Abstract

Governments worldwide announced regional integration stimulus packages to stimulate economic growth, offering a unique opportunity to address issues related to resource and environmental carrying capacity (RECC). China’s efforts to enhance RECC within the strategy content of regional integration provided valuable insights for global strategies. Taking the Yangtze River Economic Belt (YREB) as an example, this study developed a theoretical framework and employed a double differences (DID) model, alongside a mediation effect technology, for excavating the policy outcomes and specific mechanisms of which regional integration influenced RECC. Additionally, we conceptualized RECC improvement as a collective shift in behavior, shaped by a combination of capacity, motivation, and policy instrument choices, employing fsQCA. The findings revealed that the regional integration policies in urban agglomeration zones had a significant beneficial impact on RECC, increasing it by approximately 0.016 units. This investigation presents a comprehensive approach for enhancing regional integration policy effectiveness, aimed at improving RECC. We underscored the necessity of unblocking the intermediary mechanisms including economic linkage, industrial restructuring, and technological advancements through which regional integration policies impact RECC. Furthermore, the study highlights the importance of tailored policy instrument mixes, anchored in the local economic realities, administrative capacities, and regional variations, rather than relying on the uniform application of supply, demand, and environmental policy actions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the late 19th century, global market expansion has strengthened international linkages and intensified competition (Petricevic and Teece, 2019; Mongo et al., 2021). In response, countries increasingly turned to regional cooperation to promote stable development, making regional integration a global trend (Khoshnava et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2024). However, rising protectionism and de-globalization have challenged these efforts, introducing new uncertainties (Liu et al., 2020). In this context, internal regional integration has gained importance by facilitating resource flows and supporting stable growth. The integrated pattern, based on geographic proximity and economic similarity, became dominant (Fang and Yu, 2017). China widely adopted this model to overcome spatial constraints and enhance regional competitiveness, especially in urban clusters (Guo et al., 2025). Such integration, characterized by the “Space of networks,” has improved land and energy efficiency through agglomeration economies, allowing cities to grow without proportionally increasing land and environmental costs, thereby enhancing resource and environmental carrying capacity (RECC).

In response to growing concerns over RECC, various countries have implemented targeted measures. For instance, Mexico City launched the Green Plan in 2007, and the European Commission proposed a technology application agenda in 2010 (Caragliu et al., 2011). In China, several national strategies have aimed to strengthen RECC. The State Council emphasized technological innovation and industrial upgrading to ease urban pressures in 2017. The 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020) called for optimizing urban agglomeration scales, while the 14th Five-Year Plan further advanced urban cluster development to enhance carrying capacity. Supporting policies included promoting new urbanization, industrial concentration, equal access to public services, and technological progress. At the local level, cities and clusters adopted policy instruments such as financial incentives, infrastructure investment, and institutional coordination to promote RECC.

Despite active policy efforts, their effectiveness has often been weakened by poor coordination among policy instruments during implementation. In China, regional integration has at times resulted in unintended outcomes, such as the continued expansion of urban and industrial areas (Feiock, 2013; Ma et al., 2024), leading to ecological land loss, resource overuse, traffic congestion, and pollution (Ewing et al., 2014, 2016; Mun et al., 2024). For example, in 2020, the Yangtze River Economic Belt (YREB), while accounting for 21% of China’s land, consumed 57% of national energy and contributed 60% of carbon emissions. Over 400 cities nationwide also faced severe water shortages. Urban agglomerations, as the main engines of integration, saw electricity demand rise by 12% annually over the past decade. PM2.5 levels exceeded safe thresholds by 11.4% in many cities. These phenomenon suggest RECC is approaching a critical tipping point. Notably, similar challenges are present in other countries as well (Niu et al., 2023), making the optimization of regional integration policy for RECC enhancement an urgent global concern.

Addressing the growing tension between high-speed regional development and ecological sustainability, this study investigates how regional integration policies influence the RECC of urban agglomerations. While prior research has examined individual policy effects on RECC indicators, few have systematically explored the mechanisms and policy configurations through which integration policies shape RECC outcomes across diverse urban contexts.

To bridge this gap, we construct a comprehensive analytical framework that links regional integration, influence mechanisms, and policy instruments. We empirically test this framework using panel data from 117 cities in the YREB, applying a quasi-natural experiment design. This study aims to address the following research questions: (1) How do regional integration policies affect the RECC of urban agglomerations? (2) Through which mechanisms, particularly economic linkage, industrial restructuring, and technological progress, do these policies influence RECC? (3)Which combinations of policy instruments are most effective for improving RECC in cities with different economic and administrative profiles?

To answer these questions, we adopt a multi-method approach. A Difference-in-Differences (DID) model and its extended forms are used to assess the net policy effects and mediating pathways, improving causal identification beyond conventional regressions. Further, a dynamic fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) is employed to identify effective policy tool configurations under varying local conditions. Together, these methods provide robust, policy-relevant insights for enhancing the environmental sustainability of regional integration strategies.

Literature review and theoretical framework

Literature review

Research on RECC evolved from foundational studies on resource carrying capacity and environmental carrying capacity (Feng et al., 2018). Earlier studies predominantly focused on defining RECC, developing measurement indicators, identifying influencing factors, and exploring pathways for its improvement. Despite variations in definitions, most scholars concurred that RECC refers to the demographic and economic levels that the resources and environmental capacity of a region can uphold without causing ecological damage (Ren et al., 2016; Souza et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2019). For example, Zhou et al. (2021) defined RECC as “the maximum population size and economic total that that could be accommodated by the resource stock and environmental limits of a given region under sustainable development conditions”. The literature review revealed that many studies concentrated on specific resources and environmental elements, such as air quality, water resources, land, and minerals (Martire et al., 2015; Sharma and Jain, 2024; Yang et al., 2019; Zhang and Zhu, 2022). Using approaches like the ecological zoning method, the DPSIR model, GIS-integrated decision-making systems, and coupling simulated annealing-projection pursuit models, some scholars developed evaluation systems with multiple dimensions for quantitative RECC measurement (Castellani et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2018; Martire et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2022; Solarin et al., 2019).

In recent years, most scholars have comprehensively measured RECC using a multi-index comprehensive evaluation method. Accordingly, various RECC measurement indicator frameworks were developed, such as “Resource, Environment, and Socioeconomic”, “Resources, Economy, Environment, and Development” (Zhang et al., 2024), “Land resources, Water resources, Environment, and ecology” (Wang and Liu, 2019), “Pressure, State, and Response” and its extensive(Fan et al., 2023), as well as “Pressure, Support, and State (Anamaghi et al., 2023). Despite numerous empirical RECC studies have been performed at varying spatial extents, including provinces, cities, urban agglomeration areas, and watersheds (Bao et al., 2022; Gao et al., 2021; Gao et al., 2011), RECC evaluation studies across multiple urban agglomeration scales remain scarce.

