Abstract

The climate crisis requires transformational changes to our food systems, which contribute around one third of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. Animal rights activists try to draw attention to this issue through direct action campaigns. However, it remains largely unknown how these disruptive protests affect public opinion. We conducted the first in-depth investigation of the short and long-term effects of a disruptive animal rights protest, Animal Rising’s protest at the UK Grand National horse race. We found that immediately after the protest, respondents’ awareness of the action was linked with more negative attitudes towards animals. However, these negative effects dissipated after six months, suggesting that high-profile disruptive protests trigger short-term emotional reactions that fade over time. Cross-sectional comparisons revealed overall positive shifts in attitudes towards animals over the six-month period. We also found that the protest triggered a sharp increase in media and public attention, as well as mobilization for the protest group. This evaluation suggests that an initial emotional backfire effect of disruptive animal rights protest might be a necessary short-term setback in the general direction of a progressive shift to how society thinks about animals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For decades, climate scientists have been warning that society needs to go through a number of substantial transformations in order to mitigate the most severe impacts of climate change (Masson-Delmotte et al. 2022). Scientists argue that addressing climate change will necessitate altering the food system and the way we eat—in particular the reliance on intensive animal agriculture. Emissions from the livestock sector have been estimated to surpass those of the entire transportation sector (Koneswaran and Nierenberg 2008; Steinfeld et al. 2006). Yet, industrial animal farming is projected to increase globally in the coming decades (Alexandratos and Bruinsma 2012). Reaching the climate targets as defined in the Paris agreement is unlikely without major changes to the food system (Masson-Delmotte et al. 2022). Indeed, shifting towards plant-based diets has been identified as a crucial component in the global efforts to mitigate climate change for multiple reasons: agriculture is responsible for around 30% of global greenhouse gas emissions, 70% of freshwater use, and uses one third of all arable land (Aleksandrowicz et al. 2016). While the production of animal products uses an estimated 83% of the globally available farmland and contributes more than 55% of the food-related emissions, it only provides an estimated 37% of the protein and 18% of the calories people consume (Poore and Nemecek 2018, for further discussions, see Bunge et al. 2024; Kozicka et al. 2023; Scarborough et al. 2023; Springmann et al. 2016). Moreover, plant-based diets would reduce global mortality by an estimated 6–10% primarily due to reduced red meat intake (Springmann et al. 2016). Finally, given decades of research documenting high levels of animal intelligence and sentience (Lifshin 2022; Proctor, 2012), many have criticised how animals are treated in the factory farms that the vast majority of animal products come from.

Many countries have seen growth in the acceptance of plant-based diets in the last few years. For instance, a recent representative UK poll suggests that the number of vegans in the UK has increased by 1.1 million to 2.5 million from 2023 to 2024. However, veganism and vegetarianism are still minority behaviours. An important question following from these considerations is how the necessary shift towards a (more) plant-based diet can be accomplished and accelerated. A growing literature investigates the effects of different messaging campaigns on dietary changes and generally observes that messages around animal welfare, health, and environmental consequences can induce small increases in people’s willingness to reduce meat consumption (Lim et al. 2021; Mathur et al. 2021), with recent evidence showing lasting effects on actual food choices (Jalil et al. 2020, 2023). However, the success of messaging campaigns generally appears to be limited (Mathur et al. 2021) and dependent on how sceptical people are of vegan diets in the first place (Carfora et al. 2019; 111). Some studies report no overall effects (Carfora et al. 2019; Haile et al. 2021). This evidence indicates that well-designed messaging campaigns can be a contributing element but seem unlikely to bring about profound transformations in how people eat.

Such transformations likely require deeper changes in people’s beliefs about the way animals should be treated. Eating habits are deeply ingrained cultural behaviours (Modlinska and Pisula 2018); many people have a strong emotional connection to food and find it hard to forego dishes they grew up with, which often include meat and other animal products (Gradidge et al. 2021; Modlinska and Pisula 2018). Most adults believe that it is acceptable and normal to eat animals and often cite social conventions to support their stance (McGuire et al. 2023). Nearly all adults tested in a recent study considered that eating animal products (not meat) was acceptable, often based on the (erroneous) notion that animals are not harmed in the production of dairy, eggs, and cheese (McGuire et al. 2023).

Animal rights organizations try to change public sentiment and behaviours through a range of methods including public awareness campaigns, consumer education, legislative advocacy, community engagement, and scientific research. Their goal is to make people question society’s relationship with animals, especially those we eat and use for entertainment. One such organization is Animal Rising (AR), an animal rights group calling for a plant-based food system to replace the fishing and farming industries which are responsible for animal cruelty and environmental harm (Anomaly 2015; Blattner 2020; Reisinger et al. 2021). Set up in 2019 as an offshoot of the environmental group Extinction Rebellion (and formerly known as “Animal Rebellion”), AR has attracted significant attention by conducting actions such as blockading abattoirsFootnote 1 and meat factoriesFootnote 2.

The present study focuses on the protest at the Grand National horse race in April 2023, when AR activists went onto the course and caused a delay to the start of the race, triggering substantial media attention. The Grand National (GN) is the UK’s most popular and prestigious horse race. It has been running since 1839, is aired on free-to-view television in the UK and is watched by millions of British and overseas viewers each year. The race is a cultural institution in the UK; for many, it is the only horse race they watch on an annual basis. The race is not without controversy. Compared to other races, it is particularly dangerous. It is a long steeplechase race of over 4 miles and including 30 jumps, some notoriously difficult. Steeplechases in general carry a high mortality rate, with an estimated 6 in 1000 horses dying as a result of racing. Two horses died at the 2023 GN race. Note however, that the goals and motivations for this protest went far beyond the ethics of horse racing per se; AR chose this target to try and encourage people to rethink society’s general relationship with - and treatment of - animalsFootnote 3. AR’s disruption of the GN horse race was featured very prominently on the British news for two days immediately following the protest and the events and the issues raised were widely debated across the country, making it plausible that it caused measurable changes in people’s attitudes towards animals. We investigated short-term (a few days after) as well as long-term (6 months later) effects of the Grand National (GN) protest, assessed how the media respond to major disruptive animal rights protests and investigated how the protests affected direct donations and sign-ups to AR.

