Abstract

Extreme weather events and disasters, coupled with aging and underfunded infrastructure, threaten critical systems like energy grids. Disruptions in these systems following disasters have cascading impacts on population health and well-being. By combining power outage, disaster, and social vulnerability information (2017–2022) at the county level in one of the most disaster-prone regions of the United States, the Gulf Coast, we created hierarchical Bayesian models to infer profiles of regions experiencing slower restoration following disasters such as tropical storms, heat waves, snowstorms, inter alia. Hurricanes/tropical storms and heat waves were associated with the longest outages regionally. We also estimated the 10 most and least vulnerable counties based on average outages, irrespective of specific hazards. Characterizing community profiles and key vulnerabilities to prolonged post-disaster energy insecurity is critical to prioritizing energy restoration, justice-oriented energy transition policies, and sociotechnical resilience in the region. Comparing observed and predicted outages and accounting for social vulnerabilities, these results can aid planning efforts in community and policy contexts across the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

From 2017 to 2021, the United States experienced 91 “billion-dollar disasters”—disasters that incur at least, if not more than, $1 billion in costs—resulting in more than 4500 preventable deaths and nearly $852.5 billion in damage (NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information [NCEI], 2024). Increased frequency and intensity of disasters, exacerbated by human-induced climate change and coupled with inequities in infrastructure investment, challenge critical energy systems, impacting millions of people who are dependent on them (Kenward and Raja, 2014; NOAA NCEI, 2024). Power outages, one among many impacts of these events, disrupt everyday life, including food and medication storage, clean water access, employment, and operation of life-support devices (Casey et al. 2020; Dargin and Mostafavi, 2020; Hernández, 2016; Mitsova et al. 2018).

Energy systems are sociotechnical, combining physical (distribution and transmission) structures with socioeconomic, organizational, and political structures to determine demand (Büscher, 2022; Cherp et al. 2018; Miller et al. 2015). Most transmission and distribution lines in the United States are aboveground and vulnerable to extreme weather (Kenward and Raja, 2014; Zamuda et al. 2023). For underground power lines, hurricanes and storm surges can lead to flooding and power outages. Before hazards strike, utilities often work to mitigate long-term power disruptions by using techniques such as rolling outages to prevent system demand from exceeding capacity, as was the case following Winter Storm Uri (2021) in Texas (Peterson et al. 2024). Following disasters, utilities make power restoration decisions based on the size of impacted populations. Government, public–private relations, culture, politics, resources, and interorganizational dynamics also shape these decisions (Casey et al. 2020; Miles et al. 2014). As Liévanos and Horne (2017) note, many, if not most, utility companies do not monitor or necessarily recognize the link between outage duration and socioeconomic disadvantages; instead, they often prioritize essential community assets or the number of customers impacted. Yet, beyond these technical and economic dimensions, energy systems are also essential to human health and well-being (Hernández, 2015; Tang and Kim, 2023), making them a key contextual determinant of societal functioning and well-being.

Energy insecurity denotes the inability of households to meet basic energy needs through electricity, gas, or other sources of power (Hernández, 2016; Tang and Kim, 2023). Social vulnerability, on the other hand, refers to a range of circumstantial realities that disadvantage certain communities owing to a history of underservice and systemic inequities, rendering them more susceptible to adverse outcomes following a disaster (Dugan et al. 2023; Fordham et al. 2013; Painter et al. 2024; Rao et al. 2023). This exploratory study examines the distribution of power outages by hazard type, considering contextual vulnerabilities in the highly disaster-prone U.S. Gulf Coast. In doing so, we aim to provide insight into the intersection of energy insecurity and social vulnerability and examine how power outages and natural hazards, both concurrently and separately, can cause disproportionate harm to vulnerable communities. After an overview of scholarship on this nexus, including an exploration of key terms and concepts, we examine county-level co-occurrence of power outages, disasters, and social disadvantages to infer profiles of regions experiencing longer outages following disasters. We end with a discussion of the key contributions of this study and avenues of moving this research forward, including practicable pathways extending from this work.

Background and review of the literature

When disasters such as hurricanes, tropical storms, thunderstorms, or tornadoes strike, they can damage electric lines, poles, or transmission towers, resulting in power outages. During winter storms, demand for heating, ice and snow accumulation on electric lines, and fuel limitations increase blackout risk (Peterson et al. 2024). Similarly, increased demand for air-conditioning during heat waves can make electric grids reach capacity. Electric power outages following disasters further affect water and wastewater systems, communications systems, emergency services, fuel availability, and transportation (Miller et al. 2015; Stock et al. 2023). For households and communities, this disrupts everyday activities, such as food and medication storage, clean water access, employment/school attendance, business operations, and health care (Casey et al. 2020; Dargin and Mostafavi, 2020; Hernández, 2016; Mitsova et al. 2018; Rao et al. 2024).

Nowhere in the United States are these effects more pronounced than in the U.S. Gulf Coast (Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas). Communities in this region have a history of underinvestment with both de facto and de jure racial segregation (such as redlining and zoning policies) that worked to institutionalize discrimination and further entrenched vulnerabilities (Meltzer et al. 2023; Oxfam America, 2025; Saha et al. 2024). The U.S. Southeast, including the Gulf Coast states, accounts for about 80% of U.S. counties where, over more than three decades, at least 20% of the population has lived in poverty (Benson et al. 2023). Regional population projections suggest significant growth in coming years, while it continues to house significant at-risk infrastructure (related to petrochemicals and other key industries) and a large socioeconomically disadvantaged population (Binita et al. 2021; Petkova et al. 2015). The region is also highly susceptible to extreme weather events, jeopardizing residents and affecting multiple aspects of their lives (Dargin and Mostafavi, 2020; Mitsova et al. 2018; Rodriguez et al. 2022). As a region known to be in “constant recovery mode” (Hansel et al. 2015, p. 657) from weather/climate and technological disasters, the Gulf Coast has witnessed more erratic and extreme weather in recent years (Strough et al. 2024). Due to its coastal geography, hurricanes, and rising sea levels are identified as the greatest threats, occurring independently or in combination (Biasutti et al. 2012; Petkova et al. 2015). Nonetheless, in recent years the region has experienced multiple other hazards, including heat waves, winter storms, and even freezes, resulting in severe financial and social impacts (NOAA NCEI, 2024).

Scholarships on the social dimensions of disasters and the impacts of extreme weather offer multiple informing constructs and frameworks. In this paper, we employ energy justice, social vulnerability, and cumulative social effects of hazards to contextualize potential impacts, including cascading impacts such as energy insecurity, and barriers to recovery among community members (Gill and Ritchie, 2020; Hahn et al. 2022; Hernández, 2015). Energy justice underscores the right of all individuals to reliable, affordable, and accessible energy systems that uphold public health (Fuller and McCauley, 2016; Sovacool et al. 2023).

