Abstract

The economic and cultural benefits of traditional Chinese villages are becoming increasingly apparent. Their spatial distribution characteristics play a significant role in promoting China’s rural revitalization and reviving national culture. Our study selected 826 traditional villages in the Yuan River Basin (YRB) area and used the nearest neighbor index, geographical concentration, and kernel density estimation methods to reveal the spatial distribution pattern and the spatial distribution differences of said villages. We used a geodetector to quantify the natural, economic, and cultural factors influencing the spatial pattern of traditional villages and measured their interactions. The results showed that (1) the spatial distribution of traditional villages in the YRB is characterized by obvious regional and ethnic agglomerations, forming a spatial distribution pattern of “two nuclei, one belt, and many points”. In terms of ethnicity, we found that the Han Chinese predominantly resided in the lowlands along the main valley of the Yuan River, while ethnic minorities inhabited both sides of the mountainous areas. (2) The number and proportion of minority populations, the proportion of primary industries, the slope of the terrain, the urbanization rate, and the proximity of water significantly influenced the spatial distribution of traditional villages in the YRB. These factors had different effects on different ethnic traditional villages, exacerbating the spatial agglomeration of each village. (3) Cross-detection revealed that the spatial distribution pattern of the YRB’s traditional villages emerged through three phases: layout, evolution in distribution, and retention patterns, shaped by natural, economic, and social factors. Through this study, we were able to quantify the influences of the natural environment, the economy, and culture on the distribution of traditional villages. In uncovering the spatial distribution patterns of traditional villages and the characteristics of ethnic agglomeration at the watershed scale, we have laid the foundation for the scientific research and protection of traditional villages in multi-ethnic areas of the YRB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chinese traditional villages, which are large in scale, numerous in number, and rich in history, carry the memory, wisdom, and national culture of the Chinese people. Collectively, they are the heart of Chinese farming civilization (Ma et al., 2024). The outstanding historical, cultural, social, and economic values of traditional villages are incredibly significant in promoting rural revitalization, carrying forward national culture, and enhancing cultural confidence; as a result, they have frequently been the focus of scholarly research (Karle and Carman, 2020).

Research on Chinese traditional villages originated from the excavation of local architecture in the 1930s (Lu, 2007). Within the past decade, increased government attention and aid have brought traditional villages, particularly their roles as development resources, into focus as a key area of rural research. At the micro-scale, scholars have focused on village architectural forms, site characteristics, and public spaces (Li et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2009), enriching the typology and cultural diversity of villages through case studies (Ding et al., 2024). At the meso-scale, existing studies have focused on village spatial morphology (Yang et al., 2021; Tao et al., 2013), cultural landscape (Hu et al., 2016), and land use (Zhang et al., 2023), exploring the structural evolution of villages with respect to human-land relations. At the macro scale, scholars have primarily explored the spatial distribution characteristics, resource values, and regional landscapes of traditional villages (Wu et al., 2023; Xiang et al., 2020). This has highlighted the diverse regional differences and varying development statuses of these villages (Sun et al., 2023). Existing studies have successfully uncovered the spatial distribution characteristics of traditional villages at the national, provincial, and municipal levels (Kang et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2023) and analyzed the factors influencing their formation, focusing on the natural geographic environment and socioeconomic development (Long and Zhao,2022). One example is Chen et al.’s study, which examined the spatial structure of Chinese ethnic minority villages and concluded that their special structures were primarily influenced by local topography and water systems (Chen et al., 2018). Gao et al. compared the different spatial distributions of the Yunnan ethnic minority and Han villages, observing that production modes and migration history were the primary factors influencing the distribution of ethnic minorities in the alpine area (Gao et al., 2024). However, these studies have several shortcomings: (1) The administrative boundaries of provinces and cities were used as the scope of the studies, which disrupted the connection between the villages’ distributions, their geographic spaces, and their ethnic cultures. This approach ultimately rendered assessments of village distribution unobjective and inaccurate. (2) Existing studies did not refine the spatial distribution characteristics and formation factors of different ethnic villages. This caused confusion and miscommunication regarding the spatial characteristics of ethnic villages and their cultures. (3) When analyzing the influencing factors, researcher experience (or qualitative inference) was the determining factor, with no quantitative method to identify any influencing factors. This approach made it impossible to identify the dominant factors, resulting in a lack of objectively scientific results.

The Yuan River Basin is situated in the transition zone between the ethnic minorities in the mountainous areas of southwest China and the Han Chinese in the eastern plains. This transitional natural environment and the intermingling of cultural areas make the traditional villages in the region valuable for their diversity. Studying the traditional villages in the Yuan River Basin can uncover the survival strategies of different ethnic groups and highlight the local knowledge embedded in the cultural ecology of each ethnic group. Additionally, the cultural and economic value of these villages represents a significant resource for rural development. Research on the Yuan River Basin can offer valuable insights for the revitalization and sustainable use of traditional villages in similar regions and provide Chinese case studies for the revitalization of ethnic minority villages in underdeveloped areas worldwide.

