Abstract

This article explores participants’ agreement to defer treatment decisions during doctor–patient negotiations of surgical treatment recommendations in China. As a recurrent outcome of medical consultations in Chinese clinical contexts, deferring treatment decisions is often used by both doctors and patients as a strategy to close the consultation when the two parties are at an impasse due to conflicting treatment preferences. It is not uncommon for clear decisions about surgical treatments to remain unresolved within the limited time of a consultation, particularly when doctors view surgery as the ultimate or even the only effective treatment, while patients consistently resist it. These treatment negotiations often reach a deadlock, with neither party willing to concede. When no agreement is reached, the consultation cannot be closed. In such cases, participants may propose deferring the treatment decision. This proposal can be initiated by either patients, through inquiries or statements, or by doctors, through inquiries or directives. Once an agreement to defer the decision is reached, the consultation can proceed toward closure. This study aims to introduce an alternative outcome to the typical “here-and-now” decisions (acceptance or rejection): the agreement to defer treatment decisions. We argue that this outcome emerges from the interplay between doctors’ and patients’ rights during the negotiation of surgical treatment recommendations. It reflects a balanced, yet delicate, relationship between doctors and patients. Using conversation analysis (CA) methodology and data drawn from authentic clinical consultations, we analyze in detail the specific practices that lead to this outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In China, during medical consultations where surgical treatments are recommended, patients are given sufficient rights and authority to decide whether or not to accept surgery. Unlike non-surgical treatment recommendations, where patient acceptance is necessary and must be secured before proceeding (Koenig 2011; Stivers 2005a, 2005b, 2006; Stivers and Timmermans 2020), the withholding of a clear commitment (e.g., acceptance/rejection) to the recommended surgical treatment is tolerated and understood in Chinese clinical contexts. This often leads to alternative outcomes beyond simple acceptance or rejection. An illustrative excerpt from a Chinese doctor–patient interaction, which includes such an outcome, is presented below.

Instead of offering a straightforward acceptance or rejection of the doctor’s surgical treatment recommendation, the relative in the excerpt above asks about the possibility of postponing the surgery (line 89). After the doctor approves the inquiry, the consultation proceeds toward the closing phase (a detailed analysis will follow). This case exemplifies a common outcome of medical consultations in China, where participants agree to defer treatment decisions, leading to the closure of the consultation. This outcome is the focus of the current study.

Background

Participants’ agreement to defer treatment decisions stems from specific attitudes toward surgery among Chinese patients, which can be further attributed to the characteristics of the medical system in China. In the following section, key aspects of the Chinese medical system and patients’ attitudes toward surgical treatment recommendations will be briefly explained to contextualize this outcome within Chinese clinical practices.

The medical system and patients’ tendency to directly go to high-level hospitals in China

China has developed a three-tiered hospital system: primary healthcare institutions at the bottom, secondary hospitals in the middle, and tertiary hospitals at the top. As of 2021, there were a total of 37,000 public hospitals, with 80% of medical resources and patients concentrated in large hospitals (Sun et al. 2017). In contrast, the primary healthcare system in China remains underdeveloped and fragmented (Li et al. 2017; Zou et al. 2015). According to statistics from 2020, more than 75% of primary healthcare providers did not hold a bachelor’s degree, 13.7% held a bachelor’s degree, less than 1% had a master’s degree, and fewer than 0.1% held a PhD or MD (Wu et al. 2022). This indicates that primary healthcare doctors may lack adequate or appropriate training.

Furthermore, primary healthcare institutions, including community health centers in urban areas and township health centers in rural regions, struggle to attract medical professionals with higher educational qualifications (Wu et al. 2022; Zhu et al. 2016). Regarding family physicians, the family doctor model has not been fully implemented and primarily targets elderly individuals with chronic diseases (Sun et al. 2017).

Moreover, an effective referral system between the three tiers of healthcare institutions is lacking in China. A national survey conducted in 2017 revealed that, among the 95 community health centers and 140 township health centers surveyed, only 38 (40%) community health centers and 30 (21%) township health centers had systems in place to link with secondary or tertiary hospitals for patient referrals (Li et al. 2017). In contrast to most Western general practitioners or family physicians, who are competent in providing generalist care, diagnosing, recommending treatments, and referring patients to specialized hospitals, primary healthcare providers and institutions in China are not sufficiently equipped to act as gatekeepers for surgery, hospitalization, and other specialized care.

Since the 1980s, China’s medical service system has incorporated market mechanisms, allowing people to seek care at any level of medical institution. In most cases, basic medical insurance covers a significant portion of the expenses. Many health insurance policies in China even offer more generous reimbursements for inpatient care, which motivates patients to seek treatment at large hospitals, even for minor issues (Li et al. 2017). In China, primary care can be provided by general practitioners or other physicians (Zou et al. 2015), and there is no strict regulation preventing patients from directly accessing secondary or tertiary hospitals. As a result, many Chinese people have developed a habit of bypassing primary care and going directly to higher-level hospitals for their health concerns. In contrast to many Western countries, where larger hospitals often receive lower patient satisfaction ratings, Chinese large hospitals typically score higher in patient satisfaction. This is because they are generally better equipped with technical, financial, and human resources (Hu et al. 2020).

It has been found that approximately 85% of health services in China are provided by public hospitals (Liang et al. 2020), which has led to burnout among hospital doctors and overcrowded conditions (Hu et al. 2020; Lo et al. 2018; Zhu and Song 2022). In response, Chinese hospitals are striving to maximize service efficiency. With a medical ID number, doctors can easily access a patient’s medical record through a computer. Additionally, patients can use their cellphones to book appointments (selecting the doctor and consultation time), register, order medical tests based on professional recommendations, view test results, access prescriptions, and pay for medications. Healthcare services in public hospitals are becoming increasingly convenient, with efficiency continuously improving.

Due to the inadequacies of China’s primary healthcare system and the continuous improvement in the quality and efficiency of medical services at public hospitals, an increasing number of patients bypass primary care institutions and directly seek treatment at higher-level hospitals. Statistics show that from January to May 2023, public hospitals recorded 1.4 billion individual diagnoses and treatments, while private hospitals recorded 280 million, together accounting for approximately 60.5% of all casesFootnote 1.

Patients’ views on surgical treatment recommendations in China

Due to the unique characteristics of China’s medical system, surgical treatment recommendations for Chinese patients are often perceived as unexpected, financially burdensome, and disruptive to daily life.

