Abstract

Amid global efforts to achieve carbon neutrality and promote circular economy, the new energy vehicle (NEV) supply chain has emerged as a critical focus of industrial policy optimization. This study develops a Stackelberg game model where battery manufacturers act as leaders and NEV manufacturers as followers to investigate optimal decision-making strategies in the supply chain. We examine four distinct scenarios: no government subsidy (n-strategy), government subsidy for battery manufacturers (b-strategy), government subsidy for vehicle manufacturers (m-strategy), and dual subsidy (bm-strategy). Our analysis reveals several key findings: (1) any form of government subsidy enhances both power battery research and development (R&D) levels and waste recovery rates compared to the non-subsidy scenario; (2) from the perspective of consumer surplus and social welfare, the optimal subsidy strategy follows the hierarchy: bm ≻ m ≻ b ≻ n; (3) higher subsidy levels do not necessarily translate into increased government revenue. Under both high and low regulatory cost scenarios, the dual subsidy (bm) and vehicle manufacturer subsidy (m) strategies generate optimal government net income when subsidy values are appropriately calibrated. These findings provide valuable insights for policymakers in designing effective subsidy mechanisms for the NEV industry, ultimately contributing to the optimization of economic and environmental benefits in this rapidly evolving sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, escalating global environmental concerns and “dual-carbon” goals have posed unprecedented challenges to the energy industry (Zhu et al. 2024). New energy vehicles (NEVs), as crucial contributors to transportation-sector emission reduction, are experiencing remarkable growth opportunities, with China emerging as the global leader in NEV production and sales (Su et al. 2023). However, the industry faces several critical challenges: limited driving range due to low battery energy density, technological gaps compared to traditional vehicles, supply-demand imbalances in lithium resources causing cost pressures (Della Bella et al. 2023; Zhu et al. 2024), and inadequate battery recycling systems. These challenges collectively impede the industry’s advancement.

In response, China has implemented comprehensive policy support, including tax incentives, R&D subsidies, and various promotional measures (Kou et al. 2023; Song and Wen 2023). These initiatives have effectively propelled China’s NEV industry to global leadership. As the market matures, policy focus has shifted from direct purchase subsidies to sustainable development measures since 2023 (Yi et al. 2024). Current support emphasizes charging infrastructure development, technological innovation, and consumer incentives. The government has intensified infrastructure investment through public-private partnerships and regional subsidies, implemented preferential parking policies (Zhu et al. 2024), and strengthened R&D support for battery technology through specialized funding and tax benefits (Zhao et al. 2024). Innovation centers have been established to facilitate industry-academia collaboration, accelerating technological advancement (Chai et al. 2023; Sieg et al. 2023).

These policy adjustments aim to guide the NEV industry from policy-dependent to market-driven growth (Su et al. 2023), establishing a foundation for sustainable development (Chai et al. 2023). Understanding subsidy impacts is therefore crucial. This study examines how various subsidy strategies affect NEV development, seeking optimal policies that balance industrial growth, innovation, environmental protection, and economic benefits. Specifically, we address four key questions:

-

(1)

How do government subsidies influence battery R&D levels and used battery recycling rates? What are the pre- and post-subsidy changes in these metrics?

-

(2)

How do different subsidy strategies affect firm profits, R&D investments, and recycling rates? What are the relationships among these variables?

-

(3)

What are the differential impacts of subsidy strategies on consumer surplus and social welfare? How do subsidy intensity, R&D preferences, and environmental awareness influence these outcomes?

-

(4)

Which subsidy type maximizes regulatory net benefits? Is there an optimal subsidy level rather than a “more is better” approach?

This study employs a Stackelberg game model to analyze optimal solutions under various subsidy scenarios. The Stackelberg framework is particularly appropriate as it captures the sequential decision-making process where the government acts as the leader in setting subsidy policies, followed by firms’ strategic responses in R&D and recycling decisions, and finally consumer reactions (Von Stackelberg, 1952). The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant literature; Section 3 presents the research framework and model; Section 4 analyzes consumer surplus and social welfare; Section 5 discusses findings, implications, and limitations. Computational details and optimal solutions are provided in Appendices 1 and 2. Our findings offer theoretical guidance for policy formulation and corporate strategy development in R&D and recycling.

Literature Review

Literature on government subsidies and NEV supply chain innovation

Existing research on government subsidies in the NEV industry primarily follows three main streams. The first stream focuses on subsidy effectiveness at the enterprise level. Xu et al. (2020) and Jiang and Xu (2023) examined how R&D subsidies influence enterprise innovation capabilities, revealing that subsidy effectiveness varies with firm size and technological capacity (Jiang and Xu 2023; X. L. Xu and Chen, 2020). Song and Wen (2023) further found that financial subsidies have a non-linear impact on technological innovation, suggesting the existence of an optimal subsidy level (Song and Wen 2023). However, these enterprise-level studies neglect the broader supply chain impacts of subsidy policies.

The second research stream examines subsidy impacts from a supply chain perspective. Li et al. (2023) analyzed pricing and warranty strategies under government subsidies in a closed-loop supply chain (Jinhong Li et al. 2023), while Chen et al. (2023) investigated how subsidy thresholds affect supply chain coordination (Chen and Fan, 2023). These studies highlight the importance of considering supply chain relationships in subsidy design, though they often overlook the interaction between different types of subsidies.

