Abstract

The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework has been developed to address students’ differences and meet their learning needs to promote inclusive education development. Although some empirical studies investigated professionals’ beliefs toward the UDL framework and how beliefs influence their practices, most research focused more on in-service teachers’ beliefs and practices than pre-service teachers. Teacher candidates are future teachers, so their beliefs and practices in teacher education programmes may form their teaching philosophy and practices in future teaching. Also, there has been no clear systematic understanding of how pre-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework influence their practices to support the inclusion of students with disabilities. This study used a scoping review methodology to locate previous studies about pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework published in peer-reviewed journals in the past ten years (2014–2024). The data analysis conceptualised three themes, adaptation and inclusion, equity and access, and being active and flexible, to understand pre-service teachers’ beliefs of the UDL framework. The predictors and factors influencing pre-service teachers’ practices using the UDL framework were outlined. However, some challenges and barriers, including the lack of resources, classroom management, and rigid curriculum, influenced the effectiveness of pre-service teachers’ use of the UDL framework. The implications for future research and the recommendations for teacher education programmes in inclusive education are also provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child are pivotal in the global initiative for inclusive education. This initiative, aiming for ‘education for all’, ensures that all children, regardless of disabilities or marginalised backgrounds, can access a high-quality education free from discrimination. As a result, more children with disabilities are now part of mainstream schools, necessitating a pedagogical shift for mainstream education teachers to foster their confidence and self-efficacy in implementing inclusive practices (Boyle et al., 2023). The ‘true’ inclusion for students with disabilities is far more than physically allocating those students in mainstream classrooms, and it requires ensuring equitable access to the curriculum and learning environment, meaningful participation in all classroom activities alongside peers, and genuine opportunities for progress and achievement. Hence, when implementing inclusive practices, mainstream education teachers must adopt a new accessible model that can meet the needs of all students, promote equity in society, and replace the traditional ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021a).

The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework was initiated by the concept of Universal Design (UD) in architecture. Ronald Mace, an architect with a physical impairment, created UD in 1985 to advocate an inclusive philosophy, which encouraged products to be more usable by everyone and emphasised that designing environments or products should meet people’s diversity rather than working towards the average human (Gargiulo & Metcalf, 2023). In the 2000s, Meyer et al. (2014) at the Centre for Applied Special Technology (CAST) in the United States extended the UD concept to the educational field to guide teachers’ teaching practices to become accessible and flexible. The UDL framework is a powerful tool for achieving the goals of full inclusion for all students, including students with disabilities, by proactively designing curriculum to meet students’ diverse needs. According to ‘UDL Guidelines 3.0’, which was updated in 2024, the UDL framework is based on three core principles, including ‘designing multiple means of representation’, ‘designing multiple means of action and expression’, and ‘designing multiple means of engagement’ (CAST, 2024). ‘Designing multiple means of representation’ explains the ‘what’ of learning, which means that teachers should present information or knowledge in various ways to make content more accessible for students. ‘Designing multiple means of action and expression’ solves ‘how’ of learning and gives teachers guidelines to design options for students to express and communicate what they have learned in the learning context. ‘Designing multiple means of engagement’ emphasises the ‘why’ of learning and encourages teachers to stimulate interest in learning to ensure that all students can engage in classroom activities in flexible and accessible ways. The UDL framework can guide teachers in designing the curricula, materials, assessments, and environment through these principles, and the UDL framework may proactively remove barriers and support learners with diverse needs with optimal access, participation, engagement, and progress.

Previously, the UDL theory focused on teachers’ UDL practices and classroom behaviours (Rose & Meyer, 2002). However, one of the most recent and essential theoretical shifts in the UDL theory from 2014 is to consider teachers’ emotional activities or philosophies of teaching (Meyer et al., 2014). Teachers’ pedagogical thinking or beliefs are critical when implementing the UDL framework (Meyer et al., 2014). Teacher beliefs are complex and context-dependent constructs that are shaped by cultural norms, policy environment, prior experiences, and instructional resources (Pajares, 1992). Teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education for students with disabilities, encompassing views on equity, responsibility, and perceived capability, are particularly influential predictors of practice (Sharma & Sokal, 2016). Sharma (2011) provided the ‘3H Framework’ for inclusive education, which emphasised that teachers’ hearts (beliefs and values), heads (knowledge and skills), and hands (practical approaches) should be in harmony to achieve successful inclusive education in the classrooms. As such, teachers’ beliefs (hearts) influence how teachers interpret information (heads) and act (hands) in the classrooms (Five & Buehl, 2012). According to Jordan (2018), teachers who believed they had a responsibility to create access to a flexible curriculum for students were more likely to make accommodations or adjustments to the curriculum design and make them practical for all students. Thus, teachers’ beliefs and values are one of the most critical components to influence their teaching philosophy and practices (Han & Cumming, 2022).

Meyer et al. (2014) stressed that three components, including growth mindset, self-efficacy, and self-regulation and motivation, formed the new teaching philosophy of the UDL framework. Firstly, Leroy et al.’s (2007) study showed that teachers with a growth mindset were more inclined to promote supportive practices to meet the needs of students in the classrooms. Secondly, based on Bandura’s (1982) social cognitive theory, teachers’ self-efficacy influenced their behaviours and actions. As such, teachers with a strong sense of self-efficacy tend to implement more student-centred approaches, which may predict the successful implementation of inclusive practices for students with disabilities (Mojavezi & Tamiz, 2012). Thirdly, research showed that teachers who adopt an autonomy-supportive teaching style that emphasised students’ engagement and participation significantly impact students’ learning outcomes (Assor et al., 2005; Reeve, 2009). Teachers under these three teaching philosophies can guide teachers’ practice in implementing the UDL framework. Also, these philosophies are therefore not just outcomes but essential targets of pre-service training in the UDL framework and inclusion, as they directly influence a teacher’s willingness and ability to create a truly inclusive learning environment for all students.

