. 2014). Individual and collective efficacy are different constructs, yet they influence in reciprocal ways, with engaged, supported teachers, more likely to be satisfied with the job of teaching.

Teacher self-efficacy

Teacher self-efficacy is a teacher’s belief in their ability to organise and execute approaches necessary to achieve desired results (Tschannen-Moran et al. 1998). Having a strong sense of self-efficacy can be related to resilience, particularly in the face of personal setbacks (Bingöl et al. 2019; Yada et al. 2021). Research also indicates a strong association between teacher self-efficacy, self-esteem, and job commitment (Bakker 2011; Chesnut and Burley 2015). Teachers’ self-efficacy has been identified as having a moderating effect on the relationship between teachers’ emotional engagement and commitment to teaching (Mérida-López et al. 2020). In addition, teachers’ self-efficacy can influence motivation for professional learning, specifically if done in collaboration with other teachers (Durksen et al. 2017). Teacher self-efficacy has a significant impact on teachers’ ability to adapt and stay committed (Klassen and Chiu 2011) and is often related to resilience (Yada et al. 2021).

Teacher resilience and adaptability

Resilience refers to the capacity of individuals to navigate the psychological, social, cultural, and physical resources that sustain well-being and extend to the ability to navigate major crisis or significant adversities (Collie et al. 2020; Gu and Day 2013; Peixoto et al. 2020). Adaptability is defined as the capacity to effectively cope and recover from the inherent novelty, change and uncertainty from everyday challenges and setbacks (Collie et al. 2020; Collie and Martin 2016) and to regulate psycho-behavioural functions (Martin et al. 2012). Existing literature has linked teachers’ adaptability (Martin et al. 2012), and resilience (Rees et al. 2015; Sheridan et al. 2022) with improved job commitment and wellbeing (Almlund et al. 2011). Resilience was found to be significantly related to teachers’ intent to leave the profession (Bowles and Arnup 2016). Teachers’ adaptability and coping strategies have an important relationship with occupational commitment (Collie et al. 2020; Collie and Martin 2016; Smith et al., 2025). Adaptability is negatively associated with disengagement and associated with organisational commitment (Collie and Martin 2016). Therefore, understanding the association between self-efficacy, resilience, and adaptability can help support and retain teachers in the profession (e.g., Klassen et al. 2013; McGraw et al. 2019).

Methods

Ethics approval was received from the Social Science Human Ethics Committee (No. 2019/351) of the lead author’s institution for survey distribution via social (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) and professional networks (e.g., Australian Council for Health, Physical Education and Recreation [ACHPER]) in Australia. ACHPER’s potential distribution reach included: 4135 Facebook followers, and 1557 Twitter followers. Recruitment procedures included forwarding a request, information, and a direct anonymous survey link to complete and/or forward on to networks/memberships.

Participants and procedures

Data were collected using an online survey platform, Qualtrics. Most participants (42%) accessed the survey link via Facebook with 35% from friends and colleagues. The data collection period extended from 2020–2022 with most respondents completing the survey in 2021. The focus was on capturing responses during COVID-19 disruptions and the ongoing challenges that persisted in 2022 for teachers.

Teacher respondents (n = 170) worked across different levels of Australian education (early years, primary [elementary], secondary) in two systems (government and non-government schooling). Participants (82% female) ranged in age from 21 to 56+ with most (40%) between 35 and 45 years old (see Table 1—demographics).

Measures

The survey comprised of the following six sections: demographics, occupational commitment, efficacy beliefs, teacher engagement, resilience and adaptability. To ensure content validity, the instrument was distributed initially to members of the research team and a small sample of teachers (n = 15), resulting in minor modifications to wording and the question organisation, before distribution. The following measures were used in the survey to understand the combined associations (relationships) between constructs. This was crucial for understanding how personal resources influence teachers’ working conditions, particularly when job demands are causing strain and exhaustion, exceeding the teacher’s adaptive capacity while still staying engaged.

Occupational commitment

We used Klassen and Chiu’s (2011) 10-item measure, 9-point scale (Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree) to measure the intent to quit and teachers’ commitment to stay in the job e.g., “I like this career too well to give it up” and “I am disappointed that I ever entered the teaching profession.” Hackett et al.’s (2001) study established the construct validity of commitment and withdrawal variables (i.e., quitting intentions).

Teacher self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was originally defined from the perspective of locus of control (e.g., Rotter 1996) and Bandura’s (1997) self-efficacy theory characterises the antecedents of self-efficacy, including mastery experience, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and the use of physiological cues. We used a 6-item shortform (based on the work of Tschannen-Moran et al. (1998), Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (2001), with two relevant items from each of three self-efficacy sub-scales (instructional strategies, classroom management & student engagement) measuring level of confidence in, for example, to the ability to “get students to believe they can do well in schoolwork.” This approach aligns with self-efficacy theory and has been used in other studies with high factor loading studies (e.g., Klassen et al. 2009) which have established construct and convergent validity and adequate reliability for this measure with reliability coefficients ranging from 0.79 to 94.