Two pillars of energy justice, distributional and recognitional justice, focus on the spatial distribution of energy security and disruptions across communities (Buechler and Martínez-Molina, 2021; Tiwari, 2022) and the goal of recognizing the different impacts on energy access among different groups (Heffron, 2022). From a distributional justice perspective, the dispersal of environmental harms includes the spatial differentiation of restoration of critical infrastructure services such as energy systems. A recognitional perspective focuses on identifying communities that are experiencing longer restoration efforts after disaster impacts (Heffron, 2022; Tiwari, 2022; Tormos-Aponte et al. 2021). This body of work underscores the importance of considering persistent inequalities related to social location, health, and economic inequities, among other factors.

The concept of social vulnerability, a widely used index to inform emergency response and adaptation strategies, often signals the socioeconomic profile of those most at risk following environmental hazards. The cumulative effects of historical and contemporary sociopolitical challenges can compound the impacts of environmental stressors such as heat waves, cyclones, or pollution on vulnerable communities (Hansel et al. 2015; Meltzer et al. 2023). Examination of social vulnerability, therefore, can help identify groups whose energy rights may also be most at risk following environmental hazards and can inform response and adaptation strategies accordingly (Lehnert et al. 2020; Painter et al. 2024).

Investigations into the nexus of power outages, social and contextual vulnerabilities, and disasters reveal that the co-occurrence of disaster-related power outages and social vulnerability can increase the likelihood of adverse health outcomes, especially for historically underserved and marginalized communities such as people with disabilities, older adults, and the poor (Do et al. 2023; Mitsova et al. 2018; Rodriguez et al. 2022). This is evident in the U.S. Gulf Coast. In Texas, for example, a survey (n = 753) across eight metropolitan areas suggested that African Americans, families with children, and renters experienced longer outages following Winter Storm Uri (Grineski et al. 2023). Research on disaster vulnerability also indicates that Black and African American communities encounter heightened risks at all stages of disasters—before, during, and after (Cano Pecharroman and Hahn, 2024; Finch et al. 2010; Fordham et al. 2013; Rivera and Miller, 2007). Similarly, counties with more Hispanic residents experienced more acute power outages, Black respondents were more likely to report outages longer than a day, and respondents with lower educational attainment were less likely to be prepared for outages (Flores et al. 2023).

These risks arise from a history of marginalization, socioeconomic inequalities, and systemic obstacles to effective disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. For example, Bullard (2008) utilized an environmental justice approach to assess the impact of disparities on government responses to weather-related disasters, starting in 1927 with the Great Mississippi Flood and extending to Hurricane Katrina in 2005. This approach considers the interplay of race, class, and social vulnerability. Bullard questioned the government’s preparedness, the fairness of responses, and the ongoing marginalization of African American communities during disasters. The study showed how historical inequalities worsen the effects of disasters on marginalized groups, leading to inequitable recovery efforts and outcomes. Other researchers, like Fussell et al. (2010), found that Black residents in New Orleans were more susceptible to housing damage from Hurricane Katrina. More recently, Mitsova et al.’s (2018) work on the impact of infrastructure disruptions on household recovery following Florida’s Hurricane Irma (2017) showed that Black/African Americans, individuals with limited English proficiency, and those in need of timely, uninterrupted medical care faced a higher risk of experiencing a prolonged partial recovery.

Recognizing these trends, several scholars have attempted to examine the link between disasters and power outages in the United States. Prominently, Do et al. (2023) examined the occurrence and distribution of outages across the country from 2018 to 2020. They found that counties in Louisiana and Mississippi experienced high social vulnerability and longer outages (8 h or more). Further, compared to other states, these states had higher proportions of residents with racial/ethnic minority status and of those living in poverty and mobile homes, exacerbating challenges for individuals in disaster risk zones. In Florida, after Hurricane Irma, Mitsova et al. (2018) found a relationship between outage duration and three social vulnerability indicators: being part of a minoritized group (Hispanic or Latino), unemployed, or a member of a population with sensory, physical, or mental disability (Burger et al. 2017; Mitsova et al. 2018; U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2017; Uduba and Gillum, 2024). Other regional examinations of populations exposed to extreme weather events in the Gulf Coast have focused mainly on tropical cyclones, and while these are major hazards, they constitute just one among several hazard exposures. Most studies to date have focused on individual hazards such as tropical storms or heat waves, or single extreme events such as Hurricane María or Winter Storm Uri.

In summary, some of this scholarship has documented the impacts of specific hazards such as tropical storms on energy systems and population health outcomes (Burrows et al. 2023; Do et al. 2023; Parks et al. 2022; Voisin et al. 2016), while other studies have detailed the socioeconomic and vulnerability profiles of affected populations (Do et al. 2023; Dugan et al. 2023; Mitsova et al. 2018). Yet there has been limited focus on the range of hazards affecting these communities, which can lead to differential yet compounding and cumulative effects through repeated exposure (Leppold et al. 2022; Sotolongo et al. 2021). Moreover, when considering energy as not just a commodity but also a key resource for quality of life in our society, there is a need to understand power outage patterns across different hazard exposures and to evaluate the profiles of those who experience longer power outages and/or delayed restoration.

With this study, we advance the current understanding of energy restoration in the wake of multiple disasters in the U.S. Gulf Coast. Moving away from single events or site-specific assessments, as most previous studies have done, we consider the temporal and compounded nature of multiple hazards, examining them through a combination of several data sources. Further, we utilize the theoretical underpinnings of energy justice and social vulnerability to contextualize community experiences in this region. Focusing on the U.S. Gulf Coast enables us to look for patterns linking events or stages, driving detailed insights into challenges and therefore informing strategies for mitigating disaster impacts, policymaking, energy transitions, and resilience. The results may offer restoration policy and research insights emphasizing justice-based frameworks.