As previously reported, people in China have the freedom to visit larger hospitals and often develop the habit of seeking care at higher-level facilities when they feel unwell. This includes individuals from remote areas, who may travel long distances for better care or simply to seek professional opinions at secondary or tertiary hospitals. As a result, when patients are advised to undergo surgery, it is often during their first consultation with medical staff. This makes surgery not only an unexpected option but also one they may have never considered before.

Financial burden is another key factor influencing Chinese patients’ decisions. Although basic health insurance provides security by reimbursing a significant portion of medical expenses—typically covering 50 to 80%—patients are still required to pay the remaining costs out of pocket. The total cost of surgery includes not only surgical fees but also additional living expenses, such as transportation and accommodation, which can be a substantial burden, especially for patients from rural areas (Lee et al. 2022).

Moreover, surgery may cause significant disruption to patients’ daily lives, with unpredictable and long-lasting consequences (Landmark et al. 2015). The potential interruption to their orderly and controlled routines contributes to patients’ reluctance to accept surgical treatment recommendations in China.

In summary, the unexpected nature of surgical treatment recommendations, the associated costs, and the sudden disruptions to daily life all contribute to patients’ resistance to surgery, making the decision to accept or reject these recommendations more challenging. This context further illuminates the broader environment in which deferred treatment decisions are made.

Having discussed patients’ general perspectives on surgery in China, we now turn to their real-time responses to surgical treatment recommendations during clinical consultations. As mentioned earlier, it is often the first time Chinese patients speak with medical professionals when surgery is recommended. In a single, time-limited consultation, patients must navigate the process of establishing the reason for their visit, undergoing any necessary tests (Toerien et al. 2020), receiving a diagnosis, and considering treatment options.

A substantial number of doctors (44%, according to Niu’s 2014 survey) may use the time-saving method of plain assertion when delivering diagnoses (Peräkylä 1998), resulting in a “back-to-back” or even “compressed” delivery of both the diagnosis and the surgical treatment recommendation. This means that patients are expected to comprehend the seriousness of their diagnosis and the need for surgery almost simultaneously, which can be overwhelming. The challenge of processing so much information in a short period makes it difficult for patients to make an immediate decision about surgery. This compressed sequence of medical activities—especially diagnosis and treatment—creates a local context in which patients often struggle to decide on the spot, leading to a mutual agreement to defer the ‘decision point’ (Toerien 2018, p. 1355). Consequently, no immediate agreement on the next steps is reached during the consultation (Toerien 2021).

Together, the general perspective on surgery among Chinese patients and the compressed delivery of diagnoses and treatment recommendations create both local and broader contexts for deferred treatment decisions. This study focuses on how these deferred decisions unfold in actual clinical consultations in China.

Definition, data, and method

The data used in this paper were drawn from approximately 936 min of audio recordings of clinical consultations at two Chinese tertiary hospitals. These recordings primarily consist of authentic doctor–patient interactions in the fields of orthopedics and proctology. Participants were informed that the data would be used for research purposes and that their transcripts would be anonymized. Additionally, the voices of all participants were specially processed to protect their identities. After being informed about the identity protection measures, participants provided their informed consent. The study procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Basic Medical Sciences at our university.

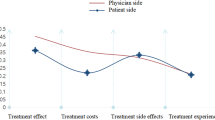

We identified 80 consultations in which doctors recommended surgery. In these consultations, surgery was presented as the last best resort—that is, the most drastic or even the only effective treatment (Clark and Hudak 2011; Hudak et al. 2011, 2013). Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of surgical treatment proposals and the outcomes of treatment decision-making in the dataset.

As shown in Fig. 1, surgery can be presented as an elective option within the practice of option-listing (Chappell et al. 2018; Reuber et al. 2015; Toerien et al. 2013) or as the only effective treatment in surgical treatment recommendations.

In the consultations (30%, n = 24) where surgery is presented by doctors as an elective option, patients are offered other non-surgical treatments as alternatives. However, surgery is framed as the ultimate solution to patients’ problems and is given top priority among the list of potential treatment options. Even when patients opt for a non-surgical treatment, doctors propose retaining surgery as a possible future remedy. Unlike treatment recommendations, where the patient’s acceptance is the next relevant step, the provision of a list of treatment options makes the patient’s selection the relevant next step (Toerien et al. 2013). As shown in Fig. 1, among the 24 cases, only 4 (17%) patients chose surgery, despite doctors’ emphasis on its privileged status as the last best resort. This suggests that surgery is not the preferred option for most patients in actual clinical practice in China.

In 70% (n = 56) of the consultations, doctors present surgery as the only effective option. As noted by Hudak et al. (2013, p. 544), “constituting surgery as a fix or answer to a patient’s problem precludes the possibility that patients might choose something ‘less’“. According to this perspective, surgery is the only means to prevent further deterioration, and it should be performed as soon as possible. Of these patients, 21.4% (n = 12) accept the surgical treatment recommendation, 1.8% (n = 1) refuse it, and in the remaining 76.8% (n = 43), patients and doctors agree to defer treatment decisions. The excerpts used in this study were selected from consultations where the treatment decisions were deferred.

As shown in Fig. 1, there is a strong possibility that no clear acceptance or rejection of surgery is provided within the time constraints of a single consultation. We identified 43 such cases in our data. In these inconclusive consultations, doctors typically do not insist on obtaining a clear commitment from patients who resist surgery. Instead, both doctors and patients agree to close the consultation with the treatment decision marked as “deferred”. It is important to note that, in some cases, doctors may prescribe medications for temporary pain relief, but they emphasize that these are only short-term solutions. Only surgery, they argue, offers a permanent or more drastic effect. Thus, the treatment decision—more specifically, the final decision regarding surgery—is considered deferred. By “deferred”, we mean that the final treatment decision is regarded as a pending or unresolved issue to be addressed in the future. In terms of immediate outcome, deferred treatment decisions refer to situations where no agreement on the next steps is reached during the current consultation (Toerien 2021).

The current study suggests that such an outcome serves as a “way out” for both doctors and patients. In other words, it provides a strategy for concluding the visit when negotiations regarding the surgical treatment reach an impasse, with both parties holding conflicting treatment preferences. This outcome reflects the interplay between doctors’ and patients’ rights in the actual negotiations of surgical treatment recommendations in China.