The third stream investigates policy mechanism design. Yi et al. (2024) compared dual credit policies with traditional subsidies, finding that market-based mechanisms can be more effective in certain contexts (Yi et al. 2024). Zhao et al. (2024) analyzed policy combinations, demonstrating that different subsidy instruments have varying effects across market segments (Zhao et al. 2024). While these studies provide valuable insights into policy design, they typically lack consideration of the dynamic interaction between R&D and recycling incentives.

Literature on battery recycling and environmental performance

Research on battery recycling and environmental performance can be categorized into three main areas. The first area addresses technical and economic feasibility. Kamath et al. (2023) developed comprehensive models for end-of-life battery management (Kamath et al. 2023), while Reinhart et al. (2023) analyzed the economic viability of different recycling technologies (Reinhart et al. 2023). These studies establish the technical foundation for recycling strategies but often neglect policy and market influences.

The second research area focuses on environmental impact assessment. Fan et al. (2023) conducted life cycle assessments of battery reuse (Fan et al. 2023), while Zhang et al. (2023) analyzed greenhouse gas emissions throughout the battery lifecycle. Su et al. (2023) evaluated the broader environmental benefits of NEVs in China (Su et al. 2023). These environmental analyses provide crucial insights but typically treat recycling decisions in isolation from other supply chain activities.

The third area examines supply chain integration in recycling operations. Della Bella et al. (2023) investigated how recycling affects material supply-demand balance (Della Bella et al. 2023), while Tang et al. (2024) developed models for closed-loop supply chain optimization (Tang et al. 2024). Saeedi et al. (2024) proposed frameworks for sustainable battery supply chains (Saeedi et al. 2024). Though these studies consider supply chain relationships, they often overlook how R&D investments and subsidy policies affect recycling efficiency.

Research contributions

This study addresses several critical gaps in existing literature. Firstly, current research tends to examine R&D subsidies and recycling incentives separately, failing to capture their interdependence. Our study develops an integrated framework that considers both aspects simultaneously, providing insights into their dynamic interaction.

Secondly, while existing studies have examined supply chain relationships, they rarely consider how different subsidy combinations affect coordination between manufacturers and recyclers. Our research explicitly analyzes optimal subsidy allocation across the supply chain, addressing this limitation.

Thirdly, previous studies typically focus on single performance metrics (either economic or environmental). Our study introduces a comprehensive evaluation framework that simultaneously considers environmental benefits, economic efficiency, and social welfare, providing a more complete assessment of policy effectiveness.

These contributions advance both theoretical understanding and practical policy design. By integrating previously disparate research streams, our study offers new insights into how government subsidies can effectively promote technological innovation while ensuring environmental sustainability in the NEV industry.

Problem description and model assumptions

Consider a two-level supply chain consisting of a NEV power battery manufacturer (B) and a NEV manufacturer (M). The battery manufacturer handles the R&D and production of power batteries, while the vehicle manufacturer is responsible for selling the vehicles and recycling used batteries from consumers. Since the power battery system accounts for 30% to 40% of a vehicle’s R&D costs (Gong and Hansen 2023; Wang et al. 2023), the importance of battery R&D for NEVs is clear. Firms like SAIC (Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation) and BAIC (Beijing Automotive Industry Holding Co., Ltd.) compete to collaborate with battery R&D and manufacturing companies like CATL (Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited) to reduce costs (Liu and Kokko 2013). Consequently, battery manufacturers hold significant influence and leadership in the market (Gong and Hansen 2023; Hu et al. 2022). Based on this, we construct a Stackelberg game model with power battery manufacturers as channel leaders and NEV manufacturers as follows (Abate et al. 2024; Niromandfam et al. 2020).

Decision-making behavior of supply chain subjects

NEV power battery manufacturer (B)

Power battery manufacturers use the subscript B to indicate the main decision-making power battery wholesale price w and power battery R&D levele. Battery manufacturers sell batteries to NEV manufacturers at wholesale prices w, and through R&D to improve the battery life and safety performance of power batteries to attract consumers to buy. R&D cost \(C\left(e\right)={\lambda }_{1}{e}^{2}\), where \({\lambda }_{1}\) represents the R&D cost coefficient of the power battery.

NEV manufacturers (M)

The NEV manufacturer uses the subscript M to represent it, and the main decisions are the retail price p of the vehicle and the recycling rate τ of the used power battery. The NEV manufacturer sells the product to consumers at the price p, The waste power battery is recycled from consumers at unit cost A, and the transfer price of each waste battery is b. Recovery cost \(C\left(\tau \right)={\lambda }_{2}{\tau }^{2}\), where \({\lambda }_{2}\) represents the sustainable investment cost coefficient of power battery recovery.

Government (G)

In order to effectively incentivize battery manufacturers and NEV manufacturers to conduct R&D on battery life and improve recycling rates, the government has adopted three strategies: Subsidize battery manufacturers (b-strategy), subsidize NEV retailers (m-strategy), and subsidize both battery manufacturers and NEV retailers (bm-strategy). Among them, \(s\) represents the level of government subsidies. The amount of government subsidies is closely related to the R&D level of power batteries, the recycling rate of used batteries and the market size.