In terms of influencing factors, existing studies have explored what affects RECC using various methods such as linear regression (Zhang et al., 2024), spatial econometric models (Wang and Hu, 2020), coupling degree models (Wang et al., 2024), and system dynamics technology(Mutingi et al., 2017). Findings suggest that RECC is influenced by both internal factors within resource and environmental systems and external economic and social factors, including the economy, industry, innovation, and policies (Westing, 1989; Esfandi and Nourian, 2021; Cheng et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2024). For instance, some scholars have highlighted that economic growth is a primary element affecting RECC, with the relationship between resource and environmental conditions and economic activity moving from beneficial to detrimental (Zhang et al., 2009). At the industrial level, strategies such as adjusting industrial structure, enhancing industrial hierarchy, and optimizing industrial layout are crucial for improving urban RECC (Zhang et al., 2024). Additionally, technological innovation is a significant driver of RECC enhancement, offering robust support through spatial spillover effects such as knowledge diffusion and the flow of innovative elements (Wang et al., 2023). Furthermore, regional development policies have been critical in influencing RECC (Shen et al., 2022). For example, policies such as land control, regional coordinated development (Chen et al., 2024), low carbon policy(Zhu and Jiang, 2024), and ecological policies have had notable impacts on RECC (Meijers and Burger, 2017). Simultaneously, policy contexts such as regional integration or urban agglomeration development provide new perspectives for enhancing RECC, garnering widespread attention from scholars (Carey, 1993; Chen et al., 2023; Wang and Li, 2020).

In general, while previous studies have established a solid theoretical foundation and provided various empirical observations about the interplay between regional integration and RECC, several significant limitations persist. First, few studies have explicitly investigated the direct linkage between regional integration and RECC. A clear shortage of studies delves deeply into the mechanisms and characteristics by which regional integration policies affect RECC. While academics explored the outcomes of regional planning initiatives or policies on RECC, these studies predominantly focus on the resource-carrying potential of water and land, through mechanisms like government collaboration, industrial agglomeration, and urbanization following policy implementation (Mao et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2022). Additionally, A variety of past research efforts have integrated the effects of various socioeconomic factors into econometric regression models analyzing regional integration policy variables (Mohsin and Jamaani, 2023; Tenaw and Beyene, 2021; Wang et al., 2024). These approaches often introduce endogenous issues, thereby biasing the exploration of the policy effect and influence pathway of regional integration on RECC. Moreover, regional integration policies are often implemented across multiple dimensions simultaneously or in rapid succession by government departments. This overlapping implementation makes it difficult to identify which specific policy instrument mixes are most effective for enhancing RECC in different regions. Addressing these gaps is crucial for advancing RECC and developing more targeted and efficient regional integration policies.

Theoretical framework

The influence mechanism that regional integration has on RECC

Regional integration influences the RECC of cities through three main pathways: economic linkage, industrial restructuring, and technological advancement.

Economic linkage reconfigures regional production and resource flows. Stronger economic connectivity promotes more efficient allocation via market integration, infrastructure improvement, and factor mobility (Westing, 1989). Yet few studies unify regional integration, economic linkage, and RECC within a single framework. Infrastructure improvements, such as in transport and communications, facilitate cross-city synergies (Wang et al., 2023), while reduced trade frictions enhance capital, technology, and labor circulation (Reddy et al., 2022). Economic ties also support institutional collaboration (Li et al., 2024), enabling regulatory alignment and joint ecological governance (Apergis and Payne, 2010; Rahman and Sultana, 2022). Expanded market linkages further stimulate demand for green technologies, encouraging cleaner production.

Industrial restructuring promotes sectoral specialization and labor division aligned with comparative advantage theory (Deng and Yang, 2019; Zhu et al., 2021), shifting factors from low- to high-productivity sectors while phasing out polluting industries. This improves energy and resource efficiency. Producer services support green transition through knowledge inputs (Coninx et al., 2018), while integration enhances factor agglomeration, innovation exchange, and production efficiency (Li et al., 2022). A competitive regional market further accelerates industrial upgrading toward cleaner, high-value outputs.

Technological advancement serves as a cornerstone for sustainable development (Löschel and Schymura, 2013; Yue and Wang, 2019; Zhou et al., 2013). Integration fosters collaboration among firms, universities, and research institutions, facilitating innovation clustering and knowledge spillovers (Zeng et al., 2021; Holmøy, 2016; Wang et al., 2023). These dynamics enable the adoption of efficient technologies that reduce resource use and emissions (Meadows, 1972; Ali et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022). As environmental priorities rise, integration increasingly directs investment toward green and low-carbon models, enhancing urban RECC.

The influence of different regional integration policy instruments on RECC

Following Rothwell and Zegveld’s (1985) classification, regional integration policies can be grouped into supply, demand, and environmental instruments, each contributing distinctively to the enhancement of RECC.

Supply policy instruments, such as infrastructure investment, research funding, and technological support, provide foundational capacity for integration and development (Salamon and Elliot, 2002; Zhang et al., 2018). These instruments facilitate inter-regional connectivity and industrial collaboration, while also accelerating the adoption of cleaner technologies, thus directly enhancing RECC.

Demand policy instruments, including subsidies, tax incentives, and demonstration programs—stimulate market demand for green innovation and reduce barriers to sustainability transitions (Zhou et al., 2020). By shaping consumption and production patterns, they strengthen ecological competitiveness and promote environmentally friendly behaviors.

Environment policy instruments, through planning targets, regulatory controls, and institutional reforms—create enabling conditions for sustainable development (Zhou et al., 2020). These tools attract key resources such as talent and capital, foster industry clustering, and support environmental governance, which collectively enhance urban ecological resilience and RECC.

This tripartite policy framework aligns well with the Fogg Behavior Model, which posits that behavioral change requires the convergence of capability, motivation, and triggers (Fogg, 2009). Supply instruments enhance administrative and infrastructural capability; demand tools raise motivation through economic incentives; environmental measures act as triggers to initiate sustainable practices and institutional reform.

Crucially, these policy choices are most effective when combined and context-sensitive. Regional disparities in economic structure, resource endowment, and governance mean that single-policy approaches are often insufficient. Effective improvement of RECC depends on integrated policy mixes tailored to local conditions.

While supply, demand, and environmental policies each contribute to improving RECC, their effects are interdependent rather than isolated (Fig. 1). A well-designed policy mix relies on the complementarity and interaction of these instruments. In summary, enhancing RECC through regional integration requires the coordinated deployment of supply, demand, and environmental instruments, calibrated to match local administrative capacity and economic motivation.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, this study proposes a theoretical framework for enhancing the effectiveness of regional integration policies from the perspective of RECC, encompassing two key dimensions: intermediary mechanisms and policy instruments.

Research design

The research logic of this study follows a clear progression: practice problem→policy intervention→policy evaluation→effectiveness improvement (Fig. 3). This framework begins by identifying real-world issues in RECC, then moves to regional integration policy interventions designed to address these challenges. This stage is supported by measuring the intensity of regional integration policies and RECC. After implementing these policy interventions, the study evaluates their outcomes on RECC. This stage is supported by DID model. Finally, it concludes with strategies for improving policy effectiveness based on the mechanisms through which regional integration impacts RECC and the optimization of regional integration policy instrument combinations. This stage is supported by the mediation mechanism model and the fsQCA approach.

