Abstract

Climate change increasingly impacts health and livelihoods, with extreme climate events causing significant economic losses and health risks. Understanding how socio-economic drivers and political orientation influence public risk perception is key for effective climate policies. This study aims to show how gender, age, income, political orientation, education, and place of residence shape perceptions of climate change as compared to other global crises (epidemics and economic crises), using Italy and Sweden as case studies (N = 12,476 individuals representative of the general population in both countries). Our findings indicate that women, low-income, and left-leaning respondents report higher risk perceptions across all hazards compared to men, higher-income, and right-leaning individuals. Younger individuals perceive higher risks for climate change and economic crisis but lower for epidemics compared to older individuals. These findings illustrate the importance of tailored communication strategies to address diverse perceptions and enhance public support for climate policies. By contextualizing climate change risk perceptions with other global crises, this study does not only provide crucial insights for advancing our understanding of risk perception dynamics in the context of global challenges but can also inform policymakers in designing interventions that consider socio-economic disparities and ideological influences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change refers to “long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns” mainly driven by human activities such as deforestation, industrial processes and burning fossil fuels, which release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere thus contributing to a rise in temperatures (United Nations 2024). Its impacts on health, livelihoods and ecosystems are now more evident than ever, with projections showing escalating risks without mitigation and adaptation actions (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2023; Romanello et al. 2023). For instance, in 2022 Europe witnessed over 61,000 heat-related deaths during the summer (Ballester et al. 2023), and €18.7 billion in economic losses from climate extreme events (Van Daalen et al. 2024). The climate crisis is not an isolated event. The likelihood of potential epidemics and economic instability poses an escalating risk to our societies (Buhaug and Vestby 2019; Meadows et al. 2023; Petrova et al. 2023). These are not stand-alone events; rather, they act synergistically, amplifying each other’s impact (Ford et al. 2022; Kotz et al. 2024). In this context, understanding risk perception across multiple hazards becomes critical for comprehending real-world scenarios where individuals face threats simultaneously. How individuals perceive climate change and potential concurrent hazards often influences behaviours and policy effectiveness, offering valuable insights for preventive measures and risk communication. A holistic approach to tackling multiple hazards can enhance preparedness and move beyond a siloed, hazard-by-hazards perspective.

Socio-demographic and cultural factors can significantly influence risk perception. Experiential and cultural factors, including social norms and value orientations, are strong predictors of climate change risk perceptions. Alongside these, socio-demographic determinants have also been extensively studied to understand the behaviours of different population groups towards global crises (Van Der Linden 2015). For instance, political orientation can skew perceptions of the impact of climate extremes, with right-leaning respondents often perceiving less impact compared to those of other political orientations (Albright and Crow 2019; Bayer and Genovese 2020; Fairbrother 2013; Hazlett and Mildenberger 2020; Lujala et al. 2015; McCright and Dunlap 2011, pp. 2001–2010; McGrath and Bernauer 2017; Mildenberger and Tingley 2019; Ogunbode et al. 2017). This tendency reflects how individuals trust, cooperate and align their beliefs with similar social groups. This pattern has been observed in other crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where both, worldviews (a cultural factor) and gender (a socio-demographic factor), were significant predictors of risk perception (Bhuiya et al. 2021; Cipolletta et al. 2022; Dryhurst et al. 2020; Mondino et al. 2020; Schneider et al. 2021). These insights highlight the importance of comparing how different socio-economic groups perceive and respond to risks, thus seeking common explanations across diverse contexts. Italy and Sweden serve as cases in point. Italy’s dense population and geographic susceptibility to climate extremes, such as heatwaves and flooding, contrast with Sweden’s relatively low sparse population density and colder climate, which mitigates the impact of such climate-related events (Ministry of the Environment. Government Offices of Sweden 2020; SEI 2023).

This study aims to explore how socio-economic characteristics influence public risk perception of climate change. While several previous studies have explored socio-economic perceptions of climate change (Bradley et al. 2020; Bush and Clayton 2023; Fairbrother 2013; Huber et al. 2020), this study contextualizes risk perception by comparing climate change to other global crises, epidemics and economic crises. To this end, we use survey data from Italy and Sweden (N = 12,476) as a first exemplar and (1) examine to what extent gender, age, income, political orientation, education, employment status, and place of residence are associated with the different domains of risk perception of climate change, epidemics, and economic crises; (2) compare public risk perceptions of climate change with those of other global crises, epidemics and economic crises; (3) identify similarities or differences between Italy and Sweden, offering insights into cross-country variability.