Although teachers can develop their professional skills and knowledge during in-service professional development, Sharma (2018) stressed that pre-service teacher education was the most significant stage in developing harmony among all three ‘H’ domains: teachers’ hearts, heads, and hands. Firstly, in terms of beliefs and values (‘hearts’), training must actively cultivate a growth mindset regarding student potential and teacher capability, strengthen self-efficacy for inclusive practices and the UDL implementation, and foster core values of equity, belonging, and the belief that all students can learn in the general education environment with appropriate supports. Secondly, regarding the knowledge and skills (‘heads’), fundamental knowledge in pre-service training must include understanding the diverse learning needs of students with disabilities, the principles and guidelines of the UDL framework, accessible principles, and differentiation strategies. Thirdly, practical approaches (‘hands’) should be provided in the teacher education programme; for instance, training must provide extensive and scaffolded opportunities for practice. This integrated approach can ensure that pre-service teachers develop not only the technical skills to implement the UDL framework but also the underlying philosophies for sustained commitment to full inclusion for all students. Hergott (2020) emphasised that teacher preparation could equip teachers with knowledge, skills, and strategies to teach students with disabilities and achieve ‘true’ inclusion. Indeed, pre-service teachers could acquire knowledge in inclusive education from practicum experiences, coursework, and discussions with peers (Tannehill & Macphail, 2014). However, much research found that pre-service teachers faced extreme teaching challenges in inclusive classrooms. Hehir et al. (2016) and Van Mieghem et al. (2020) found that pre-service teachers who had internships in mainstream settings had difficulties addressing students’ individual needs, mainly when they taught in heterogeneous learning groups. Nevertheless, pre-service teachers’ preparedness is essential to form positive self-efficacy beliefs towards inclusive education and lead to a successful inclusive education (Ahsan & Sharma, 2018). Weber and Greiner’s (2019) study showed that pre-service teachers had more positive experiences and beliefs about inclusive education during practicum if they received appropriate training and support from university supervisors. Hence, exploring pre-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework is significant in informing university course design in teacher education to support future teachers in developing the necessary knowledge, beliefs, and practical skills in inclusive education.

Some empirical studies investigated pre-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework and how their beliefs influenced their teaching practices. For example, Griful-Freixenet et al. (2021a) and Reinhardt et al. (2023) explored pre-service teachers’ preparation and experiences in implementing the UDL framework. Also, Griful-Freixenet et al. (2021b) investigated pre-service teachers’ beliefs and practices between the UDL framework and differentiated instruction. However, there is a lack of review studies to summarise and conceptualise pre-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework. When conducting the literature review, it is surprising that only one study, Rusconi and Squillaci (2023), used a systematic review methodology to explore how professional development influenced teachers’ completeness of using the UDL framework. Undeniably, in-service training differs significantly from coursework that teacher candidates conduct in teacher education programmes due to its length, trainer and trainees, and systematicness. Therefore, it is necessary to have a clear and systematic understanding of how pre-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework influence their practices to support the inclusion of students with disabilities.

The primary purpose of the present review study was to fill the gap, construct an explicit model of pre-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework, and analyse how their beliefs affect implementing practices that foster the inclusion of students with disabilities in mainstream settings. Therefore, one research question could guide the current review: What are pre-service teachers’ beliefs about implementing the UDL framework to support inclusive education for students with disabilities? The authors believed that a clear understanding of pre-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework could not only guide pre-service teachers’ practices in creating genuinely inclusive classrooms for all students, including students with disabilities, but also might inform teacher education course design in inclusive education. It is important to note that inclusive education systems often involve students with disabilities spending time in both mainstream classrooms and special education settings. This review focused on pre-service teachers’ beliefs, whether majoring in general or special education, for facilitating inclusion during instructional time.

Research methodology

This study employed a scoping review methodology to identify research gaps and summarise findings from existing literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Munn et al., 2018). Munn et al. (2018) asserted that scoping reviews are particularly suited for gathering evidence to inform practice and identifying specific study characteristics and concepts. Compared to systematic reviews, scoping reviews can address broader topics and research questions; thus, this study aims to examine the scope of included studies rather than assess the effectiveness of teaching strategies or evidence-based practices (EBPs). Therefore, a scoping review is the most appropriate approach to explore pre-service teachers’ beliefs regarding the UDL framework. Following Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework, the study adhered to five steps: (a) identifying research questions, (b) locating relevant studies, (c) selecting studies, (d) charting and analysing the data, and (e) summarising and reporting the research results.

The search strategy

The authors adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines to locate relevant literature in peer-reviewed journals, ensuring the study’s reproducibility and rigour (Moher et al., 2009). Four major electronic databases in Education and Social Sciences – Web of Science, EBSCO Education, ProQuest Education, and Scopus – were utilised to identify literature specifically focused on pre-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework and its influence on their implementation practices. Only empirical studies published between 2014 and 2024 were included to ensure currency. The reasons to only include studies in the last ten years are 1) the theoretical shifts in the UDL framework from analysing the effectiveness of the UDL framework in the 2000s to exploring teachers’ perceptions and philosophies of the UDL framework from 2014 (Meyer et al., 2014), so the researchers believed that finding the studies after 2014 was more appropriate to achieve the objectives of current review; and 2) the researchers intended to find the most recent literature to investigate pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework, as traditional teaching practices is much different from the recent course curriculum design. Search terms related to pre-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework included: (“pre-service teacher” OR “teacher education” OR “teacher candidate” OR “pre-service educator”), (belie* OR perception OR perspective OR attitude), and (“universal design for learning” OR UDL), combined using the Boolean operator ‘AND’.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for screening relevant articles comprised studies that (a) involved pre-service teachers, (b) focused on their beliefs, (c) examined beliefs related to the UDL framework, (d) were published in peer-reviewed journals, (e) were written in English, and (f) were empirical research published within the last ten years (2014-2024). This timeframe was chosen to reflect the current understanding of pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework.

Conversely, the exclusion criteria eliminated articles that (a) were not in English, (b) were not peer-reviewed, (c) focused on in-service teachers, (d) did not explore beliefs about the UDL framework, (e) compared different teaching strategies or EBPs, (f) were duplicates, (g) fell outside the 2014-2024 publication range, and (h) included reviews, commentaries, or grey literature. Excluding grey literature was essential, as it often pertains to government reports or policy statements, which typically do not investigate pre-service teachers’ beliefs regarding the UDL framework.

Study selection

The first author utilised the scoping review framework to conduct a comprehensive database search and select relevant articles. She entered predetermined search terms into each database and organised the findings by creating a table in Microsoft Word, where she copied and pasted article titles, abstracts, and links. Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts for initial screening. They documented their results in a spreadsheet that included article titles, abstracts, justifications for inclusion or exclusion, and detailed lists of each inclusion criterion. The authors compared their results after the initial screening and resolved any discrepancies. The selected articles were then subjected to full-text screening, which adhered to the same procedures as the initial review. Eight articles that met all inclusion criteria were selected for this scoping review. Figure 1 visually represents each stage of the screening process according to the PRISMA guidelines.

Flow Diagram of Search Results [in Line with PRISMA Guidelines (PRISMA’s Four Phases Flow Information Diagram of A Systematic Review)] (Moher et al., 2009).

Data analysis procedures

Data from the selected articles were analysed using a thematic analysis approach, which was adequate for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns within qualitative data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This approach is particularly suited for exploring beliefs in teaching and learning contexts. The results and discussion sections of the selected articles were thoroughly examined to identify codes, categories, and themes. Each article was read at least three times: the first for comprehension, the second for inductive coding, and the third for reviewing and refining codes. To enhance reliability, two authors independently coded one qualitative and one quantitative study, comparing their results. The first author then applied consistent coding standards to all selected articles. Finally, the authors discussed and resolved disagreements regarding codes and categories, condensing them into themes that encapsulate pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework.