There are many historical examples (e.g., civil rights, women’s equality, same sex marriage) where social movements have successfully accelerated change on society’s questionable behaviours (Brehm and Gruhl 2024; Mazumder 2018; Özden and Glover 2022a). Protest campaigns can create a ripple that spreads across society, often challenging long-standing traditions and habits (Chenoweth and Stephan 2011; Shuman et al. 2023; Wasow 2020). Throughout history, civil disobedience has been a powerful catalyst with the ability to enable and accelerate progressive change. However, there remains controversy regarding the effectiveness of disruptive protests.

While some studies suggest positive impacts in the form of a positive radical flank effect (Dasch et al. 2023; Simpson et al. 2022; Ostarek et al. 2024), increased environmental concern (Kenward and Brick 2023), climate concern (Brehm and Gruhl 2024), or willingness to act (Özden and Glover 2022b), other studies find negative public opinion impacts (Feinberg et al. 2020; Menzies et al. 2023). Overall, it is difficult to say how disruptive animal rights protest affects public attitudes towards animal rights/welfare issues. While some studies suggest they cause backlash (that is, a reinforcement of a pre-existing position as a result of exposure to a contrasting argument) as a common consequence (Feinberg et al. 2020), others have found no evidence of backlash (Guess and Coppock 2020). Moreover, a significant shortcoming of previous studies on protest impacts is that they measure only immediate effects. The long-term public opinion impact of disruptive protests remains unclear, as direct evidence on this issue is lacking and evidence on the persistence of attitude changes due to persuasion treatments is very mixed (Coppock 2016; De Vreese 2004; Guess and Coppock 2020; Lecheler and De Vreese 2011; Mutz and Reeves 2005; Tewksbury et al. 2000). Further, studies which only consider public opinion also miss out on important additional paths of impact, such as heightened media attention (Scheuch et al. 2024) and increased mobilisation (Somma and Medel 2019).

Method

Participants

All participants in this study were recruited and paid via the online platform Prolific (https://www.prolific.com/). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were paid for their participation and gave informed consent before commencing the surveys. We used Prolific’s built-in tool to obtain samples that are representative of the UK population for age, sex, and ethnicity (using stratified quota sampling, see https://researcher-help.prolific.com/en/article/95c345) and used raking (see details below) to further ensure the results are nationally representative.

Longitudinal analyses

Wave 1 had a total of 1986 respondents. All respondents were invited to participate in the post-survey. Both surveys included a commitment check and an attention check. Respondents were excluded if they failed either check. 1816 participants completed the survey after the GN protest (wave 2). Due to technical failure, data from 76 respondents could not be used. An additional 83 did not pass the attention (81) and/or commitment (2) checks. A total of 1657 participants could thus be used for analysis, corresponding to a retention rate of 83.4%. To test for possible biases due to differential attrition, we assessed whether those respondents who did not return for wave 2 differed from those who did on any of the main items of interest specified in the Hypothesis section. Regression analyses predicting responses to those items at wave 1 using retention (respondent later returned vs. did not return for wave 2) as the sole predictor variable suggested that the groups were highly similar (all t-values < 1) and thus that there were no issues with differential attrition.

Wave 3 (for the six-month follow-up) had a total of 1356 eligible completes (after again excluding participants who failed the commitment or attention check in any wave), corresponding to a retention rate of 78.8% relative to wave 2 and 68.3% relative to wave 1. Regression analyses again did not indicate robust differences in the key variables between respondents who returned vs. those who did not return. However, there was a weak trend towards people who did not return for wave 3 having higher scores (indicating more favourable views towards animals) on the composite score of interest (t = 1.56) and the item asking how morally acceptable it is to use animals for entertainment (t = 1.62). However, note that all long vs. short-term analyses only used participants who did both waves 2 and 3. The fact that the immediate effects replicate the original effects from our first study very well suggests that attrition did not meaningfully affect the results.

Cross-sectional analyses

We had 2007 respondents in total. After excluding participants who failed either the commitment or attention checks, the sample had 1986 respondents. The sample collected six months after the GN (used as the T2 sample in both cross-sectional analyses) had 1441 eligible respondents.

Data collection

Data collection for wave 1 ran from one week before the Grand National until two days before. Animal Rising made us aware that a major protest would happen on April 15 2023 and provided enough information on its nature to allow us to prepare the survey instrument in time. All surveys were made and all data were collected using Survey Monkey integrated into Prolific. Participants completed the survey on their laptops or phones. Two quality checks were used: 1) Participants were asked if they were committed to filling out a survey accurately and were excluded from data analysis if they indicated “no”. 2) There was an attention check where a short text states that when asked about their favourite sports, participants were supposed to select “Tennis”, or when asked about their favourite drink, they were supposed to select “Carrot juice”. Participants were excluded if they selected any of the other options. Only complete surveys, which were not aborted or were otherwise missing data, were analysed. Sample sizes and stopping rules were decided beforehand and were pre-registered. The full survey can be found in SI 9.

Analysis

To assess the Grand National protest’s short- and long-term impacts on public opinion, we conducted nationally representative polls before, immediately following, and six months after the protest. Our analyses focused on people’s responses to questions about their attitudes towards animals. Our pre-registered study focused on the following questions:

-

(1)

In the past week, how often did you think about issues relating to animal welfare, animal rights or the treatment of animals for food or entertainment? (5-point Likert scale)

-

(2)

To what extent do you disagree or agree with the following statements? (7-point scale, the composite average score of both items was used for analysis)

-

(i)

Society has a broken relationship with animals.

-

(ii)

Society needs to change the way we treat animals used for entertainment.

