Abstract

In today’s pluralistic society, cross-disciplinary career transitions are critical for adapting to ever-changing job demands. Important influencing factors have been identified to explain these transition actions. However, studies on the prevalence of career transitions in different disciplinary areas are rare, especially those investigating the patterns of disciplinary changes accompanied by career transitions. This study applies text mining techniques, presenting data to demonstrate and compare how career transition exists widely across various disciplines. Taking library science, linguistics, electronic engineering, and radiology as representative areas and extracting resume data from Indeed, the empirical study yields noteworthy findings: Overall, the prevalence of career transition exists, with patterns varying across disciplines, illuminating the necessity for developing more inclusive curriculums or career planning frameworks to accommodate diverse needs of the job market. From the dimension of major discipline, the permeation pattern of disciplines varies. Humanities and natural sciences typically extend to other target domains, social sciences exhibit significant permeability, while engineering sciences generally revert to the initial domain. From the sub-discipline dimension, disciplines closer to the initial discipline do not necessarily have a higher employment rate. Rankings of disciplinary interaction strength and employment probabilities have a notable rank-turbulence divergence spanning from 0.4 to 0.7; from the occupation dimension, occupations spanning across different disciplines are abundant in the job market; from the skill dimension, the representativeness of occupational skills varies both within and outside the initial disciplines. Discipline-specific skills in electronic engineering and linguistics exhibit high representativeness both within and outside the initial discipline, while soft skills rank high outside the initial discipline in library science and radiology. These findings indicate how individuals develop professionally throughout transitions between various disciplines, providing strategic guidance for policymakers to synchronize career transition policies with specific patterns of discipline change, thereby promoting interdisciplinary talent cultivation objectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Career transition, defined as a phase during which individuals alter objective career roles or subjective career orientation (Louis, 1980), has gained increased attention from the academic community (Sullivan and Al, 2021). When individuals encounter obstacles in a specific discipline, discovering valuable opportunities in other disciplines might facilitate enhanced prospects for their career advancement. For instance, although Edward Witten specialized in history at university, in the end he became a notable mathematician who grew up by borrowing physical books from the library. Consequently, it is important to understand the dynamics of career transitions between disciplines to improve the chances of unforeseen job matches and foster the professional development of job seekers in new directions.

Contemporary studies on interdisciplinary career transition encompass a diverse array of domains, involving psychology, education management, computer science, et al. They have concentrated on examining the mechanisms influencing transition decision-making (e.g., Jung et al., 2021; Zha et al., 2023; Hung et al., 2025), as well as exploring methods to enhance career planning services through recommending skills (e.g., Huang and Baker, 2021; Howison et al., 2024; Ghosh et al., 2020) or occupations (e.g., Yamashita et al., 2022; Pundir et al., 2024) in other disciplines. Nevertheless, they seldom prioritize examining the transition pattern from the perspective of the discipline itself, and the prevalence of career transitions across disciplines cannot be fully embodied. Although studies on career development have presented demographic trends within the labor force (e.g., Petrongolo and Ronchi, 2020; Purcell, 2000; Wrenn et al., 2015) and advancements in certain professional aspects (e.g., Arora et al., 2020; Abraham and Kearney, 2020), less is known about the extent to which disciplines differentiate during the process of career transition, wherein individuals engage in disciplines different from their educational backgrounds. There is a notable deficiency in comparative analyses of cross-disciplinary career transitions across various disciplinary areas.

Academic disciplines facilitate and constrain career transition patterns (Robertson and Alexander, 2024). This study examines career transitions by depicting the discipline differentiation in the job market, as evidenced by extensive online resume data. We regard career transition as a multifaceted phenomenon of discipline separation and elucidate it from a more dimensional, in-depth perspective. Considering four principal professional attributes: major discipline, sub-discipline, occupation, and skill, we delineate the disparities in job status between individuals employed within and outside their educational discipline backgrounds in four distinct dimensions. By comparing the discipline differentiation phenomenon among graduates from four representative disciplines: library science, electronic engineering, linguistics, and radiology, we comprehensively demonstrate and highlight the unique characteristics of career transition patterns in various disciplines. This study provides valuable insights for career seekers to discover new employment opportunities in alternative disciplines, for career planners in examining diverse career options that exceed employer expectations, and for educational institutions in formulating pedagogical strategies that effectively prepare students for successful cross-disciplinary career transitions.

Related studies

This section includes a brief literature review in regards of career development and career transition.

Research on career development

Current research on career development primarily involves detecting real-time demographic trends within the labor force and the evolving trajectory of employment positions. Dynamic changes in the demographic attributes of labor in a particular field can be effectively monitored through gathering data on labor’s demographic factors, including gender (e.g., Petrongolo and Ronchi, 2020; England et al., 2020), age (e.g., Purcell, 2000; Banerjee and Blau, 2016), and residence (e.g., Wrenn et al., 2015; Kandel and Newman, 2004) from massive employment data at multiple temporal intervals. We can thus analyze the demographic transition of a field by identifying abrupt changes or the overall evolving trend. For instance, Albanesi and Ayşegül (2018) noted that the significant disparity in unemployment rates across genders was evident in the 1960s but had vanished by 1980 across 19 OECD nations. Abraham and Kearney (2020) document the prevailing trend of population aging alongside fluctuations in employment rates in the United States.

Moreover, certain studies focus on examining the developmental status of a career by analyzing statistical dynamics in critical professional dimensions, including salary (e.g., Arora et al., 2020; Aun, 2020), employment probability (e.g., Abraham and Kearney, 2020; Doleac and Hansen, 2020), and industry sectors (e.g., De Vos et al., 2021). Trends in various occupational parameters can be studied by integrating different data sources. Arora et al. (2020) examine wage changes in the bidi business by integrating data from both the company survey and the Indian government’s yearly employment statistics. Doleac and Hansen (2020) examine the correlation between employment probability and criminal histories by employing data from demographic surveys and relevant policy literature.

Various methodologies have been utilized to examine the employment development in a certain country, population, or industry. However, most studies focus on examining specific aspects of career development within a single field, neglecting the necessity for comparative research among different fields. Our study compares specialized career transition characteristics across various disciplines. By adopting a comparison viewpoint, we can get insights that may not be apparent when focusing solely on a single field.

Research on career transition

Scholars have examined career transitions from the perspectives of transitions within the original field (e.g., Bufquin et al., 2021; Barthauer et al., 2020), transitions outside the original field (e.g., Tutkun and Görgüt, 2024; Lin et al., 2021), retirement (Ginting et al., 2022; de Subijana et al., 2020), career loss (Lent et al., 2023; Mahmoudi, 2023), women entering or leaving the workforce (Jogulu and Franken, 2023; Singh and Bhat, 2022), and transitions from employees to entrepreneurs (St-Jean and Duhamel, 2020; Tran et al., 2021).

Among career transitions outside the original field, there are transitions beyond the discipline in which individuals originally work. Prior research on interdisciplinary career transitions focuses on skills, occupations, and decision-making. From the perspective of skill, mining and analyzing online resume data to recommend necessary skills in other disciplines is the research focus (Huang and Baker, 2021; Howison et al., 2024; Ghosh et al., 2020). Deep learning models can prepare for career transitions with technical assistance in spotting skill gaps. For example, Ghosh et al. (2020) propose a novel nonlinear state-space model to represent transitions between job and skill co-occurrence, hence providing skill recommendations for career transition planning.