Collective teacher efficacy

Collective teacher efficacy reflects individual teachers’ perspectives about their school’s collective capabilities to influence student achievement (Goddard and Goddard 2001; Tschannen-Moran and Barr 2004). Judgement of efficacy in a group endeavour tends to be socially embedded, not socially separate from the group’s beliefs (Bandura 1997). The survey included the 12-item collective teacher efficacy scale (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy 2001) with a 9-point response option. The scale consisted of two factors—instructional strategies e.g., “teachers produce meaningful student learning” and student discipline “teachers respond to defiant students.” Tschannen-Moran and Barr’s (2004) study demonstrated high reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.97.

Teacher engagement

Klassen et al. (2013) developed the Engaged Teacher Scale to reflect the content and context unique to characteristics of teachers not otherwise represented in Bakker’s (2011) Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. We used the Engaged Teacher Scale consisting of 16 items (7-point Likert scale from Never—Always) across four engagement subscales: emotional, cognitive, social with students, and social with colleagues (e.g., “At school, I connect well with my colleagues” and “I love teaching”; Klassen et al. 2013). Item loadings of the factors ranged from 0.66 to 0.85, with Cronbach alpha coefficients factors of 0.89, 0.85, 0.85, and 0.84, respectively.

Teacher resilience

Teachers’ resilience was measured using 26 items from the Multidimensional Teachers’ Resilience Scale with a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree; Mansfield and Wosnitza 2015). The resilience scale was reliable in recent studies by Peixoto et al. (2018, 2020) with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93. The scale consisted of four dimensions: emotional, (5 items e.g., “What I feel upset or angry at school I can manage to stay calm”); social, (5 items e.g., “I am good at building relationships in new school environments”) ; motivational, (11 items e.g., “I like challenges in my work”); and professional (6 items e.g., “I can balance my role as a teacher with other dimensions in my life.”)

Teacher adaptability

The Teacher Adaptability Scale (Collie and Martin 2016) consists of domain-specific items comprised of four elements: (1) response to novelty, change, variability and/or uncertainty; (2) cognitive, behavioural or affect functions; (3) regulation, adjustment, revisions, or a new form of access; and (4) as a constructive purpose or outcomes. We used the full measure (9 items; 7-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree) which included statements such as “At work, I am able to revise the way I think about a new situation to help me through it.” Martin et al. (2012, 2013) established a conceptual case for the plausibility as a single factor for adaptability with Cronbach alpha of 0.90 (ee Table 2 for evidence of validity and reliability in the current study).

Analytical strategy

Survey data were exported analysed using SPSS (Version 26) and Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 2017). The preliminary analyses involved looking for outliers and missing values and examining reliability coefficients, means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis for the predictor and outcomes variables (see Table 2). The slight non-normality of the data was dealt with using the MLR estimator, which is appropriate for non-normality (Muthén and Muthén 2017).

To provide measurement support and to obtain latent correlations among factors, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using structural equation modelling (SEM)—Robust maximum likelihood (Muthén and Muthén 2017). The full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimator was used to handle missing data (≤1%). Several fit indices with conventional cut-off values were used to evaluate the model fit including chi-square statistics, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = < 0.05; Steiger and Lind 1980), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR < 0.05; Jöreskog and Sörbom 1979), Comparative Fit Index (CFI >0.90; Bentler 1990), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI >0.90; Tucker and Lewis 1973), and the Weighted Root Mean Square Residual (WRMR >0.90; Muthén and Muthén 1998–2017). Indices used have been proven through simulation and actual use of data to perform reasonably well with categorical and ordinal model estimation (Beauducel and Herzberg 2006).

The sample of 170 participants (collected during COVID-19 shutdowns) met the common guideline of 10 to 20 participants per parameter in the model (Wolf et al. 2013). With a total of seven parameters (six predictor variables and one outcome variable) and using the higher end (20:1 = 140), our sample size of 170 exceeds these recommendations. This is supported by calculating the statistical power of the study. SemPower analysis in R (Moshagen and Bader 2024) reports that a sample size of 170 with six predictor variables and one outcome variable (df = 6) for detecting RMSEA = 0.05 and ∝ = 05 has 80.89% implied power (adequate for testing the current hypotheses).

Results

Table 3 shows the correlations of specified constructs.

The highest positive correlation was found between teacher engagement and resilience (r = 0.80), while adaptability and collective teacher efficacy (r = 0.22) was the lowest. Collective teacher beliefs were positively associated with teacher commitment (r = 0.23), resilience (r = 0.26), adaptability (r = 0.22), self-efficacy (r = 0.38), and engagement (r = 0.52). Occupational commitment was positively associated with resilience (r = 0.41), adaptability (r = 0.36), self-efficacy (r = 0.41), and engagement (r = 0.57). Adaptability was positively associated with resilience (r = 0.64), self-efficacy (r = 0.46), and engagement (r = 0.70). In addition, engagement was positively associated with teacher self-efficacy beliefs.

Structural equation model analysis yielded a good model fit: χ2 (270, 1019) = 1836.79, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.04, and CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93 and SRMR = 0.04, the same as CFA given the same number of parameters were involved in both models. No model re-specification was performed because the fit indices suggested that the measurement model was consistent with the data. Also, the modification indices suggested are very low.

