Abstract

This study empirically evaluates the environmental impact of China’s 2012 Green Credit Guidelines on high-polluting firms, utilizing a panel dataset of A-share listed companies spanning 2006–2022. Applying a Difference-in-Differences (DID) framework, the analysis employs Bloomberg’s ESG environmental score—which comprehensively captures resource efficiency, pollution abatement, and ecological conservation—as a proxy for environmental performance. The findings reveal a statistically significant improvement of 2.3–3.7 points in environmental scores attributable to the policy intervention. According to Bloomberg’s calibration, this improvement corresponds to an estimated annual reduction of 1.2–1.8 million tons of SO₂ emissions, representing 15–22% of China’s mid-term (2020–2025) pollution abatement targets. Robustness checks, including Propensity Score Matching (PSM), placebo tests, and alternative measurements, validate the results. The paper identifies two key mechanisms through which green credit policies affect environmental performance: financing constraints and innovation compensation. Heterogeneity analysis shows that firms in eastern regions, competitive industries, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) experience greater impacts. This paper contributes to the global discourse on sustainable development, offering evidence of how green credit policies can improve high-polluting firms’ environmental performance based on their region, industry and ownership, and providing recommendations for supporting the transition to a greener economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Green finance policies, particularly green credit, have emerged as key instruments in global environmental governance. Over the past two decades, governments and financial institutions worldwide have increasingly adopted green credit policies to curb investments in high-pollution industries and redirect financial resources toward low-carbon technologies, clean energy, and environmentally sustainable projects (Yao et al., 2021). So, can these green credit policies promote industrial green innovation, structural upgrading, and sustainable economic and social development?

In many countries, including China, financial capital has traditionally flowed into energy-intensive sectors, spurring industrial growth but also intensifying environmental pollution, ecological damage, and public health risks (Balsalobre-Lorente et al., 2018). The European Union promotes green credit through the Green Finance Action Plan and encourages enterprises to adopt green technologies in their economic activities, and the United States has set up a clean energy bank to guide capital into the clean energy sector. In a large developing country like China, green credit policy has also gradually become an important tool to optimize the allocation of financial resources. As early as 2007, China’s financial administration and the Environmental Protection Administration put forward the concept of green credit, explicitly requiring banks and other financial institutions to establish a green credit mechanism to reduce investment in high-pollution, high-energy-consumption industries. In 2012, the CBIRC further issued the “Guidelines on Green Credit”, which takes energy conservation, emission reduction, environmental protection and other factors as the main basis for credit decision-making. Since then, the Chinese government has introduced a series of green credit policies to guide the flow of financial resources to the field of ecological protection and clean energy, in an attempt to inhibit the investment of heavily polluting enterprises, improve the quality of the environment, and promote the green and sustainable development of the economy through these measures (Li & Hu, 2014; Zhou et al., 2021).

While green credit policies have achieved notable results in curbing pollution and improving environmental governance, their impact on corporate behavior, particularly regarding environmental performance (hereinafter referred to as “EP”), remains unclear. The practical effect of green credit policy has gradually received the attention of scholars, and a large number of studies have explored the role of green credit policy in improving environmental information disclosure and corporate financing costs, investment and financing behavior, green innovation and investment efficiency (Yao et al., 2021; Li & Hu, 2014; Zhou et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024; Hu et al., 2023; Tian et al., 2024). Research shows that green credit policies can induce a coercive mechanism that compels firms to adopt greener technologies, improve investment efficiency, and reduce pollution. For example, by increasing compliance costs and regulatory pressures, green credit policies create higher risks for pollution-intensive investments, thereby prompting firms to adjust their investment strategies (Zhang et al., 2022). This not only curtails reckless investments in polluting industries but also enhances firms’ capacity to engage in green innovation and adopt sustainable business practices (Li et al., 2023; Tian et al., 2024). Additionally, firms seeking to access green credit are incentivized to strengthen internal management, optimize resource allocation, and improve operational efficiency (Li et al., 2022).

The academic literature identifies both external policy drivers and internal organizational factors shaping corporate environmental performance. Drawing on Institutional Theory (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), external policy drivers primarily involve government-mandated mechanisms like green credit policies. Specifically, green credit regulations create isomorphic pressures that align corporate behaviors with regulatory expectations (Guo et al., 2025). Empirical studies reveal that enterprises demonstrate measurable improvements in emission reductions when facing green credit evaluations, as evidenced by China’s differentiated credit pricing system (Zhang et al., 2024). This aligns with the institutional perspective that policy effectiveness depends on enforcement intensity and legitimacy-seeking behaviors (Ning et al., 2024; Rammelt & Gupta, 2021). However, the Porter Hypothesis’ innovation trade-off persists: while green credit policies may stimulate environmental innovation through financing constraints (Porter & Linde, 1995), their efficacy remains contingent on firms’ existing resource configurations (Lei et al., 2021). From a Resource-Based View (Barney, 1991), internal drivers bifurcate into structural resources and dynamic capabilities. Structural resources encompass tangible assets like pollution control infrastructure and intangible assets such as environmental management systems (Chen et al., 2017). Dynamic capabilities manifest through managerial cognition in interpreting regulatory signals and technical capacity in green innovation absorption (Ye et al., 2023). Recent evidence further highlights that CEOs with green backgrounds significantly enhance firms’ capacity to translate green credit incentives into high-quality innovation outcomes (Hu & Shi, 2025). Senior executives with environmental expertise demonstrate 23% higher efficiency in converting green investments into performance outcomes compared to conventional management teams (Zhao & Ye, 2025). Moreover, firms possessing slack resources exhibit greater adaptive capacity to reconcile regulatory compliance with operational efficiency—those maintaining R&D reserves above 5% of revenue show 40% lower compliance costs during regulatory transitions (Amore & Bennedsen, 2016). This resource-capability duality explains why firms with equivalent policy exposure demonstrate divergent EP trajectories (Nguyen et al., 2025).

This study aims to fill these gaps by conducting an empirical analysis of the net effect of green credit policies on EP, using the issuance of China’s 2012 Green Credit Guidelines (GCGs) as a landmark event. Specifically, it employs the Difference-in-Differences (DID) model to estimate the policy’s impact on heavily polluting enterprises. Additionally, we examine two key mechanisms—financing constraints and innovation compensation—through which green credit policies influence EP. Furthermore, the study considers heterogeneity in policy effects based on ownership structure, regional economic development, and market competition intensity. This approach provides a more nuanced understanding of how green credit policies shape corporate behavior across different contexts, offering valuable insights for policymakers and financial regulators aiming to optimize green finance frameworks and enhance environmental governance.