Methods

We combined information from multiple data sources to characterize the Gulf Coast’s social and infrastructure vulnerabilities, specifically vulnerability to power outages. Table 1 specifies these data sources and includes information on the level of aggregation and key variables included in the study. For disaster-related information, we used Arizona State University’s Spatial Hazard Events and Losses Database for the United States, Version 21 (SHELDUS, 2023). These data were available at monthly and county levels for 2017 to 2021 and included information about hazards such as flooding or erosion, droughts, floods, hailstorms, heat waves, hurricanes/tropical storms (included as a single category), landslides, lightning, thunderstorms, tornadoes, wildfires, windstorms, and winter storms. Power outage information (2017–2022) was sourced from poweroutage.us, compiled by Bluefire Studios, a private LLC that collects outage data nationwide. Poweroutage.us works with electricity distribution companies to combine data tracking the number of customers without power during outages, regardless of cause and provides information on outage events (beginning and end time stamps) and duration in hours. We included information on event duration based on estimates provided by poweroutage.us, focusing on average outage durations within a month and county. Many counties did not have any outages in a particular month, indicated by zeros across months and counties; these were excluded from our analysis. These data were aggregated by month and merged with SHELDUS data. Thus, the variables of interest were the monthly average outage duration and key hazards within a county.

We used information on social vulnerability indicators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) (2016, 2018, 2020). SVI, a composite measure of sixteen U.S. census variables, is routinely used to help researchers and decision-makers identify communities that need additional support throughout the disaster life cycle, including during nondisaster times. SVI is recalculated every two years using new information collected by the U.S. census. Each county had SVI information for 2016, 2018, and 2020. Therefore, our conceptualization of vulnerability was limited to a fixed feature of a county occurring in 2-year blocks.

The SVI serves as a valuable resource for evaluating the impact of social, economic, and demographic factors on communities’ vulnerability to hazards (Painter et al. 2024; Peek et al. 2020), though several limitations have been identified in the literature, ranging from indicators not accounting for the diversity of context (geographic regions or cultural nuances); to its mainly quantitative approach, which somewhat limits opportunities to understand context-specific aspects of vulnerability; to theoretical misalignments and internal inconsistencies (Cutter, 2024; Lehnert et al. 2020; Spielman et al. 2020; Tormos-Aponte et al. 2021; Wood et al. 2021). To overcome some of these limitations, we integrated various datasets and considered how they enhance our understanding of social vulnerability in the context of energy restoration, cumulative hazards, and energy justice in U.S. Gulf Coast states.

Despite the noted limitations, the SVI is one of the more widely used indexes for assessing social vulnerability in the continental United States. Among its themes, Theme 3—Racial and Ethnic Minority Status—supports the identification of the disproportionate impact of power outages on marginalized communities by highlighting racial, ethnic, and other disparities. This builds on previous research, such as that of Mitsova et al. (2018) in Florida following Hurricane Irma, who showed that the proportion of Hispanic/Latino and Black or African American individuals in counties was significantly correlated with the average length of power outages. We merged these county-level data with outage data sourced from poweroutage.us.

Although data for Gulf Coast states for the period 2017 to 2022 were included, we focused on the intersection of months when outages and disasters occurred within a county and did not include months where there was no outage or no disaster. All data used in this study were aggregated at the county level and were either publicly available or privately aggregated and de-identified. Owing to the nature of the data, this study did not meet the definition of human studies research and was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at Ohio State University.

Data management

To prepare these datasets for analysis, we checked all county and parish names for consistency (e.g., De Soto vs. DeSoto) and adjusted as necessary. The month–year–county level was determined to be the finest resolution to combine these datasets. For datasets with a time resolution finer than month–year–county (SHELDUS), we summarized these to the month using the mean, standard deviation, and sum. We then created a grid of all months, years, and county Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) codes in the study areas and merged this with other datasets using county, year, and month variables. This approach enabled us to preserve time gaps between outages and hazards and to determine cases where hazard data existed without outage data. We then filtered this data table to include only those cases where both a hazard and an outage occurred, to focus explicitly on the relationship between hazards and outage duration. Finally, we merged vulnerability data from the SVI to provide a single coarse measure of vulnerability for each data year.

The resulting dataset contained rows corresponding to every hazard and outage that occurred every month from 2017 to 2021 in 482 counties, with additional columns on the severity of the hazard, details about outages, and repeating columns of SVI variables for that year. Combining the data enabled us to describe the variation in outages from 2017 through 2022 (from the poweroutage.us dataset). However, we could link outages and hazard events only from 2017 through 2021 due to data availability in the SHELDUS version used in this study.

Analytic plan

Using the R package brms (Bürkner, 2017), we developed hierarchical Bayesian models to estimate average outage duration that could account for variation in associated hazards, counties, and years. This hierarchical model enabled us to partially pool information across counties (Gelman et al. 2012), providing a conservative view of uncertainty around our estimates of average energy interruptions. Measures of outage duration were positive, continuous values that formed a right-skewed distribution. We used a gamma likelihood with a log link, an approach commonly used to model heterogeneous duration measures (Butler and Worrall, 1991). Our model estimated a mean and variance for each county and hazard, that is, varying intercepts.

We also used the varying intercepts approach to estimate the average outage duration associated with each hazard category. To account for year-by-year differences in outage durations, we included the year as a dummy-coded variable. We set modestly informative priors on model parameters that allowed for a broad range of model outcomes while eliminating implausible values and improving model convergence. Markov chain Monte Carlo diagnostics showed that all chains adequately mixed and exhibited Rhat values of ~1, suggesting that the model converged and properly sampled the parameter space. Additional details about the model structure and priors can be found in the supplementary information.

We created bivariate choropleth maps to visually examine the relationship between observed/estimated outages and social vulnerability. These maps visualize two variables by binning each variable using terciles (low, medium, and high) and creating a three-by-three color key to show their spatial distribution. Each county was then colored according to where the two variables fell, allowing us to discern areas of high concern. For example, a county in which SVI and estimated outages fall into the high category would be distinguished from a county in which SVI is low but outages are estimated to be high.

All data management and analyses were conducted in R (r-project.org) using the tidyverse suite of packages (Wickham et al. 2019). Maps were created with the R packages Map Tools (Bivand and Lewin-Koh, 2023), Geospatial (Dunnington, 2023), and the Scale package for bivariate maps (Prener et al. 2022). We developed multilevel Bayesian models using the R packages brms (Bürkner, 2017) and Tristan, which together serve as a convenient interface for Stan, a high-performance statistical computing software package (mc-stan.org). Model summaries were generated using modelr (Wickham, 2023) and tidybayes (Kay, 2023).

Results

We had complete information on outages and disasters for 482 out of 534 counties in the region (SVI was available for all counties). Descriptive analyses indicated considerable variation in hazard frequency and outage duration across counties. Outages from wildfire ranged from 0.16 to 16.89 h, and outages due to drought lasted from 0.14 to 18.50 h (Table 2). An outage from landslides occurred just once and lasted 5.51 h. Outages from wind were widespread, occurring 11,248 times and lasting from 0.11 to 1411.21 h. Hurricanes and lightning were associated with the lengthiest observed outages, at 4512.91 and 3535.87 h, respectively. However, outages during heat waves and hurricanes had a higher median length of 2.10 and 2.00 h, respectively. Figure 1 shows the cumulative exposure to power disruption in each state, with steep increases in outages in Texas and Louisiana occurring in late 2020 and early 2021.