In light of the aforementioned deficits, we chose to examine the national-level traditional villages within the Yuan River Basin (YRB) and carried out a cross-regional integration study, with the goal to of achieving the following research objectives: (1) Reveal the distribution characteristics and ethnic differences of traditional villages in the YRB from a cross-regional perspective and understand the geographical environment in which each ethnic group survives and develops, (2) Quantitatively identify the dominant factors affecting the spatial distribution of traditional villages to make up for the defects of previous qualitative explanations, (3) Explore the influence of natural and human interactions on the spatial distribution of traditional villages, reveal the general law of the formation and evolution in traditional villages, and provide a reference for the conservation of traditional villages in areas with similar environments.

Study area and research methodology

Study area

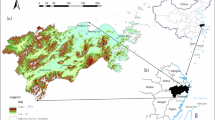

The Yuan River flows through southeastern Guizhou and western Hunan and is one of the tributaries of the middle reaches of the Yangtze River (Fig. 1). In terms of the natural environment, the YRB is a transition zone from the mountainous areas of southwest China to the middle/lower reaches of the Yangtze River. It boasts a complex and diverse topography, numerous tributaries, a distinctly three-dimensional climate, and a wide range of regional differences in resource conditions. This results in a high degree of diversity in the siting and development of traditional villages (Luo, 2010). From a humanistic and social perspective, the YRB spans 52 counties in the Guizhou, Hunan, Hubei, and Chongqing provinces and is located at the edge of each province. In terms of inter-ethnic relations, the YRB is a vibrant, diverse, and symbiotic zone where ethnic minorities coexist, mingling with one another despite residing in distinct areas and undergoing different development processes (Fu et al., 2021). Since the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the Han people have diffused into all parts of the basin along the Yuan River tributaries and main streams, forming large, dispersive residential patterns, creating small settlements, and assembling cross residences through national struggle and integration (Liu, 2008).

The marginal geographic location, diverse geographic environments, and complex ethnic relations have made the YRB the most densely populated region for traditional villages in China. The spatial distribution of traditional villages reflects the intricate interactions between ethnic groups in the YRB.

Data source

Since 2012, the Chinese government has designated villages with a long history, well-preserved material forms, and rich cultural heritage as “Chinese traditional villages” to ensure enhanced protection and preservation. By 2024, a total of 8155 villages will have been selected in six batches for inclusion in the list of Chinese traditional villages. We selected 826 traditional villages in the YRB from the list of six batches of Chinese traditional villages published by the Ministry of Housing and Urban‒Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China (https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/) in 2012–2023. Each village’s main ethnic information was collected from the Digital Museum of Traditional Villages in China (http://www.dmctv.cn/fy.aspx?lx=zt), the Digital Museum of Traditional Villages in Guizhou (https://webapp.xiaoheitech.cn/vizen-village-gz/index.html#/index), and the Digital Museum of Traditional Villages in Xiangxi. In the cases of multiethnic villages, ethnic attribution was defined by the main ethnic group with the largest population and most prominent cultural characteristics in a village. The geographical coordinates and elevation were acquired from the 91 Satellite Map Assistant Enterprise Edition (https://www.91wemap.com/index.htm).

The administrative boundary vector map, river system, and 30 m resolution DEM digital elevation data were obtained from the Resource and Environment Science and Data Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (https://www.resdc.cn).

Statistics on the YRB’s population, economy, urbanization rate, industrialization, and other relevant information were obtained from the 2022 Statistical Yearbook of Yunnan, Guizhou, and Hubei Province.

Research methods

(1) Nearest Neighbor Index. The nearest neighbor index (R) is a geographic indicator of the spatial proximity of point elements relative to each other. Since, at the macro-level, traditional villages can be viewed as point elements, R can explain the aggregation or dispersion of spatial data (Wu (2014)), which is expressed as follows:

where R represents the nearest neighbor index; r1 is the actual nearest neighbor distance of traditional villages; rE is the nearest neighbor distance; D represents the point density. When R = 1, the distribution of point elements is random; When R > 1, the point elements tend to be uniform; When R < 1, the point elements tend to be condensed.

(2) Geographical Concentration Index. This study uses the geographical concentration index to determine the degree of the spatial distribution of traditional villages in terms of aggregation. The formula is:

where Xi is the number of traditional villages in the ith county-level administrative region; T is the total number of traditional villages; N is the total number of county-level administrative regions. The value of G is between 0 and 100; the larger G is, the more concentrated the distribution of traditional villages among county-level administrative regions; conversely, the smaller G is, the more scattered the distribution of traditional villages is (Chen et al., 2023).