Methods

Study population

Data for this study were gathered from three, pooled cross-sectional surveys conducted in Italy and Sweden in August 2020, November 2020, and August 2021. These surveys sampled individuals from existing panels maintained by Kantar Sifo (100,000 individuals in each country), a marketing research company. These three independent samples were representative of the general population in terms of age and gender in both countries.

The surveys examined how individuals perceive risks associated with several hazards. Each hazard was assessed across seven areas of public risk perception, including the likelihood of occurrence, its impact on individuals and others, preparedness by both individuals and authorities and the level of knowledge possessed by individuals and authorities. Here we consider four risk perception dimensions (likelihood, individual impact, knowledge from authorities, and impact on others) for three hazards (climate change, epidemics and economic crisis) measured on a Likert-type scale (being 1 the minimum and 5 the maximum). In this study, likelihood, individual impact and impact on others were considered as measures of risk perception, while knowledge from authorities was considered a proxy variable for trust in authorities.

This study was approved by the Italian Research Ethics and Bioethics Committee (Dnr 0043071/2019) and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2019-03242). The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards set by the European Union under Horizon 2020 (EU General Data Protection Regulation and FAIR Data Management). Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with all participants providing informed consent prior to completing the survey.

Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the study participants

Several demographic and socio-economic factors were collected: gender (female vs male), age (<40, 41–64, ≥65), income (Not enough, Enough, More than enough), political orientation (Clear to the left, A bit to the left, Neither left nor right, A bit to the right, Clear to the right), education (university degree vs no university degree), employment (yes vs no), place of residence (capital region vs other). We recognize that political labels like “left” and “right” are not directly comparable across cultural contexts due to differences in ideologies and social values (Bauer et al. 2017). Yet, in our case, the left-right political spectrum broadly represents a divide between prioritizing social equality and government support (left) versus free markets and individual responsibility (right) (Agnew and Shin 2017; Karlsson and Lindqvist, Jesper, 2024). Nonetheless, we recognise contextual differences and thus report results separately for each country.

Of the 12,476 individuals eligible for analysis (6047 in Italy and 6429 in Sweden), we observed a comparable gender distribution across countries (Table 1). The age profile in Italy was skewed towards middle-aged adults (50.6%), while Swedish participants were more evenly spread across younger (≤40 years; 35%) and older (≥65 years; 23.8%) age groups. A majority of Swedish participants (57.8%) reported having incomes that they consider to be ‘More than enough’, a significantly higher proportion than the 37% of Italian participants. Similarly, a higher percentage of Italians (21.1%) reported having ‘Not enough’ income, compared to only 13% of Swedes. Swedish participants were more likely to identify with right-wing political orientations, with 26.4% describing themselves as ‘A bit to the right,’ compared to 18.7% in Italy. In the Italian sample, 1,403 respondents (23.2%) chose “do not wish to say” for political orientation. While substantial, this aligns with the World Values Survey, where about 15% of Italians opted out of this question in recent waves (2005–2009 and 2017–2022) (Inglehart, R., C. Haerpfer, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin & B. Puranen (eds.), 2022). A similar pattern appears in our Swedish sample, with 251 respondents (3.9%) choosing “do not wish to say”, consistent with Sweden’s World Values Survey trends. This alignment with broader survey patterns informs our data interpretation. Educational attainment was also higher in Sweden, with 58.6% of Swedish participants holding university degrees compared to 32.3% of Italians. Employment rates followed a similar pattern, with 67.5% of Swedes employed versus 55.4% of Italians.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was carried out to compile the demographics of the sample under study. To address the overrepresentation of individuals from capital regions, inverse probability weighting was applied. The associations between the domains of risk perception and the socio-economic characteristics were assessed using an ordinal logistic regression approach. This statistical method has been commonly used to analyse Likert-type scale survey data as it preserves the ordering of response options whilst making no assumption about the intervals between the answer options (Sullivan et al. 2013). The findings were expressed in terms of odds ratios (ORs) along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To exemplify, the OR for the association between gender (dependent variable) and one of the four dimensions of risk perception should be interpreted as a measure of how being a woman compared to a man influences the odds of being in the next category of risk perception rather than high vs low, under the proportional odds assumption (i.e. the effect of being a women on the perception of risk is assumed to be constant across all levels of risk perception) (Keith McNulty 2024). The analysis was stratified by country. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The study utilized data from three pooled cross-sectional surveys (N = 12,476) conducted in Italy and Sweden during August 2020, November 2020, and August 2021, targeting individuals from panels by Kantar Sifo. These samples, representative in terms of age and gender, examined public risk perceptions related to climate change, epidemics, and economic crises. Each hazard was assessed across four dimensions: likelihood, individual impact, knowledge from authorities, and impact on others. Demographic and socio-economic data, including gender, age, income, political orientation, education, employment, and residence, were collected. Descriptive analyses and ordinal logistic regression were used to explore associations between risk perception dimensions and socio-economic characteristics, with results presented as odds ratios (more details in the methods section).