Research results

Demographics

Only eight studies that met the inclusion criteria were selected for the current scoping review. Three studies used a qualitative approach, three employed a quantitative approach, and two applied a mixed-method design to explore pre-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework. The researchers then aimed to explore how these beliefs influence their teaching practices during the internship or practicum. After the full-text review, five studies were conducted in the United States in North America, two in Belgium in Europe, and one in Chile in South America. Since the UDL framework originated in the United States, there seems to be an increasing number of researchers who have focused their research on the UDL framework in the United States. Although only eight studies met the selection criteria to investigate per-service teachers’ beliefs, six were conducted in and after 2020, and only two were before 2020; one was in 2018, and one was in 2019. This indicates that fewer researchers have focused on pre-service teachers’ beliefs when researching the UDL framework, as most studies have paid attention to in-service teachers’ beliefs and practices in implementing the UDL framework (Han & Lei, 2024). However, it is fortunate that more and more researchers after 2020 have started to realise the importance of pre-service teacher groups and focused on how their beliefs influence their practices during internship and future teaching. Table 1 provides detailed information about each selected study.

Analytical results

After using the thematic analysis to analyse the eight selected articles, 34 codes and 15 categories were generated from the selected articles. Then, 15 categories were condensed into three themes to conceptualise pre-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework, including (a) adaptation and inclusion, (b) equity and access, and (c) active and flexible. Each theme was described separately in the following sections to align with the research questions of the scoping review.

Adaptation and inclusion

During the interview, some pre-service teachers mentioned that their practices should be inclusive and make adaptations during curriculum design, including adjustments and accommodations (Barahona et al., 2023; Takemae et al., 2018). Three pre-service teachers believed that educators should find different ways, such as the UDL framework, to make classroom changes or adjustments to ensure that all children, including children with and without disabilities, were engaged in the teaching content. This means that the UDL framework is a tool for pre-service teachers to use to promote inclusion. For instance, a pre-service teacher stressed, “I used the UDL principles to provide instruction to students with and without disabilities in my class” (Scott et al., 2022, p. 343). This statement shows that the UDL framework is not only for students with disabilities or special needs, but also for engaging all students in the classroom regardless of their disability status. Also, knowing students well and addressing students’ strengths and interests was highlighted by participants in Barahona et al.’s (2023), Takemae et al.’s (2018), and Mackey et al.’s (2023) studies. As such, some pre-service teachers thought the UDL framework could be used to develop learner-centred pedagogy and learning environment, and then individualised education could be promoted via the UDL framework (Takemae et al., 2018).

Many pre-service teachers believed that the UDL framework was significant in addressing the diversity and differences of all students (Barahona et al., 2023; Takemae et al., 2018; Lee & Griffin, 2021). Two pre-service teachers in Lee and Griffin’s (2021) study indicated that the UDL framework might support their lesson design and planning to reach all students and engage students in learning in diverse ways. Moreover, some pre-service teachers felt that the UDL framework could make them realise and consider the uniqueness of students and help teachers distinguish and differentiate between students (Barahona et al., 2023; Takemae et al., 2018). Five pre-service teachers emphasised the UDL framework, which could promote student autonomy, during the interviews (Barahona et al., 2023; Takemae et al., 2018; Mackey et al., 2023; Lee & Griffin, 2021). Pre-service teachers thought that the UDL framework encouraged them to provide options for students during teaching practices, and the options could improve students’ autonomy and increase their engagement during the instruction (Barahona et al., 2023; Lee & Griffin, 2021). Thus, to encourage students to express their understanding of the course contents, pre-service teachers should provide students with options to improve their confidence in responding to the queries and demonstrating their answers (Barahona et al., 2023; Takemae et al., 2018).

Equity and access

According to the central theme of the UDL framework, a significant objective is to ensure flexible access to all children. Indeed, three pre-service teachers in Griful-Freixenet et al.’s (2021a) and Takemae et al.’s (2018) studies mentioned that the UDL framework guided them to address the access to make content, materials, and environment accessible for students who need multiple means of representation, expression, and engagement. On the one hand, improving the accessibility of lessons is essential for students’ learning. On the other hand, some pre-service teachers believed that the UDL framework could support students’ independence in the learning process, as teachers could teach students to use different resources provided in the classrooms rather than relying on teacher support to complete the tasks (Barahona et al., 2023; Takemae et al., 2018; Mackey et al., 2023). For example, one pre-service teacher pointed out that. “I think now, how am I going to represent this problem in a different way to make sure he gets this so he can do it on his own” (Mackey et al., 2023). This also shows that many pre-service teachers used the ‘representation’ principle more frequently than the other UDL principles, which were ‘action and expression’ and ‘engagement’.

The inclusive education principle often highlights that teachers should be responsive and meet students’ needs. Thus, seven pre-service teachers from Barahona et al.’s (2023), Scott et al.’s (2022), Takemae et al.’s (2018), and Mackey et al.’s (2023) studies mentioned that the UDL framework could guide their teaching practices to connect students’ needs and demonstrate responsiveness to students with varied needs.

Being active and flexible

Some pre-service teachers mentioned intentional teaching, including intentional lesson design and being explicit and precise, in Takemae et al.’s (2018) and Lowrey et al.’s (2019) studies. They believed that the UDL framework often made them think about the course design to ensure that the teaching, accommodation, and modification were engaging (Takemae et al., 2018). For instance, one participant said, “I plan to make sure my directions are obvious and easy for students to understand.” (Lowrey et al., 2019, p. 271). Hence, three pre-service teachers believed that three principles, representation, action and expression, and engagement, were interrelated, and teachers should combine the UDL framework with other teaching strategies to not only meet students’ needs but also motivate students’ learning interests (Takemae et al., 2018; Mackey et al., 2023).