(3) Kernel Density Estimation (KDE). KDE is a graphical representation of the spatial clustering characteristics of traditional villages. It calculates the density of point elements around each output raster (Fischer and Getis, 2010). In this study, the spatial distribution density of traditional villages is measured by kernel density analysis. The formula is as follows:

where \(D\left({x}_{i},{y}_{i}\right)\) is the kernel density value at the location of the traditional village; r is the search radius, also known as the broadband (r > 0); u is the number of points whose distance from the location (\({x}_{i},{y}_{i}\)) is less than or equal to the search radius r; k is the kernel function that represents the spatial weights; and d is the distance between the current point element and points (\({x}_{i},{y}_{i}\)).

(4) Geodetector Analysis. Spatial differentiation is one of the most basic characteristics of geographical phenomena. Geodetector analysis is primarily used to detect spatial differences in geographical elements and analyze their driving forces (Wang and Xu, 2017). A fundamental presumption behind the central principle is that if an independent variable significantly affects a dependent variable, the spatial distributions of the independent and dependent variables will likely be comparable (Tao and Zhou, 2024). Geodetector analysis consists of four detector types. This paper uses two of those types: the factor detector and the interaction detector. The factor detector is used to determine if a factor affects how much a specific indicator value’s spatial differentiation varies. The interaction detector is used to identify interactions between different risk factors (i.e., assessing whether the independent variable factors X1 and X2 together increase or decrease the explanatory power of the dependent variable Y). The formula is:

where h = 1,…,L is the stratification of variable Y or factor X; Nh represents the number of units in layer h; Ν represents the number of units in the whole area; \({\sigma }_{h}^{2}\) and σ2 are the variances in the Y value in layer h and the whole area, respectively. The range of Y is from 0 to 1; q denotes the measure of the strength an influencing factor’s effect and takes a value between 0 and 1. The closer to 1, the greater the strength the influencing factor possesses.

Analysis and results

Spatial distribution characteristics of traditional villages

Type of spatial distribution

From a macro-regional perspective, the geographic location of traditional villages can be abstracted as point elements, and the spatial distribution types of those point elements can be divided into clustered, random, and dispersed groups. According to the Arcmap10.2 calculation (Fig. 2), the true shortest distance between traditional villages in the YRB was 0.078 degrees, while the theoretical shortest distance was 0.198 degrees. The nearest index R was 0.394, the Z value was −33.280, and the P value was 0. This indicated that the spatial distribution of the YRB’s traditional villages was a cohesion type. Spatial cohesion refers to the phenomenon where traditional villages are not evenly distributed but are clustered in specific areas, influenced by natural, economic, and cultural factors. The spatial cohesion of ethnic villages reflects ethnic differences in survival strategies, such as “living in clusters” and utilizing “territorial space”.

Geographical concentration

The nearest distance determines whether the distribution of traditional villages possesses agglomeration characteristics. However, the degree of agglomeration must be determined with the help of the geographic concentration index. Based on our calculation process, the geographic concentration index of traditional villages in the YRB was 57.03, significantly higher than the value of 16.49 observed under uniform distribution. The analysis revealed distinct regional agglomeration patterns, demonstrating that traditional villages in the YRB are significantly clustered in certain areas.

Spatial distribution density

Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) was used to quantitatively identify the geographic areas in which traditional villages in the YRB were clustered. A map of the density distributions was then generated (Fig. 3). The darker the color of the graph, the greater the number and density of traditional villages in the statistical unit. From the perspective of agglomeration structure, the distribution density of the traditional villages presented a spatial distribution pattern of “two cores, one belt, and multiple points”. The “two cores” consisted of the Miao settlement area in the Leigong mountains bordering the Leishan, Kaili, and Danzhai counties, and the Tujia settlement area in the Wuling mountains bordering the Huayuan, Jishou, and Guzhang counties. The “one belt” was upstream to the middle reaches of the Yuan River, inhabited by the Han, Dong, and Yao ethnic groups. The “multiple points” were the Xinhuang Dong Autonomous County, Tongdao Dong Autonomous County in Hunan province, the Liping County in Guizhou province, and the area in the middle reaches of the You River bordering Longshanshan, Youyang, and Baojing County. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Han Chinese entered the Yuan River basin on a large scale, while ethnic minorities retreated to the surrounding mountainous areas at relatively high altitudes. Minority groups in the mountainous areas have formed clusters, and due to a long history of geographic isolation, ethnic segregation, and underdeveloped economic conditions, they have managed to preserve their traditional ways of production and life. These minority villages are spatially divided into multiple settlements, exhibiting the structural characteristics of “multiple points,” which also reflect the spatial dynamics of multi-ethnic areas where various ethnic groups live intermingled. The traditional villages in this study are concentrated in the upper and middle reaches of the surrounding mountainous areas. This land is characterized by high slopes and closed geography, and includes the valley and hilly area between Hongjiang and Yuanling County in the middle reaches, and the river lake plain to the lower east of Yuanling County.