The present study aims to illustrate how doctors and patients in China frame the treatment decision as deferred during their negotiation of surgical treatment, as well as to explore the interplay of both parties’ rights in this process. Using conversation analysis (CA) methodology, the study seeks to enhance the understanding of doctor–patient negotiations by investigating an outcome that has not been extensively analyzed before: the deferred treatment decision. This decision differs from the common “here-and-now” decision (acceptance/rejection) but frequently occurs in Chinese clinical practices. We observe that the deferral of making a clear treatment decision is proposed by either patients or doctors, with the relative proportions shown in Fig. 2. The following analysis will examine each type of practice in detail, based on excerpts taken from authentic doctor–patient consultations in China. Data were transcribed using the transcription notations proposed by Gail Jefferson (2004).

The deferral of treatment decisions proposed by patients

As shown in Fig. 2, in the majority of cases (n = 32, 74%), the deferral of making a clear treatment decision is proposed by patients. Patients who find it difficult to accept surgery may suggest concluding the consultation with the treatment decision marked as deferred. We observe that patients often propose deferring a clear decision using two types of formats: inquiries and statements.

Through inquiries

In the negotiation of surgical treatment recommendations, patients may inquire about the possibility of deferring a clear decision if they are unable to reach a conclusion based on their understanding of the biomedical reasoning behind the doctor’s treatment recommendations. After receiving an affirmative response from the doctor, the consultation is brought to a close, and the treatment decision is marked as deferred. Excerpt (1) provides an example.

In this excerpt, the doctor (male) diagnoses the patient (female) with an anal fissure and immediately asserts that surgery is necessary, claiming that the patient’s condition cannot be fully cured without it. After the treatment negotiation, the patient remains undecided about accepting the surgical recommendation and proposes deferring the treatment decision through an inquiry. Once the doctor agrees to this proposal, the consultation concludes. A detailed analysis of the data is presented below.

After conducting the physical examination, the doctor recommends surgery (line 2). Immediately following this proposal, the patient asks a repeated question (line 3), which can be interpreted as a request for the doctor’s confirmation of the recommendation. By posing this request for confirmation at the point where acceptance is expected, the patient demonstrates her reluctance to accept the surgical recommendation. However, by requesting confirmation rather than providing a straightforward answer, the patient avoids outright disagreement while still expressing resistance (Stivers 2005a, 2005b, 2006). Later, one of the patient’s relatives also repeatedly inquires about the necessity of surgery (lines 12, 14), to which the doctor provides affirmative responses. Additionally, the patient suggests alternative non-surgical treatments (line 45), further expressing resistance. By inquiring about the feasibility of using medications, the patient signals her preference for non-surgical treatments. In response, the doctor only confirms the temporary effect of medications (lines 46–48), reinforcing surgery as the ultimate solution.

Beyond resistance, both the patient and her relatives demonstrate their orientation toward surgery by asking about various aspects of the procedure. These include questions about the surgical process (line 16), the duration of the surgery (line 39), the risk of recurrence post-surgery (line 66), information about the surgeon (line 79), and the patient’s recovery (line 80). These inquiries reflect concerns about the surgery, further contributing to their resistance to the treatment recommendation. However, these questions also signal their acknowledgment of surgery as a viable option, despite their initial resistance.

Faced with the patient’s and relatives’ inquiries and resistance, the doctor provides detailed responses and explanations grounded in his biomedical expertise and experience (lines 17, 40, 46–50, 55–57, 67, 81–86). In his responses, he emphasizes that surgery is the only viable option to permanently resolve the patient’s issue, stressing that her current condition will recur if surgery is not performed (lines 46–48, 55–57).

As the doctor presents his biomedical reasoning to the patient and her relatives, one of the relatives becomes convinced and attempts to persuade the patient to accept surgery (line 78). However, when all the information regarding the surgery has been clarified and the patient’s response to the treatment recommendation is due, she does not provide a direct answer. Instead, she inquires about the possibility of postponing the surgery until the school vacation (line 89). Notably, after this inquiry, the patient neither discusses nor sets a specific surgery date with the doctor, nor does she schedule the next consultation. As indicated in line 93, the patient explains that she needs more time to discuss the treatment with her family. At this point, the patient has not made a definitive decision regarding the surgery. In this context, the inquiry serves as a proposal to defer the treatment decision and postpone surgery, without providing an immediate response to the surgical recommendation. With the surgery postponed, the treatment decision is also deferred, and the doctor agrees to the patient’s proposal (line 90).

Although the doctor emphasizes the superiority of surgery over other treatment options, he acknowledges that the patient has the final right to decide whether to accept the proposed treatment. Later, the doctor clarifies that the recommendation and treatment decision ultimately depend on the patient’s personal desires and needs (line 101).

In this excerpt, the idea of deferring the treatment decision is proposed by the patient through an inquiry. After the doctor gives an affirmative response to the inquiry (line 90) and assures the

patient that her condition will remain stable temporarily without surgery (line 103), the consultation is closed.

Through statements

In addition to inquiries, patients sometimes make statements indicating that they need more time to decide on the treatment. Once doctors agree to this request, the consultation moves toward closure, with the treatment decision marked as deferred. This is illustrated in the following excerpt.

In Excerpt (2), the doctor (male) recommends surgery for the patient (male). However, the patient and his relatives (the patient’s parents) are concerned that surgery may impact his studies, which prevents them from accepting the recommendation immediately. The doctor acknowledges that the patient’s studies may be affected shortly after the surgery, but asserts that it is the only effective treatment; without it, the patient’s condition will worsen. Despite this, the patient and his relatives still struggle to make an immediate decision. Later, Relative B expresses the need to consider the recommendation before making a final decision. The doctor accepts this statement, resulting in the treatment recommendation being deferred. Below is a detailed analysis.

After conducting a physical examination, the doctor diagnoses the patient with an abscess (line 1) and recommends minor surgery (line 13), emphasizing that it is the only effective treatment (line 14). The doctor’s surgical recommendation is met with resistance, indicated by a two-second silence (line 15). Relative A then seeks confirmation of the recommendation by repeating “minor surgery” with rising intonation (line 16), to which the doctor affirms (line 17). However, this confirmation also encounters resistance from both the patient and the relative, who withhold any response (line 18). Later, Relative A more explicitly expresses resistance by asking about the possibility of avoiding surgery (line 27). The doctor rejects the option of non-surgical treatments, explaining that the patient’s condition will worsen without surgery (lines 28–29). However, his explanation is met with further resistance.