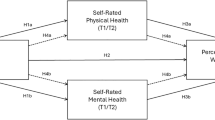

Results showed that teacher self-efficacy was positively associated with teacher engagement (β = 0.80; p < 0.001; large effect) whilst adaptability was positively associated with both resilience (β = 0.56; p < 0.001; large effect) and teacher self-efficacy (β = 0.26; p < 0.05; small effect). In addition, resilience was positively associated with teacher self-efficacy (β = 0.53; p < 0.001; large effect) and collective teacher efficacy was positively associated with occupational commitments (β = 0.23; p < 0.01; small effect) and adaptability (β = 0.21; p < 0.05; small effect). Lastly, occupational commitment was positively associated with adaptability (β = 0.34; p < 0.01; medium effect) and resilience (β = 0.25; p < 0.01; small) (see Table 4).

The relationships between constructs are shown in Fig. 1, providing evidence to support the hypothesised relationships. Collective teacher efficacy (CTE) was positively related to both occupational commitment (COM) and adaptability (ADP) (Hypothesis 1). While the effect size is small, the association is significant. Occupational commitment (COM) was positively related to adaptability (ADP) and resilience (RESL) (Hypothesis 2). The medium effect size between COM and ADP indicates a moderate relationship. However, the effect size between COM and RESL was small. Adaptability (ADP) and resilience (RESL) were positively related to teacher self-efficacy (TSE) (Hypothesis 4). Adaptability (ADP) had a large effect on resilience (RESL) but a small effect on teacher self-efficacy (TSE). Adaptability (ADP) also had a strong relationship to Resilience (RESL) (Hypothesis 3). Together, these constructs point to a positive relationship between teacher self-efficacy (TSE) and engaged teachers (ETS) (Hypothesis 5) (see Fig. 1).

We tested an alternative model where the order of job resources and personal resources was reversed. The model fit statistics were the same because both models, hypothesised and alternate, were fully saturated. There were also eight significant direct effects in the alternate model, but much smaller in magnitude than in our hypothesised model. The higher beta values generated in our hypothesised model provide evidence that our model better explains the relationships among the constructs.

Discussion

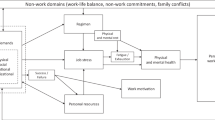

In response to our research question, we generated statistical evidence based on the hypothesised relationships among the constructs. Informed by the JD-R model (Bakker and Demerouti 2007), this study found positive associations between occupational commitment, teacher self-efficacy, collective teacher efficacy, adaptability and resilience to teachers’ job engagement. The relationships among the constructs of interest were situated within the broader picture of personal, environmental, relationship and job-related factors pertinent to teaching (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2 broadly groups job demand factors—(e.g., COVID-19 disruptions, work pressures) and job resources—(e.g., role autonomy, social/professional support). The figure further illustrates the important influence of teachers’ personal resources and their associations and that teachers’ social resources (e.g., collective efficacy beliefs) can predict teachers’ self-efficacy and subsequent job engagement. It is the combination of personal resources and collective teacher efficacy that may help to minimise the impact of teachers’ job demands. Research indicates that perceived collective teacher efficacy may serve as a normative expectation for teachers’ goal attainment (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2007), which can influence teachers’ behaviours (Tschannen-Moran et al. 2014). The collective shared belief (as a job resource) may subsequently influence teachers’ commitment to teaching.

The influence of collective beliefs on teachers’ occupational commitment, adaptability, resilience, and subsequent self-efficacy beliefs was unique to this study (Hypothesis 2). Although some associations are relatively small, our findings highlight the important role of a teacher’s collective efficacy as a job resource, both in mediating occupational commitment and providing social support for teachers that assist them in being able to adapt and respond to work challenges. This is important for achieving work goals and encouraging personal growth and development (Schaufeli and Taris 2014). This modelling is well supported by research, which identified the relationships between individual constructs—i.e., shared collective beliefs affects an individual teachers’ self-efficacy (e.g., Berebitsky and Salloum 2017), teachers’ self-efficacy affects occupational commitment (e.g., Mérida-López et al. 2020) and high teacher self-efficacy is a predictor of resilience (e.g., Yada et al. 2021), with adaptability impacting occupational commitment (Collie and Martin 2016). High self-efficacy can encourage both a personal investment (engagement) and an occupational commitment in a school (Dicke et al. 2018).

Regarding teachers’ adaptability and resilience, both constructs are closely linked (Rees et al. 2015) with a large effect and are associated with job commitment (Almlund et al. 2011). Adaptability is considered a protective factor of resilience (Collie and Martin 2016); being adaptable in teaching may mediate a teacher’s capacity for resilience. A teacher with high levels of resilience and self-efficacy can better manage job demands such as stress, workloads, and major disruptions as in the case of COVID-19. They also tend to have higher levels of job satisfaction (e.g., Olson et al. 2019) (Hypothesis 3), which can influence commitment and intentions to quit (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004). Resilience and self-efficacy were positively associated (Hypothesis 4) in this study, suggesting that this association can predict teachers’ job engagement.

