Abstract

This study explores low-carbon promotion competition between dual-channel green manufacturers and retailers against the backdrop of global low-carbon economic transformation and deepening green consumption preferences, aiming to uncover whether low-carbon competition drives the low-carbon transformation of supply chain enterprises. It also analyzes the equilibrium choices and coordination strategies of green manufacturers and retailers in low-carbon promotion competition. To achieve this, the study creates base models of centralized (C) and decentralized (D) low-carbon promotion competitions without government subsidies, followed by a low-carbon promotion competition model with government subsidies (DG). In the expanded models, a unilateral cost-sharing contract (CSG-S) and a bidirectional cost-sharing contract (CSG-D) are added to investigate supply chain collaborative optimization routes in low-carbon competitive settings. Finally, numerical simulations use fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) industry background data to support comparative analysis. Results show that green manufacturers have significant advantages in low-carbon promotion competition (under D and DG models). However, low-carbon competition can also moderately erode green brands’ profits, reputation, and emission reduction capabilities, impeding low-carbon transformation progress—there exists a risk of greenwashing in low-carbon promotion investments under competitive scenarios, but government low-carbon subsidies can further promote the reduction of carbon emission levels. As the DG, CSG-S, and CSG-D models gradually coordinate, the market demand gap between green manufacturers and retailers narrows, ultimately achieving mutual benefit among supply chain members, resolving low-carbon promotion competition conflicts, and facilitating synchronized development between low-carbon transformation and economic returns for both parties. This research provides a practical decision-making framework for governments to design targeted subsidy policies and for enterprises to formulate low-carbon competition strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Addressing climate change is a global imperative, and China’s “Dual Carbon” strategy (peaking carbon emissions by 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060) has emerged as a benchmark in global climate governance (Baste and Watson 2022; Magrinyà et al. 2023; Willetts 2023). This strategy, articulated in the State Council’s Action Plan for Carbon Dioxide Peaking Before 2030 and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology’s Green Manufacturing Engineering Implementation Guide, mandates industries to achieve low-carbon transitions through technological innovation and supply chain coordination. Within this framework, supply chain enterprises—particularly energy-intensive sectors like manufacturing and logistics—face unprecedented challenges (Khan et al. 2021; Eckerberg 2022). The fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) manufacturing sector, characterized by high market sensitivity and rapid consumption cycles, confronts unique difficulties in balancing cost efficiency with sustainability. Notably, online direct sales channels, accounting for 37% of China’s retail market by 2023, have intensified carbon footprints due to logistics and packaging demands, positioning this sector as a critical focal point for low-carbon innovation. This urgency underscores the need to examine how low-carbon competition catalyzes or impedes sustainable transitions, aligning with China’s strategic vision of building an “Ecological Civilization” and achieving a “Beautiful China”.

The global shift toward low-carbon development is profoundly reshaping consumer behavior (Ghosh et al. 2020; Sun et al. 2020; Lin et al. 2023). In China, this transition is accelerated by policy-driven initiatives and market forces. According to the China Green Consumption Report 2023, over 45% of Chinese consumers prioritize products with certified low-carbon labels, while Alibaba’s sustainability survey reveals that 52% of online shoppers are willing to pay premiums for eco-friendly packaging. These trends resonate with the National Development and Reform Commission’s 14th Five-Year Plan for Circular Economy, which identifies green consumption as a driver for industrial transformation. Internationally, Deloitte’s 2024 report highlights that 85% of global firms have escalated sustainability investments, yet the efficacy of these efforts in sectors like FMCG remains underexplored, particularly in balancing competitive dynamics with emission reductions. For manufacturers pursuing sustainable growth, adopting low-carbon strategies and streamlining supply chains for efficiency is imperative. However, the transition to low-carbon consumerism presents dual challenges and opportunities. Amid competitive pressures and the financial burdens of low-carbon transitions, strengthening contractual partnerships across supply chains becomes essential (Karle et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2024; Cheng et al. 2024).

The interplay between low-carbon competition and supply chain coordination rests on two theoretical pillars: game-theoretic interactions among stakeholders and the resource-based view of green capabilities. Prior studies suggest that competitive pressures can spur innovation diffusion (Wu et al. 2025; Ji et al. 2025), yet excessive rivalry may fragment collaborative efforts. For instance, in the photovoltaic industry, intense competition drove technological advancements but also led to overcapacity and profit erosion (Tsanakas et al. 2016; Choi 2024). This duality necessitates a nuanced examination of how “low-carbon competition” operates across supply chain contexts—whether it accelerates emission reductions or impedes progress through coordination failures.

Against this backdrop, this study investigates green manufacturers expanding into online direct sales channels to secure market share and drive low-carbon transitions. By designing a hybrid incentive mechanism combining government subsidies and cost-sharing contracts, we explore coordination strategies for low-carbon supply chain competition. Our research aims to address the following questions: Dual-Channel Low-Carbon Competition: Does competition (e.g., carbon labeling rivalry) accelerate emission reductions among green manufacturers, or does it risk “greenwashing” that hinders genuine progress? Demand Elasticity Analysis: How do promotional investments in low-carbon attributes (e.g., green marketing, eco-packaging) influence demand elasticity across supply chain tiers? Government Incentive Efficacy: How do subsidies impact the low-carbon performance of upstream and downstream supply chain members, and what is their effect on overall efficiency? Contract Coordination: Can cost-sharing contracts enhance emission reduction efficiency while mitigating the adverse effects of low-carbon advertising competition? Do unilateral or bilateral contracts yield Pareto improvements?

This study makes pivotal contributions in three areas: (1) It delves into manufacturers’ shift from passive players to strategic leaders in the low-carbon advertising value chain. Results show that opening online direct-sales channels transforms manufacturers’ roles, giving them a market edge in low-carbon competition and offering new strategies for driving low-carbon transitions in the supply chain. By incorporating low-carbon competition intensity into the market demand model, it advances the understanding of low-carbon advertising’s value. (2) It leverages low-carbon advertising competition to create a competitive edge for the green manufacturing sector’s low-carbon transition, innovatively expanding the traditional goodwill model. (3) It proposes a supply chain coordination strategy that combines government subsidies with cost-sharing. This strategy offers a new solution for supply chain management and informs policymakers on crafting effective incentive mechanisms. Findings indicate that while low-carbon competition can capture market share, it may also lead to greenwashing, reducing green brands’ revenue, goodwill, and emission reduction capacity. However, government low-carbon subsidies can further lower carbon emission levels.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section “Literature review” reviews the relevant literature; Section “The models” presents the assumptions and symbol explanations; Section “Expansion” establishes the basic model and government subsidy model; Section “Numerical analysis” extends the model and designs the contract coordination model; and finally, examples are used to compare and verify the models to gain more managerial insights and conclusions.