Compared to existing literature, this study makes several novel contributions. First, it utilizes the environmental scores from the Bloomberg ESG rating system to comprehensively measure EP. Unlike prior research that focuses on specific indicators such as green innovation or investment efficiency, this approach captures a broader spectrum of EP, encompassing resource utilization, pollution control, and ecological conservation. Second, it systematically analyzes the internal mechanisms through which green credit policies affect corporate behavior, providing empirical evidence on the roles of financing constraints and innovation compensation. These findings contribute to the theoretical discourse on green finance and offer practical guidance for improving the design and implementation of green credit policies. The results of this study have important implications for promoting the dual carbon goals of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality. By identifying the pathways through which green credit policies influence EP, the study offers actionable insights for enhancing policy effectiveness and fostering sustainable economic development.

Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses

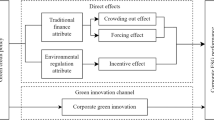

The impact of green credit policies on EP

Green credit policies have been introduced as an innovative financial tool to promote sustainable development by encouraging enterprises to improve their EP. Specifically, such policies reward firms based on their cumulative reduction in pollutant emissions, thereby incentivizing them to adopt cleaner production practices and contribute to environmental quality improvement (Kang et al., 2020). Empirical studies largely support the notion that green credit policies are effective in facilitating corporate green transformation and cleaner production (Li et al., 2018; Lin & Pan, 2024). A positive relationship between green credit policies and EP has been well-documented, with evidence suggesting that firms subject to green credit restrictions tend to enhance their pollution control measures and environmental outcomes (Lai et al., 2024; Zheng & Zhang, 2023).

Unlike traditional environmental regulations that rely heavily on direct governmental oversight, green credit policies operate by adjusting the financial incentives and costs faced by enterprises. By offering differentiated loan terms and pricing structures, these policies reduce access to financing for heavily polluting enterprises while providing preferential financing to environmentally friendly firms and projects (Ning et al., 2024). This approach not only fosters environmental improvements but also ensures economic returns, thus balancing environmental and economic objectives (Zheng & Zhang, 2023). Lei et al. (2021) further argue that appropriately designed green credit policies can optimize the economic structure while avoiding negative impacts on overall output and employment, thus creating a dual benefit of economic growth and environmental protection (Lei et al., 2021). The innovation-inducing potential of such policies, as posited by the Porter Hypothesis, is contingent upon two prerequisites. First, explicit long-term innovation incentives—such as technology subsidies or green patent protections—must be institutionalized. Second, firms must retain sufficient absorptive capacity, including R&D investments and technological reserves, to internalize and operationalize innovation outcomes. Empirical evidence highlights the risks of regulatory burden effects when policies prioritize compliance costs over complementary incentives. For instance, India’s Green Bank Programmer failed to stimulate meaningful innovation due to fragmented financing channels (Rajesh, 2022). Conversely, the EU Emissions Trading System, which integrates market-based carbon pricing with dedicated innovation funds (e.g., the Innovation Fund for Low-Carbon Technologies), has successfully incentivized firms to adopt green technologies for emission reductions (Dechezleprêtre et al., 2023). These cross-economy disparities underscore that the efficacy of green credit policies hinges not only on the equilibrium between regulatory constraints and innovation incentives but also on their alignment with firm-specific resource endowments and institutional ecosystems.

Nevertheless, there are concerns regarding the efficacy of green credit policies in consistently improving EP. Some researchers point out that China’s regulatory environment has, at times, created the illusion of achieving both economic and environmental gains, while actual progress in EP remains limited (Fu et al., 2020). In highly competitive markets, firms may resort to superficial compliance measures or “greenwashing” to secure favorable credit terms, thereby overstating their environmental achievements without genuine improvements (Amore & Bennedsen, 2016; Li et al., 2022). Institutional Theory further reveals that external institutional pressures (e.g., policy compliance requirements) force firms to align their behaviors with societal expectations, while the Resource-Based View emphasizes that internal resources (e.g., technological capabilities, managerial expertise) determine firms’ ability to effectively respond to policies. For example, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) exhibit stronger responses to green credit policies due to greater institutional constraints and resource endowments (Yue et al., 2025). Given these mixed findings, there remains considerable ambiguity regarding the true impact of green credit policies on EP. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: The implementation of green credit policies may enhance the environmental performance of heavily polluting enterprises.

Mechanisms through which green credit policies affect environmental performance

The relationship between green credit policies and EP can be explained through several theoretical mechanisms. One key pathway is the financing constraint effect, whereby green credit policies raise the threshold for obtaining financing by introducing EP as a critical criterion. This reduces information asymmetry in credit markets, compelling firms to adopt cleaner production practices as a prerequisite for obtaining loans (Qian & Yu, 2024). By restricting the availability of financial resources for heavily polluting enterprises, green credit policies signal a shift toward environmentally sustainable production and force firms to invest in pollution control and cleaner technologies, ultimately improving their EP (Tian et al., 2022).

In addition to signaling effects, green credit policies increase the costs of non-compliance for heavily polluting enterprises. Faced with higher borrowing costs and reduced financing options, such firms are compelled to phase out outdated production capacities, reduce production scales, and adopt more sustainable practices to offset the rising environmental management costs (Wang et al., 2021). Empirical evidence indicates that green credit policies have led to significant reductions in interest-bearing debt and long-term liabilities for heavily polluting firms, which in turn limits their scale of operation and accelerates energy conservation and emission reduction efforts (Zhang et al., 2024). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Green credit policies may enhance the environmental performance of heavily polluting enterprises through the financing constraint effect.

Conventionally, it has been argued that environmental regulations impose regulatory burdens on firms, thereby increasing their environmental compliance costs and reducing firm performance, potentially undermining productivity and innovation capabilities. However, Porter et al. posited that when firms face environmental regulations, they may be compelled to engage in R&D and innovation activities. By developing innovative products in response to regulatory requirements, firms can potentially enhance their productivity, improve product competitiveness, and boost overall performance. The economic benefits derived from technological advancements can offset the increased compliance costs associated with environmental regulations, achieving a win-win scenario of reduced pollution and improved production efficiency. This phenomenon has been termed the “Porter Effect” (Porter & Linde, 1995). Liu et al. (2025) demonstrate that stringent environmental regulations can drive technological innovation, which not only compensates for the costs of environmental management but also enhances firms’ long-term competitiveness.

Green innovation capacity, which directly reflects the innovation compensation effect, is positively correlated with EP. Process innovations aimed at improving production efficiency can lead to significant reductions in pollutant emissions and resource consumption (Li & Pang, 2023; Long et al., 2017). Green credit policies support this mechanism by providing dedicated funds for green innovation, particularly when guided by AI algorithms that match green projects with optimal credit terms (Hu et al., 2024). Thereby mitigating the financial burden of environmental compliance and encouraging firms to expand their investments in green technologies. As a result, heavily polluting enterprises are incentivized to adopt green innovations as a means of achieving industrial upgrading and enhancing their EP (Hu et al., 2021; Li et al., 2024). Additionally, by imposing financing constraints, green credit policies create a coercive environment that compels polluting enterprises to innovate in order to lower environmental compliance costs and secure financing (Zhang et al., 2022). However, not all studies confirm the effectiveness of this mechanism. Ramanathan et al. (2010) argue that environmental regulations may fail to stimulate sufficient green innovation to offset the associated costs, potentially leading to reduced profitability without generating significant innovation compensation effects. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3: Green credit policies may enhance the environmental performance of heavily polluting enterprises through the innovation compensation effect.

