Abstract

Although global food security (SDG2: Zero Hunger) remains a critical challenge, few studies have systematically examined how policy inefficiencies and institutional responses contribute to food insecurity outcomes. This study addresses this gap by analyzing data from 120 countries (2000–2022) via a multicriteria decision analysis framework that integrates data envelopment analysis and quadrant analysis, guided by the pressure–state–response–impact (PSRI) framework. The findings reveal critical regional differences: North America, East Asia, and Europe achieve high food security outcomes, whereas Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia continue to face severe deficits across all dimensions. South America has demonstrated progress in availability and utilization, but struggles with access. A key issue identified is the persistent gap between policy design and implementation. High-income regions achieve strong outcomes due to effective execution, whereas low-income regions experience suboptimal results despite having formal policy frameworks. Furthermore, the multidimensional nature of food insecurity complicates problem-solving, as improvements in one area often fail to address deficiencies in others. Limited market support and weak institutions further exacerbate food insecurity in low-income regions, hindering strategy effectiveness. The study emphasizes the need to bridge the divide between policy formulation and execution, tailor strategies to specific regional contexts, and address systemic weaknesses across all dimensions of food security. These findings offer critical insights into global food security dynamics and inform more effective, equity-oriented approaches to achieving the goal of Zero Hunger.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Food security is a multifaceted global issue that remains a significant challenge despite advances in agricultural productivity and economic growth. Millions of people lack access to adequate, nutritious, and safe food (Kuhl, 2018; Peng et al., 2024). Recent estimates reveal that approximately 9.2% of the world’s population, or 735 million people, suffer from undernourishment, with significant regional disparities (FAO, 2024). Africa bears the highest burden, with nearly 20% of its population living in hunger, followed by Asia (8.5%), Latin America and the Caribbean (6.5%), and Oceania (7.0%) (FAO, 2024). This persistent undernourishment is tracked as SDG 2.1.1 in the 2030 Agenda, which monitors global progress towards achieving zero hunger (FAO, 2020). However, progress has been alarmingly slow, and current trends indicate that the world is unlikely to meet food security targets by 2030. Projections estimate that nearly 600 million people will suffer from chronic undernourishment by 2030, highlighting the urgency of addressing food insecurity as a key component of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (UN SDG) of ending hunger and ensuring food system sustainability (Campi et al., 2021; Capone et al., 2014; Lang and Barling, 2012). As shown in Fig. 1, while Asia is expected to make substantial progress, Latin America and the Caribbean are forecast to stagnate, and hunger in Africa is predicted to increase sharply. These trends emphasize the urgent need for more effective strategies to combat undernourishment, particularly in the regions most affected by food insecurity.

Food security is intrinsically linked to food system sustainability, where the equitable provision of food intersects with environmental, economic, and social dimensions (Chaher et al., 2024). Frameworks such as the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE) and the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES) emphasize that food security goes beyond adequate food availability, focusing on resilient, inclusive, and sustainable food systems that address global challenges such as climate change, economic instability, and social inequality (HLPE, 2020; IPES, 2021). This interconnectedness underscores the need to consider the sustainability of food production, distribution, and consumption practices when addressing food security. Research by Niu et al. (2024) underscores that sustainable food systems rely on a delicate balance between food security outcomes and the conservation of environmental resources, as well as the promotion of economic stability and social equity. Additionally, studies such as those by Zahedi et al. (2024) suggest that specialization in food production can influence the global food security landscape and the sustainability of food systems, highlighting the importance of integrated policy approaches. Overall, these insights show that addressing food security requires not only improving access to food but also ensuring that the entire food system—from production to distribution—supports sustainable outcomes across social, environmental, and economic domains (Guerrieri et al., 2025; Macready et al., 2025).

The realization of food security is shaped by multiple structural, systemic, and external factors. While conflicts, economic shocks, and climate change worsen global food insecurity (Wang et al., 2022; WFP, 2022), systemic barriers such as governance, trade policies, agricultural specialization, and power imbalances also play crucial roles (Baker et al., 2021; Clapp et al., 2022; Even et al., 2024). For example, industrialized agriculture and trade liberalization have worsened food access disparities, marginalizing smallholder farmers and consolidating power in large agribusinesses (Ospina-Alvarez et al., 2024; Schoneveld, 2022). Political and economic structures, along with geopolitical conflicts, disrupt food distribution. In 2022, the Russia–Ukraine war cut Ukraine’s wheat exports by 25%, increasing global wheat prices by 14% and straining supply chains (Behnassi and El Haiba, 2022; G. Huang et al., 2024). Additionally, U.S.‒China trade tensions imposed agricultural tariffs, further increasing food prices, particularly for soybeans and pork (Cheng et al., 2023; Hu et al., 2024). Climate change has worsened food insecurity in East Africa through extreme weather, including prolonged droughts. Droughts in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia have displaced 2.3 million people and reduced crop yields by 30%, with rising temperatures expected to worsen food production by 1.5 °C by 2030 in tropical regions (Baldwin-Cantello et al., 2023; FAO, 2022). Furthermore, economic downturns, exemplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, have severely disrupted the food supply and access (Béné et al., 2021). World Bank (2020) reported that the pandemic pushed 100 million people into extreme poverty in 2020, worsening food insecurity by reducing purchasing power, especially in developing countries. As a result of these interconnected factors, 59 countries are facing acute food insecurity in 2023 (Fig. 2). These crises underscore the need for a comprehensive approach that addresses both immediate shocks and systemic drivers of food insecurity, including inequitable trade policies, weak governance, and sociotechnical barriers (Even et al., 2024; Renaud et al., 2022).

Food security is multidimensional and involves the availability, access, utilization, and stability of food systems (FAO, 2024). Addressing one dimension in isolation often fails to resolve others. Trade-offs and synergies between dimensions are often overlooked (Baldwin-Cantello et al., 2023; Renaud et al., 2022). For example, while global food production is adequate, regional disparities in access persist. As a result, 15% of people in developing countries remain undernourished (Conceição et al., 2016; Giller, 2020). This highlights the need for integrated solutions that consider the interconnectedness of food security and system sustainability. Frameworks by the High-Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) and the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES) stress addressing food security within the broader context of sustainable food systems, including environmental, social, and economic dimensions (Clapp et al., 2022; Karakoc and Konar, 2025; Lang and Barling, 2012). Agricultural specialization may increase productivity but reduce system resilience, increasing dependency on global markets and increasing vulnerability to external shocks (Coomes et al., 2019; Liu, 2023). Moreover, power dynamics and governance failures often perpetuate inequities in food access and utilization, particularly in low-income countries (Pemjean et al., 2024; Queiroz et al., 2021). These systemic challenges demand a deeper understanding of structural barriers and the development of context-specific, holistic strategies to address them.

Food policy plays a crucial role in addressing food insecurity by shaping production, distribution, and access through efficient agricultural systems (FAO, 2024; Giller et al., 2021). Policies supporting agricultural innovation, sustainable farming, and smallholder farmers enhance food production (Roy et al., 2024; Rozi et al., 2025). Distribution policies regulating trade, transport, and market access reduce bottlenecks, ensuring that food reaches vulnerable populations (Maestre et al., 2017; Tchonkouang et al., 2024). Access policies, such as food assistance programs and social safety nets, make nutritious food more affordable for the poor (Dula et al., 2024). The food security approach increasingly shapes global and national policies; for example, China’s Grain Reserve System stabilized its grain supply, with outputs reaching 686.53 billion kilograms in 2023, surpassing 650 billion kilograms for the eighth consecutive year (Donnellon-May and Hongzhou, 2023). India’s National Food Security Act (NFSA), implemented in 2013, has improved the country’s Global Hunger Index (GHI) score from 30.3 in 2013 to 28.7 in 2022 (Gouvea et al., 2022). Additionally, Russia’s Food Security Doctrine has achieved self-sufficiency in key sectors, such as grains (167.6%) and vegetable oil (195.9%), by 2020 (Estrada and Koutronas, 2022). However, the effectiveness of these policies varies significantly across regions. In Brazil, programs such as Bolsa Família and Fome Zero initially reduced hunger and poverty, with undernourishment declining by 82% in 2014. However, by 2020, hunger had resurfaced, affecting more than 60 million people (De Lima et al., 2020; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2024). Moreover, in Africa, the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program (CAADP) has struggled to achieve its objectives, with the number of undernourished people increasing to 250 million (20% of the population) in 2020 (FAO, 2023). These disparities highlight the need for policies that are not only context-specific but also address the systemic barriers that perpetuate food insecurity.