Literature review

Low-carbon emission reduction in green supply chains

Enterprises are increasingly prioritizing investments in carbon reduction technologies (Cai and Jiang 2023; Yan et al. 2024; Liu et al. 2025), a strategic imperative for supply chains to enhance both emission mitigation capabilities and ecological credibility. Such investments serve as a cornerstone for accelerating the transition toward sustainable, low-carbon supply chain operations (He et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2018). Existing studies, however, exhibit critical limitations in modeling dynamic interactions between stakeholders. Ghosh and Shah (2015) proved through the static cooperation model that the cost sharing contract can encourage manufacturers and retailers to jointly invest in low-carbon technologies, but ignored the impact of long-term dynamic competition on emission reduction efficiency; Similarly, Li et al. (2016) analyzed the promotion effect of retailer marketing on manufacturers’ emission reduction based on the short-term static game, but could not explain the intertemporal synergy effect of technology marketing investment. Although Jia and Liu (2023) introduced the framework of differential game and duopoly game respectively, its model still simplified the supply chain members to complete cooperation or complete competition, ignoring the interactive evolution of technology diffusion and market penetration under the dynamic competition cooperation relationship. In addition, in the dimension of low-carbon investment, scholars have not yet formed a systematic understanding of the synergy between technology research and development and marketing strategies. Liu et al. (2012) and Hildebrand et al. (2017) respectively emphasized the driving effect of consumers’ environmental awareness and green marketing on low-carbon transformation, but the former only analyzed the behavior of a single enterprise, while the latter separated the dynamic relationship between marketing investment and technology research and development. Shen et al. (2022) found the complementarity between manufacturers’ technology investment and retailers’ low-carbon certification, but did not solve the resource allocation conflict under dynamic competition.

In this regard, this paper breaks through the existing limitations: first, a dynamic differential game model is established to analyze the equilibrium strategies of dual channel manufacturers and retailers in the channel low-carbon marketing competition, providing a new decision-making paradigm for the supply chain low-carbon competition and cooperation.

Government low-carbon subsidy policy

Government subsidies are key to incentivizing carbon reduction across the entire supply chain, but existing research shows discrepancies in policy design, coordination mechanisms, and dynamic interactions. Wang and Choi (2020) demonstrated that a cap-and-trade system with flexible emission constraints can achieve Pareto-efficient coordination between manufacturers and suppliers, but their model assumed a fixed subsidy rate, neglecting dynamic adjustments based on technological maturity. Similarly, Yao et al. (2021) quantified the economic feasibility of carbon capture technology in steel production, revealing that government subsidies must cover at least 30% of R&D costs to trigger corporate adoption. However, their analysis overlooked the interdependence of the supply chain. A gap proposed by Zu et al. (2018) applies differential game theory, indicating that emission reduction efforts in decentralized supply chains require subsidies proportional to investment levels and consumer demand. Research increasingly recognizes the interaction between internal coordination and external subsidies. For example, Kang et al. (2019) used evolutionary game theory to demonstrate that cost-sharing contracts between manufacturers and retailers can amplify the subsidy effect, resulting in better emission reduction compared to unilateral policies. In contrast, Qu et al. (2019) highlighted the conflict: when subsidies are targeted only at manufacturers, retailers may free-ride on low-carbon marketing outcomes, leading to suboptimal emissions reductions at the system level. This tension highlights the necessity of integration mechanisms, as subsequently shown by He et al. (2023), who identified the synergies between subsidies and corporate social responsibility (CSR). The dynamic perspective reveals key limitations. Huang (2023) modeled the dual-market competition under government intervention and found that due to the technology lock-in effect, static subsidies cannot sustain retailer-manufacturer cooperation for more than 5–7 years. Similarly, Wang et al. (2022) developed a differential game framework where the government dynamically adjusts subsidies based on real-time emission data.

However, these studies either prioritize external policy instruments (e.g., Huang 2023) or prioritize Internal coordination (e.g., Fu et al. 2024; Li et al. 2019), without linking the two. Most studies focus on analyzing government subsidies without designing linkage mechanisms to coordinate internal and external incentives. The breakthrough of this paper lies in proposing an internal-external coordination contract of government subsidies and cost-sharing: dynamically linking government subsidies with the cost-sharing rate of supply chain members (retailers).

Low-carbon promotion coordination strategies

The interaction between low-carbon competition and supply chain strategy is rooted in resource dependence theory and non-cooperative game theory. Enterprises’ efforts to reduce carbon emissions are driven by both competitive pressure and cooperative incentives. This duality requires a coordination mechanism that balances intra chain collaboration and inter chain competition to achieve Pareto effective decarbonization (Lan and Papier 2018; Nematollahi et al. 2024). The existing research mainly focuses on the internal cost sharing or revenue sharing contract. For example, He et al. (2020) designed a cost sharing contract for the low-carbon service supply chain, proving that retailers who bear the R&D costs of manufacturers can maximize common profits. However, their model assumes static government policies and ignores dynamic subsidy adjustments. Similarly, Xiao et al. (2019) optimized the cooperative advertising contract in the two-level supply chain, but limited the coordination of internal marketing budget and ignored the external policy leverage. Competition distortions exacerbate these restrictions: when multiple manufacturers compete, the asymmetric cost sharing rate may lead to “carbon leakage”, as shown in Fadavi (2022) in the green product pricing game, in which 23% of the emission reduction is offset by the opportunistic behavior of competitors. Although some studies integrate government policies, they often isolate external intervention from internal coordination. Wang et al. (2024) analyzed the recovery subsidy in the closed-loop supply chain of e-commerce and found that altruistic preference increased the recovery rate, but their model excluded the coordination between retailers and manufacturers. On the contrary, Zhao and Zhao (2022) proposed the total amount control and trading contract under asymmetric information, but regarded the government carbon amount as an exogenous constraint and failed to link it with the sharing of promotion cost. This fragmentation persists in a dynamic environment: Xiang and Xu (2019) simulated the closed-loop supply chain cooperation with the Internet platform, but their dynamic strategy ignored the policy mechanism that is crucial to long-term compliance.

In short, compared with previous studies, our review shows that the current literature often studies government subsidies and supply chain cost sharing in isolation, and lacks linkage mechanism to offset the current large number of “green” marketing). Secondly, the existing models often assume that the supply chain members are fully cooperative or fully competitive, ignoring the complementarity and substitution of low-carbon technology and low-carbon marketing investment under the competition and cooperation game. Therefore, this paper makes a systematic analysis and comparison of various coordination contracts under government fiscal incentives. Based on the relevant literature, we have summarized the analysis presented in Table 1.