Heterogeneity in the effects of green credit policies on environmental performance

Compared to non-state-owned enterprises, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are more responsive to national policies, actively play an exemplary role, and demonstrate a stronger willingness to utilize credit resources to implement green production, thereby forming a synergistic mechanism between policy transmission and resource allocation (Chai et al., 2022; S. Tian et al., 2024). In contrast, the economic development of non-state-owned enterprises is profit-driven, with a greater emphasis on shareholder interests and capital return efficiency in their decision-making mechanisms. This results in a more pronounced cost-benefit trade-off in their response to green credit policies, rendering them less affected by such policies (Yang & Zhang, 2022). Therefore, the implementation of green credit policies may have a more significant promoting effect on the EP of SOEs (Jiang & Ma, 2024). The effectiveness of green credit in compelling heavily polluting enterprises to prevent pollution and improve EP varies asymmetrically depending on the region in which the enterprise is located and the degree of competition in the industry to which it belongs (Lyu et al., 2024). Compared to the central and western regions, the eastern region has a strong economic foundation, a relatively well-developed system, and is entrusted with more environmental governance responsibilities (Wu et al., 2023). Local enterprises in the eastern region face dual pressures when implementing green credit policies: they must not only promote industrial upgrading but also meet environmental compliance requirements. In contrast, the central and western regions are still in the stage of prioritizing economic growth, with relatively fewer environmental responsibilities. Enterprises in these regions are subject to weaker constraints from green credit policies and enjoy more lenient policy implementation (Lei et al., 2023). According to the concentration-profit margin hypothesis, enterprises can effectively weaken market competition intensity through cooperation mechanisms and by raising market entry barriers. In a monopoly market formed in this way, enterprises can implement high pricing strategies to obtain substantial profit returns (He et al., 2019). In a highly concentrated market environment, enterprises often occupy a dominant position, accumulate high profits, and face lower financing constraints. As a result, the implementation of green credit policies has a smaller restrictive effect on them (Lyu et al., 2024). Conversely, when enterprises operate in a highly competitive market environment, investors pay more attention to their environmental governance factors. Therefore, heavily polluting enterprises will attach greater importance to their own environmental governance, quickly adapt to and improve their environmental protection measures to meet the requirements of the market and financial institutions. Consequently, they are more significantly impacted by green credit policies (Lai et al., 2024; Ma et al., 2024). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4: The positive impact of green credit policies on environmental performance is stronger for state-owned enterprises, firms in eastern regions, and firms in highly competitive markets compared to non-SOEs, firms in central and western regions, and firms in less competitive markets.

Research design

Sample selection and data sources

The panel data of A-share listed companies from 2006 to 2022 are selected as the original sample, with the implementation of China’s 2012 Green Credit Guidelines serving as an exogenous event to analyze the impact of green credit policies on the EP of heavy polluting enterprises. The data for various variables is sourced from the financial annual reports of listed companies, CSMAR, and CNRDS databases. To ensure the accuracy of the empirical results, the original sample was processed according to the practices found in existing literature: companies with ST or PT classifications, abnormal financial conditions, severe missing financial data or key variables, and a debt-to-asset ratio not within the 0–1 range were excluded. All continuous variables underwent Winsorize treatment at the 1% and 99% quantiles to eliminate the effects of extreme outliers. Following the approach of Huang & Lei (2021), based on the “Announcement on Implementing Special Emission Limits of Atmospheric Pollutants” issued by the Ministry of Environmental Protection, enterprises are classified as heavy polluting or non-heavy polluting. Ultimately, 1413 companies and 14916 observations were obtained.

Variable selection

Dependent variable

Corporate EP: Drawing on the study by Wang & Sarkis (2017), the environmental score from the Bloomberg ESG rating system is used as a proxy for measuring EP. The environmental dimension within the Bloomberg ESG rating system includes indicators such as the company’s pollutant emissions, resource consumption, and waste management. A higher score indicates better EP of the company.

Explanatory variables

The interaction term of group dummy variables and time dummy variables (treat×post), which is a DID variable, is used as the explanatory variable. Here, ‘treat’ is the group dummy variable, distinguishing between the treatment group (heavy polluting enterprises) and the control group (non-heavy polluting enterprises); ‘post’ is the time dummy variable, differentiating between the periods before and after policy implementation.

Mediating variables

To investigate the mechanisms through which green credit policies affect EP, mediating variables such as the number of green patents (GP) and financing constraints (SA) are introduced for testing. Li et al. (2018) note that applying for green invention patents involves high technological thresholds, requiring companies to develop, promote, and apply corresponding green technologies on top of improving their product performance. The company’s green innovation capability is quantified by taking the natural logarithm plus one of the number of green invention patents filed independently or jointly by the company in a given year. Following the method of Hadlock & Pierce (2010), the SA index is constructed using company size and age to depict the degree of financing constraints faced by the company. To examine the financing constraint effect, we measure a firm’s financing constraints by FCA, defined as the absolute value of the SA index. A larger FCA index indicates more severe financing constraints.

Control variables

To effectively identify the net effect of the implementation of China’s 2012 Green Credit Guidelines on the EP of heavy polluting enterprises, relevant variables influencing corporate decision-making are controlled as much as possible. Referring to the common practices in existing research (Wang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022), the control variables selected include Debt to Asset Ratio (Lev), Return on Assets (ROA), Revenue Growth Rate (Growth), Firm Size (Size), Firm Age (Age), Ownership Nature (Sen), and Shareholder Concentration (Largest). Table 1 outlines the specific meanings of these variables.

Model specification

The baseline regression uses the DID method. To mitigate the endogeneity problem caused by sample selection bias, the PSM-DID model is chosen (Farooq et al., 2024), which can reduce the systematic differences that arise from not using random grouping and minimize the estimation bias of using the DID method alone. It allows for a more accurate assessment of the effect of green credit policies on improving EP. The baseline regression model is as follows:

In this model, \({{\rm{EP}}}_{{\rm{it}}}\) represents the EP of company i in year t, and p represents the industry. \({{treat}}_{i}\) is the policy implementation industry dummy variable, where \({{treat}}_{i}=1\) if the company belongs to the heavy polluting industry, and \({{treat}}_{i}=0\) otherwise. \({{\rm{Post}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\) is the time dummy variable for policy implementation, where \({pos}{t}_{t}=1\) if the year is 2012 or later, and \({pos}{t}_{t}=0\) otherwise. The coefficient \({\beta }_{1}\) measures the net effect of green credit policies on EP. \({{Controls}}_{{it}}\) refers to a series of control variables; \({\delta }_{i}\) denotes individual fixed effects, and \({\lambda }_{t}\) represents time fixed effects, used to control for company characteristics that do not change over time and macroeconomic environments that do not vary across firms. To reduce the potential impact of industry cyclical characteristics on the estimation results, the model includes \({{Indtrend}}_{p}\), which controls for industry time trends.