In addition, many pre-service teachers thought the UDL framework could ensure their teaching practices were more flexible and meaningful (Takemae et al., 2018; Scott et al., 2022). Based on the three principles of the UDL framework, pre-service teachers believed that the framework provided opportunities for them to consider how to connect prior knowledge in teaching practices and then scaffold students’ learning processes (Takemae et al., 2018; Mackey et al., 2023). Indeed, pre-service teachers have always discussed course design and teaching practices. However, it is essential to note that some pre-service teachers believed that establishing a comfortable and inquisitive environment and providing sufficient and different resources were also necessary to ensure successful inclusion (Mackey et al., 2023). Thus, two participants in Mackey et al.’s (2023) study thought that the UDL framework could provide psychological safety for students, as the framework guided teachers to design relevant courses and environments and respond to students’ questions appropriately; then, students might not be afraid to be wrong. Some pre-service teachers also highlighted that the UDL framework provided guiding principles for them, and they started to realise how important it is for real-world application during teaching (Takemae et al., 2018). Providing sufficient participation opportunities and specific feedback were mentioned by some pre-service teachers in selected research (Lowrey et al., 2019). One pre-service teacher in Lowrey et al.’s (2019) study said, “I feel I need to be more specific with feedback that I give the students” after learning the UDL framework (p. 271). It shows that many pre-service teachers had a favourable disposition and commitment to implement the three principles of the UDL framework and were willing to apply the UDL framework to their practicum or internship (Barahona et al., 2023; Lee & Griffin, 2021). Some pre-service teachers had a firm intention to seek opportunities to grow professionally by developing the knowledge and skills needed to implement the UDL framework.

Discussion

Gaps in the literature

This scoping review explored the gaps in the literature focused on pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework. It is important to note that most studies about pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework were conducted in the last three years and after 2020. On the one hand, this situation is aligned with Meyer et al. (2014), who stated that the most critical and recent theoretical development of the UDL framework was to investigate teachers’ beliefs or philosophies about UDL practices. On the other hand, although it is well-known that teachers’ teaching philosophy and beliefs emerge from teacher education, it cannot be ignored that most attention to the beliefs of the UDL framework has been paid to the in-service teachers (Han & Lei, 2024). This is because there have been only a few courses about inclusive education and the UDL framework provided in teacher education programmes. Few teacher education candidates receive sufficient training in the UDL framework during their undergraduate or postgraduate studies. Also, there is a lack of research to compare pre-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework among university majors and study levels. The answers to the research questions were clearly explained in the research results. However, there was a general lack of literature on the topic, as only eight relevant studies met the selection criteria for this review. Further, most studies on this topic were conducted in the United States, and a few were in Europe and South America. This indicates a lack of research in the Asia-Pacific Region, and more studies should be conducted in the future to find how cultures and education systems influence pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework. After reviewing the selected literature, it is interesting to note that several predictors and factors influenced pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework, and the pre-service teachers also stressed some challenges and barriers when implementing the framework.

The predictors of implementing the UDL framework

Most pre-service teachers in the selected studies felt that self-efficacy, self-regulation and motivation, and a growth mindset were three essential predictors to allow them to implement the UDL framework during practices (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021b; Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021a; Takemae et al., 2018; Lowrey et al., 2019). Implementing the UDL framework requires confidence in designing flexible pathways (self-efficacy), a belief in one’s capacity to learn complex design principles (growth mindset), and the sustained drive to address variability (self-regulation/motivation) proactively. Indeed, teachers’ self-efficacy has progressively gained much attention in education research and provided implications for teachers’ teaching practices and students’ academic achievement and social-emotional competence (Klassen & Tze, 2014). According to Bandura’s (1977) social-cognitive theory, self-efficacy refers to teachers’ belief in their abilities to successfully deal with tasks and challenges within their professional roles. Sharma et al. (2012) indicated that self-efficacy has consistently been recognised as one of the most critical predictors for teachers to create inclusive classroom environments and implement inclusive teaching practices. Unsurprisingly, as future teachers, pre-service teachers believed that having strong or positive self-efficacy was necessary to apply inclusive practices, such as the UDL framework, in their teaching practices (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021a). These findings are aligned with previous research by Soodak et al. (1998), who highlighted that teachers’ self-efficacy was a strong predictor of inclusion, and Chen (2010) stressed that teachers who had high-level self-efficacy for teaching were more likely to use modern and advanced teaching approaches, preferring more student-centred pedagogies. Thus, pre-service teachers in the current review thought that feeling efficacious in using the UDL framework to design inclusive courses or environments should be their priority in teaching practices, as the UDL framework could guide their lesson design to meet all students’ learning needs (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021b; Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021a). The three principles of the UDL framework, including the multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagement, emphasise flexibility and access, so it shows that most pre-service teachers who believed that the efficacious UDL practices might have high self-efficacy to implement this so-called modern and inclusive teaching approach better to meet the learning needs of all their students.

The one prerequisite for pre-service teachers with high self-efficacy to implement the UDL framework is to gain sufficient understanding and knowledge about it and believe that it can effectively meet students’ learning needs and guide their inclusive teaching practices. The intention to grow professionally should be the second significant predictor of implementing the UDL framework. Several pre-service teachers in the current review proactively sought opportunities to grow professionally and believed that having sufficient knowledge of the UDL framework could support their practices and help them be more approachable to full inclusion (Takemae et al., 2018; Lowrey et al., 2019; Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021a). There is no doubt that providing more appropriate coursework or professional learning opportunities related to the UDL framework is essential to constructing pre-service teachers’ teaching philosophy and practices. However, only a few studies, such as MCGuire-Schwartz and Arndt (2007), compared how early childhood teacher candidates understood the UDL framework from university to early childhood settings. Reinhardt et al.’s (2023) study only analysed teacher educators’ thoughts when using the UDL design to construct a university curriculum to improve pre-service teachers’ knowledge about inclusive education. There is a lack of research to investigate pre-service teachers’ belief shifts before and after participating in the UDL training or coursework. This highlights a need for more research in this field.

Further, Coubergs et al. (2017) stressed that if teachers had high expectations for students’ learning and believed students’ intelligence was malleable based on the social model of disabilities, they tended to use several strategies to address students’ different learning needs. Indeed, pre-service teachers intending to learn the UDL framework and theory should have positive beliefs toward students’ learning; then, they adopt more meaningful practices and support their students. On the one hand, it shows that pre-service teachers should change their minds to feel favourable toward their students in inclusive classrooms and believe that every student can learn in different ways or through multiple dimensions. On the other hand, the findings highlight that the inclusive education teacher education courses provided for pre-service teachers should be available and appropriate to meet their learning needs, as some irrelevant courses might negatively affect their beliefs about inclusion. Also, more training about the UDL framework with practical examples should be provided in the teacher education programmes to ensure that pre-service teachers can positively view the framework and have the intention to use this framework during practice, just as one pre-service teacher in Takemae et al.’s (2018) study said, “The most helpful practice I have to say would be last semester when we did a math unit plan using UDL. We all wrote different ones, and we would give it to the instructor, and the instructor would help us revise it …” (p. 85). This statement suggests that external support, such as university instructors, is critical in supporting pre-service teachers in gaining knowledge and skills in the UDL framework.