In terms of tributaries, the distribution density of traditional villages in the YRB decreases from the surrounding tributaries toward the central stream. The number of villages is relatively high along the You River in the northwestern part of the basin, the Xu River in the eastern part, and the Qu River in the southern part. However, the number of villages in the tributaries of the Wu River is comparatively low, with only the junction between Xinhuang and Yuping counties showing a relatively high concentration of villages, a phenomenon that warrants further exploration.

Ethnicity distribution

The spatial distribution of traditional villages in the YRB has obvious characteristics of ethnic agglomeration. Generally, the Han people live along the middle and lower reaches of the Yuan River’s central stream, while ethnic minorities inhabit the mountainous areas on the opposing sides (Fig. 4). The Tujia, an indigenous ethnic group in the YRB, are mainly concentrated in the Wuling Mountains in the northwestern part of the basin. This includes Longshan, Yongshun, and Baojing County. The Dong groups are scattered in the river valleys on both sides of the upper reaches and are more concentrated in Liping County, Tongdao County, and Xinhuang County. The Miao, who historically are a migrant ethnic group, are distributed throughout the YRB, forming two dense areas in the southwestern Leigong Mountains and the central Laer Mountains. Han Chinese have penetrated deeply into the Miao, Dong, and Tujia gathering areas along waterways, resulting in a high level of integration with other ethnic groups. The Tujia and Dong are not spatially intertwined, while the Miao intermingle with both. Although the ethnic groups are spatially interspersed, each has their own significant gathering areas and will likely remain spatially exclusive.

The darker the color, the greater the number and density of villages. a Tujia villages are mainly concentrated in the mountainous areas in the northwestern part of the basin; b Miao villages are mainly located in the mountainous areas in the southwestern part of the basin and in the central part of the basin; c Dong villages are mainly located in the low mountainous valley areas in the southern part of the basin; and d Han villages are mainly located in the flat areas of the middle and lower reaches of the main streams.

Geodetector-based identification of impact factors

The formation and distribution characteristics of the villages are clearly influenced by the geographic environment and socioeconomic factors. However, the level of influence of each factor, its mode of action, and its potential interactions with other factors in areas of ethnic integration have not yet been thoroughly explained. This is why we utilized a geodetector in our analysis.

Geodetector-based methods are statistical methods used for detecting spatial dissimilarity of geographical structures, thereby revealing their driving factors. At their cores, geodetector-based methods presuppose that if an independent variable (X) has a significant effect on a dependent variable (Y), the spatial distributions of both the independent and dependent variables should be similar. Assuming that the study area is divided into subregions, spatial heterogeneity can exist if the sum of the variances in the subregions is less than the total regional variance. Additionally, statistical correlation can exist between the two variables if their spatial distributions converge (Wang and Xu, 2017). A geodetector consists of four major sub-detectors. In our study, we primarily used factor detection to identify which factors had significant effects on the spatial distribution of traditional villages in the YRB. We also employed factor interaction analysis to identify which factors exhibited greater effectiveness when interacting with one another (Shi et al., 2022). Factor interaction evaluates whether the explanatory power of the spatial distribution of traditional villages increases or decreases when Influence Factor 1 and Influence Factor 2 act in combination.

However, when using geodetectors, the selection of influencing factors and the division of statistical units significantly impact the study’s results. In this research, we regarded the current distribution of traditional villages as the outcome of historical evolution. Influencing factors were selected by considering the different stages of formation, evolution, and retention of traditional villages. For statistical data, county-level administrative districts were used as the unit of analysis, considering both the accessibility of data and the importance of counties in China’s socioeconomic structure. This approach ensured the reliability of the research data. Thirteen indicators from three dimensions—natural environment, economy, and culture—were selected as influencing factors. Each indicator was typified or quantified based on its actual meaning. For example, the proportion of the ethnic minority population was calculated as the ratio of the ethnic minority population to the total population within the statistical unit. The neighborhood water ratio was defined as the ratio of villages within 3 km of major water systems to the total number of villages in the statistical unit. Quantitative metrics were discretized and transformed into categorical variables where necessary. The geodetector method was then applied to identify the primary influencing factors (Table 1), and the interaction forces among these factors were calculated (Table 2).

Based on the q-values and p-values in Table 1, we were able to determine that the 13 factors, the proportion of ethnic minorities, the number of minority populations (q-value of 0.215), the proportion of primary industry (q-value of 0.211), the average slope (q-value of 0.208), the rate of urbanization (q-value of 0.201), and the proportion of adjacent waterways (q-value of 0.201) had the greatest influence on the spatial distribution pattern of traditional villages in the YRB.