Methodology

This study systematically evaluates the net effect of China’s 2012 Green Credit Guidelines on the EP of heavily polluting firms. First, the parallel trend assumption is verified by examining the consistency of EP trends between the treatment group (heavily polluting firms) and the control group (non-heavy polluting firms) during the pre-policy period (2006–2011). Dynamic models confirm that pre-policy coefficients are statistically insignificant, satisfying the prerequisite for DID analysis. Second, baseline DID regression is adopted. The propensity score matching-DID (PSM-DID) method is adopted to address sample selection bias. Covariates such as firm size (Size), leverage ratio (Lev), and profitability (ROA) are balanced using nearest-neighbor matching (caliper = 0.01). Third, robustness checks are conducted to validate the results. Methods include placebo tests (100 random reassignments of treatment status), alternative matching methods (kernel and radius matching), Heckman two-stage correction for selection bias, exclusion of COVID-19 pandemic years (2020–2022), substitution of the dependent variable (environmental disclosure scores), and lagged policy variables to mitigate reverse causality. Fourth, we test mediating mechanisms. Financing constraints (SA index) and green innovation (green patents, GP) are analyzed by stratifying samples based on their median values. Finally, heterogeneity analysis explores differential policy impacts across ownership types (state-owned enterprises, SOEs vs. non-SOEs), regions (eastern vs. central-western China), and market competition levels (high vs. low), reflecting the moderating roles of institutional, geographical, and structural factors. This framework adheres to causal inference standards, balancing internal validity and generalizability to provide systematic evidence on the environmental governance mechanisms of green credit policies.

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of each variable. The minimum value of EP is 0.000, and the maximum value is 54.274, indicating a significant variation in the EP of Chinese listed companies during the sample period. Control variables such as Age exhibit significant variation, with standard deviations greater than 1. Other variables are generally consistent with existing literature and reflect the realities of listed companies.

Empirical results analysis

Parallel trend test

The DID method must satisfy the parallel trend assumption, which means that before the implementation of the green credit policy, the trends in EP of heavy polluting enterprises and non-heavy polluting enterprises should be consistent. Following the approach used in existing literature (Ma et al., 2024), the pre-treatment trend test method is applied to verify the validity of the parallel trend assumption. The specific model is as follows:

In this model, \({\text{Treat}}_{\text{it}}^{\text{n}}\) is a relative year policy variable generated, where \(n={-}6\) to −1 represents the 4 years preceding policy implementation (2006–2011), \(n={-}0\) marks the baseline year (2012), and \(n=1\) to −10 denotes post-policy years (2013–2022). The baseline year (2012) is excluded to avoid confounding policy anticipation effects. For heavy polluting enterprises, \({\text{Treat}}_{\text{it}}^{\text{n}}\) = 1, and for non-heavy polluting enterprises, \({\text{Treat}}_{\text{it}}^{\text{n}}\) = 0. The year prior to the implementation of the green credit policy is set as the base year for event analysis, and βn represents the regression coefficient relative to the base year. If βn before the policy implementation is not significantly different from 0, it indicates that the parallel trend assumption is satisfied.

By plotting the estimated results of β’s within the 90% confidence interval (Fig. 1), it can be observed that all pre-policy coefficients (2006–2011) are insignificant (p > 0.1) with 90% confidence intervals overlapping zero, indicating that there were no significant differences in EP between the treatment group and the control group before the implementation of the green credit policy, thus confirming the validity of the parallel trend assumption. After 2012, the coefficients become significant and show a clear upward trend, suggesting that the green credit policy has had a sustained positive impact on EP.

Propensity score matching analysis

To reduce the impact of sample heterogeneity and ensure the accuracy of the DID estimation, propensity score values were used to compare the differences in EP between the treatment group and the control group, and a matching analysis was conducted. Following existing literature and the R2 maximization rule (Liu & Dong, 2022), a Logit regression model was constructed. The control variables from the baseline model were selected as covariates to estimate the propensity scores of the sample companies. The treatment group and control group were matched using the radius caliper matching method (Table 3). After matching, there were no significant differences in the mean values of variables between the treatment and control groups. Compared to before matching, the standard deviations of the variables in the treatment and control groups significantly decreased after matching, indicating that the distribution of the treatment and control groups is well aligned, thereby satisfying the parallel trend assumption for PSM analysis.

To compare the differences in propensity score values between the treatment group and control group before and after matching, a kernel density function plot was drawn (Fig. 2). The comparison shows that there is a noticeable difference in the kernel density of the propensity score values between the treatment and control groups before matching. However, after matching, the kernel density curves of the two groups are nearly identical, indicating that the matched samples are more similar in terms of their characteristic variables. This further suggests that the matching results are satisfactory.

Difference-in-differences estimation

Based on the matching results, we excluded samples outside the common support region, yielding a final dataset of 14,905 observations. Table 4 presents the baseline DID and PSM-DID estimates. Columns (1)-(2) correspond to the standard DID models without and with controls, respectively. Columns (3)–(4) correspond to the PSM-DID models without and with controls, respectively. The coefficients of the interaction terms, both before and after the inclusion of control variables, are statistically significant at the 1% level. The results indicate that the implementation of the green credit policy has significantly enhanced the EP of heavily polluting enterprises compared to non-polluting firms, achieving a transformation from environmental pressure to motivation, which aligns with findings reported in prior studies (Ning et al., 2024). Specifically, all else being equal, the implementation of green credit policies leads to an increase in the environmental score of the ESG index by approximately 2.3 to 3.7 points. Per Bloomberg’s methodology, each 1-point ESG gain reduces SO₂ intensity by 8–10%. The observed improvement (2.3–3.7 points) implies 1.2–1.8 M tons annual SO₂ cuts, covering 15–22% of China’s 2020–2025 pollution control targets.

These studies have documented the positive role of green credit policies in driving pollution-intensive firms to improve EP through increased eco-investments and reduced emissions (Wang et al., 2021). By leveraging credit instruments, the policy has successfully guided enterprises to internalize environmental costs, thereby validating its effectiveness and feasibility in reconciling ecological imperatives with economic development goals (Zhang et al., 2021). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

Robustness test

Placebo test

To ensure that the impact on EP is due to the green credit policy rather than other external shocks, a placebo test is conducted following the method of Cantoni et al. (2017). The specific approach is as follows: randomly select an equivalent sample size to create a fictitious treatment group and control group, then repeat the regression 500 times using Eq. (1). The p-values and estimated coefficient values of the interaction term are recorded, and a kernel density plot is generated to compare with the p-values and estimated coefficient values from the original regression results. As shown in Fig. 3, the majority of the randomized p-values are greater than 0.1, and the distribution of the interaction term’s estimated coefficients is centered around zero and follows a normal distribution, significantly different from the original regression coefficient of 1.757. This rules out interference from other random factors, indicating that the regression results are robust.