Risk perception descriptives

The descriptive information on the risk perception of climate change on the dimensions of likelihood, impact, knowledge from authorities and impact on others, compared to epidemics, and economic crises is displayed in Fig. 1 for Italy, and Fig. 2 for Sweden.

Climate change risk perception

Overall, individuals with a clear-to-the-left political orientation had the highest risk perception in Italy and Sweden for all risk perception dimensions except knowledge from authorities in Italy, in which respondents reporting a central orientation had the highest level. Shifting from clear-to-the-left to clear-to-the-right, there was a decrease in perceived risk, with right-leaning individuals reporting the lowest level of risk perception in both countries across all dimensions, including knowledge from authorities.

Risk perception on other hazards

Regarding the risk perception towards other hazards, for epidemics, women and left-leaning participants generally reported the highest level across the different dimensions while men, right-leaning individuals, and individuals older than 65 years old reported the lowest. For economic crisis, respondents stating not having enough income and being left-leaning voters had the highest level of risk perception, whereas individuals over 65 y.o., individuals with more than enough income, and right-leaning participants reported the lowest.

Association between socio-economic features and differences in risk perception

Climate change risk perception

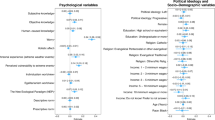

Concerning political orientation, individuals with left-wing orientations reported the highest risk perception of climate change in both countries, with a progressive decrease in all dimensions towards right-leaning orientations (Fig. 3). In both countries, women had higher odds of risk perception to climate change compared to men, with the odds reaching up to 2 times higher for the dimension of impacts on others in Italy. Individuals over 65 in Italy reported a 33% lower perception of knowledge from authorities compared to respondents younger than 40. In other dimensions, fewer significant differences among age groups were observed, with a 28% lower impact perception among respondents over 65 y.o. in Sweden and a 25% lower perceived likelihood in the same group in Italy. Income-related differences were only significant in Sweden, where individuals with higher incomes reported between 28 and 38% lower risk perception for likelihood and impacts, respectively. Respondents from both countries with higher incomes reported a higher perception of knowledge from authorities, with those in Italy who stated having “more than enough” reporting a 94% higher perception. Higher educational levels were only significant in Italy, where individuals with higher education reported a 45% higher risk perception on likelihood. Finally, few clear patterns were observed for employment and place of residence, with an 18% lower likelihood perception among employed respondents in Sweden, and a 13% higher risk perception for knowledge from authorities in the same country for those living in the capital.

Odds Ratio (OR) and 95% CIs for climate change on each of the seven variables (gender, age, income, political orientation, education, employment status, and place of residence) by the risk perception dimensions of likelihood and impact, knowledge from authorities and impact on others for both countries, Italy and Sweden.

Risk perception on other hazards

Regarding political orientation, dimensions such as likelihood or knowledge from authorities showed significant association in both hazards, with similar patterns as those found for climate change: right-leaning respondents generally reported less risk perception. Both countries showed clear differences in knowledge from authorities, with up to an 84% lower perception of epidemics in Italy for the right-leaning respondents compared to their counterparts. In addition to climate change, women also had a higher risk perception for all dimensions of epidemics and economic crises in both countries, except for knowledge from authorities (Figs. 4, 5). In particular, women had up to 2 times higher perception of impact on others for epidemics compared to men. Age-related differences were most significant in Italy for an economic crisis, with older individuals perceiving up to 67% lower likelihood. Differences in economic crises perception were also found in two dimensions in Sweden for the older group. For epidemics, this pattern was also mirrored in the likelihood dimension, but not in the dimension of impact, with individuals over 65 perceiving 2.36 higher odds than younger groups.

Odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs for epidemics on each of the seven variables (gender, age, income, political orientation, education, employment status, and place of residence) by the risk perception dimensions of likelihood and impact, knowledge from authorities and impact on others for both countries, Italy and Sweden.

Odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs for economic crisis on each of the seven variables (gender, age, income, political orientation, education, employment status, and place of residence) by the risk perception dimensions of likelihood and impact, knowledge from authorities and impact on others for both countries, Italy and Sweden.

Similar patterns were observed for income-related differences in both hazards, with respondents with higher income reporting lower risk perception. The likelihood dimension had significant differences in Italy, with up to an 82% lower perception among better-off individuals for economic crises. For the dimension of knowledge from authorities, higher income participants reported up to 2.32 times higher odds of perceiving risk than those with not enough income for economic crises. Higher education did not show differences in risk perception for economic crises, but it did for epidemics in both countries, with a 24% higher perception of likelihood in Sweden. Employment status was not a significant factor for risk perception of an epidemic, while a 45% and 23% higher perception of economic crises were found in Italy for the impact and impact on others, respectively. Finally, living in the capital was associated with a 27% and 33% higher perception of the likelihood of epidemics and economic crises, respectively in Italy. A similar pattern was observed for knowledge from authorities in Sweden, with about a 20% increase for epidemics and economic crises.

Discussion

Our study identifies key patterns in risk perception primarily influenced by political orientation, gender, and age with significant differences observed in the contexts of climate change, epidemics, and economic crisis. Political orientation has a crucial role, with left-leaning individuals showing higher risk perception compared to their right-leaning counterparts. In addition, women and younger age groups generally perceived higher risks across various hazards compared to men and older age groups. However, an exception is observed for the impact of epidemics, where older individuals perceive greater risks.

Our findings revealed a clear pattern regarding political orientation in both countries, with left-leaning respondents showing higher risk perception for climate change compared to right-leaning individuals. Previous research has explored the relationship between political identity and attitudes toward climate policies, emphasising that these attitudes are often driven by beliefs about economic and social impacts (Bayer and Genovese 2020; Colantone et al. 2024; Gaikwad et al. 2022; Hazlett and Mildenberger 2020). Political affiliation and economic stakes can shape preferences for redistribution and compensation policies. In line with this, right-leaning individuals have been argued to be more sceptical of the economic benefits of climate action, perceiving it as economically restrictive (Colantone et al. 2024; Tranter and Booth 2015). A prominent explanation for this is the previously described “directional motivated reasoning”, in which individuals tend to reject new information that contradicts their existing beliefs (Druckman and McGrath 2019; Kunda 1990). This phenomenon is particularly relevant in the context of climate change, where misinformation and conspiracy theories tend to proliferate within right-wing circles (Bayes and Druckman 2021; Druckman and McGrath 2019; Hutmacher et al. 2024). Gender differences were evident, as women tend to have a higher risk perception for climate change, also consistent with previous literature reporting gender differences based on social roles and socialization (Bush and Clayton 2023; Ergun et al. 2024; McDowell et al. 2020). Age influenced risk perception as well, with risk perception generally decreasing as age increases. As reported in the literature, this finding can be explained by the cohort effect in which younger generations, in contrast with the older ones, have been more exposed to climate change issues both in media and formal education (Franzen and Vogl 2013; Stevenson et al. 2014). Income levels further influenced risk perception, with higher income generally associated with lower risk perception for climate change. Overall, men, elderly, right leaning, and high-income respondents tend to perceive lower risks from climate change. These groups often hold more power in society, which may influence the impact of their perceptions and resistance to change (The PoReSo Research Group 2023). This may be amplified by the false consensus effect, where these groups overestimate the extent to which their scepticism or lower concern about climate change is shared by others (Leviston et al. 2013; Mildenberger and Tingley 2019). This cognitive bias reinforces their existing beliefs, making them more resistant to differing views and further solidifying their lower-risk perceptions (Ross et al. 1977).