Based on the current review, self-regulation and motivation are the third predictors of how pre-service teachers implement the UDL framework. Most pre-service teachers in the review felt that they had responsibilities to use different ways to teach and support students during their practices, and then, they had the motivation to use the UDL framework to support students’ diverse needs (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021b; Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021a). This is in line with previous literature that teachers with a sense of initiative or responsibility for their students preferred to use autonomy-supportive practices that aligned with the UDL framework, such as providing options for students’ choices, initiating students’ interests through creating and providing abundant learning resources, etc. (Soenens et al., 2012). Kayama and Haight’s (2012) study also demonstrated that teachers who recognised their responsibilities to acknowledge the strengths of students with disabilities were more motivated to use inclusive practices than others (cited in 2022). Although Griful-Freixenet et al. (2021a) mentioned that self-regulation and motivation were to a lesser extent than self-efficacy and growth mindset, it is essential to note that pre-service teachers as future teachers should start to foster their responsibilities in inclusive education and ensure that they feel that inclusion need to be promoted in the future to support not only for students with disabilities rather than all students and create a more inclusive social environment for all.

These three belief domains, self-efficacy, growth mindset, and self-regulation and motivation, predict pre-service teachers’ successful engagement with the complex, design-oriented demands of the UDL implementation. Designing for variability is a key finding that differentiates the UDL implementation. This highlights the need for teacher education programmes provided for pre-service teachers to not only impart knowledge but, more importantly, foster their positive beliefs towards inclusive education, and then, they have the motivation to implement the UDL framework in their future teaching practices.

Factors influencing the UDL practices

Pre-service teachers’ family background, knowledge, teaching experience, and technology are three main factors in the current review that influence the implementation of the UDL framework. Firstly, Barahona et al. (2023), Griful-Freixenet et al. (2021a), and Griful-Freixenet et al. (2021b) indicated that pre-service teachers’ family backgrounds, such as cultural and linguistic backgrounds, affected their motivation and commitment in using the UDL framework during teaching practices. In Griful-Freixenet et al.’s (2021b) study, pre-service teachers with parents speaking languages other than the official languages were likelier to implement diverse teaching approaches within the UDL framework. Indeed, it is unsurprising that pre-service teachers who live in multicultural or multilingual environments must have more personal experiences to be excluded from the so-called ‘mainstream’ society or face challenges in learning, so they may better understand how important it is to learn from diverse pathways. The findings are consistent with those of Faez (2012), who indicated that culturally and linguistically diverse teachers could better understand non-native language learners’ educational challenges. Hence, pre-service teachers from culturally or linguistically diverse backgrounds should be more motivated to use the UDL framework, as the UDL framework provides multiple means to support students in learning. Furthermore, Han and Singh (2007) and Santoro (2015) stressed that teachers from multilingual or culturally diverse backgrounds could access multilingual knowledge to inform their teaching practices, and they were able to use different perspectives to design the curriculum to suit some students’ needs and abilities. This suggests that pre-service teachers have responsibilities to design the curriculum in multiple ways, and some knowledge can be extended based on students’ prior knowledge and experiences. In addition, pre-service teachers should expand their horizons and inform their teaching practices when using the UDL framework.

Secondly, the current review showed that pre-service teachers felt that the curriculum accommodation and modification were supported by their understanding of the UDL principles from their coursework and field-based experiences (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021b; Takemae et al., 2018). For instance, one pre-service teacher pointed out that third-year bachelor students had significantly more knowledge about the UDL framework to independently design the programmes than the first or second years of bachelor’s degrees (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021b). According to teacher professional standards in Australia, China, and the United States, having sufficient knowledge and skills to support the learning and development of all students, including students with disabilities, has always been emphasised as the fundamental objective for teacher education programmes. Although there is a lack of literature to explore pre-service teachers’ knowledge regarding the UDL framework, pre-service teachers with more knowledge of inclusive education and the UDL framework must be more positive and active in applying the diverse and flexible teaching approach to meet students’ learning needs. Moreover, teaching experience is the other factor that directly influences pre-service teachers’ practices in using the UDL framework; as one pre-service teacher said, “As the number and duration of the field experience increases in teacher education programmes, it can be speculated that teaching experience will positively affect the implementation of UDL.” (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021b, p. 10). Henry et al. (2011), Hu et al. (2017), and Kosgei et al. (2013) emphasised that teachers with abundant teaching experience might be more willing to adopt new teaching pedagogy than those with less experience. Although pre-service teachers must have less teaching experience in the field, as they have few opportunities, such as internship or practicum, to have direct contact with students, it cannot ignore that teacher experience may impact their beliefs about teaching (Wang et al., 2017). Therefore, the findings suggest that the teacher education programme should provide more practical opportunities for pre-service teachers to implement evidence-based teaching approaches, such as the UDL framework. The instructors and supervisors must encourage pre-service teachers to implement what they have learned in the coursework into their practices. Some virtual simulation techniques can also be applied to teacher education programmes to engage pre-service teachers in dealing with “real” classroom situations through technology during coursework learning.

Thirdly, the use of technology and how to use it may also influence the UDL practices of pre-service teachers. Several pre-service teachers believed technology could support them in clearly illustrating course content based on the first UDL principle, multiple means of representation (Mackey et al., 2023). Mackey et al. (2023) found that pre-service teachers used assistive technology to engage students to present their understandings by drawing, as some students struggled with writing. Indeed, the technology could support pre-service teachers’ lesson planning and design by following the UDL model and promoting teacher-student and teacher-teacher collaboration (Scott et al., 2022). Even one pre-service teacher believed that the UDL framework helped her to save planning time, as she could integrate the IEP goals into course content instead of planning them separately (Scott et al., 2022). Nevertheless, one pre-service teacher described that technology might create inequality in access in remote or rural areas if students could not access computers or the internet (Barahona et al., 2023). Indeed, the use of technology in the UDL framework has always been a controversial topic. It is undeniable that integrating technology into UDL practices is beneficial to creating more flexible and supportive programmes for all students in the classroom. However, it is necessary to understand that the three principles of the UDL framework can be implemented in a paper-based model, such as using pictures and teaching aids to represent course contents, etc. (Han & Lei, 2024). This indicates that pre-service teachers should improve their skills in integrating the paper-based and technology-based approaches to design courses to ensure equal access to all students.

Challenges and barriers in implementing the UDL framework

Based on the selected studies, pre-service teachers felt that the lack of resources, the rigid curriculum, and classroom management were the three main challenges faced when implementing the UDL framework. One pre-service teacher in Barahona et al.’s (2023) study highlighted that the lack of sufficient and relevant resources influenced his lesson design, as he could not plan complex activities. This aligns with previous studies that state that a lack of available resources and using resources ineffectively have adverse effects on interventions in inclusive education (Hersh & Elley, 2019; Samadi & McConkey, 2018; Jury et al., 2023 2). Thus, just as Meijer and Watkins (2019) mentioned that the funding provision was an essential tool for the implementation of inclusive education, the allocation of budget in distinct kinds of resources, such as material resources, spatial resources, etc., should be reasonable to ensure that teachers can use relevant resources based on the UDL course design. Also, as training is the other resource that needs more funding, pre-service and in-service training should adapt to “real” classroom situations and support pre-service teachers in using the resources effectively and efficiently.