Predicted power outage duration by hazard category

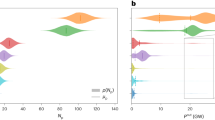

Next, we used a generalized linear model function to examine outage durations across counties, hazard categories, and data years. Outage duration exhibited extreme variation, with many relatively short outages combined with a lesser number of rare events leading to extended periods without power. Predicted outage durations for each hazard category are summarized at the state level in Table 3. Hurricanes/tropical storms and heat waves were associated with the longest power outages, although there was considerable variation by state. Louisiana exhibited longer outages than the other states. Average predicted outage durations for hurricanes/tropical storms were 61.04 hours (95% CI = [6.02, 351.02]). Heat waves were associated with relatively long average outages across all states (Alabama = 19.53 h; Florida = 24.78 h; Louisiana = 41.6 h; Mississippi = 22.75 h; and Texas = 17 h). Droughts and coastal hazards were predicted to have short outage durations. Figure 2 illustrates predicted average outage durations by hazard category, accounting for variation by county and across years. Especially rare hazards such as landslides yielded model estimates with a higher level of uncertainty due to fewer observations. Aside from heat waves and hurricanes/tropical storms, outages for other hazards were expected to last between 2.5 and 20 h on average.

Figure 3 illustrates the natural log of hazard frequencies at the county level across years to compare hazard exposures. The southwestern regions of Mississippi and Louisiana experienced the highest frequency of disasters, with a peak in Mississippi in 2019. Central and eastern Texas also showed a rising hazard frequency trend over time. Outage durations clustered in coastal and riverside counties and regions, particularly along the Mississippi Delta and Florida coast. Hazards were most frequent in counties surrounding large cities. In Texas, counties surrounding Dallas and Fort Worth in the northern portion of the Coastal Plain experienced hazards most frequently, while counties in western Texas and the southern Coastal Plain experienced some of the longest outage durations across all years. Hazards were most frequent in southwest Louisiana and southwest Mississippi, although outages tended to be longest in the greater New Orleans region in the southeast.

For each county, we calculated the total number of hazards per year and then added 1 to derive the natural log of this value. The resulting values were mapped on the same scale for all states to ease comparison. For reference, the values 2, 4, and 6 in the legend are approximately 6, 54, and 402 events, respectively.

Outages throughout Louisiana in 2020 and 2021 were especially lengthy due to Hurricanes Laura, Delta, Ida, and other severe storms. Extended outages (8 h or longer) were common along the Mississippi River in all data years, particularly in the Mississippi Delta alluvial floodplain. In the 30 counties within this floodplain, more than half (51.36%) of all outages were estimated to be longer than 8 h. The 2020–2021 disasters severely impacted Alabama, leading to a large cluster of extended outages from the southwest coast into central Alabama. Hazard frequency was high in Baldwin County in 2017 and on the northern border of Alabama across data years. Outages in Florida were especially long in 2017 and were generally the lengthiest in Florida’s southeast and southwest regions.

We used fixed effects estimation to approximate changes in average outage duration by year (Table 4). Posterior predictions indicated that 2017 had the longest outages on average at 10.56 h (95% CI = [6.14, 15.7]). The shortest outages were in 2019, with an average of 2.6 h (95% CI = [1.51, 3.82]).

Top and bottom ten counties

In addition to annual variation, we estimated a varying intercept parameter for each county, allowing us to examine county variation in outages irrespective of hazards. Of 482 counties, we focused on the 10 most and least vulnerable counties to better understand how counties with extreme outage durations compare to those with particularly short outages. Seven of the 10 counties predicted to have the greatest outage offsets were in Louisiana. Only one of these seven counties (St. Charles Parish) had an overall SVI of less than 0.5, suggesting a concentration of longer and more extreme outages in areas with the highest vulnerability. Catahoula Parish had the longest average outage (M = 25.47 h, 95% CI = [15.82, 25.29]), followed by LaSalle Parish (M = 15.10 h, 95% CI = [7.08, 25.96]), and Lafourche Parish (M = 11.93 h, 95% CI = [4.54, 21.14]). All three lie on the western edge of the Mississippi Delta, with the nearest major city being Natchez, Louisiana.

We also generated posterior predictive distribution for every county at every hazard category and then averaged these predictions to arrive at an average estimate of outage duration. The top three counties were Catahoula, LaSalle, and Lafourche Parishes in Louisiana, with predicted outage durations of 148.64 h (SD = 122.45) in Catahoula, 111.04 h (SD = 91.45) in LaSalle, and 87.80 h (SD = 72.20) in Lafourche. These counties represent different cases leading to extended outage durations. Catahoula Parish experienced 71 hazards associated with an outage. In contrast, Lafourche Parish experienced just five hazards, including a hurricane, that led to an extended outage. Outages associated with hurricanes/tropical storms were predicted to last nearly three weeks (M = 482.14 h, SD = 246.93) in Catahoula Parish. Heat waves (M = 331.53 h, SD = 192.15) and winter weather (M = 157.88 h, SD = 80.9) were predicted to create long outages. Other counties in Louisiana (St. Charles Parish, Jefferson Parish), near New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta, were predicted to have outages longer than two days. Outside Louisiana, Jefferson County, Texas (M = 63.80 h, SD = 52.54), as well as Gulf County (M = 48.78 h, SD = 40.19) and Gilchrist County (M = 40.06 h, SD = 33.01) in Florida were among the top 10 counties predicted to have long average outage durations. Jefferson and Gulf Counties are coastal, while Gilchrist is in the inland part of North Florida, just outside Gainesville. Overall vulnerability in these communities varied from 0.316 in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana, which can be considered low social vulnerability, to 0.889 in Jefferson County, Texas, indicating high social vulnerability. Specifically, for SVI Theme 3, half of the counties were above 0.7 (for instance, 0.938 in Jefferson County, Texas), indicating that most of the nation’s counties were less vulnerable than these counties, while the other half were between 0.5 and 0.6, indicating midlevel to high social vulnerability. Catahoula Parish, Louisiana, the county with the longest outage duration, had an SVI 3 value of 0.509, indicating a midlevel social vulnerability.