Employment did not show a significant role in risk perception and education mainly showed to be relevant in Italy, with higher risk perception in some dimensions among those with a university degree. Living in a capital region affected only the likelihood dimension in Italy and knowledge from authorities in Sweden, as urban residents might feel more likely to be exposed to hazards (UNDRR 2022). Another explanation could be that cities tend to gather more left-leaning individuals, who have higher risk perception levels than their counterparts (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. 2023). Knowledge from authorities appeared to be distinct from the other three dimensions. This is in line with previously reported literature suggesting that this dimension does not significantly contribute to overall risk perception but serves as a proxy for “trust” (Dryhurst et al. 2020 ; Paniello-Castillo et al. 2025). Additionally, this inverse relationship is also expected as higher trust in authorities typically corresponds with lower risk perception (Bulut and Samuel 2023; Lee et al. 2023).

We also observed differences among global crises, with a more pronounced left-right wing pattern in climate change compared to other global crises. This effect may be attributed to the increasing polarization of climate change as a topic used by political parties in their agendas and campaigns (Falkenberg et al. 2022; Smith et al. 2024, pp. 1973–2022). Furthermore, differences in risk perception among income groups were more pronounced for economic crises than for climate change and epidemics, likely because individuals with lower incomes and more instability are more vulnerable to economic downturns (OECD 2021). Age also influenced risk perception differently across crises, with epidemics eliciting a more pronounced perception among the eldest group, potentially due to the severe impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older individuals, who were more susceptible to severe outcomes (Harris 2023). In contrast, the elderly perceived lower risks to climate change although they are more vulnerable to its effects, such as extreme hot and cold temperatures (Ballester et al. 2023). No relevant differences across global crises were observed concerning gender, education, employment and place of residence.

This study presents several noteworthy strengths. First, we included a total of 12,476 participants, a large sample representative of the Swedish and Italian population for age and gender that enabled us to comprehensively examine different dimensions of risk perception and compare them with each other. Second, the cross-country comparison allowed us to understand societal patterns and draw conclusions about contextual factors in Italy and Sweden. Nevertheless, this study has potential limitations. First, although the sampling strategy aimed to minimize the source of selection bias, it cannot be entirely discarded since there may be an underrepresentation of certain societal groups (e.g., migrants). This could limit the generalizability of the results to these populations, as well as to contexts beyond the European Union. Second, we did not assess the different policies in place regarding climate action, pandemic response and preparedness, or economic stability, which could influence individuals’ risk perception differently in both countries. Finally, we did not specify what hazards were within climate change, epidemics and economic crises and left it to respondents’ interpretations. This could either be a limitation since their answers might have depended on previous experiences on concrete hazards, or a strength as not restricting respondents’ definition of the crises themselves might have yielded unaltered insights. Moreover, we believe that respondents would likely interpret specific risks like unemployment within economic crises, hence providing similar insights to those observed.

To further advance this field of research, future studies could build on these findings to keep exploring risk perception of multiple global crises and hazards through innovative methodologies. For instance, developing a holistic risk perception index capturing multiple risk perception approaches could provide a comprehensive understanding of these dynamics. Moreover, research needs to be performed in diverse settings, such as in countries with other types of social contracts and political systems as well as in regions more affected by climate change, such as small island states, or among more vulnerable populations. As one of the few studies to explore risk perception about multiple hazards, our findings offer valuable evidence for policymaking as they highlight the importance of understanding risk perception according to socio-economic groups, supporting the design of tailored and effective risk management and crisis prevention measures.

Conclusion

Our findings reveal that women, low-income individuals, and left-leaning respondents reported higher risk perceptions across all hazards compared to men, higher-income, and right-leaning individuals in both countries. This study provides evidence that political orientation, gender, income and age play a critical role in shaping risk perception across various crises. Given the ongoing and upcoming global crises, such as climate change, political conflicts, wars, and epidemics, incorporating risk perception into policymaking and risk management is crucial. Our findings highlight the need for tailored communication strategies to address diverse social groups and their respective perceptions. Furthermore, they also underscore the importance of addressing nationalistic and psychological biases to foster a more accurate understanding and stronger support for effective climate policies.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository titled “A comparative dataset on public perceptions of multiple risks during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy and Sweden”, https://zenodo.org/record/5653322#.YoIf4OhBw2x.