Faced with resistance, the doctor justifies his treatment recommendation by elaborating on the diagnosis (lines 31–32). After a long pause of 10 s, the relatives begin asking questions, primarily concerning the consequences of surgery and its impact on the patient’s studies—specifically, whether the patient will be able to sit and study shortly after the procedure (lines 34, 42, 49). These questions reflect the relatives’ concerns about the potential implications of surgery. The doctor acknowledges the possible short-term effects of surgery on the patient (lines 35, 43, 48, 50) but explains that the duration of recovery depends on how soon the surgery is performed: the sooner it is done, the shorter the recovery time (line 36).

Despite receiving specific answers regarding the surgery, the relatives are still unable to decide whether to proceed. After a two-second pause, Relative B makes a declarative statement expressing the need to consider the recommendation further before making a final decision (line 54). The doctor acknowledges this statement, framing the treatment decision as deferred.

As the agreement on deferring the decision brings the current consultation to a close, Relative A reopens the conversation by reiterating the question about how surgery will affect the patient’s studies (line 56). Subsequently, the patient and relatives ask additional questions about the specifics of the surgery. The patient and Relative B inquire about the precise duration of recovery (lines 58, 59), while Relative A asks about the timing (line 65), procedures (line 67), and cost (line 76) of the surgery. The doctor responds to all these questions, emphasizing that the patient should undergo surgery as soon as possible (lines 74–75). However, still unable to make a final decision, Relative A concludes the conversation (line 85), leaving the treatment decision deferred.

In the above two excerpts, whether through an inquiry or a statement, the idea of deferring the treatment decision is initiated by the patient through a “first” action, which makes the doctor’s particular response relevant (Raymond 2003). In the following excerpt, however, the deferral of making a clear decision about surgery is framed by the patient as a response to the doctor’s inquiry.

In Excerpt (3), the doctor (male) diagnoses the patient (male) with a torn posterior root of the medial meniscus after examining his leg. Following another round of physical examination, the doctor concludes that surgery is necessary. He repeatedly asks for the patient’s agreement to schedule the surgery and reserve a hospital bed. However, both the patient and his relative are unable to make a decision. In response to the doctor’s inquiry about making the reservation, the patient states that he needs to discuss it with his family first, thus deferring the treatment decision. A detailed analysis is presented below.

After reviewing the results of the scan and taking the patient’s history, the doctor recommends minimally invasive surgery (line 7). The relative requests confirmation of the recommendation by repeating it (line 8). The doctor confirms it and elaborates on the evidence supporting his conclusion (lines 9–10). The doctor then explains that minimally invasive surgery is the first step, and that more surgeries might be needed in the future, depending on the patient’s physical condition (line 14). Despite the doctor’s clear explanation, the patient refuses to provide an outright response to the surgical treatment recommendation, leaving a full second of silence (line 17). This withholding of any response indicates the patient’s resistance to surgery. In turn, the doctor responds to this resistance and seeks a response through various strategies, including a straightforward inquiry (line 18) and a forceful directive (line 24). However, these efforts encounter further resistance from both the patient and the relative. In response to the doctor’s attempts to elicit a response, both the patient and the relative initiate additional questions or withhold any response, thus avoiding giving a clear and definite answer to the surgical proposal when one is due.

Despite their avoidance, the only questions the patient and relative ask are related to the surgery (lines 19, 25). Specifically, the relative inquires about the next steps if the patient agrees to undergo surgery (line 25), which indicates a recognition of the proposed surgical treatment as a viable option that could be considered.

In this excerpt, the doctor somewhat pressures the patient for an overt response, as evidenced by his direct inquiry (line 18) and forceful directive (line 24). However, he also emphasizes that the patient’s preferences should guide the decision-making process. Whether through the inquiry, “Do you want to have surgery or not?” (line 18), or the directive, “Make your decision about surgery as soon as possible” (line 24), the doctor’s aim is to elicit a clear commitment and decision from the patient regarding the surgical treatment. This suggests that the doctor frames the recommendation as “contingent on the patient’s preferences or needs” (Toerien 2021, p. 8), leaving the ultimate decision largely in the hands of the patient.

Furthermore, the inquiry about whether to reserve a hospital bed separates the logistical aspects of planning the surgery from the final decision to undergo it, thus giving the patient some space between receiving the recommendation for surgery and making the ultimate decision to accept or reject it. Later, the doctor explains that the patient needs to reserve a hospital bed in advance and may have to wait in line if he opts for surgery (line 28). However, he reassures the patient that the bed reservation can be canceled if he ultimately decides against surgery (line 52).

Although the doctor accepts the possibility that the patient may change his mind while waiting for the hospital bed, he does not compromise his professional expertise or offer any concessions. On the contrary, he asserts that the patient definitely needs surgery (line 36), emphasizing that surgery is the only effective option available to the patient.

When the time comes for the patient to accept or reject the doctor’s proposal after all queries have been answered and explained, he responds to the doctor’s inquiry with a declarative statement: “I need to talk to my family first” (line 32). This indicates that he requires additional time before making a final decision about the surgery. Through this statement, the patient introduces the idea of deferring the treatment decision. The relative aligns with this position (line 33). Although the doctor does not explicitly acknowledge this response, he later attempts to persuade them to accept the bed reservation (line 46). However, the patient and relative are informed that they have the right to cancel the reservation (line 52). In this sense, the treatment decision remains deferred, with no clear acceptance or rejection reached within the current consultation. After agreeing on the bed reservation, the medical encounter concludes.