Methodology

DID model

The DID model is widely used to evaluate policy effectiveness, as it addresses endogeneity by comparing treated and control groups before and after policy implementation (Heckman et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2019). However, traditional DID assumes a uniform treatment time, which does not align with the staggered rollout of regional integration policies across YREB cities. To address this, we adopt a multi-period DID model, specified as follows:

In Eq. (1), the explanatory variable \({Y}_{{it}}\) represents the RECC of city i in year t. \({{did}}_{it}\) functions as a dummy variable denoting the policy: It is assigned a value of 1 when city i enacts the regional integration policy in year t and after the policy is in force, and 0 otherwise. The coefficient \({\alpha }_{1}\), which is the primary focus of this study, reflects the influence of the regional integration policy on RECC. \({X}_{{it}}\) is a series of control variables, \({\delta }_{i}\), \({\eta }_{t}\) capture the individual fixed effects and temporal fixed effects associated with each city, individually; \({\varepsilon }_{{it}}\) is a random perturbation term.

Mediation mechanism model

To examine the pathways by which regional integration impacts RECC more specifically, this paper constructed a mediation effect model by extending the DID form. This approach was used to test whether regional integration policies impact RECC through intermediary mechanisms such as economic linkage, industrial upgrading, and technological advancements. The specifics of the model are outlined below:

In Eq. (2), Eq. (3) and Eq. (4), \({M}_{{it}}\) are the mediating variables, \({\alpha }_{1}\) indicates the total effect of the policy on RECC, \({c}_{1}\) indicates the direct effect of the policy on RECC, and \({b}_{1}{c}_{2}\) is the mediating effect of the mediating variable. The judgment standard of mediating effect is: if \({\alpha }_{1}\) in formula (2) is significantly not 0, \({b}_{1}\) in formula (3) is significantly not 0, and \({c}_{2}\) in formula (4) is significantly not 0, then it represents the presence of mediating effect, \({c}_{1}\) in formula (4) is significantly not 0, which represents the partial mediating effect, and vice versa, it is the complete mediating effect.

fsQCA approach

The fsQCA approach leverages architecture theory and Boolean algebra to merge qualitative and quantitative methods. This approach offers several advantages for analyzing complex causal relationships and overcoming limitations inherent in traditional econometric models that frequently overlook the interactions and configurations of diverse factors (Du et al., 2021). By employing this approach, this research is designed to deliver a thorough comprehension of the policy instruments. and their combinations that effectively enhance RECC in the context of regional economic integration.

Case area

Our research area is the YREB in China, which stretches across both the eastern and western regions of the country. It comprises three prominent national urban agglomerations: the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration (YRD), the middle reaches of the Yangtze River urban agglomeration (MYR), and the Chengdu-Chongqing urban agglomeration (CC). By 2022, YREB comprised 46.3% of China’s total population, covered 21.4% of its land area, and contributed 46.3% of the nation’s GDP, underscoring its crucial role in China’s economic growth. Additionally, the urban agglomerations within the YREB exhibit a diverse range of resource and environmental endowments, economic development stages, industrial foundations, and levels of integration, providing a comprehensive sample for the study (Fig. 4).

Data pre-processing and resource

This study examines the period from 2005 to 2021, drawing on two primary data sources: socioeconomic statistics and policy documents. Socioeconomic data used to construct the RECC indicator system, control variables, and mediators were obtained from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook, China Urban Construction Yearbook, and official statistical reports from provinces and cities. Government administrative capacity indicators were sourced from the Evaluation Report on Government-Business Relationships in Chinese Cities. Cities with substantial missing data were excluded, and interpolation was used to address partial data gaps. Policy documents were collected through the Peking University Magic Weapon database and official websites of cities within the YRD, MYR, and CC urban agglomerations. To ensure quality and relevance, policy texts were screened based on three criteria: (1) only national, provincial, and municipal documents were retained; district-level policies were excluded due to high redundancy; (2) documents had to explicitly address regional integration in the study areas, excluding those with only brief mentions; (3) accepted documents included regulations, normative guidelines, and working plans. This process yielded 133 valid policy samples, which were analyzed using grounded theory. Table 1 presents detailed variable information.

Variable measurement

RECC measurement

In this paper, we revisit the foundational concept of force to evaluate RECC, developing an integrated indicator system based on a mechanics perspective (Yue and Wang, 2019). The system is composed of four key components: (1) Resource-environmental base. This component includes natural resources and environmental elements that support human activities, such as arable land and water resources. (2) Socio-economic bracing. This reflects the role of various elements in maintaining and enhancing resource-environmental quality, including human capital. (3) Pressure response. This describes the adverse consequences of human actions on the resource-environment system, such as population pressure from growth and pollutant pressure from industrial activities. (4) lubrication buffering. This represents human interventions aimed at mitigating the conflicts between pressure and support forces. Examples include urban construction and pollution treatment measures. Following the approach of Fan et al. (2023), Wang and Liu (2019), and Feng et al. (2018), the selection of specific indicators is illustrated in Fig. 5. Technically, the entropy-weighted method was used to measure RECC.

Based on the RECC measurement results for 117 cities in the YREB, this paper illustrates their spatial distribution across four representative years, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2021, using ArcGIS 10.2 software (Fig. 6).

Moderator variables selection

The selected median variables and measurement methods are as follows:

-

(1)

Economic linkage between regions reflects the intensity of economic interactions, including the flow of goods, services, and resources between them. This concept is measured by evaluating the capacity of regions to both radiate and receive economic benefits. In this study, we utilize a modified gravity model to quantify rei, drawing on the methodology outlined by (Wei, 2018) and Chen et al. (2023).

$${R}_{{ij}}=\frac{\sqrt{{P}_{i}{G}_{i}}\times \sqrt{{P}_{j}{G}_{j}}}{{D}_{{ij}}^{2}}$$(5)$${re}{i}_{i}=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j=1}^{n}{R}_{{ij}}$$(6)Where \({re}{i}_{i}\) are the sum of economic links between city \(i\) and other YREB cities; \({R}_{{ij}}\) are the degree of economic linkage between city \(i\) and city \(j\), \({P}_{i}\), \({G}_{i}\) are the population and GDP of city \(i\), \({P}_{j}\), \({G}_{j}\) are the population and GDP of city \(j\), and \({D}_{{ij}}\) are the distance between city \(i\) and city \(j\), obtained by ArcGIS.

-

(2)

Industrial restructuring refers to the transition of economic activity from the secondary to the tertiary (service) sector. In this study, Industrial restructuring is measured by the ratio of the total output value from the tertiary sector to that from the secondary sector (Zhang et al., 2024).

-

(3)

Technological advancements are assessed through both input and output indicators. Science and technology expenditures are used to measure the financial resources invested in technological development and innovation. The number of patents granted for inventions serves as an indicator of the technological outputs and innovations resulting from the investments in science and technology (Li et al., 2022).

Control variables

Following methodologies and practices from Gao et al. (2021), Gao et al. (2011), Martire et al. (2015), and Tang et al. (2016), this paper includes several control variables in the model: ur, pgdp, power, sale, and asset. To eliminate the influence of heteroscedasticity, the logarithmic forms of moderator variables and control variables are incorporated into the specific model.