The goal of this study is to examine the current state of global food insecurity while identifying gaps and inefficiencies in food security policies, ultimately providing recommendations to improve the effectiveness of food security strategies. This study contributes to the broader debate on food system sustainability in three key ways. First, while the FAO framework includes multiple dimensions of food security, existing reports often focus on single indicators such as undernourishment and poverty. This study constructs a composite indicator system that evaluates food security progress, providing a more comprehensive and panoramic view of the global food security situation. Second, it identifies significant regional variations in food security, emphasizing the contrasts in food availability and malnutrition rates, which highlight uneven progress and persistent challenges. These variations offer crucial context for understanding disparities in food security outcomes across regions. Third, policies are important factors affecting food security and the sustainability of food systems. Many interventions have indeed been introduced at the global, regional and national levels. Faced with stagnant food security and increasingly severe food system sustainability, we have for the first time constructed an analytical framework for global food insecurity and policy gaps and carried out corresponding assessments, offering concrete assessments and recommendations to better align policies with regional needs, supporting efforts to achieve the SDG 2 target of zero hunger.

Materials and methods

Measures and dimensions of food security

The FAO defines food security as a state where all individuals consistently have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, nutritious food for an active and healthy life (FAO, 2015a). This concept is structured around four interrelated pillars: availability, access, utilization, and stability. Availability refers to the food supply, which includes domestic production, imports, and food reserves (Shobur et al., 2025). Access is influenced by economic capacity, infrastructure, and market dynamics (Al Aziz et al., 2025; FAO, 2015). Utilization pertains to the nutritional value and safety of food, emphasizing proper dietary intake and food safety standards (Di Cosola et al., 2025; UNICEF, 2019). Finally, stability reflects the resilience of food systems to shocks, such as economic crises, conflicts, or climate events, which can disrupt availability, access, or utilization (FAO, 2020; Lara-Arévalo et al., 2023). These pillars are not isolated; rather, they interact dynamically. For example, climate-induced crop failure can reduce food availability (Choquette-Levy et al., 2021), increase prices and limit access (Mirzabaev et al., 2023), whereas poor utilization can lead to malnutrition even when food supplies are sufficient (Fanzo and Miachon, 2023).

Recent research has expanded on the FAO framework by examining food security within broader environmental, socioeconomic, and political contexts shaping food choices—in mediating access and utilization (Herforth and Ahmed, 2015; Turner et al., 2018; Vuong et al., 2023). Additionally, socioeconomic and political factors, including income inequality and governance, shape food security by impacting affordability, market stability, and policy effectiveness (Illien and Bieri, 2024). Achieving food security requires a holistic approach that integrates and interconnects these dimensions (Lucca et al., 2025; Yadav et al., 2024). For example, improving agricultural productivity (availability) without addressing income inequality (access) or food safety (utilization) may fail to reduce malnutrition (Mesfin et al., 2024). Efforts to enhance stability, such as climate-resilient food systems, must address how shocks disproportionately impact vulnerable populations, worsening access and utilization disparities (Kidane et al., 2024).

Interconnected pathways to food security: producer, consumer, and trade policies

Food security policies can be broadly grouped into three categories: producer-oriented, consumer-oriented, and trade-oriented strategies (FAO, 2024) based on the FAO-FAPDA classification.

Producer-oriented policies play a crucial role in strengthening food security by enhancing agricultural productivity and stabilizing supply chains (Fan et al., 2017; FAO, 2015). These policies include measures such as farmer subsidies, investments in agricultural technology, irrigation development, and extension services (FAO, 2020) through subsidies, technological investments, and irrigation development; these policies bolster resilience against climate shocks and market volatility, reinforcing food system stability (Barrett et al., 2019; Demeke et al., 2012; Egli et al., 2021). For example, public procurement at fixed prices incentivizes production, ensuring farmer income while stabilizing food availability and prices (HLPE, 2020). Consumer-oriented policies interact with food security by ensuring affordability and nutritional quality, particularly for vulnerable populations (Balagamwala et al., 2024; FAO, 2022; Gentilini and Omamo, 2011). Measures such as food aid, price controls, and social protection schemes (e.g., cash transfers, food vouchers) improve food access and utilization (FAO, 2020; HLPE, 2020). School feeding programs, for example, enhance both access and nutrition (FAO, 2020; Gentilini and Omamo, 2011; Kangasniemi et al., 2025). For example, school feeding programs enhance food access while promoting better nutrition and health outcomes (Locke et al., 2024; Sharp et al., 2024). Additionally, consumer-oriented policies enhance stability by offering safety nets during economic or environmental crises, ensuring consistent food access for affected populations (Gouel and Gouel, 2013; Oosterveer et al., 2014). Trade-oriented policies play a crucial role in enhancing food security by shaping international trade flows, stabilizing domestic markets, and ensuring a reliable food supply (Aragie et al., 2023; de Oliveira et al., 2024; Mrdalj and El Bilali, 2021). These policies include export restrictions, import tariffs, export subsidies, and participation in bilateral or multilateral trade agreements (FAO, 2023).

These three categories serve as useful analytical tools (FAO, 2020; HLPE, 2020; Pawlak and Kołodziejczak, 2020) and are not mutually exclusive. For example, trade policies often have dual effects: export restrictions may stabilize domestic prices for consumers (Akter, 2022) but lower producer incentives (Burg et al., 2025), while import tariffs protect farmers but increase food costs for vulnerable households (Shobur et al., 2025; Swinnen, 2016). Producer-oriented policies (e.g., input subsidies) may increase availability by increasing yields (FAO, 2023), or if poorly targeted, they can distort trade and reduce access for net food-importing countries (HLPE, 2020). Consumer-focused measures (e.g., food vouchers) directly increase access and utilization (Headey et al., 2024), but their sustainability depends on fiscal policies that do not undermine agricultural investment—a producer concern (Devereux, 2016). This interdependence underscores the necessity of integrated policy design, where coordination across sectors ensures synergies rather than trade-offs (Saad-Filho, 2015; HLPE, 2020).

Analytical framework

Several frameworks analyze food security through availability, access, utilization, and stability. The widely used HLPE framework emphasizes systemic drivers such as environmental change, governance, and economic structures (Guerrieri et al., 2025; HLPE, 2020). Other models focus on sector-specific interventions, emphasizing agricultural productivity, trade policies, and market mechanisms (Cheng et al., 2024; Dai et al., 2025; Tian et al., 2024). However, these approaches may focus less attention on cross-domain integration. To address this shortcoming, this study employs the “pressure–state-response–impact” (PSRI) framework adapted from Song et al. (2023), which systematically links external pressures, food system conditions, policy responses, and their impacts on food security (Fig. 3).

Pressures (drivers)

Food security is shaped by multiple pressures. Institutional and governance factors include such issues as corruption (Gebka et al., 2024). Environmental issues, particularly soil depletion, threaten agricultural productivity (Rizzarelli et al., 2024). Urbanization reduces arable land, disrupts food supply chains, and intensifies demand pressures (Yu et al., 2022). Natural disasters, including droughts, destabilize production and market stability (Yang and Fu, 2025). Finally, inequalities in food distribution, exacerbated by inefficient supply chains, create disparities in food access (John and Singh, 2025).