The models

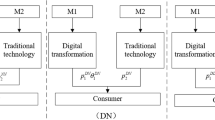

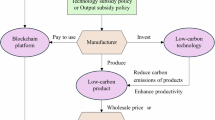

Faced with increasing competition in the market, participants must not only elevate the carbon efficiency of their offerings but also advocate for low-carbon practices across various dimensions to secure their competitive edge in the market. As seen in Fig. 1, this study looks at a dual-channel distribution network that includes an online and offline manufacturer as well as a traditional retailer. The company reduces carbon emissions through production while also pursuing a low-carbon promotion strategy in direct sales, resulting in a low-carbon promotion competition with the traditional retail channel. Among them, the low-carbon marketing investment of the manufacturer’s direct sales channel includes the costs of digital platform marketing, carbon neutral certification, etc., and the low-carbon marketing investment of the retailer covers the low-carbon display of physical stores, environmental protection promotion activities, etc. According to Kotler’s marketing 3.0 theory, this variable affects demand through the intermediary variable of green brand equity. Using a differential game method, this research investigates the equilibrium strategies of low-carbon activities among participants, and the best coordination contract in such competitive situations (Table 2).

Assumption 1. In the production of carbon emission reduction, whether the manufacturer can successfully reduce emissions depends on its investment in carbon emission reduction technology in the production process. However, with the aging of machinery and the progress of technology, if enterprises do not continuously invest in or update low-carbon emission reduction technologies, the efficiency of these emission reduction technologies will often be reduced. Therefore, drawing on the model proposed by He et al. (2023), the dynamic trajectory of product carbon reduction in this paper is expressed as follows:

where the initial value is \(E(0)={E}_{0}\); α is represents carbon mitigation effort factor, α > 0; and β is represents the inherent rate at which the impact of these efforts declines over time, β > 0.

Assumption 2. Referring to the classic goodwill model of Nerlove-Arrow (1962) and the modeling method of Asghari et al. (2022), this paper focuses on the reconstruction of low-carbon goodwill of products by low-carbon advertising in the dual channel supply chain. Therefore, this study incorporates the low-carbon promotion investment of manufacturers’ direct sales channels into the traditional goodwill model. The goodwill model designed for this study is as follows:

where the initial value is set as \(G(0)={G}_{0}\); σ represents the influence coefficient of promotional investment on the accumulation of goodwill; θ denotes the influence coefficient of the emission reduction level on the development of goodwill; and ε is the rate of natural decay of goodwill over time.

Assumption 3. Drawing from the cost function models presented in the literature Prasad et al. (2004), Zaccour (2008) and Giovanni (2010), the cost for participants is depicted as a quadratic function of both emission reduction and promotional efforts. This quadratic function form has been verified by the 2023 industry cost data of the new energy vehicle Committee of the China Association of automobile manufacturers. For example, the investment curve of emission reduction technology of Tesla Shanghai factory conforms to the quadratic function. This research delineates the cost function for members as follows:

where \({K}_{M1}\), \({K}_{M2}\), and \({K}_{R}\) denote the expense coefficients associated with members’ investments, \({K}_{M1} > 0,{K}_{M2} > 0,{K}_{R} > 0\).

Assumption 4. Citing Kopalle (1996), Fruchter et al. (2005), and Cattani et al. (2006)., it is posited that producers establish a consistent pricing scheme. At the same time, a competitive intensity coefficient representing low-carbon promotion was introduced to measure its impact on market demand. The demand function is established as follows:

where η represents the positive impact of \(E(t)\) on market demand, with η > 0; γ signifies the effect of \(G(t)\) on market demand, with γ > 0; τ is the impact coefficient of promotion on market demand, with τ > 0; a1 and a2 denote the natural market demand.

The long-run profit functions for manufacturers, retailers, and government benefits with government subsidies are expressed as follows:

No government subsidy–centralized decision model (C)

Without government subsidies in a centralized decision-making framework, members are focused on maximizing the profitability of the supply chain. As a result, the target function for the green supply chain model within this unified approach is established as follows:

Proposition 1 In the centralized decision model (C), the optimal equilibrium decision for low-carbon inputs is as follows:

Proposition 2 The optimal state trajectories for the degree of carbon emissions decrease and goodwill and the optimal trajectory stability values are as follows:

Proposition 3 The optimal profit for members are as follows:

where \({C}_{1}={x}_{0}-{x}_{\infty }^{C\ast },{C}_{2}={g}_{0}-{g}_{\infty }^{C\ast }\).

No government subsidy–low-carbon promotion competition model (D)

Within the realm of practical supply chain dynamics, achieving a consensus under a centralized decision model is often challenging, with low-carbon competition being the norm among members. Therefore, under low carbon promotion a competition, members will prioritize their own interests when making decisions, leading to a competitive decision-making model denoted as (D). In this model, both parties operate independently, engaging in a Nash differential game where they each aim to optimize their individual profits by determining their own strategic variables. The objective function under the competitive decentralized model is as follows:

Proposition 4 In the promotion competition model (D), the optimal equilibrium decision for low-carbon inputs is as follows:

Corollary 1

Corollary 1 indicates that increased consumer preference (γ) for brands prompts members to enhance their investments in emission reduction and promotion. Additionally, a heightened consumer inclination towards low-carbon products (η) positively influences investment in emission reduction, while the marketing investments of manufacturers and retailers remain unaffected by this preference. The influence measure of sustainable marketing on goodwill and market need (\(\sigma ,\tau\)) fosters more investment in low-carbon advertising. Conversely, the decay rate (β), the discount factor (ρ), and the cost parameters all exert a dampening effect on low-carbon initiatives. Furthermore, the vigor of rivalry in low-carbon promotion between manufacturers and retailers actively encourages investment in marketing efforts. Notably, as the competitive fervor in advertising escalates, it acts as a catalyst for increased advertising investments by both parties.

Corollary 2

\({I}^{C\ast } > {I}^{D\ast }\); when \(0\le k < \frac{\sigma \gamma }{\rho +\varepsilon }\) (\(k\in [0,1]\)), then \({A}_{M}^{C\ast } > {A}_{M}^{D\ast }\); when \(k\ge \frac{\sigma \gamma }{\rho +\varepsilon }\), then \({A}_{M}^{D\ast } > {A}_{M}^{C\ast }\); \({A}_{R}^{C\ast } > {A}_{R}^{D\ast }\)

Corollary 2, in competitive decision scenarios, manufacturers tend to allocate fewer resources towards low-carbon abatement compared to centralized decision structures, and similarly, retailers also reduce their low-carbon promotional efforts compared to what they would under centralized decisions. However, the promotional investments by manufacturers show an inverse trend: under low advertising competition, manufacturers invest more in promotion in centralized decisions than in competitive ones. Under high advertising competition, the opposite occurs, with manufacturers increasing their promotional efforts under competitive decisions more than in centralized ones. This suggests that in the midst of intense competition for low-carbon advertising, manufacturers are increasingly inclined to step up their marketing spend as this will exert a considerably greater constructive effect on their earnings and market need.

Proposition 5 The optimal state trajectories for the degree of carbon emissions decrease and goodwill and the optimal trajectory stability values are as follows:

Proposition 6 In the low-carbon promotion competition model, the optimal profit for manufacturers and retailers is as follows:

where \({D}_{1}={x}_{0}-{x}_{\infty }^{D\ast },{D}_{2}={g}_{0}-{g}_{\infty }^{D\ast }\).