Classroom management is another challenge some pre-service teachers highlighted in the current review. One pre-service teacher stressed that understanding the UDL framework did not imply the ability to put theoretical knowledge into practice because the class environment was more complex than imagination (Barahona et al., 2023). The UDL framework encourages teachers to represent course content in multiple ways, to promote students’ engagement in multiple ways, and to ensure students’ demonstration of their understanding in multiple ways. Conceivably, more diverse teaching materials, assessment tools, and options should be included in curriculum design and implementation. This highlights a need for pre-service teachers to plan and consider broadly the classroom environment, students’ barriers and challenges, and some emergency circumstances, such as challenging behaviours.

The rigid and inflexible curriculum is one of the most critical challenges to limit pre-service teachers’ chances of implementing the UDL framework. A pre-service teacher stressed, “I wanted to implement UDL principles, but some activities did not work. Implementing multiple means of expression is impossible to implement with a rigid curriculum.” (Barahona et al., 2023, p. 6) This is consistent with previous studies, such as Adu-Boateng and Goodnough (2022), Lowrey et al. (2017), and Markou and Diaz-Noguera (2022), that many teachers, especially secondary school teachers, felt stressed and overwhelmed by using the UDL framework because of the inflexible curriculum and standardised testing, though most of them felt that the UDL framework was beneficial for students learning and development. In terms of the UDL framework, the main objective is to ensure that students can engage in lessons and learn in diverse ways, as students vary in abilities in learning, motivation, and engagement. As such, the UDL principles can suit all students, whatever their ages, abilities, and levels, just as Müller et al. (2023) indicated that all students could learn knowledge and achieve goals if teachers were flexible in instruction and curriculum design. This provides high-level requirements for teacher professionals in curriculum design and implementation to meet the diverse needs of students in inclusive classrooms. Also, ongoing coursework and professional development are required to guide pre-service and in-service teachers in integrating standardised national curricula into the UDL implementation (Han & Lei, 2024).

Conclusion

Recently, promoting high-quality inclusive education has become a central goal for governments worldwide to ensure that educational provision can meet all students’ interests and learning needs. The UDL framework is an innovative theoretical and practical framework to guide teachers in designing their curriculum and making accommodations and modifications to their teaching practices. Pre-service teachers, as future teachers, should have the ability to implement such a teaching approach to design multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagement for their students and create an inclusive environment for all. Also, teachers’ teaching philosophy originated from their knowledge and experiences in teacher education programmes (Bransford et al., 2005). Thus, it is necessary to investigate pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework. Then, it can provide several implications for creating more appropriate and high-quality teacher education programmes to promote the quality of inclusive education in the future. This scoping review adds to the recent literature on pre-service teachers’ beliefs and practices in inclusive education, especially exploring their beliefs toward the UDL framework. However, due to the limited literature in this field, the researchers suggest that more empirical studies regarding pre-service teachers’ beliefs and practices in implementing the UDL framework should be conducted in the future.

In summary, although some systematic reviews and meta-analyses have existed in the field to investigate the effectiveness of the UDL framework, and Han and Lei (2024) conducted a scoping review to conceptualise in-service teachers’ beliefs and practices in implementing the UDL framework, very few studies have conducted so far to examine pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework systematically. The pre-service stage, the most significant stage for teacher candidates, can develop their professional skills and knowledge and form harmony among teachers’ hearts, heads, and hands (Sharma, 2018). Therefore, this is the first scoping review to summarise and conceptualise pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework.

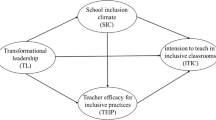

After reviewing the selected studies, the review concluded that most pre-service teachers held positive beliefs toward the UDL framework and were committed to implementing the UDL framework during the internships/practicum and future teaching practices. In addition, adaptation and inclusion, equity and access, and active and flexible were three significant beliefs that pre-service teachers held about the UDL framework, as most of them thought that the UDL framework could create a more inclusive environment and curriculum for all students, not only focusing on students with disabilities. This is essential to promote the equity and quality of education. Self-efficacy, self-regulation and motivation, and a growth mindset were the three most important predictors for pre-service teachers implementing the UDL framework. However, some factors, including pre-service teachers’ family background, knowledge, teaching experience, and technology, might influence their beliefs and practices in implementing the UDL framework. The lack of enough teaching resources, rigid curriculum, and classroom management were the other challenges pre-service teachers faced when using the UDL framework in curriculum design and teaching practices. The overall conclusion related to the relationships among pre-service teachers’ beliefs, predictors, factors, and challenges and barriers is shown in Fig. 2.

Limitations

Firstly, this study used a scoping review methodology to map the literature rather than appraise the quality of individual studies or synthesise evidence of effectiveness. Thus, the depth of analysis regarding methodological rigour within the included studies is limited. Secondly, the inclusion of studies was restricted between 2014 and 2024. This ensured the current theoretical shift in the UDL framework (Meyer et al., 2014), but potentially excluded earlier works exploring fundamental beliefs relevant to the UDL framework. Thirdly, although thematic analysis was appropriate for identifying patterns and involving interpretation, the relatively small number of included studies also limited the potential for deeper synthesis. Finally, the included studies primarily originated from Western contexts. Findings may not fully reflect pre-service teachers’ experiences, belief structures, or challenges in other regions with different educational systems, resources, or cultural norms. It suggests that more empirical studies on pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework should be conducted in the under-represented countries to support deep analysis across diverse contexts.

Implications for practices and future research

This scoping review provides practical implications for creating high-quality and appropriate teacher education programmes and promoting inclusive education. The implications for future research are also indicated at the end.

First, teacher education programmes in inclusive education should provide more relevant knowledge that meets pre-service teachers’ learning needs and practical opportunities to support their skills in effectively implementing the UDL framework during teaching practices. This is necessary for pre-service teachers to improve their self-efficacy and confidence in teaching in inclusive classrooms and make them feel efficacious in using the UDL framework to design inclusive courses and environments to meet the needs and interests of all students in order to achieve full inclusion. The university instructors also play critical roles in guiding teacher candidates’ practices in planning and teaching by using the UDL framework, so the university instructors should also be favourable toward the UDL framework and encourage pre-service teachers to implement it during teaching practices.

Secondly, the current review highlights the need for pre-service teachers to foster their responsibilities in teaching, including teaching students with disabilities or diverse learning needs. Thus, teacher education programmes should not only impart knowledge in inclusive education and the UDL framework but also foster teacher candidates with positive beliefs about inclusive education and hold high expectations for their students, regardless of gender, age, ability, and school level. More importantly, the teacher education programmes in inclusive education should connect pre-service teachers’ prior knowledge, model effective teaching practices, and expand teacher candidates’ horizons to inform pre-service teachers’ teaching practices in using the UDL framework.