From the perspective of occupation, related research is concentrated on recommending occupations in other disciplines (Yamashita et al., 2022; Pundir et al., 2024). Neural Network Language Models, such as BERT and LSTM-RNN, have been frequently adopted in recent years for predicting future occupations. For example, Yamashita et al. (2022) propose a model, NAOMI, for predicting occupation sequence based on BERT embeddings of job titles. Pundir et al. (2024) combine Word2Vec and LSTM-RNN models to assess skill similarity and predict jobs.

From the perspective of decision-making, determining factors influencing the decision-making of individuals contemplating a career transition is the key focus (Sullivan and Al Ariss, 2021). Related studies predominantly employ surveys, such as questionnaires and in-depth interviews, to investigate the intricate processes and motivations behind career transitions. For instance, Räsänen et al. (2020) collect questionnaire data from school teachers to examine their turnover intentions. Jung et al. (2021) surveyed employees in five-star hotels to verify the effect of job insecurity on their intent to transition. In addition, big-data analysis is applied to investigate career transitions from resume databases for pattern mining. For example, Zha et al. (2023) present a framework to mine career transition patterns from resumes posted on LinkedIn. Hung et al. (2025) combine web scraping and machine learning techniques to discover career-changing patterns of chief executives that contribute to their success.

However, the current research on the interdisciplinary career rarely puts the emphasis on studying the transition pattern from the perspective of the discipline itself. Revealing and comparing distinctive transition patterns of various disciplines is vital for building discipline-based education and career planning policies that increase individuals’ capacity to boost their prospects of career. This study seeks to conduct a multi-dimensional illustration of the cross-disciplinary career transition in different initial disciplines, with a focus on revealing the disparity between the learned discipline and the discipline of professional work, so as to help employees understand the potential transition opportunities and skill gaps they may face when moving across disciplinary fields.

Overall, compared with the existing research, the innovative work of this study mainly manifests in the following aspects: (1) To answer the question of how prevalent the career transition is in a wide range, we take a comparative approach by demonstrating and comparing the career transition patterns across multiple disciplinary fields. Rather than looking just at general patterns in the labor market, we try to understand how career transitions vary by discipline and learn which dynamics are responsible for driving these differences; (2) we adopt a disciplinary lens on career transitions, emphasizing the wide disciplinary range of potential career paths beyond one’s initial background. Successful transition examples can demonstrate to students that their skills and knowledge are transferable to other disciplines, opening exciting career opportunities they had never considered.

Methodology

The framework for understanding the prevalence of cross-disciplinary career transitions in different disciplines is shown in Fig. 1. Specific details of the concrete work in each model are outlined as follows:

Resume data collection

The study integrates data from different reliable data sources, laying a solid foundation for the subsequent statistical resume analysis. We first extract resume data from Indeed (“Indeed resume”, 2023), a job search website that helps job seekers find and apply for job openings. Established in 2004, Indeed has become one of the most comprehensive global employment search websites, collecting job information in over 60 countries. Given the extensive collection of resumes and the diversity of searchable resume fields (e.g., educational institution, major, and skills), a number of research works (e.g., Yamashita et al., 2022; Skondras et al., 2023) have used it for collecting resumes. To collect resumes automatically, we adopt the web-scraping tool Selenium to extract resumes from Indeed between March and September 2023. We search resumes in the field of educational background with discipline-specific keywords, obtaining 10,103 resumes in library science, 11,990 resumes in electronic engineering, 21,434 resumes in radiology, and 14,140 resumes in linguistics.

These disciplines are selected because of their wide coverage, subject level, and data availability. Firstly, they can cover a comprehensive range of disciplines, considering the major disciplines of scientific study, including social sciences, engineering sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Secondly, the disciplines are assigned to the second-level category in the subject classification of Microsoft Academic Graph (MAG), which meets our requirement of studying career transitions at the level of subdiscipline. Thirdly, the number of resumes in some disciplines recorded by Indeed is relatively small during the investigation time, so they are excluded in case of introducing bias and affecting the accuracy of the analysis. We eventually locate the four disciplines with enough and comparable resumes in quantity, spanning from 10000 to 20000. The extracted resume information includes fields such as major, current job title, and professional skills.

To ensure consistency in the form of occupation titles across different resumes, the study requires the normalization of job titles using a standardized sample of occupation nouns. The standardized job title data, as well as salary data, are sourced from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) government website (“U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics”, 2023), in which statistics of 833 occupations for the year 2022 are used for reference. As a principal unit of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, BLS provides official statistical data that can accurately reflect the economic situation of various career industries.

The study requires mapping job titles to specialties in the disciplinary classification system for understanding the disciplinary distribution of occupations during the career transition. Considering the comprehensive and hierarchical disciplinary classification provided by the internationally recognized academic dataset MAG, we use its journal classification system, which comprises 284 secondary disciplines, as the benchmark to ascertain the disciplinary orientation of occupations.

As seen from the section “Calculating the discipline distance”, measuring disciplinary distance requires quantifying the interaction strength between different disciplines based on direct citations between them. The citation relationship is obtained using the citation data of 10,010,147 articles during 2021–2022 from OpenAlex (https://openalex.org), which is fundamentally based on MAG. MAG incorporates multiple tiers of discipline labels into each article hierarchically, facilitating the extraction of recent citation links across the four examined disciplines.

Resume data processing

Before extracting occupation information from resumes, we need to perform the following necessary pre-processing steps to ensure the data quality, including resume data cleaning, occupation name annotation, occupation discipline annotation, and occupation skill normalization.

Resume data cleaning

As the job title serves as the foundation for correlating all pertinent employment information, it is essential to remove records with the job title field containing 0 values, empty values, or incorrectly encoded data after crawling resumes from Indeed. Furthermore, we exclude names of cities, states, and countries that appear together with job titles. Generic job titles like student, teacher, and expert are also excluded. Ultimately, we obtain 8679 valid records for library science, 9652 for electronic engineering, 13,462 for linguistics, and 19,966 for radiology.

Occupation name annotation based on ChatGPT

This step aims to annotate the specific occupational name to which an occupation belongs. With the rapid development of information technology, text annotation has become an important task in the field of natural language processing. Approaches for its implementation include methods based on dictionaries, rules, machine learning, and deep learning (Nasar et al., 2021). However, there is a lack of large annotated corpora dedicated to occupational names. Most of them focus more on biomedical applications (Perera et al., 2020), which hinders the standardization of occupational names with conventional ways. Given that large language models have already been broadly used and proved their effectiveness in text annotation tasks, such as labeling conceptual categories to tweets (Gilardi et al., 2023) and categorizing satellite images (Beck et al., 2025), we leverage the powerful language comprehension and generalization capacity of ChatGPT (Ogrinc et al., 2024) to well extrapolate the standardized occupation name for unstandardized samples. Also, by aligning with the internationally recognized standard list of occupation titles, we can use ChatGPT to restrict results to a more exact spectrum.