Market demand for NEVs

The market demand for NEVs is also affected by product prices, battery life and waste battery recycling. On the basis of the demand function of (X. Xu et al. 2023), the demand function is set according to the specific situation of the system studied in this paper. This paper sets the demand function as \(D=m-p+{k}_{1}e+{k}_{2}\tau\) Among them, m is the potential market size, \({k}_{1}\) is the consumer R&D level preference coefficient, and \({k}_{2}\) is the consumer’s green environmental protection awareness. The relevant symbols and parameter descriptions are shown in Table 1.

Decision-making model without government subsidies (n-strategy)

When the government does not subsidize the supply chain, the profit functions of car manufacturers and battery manufacturers are as follows:

Among them, \({\lambda }_{1}{e}^{2}\) represents the R&D investment cost of the power battery, and \({\lambda }_{2}{\tau }^{2}\) represents the cost incurred by the manufacturer to recycle the used power battery.

In the Stackelberg game, both battery manufacturers and NEV manufacturers aim at maximizing their own profits. The battery manufacturer first decides the wholesale battery price w and R&D effort level e. After the decision is made to determine the product sales price p and the waste product recovery rate τ, according to the reverse induction method, the reaction functions of p* and τ* about w and e under this model can be obtained as follows:

Proposition 1: When \({\lambda }_{2} > \frac{{(b-A+{k}_{2})}^{2}}{2}\), there is a unique optimal solution \({(p}^{* },\,{\tau }^{* })\) for NEV manufacturers; \(\frac{{\partial p}^{* }}{\partial w} > 0\), \(\frac{{\partial \tau }^{* }}{\partial w} < 0\), \(\frac{{\partial \tau }^{* }}{\partial e} > 0\).

For NEV manufacturers, an increase in the wholesale price \(w\) of power batteries leads to a higher retail price for NEVs to maintain profits. This price hike reduces market demand, as consumers purchase fewer NEVs, which in turn lowers demand in the recycling market and decreases the recovery rate of power batteries. Conversely, when the R&D level of battery manufacturers improves, more consumers are attracted to buy NEVs, boosting market demand and subsequently increasing the recovery rate of power batteries.

Proposition 2: When \(2{\lambda }_{1}(4{\lambda }_{2}-{(b-A+{k}_{2})}^{2})-{k}_{1}^{2}{\lambda }_{2} > 0\), there is an optimal solution \(({w}^{* },{e}^{* })\), and the optimal profit \(({\pi }_{B}^{* },{\pi }_{M}^{* })\).

Corollary 1: \(\frac{{\partial w}^{* }}{\partial {k}_{1}} > 0\), \(\frac{{\partial e}^{* }}{\partial {k}_{1}} > 0\), \(\frac{{\partial p}^{* }}{\partial {k}_{1}} > 0\), \(\frac{{\partial \pi }_{B}^{* }}{\partial {k}_{1}} > 0\); \(\frac{{\partial \tau }^{* }}{\partial {k}_{2}} > 0\), \(\frac{{\partial p}^{* }}{\partial {k}_{2}} > 0\), \(\frac{\partial {\pi }_{M}^{* }}{\partial {k}_{2}} > 0\).

It can be seen from Corollary 1 that (a) when consumer demand for battery R&D increases, battery manufacturers will enhance their efforts to meet diverse needs, such as improving battery life and safety performance; (b) At the initial stage of power battery R&D, a large amount of R & D funds needs to be invested, so the wholesale price of power batteries and the retail price of NEVs will rise, and the profits of battery manufacturers will further increase, so as to encourage battery manufacturers to increase R&D investment; (c) The use of renewable energy in NEVs makes a great contribution to reducing exhaust emissions and improving environmental quality. When consumers’ awareness of environmental protection increases, consumers will choose to buy NEVs instead of fuel vehicles, and the profits of NEV manufacturers will further increase. Consumers will pay more attention to the environmental protection behavior of enterprises when purchasing products. Therefore, NEV manufacturers will increase the recycling rate of power batteries to meet consumers’ environmental protection needs.

Consider the decision-making model under government subsidies

In order to encourage power battery manufacturers of NEVs to increase R&D of power batteries and NEV manufacturers to actively recycle waste power batteries, this study considers three subsidy strategies to subsidize the supply chain of NEVs: (a) to subsidize power battery manufacturers, (b) to subsidize NEV manufacturers, and (c) to subsidize battery manufacturers and NEV manufacturers.

Subsidy strategy of power battery manufacturers (b-Strategy)

Currently, NEV users are concerned about range, safety performance, and charging times. This requires battery companies to innovate in battery design, production processes, and integrated systems to better align with consumer expectations. The R&D costs for power batteries are significant, with large manufacturers investing 6% to 12% of their operating income. To encourage active R&D participation, the government provides subsidies based on R&D levels. In this context, the profit function of NEV manufacturers is shown in formula (5).

Proposition 3: under this model, \(\frac{{\partial \pi }_{B}^{* }}{\partial s} > 0\), \(\frac{{\partial e}^{* }}{\partial s} > 0\), \(\frac{{\partial w}^{* }}{\partial s} > 0\).