-

(i)

-

(3)

How morally acceptable or unacceptable do you find the use of animals for entertainment? For example, think of horses used for horse racing. (7-point scale)

The main analyses below focus on these variables, and additional exploratory analyses (which are always marked as such) addressed further questions of interest. The longitudinal analyses below sampled attitudes towards animals over time in the same group of people. They focused on the direct link between awareness of the GN protest or of AR and attitudes towards animals by testing the association between people’s awareness of the GN and their changes in awareness of AR before vs after the protest with changes in the outcome variables of interest. Additional cross-sectional analyses looked at the overall change in people’s attitudes towards animals before and six months after the protest without linking them to the protest. The cross-sectional analyses are simple before vs after comparisons that do not consider how much a participant had heard about the protests. They are useful because repeated surveys with separate nationally representative samples are widely regarded as a gold standard for tracking societal trends, as they allow for robust estimation of changes in group-level averages. They complement the longitudinal analyses which capture within-participant changes required for direct tests of the link between awareness of the GN protests and changes in attitudes towards animals, but which are less suited for simple before vs after tests due to potential measurement reactivity associated with repeatedly surveying the same individuals. Specifically, asking participants to reflect on the same topic multiple times can influence their subsequent responses due to increased salience, social desirability or courtesy effects, as we explored in a follow-up study after wave 2 (see SI 6 for a detailed description).

We also conducted media analyses to assess the protest’s media impact and investigate the link between how different media outlets’ reporting of the protest affects people’s views on AR’s actions. Finally, we conducted mobilisation analyses looking at sign-up numbers and donations to assess the broader impact of the GN protest on momentum in the animal rights movement beyond public opinion.

We used Bayesian regression analysis to test our hypotheses. The package brms (Bürkner 2017) provides an elegant implementation of ordinal regression that we consider the best analysis tool when simple Likert scale responses comprise the outcome variable. This method was used for the simple before vs. after differences, whereas linear Bayesian regressions were used for the difference score analyses described below. For the short vs. longterm longitudinal analyses, we used Bayesian path analysis, as implemented in the R package blavaan (Merkle and Rosseel 2018). It is an elegant solution to simultaneously fit several Bayesian regression models because it captures shared covariance between the different outcome variables. Weights cannot be integrated in this method unfortunately, but note that raking had a small impact in this study to begin with because the samples were quite representative to begin with. We made efforts for our samples to be as nationally representative as possible by 1) using Prolific’s built-in tool to obtain samples that are representative of the UK population for age, sex, and ethnicity using stratified quota sampling (see https://researcher-help.prolific.com/en/article/95c345), and 2) by using raking for the additional variables we collected (voting preference, region, social class) (Pasek and Pasek 2018). This method gives each respondent a weight that reflects how much their demographic profile deviates from the population average. These weights are then used in the statistical analyses and correct for biases due to over or under sampling on any of the demographics; specifically, the models use the weights for each observation’s log-likelihood such that observations with higher weights contribute more to the posterior.

The models that tested hypotheses regarding the effects of AR awareness on the variables of interest used awareness of AR (Q11) as the sole (continuous) predictor variable. More precisely, the difference between each respondent’s awareness of AR after vs. before the Grand National protest was used to predict after vs. before changes in each variable of interest. A complementary analysis tested the effect of awareness of the protests (rather than of AR itself) on the same variables. Awareness of the GN protest was based on wave 2 data only; this question was not asked at T1 since the protests had yet to take place. This second analysis is expected to be more sensitive because it is easier to forget the name of the protest group than to forget the protest itself. At the same time, the first analysis directly relates changes in awareness of AR to changes in the variables of interest. It thus constitutes the most logical and direct test of whether the protest triggered attitudinal changes. Hence, these two analyses are complementary and should both be taken into account regarding conclusions about the effects of the protest.

For the cross-sectional analyses looking at overall differences before vs six months after the GN protest, we used ordinal Bayesian regression analysis with time (before vs six months after) as the sole predictor variable. Again, weights were used to ensure the results can be generalised to the UK population, as described above. One nationally representative sample of respondents did the survey six months after the protest, whereas we had two samples before the protest occurred. We performed the same before vs after analysis twice, using each of the samples collected before the protest in a separate analysis. One can think of this as an internal replication, even though only the pre-sample varied between the analyses, not the post-sample.

For all analyses, we report estimates of the effect of the predictor variables alongside 95% Credible Intervals (CrI), the Bayesian equivalent of 95% Confidence Intervals (Gray et al. 2015). The 95% CrI is the range of values where the true population-level value is expected to fall with a probability of 95%. Generally speaking, effects are considered to be statistically robust if the 95% CrI does not include zero.

We used weakly informative priors for the predictor variables, assuming that any effect sizes would be small (a prior centred around zero with a standard deviation of 0.1 assuming a normal distribution). For the cross-sectional ordinal regression models, we used the cumulative standard normal distribution to derive expected values for the intercepts/thresholds and used a standard deviation of 1.

The data and analysis scripts can be found at this OSF repository.

Results

Short-term impacts: awareness of the protest is linked with negative effects on attitudes towards animals immediately afterwards

We first used data from a nationally representative sample (N = 1657) collected immediately before and after the GN protest to assess short-term impacts on public opinion. This was to try to establish a direct link between people’s knowledge of the protest and potential changes (before vs after) in their attitudes towards animals. We used ordinal and linear Bayesian regression analyses (see the Methods section for details) to test how changes in people’s attitudes towards animals were affected by a) changes in people’s awareness of AR and b) people’s awareness of the GN protestFootnote 4.

Our first analysis looked at how changes in awareness of AR/awareness of the GN protest related to how much respondents said they had thought about animal rights/welfare issues. Both increased awareness of AR (estimate = 0.13, 95% CrI [0.08, 0.18]; Fig. 1A) and awareness of the GN protest (estimate = 0.09, 95% CrI [0.05, 0.14]; Fig. 1D) were associated with increased thoughts about issues relating to animal rights/welfare (relative to before the protest), suggesting that the protest succeeded in drawing attention to this topic. However, both increased awareness of AR (estimate = −0.08, 95% CrI [−0.13, −0.03]; Fig. 1B) and higher awareness of the GN protest (estimate = −0.08, 95% CrI [−0.13, −0.03]; Fig. 1E) were associated with lower values on the main composite score of interest, measuring the extent to which people agreed that society has a broken relationship with animals and needs to change how we use animals for entertainment. Analyses on the individual items making up the composite score found very similar effects (see the Supplementary Information, henceforth “SI” 1).