Among the natural factors, slope had the greatest influence on the distribution characteristics of villages. In the economic factors, the proportion of primary industry and the urbanization rate were the most influential, whereas the density of the road network and the total economic volume had a lesser impact. Among the cultural factors, the number of minority populations and the proportion of minority populations exerted the greatest influence.

With respect to factor interaction (Table 2), the explainability of the spatial distribution characteristics of villages improved significantly when interactions between factors were considered. For example, the interaction between “Density of water systems” and “Value added by primary industry” (as seen in Table 1) resulted in a q-value of 0.62. This was substantially higher than the explanatory power of any single factor, suggesting that the agricultural economy underpins the retention of traditional villages and that agricultural areas with rivers running through them are the primary locations for these villages. Similarly, the interaction between “Economic aggregate” and “Per capita disposable income” also led to a considerable increase in the q-value. When “Elevation factor” interacted with the “Number of minority populations” (Table 1), the q-value rose to 0.53, indicating that the explanatory power of the spatial distribution of traditional villages was enhanced by the combined effect of elevation and the minority population ratio. These findings demonstrate that the spatial distribution characteristics of traditional villages in the YRB are not determined by a single factor but result from the complex interplay of multiple factors. However, the geodetector analysis identified several individual factors as particularly significant: average slope, proportion of adjacent waterways, proportion of primary industry, urbanization rate, number of minority populations, and proportion of ethnic minorities. The specific mechanisms through which these factors influence the spatial distribution of traditional villages will be further explored below.

Analysis of influencing factors

Topographic slope

We found that, within the natural geographical environment, terrain and slope were the primary factors influencing human activities. After overlaying the distribution of the YRB’s traditional villages with the digital elevation model (DEM) of the basin, we discovered that all the high-density areas were located in mountainous areas with higher elevations and greater slopes. We also observed that traditional villages were more numerous in plains and hilly areas with gentler slopes (Fig. 5). The average elevation of the 826 villages was 576.32 m, with more than 55.8% of the villages being over 500 m and each displaying obvious mountainous pointing. Areas with large slopes have closed topography, low accessibility, few exchanges with the outside world, a low level of economic development, and few development and construction activities. The villagers’ reliance on the mountains is heightened, leading to the development of a vertical mountain agriculture model and a mountain-based belief culture, making it easier to preserve traditional production and living styles. On the other hand, river valleys and plains with gentle slopes feature flat terrain, abundant land, a strong agricultural base, convenient transportation, and active economic and cultural exchanges between villages and the outside world. These areas experience frequent village construction activities, making it difficult to maintain traditional production and living styles. As a result, traditional villages and dwellings are more prone to being demolished during the course of development. In terms of ethnicity (Fig. 6), different ethnic groups demonstrated different adaptations to terrain and slope (Fig. 7). The Miao villages had the highest elevation, with an average of 676.43 m, while the Dong villages had an average of 563.75 m, Tujia villages had an average of 514.61 m, and the Yao villages had an average of 460.83 m. The Han villages had the lowest elevation (346.97 m). This data revealed that mountainous areas with higher elevations and slopes are generally less accessible, less developed, and more likely to retain traditional villages.

Distance to water systems

Local water systems provide continuous power for the formation and development of traditional villages. Thus, the spatial distribution of traditional villages in the YRB must be water-oriented (Figs. 8, 9). The buffer zone analysis of the major rivers in the YRB revealed that 22.8% of villages are located within 300 m of rivers, 62.23% are within 3000 m, and 79.18% are within 50,00 m of rivers. Rivers not only provide essential water resources for village production and daily life but also create fertile cultivation areas along floodplains and impact plains. They serve as vital transportation routes for materials and facilitate ethnic migration. The influence of water systems on village distribution varies among ethnic groups. For instance, Dong villages are closely associated with water travel, while Miao villages are considered more “mountainous.” Statistics indicate that Dong villages account for 26.06% of those located within 300 m of a river, compared to only 16.71% for Miao villages. This disparity is linked to the historical reliance of the Dong on a rice-based economy and the Miao’s focus on dryland agriculture.