Moreover, this study found that all constructs had a positive association with teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, with all the constructs combined seeming to mediate a teachers’ self-efficacy and predict job engagement. Although the associations ranged from small to large effects, this study talks to previous research findings of engaged teachers being more likely to maximise their personal resources (e.g., resilience, self-efficacy) and transfer their engagement to their workplace (Podolsky et al. 2019; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2018). Yet, a disruptive teaching climate (i.e., increased job demands)—with both everyday challenges and crisis situations (COVID-19) can create job stresses that potentially impact a teacher’s capacity to remain engaged and committed to the job of teaching (Jeon et al. 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic impacted teachers and learners worldwide, disrupting teaching and learning and resulting in increased stress and workloads on teachers (Pöysä et al. 2021; White and McCallum 2021). Personal resources, such as high self-efficacy beliefs, can act as a buffer to job demands and is a predictor for teachers’ job engagement (see Fig. 2).

Personal (Berkovich and Bogler 2021), environmental (Collie et al. 2020), and relational factors (Gu 2014) in the workplace can either support or hinder teachers’ work engagement. Aspects such as organisational change, leadership, emotional labour, workloads, and other work pressures are considered job demands (e.g., Collie et al. 2020). They act as either a positive or negative influence (Bakker 2011), particularly as teachers struggle to adapt to change and remain resilient with high self-efficacy whilst experiencing ever-increasing and constant work pressures. This impacts teachers’ capacity to stay committed to teaching. To foster job engagement, especially during periods of disruptions, current literature and our findings point to fostering personal resources, such as sustained positive relationships and communications, while focusing on the collective efficacy of their school community (Murphy and Devine 2023).

In this study, a range of work-related constructs were found to influence a teacher’s self-efficacy—a finding supported by research (e.g., Mérida-López et al. 2020). In general, job resources with social support and feedback can help to reduce the influence of work demands, providing opportunities for teachers to adapt better, build their sense of teacher self-efficacy, and help sustain professional commitment (Klassen 2010). The role of collective teacher efficacy is underrepresented in literature and in practice (Anderson et al. 2023). Our study provides empirical support for the importance of nurturing shared beliefs that influence behaviour and provide collective power for individual teachers to achieve desired goals in schools and their careers (Goddard et al. 2004). Having supportive colleagues, particularly during times of social disruption, helps teachers to stay committed and responsive (i.e., adaptive) to work demands.

Higher occupational commitment promotes a greater capacity to adapt to the work demands encountered by teachers. Being adaptable is considered a protective factor for coping with everyday stress and remaining resilient—an important personal resource for teachers’ wellbeing (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2018) and an important factor for teachers’ job engagement (Collie et al. 2020). Teachers who can respond and adapt to job-related challenges are more likely to be resilient (Sheridan et al. 2022), better able to cope with everyday stresses (Collie and Martin 2016) and enjoy greater wellbeing (Martin et al. 2012). Being adaptable in teaching provides teachers with greater teacher agency and capacity (Day 2018). Moreover, adaptable teachers tend to have more effective coping strategies, which is seen to be an important factor impacting commitment to the profession (Collie and Martin 2016).

Findings suggest that an increase in occupational commitment may only occur for a teacher if their personal and collective resources were positively related, acting to mediate the associations between job demands (Garrick et al. 2014). Collective beliefs and effective leadership can be particularly important when nurturing staff commitment (Berebitsky and Salloum 2017). Teaching requires coping with the everyday and ongoing job stressors while maintaining work commitment to meet job demands. Building collective teacher efficacy can help teachers remain engaged with the job; as engaged teachers are more likely to maximise their personal resources and transfer their engagement to their workplace (Podolsky et al. 2019).

This exploration of the relationships between work-related demands and resources sought to advance the understanding of teachers’ job engagement during times of intense social disruption. To our knowledge, this study is the first to model relationships among a teacher’s resilience, adaptability, occupational commitment, self-efficacy and collective efficacy with job engagement. Our findings add to the growing evidence that personal resources are important for teachers’ job engagement.

Limitations and future research

Our results provide a foundation for exploring key work-related constructs during a time of heighted teaching disruption. The main limitation is in having to rely on social networks/media for recruitment due to restrictions to teachers in schools during COVID-19. With a larger sample size, more sophisticated analyses can be conducted. However, this study did include a wide national cross section of teachers in Australia during a time of long shutdown periods, online teaching, and limited resources (internet, ICT support, students with a range of learning needs). Disruptions from COVID-19 made teaching more complex and stressful yet provided a unique picture of the extent to which teachers experience job stress and demands.

There are methodological limitations, due to the limitation of sample size, as we did not include covariates as part of the model. We did provide the basis for future studies, where the role of covariates can be further studied (e.g., gender, geographical location, age) using our model. Since we gathered cross-sectional data over a period when the impacts of the pandemic fluctuated (e.g., varied lockdown experiences) causality cannot be assumed. As we used convenience sampling, it is difficult to claim generalisable across teaching populations. Studies of larger and international samples are currently underway providing a more sophisticated sampling design to approximate a better representation of the findings.