Policy instruments intensity

Based on grounded theory and supported by Nvivo 12 software, the specific terminologies collected from 133 policy texts were summarized into 16 content themes, and then detailed coding was conducted in the form of “document number—policy number—policy content”. For instance, if the second regulation in the first chapter of the first document related to regional integration policy corresponds to the selected content theme, its content would be encoded as 1-1-2; and if the tenth regulation in the third chapter of the twelfth document corresponds to the selected content theme, it would be encoded as 12-3-10. Based on the above coding rules, a total of 2251 codes were ultimately formed (see Appendix Fig. 11). To measure the intensity of regional integration policy instruments, we use the total number of occurrences of keywords associated with each type of policy instrument.

Furthermore, according to the theoretical analysis framework, a city’s ability to restore or enhance RECC depends on both its administrative capacity and economic motivation. In this study, administrative capacity (capacity) is described as the capability and effectiveness of the policymaking and execution processes within a local authority. It is assessed based on government capacity, as detailed by Zhang et al. (2020). Economic motivation (motivation)is evaluated by considering the city’s economic foundation to address issues related to RECC decline, measured using GDP per capita.

Results and analysis

Benchmark regression results of policy effectiveness

Table 2 presents the benchmark regression results assessing the impact of regional integration on RECC using the DID model. Model (1) excludes control variables, while Model (2) includes them. In both models, the DID coefficients are positive and significant at the 1% level, indicating robust results. In Model (2), the coefficient of 0.0166 suggests that regional integration increased RECC by 0.016 units, reflecting improved resource allocation, factor concentration in pilot areas, and mitigation of urban development’s negative effects on RECC. Among the controls, GDP growth and agricultural machinery showed negative coefficients, implying that economic expansion and mechanization, while beneficial for output, may harm environmental sustainability. These findings underscore the importance of adjusting development strategies to better align with RECC goals.

Robustness tests

Substitution of the RECC measurement approach

In this section, we replaced the RECC measurement methodology with the TOPSIS—entropy weight method. As Table 3 presents, Model (3) excludes control variables, while Model (4) incorporates them. The results indicated that both models had notably favorable coefficients at the 1% significance level and passed the relevant statistical tests. These findings reinforce the stability of the earlier benchmark regression analysis.

Placebo test

In-time placebo test

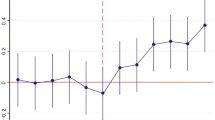

The time placebo test treated the period before policy implementation as a “pseudo-treatment time” and used only the sample data before the actual treatment for DID estimation. The model was estimated by advancing the policy implementation time by 1–10 years, as shown in Fig. 7. The analysis demonstrated that advancing the policy timeframe by 1–2 years resulted in a significant p-value, while it was not significant when advanced by 3 years or more. This finding aligned with the reality that a preparatory period often occurs before a policy is formally implemented. During this stage, regions may form intentions and enter into preparatory agreements, which can influence outcomes even before the policy officially takes effect.

In-space placebo test

For the spatial placebo test, we randomly selected individuals to create “pseudo-treatment groups” that matched the size of the actual treatment group. We then performed the DID estimation, repeating this process 500 times to obtain 500 regression results. Figure 8 presents the kernel density plot and histogram of these regression results. In the figure, the vertical line represents the baseline regression treatment effect estimate, which is positioned in the right tail of the distribution. This placement indicates that the estimate is an extreme value compared to the results from the randomized experiments. The significant deviation of the randomized experiment results from the true estimate suggests that the observed treatment effect in the baseline regression was not due to random chance, thereby reinforcing the validity of the original findings.

Restricted mixed placebo test

To strengthen robustness checks, we conducted a mixed placebo test by randomly assigning pseudo-treatment groups and uniformly distributed pseudo-treatment times, repeating the process 500 times with group sizes matching the original sample. As shown in Fig. 9, the actual DID estimate (solid line) lies at the far right of the simulated distribution, confirming its position as an outlier. The placebo estimates followed a normal distribution, indicating that the observed effect is unlikely to result from random chance. Combined with the temporal and spatial placebo tests, these results support the robustness of the benchmark regression and reaffirm the significant positive impact of regional integration policies on RECC.

Mediation mechanism analysis

Economic linkage

Based on the theoretical framework discussed earlier, a mediation effect model utilizing a multi-period DID approach was constructed to examine the mediation mechanism of regional integration on RECC. Table 4 presents the mediation effect results concerning economic linkage. The findings indicate that regional integration policy positively influenced economic connectedness, although this effect did not achieve statistical significance. However, economic connectedness itself had a positive impact on RECC and reached statistical significance at the 5% level. This implied that while the transmission pathway from “regional integration→economic linkage→RECC” is indeed positive, the current policy framework has not yet fully realized its potential to enhance RECC through economic connectedness.

This limited mediation may be attributed to several factors. First, although infrastructure and policy connections have improved, institutional fragmentation, administrative barriers, and lack of coordinated market mechanisms may hinder the deepening of inter-city economic ties. Second, many regional integration efforts have focused on physical infrastructure rather than functional economic integration, resulting in underdeveloped cross-city industrial cooperation and value chain linkages. As a result, the potential of economic linkage to channel integration benefits into RECC improvement has not yet been fully realized.

Industrial restructuring

Table 5 illustrates the findings from the mediation effect test for the pathway “regional integration→industrial restructuring→RECC”. The results revealed that while regional integration policy positively influenced industrial upgrading, this effect was not statistically significant. However, industrial upgrading positively impacted RECC, with the relationship reaching significance at the 10% threshold. Similar to the previous pathway, the chain effect exists but remains only partially activated.

This finding may be due to the time lag inherent in industrial transformation, which often requires longer periods to produce measurable ecological benefits. Additionally, industrial restructuring under regional integration has tended to prioritize output growth and competitiveness, rather than emphasizing low-carbon or green development strategies that directly contribute to RECC. Furthermore, a lack of coordination across cities in upgrading efforts and the persistence of traditional high-pollution industries in some regions may dilute the overall policy effect.

Technological advancements

Table 6 reports mediation tests using science and technology expenditures and invention patent grants as mediators. In Models (1–3), the mediation via science and technology expenditures is confirmed. Model (1) shows a total effect of 0.016 (significant at 1%). In Model (2), the DID coefficient for policy impact on lntech is 0.206 (5% significance), indicating a 20.6% higher tech investment in treated regions. In Model (3), lntech has a significant positive effect on RECC (coefficient = 0.009, significant at 1%), confirming a partial mediation effect. For invention patents (Models 4–6), the policy increased patent output, and patents positively affected RECC, though the latter was not statistically significant. These results support the pathway “regional integration technological advancement RECC,” with stronger evidence for science and technology expenditures.

Analysis of policy instruments configuration

Necessary conditions analysis

Before conducting the conditional grouping analysis, each of the five conditional variables was assessed for its “necessity”. The evaluation of Table 7 revealed that none of the conditional variables reached a consistency level of 0.9 or higher. These findings indicate that no single condition, whether it be economic motivation, administrative capacity, or regional integration policy instruments, is sufficient on its own to drive improvements in RECC.

Configurational sufficiency analysis

For the sufficiency analysis, we set a consistency threshold of 0.8 and a frequency threshold of 3, using “presence or absence” coding for all conditions. As shown in Table 8, no universal condition consistently leads to low RECC. Configuration L1 featured the absence of economic motivation and all three policy instruments. L2 involved supply policies but lacked economic motivation, administrative capacity, and environmental policies. L3 included most policy instruments but lacked administrative capacity.