This step presents the occupational subcategories list provided by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, which contains 833 occupation names, as a standard for occupation labeling. ChatGPT is instructed to select the occupational subcategory to which a given occupation belongs from the provided list. Drawing from relevant research and practical experience in instructional engineering (Lu et al., 2024; Mialon et al., 2023; Nextra, 2023), the prompt used to query for a response from ChatGPT contains the following elements: role-setting, task description, and output style. Among them, role-setting refers to the implementation intention of the instruction (It is now necessary to identify the occupation category to which the given occupation tends to belong), task description represents the specific implementation content of the instruction (Please select the most appropriate occupation from * that the occupation “+text + “ belongs to), output style represents the expected format of the output response (Please reply only with the name of the occupation category without including any other additional information).

Ultimately, the prompt is set up as follows: It is now necessary to annotate the occupation category to which the given occupation tends to belong. Please select the most appropriate occupation from the provided list of occupational subcategories that the occupation “+text + ” belongs to. Please reply only with the name of the occupation category without including any other additional information, where * represents the list of standard occupational subcategories and “+text + ” represents the occupation name that needs to be standardized.

We evaluate the validity of ChatGPT on occupation annotation on a comparative task: comparing the annotation results of ChatGPT and human experts. Firstly, we randomly select 100 occupations that have been annotated in each disciplinary area. Secondly, the annotated name of each occupation is verified independently by two experienced researchers, reaching an acceptable level of consistency (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.42). Through dividing the average number of verified occupations by the total number of occupations (100), the accuracy of annotation results in each discipline can be demonstrated in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, the accuracy in each discipline ranges from 89 to 96%, mostly exceeding 90%. Overall, the validation confirms the robustness of ChatGPT in occupation name annotation.

Occupation discipline annotation based on ChatGPT

This step aims to annotate the specific discipline area to which an occupation belongs. We select the 284 sub-disciplines within MAG as the standard list and guide ChatGPT to select the most relevant discipline for the given occupation. The prompt is set up following the steps used in 3.2.2. Similarly, ChatGPT is asked to reply only with the name of the discipline without including any other additional information.

Occupational skill normalization

Normalization of the occupational skill presented by employees in their resumes is essential for subsequent quantitative skill assessments. Drawing on relevant studies (Gugnani et al., 2018; Dave et al., 2018; Li et al., 2017) on skill normalization, we implement the subsequent stages to normalize the skills listed in resumes, as shown in Fig. 2.

-

(1)

Skill grouping: Group skills that correspond to the same occupation name.

-

(2)

Skill Preprocessing: Filter punctuation marks, numbers, and stop words from the skill text, convert plural nouns to singular, and convert uppercase letters to lowercase.

-

(3)

Skill Filtering: Filter out skills that occur less than 10 times, for the purpose of enhancing the generalizability of the statistical results.

-

(4)

Skill Vectorizing: We use Document Frequency (TF-IDF) (Sparck, 1972) to measure the importance of words in text. In a resume, each word or phrase separated by commas under the skill column constitutes a skill representation (e.g., customer service or automotive repair). They can be considered a document storage skill. During vectorization, the occurrence of each word in different skill documents after deduplication forms its word vector. The dimension of the skill vector is the total number of words in all documents, and the weight of each word is its TF-IDF value. By summing the weighted vectors of each word in each document, the vector representation of the entire skill description can be obtained.

-

(5)

Skill Clustering: The vectorized representations of skill descriptions are clustered using agglomerative clustering (Randriamihamison et al., 2021). Agglomerative clustering is a type of hierarchical clustering algorithm that starts with each vector point as an individual cluster and progressively merges similar clusters to form the most similar clusters.

-

(6)

Manual Validation: While text training based on TF-IDF can cluster skills to some extent based on their importance in the text, it cannot cluster them according to the semantic similarity. Manual adjustment is needed to cluster skills with similar semantics but dissimilar word forms, and to separate skills with similar word forms but dissimilar semantics.

-

(7)

Skill replacing: To obtain the final normalized skill representation, the frequency of each skill appearing in all resumes is counted. Within a skill cluster, the most frequent representation is selected as the normalized skill representation. Then, each abnormal skill representation in the original resume is replaced with its corresponding normalized skill representation.

Resume data calculation

To quantitatively measure how careers in the targeted discipline are deviated from the initial discipline, we choose discipline distance, rank-based divergence, and discipline representativeness as indexes for assessing the deviation in the career’s major discipline, sub-discipline, occupation, and skill dimension, respectively.

Calculating the discipline distance

Disciplinary distance serves as an inverse indicator of the disciplinary interaction strength, measuring the divergence between the discipline belonging to employees’ occupations and their educational backgrounds. Given that citations can be a proxy for the diffusion of cross-disciplinary innovation (Zhai et al., 2018), we adopt the method proposed by Huang et al. (2022) to assess the intensity of cross-disciplinary interactions through direct literature citations. The method uses Jaccard similarity to measure cross-disciplinary interaction strength due to its simplicity and efficacy in quantifying robust connections between large datasets compared to other conventional similarity computation techniques (such as Euclidean and Manhattan) (Le and Phuong, 2020).

Figure 3 illustrates the principle of calculating disciplinary distance based on direct citations between Discipline X and Y, which can be classified into two categories: references belonging to Discipline Y cited by X, and references belonging to Discipline X cited by Y. In Fig. 2, these are designated as boxes that are shaded with a gray color. According to the principle of Jaccard, the interaction strength between X and Y is calculated as the intersection of the two citation datasets divided by their union. In the context of cross-disciplinary citations, we consider the minimum number of direct citations between X and Y as the numerator, while the denominator is the sum of the citation datasets of X and Y, excluding self-citations. \(I{I}_{{XY}}\), which represents the interdisciplinary interaction between Discipline X and Discipline Y, can be calculated as:

where \({C}_{{XY}}\) represents the number of articles in Discipline X citing articles in Discipline Y (X Cites Y, CXY), \({C}_{{YX}}\) represents the number of articles in Discipline Y citing articles in Discipline X (Y Cites X, CYX), \({C}_{X{\prime} }\) represents the number of articles in Discipline X citing articles in disciplines other than Discipline X, \({C}_{Y{\prime} }\) represents the number of articles in Discipline Y citing articles in disciplines other than Y.

Comparing the discipline based on rank-based divergence

While disciplinary distance allows for an individual assessment of the divergence between one’s educational discipline and career, it is also essential to examine the extent to which the entire employment landscape deviates from the anticipated academic framework. In the context of career transition, target disciplines sorted by the theoretical interaction strength and employment probability naturally form two ranked lists, each possessing a quantifiable and rankable value. In reference to the study of Dodds et al. (2023), the rank-turbulence divergence, an adjustable tool for comparing any two ranked lists, can be used to quantitatively assess the divergence state where practical and expected employment scenarios differ due to variations in the overall rank ordering of target disciplines.