State (food security dimensions)

The state of food security is assessed through key dimensions. Food availability depends on agricultural output and the ability to maintain a stable supply (Morão, 2025). Food access refers to individuals’ and households’ ability to acquire food via markets, social programs, or direct production (Olagunju et al., 2025). Food utilization involves the quality, safety, and nutritional value of food, which influence health outcomes (OECD, 2022). Unlike some models, this framework integrates stability within these dimensions rather than treating it separately, as evidenced by consistent production, reliable supply chains, and market resilience (Zheng et al., 2025).

Response (policy interventions)

Policy responses mitigate pressures and enhance food security. Producer-oriented policies promote sustainable farming, production support, and infrastructure investment to improve food availability (Ndimbo and Haulle, 2024). Consumer-oriented policies, including market regulation and nutritional assistance programs, strengthen food access and utilization (FAO, 2024). Trade-oriented policies, such as import–export regulations and regional agreements, stabilize supply chains and foster market integration (FAO, 2024). These policy responses interact across multiple levels, shaping national and regional food systems.

Impact (food security outcomes)

Effective policy responses lead to measurable impacts (Saltos and Kristensen, 2025). Increased food availability results from improved agricultural practices and trade integration (Duan et al., 2025). Enhanced food access emerges through economic policies that lower barriers to food acquisition (Haque et al., 2025). Improved food utilization stems from nutritional policies and food safety regulations (Qureshi et al., 2015). Equitable food distribution improves when inefficiencies in supply chains are addressed (Porter and Reay, 2016). Stronger regional trade and market integration create resilient food systems capable of withstanding external shocks (Béné, 2020). By adopting the PSRI framework, this study provides a comprehensive approach for analyzing food security, integrating pressures, system conditions, responses, and impacts.

Data collection and indicator construction

Data. All the data sources are described in Table 3. This study adopts the UN’s food security data sources and indicator system. The dataset spans from 2000 to 2022, with data prior to 2000 excluded owing to limited availability and relevance to current global food security. Data after 2022 is not included because they are unavailable. Indicators and countries with significant missing data were also excluded. After data cleaning, the dataset includes information for 120 countries.

Methods

-

1.

MCDA aids decision-making by evaluating, prioritizing, and selecting alternatives in the presence of conflicting criteria (Alencar and Almeida, 2010; Jeon et al., 2010; Köksalan et al., 2011). MCDA integrates multiple metrics to assess complex issues, generating an overall score to rank or express preferences (Chen et al., 2012; Hansen and Devlin, 2019). Various MCDA techniques have been developed over time (Adem and Geneletti, 2018; Huang et al., 2011; Khan et al., 2022) and are widely applied in food security research (Fazil et al., 2008; Ferla et al., 2024; Gésan-Guiziou et al., 2020). By combining quantitative and qualitative criteria, MCDA provides a robust and transparent approach for addressing food security challenges.

-

2.

Data envelopment analysis was used to assess how efficiently countries convert policy inputs into food security outcomes. As a nonparametric method, DEA evaluates the relative efficiency of decision-making units (DMUs) (Borrás et al., 2024; Kohl et al., 2019)—in this case, countries—by benchmarking them against the best-performing nation. It constructs an ‘efficiency frontier’, identifying countries that achieve the maximum food security outcomes with a given level of policy inputs (Tesafa et al., 2025). Nations on this frontier are deemed fully efficient, whereas others receive efficiency scores based on their relative performance. By deriving benchmarks from real-world best practices, DEA highlights the most effective policy interventions to improve food security. Studies, including Matkovski et al. (2020), which compared food security levels between the Western Balkans and the EU, and Nodin et al. (2022), which assessed rice production efficiency for food security policy planning in Malaysia, underscore the effectiveness of DEA in diagnosing inefficiencies and guiding evidence-based policy improvements.

-

3.

QA complements DEA by categorizing countries into four quadrants based on efficiency scores and food security outcomes. This visual framework simplifies complex data, assisting policy-makers in identifying patterns, outliers, and intervention priorities (Jin et al., 2018). Top-performing countries in the high-efficiency, high-outcome quadrant serve as benchmarks, offering best practices (Jordi et al., 2020). Integrating QA with DEA enhances the interpretability and policy relevance of findings (Ofoghi et al., 2022). While DEA quantifies efficiency, QA translates results into actionable categories, facilitating decision-making (Santamato et al., 2024). This approach, applied in environmental management and public health (Wang et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2022), bridges the gap between data analysis and policy action in food security.

The combined use of MCDA, DDEA, and QA offers a robust framework for assessing global food security. MCDA ensures relevant indicators, DEA benchmarks efficiency, and QA simplifies results for decision-making. Unlike other food security assessment models, such as those by Leroy et al. (2015) and Allee et al. (2021), the Global Food Security Index and FAO’s Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FAO, 2020), which focus on prevalence and experience-based metrics but lack efficiency assessment, this integrated approach offers a more comprehensive and actionable evaluation. The addition of QA is a novel contribution, improving interpretability and policy relevance.

Selection of key indicators for each dimension of food security

The indicators for assessing food security dimensions—availability, access, and utilization—are presented in Table 1. Notably, stability is inherently integrated into and reflected by these three dimensions. Measuring stability independently could be redundant, as its effects are already captured through the consistency and reliability of availability, access, and utilization over time (FAO, 2013; Jones et al., 2013; Manikas et al., 2023). This approach aligns with the FAO’s framework, which emphasizes that stability is a cross-cutting dimension embedded within the other dimensions (FAO, 2018; Leroy et al., 2015).

The availability dimension is assessed using indicators such as dietary energy supply (kcal/cap/day); average dietary energy supply adequacy (percent); the share of dietary energy supply derived from cereals, roots, and tubers (kcal/cap/day); and the average supply of protein of animal origin (g/cap/day). These metrics are critical for evaluating the adequacy of food supplies at the national and global levels (Smith and Haddad, 2015). The dietary energy supply, in particular, is a key indicator for estimating the prevalence of undernourishment and is widely used by the FAO to monitor food security trends (Barrett and Christopher, 2010; FAO, 2022; HLPE, 2020). Other indicators, such as energy supply adequacy and animal protein supply, offer insights but fail to fully represent total energy availability across populations (Porkka et al., 2013; Ritchie et al., 2018).

The access dimension is evaluated using indicators such as political stability, the agriculture orientation index (AOI), food price anomalies, and rail line density. The AOI effectively assesses food access by reflecting agricultural policies’ and investments’ impact on productivity and affordability (Pawlak and Kołodziejczak, 2020; World Bank, 2016) while also serving as a policy evaluation indicator by assessing rural development, smallholder support, and agricultural research (Aragie et al., 2023). Political stability and food price anomalies further complement this dimension by highlighting the role of governance and market dynamics in shaping food access (Barrett et al., 2019).

The utilization dimension examines how effectively individuals convert food into nutrition, considering diet quality, food safety, and health care. Indicators such as childhood stunting (SDG 2.2.1) and malnutrition (SDG 2.2.2) assess this dimension (Black et al., 2013; FAO, 2024; Hoddinott et al., 2013). While these indicators are traditionally linked to health outcomes (Headey and Ecker, 2013; Ijaiya et al., 2024), they are also strongly tied to food utilization (Smith and Haddad, 2015), as they reflect the interplay between dietary intake, nutrient absorption, and environmental factors such as access to clean water and sanitation (UNICEF, 2019; WHO, 2022). Childhood stunting, for example, is a critical measure of chronic malnutrition and serves as a proxy for long-term food utilization challenges (Perumal et al., 2018; Suryawan et al., 2022) and is widely used by global health organizations to assess the impact of nutrition and public health interventions, thereby serving as a measure of food security (UNICEF, 2023a; WHO, 2022).

Approach for selecting and weighting criteria

The criteria for MCDA were chosen for their relevance in assessing food security indicators, each representing a distinct facet of indicator effectiveness (Mazzocchi et al., 2013). Relevance assesses how well an indicator aligns with its core dimension—availability, access, or utilization (Janoušková et al., 2018). Data availability assesses the ease of obtaining reliable data (Costa et al., 2019), whereas sensitivity measures the indicator’s responsiveness to changes (Chuševė et al., 2016). Ease of measurement assesses indicator simplicity, policy impact reflects its potential influence on decisions, and comprehensive coverage measures its scope in representing food security dimensions (Manikas et al., 2023). The scores for each criterion were determined through a qualitative assessment to evaluate each indicator based on existing evidence and practical experience (Rosén et al., 2015).