Summary

In the excerpts presented above, doctors and patients maintain a balanced yet delicate relationship during their negotiations regarding surgical treatments. On one hand, doctors demonstrate an orientation toward the patients’ concerns and acknowledge their ultimate right to accept or reject the surgical treatment recommendation. On the other hand, they rarely compromise on their medical expertise or alter their view of surgery as the solution, or the only effective treatment, for the patient’s problem. As for the patients, while they defer to the doctors’ medical expertise upon which the recommendation is based, most view the surgical recommendation as unanticipated or contrary to their personal preferences, leading to resistance. Consequently, they find it difficult to accept the recommendation within the limited time of the consultation. After exchanging information and treatment preferences, the two parties often reach an impasse, with neither side willing to make a concession. As a result, no agreement on the treatment decision can be reached. Without a clear treatment decision, the negotiation cannot progress to the next activity or toward closure (see Heath 1986; Hudak et al. 2011; Raymond and Zimmerman 2016; Robinson 2001, for discussions on the closure of medical encounters). Under such circumstances, both doctors and patients require a “way out”, and framing the treatment decision as deferred serves as that way out. By casting the treatment decision as a matter to be addressed in the future, both parties can reach an agreement and negotiate the closure of the current medical encounter.

The deferral of treatment decisions proposed by doctors

On some occasions, doctors respond to patients’ resistance to surgery by proposing a temporary deferral of treatment decisions. After presenting the rationale for the surgical treatment recommendation, doctors may offer patients additional time to consider the decision if they continue to show strong resistance. Once patients accept the doctors’ proposal, the consultation transitions into a closing phase, with the treatment decision framed as deferred.

Through inquiries

In the face of consistent and strong resistance, doctors often inquire about patients’ preferences for closing the current consultation with the treatment decision deferred. This approach gives patients additional time before making a final decision. In most cases, such inquiries receive the patients’ agreement. The following excerpt illustrates this point.

In Excerpt (4), the patient (male) is diagnosed with a lumbar disc protrusion. After reviewing the CT scan, the doctor (male) concludes that surgery is necessary. However, the patient expresses resistance to the surgical recommendation, stating that he needs to finish his farm work first. In response, the doctor proposes that the patient return in two weeks, framing it as an inquiry. The patient agrees to the doctor’s suggestion, thereby deferring the treatment decision.

After the information-gathering phase, the doctor recommends surgery (line 5). In response, the patient inquires about the necessity of surgery (line 6), expressing resistance to the treatment and seeking confirmation of the doctor’s recommendation. The doctor confirms and explains that surgery is unavoidable (lines 7–8). The patient acknowledges this with an “oh” (line 9), indicating receipt of the doctor’s medical judgment. Despite this acknowledgment, the patient resists the surgery by explicitly stating his current need for medications (line 11). He explains that his personal schedule conflicts with the surgery, as he is busy with farming at home (lines 12–13). The doctor challenges the patient’s ability to farm on several occasions (lines 14, 16). However, the patient insists on prioritizing his personal affairs and states that he will not consider surgery until after he has completed his work (lines 17–18). The doctor warns that the patient’s symptoms may worsen (line 19), but the patient insists on postponing the surgery until early July (line 26).

While neither party is willing to make a concession, both the doctor and the patient find themselves at an impasse, with no agreement on the treatment decision. As the process of care-seeking cannot proceed without a treatment decision, the encounter is unable to advance to the next stage or toward closure (Raymond and Zimmerman 2016). Under these circumstances, the doctor proposes a solution through an inquiry, suggesting that the decision-making be postponed and that another consultation be scheduled after the patient completes his work (line 32). Once the patient accepts this proposal, the treatment decision is cast as deferred.

One noteworthy aspect is that, although the consultation appears to be progressing toward closure with the future arrangement settled (Robinson 2001), the patient reopens the conversation by requesting pain medication (line 41). He claims he cannot endure the pain without painkillers and that the one he is currently using is ineffective. While filling the prescription, the doctor continues to emphasize the necessity of surgery (lines 51, 53) and elaborates on the temporary and limited efficacy of medications (lines 55–56). This highlights his insistence on the surgical treatment recommendation, even after an agreement to defer the treatment decision has been reached. The patient, in turn, begins asking about surgical details (line 70), signaling his reliance on the doctor’s professional opinion and his growing orientation toward surgery as a viable treatment, despite his initial resistance.

In the following excerpt, the doctor reiterates the inquiry about deferring the treatment decision and prescribing medications for temporary pain relief after the patient reopens the conversation, even though an agreement to defer the treatment decision has already been reached.

In Excerpt (5), the patient (female) is diagnosed with scoliosis. Based on the CT scan, the doctor (male) concludes that surgery is necessary. However, the patient finds surgery neither affordable nor acceptable. In response, the doctor proposes temporarily prescribing medications as an alternative. The patient agrees to this proposal, thereby deferring the treatment decision regarding surgery.

The doctor begins by inquiring about the patient’s own assessment of her back based on the medical image (line 2). The patient acknowledges and confirms that her back is bent like a bow (line 3). Using a perspective-display series (Maynard 1996), the doctor invites the patient to share her perspective on the symptom, facilitating her recognition of the seriousness of her condition. Through this series, a context is established in which both the doctor and the patient can mutually acknowledge the severity of the symptoms (Maynard 1996; Whitehead 2020). The doctor then diagnoses the patient with scoliosis (line 4).

Before recommending a treatment, the patient voluntarily inquires about the viability of injections through a yes/no question, implying her preference for non-surgical treatments (line 9) (Raymond 2003). Anticipating the patient’s financial concerns, the doctor first explains the high cost of the treatment (line 14). The patient and her relative respond with the interjection aiyou (“oh my”) (lines 15, 16), expressing surprise and resistance to the high-cost treatment. In response, the doctor postpones the discussion of the surgical treatment recommendation but hints at it by explaining the cause of the patient’s pain and the rationale for the treatment, until the patient again inquires about the treatment (line 25). The doctor then recommends surgery (lines 28–29), and the patient directly asks about its cost (line 30). After receiving an approximate estimate from the doctor, the patient responds with the interjection aiyou (“oh my”) (line 39) once more, indicating her resistance to surgery due to the high cost.

Later, the patient raises the issue of a lower-cost conservative treatment, asking about its feasibility (line 47). The doctor explains that the conservative treatment would only provide temporary pain relief (line 48) and would not address the bending of her back (line 51). However, the doctor’s explanation is met with resistance from the patient, as evidenced by her lack of response (line 56). Subsequently, the patient retreats to the physical examination phase and invites the doctor to recheck a higher part of her back (line 61). She claims that this part is not painful, implying that her symptoms are not as serious as the doctor has assessed (line 65). By invoking her personal feelings, the patient challenges the doctor’s epistemic basis for recommending surgery (Stivers and Timmermans 2020).