Government subsidy–low-carbon promotion competition model (DG)

In a fiercely competitive market environment, the government acts as an invisible regulator, coordinating the dynamic equilibrium between economic growth and environmental sustainability through fiscal incentives. The goal is to drive manufacturers’ investments in carbon abatement technologies via economic stimuli, thereby aligning corporate profit-maximization objectives with societal carbon reduction targets. Within the framework of the Government Subsidy–Low-Carbon Promotion Competition Model, the government provides financial incentives (denoted as the government subsidy ratio ϕ) to support manufacturers’ investments in carbon abatement technologies. Both manufacturers and retailers prioritize optimizing their own profits as their primary decision-making objectives. The sequential steps of this game-theoretic process are as follows:

Proposition 7 In the government subsidy–low-carbon promotion competition model (DG),the government’s subsidy rate is as follows:

Proposition 8 The optimal equilibrium decision for low-carbon inputs is as follows:

Proposition 9 The optimal state trajectories for the degree of carbon emissions decrease and goodwill and the optimal trajectory stability values are as follows:

Proposition 10 The optimal profit for manufacturers and retailers is as follows:

Corollary 3

(1) \({I}^{DG\ast }={I}^{C\ast } > {I}^{D\ast }\)

(2) When \(0\le k < \frac{\sigma \gamma }{\rho +\varepsilon }\) (\(k\in [0,1]\)), then \({A}_{M}^{C\ast } > {A}_{M}^{DG\ast }={A}_{M}^{D\ast }\); when \(k\ge \frac{\sigma \gamma }{\rho +\varepsilon }\), then \({A}_{M}^{DG\ast }={A}_{M}^{D\ast } > {A}_{M}^{C\ast }\)

(3) \({A}_{R}^{C\ast } > {A}_{R}^{DG\ast }={A}_{R}^{D\ast }\)

In the low-carbon competition model augmented by government subsidies, these incentives can encourage manufacturers to achieve a higher standard of carbon mitigation efforts. Given that the low-carbon subsidy policy is aimed at manufacturers’ investments in carbon abatement technologies, such subsidies do not stimulate additional investment in promotion. Consequently, the level of investment in promotion remains unchanged whether or not government subsidies are provided.

Expansion

Government subsidy–one-way cost-sharing contract model (CSG-S)

This section details a one-way cost-sharing’ agreement leveraging the manufacturer’s dominant position in the promotion competition. Under this agreement, the manufacturer compensates the retailer for a portion of the costs associated with low-carbon promotion. In the government-subsidized single cost-sharing contract model, with the manufacturer leading and the retailer following. The manufacturer assumes responsibility for a fraction of the retailer’s promotion expenses to enhance the retailer’s promotional motivation, with a sharing ratio denoted by \(\varpi\) where 0 ≤ \(\varpi\) ≤ 1. The sequential steps of this game are delineated as follows: the government starts by granting a subsidy coefficient to the manufacturer for their carbon abatement endeavors. Then, the manufacturer decides on the optimal levels of emission reduction and promotion, as well as the share of advertising costs to be borne by the retailer. Afterward, the retailer determines the optimal promotion effort. The objective functions for the parties under the unilateral advertising cost-sharing contract are outlined as follows:

Proposition 11 In the government subsidy–one-way cost-sharing contract model, the subsidy and sharing rates that enable supply chain coordination are as follows:

Proposition 12 The optimal equilibrium decision for low-carbon inputs is as follows:

Proposition 13 The optimal state trajectories for the degree of carbon emissions decrease and goodwill and the optimal trajectory stability values are as follows:

Proposition 14 The optimal profit for manufacturers and retailers is as follows:

Corollary 4

(1) \({I}^{CSG-S\ast }={I}^{DG\ast }={I}^{C\ast } > {I}^{D\ast }\)

(2) When \(0 < k < \frac{\sigma \gamma }{\rho +\varepsilon }\) (\(k\in [0,1]\)), then \({A}_{M}^{C\ast } > {A}_{M}^{CSG-S\ast }={A}_{M}^{DG\ast }={A}_{M}^{D\ast }\); when \(k\ge \frac{\sigma \gamma }{\rho +\varepsilon }\), then \({A}_{M}^{CSG-S\ast }={A}_{M}^{DG\ast }={A}_{M}^{D\ast } > {A}_{M}^{C\ast }\)

(3) \({A}_{R}^{C\ast } > {A}_{R}^{CSG-S\ast } > {A}_{R}^{DG\ast }={A}_{R}^{D\ast }\)

Leveraging the manufacturer’s competitive edge in the low-carbon arena, a unilateral cost-sharing agreement was established, predicated on government incentives for the manufacturer’s investment in carbon mitigation efforts. It was confirmed that this arrangement bolstered the retailers’ commitment to promotion by having the manufacturer contribute to a portion of the retailers’ low-carbon promotional expenses.

Government subsidy–two-way cost-sharing contract model (CSG-D)

This section, aiming to thoroughly explore supply chain collaboration strategies and identify the optimal coordination strategy, proposes the government subsidy–two-way cost-sharing contract (CSG-D). Based on supply-chain coordination theory and the principle of incentive compatibility, CSG-D is put forward to address the limitations of traditional one-way cost-sharing mechanisms (as described in Section “Government subsidy–one-way cost-sharing contract model (CSG-S)”). By integrating external government subsidies with endogenous supply chain coordination and leveraging the Stackelberg differential game framework, this model optimizes collaboration among multiple stakeholders. The CSG-D contract goes beyond traditional one-sided cost-sharing by promoting mutually beneficial and consistent outcomes among all parties involved. Within the CSG-D framework, the manufacturer offers the retailer a cost-sharing rate of φ, while the retailer provides the manufacturer with a rate of υ The target profits for the manufacturer, retailer, and government in this model scenario are as follows:

Proposition 15 In the government subsidy–bidirectional advertising cost-sharing contract model, the optimal subsidy rate and sharing rate that can achieve supply chain coordination are as follows:

Proposition 16 The optimal equilibrium decision for low-carbon inputs is as follows:

Proposition 17 The optimal state trajectories for the degree of carbon emissions decrease and goodwill and the optimal trajectory stability values are as follows:

Proposition 18 The optimal profit for manufacturers and retailers is as follows:

Corollary 5

-

(1)

\({I}^{CSG-D\ast }={I}^{CSG-S\ast }={I}^{DG\ast }={I}^{C\ast } > {I}^{D\ast }\)

-

(2)

When \(0\le k < \frac{\sigma \gamma }{\rho +\varepsilon }\) (\(k\in [0,1]\)), then \({A}_{M}^{C\ast }={A}_{M}^{CSG-D\ast } > {A}_{M}^{CSG-S\ast }={A}_{M}^{DG\ast }={A}_{M}^{D\ast }\); when \(k\ge \frac{\sigma \gamma }{\rho +\varepsilon }\), then \({A}_{M}^{CSG-S\ast }={A}_{M}^{DG\ast }={A}_{M}^{D\ast } > {A}_{M}^{C\ast }={A}_{M}^{CSG-D\ast }\)

-

(3)

\({A}_{R}^{C\ast }={A}_{R}^{CSG-D\ast } > {A}_{R}^{CSG-S\ast } > {A}_{R}^{DG\ast }={A}_{R}^{D\ast }\)

Drawing on the synergistic advantages of the one-way cost-sharing agreement, which does not achieve perfect coordination, a two-way cost-sharing agreement has been crafted to more tightly integrate the stakeholders in an effort to achieve coordination. Research indicates that the two-way cost-sharing arrangement between manufacturers and retailers enhances their joint low-carbon promotional endeavors. Within the structure of the two-way cost-sharing agreement, the low-carbon initiatives undertaken by manufacturers and retailers can match the efforts made under a centralized decision-making process. This alignment ensures that the low-carbon initiatives remain stable and efficient.