For high RECC, four group paths were identified and categorized into three main configurations:

-

(1)

Economic and Environment Dual-Driven (H1a, H1b): Both paths shared environmental policies and strong economic motivation as core conditions. H1a achieved high RECC despite weak supply and demand policies, highlighting the role of green-oriented economic development. H1b, while including more policy instruments, showed internal contradictions that reduced their overall effectiveness. This configuration had the highest explanatory power and case coverage.

-

(2)

Environment-Oriented (H2): Environmental policies were the only core condition, while economic motivation and administrative capacity were peripheral. Despite weak demand-side support, cities with strong governance and economic flexibility improved RECC by updating technologies and leveraging institutional advantages. This configuration accounted for 13.8% of high-RECC cases.

-

(3)

Multiple-Centric Interaction (H3): Economic motivation, administrative capacity, and environmental policies jointly acted as core conditions, with supply policies as peripheral. In these cities, environmental policy improvement was recognized as essential to RECC enhancement. Demand policies were not decisive. This path explained 49.8% of the high-RECC cases.

Configurational substitution effect

Across all configurations, economic motivation and environmental policies consistently appear as core conditions, highlighting their essential roles in enhancing RECC. Additionally, substitution effects, visualized in Fig. 10, demonstrate that certain conditions can offset the absence of others. For instance, H1a and H1b suggest that the lack of supply and demand policies in H1a can be compensated by their presence in H1b. Similarly, administrative capacity in H1a substitutes for supply policies in H2. Other observed substitutions include: (1) supply and demand policies replacing administrative capacity; (2) administrative capacity offsetting the absence of supply and demand policies; (3) mutual substitution between demand policies and administrative capacity; and (4) supply policies balancing the absence of demand policies.

Regional heterogeneity of configuration

Given substantial variation in economic development, geographic conditions, and resource endowments, Chinese cities demonstrate heterogeneous responses to regional integration policies. These differences shape how policies affect RECC and necessitate context-specific policy strategies. To capture this diversity, we examined the configurational pathways to high RECC across three major urban agglomerations, YRD, MYR, and CC, as summarized in Table 9.

In the YRD, four configurations were identified: HC1 (Economic and Administrative-Centric): cities with strong governance and economic foundations benefit from comprehensive policy mixes, especially supply and environmental tools. HC2–HC3 (Multiple/Double-Centric): rely on synergistic interactions among all three tools, with varying dominance of supply or demand policies. HC4 (Policy-Driven): cities with weaker foundations achieve RECC gains primarily through responsive environmental and demand-side policies.

In the MYR, three configurations emerged: HE1 (Administrative-Oriented): cities with high governance capacity rely on environmental and supply tools to offset economic constraints. HE2 (Multiple-Centric): balanced configurations with environmental policies as anchors. HE3 (Economic-Policy Oriented): strong economic incentives combined with environmental tools lead to effective RECC improvement.

In the CC region, two paths were observed: HY1 (Economic-Administrative): large central cities benefit from supply–environmental combinations. HY2 (Economic-Policy): demand and environmental tools are more effective when governance is moderate but economic incentives are strong.

Across all regions, environmental policy instruments consistently emerge as core conditions. Cities with strong institutional and economic capacity benefit from integrated strategies, while others should prioritize targeted tools. These findings emphasize the need for differentiated policy combinations tailored to local administrative capacity and economic motivation to maximize RECC improvements under regional integration.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Regional integration can sometimes reduce RECC due to irrational shifts in production and lifestyle, leading to notable social, economic, and environmental consequences, particularly in urban agglomerations (Chen et al., 2023). These include demographic imbalances, increased emissions and surface temperatures, and degradation of resources such as water and soil. Thus, enhancing RECC in the post-integration phase is essential. China’s ecological corridor initiative in the YREB offers a representative case, aiming to improve RECC through regional coordination. It provides a valuable platform for evaluating the effectiveness of integration policies across diverse local governments. While prior studies have examined factors such as government cooperation, industrial restructuring, land expansion, and urban development (Mao et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2022), few have directly connected these with RECC in a unified framework. To address this gap, we develop a theoretical model incorporating both influence mechanisms and policy instruments, and apply empirical analysis using time-series panel data, policy documents, a DID model, mediation analysis, and fsQCA.

Our findings indicate that regional integration policies can directly and effectively enhance RECC. However, while these policies counteract the decline in RECC during urban development, the observed improvements remain relatively modest. This raises concerns about the long-term sustainability of regional integration, reflected in two key aspects. First, although the agglomeration effect from regional integration can boost RECC, it may not necessarily support the ecological and environmental sustainability of resource-based cities or peripheral areas within urban agglomerations. Without diversifying into non-resource-based industries and adopting environmentally protective production methods, these cities risk encountering the “resource curse”, which could in turn impede the overall progress of regional integration (Xing et al., 2023). Second, challenges such as inefficient government competition and suboptimal resource allocation persist in implementing regional integration policies (Fang and Yu, 2017).

Moreover, the effectiveness of regional integration policies is not uniform across regions. Differences in economic development levels and administrative capacities significantly shape how policies affect RECC. Cities with strong governance and economic foundations are better positioned to implement comprehensive policy mixes, while less developed regions often rely on simpler, more targeted tools. Our findings suggest that policy outcomes are highly context-dependent, reinforcing the need for locally adapted integration strategies. Therefore, additional measures are necessary to enhance the effectiveness of these policies and address these issues more comprehensively.

To improve the generalizability of our findings, it is useful to compare the YREB with other major integrated regions in China and internationally. Domestically, the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region emphasizes administrative coordination and environmental regulation, particularly in air pollution control, reflecting a governance-driven model. In contrast, the Pearl River Delta prioritizes market openness, innovation, and industrial clustering, relying more on economic and supply-oriented policies. The YREB adopts a more balanced strategy that integrates governance, fiscal support, and ecological planning. These differences underscore the need for context-specific policy portfolios to effectively enhance RECC. Internationally, the European Union combines environmental goals with economic development through supranational coordination and standardized governance—aligning with our finding that environmental policies are central to RECC improvement. In contrast, ASEAN’s integration, focused on infrastructure and liberalization, lacks binding environmental mandates, leading to uneven sustainability outcomes. Together, these comparisons reinforce that economic and industrial reforms alone are insufficient without strong environmental governance and institutional coherence.

Economic change, industrial restructuring, and technological advancement are often seen as key drivers of RECC improvement (Fan et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2021). However, in the early stages of economic linkage and restructuring, their effects on RECC may be limited—consistent with our finding that their mediating roles were statistically insignificant. This may be because RECC enhancement depends on multiple interacting factors. Without complementary elements such as environmental policies and infrastructure development, economic linkage alone may not sufficiently improve RECC. Similarly, if industrial restructuring prioritizes economic efficiency over environmental sustainability, its impact on RECC may be constrained.