Rank-turbulence divergence can be visualized in detail using a co-axis heterogeneity plot, highlighting significant changes in divergent or convergent states. The divergence between the two ranking systems can be calculated as:

where \({R}_{1}\) and \({R}_{2}\) represent rankings of the practical employment probability and disciplinary interaction strength, respectively. Values of disciplines in the two systems are ranked in descending order as \({r}_{\tau ,1}\), \({r}_{\tau ,2}\), and the number of disciplines in the two systems are respectively represented by \({N}_{1}\) and \({N}_{1}\). In addition, \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\) (0 ≤ α ≤ ∞) is a parameter used to adjust the weight of the contribution of high-ranking and low-ranking individuals to the ranking divergence. According to Zipf’s law, the ranking of an individual is inversely proportional to its numerical value. Based on this, the divergence of an individual based on ranking changes can be calculated as the reciprocal of its rank, which is\(\left|\frac{1}{\left[{r}_{\tau ,1}\right]}-\frac{1}{\left[{r}_{\tau ,2}\right]}\right|\). By introducing the parameter \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\), this expression can be adjusted to \({\left|\frac{1}{{\left[{r}_{\tau ,1}\right]}^{\alpha }}-\frac{1}{{\left[{r}_{\tau ,2}\right]}^{\alpha }}\right|}^{\frac{1}{\alpha }}\). As \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\) approaches 0, the ranking divergence decreases, and low-ranking individuals contribute more to the system’s divergence.

Calculating the discipline representativeness of skills

To assess the prevalence of career transition regarding occupational skill, we consider three indicators proposed by Cao et al. (2023). These indicators are employed to compare the representativeness of skills for the employees’ background and occupational discipline as follows:

-

(1)

Skill importance

Skill Importance (Importance in a Discipline, ID) quantifies the significance of a specific skill in characterizing the employment content of a disciplinary field, measured by its frequency of occurrence within that specific discipline as follows:

$${ID}\left(m,n\right)=\frac{{frequency}(m,n)}{{frequency}({all},n)}$$(4)where \({frequency}(m,n)\) represents the frequency of skill m in a certain discipline n, and\({frequency}({all},n)\) is the total frequency of all skills in discipline n.

-

(2)

Skill relevance

Skill Relevance (Relevance to a Discipline, RD) denotes the extent of association between a specific skill and a particular discipline. We assume that a skill’s higher proportion within a discipline correlates with its enhanced relevance to that field. The relevance of skill m to discipline n is calculated as follows:

$${RD}\left(m,n\right)=\frac{{frequency}(m,n)}{{frequency}(m,{all})}$$(5)where \({frequency}(m,n)\) is the frequency of skill m in a certain discipline n, and \({frequency}(m,{all})\) is the total frequency of skill m in all disciplines.

-

(3)

Skill discrimination

Skill Discrimination (Discrimination in a Discipline, DD) reflects the extent to which a skill can demonstrate the unique characteristics of a discipline. The discrimination of skill m in discipline n is calculated as follows:

$${DD}\left(m,n\right)=\frac{\left(\frac{{frequency}\left(m,n\right)}{{frequency}\left({all},n\right)}\right)}{\left(\frac{{frequency}\left(m,{all}\right)-{frequency}\left(m,n\right)}{{frequency}\left({all},{all}\right)-{frequency}\left({all},n\right)}\right)}$$(6)where \({frequency}(m,n)\) is the frequency of skill m in a certain discipline n, \({frequency}\left({all},n\right)\) is the total frequency of all skills in discipline n, \({frequency}(m,{all})\) is the total frequency of skill m in all disciplines, \({frequency}\left({all},{all}\right)\) is the total frequency of all skills in all disciplines.

-

(4)

Calculate the discipline representativeness of skills

The discipline representativeness score of a skill m (Score, \({S}_{\left({skill},m\right)}\)) is calculated based on the three indicators above, as shown in the following formula:

where \(\overline{{ID}\left(m,n\right)}\), \(\overline{{RD}\left(m,n\right)}\), and \(\overline{{DD}(m,n)}\) represent the normalized value of importance, relevance, and discrimination of skill n in discipline m.

To mitigate the impact of varying scales on indicator values, all indicators need to be normalized to objectively assess the discipline representativeness of a skill. Considering that linear normalization can effectively mitigate the impact of outliers on data analysis (Muhamedyev, 2015), the following formula is employed to linearly normalize the three indicators of discipline representativeness:

where \({X}_{{norm}}\) is the normalized value of an indicator, \({X}_{\min }\) is the minimum value of an indicator, and \({X}_{\max }\) is the maximum value of an indicator.

To compare key abilities of employees that enable them to contribute effectively before and after the career transition, we focus on changes in the discipline representativeness ranking of certain skill types, such as discipline-specific skills and soft skills. The discipline-specific skills can be thought of as skills that are unique to a discipline and can allow identifying the subject experts (Aliu et al., 2023). Soft skills refer to typically non-technical, interpersonal, behavioral characteristics aiding workers to collaborate with others and successfully operate in their environment (Dixon et al., 2010).

Comparing the salary within and outside the initial discipline

Comparing the salaries of individuals’ occupations within and outside of their initial discipline can assist individuals in evaluating the potential financial benefits of career transition by revealing the economic disparity between the preconceived and actual employment situation. Consequently, it is necessary to elucidate the salary discrepancy by calculating the weighted averages of salaries for employees within and outside the initial sub-discipline, respectively. The calculation formula is as follows:

where \(\bar{s}\) represents the weighted average of an occupation, \({w}_{j}\) represents the employment probability of the occupation j, which is regarded as the weight value of the occupation in this scenario.

Research results

The study categorizes first-level disciplines as major disciplines and regards secondary disciplines as branch units, also referred to as subdisciplines inside the major disciplines. A comprehensive analysis is undertaken by delineating disparities between anticipated and actual work scenarios across dimensions of major discipline, sub-discipline, occupation, and individual skill, thereby exploring the career transition from macro to micro dimensions. Disciplinary differences provide job seekers transitioning to a new area with a broad framework to consider, while differences in occupation and skill offer precise guidance on how to navigate the transition.

Analyzing career transitions in the dimension of major discipline

Career transition occurs when an employee shifts from the initial major discipline to the target occupational discipline (abbreviated as target major discipline). To provide broad directional guidance for students in choosing a working major discipline that aligns with the actual employment trend, we first examine the prevalence of career transition by comparing how the major discipline changes before and after graduates enter the workforce.

We use the ForceAtlas2 layout in the network analysis software Gephi to visualize the distribution of target major disciplines derived from the sub-disciplines of library science (LS), electronic engineering (EE), linguistics (LN), and radiology (RA), corresponding to the major disciplines: social sciences, engineering sciences, humanities, and natural sciences, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4a–d, the largest circle at the center of each graph represents the initial sub-discipline, pointing to the dense small circles representing target sub-disciplines, indicating the prevalent trend of graduates pursuing careers outside their initial discipline. The colors orange, green, pink, and blue signify the major disciplines corresponding to the respective sub-disciplines represented by the circles: social sciences, engineering sciences, humanities and natural sciences. On a 1:10 scale, the distance between the focal and surrounding circles represents the distance between the initial and target sub-disciplines in each graph, while the size of the circles represents the relative employment probability in different sub-disciplines.