Faced with the patient’s resistance, the doctor maintains his recommendation for surgery after examining the patient’s back (lines 66–67). However, his explanation fails to elicit a response from the patient, and the negotiation of the surgical treatment decision reaches a deadlock. After a long pause of 4 s, the doctor takes the initiative. He proposes using medication temporarily for the patient and asks for her confirmation with a tag question (line 69). With the patient approving the doctor’s proposal, the consultation moves into the closing phase. The treatment decision, regarding whether or not to accept surgery, is deferred.

As in the previous case, the consultation is reopened by the patient. She inquires about surgical details, including insurance issues (lines 74–75) and postoperative recovery (lines 77, 79), reflecting her concerns about the surgery while also indicating her openness to the idea. After the doctor addresses her questions, the patient begins chatting with her relative. Later, she attempts to demonstrate to the doctor that her condition is manageable without surgery (line 85). In response, the doctor reiterates the temporary treatment plan that the patient has already approved (line 86). Clearly, framing the treatment decision as deferred is a strategy used by the doctor to close the encounter. After the patient provides her response, the consultation is closed.

Through directives

In some cases, doctors may propose deferring treatment decisions through explicit directives. Various strategies may be used to soften the force of the command. For example, in Excerpt (6), the sentence-final particle (SFP) ba, which is commonly used to solicit recipient approval or agreement, indicates the speaker’s uncertainty, and downgrades the epistemic position (Kendrick 2018; Li and Thompson 1981), is attached to the directive. This softens the force of the directive, transforming it into a proposal that requires the patient’s approval.

In this excerpt, the patient (male) is diagnosed with a spine condition, and the doctor (male) recommends surgery. The doctor emphasizes that surgery is the ultimate solution to the patient’s problem, but the patient expresses resistance to the treatment. The doctor acknowledges that the surgical recommendation is unexpected, and the patient agrees with this assessment. As the patient remains hesitant, the doctor proposes postponing the decision-making, thus framing the treatment decision as deferred. The patient accepts this proposal, and once the future arrangement is settled, the consultation moves toward closure. Below are the details.

After the physical examination, the doctor diagnoses the patient with a spine condition (line 5) and explains the cause of his current condition (lines 6–7). However, the patient does not respond, suggesting some misalignment with the doctor’s diagnosis and explanation. After a long pause of 5 s, the doctor reiterates the patient’s previously reported medical issue (line 9). The patient then confirms this with the expression shizai (“really”) (line 10), emphasizing the seriousness of the symptoms. The patient proceeds to provide additional information about his problem (lines 12, 14–15, 18), which, together with the earlier description, underscores the seriousness of his condition.

After gathering all the information, the doctor concludes that the patient needs surgery (line 19). The patient responds with a “huh” (line 20) in rising intonation, indicating his surprise. In response, the doctor confirms the necessity of surgery, asserting that it cannot be avoided in this case (line 21). The doctor’s assertion is met with the patient’s silence, which can be interpreted as passive resistance (line 22). Faced with this resistance, the doctor acknowledges the patient’s concern and suggests giving him more time to consider the surgery (line 23). The patient immediately accepts this proposal (line 24). However, the doctor then returns to the topic of surgery and further explains its rationale (line 26). Instead of acknowledging the explanation, the patient asks about the possibility of using conservative treatment (line 27), expressing his preference for this option and his resistance to surgery. The doctor acknowledges that conservative treatment may be helpful but clarifies that its effectiveness is only temporary (lines 28, 34). He reasserts that surgery is unavoidable due to the patient’s condition (lines 35–36). Once again, the patient exhibits resistance by withholding any response (line 37).

The doctor responds to the patient’s resistance with an “ah” (line 38). However, this fails to elicit any response from the patient. At this point, the negotiation between the two parties reaches an impasse, with the doctor strongly advocating for surgery as an unavoidable treatment and the patient consistently resisting it. After a brief pause, the doctor takes the initiative by proposing the temporary use of medication through a directive (line 40). The patient immediately accepts this proposal (line 41). The doctor then begins to prescribe the medication, creating a closing-relevant environment (Heath 1986) and positioning the final treatment decision as deferred.

As the doctor writes the prescription, the patient interjects and reopens the negotiation. He inquires about the duration of the surgery (line 43), indicating a willingness to consider it. He also complains that the medication is not very effective (line 52). The doctor attributes the medication’s inefficacy to the severity of the patient’s condition, subtly reinforcing the necessity of surgery, though he does not explicitly try to persuade the patient to accept it. After explaining the use of the medication, the doctor begins to negotiate the closure of the consultation by proposing a follow-up visit for the following week (line 62). Once the patient agrees to this proposal, the consultation is closed.

Summary

In this section, the doctor and patient find themselves at an impasse, with the two parties holding conflicting treatment preferences during their negotiation of the treatment decision. While the doctor recommends surgery and positions it as the final solution (often the only effective treatment) to the patient’s problems, the patient resists this treatment. With the treatment decision unresolved, the progress of the interaction is suspended. The consultation cannot move forward to the closing phase without resolving this impasse. The deferral of treatment decisions serves as a strategy to break the deadlock. In this case, it is the doctor who takes the initiative, proposing to defer making a clear decision on the patient’s behalf.

Patients have rights that exist independently of medical knowledge, including the fundamental right to reject treatment proposals based on medical expertise and scientific evidence (Lindström and Weatherall 2015). Decision-making rights are typically more pronounced when patients are faced with more invasive or high-stakes treatments, such as surgery (Landmark et al. 2015). However, in the excerpts presented in this section, it is the doctors who propose deferring treatment decisions. This does not infringe upon the patients’ ultimate right to make their own treatment choices.

The reasons for patients’ resistance to surgical recommendations are outlined in the preceding sections—conflicting personal schedules in Excerpt (4), financial constraints in Excerpt (5), and hesitancy due to unexpected recommendations in Excerpt (6). The doctors recognize the patients’ reluctance to accept the surgical recommendations at that moment. In response, they suggest deferring the treatment decision while keeping surgery as an option for the patient’s benefit. This proposal reflects the doctors’ sensitivity to the patients’ concerns and priorities. It aligns with the patients’ needs by offering them additional time and space for consideration. In most cases, the patients accept these proposals promptly.