Weights of indicators

The criteria weights were assigned based on their significance in evaluating indicator effectiveness and utility. A systematic literature review informed these weights, aligning them with established research and global best practices (Grover et al., 2020; Mazzocchi et al., 2013; Mohsin et al., 2024; Talukder et al., 2018). Relevance received the highest weight (0.3) because of its crucial role in aligning indicators with food security dimensions (Izraelov and Silber, 2019). Data availability and sensitivity were each weighted at 0.2, emphasizing their importance in ensuring reliable data access and detecting food security changes (Caccavale and Giuffrida, 2020; Cafiero et al., 2014). Ease of measurement, policy impact, and comprehensive coverage were assigned weights of 0.1 each, reflecting their practical value but secondary importance relative to relevance and sensitivity (Afshar et al., 2020; Rauch et al., 2018). The following equation outlines the process for calculating the total score of each indicator based on the weighted criteria.

Where \({Rev}\) is relevance, \({DA}\) is data availability, \({Sens}\) is sensitivity, \({EoM}\) is ease of measurement, \({PI}\) is policy impact and \({CC}\) is comprehensive coverage.

This process is repeated for each dimension indicator to compute total scores. The indicators are then ranked based on these scores, with the highest-ranking indicators selected for each dimension, thereby identifying the most effective metrics for assessing food availability, access, and utilization. The results are presented in Table 2. The dietary energy supply (kcal/cap/day) is used to estimate undernourishment prevalence and is the most suitable indicator of food availability. It directly reflects food intake adequacy, is highly sensitive to changes in food security conditions, and significantly influences policy by guiding dietary interventions. This measure provides comprehensive coverage of dietary energy sources, ensuring a thorough assessment of food security (FAO, 2022). While average dietary energy supply adequacy and average animal protein supply are important, they do not fully capture total energy availability across communities. The dietary energy supply is the preferred indicator for assessing undernourishment and caloric intake. The FAO emphasizes dietary energy supply as a key measure of food availability, reflecting the food available for consumption, and is widely used to estimate undernourishment (FAO, 2003).

The Agriculture Orientation Index (AOI) serves as a valuable indicator for evaluating the access dimension of food security. It assesses the impact of agricultural policies and investments on productivity and access to food. The AOI reflects policy changes and their direct effects on food access, evaluates the effectiveness of agricultural strategies, and encompasses various activities, such as rural infrastructure, smallholder support, and agricultural research (World Bank, 2016). A study by Aragie et al. (2023) revealed that the AOI effectively gauges the impact of agricultural policies on food security, providing a comprehensive assessment of how these strategies influence food access through their relevance, sensitivity, and broad coverage.

The utilization dimension of food security assesses how effectively the body uses nutrients to maintain health, considering diet quality, food and water safety, and health care (UNICEF, 2023b). Childhood stunting, a critical indicator in this dimension, reflects the interplay of food quality, sanitation, clean water, and health care in determining health outcomes (FAO, 2015). It is used by global health organizations to evaluate the impact of nutrition and public health interventions. Stunting signals chronic malnutrition, encompassing food intake, nutrient absorption, and disease effects (WHO, 2022). The FAO tracks stunting in its annual reports to monitor global food security and nutrition trends (FAO, 2018).

Construction of data envelopment analysis

The primary objective of the DEA in this study is to maximize the efficiency score of each decision-making unit (DMU), defined as the ratio of weighted outputs to weighted inputs, as expressed for a given DMU:

Objective function

where \({\theta }_{k}\) is the efficiency score of DMU \(k\); \({y}_{{jk}}\) is the amount of output \(j\) produced by DMU \(k\) (e.g., availability, access, and utilization); \({x}_{{ik}}\) is the amount of output \(j\) produced by DMU \(k\) (e.g., producer-oriented, consumer-oriented, and trade-oriented); and \({u}_{j}\) and \({v}_{i}\) are the weights assigned to outputs and inputs, respectively, which are determined through the optimization process. To ensure the model’s validity, the following constraints must be satisfied for all the DMUs in the dataset:

Output constraints:

This ensures that the efficiency score of DMU\(k\) is nonnegative and bounded.

Weight constraints:

This condition restricts the weights assigned to inputs and outputs to be nonnegative, reflecting the nature of resource allocation in efficiency measurement.

Normalization constraint:

The variable returns to scale (VRS) output-oriented DEA model is well suited for analyzing the impact of food policies on regional food security, as it considers variations in resources, economic capacities, and policy effectiveness across regions (Djuraeva et al., 2023). Accounting for varying returns to scale, advances in food security may not always follow proportionate increases in resources (Mbow et al., 2020). The output orientation aims to maximize food availability, access, and utilization, providing actionable insights for targeted policy adjustments to improve food security outcomes. The quadrant analysis categorizes countries based on food security outcomes and policy effectiveness, and identifies policy gaps and guides targeted recommendations (Tidd et al., 2022). Integrating DEA and quadrant analysis provides a comprehensive evaluation of global food security strategies.

Results

Analysis of global food security performance

Global food availability performance

The global assessment of food availability, measured by dietary energy supply (kcal per capita per day), indicates a significant improvement across 120 economies in the years 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2022 (Fig. 4a). The number of countries meeting the FAO-recommended dietary energy threshold of 2500 kcal per capita per day increased from 58.3% in 2005 to 77.5% in 2022. This progress reflects a positive trend in food security, with 93 out of 120 economies achieving the minimum dietary energy requirement in 2022. The median food availability increased from 2715 kcal in 2005 to 2791 kcal in 2010 and then decreased slightly to 2775.5 kcal in 2015, before increasing again to 2894 kcal in 2022. Despite these advancements, regional disparities persist, with some countries still struggling to meet the necessary dietary energy levels. Across all four years, North America, South America, Europe, East Asia, and Australia consistently maintained dietary energy supplies above 2500 kcal. In contrast, many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and South Asia remained below this threshold. A few countries, on the one hand, including Peru, Mali, Nigeria, and Botswana, demonstrated substantial improvements in food availability, surpassing the threshold level of 2500 kcal in 2022. Yemen and Madagascar, on the other hand, exhibited alarmingly low levels of food availability throughout the surveyed years, failing to even reach moderate dietary energy supply levels. Some SSA countries, such as Chad, Angola, and Zambia, experienced slight improvements between 2005 and 2022 but continued to fall short of the FAO standard, whereas Venezuela dropped from high food availability to low food availability in 2022.

a World map illustrating the assessed levels of food availability across 120 countries over the period 2005–2022. Countries are classified based on standardized availability scores, highlighting global disparities in caloric supply. b Histogram showing the distribution of food availability scores for the same 120 countries during 2005–2022. This visual representation complements the spatial patterns shown in the world map (a), allowing for a clearer understanding of the frequency and range of national availability levels, offering insight into cross-country variation.

The left-skewed distribution in Fig. 4b further emphasizes that while many nations meet or exceed the recommended dietary energy supply, disparities persist, highlighting the ongoing challenge of food availability. These findings underscore the need for targeted policy interventions to increase food security in the most affected regions.