As shown by the configurations, high RECC levels depend on the synergy among ability, motivation, and policy triggers. Rather than applying all policy tools uniformly, a more effective approach tailors instruments to cities’ specific economic and administrative conditions. Our analysis highlights environmental policies as central, with supply and demand policies often playing supplementary roles. Within the YREB, particularly the YRD, environmental measures were dominated by assessment and supervision (424 cases) and regulatory controls (228 cases). In contrast, in less developed areas like MYR and CC, preferential tools such as land tax reductions were more effective, supporting economies reliant on small and micro-scale businesses.

Certainly, the success of an individual policy tool does not suggest that a straightforward approach is adequate. The success of policy implementation often hinges on integrating various measures within the chosen policy framework. For instance, if a region prioritizes supply policies, incorporating a series of measures such as funding support, talent development, and enhancements in public services within this framework could be more impactful than dispersing efforts across disparate supply, demand, and environmental policy instruments. This integrated approach ensures a more cohesive and robust strategy, enhancing the overall effectiveness of regional integration efforts.

Policy recommendations

The conclusions drawn from this research offer useful directions for shaping strategies aimed at optimizing regional integration patterns and enhancing RECC. The following key takeaways inform future policy decisions with clearer implementation pathways:

-

(1)

Stepping up efforts to foster regional integration. To achieve this, local governments should develop high-quality, coordinated regional development plans that align with economic strengths, resource endowments, and environmental goals. In practice, this requires establishing cross-regional coordination platforms or planning committees to ensure coherence in land use, ecological protection, and infrastructure investment. Strengthening collaboration among governments, enterprises, and communities is also essential for addressing shared challenges in resource and environmental management. Policymakers should promote inclusive decision-making mechanisms, such as stakeholder hearings and joint policy drafting, to incorporate diverse perspectives. In terms of infrastructure, cities should prioritize strategic projects that enhance intercity connectivity, especially high-speed rail, highway systems, and smart energy grids. The integration of smart technologies, such as real-time monitoring systems, intelligent logistics, and low-emission transit, can improve efficiency and reduce environmental impacts.

-

(2)

Strengthening mediation effects. To enhance regional integration and inter-city linkages, it is essential to gradually improve transportation and communication infrastructure, and promote the efficient flow of capital, technology, and human resources across regions. This can be achieved through the construction of unified information platforms, regional innovation alliances, and intercity talent exchange mechanisms. Urban innovation is also a key driver of RECC enhancement. Encouraging leading enterprises to engage in regional cooperation and building industrial clusters that promote spillovers are effective strategies (Chen et al., 2023). Additionally, cities should support platforms for technology sharing and cross-regional research collaboration. Industrial structure adjustment should not focus solely on “upgrading,” but on rationalization tailored to each city’s unique resource endowments and development stage (Hu et al., 2024). Emphasis should be placed on promoting low-carbon, circular, and ecologically compatible industries.

-

(3)

Prioritizing targeted policy instruments or their combinations. Urban managers should assess their local economic foundation and administrative capacity to inform policy choices. Cities within the YREB (e.g., Nanchang, Ningbo, Huanggang) with weaker economic motivation or limited governance capacity should adopt focused strategies centered on a single dominant tool—particularly environmental policies such as ecological zoning, emission monitoring, and resource regulation. Avoiding scattered investment across multiple instruments can improve effectiveness. Conversely, cities with strong market incentives but limited administrative capacity (e.g., Wuhan, Changsha, Chengdu) should adopt hybrid strategies, combining environmental policies with selective supply- and demand-side tools (e.g., infrastructure subsidies, innovation incentives, green financing). Cities with both strong economic and governance capacity should emphasize coordination between top-level design and local implementation. In such cases, a comprehensive mix of environmental, supply, and demand instruments should be deployed in a phased and synergistic manner, especially in rural-urban transition zones, to ensure sustained improvements in RECC.

Limitations and further research directions

This study has several limitations that suggest directions for future research.

First, potential spatial correlations in RECC across regions were not considered. Incorporating spatial econometric methods alongside DID would allow for a better assessment of spatial dependencies in regional integration impacts. Second, the study did not fully address the lagged effects of different policy combinations. While configuration analysis revealed some heterogeneity, future research should explore how varying lag structures influence the timing and effectiveness of policies. Third, the impact of supply, demand, and environmental policy mixes may vary over time. This study did not examine the dynamic evolution of these combinations. Future work should analyze how their effectiveness changes across implementation stages to identify optimal sequencing strategies for improving RECC.

Conclusion

To bridge the gap between theory and methodology arising from fragmented literature on the relationship between regional integration and RECC, this paper develops an integrative framework that combines influence mechanisms and policy instruments, addressing how to measure and enhance the effectiveness of regional economic integration policies in urban agglomeration areas. Specifically, the study utilized a dataset of 117 cities within the YREB from 2005 to 2021, employing a DID model and a mediation mechanism model to assess the policy effect and precise channels that regional integration employs to affect RECC. Additionally, by considering the motivation and capacity of policy triggers, the study examined economic motivation, administrative capacity, supply policies, demand policies, and environmental policies as antecedent conditions. The analysis then uncovered the combined paths of regional integration policy instruments leading to high RECC using the fsQCA model.

The major findings of this research include: regional integration policies positively and significantly impacted RECC, increasing it by approximately 0.016 units. The mechanism analysis identified economic linkage, industrial restructuring, and technological advancements as crucial mediators in regional integration policies interfering with RECC. However, the mediating effects of economic linkage and industrial restructuring had not yet been fully realized. Furthermore, the configurational analysis revealed that the interplay of economic motivation, administrative capacity, and policy instruments was essential for regional integration to enhance RECC. This interaction generated distinct configurations that led to high levels of RECC, with significant variations observed among different urban agglomeration areas within the YREB. Moreover, by comparing different configurations, it was observed that a substitution relationship existed among the five antecedent conditions. By focusing on the mechanisms that influence the impact of regional integration policies on RECC and refining the combination of policy instruments, this research provides a comprehensive approach to improving the effectiveness of these policies on RECC.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Change history

15 August 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05609-x

References

Ali EB, Anufriev VP, Amfo B (2021) Green economy implementation in Ghana as a road map for a sustainable development drive: a review. Sci Afr 12:e00756

Anamaghi S, Behboudian M, Mahjouri N, Kerachian R (2023) A resilience-based framework for evaluating the carrying capacity of water and environmental resources under the climate change. Sci Total Environ 902:165986

Apergis N, Payne JE (2010) Renewable energy consumption and economic growth: evidence from a panel of OECD countries. Energy Policy 38(1):656–660

Bao C, Wang H, Sun S (2022) Comprehensive simulation of resources and environment carrying capacity for urban agglomeration: a system dynamics approach. Ecol Indic 138:108874

Caragliu A, Del Bo C, Nijkamp P (2011) Smart cities in Europe. J Urban Technol 18(2):65–82

Carey DI (1993) Development based on carrying capacity. Glob Environ Change 3(2):140–148

Castellani V, Sala S, Pitea D (2007) A new method for tourism carrying capacity assessment. Ecosyst Sustain Dev VI I:365–374

Chen D, Hu W, Li Y, Zhang C, Lu X, Cheng H (2023) Exploring the temporal and spatial effects of city size on regional economic integration: evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt in China. Land Use Policy 132:106770