Our study used self-report measures which are well-supported in the literature. Further evidence can be gathered using qualitative methods (e.g., interviews) to provide greater nuance in our understanding of the relationships amongst these constructs at different levels within a school structure (e.g., individual, leadership, system level). It is desirable for future research to include qualitative methods to help validate our model with insights into teachers’ experiences and meaning making during teaching disruptions.

Implications for practice

Our study of Australian teachers found that those with a higher sense of self-efficacy were more likely to be engaged in their jobs – a relationship that has been found in other countries (e.g., Durksen et al. 2017). Schools and leaders should invest in work conditions that can help boost teachers’ beliefs through induction, training, and support. Teachers who adapt well to challenges are more likely to be resilient and supportive colleagues can play a crucial role in fostering a positive workplace. Collective support and shared beliefs are essential, especially during times of disruption, in helping teachers manage stress and support their students’ learning effectively. School leaders can encourage and actively develop a culture of collective efficacy, which in turn, can support teachers and their students to learn more effectively during disruptions.

Principals and system leaders can capitalise on teachers as a ’human resource.’ In practical terms this mean that schools and leaders have a responsibility to invest in building teachers’ self-efficacy and collective efficacy (e.g., professional learning, social support) which in turn can help enhance teachers’ engagement. It is important to consider what resources the job offers individual teachers and how those resources can help to reduce the impact of job demands and the associated costs. This is becoming increasingly important if we are to retain teachers and prevent further teacher burnout, particularly during times of disruptions and in contexts that are highly charged (i.e., hard to staff schools). School leaders need to consider the value of the collective via both informal and formal networks of support for teachers (Sheridan et al. 2022). Networks can provide opportunities for collective social bonding which can help individual teachers to better manage the daily stresses in teaching.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of both collective teacher efficacy and teacher’s self-efficacy on job engagement. Having a positive school culture where colleagues feel empowered and supported and are prepared to support others can foster a sense of community and nurture teachers’ occupational commitment (Collie 2023; Smith et al. 2025). Key personal characteristics are important considerations when striving for successful work lives (Bardach et al. 2022) and serve as fundamental aspects of human performance and development (Heckman and Kautz 2013). In this study, we acknowledge the importance of personal resources (resilience, adaptability and self-efficacy) in relation to teachers’ welfare in disruptive times can add to the retention efforts during a worldwide teacher shortage crisis.

Overall, the research offers insights into the relationship between key constructs and how they matter in supporting teachers’ job engagement and in better managing job demands and stress caused by teaching disruptions.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and Supplementary Information files (data output) is available on request from readers subject to ethics conditions. The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Human Research.

References

Australia Productivity Commission (2022) Review of the national school reform agreement: interim report, productivity commission, Canberra. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/school-agreement/report

Almlund M, Duckworth AL, Heckman J, Kautz T (2011) Chapter 1—Personality psychology and economics. In: Hanushek EA, Machin S, Woessmann L (eds) Handbook of the economics of education, vol 4. Elsevier, pp 1–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53444-6.00001-8

Anderson CM, Summers KH, Kopatich RD, Dwyer WB (2023) Collective teacher efficacy and its enabling conditions: a proposed framework for influencing collective efficacy in schools. AERA Open 9(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584231175060

Bardach L, Klassen RM, Perry NE (2022) Teachers’ psychological characteristics: do they matter for teacher effectiveness, teachers’ well-being, retention, and interpersonal relations? An integrative review. Educ Psychol Rev 34(1):259–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09614-9

Bakker AB (2011) An evidence-based model of work engagement. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 20(4):265–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411414534

Bakker AB, Bal PM (2010) Weekly work engagement and performance: a study among starting teachers. J Occup Organ Psychol 83(1):189–206. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X402596

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2007) The job demands‐resources model: state of the art. J Manag Psychol 22(3):309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2017) Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J Occup Health Psychol 22(3):273. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

Bakker AB, Demerouti E, De Boer E, Schaufeli WB (2003) Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. J Vocat Behav 62:341–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00030-1

Bandura A (1997) Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Macmillan

Beauducel A, Herzberg PY (2006) On the performance of maximum likelihood versus means and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation in CFA. Struct Equ Model 13:186–203. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1302_2

Bentler PM (1990) Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull 107(2):238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Berkovich I, Benoliel P (2020) Marketing teacher quality: critical discourse analysis of OECD documents on effective teaching and TALIS. Crit Stud Educ 61(4):496–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2018.1521338

Berkovich I, Bogler R (2021) Conceptualising the mediating paths linking effective school leadership to teachers’ organisational commitment. Educ Manag Adm Leadersh 49(3):410–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220907321

Berebitsky D, Salloum SJ (2017) The relationship between collective efficacy and teachers’ social networks in urban middle schools. AERA Open 3(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858417743927

Biesta G(2024) Taking Education Seriously: The Ongoing Challenge. Educ. Theory 74(3):434–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12646

Bingöl YT, Batık MV, Hoşoğlu R, Kodaz AF (2019) Psychological resilience and positivity as predictors of self-efficacy. Asian J Educ Train 5:63–69. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.522.2019.51.63.69