Numerical analysis

This section uses MATLAB tools for numerical simulation to verify and visualize the relevant results and coordination effects. The parameter values in the case analysis are set proportionally based on real-world conditions, selecting FMCG supply chain enterprises as simulation cases for analysis. The discount rate often refers to the industry average cost of capital (WACC), such as 6%–12% for manufacturing; the setting of wholesale and retail prices is based on the markup rate of retail prices, while also referencing the wholesale and sales pricing of manufacturers (such as Wal Mart, Procter & Gamble) in the distribution channels. The FMCG is usually set at 1.3–2 times the wholesale price; according to the empirical research by Roy et al. (2022), the half-life of the effect of low-carbon technology is approximately 5–10 years, corresponding to a decay rate value range of 0.07–0.14; according to the Brand Z 2024 brand report by Kantar and the empirical research data by Wang et al. (2024), the decay rate range of FMCG brand reputation in the manufacturing industry is 5%–10%. This article discusses the decay of low-carbon reputation, considering the rapid iteration and updates of low-carbon technology and commercial marketing promotion, setting the decay rate of low-carbon reputation to a high value; other relevant data refer to the parameter configurations in supply chain-related literature as a basis (Chen et al. 2024; Zhang et al. 2024; Mardyana and Mahata 2024). To maintain the scientific nature of the research and ensure fairness in the analysis of competition intensity coefficients, the final determination of coefficient parameters is as follows: ρ = 0.1, α = 0.8, β = 0.2, σ = 0.8, θ = 0.8, Ɛ = 0.1, η = 0.7, γ = 0.7, k = 0.4, a1 = a2 = 20, τ = 0.7, p = 200, w = 100, \({{\rm{K}}}_{{\rm{m}}1}={{\rm{K}}}_{{\rm{m}}2}={{\rm{K}}}_{{\rm{r}}}=1\).

Trajectories of low-carbon emission reduction levels and goodwill over time

Figures 2 and 3 show the dynamic trajectory of low-carbon emission reduction level and goodwill under four scenarios: decentralized competition without subsidies (D, decentralized competition with government subsidies (DG), one-way cost sharing contract (CSG-S) and two-way cost sharing contract (CSG-D). Both emission reduction levels and goodwill show a monotonic increasing trend with time, and tend to steady-state equilibrium when t → ∞. The government subsidy model (DG, CSG-S, CSG-D) is superior to the non-subsidy model (D) in terms of emission reduction and goodwill accumulation. For example, the steady-state emission reduction level of DG exceeds D, which conforms to proposition 7 and Eq. (18), in which subsidies directly encourage manufacturers to increase investment in carbon emission reduction technologies. Similarly, the goodwill in DG exceeds D, because the subsidy enlarges the promotion efforts and strengthens the brand equity through the demand elasticity mechanism (Eq. (4)). Due to two-way resource sharing, two-way cost sharing contract (CSG-D) generates the highest steady-state goodwill Among them, the common cost sharing reduces the marginal cost of both sides, so as to achieve higher promotion investment. The one-way contract partially improves goodwill, but it lags behind the two-way cost sharing contract due to asymmetric resource allocation. The difference in emission reduction levels between subsidy and non-subsidy models stems from the equation dynamic subsidy mechanism, which links government support with real-time emission data. This ensures continuous investment in carbon emission reduction, rather than short-sighted optimization in model D. At the same time, the goodwill gap reflects the interaction between promotion competition (k) and subsidy driven coordination. Higher k intensifies advertising competition, but subsidies and contracts alleviate this by internalizing externalities.

k influence of coefficients on demand

Figures 4–6 analyze the impact of low-carbon promotion competition intensity (k) on the market demand of different model manufacturers and retailers. Overall trend: in the decentralized competition model (D and DG), demand increase with k, in which intensified competition (k) magnifies the sensitivity of demand to promotion efforts (τ), and verifies the hypothesis of “competition driven demand”. Government subsidies further magnified this effect, because subsidies reduced the net cost of manufacturers, thus achieving higher promotion investment. Under one-way cost sharing (CSG-S), Dr decreases with the increase of k, in contrast to DG and CSG-D This reflects the dominant position of manufacturers in setting allocation rates under asymmetric contracts. The limited budget of retailers limits their competitiveness, because K increases, leading to demand leakage to manufacturers. Two-way contracts (CSG-D) stabilize demand distribution: demand grow symmetrically with k, achieve Pareto efficiency, share costs, balance marginal income, and prevent market dominance.

In order to verify these findings, we conducted sensitivity analysis by changing key parameters: when consumer preference η increases, the demand gap between CSG-D and DG will expand, which confirms that mutual contract can better use consumer preference. When the government subsidy rate is reduced, the demand will be reduced, but due to internal cost sharing, CSG-D maintains its original demand. As the cost sharing coefficient increases, the demand of retailers in one-way contracts decreases, highlighting the vulnerability of retailers under one-way contracts. These tests confirm the robustness of our conclusion: government subsidies and two-way contracts enhance the elasticity of the system to parameter fluctuations.

k influence of coefficients on low-carbon promotion investment

Figures 7 and 8 analyze the relationship between competition intensity (k) and promotion investment across four modes: decentralized competition (D), government subsidy competition (DG), one-way cost sharing (CSG-S) and two-way cost sharing (CSG-D). Overall trend: dispersion model (D, DG): low-carbon promotion investment increase with k, which is consistent with Corollary 1,

The intensified competition magnifies the marginal return of promotion efforts. In the government subsidized DG, the manufacturer’s low-carbon promotion investment is always higher than the pure decentralized competition model, which is driven by the subsidy advantage and the reduction of the manufacturer’s net cost. Under the background of unilateral cost sharing arrangement (CSG-S), the manufacturer’s advertising investment remains unchanged regardless of the size of the competition. However, due to the manufacturer’s continuous competitive efforts stipulated in the agreement, retailers choose to reduce their investment. On the contrary, under the effect of CSG-D contract, both manufacturers and retailers have reached a high level under the centralized mode. The two-way cost sharing agreement (CSG-D) alleviates the adverse competition of promotion investment, urges members to adopt balanced and enhanced promotion strategies, coordinates and internalizes the externalities of competition, and eliminates the evil behavior of external competition. In addition, numerical analysis confirms the results outlined in inference 4.