Top panel: Increased awareness of AR after the GN protest is associated with increased thoughts about animal welfare/rights issues (A), decreased agreement that society has a broken relationship with animals and needs to change how we treat animals used for entertainment (B); was not associated with how morally acceptable people considered using animals for entertainment (C). Bottom panel: Higher awareness of the GN protest is associated with increased thoughts about animal welfare/rights issues (D), decreased agreement that society has a broken relationship with animals and needs to change how we treat animals used for entertainment (E); increased agreement that it is morally acceptable people considered using animals for entertainment (F).

There was no evidence of an association between increased awareness of AR and change in how morally acceptable people found the use of animals for entertainment (estimate = −0.02, 95% CrI [−0.09, 0.05]; Fig. 1C). However, higher awareness of the GN protest was associated with an increase in how morally acceptable people considered the use of animals for entertainment (estimate = 0.08, 95% CrI [0.15, 0.01]; Fig. 1F). Further exploratory analyses (see SI 1) indicated that higher awareness of the GN protest was associated with lower agreement that society needs to change how we use animals for food (estimate = 0.08, 95% CrI [0.15, 0.02]) and with more negative attitudes towards vegans/veganism (estimate = 0.04, 95% CrI [0.08, 0.003]). No effects were seen for additional measures, including support for bans on horse racing and factory farming (see SI 9 for the full list of questions). Our results suggest, therefore, that immediately after the protest, exposure to the GN protest was generally associated with worsened attitudes towards animals.

Long-term impacts: negative attitudes due to the protest do not persist

Next, we assessed the longer-term public opinion impacts by inviting the respondents who completed the initial surveys to a follow-up survey six months later. This allowed us to test whether people who knew more about AR/the GN protest when it happened still showed similar negative attitudes after six months compared to immediately after the protest. We found that the initial negative associations had all disappeared six months after the protest. Figure 2 shows that the variables where attitudes were found to be negatively affected immediately after the protest (the ones where the grey bells are firmly in the negative) had since moved close to zero (the purple bells). The figure displays only effects linked with awareness of the GN because this is where more of the immediate effects were observed, but similar results for changes in awareness of AR can be found in SI 1.

Association between awareness of the GN protest and changes in people’s attitudes towards animals immediately after (grey) and six months after the GN (purple) relative to before the protest. The plot shows the posterior probability densities of the Bayesian regression models. The white dashed line reflects the estimated means. All variables were coded such that negative values indicate less favourable attitudes towards animals.

For all items where there was a robust negative effect, the estimates have shifted towards – and do not differ statistically from – zero. This is particularly striking for the composite score combining the items on whether society has a broken relationship with animals and whether society needs to change the way we use animals for entertainment, where the immediate effect was strong (effect of awareness of the GN: estimate = −0.09, 95% CrI [−0.14, −0.04]; effect of changes in awareness of AR: estimate = −0.12, 95% CrI [−0.17, −0.06]) and then moved very close to zero six months later. This appears to be driven to a large extent by the item asking whether society has a broken relationship with animals (effect of awareness of the GN: immediate effect: estimate = −0.12, 95% CrI [−0.19, −0.05], long-term effect: estimate = −0.02, 95% CrI [−0.09, 0.06]; effect of changes in awareness of AR: immediate effect: estimate = −0.14, 95% CrI [−0.21, −0.07], long-term effect: estimate = −0.08, 95% CrI [−0.15, 0.01]), and to a lesser extent by the second item asking whether society needs to change how we treat animals used for entertainment (effect of awareness of the GN: immediate effect: estimate = −0.06, 95% CrI [−0.14, 0.003], long-term effect: estimate = −0.02, 95% CrI [−0.09, 0.04]; effect of changes in awareness of AR: immediate effect: estimate = −0.09, 95% CrI [−0.17, −0.03]], long-term effect: estimate = −0.03, 95% CrI [−0.4, 0.10]). Overall, the evidence suggests that six months after the protest the extent to which a person was aware of the protest no longer predicts their attitudes towards animals.

The initial negative link between the GN protest and people’s attitudes towards animals thus disappeared. This pattern also holds for the extent to which participants said they had thought about issues relating to animal rights/welfare in the past week (effect of awareness of the GN: immediate effect estimate = 0.13, 95% CrI [0.08, 0.18], long-term effect estimate = 0.03, 95% CrI [−0.03, 0.08]; effect of changes in awareness of AR: immediate effect estimate = 0.19, 95% CrI [0.14, 0.24]], long-term effect estimate = 0.04, 95% CrI [−0.01, 0.09]).

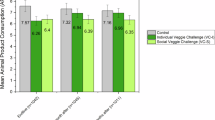

Cross-sectional analysis: attitudes towards animals have improved overall

We also evaluated how attitudes have changed overall, regardless of the extent to which people were aware of the protest. To measure overall changes in attitudes towards animals, we compared the responses of two separate representative groups: one group completed the survey just before the GN protest, and the other completed it six months after. Simple cross-sectional comparisons show that people’s attitudes towards animals have become more positive over this time (see Fig. 3). For several measures the Bayesian analysis indicates substantial support for a positive shift. In particular, people indicated thinking more about animal rights/welfare issues six months after the GN protest (estimate = 0.17, 95% CrI [0.10, 0.23]), people agreed more that society has a broken relationship with animals and needs to change how we treat animals used for entertainment (composite score; estimate = 0.19, 95% CrI [0.11, 0.26]; see the corresponding results on the items making up the composite in Fig. 3), people agreed more that society needs to change how we treat animals used for food (estimate = 0.12, 95% CrI [0.06, 0.19]). Additionally, there was a trend for people considering it more morally unacceptable to use animals for food (estimate = 0.06, 95% CrI [−0.01, 0.13]), and finding it morally more unacceptable to use animals for entertainment (estimate = 0.06, 95% CrI [−0.01, 0.12]), whereas attitudes towards vegans have remained unchanged.

Dots represent the model estimates for the changes in responses before vs. six months after the GN. The thin and thick lines show the 95 and 66% CrIs, respectively, overlaid with the posterior probability densities of the estimates. The black vertical dashed line shows the zero-line reflecting no difference before vs. after. Positive numbers indicate more favourable attitudes six months after compared to before the GN protest.