Compared with the no subsidy strategy, when the government only subsidizes battery manufacturers, the battery R&D level will be improved. The increase \(({e}_{B}^{* }-{e}_{N}^{* })\) is related to the government’s subsidy strength s and consumers’ preference for R&D level \({k}_{1}\) positive correlation with R&D cost coefficient \({\lambda }_{1}\) is negatively correlated. The government subsidizes battery manufacturers according to their market size and R&D strength, which can stimulate them to increase R&D efforts and help them create NEV batteries with stronger endurance and better safety performance. However, even with government subsidies, battery manufacturers will formulate R&D strategies based on consumer demand and battery R&D costs. When consumers in the market have higher requirements for battery capacity, battery manufacturers will consider increasing R&D efforts; When the R&D cost is too high, enterprises will also consider postponing R&D. With the increase of government subsidies, the level of battery R&D has increased, which has led to the expansion of consumer market demand and further affected the increase of power battery wholesale prices. At this time, the profits of power battery manufacturers have further expanded.

As the external driving force of power battery manufacturers, government subsidies are conducive to improving the R&D level of power batteries. Larger subsidies and higher consumer preference coefficients significantly boost innovation, improving battery endurance and safety. It indicates a synergistic effect between government subsidies and consumer preferences. Therefore, the government should focus R&D subsidies in regions where NEVs are popular and maximize these subsidies for greater impact.

Subsidy strategy for NEV manufacturers (m-Strategy)

Lithium resources are crucial for power batteries and energy storage. Factors like the pandemic and rising raw material costs have led to fluctuations in the NEV market. Thus, the potential for battery recycling is significant, though challenges exist due to varying conditions of used batteries, complex processes, and limited consumer experience. To address these issues, enterprises should establish regional recycling centers and industries to meet the demand for precious metals. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China stated in the 2019 standards for comprehensive utilization of waste power batteries that recycling enterprises should ensure valuable metals are recovered effectively, with lithium recovery rates not falling below 85%. Therefore, the government should provide subsidies to recycling enterprises to enhance the recycling rate of waste batteries, thereby improving lithium resource integration. At this point, the profits for power battery manufacturers are as follows (6).

By comparing the decisions of NEV manufacturers under the two strategies of m and n, the following conclusions are drawn:

Proposition 4: under this model \(\frac{\partial {\tau }^{* }}{\partial s} > 0,\frac{{\partial p}^{* }}{\partial s} > 0,\frac{{\partial \pi }_{M}^{m}}{\partial s} > 0\).

When the government subsidizes the recycling rate of NEV manufacturers, it boosts their investment in waste battery recycling and utilization. The increase \(({\tau }_{m}^{* }-{\tau }_{n}^{* })\) is positively correlated with government subsidies \(s\) and consumers’ green preferences \({k}_{2}\), and negatively correlated with the recovery cost coefficient \({\lambda }_{2}\). Recycling involves many industrial chains, such as lithium salt remanufacture and cell reuse. Government subsidies encourage NEV manufacturers to enhance their recycling efforts, thereby increasing profits. As government subsidies and battery recovery rates rise, market demand for NEVs expands, impacting their prices. Consequently, NEV manufacturers’ profits grow due to increased revenues from both recycling and market demand expansion.

Simultaneous subsidy strategy for battery manufacturers and NEV manufacturers (bm-Strategy)

As a key component of the green industry, the power battery and NEV sectors have significant growth potential in the global push for “carbon peak and carbon neutrality”. Consumer demand for NEVs has surged, alongside increasing environmental awareness. Government policies effectively promote the production, R&D, recycling, and utilization of power batteries. In this section, we consider simultaneous subsidies for battery and NEV manufacturers, with the profit function as follows:

By solving the optimal decision under this strategy, the following conclusions are obtained through comparison.

Proposition 5: Profit comparison of power battery manufacturers: \({\pi }_{B}^{{bm}} > {\pi }_{B}^{m} > {{\pi }_{B}^{b} > \pi }_{B}^{n}\); Profit comparison of NEV manufacturers: \({\pi }_{M}^{{bm}} > {\pi }_{M}^{m} > {{\pi }_{M}^{b} > \pi }_{M}^{n}\); Comparison of battery R&D level: \({e}^{{bm}} > {e}^{b} > {e}^{m} > {e}^{n}\); Comparison of recovery rate of waste batteries: \({\tau }^{{bm}} > {\tau }^{m} > {\tau }^{b} > {\tau }^{n}\).

It reveals the effects of different government subsidy modes on the level of power battery R&D, the recycling rate of used batteries, the profits of power battery manufacturers, and the profits of NEV manufacturers. When the government adopts a subsidy strategy, both for power battery R&D and used battery recycling, the effect is better than that of no subsidy. It means that government subsidies can effectively incentivize battery manufacturers and NEV manufacturers to increase investment in battery R&D and waste battery recycling. Regardless of the specific government subsidies, they will boost the profitability of battery makers and automakers, as well as the overall profitability of the entire NEV supply chain. Even if some companies do not receive direct government subsidies, they will be positively influenced by other subsidized companies in the industry to improve their own R&D or used battery recycling rates. Especially when the government subsidizes battery manufacturers alone, this approach not only directly promotes the progress and innovation of battery technology, but also indirectly creates synergies for NEV manufacturers and promotes the overall development of the industry. Of the three subsidy strategies-subsidizing only the battery manufacturer, subsidizing only the NEV manufacturer, and subsidizing both at the same time (i.e., the dual-subsidy strategy, or bm-strategy)-the dual-subsidy strategy has proven to be the most effective. In this way, the government is able to promote technological innovation while ensuring good interaction between the upstream and downstream of the industry chain, further optimizing the allocation of resources and achieving more efficient market operation and development. Therefore, for countries wishing to accelerate the growth of the NEV industry and enhance international competitiveness, it is particularly important to implement a comprehensive dual-subsidy strategy.