Chen D, Li Y, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Hou J, Lin Y, Wu S, Lang Y, Hu W (2024) Regional coordinated development policy as an instrument for alleviating land finance dependency: evidence from the urban agglomeration development. Land Use Policy 143:107182

Chen D, Li Y, Hu W, Lang Y, Zhang Y, Cheng C (2024) Uncovering the influence of land finance dependency on inter-city regional integration: an explanatory framework integrating time-nonlinear and spatial factors. Land Use Policy 144:107207

Cheng J, Zhou K, Chen D, Fan J (2016) Evaluation and analysis of provincial differences in resources and environment carrying capacity in China. Chin Geogr Sci 26(4):539–549

Coninx K, Deconinck G, Holvoet T (2018) Who gets my flex? An evolutionary game theory analysis of flexibility market dynamics. Appl Energy 218:104–113

Deng H, Yang H (2019) Haze governance, local competition and industrial green transformation. China Ind Econ (10):118–136

Du Y, Li J, Liu Q, Zhao S, Chen K (2021) Configurational theory and QCA method from a complex dynamic perspective: research progress and future directions. World Manag 37(03):180–197

Esfandi S, Nourian F (2021) Urban carrying capacity assessment framework for mega mall development. A case study of Tehran’s 22 municipal districts. Land Use Policy 109:105628

Ewing R, Hamidi S, Grace JB (2016) Urban sprawl as a risk factor in motor vehicle crashes. Urban Stud 53(2):247–266

Ewing R, Meakins G, Hamidi S, Nelson AC (2014) Relationship between urban sprawl and physical activity, obesity, and morbidity—Update and refinement. Health Place 26:118–126

Fan W, Song X, Liu M, Shan B, Ma M, Liu Y (2023) Spatio-temporal evolution of resources and environmental carrying capacity and its influencing factors: a case study of Shandong Peninsula urban agglomeration. Environ Res 234:116469

Fang C, Yu D (2017) Urban agglomeration: an evolving concept of an emerging phenomenon. Landsc Urban Plan 162:126–136

Feiock RC (2013) The institutional collective action framework. Policy Stud J 41(3):397–425

Feng Z, S T, Y Y, Y H (2018) The progress of resources and environment carrying capacity: from single-factor carrying capacity research to comprehensive research. J Resour Ecol 9(2):125–134

Fogg B (2009) A behavior model for persuasive design. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology, 1–7

Gao Q, Fang C, Liu H, Zhang L (2021) Conjugate evaluation of sustainable carrying capacity of urban agglomeration and multi-scenario policy regulation. Sci Total Environ 785:147373

Gao X, Chen T, Fan J (2011) Analysis of the population capacity in the reconstruction areas of 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. J Geogr Sci 21(3):521–538

Guo Q, Wang J, Yin H, Zhang G (2018) A comprehensive evaluation model of regional atmospheric environment carrying capacity: model development and a case study in China. Ecol Indic 91:259–267

Guo L, Tang M, Wu Y, Bao S, Wu Q (2025) Government-led regional integration and economic growth: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment of urban agglomeration development planning policies in China. Cities 156:105482

Heckman JJ, Ichimura H, Todd P (1998) Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator. Rev Econ Stud 65(2):261–294

Holmøy E (2016) The development and use of CGE models in Norway. J Policy Model 38(3):448–474

Hu J, Ma C, Li C (2022) Can green innovation improve regional environmental carrying capacity? An empirical analysis from China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(20):13034

Hu K, Sinha A, Tan Z, Shah MI, Abbas S (2022) Achieving energy transition in OECD economies: discovering the moderating roles of environmental governance. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 168:112808

Hu W, Li Z, Chen D, Zhu Z, Peng X, Liu Y, Liao D, Zhao K (2024) Unlocking the potential of collaborative innovation to narrow the inter-city urban land green use efficiency gap: Empirical study on 19 urban agglomerations in China. Environ Impact Assess Rev 104:107341

Khoshnava SM, Rostami R, Zin RM, Štreimikiene D, Yousefpour A, Mardani A, Alrasheedi M (2020) Contribution of green infrastructure to the implementation of green economy in the context of sustainable development. Sustain Dev 28(1):320–342

Li L, Ma S, Zheng Y, Ma X, Duan K (2022) Do regional integration policies matter? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment on heterogeneous green innovation. Energy Econ 116:106426

Li M, Han C, Shao Z, Meng L (2024) Exploring the evolutionary mechanism of the cross-regional cooperation of construction waste recycling enterprises: a perspective of complex network evolutionary game. J Clean Prod 434:139972

Li X, Zhou X, Yan K (2022) Technological progress for sustainable development: an empirical analysis from China. Econ Anal Policy 76:146–155

Liu H, Cui C, Chen X, Xiu P (2023) How can regional integration promote corporate innovation? A peer effect study of R&D expenditure. J Innov Knowl 8(4):100444

Liu Y, Zhang X, Pan X, Ma X, Tang M (2020) The spatial integration and coordinated industrial development of urban agglomerations in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Cities 104:102801

Löschel A, Schymura M (2013) Modeling technological change in economic models of climate change. In Encyclopedia of energy, natural resource, and environmental economics. Elsevier, pp 89–97

Ma S, Li L, Zuo J, Gao F, Ma X, Shen X, Zheng Y (2024) Regional integration policies and urban green innovation: fresh evidence from urban agglomeration expansion. J Environ Manag 354:120485

Mao X, Huang X, Song Y, Zhu Y, Tan Q (2020) Response to urban land scarcity in growing megacities: urban containment or inter-city connection? Cities 96:102399

Martire S, Castellani V, Sala S (2015) Carrying capacity assessment of forest resources: enhancing environmental sustainability in energy production at local scale. Resour Conserv Recycl 94:11–20

Meadows D (1972) Limits to Growth. Universe Books, USA

Meijers EJ, Burger MJ (2017) Stretching the concept of ‘borrowed size. Urban Stud 54(1):269–291

Mohsin M, Jamaani F (2023) Unfolding impact of natural resources, economic growth, and energy nexus on the sustainable environment: guidelines for green finance goals in 10 Asian countries. Resour Policy 86:104238

Mongo M, Belaïd F, Ramdani B (2021) The effects of environmental innovations on CO2 emissions: empirical evidence from Europe. Environ Sci Policy 118:1–9

Mun J, Lee JS, Kim S (2024) Effects of urban sprawl on regional disparity and quality of life: a case of South Korea. Cities 151:105125

Mutingi M, Mbohwa C, Dube P (2017) System dynamics archetypes for capacity management of energy systems. Energy Procedia 141:199–205

Niu S, Chen Y, Zhang R, Luo R, Feng Y (2023) Identifying and assessing the global causality among energy poverty, educational development, and public health from a novel perspective of natural resource policy optimization. Resour Policy 83:103770

Petricevic O, Teece DJ (2019) The structural reshaping of globalization: implications for strategic sectors, profiting from innovation, and the multinational enterprise. J Int Bus Stud 50(9):1487–1512

Rahman MM, Sultana N (2022) Impacts of institutional quality, economic growth, and exports on renewable energy: emerging countries perspective. Renew Energy 189:938–951