References

Agnew J, Shin M (2017) Spatializing populism: Taking politics to the people in Italy. Ann Am Assoc Geogr 107(4):915–933. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2016.1270194

Albright EA, Crow D (2019) Beliefs about climate change in the aftermath of extreme flooding. Clim Change 155(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02461-2

Ballester J, Quijal-Zamorano M, Méndez Turrubiates RF, Pegenaute F, Herrmann FR, Robine JM, Basagaña X, Tonne C, Antó JM, Achebak H (2023) Heat-related mortality in Europe during the summer of 2022. Nat Med 29(7):1857–1866. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02419-z

Bauer PC, Barberá P, Ackermann K, Venetz A (2017) Is the left-right scale a valid measure of ideology?: Individual-level variation in associations with “Left” and “Right” and Left-Right Self-Placement. Polit Behav 39(3):553–583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9368-2

Bayer P, Genovese F (2020) Beliefs about consequences from climate action under weak climate institutions: Sectors, home bias, and international embeddedness. Glob Environ Polit 20(4):28–50. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00577

Bayes R, Druckman JN (2021) Motivated reasoning and climate change. Curr Opin Behav Sci 42:27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.02.009

Bhuiya T, Iii RK, Conte MA, Cervia JS (2021) Predictors of misperceptions, risk perceptions, and personal risk perceptions about COVID-19 by country, education and income. J Investig Med 69(8):1473–1478. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2021-001835

Bradley GL, Babutsidze Z, Chai A, Reser JP (2020) The role of climate change risk perception, response efficacy, and psychological adaptation in pro-environmental behavior: A two nation study. J Environ Psychol 68:101410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101410

Buhaug H, Vestby J (2019) On growth projections in the shared socioeconomic pathways. Glob Environ Polit 19(4):118–132. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00525

Bulut H, Samuel R (2023) The role of trust in government and risk perception in adherence to COVID-19 prevention measures: Survey findings among young people in Luxembourg. Health Risk Soc 25(7–8):324–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2023.2256794

Bush SS, Clayton A (2023) Facing change: Gender and climate change attitudes worldwide. Am Political Sci Rev 117(2):591–608. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000752

Cipolletta S, Andreghetti G, Mioni G (2022) Risk perception towards COVID-19: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(8):4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084649

Colantone I, Di Lonardo L, Margalit Y, Percoco M (2024) The political consequences of green policies: Evidence from Italy. Am Political Sci Rev 118(1):108–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055423000308

Druckman JN, McGrath MC (2019) The evidence for motivated reasoning in climate change preference formation. Nat Clim Change 9(2):111–119. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0360-1

Dryhurst S, Schneider CR, Kerr J, Freeman ALJ, Recchia G, van der Bles AM, Spiegelhalter D, van der Linden S (2020) Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J Risk Res 23(7–8):994–1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193

Ergun SJ, Karadeniz ZD, Rivas MF (2024) Climate change risk perception in Europe: Country-level factors and gender differences. Humanities Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1573. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03761-4

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. (2023) Bridging the rural–urban divide: Addressing inequalities and empowering communities. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2806/647715

Fairbrother M (2013) Rich people, poor people, and environmental concern: Evidence across nations and time. Eur Socio Rev 29(5):910–922. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcs068

Falkenberg M, Galeazzi A, Torricelli M, Di Marco N, Larosa F, Sas M, Mekacher A, Pearce W, Zollo F, Quattrociocchi W, Baronchelli A (2022) Growing polarization around climate change on social media. Nat Clim Change 12(12):1114–1121. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01527-x

Ford JD, Zavaleta-cortijo C, Ainembabazi T, Anza-ramirez C, Arotoma-rojas I, Bezerra J, Nuwagira R, Okware S, Osipova M, Pickering K, Singh C, Berrang-ford L, Hyams K, Miranda JJ (2022) Interactions between climate and COVID-19. Lancet Planet Health 6:e825–e833. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00174-7

Franzen A, Vogl D (2013) Two decades of measuring environmental attitudes: A comparative analysis of 33 countries. Glob Environ Change 23(5):1001–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.03.009

Gaikwad N, Genovese F, Tingley D (2022) Creating climate coalitions: Mass preferences for compensating vulnerability in the world’s two largest democracies. Am Political Sci Rev 116(4):1165–1183. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000223

Harris E (2023) Most COVID-19 deaths worldwide were among older people. JAMA 329(9):704. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.1554