To give a sense of the magnitude of the changes, we used the Bayesian model fits to recover and plot estimated mean Likert scores (see Fig. 4). The largest changes were just below 0.2 points on the Likert scale, which (for an intuitive approximation) one can think of as one in five people six months after the protest choosing an answer that is one level more favourable than before the protest, for example “strongly agree” over “agree”, or “somewhat agree” over “neither disagree nor agree”Footnote 5. Whether one considers these changes large or small in the grand scheme of things, they are very consistent, pointing towards reliable improvements in people’s attitudes towards animals in the UK, although without corresponding changes in attitudes toward veganism/vegans.

In addition to the main variables of interest, which reflect people’s general attitudes towards animals, we also assessed people’s support for four kinds of bans: a ban on horse racing, on animal testing, on factory farming and on all animal farming (see Fig. 5). Only the ban on animal testing was suggestive of a positive impact, but the CrI slightly overlapped with zero (estimate = 0.06, 95% CrI [−0.002, 0.13]).

All the cross-sectional analyses were confirmed with an additional nationally representative sample that was collected before the protest, which was compared to the same sample collected six months later. Results (see SI 9) replicate all the cross-sectional findings above, suggesting that the overall changes we describe are very robust.

Media analysis: the Grand National protest enhanced media attention which had a positive effect on mobilization

We conducted a media analysis with LexisNexis (https://www.lexisnexis.com/en-us/gateway.page) looking at the frequency with which “Animal Rising” was mentioned in news articles in national and international newspapers in April 2023, when the protest occurred (see Fig. 6). AR had no (or very few) mentions before the protest, but numbers rose to hundreds per day when the protest occurred. In April 2024, AR spokespeople were invited to 61 TV interviews, seen by millions of people; by contrast, in January to March, they did a total of 9 interviews.

Previous research has highlighted how media narratives can greatly influence public opinion (McLeod and Detenber, 1999; Shanahan et al. 2011). For instance, work on attitudinal responses to Civil Rights protests indicates that news articles with a legitimising debate framing lead to greater support for and identification with the protestors (Brown and Mourão 2021). We evaluated whether there is a similar pattern in the present data. At wave 2, respondents were asked about which news media outlet they heard about the GN protest from and how that news outlet viewed the protests (Likert scale 1–7 from “strongly condemned” to “strongly praised”). They were also asked the extent to which they support or oppose the protestors’ actions (Likert scale 1–7 from “strongly oppose” to “strongly support”).

First, we investigated whether different news outlets were associated with different levels of support for AR in a regression model with the BBC (generally considered relatively neutral) as the reference level (see Fig. 7). Relative to the BBC, hearing about the protest on ITV was associated with lower levels of support (estimate = −0.43, 95% CrI [−0.69, −0.18]), whereas hearing about it via social media (estimate = 0.3, 95% CrI [0.02, 0.57]), The Guardian (estimate = 0.55, 95% CrI [0.16, 0.96]), and family or friends (estimate = 0.84, 95% CrI [0.37, 1.31]) was associated with higher levels of support (see SI 4 for a regression table showing the effects of demographic variables that may plausibly influence responses).

Dots represent the model estimates for each contrast. The thin and thick lines show the 95 and 66% CrIs, respectively, overlaid with the posterior probability densities of the estimates, some of which are very wide due to small sample sizes for some outlets (see the embedded table). The BBC was used as the reference level for the news media outlets factor, i.e., the estimates for the remaining outlets show the differential effect on support for AR compared to hearing about the protest on the BBC. The model controls for a number of control variables (see SI 4) to better isolate the effect that news outlets have.

To investigate this further, we ran a Bayesian regression analysis linking how favourably respondents rated the news outlet’s reporting of the protest to support AR. It indicated that the more positive the outlet’s view of the protest, the more supportive respondents were of AR’s actions (see Fig. 8). It is likely that people’s choice of media is related to their political leanings and beliefs, which in turn might play a role in their pre-existing attitudes towards animals and animal activists. Therefore, we included a number of demographic variables (age, gender, education, voting intention), as well as people’s responses to key questions at wave 1 to capture pertinent pre-existing attitudes towards animals (society has a broken relationship with animals, society needs to change the way we treat animals used for entertainment/food, how morally acceptable it is to use animals for entertainment). Even though these additional factors explained much of the variance (see the regression table in SI 5), the relationship between media views and support for AR remained stable, pointing towards an independent effect of media portrayal.

“Neither condemned nor praised” was used as the reference level for the media views factor, i.e., the estimates for the remaining factor levels show the differential effects on support for AR relative to that reference level. Note that no participant selected “Strongly condemned”; hence this level does not appear in the plot. Dots represent the model estimates for each contrast. The thin and thick lines show the 95 and 66% CrIs, respectively, overlaid with the posterior probability densities of the estimates.

Mobilisation analysis: The Grand National protest increased donations and sign-ups

Animal Rising saw a sharp increase in direct donations when the GN protest happened. Figure 9 below shows the z-scored daily donations per year (excluding one day with a very large one-off donation). The donations for the day of the protest were 8.1 standard deviations from the mean, and the four days immediately following it were all among the highest of the entire year (up until 9 August, the last day for which we had donations data available). There was also a sharp increase in sign-ups to take action with AR, peaking at 5.3 standard deviations from the mean. Interestingly, the timeline of sign-ups was quite different to that of direct donations, with many signing up when AR’s plans for the GN were leaked in a headline report by the Mail on Sunday and a second spike just before the protest.

Discussion

Immediately after the protest, the effects of knowledge of the GN protest on public opinion were largely negative: the more somebody had heard about the GN protest, the more their attitudes towards animals tended to worsen from before to after the protest on several key measures. This is in line with previous experimental results suggesting that radical animal rights protest can decrease support for the protestors and their goals (Feinberg et al. 2020). Another recent experimental study further observed more negative attitudes towards vegans after reading animal rights protests, mediated by the degree to which people considered the activists immoral and hence struggled to identify with them (Menzies et al. 2023).