The largest circle at the center of each graph in a–d represents the initial sub-discipline, while the small circles around represent target sub-disciplines. a The target discipline distribution in LS. b The target discipline distribution in EE. c The target discipline distribution in LN. d The target Discipline Distribution in RA.

As shown in the figure, the phenomenon of career transition can be commonly observed in various initial disciplines, while most employees still work within their initial disciplines. Graduated from the initial disciplines of library science, electronic engineering, linguistics, and radiology, employees have entered 133, 135, 153, and 131 disciplines, respectively, spanning across different major disciplines. The proportions of employees remaining in their initial disciplines are 36.44%, 25.15%, 21.12%, and 20.91%, respectively. Comparatively, the proportion of employees remaining in their initial disciplines is smaller for those with initial disciplines in linguistics and radiology, whereas it is larger for those with initial disciplines in electronic engineering and library science.

In this section, we treat the phenomenon of employees transitioning across different major disciplines as a mutual permeation process of different major disciplines. As shown in Table 2, squares in rows corresponding to humanities and natural sciences are generally darker compared to squares in other disciplines, indicating a higher number of individuals from these domains entering others. Comparatively, squares in columns of other disciplines corresponding to humanities and natural sciences are less dark in color, suggesting other major disciplines have a lower proportion of employees making transitions into humanities and natural sciences. Overall, the humanities and natural sciences tend to permeate outside domains in an expanding trend.

It can also be observed that social sciences show a high penetration power, with a large portion of employees working inside and outside of the initial major discipline. Engineering sciences show more employees working inside the initial domain but fewer in other target major disciplines, indicating a transition trend flowing back to the initial major discipline.

Humanities and natural sciences, as foundational disciplines examining essential principles of human growth, typically provide support for the advancement of other disciplines (Sala, 2013). This may lead to a large proportion of employees transitioning to external disciplines. Conversely, social sciences and engineering sciences are applied sciences that employ theoretical knowledge to address practical issues (Paunov et al.. 2017). As employees from foundational disciplines enter these disciplines, a growing number are arriving with employees working in social and engineering sciences. Although both social sciences and engineering are applied disciplines, the intrinsic interdisciplinary character of social sciences facilitates access for individuals from diverse backgrounds (Risjord, 2022). As a result, social sciences can not only retain employees working in the initial domain but also attract a substantial infusion of employees from other disciplines.

Analyzing career transition in the dimension of sub-discipline

Different disciplines sharing similarities in knowledge can often establish close connections. For example, the H-index, introduced by Jorge Hirsch in 2005 in physics, has found wide application in library science for evaluating the academic impact of scholars (Hirsch, 2005). To attain a profound comprehension of which specific disciplines within a broader field may yield unexpected employment opportunities, we examine the phenomenon from a fine-grained perspective of sub-discipline. We seek to determine whether employees are more inclined to pursue target sub-disciplines that are adjacent to the initial sub-discipline. A visual comparative study for rankings of the disciplinary interaction strength and practical employment probabilities is presented. To consider both the contribution of disciplines with higher and lower rankings to the overall ranking divergence, we adjust α to ensure that the top 50% of target disciplines contribute 50% of the total divergence contribution.

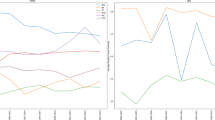

Figures 5–8 present the top disciplines in the ranking of employment probability and interaction strength for the four initial sub-disciplines. Each figure is divided into two graphs. In the left-hand graph, disciplines on either side of the central axis represent disciplines with higher rankings in the corresponding list. For instance, in Fig. 9, marketing is ranked 3rd in employment probability and 38th in interaction strength. Disciplines closely surrounding the central axis have minimal variation in ranking compared to those near square boundaries. Ranking shifts of a specific discipline can also be observed in the right-hand graph. The disciplines are ranked on the right according to the value of their divergence contribution.

The left graphs indicate that rank-turbulence divergences of all disciplines range from 0.4 to 0.7, following this sequence: library science (0.475) < linguistics (0.501) < electronic engineering (0.510) < radiology (0.656). The divergence values are all above 0.5 with relatively small differences, indicating that cross-disciplinary transition is a prevalent phenomenon that occurs in diverse disciplinary areas.

As seen from the ranking of divergence contributions in the right graphs, certain social science subjects consistently achieve high rankings. For example, business administration consistently scores first, and marketing remains within the top 15. These interdisciplinary sciences are associated with a wide range of career fields, aligning with prior research showing the social sciences’ strong penetration impact. Despite their remoteness from the initial sub-disciplines in theoretical research, they can still maintain high employment rates in practical employment scenarios.

Additionally, subdisciplines with higher divergence contributions are mostly closely associated with the initial subdisciplines in interaction strength. This might be owing to the growing interdisciplinary growth facilitated by technological innovation (Zhan et al., 2022). Contemporary careers directly associated with the initial discipline may also encompass roles from closely related disciplines. For example, academic librarians, categorized within library science, may also engage in analyzing big data for book management systems. This inclusion of data analysis responsibilities into librarianship diminishes the number of pure data science positions. Consequently, data science, which ranks second in interaction strength, only ranks 59th in employment probability, as shown in Fig. 6.

Analyzing career transitions in the dimension of occupation

Occupations denote specific responsibilities within the labor market. Understanding occupations with different discipline distances from the initial discipline is crucial for guiding employees to set concrete career objectives within broad discipline areas. To thoroughly delineate disparities between occupations in the initial and target disciplines, we fully examine professional parameters of disciplinary distance, employment probability, and salary to illustrate occupations in target disciplines of different distances. To ensure the representativeness of the examined occupations, we exclude occupations with fewer than 10 instances and finally obtain 131, 204, 213, and 146 occupations of employees who graduated from library science, linguistics, radiology, and electronic engineering, respectively.

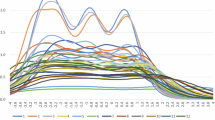

Bubble charts are utilized to visualize occupational distributions in three dimensions. As shown in Figs. 9–12, the size of each bubble represents the employment probability, while the vertical axis represents the annual salary and the horizontal axis represents the distance between the discipline of the occupation and its associated initial discipline. To ensure the clear visibility of occupations’ distribution patterns within the limited space, certain occupations that deviate significantly in terms of salary (e.g., radiologists, computer science professors, CEOs) have been removed from the original charts to avoid the overcrowding of most occupations.

Bubbles on the left are generally larger than those on the right, which shows a negative correlation between the probability of employment and disciplinary distance. Overall. Bubbles in the bottom left corner are comparatively larger, while the top left and right corners have more blank space. Furthermore, the peaks of the annual salary typically appear in the middle of the graph, while the bubbles in the bottom right corner are normally larger than those in the top right corner. This suggests that occupations closely aligned with employees’ educational backgrounds typically have higher employment probabilities but lower salary levels compared with more advanced occupations. The salary typically attains its optimum when the disciplinary distance grows to a certain extent, neither excessively close nor overly distant. When the target discipline diverges significantly from the initial discipline, occupations with lower salary levels often have a higher employment probability.