Bowles T, Arnup JL (2016) Early career teachers' resilience and positive adaptive change capabilities. Aust Educ Res, 43(2), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-015-0192-1

Caudal S (2022) Australian secondary schools and the teacher crisis: understanding teacher shortages and attrition. Educ Soc 40(2):23–39. https://doi.org/10.7459/es/40.2.03

Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, Zheng J (2020) The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res 287:112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Chesnut SR, Burley H (2015) Self-efficacy as a predictor of commitment to the teaching profession: a meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev 15:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.001

Collie RJ (2023) Teacher well-being and turnover intentions: investigating the roles of job resources and job demands. Br J Educ Psychol 93(3):712–726. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12587

Collie RJ (2021) A multilevel examination of teachers’ occupational commitment: the roles of job resources and disruptive student behavior. Soc Psychol Educ 24(2):387–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1832063

Collie RJ, Guay F, Martin AJ, Caldecott-Davis K, Granziera H (2020) Examining the unique roles of adaptability and buoyancy in teachers’ work-related outcomes. Teach Teach 26(3-4):350–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1832063

Collie RJ, Martin AJ (2016) Adaptability: an important capacity for effective teachers. Educ Pract Theory 38:27–39. https://doi.org/10.7459/ept/38.1.03

Crawford ER, LePine JA, Rich BL (2010) Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: a theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J Appl Psychol 95(5):834–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019364

Day C (2017) Teachers’ worlds and work: understanding complexity, building quality, 1st edn. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315170091

Day C (2018) Professional identity matters: agency, emotions, and resilience. In: Schutz PA, Hong J, Cross Francis D (eds) Research on teacher identity: mapping challenges and innovations. Springer International Publishing, pp 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93836-3_6

de Carvalho AL, Durksen TL, Beswick K (2023) Developing collective teacher efficacy in mathematics through professional learning. Theory Pract, 62(3), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2023.2226553

Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB (2001) The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol 86(3):499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

De Nobile J, Bilgin AA (2022) A structural model to explain influences of organisational communication on the organisational commitment of primary school staff. Educ Sci 12(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060395

Dicke T, Stebner F, Linninger C, Kunter M, Leutner D (2018) A longitudinal study of teachers’ occupational well-being: applying the job demands-resources model. J Occup Health Psychol 23(2):262–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000070

Donohoo J (2018) Collective teacher efficacy research: productive patterns of behaviour and other positive consequences. J Educ Change 19(3):323–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-018-9319-2

Durksen TL, Klassen RM, Daniels LM (2017) Motivation and collaboration: the keys to a developmental framework for teachers’ professional learning. Teach Teach Educ 67:53–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.011

Euronews (2022) Teacher shortages worry countries across Europe. https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/11/30/teacher-shortages-worry-countries-across-europe

Fenech M, Wong S, Boyd W (2022) Attracting, retaining, and sustaining early childhood teachers: an ecological conceptualisation of workforce issues and future research directions. Aust Educ Res 49:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-020-00424-6

Garrick A, Mak AS, Cathcart S, Winwood PC, Bakker AB, Lushington K (2014) Psychosocial safety climate moderating the effects of daily job demands and recovery on fatigue and work engagement. J Occup Organ Psychol 87(4):694–714. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12069

Goddard RD, Goddard YL (2001) A multilevel analysis of the relationship between teacher and collective efficacy in urban schools. Teach Teach Educ 17(7):807–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00032-4

Goddard R. D, Hoy W. K, Hoy A. W(2004) Collective Efficacy Beliefs: Theoretical Developments, Empirical Evidence, and Future Directions. Educ. Res 33(3):3–13. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x033003003

Goddard RD, Skrla L (2006) The influence of school social composition on teachers’ collective efficacy beliefs. Educ Adm Q 42(2):216–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X05285984

Granziera H (2022) Teachers’ personal resources: what do we know and where do we go? A scoping review through the lens of job demands-resources theory. J Posit Psychol Wellbeing 6(2):1695–1718. http://184.168.115.16/index.php/jppw/article/view/11779

Gu Q (2014) The role of relational resilience in teachers’ career-long commitment and effectiveness. Teach Teach 20(5):502–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.937961

Gu Q, Day C (2013) Challenges to teacher resilience: conditions count. Br Educ Res J 39(1):22–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2011.623152

Guglielmi D, Bruni I, Simbula S, Fraccaroli F, Depolo M (2016) What drives teacher engagement: a study of different age cohorts. Eur J Psychol Educ 31:323–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-015-0263-8

Hackett RD, Lapierre LM, Hausdorf PA (2001) Understanding the links between work commitment constructs. J Vocat Behav, 58(3), 392–413. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1776

Heckman JJ, Kautz T (2013) Fostering and measuring skills: interventions that improve character and cognition. No. w19656. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w19656

Heffernan A, Bright D, Kim M, Longmuir F, Magyar B (2022) ‘I cannot sustain the workload and the emotional toll’: reasons behind Australian teachers’ intentions to leave the profession. Aust J Educ 66(2):196–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/00049441221086654

Hobfoll SE, Johnson RJ, Ennis N, Jackson AP (2003) Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. J Pers Soc Psychol 84(3):632–643