However, no negative effects associated with awareness of the GN protest were seen six months later. Our results suggest that the negative effects weakened and almost disappeared. This indicates that a high-profile disruptive protest, such as the GN protest, triggers a strong emotional reaction that alters how people think about the issues it raises for a short while. After some time has passed, the direct impact of having seen or heard about the protest no longer has a measurable effect on people’s attitudes towards animals. Previous work on the longevity of attitude changes is mixed and suggests that some effects measured immediately after a treatment disappear completely within weeks (De Vreese 2004; Mutz and Reeves, 2005), whereas others persist, albeit at reduced size (Lecheler and De Vreese 2011; Tewksbury et al. 2000). Coppock (2016) argued that framing treatments that do not provide new information but rather highlight certain aspects of an issue are more fleeting, whereas treatments that provide new information are more persistent. It is possible that disruptive animal protests temporarily alter how salient certain aspects of people’s attitudes towards animals are but do not change the information people have and therefore leave their general beliefs about animals untouched in the long run. However, previous work typically did not carry outfollow-ups further than one month after the intervention, making comparisons difficult and highlighting the need for more studies investigating long-term effects of natural and experimental treatment effects.

Simple cross-sectional comparisons of separate nationally representative samples indicated overall positive shifts in people’s attitudes towards animals over the period of six months following the GN protest. This could plausibly be due to secondary effects of the GN protest, which garnered substantial media attention and sparked a debate on animal welfare and rights. Thus, even though long-term effects were not found to be directly linked to a person’s knowledge of the protests, the ripple effects they created via the large media response they triggered may have caused people to become more sympathetic towards animal rights/welfare issues. However, it has to be noted that while consistent with such an interpretation, the cross-sectional long-term data do not constitute causal evidence. This is due to the nature of such data, which provide a simple before vs after comparison and more specifically because the positive shift could be due to other animal welfare campaigns taking place in a similar time frameFootnote 6 or other factors unknown to us. Thus, the cross-sectional results, whilst providing important contextual information on people’s changes in their attitudes towards animals before vs six months after the GN protest, should only be viewed as a tentative and complementary bit of evidence regarding the central question of the overall impacts of the GN protest. The view that the positive overall shift is at least partly due to AR’s protest activities is supported by media analyses showing heightened attention on animal rights issues and by the mobilisation analyses indicating that the protest enhanced momentum to act for people who were already sympathetic to the cause. Future work could investigate whether the positive trend reported here continues and attempt to relate it to AR’s and other groups’ activities going forward.

Finally, the GN protest received substantial media attention and different media outlets and the favourability of the news articles affected people’s views towards AR, highlighting the powerful position mass media hold in shaping public opinion. The media analyses are compatible with previous studies suggesting that the way newspapers write about protests strongly influences how their readers think about the activists and the issues they fight for (Brown and Mourão 2021; McLeod and Detenber 1999; Shanahan et al. 2011). The GN protest received large-scale media coverage that, due to its disruptive nature, was predominantly negative (Scheuch et al. 2024), which likely contributed to the negative effects the protest exerted in the short-term.

Our results also suggest that some aspects of people’s attitudes towards animals appear more malleable than others. For example, people’s agreement with the view that society has a broken relationship with animals appeared quite changeable. By contrast, support for bans (on horse racing, factory farming, animal testing, and all farming) was not linked with awareness of the protest and only changed very little before to six months after the protest. Whereas to some extent, especially regarding the item asking whether society has a broken relationship with animals, this could simply be explained by the wording of certain items being more open to personal interpretations, we propose that this seems to reflect a general pattern whereby people are more likely to shift towards pro-animal beliefs not connected with concrete changes or connected with small incremental improvements. In line with this view, six months after the GN protest people agreed more that society needs to change how we treat animals used for entertainment and food. However, there was only a weak trend towards people finding it less morally acceptable to use animals for entertainment and food. While people tend to think we should improve how we treat animals, they are more reluctant to say that using animals for entertainment and food is wrong. So, while it appears achievable for animal activists to shift people’s views to become more favourable towards animals, it remains a significant challenge to convince people of fundamental changes needed for society to shift away from using animals for food and entertainment.

Our findings have important implications for the broader animal advocacy movement. For activists, they indicate that initially negative reactions to disruptive protests, often highlighted by media outlets, do not translate to lasting backfire effects which could hinder progress on the issue. At the same time, six months after the protest there is no evidence of the initially negative effects turning into positive ones. For researchers, this highlights the need not only to measure immediate effects but also to track them over time. Typical vignette designs, where the outcome variables are collected moments after participants are exposed to descriptions of protest activities (Bugden 2020; Dasch et al. 2023; Feinberg et al. 2020; Simpson et al. 2022), or observational studies looking at effects immediately after a protest (Brehm and Gruhl, 2024; Kenward and Brick 2023) may pick up fleeting emotional effects that alter how people respond in the moment, but that might not be a good proxy for true attitudinal changes. Future work could usefully address just how long/short-lived such initial negative effects are.

While this study capitalized on a unique opportunity to capture the effects of one of the most discussed animal rights protests in recent history in the UK, it also has some limitations that should be noted. First, we examined the effects of just one particular direct action; additional data are required to determine the extent to which the present findings generalize to different protest tactics and contexts. Second, the large gap between the second and third wave (six months) makes it impossible for us to determine how long it took for the initially observed negative effects to dissipate. Future studies manipulating the time delay between a protest (or experimental intervention) and follow-up data collection should examine the longevity of initial backlash effects, as campaigners could use this information to prevent backlash from accumulating. Third, the nature of the cross-sectional analyses prevents us from determining whether and to what extent the positive shift in attitudes towards animals were due to AR’s protest. It would be interesting to evaluate over longer periods of time whether public attitudes towards animals are influenced by protest activities, or whether they might simply trend upward over time.

In conclusion, in the first in-depth analysis of the effects of disruptive animal rights protest we find immediate backlash effects as a function of the extent to which a person was exposed to the protest, which dissipated within six months. At the same time, the protest drew substantial media attention, enhanced mobilisation, and we saw overall improvements in people’s attitudes towards animals. Thus, this initial evidence suggests that animal rights activists may have an important role to play in provoking the social change required to move away from animal farming, arguably a necessary step in the global efforts to tackle the climate crisis and shift towards a more sustainable future.