Global food access performance

The global assessment of food access, measured by the AOI for government expenditures, highlights disparities in how governments prioritize agricultural support and its impact on food access across 120 economies in 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2022 (Fig. 5a). Globally, agricultural support remains uneven, with many countries allocating limited resources to the sector. The analysis reveals that 69% of the countries studied are in the low category, with an AOI below 0.5. There was no significant improvement in food access from 2005 to 2022. The median food access decreased from 0.27 in 2005 to 0.24 in 2010. It then fell further to 0.23 in 2015, before slightly rising to 0.24 in 2022. Regions such as North America, most of Europe, and Australia consistently exhibit strong food access, with AOIs above 0.5 over the years. In contrast, SSA and South Asia face a worsening situation, with the majority of countries below the lower threshold failing to meet even moderate food access levels. South America has shown some improvement between 2005 and 2022, but food access remains limited and uneven across the region. Kazakhstan, India, Mali, Algeria, and Libya initially had high food access. By 2022, they fell below the AOI of 0.25. In contrast, positive developments are seen in countries such as China (data refer exclusively to mainland China; Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan are not included. The same applies hereafter.) and Australia, where food access improved significantly, moving from 0.31 levels in 2005 to 0.89 by 2022.

a World maps illustrating the assessed values of food access across 120 countries from 2005 to 2022. The maps display spatial patterns and disparities in food access performance over time, highlighting global variations and trends in access-related outcomes. b Histograms showing the distribution of food access scores for the same 120 countries across the study period. These visualizations provide a summary of the frequency and spread of access values, offering insights into the overall distribution and comparative performance among countries.

Figure 5b shows that a few countries, such as Germany and Canada, have high food access. In contrast, most countries, including Kenya, India, and Ecuador, face low to moderate access. This persistent disparity underscores the urgent need for targeted policy interventions to improve food access, particularly in regions such as SSA and South Asia, where challenges remain most severe.

Global food utilization performance

The spatial distributions of food utilization across 120 economies for the years 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2022 are shown in Fig. 6a. Food utilization is assessed globally using SDG Indicator 2.2.1, which measures the prevalence of childhood stunting and reveals regional variations in food utilization trends over the surveyed periods. Notably, lower utilization rates indicate better food use, whereas higher rates signify worse outcomes. A significant improvement in global food utilization is observed, reflected in the decline in the average performance score from 0.20 in 2005 to 0.18 in 2022. Regionally, North America, South America, Australia, and Europe recorded low utilization rates, meeting the WHO/UNICEF threshold of less than 10%. In contrast, SSA and South Asia continue to experience high rates of food utilization. The prevalence remained consistently above 0.3 over all four years. In contrast, several countries have shown notable improvements. China, for example, has made significant progress, achieving a lower food utilization rate of 0.05 by 2022. This success aligns with the broader trend in East Asia, where countries such as Japan, with a utilization rate of 0.52, and South Korea, with a utilization rate of 0.08, have also experienced reductions in food utilization rates. Additionally, countries such as Algeria in North Africa, Kazakhstan in East Asia, and Saudi Arabia have reached utilization rates of less than 0.1 in 2022. South America has made progress in terms of food utilization. Countries such as Peru and Uruguay have utilization rates between 0.10 and 0.20. However, these rates remain above the recommended level of less than 0.01. Despite progress, they remain above the desired utilization rate, highlighting ongoing challenges in achieving optimal food utilization. In SSA, countries such as Benin, Burkina Faso, and Chad continue to struggle with higher food utilization rates, underscoring the persistent challenges faced by many nations, with utilization rates as high as 0.3.

a World map visualization of food utilization scores across 120 countries, covering the period from 2005 to 2022. The spatial distribution highlights regional differences in utilization performance, with countries classified based on standardized thresholds. b Histograms depicting the distribution of food utilization scores among the 120 countries for the same period, offering a comparative view of frequency and spread across performance categories.

The increasing skewness in Fig. 6b further supports these trends, indicating that while global stunting rates have declined, the burden remains disproportionately high in specific regions, underscoring the need for targeted interventions where food utilization remains a critical issue.

Distribution of global food security policy

The distribution of policies across different categories—producer, consumer, and trade—reflects significant variations in global policy implementation. Figure 7 presents the average levels of each policy type between 2000 and 2022. Overall, while many countries have implemented trade and producer policies, consumer policies remain notably inadequate in several regions. North America, Europe, Australia, and South Asia recorded high policy levels across all three categories. In contrast, SSA consistently displayed low policy levels across all three policy categories. South America, in addition to Brazil and Colombia, registered a moderately lower focus on consumer policies but higher levels of producer and trade policies. These regional differences highlight a clear disparity in policy implementation levels.

This figure presents a comparative analysis of food security strategies adopted by 120 countries, categorized into three policy orientations: producer-oriented, consumer-oriented, and trade-oriented. a shows the producer-oriented policy level by country. b displays the consumer-oriented policy level by country. c presents the trade-oriented policy level by country.

Assessing the relationship between policy levels and food security outcomes

To assess the impacts of different policy orientations on food security, Fig. 8 presents a series of maps illustrating the relationship between food security policies and outcomes from 2000 to 2022. Figure 8a–c depicts policy use across three orientations—producer-oriented, consumer-oriented, and trade-oriented—each linked to corresponding food security outcomes displayed in the subsequent maps. These outcomes are examined across the three core dimensions of food security: availability, access, and utilization. The analysis reveals widespread policy engagement across regions, though the effectiveness of interventions varies considerably across both policy domains and outcome dimensions. This section explores how different policy orientations have influenced food security outcomes over time and across regions, highlighting patterns of success as well as persistent challenges.

Producer policy on food security dimensions

The impact of producer-oriented policies varies considerably across countries, as shown in Fig. 8a, with corresponding outcomes in Fig. 8(a1, a2, and a3). Globally, food availability shows relatively stronger performance compared to the other dimensions. Regions with high levels of producer-focused policies—such as North America, most of Europe, East Asia, Australia and New Zealand—consistently recorded high performance across all three dimensions. In contrast, South Asia, despite implementing strong producer policies, performed well in terms of food availability but struggled with food access and utilization. The SSA, characterized by low levels of producer-oriented policy support, exhibited poor performance across all three dimensions, with the most pronounced challenges observed in terms of food access and utilization. South America, despite having strong producer policies, performs well in terms of food availability and utilization, but faces challenges in terms of food access. Notably, some countries—such as South Africa, Botswana, Kazakhstan, and Iran—recorded low levels of producer-oriented policies yet managed to achieve relatively strong food availability. Nevertheless, these countries experienced moderate difficulties in terms of food access and utilization.

Consumer policy on food security dimensions

Overall, the impact of consumer-oriented policies shown in Fig. 8b varies significantly across countries, as reflected in the related food security outcomes—availability, access, and utilization—presented in Fig. 8(b1, b2, and b3). These maps highlight considerable disparities in how consumer-focused interventions translate into measurable improvements in food security. While many nations perform well in terms of food availability, access, and utilization remain more challenging, particularly in regions with weaker consumer policies. Regions with strong policies, such as North America, most of Europe, East Asia, and Australia, consistently performed well across all three dimensions. In contrast, South Asia, despite implementing high consumer policies, excelled in availability but struggled with access and utilization, with India lagging in all three areas, particularly utilization. The SSA, where consumer policies are generally weak, shows poor performance across all dimensions, with the greatest deficits in access and utilization. South America presented mixed results. Colombia and Ecuador, despite moderate policy levels, performed well in terms of availability but struggled significantly with access and utilization. Argentina, with moderate policy levels, faced challenges primarily in terms of food access, whereas Brazil, despite strong policies, also experienced difficulties in this area. Mexico and Sweden, both with moderate policy levels, exhibited mixed outcomes—Mexico struggled with utilization slightly exceeding the 10% threshold, whereas Sweden fell short of the minimum AOI of 0.5 in access. South Africa, despite low consumer policy levels, performed relatively well in terms of availability but faced severe challenges in utilization. These findings underscore the critical role of consumer policies in shaping food security. While strong policies support availability, access and utilization require more targeted interventions to ensure equitable food security across all dimensions.