Changing the matching method

To test the validity of the matching method, radius matching and kernel matching were applied to the initial sample, followed by DID estimation. As shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 5, the interaction term coefficients in the regression results are significantly positive at the 1% statistical level, which is consistent with the results obtained after radius caliper matching. This indicates that the implementation of green credit policies contributes to improving EP.

Heckman two-stage approach

Polluting enterprises may inherently exhibit characteristics such as heavy debt burdens, backward management practices, and insufficient innovation incentives. These systemic disparities relative to non-high-pollution enterprises could exist even in the absence of policy implementation, potentially compromising the validity of policy effect identification in this study. To mitigate these concerns, we adopt the Heckman two-stage treatment effect model. In the first stage, we construct an instrumental variable (IV) measuring provincial green credit development level, calculated as the ratio of interest payments by six high-energy-consuming industries (classified as large-scale industrial enterprises) to total interest payments by all large-scale industrial enterprises. This IV serves to predict the probability of an enterprise being subject to green credit restrictions. In the second Heckman stage, we incorporate the Inverse Mills Ratio (IMR) derived from the first-stage estimation as a control variable into our baseline model. The results demonstrate that the interaction term coefficient remains statistically significant at the 1% level, while the IMR achieves significance at the 1% level. This evidence substantiates the robustness of our baseline regression outcomes after accounting for potential self-selection bias in the model.

Mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic effects

The COVID-19 pandemic, emerging in late 2019, exerted widespread disruptions on global economic activities. Enterprises faced constraints in production and operations, along with tightened capital chains, which may have compromised the implementation effectiveness of green credit policies and reduced their willingness to invest in green projects. To address this confounding factor, we restrict our sample to observations prior to 2020 (i.e., 2019 and earlier) for regression analysis. As shown in Columns (5) of Table 5, the interaction term coefficients remain statistically significant and positive at conventional levels, consistent with the baseline regression results. This confirms that our findings are robust to potential distortions caused by pandemic-related economic shocks.

Changing the dependent variable

To avoid the impact of indicator selection randomness on the empirical results, following the approach of Zhang et al. (2019), a robustness test was conducted using a composite score of environmental management disclosure and environmental certification disclosure as proxy variables for EP. The regression results, as shown in column (6) of Table 5, indicate that the interaction term coefficients are significantly positive, confirming the robustness of the baseline regression results.

Lagging the explanatory variable

The green credit policy has gradually improved with the introduction of related policies over time, and there may be a time lag in the process from heavy polluting enterprises undertaking environmental governance to producing results. Following the approach of Ren et al. (2024), the lagged one-period treat×post is used as the explanatory variable, and the model is re-estimated. As shown in column (7) of Table 5, the interaction term coefficient is significantly positive at the 1% statistical level, indicating that the implementation of the green credit policy has long-term effects and that the baseline regression results are robust.

Mechanism analysis and heterogeneity test

Mechanism analysis

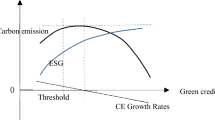

Financing constraint effect

To examine the financing constraint effect, a firm’s financing constraints are measured by the FCA, defined as the absolute value of the SA index. The SA index is calculated as: \({SA}=-0.737\times {ln}{Size}+0.043\times {({ln}{Size})}^{2}-0.04{Age}\) where Size denotes the firm’s total assets (in million USD), transformed by the natural logarithm; Age represents the number of years since the firm’s inception. A higher FCA value indicates stricter financing constraints. Based on the annual median SA index, the sample is divided into a high financing constraint group (high FCA) and a low financing constraint group (low FCA). The regression results are shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 6. The coefficient for treat×post in the high financing constraint group is significantly positive, while the interaction term coefficient in the low financing constraint group is not significant. This indicates that when a company faces strong financing constraints, green credit policies have a greater positive impact on its EP. Conversely, weaker financing constraints can reduce the incentivizing effect of green credit policies on EP. This result is consistent with previous studies (Ma et al., 2024). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is confirmed.

Innovation compensation effect

We first examine the impact of green credit policies on firms’ overall green innovation levels (GP), formally defined as: \({GP}=\mathrm{ln}({Green\; Invention\; Patents}+{Green\; Utility\; Model\; Patents}+1)\). The sample is divided into high green innovation (High GP) and low green innovation (Low GP) groups based on annual medians. As shown in Columns (3)–(4) of Table 6, the interaction term coefficient is significantly positive for the High GP group but statistically insignificant for the Low GP group. This suggests that the policy enhances EP primarily by incentivizing firms with preexisting innovation capabilities. This finding is similar to Zhang et al. (2022), though there are differences from the conclusions of Zhang et al. (2022).

To investigate the moderating role of firm size, we stratify the sample into large firms (High Size) and small firms (Low Size) based on total asset medians. Table 7 reveals divergent patterns: for large firms, the policy effect is significant only in the Low GP subgroup, implying that large low-innovation firms may engage in short-term compliance-driven innovation to circumvent regulatory pressures. This aligns with findings that executive ownership structures lacking minority shareholder protections often incentivize symbolic innovation over substantive environmental upgrades (Yue et al., 2025). In contrast, small firms exhibit significant effects solely in the High GP subgroup, indicating stronger path dependence on innovation capacity. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is confirmed.

To uncover potential “greenwashing” behaviors, we decompose green innovation into quality (GP1) and quantity (GP2). \({GP}1=\mathrm{ln}({Green\; Invention\; Patents}+1)\). \({GP}2=\mathrm{ln}\left({Green\; Utility\; Model\; Patents}+1\right)\). Table 8 shows that the policy has no statistically meaningful effect on innovation quality for either high- or low-quality groups. However, it significantly increases innovation quantity in the high-quantity subgroup, while the low-quantity subgroup remains unaffected. This divergence supports the strategic innovation hypothesis—firms prioritize quantity-driven utility models over substantive invention upgrades to symbolically comply with policy requirements. Our findings further highlight that policy-induced innovation heterogeneity may inadvertently exacerbate “greenwashing” risks, a critical nuance absent in prior studies.

Heterogeneity test

Regional heterogeneity

Due to regional economic differences, companies’ development levels and financial constraints vary, leading to different regional impacts of green credit policies. The sample is divided into two major regions: the eastern region and the central and western regions, to examine the regional heterogeneity of green credit policies’ impact on EP. As shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 9, the interaction term coefficient for the eastern sample group is significantly positive, while it is not significant for the central and western sample groups. This indicates that green credit policies have improved the EP of heavy polluting enterprises in the eastern region. These findings align with Vietnamese research documenting how regional economic priorities moderate green finance outcomes (Phuoc & Hung, 2024), but contrast with conclusions from Zhang et al. (2021). Specifically, the eastern region is characterized by stricter environmental regulations and more robust financial systems, which strongly encourage companies to improve their EP. Additionally, the eastern region’s advanced communication mechanisms and higher financial development levels facilitate the implementation and enforcement of green credit policies. In contrast, the central and western regions may face more significant financial constraints and less stringent regulatory enforcement, limiting the impact of green credit policies on EP. This regional heterogeneity underscores the need for tailored policy approaches that consider the specific economic and regulatory contexts of different regions.