Thirdly, although technology plays an essential role when implementing the UDL framework, using technology is not a requirement to implement the framework in practice. On the one hand, university instructors need to practice teacher candidates’ skills in using technology to design multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagement during teaching practices. On the other hand, pre-service teachers must understand that technology can support inclusive teaching practices. However, technology is not a prerequisite when implementing the UDL framework. Therefore, pre-service training should support teacher candidates in following the three UDL principles efficiently and encourage them to focus on the concept of teaching rather than relying on technology. Pre-service teachers should improve their skills in integrating paper-based and technology-based approaches to design courses to ensure equal student access.

Finally, the funding provision and allocation should be reasonable, such as providing sufficient teaching materials and equipment to ensure that teacher candidates and in-service teachers can actively engage in the course design and implementation using the UDL framework. Further, as training is the other resource that needs more funding, pre-service and in-service training should adapt to “real” classroom situations and support pre-service teachers in using the resources effectively and efficiently. The ongoing professional development is required to guide pre-service and in-service teachers in integrating standardised national curricula into the UDL implementation.

Regarding the implications of future research, first, more empirical studies need to be done to explore pre-service and in-service teachers’ beliefs towards the UDL framework in different contexts, as the current review showed that pre-service teachers who were from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds were more likely to use the UDL framework than others. Second, it is necessary to explore the changes in pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward the UDL framework before and after taking the coursework and internship/practicum, as this can provide more explicit evidence to support university instructors in designing curricula related to the UDL framework and inclusive education. Third, since much literature has investigated in-service teachers’ beliefs and practices and their engagement in professional development related to the UDL framework (Han & Lei, 2024), more research can be conducted in the future to compare pre-service and in-service teachers’ beliefs about the UDL framework in order to provide more practical understanding about how to design more appropriate pre-service and in-service training to meet their training needs. Fourth, since most studies related to pre-service teachers’ beliefs in implementing the UDL framework were conducted in Western countries, especially in the United States, more empirical studies about this topic should be conducted in different countries and contexts, as cultural factors might significantly affect how pre-service teachers transfer the UDL principles into their teaching during the internships/practicum or future practices.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Adu-Boateng S, Goodnough K (2022) Examining a science teacher’s instructional practices in the adoption of inclusive pedagogy: A qualitative case study. J Sci Teach Educ 33(3):303–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2021.1915605

Ahsan T, Sharma U (2018) Pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards Inclusion of students with high support needs in regular classrooms in Bangladesh. Br J Spec Educ 45(1):81–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12211

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Assor A, Kaplan H, Kanat-Maymon Y, Roth G (2005) Directly controlling teacher behaviours as predictors of poor motivation and engagement in girls and boys: The role of anger and anxiety. Learn Instr 15(5):397–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.008

Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol Rev 84(2):191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura A (1982) Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol 37(2):122–147

Barahona M, David V, Gallegos F, Reyes-Rojas J, Ibaaceta-Quijanes X, Darwin S (2023) Analysing preservice teachers’ enactment of the UDL framework to support diverse students in a remote teaching context. System 114:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2023.103027

Boyle C, Barrell C, Allen K, She L (2023) Primary and secondary pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Heliyon 9:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22328

Bransford J, Darling-Hammond L, LePage P (2005) Introduction. In L. Darling-Hammond, & J Bransford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 1–39). Jossey-Bass

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Centre for Applied Special Technology (CAST) (2024) Universal design for learning guidelines version 3.0 [graphic organiser]. https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Chen RJ (2010) Investigating models for pre-service teachers’ use of technology to support student-centred learning. Comput Educ 55(1):32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.11.015

Coubergs C, Struyven K, Vanthournout G, Engels N (2017) Measuring teachers’ perceptions about differentiated instruction: The DI-Quest instrument and model. Stud Educ Eval 53:41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.02.004

Faez F (2012) Diverse teachers for diverse students: Internationally educated and Canadian-born teachers’ preparedness to teach English language learners. Can J Educ 35(3):64–84

Fives H, Buehl MM (2012) Spring cleaning for the ‘messy’ construct of teachers’ beliefs: What are they? Which have been examined? What can they tell us?. In KR Harris, S Graham, & T Urdan (Eds.), APA Educational Psychology Handbook: Vol. 2. Individual Differences and Cultural and Contextual Factors (p. 471–499). American Psychological Association

Gargiulo RM, Metcalf D (2023) Teaching in today’s inclusive classrooms: A universal design for learning approach (4th ed.). Cengage Learning, Inc

Griful-Freixenet J, Struyven K, Vantieghem W (2021a) Toward more inclusive education: An empirical test of the universal design for learning conceptual model among preservice teachers. J Teach Educ 72(3):381–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487120965525

Griful-Freixenet J, Struyven K, Vantieghem W (2021b) Exploring pre-service teachers’ beliefs and practices about two inclusive frameworks: Universal design for learning and differentiated instruction. Teach Teach Educ 107:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103503

Han C, Cumming TM (2022) Teachers’ beliefs about the provision of education for students with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Development Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-022-00350-6

Han C, Lei J (2024) Teachers’ and students’ beliefs towards universal design for learning framework: A scoping review. SAGE Open 14(3):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241272032

Han J, Singh M (2007) Getting world English speaking student teachers to the top of the class: Making hope for ethnocultural diversity in teacher education robust. Asia-Pac J Teach Educ 35(3):291–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660701447239

Hehir T, Grindal T, Freeman B, Lamoreau R, Borquaye Y, Burke S (2016) A summary of the evidence on inclusive education. ABT Associates. http://alana.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/A_Summary_of_the_evidence_on_inclusive_education.pdf

Henry GT, Bastian KC, Fortner K (2011) Stayers and leavers: Early-career teacher effectiveness and attrition. Educ Researcher 40(6):271–280. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X11419042

Hergott J (2020). Effects of special education and feeling of inclusion. Master’s Thesis. Northwestern College. Retrieved from https://nwcommons.nwciowa.edu/education_masters/204/

Hersh M, Elley S (2019) Barriers and enablers of inclusion for young autistic learners: Lessons from the Polish experiences of teachers and related professionals. Adv Autism 5(2):117–130. https://doi.org/10.1108/AIA-06-2018-0021

Hu BY, Wu HP, Su XY, Roberts SK (2017) An examination of Chinese preservice and inservice early childhood teaches’ perspectives on the importance and feasibility of the implementation of key characteristics of quality inclusion. Int J Incl Educ 21(2):187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1193563

Jordan A (2018) The supporting effective teaching project: 1. Factors influencing student success in inclusive elementary classrooms. Exception Educ Int 28(3):10–27. https://doi.org/10.5206/eei.v28i3.7769