Importantly, when the consultation proceeds to the closing phase after the parties have agreed to defer making a clear treatment decision, patients often reopen the discussion with surgery-related questions. Although they had previously shown clear resistance to surgery, patients continue to rely on the doctor’s professional judgment and view surgery as one option to consider—though not one they are ready to immediately accept.

In this sense, similar to the previous section, the doctor–patient relationship remains balanced yet conflicted. The deferral of treatment decisions serves as a strategy to close the consultation when no immediate acceptance or rejection of surgery can be reached.

The interplay between doctors’ and patients’ rights in treatment negotiations

From the perspective of knowledge distribution, the negotiation of treatment decisions primarily involves two epistemic domains: (1) the domain of expertise and (2) the domain of experience. The domain of biomedical expertise is held by doctors, whose contributions reflect the “voice of medicine” (Mishler 1984, p. 103) and embody a technical, scientific perspective. In contrast, the domain of subjective experience belongs to patients, whose contributions represent the “voice of the lifeworld” (Mishler 1984, p. 103) and express everyday experiences through a natural, lived perspective.

More specifically, doctors’ epistemic primacy is grounded in their biomedical knowledge and expert reasoning regarding diagnoses and treatments. They have the primary right to interpret patients’ symptoms, provide diagnoses, and recommend subsequent treatments. Patients, on the other hand, claim primacy over knowledge of their personal preferences and their subjective experience of illness (Landmark et al. 2015; Lindström and Weatherall 2015; Stivers and Timmermans 2020; Timmermans and Mauck 2005).

Doctors’ primacy in the domain of medical knowledge grants them superior deontic rights to direct the course of patient treatment, including the authority to “prescribe biomedical treatment” (Stivers and Timmermans 2020, p. 3) and to “specify what the decision should be” (Timmermans et al. 2018, p. 521). While doctors have the authority to recommend and prescribe treatments, patients retain the ultimate right to accept or reject these proposals, regardless of the scientific evidence (Lindström and Weatherall 2015).

In the negotiation of surgical treatment recommendations in China, both doctors and patients hold onto the knowledge within their respective epistemic domains, while also showing respect for the knowledge within each other’s domain. On the one hand, doctors assert their position on surgery based on biomedical reasoning, while patients express consistent resistance to surgery, rooted in their personal treatment preferences. On the other hand, doctors acknowledge patients’ preferences by considering the treatment decision as contingent upon the patients’ desires. Similarly, patients view doctors’ medical judgments as one of the key factors in their treatment decisions, as demonstrated by their voluntary inquiries about surgery and the absence of overt rejections, despite their resistance.

Nevertheless, the conflict between the two parties’ treatment preferences results in difficulty reaching a consensus on the treatment decision. Without an agreement in place, the current consultation cannot proceed to the closing phase. In Chinese clinical contexts, when the negotiation of the surgical treatment decision reaches an impasse—where doctors insist on the privileged status of surgery and patients express explicit resistance to it—a deferred decision, rather than an immediate acceptance or rejection, is often the solution. This approach provides a substantial basis for both doctors and patients to reach an agreement without directly infringing on each other’s rights. The deferred decision is proposed either by patients (Group 1), who exercise their deontic rights themselves, or by doctors (Group 2), who presuppose the patient’s agreement and suggest deferring the decision on their behalf. In both cases, the participants recognize the patient as the ultimate decision-maker with the final right to determine the course of treatment. Once an agreement to defer the decision is reached, the consultation proceeds to the closing phase.

The deferral of treatment decisions arises from the interplay of both parties’ rights during the negotiation of surgical treatment recommendations. It reflects a balanced yet delicate relationship between doctors and patients. Once an agreement on deferring the treatment decision is reached, both parties can move beyond the negotiation impasse and begin negotiating the closure of the consultation, without the need for an immediate acceptance or rejection.

Conclusions

The present study aims to explore an alternative outcome of medical consultations, beyond patients’ acceptance or rejection of the treatment recommendations proposed by doctors. Specifically, it examines participants’ agreement to defer treatment decisions. This outcome frequently arises in doctor–patient negotiations of surgical treatment recommendations in China. We argue that deferring decisions is often employed by both doctors and patients as a strategy to close the consultation when the two parties encounter a negotiation impasse due to conflicting treatment preferences.

Due to the limited scope of our data, this paper focuses exclusively on orthopedic and proctological consultations, where most patients do not have critical conditions, making a deferred treatment decision more acceptable. This outcome would not be appropriate in cases where patients face urgent or life-threatening conditions. The specific contexts in which the “deferring” strategy can be applied, as well as subsequent doctor–patient negotiations of surgical treatments following the current consultation, will be the focus of our future studies.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the Data file.

Notes

Centre for Health Statistics and Information. An analysis report of the national health services survey from January to May in 2023. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/mohwsbwstjxxzx/s7967/202309/c40e2abfa7524e0e9c81f68422bddef4.shtml (accessed December 1, 2023).

References

Chappell P, Toerien M, Jackson C, Reuber M (2018) Following the patient’s orders? Recommending vs. offering choice in neurology outpatient consultations. Soc Sci Med 205:8–16

Clark SJ, Hudak PL (2011) When surgeons advise against surgery. Res Lang Soc Interact 44(4):385–412

Heath C (1986) Body movement and speech in medical interaction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England

Hu L, Ding H, Liu S, Wang Z, Hu G, Liu Y (2020) Influence of patient and hospital characteristics on inpatient satisfaction in China’s tertiary hospitals: a cross‐sectional study. Health Expect 23(1):115–124

Hudak PL, Clark SJ, Raymond G (2011) How surgeons design treatment recommendations in orthopaedic surgery. Soc Sci Med 73(7):1028–1036

Hudak PL, Clark SJ, Raymond G (2013) The omni-relevance of surgery: how medical specialization shapes orthopedic surgeons’ treatment recommendations. Health Commun 28(6):533–545

Jefferson G (2004) Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In: Lerner G (ed) Conversation analysis: studies from the first generation. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp 13–31

Kendrick KH (2018) Adjusting epistemic gradients: the final particle ba in Mandarin Chinese conversation. East Asian Pragmatics 3(1):5–26

Koenig CJ (2011) Patient resistance as agency in treatment decisions. Soc Sci Med 72(7):1105–1114

Landmark D, Gulbrandsen P, Svennevig J (2015). Whose decision? Negotiating epistemic and deontic rights in medical treatment decisions. J Pragmat 78:54–69