Proposition 6: \(\frac{{\partial e}_{{bm}}^{* }}{\partial s} > 0,\frac{{\partial \tau }_{{bm}}^{* }}{\partial s} > 0\)、\(\frac{{\partial \pi }_{B}^{{bm}}}{\partial s} > 0,\frac{{\partial \pi }_{M}^{{bm}}}{\partial s} > 0\); \(\frac{{\partial e}_{{bm}}^{* }}{\partial {k}_{1}} > 0,\frac{{\partial w}_{{bm}}^{* }}{\partial {k}_{1}} > 0,\frac{{\partial \pi }_{B}^{{bm}}}{\partial {k}_{1}} > 0\); \(\frac{{\partial e}_{{bm}}^{* }}{\partial {\lambda }_{1}} < 0,\,\frac{{\partial \pi }_{B}^{{bm}}}{\partial {\lambda }_{1}} < 0\); \(\frac{{\partial w}_{{bm}}^{* }}{\partial {\lambda }_{1}} > 0\); \(\frac{{\partial \tau }_{{bm}}^{* }}{\partial {k}_{2}} > 0,\frac{{\partial p}_{{bm}}^{* }}{\partial {k}_{2}} > 0,\frac{{\partial \pi }_{M}^{{bm}}}{\partial {k}_{2}} > 0;\frac{\,{\partial \tau }_{{bm}}^{* }}{\partial {\lambda }_{2}} < 0,\frac{\partial {\pi }_{M}^{{bm}}}{\partial {\lambda }_{2}} < 0\); \(\frac{{\partial p}_{{bm}}^{* }}{\partial {\lambda }_{2}} > 0\)

Firstly, government subsidies undoubtedly help to improve the R&D level of batteries. The stronger the subsidy, the stronger the consumer’s preference for R&D. Government R&D subsidies can more effectively stimulate the innovation drive of battery manufacturers, thus significantly improving the R&D and innovation capacity of power batteries and increasing the profits of battery manufacturers. At the same time, government subsidies can also help increase the recycling rate of used products. There is a stacking effect between such subsidies and consumers’ green preferences: when subsidies increase, consumers’ green consumption tendency also increases, which makes NEV manufacturers perform better in recycling, which in turn increases their profitability. In addition, by encouraging higher recycling rates, it not only reduces environmental pollution, but also promotes effective recycling of resources, laying a solid foundation for sustainable development. Secondly, the profits of power battery manufacturers and NEV manufacturers decrease as the R&D cost coefficient \({\lambda }_{1}\) increases, and increase as the recycling cost coefficient \({\lambda }_{2}\) decreases, respectively. This is because when a firm’s operating costs rise, in order to maintain or improve its competitiveness, it needs to invest more in R&D activities, resulting in a decline in its own profits in the short term. Under such circumstances, firms may adopt the strategy of adjusting wholesale and retail prices upwards to balance the cost pressure caused by increased R&D investment. However, this may not be conducive to market expansion and technological advancement in the long run. At the same time, high R&D costs may also prompt companies to reduce their R&D intensity and recovery rate to a certain extent, in order to seek the optimal balance between cost control and profitability. Therefore, when formulating relevant policies, the government should fully consider the impact of these factors and reduce the burden on enterprises by optimizing the subsidy structure and other means to support their sustainable and healthy development.

Analysis of consumer surplus, total social welfare and net benefits of government regulation

Consumer surplus and total social welfare

This part uses numerical simulation to study the difference between consumer surplus (CS) and total social welfare (SW) generated by different government subsidy strategies. CS refers to the cumulative net utility obtained by consumers who purchase NEVs. The expression of CS is as follows: \((i\!\!\in [n,b,m,{bm}])\):

The total SW includes the sum of CS and profits of both sides of the supply chain, as follows:

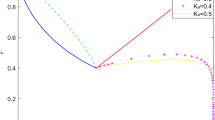

Set \(c=2,{k}_{1}=0.4,{k}_{2}=0.5\) draw the changing trends of CS and total SW with the government subsidy s under various modes, and consider \({k}_{1},{k}_{2}\), and Figs. 1 to 4 are obtained.