Hazlett C, Mildenberger M (2020) Wildfire exposure increases pro-environment voting within democratic but not republican areas. Am Political Sci Rev 114(4):1359–1365. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000441

Huber RA, Wicki ML, Bernauer T (2020) Public support for environmental policy depends on beliefs concerning effectiveness, intrusiveness, and fairness. Environ Politics 29(4):649–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1629171

Hutmacher F, Reichardt R, Appel M (2024) Motivated reasoning about climate change and the influence of Numeracy, Need for Cognition, and the Dark Factor of Personality. Sci Rep. 14(1):5615. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55930-9

Inglehart, R, Haerpfer C, Moreno A, Welzel C, Kizilova K, Diez-Medrano J, Lagos M, Norris P, Ponarin E, Puranen B (eds.). (2022) World Values Survey: All Rounds—Country-Pooled Datafile. [Dataset Version 3.0.0.]. https://doi.org/10.14281/18241.17

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, H. L. (, Katherine Calvin (USA), Dipak Dasgupta (. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate. (2023). Synthesis Report Of The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/

Karlsson R, Lindqvist Jesper (2024) Vänster-högerskalan – det enda som är konstant är förändring, och (o)jämlikhet? Inferno: SOM-rapport. SOM-Inst 83:331–334

Keith McNulty (2024) Handbook of Regression Modeling in People Analytics: With Examples in R, Python and Julia. Proportional Odds Logistic Regression for Ordered Category Outcomes. https://peopleanalytics-regression-book.org/ord-reg.html

Kotz M, Kuik F, Lis E, Nickel C (2024) Global warming and heat extremes to enhance inflationary pressures. Commun Earth Environ 5(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01173-x

Kunda Z (1990) The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol Bull 108(3):480–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

Lee YH, Heo H-H, Noh H, Jang DH, Choi Y-G, Jang WM, Lee JY (2023) The association between the risk perceptions of COVID-19, trust in the government, political ideologies, and socio-demographic factors: A year-long cross-sectional study in South Korea. PLOS ONE 18(6):e0280779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280779

Leviston Z, Walker I, Morwinski S (2013) Your opinion on climate change might not be as common as you think. Nat Clim Change 3(4):334–337. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1743

Lujala P, Lein H, Rød JK (2015) Climate change, natural hazards, and risk perception: The role of proximity and personal experience. Local Environ 20(4):489–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2014.887666

McCright AM, Dunlap RE (2011) The Politicization of Climate Change and Polarization in the American Public’s Views of Global Warming, 2001–2010. Socio Q 52(2):155–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01198.x

McDowell CP, Andrade L, O’Neill E, O’Malley K, O’Dwyer J, Hynds PD (2020) Gender-related differences in flood risk perception and behaviours among private groundwater users in the Republic of Ireland. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062072

McGrath LF, Bernauer T (2017) How strong is public support for unilateral climate policy and what drives it? WIREs Clim Change 8(6):e484. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.484

Meadows AJ, Stephenson N, Madhav NK, Oppenheim B (2023) Historical trends demonstrate a pattern of increasingly frequent and severe spillover events of high-consequence zoonotic viruses. BMJ Glob Health 8(11):e012026. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012026

Mildenberger M, Tingley D (2019) Beliefs about climate beliefs: The importance of second-order opinions for climate politics. Br J Political Sci 49(4):1279–1307. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000321

Ministry of the Environment. Government Offices of Sweden. (2020). Sweden’s long-term strategy for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/LTS1_Sweden.pdf

Mondino E, Di Baldassarre G, Mård J, Ridolfi E, Rusca M (2020) Public perceptions of multiple risks during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy and Sweden. Sci Data 7(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00778-7

OECD (2021) Inequalities in household wealth and financial insecurity of households (OECD Policy Insights on Well-Being, Inclusion and Equal Opportunity 2; OECD Policy Insights on Well-Being, Inclusion and Equal Opportunity, 2). https://doi.org/10.1787/b60226a0-en

Ogunbode CA, Liu Y, Tausch N (2017) The moderating role of political affiliation in the link between flooding experience and preparedness to reduce energy use. Clim Change 145(3):445–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-2089-7