Trade policy on food security dimensions

The impact of trade-oriented policies, shown in Fig. 8c, varies significantly across countries, as reflected in the corresponding food security outcomes presented in Fig. 8(c1, c2, and c3). While many nations perform well in terms of food availability, access, and utilization remain inconsistent across regions. Countries with strong trade policies, such as North America, Europe, East Asia, and Australia, achieve high performance across all three dimensions. In contrast, South Asia, despite strong trade policies, excels in terms of food availability but struggles with access and utilization, particularly in India. Most SSA countries, with weaker trade policies, show poor performance across all dimensions, especially in terms of access and utilization. In North Africa, trade-engaged nations such as Tunisia, Egypt, and Algeria perform well in terms of food availability but continue to face challenges in terms of access and utilization. Similarly, Colombia and Ecuador, with moderate trade policies, succeed in terms of food availability but struggle in other dimensions. Argentina and Brazil, despite strong trade policies, face difficulties in terms of food access, but perform well in terms of availability and utilization. South Africa, with lower trade policy engagement, performs relatively well in terms of food availability while experiencing moderate challenges in terms of access and utilization. These findings underscore the complexity of trade policy effects on food security—while trade can enhance food availability, its impact on access and utilization is not guaranteed. Achieving comprehensive food security requires integrated policies that go beyond trade to ensure equitable food distribution and improved nutritional outcomes.

Policy efficiency analysis and effectiveness

This section assesses the efficiency of producer, consumer, and trade-oriented policies in achieving food security outcomes—availability, access, and utilization—using DEA and QA methods (Fig. 10). DEA evaluates the relative efficiency of countries, where scores range from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating optimal efficiency and lower values highlighting inefficiencies due to poor policy implementation or resource misallocation (Cristóbal et al., 2021). QA complements these findings by categorizing countries into four groups based on policy effectiveness and food security performance: (1) high policy efficiency–high performance (HE&HP), (2) high policy efficiency–low performance (HE&LP), (3) low policy efficiency–high performance (LE&HP), and (4) low policy efficiency–low performance (LE&LP). This dual approach provides a detailed understanding of how these policies impact food security, emphasizing the importance of context-specific strategies for improving policy outcomes (FAO, 2022; Foran et al., 2014; Jiren et al., 2020).

Estimation results of DEA

The DEA analysis evaluates the efficiency of three key food security policies—producer, consumer, and trade—across 120 countries, using food availability, access, and utilization as outputs. The findings reveal significant variations in efficiency levels, with notable regional disparities. The producer policies have the highest efficiency score (0.75), followed by the trade policies score (0.58) and the consumer policies score (0.56).

Among the most efficient countries (United States, Portugal, Poland, China), 41% demonstrate high efficiency in producer policies, 27% in consumer policies, and 28% in trade policies. Conversely, inefficiency is most pronounced in consumer and trade policies, with 47% and 45% of countries, respectively, scoring below 0.50, whereas it is only 1.7% for producer policies. A moderate efficiency level (0.50–0.79) is observed in 58% of countries for producer policies, 27% for consumer policies, and 28% for trade policies. The impact of these policies is evident across the three food security dimensions. Food availability is the most positively influenced factor, with 70.8% of countries meeting the minimum dietary energy requirement of 2500 kcal per capita per day. However, food access remains a challenge, with only 27% of countries achieving a high access index (above 0.50). Similarly, food utilization outcomes remain mixed, as only 30% of countries reach the target level of less than 10% prevalence of stunting. Regional disparities in efficiency are evident, with North America, Europe, Australia, and East Asia consistently achieving high efficiency (≥0.80) across all three policy domains. In contrast, South Asia and SSA exhibit predominantly low efficiency, particularly in terms of consumer and trade-related policies. High-efficiency countries demonstrate balanced performance across producer, consumer, and trade policies, while low-efficiency countries show greater variation, with some excelling in one area but underperforming in others. These findings emphasize the need for region-specific policy interventions to enhance efficiency, particularly in consumer and trade policies, ensuring a more comprehensive and equitable approach to food security.

Estimation results of QA

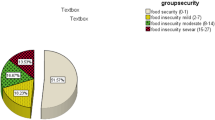

The quadrantal analysis of food security across 120 countries, using producer, consumer, and trade policies as inputs and the three dimensions of food security—availability, access, and utilization—as outputs reveals distinct patterns in policy efficiency and food security performance (Fig. 9). The distribution of countries is relatively balanced across the quadrants for availability and utilization. However, the distribution of access is highly uneven across the four quadrants.

This figure illustrates the relationship between national food security performance and the orientation of food security policies, using a quadrant framework. Countries are plotted based on two axes—food security outcomes (vertical axis) and dominant policy orientation (horizontal axis). a depicts the relationship between availability and producer-oriented policies, b illustrates availability under consumer-oriented policies, and c shows availability within trade-oriented frameworks. d–f correspond to access outcomes under producer-, consumer-, and trade-oriented policies, respectively. Finally, g–i present the relationship between utilization outcomes and the three policy orientations—producer, consumer, and trade, respectively.

In quadrant I (high efficiency–high food security), regions such as North America, East Asia, Australia, and Europe demonstrate strong performance in terms of both policy efficiency and food security. For example, Canada’s efficiency score exceeds 0.8, reflecting the effectiveness of its policies in ensuring high levels of availability, access, and utilization. Quadrant II (high efficiency–low food security) includes South Asian countries such as India, Thailand, and Malaysia. These countries have efficiency scores above 0.8 but struggle with food access and utilization, with India facing significant challenges across all dimensions. Quadrant III (low efficiency–high food security) comprises countries such as South Africa, Botswana, and Iran, which maintain relatively high food security despite lower policy efficiency. In contrast, Quadrant IV (low efficiency–low food security) has a significant concentration of countries, particularly in SSA. Nations such as Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Angola, with efficiency scores below 0.5, exemplify the severe challenges of both low policy efficiency and widespread food insecurity. These findings highlight the complex relationships between producer, consumer, and trade policies and food security. While such policies increase food availability, they do not necessarily improve access and utilization.

Discussion

This study highlights notable regional disparities in food security across availability, access, and utilization factors. Overall, while progress has been made globally, Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia continue to face systemic challenges. Food availability increased from 2005–2022 but declined between 2010 and 2015, likely due to the 2010–2012 global food price crisis. Rising oil prices, biofuel expansion, and supply chain disruptions contributed to this temporary decline (Dalheimer et al., 2021; Declerck et al., 2023; FAO, 2013). Moreover, food access improved little during this period. The 2008 global financial crisis led to reduced agricultural investment and declining household incomes, limiting access to food. Additionally, extreme weather events further disrupt food systems, particularly in vulnerable regions (Chichaibelu et al., 2023; World Bank, 2016). A recurring trend is that economic development alone does not guarantee improvements in food security. High-income regions largely benefit from production support, market management, and social protection programs (Sarkodie et al., 2022; Smith and Floro, 2020).

Countries such as Peru, Mali, and Nigeria have seen improvements in food availability, driven by targeted agricultural reforms. These include sustainable farming practices in Peru (Pizarro et al., 2025; Steinke et al., 2024), improved market management strategies that improve supply chains and food distribution in Mali (Michalscheck et al., 2024), and enhanced domestic food production policies in Nigeria (Akpabio et al., 2025). Yemen’s low food availability is attributed to prolonged political instability, disrupting production support and market structures, and severely weakening agriculture (Jawad et al., 2025; Vesco et al., 2025), whereas Madagascar’s food insecurity is exacerbated by climate vulnerabilities, including recurrent droughts, cyclones, and locust infestations (Abdullahi et al., 2024; FAO, 2018). In contrast, China’s improvement in food access, availability, and utilization is largely due to comprehensive public health and agricultural policies, particularly its self-sufficiency strategy (Ito and Li, 2023; Li et al., 2024). Australia’s progress is similarly driven by advanced agricultural systems that have bolstered both domestic production and food distribution (Churton and McCabe, 2024). Improvements in food availability and utilization in South American countries, such as Peru and Uruguay, are attributed to agricultural reforms, sustainable farming, and public health initiatives (Graeub et al., 2016; Vega-Martinez et al., 2024). However, challenges in food access persist due to limited investment in agricultural infrastructure and ongoing socioeconomic disparities (Martínez-Espiñeira and Pérez-Urdiales, 2025). Despite increased production, issues such as income inequality, political instability, and poor distribution systems impede equitable access, especially in rural and low-income areas (McCarthy et al., 2018; Oecd, 2022).