As can be seen in Fig. 1, as the government subsidy \(s\) increases, the CS (i.e., the net benefit that the consumer receives from the purchase) gradually increases regardless of the subsidy model adopted. This suggests that regardless of the specific subsidy strategy adopted by the government, the subsidy can effectively enhance the level of battery R&D and the recycling rate of used products. The government’s increased subsidy not only enhances consumers’ purchasing utility, but also expands the consumer market and attracts more consumers to make purchases, thus contributing to the realization of a larger CS. Further observation reveals that there are significant differences in the growth rate of the CS curve under different government subsidy modes. Specifically, when the government adopts a dual-subsidy strategy (subsidizing both battery manufacturers and NEV manufacturers), CS grows most rapidly. This means that the dual-subsidy strategy is more favorable from the perspective of consumer benefits than subsidizing battery manufacturers or NEV manufacturers alone. Through this strategy, the government is able to promote technological innovation while ensuring the healthy development of the entire industry chain, and ultimately allowing consumers to enjoy higher quality products and services. The order of consumer preference for different subsidy strategies is: \({bm}\succ m\succ b\succ n\). This ordering reflects consumers’ pursuit of maximizing comprehensive benefits, and they tend to support policies that can both reduce product costs and improve product quality. Therefore, when formulating relevant policies, the government should give full consideration to how to maximize consumer benefits through an effective subsidy mechanism, while promoting the sustainable development and technological progress of the industry. By doing so, it will not only enhance the competitiveness of enterprises, but also better meet the market demand and promote the forward development of the entire NEV industry.

From Fig. 2, it can be confirmed that as the government subsidy \(s\) increases, CS under the dual-subsidy strategy (bm-strategy) grows significantly faster than that under the strategy of subsidizing only the NEV manufacturers (m-strategy). When the amount of subsidy provided by the government is the same, the higher the consumer preference for R&D level \({k}_{1}\) and green awareness \({k}_{2}\), the more significant the difference between the bm-strategy and the strategy of subsidizing only the NEV manufacturers. This suggests that under the same subsidy conditions, if consumers pay more attention to the technological innovation and environmental performance of the product, then the dual-subsidy strategy will better satisfy their needs and lead to higher CS. Figure 2 further shows consumers’ preference for the government to adopt a dual-subsidy strategy. This preference is not only reflected in faster-growing CS, but also in consumers’ sensitivity to how the subsidy policy affects their welfare. Specifically, increased government subsidies, higher consumer preference for higher levels of R&D, and increased consumer green awareness all positively affect CS. Together, these factors make the dual-subsidy strategy more effective in increasing consumer purchasing utility, expanding market demand, and ultimately realizing greater CS.

From Figs. 3 and 4, it can be seen that the pattern of change in total SW is similar to the trend of change in CS. The total SW under different strategies is in the following order from high to low: \({bm}\succ m\succ b\succ n\). Obviously, the total SW under the dual-subsidy strategy and the strategy of subsidizing only NEV manufacturers is much higher than that under the strategy of no subsidy and subsidizing only battery manufacturers. By improving product innovation and environmental performance, companies are better able to meet market demand, thereby promoting the sustainable development of the industry as a whole. In addition, the effective use of government subsidies can further promote the optimal allocation of resources, reduce the R&D and recycling costs of enterprises, so that more funds can be invested in technological innovation and market expansion, thereby achieving higher economic and social benefits. To Summarize, the increase of consumers’ R&D preference and green preference can not only improve the overall SW, but also enhance consumers’ utility, which has a positive effect on the economic value of supply chain members, which is conducive to the realization of the overall SW.

Analysis of net benefits of government regulation

As a means of environmental regulation, government subsidies for NEV supply chains must consider regulatory costs to maximize net benefits. While specific cases like (Jian Li and Lai 2023) provide valuable insights into regulatory cost structures, we extend this approach to develop a generalized framework for analyzing the relationship between regulatory costs and subsidy effectiveness across different market contexts(Niromandfam et al. 2020). In this paper, the cost of government regulation is set as follows:

Among them, the first item is the actual expenditure of government subsidies, which is called variable subsidy expenditure cost; The second item is the regulatory cost paid by the government for implementing subsidized regulation, which is a fixed cost and only related to the degree of subsidy (\(\eta\) is the government supervision cost coefficient). Therefore, the net income realized by the government in implementing the subsidy mechanism can be expressed as follows:

As can be seen from Figs. 5 and 6, when the government’s regulatory costs are taken into account, there is a significant difference between the government’s net revenue through environmental regulation and other socio-economic indicators. When the coefficient of the government’s regulatory cost is low, the government’s net revenues under the subsidy-only NEV manufacturer (m-strategy) and dual-subsidy strategy (bm-strategy) will first increase and then gradually decrease after reaching a certain threshold; while the government’s net revenues under the subsidy-only battery manufacturer (b-strategy) will slowly increase. For the government, a balanced subsidy value \({s}^{* }\) should be chosen to maximize its net revenue. When the government’s regulatory cost coefficient is high, the maximum net revenue under all three subsidy strategies is lower than the maximum value at low regulatory cost. As the government subsidy increases, the net revenue from government regulation under the m-strategy and bm-strategy increases gradually and then begins to decline after reaching a certain point, while the net revenue from government regulation under the b-strategy declines slowly as the government subsidy increases. Therefore, a larger government subsidy is not better. The government should consider the cost of regulation comprehensively and choose the appropriate amount of subsidy according to different subsidy strategies.

In order to achieve policy objectives more effectively, the government needs to conduct a careful cost-benefit analysis when formulating subsidy policies. This not only includes an assessment of the expected economic benefits under different subsidy strategies, but also takes into account the impact of regulatory costs on overall net revenue. By choosing the optimal level of subsidy, the government can promote technological innovation and improve environmental performance while ensuring the effective use of financial resources, thereby maximizing social and economic benefits. In addition, the government should also regularly assess the effectiveness of the policy and make timely adjustments to the subsidy strategy in the light of market and technological developments, so as to ensure that it continues to promote the healthy development of the industry.