Distance to central city

After designating the county seat as our central location and establishing a buffer zone around it, we observed that the number of traditional villages decreased as the distance from the central city decreased (Fig. 10). Only 13.5% of the villages in our study group were located within 10 km of the central city, while nearly 50% were located more than 20 km from the central city. The number of traditional villages then decreased by about 20% for every 5 km closer to the central city. The closer a village is to a county, the greater the impact of the county’s radiation-driven economic activities. Without protective measures, traditional villages near cities are at high risk of disappearing in the wave of urbanization, leading to significant changes in their inherent production and living styles. Increased frequency of village construction further exacerbates the challenges in preserving traditional villages and their cultural heritage. Our study revealed that as the distance from the central city increases, a greater number of traditional villages are retained. Among the villages within 10 km of the central city, Miao and Tujia villages accounted for a relatively high percentage, while Dong and Yao villages were fewer. This phenomenon can be explained by the historical and social dynamics of these ethnic groups. The Tujia, as the indigenous people of the YRB, have historically maintained close ties with the central government. The Miao, who were once a migrant group, now primarily inhabit areas such as Laer Mountain and Leigong Mountain, where they have gradually established central towns. Conversely, the Dong and Yao peoples have retained their migratory lifestyles, resulting in smaller populations, more dispersed settlements, and a lack of agglomeration centers. With the implementation of the Chinese government’s rural revitalization strategy, villages in ethnic minority areas are poised to experience significant development opportunities. The unique economic and cultural value of traditional villages is being increasingly recognized. The central towns of the Miao and Dong ethnic groups are emerging as vital bridges connecting local traditions with global dynamics. The rural development model, which integrates culture and tourism, is expected to drive the growth of these central towns and promote broader regional development. However, while recognizing the opportunities brought by the economic growth and cultural revitalization of these central towns for the protection of traditional villages, it is equally important to address the potential negative impacts of central town expansion on surrounding traditional villages. Proactive measures must be taken to balance development and preservation, ensuring that the unique heritage of traditional villages is safeguarded amid economic and cultural progress.

Minority populations and cultures

After superimposing the proportions of ethnic minority populations and the numbers of traditional villages in each county (Fig. 11), we discovered a positive correlation between the two. The Leishan, Liping, and Taijiang counties boast the highest number of traditional villages and make up more than 90% of the minority population. Counties with more than 30 traditional villages have an average proportion of 81.35% minority members. Districts and counties with fewer than 10 traditional villages have a minority population of less than 50%. Generally speaking, minority villages located in mountainous areas have successfully preserved their original tangible and intangible cultural heritage, as well as their relatively simple village appearance. Traditional village appearance and ethnic culture are considered primary indicators of whether a village can be selected for the “List of Traditional Villages of China”. Thus, areas with a dense population of ethnic minorities and a strong preservation of ethnic culture have many traditional villages.

Economic development

The spatial distribution characteristics of traditional villages in the YRB showed a negative correlation with county economic development (Table 3). Based on the economic statistics of counties with varying numbers of traditional villages, we found that counties with a higher number of traditional villages tend to have a higher proportion of primary industries, a lower urbanization rate, and a lower per capita GDP. The urbanization rate and per capita GDP of districts and counties with more than 15 traditional villages were lower than the average watershed level. Economic development and urbanization have negatively impacted the retention of traditional villages. In contrast, areas with backward economic conditions, low urbanization levels, and a predominance of agricultural activities, coupled with weak economic development and minimal external influence, have facilitated the preservation of traditional landscapes, residential styles, and cultural heritage in villages. This has objectively facilitated the preservation of traditional villages. However, in economically developed areas with convenient transportation and frequent urban and rural construction activities, the loss of national culture, village texture, and traditional architectural features poses a significant threat.

Discussion and conclusions

Discussion

Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors are the foundation for the protection, development, and utilization of traditional villages. This paper adopts a watershed perspective, breaking free from the limitations imposed by administrative divisions, and scientifically reveals the regional characteristics of various ethnic traditional villages. Unlike previous qualitative inferences (Fang et al., 2023), this study utilized a geodetector to quantitatively assess the levels of influence exerted by various factors on the spatial distribution characteristics of traditional villages. Specifically, we focused on understanding the intricate mechanisms of influencing factors and their interactions. While previous studies identified local topography and water systems as the primary factors affecting the spatial distribution of traditional villages (Chen et al., 2018), our study reveals that the population and percentage of ethnic minorities are the most significant factors. The value of ethnic minorities and their cultures in village development is increasingly being recognized (Katapidi, 2021). As a representative of China’s ethnic minority areas, the Yuan River Basin is undergoing the impacts of urbanization and modernization. Although this paper uses the Yuan River Basin as a case study, traditional villages, as historical relics of the agricultural era, share similar generative backgrounds. The spatial distribution patterns and developmental trajectories of traditional villages in other regions are also influenced by the three major categories and 13 subcategories of factors proposed in this paper. Other rural areas, particularly ethnic minority regions, can draw upon the findings of this study when formulating strategies for the protection and development of traditional villages. First, given the “clustered” spatial distribution of traditional villages in the Yuan River Basin, a centralized and contiguous protection strategy should be implemented through policy measures. For instance, centralized and contiguous protection zones for traditional villages of various ethnic groups should be delineated. Within these zones, protection laws and regulations should be improved to safeguard material forms, building materials, and historical features. Second, considering the impact of urbanization and modernization on traditional villages, future village development should not only actively leverage external resources, technology, personnel, and materials to provide financial and technical support for the protection and utilization of traditional villages but also mitigate the negative effects of foreign influences on ethnic minority areas. Particular attention should be paid to reducing the impact of modernization on minority cultures to preserve the diversity of residential and cultural traditions. Finally, conservation should be promoted through utilization. In the Yuan River Basin, cultural resources can be integrated in a linear manner along historical post routes, water systems, and ethnic migration corridors. Ethnic minority-inspired cultural and tourism products can be developed to address the issue of insufficient funding for traditional village protection.