Property heterogeneity

The nature of corporate ownership may affect a company’s financing capacity and EP. The sample is divided into two groups, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-state-owned enterprises (non-SOEs), based on ownership type, and regression analysis is conducted to examine the heterogeneity of ownership. The results are shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 9. The interaction term coefficient for the SOE sample group is significantly positive, while the interaction term coefficient for the non-SOE sample group is not significant. This indicates that the green credit policy has a significant impact on the EP of SOEs but does not improve the EP of non-SOEs. This finding is consistent with the research conclusions of Jiang & Ma (2024) and further corroborates the role of ownership structure in moderating policy responses, as minority shareholders in non-SOEs may prioritize short-term profits over long-term environmental commitments (Yue et al., 2025), but differs from those of Liu & Dong (2022) and Ma et al. (2024), indicating uncertainty regarding the impact of green credit policy on the EP of enterprises with different ownership structures. Possible explanations are that, unlike prior research, this study emphasizes the mediating role of ownership nature. Results show that state-owned enterprises (SOEs) benefit more from green credit policies and improve their EP, likely due to closer government ties and stable financial access. In contrast, non-state-owned enterprises (non-SOEs) face challenges in accessing green credit, possibly due to stricter criteria or a lack of support. These findings underscore the need for differentiated green credit management tailored to the unique characteristics of enterprises with varying ownership structures.

Industry heterogeneity

To further examine the industry heterogeneity of the impact of the green credit policy on EP, we refer to the method of Lai et al. (2024) and use the Lerner index, which reflects the strength of market monopoly power, to measure market competition intensity. The sample is divided into two groups: high-intensity monopoly and low-intensity monopoly, based on the annual median. The results are shown in columns (5) and (6) of Table 9. The interaction term coefficient for the low-monopoly sample group is significantly positive, while the interaction term coefficient for the high-monopoly sample group is not significant. This indicates that the green credit policy improves the EP of polluting companies in regions with fierce market competition but has no significant effect on the EP of companies in highly monopolized markets. This finding differs from existing research conclusions (Ma et al., 2024). The current study offers novel insights by emphasizing that the effectiveness of green credit policies hinges on the intensity of market competition. Specifically, in highly monopolized markets, firms with substantial market power (high Lerner index) may not feel compelled to invest in environmental improvements, as they can sustain profitability without significant changes. Conversely, in competitive markets, firms face greater pressure to enhance efficiency and reduce costs, making them more responsive to green credit policies as a means to achieve these goals. The complementary nature of market competition and green credit policies creates a forcing mechanism that drives firms to improve their EP. This insight underscores the importance of considering market structure when evaluating the impact of green credit policies, suggesting that differentiated approaches may be necessary to maximize policy effectiveness.

Conclusions and policy recommendations

The green credit policy represents an innovative financial strategy designed to improve EP by reallocating financial resources towards environmentally responsible enterprises. This policy is particularly significant within the context of China’s efforts to transform its economic growth model, foster corporate green transformation, and achieve high-quality sustainable development. Despite its potential, various impediments—including inadequate regulatory oversight, limited bank compliance and efficiency, and strategic corporate behaviors—have undermined its full implementation and effectiveness. This study employs Green Credit Guidelines as a quasi-natural experiment and uses a sample of A-share listed companies from 2006 to 2022. By applying the DID method, the study rigorously assesses the impact of green credit policies on the EP of heavily polluting enterprises and explores the underlying mechanisms driving this effect. This paper focuses on heavily polluting firms, a critical group where the potential for environmental improvement is greatest. By identifying the specific mechanisms—financing constraints and innovation compensation—that link green credit to enhanced EP, the study makes a unique contribution to understanding how financial incentives can alter corporate behavior.

The empirical analysis shows that green credit policies significantly improve the EP of heavily polluting firms. Using the Bloomberg ESG index as a comprehensive metric—covering resource utilization, pollution control, and ecological conservation—the results indicate that, when controlling for other factors, green credit policies lead to an increase in environmental scores by 2.3 to 3.7 points. The robustness of these findings is confirmed through a series of sensitivity analyses, including placebo tests, alternative matching approaches, different dependent variable specifications, and lagged independent variables. Furthermore, the study identifies two primary mechanisms through which green credit policies enhance EP: the financing constraint effect and the innovation compensation effect. First, by restricting credit access for high-pollution firms, the policy imposes financial discipline that compels emission reductions and operational efficiency improvements, confirming the foundational role of the financing constraint effect. Second, while the policy stimulates green innovation, its effectiveness exhibits notable size-dependent heterogeneity. Large firms leverage their financial and technological capacities to achieve environmental upgrades through high-quality innovation, whereas small firms often resort to quantity-driven, low-quality patenting as a symbolic compliance strategy, revealing latent “greenwashing” risks.

In addition to confirming the overall efficacy of green credit policies, the study highlights significant heterogeneity in policy impacts across different regions, industries, and ownership structures. Firms located in economically advanced eastern regions, those operating in highly competitive industries, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) exhibit more pronounced improvements in EP compared to their counterparts in central and western regions, less competitive markets, and non-state-owned enterprises. This heterogeneity underscores the importance of tailoring green credit policies to specific contexts to maximize their effectiveness.

Based on the study’s findings, the following policy recommendations are proposed to better leverage the resource reallocation and environmental governance functions of green credit policies, thereby promoting corporate green development:

-

(1)

Optimize policy coordination and incentive mechanisms to balance regulatory constraints and innovation. A cross-departmental governance framework should integrate environmental, financial, and industrial policies to align green credit objectives with practical enterprise needs. Environmental and financial authorities must collaborate to develop dynamically updated industry-specific green technology catalogs and pollution classification standards, ensuring the timely inclusion of emerging sectors such as electronic waste. To mitigate financing bottlenecks for small and medium-sized enterprises, diversified funding channels—including green bonds and EP-linked loans—should be expanded. For state-owned enterprises, embedding environmental metrics into executive performance evaluations will enhance accountability. By coupling specific regulatory constraints such as emission thresholds, innovation incentives like subsidized research and development loans, and capacity-building initiatives exemplified by technology transfer platforms, this approach fosters proactive environmental innovation over passive compliance, bridging short-term costs with long-term competitiveness.

-

(2)

Strengthen quality-centric oversight to curb greenwashing in green innovation. A certification system for green technologies must prioritize quantifiable environmental benefits, incorporating lifecycle assessments and real-world application viability to filter out low-impact patents. A “High-Quality Green Innovation Whitelist” should be introduced, granting tax rebates or preferential financing exclusively to listed technologies that demonstrate measurable emission reductions. Concurrently, mandatory disclosure of project-level environmental data—audited by independent third parties—and a centralized monitoring platform shared among regulators, financial institutions, and firms will improve transparency. These measures collectively address information asymmetry, deterring superficial patent accumulation while rewarding genuine technological advancements.