Conclusions

This study employs a Stackelberg game model to examine how government subsidy policies influence R&D levels and recycling decisions in the NEV supply chain. Four distinct subsidy scenarios are analyzed: no government subsidy (n), battery manufacturer subsidy only (b), NEV manufacturer subsidy only (m), and dual subsidies to both manufacturers (bm). Through this model, we evaluate the effectiveness of each subsidy strategy by examining three key metrics: consumer surplus, social welfare, and net regulatory revenue. Based on our analysis, several significant conclusions are obtained as follows.

Firstly, our analysis reveals that without government subsidies, battery recycling rates exhibit an inverse relationship with wholesale prices but a positive correlation with R&D advancement. The introduction of any subsidy mechanism proves beneficial, leading to enhanced battery R&D levels and improved recycling rates of used batteries. This demonstrates that government intervention, regardless of the specific subsidy strategy employed, generates positive outcomes throughout the NEV supply chain.

Secondly, in scenarios with government subsidies, both battery R&D levels and used battery recycling rates demonstrate positive correlations with subsidy magnitude and consumer preference intensity. Notably, even under single-party subsidy policies, non-subsidized firms show increased innovation efforts and profit growth proportional to subsidy levels. This indicates that government subsidies, whether directed at battery manufacturers or NEV manufacturers, create positive spillover effects benefiting the non-subsidized supply chain partners.

Thirdly, our analysis of consumer surplus and social welfare reveals a clear hierarchy among subsidy strategies. The dual-subsidy approach targeting both manufacturers delivers the most favorable outcomes, followed by exclusive NEV manufacturer subsidies, then battery manufacturer subsidies, with the no-subsidy scenario showing the least beneficial results. Both consumer surplus and total social welfare demonstrate positive correlations with government subsidy levels, consumer preference for battery R&D advancement, and environmental consciousness. The dual-subsidy strategy generates the most rapid improvements in these metrics, with the NEV manufacturer-only subsidy approach showing the second-best performance. Ultimately, the implementation of dual subsidies maximizes both consumer utility and overall social welfare.

Fourthly, for the government, it is not the case that a larger subsidy is better. Both the dual-subsidy strategy (bm) and the subsidy-only strategy (m) generate the highest net government revenues at both high and low regulatory costs, but the optimal value of the subsidy needs to be found. Above or below this optimal value will affect the government’s net revenue. In the high regulatory cost case, the government’s net revenue is lower than that in the low regulatory cost case.

To summarize, the government should take various factors into consideration and choose an appropriate subsidy strategy and subsidy amount to maximize consumer surplus, social welfare and government net income. By optimizing the subsidy policy, the government can not only promote technological innovation and environmental performance, but also promote the healthy and sustainable development of the entire new energy vehicle industry.

Managerial and policy implications

Based on our findings, we propose three key practical and policy implications. First, governments should implement a dual-subsidy strategy supporting both battery and NEV manufacturers, with regular adjustments based on market dynamics to maximize social welfare. Second, the regulatory framework should be streamlined to improve efficiency and reduce administrative costs, ensuring optimal allocation of subsidy resources through transparent oversight mechanisms. Third, the policy focus should extend beyond direct subsidies to create a comprehensive ecosystem that encourages technological innovation and green consumption. This includes providing R&D incentives, particularly in battery technology advancement, while simultaneously promoting environmental awareness and sustainable consumption patterns through consumer education and green certification programs.

Although this study provides insights for exploring the application of government subsidy mechanisms in NEV supply chains, it still has certain limitations. Future research should examine vertical supply chain dynamics under different subsidy schemes, analyze horizontal competition among multiple NEV manufacturers, and investigate subsidy impacts across various innovation types (technological, managerial, and business model) to provide more comprehensive guidance for policy formulation.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Abate AG, Riccardi R, & Ruiz C (2024) Dynamic tariff-based demand response in retail electricity market under uncertainty. OR Spectrum 1–35

Chai Q, Sun M, Lai K-h, Xiao Z (2023) The effects of government subsidies and environmental regulation on remanufacturing. Computers Ind Eng 178:109126

Chen Z, Fan Z-P (2023) Improvement strategies of battery driving range in an electric vehicle supply chain considering subsidy threshold and cost misreporting. Ann Oper Res 326:89–113

Della Bella S, Sen B, Cimpan C, Rocco MV, Liu G (2023) Exploring the impact of recycling on demand–supply balance of critical materials in green transition: a dynamic multi-regional waste input–output analysis. Environ Sci Technol 57:10221–10230

Fan T, Liang W, Guo W, Feng T, Li W (2023) Life cycle assessment of electric vehicles’ lithium-ion batteries reused for energy storage. J Energy Storage 71:108126

Gong H, Hansen T (2023) The rise of China’s new energy vehicle lithium-ion battery industry: The coevolution of battery technological innovation systems and policies. Environ Innov Societal Transit 46:100689

Hu S, Liu Z, Tan Y, Cheng X, Chen Z, Long Z (2022) The status quo and future trends of new energy vehicle power batteries in China—Analysis from policy perspective. Energy Rep. 8:63–80

Jiang Z, Xu C (2023) Policy incentives, government subsidies, and technological innovation in new energy vehicle enterprises: Evidence from China. Energy Policy 177:113527