Jeon H, Diamond L, McCartney C, Kwon K (2022) Early childhood special education teachers’ job burnout and psychological stress. Early Educ Dev 33(8):1364–1382. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2021.1965395

Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D (1979) Advances in factor analysis and structural equation models. Abt Books

Klassen RM (2010) Teacher stress: the mediating role of collective efficacy beliefs. J Educ Res 103(5):342–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670903383069

Klassen RM, Bong M, Usher EL, Chong WH, Huan VS, Wong IYF, Georgiou T (2009) Exploring the validity of a teachers’ self-efficacy scale in five countries. Contemp Educ Psychol 34(1):67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2008.08.001

Klassen RM, Chiu MM (2011) The occupational commitment and intention to quit of practicing and pre-service teachers: influence of self-efficacy, job stress, and teaching context. Contemp Educ Psychol 36(2):114–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.01.002

Klassen RM, Usher EL, Bong M (2010) Teachers’ collective efficacy, job satisfaction, and job stress in cross-cultural context. J Exp Educ 78(4):464–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220970903292975

Klassen RM, Yerdelen S, Durksen TL (2013) Measuring teacher engagement: development of the Engaged Teachers Scale (ETS). Frontline Learn Res 1(2):33-52. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v1i2.44

Liu S, Onwuegbuzie AJ (2012) Chinese teachers’ work stress and their turnover intention. Int J Educ Res 53:160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.03.006

Mansfield CF, Wosnitza M (2015) Teacher resilience questionnaire—version 1.5. Murdoch University

Martin AJ, Nejad H, Colmar S, Liem GAD (2012) Adaptability: conceptual and empirical perspectives on responses to change, novelty and uncertainty. Aust J Guid Couns 22(1):58–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2012.8

Martin AJ, Nejad HG, Colmar S, Liem GAD (2013) Adaptability: how students’ responses to uncertainty and novelty predict their academic and non-academic outcomes. J Educ Psychol 105(3):728. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032794

McGraw A, McDonough S (2019) Thinking dispositions as a resource for resilience in the gritty reality of learning to teach. Aust Educ Res, 46(4), 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00345-z

Meihami H, Ge L (2022) Enhancing Chinese EFL teachers’ work engagement: the role of self and collective efficacy. Front Psychol 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.941943

Mérida-López S, Extremera N, Sánchez-Álvarez N (2020) The interactive effects of personal resources on teachers’ work engagement and withdrawal intentions: a structural equation modelling approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(7):2170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072170

Miller A, Fray L, Gore J (2024) Was COVID-19 an unexpected catalyst for more equitable learning outcomes? A comparative analysis after two years of disrupted schooling in Australian primary schools. Aust Educ Res 51(2):587–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00614-y

Morris R, See BH, Gorard S (2021) Teacher shortage in England: new evidence for understanding and addressing current challenges. Impact J Chart Coll Teach 11:64–67. https://my.chartered.college/impact_article/teacher-shortage-in-england-new-evidence-for-understanding-and-addressing-current-challenges/

Moshagen M, Bader M (2024) semPower: general power analysis for structural equation models. Behav Res 56:2901–2922. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-023-02254-7

Murphy G, Devine D (2023) Sensemaking in and for times of crisis and change: Irish primary school principals and the Covid-19 pandemic. Sch Leadersh Manag 43(2):125–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2022.2164267

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2017) Mplus user’s guide, 8th edn. Muthén & Muthén

Muthén BO, Muthén LK, Asparouhov T (2017) Regression and mediation analysis using Mplus. Muthén & Muthén

OECD (2020) The teachers’ well-being conceptual framework: contributions from TALIS 2018. Teaching in focus, 30. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/86d1635c-en

Olson RE, McKenzie J, Mills KA, Patulny R, Bellocchi A, Caristo F (2019) Gendered emotion management and teacher outcomes in secondary school teaching: a review. Teach Teach Educ 80:128–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.01.010

Peixoto F, José CS, Pipa J, Wosnitza M, Mansfield C (2020) The multidimensional teachers’ resilience scale: validation for Portuguese teachers. J Psychoeduc Assess 38(3):402–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/073428291983685

Peixoto F, Wosnitza M, Pipa J, Morgan M, Cefai C (2018) A multidimensional view on pre-service teacher resilience in Germany, Ireland, Malta and Portugal. In: Wosnitza M, Peixoto F, Beltman S, Mansfield CF (eds) Resilience in education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76690-4_5

Podolsky A, Kini T, Darling-Hammond L, Bishop J (2019) Strategies for attracting and retaining educators: what does the evidence say? Educ Policy Anal Arch 27:38–38. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.27.3722

Pöysä S, Pakarinen E, Lerkkanen M-K (2021) Patterns of teachers’ occupational well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: relations to experiences of exhaustion, recovery, and interactional styles of teaching. Front Educ 6:699785. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.699785

Rees CS, Breen LJ, Cusack L, Hegney D (2015) Understanding individual resilience in the workplace: the international collaboration of workforce resilience model. Front Psychol, 6, 73. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00073

Rotter JB (1966) Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol Monogr, 80, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976

Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB (2004) Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi‐sample study. J Organ Behav Int J Ind Occup Organ Psychol Behav 25(3):293–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248

Schaufeli WB, Taris TW (2014) A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In: Bauer GF, Hämmig O (eds) Bridging occupational, organizational and public health: a transdisciplinary approach. Springer, pp 43–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5640-3_4

Sheridan L, Andersen P, Patulny R, McKenzie J, Kinghorn G, Middleton R (2022) Early career teachers’ adaptability and resilience in the socio-relational context of Australian schools. Int J Educ Res 115:102051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2022.10205

Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S (2007) Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. J Educ Psychol 99(3):611–625. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.611

Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S (2014) Teacher self-efficacy and perceived autonomy: relations with teacher engagement, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion. Psychol Rep 114(1):68–77. https://doi.org/10.2466/14.02.PR0.114k14w0

Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S (2018) Job demands and job resources as predictors of teacher motivation and well-being. Soc Psychol Educ 21(5):1251–1275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9464-8

Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S (2023) Collective teacher culture and school goal structure: associations with teacher self-efficacy and engagement. Soc Psychol Educ, 26(4):945–969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09778-y

Smith K, Sheridan L, Duursma E, Alonzo D (2025) Teachers’ emotional labour: the joys, demands, and constraints. Teach Teach 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2025.2466560

Sokal L, Trudel LE, Babb J (2020) Canadian teachers’ attitudes toward change, efficacy, and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Educ Res Open 1:100016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100016

Steiger JH, Lind JC (1980) Statistically based tests for the number of common factors. Paper presented at the annual Spring Meeting of the Psychometric Society in Iowa City

Tschannen-Moran M, Barr M (2004) Fostering student learning: the relationship of collective teacher efficacy and student achievement. Leadersh Policy Sch 3(3):189–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760490503706

Tschannen-Moran M, Hoy AW (2001) Teacher efficacy: capturing an elusive construct. Teach Teach Educ 17(7):783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Tschannen-Moran M, Hoy AW, Hoy WK (1998) Teacher efficacy: its meaning and measure. Rev Educ Res 68(2):202–248. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543068002202

Tschannen-Moran M, Salloum SJ, Goddard RD (2014) Context matters: the influence of collective beliefs and shared norms. In: Fives H, Gill MG (eds) International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs, 1st edn. Routledge, pp 301–316. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203108437

Tucker LR, Lewis C (1973) A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 38:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF0229117

Upadyaya K, Pressley T, Westphal A, Kalinowski E, Hoferichter CJ, Vock M (2022) K-teachers’ stress and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Front Psychol 13:1–29. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.920326

Viac C, Fraser P (2020) Teachers’ well-being: a framework for data collection and analysis. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 213. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/c36fc9d3-en

White MA, McCallum F (2021) Crisis or catalyst? Examining COVID-19’s implications for wellbeing and resilience education. In: White MA, McCallum F (eds) Wellbeing and resilience education: COVID-19 and its impact on education, 1st edn. Routledge, pp 1–17. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003134190

Wilson L, Sheridan L, Alonzo D, Middelton R (2025) The Personal and Collective Resources of Nurses and the Relationship to Job Commitment and Work Engagement. J Adv Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.16804

Wolf E, Harrington K, Clark S, Miller M (2013) Sample size requirements for structural equation models: an evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ Psychol Meas 73:913–934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164413495237

Xanthopoulou D, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB (2007) The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int J Stress Manag 14:121–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121

Yada A, Björn PM, Savolainen P, Kyttälä M, Aro M, Savolainen H (2021) Pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy in implementing inclusive practices and resilience in Finland. Teach Teach Educ 105:103398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103398

Yerdelen S, Durksen T, Klassen RM (2018) An international validation of the engaged teacher scale. Teachers and Teaching, 24(6), 673–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2018.1457024

Yetim N, Yetim U (2006) The cultural orientations of entrepreneurs and employees’ job satisfaction: the Turkish small and medium sized enterprises (SMES) case. Soc Indic Res 77:257–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-4851-x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisations—all research team were involved in this. Methodology—Sheridan, Durksen and Alonzo contributed to this aspect. Validation and analysis—Sheridan and Alonzo. Data collection—all of the team were involved in this. Data curation—Sheridan. Writing original draft—all researchers. Writing, review and editing—Sheridan, Durksen, Gao and Nguyen.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Social Science Human Ethics Committee of the University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia (Approval Number: 2019/351). All research was performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. The approval was granted on December 18, 2019, with amendments on the 7 June 2020, prior to the commencement of the research. The scope of the approval covered all aspects of the study, including participant recruitment, data collection, and data analysis.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Social Science Human Ethics Committee reviewed and approved the study protocol, informed consent forms, and data management plans to ensure the protection of participants’ rights and privacy. For any further information or queries regarding the ethical aspects of this study, please contact the Social Science Human Ethics Committee at the University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia, email rso-ethics@uow.edu.au.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheridan, L., Alonzo, D., Nguyen, H.T.M. et al. Teachers’ job engagement: the personal and job resources that matter. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 896 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05009-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05009-1