Jury M, Laurence A, Cebe S, Desombre C (2023) Teachers’ concerns about inclusive education and the links with teachers’ attitudes. Front Educ 7:1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.1065919

Kayama M, Haight W (2012) Cultural sensitivity in the delivery of disability services to children: A case study of Japanese education and socialisation. Child Youth Serv Rev 34(1):266–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.10.023

Klassen RM, Tze VMC (2014) Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev 12:59–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001

Kosgei A, Mise JK, Odera O, Ayugi ME (2013) Influence of teacher characteristics on students’ academic achievement among secondary schools. J Educ Pract 4(3):76–82

Lee A, Griffin CC (2021) Exploring online learning modules for teaching universal design for learning (UDL): Preservice teachers’ lesson plan development and implementation. J Educ Teach 47(3):411–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2021.1884494

Leroy N, Bressoux P, Sarrazin P, Trouilloud D (2007) Impact of teachers’ implicit theories and perceived pressures on the establishment of an autonomy supportive climate. Eur J Psychol Educ 22(4):529–545

Lowrey KA, Classen A, Sylvest A (2019) Exploring ways to support preservice teachers’ use of UDL in planning and instruction. J Educ Res Pract 9(1):261–281. https://doi.org/10.5590/JERAP.2019.09.1.19

Lowrey KA, Hollingshead A, Howery K (2017) A closer look: Examining teachers’ language around UDL, inclusive classrooms, and intellectual disability. Intellect Devl Disabil 55(1):15–24. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-55.1.15

Mackey M, Drew SV, Nicoll-Senft J, Jacobson L (2023) Advancing a theory of change in a collaborative teacher education program innovation through universal design for learning. Soc Sci Hum Open 7:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100468

Markou P, Diaz-Noguera MD (2022) Investigating the implementation of universal design for learning in Greek secondary and second chance schools through teachers’ reflections Dayle learning. Eur J Educ Res 11(3):1851–1863. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.11.3.1851

MCGuire-Schwartz ME, Arndt JS (2007) Transforming universal design for learning in early childhood teacher education from college classroom to early childhood classroom. J Early Child Teach Educ 28(2):127–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901020701366707

Meijer CJ, Watkins A (2019) Financing special needs and inclusive education–from Salamanca to the present. Int J Incl Educ 23(7-8):705–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1623330

Meyer A, Rose DH, Gordon D (2014) Universal design for learning: Theory and Practice. CAST Professional Publishing

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: The PRISMA statement. Br Med J Publ Group (BMJ) 6(7):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535. & The PRISMA Group

Mojaveze A, Tamiz MP (2012) The impact of teacher self-efficacy on the students’ motivation and achievement. Theory Pract Lang Stud 2(3):483-491. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.2.3.483-491

Müller C, Mildenberger T, Steingruber D (2023) Learning effectiveness of a flexible learning study programme in a blended learning design: why are some courses more effective than others? Int J Educ Technol High Educ 20(10):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00379-x

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 18(143):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Pajares MF (1992) Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Rev Educ Res 62(3):307–332

Reeve J (2009) Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they can become more autonomy supportive. Educ Psychol 44(3):159–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520903028990

Reinhardt KS, Robertson PM, Johnson RD (2023) Connecting inquiry and universal design for learning (UDL) to teacher candidates’ emerging practice: Development of a signature pedagogy. Educ Action Res 31(3):437–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2021.1978303

Rose DH, Meyer M (2002) Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

Rusconi L, Squillaci M (2023) Effects of a universal design for learning (UDL) training course on the development teachers’ competences: A systematic review. Educ Sci 13(5):1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050466

Sharma U (2011) Teaching in inclusive classrooms: Changing heart, head, and hands. Bangladesh Educ J 10(2):7–18

Sharma U, Sokal L (2016) Can teachers’ self-reported efficacy, concerns, and attitudes toward inclusion scores predict their actual inclusive classroom practices? Australas J Spec Educ 40(1):21–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2015.14

Samadi SA, McConkey R (2018) Perspectives on inclusive education of preschool children with autism spectrum disorders and other developmental disabilities in Iran. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(10):1–8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102307

Santoro N (2015) The drive to diversify the teaching profession: Narrow assumptions, hidden complexities. Race, Ethnicity Educ 18(6):858–876. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2012.759934

Scott L, Bruno L, Gokita T, Thoma CA (2022) Teacher candidates’ abilities to develop universal design for learning and universal design for transition lesson plans. Int J Incl Educ 26(4):333–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1651910

Sharma U (2018) Preparing to teach in inclusive classrooms. In GW Noblit (Eds.), Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education (p. 1–22). Oxford University Press. Cited in 6

Sharma U, Loreman T, Forlin C (2012) Measuring teacher efficacy to implement inclusive practices. J Res Spec Educ Needs 12(1):12–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01200.x

Soenens B, Sierens E, Vansteenkiste M, Dochy F, Goossens L (2012) Psychologically controlling teaching: Examining outcomes, antecedents, and mediators. J Educ Psychol 104(1):108–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025742

Soodak LC, Podell DM, Lehman LR (1998) Teacher, student, and school attributes as predictors of teachers’ responses to inclusion. J Spec Educ 31(4):480–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/002246699803100405

Tannehill D, MacPhail A (2014) What examining teaching metaphors tells us about pre-service teachers’ developing beliefs about teaching and learning. Phys Educ Sport Psychol 19(2):149–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2012.732056

Takemae N, Dobbins N, Kurtts S (2018) Preparation and experiences for implementation: Teacher candidates’ perceptions and understanding of universal design for learning. Issues Teach Educ 27(1):73–93

Van Mieghem A, Verschueren K, Petry K, Struyf E (2020) An analysis of research on inclusive education: a systematic search and meta review. Int J Incl Educ 24(6):675–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1482012. cited in

Wang A, Chai CS, Hairon S (2017) Exploring the impact of teacher experience on questioning techniques in a knowledge building classroom. J Comput Educ 4(1):27–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-016-0057-2

Weber KE, Greiner F (2019) Development of pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs and attitudes towards inclusive education through first teaching experiences. J Res Spec Educ Needs 19(s1):73–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12479

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this article was supported by the First Batch of Postdocs Overseas Talent Introduction Programme (The Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China) and 2024 Teaching and Research Project, Central China Normal University, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.H. conducted data collection and analysis and wrote the main manuscript text. J.L. provided suggestions and comments for manuscript writing and revisions. C.H. and J.L. both reviewed the manuscript and prepared for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This is a scoping review article, so no human participants were included. Ethics approval was not applicable to this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, C., Lei, J. A scoping review of pre-service teachers’ beliefs about implementing the universal design for learning framework. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 969 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05336-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05336-3