Kamath D, Moore S, Arsenault R, Anctil A (2023) A system dynamics model for end-of-life management of electric vehicle batteries in the US: Comparing the cost, carbon, and material requirements of remanufacturing and recycling. Resour, Conserv Recycling 196:107061

Kou M, Yang Y, Feng Z, Chen K, Wei J (2023) Are incentives excessive or insufficient? The impact of R&D fiscal policies on R&D inefficiency in China. Technol Forecast Soc Change 194:122707

Li J, He S, Zhang M (2023) Optimal pricing and warranty strategies of a closed‐loop supply chain under government subsidies. Int Transac Oper Res 32:3083–3107

Li J, & Lai KK (2023) The abatement contract for low-carbon demand in supply chain with single and multiple abatement mechanism under asymmetric information. Ann Oper Res 1–23

Liu Y, Kokko A (2013) Who does what in China’s new energy vehicle industry? Energy policy 57:21–29

Niromandfam A, Yazdankhah AS, Kazemzadeh R (2020) Modeling demand response based on utility function considering wind profit maximization in the day-ahead market. J Clean Prod 251:119317

Reinhart L, Vrucak D, Woeste R, Lucas H, Rombach E, Friedrich B, Letmathe P (2023) Pyrometallurgical recycling of different lithium-ion battery cell systems: Economic and technical analysis. J Clean Prod 416:137834

Saeedi M, Parhazeh S, Tavakkoli-Moghaddam R, Khalili-Fard A (2024) Designing a two-stage model for a sustainable closed-loop electric vehicle battery supply chain network: A scenario-based stochastic programming approach. Computers Ind Eng 190:110036

Sieg P, Posadzińska I, Jóźwiak M (2023) Academic entrepreneurship as a source of innovation for sustainable development. Technol Forecast Soc Change 194:122695

Song L, Wen Y (2023) Financial subsidies, tax incentives and technological innovation in China’s integrated circuit industry. J Innov Knowl 8:100406

Su C-W, Yuan X, Shao X, & Moldovan N-C (2023) Explore the environmental benefits of new energy vehicles: evidence from China. Ann Oper Res 1–20

Tang C, Hou Q, & He T (2024) Research on closed-loop supply chain decision-making of power battery echelon utilization under the scenario of trade-in. Modern Supply Chain Res App 6:272–302

Von Stackelberg H (1952) The Theory of the Market Economy, (1952). William Hodge, London

Wang Y, Zhang X, Cheng T, Wu T-H (2023) Choice of the co-opetition model for a new energy vehicle supply chain under government subsidies. Transportation Res Part E: Logist Transportation Rev 179:103326

Xu X, Zhang M, Dou G, Yu Y (2023) Coordination of a supply chain with an online platform considering green technology in the blockchain era. Int J Prod Res 61:3793–3810

Xu XL, Chen HH (2020) Exploring the innovation efficiency of new energy vehicle enterprises in China. Clean Technol Environ Policy 22:1671–1685

Yi Y, Zhang M, Zhang A, Li Y (2024) Can “dual credit” replace “subsidies” successfully?-based on analysis of vehicle supply chain decisions under the digital transformation of technology. Energy Econ 130:107303

Zhang H, Zhao F, Hao H, Liu Z (2023) Comparative analysis of life cycle greenhouse gas emission of passenger cars: A case study in China. Energy 265:126282

Zhao X, Li X, Jiao D, Mao Y, Sun J, Liu G (2024) Policy incentives and electric vehicle adoption in China: From a perspective of policy mixes. Transportation Res Part A: Policy Pract 190:104235

Zhu Y, Hu Y, & Zhu Y (2024) Can China’s energy policies achieve the” dual carbon” goal? A multi-dimensional analysis based on policy text tools. Environ, Develop Sustain 1-40

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the financial support of the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 23BJY151) and the Key Project of Graduate Research Innovation Project of Harbin University of Commerce (Grant No. YJSCX2024-801HSD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

1st Author (SZB): funding acquisition, supervision, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, validation. 2nd Author (HH): conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, visualization, and writing original manuscript and revised manuscript. 2nd Author(H H) should be regarded as co-first author. 3rd Author (YL): conceptualization, supervision and writing-review. All authors substantially contributed to the article and approved the resubmitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study, primary conducted at the School of Management, Harbin University of Commerce, utilized simulated data generated through computational modeling and simulation techniques. The data used in this research are entirely artificial and do not involve human participants, personal information, or any identifiable data. Given that no real-world human subjects or sensitive data were involved, ethical approval was not required for this study according to local and national regulations regarding research ethics. All procedures followed in this study adhere to general ethical standards for research involving simulated data.

Informed consent

This study utilized simulated data generated through computational modeling and simulation techniques, which means that no human participants were involved, and no personal or identifiable data were used. Given the nature of the research relying solely on artificially created data rather than real-world human subjects, obtaining informed consent was not applicable. According to local and national regulations concerning research ethics in China, studies that do not involve human participants or their data are exempt from requiring informed consent. Therefore, for this study no informed consent was sought or required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, S., He, H. & Li, Y. Government subsidy strategies for power batteries of new energy vehicles: the perspectives of R&D and recycling. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 748 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05103-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05103-4