Lee DC, Wang J, Shi L, Wu C, Sun G (2022) Health insurance coverage and access to care in China. BMC Health Serv Res 22(1):140

Li X, Lu J, Hu S, Cheng KK, De Maeseneer J, Meng Q, Hu S (2017) The primary health-care system in China. Lancet 390(10112):2584–2594

Li CN, Thompson SA (1981) Mandarin Chinese: a functional reference grammar. University of California Press, Berkeley CA

Liang Z, Howard P, Wang J, Xu M, Zhao M (2020) Developing senior hospital managers: does ‘one size fit all’? – Evidence from the evolving Chinese health system. BMC Health Serv Res 20(1):1–14

Lindström A, Weatherall A (2015) Orientations to epistemics and deontics in treatment discussions. J Pragmat 78:39–53

Lo D, Wu F, Chan M, Chu R, Li D (2018). A systematic review of burnout among doctors in China: a cultural perspective. Asia Pacific Family Medicine 17:3

Maynard DW (1996). On “realization” in everyday life: The forecasting of bad news as a social relation. Am Sociol Rev 109–131

Mishler E (1984). The discourse of medicine: dialectics of medical interviews. New Jersey: Ablex

Niu L (2014) Study on the structure of doctor-patient conversation in outpatient departments. Central China Normal University, China

Peräkylä A (1998) Authority and accountability: the delivery of diagnosis in primary health care. Soc Psychol Q 61(4):301–320

Raymond G (2003) Grammar and social organization: Yes/no interrogatives and the structure of responding. Am Sociol Rev 68:939–967

Raymond G, Zimmerman DH (2016). Closing matters: Alignment and misalignment in sequence and call closings in institutional interaction. Discourse Studies 18(6):716–736

Reuber M, Toerien M, Shaw R, Duncan R (2015) Delivering patient choice in clinical practice: a conversation analytic study of communication practices used in neurology clinics to involve patients in decision-making. Natl Inst Health Care Res Health Serv Deliv Res 3(7):169

Robinson JD (2001) Closing medical encounters: two physician practices and their implications for the expression of patients’ unstated concerns. Soc Sci Med 53(5):639–656

Stivers T (2005b) Parent resistance to physicians’ treatment recommendations: one resource for initiating a negotiation of the treatment decision. Health Commun 18(1):41–74

Stivers T (2005a) Non-antibiotic treatment recommendations: delivery formats and implications for parent resistance. Soc Sci Med 60(5):949–964

Stivers T, Timmermans S (2020) Medical authority under siege: how clinicians transform patient resistance into acceptance. J Health Soc Behav 61(1):60–78

Stivers T (2006) Treatment decisions: negotiations between doctors and parents in acute care encounters. In: Heritage J, Maynard DW (eds) Communication in medical care: interaction between primary care physicians and patients. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 279–312

Sun Y, Gregersen H, Yuan W (2017) Chinese health care system and clinical epidemiology. Clin Epidemiol 9:167–178

Timmermans S, Mauck A (2005) The promises and pitfalls of evidence-based medicine. Health Aff 24(1):18–28

Timmermans S, Yang A, Gardner M, Keegan CE, Yashar BM, Fechner PY, Sandberg DE (2018) Does patient-centered care change genital surgery decisions? The strategic use of clinical uncertainty in disorders of sex development clinics. J Health Soc Behav 59(4):520–535

Toerien M (2018) Deferring the decision point: treatment assertions in neurology outpatient consultations. Health Commun 33(11):1355–1365

Toerien M (2021) When do patients exercise their right to refuse treatment? A conversation analytic study of decision-making trajectories in UK neurology outpatient consultations. Soc Sci Med 290:114278

Toerien M, Shaw R, Reuber M (2013) Initiating decision‐making in neurology consultations: ‘recommending’ versus ‘option‐listing’ and the implications for medical authority. Sociol Health Illn 35(6):873–890

Toerien M, Jackson C, Reuber M (2020) The normativity of medical tests: test ordering as a routine activity in “new problem” consultations in secondary care. Res Lang Soc Interact 53(4):405–424

Whitehead KA (2020). The problem of context in the analysis of social action: The case of implicit whiteness in post-apartheid South Africa. Social Psychology Quarterly 83(3):294–313

Wu Y, Zhang Z, Zhao N, Yan Y, Zhao L, Song Q, Zhang Z (2022) Primary health care in China: a decade of development after the 2009 health care reform. Health Care Sci 1(3):146–159

Zhu J, Song X (2022) Changes in efficiency of tertiary public general hospitals during the reform of public hospitals in Beijing, China. Int J Health Plan Manag 37(1):143–155

Zhu J, Li W, Chen L (2016) Doctors in China: improving quality through modernisation of residency education. Lancet 388(10054):1922–1929

Zou Y, Zhang X, Hao Y, Shi L, Hu R (2015) General practitioners versus other physicians in the quality of primary care: a cross-sectional study in Guangdong Province, China. BMC Fam Pract 16(1):1–8

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first author, LL: conceptualization, methodology, data collecting, data analysis, writing original draft; The corresponding author, WM: data analysis, review, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The ethical application was approved by the Ethical Committee of the School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shandong University. It adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and the University’s principles and research guidelines. The committee approved the project and assigned it the reference number ESCBMSSDU2019-1-056. Approval body: Ethical Committee of the School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shandong University. Date of approval: 10/12/2019. Scope of approval: Humanities and Social Sciences.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Prior to the consultation, the assistant informed patients that their conversations would be recorded for academic research and provided them with consent forms. The consent form included a statement specifying that the recordings were solely for research purposes, that the audio would be specially processed and anonymized to protect the participants’ identities, and that it outlined the purpose of the research, participation, potential risks, data usage, and consent to publication. Patients were also informed that their decision to consent to the recording was entirely voluntary and that the doctor would not alter the treatment based on whether the patient agreed to the recording. If the patient consented to being recorded and signed the consent form, the assistant would activate the recording device, and the doctor would proceed with the consultation. If the patient declined, the assistant would refrain from using the recording device, and the doctor would proceed with the consultation as usual. The recording period lasted from February 2021 to September 2021. All participants voluntarily participated in the research and signed the consent forms. The submission does not include any identifying information or images.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Ma, W. Finding a “way out”: deferring treatment decisions as a strategy for closing medical consultations in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 952 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05344-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05344-3