Comparing salaries of occupations within and outside the individuals’ initial sub-disciplines reveals that the average salary of external disciplines is generally higher than that of internal disciplines. Their weighted average differences are arranged in the following order: radiology (−17,259.20) < linguistics (11,080.03) < electronic engineering (14,578.30) < library science (24,412.28). In such instances, evaluated income incentives act as a substantial motivation for employees to pursue new domains. However, according to Nash equilibrium theory (Kreps, 1989), disciplinary distance and salary act as opposing factors in the pursuit of interest equilibrium. Although entering unfamiliar fields may yield lucrative career opportunities, learning costs are required for distant, high-paying occupations. Consequently, most distant occupations that employees undertake are those with relatively lower learning expenses, such as light truck drivers, customer service representatives, fast food and counter workers, et al.

Analyzing career transitions in the dimension of skill

Industries of different disciplines possess unique skill prerequisites. It is imperative to assist individuals in recognizing the necessary skills required for their chosen disciplines. In this section, the initial sub-discipline is regarded as a singular discipline, whereas all target sub-disciplines outside the corresponding initial sub-discipline are considered as another discipline. Utilizing the formula for assessing the discipline representativeness of skills in section “Calculating the discipline representativeness of skills”, we conduct an in-depth analysis of the disparity between skills within and outside the initial discipline.

As seen in Table 3, occupations in library science require discipline-specific skills in book classification, information resource description, and cataloging (e.g., Library of Congress Classification, Describing Archives: A Content Standard, and Dublin Core). Furthermore, they need to remain informed about emerging technologies and concepts (e.g., database management, information system management) to align with advancements in the digital information age.

Nonetheless, for occupations beyond library science, soft skills are prioritized over discipline-specific skills regarding the overall representativeness value. As employees often transition into finance and business management, they need to possess excellent business service skills (e.g., catering, housekeeping, and hotel reception). They also require robust communication skills (e.g., telemarketing) and business management skills (e.g., compliance management and business-to-business sales). By delivering superior services, employees can cultivate client trust in business activities, thereby achieving their goals for interdisciplinary career development (Ibourk and El Aynaoui, 2023).

Table 4 indicates that discipline-specific skills appear prominently in the ranking of electronic engineering (e.g., applying Altium Design Software, power supply design, electrical wiring). Practical engineering skills (e.g., maintenance technology, industrial electrician experience, and service technician experience) are also highly ranked. Electronic engineers need both solid professional knowledge and practical skills to effectively operate within the increasingly intricate and rapidly evolving technology industry.

Beyond electronic engineering, software proficiency (e.g., Waterfall), programming skills (e.g., deep learning, C + + language, Go language), and data analysis skills (e.g., data science, structured query language (SQL), data analytics) are crucial considering today’s increasing dependence on digital platforms in various industries. Besides, the terms customer service, cold calling, and business-to-business sales point out the necessity of sales capabilities for employees to efficiently interact with customers, address their technical inquiries, and foster robust customer relationships.

In linguistics, terminology such as computer-assisted translation tools, writing, and speech therapy signify that employee necessitate language skills in translation, communication, and writing. Besides theoretical knowledge of language, the ability to teach language skills proficiently to students is crucial, encompassing classroom management, literacy education, and lesson planning. Due to the large number of graduates pursuing careers in education, applying effective teaching skills becomes important in this area, which can enhance the effectiveness of their language instruction (Table 5).

Outside the field of linguistics, terminology associated with fundamental language competences such as English, writing, and linguist experience still rank within the top 20. It appears that language proficiency remains essential for employees in diverse fields. No matter if they are communicating, writing documents, or running marketing campaigns, good language skills enable them to convey themselves properly. Additionally, since employees commonly work in clerical tasks, office skills, such as applying Microsoft Office and data entry, are also urgently needed (Table 5).

In radiology, discipline-specific skills are highly demanded, as shown in Table 6. Gaining entrance to the field requires certification from the American Registry of Radiologic Technologists (ARRT). Additionally, an understanding of anatomy, medical imaging, and other professional knowledge enables more accurate diagnosis and superior healthcare treatments for patients.

Apart from radiology, employees move to various basic service industries. Hence, in the top 20 are terms like food service, customer service, plumbing, etc. Terms like dental assisting and Eaglesoft dental practice management software reflect how employees can combine their expertise with dental care knowledge to serve the oral health industry. For instance, newly developed radiological technologies, including dental lasers and 3D printing, greatly enhance the dental treatment circumstances for patients.

Discussion

This study examines career transitions by comparing the prevalence of transitions in different disciplinary fields. It transforms the traditional demographic trend or trends surrounding professional aspects into a multi-dimensional disciplinary analysis, which dives more into the characteristics of disciplines amid transition trends. Taking library science, electronic engineering, linguistics, and radiology as sample disciplines, we investigate distinctions in major discipline, sub-discipline, occupation, and skill between employees within and outside their respective background disciplines. Differences within disciplines provide macroscopic directions to job seekers transitioning to a new area, whereas variations in occupation and skill offer concrete instructions for executing the transition. Results of the empirical study indicate plenty of valuable findings.

First, there exists a prevalent discrepancy concerning the major discipline of education backgrounds and professional occupations among employees who graduated from various disciplinary areas. When it comes to the penetration of major disciplines into other major disciplines, the humanities and natural sciences typically diffuse from the initial discipline to other target disciplines. Social sciences demonstrate strong permeability, with mutual diffusion between the initial and target disciplines. Engineering sciences tend to converge back into the initial discipline. This suggests that employees in the humanities and sciences have a stronger potential for cross-disciplinary career transitions. They are advised to apply professional knowledge in the broad field, fitting with the job needs of diverse disciplines. The most accessible major discipline is social science. It is a recommended discipline for employees wishing to change job fields. Compared to other major disciplines, engineering sciences demand higher employment thresholds. Employees in this discipline are recommended to accumulate sufficient professional knowledge and industry experience to prevent losing their competitive advantages due to a career change.

Second, there is a noticeable discrepancy between the strength of cross-disciplinary interactions and the probability of practical employment. The overall divergence of discipline rankings demonstrates that all divergence values are above 0.5, exhibiting relatively little variance among them. Moreover, the ranking of divergence contributions indicates that certain subdisciplines of social sciences, such as business administration and marketing, consistently achieve high rankings. These interdisciplinary sciences might help them maintain high employment rates in practical employment scenarios. Additionally, disciplines closely related to the initial disciplines can also hold relatively high divergence contributions. This may be attributed to the growing comprehensiveness of the initial disciplines.

Third, there is a common difference between the predetermined and actual occupations. Occupations outside of the initial discipline span across the job market in different disciplinary areas. Although careers directly related to the initial discipline may provide greater feasibility and better employment chances, they usually come with rather lower salary levels. Through comparing salaries of occupations within and outside individuals’ initial sub-disciplines, we find that the average salary in external sub-disciplines is generally higher than in internal disciplines. Their weighted average difference follows this order: radiology (−17,259.20) < linguistics (11,080.03) < electronic engineering (14,578.30) < library science (24,412.28). Under these circumstances, payment incentives are quite motivating for employees to engage in new fields. On the other hand, occupations with lower salary levels usually have a higher employment probability when the target discipline is too far from the initial one. As a result, it is important to carefully consider how to balance the economic benefits and learning expenses before actually enrolling in a different discipline.