The study also highlights significant disparities in how producer, consumer, and trade policies impact food security. Countries such as Canada, Australia, and much of Europe benefit from integrated policies that enhance food security across all dimensions, supported by robust agricultural subsidies, efficient market mechanisms, and strong social safety nets (Huan and Liu, 2023; Roy et al., 2024). China exemplifies successful policy-driven improvements in food access and utilization, aligning with research indicating that targeted investments in agriculture and food distribution enhance food security (Zhang and Lu, 2024; Zhang et al., 2023). This underscores the importance of comprehensive policy frameworks—including agricultural support, market access, and consumer protection—in achieving food security. However, policy effectiveness varies widely, with some nations struggling despite high levels of policy implementation. India has implemented comprehensive producer, consumer, and trade policies, yet persistent challenges in food access and utilization remain. Research suggests that income inequality, inefficient food distribution, and infrastructure deficits undermine the effectiveness of these policies (Kruk et al., 2018; Willett et al., 2019). In contrast, countries such as Argentina and Brazil continue to face food access challenges despite comprehensive trade, consumer, and producer policies. These issues are attributed to structural inequities such as economic dependency and racial capitalism (Féliz and Melón, 2023; Rau et al., 2023), which suggest that policy alone is not enough to ensure equitable food distribution. The findings also demonstrate that some countries, such as South Africa, Botswana, and Iran, maintain moderate to high food security despite lower policy efficiency. These cases emphasize that market-driven mechanisms and private-sector involvement can sometimes offset weak policy implementation (Duan et al., 2025; Gani, 2017). However, many SSA countries, including Chad, Angola, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, continue to face severe food insecurity due to low policy efficiency, weak governance, and economic instability (Abdi et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024).

The effectiveness of food security policies is not solely determined by their design but also by how well they are implemented, integrated, and adapted to local conditions (Balis et al., 2024; Mockshell and Ritter, 2024). While some countries achieve high food security through well-executed policies across the producer, consumer, and trade sectors, others continue to struggle due to governance inefficiencies, weak institutional support, and socioeconomic constraints. The DEA and quadrantal analyses reveal that having policies in place does not automatically lead to improved food security outcomes.

Countries such as Canada, Australia, China, and much of Europe benefit from integrated food security policies that balance producer, consumer, and trade strategies. For example, producer policies in Canada and China focus on market management, technological innovation, and subsidies to increase agricultural productivity (Bhatnagar et al., 2024; Chemeris et al., 2022), whereas the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) ensures market stability and farmer protection. In consumer policies, nations such as Denmark, Finland, and Germany use strong welfare systems to support vulnerable populations (Keane et al., 2022; Machefer et al., 2024). However, even countries with high policy efficiency, such as India, still face challenges. Despite policies such as fertilizer subsidies and irrigation schemes, issues such as market inefficiencies and postharvest losses undermine their impact (Gaiha et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2019). Similarly, in Thailand, despite high agricultural output, weak market stabilization mechanisms lead to price volatility (Naruetharadhol et al., 2022). Conversely, countries such as South Africa, Botswana, and Iran maintain relatively high food security despite less efficient policy implementation. These nations benefit from market-driven mechanisms, such as large-scale commercial farming in South Africa and strategic trade agreements in Iran, which help offset weaker government policies (Adenle et al., 2017; Hazell, 2013). However, countries in SSA, such as Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, and Angola, continue to face severe food insecurity due to low policy efficiency, weak governance, and economic instability. These nations struggle with poor agricultural infrastructure, limited irrigation, and inadequate social protection, which exacerbates their food security challenges (Asiedu et al., 2020; Park et al., 2022). The findings highlight that addressing food security requires not only policy formulation but also effective execution that addresses local economic, institutional, and governance issues. Successful policies must prioritize sustainable resource management, market efficiency, improved targeting of consumer policies, and balanced trade strategies to ensure equitable food distribution. The gap between policy formulation and implementation must be closed through multisectoral collaboration and context-specific interventions to achieve meaningful improvements in food security.

Conclusion and policy implications

This study evaluated the global food security performance of 120 countries from 2000 to 2022 via an MCDA approach to assess key indicators across three primary dimensions of food security: availability, access, and utilization. The study also employs DEA and QA methods to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of food security policies.

The findings demonstrated that food security remains an unevenly distributed global challenge, with significant disparities in access and utilization. While some countries have successfully implemented integrated food security strategies, others continue to struggle due to systemic barriers, including weak governance, economic instability, and climate vulnerabilities. High-income nations such as Canada, Australia, China, and much of Europe have leveraged producer-oriented policies, in combination with consumer support mechanisms and trade-oriented policies, to ensure stable food availability and equitable access. In contrast, many low-income countries, particularly those in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, continue to face severe food insecurity due to weak institutional frameworks and inefficient policy implementation. These results align with the FAO (2024), which reports a stagnation in global progress towards universal food access, underlining the urgency of aligning SDG 2 with the core pillars of food security.

A key policy implication of these findings is that successful food security strategies require a multidimensional approach that balances producer, consumer, and trade policies. Countries such as China and Australia exemplify how investments in agricultural productivity, market management, and social protection measures contribute to improved food security outcomes. However, even nations with comprehensive food security policies, such as India, continue to face challenges related to inefficient food distribution. To increase the effectiveness of food security strategies, governments must prioritize context-specific policy adjustments that address localized food security barriers.

While this study provides valuable insights, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations. First, while the research provides a broad global analysis, regional and country-specific policy effectiveness may vary based on economic, social, and political conditions that were not fully explored in this study. Future research could benefit from econometric regression analysis to examine these variables and offer deeper insights into local food security dynamics. Second, while the study highlights gaps between policy formulation and implementation, further research is needed to assess the long-term sustainability and adaptability of current food security strategies in the face of climate change, economic shifts, and geopolitical instability. Nevertheless, the findings of this study, which are based on rigorous estimation, contribute to the understanding of global food security dynamics and offer recommendations for improving policy alignment, ultimately aiming to combat global food insecurity and support the SDG 2 target of zero hunger worldwide.

Data availability

The data is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Abdi AH, Mohamed AA, Mohamed FH (2024) Enhancing food security in sub-Saharan Africa: investigating the role of environmental degradation, food prices, and institutional quality. J Agri Food Res 17:101241

Abdullahi AM, Kalengyo RB, Warsame AA (2024) The unmet demand of food security in East Africa: review of the triple challenges of climate change, economic crises, and conflicts. Discov Sustain 5(1):244

Adem B, Geneletti D (2018) Multi‐criteria decision analysis for nature conservation: a review of 20 years of applications. Methods Ecol Evol 9(1):42–53

Adenle AA, Manning L, Azadi H (2017) Agribusiness innovation: a pathway to sustainable economic growth in Africa. Trends Food Sci Technol 59:88–104

Afshar A, Mohammad, Alam K, Taylor B (2020) Incorporating affordability, efficiency, and quality in the ICT development index: Implications for index building and ICT policymaking. Inf Soc 36(2):71–96

Akpabio ES, Akeju KF, Omotoso KO (2025) E-agriculture and food security in developing countries: beaming the searchlight on Nigeria. Smart Agric Technol 10:100689

Akter S (2022) The effects of food export restrictions on the domestic economy of exporting countries: a review. Glob Food Secur 35:100657

Al Aziz R, Arman MH, Karmaker CL, Morshed SM, Bari AM, Islam ARMT (2025) Exploring the challenges to cope with ripple effects in the perishable food supply chain considering recent disruptions: Implications for urban supply chain resilience. J Open Innov Technol Mark Complex 11(1):100449

Alencar LH, Almeida ATD (2010) A model for selecting project team members using multicriteria group decision making. Pesqui Operacional 30:221–236

Allee A, Lynd LR, Vaze V (2021) Cross-national analysis of food security drivers: comparing results based on the Food Insecurity Experience Scale and Global Food Security Index. Food Security 13(5):1245–1261