Examination of posterior predicted outage duration averaged over all hazards and years revealed that the 10 counties with the lowest outage durations were all in Texas. Outage durations in these counties ranged from 0.77 to 1.73 h. Although these counties did experience some extensive outages due to hazards, predictions for each hazard category were, on average, very short. Glasscock County, Texas, for example, was predicted to have just a 2.5-h-long average outage during a hurricane or tropical storm. The overall vulnerability of these bottom 10 counties varied considerably, with some counties having high vulnerability (e.g., Harrison County, SVI = 0.813) and others relatively low (e.g., Glasscock County, SVI = 0.26). Looking at SVI Theme 3 (Racial and Ethnic Vulnerability), these counties varied from 0.44 (low social vulnerability) in Llano County, Texas, to 0.98 in Uvalde County, Texas, with six of the 10 greater than 0.7 (high social vulnerability).

Estimated outage duration by county social vulnerability

Finally, we examined how average and predicted outage duration was associated with county social vulnerability characteristics using bivariate choropleth maps. Figure 4 represents overall SVI and SVI Theme 3 (Racial and Ethnic Minority Status) juxtaposed with the county average and predicted outages for comparison. (Information on other SVI themes is given in Supplementary Fig. S1 through S11.) Given the differential outcomes due to the racial disparities noted in previous studies and the history of marginalization in states along the U.S. Gulf Coast, we were better able to examine this context of social vulnerability, power outages, and disasters. Regions where social vulnerability and outage duration were greatest tended to be along the Mississippi River in Louisiana and Mississippi, in central Florida, and along the border of Texas and Mexico. Examining social vulnerabilities associated with racial, ethnic, and minority status revealed that high vulnerability and long outage durations coincide along the southern coast of Florida and the Gulf Coast of Texas. Our analysis identified counties where social vulnerability and long outage durations overlap (both in observed data and in predicted estimates), allowing us to pinpoint communities with an urgent need for policy intervention and infrastructure outreach. These communities are primarily located along the Gulf Coast, in the Mississippi Delta region, and along the Texas–Mexico border.

The colored matrix provides a key for interpreting where a county falls on vulnerability and outage duration. Observed outage duration refers to the measured duration found in our dataset. The predicted average duration is the value predicted without a multilevel model after partial pooling of measures across counties, hazards, and years. Counties in white are those where no data was available for either hazard events or outages.

Discussion

Vulnerable communities in the U.S. Gulf Coast have been profoundly impacted by disaster-related power outages. The combination of a unique geography and historic underinvestment in communities and infrastructure calls attention to the need to consider energy service provision beyond dominant technical and market-based approaches (Heffron, 2022) and to look at the cumulative experiences that increase risks of adverse outcomes. In this study, we examined the distribution of power outages by hazard type across the disaster-prone Gulf Coast states. We also examined the co-occurrence of these outages by hazard types alongside county-level social vulnerabilities to derive insights into the intersection of energy insecurity and social vulnerability and appraise how power outages and natural hazards cause disproportionate harm to vulnerable communities.

The most protracted outages were associated with hurricanes/tropical storms and heat waves, as reported in other studies (Do et al. 2023). The region is marked by severe storms and hurricanes and faces increasingly harsh heat days, a trend expected to worsen with unchecked climate change. As previous analyses have determined (Do et al. 2023; Energy Information Administration, 2021), Louisiana and Mississippi had the longest outages across nearly all disaster categories. Florida, too, emerged as an outlier, ostensibly owing to a large coastline and varying frequency of hazards and outage durations throughout the state in different years. We noted higher social vulnerability in counties in Louisiana, Mississippi, and southwest Alabama.

Examination of SVI Theme 3 (Racial and Ethnic Vulnerability) revealed similar patterns along the Mississippi River, in southern and western Texas, and along the southern tip of Florida. While outage durations vary across socially vulnerable counties, individual and community factors can amplify these effects; a more socially vulnerable region might be more susceptible to harm, owing to factors that enervate community capacity to adapt and recover from disasters. A power outage in this scenario (or multiple repeated outages) can render an already vulnerable community worse off, making it difficult to recover.

We examined both observed and predicted power outage durations to potentially view patterns of similarities and departures. The varying intercepts model with partially pooled data accounting for spatial autocorrelations across all counties helps estimate average outage durations that identify potentially at-risk counties that did not have observed outages. Juxtaposing these two together revealed several counties that did not surface in the observed data could yet be at risk given their social or contextual vulnerabilities and regional susceptibility to various extreme weather events. This offers multiple considerations for preparedness and planning efforts at regional and county levels. Future research should also explore these concurrent vulnerabilities further using inferential models linking outage duration to hazard types and county attributes.

Counties predicted to have the longest outage durations cannot be taken as monolithic exemplars of how outages and hazards are associated in the region; they point us toward extreme cases where communities may face extended exposure to power disruptions. The intersection of high concentration of racial, ethnic, and minority status with long outages was present along the southern coast of Florida and the Gulf Coast of Texas. The 10 counties with the lowest predicted outages were all in Texas, perhaps because counties in Texas make up more than half of all counties in this dataset. Several Texas counties in the south-central region, near Austin and San Antonio (Kimble and Lee Counties) had average outage duration offsets of less than an hour.

The low estimates and lack of variation among these counties suggest that this region of Texas has fewer exogenous disruptions to power. Considering the multiple hazards to which the region is exposed, findings can support the development of targeted interventions, emergency management plans, and coping strategies for communities that are expected to experience longer power outages. Many prevalent energy restoration efforts do not take into account the long-standing inequalities in a region owing to historic and contemporary inequities, with scholars pointing to the shortcomings of population- or density-based restoration efforts (Tormos-Aponte et al. 2021).

Incorporating data from outage maps helps to identify whether vulnerable communities face prolonged power disruptions that could exacerbate their vulnerability. Clarifying the relationship between vulnerability and power outages within these communities, particularly in the U.S. Gulf Coast, is essential, given the historical policy context that created lasting disadvantages for many communities. Our work adds to recent analyses examining the intersection of disasters, power disruptions, and social vulnerability (Coleman et al. 2023; Do et al. 2023; Dugan et al. 2023; Flores et al. 2024). Rather than focusing on large events alone, we included the full distribution of outages (short to prolonged), offering an insight into how short, frequent outages from less severe disasters are a persistent stressor that might interact with social vulnerability. We constructed a generalized linear model to estimate outages by disaster category, explicitly focusing on outages with an associated hazard, offering a granular perspective on the relationship between disasters and power outages by incorporating social vulnerability factors and focusing on hazard-related incidents in the climate-vulnerable U.S. Gulf Coast. In analyzing descriptive elements of the maps, gradually assessing themes across social vulnerability, and understanding predicted outage durations from disasters in Gulf Coast counties, our study further identifies areas requiring significant infrastructure investment while also recognizing underlying drivers of inequality.