k influence of coefficients on profit in the supply chain

Figures 9 and 10 compare the profits of different models and reveal the different dynamics driven by competition intensity (k). It is obvious that in the case of promotional competition (D, DG), the manufacturer’s income increases with the upgrading of competition, and at the same time, subsidies enlarge the elasticity of market demand; And the income of retailers decreases the intensification of competition. In addition, the low-carbon promotion competition model strengthened by government subsidies, as well as the single cost sharing and double cost sharing agreement models can improve the profits of members. The financial benefits of the three models (DG, CSG-S, CSG-D under government subsidies are better than those of the low-carbon competition promotion model (D) without government subsidies, which proves the effectiveness of low-carbon incentives supported by the government in a competitive environment. Manufacturers benefit from the advantages of dual channel sales and marketing, and often obtain higher profits than retailers in the competition. In addition, under the single and dual cost sharing contracts, it is observed that the profits of members are higher than those under the government subsidy low carbon promotion competition, which confirms the effectiveness of these contract strategies. We also tested the parameter changes to verify the relevant conclusions: when the subsidy rate is reduced, the profits of manufacturers and retailers are reduced, but the reduction rate under the two-way cost sharing contract is lower. The increase of consumer preference (η) can make the retailer’s profit increase in the contract higher than that in the non-contract model, highlighting the adaptability of two-way contract to market changes and risk mitigation ability.

At the same time, the strategic preferences of manufacturers and retailers differ when it comes to the choice of contract. Manufacturers opt for two-way cost-sharing agreements when the competition level in low-carbon promotion is below 0.768, and one-way agreements otherwise; similarly, retailers lean towards one-way cost-sharing agreements when the competition level is below 0.432, and two-way agreements in other cases. This preference is attributed to the competitive edge that manufacturers possess in low-carbon promotion. To encapsulate, government subsidies boost the profits of all members, and this enhancement is further amplified through contractual alliances. Both cost-sharing contracts are able to mediate conflicts between supply chain actors due to competition for low-carbon promotion, increasing their profits and contributing to the realization of Pareto-improving outcomes.

As shown in Fig. 11, \({J}_{G}^{CSG-D\ast } > {J}_{G}^{CSG-S\ast } > {J}_{G}^{DG\ast }\) the implementation of government subsidies, coupled with both two-way and one-way cost-sharing contracts, can lead to Pareto improvements in social welfare. These arrangements are beneficial for the enhancement of social welfare across the supply chain and for fostering healthy competition within the industry. In particular, two-way cost-sharing contracts are capable of delivering more stable and efficient social welfare outcomes in a market environment that emphasizes low-carbon competition.

The results in Fig. 12 illustrate that collaboration among members is practical and achievable in the context of promotion competition. Manufacturers have a higher share of promotion than retailers in both cost-sharing contracts. The more intense the advertising competition, the lower the share of both parties and the weaker the willingness to cooperate, because manufacturers have a market advantage in advertising competition, meaning manufacturers will forsake contractual cooperation to protect their interests; the lower the intensity of advertising competition, the higher the share of both parties and the stronger the willingness to cooperate. Meanwhile, manufacturers’ sharing rate in the mutual cost-sharing arrangement is higher than that in the single-party cost-sharing arrangement, indicating that the entry of retailers can further promote manufacturers’ willingness to share.

Conclusion and management enlightenment

This study reveals the dual impact of low-carbon competition on supply chain transformation, and puts forward the coordination strategy under the framework of the ‘dual-carbon’ objective. In addition to theoretical contributions, it also provides key management insights and policy recommendations:

Market advantage of dual-channel sales

Green manufacturers have a significant market advantage in dual-channel low-carbon promotion competition. At the same time, manufacturers expanding their online direct sales operations (e.g., FMCG companies) should prioritize low-carbon product differentiation over pure advertising competition. Our model suggests that allocating a large portion of promotional budgets to verifiable mitigation inputs (e.g., eco-packaging R&D) maximizes goodwill and avoids the risk of ‘greenwashing’ in low-carbon marketing competition. For example, FMCG manufacturers could work with logistics providers to develop recyclable packaging, turning low-carbon investments into cost savings and brand premiums. For example, P&G and Cainiao are working together to develop biodegradable packaging.

Balancing market demand

FMCG manufacturers can proactively utilize government subsidy strategies for low-carbon promotion of competitive intensity factors when faced with fluctuating market demand. For example, when there is a gap in market demand between manufacturers and retailers, market demand can be effectively balanced by reasonably adjusting the competitive intensity of promotions and combining it with government subsidies. In the energy-intensive FMCG manufacturing industry (e.g., beverages, snacks, etc.), the application of the CSG-D contract can focus more on the dynamic balancing of cooperative market shares among supply chain members through centralized decision-making simulation. In low energy-consuming industries (e.g., commodity manufacturing), the coordination contract focuses on optimizing the benefit distribution model. FMCG manufacturers need to flexibly adapt the contract application model to the characteristics of their industry to better accommodate changes in market demand.

Expand profits through subsidies and cooperation

In the FMCG supply chain, there will be opportunities for members’ profits to expand through the introduction of government subsidies and contractual cooperatives, despite the fierce competition in promotions. FMCG manufacturers should pay close attention to the tiered and typed subsidy criteria set by the government for different industries and firm sizes. For example, large FMCG companies can use subsidies to further optimize their low-carbon production processes and improve market competitiveness, while SMEs can use subsidies to improve their low-carbon transition capabilities and gradually integrate into the mainstream market. At the same time, manufacturers should actively cooperate with upstream and downstream enterprises in the supply chain to share costs and risks through the design of contract terms so as to gain more profit margins in competition.

Low carbon competition and cooperation

Cooperation among supply chain members is crucial for low-carbon promotion. The intensity of advertised competition is inversely proportional to sharing rates and willingness to cooperate. Manufacturers usually use their market dominance to prioritize their own interests. However, CSG-D contracts can increase manufacturers’ willingness to share by increasing retailer engagement. FMCG manufacturers should adjust their cooperation strategies according to their position in the supply chain, e.g., whether they are industry leaders. For example, large manufacturers can use their market influence to drive low-carbon cooperation across the supply chain; small and medium-sized manufacturers need to actively seek co-option with large retailers or other manufacturers for mutual benefit.