Aragie E, Balié J, Morales C, Pauw K (2023) Synergies and trade-offs between agricultural export promotion and food security: evidence from African economies. World Dev 172:106368

Asiedu E, Sadekla SS, Bokpin GA (2020) Aid to Africa’s agriculture towards building physical capital: Empirical evidence and implications for post-COVID-19 food insecurity. World Dev Perspect 20:100269

Baker P, Lacy-Nichols J, Williams O, Labonté R (2021) The political economy of healthy and sustainable food systems: an introduction to a special issue. Int J Health Policy Manag 10(12):734

Balagamwala M, Kuri S, Mejia JGJ, de Pee S (2024) The affordability gap for nutritious diets–how big is it and how to close it? Glob food security 41:100757

Baldwin-Cantello W, Tickner D, Wright M, Clark M, Cornelius S, Ellis K, Matthews N (2023) The triple challenge: synergies, trade-offs and integrated responses for climate, biodiversity, and human wellbeing goals. Clim Policy 23(6):782–799

Balis EL, Yaroch A, Palmer S, Shaw E, Dos Santos PL, Shanks CB (2024) Implementation and impact of perinatal Food is Medicine programs: a qualitative research study. J Acad Nutr Dietetics 124(10):1255–1265.e1221

Barrett, Christopher (2010) Measuring food insecurity. Science 327(5967):825–828

Barrett C, Reardon T, Swinnen J, Zilberman D (2019) Structural transformation and economic development: insights from the agri-food value chain revolution. Cornell University

Behnassi M, El Haiba M (2022) Implications of the Russia–Ukraine war for global food security. Nat Hum Behav 6(6):754–755

Béné C (2020) Resilience of local food systems and links to food security–a review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks. Food Security 12(4):805–822

Béné C, Bakker D, Chavarro MJ, Even B, Melo J, Sonneveld A (2021) Global assessment of the impacts of COVID-19 on food security. Glob Food Security 31:100575

Bhatnagar S, Chaudhary R, Sharma S, Janjhua Y, Thakur P, Sharma P, Keprate A (2024) Exploring the dynamics of climate-smart agricultural practices for sustainable resilience in a changing climate. Environ Sustain Indic 24:100535

Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, Martorell R (2013) Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 382(9890):427–451

Borrás F, Ruiz JL, Sirvent I (2024) Planning improvements through data envelopment analysis (DEA) benchmarking based on a selection of peers. Socio-Econ Plan Sci 95:102020

Burg V, Solgi H, Rezaei F, Pfister S, Roshandel R, Hellweg S (2025) Is ‘local food’best? Evaluating agricultural greenhouses in Switzerland as an alternative to imports for reducing carbon footprint. Resour Environ Sustain 20:100209

Caccavale OM, Giuffrida V (2020) The Proteus composite index: towards a better metric for global food security. World Dev 126:104709

Cafiero C, Melgar‐Quiñonez HR, Ballard TJ, Kepple AW (2014) Validity and reliability of food security measures. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1331(1):230–248

Campi M, Dueñas M, Fagiolo G (2021) Specialization in food production affects global food security and food systems sustainability. World Dev 141:105411

Capone R, El Bilali H, Debs P, Cardone G, Driouech N (2014) Food system sustainability and food security: connecting the dots. In Iocola I (Ed.), Mediterranean diet and food security: Linking consumption, production and local development (pp. 1–12). CIHEAM/FAO/BCFN

Chaher, NEH, Nassour, A, & Nelles, M (2024) The (FWE) 2 nexus: Bridging food, food waste, water, energy, and ecosystems for circular systems and sustainable development. Trends in food science & technology, 104788

Chemeris A, Liu Y, Ker AP (2022) Insurance subsidies, climate change, and innovation: Implications for crop yield resiliency. Food Policy 108:102232

Chen Y, Kilgour DM, Hipel KW (2012) A decision rule aggregation approach to multiple criteria-multiple participant sorting. Group Decis Negotiation 21:727–745

Cheng D, Liu Y, Zhao W (2024) The impact of agricultural trade on green technological innovation in China’s agricultural sector. iScience 27(11):109876

Cheng NWM, Hasanov AS, Poon WC, Bouri E (2023) The US-China trade war and the volatility linkages between energy and agricultural commodities. Energy Econ 120:106605

Chichaibelu BB, Bekchanov M, von Braun J, Torero M (2023) The global cost of reaching a world without hunger: Investment costs and policy action opportunities. Sci Innov Food Syst Transform 6(25):625–640

Choquette-Levy N, Wildemeersch M, Oppenheimer M, Levin SA (2021) Risk transfer policies and climate-induced immobility among smallholder farmers. Nat Clim change 11(12):1046–1054

Churton H, McCabe BK (2024) Advancing a food loss and waste bioproduct industry: a critical review of policy approaches for application in an Australian context. Heliyon 10(12):e20103

Chuševė R, Nygård H, Vaičiūtė D, Daunys D, Zaiko A (2016) Application of signal detection theory approach for setting thresholds in benthic quality assessments. Ecol Indic 60:420–427

Clapp J, Moseley WG, Burlingame B, Termine P (2022) The case for a six-dimensional food security framework. Food Policy 106:102164

Conceição P, Levine S, Lipton M, Warren-Rodríguez A (2016) Toward a food secure future: Ensuring food security for sustainable human development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy 60:1–9

Coomes OT, Barham BL, MacDonald GK, Ramankutty N, Chavas J-P (2019) Leveraging total factor productivity growth for sustainable and resilient farming. Nat Sustain 2(1):22–28

Costa C, Freitas Â, Stefanik I, Krafft T, Pilot E, Morrison J, Santana P (2019) Evaluation of data availability on population health indicators at the regional level across the European Union. Popul health Metr 17(1):1–15

Cristóbal J, Ehrenstein M, Domínguez-Ramos A, Galán-Martín Á, Pozo C, Margallo M, Guillén-Gosálbez G (2021) Unraveling the links between public spending and Sustainable Development Goals: Insights from data envelopment analysis. Sci Total Environ 786:147459

Dai S, Tang D, Li Y, Lu H (2025) Digital trade, trade openness, FDI, and green total factor productivity. Int Rev Financ Anal 97:103777

Dalheimer B, Herwartz H, Lange A (2021) The threat of oil market turmoils to food price stability in Sub-Saharan Africa. Energy Econ 93:105029

De Lima ACB, Brondízio E, Nardoto GB, Do Nascimento ACS (2020) Conditional cash transfers in the Amazon: from the nutrition transition to complex dietary behavior change. Ecol food Nutr 59(2):130–153

de Oliveira SEC, Visentin JC, Pavani BF, Branco PD, de Maria M, Loyola R (2024) The European Union-Mercosur Free Trade Agreement as a tool for environmentally sustainable land use governance. Environ Sci Policy 161:103875

Declerck F, Hikouatcha P, Tchoffo G, Tédongap R (2023) Biofuel policies and their ripple effects: an analysis of vegetable oil price dynamics and global consumer responses. Energy Econ 128:107127

Demeke M, Dawe D, Tefft J, Ferede T, Bell W (2012) Stabilizing price incentives for staple grain producers in the context of broader agricultural policies: Debates and country experiences. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Devereux S (2016) Social protection for enhanced food security in sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy 60:52–62

Di Cosola F, Petrontino A, Frem M, Tria E, Bozzo F (2025) Boosting market appeal: exploring the impact of nutritional claims on popular Italian dietary cereal product. J Agri Food Res 20:101751

Djuraeva M, Bobojonov I, Kuhn L, Glauben T (2023) The impact of agricultural extension type and form on technical efficiency under transition: an empirical assessment of wheat production in Uzbekistan. Econ Anal Policy 77:203–221

Donnellon-May G, Hongzhou Z (2023) What do we really know about China’s food security? The Diplomat, 7

Duan K, Khan NU, Liu H, Ariza-Montes A, Gil-Marín M (2025) Environmental implications of improving global value chain participation via trade diversification: offsetting the effects of resource rents. J Environ Manag 379:124757