Ultimately, the representativeness of professional skills varies between within-discipline and outside-discipline contexts. Within their respective disciplines of library science and radiology, discipline-specific skills are highly valued. Soft skills, including customer reception, sales promotion, and office management, are more advantageous for employees achieving career expansion goals. In contrast, discipline-specific skills in electronic engineering and linguistics possess significant value both within and outside their respective disciplines. Additionally, across all disciplines, skills in big data analysis and customer service rank highly outside of the initial fields. As the information age progresses, both conventional and nascent industries encounter substantial data and intricate client requirements. Then, the capacity to thoroughly analyze big data and provide high-quality customer service has become increasingly crucial for employees pursuing career transfer opportunities.

Overall, the study provides disciplinary insights into multiple facets of the employment landscape. The findings address the prevalence of cross-disciplinary career transitions by comparing the multi-dimensional disparities in transition patterns across diverse disciplinary fields. From introducing the concept of disciplinary differentiation and illustrating it through vivid visual contrasts, we imply that the unique characteristics of disciplines can influence how employees make career transitions. It would be beneficial for career seekers to expand career horizons, for career planners to provide career transition guidance, and for educational institutions to develop teaching strategies that can support students in preparing for career transitions.

The prevalence of career transitions across different disciplines illuminates the necessity for educational institutions to develop more inclusive and flexible curriculum frameworks for accommodating the diverse demands of the job market. Considering the strong permeability of social science and the convergence of engineering, certain social science courses can be integrated into engineering curricula to enhance employment flexibility. For example, a group of Chinese engineering universities integrates Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) education into their educational frameworks to cultivate innovative engineers (Li and Liu, 2025). Specifically, subdisciplines ranking prominently in the contribution of rank-turbulence divergence, such as business administration and marketing, can be regarded as key subdisciplines for integrating into engineering.

In order to enhance the transition potential of employees by gaining necessary new skills, we also suggest career planners review the skill ranking list across different disciplines and systematically develop a cross-disciplinary skill framework into a sound system with skills that support and complement each other. For example, for students in social and natural science, the development of soft skills should be prioritized to enhance their employability in diverse fields. Conversely, students in engineering and linguistics ought to focus on enhancing discipline-specific skills while also exploring their applicability in alternative contexts. For general students, competencies in big data analysis and customer service are notable for their relevance across various disciplines. As the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into technical tasks escalates, soft human skills have become increasingly competitive for career transitions in this AI-driven era.

This study has limitations in terms of disciplinary diversity. Our preliminary results concentrate on four representative disciplinary fields. Further verification is needed to confirm the general applicability of our conclusions in other disciplines. Moving forward, we will continue to compare how various variables involved in the cross-disciplinary career transition vary in broader contexts. As the employment landscape varies greatly across regions, we would also like to incorporate a regional perspective to examine career dynamics, hence enhancing the customization of career strategies to align with different local contexts.

Data availability

The datasets generated by extracting resumes from Indeed during the current study are available in the Figshare repository, https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Raw_data-Resume_information_collection/26335024.

References

Abraham KG, Kearney MS (2020) Explaining the decline in the US employment-to-population ratio: a review of the evidence. J Econ Lit 58(3):585–643

Albanesi S, Ayşegül Ş (2018) The gender unemployment gap. Rev Econ Dyn 30:47–67

Aliu J, Aghimien D, Aigbavboa C et al. (2023) Empirical investigation of discipline-specific skills required for the employability of built environment graduates. Int J Constr Educ Res 19(4):460–479

Arora M, Datta P, Barman A et al. (2020) The Indian bidi industry: trends in employment and wage differentials. Front Public Health 8:572638

Aun LH (2020) Work and wages of Malaysia’s youth: structural trends and current challenges. Singapore: ISEAS 2020:98

Banerjee S, Blau D (2016) Employment trends by age in the United States: why are older workers different? J Hum Reinitials 51(1):163–199

Barthauer L, Kaucher P, Spurk D et al. (2020) Burnout and career (un) sustainability: Looking into the Blackbox of burnout triggered career turnover intentions. J Vocat Behav 117:103334

Beck J, Kemeter LM, Dürrbeck K et al. (2025) Towards integrating ChatGPT into satellite image annotation workflows. A comparison of label quality and costs of human and automated annotators. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing. IEEE

Bufquin D, Park JY, Back RM (2021) Employee work status, mental health, substance use, and career turnover intentions: an examination of restaurant employees during COVID-19. Int J Hospit Manag 93:102764

Cao YJ, Xiang RR, Mao J et al. (2023) Discipline identification methods for knowledge units: a comparative study towards feature mining. J China Soc Sci Tech Inf 42(10):1151–1165

Dave VS, Zhang B, Al Hasan et al. (2018) A combined representation learning approach for better job and skill recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, New York, NY, USA, October 22–26, 2018. pp. 1997–2005

De Vos, A, Jacobs S, Verbruggen M (2021) Career transitions and employability. J vocat behav 126:103475

de Subijana CL, Galatti L, Moreno R et al. (2020) Analysis of the athletic career and retirement depending on the type of sport: a comparison between individual and team sports. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(24):9265

Dixon J, Belnap C, Albrecht C et al. (2010) The importance of soft skills. Corp Financ Rev 14(6):35

Dodds PS, Minot JR, Arnold MV et al. (2023) Allotaxonometry and rank-turbulence divergence: a universal instrument for comparing complex systems. EPJ Data Sci 12(1):37

Doleac JL, Hansen B (2020) The unintended consequences of “ban the box”: statistical discrimination and employment outcomes when criminal histories are hidden. J Labor Econ 38(2):321–374

England P, Levine A, Mishel E (2020) Progress toward gender equality in the United States has slowed or stalled. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(13):6990–6997

Ghosh A, Woolf B, Zilberstein S et al. (2020, December) Skill-based career path modeling and recommendation. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). IEEE. pp. 1156–1165

Gilardi F, Alizadeh M, Kubli M (2023) ChatGPT outperforms crowd workers for text-annotation tasks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 120(30):e2305016120

Ginting S, Hartijasti Y, Rosnani T (2022) Analysis of the mediation role of career adaptability in the effect of retirement planning for attitude formation of retirement in credit union employees West Kalimantan. Int J Soc Sci Res Rev 5(4):214–228

Gugnani A, Kasireddy VKR, Ponnalagu K (2018) Generating unified candidate skill graph for career path recommendation. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), Singapore, Singapore, 17–20 November 2018. IEEE. pp. 328–333

Hirsch JE (2005) An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102(46):16569–16572

Howison M, Long J, Hastings JS (2024) Recommending career transitions to job seekers using earnings estimates, skills similarity, and occupational demand. Digit Gov Res Pract 5(3):1–19

Huang A, Baker M (2021) Exploring skill-based career transitions for entry-level hospitality and tourism workers. J Hospit Tour Manag 48:368–373