Contract preference

FMCG manufacturers should fully consider the impact of the intensity of competition for low-carbon promotion when choosing cost-sharing agreements, whether one-way or two-way. Under low competitive intensity, manufacturers prefer two-way contracts (CSG-D), which help them gain more support and resources in competition; retailers may prefer one-way contracts (CSG-S) to reduce their own risks. On the contrary, the preferences of manufacturers and retailers may be reversed under higher competitive intensity. FMCG manufacturers need to rationally choose the contract type according to the specifics of market competition (e.g., threat of new entrants, emergence of substitutes) as well as their own situation (e.g., market share, brand influence, etc.) in order to optimize supply chain management and improve market competitiveness.

Limitations

This study has certain limitations in spite of its findings. Firstly, this study is not comprehensive enough to consider the current diverse types of low-carbon policies; for example, the differential impacts of different policy instruments (e.g., carbon tax, carbon trading credits, etc.) on supply chain decision-making have not been fully explored. Secondly, the decision-making process of firms may be interfered with by a variety of irrational factors, such as firms’ unique cultural values, management’s risk appetite, and information asymmetry within the organization, which may deviate from the assumption of the rational economic man, thus affecting the actual implementation of low-carbon strategies. Finally, this study has not sufficiently explored the complex competitive relationships between multiple supply chain actors in a competitive market, especially in a multi-chain, multi-level market structure, where the interaction patterns and competitive strategies of each actor have not been fully analyzed.

Looking ahead

Future research can be carried out in the following directions: Firstly, in-depth exploration of the supply chain dynamic game under the multi-competitor scenario, analyzing the influence mechanism of bilateral or even multilateral competition on low-carbon investment, pricing strategy, and market equilibrium, and conducting empirical research with practical cases. In addition, corporate social responsibility (CSR) factors are incorporated into the low-carbon strategy framework to study how corporate social responsibility fulfillment can be mutually reinforced with low-carbon transition under different carbon policies and carbon trading mechanisms and how sustainable competitiveness of supply chains can be enhanced through CSR practices. Finally, it further deepens the understanding of chain network structure and synergistic mechanisms in the context of low-carbon strategies, especially by constructing more representative models to explore how supply chain members can achieve a balance between low-carbon goals and economic benefits through cooperation and competition under dynamically changing policy environments and market conditions.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Asghari M, Afshari H, Al-e-hashem SM, Fathollahi-Fard AM, Dulebenets MA (2022) Pricing and advertising decisions in a direct-sales closed-loop supply chain. Comput Ind Eng 171:108439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2022.108439

Baste IA, Watson RT (2022) Tackling the climate, biodiversity and pollution emergencies by making peace with nature 50 years after the Stockholm Conference. Glob Environ Change 73:102466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102466

Cai J, Jiang F (2023) Decision models of pricing and carbon emission reduction for low-carbon supply chain under cap-and-trade regulation. Int J Prod Econ 264:108964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2023.108964

Cattani K, Gilland W, Hesse HS, Swaminathan J (2006) Boiling frogs: pricing strategies for a manufacturer adding a direct channel that competes with the traditional channel. Prod Oper Manag 15:40–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2006.tb00002.x

Chen Y, Zhang T, Li G, Wang W (2024) The interaction between manufacturer’s showroom deployment and online selling formats. Transp Res E Logist Transp Rev 192:103773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2024.103773

Cheng S, Zhang F, Chen X (2024) Optimal contract design for a supply chain with information asymmetry under dual environmental responsibility constraints. Expert Syst Appl 237(Part A):121466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121466

Choi H (2024) Technology-push, demand-pull, and spillover from the major market demand: the case of the United States wind power market. Technol Soc 79:102684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102684

Eckerberg K (2022) The untold story of the world’s leading environmental institution: UNEP at fifty. Environ Politics 31:731–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2022.2066902

Fadavi A, Jolai F, Taleizadeh AA (2022) Green product design in a supply chain with considering marketing under competition and coordination. Environ Dev Sustain 24:11721–11759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01917-9

Fruchter GE, Tapiero CS (2005) Dynamic online and offline channel pricing for heterogeneous customers in virtual acceptance. Int Game Theory Rev 7:137–150. https://doi.org/10.1142/s0219198905000454

Fu C, Yu W, Wang Y, Feng W, Chen J (2024) Low-carbon strategy analysis in a construction supply chain considering government subsidies and contract design. J Clean Prod 470:143326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143326

Ghosh D, Shah J (2015) Supply chain analysis under green sensitive consumer demand and cost sharing contract. Int J Prod Econ 164(1):319–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.11.005

Ghosh SK, Seikh MR, Chakrabortty M (2020) Analyzing a stochastic dual-channel supply chain under consumers’ low carbon preferences and cap-and-trade regulation. Comput Ind Eng 149:106765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2020.106765

Giovanni PD (2010) Quality improvement vs. advertising support: which strategy works better for a manufacturer? Eur J Oper Res 208:119–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2010.08.003

He L, Yuan B, Bian J, Lai KK (2021) Differential game theoretic analysis of the dynamic emission abatement in low-carbon supply chains. Ann Oper Res 324:355–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-04134-9

He P, He Y, Shi C, Xu H, Zhou L (2020) Cost-sharing contract design in a low-carbon service supply chain. Comput Ind Eng 139:106160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2019.106160

He X, Jiang J, Hu W (2023) Cross effects of government subsidies and corporate social responsibility on carbon emissions reductions in an omnichannel supply chain system. Comput Ind Eng 175:108872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2022.108872

Hildebrand D, DeMotta Y, Sen S, Valenzuela A (2017) Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) contribution type. J Consum Res 44(4):738–758. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx063

Huang X (2023) Dynamic analysis of dual-market low-carbon supply chain: considering government intervention and joint promotion. J Clean Prod 411:137361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137361

Ji H, Yu Z, Tian GL, Wang DH, Wen Y (2025) Market competition, environmental, social and corporate governance investment, and enterprise green innovation performance. Financ Res Lett 77:107057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2025.107057

Jia Z, Liu X (2023) Uncertain stochastic hybrid differential game system with V-n jumps: saddle point equilibrium strategies and application to advertising duopoly game. Chaos Soliton Fract 171:113490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2023.113490

Kang K, Zhao Y, Zhang J, Qiang C (2019) Evolutionary game theoretic analysis on low-carbon strategy for supply chain enterprises. J Clean Prod 230:981–994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.118

Karle H, Peitz M, Reisinger M (2020) Segmentation versus agglomeration: competition between platforms with competitive sellers. J Political Econ 128:705720. https://doi.org/10.1086/705720

Karray S, Herrán MG (2021) The impact of a store brand introduction in a supply chain with competing manufacturers: the strategic role of pricing and advertising decision timing. Int J Prod Econ 244:108378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108378

Khan I, Hou F, Le HP, Ali SA (2021) Do natural resources, urbanization, and value-adding manufacturing affect environmental quality? Evidence from the top ten manufacturing countries. Resour Policy 72:102109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102109

Kopalle PK, Winer RS (1996) A dynamic model of reference price and expected quality. Mark Lett 7:41–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00557310