Reddy RK, Park S-J, Mooty S (2022) Emerging market firm investments in advanced markets: a country of origin perspective. J Multinatl Financ Manag 65:100748

Ren C, Guo P, Li M, Li R (2016) An innovative method for water resources carrying capacity research – Metabolic theory of regional water resources. J Environ Manag 167:139–146

Rothwell R, Zegveld W (1985) Reindustrialization and technology. Logman Group Limited, London

Salamon LM, Elliot O (2002) Tools of government: a guide to the new governance. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Sharma M, Jain S (2024) Bottom-up assessment of air quality management strategies in Vijayawada, India: Emissions inventory, atmospheric capacity, and policy scenarios. Sustain Cities Soc 112:105650

Shen L, Cheng G, Du X, Meng C, Ren Y, Wang J (2022) Can urban agglomeration bring “1 + 1 > 2Effect”? A perspective of land resource carrying capacity. Land Use Policy 117:106094

Solarin SA, Tiwari AK, Bello MO (2019) A multi-country convergence analysis of ecological footprint and its components. Sustain Cities Soc 46:101422

Souza IDC, Morozesk M, Siqueira P, Zini E, Galter IN, Moraes DA, Matsumoto ST, Wunderlin DA, Elliott M, Fernandes MN (2022) Metallic nanoparticle contamination from environmental atmospheric particulate matter in the last slab of the trophic chain: nanocrystallography, subcellular localization and toxicity effects. Sci Total Environ 814:152685

Sun J, Miao J, Mu H, Xu J, Zhai N (2022) Sustainable development in marine economy: assessing carrying capacity of Shandong province in China. Ocean Coast Manag 216:105981

Sun M, Wang J, He K (2020) Analysis on the urban land resources carrying capacity during urbanization—a case study of Chinese YRD. Appl Geogr 116:102170

Tang B, Hu Y, Li H, Yang D, Liu J (2016) Research on comprehensive carrying capacity of Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region based on state-space method. Nat Hazards 84(S1):113–128

Tenaw D, Beyene AD (2021) Environmental sustainability and economic development in sub-Saharan Africa: a modified EKC hypothesis. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 143:110897

Wang H, Chen Z, Wu X, Nie X (2019) Can a carbon trading system promote the transformation of a low-carbon economy under the framework of the porter hypothesis?—Empirical analysis based on the PSM-DID method. Energy Policy 129:930–938

Wang J, Hu Y (2020) Spatial correlation and spatial spillover effects: a study on the impact of industrial ecological innovation on resource and environmental carrying capacity. Theory Pract Financ Econ 41(01):117–124

Wang L, Liu H (2019) The comprehensive evaluation of regional resources and environmental carrying capacity based on PS-DR-DP theoretical model. J Geogr Sci 29:363–376

Wang L, Zeng W, Cao R, Zhuo Y, Fu J, Wang J (2023) Overloading risk assessment of water environment-water resources carrying capacity based on a novel Bayesian methodology. J Hydrol 622:129697

Wang Q, Li W (2020) Research progress and prospect of regional resources and environment carrying capacity evaluation. Ecol Environ 29(07):1487–1498

Wang X, Zhang S, Gao C, Tang X (2024) Coupling coordination and driving mechanisms of water resources carrying capacity under the dynamic interaction of the water-social-economic-ecological environment system. Sci Total Environ 920:171011

Wei L (2018) Influence of urban agglomeration economic cooperation on regional coordinated development: based on comparison between Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei and Shanghai-Jiangsu-Zhejiang. Sci Geogr Sin 38(4):575–579

Westing AH (1989) The environmental component of comprehensive security. Bull Peace Propos 20(2):129–134

Xing M, Liu X, Luo F (2023) How does the development of urban agglomeration affect the electricity efficiency of resource-based cities?—An empirical research based on the fsQCA method. Socio Econ Plan Sci 86:101479

Yang Z, Song J, Cheng D, Xia J, Li Q, Ahamad MI (2019) Comprehensive evaluation and scenario simulation for the water resources carrying capacity in Xi’an city, China. J Environ Manag 230:221–233

Yue W, Wang T (2019) Logical problems on the evaluation of resources and environment carrying capacity for territorial spatial planning. China Land Sci 33(03):1–8

Zeng W, Li L, Huang Y (2021) Industrial collaborative agglomeration, marketization, and green innovation: evidence from China’s provincial panel data. J Clean Prod 279:123598

Zhang Fei, Wang Y, Ma X, Wang Y, Yang G, Zhu L (2019) Evaluation of resources and environmental carrying capacity of 36 large cities in China based on a support-pressure coupling mechanism. Sci Total Environ 688:838–854

Zhang F, Zhu F (2022) Exploring the temporal and spatial variability of water and land resources carrying capacity based on ecological footprint: a case study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration, China. Curr Res Environ Sustain 4:100135

Zhang H, Zheng J, Hunjra AI, Zhao S, Bouri E (2024) How does urban land use efficiency improve resource and environment carrying capacity? Socio-Econ Plan Sci 91:101760

Zhang H, Xu Z, Sun C, Elahi E (2018) Targeted poverty alleviation using photovoltaic power: review of Chinese policies. Energy Policy 120:550–558

Zhang S, Kang B, Zhang Z (2020) Evaluation of doing business in Chinese provinces: indicator system and quantitative analysis. Bus Manag J 42(04):5–19

Zhang Y, Xu J, Zeng G, Hu Q (2009) The spatial relationship between regional development potential and resource & environment carrying capacity. Resour Sci 31(08):1328–1334

Zhou D, Chong Z, Wang Q (2020) What is the future policy for photovoltaic power applications in China? Lessons from the past. Resour Policy 65:101575

Zhou X, Zhang J, Li J (2013) Industrial structural transformation and carbon dioxide emissions in China. Energy Policy 57:43–51

Zhu H, Jiang S (2024) Navigating urban sustainable development: exploring the impact of low carbon policies on the urban ecological carrying capacity. J Clean Prod 469:143162

Zhou J, Chang S, Ma W, Wang D (2021) An unbalance-based evaluation framework on urban resources and environment carrying capacity. Sustain Cities Soc 72:103019

Zhu W, Zhu Y, Lin H, Yu Y (2021) Technology progress bias, industrial structure adjustment, and regional industrial economic growth motivation—research on regional industrial transformation and upgrading based on the effect of learning by doing. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 170:120928

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42101307) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2662025GGPY004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Danling Chen, Yunlei Zhang, Dongming Liao and Jia Li wrote the main manuscript text, and Xinhai Lu and Chaozheng Zhang prepared figures, and Danling Chen and Yunlei Zhang prepared Data curation and visualization. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study utilized publicly available secondary data, including city-level socioeconomic statistics and official policy documents. All procedures performed in this research adhered to the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and complied with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. As the study did not involve direct interaction with human participants or the collection of identifiable private information, formal ethical approval was not required.

Informed consent

Since this study analyzed aggregated and anonymized secondary data from public sources, obtaining informed consent from individuals was not applicable. The data sources used ensure confidentiality and do not contain any personal identifying information.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D., Lu, X., Zhang, C. et al. Measuring and enhancing the effectiveness of regional integration policies for resource and environmental carrying capacity. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1102 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05407-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05407-5