Huang L, Cai Y, Zhao E et al. (2022) Measuring the interdisciplinarity of Information and Library Science interactions using citation analysis and semantic analysis. Scientometrics 127(11):6733–6761

Hung CY, Jeng E, Cheng LC (2025) Analysis of CEO career patterns using machine learning: taking US university graduates as an example. Data Technol Appl 59(1):61–81

Ibourk A, El Aynaoui K (2023) Career trajectories of higher education graduates: impact of soft skills. Economies 11(7):198

Indeed resume (2023) Indeed. Retrieved from https://resumes.indeed.com/

Jogulu U, Franken E (2023) The career resilience of senior women managers: a cross‐cultural perspective. Gend Work Organ 30(1):280–300

Jung HS, Jung YS, Yoon HH (2021) COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. Int J Hospit Manag 92:102703

Kandel W, Newman C (2004) Rural Hispanics: employment and residential trends. Amber Waves: the Economics of Food, Farming, Natural Reinitials, and Rural America 2004:37–45

Kreps DM (1989) Game theory. Palgrave Macmillan UK, London, pp. 167–177

Le TTN, Phuong TVX (2020) Privacy preserving jaccard similarity by cloud-assisted for classification. Wirel Personal Commun 112(3):1875–1892

Lent RW, Wang RJ, Cygrymus ER et al. (2023) Navigating the multiple challenges of job loss: a career self-management perspective. J Vocat Behav 146:103927

Li M, Liu X (2025) Enhancing humanities and social sciences curriculum in engineering institutions by using interdisciplinary approaches. Cogent Educ 12(1):2433831

Li L, Jing H, Tong H et al. (2017) NEMO: Next career move prediction with contextual embedding. In: Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web Companion, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017. pp. 505–513

Lin Y, Hu Z, Danaee M et al. (2021) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on future nursing career turnover intention among nursing students. Risk management and healthcare policy. pp. 3605–3615

Louis MR (1980) Career transitions: varieties and commonalities. Acad Manag Rev 5(3):329–340

Lu W, Wang L, Cheng Q et al. (2024) A new approach for information reinitials management empowered by data intelligence: the concept, connotation and development of instruction engineering. Document Inf Knowl 41(1):6–11

Mahmoudi SE (2023) Late-career unemployment shocks, pension outcomes and unemployment insurance. J Public Econ 218:104751

Mialon G, Dessì R, Lomeli M et al. (2023) Augmented language models: a survey. Trans Mach Learn Res 2023

Muhamedyev R (2015) Machine learning methods: an overview. Comput Model N Technol 19(6):14–29

Nasar Z, Jaffry SW, Malik MK (2021) Named entity recognition and relation extraction: state-of-the-art. ACM Comput Surv (CSUR) 54(1):1–39

Nextra. Prompt Engineering Guide (2023) https://www.promptingguide.ai/. Accessed 10 Oct 2023

Ogrinc M, Koroušić Seljak B, Eftimov T (2024) Zero-shot evaluation of ChatGPT for food named-entity recognition and linking. Front Nutr 11:1429259

Paunov C, Planes-Satorra S, Moriguchi T (2017) What role for social sciences in innovation? Re-assessing how scientific disciplines contribute to different industries. OECD Science, Technology and Innovation Policy Papers. 45

Perera N, Dehmer M, Emmert-Streib F (2020) Named entity recognition and relation detection for biomedical information extraction. Front Cell Dev Biol 8:673

Petrongolo B, Ronchi M (2020) Gender gaps and the structure of local labor markets. Labour Econ 2020(64):101819

Pundir RS, Dhasmana A, Karakoti U et al. (2024, April) Enhancing resume recommendation system through skill-based similarity using deep learning models. In: 2024 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT). pp. 557–562. IEEE

Purcell PJ (2000) Older workers: employment and retirement trends. Monthly Lab Rev 123:19

Randriamihamison N, Vialaneix N, Neuvial P (2021) Applicability and interpretability of Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering with or without contiguity constraints. J Classification 38(2):363–389

Räsänen K, Pietarinen J, Pyhältö K et al. (2020) Why leave the teaching profession? A longitudinal approach to the prevalence and persistence of teacher turnover intentions. Soc Psychol Educ 23:837–859

Risjord M (2022) Philosophy of social science: a contemporary introduction. Routledge

Robertson PJ, Alexander R (2024) Special issue: disciplinary perspectives in career development. J Natl Inst Career Educ Counselling 52(1):3–9

Sala R (2013) One, two, or three cultures? Humanities versus the natural and social sciences in modern Germany. J Knowl Econ 4:83–97

Singh, Bhat (2022) Does workplace issues influence women career progression? A case of Indian airline industry. Res Transp Bus Manag 43:100699

Skondras P, Psaroudakis G, Zervas P et al. (2023, July) Efficient Resume Classification through Rapid Dataset Creation Using ChatGPT. In: 2023 14th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems & Applications (IISA). IEEE. pp. 1–5

Sparck JK (1972) A statistical interpretation of term specificity and its application in retrieval. J Document 28(1):11–21

St-Jean E, Duhamel M (2020) Employee work–life balance and work satisfaction: an empirical study of entrepreneurial career transition and intention across 70 different economies. Acad Rev Latinoam Admin 33(3/4):321–335

Sullivan SE, Al Ariss A (2021) Making sense of different perspectives on career transitions: A review and agenda for future research. Human Reinitial Manag Rev 31(1):100727

Tran H, Baruch Y, Bui HT (2021) On the way to self-employment: the dynamics of career mobility. Int J Hum Reinitial Manag 32(14):3088–3111

Tutkun E, Görgüt İ (2024) Career transitions of football players. Online J Recreat Sports 13(1):47–56

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2023) List of soc occupations. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_stru.htm. Accessed 15 Sept 2023

Wrenn DH, Kelsey TW, Jaenicke EC (2015) Resident vs. nonresident employment associated with Marcellus Shale development. Agric Reinitial Econ Rev 44(2):1–19

Yamashita M, Li Y, Tran T et al. (2022) Looking further into the future: career pathway prediction. WSDM Computational Jobs Marketplace

Zha R, Qin C, Zhang L et al. (2023) Career mobility analysis with uncertainty-aware graph autoencoders: a job title transition perspective. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst 11(1):1205–1215

Zhai Y, Ding Y, Wang F (2018) Measuring the diffusion of an innovation: a citation analysis. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol 69(3):368–379

Zhan Z, Shen W, Xu Z et al. (2022) A bibliometric analysis of the global landscape on STEM education (2004-2021): towards global distribution, subject integration, and research trends. Asia Pac J Innov Entrep 16(2):171–203

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province [grant number 2024A1515011778].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TZ wrote the article, participated in data curation and analysis, and visualized the results. CY participated in data curation and result visualization. DZ carried out formulating research conceptions and revising the original article. JX contributed to supervising, formulating the research framework, interpreting the results and revising the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The research does not involve human participants; therefore, ethical approval is not required.

Informed consent

The research does not include any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Yu, C., Zhang, D. et al. How prevalent is the cross-disciplinary career transition? Evidence from a multi-dimensional comparative analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 943 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05273-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05273-1