Conclusion

-

(1)

The spatial distribution of traditional villages in the YRB exhibited a “two cores, one belt, and multiple points” pattern that was concentrated in the Leigong Mountain and Wuling Mountain areas, with less distribution in the hills and downstream plains.

-

(2)

The spatial distribution of traditional villages is significantly influenced by the presence of ethnic minorities, with distinct distribution cores forming over time through ethnic struggle, integration, and development. Miao villages are concentrated in the Leigong Mountain area in the southwestern part of the basin, Tujia villages are located in the Wuling Mountain area in the northwestern part, Dong villages are primarily found in the river valleys along the tributaries in the southern part, and Han Chinese villages are mainly distributed in the hilly and plain areas, characterized by flat terrain and well-developed economies.

-

(3)

The geodetector analysis revealed that the factors most significantly influencing the spatial distribution characteristics of the YRB’s traditional villages were, in descending order of strength: the number of minority populations, the proportion of minority populations, the proportion of primary industries, the topographic slope, the urbanization rate, and the proportion of adjacent waterways. Additionally, the number of minority populations, the proportion of minority populations, the proportion of primary industries, the topographic slope, and the proportion of adjacent waterways were found to be positively correlated with the distribution of traditional villages. In contrast, the urbanization rate and per capita GDP were negatively correlated with the distribution of traditional villages.

-

(4)

Natural and economic factors were found to exert varying pressures on each ethnic group, effectively shaping the spatial distribution of their villages. The slope of the terrain influenced village locations by dividing them across different heights and gradients. The river water system affected how villages utilized water resources, with the Dong villages displaying a strong affinity for water and the Miao villages being more closely associated with mountainous areas. Urbanization levels influenced the relationship between traditional villages and cities; groups located closer to central cities had fewer traditional villages. On average, the Tujia and Miao villages were situated closer to urban centers, while the Dong and Yao villages were located farther away.

-

(5)

Factor interaction cross-detection found that the distribution pattern of traditional villages resulted from a combination of natural, economic, and social factors. The density of traditional villages was highest in mountainous areas, along steep slopes, and near rivers, particularly in regions densely populated by ethnic minorities and economically underdeveloped areas. Conversely, the density of traditional villages was lowest in plains and hilly regions near towns and cities, where the economy was well-developed, and the average per capita income level was high.

-

(6)

The spatial distribution pattern of traditional villages in the YRB evolved through three distinct periods: site selection, distribution evolution, and retention pattern. Natural, economic, and cultural factors played critical roles at each stage. Natural geographic factors predominantly influenced the early site selection and initial distribution of traditional villages. Over time, socioeconomic pressures led to constant adjustments and evolution in their spatial distribution. The economic level provided the material foundation and sustained momentum for the formation, development, and protection of these villages. However, development approaches that neglect the protection of traditional villages contribute to their decline in number. Ethnocultural factors significantly shaped the later patterns of village distribution. Traditional villages ultimately serve as a living inheritance of historical, cultural, and social values, with the production and living styles of ethnic minority populations and their unique customs infusing vitality into their development. Protecting these villages ensures that their distinctive cultural legacy continues to thrive amid modern challenges.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

References

Chen GL, Luo J, Zeng JX, Ye T, Ying D (2018) Spatial structure identification and influence mechanism of ethnic villages in China. Sci Geograph Sin 38(9):1422–1429

Chen WX, Yang LY, Wu JH, Wang GZ, Bian JJ, Zeng J, Liu ZL (2023) Spatial-temporal characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in the Yangtze River Basin: a geodetector model. Herit Sci 11:111

Ding C, Zhuo X, Xiao D (2024) Ethnic differentiation in the internal spatial configuration of vernacular dwellings in the multi-ethnic region in Xiangxi, China from the perspective of cultural diffusion. Herit Sci 12:3

Fang YL, Lu HY, Huang ZF, Zhu ZG (2023) Spatiotemporal distribution of Chinese traditional villages and its influencing factors. Econ Geogr 43(09):187–196