-

(3)

Implement spatially and structurally differentiated management strategies. Heterogeneity across spatial, ownership, and industrial dimensions of firms should be systematically incorporated into policy design. Regionally, market-based policy integration should be prioritized in eastern areas through innovative coupling mechanisms between green finance tools and carbon trading systems, while central-western regions require coordinated fiscal-banking interventions to mitigate transition risks, supported by cross-regional technology transfer platforms for equitable green innovation diffusion. Ownership-specific interventions necessitate binding incorporation of emission reduction metrics into executive evaluation systems for state-owned enterprises, contrasted with innovation-targeted tax incentives and patent quality screening mechanisms for private firms to curb low-value green technologies. Industrially, competitive sectors demand dynamic credit allocation rules pegged to verified emission performance alongside mandatory supply chain carbon disclosure, whereas monopolistic industries are regulated through technology spillover obligations linked to carbon quota adjustments, ensuring cross-firm green synergy. This stratified approach optimizes policy targeting while maintaining systemic coherence in ecological governance.

-

(4)

Drawing on empirical insights derived from China’s green credit policies, which bolster EP through mechanisms of financing constraints and innovation incentives, this study advances actionable recommendations for EU and U.S. policymakers. These recommendations aim to harmonize cross-border environmental standards, encourage high-quality innovation, and tailor regional strategies accordingly. By incorporating China’s pollutant classification criteria from the Green Credit Guidelines into the EU Taxonomy and U.S. climate disclosure frameworks, a unified standard of environmental accountability for multinational corporations would be established, reducing the risks of regulatory arbitrage. To counter the prevalence of low-quality innovation within small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the EU could employ the Horizon Europe Program to provide tiered R&D subsidies. These subsidies would be dynamically linked to carbon footprint reductions and prioritize technologies with measurable environmental benefits throughout their life cycles. Similarly, the U.S. should revise the Inflation Reduction Act by aligning tax incentives with the “emission reduction efficiency per unit” of green patents, ensuring that subsidies are awarded exclusively to innovations with established environmental benefits. Regionally, the EU could foster policy synergy by integrating green credit mechanisms with the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism in Northern Europe, while creating a Just Transition Fund for Eastern Europe to tackle green investment disparities. In the U.S., targeted support under the Community Reinvestment Act, such as linking green patent collateralization to localized air quality goals, could promote equitable environmental governance. These measures effectively transpose China’s empirical results into universally applicable governance instruments, highlighting the necessity of harmonized standards, controlled innovation quality, and flexible regional frameworks to connect academic insights with international policy implementation.

Data availability

The data is available from the CSMAR (China Stock Market & Accounting Research) database (https://data.csmar.com) and CNRDS (China National Economic and Social Development Statistics) database (https://www.cnrds.com. Both CSMAR and CNRDS are typically available through academic institutions, particularly those in China or with a focus on Chinese markets.

References

Amore MD, Bennedsen M (2016) Corporate governance and green innovation. J Environ Econ Manag 75:54–72

Balsalobre-Lorente D, Shahbaz M, Roubaud D, Farhani S (2018) How economic growth, renewable electricity and natural resources contribute to CO2 emissions? Energy Policy 113:356–367

Barney J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag 17(1):99–120

Cantoni D, Chen Y, Yang DY, Yuchtman N, Zhang YJ (2017) Curriculum and ideology. J Political Econ 125(2):338–392

Chai S, Zhang K, Wei W, Ma W, Abedin MZ (2022) The impact of green credit policy on enterprises’ financing behavior: evidence from Chinese heavily-polluting listed companies. J Clean Prod 363:132458

Chen N, Sung H-C, Yang J (2017) Ownership structure, corporate governance and investment efficiency of Chinese listed firms. Pac Account Rev 29(3):266–282

Dechezleprêtre A, Nachtigall D, Venmans F (2023) The joint impact of the European Union Emissions trading system on carbon emissions and economic performance. J Environ Econ Manag 118:102758

DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW (1983) The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am Sociol Rev 48(2):147

Farooq U, Thavorn J, Tabash MI (2024) Exploring the impact of environmental regulations and green innovation on corporate investment and cash management: evidence from Asian economies. China Finance Review International. https://doi.org/10.1108/CFRI-06-2024-0337

Fu T, Cai C, Jian Z (2020) The illusion of “win–win” solution: Why environmental regulation in China promotes firm performance? Struct Change Econ Dyn 52:366–373

Guo R, Zhang Y, Chen K, Wang Y, Ning L (2025) Heterogeneous impact of green finance instruments on firms’ green innovation novelty: policy mix or mess? Energy Econ 144:108315

Hadlock CJ, Pierce JR (2010) New evidence on measuring financial constraints: moving beyond the KZ index. Rev Financ Stud 23(5):1909–1940

He L, Wu C, Yang X, Liu J (2019) Corporate social responsibility, green credit, and corporate performance: an empirical analysis based on the mining, power, and steel industries of China. Nat Hazards 95(1–2):73–89

Hu G, Wang X, Wang Y (2021) Can the green credit policy stimulate green innovation in heavily polluting enterprises? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Energy Econ 98:105134

Hu W, Shi S (2025) CEO green background and enterprise green innovation. Int Rev Econ Financ 97:103765

Hu Y, Jin S, Ni J, Peng K, Zhang L (2023) Strategic or substantive green innovation: How do non-green firms respond to green credit policy? Econ Model 126:106451

Hu Z, Zhang J, Chang C-P (2024) AI and green credit: a new catalyst for green innovation in Chinese enterprises. Oeconomia Copernicana. https://doi.org/10.24136/oc.3020

Huang L, Lei Z (2021) How environmental regulation affect corporate green investment: evidence from China. J Clean Prod 279:123560

Jiang S, Ma Z (2024) How does the green credit policy affect corporate ESG performance? Int Rev Econ Financ 93:814–826

Kang H, Jung S-Y, Lee H (2020) The impact of green credit policy on manufacturers’ efforts to reduce suppliers’ pollution. J Clean Prod 248:119271

Lai J, Liu X, Yuan L (2024) Can green credit policy increase corporate pollution abatement efforts? Evidence from China. Int Rev Econ Financ 93:797–813

Lei N, Miao Q, Yao X (2023) Does the implementation of green credit policy improve the ESG performance of enterprises? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Econ Model 127:106478

Lei X, Wang Y, Zhao D, Chen Q (2021) The local-neighborhood effect of green credit on green economy: a spatial econometric investigation. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28(46):65776–65790

Li L, Su F, Zhang W, Mao J-Y (2018) Digital transformation by SME entrepreneurs: a capability perspective. Inf Syst J 28(6):1129–1157

Li P, Zou H, Coffman D, Mi Z, Du H (2024) The synergistic impact of incentive and regulatory environmental policies on firms’ environmental performance. J Environ Manag 365:121646