The added value of this work lies in advancing targeted efforts for energy security, drawing from distributive and recognition justice principles. Exploring these datasets (the Social Vulnerability Index, power outage data, and disaster declarations) together, we lay a foundation for identifying convergent solutions (Peek et al. 2020) and for future work with “problem-focused” and “solutions-oriented” research. For utilities, policymakers, emergency management and preparedness decision-makers, and others, the results of this study can provide a first step to consider support for policy changes in infrastructure investment, grid modernization projects, microgrid development, or equity-driven resilience planning. Building on previous scholarship that acknowledges these risks arising from a history of marginalization toward minoritized communities, especially those facing socioeconomic inequalities and systemic obstacles to effective disaster preparedness, response, and recovery, this study also serves as a baseline for community discussions on how to improve emergency management strategies. By acknowledging which counties might be at higher risk of power outages and, consequently, energy insecurity challenges, including health impacts, food insecurity, or water insecurity, this study can enhance local community resilience. However, we also acknowledge that future work and targeted efforts within the counties identified will be needed. This will be of value for the well-being of residents in counties across the region.

Scholarly examinations of the SVI have recommended the need for its use to understand and address everyday vulnerabilities and challenges among populations (Painter et al. 2024). In response to studies that attribute the entrenched inequities in energy restoration to bureaucratic decision-making (Liévanos and Horne, 2017), where numbers and assets are prioritized over actual need and taking cumulative disadvantage into account, our study offers potential pathways forward. For instance, if utility providers can work with disaster planners and emergency managers to understand the linkages between socioeconomic vulnerability and power outages, they could take proactive steps to implement programs that account for spatial and social inequities and improve service to vulnerable populations (Liévanos and Horne, 2017; Mitsova et al. 2018). Future mixed methods studies can also look to convene stakeholders, particularly in highly vulnerable regions, to examine specific challenges and opportunities to support identified communities’ move toward a more resilient grid and distributive energy justice including in nondisaster times to improve system capabilities for when the next disaster occurs.

Data used in this study also offer future considerations. For instance, we did not examine information on the number of customers tracked, which poweroutage.us incorporates; future studies can factor this into making assessments about the breadth of impacts and simulate broader implications for socially vulnerable groups and regions. Finally, while we focused mostly on Theme 3, for reasons explicated in previous sections, across all themes, we noted high social vulnerability coinciding with longer power outages, particularly along the Mississippi River, in southern and northern Texas, in southern and central Florida, and throughout Louisiana and Mississippi. Future studies can examine more place-based and regional variations and community experiences to refine this knowledge further.

Limitations

Since some data were aggregated at the monthly level, it may not be immediately clear which hazard caused an outage; some months could have multiple hazards co-occur, a regular phenomenon in the region. However, our multilevel model accommodates this by estimating the variance within and between hazard categories and uses this partial pooling approach to provide outage estimates based on the full range of uncertainty observed for different hazards and counties. In this sense, our estimates are statistically conservative, as the multilevel modeling approach tends to balance problems that arise from over- or under-fitting (McElreath, 2018). Although our model was not constructed to determine the precise probability that an outage will occur within a county, it is generally capable of estimating the expected average duration of an outage associated with different hazards if an outage has occurred. In this sense, the model can be generalized to other regions facing hazards or to more finely resolved data.

Second, the social vulnerability indexes used in our study are at the county level and did not allow for a detailed and more localized place-based assessment. The use of county-level data also precluded an examination of structural conditions within counties that may lead to more outages, such as energy vulnerabilities arising from the network structure of the power grid itself. Future studies can go beyond the descriptive elements of this study and employ a more temporal and causal assessment of outages in the context of hazards and social vulnerability. Finally, in 2020 the CDC modified Theme 3 from “Minority Status and Language” in the years before to “Racial and Ethnic Minority Status” owing to methodological developments (CDC, 2022). These changes likely have a bearing on model takeaways while offering an overall measure of structural disadvantage in the county.

Conclusion

This paper provides additional insights into the intersection of energy insecurity and social vulnerability, with a specific focus on how power outages and extreme weather events co-occur to wreak disproportionate harm on vulnerable populations. We focused on states in the U.S. Gulf Coast, given the confluence of geographic and social vulnerabilities in the region. Highlighting the risk of energy insecurity among populations beyond a single hazard, the paper takes a generalized approach to understanding how extreme weather events and energy insecurity interact over time. Importantly, the analysis helps to identify “extreme” cases using a recognitional justice perspective to provide insights into community disruptions from exposure to disasters and energy injustices. This information can provide a baseline for policymakers and community-based organizations to more equitably focus on service delivery and energy restoration efforts.

Data availability

Data used in this study were a combination of publicly available and restricted data. Source code can be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Benson C, Bishaw A, Glassman B (2023) 341 U.S. counties experiencing persistent poverty. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/05/persistent-poverty-areas-with-long-term-high-poverty.html

Biasutti M, Sobel AH, Camargo SJ, Creyts TT (2012) Projected changes in the physical climate of the Gulf Coast and Caribbean. Clim Change 112(3):819–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0254-y

Bivand R, Lewin-Koh N (2023) maptools: tools for handling spatial objects (Version 1.1-8) [computer software]. CRAN. http://maptools.r-forge.r-project.org

Buechler S, Martínez-Molina KG (2021) Energy justice, renewable energy, and the rural-urban divide: insights from the Southwest U.S. Energy Clim Change 2:100048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egycc.2021.100048

Bullard RD (2008) Differential vulnerabilities: environmental and economic inequality and government response to unnatural disasters. Soc Res 75(3):753–784

Burger J, Gochfeld M, Pittfield T, Jeitner C (2017) Responses of a vulnerable Hispanic population in New Jersey to Hurricane Sandy: access to care, medical needs, concerns and ecological ratings. J Toxicol Environ Health Part A 80(6):315–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287394.2017.1297275

Bürkner P-C (2017) brms: an R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J Stat Softw 80(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v080.i01

Burrows K, Anderson GB, Yan M, Wilson A, Sabath MB, Son JY, Kim H, Dominici F, Bell ML (2023) Health disparities among older adults following tropical cyclone exposure in Florida. Nat Commun 14(1):2221. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37675-7

Büscher C (2022) The problem of observing sociotechnical entities in social science and humanities energy transition research. Front Sociol 6:699362. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.699362

Butler RJ, Worrall JD (1991) Gamma duration models with heterogeneity. Rev Econ Stat 73(1):161. https://doi.org/10.2307/2109700