Fischer MM, Getis A (2010) Handbook of applied spatial analysis: software tools, methods and applications. Springer, Berlin

Fu J, Zhou J, Deng Y (2021) Heritage values of ancient vernacular residences in traditional villages in Western Hunan, China: spatial patterns and infuencing factors. Build Environ 188:107473

Gao WJ, Zhuo XL, Xiao DW (2024) Spatial patterns, factors, and ethnic differences: a study on ethnic minority villages in Yunnan, China. Heliyon 10(6):e27677

Hu T, Yang J, Li X, Gong P (2016) Mapping urban land use by using Landsat images and open social data. Remote Sens 8:151

Kang J, Zhang J, Hu H, Zhou J, Xiong J (2016) Analysis of spatial distribution characteristics of traditional villages in China. Prog Geogr 35(07):839–850

Karle S, Carman R (2020) Digital cultural heritage and rural landscapes: preserving the histories of landscape conservation in the United States. Built Herit 4(1):2–17

Katapidi I (2021) Heritage policy meets community praxis: widening conservation approaches in the traditional villages of central Greece. J Rural Stud 81:47–58

Li X, Chen DS, Xu WP, Chen HH, Li JJ, Mo F (2023) Explainable dimensionality reduction (XDR) to unbox AI ‘black box’ models: a study of AI perspectives on the ethnic styles of village dwellings. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:35

Liu S (2008) Western Hunan dwellings. China Construction Industry Press, Beijing

Long B, Zhao Y (2022) Study on the spatial distribution of national traditional villages and their influencing factors in Yunnan Province. Small Town Constr 40(02):29–39

Lu YD (2007) Fifty years of research on Chinese folk houses. Archit J 11:66–69

Luo YS (2010) The economic development and social change in Yangjiang River Basin during Ming and Qing Dynasty. Wuhan Uivisity Press, Wuhan

Ma Y, Zhang QL, Huang LY (2024) Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in Fujian Province, China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:883

Shi JH, Jin R, Zhu WH (2022) Quantification of effects of natural geographical factors and landscape patterns on non-point source pollution in watershed based on geodetector: Burhatong River Basin, Northeast China as an example. Chin Geograp Sci 32:707–723

Sun Y, Wang YH, Huang C, Tan RH, Cai JH (2023) Measuring farmers’ sustainable livelihood resilience in the context of poverty alleviation: a case study from Fugong County, China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:75

Tao H, Zhou J (2024) Study on the geographic distribution and influencing factors of Dai settlements in Yunnan based on geodetector. Sci Rep. 14:8948

Tao W, Chen HY, Lin JY (2013) Spatial form and spatial cognition of traditional village in syntactical view. Acta Geograph Sin 68(2):209–218

Wang JF, Xu CD (2017) Geodetector: principle and prospective. Acta Geograph Sin 72(1):116–134

Wen BH, Yang QX, Peng F, Liang LH, Wu SH, Xu F (2023) Evolutionary mechanism of vernacular architecture in the context of urbanization: evidence from southern Hebei, China. Habitat Int 137:102814

Wu C, Chen M, Zhou L, Liang X, Wang W (2020) Identifying the spatiotemporal patterns of traditional villages in China: a multiscale perspective. Land 9(11):449

Wu F (2014) Fundamentals of geographic information systems. Wuhan University Press, Wuhan

Wu KH, Su WC, Ye SA, Cao Y, Jia ZZ (2023) Analysis on the geographical pattern and driving force of traditional villages based on GIS and geodetector: a case study of Guizhou, China. Sci Rep. 13:20659

Xiang YL, Cao MM, Qin Jin, Wu C (2020) Study of traditional rural settlements landscape genetic variability in Shaanxi Province based on accurate-restoration. Prog Geogr 39(9):1544–1556

Yang K, Rui Y, Li YF, Yang YH (2021) Revitalization type subdivision of characteristic protection villages in China based on the symbiosis theory. Prog Geogr 40(11):1861–1875

Zhang B, Zhang R, Jiang G, Cai W, Su K (2023) Improvement in the quality of living environment with mixed land use of rural settlements: a case study of 18 villages in Hebei, China. Appl Geogr 157:103016

Zheng X, Jin XL, Hu XJ (2009) Research on public association space in traditional rural settlement. Econ Geogr 29(05):823–826

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Special Funds for Science and Technology Talent Introduction of Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (R2022YJ-YB3016), Guangdong Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (Grant No. GD25YGG32), and it was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52268003,52408022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CD: full text writing, collated and collected relevant data, and made tables for explanation, data analysis, and visualization; YZ: Writing-review and editing, funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, C., Zhao, Y. Spatial patterns, factor identification, and ethnic differences: a study of traditional villages in the Yuan River Basin based on geographical detectors. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 939 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05269-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05269-x