Petrova K, Olafsdottir G, Hegre H, Gilmore EA (2023) The ‘conflict trap’ reduces economic growth in the shared socioeconomic pathways. Environ Res Lett 18(2):024028. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/acb163

Romanello M, Napoli CD, Green C, Kennard H, Lampard P, Scamman D, Walawender M, Ali Z, Ameli N, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Beggs PJ, Belesova K, Berrang Ford L, Bowen K, Cai W, Callaghan M, Campbell-Lendrum D, Chambers J, Cross TJ, Costello A (2023) The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: The imperative for a health-centred response in a world facing irreversible harms. Lancet 402(10419):2346–2394. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01859-7

Ross L, Greene D, House P (1977) The false consensus effect: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. J Exp Soc Psychol 13(3):279–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(77)90049-X

Schneider CR, Dryhurst S, Kerr J, Freeman ALJ, Recchia G, Spiegelhalter D, van der Linden S (2021) COVID-19 risk perception: A longitudinal analysis of its predictors and associations with health protective behaviours in the United Kingdom. J Risk Res 24(3–4):294–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2021.1890637

SEI (2023) Navigating Sweden’s transition toward a low-carbon footprint for all. SEI. https://www.sei.org/perspectives/sweden-low-carbon-footprint/

Smith EK, Bognar MJ, Mayer AP (2024) Polarisation of climate and environmental attitudes in the United States, 1973-2022. Npj Clim Action 3(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-023-00074-1

Stevenson KT, Peterson MN, Bondell HD, Moore SE, Carrier SJ (2014) Overcoming skepticism with education: Interacting influences of worldview and climate change knowledge on perceived climate change risk among adolescents. Clim Change 126(3–4):293–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1228-7

Sullivan GM, Artino AR (2013) Analyzing and interpreting data from likert-type scales. J Graduate Med Educ 5(4):541–542. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-5-4-18

The PoReSo Research Group (2023) Power, resistance and social change. J Polit Power 16(2), 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2023.2251108

Tranter B, Booth K (2015) Scepticism in a changing climate: A cross-national study. Glob Environ Change 33:154–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.05.003

UNDRR (2022) Hazards and Drivers of Urban Risk. http://www.undrr.org/words-action-implementation-guide-land-use-and-urban-planning/hazards-and-drivers-urban-risk

United Nations (2024) What Is Climate Change? https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/what-is-climate-change

Van Daalen KR, Tonne C, Semenza JC, Rocklöv J, Markandya A, Dasandi N, Jankin S, Achebak H, Ballester J, Bechara H, Beck TM, Callaghan MW, Carvalho BM, Chambers J, Pradas MC, Courtenay O, Dasgupta S, Eckelman MJ, Farooq Z, … Lowe R (2024) The 2024 Europe report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Unprecedented warming demands unprecedented action. The Lancet Public Health, S2468266724000550. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(24)00055-0

Van Der Linden S (2015) The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. J Environ Psychol 41:112–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.11.012

Paniello-Castillo, B., Triolo, F., Dryhurst, S., Taylor, O. A., Mazzoleni, M., Khouja, J., Munafò, M., Di Baldassarre, G., & Raffetti, E. (2025). Exploring public risk perception of multiple hazards through network analysis. Cell Reports Sustainability, 100424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsus.2025.100424

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: ER, BPC; analysis and interpretation of results: BPC, ER, SDö, SDr, GDB; draft manuscript preparation: BPC, ER, SDö; supervision: ER. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Italian Research Ethics and Bioethics Committee (Dnr 0043071/2019) and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2019-03242). The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards set by the European Union under Horizon 2020 (EU General Data Protection Regulation and FAIR Data Management).

Informed consent

Participation in the study was entirely voluntary, and all participants (adults over 18 years old) provided informed consent prior to completing the survey in each of its rounds (August 2020, November 2020 and August 2021, see study protocol and data descriptor in (Mondino et al. 2020)). Consent was obtained through an online form embedded at the beginning of each survey, which was distributed via email. The research protocol did not encompass collection of privacy-sensitive and personally identifiable information (PII) data. Since the study was non-interventional (i.e., based on a self-administered online survey), all participants were clearly informed about the anonymity of their responses, and the purpose of the research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paniello-Castillo, B., Döring, S., Dryhurst, S. et al. Risk perception of climate change and global crises: Influences of socio-economic drivers and political orientations. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 967 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05349-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05349-y