Lan Y, Li Y, Papier F (2018) Competition and coordination in a three-tier supply chain with differentiated channels. Eur J Oper Res 269(3):870–882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2018.02.032

Li B, Zhu M, Jiang Y, Li Z (2016) Pricing policies of a competitive dual-channel green supply chain. J Clean Prod 112:2029–2042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.05.017

Li J, Wang L, Tan X (2020) Sustainable design and optimization of coal supply chain network under different carbon emission policies. J Clean Prod 250:119548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119548

Li T, Zhang R, Zhao S, Liu B (2019) Low carbon strategy analysis under revenue-sharing and cost-sharing contracts. J Clean Prod 212:1462–1477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.282

Lin B, Yang M (2023) Choosing the right policy: factors influencing the preferences of consumption-side personal carbon reduction policies. J Environ Manag 326:116706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116706

Liu Y, Ma D, Hu J, Li Z (2025) Lenient or mandatory? Emission reduction coordination in supply chains considering consumers’ environmental concerns. J Clean Prod 500:145242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2025.145242

Liu Z, Anderson TD, Cruz JM (2012) Consumer environmental awareness and competition in two-stage supply chains. Eur J Oper Res 218(3):602–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2011.11.027

Magrinyà F, Mercadé-Aloy J, Ruiz-Apilánez B (2023) Merging green and active transportation infrastructure towards an equitable accessibility to green areas: Barcelona green axes. Land 12:919. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12040919

Mardyana R, Mahata G (2024) Impacts of dual carbon emission reduction technology and technology spillovers of deterioration reduction on supply chain system’s performances considering government incentives and contract design. J Clean Prod 468:142977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142977

Nematollahi M, Hosseini-Motlagh S-M, Pazari P (2024) Analytical insights into coordination and competition in dual-channel supply chains: a multi-factor dependent demand perspective. J Retail Consum Serv 78:103706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2024.103706

Nerlove M, Arrow KJ (1962) Optimal advertising policy under dynamic conditions. Economica 29:129–142

Prasad A, Sethi SP (2004) Competitive advertising under uncertainty: a stochastic differential game approach. J Optim Theory Appl 123:163–185. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:jota.0000043996.62867.20

Qu S, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Wahab M, Zhang G, Ye Y (2019) Optimal strategy for a green supply chain considering shipping policy and default risk. Comput Ind Eng 131:172–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2019.03.042

Roy M, Ghoddusi H, Trancik JE (2022) Evaluating low-carbon transportation technologies when demand responds to price. Environ Sci Technol 56(4). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c02052

Shang W, Han Z, Wei W, Li T (2025) Competition and cooperation between green and non - green supply chains under Government’s subsidy and carbon tax to consumers. Comput Ind Eng 203:110957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2025.110957

Shen Q, He B, Qing Q (2022) Interplays between manufacturer advertising and retailer store brand introduction: agency vs. wholesale contracts. J Retail Consum Serv 64:102801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102801

Sun L, Cao X, Alharthi M, Zhang J, Taghizadeh-Hesary F, Mohsin M (2020) Carbon emission transfer strategies in supply chain with lag time of emission reduction technologies and low-carbon preference of consumers. J Clean Prod 264:121664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121664

Tsanakas JA, Ha L, Buerhop C (2016) Faults and infrared thermographic diagnosis in operating c-Si photovoltaic modules: a review of research and future challenges. Renew Sust Energ Rev 62:695–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.04.079

Wang F, Li H, Cao Y, Zhang C, Ran Y (2022) Knowledge sharing strategy and emission reduction benefits of low carbon technology collaborative innovation in the green supply chain. Front Environ Sci 9:783835. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2021.783835

Wang F, Wang K, Han Y et al. (2024) Influences of design-driven FMCG on consumers’ purchase intentions: a test of S-O-R model. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:852. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03362-1

Wang S, Choi SH (2020) Pareto-efficient coordination of the contract-based MTO supply chain under flexible cap-and-trade emission constraint. J Clean Prod 250:119571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119571

Wang W, Hao S, He W, Mohamed MA (2022) Carbon emission reduction decisions in construction supply chain based on differential game with government. Build Environ 222:109149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109149

Willetts L (2023) Stockholm + 50: what does it mean for global health? Lancet Planet Health 6:388–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00100-0

Wu K, Zheng K (2025) Tax incentives, supply chain spillovers, and enterprise technological innovation. Int Rev Financ Anal 99:103930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2025.103930

Wu X, Zha Y, Yu Y (2022) Asymmetric retailers’ sales effort competition in the presence of a manufacturer’s help. Transp Res Part E Logist Transp Rev 159:102625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2022.102625

Xiang Z, Xu M (2019) Dynamic cooperation strategies of the closed-loop supply chain involving the internet service platform. J Clean Prod 220:1180–1193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.105919

Xiao D, Zhou Y-W, Zhong Y, Xie W (2019) Optimal cooperative advertising and ordering policies for a two-echelon supply chain. Comput Ind Eng 127:511–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2018.10.038

Yang Y, Yi C, Li H, Dong X, Yang L, Wang Z (2025) An analysis on the role of artificial intelligence in green supply chains. Technol Forecast Soc Change 217:124169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2025.124169

Yan L, Hong P, Wu Z (2024) Dynamic pricing and emission reduction efforts in a dual-channel green supply chain under bidirectional free riding. J Clean Prod 438:140713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140713

Yao X, Yuan X, Yu S, Lei M (2021) Economic feasibility analysis of carbon capture technology in steelworks based on system dynamics. J Clean Prod 322:129046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129046

Zaccour G (2008) On the coordination of dynamic marketing channels and two-part tariffs. Automatica 44:1233–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.automatica.2007.10.009

Zhang G, Xu J, Zhang Z, Chen W (2024) Optimal decision-making and coordination of the shipping logistics service supply chain cooperation mode under the carbon quota and trading mechanism. Ocean Coast Manag 255:107240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2024.107240

Zhang Y, Yang R, Shi X, Zhang W (2024) Operational strategies in a low-carbon supply chain considering the impact of carbon credit. J Clean Prod 442:141080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141080

Zhao L, Zhao Y (2022) Retailer-driven carbon emission reduction: contract design in the presence of information asymmetry and cap-and-trade. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29:82855–82872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-21231-9

Zhou Y, Ye X (2018) Differential game model of joint emission reduction strategies and contract design in a dual-channel supply chain. J Clean Prod 190:592–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.133

Zu Y, Chen L, Fan Y (2018) Research on low-carbon strategies in supply chain with environmental regulations based on differential game. J Clean Prod 177:527–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.220

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation (23XGL028).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Huiqin Zhang: review, supervision; Deru Xie: formal analysis, writing—original draft; Jianmin Xie: initial idea, investigation; Yuxiang Zhang: software, validation, visualization. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Xie, D., Xie, J. et al. Research on whether low-carbon competition accelerates low-carbon transition and coordination strategies in the context of “dual carbon”. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 933 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05188-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05188-x