Cano Pecharroman L, Hahn C (2024) Exposing disparities in flood adaptation for equitable future interventions in the USA. Nat Commun 15(1):8333. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52111-0

Casey JA, Fukurai M, Hernandez D, Balsari S, Kiang MV (2020) Power outages and community health: a narrative review. Curr Environ Health Rep 7(4):371–383

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC (2022) CDC/ATSDR SVI 2020 documentation. https://svi.cdc.gov/map25/data/docs/SVI2020Documentation_08.05.22.pdf

Cherp A, Vinichenko V, Jewell J, Brutschin E, Sovacool B (2018) Integrating techno-economic, socio-technical and political perspectives on national energy transitions: a meta-theoretical framework. Energy Res Soc Sci 37:175–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.09.015

Coleman N, Esmalian A, Lee C-C, Gonzales E, Koirala P, Mostafavi A (2023) Energy inequality in climate hazards: empirical evidence of social and spatial disparities in managed and hazard-induced power outages. Sustain Cities Soc 92:104491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.104491

Cutter SL (2024) The origin and diffusion of the social vulnerability index (SoVI). Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 109:104576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104576

Dargin JS, Mostafavi A (2020) Human-centric infrastructure resilience: uncovering well-being risk disparity due to infrastructure disruptions in disasters. PLoS ONE 15(6):e0234381. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234381

Do V, McBrien H, Flores NM, Northrop AJ, Schlegelmilch J, Kiang MV, Casey JA (2023) Spatiotemporal distribution of power outages with climate events and social vulnerability in the USA. Nat Commun 14(1):2470. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38084-6

Dugan J, Byles D, Mohagheghi S (2023) Social vulnerability to long-duration power outages. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 85:103501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103501

Dunnington D (2023) Spatial data framework for ggplot2 (Version 1.1.9) [computer software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggspatial

Energy Information Administration (2021) Hurricane Ida caused at least 1.2 million electricity customers to lose power. Today in Energy https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=49556

Finch C, Emrich CT, Cutter SL (2010) Disaster disparities and differential recovery in New Orleans. Popul Environ 31(4):179–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-009-0099-8

Flores NM, McBrien H, Do V, Kiang MV, Schlegelmilch J, Casey JA (2023) The 2021 Texas power crisis: distribution, duration, and disparities. J Exp Sci Environ Epidemiol 33(1):21–31. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-022-00462-5

Flores NM, Northrop AJ, Do V, Gordon M, Jiang Y, Rudolph KE, Hernández D, Casey JA (2024) Powerless in the storm: severe weather-driven power outages in New York State, 2017–2020. PLoS Clim 3(5):e0000364. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000364

Fordham M, Lovekamp WE, Thomas DSK, Phillips BD (2013) Understanding social vulnerability. In: Thomas DSK, Philips BD, Lovekamp WE, Fothergill A (eds) Social vulnerability to disasters, 2nd edn. CRC Press, pp. 1–29

Fuller S, McCauley D (2016) Framing energy justice: perspectives from activism and advocacy. Energy Res Soc Sci 11:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.08.004

Fussell E, Sastry N, VanLandingham M (2010) Race, socioeconomic status, and return migration to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Popul Environ 31(1–3):20–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-009-0092-2

Gelman A, Hill J, Yajima M (2012) Why we (usually) don’t have to worry about multiple comparisons. J Res Educ Eff 5(2):189–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2011.618213

Gill D, Ritchie L (2020) Considering cumulative social effects of technological hazards and disasters. Am Behav Sci 64(8):1145–1161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764220938112

Grineski SE, Collins TW, Chakraborty J, Goodwin E, Aun J, Ramos KD (2023) Social disparities in the duration of power and piped water outages in Texas after Winter Storm Uri. Am J Public Health 113(1):30–34. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2022.307110

Hahn MB, Van Wyck R, Lessard L, Fried R (2022) Compounding effects of social vulnerability and recurring natural disasters on mental and physical health. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 16(3):1013–1021. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.476

Hansel TC, Osofsky HJ, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Speier A, Rehner T, Osofsky JD, Rohrer G (2015) Gulf Coast Resilience Coalition: an evolved collaborative built on shared disaster experiences, response, and future preparedness. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 9(6):657–665. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2015.118

Heffron RJ (2022) Applying energy justice into the energy transition. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 156:111936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111936

Hernández D (2015) Sacrifice along the energy continuum: a call for energy justice. Environ Justice 8(4):151–156. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2015.0015

Hernández D (2016) Understanding “energy insecurity” and why it matters to health. Soc Sci Med 167:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.029

Kay M (2023) tidybayes: tidy data and geoms for Bayesian models (version v3.0.6) [vomputer software]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8242124

Binita KC, Shepherd JM, King AW, Johnson Gaither C(2021) Multi-hazard climate risk projections for the United States Nat Hazards 105(2):1963–1976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-04385-y

Kenward A, Raja U (2014) Blackout: extreme weather, climate change, and power outages. Climate Central. https://assets.climatecentral.org/pdfs/PowerOutages.pdf

Lehnert EA, Wilt G, Flanagan B, Hallisey E (2020) Spatial exploration of the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index and heat-related health outcomes in Georgia. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 46(June):101517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101517

Leppold C, Gibbs L, Block K, Reifels L, Quinn P (2022) Public health implications of multiple disaster exposures. Lancet Public Health 7(3):e274–e286. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00255-3

Liévanos RS, Horne C (2017) Unequal resilience: The duration of electricity outages. Energy Policy 108:201–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.05.058

McElreath R (2018) Statistical rethinking: a Bayesian course with examples in R and Stan. Chapman and Hall/CRC

Meltzer GY, Merdjanoff AA, Xu S, Gershon R, Emrich CT, Abramson DM (2023) Examining the effects of cumulative environmental stressors on Gulf Coast child and adolescent health. Popul Environ 45(3):21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-023-00436-1

Miles SB, Gallagher H, Huxford CJ (2014) Restoration and impacts from the September 8, 2011, San Diego power outage. J Infrastruct Syst 20(2):05014002. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)IS.1943-555X.0000176

Miller CA, Richter J, O’Leary J (2015) Socio-energy systems design: a policy framework for energy transitions. Energy Res Soc Sci 6:29–40

Mitsova D, Esnard A-M, Sapat A, Lai BS (2018) Socioeconomic vulnerability and electric power restoration timelines in Florida: the case of Hurricane Irma. Nat Hazards 94(2):689–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3413-x

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (2024) Billion-dollar weather and climate disasters. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions

Oxfam America (2025) Mapping social vulnerability in southeastern states and the Gulf Coast. https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/countries/united-states/poverty-in-the-us/mapping-social-vulnerability-in-southeastern-states-and-the-gulf-coast

Painter MA, Shah SH, Damestoit GC, Khalid F, Prudencio W, Chisty MA, Tormos-Aponte F, Wilhelmi O (2024) A systematic scoping review of the social vulnerability index as applied to natural hazards. Nat Hazards 120(8):7265–7356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-023-06378-z

Parks RM, Benavides J, Anderson GB, Nethery RC, Navas-Acien A, Dominici F, Ezzati M, Kioumourtzoglou M-A (2022) Association of tropical cyclones with county-level mortality in the U.S. JAMA 327(10):946. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.1682

Peek L, Tobin J, Adams RM, Wu H, Mathews MC (2020) A framework for convergence research in the hazards and disaster field: the natural hazards engineering research infrastructure CONVERGE facility. Front Built Environ 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2020.00110

Peterson SKE, Clark SS, Shelly MA, Horn SEM (2024) Assessing the household burdens of infrastructure disruptions in Texas during Winter Storm Uri. Nat Hazards 120(8):7065–7104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-024-06480-w

Petkova EP, Ebi KL, Culp D, Redlener I (2015) Climate change and health on the U.S. Gulf Coast: public health adaptation is needed to address future risks. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12(8):9342–9356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120809342

Prener C, Grossenbacher T, Zehr A (2022) biscale: tools and palettes for bivariate thematic mapping (version 1.0.0) [computer software]. CRAN. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=biscale

Rao S, Doherty FC, Teixeira S, Takeuchi DT, Pandey S (2023) Social and structural vulnerabilities: associations with disaster readiness. Glob Environ Change 78:102638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2023.102638

Rao S, Doherty FC, Traver A, Sheldon M, Sakulich E, Dabelko-Schoeny H (2024) Extreme weather disruptions and emergency preparedness among older adults in Ohio: an eight-county assessment. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 15:213–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-024-00548-8

Rivera JD, Miller DS (2007) Continually neglected: Situating natural disasters in the African American experience. J Black Stud 37(4):502–522

Rodriguez AHA, Shafieezadeh A, Yilmaz A (2022) How important are socioeconomic factors for hurricane performance of power systems? An analysis of disparities through machine learning. Columbus, Ohio, USA. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2208.09063

Saha RK, Bullard RD, Powers LT (2024) Liquefying the Gulf Coast: a cumulative impact assessment of LNG buildout in Louisiana and Texas. Environ Stud Fac Publ 12. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/environstudies_pubs/12

Sotolongo M, Kuhl L, Baker SH (2021) Using environmental justice to inform disaster recovery: vulnerability and electricity restoration in Puerto Rico. Environ Sci Policy 122:59–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.04.004

Sovacool BK, Bell SE, Daggett C, Labuski C, Lennon M, Naylor L, Klinger J, Leonard K, Firestone J (2023) Pluralizing energy justice: incorporating feminist, anti-racist, indigenous, and postcolonial perspectives. Energy Res Soc Sci 97:102996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.102996

SHELDUS (2023) Spatial Hazard Events and Losses Database for the United States, Version 21.0 [Dataset]. Arizona State University Center for Emergency Management and Homeland Security. https://cemhs.asu.edu/sheldus

Spielman SE, Tuccillo J, Folch DC, Schweikert A, Davies R, Wood N, Tate E (2020) Evaluating social vulnerability indicators: criteria and their application to the social vulnerability index. Nat Hazards 100(1):417–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-019-03820-z

Stock A, Davidson RA, Kendra J, Martins VN, Ewing B, Nozick LK, Starbird K, Leon-Corwin M (2023) Household impacts of interruption to electric power and water services. Nat Hazards 115(3):2279–2306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05638-8

Strough J, Parker AM, Ayer L, Parks V, Finucane ML (2024) Aging and emotional well-being after disasters: vulnerability and resilience. Gerontologist 64(3):gnad099. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnad099

Tang T, Kim H (2023) Linking energy policy, energy insecurity, and health outcomes. Front Sustain Energy Policy 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsuep.2023.1231821

Tiwari S (2022) Texas electricity service crisis through an energy justice lens. Electr J 35(9):107204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tej.2022.107204

Tormos-Aponte F, García-López G, Painter MA (2021) Energy inequality and clientelism in the wake of disasters: from colorblind to affirmative power restoration. Energy Policy 158:112550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112550

Uduba R, Gillum R (2024) Social vulnerability index and age-adjusted mortality from all causes by county: Mississippi 2016-2020. J Natl Med Assoc 116(3):302–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2024.05.003

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2017) Power outage incident annex to the response and recovery federal interagency operational plans: managing the cascading impacts from a long-term power outage. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/fema_incident-annex_power-outage.pdf

Voisin N, Kintner-Meyer M, Skaggs R, Nguyen T, Wu D, Dirks J, Xie Y, Hejazi M (2016) Vulnerability of the U.S. western electric grid to hydro-climatological conditions: How bad can it get? Energy 115(Part 1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.08.059

Wickham H (2023) modelr: modelling functions that work with the pipe (version 0.1.11) [computer software]. CRAN. https://modelr.tidyverse.org

Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan L, François R, Grolemund G, Hayes A, Henry L, Hester J, Kuhn M, Pedersen T, Miller E, Bache S, Müller K, Ooms J, Robinson D, Seidel D, Spinu V, Yutani H (2019) Welcome to the Tidyverse. J Open Source Softw 4(43):1686. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01686

Wood E, Sanders M, Frazier T (2021) The practical use of social vulnerability indicators in disaster management. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 63:102464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102464

Zamuda CD, Bilello DE, Carmack J, Davis XJ, Efroymson RA, Goff KM, Hong T, Karimjee A, Loughlin DH, Upchurch S, Voisin N (2023) Energy supply, delivery, and demand. In: Crimmins AR, Avery CW, Easterling DR, Kunkel KE, Stewart BC, Maycock TK (eds) Fifth national climate assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible with support from the Sustainability Institute at the Ohio State University (GR131227).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SR—Conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, resources, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision. SS—Data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. AA—Project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. AR—Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the Ohio State University (Approval number: 2023E0686) on July 25, 2023.

Informed consent

This study used secondary data at the county level and did not involve human participants; therefore, informed consent procedures were not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rao, S., Scaggs, S.A., Asuan, A. et al. Power outages and social vulnerability in the U.S. Gulf Coast: multilevel Bayesian models of outage durations amid rising extreme weather. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 912 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05274-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05274-0