Data availability

All data necessary to reproduce the results presented in the paper are publicly available on this OSF repository.

Notes

The second measure is useful because some people might have been aware of the protest without having heard (or remembered) the name “Animal Rising”. The first measure is useful for a more technical reason: awareness of AR could be assessed before and after the protest, hence allowing us to calculate a change score.

A similar interpretation regarding the practical significance of the effects also holds for the longitudinal analyses above.

The most notable campaigns were also carried out by AR, but none came close to the GN in the mediatic and public attention they triggered.

References

Aleksandrowicz L, Green R, Joy EJ, Smith P, Haines A (2016) The impacts of dietary change on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and health: A systematic review. PloS One 11(11):e0165797, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0165797&emulatemode=2

Alexandratos N, Bruinsma J (2012) World agriculture towards 2030/2050: The 2012 revision. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/288998/

Anomaly J (2015) What’s wrong with factory farming? Public Health Ethics 8(3):246–254

Blattner C (2020) Just transition for agriculture? A critical step in tackling climate change. J Agriculture, Food Syst, Community Dev 9(3):53–58

Brehm J, Gruhl H (2024) Increase in concerns about climate change following climate strikes and civil disobedience in Germany. Nat Commun 15(1):2916, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-46477-4

Brown DK, Mourão RR (2021) Protest coverage matters: How media framing and visual communication affects support for Black civil rights protests. Mass Commun Soc 24(4):576–596

Bugden D (2020) Does climate protest work? Partisanship, protest, and sentiment pools. Socius 6:2378023120925949

Bürkner PC(2017) brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan J Stat Softw 80:1–28

Bunge AC, Mazac R, Clark M, Wood A, Gordon L (2024) Sustainability benefits of transitioning from current diets to plant-based alternatives or whole-food diets in Sweden. Nat Commun 15(1):951, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-45328-6

Carfora V, Catellani P, Caso D, Conner M (2019) How to reduce red and processed meat consumption by daily text messages targeting environment or health benefits. J Environ Psychol 65:101319, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272494418304596?casa_token=ELcO86jV5GwAAAAA:qdxuKV3DGs5u4lel6TbqBsF6Xy6fQ3KZ3olHta6c2mE6VrajfmRzZJOME7KbpNsUfS5cHIap

Chenoweth E, Stephan MJ (2011) Why civil resistance works: The strategic logic of nonviolent conflict. Columbia University Press. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=kGW8cops3GcC&oi=fnd&pg=PA87&dq=Why+civil+resistance+works:+The+strategic+logic+of+nonviolent+conflict&ots=5r0-z0IYPf&sig=pThWlXJnNeE0BgvWULBcJlD77x0

Coppock A (2016) The persistence of survey experimental treatment effects. Unpublished Manuscript. https://alexandercoppock.com/coppock_2017b.pdf

Dasch S, Bellm M, Shuman E, van Zomeren M (2023) The Radical Flank: Curse or Blessing of a Social Movement? Glob Environ Psychol https://www.psycharchives.org/en/item/7cf21891-1dd0-4c98-9bf2-faf9142dca42

De Vreese C (2004) The Effects of Strategic News on Political Cynicism, Issue Evaluations, and Policy Support: A Two-Wave Experiment. Mass Commun Soc 7(2):191–214. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327825mcs0702_4

Feinberg M, Willer R, Kovacheff C (2020) The activist’s dilemma: Extreme protest actions reduce popular support for social movements. J Personal Soc Psychol 119(5):1086

Gradidge S, Zawisza M, Harvey AJ, McDermott DT (2021) A structured literature review of the meat paradox. Soc Psychological Bull 16(3):1–26

Gray K, Hampton B, Silveti-Falls T, McConnell A, Bausell C (2015) Comparison of Bayesian credible intervals to frequentist confidence intervals. J Mod Appl Stat Methods 14(1):8

Guess A, Coppock A (2020) Does counter-attitudinal information cause backlash? Results from three large survey experiments. Br J Political Sci 50(4):1497–1515

Haile M, Jalil A, Tasoff J, Vargas Bustamante A (2021) Changing Hearts and Plates: The Effect of Animal-Advocacy Pamphlets on Meat Consumption. Front Psychol 12:668674. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.668674

Jalil AJ, Tasoff J, Bustamante AV (2020) Eating to save the planet: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial using individual-level food purchase data. Food Policy 95:101950, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919220301548?casa_token=NjinhosPWYoAAAAA:frkXB6TCG21MPzFVzVLBxHWvi9CjKZtsZ9jsrfq_cKW3xA-SxwXMQqyVrqn6jHwzexWQ59VC

Jalil AJ, Tasoff J, Bustamante AV (2023) Low-cost climate-change informational intervention reduces meat consumption among students for 3 years. Nat Food 4(3):218–222. https://idp.nature.com/authorize/casa?redirect_uri=https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-023-00712-1&casa_token=lSuwSujjq8QAAAAA:YUYvHVBzZDKCsBlf9hfs2pnwDr3KFTgN5PtAv3P-Arf8DJ8mFrSb31Axljua3yPGW3dRtiPmjpMT4ro

Kenward B, Brick C (2023) Large-scale disruptive activism strengthened environmental attitudes in the United Kingdom

Koneswaran G, Nierenberg D (2008) Global Farm Animal Production and Global Warming: Impacting and Mitigating Climate Change. Environ Health Perspect 116(5):578–582. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.11034

Kozicka M, Havlík P, Valin H, Wollenberg E, Deppermann A, Leclère D, Lauri P, Moses R, Boere E, Frank S (2023) Feeding climate and biodiversity goals with novel plant-based meat and milk alternatives. Nat Commun 14(1):5316, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-40899-2

Lecheler S, De Vreese CH (2011) Getting real: The duration of framing effects. J Commun 61(5):959–983. https://academic.oup.com/joc/article-abstract/61/5/959/4098493

Lifshin U (2022) Motivated science: What humans gain from denying animal sentience. Anim Sentience 6(31):19

Lim TJ, Okine RN, Kershaw JC (2021) Health-or environment-focused text messages as a potential strategy to increase plant-based eating among young adults: An exploratory study. Foods 10(12):3147, https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/10/12/3147

Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pörtner H-O, Roberts D, Skea J, Shukla PR (2022) Global Warming of 1.5 C: IPCC special report on impacts of global warming of 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels in context of strengthening response to climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Cambridge University Press. https://dlib.hust.edu.vn/handle/HUST/21737

Mathur MB, Peacock J, Reichling DB, Nadler J, Bain PA, Gardner CD, Robinson TN (2021) Interventions to reduce meat consumption by appealing to animal welfare: Meta-analysis and evidence-based recommendations. Appetite 164:105277, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666321001847

Mazumder S (2018) The persistent effect of US civil rights protests on political attitudes. Am J Political Sci 62(4):922–935

McGuire L, Fry E, Palmer S, Faber NS (2023) Age‐related differences in reasoning about the acceptability of eating animals. Soc Dev 32(2):690–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12655

McLeod DM, Detenber BH (1999) Framing effects of television news coverage of social protest. J Commun 49(3):3–23

Menzies RE, Ruby MB, Dar-Nimrod I (2023) The vegan dilemma: Do peaceful protests worsen attitudes to veganism? Appetite 186:106555

Merkle EC, Rosseel Y (2018) blavaan: Bayesian structural equation models via parameter expansion. J Stat Softw 85:1–30

Modlinska K, Pisula W (2018) Selected psychological aspects of meat consumption—A short review. Nutrients 10(9):1301, https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/10/9/1301

Mutz DC, Reeves B (2005) The new videomalaise: Effects of televised incivility on political trust. Am Political Sci Rev 99(1):1–15. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/new-videomalaise-effects-of-televised-incivility-on-political-trust/093762E57EF0CFA2E4A0328572DE0009

Ostarek M, Simpson B, Rogers C, Özden J (2024) Radical climate protests linked to increases in public support for moderate organizations. Nat Sustain 7:1626–1632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01444-1

Özden J, Glover S (2022a) Protest movements: How effective are they. Social Change Lab. Retrieved January, 7, 2023

Özden J, Glover S (2022b) Disruptive climate protests in the UK didn’t lead to a loss of public support for climate policies. Social Change Lab

Pasek J, Pasek M J (2018) Package ‘anesrake’. The comprehensive R archive network, 1-13

Poore J, Nemecek T (2018) Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 360(6392):987–992. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0216

Proctor H (2012) Animal sentience: Where are we and where are we heading? Animals 2(4):628–639

Reisinger A, Clark H, Cowie AL, Emmet-Booth J, Gonzalez Fischer C, Herrero M, Howden M, Leahy S (2021) How necessary and feasible are reductions of methane emissions from livestock to support stringent temperature goals? Philos Trans R Soc A 379(2210):20200452

Scarborough P, Clark M, Cobiac L, Papier K, Knuppel A, Lynch J, Harrington R, Key T, Springmann M (2023) Vegans, vegetarians, fish-eaters and meat-eaters in the UK show discrepant environmental impacts. Nat Food 4(7):565–574. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-023-00795-w

Scheuch EG, Ortiz M, Shreedhar G, Thomas-Walters L (2024) The power of protest in the media: Examining portrayals of climate activism in UK news. Humanities Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–12. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-024-02688-0

Shanahan EA, McBeth MK, Hathaway PL (2011) Narrative policy framework: The influence of media policy narratives on public opinion. Politics Policy 39(3):373–400

Shuman E, Goldenberg A, Saguy T, Halperin E, van Zomeren M (2023) When Are Social Protests Effective? Trend Cogn Sci. https://www.cell.com/trends/cognitive-sciences/fulltext/S1364-6613(23)00261-9?dgcid=raven_jbs_aip_email

Simpson B, Willer R, Feinberg M (2022) Radical flanks of social movements can increase support for moderate factions. PNAS Nexus 1(3):pgac110

Somma NM, Medel RM (2019) What makes a big demonstration? Exploring the impact of mobilization strategies on the size of demonstrations. Soc Mov Stud 18(2):233–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1532285

Springmann M, Godfray HCJ, Rayner M, Scarborough P (2016) Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113(15):4146–4151. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523119113

Steinfeld H, Gerber P, Wassenaar TD, Castel V, De Haan C (2006) Livestock’s long shadow: Environmental issues and options. Food & Agriculture Org. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=1B9LQQkm_qMC&oi=fnd&pg=PR16&dq=steinfeld+environmental+issues&ots=LQVZeWaPuE&sig=lGEkp-NbKgYVBBH14hl6yub7tG4

Tewksbury D, Jones J, Peske MW, Raymond A, Vig W (2000) The Interaction of News and Advocate Frames: Manipulating Audience Perceptions of a Local Public Policy Issue. Journalism Mass Commun Q 77(4):804–829. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900007700406

Wasow O (2020) Agenda Seeding: How 1960s Black Protests Moved Elites, Public Opinion and Voting. Am Political Sci Rev 114(3):638–659. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305542000009X

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ben Kenward for useful feedback on the pre-registration and analysis plans for the long vs short-term comparisons.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Markus Ostarek: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. James Özden: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. Cathy Rogers: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Lennart Klein: Visualization, Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests but would like to mention the following for transparency: Two of the authors were in touch with Animal Rising a month before the Grand National protest and received information that a major animal rights protest was planned for mid-April, allowing Social Change Lab to prepare the survey instrument and set up data collection. None of the authors were involved in (or advised on the plans for) the Grand National protest and communications only served the academic purpose of having sufficient information to carry out the research well.

Ethical approval

All research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was not required for this study, as it involved secondary analysis of fully anonymized, publicly available data originally collected by the non-profit Social Change Lab for reports published in 2023 and 2024 (see this OSF repository).

Informed consent

Before beginning the surveys, all participants were informed what the survey entailed, that their data would remain anonymous, and gave digital consent to participate in the study and for the data to be used for research and publications.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ostarek, M., Klein, L., Rogers, C. et al. Short and long-term effects of disruptive animal rights protest. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1110 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05365-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05365-y

This article is cited by

-

The Activist’s Trade-Off: Climate Disruption Buys Salience at a Cost

Political Behavior (2025)