Li S, Liu Y, Xu Y (2022) Does ESG performance improve the quantity and quality of innovation? The mediating role of internal control effectiveness and analyst coverage. Sustainability 15(1):104

Li W, Hu M (2014) An overview of the environmental finance policies in China: Retrofitting an integrated mechanism for environmental management. Front Environ Sci Eng 8(3):316–328

Li W, Pang W (2023) The impact of digital inclusive finance on corporate ESG performance: Based on the perspective of corporate green technology innovation. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(24):65314–65327

Li X, Wang R, Shen ZY, Song M (2023) Green credit and corporate energy efficiency: Enterprise pollution transfer or green transformation. Energy 285:129345

Lin B, Pan T (2024) The impact of green credit on green transformation of heavily polluting enterprises: Reverse forcing or forward pushing? Energy Policy 184:113901

Liu Q, Dong B (2022) How does China’s green credit policy affect the green innovation of heavily polluting enterprises? The perspective of substantive and strategic innovations. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(51):77113–77130

Liu X, Zuo Z, Han J, Zhang W (2025) Is digital-green synergy the future of carbon emission performance? J Environ Manag 375:124156

Long X, Chen Y, Du J, Oh K, Han I (2017) Environmental innovation and its impact on economic and environmental performance: evidence from korean-owned firms in China. Energy Policy 107:131–137

Lyu Y, Bai Y, Zhang J (2024) Green finance policy and enterprise green development: evidence from China. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 31(1):414–432

Ma D, He Y, Zeng L (2024) Can green finance improve the ESG performance? Evidence from green credit policy in China. Energy Econ 137:107772

Nguyen DH, Nguyen HH, Nguyen THM, Chen XH (2025) Green credit’s impact on pollution and economic development: a study from vietnam. Res Int Bus Financ 73:102570

Ning J, Wang G, Xiong F, Yin S (2024) Green credit policy and corporate excess cash holdings. PLOS ONE 19(1):e0294079

Phuoc T, Hung NT (2024) Do green finance and energy counteract a sustainable environment in Vietnam? Quantile and frequency analysis. Int J Emerg Mark. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-03-2024-0507

Porter ME, Linde CVD (1995) Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J Econ Perspect 9(4):97–118

Qian S, Yu W (2024) Green finance and environmental, social, and governance performance. Int Rev Econ Financ 89:1185–1202

Rajesh S (2022) Green banking practices in India: opportunities and challenges. Asian J Manag Commer 3(1):161–165

Ramanathan R, Black A, Nath P, Muyldermans L (2010) Impact of environmental regulations on innovation and performance in the UK industrial sector. Manag Decis 48(10):1493–1513

Rammelt CF, Gupta J (2021) Inclusive is not an adjective, it transforms development: a post-growth interpretation of inclusive development. Environ Sci Policy 124:144–155

Ren S, Wu Y, Zhao L, Du L (2024) Third-party environmental information disclosure and firms’ carbon emissions. Energy Econ 131:107350

Tian C, Li X, Xiao L, Zhu B (2022) Exploring the impact of green credit policy on green transformation of heavy polluting industries. J Clean Prod 335:130257

Tian S, Zhang H, Xu G (2024) The effect of green credit on enterprises’ green transformation under sustainable development: evidence from green innovation in high-pollution enterprises in China. Sustainability 16(1):235

Wang X, Elahi E, Khalid Z (2022) Do green finance policies foster environmental, social, and governance performance of corporate? Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(22):14920

Wang Y, Lei X, Zhao D, Long R, Wu M (2021) The dual impacts of green credit on economy and environment: evidence from China. Sustainability 13(8):4574

Wang Z, Sarkis J (2017) Corporate social responsibility governance, outcomes, and financial performance. J Clean Prod 162:1607–1616

Wu K, Bai E, Zhu H, Lu Z, Zhu H (2023) Can green credit policy promote the high-quality development of China’s heavily-polluting enterprises? Sustainability 15(11):8470

Yang Y, Zhang Y (2022) The impact of the green credit policy on the short-term and long-term debt financing of heavily polluting enterprises: based on PSM-DID method. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(18):11287

Yao S, Pan Y, Sensoy A, Uddin GS, Cheng F (2021) Green credit policy and firm performance: What we learn from China. Energy Econ 101:105415

Ye F, Ouyang Y, Li Y (2023) Digital investment and environmental performance: The mediating roles of production efficiency and green innovation. Int J Prod Econ 259:108822

Yue S, Bajuri NH, Ye G, Ullah F (2025) Green awakening: The rising influence of minority shareholders and ESG in shaping China’s sustainable future. Sustain Futures 9:100441

Yue S, Khatib SFA, Bajuri NH, Sulimany HGH, Lee Y (2025) Executive ownership and minority shareholder protection: Drivers of environmental innovation in China’s A-share market. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.3158

Zhang H, Lai J, Kang C (2024) Green signalling under environmental pressure: Does local government environmental regulatory pressure promote corporate environmental information disclosure? Econ Anal Policy 83:813–844

Zhang K, Li Y, Qi Y, Shao S (2021) Can green credit policy improve environmental quality? Evidence from China. J Environ Manag 298:113445

Zhang L, Ye F, Yang L, Zhou G (2019) Impact of political connections on corporate environmental performance: From a green development perspective. Sustainability 11(5):1317

Zhang S, Wu Z, He Y, Hao Y (2022) How does the green credit policy affect the technological innovation of enterprises? Evidence from China. Energy Econ 113:106236

Zhao L, Ye J (2025) Has green credit promoted high-quality economic development? Evidence from China. Pol J Environ Stud 34(1):463–474

Zheng S, Zhang X (2023) Green credit policy and the green sustainable development of heavily polluting enterprises. Environ Eng Manag J 22(11):1961–1972

Zhou G, Liu C, Luo S (2021) Resource allocation effect of green credit policy: based on DID model. Mathematics 9(2):159

Acknowledgements

National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42361051 & 72104209), and the Thousands of Young and Middle-aged Backbone Teachers Training Foundation of Guangxi Universities (No. 2022QGRW002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Qiwen Dai; Methodology, Qiwen Dai, Yue Zhang, and Yanqiao Zheng; Software, Yue Zhang; Validation, Ju He and Zhongyuan Guo; Formal analysis, Qiwen Dai and Ju He; Investigation, Qiwen Dai; Data curation, Yue Zhang; Writing—original draft, Yue Zhang; Writing—review & editing, Ju He, Zhongyuan Guo, and Yanqiao Zheng; Visualization, Zhongyuan Guo; Supervision, Qiwen Dai and Yanqiao Zheng; Project administration, Qiwen Dai; Funding acquisition, Qiwen Dai and Yanqiao Zheng.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, Q., He, J., Guo, Z. et al. Green finance for sustainable development: analyzing the effects of green credit on high-polluting firms’ environmental performance. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 854 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05218-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05218-8